Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Deep Learning-Based Investigation of Multiphase Flow and Heat Transfer in CO2–Water Enhanced Geothermal Systems

PetroChina Chuanqing Drilling & Exploration Engineering Co., Ltd., Chengdu, 610051, China

* Corresponding Author: Feng He. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multiphase Fluid Flow Behaviors in Oil, Gas, Water, and Solid Systems during CCUS Processes in Hydrocarbon Reservoirs)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(10), 2557-2577. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.070186

Received 10 July 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

This study introduces a Transformer-based multimodal fusion framework for simulating multiphase flow and heat transfer in carbon dioxide (CO2)–water enhanced geothermal systems (EGS). The model integrates geological parameters, thermal gradients, and control schedules to enable fast and accurate prediction of complex reservoir dynamics. The main contributions are: (i) development of a workflow that couples physics-based reservoir simulation with a Transformer neural network architecture, (ii) design of physics-guided loss functions to enforce conservation of mass and energy, (iii) application of the surrogate model to closed-loop optimization using a differential evolution (DE) algorithm, and (iv) incorporation of economic performance metrics, such as net present value (NPV), into decision support. The proposed framework achieves root mean square error (RMSE) of 3–5%, mean absolute error (MAE) below 4%, and coefficients of determination greater than 0.95 across multiple prediction targets, including production rates, pressure distributions, and temperature fields. When compared with recurrent neural network (RNN) baselines such as gated recurrent units (GRU) and long short-term memory networks (LSTM), as well as a physics-informed reduced-order model, the Transformer-based approach demonstrates superior accuracy and computational efficiency. Optimization experiments further show a 15–20% improvement in NPV, highlighting the framework’s potential for real-time forecasting, optimization, and decision-making in geothermal reservoir engineering.Keywords

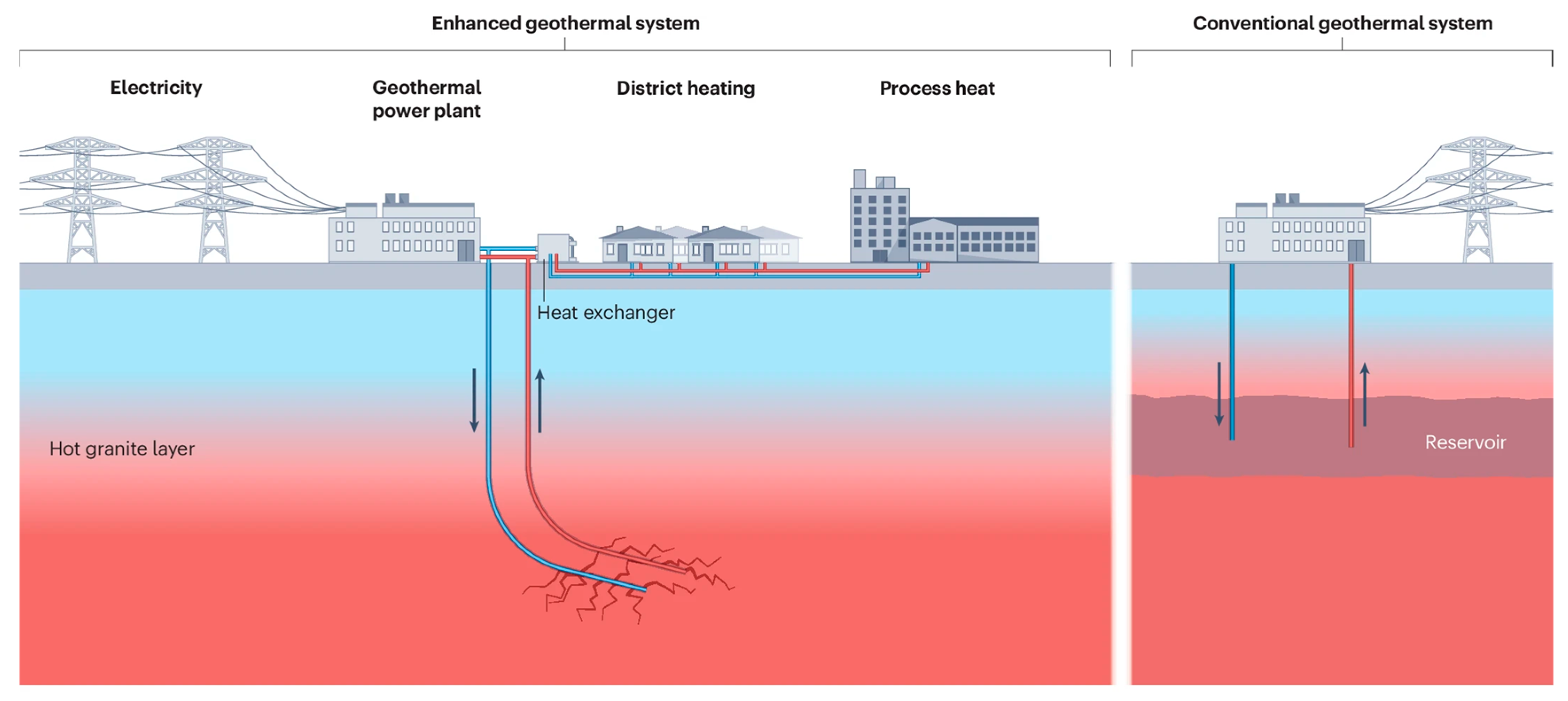

To address global warming and meet growing energy demands, identifying sustainable energy alternatives has become a critical worldwide priority [1]. Geothermal energy, as a clean and renewable subsurface resource, has emerged as a promising candidate to replace conventional fossil fuels due to its abundant availability and low carbon footprint [2]. In several countries, geothermal energy significantly contributes to electricity generation; for instance, geothermal sources account for 44% of installed power capacity in Kenya, 27% in Iceland, 26% in El Salvador, and 18% in New Zealand [3]. Moreover, geothermal energy is recognized as one of the most effective strategies for achieving decarbonization goals due to its substantial potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with projections suggesting a reduction exceeding one billion tons of carbon emissions by 2050 [4]. Hot dry rock (HDR), a specific category of geothermal resources, offers considerable potential for converting subsurface heat into electricity, typically harnessed through enhanced geothermal systems (EGS), in which water is widely utilized as the primary heat-transfer fluid [5,6] (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Enhanced geothermal systems.

However, recently proposed CO2-enhanced geothermal systems (CO2-EGS), which integrate heat extraction with carbon sequestration, have attracted increasing attention due to their dual benefits [7]. In such systems, supercritical CO2 (sCO2) is injected into HDR reservoirs for heat extraction. Compared to traditional water-based EGS, CO2-EGS demonstrates several advantages [8]. First, sCO2 exhibits significantly higher mobility and injectivity approximately two to five times greater than water enabling increased mass flow rates under equivalent pressure gradients and consequently enhancing heat extraction efficiency by up to 50% [9]. Second, due to its high compressibility, sCO2 can serve as a promising medium for large-scale energy storage. Additionally, the low mineral solubility in sCO2 mitigates scaling and corrosion issues in wellbores and pipelines, thus enhancing system reliability and lifespan [10]. Given that CO2-water EGS performance strongly depends on geological and operational conditions, feasibility analysis is critical prior to field deployment. Previous studies employing reservoir simulators have substantially improved our understanding of key physical mechanisms in CO2-water EGS, including equations of state, multicomponent multiphase flow, heat transfer, CO2 plume migration, and potential mineral reactions [11,12]. Reservoir simulation results facilitate assessment of critical performance indicators, such as thermal extraction efficiency, carbon sequestration capacity, and system longevity [13]. Nevertheless, comprehensive analyses and optimization of CO2-water-EGS systems remain computationally challenging, primarily due to the substantial computational cost associated with thermal-hydrological-chemical (THC) simulations, especially for three-dimensional, field-scale models [14,15,16].

Reduced-order models (ROMs) offer an efficient approach to significantly decrease computational costs in simulations while maintaining acceptable accuracy [17,18,19,20]. In recent years, ROMs have been extensively applied across various computational physics domains, including hydrocarbon recovery, geothermal energy extraction, and carbon dioxide sequestration [21]. In geothermal engineering, ROM techniques enable efficient predictions of critical reservoir parameters, such as pressure, temperature, and stress fields, by leveraging available training datasets [22,23,24]. For instance, Bassam et al. proposed an artificial neural network (ANN)-based approach to characterize geothermal reservoirs with inclined and vertical geometries [25]. These surrogate models can effectively replace traditional numerical simulators in complex geothermal reservoir simulations, significantly reducing computational cost while maintaining satisfactory accuracy [26,27]. Consequently, deep-learning-based ROMs have become powerful tools for uncertainty quantification, inverse modeling, and optimization in geothermal applications [28,29]. Wang et al. proposed a deep learning-based closed-loop optimization framework for geothermal reservoir well control, integrating a hybrid convolution-recurrent neural network surrogate with differential evolution and iterative ensemble smoothing, achieving efficient real-time optimization and uncertainty reduction in reservoir management [30].

In summary, the present study develops a multimodal-fusion Transformer surrogate to accelerate the simulation and optimization of CO2–water enhanced geothermal systems. Unlike existing data-driven approaches, the proposed framework explicitly integrates geological heterogeneity, operational controls, and physical-field tensors within a unified architecture. The main contributions of this work are fourfold:

- 1.Workflow design: We establish a complete workflow that couples high-fidelity multiphase-thermal simulations with a Transformer-based surrogate, enabling accurate three-dimensional prediction of reservoir dynamics.

- 2.Physics-guided loss functions: We introduce mass-balance, energy-conservation, and bound-preserving penalties to enhance physical consistency of the network outputs.

- 3.Closed-loop optimization: The surrogate is coupled with a differential evolution algorithm to enable real-time optimization of injection strategies under multiple economic and operational objectives.

- 4.Economic assessment: The framework incorporates net present value (NPV) as a direct optimization metric, providing a practical tool for decision support in geothermal engineering.

Through this combination of physical insight and deep learning, the proposed approach provides both computational efficiency and practical applicability, paving the way for real-time forecasting and optimization in next-generation geothermal energy development.

In this section, we detail the multimodal fusion Transformer agent model and optimization workflow.

The physical reservoir simulations were performed using CMG-STARS, a robust numerical simulator capable of solving nonlinear systems governing multiphase, multicomponent fluid flow and heat transport in multidimensional porous media. To simplify numerical modeling, several reasonable assumptions were adopted: (1) chemical reactions within the reservoir were neglected; (2) mechanical effects were not considered; and (3) fluid flow was assumed to follow Darcy’s law.

In this study, the geothermal system involved a mixture of CO2 and water as working fluids. Fluid flow through the reservoir matrix was described by a mass conservation equation based on Darcy’s law, expressed as follows:

In this study, the reservoir is assumed to be in local thermal equilibrium, implying instantaneous thermal equilibrium between the fluid and rock matrix. Thus, heat transfer within the porous medium can be described using a single conservation equation, as given in Eq. (3):

2.2 Deep Learning Surrogate Model

CO2-water EGS numerical simulations typically require significant computational resources due to the complex calculations involved in phase equilibrium and heat transfer, resulting in low computational efficiency. Mapping input data, such as permeability and porosity fields, to reservoir production data using traditional numerical simulators is both computationally expensive and time-consuming.

In this equation, H, W, and D denote the three-dimensional spatial grid resolutions in the spatial domain. Traditional numerical simulation approaches, when applied to such three-dimensional grid structures, commonly face challenges related to computational inefficiency due to inherent nonlinearities and spatiotemporal constraints. To overcome these limitations, this study proposes a multimodal fusion Transformer neural network model that significantly simplifies this procedure. The proposed model provides an efficient approximation method to predict geothermal production data, thereby considerably reducing computational costs. In this section, we detail the construction of the proposed neural network architecture.

The self-attention mechanism is the core component of the Transformer model, designed to capture global dependencies among elements within a sequence. By leveraging self-attention, the model can dynamically focus on relevant positions in the sequence when computing the representation of each element, thereby effectively modeling long-range dependencies. For a given input feature sequence

By leveraging multiple attention heads in parallel, the model can capture diverse relationships between different positions within a sequence. Each attention head independently performs self-attention in a distinct subspace, and the results are concatenated to obtain a more expressive feature representation.

Transformer model: Transformer model consists of an encoder and a decoder, each composed of multiple stacked identical layers. The encoder is constructed by stacking multiple identical encoder layers, where each layer consists of two sub-layers:

- ➀Multi-Head Self-Attention Sub-Layer: Computes self-attention, followed by residual connections and layer normalization.

- ➁Applies a two-layer fully connected network, followed by residual connections and layer normalization.

The decoder is similar to the encoder but includes an additional encoder-decoder attention sub-layer, allowing the decoder to reference the encoder’s output when generating predictions. To prevent the decoder from accessing future information while predicting the current position, masking is applied, setting the attention weights for future positions to negative infinity. The computation follows a similar procedure as the encoder’s multi-head self-attention, but with the masking applied before the SoftMax operation.

Since the Transformer does not rely on the recursive structure of sequential models, it can fully leverage GPU parallelization for more efficient computation. The self-attention mechanism enables the model to directly attend to any position within the sequence, making it well-suited for capturing long-range dependencies.

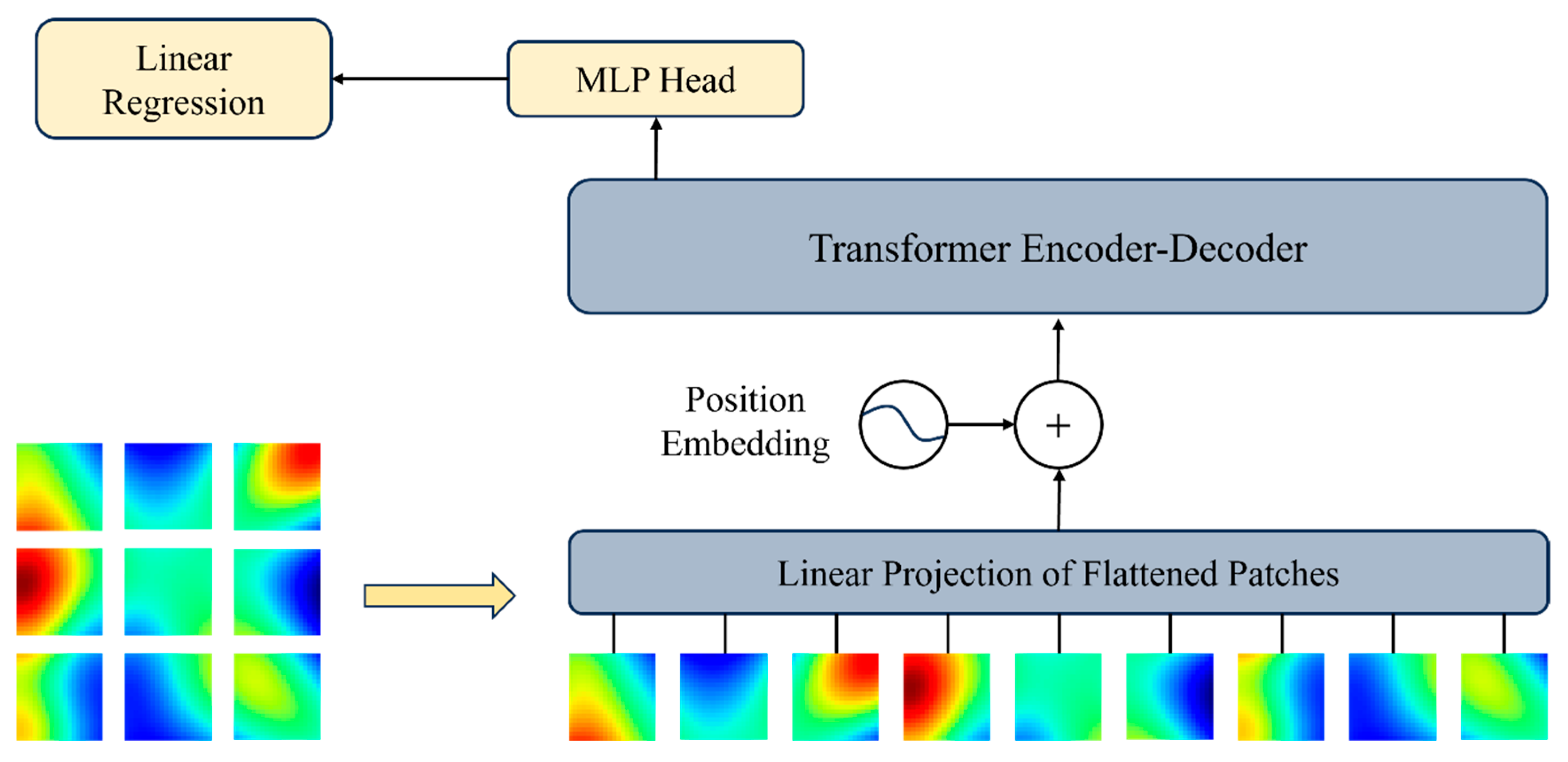

Vision Transformer model: Traditional computer vision models are primarily based on Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), which leverage convolutional operations to capture local image features. However, CNNs have limitations in modeling global dependencies and long-range relationships. The Vision Transformer (ViT) applies the Transformer model to the image domain, utilizing self-attention mechanisms to capture global relationships between different image regions, achieving performance comparable to or even surpassing that of CNNs.

The input image

By leveraging the self-attention mechanism, ViT can effectively capture long-range dependencies within an image, overcoming the receptive field limitations inherent in convolutional neural networks, As shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Schematic diagram of the vision neural network [31] copyright ©2025, AIP publishing.

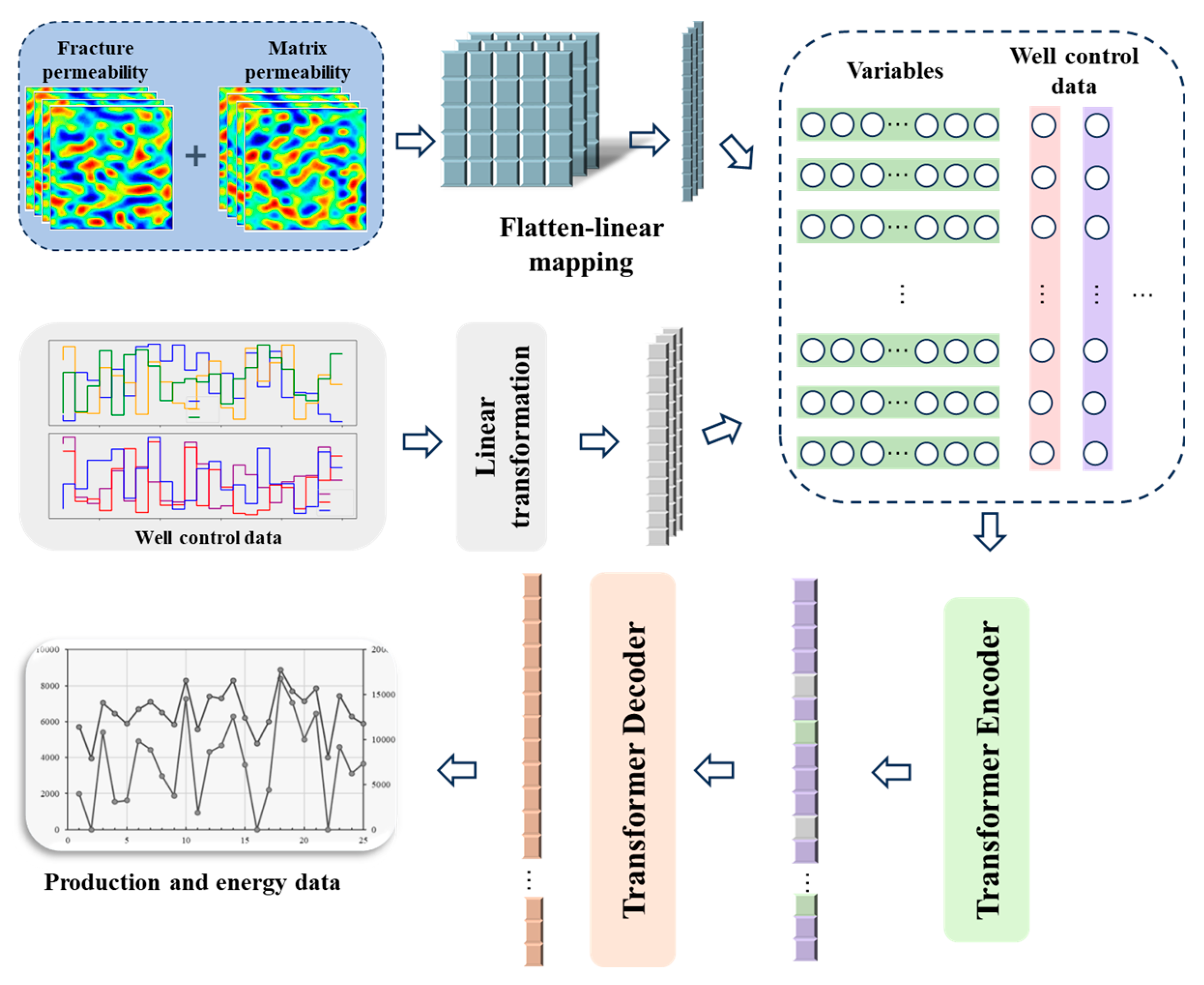

The multi-modal fusion Transformer model proposed in this study aims to integrate physical field data and geothermal development scheme information, fully utilizing the self-attention mechanism of the Transformer and the input processing approach of ViT to construct a model capable of efficiently predicting the target task.

This model consists of three key components. The details of each module are described below.

Input Processing: The input to the model consists of three primary data sources: physical field features, geothermal development scheme data, and graph-based spatial information. These inputs capture both spatial and temporal characteristics of the reservoir and its operational conditions. (1) The physical properties of the geothermal reservoir are represented by permeability distributions in both fracture networks and the rock matrix. (2) The development scheme data includes key operational parameters such as injection/production rates and temperature variations over time. (3) To unify these heterogeneous inputs, the model applies linear transformations: The geothermal scheme data is mapped to a 128-dimensional latent space using a fully connected layer. The permeability fields (fracture and matrix) are projected into a 256-dimensional feature space using another fully connected layer. The three feature sets (geothermal scheme, fracture, and matrix) are concatenated into a unified 640-dimensional feature representation, which is further processed using an additional linear transformation to 256 dimensions.

Before being fed into the Transformer, the processed input features undergo Layer Normalization and Dropout Regularization to improve generalization and prevent overfitting. Furthermore, a positional encoding module is incorporated to inject sequential dependencies into the Transformer, preserving the temporal relationships of geothermal production processes.

Multimodal Fusion Transformer-Based Architecture: The core of the model consists of multiple Transformer encoder and decoder layers, specifically designed to capture both short-term and long-term dependencies in the geothermal production process.

Transformer Encoder: The encoder module processes the input through four stacked layers. Each layer first applies a multi-head self-attention mechanism to extract spatial-temporal dependencies. The output is then passed through residual connections and layer normalization to maintain numerical stability. A feedforward network follows, transforming the feature space before another residual connection and layer normalization are applied. This sequence is repeated across all encoder layers, progressively refining the feature representations.

Transformer Decoder: The decoder module processes the encoded representations through multiple self-attention layers, establishing dependencies across different timesteps. The output is then passed through cross-attention layers, where it attends to encoder outputs for feature integration. Next, a feedforward network refines the transformed representations, followed by residual connections and layer normalization to stabilize processing. The final output is obtained through a linear projection layer, mapping the decoded features to the target prediction format.

Output Prediction: The final output of the model consists of key geothermal production parameters. The predicted parameters are structured as a sequence of feature vectors, each corresponding to a specific geothermal production indicator.

As shown in Fig. 3, the proposed methodology follows a streamlined workflow that integrates data processing, feature representation, model construction, and forecasting with optimization. Initially, reservoir and fracture parameters, injection–production schedules, and CO2–water mixture properties are derived from numerical simulations. These data are standardized through normalization, while the production time series are segmented into fixed-length sliding windows to enable sequential learning. Geological structures and injection–production connectivity are then encoded into graph adjacency matrices, which capture the spatial correlations among wells. At the same time, dynamic production sequences are mapped into a multimodal embedding space that combines both geological information and operational signals, ensuring a balanced representation of spatial and temporal features.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of the model.

Building upon these inputs, the proposed multimodal-fusion Transformer architecture processes temporal sequences with self-attention and extracts spatial connectivity patterns through graph convolution. The outputs of these two encoders are merged in a fusion layer, creating a joint latent space that fully exploits the complementary nature of different modalities. During training, physics-guided loss functions—enforcing mass and energy balance consistency—are incorporated to enhance the model’s interpretability and generalizability. Once trained, the surrogate model is capable of rapidly forecasting pressure, temperature, and production performance, achieving near real-time efficiency. Furthermore, the surrogate is coupled with an optimization module based on differential evolution, which searches for improved injection strategies while balancing economic benefits and sustainability metrics such as CO2 storage efficiency and temperature breakthrough control.

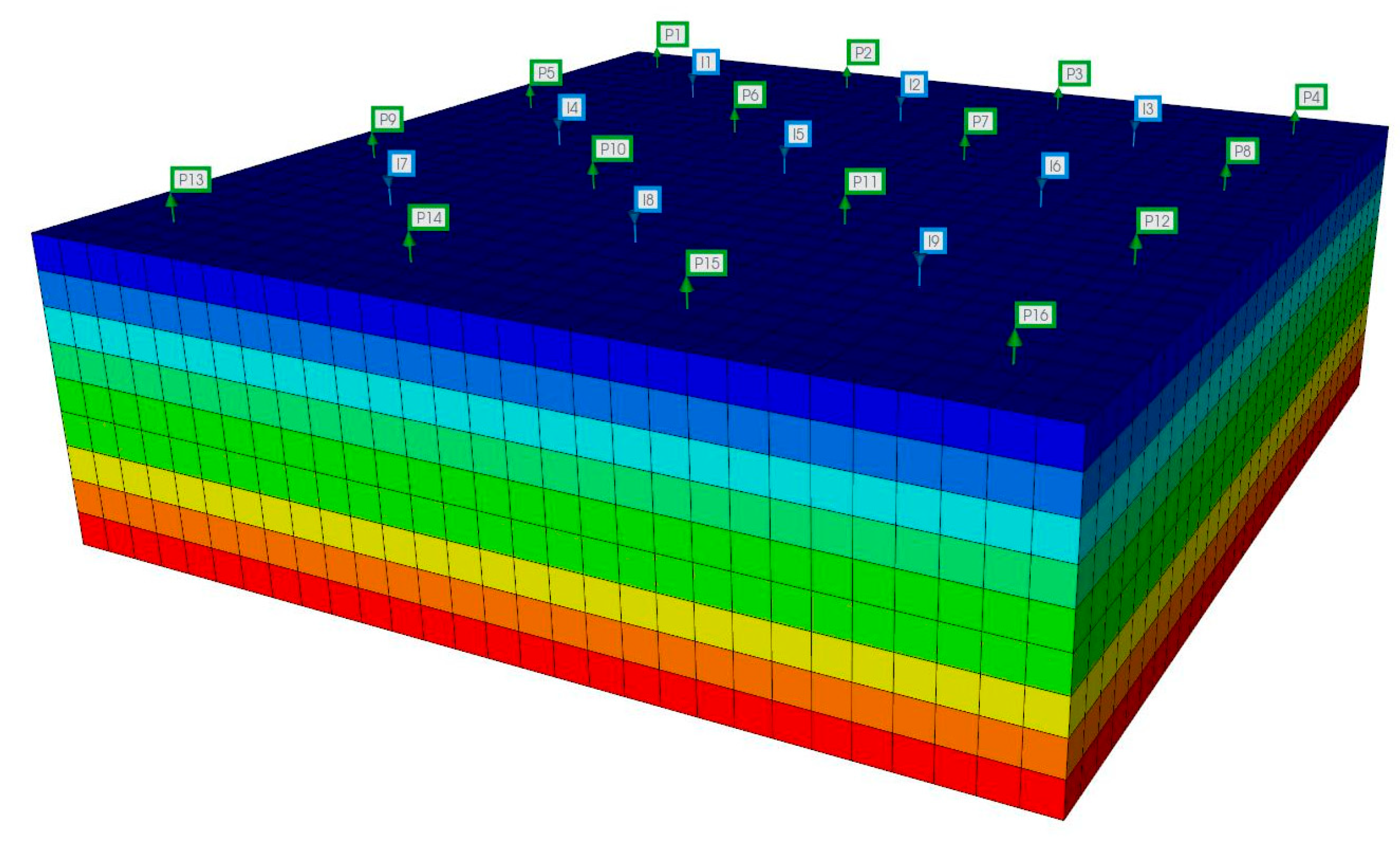

This study discusses an enhanced geothermal system developed for the New Mexico region. The area is endowed with abundant HDR resources, and its reservoirs are characterized by high temperatures and low permeability, using a CO2–water mixture as the working fluid. In this case, the CMG STARS™ simulator was employed to construct a dual-porosity, dual-permeability model that captures the coupling effects between the reservoir matrix and the engineered fractures. The main assumptions include always maintaining local thermal equilibrium within the reservoir and using the dual-porosity model to describe the heat conduction and mass exchange between the fractures and the matrix. The reservoir volume is 1770 × 1770 × 110 m3, and some parameters are listed in Table 1. Nine injection wells are used to introduce the working fluid into the reservoir, while sixteen production wells extract geothermal energy. The well locations are shown in Fig. 4.

Table 1: Model parameters.

| Parameters | Values |

|---|---|

| Initial formation temperature | 200°C |

| Initial formation pressure | 31 MPa |

| Matrix porosity | 0.2 |

| Fracture porosity | 0.25 |

| Fracture spacing | 10 m |

| Injection temperature | 15.56°C |

| Initial water saturation | 0.5 |

| Rock thermal conductivity | 1.73 W/(m·°C) |

| Rock specific heat | 0.239 J/(kg·°C) |

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of the model.

In this case study, sample sets were generated by varying the matrix and fracture permeabilities, the injection well fluid ratios, the injection rate, and the production well bottomhole pressure (BHP). The permeability field was generated using Gaussian interpolation, with matrix permeability ranging from 10 to 30 mD and fracture permeability ranging from 80 to 200 mD. The injection flow rate for the injection wells is between 200 and 400 m3/day, with the CO2 and water proportions ranging from 0 to 1, summing to 1. The production well BHP is set between 10 and 20 MPa; however, for computational stability, each production well’s BHP remains constant over time. The CMG STARS™ simulator was used to solve the geothermal reservoir model, discretizing the reservoir into a 29 × 29 × 9 grid. The simulation time step is set to 1 year, with a total simulation duration of 25 years, during which the well controls are adjusted annually, resulting in 25 control steps over the production period. In this study, 1000 sets of permeability fields and well control sequences were randomly generated, and the simulator was used to compute the geothermal energy extracted from HDR, the volume of dissolved CO2, and the water production rates at each well. These results constitute the training dataset for the deep learning surrogate model.

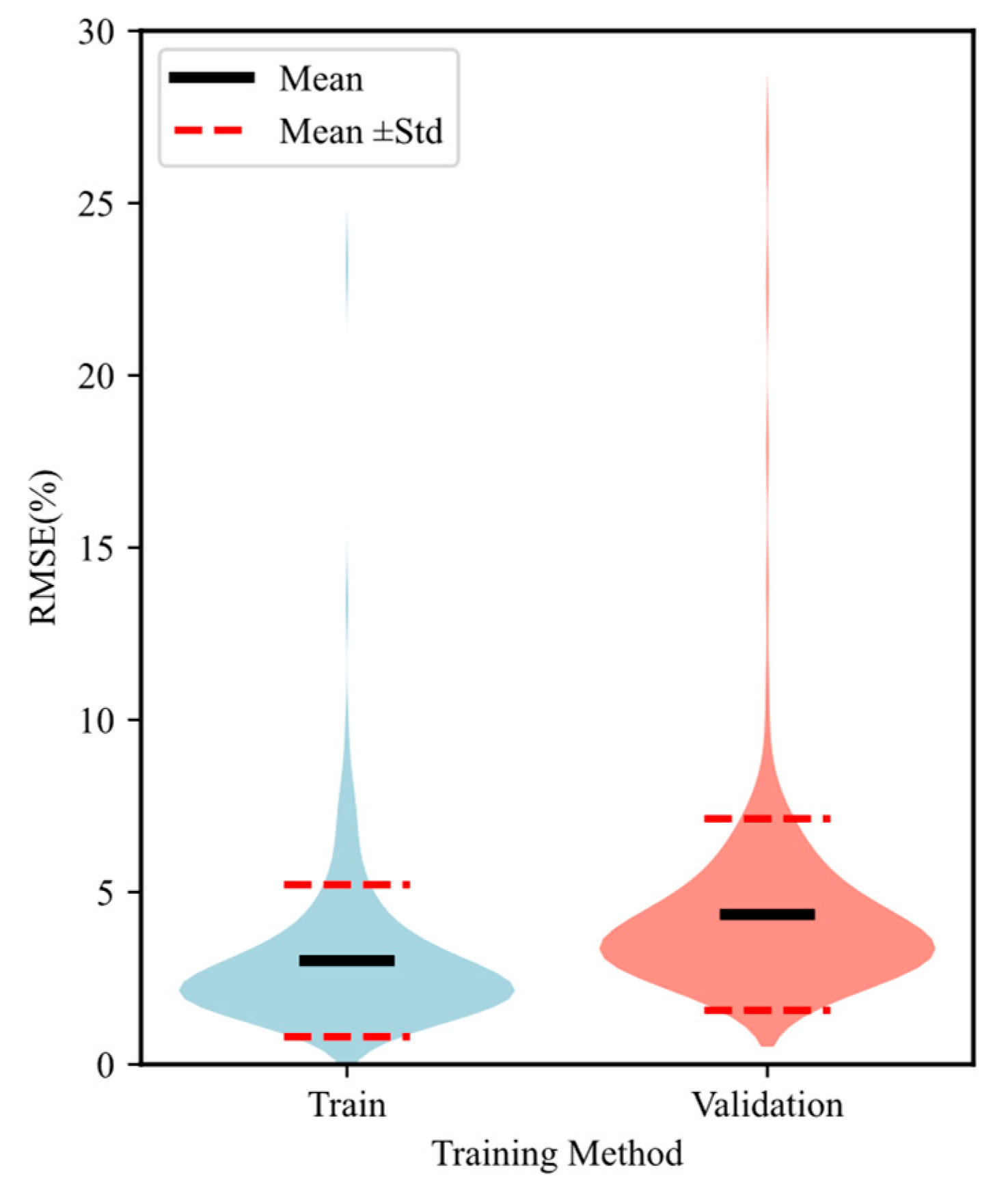

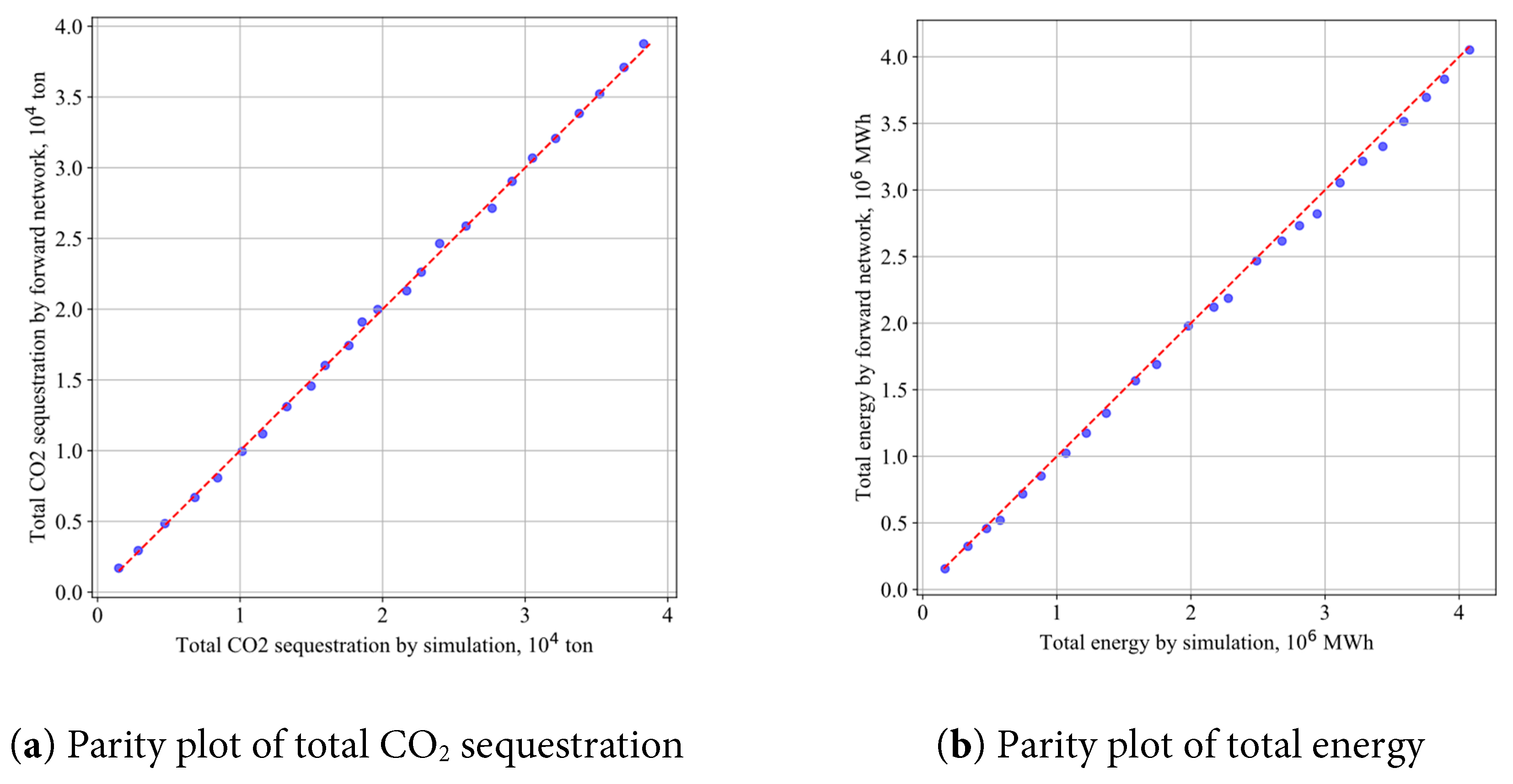

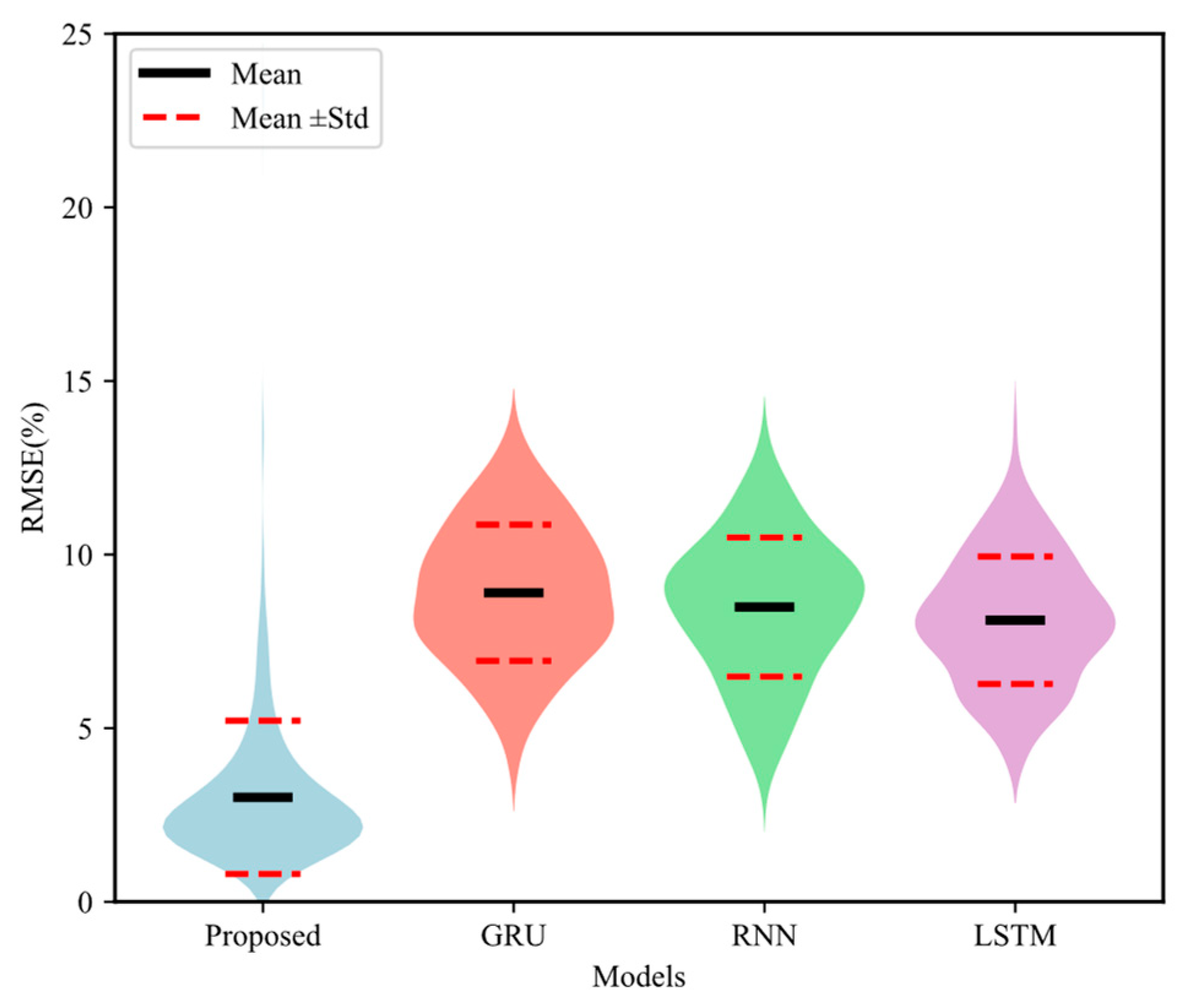

The deep learning surrogate model was trained for 200 epochs with a learning rate of 0.0001, taking approximately 530 s on an NVIDIA TITAN RTX. Table 2 presents the parameter settings for the deep learning surrogate model. The variation of root mean square error (RMSE) with epochs is shown in Fig. 5. The training set exhibits an average RMSE of 3%, with standard deviations ranging from 1.0% to 5.0%. Meanwhile, the testing set shows an average RMSE of 4.35%, with standard deviations between 1.57% and 7.13%. These results indicate that the model fits the training data well. Fig. 6 presents the parity plot of the parameters predicted by the forward surrogate model against the reference simulation results. The data points are closely distributed along the diagonal line, indicating that the surrogate model provides highly accurate predictions. This strong agreement confirms the reliability of the proposed surrogate in replacing time-consuming numerical simulations for subsequent optimization and analysis.

Table 2: Key parameters of the multimodal fusion transformer surrogate model.

| Component | Parameters | Details |

|---|---|---|

| Input Processing | Fracture Permeability | 29 ∗ 29 ∗ 9 |

| Matrix Permeability | 29 ∗ 29 ∗ 9 | |

| Development Scheme | 25 ∗ 43 | |

| Feature Projection | Development Scheme | 128D |

| Fracture & Matrix Grid | 256D | |

| Concatenated Feature | 640D | |

| Fully Connected Layer | 256D | |

| Transformer Encoder | Number of Layers | 6 |

| Embedding Dimension | 256D | |

| Attention Heads | 8 | |

| Dropout | 0.1 | |

| Transformer Decoder | Number of Layers | 6 |

| Embedding Dimension | 64D | |

| Attention Heads | 8 | |

| Dropout | 0.1 | |

| Output Prediction | Output Dimension | 25 ∗ 18 |

Figure 5: Distribution of training loss for the surrogate model.

Figure 6: Parity plot of parameters predicted by forward surrogate model, (a) total CO2 sequestration, (b) total energy, (c) WWPR for well P1, (d) WWPR for well P2.

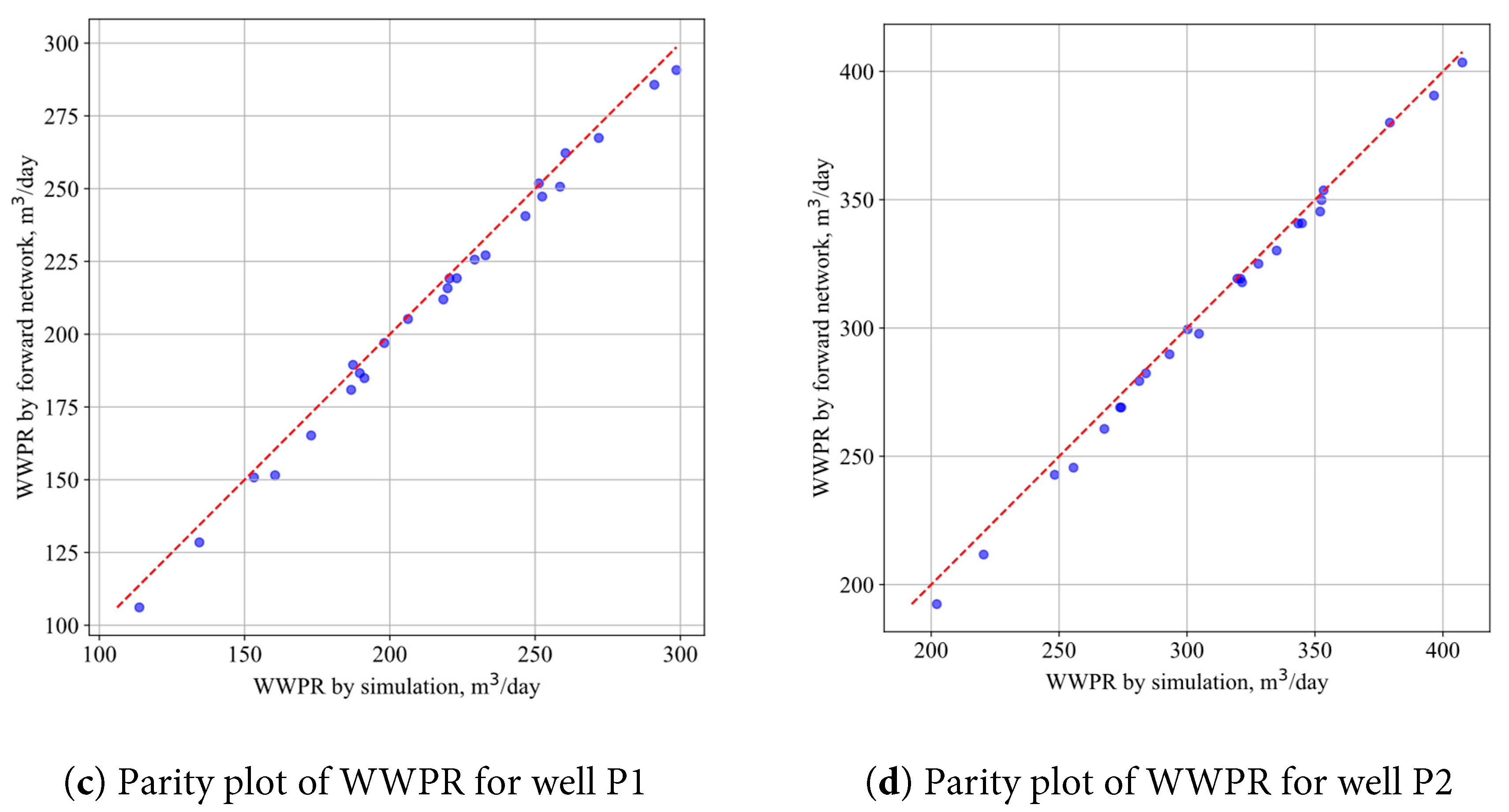

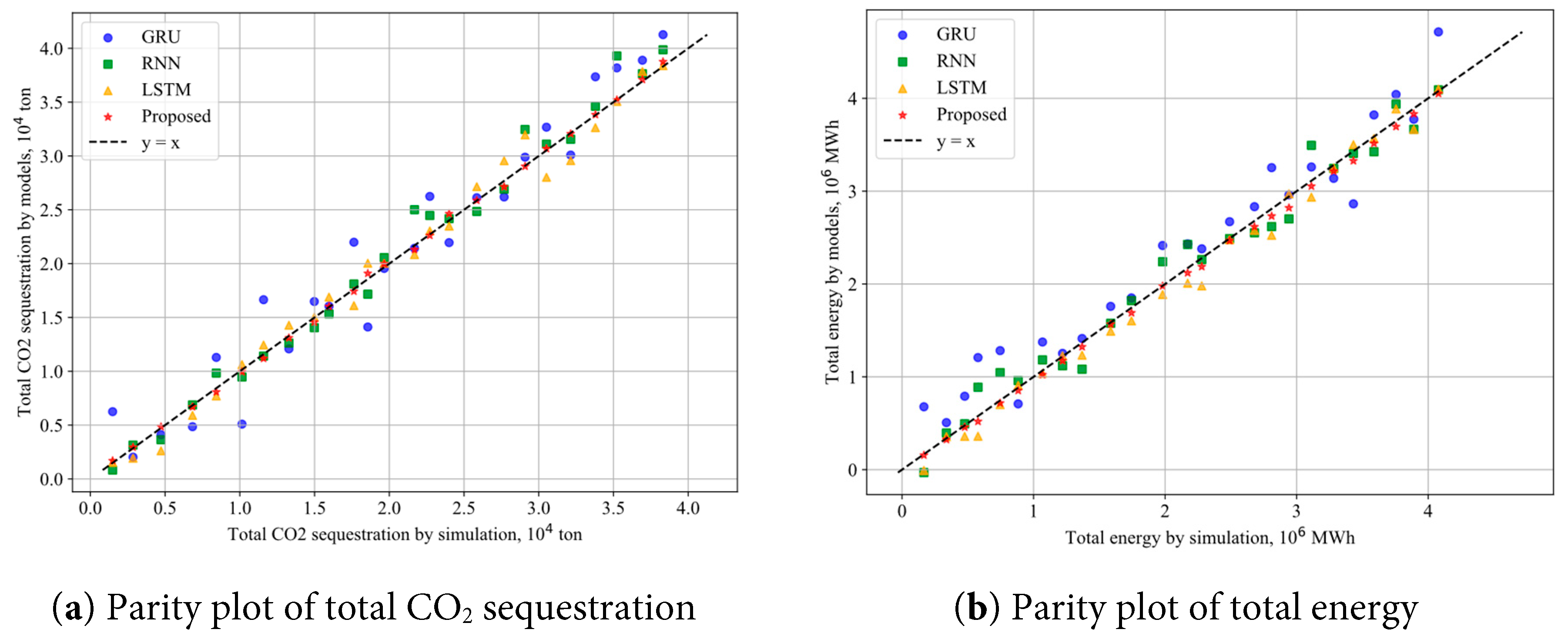

Fig. 7 compares the RMSE distributions of four methods on this dataset, where GRU, RNN, and LSTM are typical neural networks used for time series forecasting. In contrast, the average RMSE values for the GRU, RNN, and LSTM models are approximately 8.9%, 8.4%, and 8.1%, respectively, with a wider error distribution range. Fig. 8 presents the comparison between the predicted and actual values for CO2 sequestration and geothermal energy production across different models. It is evident from the figure that, compared with GRU, RNN, and LSTM, the “Proposed” model exhibits data points that are more tightly clustered around the 45° reference line in both plots, indicating higher prediction accuracy and lower dispersion. In contrast, the scatter distributions of the other models are relatively farther from the reference line, suggesting the presence of systematic biases or random errors that result in larger discrepancies between the predictions and the true values. These results demonstrate that the model proposed in this study offers significant advantages in both prediction accuracy and stability.

Figure 7: Distribution of training errors for different models.

Figure 8: Parity plot of parameters predicted by different models, (a) total CO2 sequestration, (b) total energy.

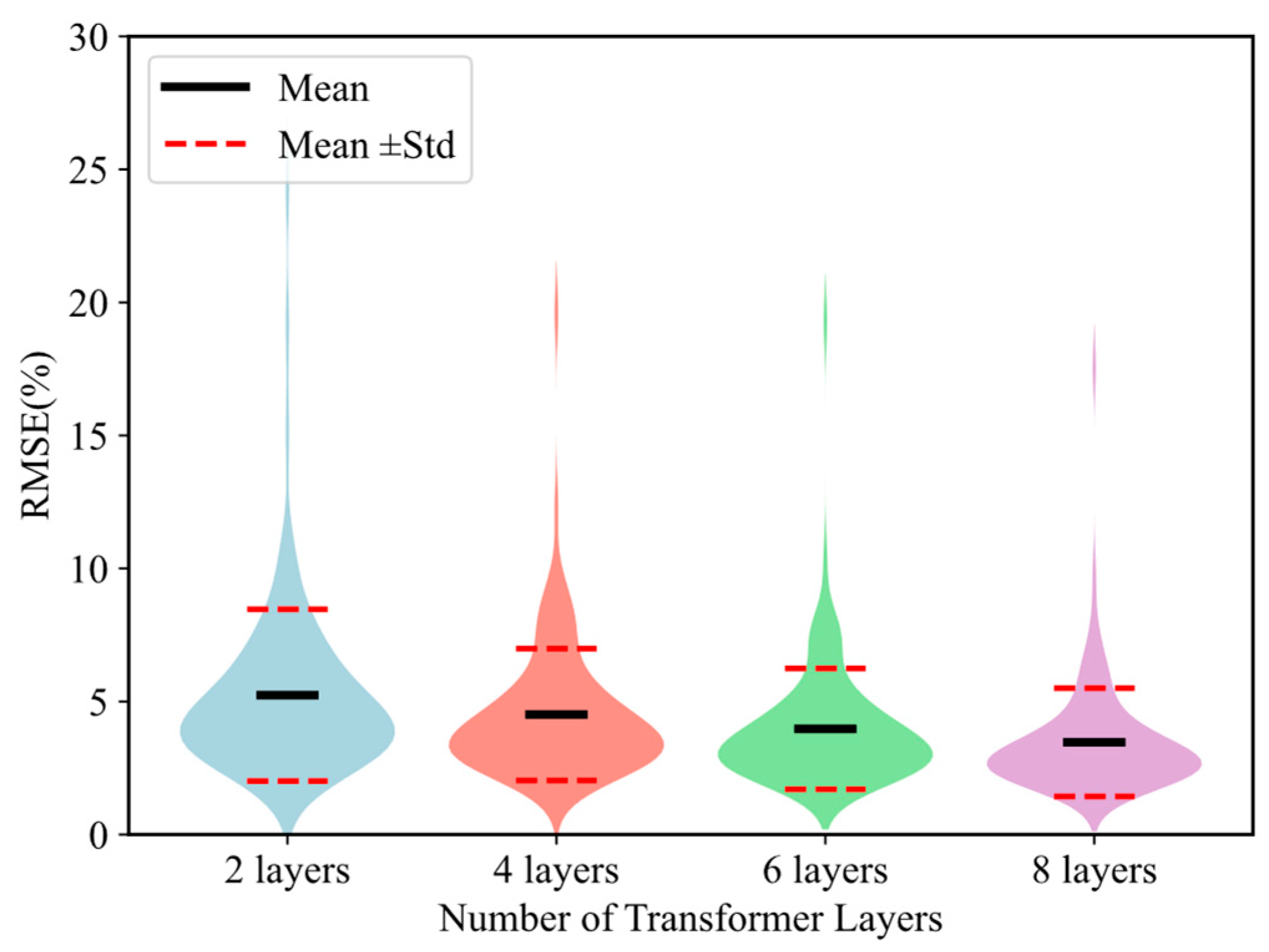

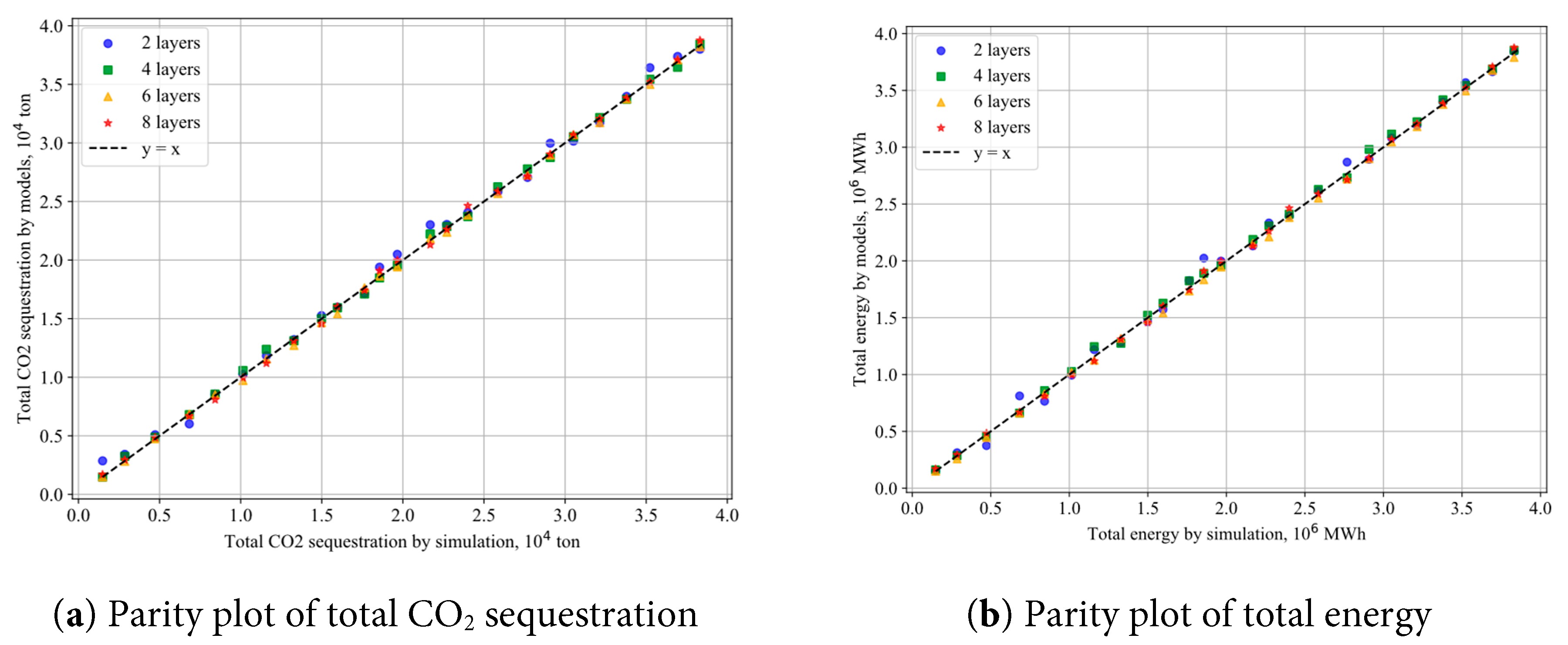

By adjusting the number of layers in both the encoder and decoder of the Transformer model, we explored its impact on model performance. Four different configurations were employed (i.e., 2, 4, 6, and 8 layers for both the encoder and decoder). As shown in Fig. 9, the Transformer models with different depths exhibit varying RMSE distributions in the prediction task. Specifically, the 2-layer model has an average RMSE of approximately 5.2% with a standard deviation of about 3.2%; the 4-layer model sees a reduction to around 4.5% average RMSE and a standard deviation of approximately 2.4%; the 6-layer model further decreases the average RMSE to roughly 3.9% with a standard deviation of about 2.2%; however, when the number of layers increases to 8, the average RMSE slightly rebounds to approximately 3.4% with a standard deviation of around 2.0%. Fig. 10 illustrates that for models with different depths, the data points for both the total CO2 sequestration (left panel) and total energy production (right panel) are distributed near the ideal 45° reference line, indicating an overall high prediction accuracy. In summary, these figures demonstrate that adjusting the number of layers affects the prediction accuracy and stability. An appropriate network depth enhances the consistency of predictions for CO2 sequestration and energy output. This trend suggests that moderately increasing the network depth can effectively improve the model’s feature extraction capabilities and reduce prediction errors. However, when the network becomes too deep, training becomes more challenging and the risk of overfitting increases, which may lead to a decline in prediction accuracy. Therefore, in practical applications, it is essential to balance network depth and model complexity based on the scale of the task, data volume, and available computational resources to achieve optimal predictive performance.

Figure 9: Model performance for different layer configurations.

Figure 10: Parity plot of parameters predicted by different models, (a) total CO2 sequestration, (b) total energy.

3.3 Generalization Performance Validation

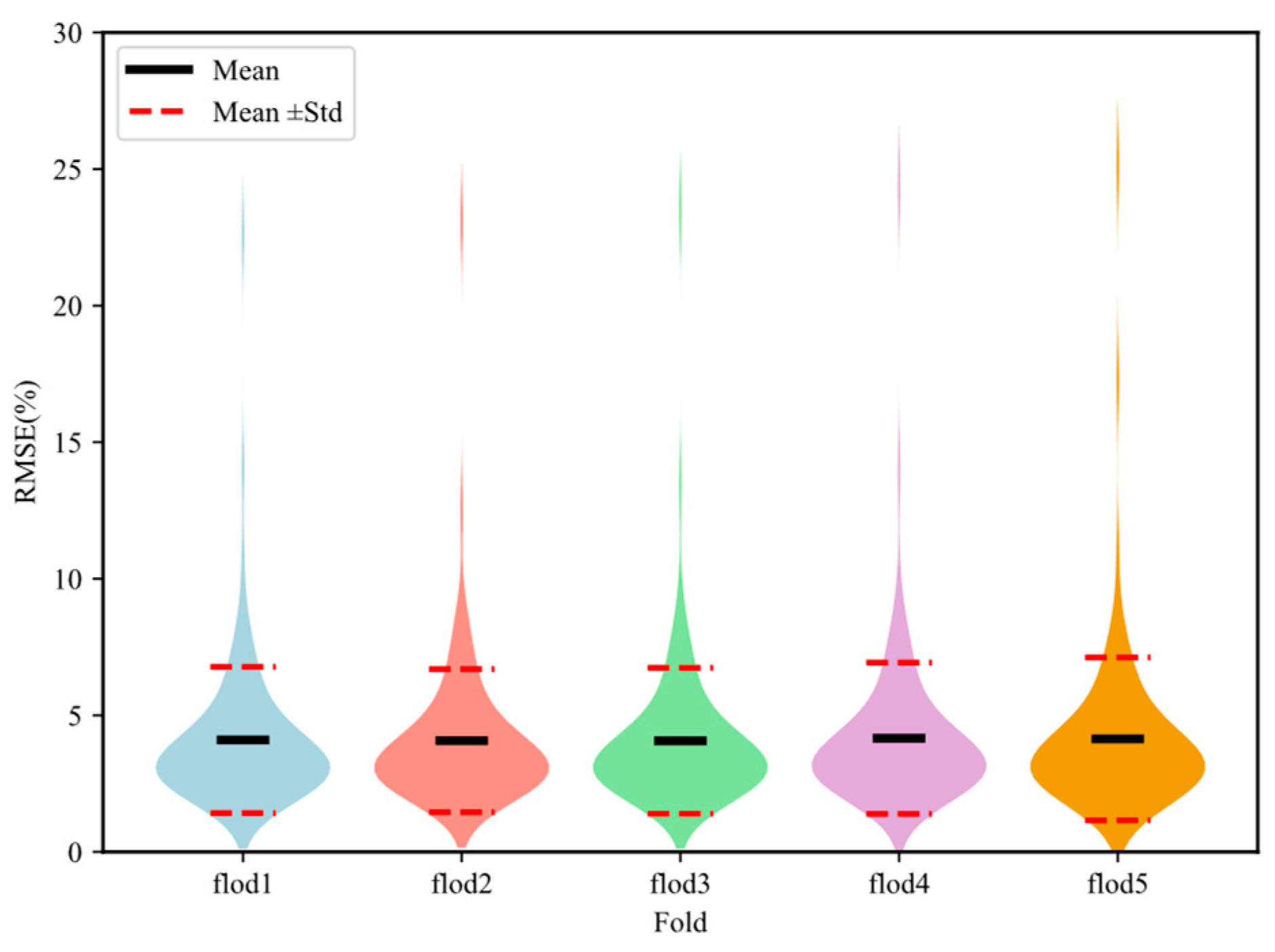

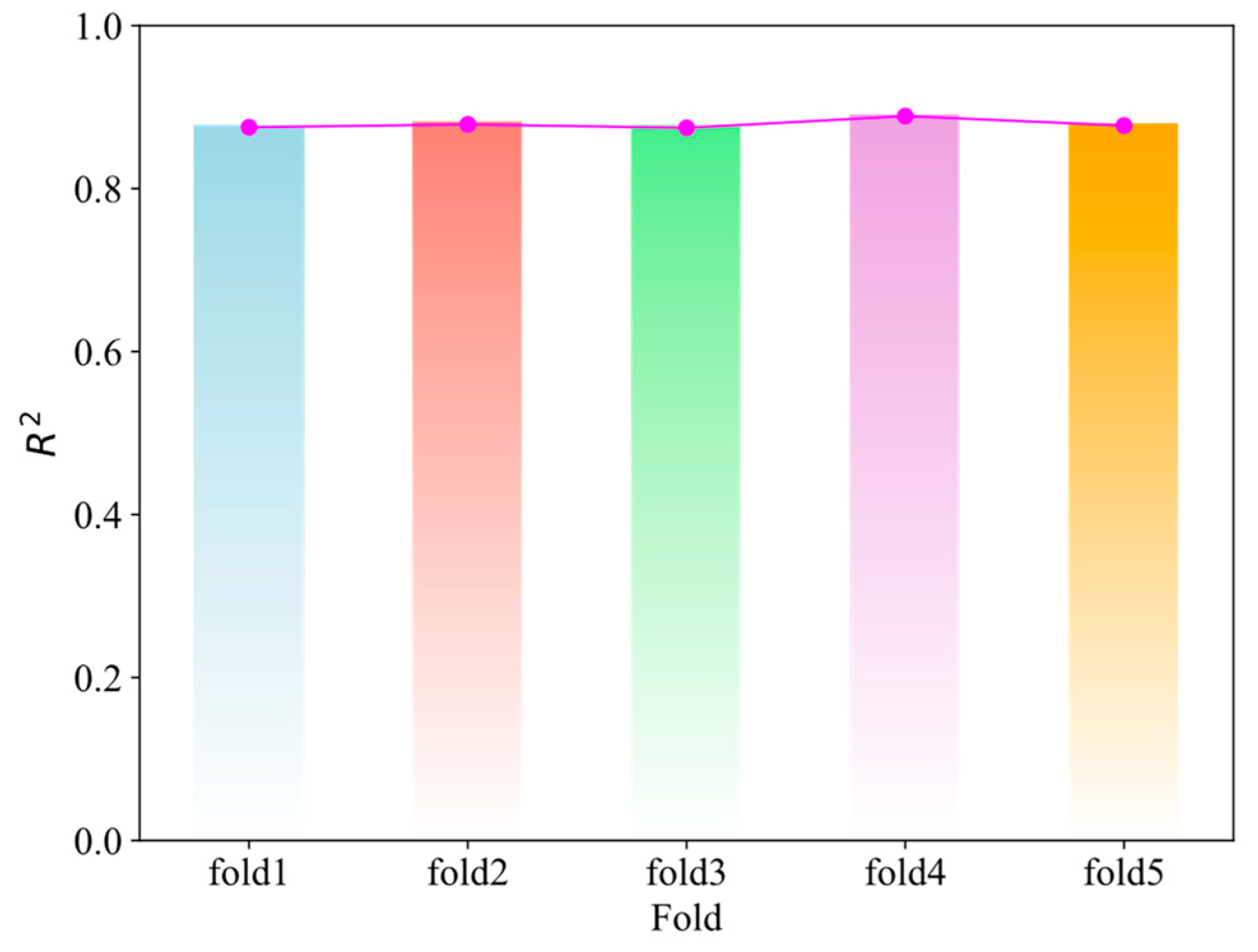

We employed 5-fold cross-validation to assess the generalization performance of the proposed model. Specifically, the entire dataset was randomly partitioned into five non-overlapping subsets (200 data samples per subset). In each fold, one subset was designated as the validation set, while the remaining subsets formed the training set. For each fold, the model was independently initialized and trained for 100 epochs. As shown in Fig. 11, the RMSE distributions across the different folds (fold1–fold5) are generally similar, with both the mean and standard deviation showing no significant differences. This indicates that the model achieves relatively consistent prediction accuracy across the folds, with a concentrated error distribution and no evident outliers. Furthermore, the R2 results (Fig. 12) reveal that the goodness-of-fit in each fold is consistently high with minimal variation. This suggests that under different data partitioning conditions, the model maintains stable explanatory power for the target variables and achieves robust fitting performance. In summary, the model’s performance during the 5-fold cross-validation is both stable and reliable, demonstrating strong generalization ability across different data splits.

Figure 11: Distribution of cross-validation training errors.

Figure 12: Average R2 on the validation set from cross-validation.

In this study, we developed an economic evaluation model based on net present value (NPV) to comprehensively assess the benefits and costs of a water + CO2 injection geothermal system over its entire lifetime. The primary benefits of the system are derived from energy production and CO2 sequestration incentives, while the costs include initial capital investments and annual operating expenses. According to Reference [21], the NPV is calculated using the following formula:

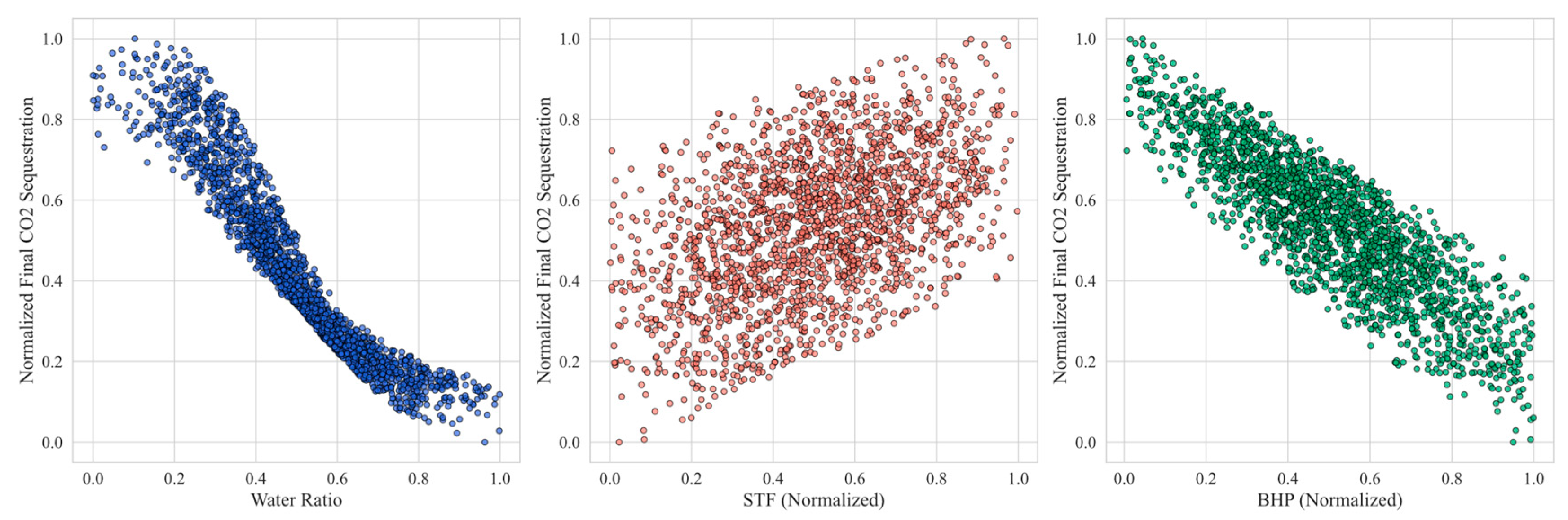

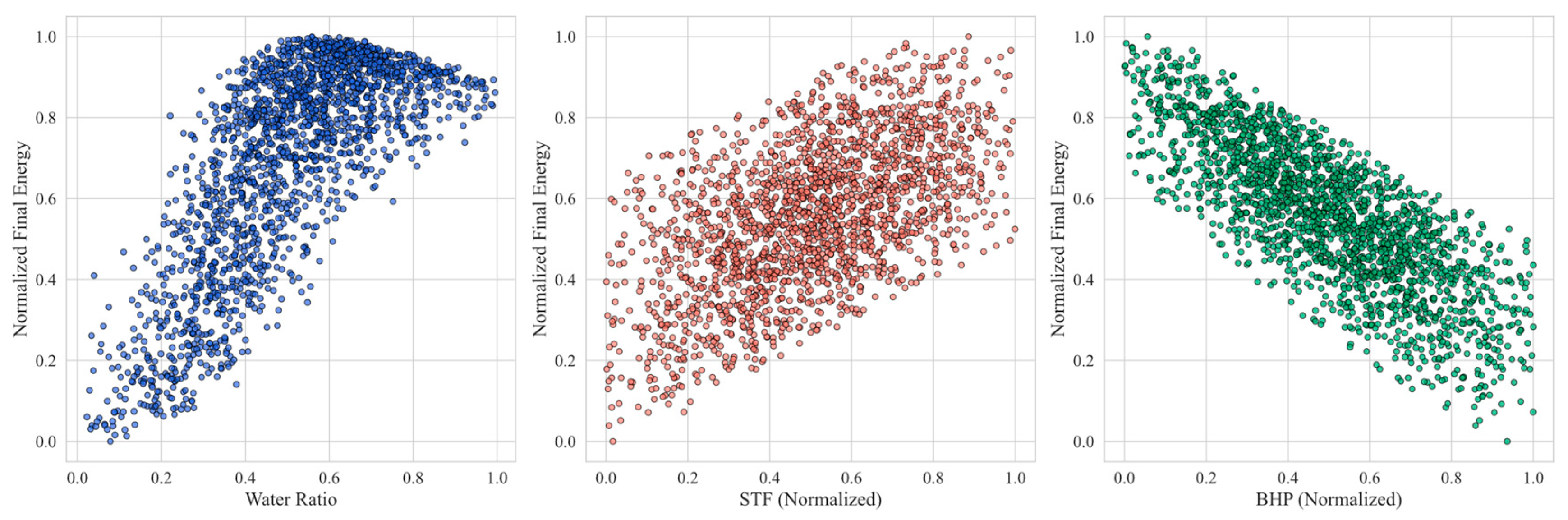

Fig. 13 and Fig. 14 compare the impact of water ratio, STF (surface total fluid rate) constraint, and producer BHP on system performance. Increasing STF raises the overall injection capacity under co-injection, whereas BHP primarily governs drawdown and production stability. From Fig. 13 (sensitivity analysis on CO2 sequestration), it can be seen that as the water injection ratio increases, the final sequestered CO2 amount exhibits a clear downward trend, indicating that a higher water phase proportion inhibits effective CO2 injection or dissolution. At the same time, an increase in the injection rate (STF) has a positive effect on CO2 sequestration, meaning that higher injection intensities can achieve greater sequestration; conversely, production well bottomhole pressure (BHP) is generally negatively correlated with CO2 sequestration, suggesting that excessively high production pressures may weaken the CO2 driving or retention effect, resulting in decreased sequestration. In Fig. 14 (sensitivity analysis on energy production), the water ratio is also negatively correlated with the final energy output, which may be due to losses in thermal energy or driving force caused by a high water ratio, thereby reducing overall energy production. In contrast, the injection rate (STF) promotes energy output within a certain range, indicating that higher injection intensities help enhance thermal energy or fluid drive efficiency. For production well BHP, a similar negative correlation with energy output is observed, implying that if the production well pressure is too high, fluid flow efficiency and energy recovery may be limited, thus affecting the system’s energy output.

Figure 13: Sensitivity analysis: CO2 sequestration.

Figure 14: Sensitivity analysis: effect on energy.

In the model, the ratios of CO2 and water in the injection wells, the injection rate, and the production well bottomhole pressure are selected as the key control parameters, as these three parameters directly affect the system’s revenue and cost structure. Table 3 provides some of the relevant economic parameters. To maximize NPV, this study employs a differential evolution algorithm to solve the model, finding the parameter combination that yields the optimal NPV through a reasonable adjustment of the CO2 ratio and injection rate. The trained deep learning surrogate model can now be used for well control optimization in geothermal reservoir production, thereby maximizing economic benefits.

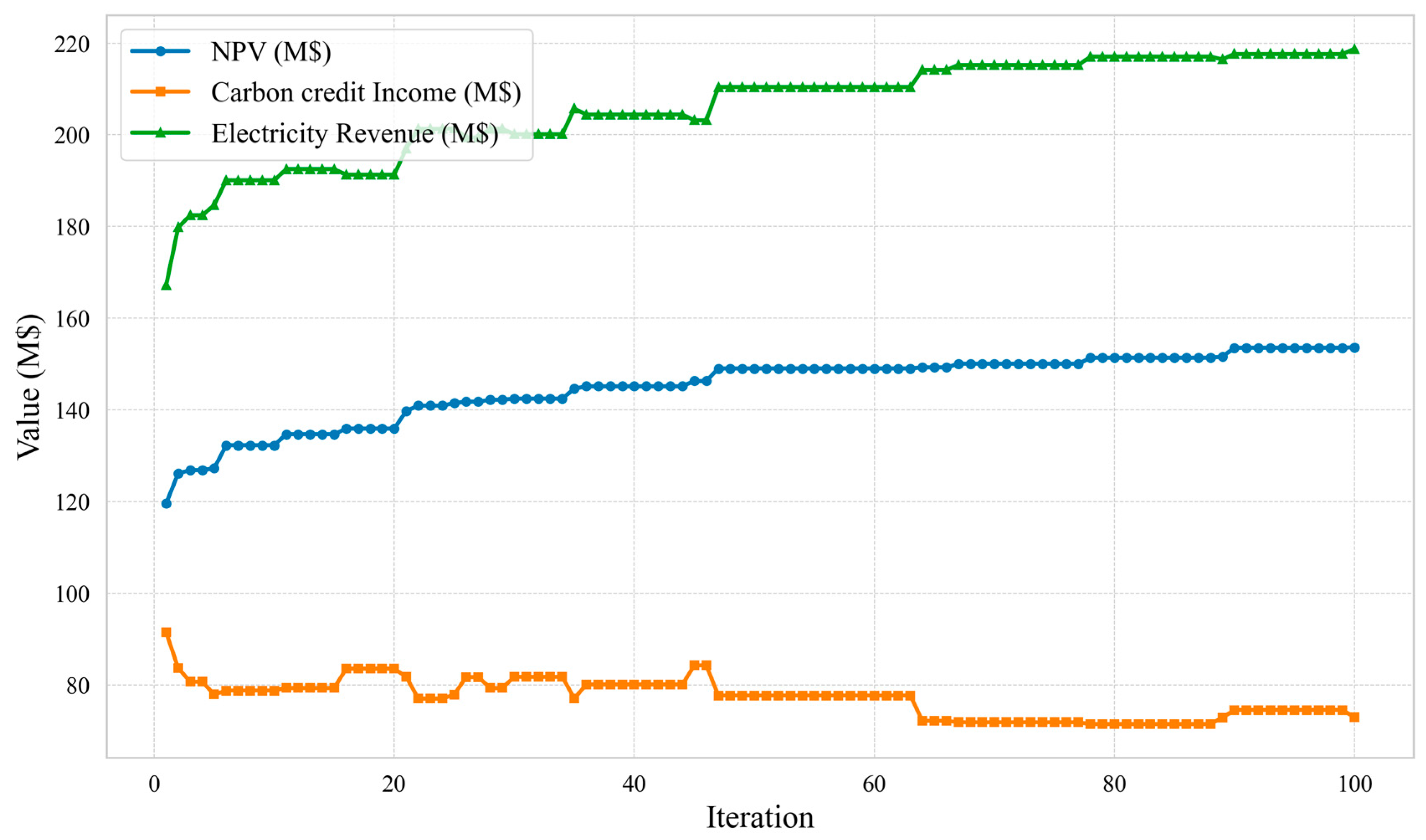

As shown in Fig. 15, as the number of iterations increases, the NPV (blue curve) shows a steady upward trend, eventually stabilizing in the later iterations. This indicates that the optimization algorithm continuously improves the net present value and gradually converges while seeking the optimal control strategy. In contrast, the Carbon Credit Income (orange curve) exhibits significant fluctuations during the iterations, which to some extent reflects the trade-offs in CO2 sequestration revenue under different injection/production strategies; whereas the Electricity Revenue (green curve) steadily increases from an initially lower level, eventually reaching the highest revenue value. This indicates that by adjusting parameters such as the water-CO2 injection ratio and production well pressure during the optimization process, energy recovery can be significantly enhanced. Overall, energy revenue dominates in the later stages of the optimization, while carbon revenue varies within a certain range with strategy adjustments. Together, these factors lead to a continuous improvement in the system’s overall economic indicator (NPV), which eventually converges to a relatively optimal level.

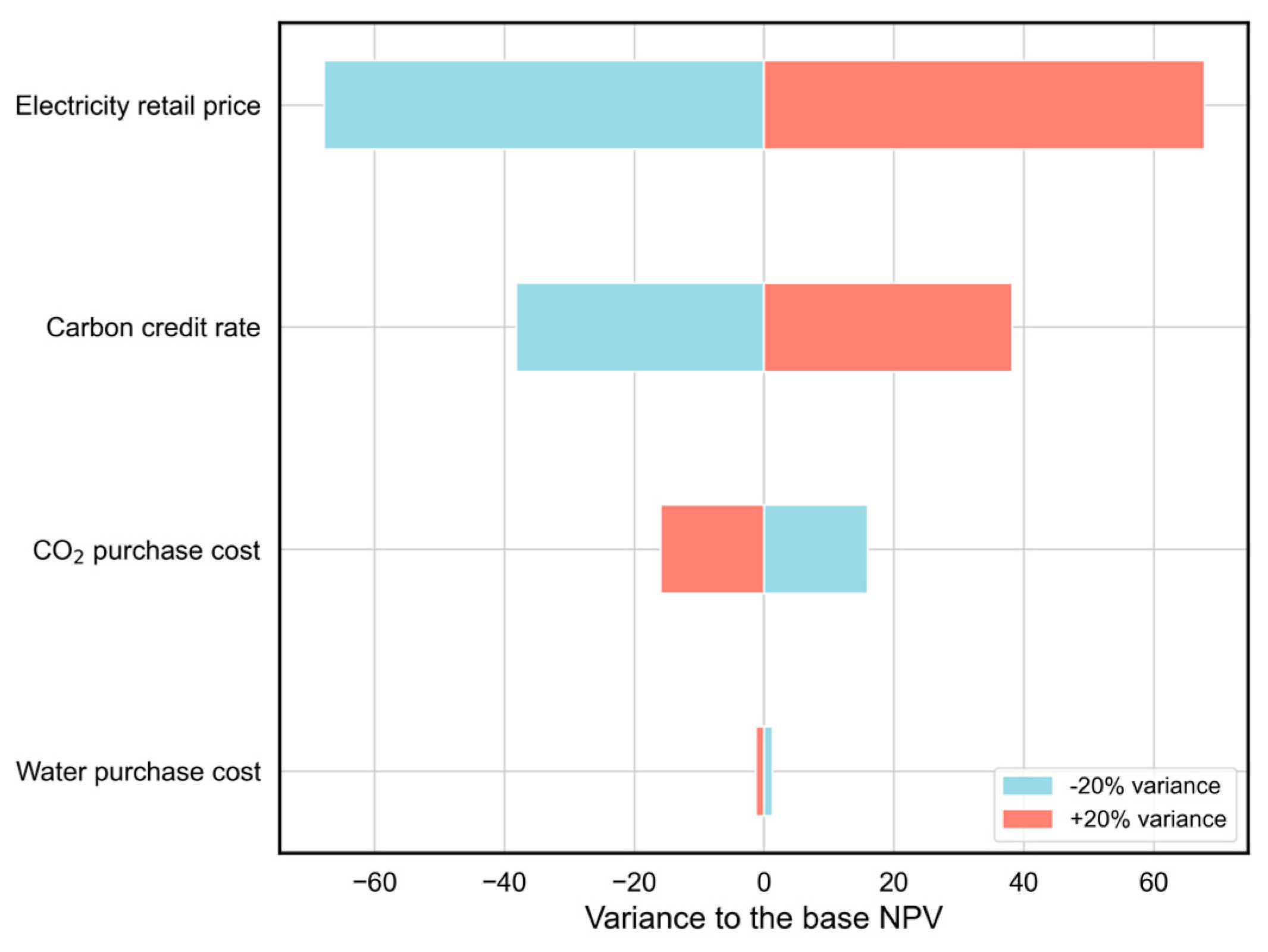

This paper also conducts a sensitivity analysis on the impact of fluctuations in several key economic parameters on the net present value. As shown in Fig. 16, fluctuations in electricity prices have the most significant impact on the final NPV. An increase in electricity prices substantially boosts electricity revenue, thereby significantly raising the NPV, while a decrease in electricity prices weakens revenue and lowers overall returns. Similarly, changes in carbon credit prices directly affect carbon revenue: if carbon credit prices increase, the project’s net present value is markedly enhanced, and vice versa. Although CO2 procurement costs can also lead to some revenue variations, their impact on NPV is smaller compared to electricity prices and carbon credit prices, mainly because CO2 procurement costs account for only a limited portion of the project’s revenue structure. Lastly, water procurement costs have the weakest effect on NPV, indicating that even if water costs fluctuate, they are unlikely to substantially impact the project’s overall economic viability.

Figure 15: NPV iteration plot.

Figure 16: Tornado diagram.

Table 3: Economic parameters.

| Parameter | Base Value | Lower Value | Upper Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electricity market price | 0.09 | 0.06 | 0.21 |

| CO2 purchase cost ($/ton) | 30 | 21 | 70 |

| Water purchase cost ($/ton) | 0.61 | 0.43 | 0.84 |

| Carbon credit rate ($/ton) | 60 | 40 | 75 |

| Tax rate (%) | 15 | N.A. | N.A. |

| 30 | N.A. | N.A. |

This study proposed a multimodal-fusion Transformer framework for simulating multiphase flow and heat transfer in CO2–water enhanced geothermal systems (EGS). The surrogate model integrates geological heterogeneity, operational schedules, and thermal–hydraulic dynamics into a unified architecture and demonstrates strong predictive capability. Based on the results, the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)Accuracy and efficiency: The proposed Transformer surrogate achieved RMSE of 3–5%, MAE < 4%, and R2 > 0.95 across production rates, pressure, and temperature predictions. Compared with recurrent neural networks (GRU, RNN, LSTM) and a physics-informed reduced-order model, the framework showed superior accuracy and computational efficiency.

- (2)Physics-guided loss: Incorporating mass- and energy-balance penalties improved predictive performance by approximately 10–12% relative to the purely data-driven baseline, confirming the value of embedding physical constraints.

- (3)Closed-loop optimization: Coupling the surrogate with a differential evolution (DE) optimizer enabled real-time optimization of injection strategies, resulting in a 15–20% increase in NPV compared with baseline strategies.

- (4)Sensitivity insights: Economic sensitivity analysis identified electricity price and carbon price as the dominant drivers of project profitability, surpassing variations in injection cost or thermal efficiency.

- (5)Limitations and future work: The present study assumes local thermal equilibrium, Darcy flow, and neglects geochemical reactions and geomechanical coupling. While these simplifications are acceptable under the studied conditions, they may limit generalization to other geothermal systems. Future work will extend the surrogate to non-LTE heat transfer, reactive processes, and poro-thermo-elastic effects, as well as broader geological priors.

Overall, the multimodal-fusion Transformer offers a practical and scalable surrogate modeling strategy, bridging deep learning and physical principles for enhanced geothermal system analysis, forecasting, and optimization.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Feng He and Rui Tan; methodology, Feng He, Rui Tan and Songlian Jiang; software, Chao Qian; validation, Chengzhong Bu and Benqiang Wang; writing—review and editing, Feng He, Rui Tan and Songlian Jiang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Gutiérrez-Negrín LCA . Evolution of worldwide geothermal power 2020–2023. Geotherm Energy. 2024; 12( 1): 14. doi:10.1186/s40517-024-00290-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Tester JW , Beckers KF , Hawkins AJ , Lukawski MZ . The evolving role of geothermal energy for decarbonizing the United States. Energy Environ Sci. 2021; 14( 12): 6211– 41. doi:10.1039/D1EE02309H. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Moses Jeremiah Barasa K . Geothermal electricity generation challenges opportunities and recommendations. Int J Adv Sci Res Eng. 2019; 5( 8): 53– 95. doi:10.31695/IJASRE.2019.33408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Soltani M , Kashkooli FM , Souri M , Rafiei B , Jabarifar M , Gharali K , et al. Environmental economic, and social impacts of geothermal energy systems. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2024; 140: 110750. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang Z , Ning Z , Guo W , Zhan J , Zhang Y . Study of fracture monitoring and heat extraction evaluation in geothermal reservoir modified by abandoned well pattern: numerical models and case studies. Energy. 2024; 296: 131144. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.131144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Xu Z , Zhao H , Fan L , Jia Q , Zhang T , Zhang X , et al. A literature review of using supercritical CO2 for geothermal energy extraction: potential methods, challenges, and perspectives. Renew Energy Focus. 2024; 51: 100637. doi:10.1016/j.ref.2024.100637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Xue Z , Ma H , Sun Z , Lu C , Chen Z . Technical analysis of a novel economically mixed CO2-water enhanced geothermal system. J Clean Prod 2006. 2024; 448: 141749. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li D , Li N , Jia J , Yu H , Fan Q , Wang L , et al. Development status and research recommendations for thermal extraction technology in deep hot dry rock reservoirs. Deep Undergr Sci Eng. 2024; 3( 3): 317– 25. doi:10.1002/dug2.12080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pruess K . Enhanced geothermal systems (EGS) using CO2 as working fluid—a novel approach for generating renewable energy with simultaneous sequestration of carbon. Geothermics. 2006; 35( 4): 351– 67. doi:10.1016/j.geothermics.2006.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Xie J , Wang J . Compatibility investigation and techno-economic performance optimization of whole geothermal power generation system. Appl Energy. 2022; 328: 120165. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Biagi J , Agarwal R , Zhang Z . Simulation and optimization of enhanced geothermal systems using CO2 as a working fluid. Energy. 2019; 86: 627– 37. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2015.04.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Othman F , Naufaliansyah MA , Hussain F . Effect of water salinity on permeability alteration during CO2 sequestration. Adv Water Resour. 2016; 127: 237– 51. doi:10.1016/j.advwatres.2019.03.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang Z , Ning Z , Guo W , Zhan J , Chen Z . Study on geothermal energy self-recycling extraction and ScCO2 storage in the horizontal well annuli with fracture network system. Energy Convers Manag. 2024; 310: 118482. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bujakowski W , Tomaszewska B , Miecznik M . The Podhale geothermal reservoir simulation for long-term sustainable production. Renew Energy. 2022; 99: 420– 30. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2016.07.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li S , Feng XT , Zhang D , Tang H . Coupled thermo-hydro-mechanical analysis of stimulation and production for fractured geothermal reservoirs. Appl Energy. 2019; 247: 40– 59. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2019.04.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Wang J , Zhao Z , Liu G , Xu H . A robust optimization approach of well placement for doublet in heterogeneous geothermal reservoirs using random forest technique and genetic algorithm. Energy. 2025; 254: 124427. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2022.124427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Nugroho AA , Ashat A . Pressure prediction in two-phase geothermal well flow using physics informed neural network (PINN). IOP Publ. 2025; 1456( 1): 012008. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/1456/1/012008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Gao M , Sun W , Xu J , Li J . Reduced-order modeling for subsurface flow simulation in fractured reservoirs. SPE J. 2025; 30( 1): 391– 408. doi:10.2118/223949-PA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li Y , Peng G , Du T , Jiang L , Kong XZ . Advancing fractured geothermal system modeling with artificial neural network and bidirectional gated recurrent unit. Appl Energy. 2024; 372: 123826. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yang R , Wang Y , Song G , Shi Y . Fracturing and thermal extraction optimization methods in enhanced geothermal systems. Adv Geo-Energy Res. 2023; 9( 2): 136– 40. doi:10.46690/ager.2023.08.07. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Xue Z , Zhang Y , Ma H , Lu Y , Zhang K , Wei Y , et al. A combined neural network forecasting approach for CO2-enhanced shale gas recovery. SPE J. 2024; 29( 08): 4459– 70. doi:10.2118/219774-PA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Ishitsuka K , Lin W . Physics-informed neural network for inverse modeling of natural-state geothermal systems. Appl Energy. 2023; 337: 120855. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2023.120855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yan B , Gudala M , Hoteit H , Sun S , Wang W , Jiang L . Physics-informed machine learning for noniterative optimization in geothermal energy recovery. Appl Energy. 2023; 365: 123179. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yan B , Gudala M , Sun S . Robust optimization of geothermal recovery based on a generalized thermal decline model and deep learning. Energy Convers Manag. 2015; 286: 117033. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2023.117033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Bassam A , del Castillo AÁ , García-Valladares O , Santoyo E . Determination of pressure drops in flowing geothermal wells by using artificial neural networks and wellbore simulation tools. Appl Therm Eng. 2024; 75: 1217– 28. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2014.05.048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Adhikari K , Mudunuru MK , Nakshatrala KB . Closed-loop geothermal systems: modeling and predictions. arXiv:2407.04716. 2024. [Google Scholar]

27. Takam PH , Wunderlich R . Model order reduction for the input–output behavior of a geothermal energy storage. J Eng Math. 2024; 148( 1): 12. doi:10.1007/s10665-024-10398-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Xiao C , Liu T , Zhang L , Li Z . Use of deep-learning-accelerated gradient approximation for reservoir geological parameter estimation. Processes. 2024; 12( 10): 2302. doi:10.3390/pr12102302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhu CY , Huang D , Lei WX , He ZY , Duan XY , Gong L . Prediction of output temperature and fracture permeability of EGS with dynamic injection rate based on deep learning method. Renew Energy. 2025; 239: 122102. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2024.122102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Wang N , Chang H , Kong XZ , Zhang D . Deep learning based closed-loop well control optimization of geothermal reservoir with uncertain permeability. Renew Energy. 2025; 211: 379– 94. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.04.088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Liu W , Guan Y , Yan X , He S , Jiang M , Gong J , et al. An efficient prediction and historical matching method for reservoir dynamics using advanced attention-based vision transformer. Phys Fluids. 2025; 37 (1): 016613. doi:10.1063/5.0246235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools