Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Mechanistic Scale-Up of Gas-Solid Fluidized Beds via Local Hydrodynamic Similarity

1 Chemical and Biochemical Engineering Department, Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T), Rolla, MO 65409, USA

2 Chemical Engineering Department, Sirte University, Sirte, P.O. Box 674, Libya

3 Nuclear Engineering Department, Missouri University of Science and Technology (Missouri S&T), Rolla, MO 65409, USA

4 Nuclear Technologies Institute, King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology (KACST), P.O. Box 6086, Riyadh, 11442, Saudi Arabia

5 Technology Development Cell, Mohammed VI Polytechnic University, Ben Guerir, 43150, Morocco

* Corresponding Authors: Thaar M. Aljuwaya. Email: ; Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan. Email:

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(10), 2443-2471. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.067557

Received 06 May 2025; Accepted 16 October 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

This study presents a detailed experimental evaluation of a newly developed mechanistic scale-up methodology for gas-solid fluidized beds. Traditional scale-up approaches typically rely on matching global dimensionless groups, which often fail to ensure local hydrodynamic similarity. In contrast, the new mechanistic method aims to achieve scale-up by matching the radial profiles of gas holdup between geometrically similar beds at corresponding dimensionless axial positions (z/Dc). This approach is based on the premise that when gas holdup profiles align, other key hydrodynamic parameters—such as solids holdup and particle velocity—also become similar. To validate this methodology, experiments were conducted in two fluidized beds with inner diameters of 14 cm and 44 cm. Optical probes and gamma ray densitometry (GRD) were used to measure local gas holdup, solids holdup, and particle velocity at multiple axial and radial positions. The results show that matched gas holdup profiles led to mean absolute deviations (MAD) below 3% in solids holdup and particle velocity, confirming hydrodynamic similarity. In contrast, unmatched profiles resulted in significant deviations across all parameters.Keywords

Gas–solid fluidized beds find diverse applications in various industries due to their unique characteristics. For example, they have been applied in biodiesel catalyst preparation [1], fluid catalytic cracking [2], combustion efficiency improvement [3], cooling processes [4], medicinal functional food processing [5], carbon emission reduction [6], particle coating [7], nuclear fuel particle coating [8], solar panel waste pyrolysis [9], polymer and biomass combustion [10], and gas-solid reacting flow modelling [11]. These fluidized beds consist of solid particles suspended and buoyed by a flowing gas, creating a dynamic system with enhanced heat and mass transfer properties. In chemical and petrochemical industries, gas-solid fluidized beds are commonly employed for catalytic reactions, allowing for efficient contact between reactants and catalysts [12]. In pharmaceutical and food processing, these beds are utilized for drying, coating, and granulation processes, providing uniform particle size distribution and improved product quality. Moreover, gas-solid fluidized beds play a crucial role in environmental applications such as combustion and gasification, facilitating cleaner and more efficient energy production. The versatility of gas-solid fluidized beds makes them invaluable in optimizing processes across multiple sectors, contributing to enhanced productivity and sustainability. Gas-solid fluidized beds also offer the flexibility to operate at different temperatures and pressures, and the ability to use a wide range of catalysts. Additionally, their design can be easily modified to meet changing process requirements. Simple fluidized beds consist of cylinders with gas passing through spargers and distributors at high enough speeds to suspend particles. Even though gas-solids fluidized beds are relatively straightforward to construct, their design, scaling up, and hydrodynamics pose challenges. A comprehensive grasp of the hydrodynamics, transports, and interactions is essential for ensuring the reliable and safe design and scale-up process of fluidized beds, irrespective of their mechanical simplicity. The flow of gas and solids, as well as the heat transfer between the solids and gas, can be influenced by factors such as the geometry and internals of the bed, including the size and type of particles. The pressure, temperature, and superficial gas velocity all have an effect on the particle size distribution of the bed, which affects the efficiency and performance of the bed. Physical and thermodynamic properties, chemical kinetics, and physical and thermodynamic properties are also important. Quantifying and characterizing the impacts of these parameters and their interactions on flow patterns, velocity fields, turbulent parameters, bubble breakup, gas holdup, as well as heat and mass transfer, pose challenges. The complex hydrodynamic nature of gas-solid fluidized beds makes it challenging to fully comprehend their scale-up mechanisms. Scaling up fluidized beds for petrochemical operations is a vital issue, thus many studies have been conducted on this [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. Moving from laboratory to industrial scale complicates the development of fluidized beds [26]. In large fluidized beds, for example, bubbles rise faster because wall effects decrease and there is less exchange with dense phase [23,26]. Prior to the design and installation of a new industrial fluidized bed, it is essential to conduct preliminary trials and experiments in the pilot plant system. This ensures the mitigation of unforeseen implications that may arise during the scaling-up process. It can be quite expensive to directly scale up from lab to industrial scale. Therefore, it is essential to understand the scale effects and design the industrial fluidized bed accordingly to ensure operational efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Numerous studies in the literature have explored the scaling-up of gas-solid fluidized beds [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. These investigations have revealed the challenges associated with scaling up gas-solid fluidized beds, primarily stemming from the intricate interactions among particles, gas, and the bed walls. The scale-up process must be carefully studied in order to ensure that the bed is operating optimally. Numerous initiatives have been undertaken to develop a scale-up methodology that relies on aligning the governing dimensionless parameters between small and large fluidized beds. Nevertheless, not all of these endeavors have successfully met this objective. In many cases, the scale-up of fluidized beds has led to subpar performance and/or unforeseen outcomes. To determine the scaling relationships of fluidized beds, Romero [27] examined factors affecting their operation according to how dimensionless groups were matched. Matching the dimensionless groups was found to enhance the performance of the beds. The study’s findings suggested that the scaling relationships among dimensionless groups could be employed to optimize the design and operation of fluidized beds. A four-dimensional framework for characterizing fluidized beds hydrodynamics has been proposed: Froude number, fluidized bed height to fluidized bed diameter ratio, density ratio of solid to fluid, and Reynolds number. The Froude number is a measure of the fluidization velocity of a solid-liquid mixture in a fluidized bed. The fluidized bed height to fluidized bed diameter ratio is a measure of the aspect ratio of the fluidized bed. The density ratio of solid to fluid is a measure of the density of the solid particles relative to the fluid. The Reynolds number is a measure of the turbulence of the fluidized bed. Therefore, fluidized bed systems can be effectively described by these four dimensionless parameters [27]. The experimental validation of the four dimensionless groups has been found insufficient. Frye et al. [24] investigated how the apparent reaction rate varied depending on the fluidized bed size. They observed that the reaction rate for the smaller beds decreased three times as much as that for the larger beds. The results suggested that the decreased reaction rate was due to the poor mixing of the reactants and the reaction products in the small beds. The study concluded that the reaction rates were significantly influenced by the size of the fluidized bed. Additionally, the Buckingham Pi theorem was utilized to identify a set of dimensionless groups related to a single dependent variable in fluidized beds [28].

Glicksman [16] and Horio et al. [13] suggested using the governing equations to match selected dimensionless groups to produce hydrodynamic similarity between two fluidized beds of varying sizes. The dimensionless groups describe the relationship between the external forces acting on fluidized beds and the inertia and gravity forces acting on the fluidized beds. By matching the dimensionless groups between large-and small-scale fluidized beds, the two systems can be made hydrodynamically matched and the results from the small-scale fluidized bed will enhance the prediction of the behavior of the large-scale fluidized bed. Additionally, Glicksman et al. [20] revised and streamlined the original scaling laws proposed by [16], incorporating the Froude number. The Froude number, representing the ratio of inertial forces to gravitational forces, serves as a valuable indicator for assessing the stability of a fluidized bed. In assessing their suggested methodology, Glicksman [16], Glicksman et al. [20], and Horio et al. [13] exclusively measured global parameters. However, a more comprehensive evaluation of their methodology requires a closer analysis of local parameters. As described by Glicksman [16], the diameter effect can be explained by less efficient interactions between solids and gases in fluidized beds, which could account for the reduced conversion efficiency. This behavior is attributed to increased gas holdup between particles and a reduction in bubble size as particle size increases. These changes reduce the efficiency of gas-solid contact, limiting particle exposure to the reactant gas. Even though dimensionless group scaling rules have been proposed by [16,20], the studies have adopted different assumptions and simplified processes. It was essentially assumed that the fluid was incompressible and collisional forces between particles were neglected. Thus, the parameters are obtained through simplification and assumptions, disregarding the effects of compressibility and inter-particle forces. Moreover, particle restitution coefficients and friction coefficients were not incorporated into the calculation of inter-particle collisions. Using the aforementioned assumptions, [16] determined the first list of dimensionless groups (Eq. (1)). The dimensionless groups provide a way of expressing the relationships between the variables in a non-dimensional form.

Horio et al. [13] noted that reaction yields decreased as bed diameter increased. This was attributed to a decrease in the number of collisions of catalyst particles and reactants, thus reducing the reaction rate. Horio et al. [13] explored a similar problem regarding bubble size and distribution in fluidized beds of various sizes. They found that bubble size and frequency increased with larger bed sizes. In order to address this matter, updated rules for scaling up were developed in addition to those already in place [16]. The new rules were designed to account for the effects of the coalescence of bubbles and the splitting of bubbles in fluidized beds. This resulted in particle behavior could be predicted better in fluidized beds and scale-up rules could be developed more accurately.

Knowlton et al. [21] have provided qualitative findings regarding changes in bubble size and solids hold-up as the size of the fluidized bed undergoes alterations. These findings indicate an increase in bubble size as the bed size expands, accompanied by a decrease in solids hold-up. Chen et al. [25] found that bubble paths on small-scale beds are different from those on large-scale beds in gas-liquid fluidized beds. This is because in small beds, the bubbles tend to move in a more chaotic and complex pattern to avoid colliding with each other. The bubbles on small beds tend to move in one direction, while on large beds, the bubbles tend to move in multiple directions and eventually converge around the bed axis. Mabrouk et al. [19] investigated the essential design and operational variables of fluidized beds across three scales, analyzing their impact on scaling up and operation. Nevertheless, the evaluation of local parameters to validate the dimensionless group-based scaling methodology was not conducted. Therefore, it is important to examine the local parameters to evaluate the accuracy of the dimensionless group-based scaling approach. The scaling relationships proposed by Glicksman [16] were experimentally verified by Stein et al. [29]. Particle cycle frequency in bubbling fluidized beds of varying sizes was measured using a positron emission particle tracking technique. Similarity was achieved at the viscous limit by matching the Froude numbers. Moreover, the particle-to-bed diameter ratio showed minimal sensitivity to changes in the gas-to-particle density ratio, except in instances where the ratio was substantial.

Efhaima and Al-Dahhan [14] assessed the scaling relationships proposed by [16] through the utilization of non-invasive measurement techniques. They employed gamma ray computed tomography (CT) and radioactive particle tracing (RPT) to evaluate various local parameters, including solids holdup, solid velocity, and turbulent parameters. Zaid et al. [30] also evaluated the scaling relationships of [16] using optical probe. The studies mentioned [14,30] concluded that merely matching dimensionless groups is insufficient for achieving similarity in local hydrodynamic parameters between two fluidized beds of different sizes. Furthermore, measurements of local hydrodynamic parameters were found to be crucial in evaluating scale-up methodologies accurately. Consequently, a novel mechanistic approach has been formulated, centering on aligning gas holdup profiles between fluidized beds of varying sizes [15,31]. The mechanistic scale-up methodology was formulated based on the observation that the dynamics of gas-solid fluidized beds are predominantly governed by the gas phase: “When fluidized beds exhibit geometric similarity and possess nearly identical (referred to as matched) gas phase holdup radial profiles at a specified bed height within the developed flow region, the local dimensionless values of hydrodynamic parameters and their trends align or closely resemble each other in these two fluidized beds at corresponding bed heights”. Efhaima and Aldahhan [15] assessed and verified the efficacy of this novel mechanistic scale-up by applying CT and RPT techniques to two fluidized beds of varying sizes. Achieving matched radial profiles of gas holdup in geometrically similar beds was found to result in identical or closely aligned local and global hydrodynamics. It is further noted that discrepancies in detailed hydrodynamics become more pronounced as the magnitudes and trends of gas holdup radial profiles between two beds diverge. Taofeeq and Al-Dahhan [32] examined the Kolmogorov entropy in two fluidized beds of varying sizes as part of their assessment of the chaotic scale-up approach. They concluded that when experimental conditions feature equivalent or matched radial profiles of Kolmogorov entropy, there is a tendency for similarity in local hydrodynamic parameters to occur.

From this review of the literature, it is evident that scale-up relationships for gas-solids fluidized beds, as reported in the literature, are predominantly validated using global parameters rather than local hydrodynamic parameters. Nonetheless, certain studies emphasize the importance of local hydrodynamic parameters in evaluating scale-up relationships for gas-solids fluidized beds. In this regard, the dimensionless groups scaling relationship of fluidized beds was found to be insufficient to obtain similarity in local hydrodynamic parameters. As a result, an alternative mechanistic approach has been suggested to more precisely characterize the hydrodynamic behavior of fluidized beds. In contrast to traditional scaling approaches based on matching dimensionless groups, the newly developed mechanistic scale-up methodology focuses on achieving hydrodynamic similarity by matching local radial gas holdup profiles between geometrically similar beds. This method is based on the observation that the gas phase governs most hydrodynamic behavior in gas-solid systems. When beds of different sizes exhibit matched radial gas holdup profiles at the same dimensionless heights (z/Dc), other local parameters such as solids holdup and particle velocity also tend to align, enabling meaningful scale-up. This study aims to evaluate the methodology using accurate and industrially feasible measurement techniques. The new approach was validated experimentally using the CT and the RPT [15]. The new mechanistic approach has been validated, however further evaluation should be done, despite the advancement that have been made in order to validate this approach. A second drawback is the difficulty in implementing CT and RPT techniques in industry or fluidized beds of commercial scale. This challenge is compounded by the fact that these techniques are highly customized techniques and difficult to implement. The complex nature of the measurements and the dealing with radioisotopes mean that careful preparation for the experimentation is needed in order to ensure that the measurements are conducted accurately. Considering the mentioned perspective, the aim of this study is to enhance the validation of the new mechanistic scale-up approach for fluidized beds by employing measurement techniques that are more applicable in both industry and laboratories. As such, this work is focused not only on validating the new scale up approach, but on doing so utilizing more accurate measurement techniques that are suited for industrial and laboratory environments. Specifically, this study aims to evaluate the newly proposed mechanistic scale-up methodology through detailed local hydrodynamic measurements. This advancement not only strengthens the theoretical foundation of fluidized bed scale-up but also holds direct practical implications for designing and optimizing industrial-scale gas-solid fluidized reactors. Ensuring similarity in hydrodynamic behavior through matched gas holdup profiles can lead to more predictable performance, reduced design uncertainties, and more efficient process scale-up in industries such as petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, and energy systems. The study involves conducting an extensive array of experiments to measure the hydrodynamic characteristics of the gas-solids fluidized bed, encompassing parameters like gas holdup, solids holdup, and solids velocity. In this study, the terms “small-scale” and “large-scale” fluidized beds refer to two geometrically similar beds with inner diameters of 14 cm and 44 cm, respectively. While the physical difference is diameter, the purpose of the work is to assess a scale-up methodology based on matched local hydrodynamics, rather than to isolate the effect of diameter alone. The term “matched gas holdup profiles” refers to conditions under which the radial gas holdup distributions at corresponding dimensionless axial heights (z/Dc) are nearly identical between the two beds. “Unmatched profiles” indicate notable differences in those distributions. These terms are central to evaluating whether hydrodynamic similarity has been achieved under different operating conditions. Two measurement techniques, optical probe and gamma ray densitometry (GRD), have been selected, both of which can be applied in laboratories and industries. To further investigate the hydrodynamic properties of the fluidized bed, the GRD technique can also be used in an online manner, providing a more comprehensive and real-time analysis.

2 Experimental Set-Up and Measurement Techniques

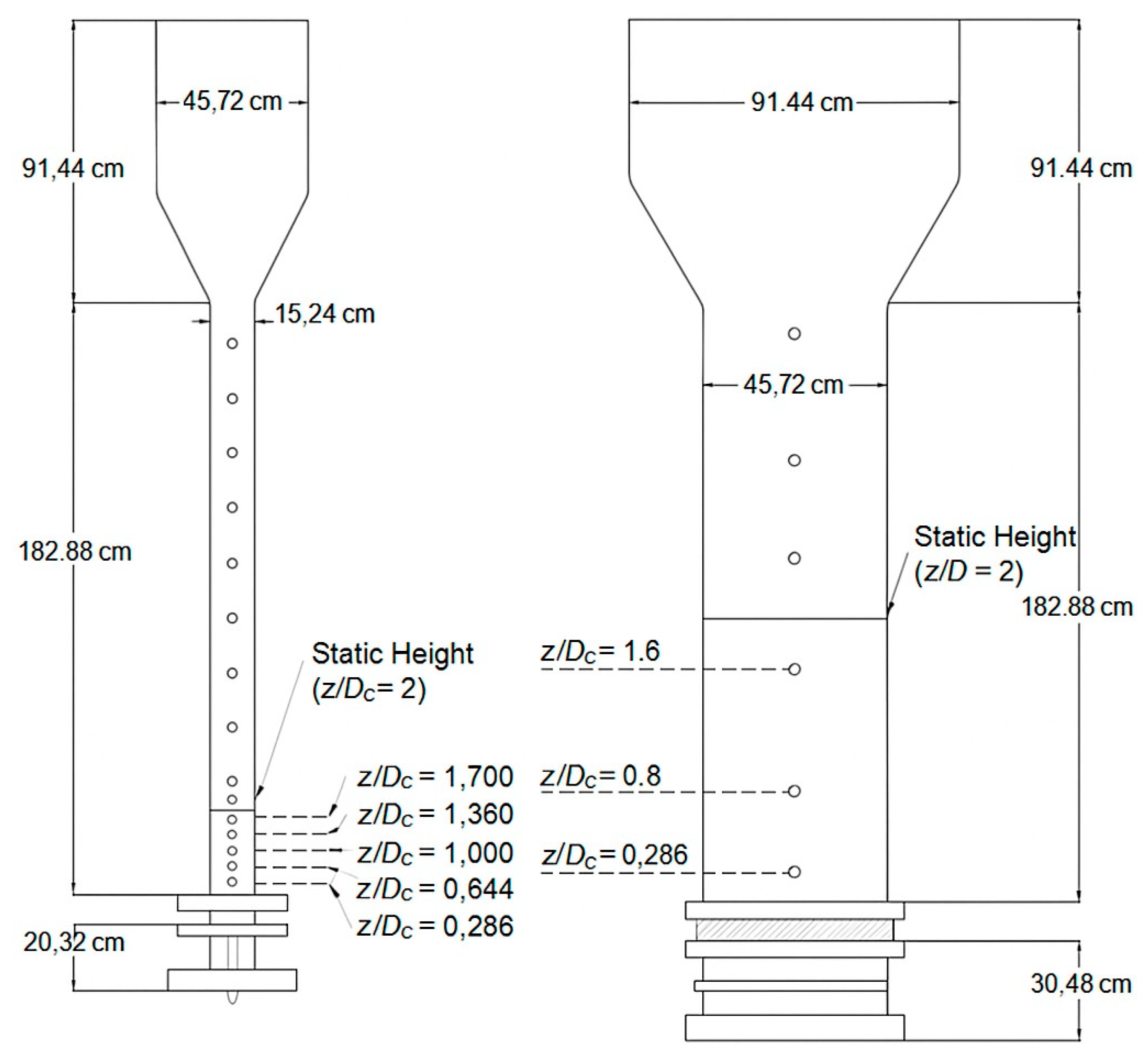

The experiments were conducted in fluidized beds of two distinct sizes, featuring inside diameters of 14 cm m and 44 cm. The two fluidized beds were deigned to be gnomically matched to examine the new scale up approach. The schematic in Fig. 1 displays the dimensions of each bed in greater detail. This study uses a matched setup as that described in the previous study [15,30]. The fluidized bed columns were constructed from Plexiglas, with each column consisting of two components (a column and a cone) joined to a plenum base. This design allowed for the gas, air, or steam to pass through the columns, while the solid particles, such as the catalyst, to be suspended in the air and flow through the column. With an upper section of 44 cm m diameter and 92 cm height, the small column (ID = 14 cm) was about 183 cm in height. Increasing the efficiency of solids separation is attained by lowering the superficial gas velocity of the gas phase within the upper section of the fluidized bed, identified as the disengagement zone. The larger diameter of the upper section of the fluidized bed provided for a greater surface area for solids separation, thus allowing for a reduction in the superficial gas velocity and an overall improvement in the separation of solids. The walls of the beds were equipped with sixteen measurement ports for axial measurements (Fig. 1). In this way, the entire dynamics of fluidized beds can be examined in detail, revealing particle behavior under the investigated conditions. To guarantee stability during measurements, each column is affixed to the upper part of a stainless-steel base. Gas distributors are made of porous polyethylene sheets with pores sizes ranging from 15–40 microns. Situated at the base, the plenum is comprised of a sparger tube. As gas is released into the column through the sparger tube, it creates a fluidized bed in the column. It has fourteen holes oriented downward with respect to the column. The particles are suspended in the gas and are able to move freely, which allows them to be studied in detail. The gas distributors ensure that the gas is evenly distributed throughout the column, and the stainless-steel base prevents the column from shaking or vibrating during measurements. In the large fluidized bed, the inner diameter (ID) was 44 cm, while the upper section height was 1.22 m. This size of the fluidized bed ensured that the air could move freely through the bed, allowing the particles to be suspended and mixed efficiently. Axial measurement ports were also placed on the sides of the large fluidized bed to allow for continuous axial measurements along the entire column. A matched design was used for the distributor as with the small fluidized bed. Within the column, a plenum was positioned at the lower section, featuring a sparger tube. Air was introduced into the bed by means of the connected sparger tube, allowing for a controlled process. The sparger tube had a diameter of 3.81 mm, with seventeen holes facing downward. Aside from that, both columns were electrically grounded in order to minimize the effects of electrostatic discharges. Without the grounding, electrostatic discharges can build up and cause the column to become unstable, which can result in inaccurate readings. A high-capacity air compressor on an industrial scale provided the gas phase with compressed air. The compressor supplies up to 735 cubic feet of air per minute at a pressure up to 200 psig. The air was passed through a filtration system to remove any contaminants before being used. The compressed air was then delivered to the experiment setup. Solids used include glass beads 210 μm and 70 μm in size (Geldart B), with a density of 2500 kg/m3. Fig. 2 presents a photograph depicting both the large-and small-scale gas-solids fluidized beds used in this study. The image also includes the air flow system employed to facilitate fluidization, ensuring controlled and consistent operation. These setups were designed to investigate the hydrodynamic behavior of gas-solid interactions under different conditions, as referenced in [30].

Figure 1: Dimensionless axial measurement levels along with a schematic of the small and large fluidized beds (inner diameters of 14 and 44 cm).

Figure 2: A photograph of the large and small scale gas-solids fluidized beds used in this study, along with the air flow system that was utilized [30].

To assess the developed method of scaling up based on matching gas holdup in gas-solid fluidized beds, two measurement techniques were employed: optical probe and gamma ray densitometry (GRD). The GRD system used in this study poses no radiation risk to personnel. The radioactive source is fully shielded and emits radiation in a collimated beam directed solely toward the detector, minimizing any stray exposure. The GRD and optical probe techniques offer complementary data, enabling a thorough evaluation of the performance of the new scale-up methodology for fluidized beds.

In this investigation, optical probes were utilized to gauge solids holdup (i.e., volume fraction of particles) and solids velocity in the studied gas-solid fluidized bed systems. Optical probes can function as either light emitters or light receivers and are generally categorized as single fibers or multifibers. Multifiber probes, such as the optical probe PV6 used in this study, are equipped with thousands of optical fibers arranged precisely, enabling measurements of solids holdup, solids velocity, and their fluctuations. The PV6 probe, with two channels/tips of optical fibers, features thousands of optical fibers aligned parallel to one another for emitting and reflecting light. These probes offer enhanced precision in measurements due to the elimination of a blind region [33,34]. The PV6 multifiber optical probes measure voltage signals which contain the needed information about solids holdup, solids velocity, and their fluctuations simultaneously. These probes can measure the solids holdup by calculating the ratio between the transmitted and scattered light signals. They can also measure the solids velocity by calculating the difference between the arrival times of the transmitted and scattered light signals. Additionally, they can measure the fluctuations of both the solids holdup and velocity by examining the behavior of the scattered light signal. Since these devices are small, they have little impact on the overall flow structure and are capable of measuring flows rapidly and accurately. This allows for accurate measurements in a wide range of conditions, from very dilute to very dense [33]. The probes are also highly accurate, as they are nearly unaffected by external factors such as temperature, humidity, electrostatics, and electromagnetic fields. This makes them ideal for industrial applications, as well as for academic research. They are also relatively inexpensive and easy to use.

The multifiber optical probe, PV6, utilized in this research was collaboratively developed with the Chinese Academy of Sciences specifically for this study. This optical fiber probe consists of two channels/tips, each housing thousands of fibers arranged parallel to one another, capable of emitting and reflecting light. In addition to the optical fibers, the probes include a photoelectric converter, amplifier circuits, pre-processing signal circuits, and an A/D interface card with the PV6 software. The incorporation of these electronics and software enables the optical probes not only to measure solids velocity but also to capture fluctuations in both solids’ holdup and velocity. The optical fiber probes are also able to detect the scattered light signals, which are then analyzed and processed by the photoelectric converter and amplifying circuits. The signals are then pre-processed and converted into digital signals by the high-speed A/D interface card, which are then analyzed and displayed by the PV6 software. The voltage signals measured by the probes contain the needed information about solids hold up and solids velocity. It is therefore necessary to calibrate the signals in order to convert them into solids holdups and solids velocity data. The calibration procedures for measuring solids holdup and solids velocity have been previously validated and detailed by our research group for the identical gas-solids fluidized beds and particles in other publications. For each measurement, the probe used should not be smaller than the diameter of the particles under study. Therefore, measurements are performed using four different probes, which are selected according to particle size in the investigated operating condition. In order to measure solids holdup, the probe chosen is larger than the investigated particle size. In this way, an adequate measuring volume is ensured for accurate measurements. Whenever particles move in the measuring volume, light is reflected back and captured by the probe. Signals are then generated from this reflected light. Data of any of the tips can be used to determine the solids holdup. In contrast, solid velocity and direction of particles movement (upward or downward) are determined by analyzing signals from both probe tips. Using an optical probe, measurements of solids holdup and solids velocity were conducted at different axial levels and radial positions in both small and large fluidized beds, as depicted in Fig. 1. The measurements were made for eight radial positions along the diameter of the investigated column from its axis to its wall for each axial level. Further details about the development of the PV6 optical probes used in this study, calibration methods, and the PV6 electronics can be found elsewhere. A more detailed description of the optical probe used here can be found elsewhere [30,35].

To assess the efficacy of the newly developed mechanistic scale-up methodology for gas-solid fluidized beds, it is crucial to define experimental conditions that result in both matched and unmatched gas holdup profiles between two fluidized beds. This was accomplished by [15,31,36], who identified experimental conditions in the small-sized fluidized bed that yielded identical or closely matched radial profiles of gas holdup compared to those obtained in the large fluidized bed. The predetermined conditions of the large fluidized beds, originally based on the criteria used by [20], serve as the reference case in this study. Validated computational fluid dynamics (CFD) techniques, as employed by [37], were utilized to determine the conditions that result in matched and unmatched gas holdup profiles in the small-sized fluidized beds. These conditions were subsequently experimentally validated using gamma-ray computed tomography (CT) [15]. Thus, the present study considers three sets of operating conditions: the reference case, the matched gas holdup profile, and the mismatched gas holdup profile, all outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: The investigated operating conditions of matched and unmatched gas holdup profile in fluidized bed for scale-up.

| Condition/Cases | Case | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Matched Gas-Holdup Profile | Unmatched Gas-Holdup Profile | |

| Dc (cm) | 44 | 14 | 14 |

| L (cm) | 487.7 | 477.5 | 4775 |

| H (cm) | 88 | 28 | 28 |

| T (K) | 298 | 298 | 298 |

| P (kPa) | 101 | 101 | 101 |

| Particles | Glass beads | Glass beads | Glass beads |

| dp (mm) | 0.21 | 0.07 | 0.07 |

| ρs (g/cm3) | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.5 |

| ρf (g/cm3) | 0.00121 | 0.00121 | 0.00121 |

| μ (kg/m·h) | 0.639 | 0.639 | 0.639 |

| 36 | 25 | 20 | |

3.1 Examining the Sets of Conditions for Matched and Unmatched Radial Profiles of Gas Holdups Using the Optical Probe Technique

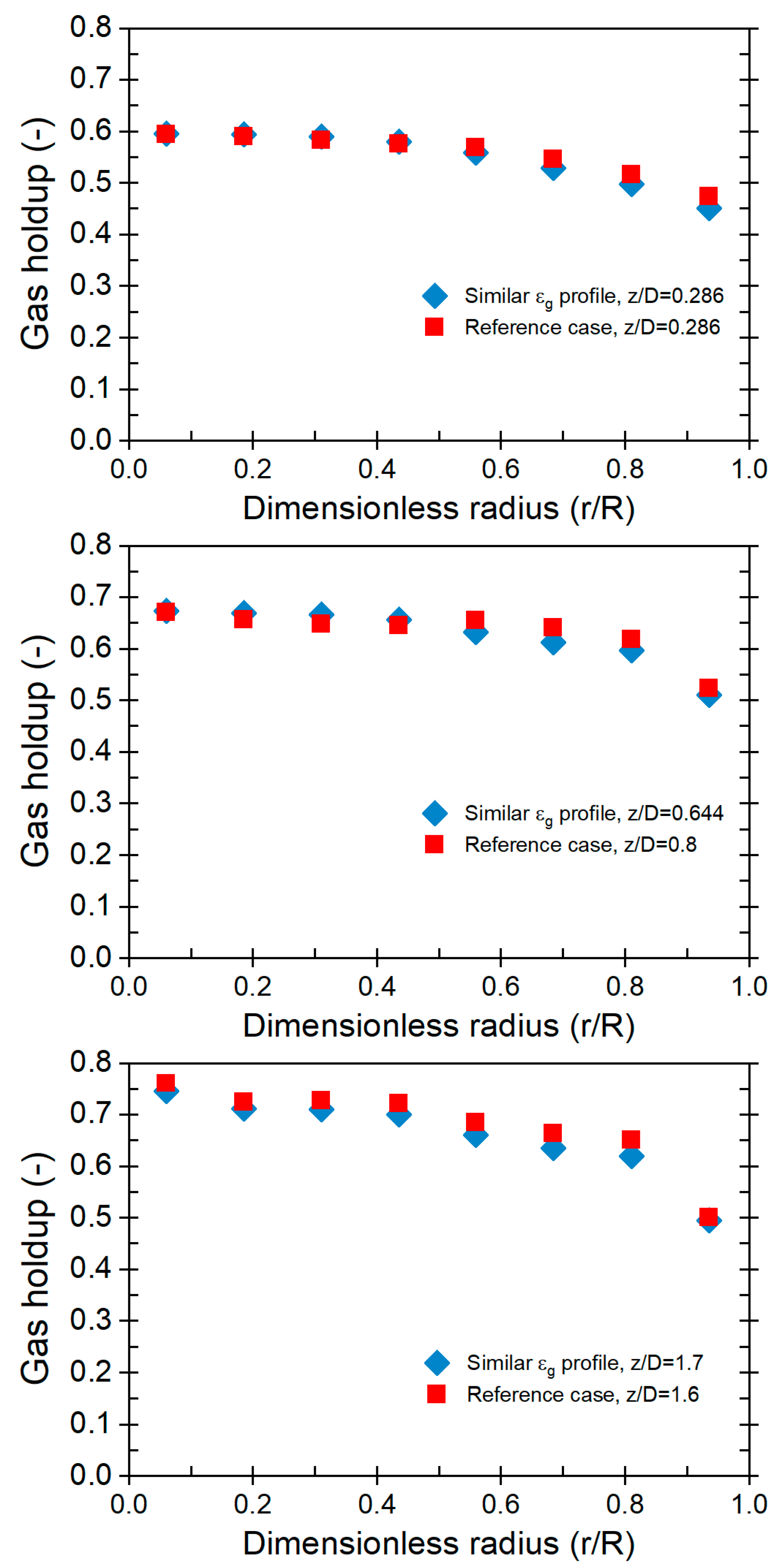

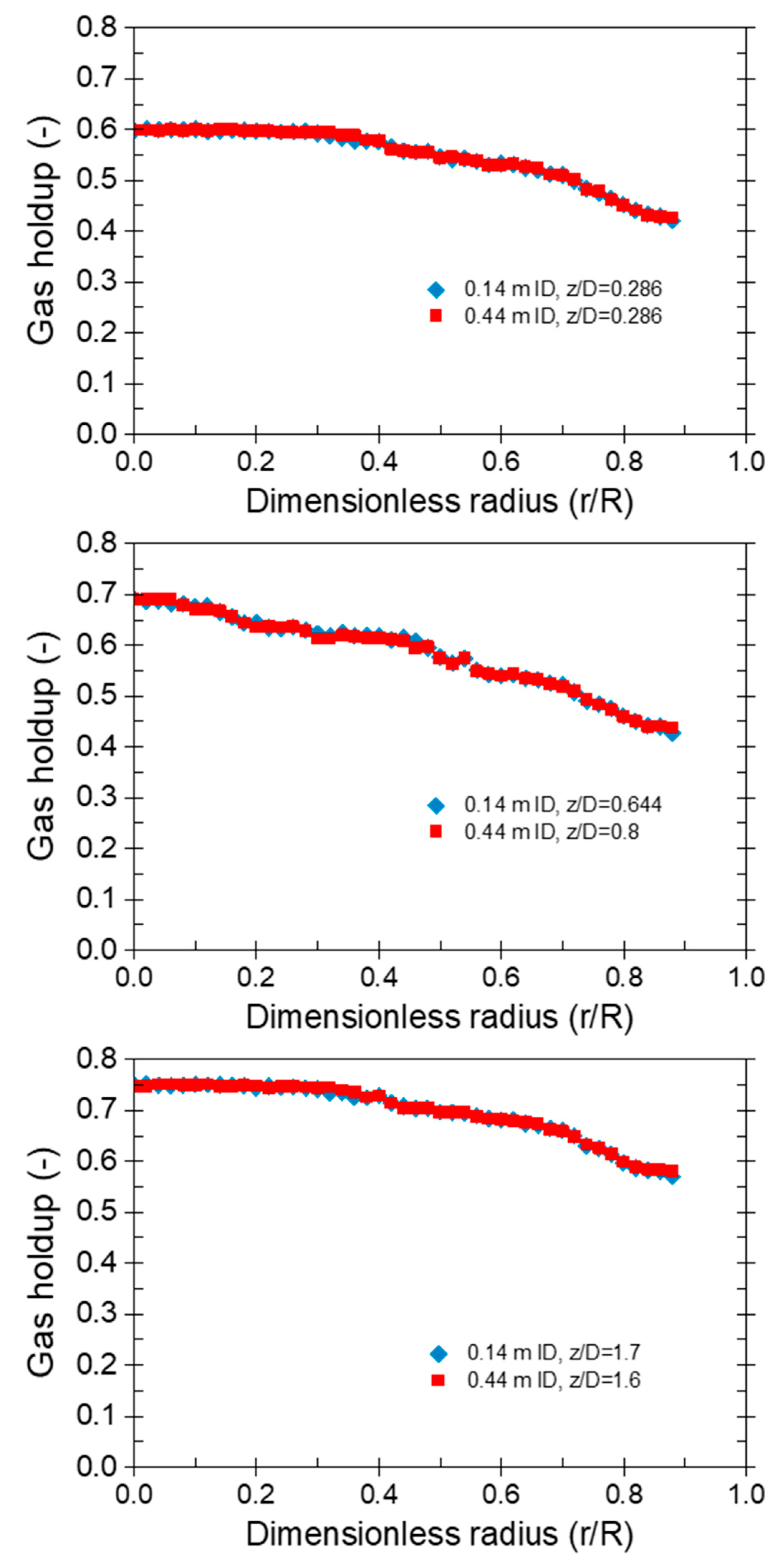

Gas holdup profiles are a critical element in the analysis of fluidized beds, a type of reactor where solid particles are suspended by an upward flow of gas. This dynamic system involves introducing gas at the bed’s bottom, creating a mixture of fluid and gas that fluidizes the bed particles. The gas holdup profile, representing the distribution of gas holdup throughout the bed height, is influenced by various factors such as gas velocity, fluid and particle properties, and bed geometry. Extensive literature underscores the substantial impact of the gas holdup profile on reactor performance, influencing aspects like mixing efficiency and the residence time of particles within the fluidized beds. Optimizing the gas holdup profile is paramount for effectively scaling up and enhancing the overall performance of fluidized bed reactors. To assess the newly developed mechanistic scaling-up method, a study by [31] identified specific conditions for matching and mismatching radial profiles of gas holdups in fluidized beds of different sizes. As a result, the optical probe has been used in this section to measure radial gas holdup profiles at various dimensionless axial levels (z/Dc) for both large (44 cm ID) and small (14 cm ID) fluidized beds. The results (Fig. 3) unveiled a noteworthy trend, indicating an increase in gas holdup with decreasing z/Dc levels for both large and small beds. Specifically, the highest gas holdup was observed at the lowest z/Dc level (0.286), while the lowest was registered at the highest z/Dc level. Comparing gas holdup profiles between the large and small beds under matched conditions exhibited minimal mean absolute deviation percent (MAD%) (2.05%, 2.59%, 2.87%) at z/Dc levels of 0.28, 0.88, and 1.6, respectively, affirming the achievement of matched gas holdup profiles. To further explore the significance of unmatched conditions, gas holdup profiles were scrutinized in 14 cm IDC fluidized beds. The findings demonstrated evident disparities between the large and small beds at all z/Dc levels, with differences intensifying as z/Dc levels decreased. The mean percentage differences for unmatched gas holdup conditions were calculated as 10.95%, 15.20%, and 18.79% at z/DC levels of 0.28, 0.88, and 1.6, respectively. These results underscore the consequential impact of unmatched gas holdup profiles, leading to distinct behaviors between large and small fluidized beds. Conclusively, further investigations are essential to ascertain whether matching gas holdup profiles between the two beds guarantees hydrodynamic similarity. This necessitates an examination of various parameters, including solids holdup and particle velocity. If these parameters align, it can be inferred that the hydrodynamics of the two beds are matched, validating the efficacy of the newly developed mechanistic scale-up methodology.

As part of assessing the newly scale-up methodology for gas-solids fluidized beds, it was essential to investigate conditions resulting in unmatched gas holdup radial profiles in the smaller fluidized bed. An examination of the gas holdup profile for operation conditions with un-matched gas holdup radial profiles has been carried out in the 14 cm inner diameter fluidized beds. In Fig. 4, the radial profiles of gas holdup for the reference case are compared with the radial profiles of gas holdup for the case with unmatched gas holdup profiles along the height of the beds. Both large and small fluidized beds exhibit discrepancies in profiles at all levels of z/Dc. The results indicate that, at all z/Dc axial levels, the gas holdup radial profiles of the larger fluidized bed surpass those of the smaller bed, with the difference in-creasing as the z/Dc axial levels decrease. At z/Dc levels of 0.28, 0.88, and 1.6, respectively, the MAD between the profiles was 10.95%, 15.20%, and 18.79%. These findings confirm that unmatched gas holdup profile conditions lead to divergent gas holdup profiles be-tween the larger and smaller fluidized beds.

Figure 3: Gas holdup radial profiles for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Matched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

Figure 4: Gas holdup radial profiles for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Unmatched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

3.2 Evaluating the Newly Developed Mechanistic Scale-Up Methodology Using the Optical Probe Technique

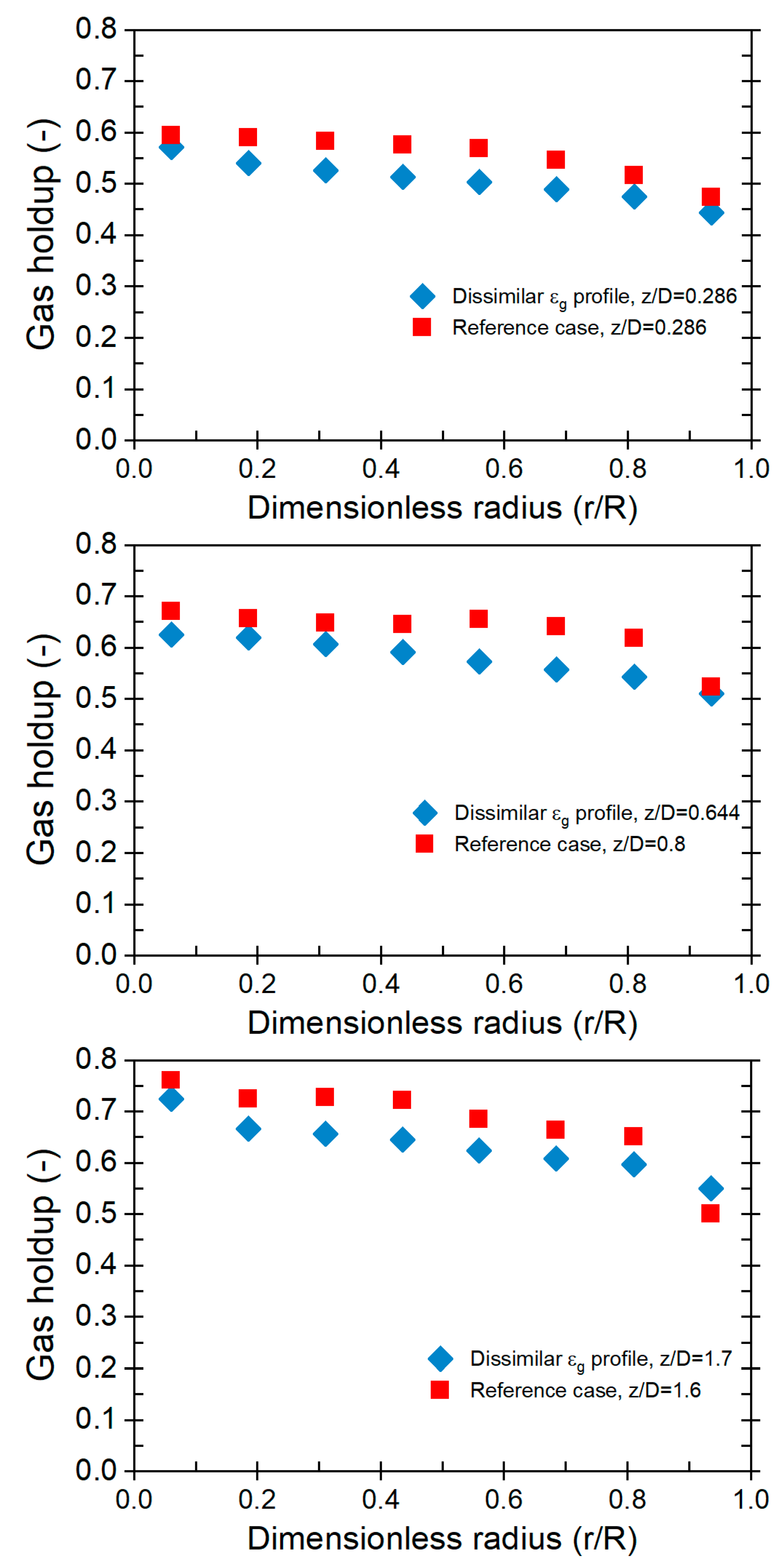

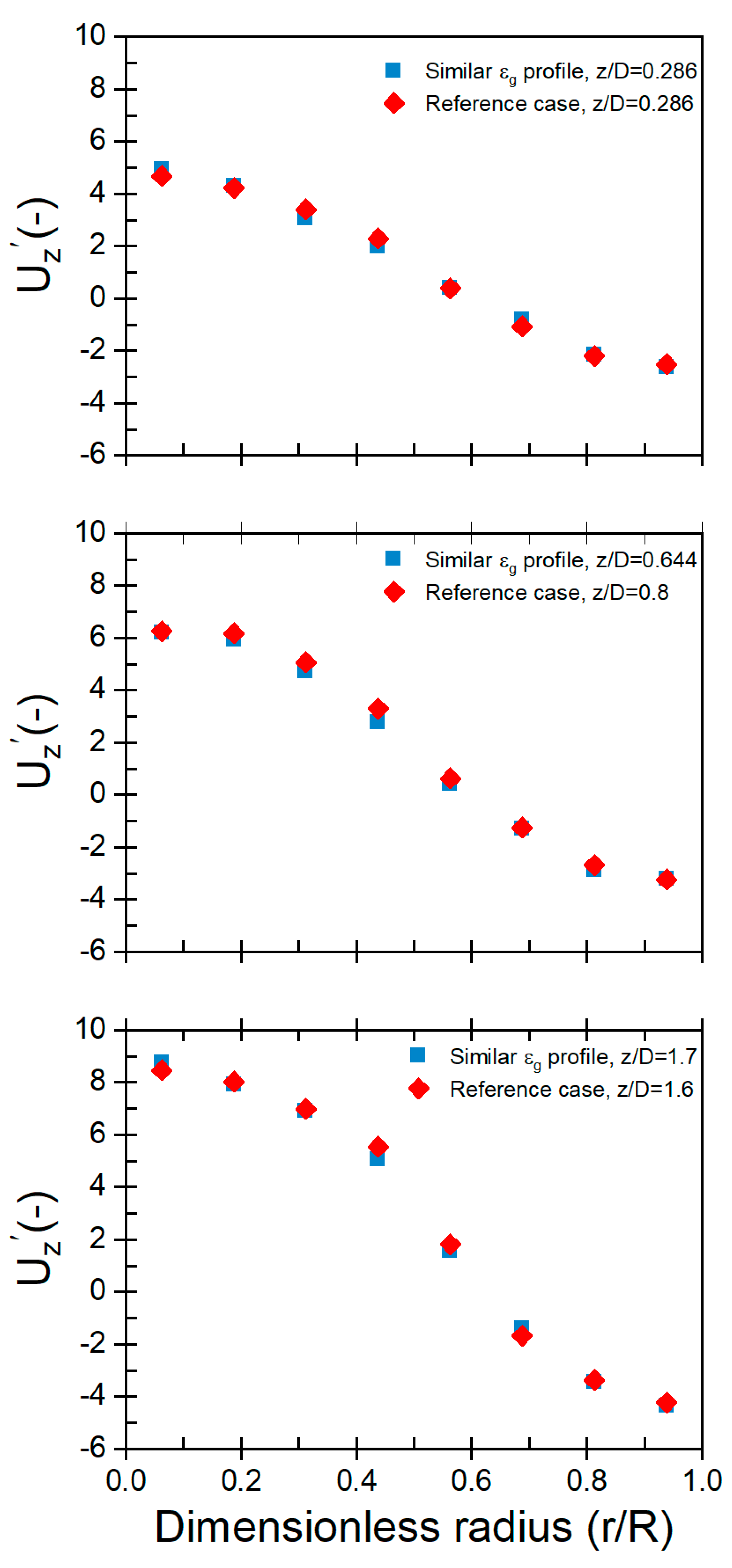

The solids holdup profile is crucial for understanding the distribution of solids within a bed, playing a pivotal role in various industrial applications. Evaluating the solids holdup profile for cases involving the reference, matched, and unmatched gas holdup profiles offers a comprehensive examination of the newly-developed mechanistic scale-up methodology. Illustrated in Fig. 5 are the radial profiles of solid holdup for the reference case and matched gas holdup profiles at different z/Dc levels for both large (44 cm IDC) and small (14 cm IDC) fluidized beds. The results reveal that solids holdup in gas-solid fluidized beds increases with the axial height of the bed, attributed to heightened pressure gradients resisting fluidization. Comparing profiles between the two beds shows closely matched solids holdup radial profiles for the reference case and conditions of the matched gas holdup profile. Notably, at the fully developed region (z/Dc = 1.7), the Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) between profiles is a mere 2.05%, suggesting substantial similarity in solids holdup profiles. Even in the middle and sparger regions, MAD values of 2.59% and 2.05%, respectively, indicate pronounced similarity, demonstrating that matched solids holdup profiles were achieved despite the differences in bed sizes. This successful alignment of solids holdup profiles supports the conclusion that the new mechanistic scale-up approach effectively ensures hydrodynamic consistency between fluidized beds of different sizes, provided matched gas holdup profiles are maintained. This is a promising development for scaling up industrial processes, enhancing operational efficiency, and ensuring consistent product quality.

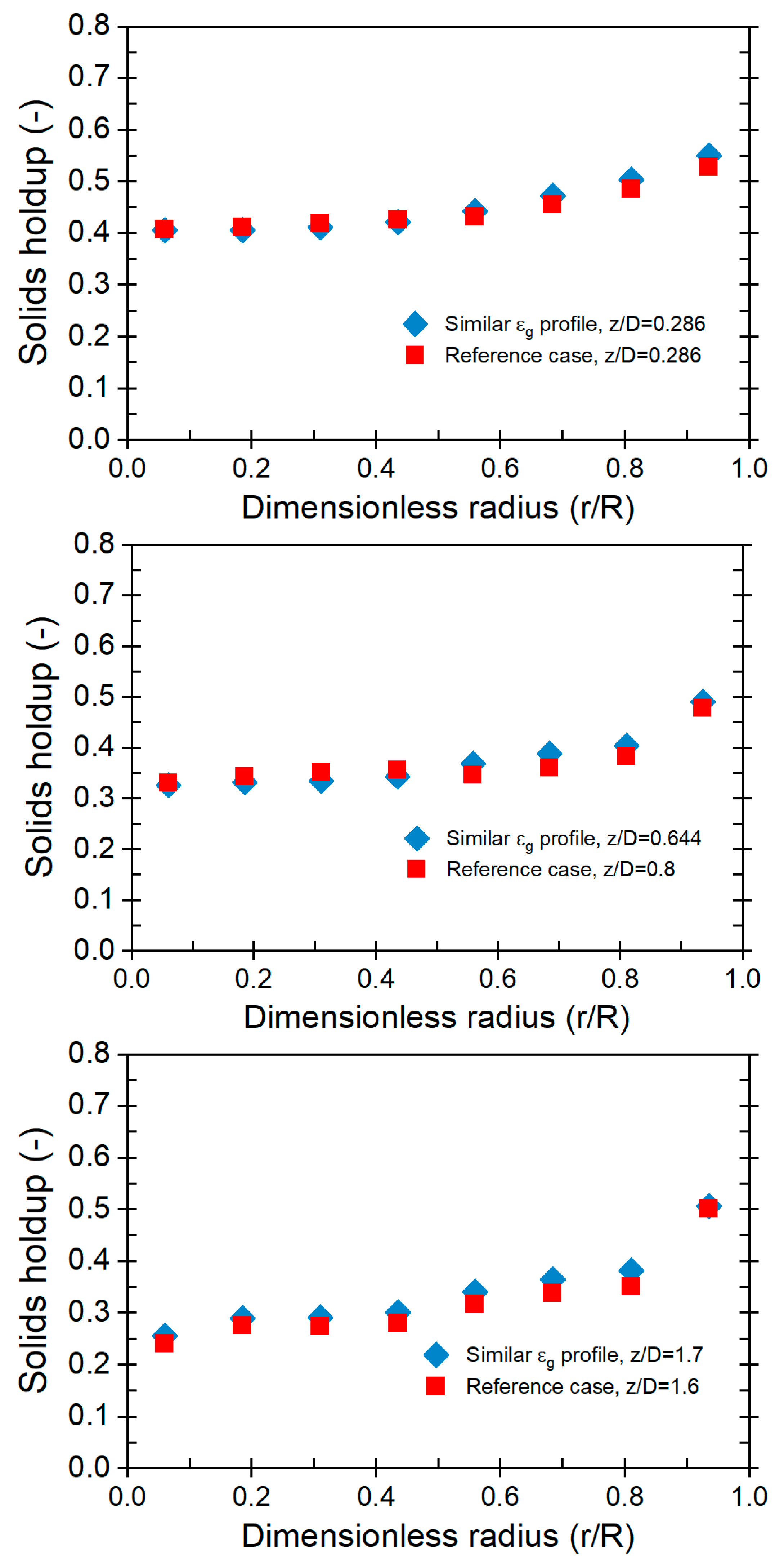

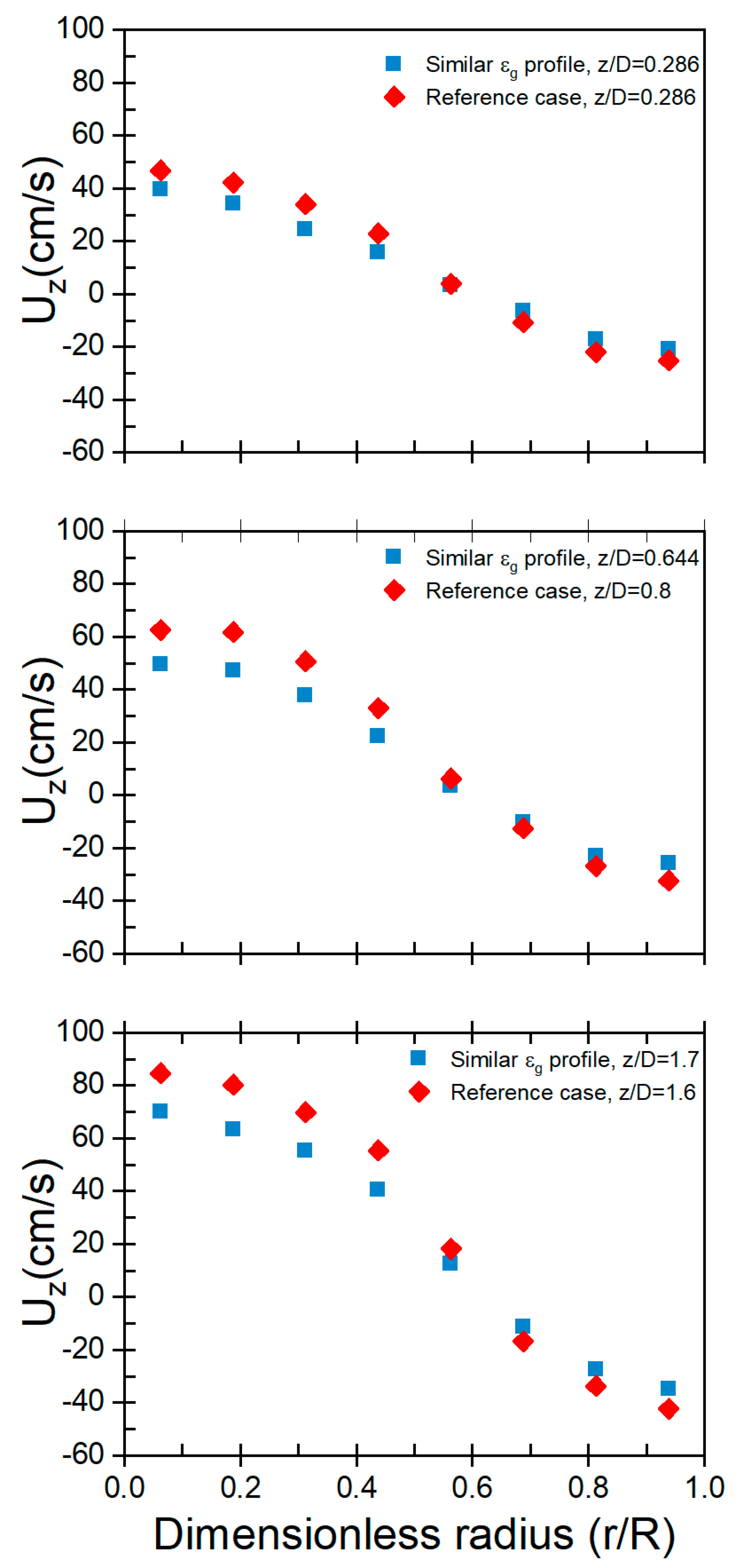

Furthermore, the assessment of the newly developed mechanistic scale-up methodology extends to particle velocity, evaluated using the optical probe technique in both large and small fluidized beds. Fig. 6 displays local particle velocity profiles for cases involving the reference and matched gas holdup profiles at different z/Dc levels. Particle velocity profiles in gas-solid fluidized beds vary with operating conditions. As gas flow rates increase, particles transition from stationary to fluidized states, influencing their motion and the bed’s expansion. Results indicate an increase in particle velocity with decreasing z/Dc levels for both large and small beds across the three defined regions: lower dilute, intermediate transport, and upper fully developed. Comparing particle velocity profiles reveals differences in values for the axial particle velocity between the reference case and those of matched and unmatched gas holdup profiles, with lesser disparities for the matched gas holdup profile. The Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) values further quantify these differences. For the matched gas holdup profile case, MAD values range from 23.96% to 24.91% across various z/Dc levels, while the unmatched gas holdup profile case exhibits higher MAD values ranging from 29.87% to 30.13%. This nuanced analysis provides deeper insights into the effectiveness of the new scale-up methodology and its impact on achieving hydrodynamic similarity, crucial for refining industrial processes.

Utilizing the radial profiles of solids velocity within both fluidized beds, the up-flow particles velocity was normalized by expressing it as a dimensionless value, obtained by dividing the solids velocity by the minimum fluidization velocity (Umf). In the context of fluidization, the bed initiates fluidization at a specific velocity, and below this threshold, it remains non-fluidized. The determination of the minimum fluidization velocity involves measuring the pressure drop across a bed of particles as a function of gas velocity. This crucial parameter signifies the point at which the bed undergoes fluidization, and any particles exceeding this velocity will be entrained with the gas. Moreover, the congruence between measured and calculated values was observed to be exceptional when employing the appropriate correlation as detailed by [38]. For the fluidized bed with a diameter of 0.14 m, employing glass beads with mean particle sizes of 70 mm and 210 mm yielded Umf values of 0.06 m/s and 0.12 m/s, respectively. In the case of the 44 cm bed diameter utilizing glass beads with a mean particle size of 210 mm, the corresponding Umf was determined to be 0.105 m/s. This alignment between measured and calculated Umf values reinforces the reliability of the selected correlation and affirms the applicability of the minimum fluidization velocity in characterizing fluidized bed behavior.

Fig. 7 shows the dimensionless local particle velocity profiles for Cases reference and matched gas holdup profiles at different z/Dc levels. It is pronounced from the figures that the difference between the profiles of the two cases has been reduced. The MAD between the two profiles in the fully developed region (z/Dc = 1.6) was about 6.17%. As the height decreased to z/Dc = 0.644, the ARD increased to 9.01%, while at H/D = 0.286, which is the sparger region, the MAD decreased to 7.92%. This reduction in the difference between the profiles means that as matching gas holdup profiles increased, the MAD decreased, indicating that matching gas holdup is beneficial for reducing the difference in the profiles. The results indicate that matching gas holdup profiles between two fluidized beds of different sizes lead to the similarity in terms of dimensionless particle velocity. This is likely due to the fact that when gas holdup profiles are matched, the amount of gas available for mixing is also matched. This helps to equalize the forces acting on the fluidized bed and causes the dimensionless velocity to be the same in both beds. The results indicate that the new mechanistic scale-up approach was successful in achieving hydrodynamic similarity between two gas-solid fluidized beds with matched gas holdup profiles. Fluidized beds of different sizes with comparable gas holdup profiles can be hydrodynamically consistent using the mechanistic approach. Therefore, industrial processes can be scaled up more efficiently, resulting in a higher quality product and more efficient operation. This approach eliminates the need for extensive trial and error testing to determine the ideal scale-up parameters, saving time and resources. Furthermore, it ensures that the hydrodynamic behavior of the system is matched to that of the industrial-scale system, which is essential for achieving consistent product quality and process efficiency.

Figure 5: Solids holdup radial profiles for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Matched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

Figure 6: Radial profiles of axial particle velocity for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Matched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

Figure 7: Radial profiles of dimensionless axial particle velocity for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Matched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

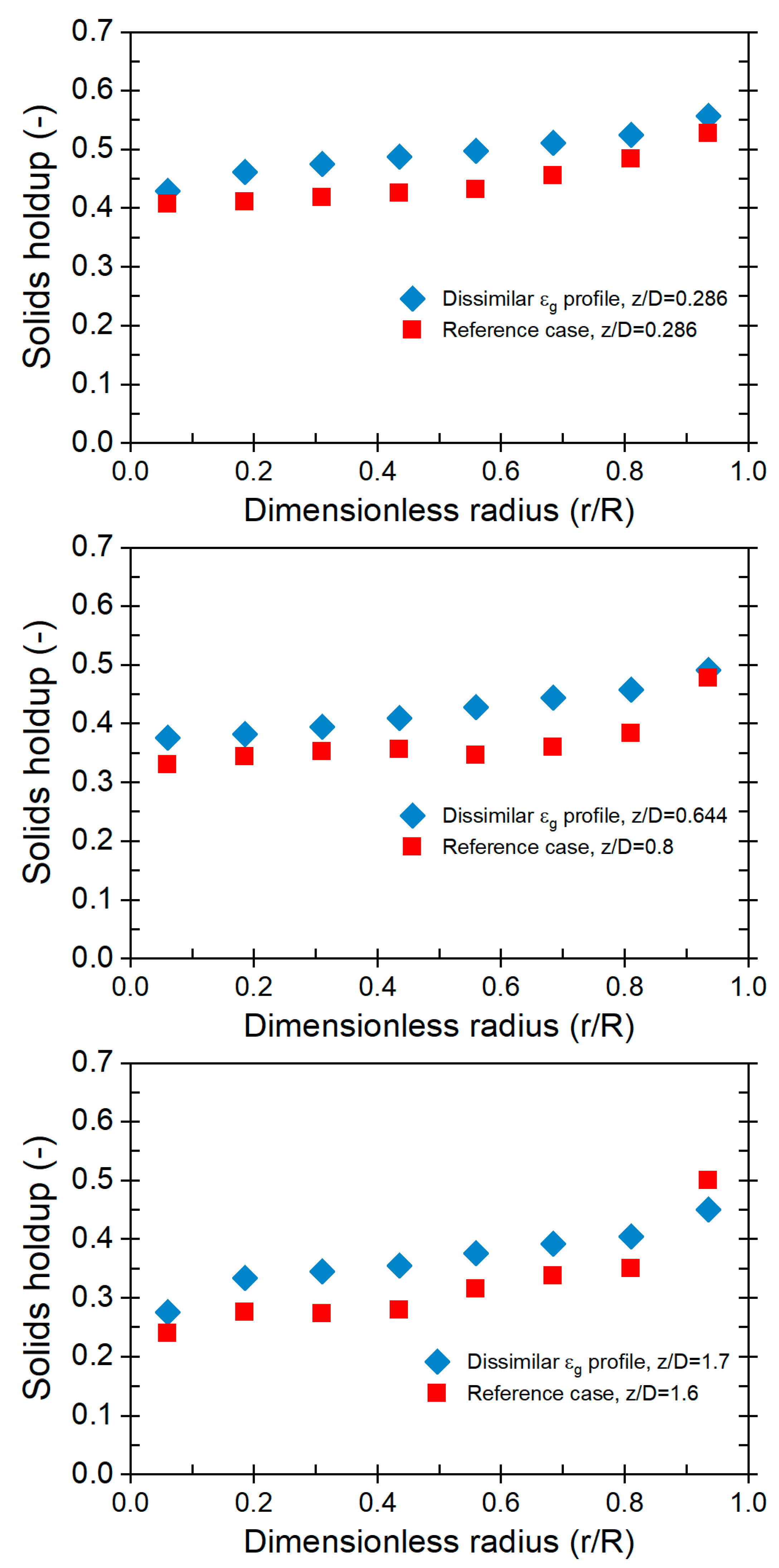

In Fig. 8, a comparison of solids holdup radial profiles is presented between the reference case and unmatched gas holdup profiles at various z/Dc levels. The profiles reveal substantial disparities in the radial distribution of solids holdup between the large and small fluidized beds across all z/Dc levels. Specifically, in the fully developed region of both beds (at z/Dc = 1.6), the Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) between the solid’s holdup profiles reaches 18.79%, while in the intermediate region (at z/Dc = 0.88), the MAD between the profiles is 15.20%. The sparser regions (at z/Dc = 0.286) exhibit a MAD of 10.95%, indicating a significant deviation between the profiles. These results emphasize that achieving hydrodynamic similarity between the two beds becomes challenging under unmatched gas holdup profile conditions. Thus, maintaining matched gas holdup profiles is crucial for establishing hydrodynamic similarity, ensuring accurate predictions, and facilitating the effective scale-up of fluidized bed reactors. The findings underscore the importance of maintaining matching radial profiles of gas holdup for reliable and consistent fluidized bed performance.

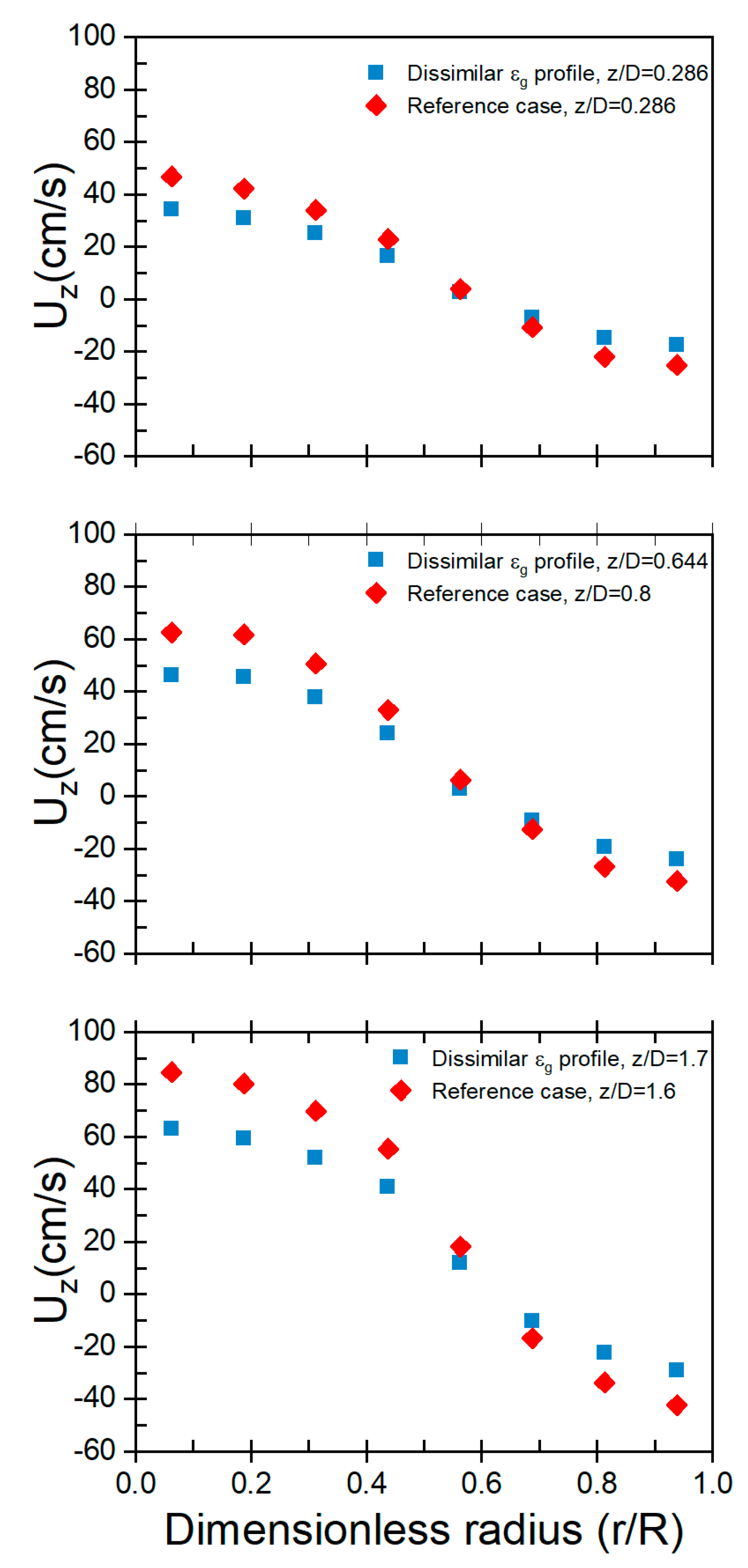

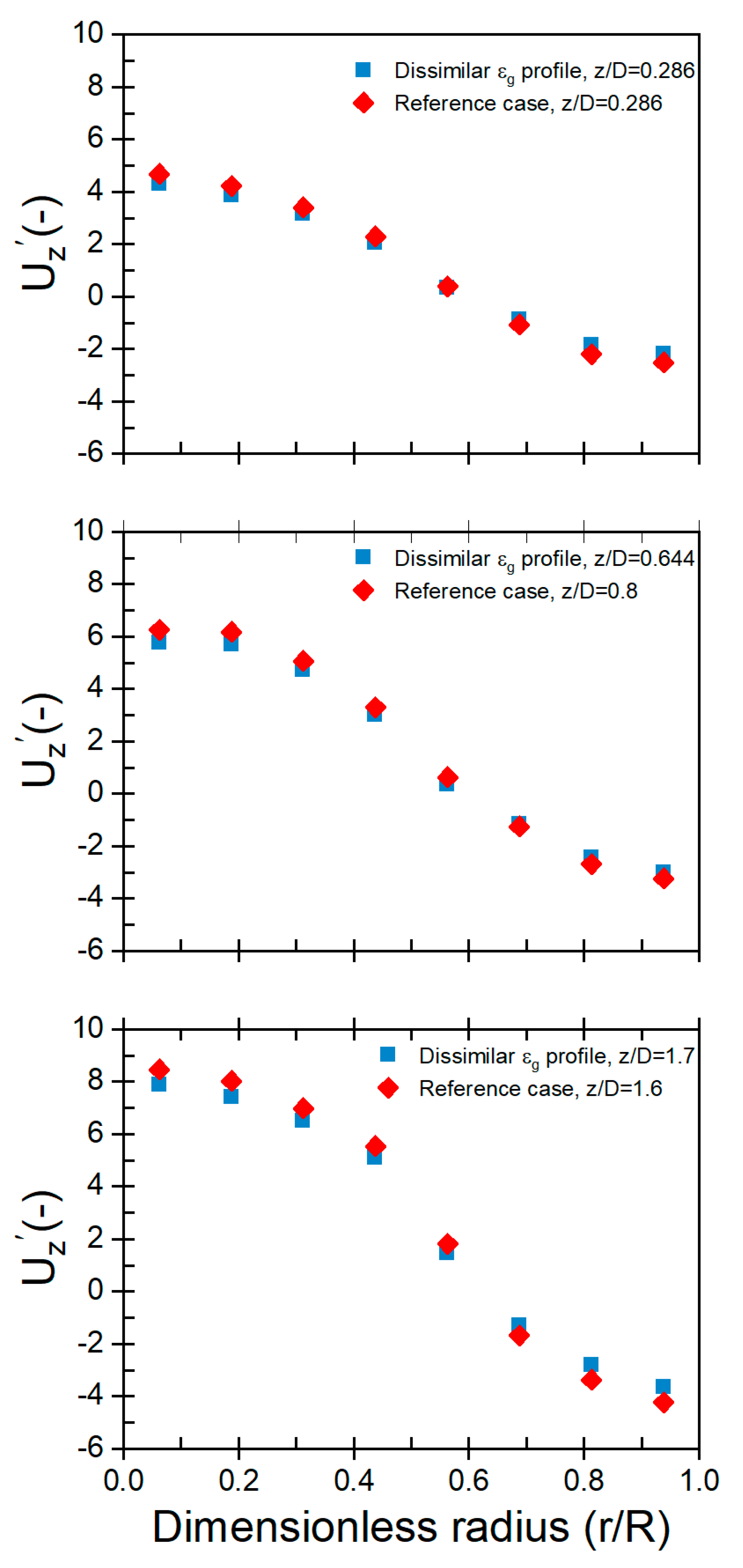

Fig. 9 depicts local particle velocity profiles for Cases reference and Unmatched gas holdup profiles at different z/Dc levels. The MAD values are 29.87% at z/Dc = 0.286, 29.57% at z/Dc = 0.644, and 30.13% at z/Dc = 1.6. The variation in gas holdup profiles between the two beds contributes to differences in local particle velocity. This discrepancy may stem from the prolonged retention of particles in the bed with higher gas holdup, leading to elevated local particle velocities. Conversely, the bed with lower gas holdup may experience less gas-induced retardation, resulting in lower local particle velocities. Non-dimensionalizing the profiles mitigates some differences (Fig. 10), with MAD values of 12.34% at z/Dc = 0.286, 11.96% at z/Dc = 0.644, and 12.66% at z/Dc = 1.6. These outcomes underscore the impracticality of achieving robust hydrodynamic similarity between the two beds when gas holdup profiles are unmatched. Therefore, maintaining matched gas holdup profiles is imperative for sustaining hydrodynamic similarity. While matching gas holdup profiles is pivotal, it’s important to note that other factors, such as bed geometry, fluid properties, and flow parameters, also significantly influence hydrodynamic similarity. Thorough analysis of these parameters, considering their potential variations over time, is essential for achieving and maintaining consistent hydrodynamic similarity.

Figure 8: Solids holdup radial profiles for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Unmatched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

Figure 9: Radial profiles of axial particle velocity for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Unmatched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

Figure 10: Radial profiles of dimensionless axial particle velocity for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Unmatched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

3.3 Demostrating the Use of CFD to Enable the Implemention of the Newly Devloped Mechanistic Scale-Up Methodology

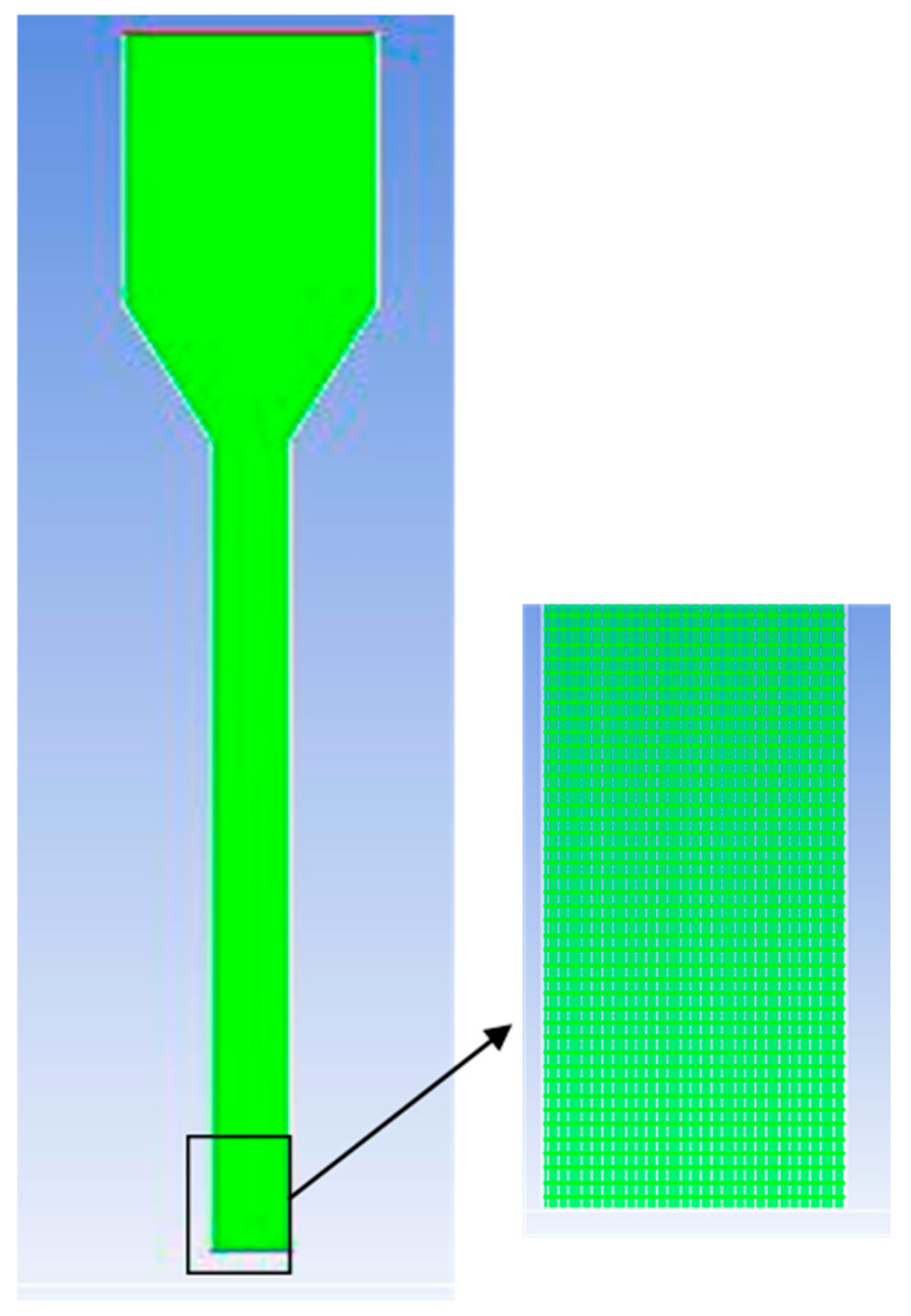

To validate the practical application of the developed mechanistic scale-up approach, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) assumed a crucial role as the primary tool in the preliminary stage. An Eulerian–Eulerian approach was used for simulating the gas–solid fluidized bed using ANSYS FLUENT 12.0 [39]. Both gas and solid phases were modeled as interpenetrating continua with separate sets of conservation equations and appropriate coupling terms. The kinetic theory of granular flow was applied to describe particle interactions. The simulation geometry matched the actual beds used in experiments, and a 2D axisymmetric model was adopted to reduce computational load. Meshes were generated in GAMBIT 2.4 and imported into FLUENT. A transient simulation was performed using a time step of 0.001 s and approximately 20 iterations per time step. The Phase Coupled SIMPLE algorithm was used for pressure–velocity coupling, and a first-order upwind scheme was used for discretizing the momentum, volume fraction, and turbulence equations. The simulation was considered converged when the residuals of all governing equations dropped below 1 × 10−5. Despite the limitations of using first-order discretization and a 2D domain, the model reasonably captured key hydrodynamic features. To address mesh quality and accuracy, a grid independence study was performed to ensure the reliability of the results. Three different grid sizes were tested, with average cell sizes of 2.0 mm, 3.0 mm, and 4.0 mm. The 3.0 mm grid was selected as optimal, offering a balance between computational cost and accuracy, as further mesh refinement yielded negligible improvements (<1% deviation in gas holdup predictions). The selected mesh resolution ensured at least 6–10 cells per minimum particle diameter (dp = 0.21 mm), consistent with best practices in gas–solid fluidized bed CFD simulations. A schematic representation of the mesh grid layout is presented in Fig. 11. In terms of model selection and parameter justification, the Eulerian–Eulerian two-fluid model was chosen due to its suitability for large-scale fluidized beds where particle-scale resolution (as in DEM) is computationally prohibitive. The kinetic theory of granular flow was applied to model the solid-phase stress tensor, and standard closure models for drag and turbulence (e.g., Gidaspow drag model and k–ε turbulence model) were used in accordance with validated literature on similar systems. The primary objective of the CFD was to pinpoint conditions leading to matched and closely aligned radial profiles and cross-sectional distributions of gas holdup within the fluidized bed systems. This computational analysis laid the foundation for subsequent experimental investigations, providing insightful perspectives into the dynamics of gas distribution across beds of varying sizes. The integration of CFD allowed for a systematic exploration of operational parameters, enhancing the understanding of the intricate behavior of fluidized beds and facilitating the optimization of the scale-up process. After conducting numerous CFD simulations, the conditions outlined in Table 1 were identified, resulting in matched gas holdup profiles between large and small fluidized beds. Experimental validation of these trial results confirmed their consistency. The CFD outcomes not only underscored the accuracy and reliability of the scale-up methodology but also demonstrated its efficacy in achieving matched gas holdup profiles between fluidized beds of different sizes. Fig. 12 depicts the gas holdup radial profiles obtained through CFD for Cases Reference and Matched gas holdup profiles in fluidized beds with sizes of 44 cm and 14 cm at various z/Dc levels. The results from CFD showcased its effectiveness in consistently achieving gas holdup profiles between fluidized beds of different sizes, substantiating the reliability of the scale-up methodology. Notably, the gas holdup profiles exhibited high consistency, with a Mean Absolute Deviation (MAD) of less than 5% at all levels. It is crucial to acknowledge a slight discrepancy between the CFD results and those obtained through the optical probe near the wall. This disparity may be attributed to the use of two-dimensional simulation and first-order upwind schemes for characterization, along with potential closures that warrant further scrutiny for proper validation in future assessments.

Figure 11: 2D axisymmetric mesh structure used for CFD simulation of the gas-solid fluidized bed.

Figure 12: Gas holdup radial profiles obtained using CFD for the conditions of Cases Reference, and Matched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 44 cm IDC and 14 cm IDC at different z/Dc levels.

3.4 On-Line Monitoring of and Enabling Fluidized Bed Hydrodynamics Similarity Scaling

Gamma Ray Densitometry (GRD) stands out as a valuable and widely utilized technique across various industries, offering insights into critical parameters such as line-averaged phase holdup, flow regimes, and malfunction flow. Notable for its non-invasive nature, GRD provides a means to analyze and assess the scale-up of opaque multiphase flow systems without disrupting their natural flow. This quality makes it particularly suitable for applications in both laboratory and industrial settings, where maintaining the integrity of the system is paramount. The key principle behind GRD lies in the attenuation of gamma rays as they traverse through a system. When gamma rays encounter matter, their interaction involves scattering or absorption, dependent on the composition and density of the material. In the context of GRD, a Cs-137 gamma ray source directs radiation towards a specific axial level, with a detector strategically placed on the opposite side to capture the transmitted gamma rays. The detected intensity is then used to derive the line-averaged profile of phase holdup within the system. One of the major advantages of GRD is its ability to provide valuable data swiftly and cost-effectively. The technique is adept at gauging various flow parameters without physically interfering with the system under observation. This versatility has led to widespread adoption in diverse applications across industries.

To delve into the technicalities of GRD, the attenuation of gamma rays is harnessed to determine the line-averaged holdup within the system. Utilizing Beer Lambert’s Law, the attenuation coefficient (μatt) is calculated, taking into account the incident and detected radiation intensities, medium density, and the path length through the medium. The system’s composition is considered, especially when it involves multiple materials such as solids and gas, each contributing to the overall attenuation. The process involves sophisticated calculations to determine the line-averaged holdup, considering the volumetric fractions (holdups) of solids (

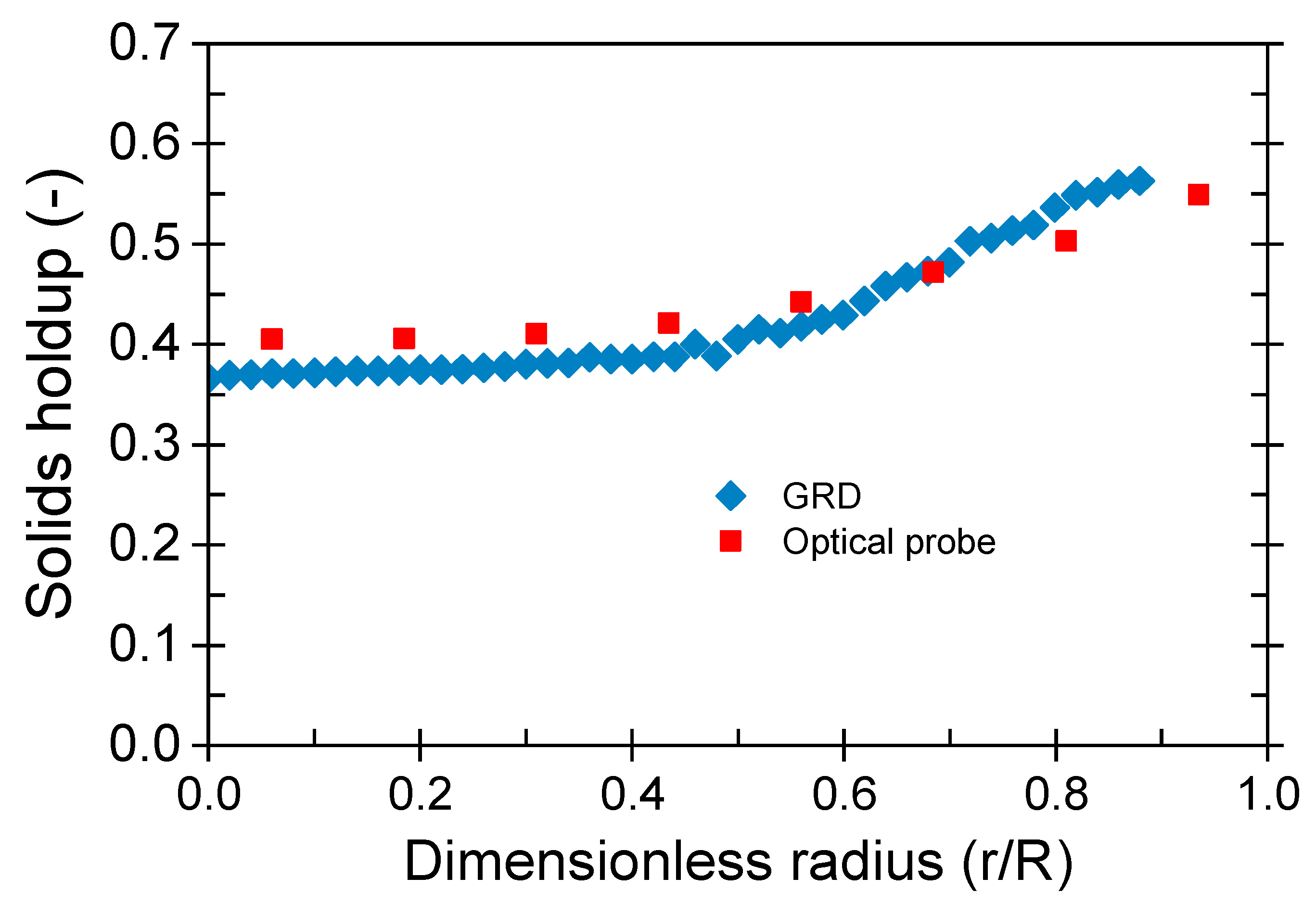

Fig. 13 shows the solids holdup profile obtained using the optical probe and the GRD for the conditions of Matched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 14 cm IDC at z/Dc = 0.286. The results of the two techniques are in good agreement. The GRD, however, shows greater solids holdup near the fluidized beds wall. This is because GRD is a more sensitive technique than the traditional one, and thus can detect small changes in solids holdup that other techniques may not be able to. The purpose here is demonstrating the scale up methodology and the way in which more accurate and simple techniques can be applied for online measurement to laboratories and industrial scales. By demonstrating the advantages of GRD over the traditional technique, this study highlights the potential of GRD for online measurement of solids holdup in fluidized beds, which can be further applied to laboratories and industrial scales. GRD provides higher accuracy and better resolution than the traditional methods, and its advantages include faster measurements, lower costs, and reduced labor requirements. Furthermore, GRD can be used to detect solids holdup in real-time, allowing for more accurate control of processing parameters.

Figure 13: Solids holdup radial profiles obtained using optical the probe and the GRD for the conditions of Matched gas holdup profiles for fluidized beds with 14 cm IDC at z/Dc = 0.286.

In this study, the effectiveness of the newly scaling-up approach, centered around aligning gas holdup profiles, is verified for local hydrodynamic parameters in gas-solid fluidized beds. The experimental setup utilized two fluidized beds with diameters of 44 cm and 14 cm. Three distinct operational scenarios were investigated: a reference case, conditions with matched gas holdup profiles, and conditions with unmatched gas holdup profiles. Advanced techniques, including an optical probe and gamma ray densitometry (GRD), were employed for precise measurements. The results underscored the significance of achieving identical or closely matched hydrodynamic outcomes by maintaining consistent radial profiles of gas holdup in geometrically similar beds. Notably, when gas holdup profiles were matched, a similarity in hydrodynamics was observed between small-scale and large-scale gas-solid fluidized beds. Conversely, significant disparities emerged when radial profiles of gas holdup differed between the two bed sizes. This discrepancy can be attributed to the influential role of gas holdup profiles in shaping fluid flow within the bed. Matching gas holdup profiles ensured similar fluid flow, yielding congruent hydrodynamic results. Conversely, divergent gas holdup profiles led to dissimilar fluid flow and unmatched hydrodynamic outcomes. These findings align with and validate previous studies, particularly those referenced in [15]. Moreover, the results highlight the governing influence of the gas phase on the hydrodynamics of gas-solid fluidized beds. The radial profile of gas holdup emerges as a representative parameter, emphasizing the crucial role of gas phase dynamics in the solids flow field of fluidized beds. Additionally, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) emerges as a valuable tool for evaluating operating conditions that yield matched gas holdup profiles in both small-and large-scale gas-solid fluidized beds, as detailed earlier. This new scale-up methodology proves applicable to gas-solid fluidized beds of varying scales. Its utility extends to swiftly and accurately identifying optimal operating conditions for such beds, offering potential applications in both the design of new systems and the optimization of existing fluidized beds.

The implementation of the innovative scale-up methodology for gas-solid fluidized beds involves a systematic approach outlined in several key steps. In the initial phase, gas holdup profiles are meticulously measured at designated dimensionless heights for the fluidized beds targeted for scaling, utilizing non-invasive techniques such as Gamma-ray densitometry (GRD) to ensure accurate and undisturbed flow measurements. Subsequently, validated computational fluid dynamics (CFD) is employed for scaled fluidized beds, ensuring geometric matching and striving for gas holdup profiles that closely align with the reference case. The construction and operation of scaled gas-solids fluidized beds follow, adhering to the conditions identified through CFD. The subsequent step involves measuring radial gas holdup profiles at specific dimensionless heights and refining operating conditions, if necessary, to achieve profiles that match those of the reference case. This systematic procedure enables the assessment and validation of the scale-up methodology, contributing to improved understanding and optimization of gas-solid fluidized bed processes.

It is advisable to adhere to the subsequent procedures when implementing the scale-up methodology for gas-solid fluidized beds:

- I.Measure Gas Holdup Profiles:

- a.Conduct gas holdup measurements at a designated dimensionless height for the fluidized beds intended for scaling, encompassing the sparger region, intermediate transport region, and the upper fully developed region.

- b.Utilize non-invasive measurement techniques to prevent disturbance to the flow, with recommended methods like Gamma-ray densitometry (GRD) offering reliable online measurements for both laboratory and industrial applications.

- c.The reference case involves fluidized beds and their respective operating conditions.

- II.Validate CFD for Scaled Fluidized Beds:

- a.Implement validated computational fluid dynamics (CFD) for scaled fluidized beds (small or large) to obtain gas holdup profiles matching those from the reference case.

- b.Ensure geometric matching of scaled fluidized beds according to the specified scale-up approach.

- c.If achieving matching gas holdup profiles with CFD is challenging, consider obtaining closer profiles, recognizing that increased similarity in hydrodynamic behavior correlates with closer radial gas holdup profiles.

- III.Develop and Operate Scaled Beds: Construct and operate scaled gas-solids fluidized beds under the conditions identified in Step II to maximize similarity.

- IV.Measure Radial Gas Holdup Profiles: At selected dimensionless heights and operating conditions for the scaled fluidized bed constructed in Step III, measure radial gas holdup profiles.

- V.Refine Operating Conditions: As necessary, refine the operating conditions identified in Step III to achieve gas holdup profiles matched to the reference case.

Although the methodology has not yet been fully deployed in industrial units, its foundation on measurable local hydrodynamic parameters—particularly gas holdup—makes it suitable for industrial application. The use of scalable and non-invasive techniques like GRD supports future integration into commercial-scale fluidized bed systems.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Methodology, Faraj M. Zaid, Thaar M. Aljuwaya and Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Validation, Faraj M. Zaid; Formal Analysis, Faraj M. Zaid, Thaar M. Aljuwaya and Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Investigation, Faraj M. Zaid, Thaar M. Aljuwaya and Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Resources, Faraj M. Zaid and Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Data Curation, Faraj M. Zaid; Writing—Original Draft, Faraj M. Zaid, Thaar M. Aljuwaya and Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Writing—Review & Editing, Thaar M. Aljuwaya and Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Visualization, Thaar M. Aljuwaya; Supervision, Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan; Funding Acquisition, Muthanna H. Al-Dahhan. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Symbols | |

| particle size in centimeters | |

| inner column diameter in centimeters | |

| acceleration due to gravity in centimeters per second squared (cm/s2) | |

| length of the column, in centimeters | |

| pressure within the bed, in Pascals | |

| radius of the column, in centimeters | |

| distance from the column axis in centimeters | |

| dimensionless radial distance | |

| fluidized bed temperature in Kelvin | |

| gas phase superficial velocity, centimeters per second | |

| minimum fluidization velocity, centimeters per second | |

| axial distance from the bed’s inlet orifice, centimeters | |

| Greek Letters | |

| particle density, expressed in grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm3) | |

| fluid density, expressed in grams per cubic centimeter (g/cm3) | |

| fluid viscosity, expressed in kilograms per meter per hour (kg/(m·h)) | |

| attenuation coefficient of mass | |

| Density | |

| particle sphericity | |

| gas fraction (or gas holdup) | |

| solids fraction (or solids holdup) | |

| Subscripts | |

| Dimensionless parameter | |

| inner diameter | |

References

1. Sun Y , Sage V , Sun Z . An enhanced process of using direct fluidized bed calcination of shrimp shell for biodiesel catalyst preparation. Chem Eng Res Des. 2017; 126: 142– 52. doi:10.1016/j.cherd.2017.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Zhao Y , Li C , Shi X , Gao J , Lan X . Simulation analysis of CO2 in situ enrichment technology of fluidized catalytic cracking regenerator. Powder Technol. 2024; 434: 119386. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2024.119386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Erdiwansyah , Mahidin , Husin H , Nasaruddin , Muhtadin , Faisal M , et al. Combustion efficiency in a fluidized-bed combustor with a modified perforated plate for air distribution. Processes. 2021; 9( 9): 1489. doi:10.3390/pr9091489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Git P , Hofmeister M , Singer RF , Körner C . Fluidization behavior of graphitized glassy particles in a fluidized carbon bed cooling process for investment casting. Particuology. 2022; 65: 32– 8. doi:10.1016/j.partic.2021.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhuang H , Chen X , Feng T . Research on technology of medicinal functional food. Processes. 2022; 10( 8): 1509. doi:10.3390/pr10081509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Coppola A , Scala F , Azadi M . Direct dry carbonation of mining and industrial wastes in a fluidized bed for offsetting carbon emissions. Processes. 2022; 10( 3): 582. doi:10.3390/pr10030582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang R , Hoffmann T , Tsotsas E . Novel technique for coating of fine particles using fluidized bed and aerosol atomizer. Processes. 2020; 8( 12): 1525. doi:10.3390/pr8121525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Ali N , Al-Juwaya T , Al-Dahhan M . An advanced evaluation of spouted beds scale-up for coating TRISO nuclear fuel particles using radioactive particle tracking (RPT). Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2017; 80: 90– 104. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2016.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang S , Shen Y . Particle-scale modelling of the pyrolysis of end-of-life solar panel particles in fluidized bed reactors. Resour Conserv Recycl. 2022; 183: 106378. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2022.106378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Żukowski W , Jankowski D , Wrona J , Berkowicz-Płatek G . Combustion behavior and pollutant emission characteristics of polymers and biomass in a bubbling fluidized bed reactor. Energy. 2023; 263: 125953. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.125953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang S , Shen Y . Coarse-grained CFD-DEM modelling of dense gas-solid reacting flow. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2022; 184: 122302. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.122302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Hadian M , de Munck MJA , Buist KA , Bos ANR , Kuipers JAM . Modeling of a catalytic fluidized bed reactor via coupled CFD-DEM with MGM: from intra-particle scale to reactor scale. Chem Eng Sci. 2024; 284: 119473. doi:10.1016/j.ces.2023.119473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Horio M , Nonaka A , Sawa Y , Muchi I . A new similarity rule for fluidized bed scale-up. AlChE J. 1986; 32( 9): 1466– 82. doi:10.1002/aic.690320908. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Efhaima A , Al-Dahhan MH . Assessment of scale-up dimensionless groups methodology of gas-solid fluidized beds using advanced non-invasive measurement techniques (CT and RPT). Can J Chem Eng. 2017; 95( 4): 656– 69. doi:10.1002/cjce.22745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Efhaima A , Al-Dahhan MH . Validation of the new mechanistic scale-up of gas-solid fluidized beds using advanced non-invasive measurement techniques. Can J Chem Eng. 2021; 99( 9): 1984– 2002. doi:10.1002/cjce.23938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Glicksman LR . Scaling relationships for fluidized beds. Chem Eng Sci. 1984; 39( 9): 1373– 9. doi:10.1016/0009-2509(84)80070-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nicastro MT , Glicksman LR . Experimental verification of scaling relationships for fluidized bed. Chem Eng Sci. 1984; 39( 9): 1381– 91. doi:10.1016/0009-2509(84)80071-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Schouten JC , Vander Stappen MLM , Van Den Bleek CM . Scale-up of chaotic fluidized bed hydrodynamics. Chem Eng Sci. 1996; 51( 10): 1991– 2000. doi:10.1016/0009-2509(96)00056-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Mabrouk R , Radmanesh R , Chaouki J , Guy C . Scale effects on fluidized bed hydrodynamics. Int J Chem React Eng. 2005; 3 (1). doi:10.2202/1542-6580.1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Glicksman LR , Hyre M , Woloshun K . Simplified scaling relationships for fluidized beds. Powder Technol. 1993; 77( 2): 177– 99. doi:10.1016/0032-5910(93)80055-F. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Knowlton TM , Karri SBR , Issangya A . Scale-up of fluidized-bed hydrodynamics. Powder Technol. 2005; 150( 2): 72– 7. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2004.11.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Patience GS , Chaouki J , Berruti F , Wong R . Scaling considerations for circulating fluidized bed risers. Powder Technol. 1992; 72( 1): 31– 7. doi:10.1016/S0032-5910(92)85018-Q. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rüdisüli M , Schildhauer TJ , Biollaz SMA , van Ommen JR . Scale-up of bubbling fluidized bed reactors—a review. Powder Technol. 2012; 217: 21– 38. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2011.10.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Frye CG , Lake WC , Eckstrom HC . Gas-solid contacting with ozone decomposition reaction. AlChE J. 1958; 4( 4): 403– 8. doi:10.1002/aic.690040405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Chen W , Hasegawa T , Tsutsumi A , Otawara K . Scale-up effects on the time-averaged and dynamic behavior in bubble column reactors. Chem Eng Sci. 2001; 56( 21–22): 6149– 55. doi:10.1016/S0009-2509(01)00231-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. van Ommen JR , Teuling M , Nijenhuis J , van Wachem BGM . Computational validation of the scaling rules for fluidized beds. Powder Technol. 2006; 163( 1–2): 32– 40. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2006.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Romero JB . Factors affecting fluidized bed quality [ dissertation]. Seattle, WA, USA: University of Washington; 1959. [Google Scholar]

28. Broadhurst T , Becker H . The application of the theory of dimensions to fluidized beds. In: Proceedings of the International Symposium, Fluidization and Its Applications; 1973 Oct 1–5; Toulouse, France. p. 10– 27. [Google Scholar]

29. Stein M , Ding YL , Seville JPK . Experimental verification of the scaling relationships for bubbling gas-fluidised beds using the PEPT technique. Chem Eng Sci. 2002; 57( 17): 3649– 58. doi:10.1016/S0009-2509(02)00264-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Zaid FM , Al-Rubaye H , Aljuwaya TM , Al-Dahhan MH . Assessment of the dimensionless groups-based scale-up of gas-solid fluidized beds. Processes. 2023; 11( 1): 168. doi:10.3390/pr11010168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zaid MH . Gas-solid fluidized bed reactors: scale-up, flow regimes identification and hydrodynamics [ dissertation]. Rolla, MO, USA: Missouri University of Science and Technology; 2013. [Google Scholar]

32. Taofeeq H , Al-Dahhan M . Comparison between the new mechanistic and the chaos scale-up methods for gas-solid fluidized beds. Chin J Chem Eng. 2018; 26( 6): 1401– 11. doi:10.1016/j.cjche.2018.03.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang H , Johnston PM , Zhu JX , de Lasa HI , Bergougnou MA . A novel calibration procedure for a fiber optic solids concentration probe. Powder Technol. 1998; 100( 2–3): 260– 72. doi:10.1016/S0032-5910(98)00147-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Wang Z , Bi HT , Lim CJ . Measurements of local flow structures of conical spouted beds by optical fibre probes. Can J Chem Eng. 2009; 87( 2): 264– 73. doi:10.1002/cjce.20157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Taofeeq H , Aradhya S , Shao J , Al-Dahhan M . Advance optical fiber probe for simultaneous measurements of solids holdup and particles velocity using simple calibration methods for gas-solid fluidization systems. Flow Meas Instrum. 2018; 63: 18– 32. doi:10.1016/j.flowmeasinst.2018.07.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kumar SB , Moslemian D , Duduković MP . Gas-holdup measurements in bubble columns using computed tomography. AIChE J. 1997; 43( 6): 1414– 25. doi:10.1002/aic.690430605 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Al-Dahhan M , Aradhya S , Zaid F , Ali N , Aljuwaya T . Scale-up and on-line monitoring of gas-solid systems using advanced and non-invasive measurement techniques. Procedia Eng. 2014; 83: 469– 76. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2014.09.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Fogler HS , Brown LF . Predictions of fluidized bed operation under two limiting conditions: reaction control and transport control. In: Chemical reactors. Washington, DC, USA: American Chemical Society; 1981. p. 31– 54. doi:10.1021/bk-1981-0168.ch003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Enwald H , Peirano E , Almstedt AE . Eulerian two-phase flow theory applied to fluidization. Int J Multiph Flow. 1996; 22: 21– 66. doi:10.1016/S0301-9322(96)90004-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools