Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Fault-Induced Floor Water Inrush in Confined Aquifers under Mining Stress: Mechanisms and Prevention Technologies—A State-of-the-Art Review

1 International Joint Research Laboratory of Henan Province for Underground Space Development and Disaster Prevention, School of Civil Engineering, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo, 454000, China

2 Henan Mine Water Disaster Prevention and Control and Water Resources Utilization Engineering Technology Research Center, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo, 454000, China

3 Collaborative Innovation Center of Coal Work Safety and Clean High Efficiency Utilization, Jiaozuo, 454000, China

4 School of Energy Science and Engineering, Henan Polytechnic University, Jiaozuo, 454000, China

* Corresponding Author: Wenqiang Wang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Fluid Dynamics and Multiphysical Coupling in Rock and Porous Media: Advances in Experimental and Computational Modeling)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(10), 2419-2442. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.070624

Received 20 July 2025; Accepted 01 September 2025; Issue published 30 October 2025

Abstract

With the depletion of shallow mineral resources, mining operations are extending to greater depths and larger scales, increasing the risk of water inrush disasters, particularly from confined aquifers intersected by faults. This paper reviews the current state of research on fault-induced water inrushes in mining faces, examining the damage characteristics and permeability of fractured floor rock, the mechanical behavior of faults under mining stress, and the mechanisms driving water inrush. Advances in prevention technologies, risk assessment, and prediction methods are also summarized. Research shows that damage evolution in fractured floor rock, coupled with fluid-solid interactions, provides the primary pathways for water inrush. Stress-seepage coupling in porous media plays a decisive role in determining inrush potential. Mining-induced stress redistribution can activate faults, with parameters such as dip angle and internal friction angle controlling stress evolution and slip. Critical triggers include the hydraulic connectivity among faults, aquifers, and mining-induced fracture networks, followed by hydraulic erosion. A multi-pronged prevention framework has been developed, integrating precise fault detection, targeted grouting for water sealing, drainage to reduce water pressure, optimized waterproof coal pillar design, and dynamic risk assessment and prediction. However, gaps remain in understanding multi-physical field coupling under deep mining conditions, establishing quantitative criteria for fault activation-induced water inrush, and refining control technologies. Future work should focus on multi-scale numerical simulations, advanced active control measures, and intelligent, integrated prevention systems to clarify the mechanisms of fault-induced water inrush and enhance theoretical and technical support for mine safety.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Coal has long been the foundational energy source supporting national economic development and remains the primary energy source consumed [1,2]. It is indispensable for energy security and offers critical stability during structural transitions. Continued reliance on coal remains necessary for socioeconomic progress at the current developmental stage [3]. The depletion of shallow reserves larger-scale extraction in deeper strata, intensifying technical challenges for mine safety. Notably, water inrushes have emerged as critical hazards threatening operational safety amid complex hydrogeological conditions and high-intensity mining disturbances. Such incidents are second only to gas explosions in severity among major mining accidents. Statistics show that casualties and direct economic losses from water inrushes exceed those of most other mining disasters. More critically, their destructive potential and tendency to trigger secondary catastrophes prolong rescue efforts and production recovery periods far exceeding those of typical mining accidents [4].

Faults form during initial stratum sedimentation via tectonic movements. Significant structural events typically generate one or more major faults alongside numerous minor ones. These features disrupt rock continuity and integrity while containing abundant fracture fillings. Consequently, they exhibit virtually no tensile or shear strength alongside substantially reduced water-blocking capacity. Fault-induced water inrushes pose persistent threats to safe mining above confined aquifers given their concealed nature, complex mechanisms, and limited remediation windows.

Addressing the critical challenge of fault-induced water inrush from confined aquifers in mining floors, researchers have conducted extensive research particularly in rock damage mechanics, seepage-stress coupling theory, and engineering controls These studies provide crucial theoretical foundations for mitigating water inrush. Advancing current research, this review focuses on three core areas: (1) damage and seepage-stress coupling in fractured floor strata, (2) mechanisms of fault-induced water inrush, and (3) prevention technologies for fault-related water inrush in confined-aquifer mining. By systematically analyzing existing research, this work clarifies theoretical innovations and practical applications, establishes foundations for understanding catastrophic mechanisms of fault-induced floor water inrush, and develops integrated prevention systems incorporating detection, treatment, and evaluation. It further offers new perspectives for scientific and technological advancement progress in related disciplines.

2 Research Progress on Failure Characteristics of Floor Fractured Rock Mass and Porous Media

The occurrence of fault water inrush primarily stems from the hydrological conditions created by fractured rock masses and porous media. Fault activity establishes direct hydraulic connections between these systems. Fractured rock masses act as primary flow channels, while porous media function as major reservoirs and seepage fields, conveying water toward fault zones. Their high permeability makes fault zones become potential conduits. Mining activities, such as excavation, pressure relief, and stress redistribution, disturb this system, disrupting hydrogeological and geomechanical equilibria. Consequently, high-pressure groundwater rapidly converges through preferential pathways within fault zones and adjacent affected areas, causing water inrush. Therefore, a comprehensive understanding of fractured rock masses and porous media is essential for elucidating fault water inrush mechanisms and associated risks.

2.1 Current Research Status On Fractured Rock Mass via Damage and Fluid-Solid Coupling

Under engineering disturbances, damage develops in fractured rock masses within faults and their vicinity. This process interacts intensely with high-pressure groundwater through fluid-solid coupling, triggering fault water inrush disasters [5,6]. Damage evolution [7,8,9,10]—characterized by fracture network propagation and connectivity [11,12,13] that enhance water conductivity—forms the basis for water-conducting channels. Fluid-solid coupling [14]—where declining pore water pressure reduces effective stress, inducing shear failure and fracture deformation that promote permeability surges—triggers instantaneous channel connectivity or large-scale expansion. This ultimately causes high-pressure groundwater to breach and ejectdebris.

Prior to mining, the surrounding rock system exists in a state of stress equilibrium. Excavation disrupts this equilibrium, inducing significant stress redistribution within the rock mass. As the working face advances and retreats, the disturbance level in the rock mass initially rises then falls, causing damage in the floor strata. Damage in fractured rock masses typically involves the propagation of existing fractures or the formation of new ones, altering both mechanical properties [15] and permeability [13]. Under external stress, fractured rock masses experience cracking, deformation, and failure; increasing fractures gradually reduce overall stability. Preexisting discontinuities initiate damage, governing subsequent deformation behavior. Granite, a representative brittle rock, facilitates clear observation of damage evolution and fracture development, making it ideal for studying damage mechanisms in fractured rock masses. Under uniaxial loading, pre-fractured granite specimens exhibit significantly greater tensile and shear damage than intact specimens [16]. Damage evolution curves for granite can be determined through uniaxial compression tests with incremental cyclic loading, while in situ curves may be estimated using Goodman jacks [17]. Effective monitoring techniques are required to reveal damage evolution mechanisms in fractured rock, Shirole employed the Scaling Subtraction Method (primarily used in digital image processing to detect significant change regions between temporally distinct images) alongside two-dimensional digital image correlation (a non-contact optical technique measuring in-plane displacement and strain fields on loaded surfaces) to examine fracture influence on rock damage processes [16]. Multi-stage creep (constant load) and multi-stage relaxation (constant strain) experiments were conducted on granite specimens containing double flaws under uniaxial compression. Acoustic Emission (detecting transient elastic waves from materials undergoing internal structural changes under stress) and 2D-DIC monitored crack evolution, accumulated damage, and failure modes, revealing significant tensile crack development [18]. Understanding and predicting time-dependent rock deformation is critical for underground structure stability [19]. Introducing damage evolution laws into time-dependent effects, a novel microcrack damage model predicts stress-strain-time responses, capturing the anisotropy of microcrack-induced damage and its temporal evolution [20]. Loading granite specimens beyond the crack damage threshold under constant stress evaluates brittle creep damage. Results indicate creep deformation primarily stems from the extension of pre-damaged zones, consistent with subcritical crack growth models [21].

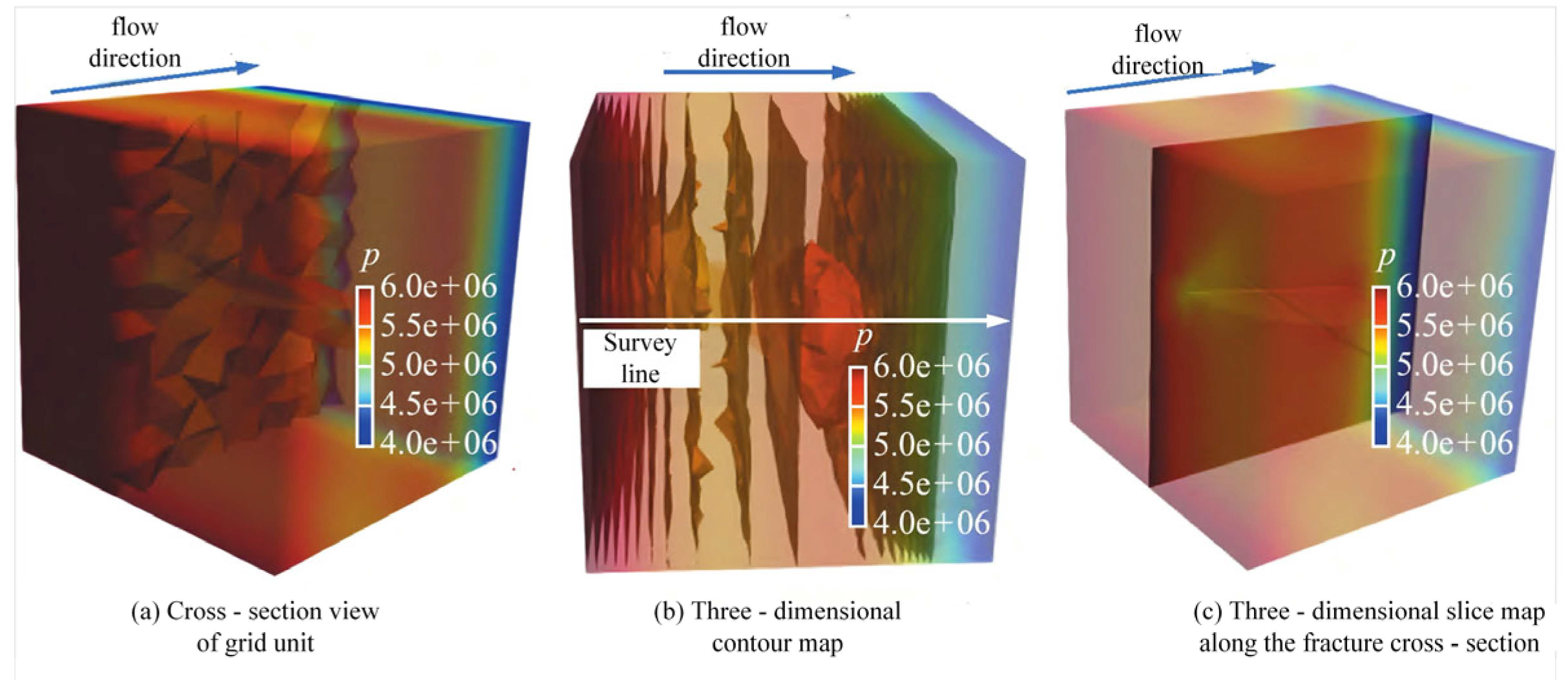

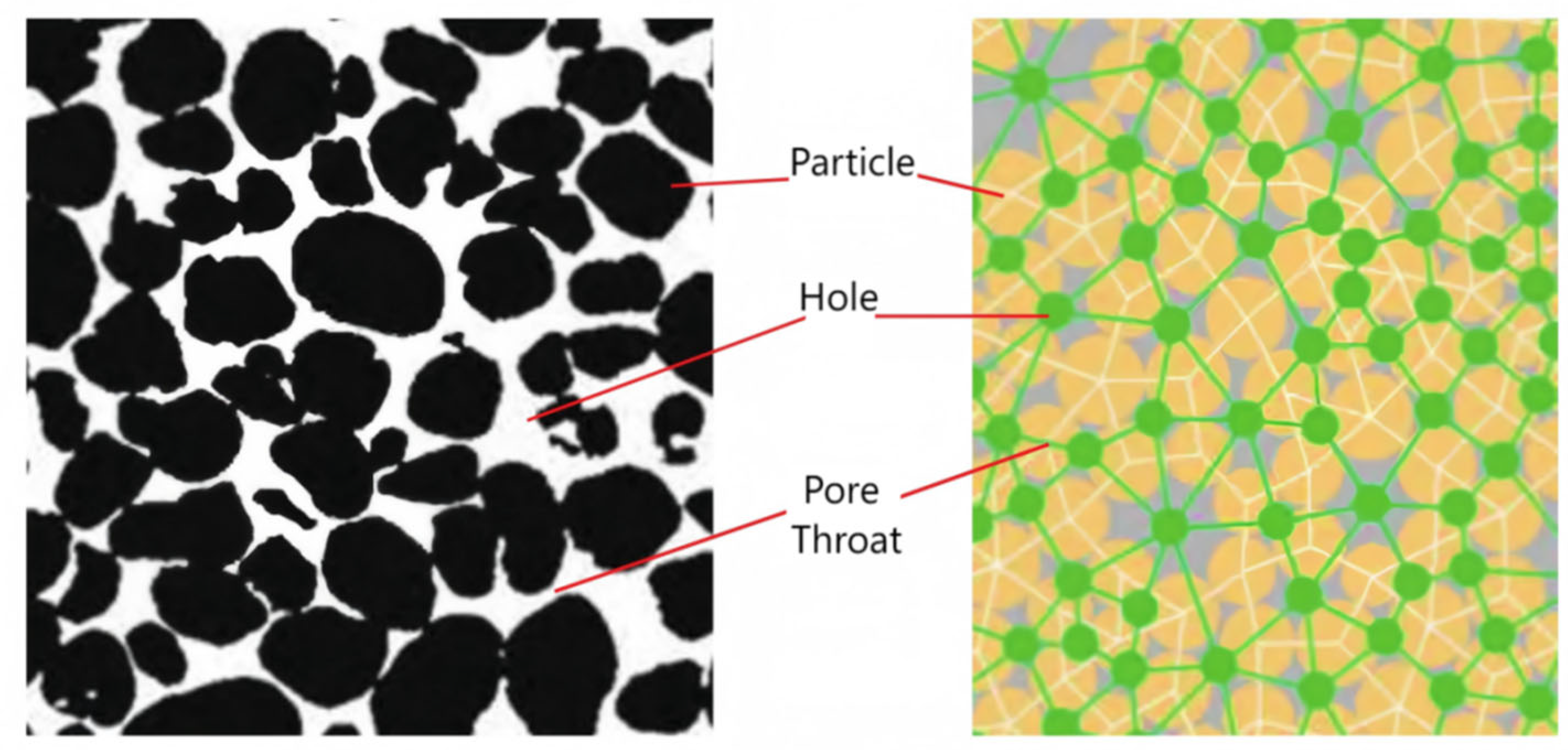

The geometric configuration and distribution of fractures significantly influence crack initiation locations and failure patterns in rock masses, while applied loading conditions markedly affect shear strength and deformation [22,23,24]. Uniaxial static direct shear tests reveal the shear strength and deformation characteristics of fractured rock [25]. Particle Flow Code in 2 Dimensions (PFC2D), a discrete element method-based particle-based simulation software, enables micromechanical modeling of the entire direct shear test process for fractured rock masses. It quantifies microcrack damage evolution and energy variations while investigating the influence of X-shaped fractures, Z-shaped fractures, and circular cavities on the micromechanical shear behavior of rock masses. Relevant scholars employed PFC to simulate how fracture dip angle affects crack propagation and coalescence in rock masses containing single or double fractures under uniaxial compression, biaxial compression, and confining pressure unloading conditions. The study identified crack coalescence patterns and observed that internal damage and coalesced fractures cause a sharp increase in dissipated energy. Growing demand for mineral resources drives continuous expansion of mining scale and depth, establishing surface mining as a primary method. Harsh weather conditions in cold regions present significant operational challenges. Extensive research exists on freeze-thaw damage in intact rock [26,27,28], with foundational studies addressing fracture evolution mechanisms in fractured rock under freeze-thaw cycles [29,30]. Ji developed a rock mass model containing intersecting fractures (Fig. 1) and devised an effective methodology for handling three-dimensional intersecting fractures, substantially improving mesh quality. Building on this, a fracture-pore dual-medium seepage model was introduced to systematically analyze the seepage characteristics of this three-dimensional intersecting fracture system [31].

Figure 1: Simulation of fluid pressure distribution in three-dimensional intersecting fractures seepage (a–c). Adapted with permission from Ref. [31]. Copyright © 2024, Chin J Comput Mech.

Fluid-solid coupling in fractured rock masses describes the interaction between fluid flow and stress fields: fluid pressure variations alter stress distributions, while stress-induced deformations (e.g., fracture aperture changes or propagation) conversely affect permeability. This dynamic coupling grows particularly complex in rock masses with pre-existing fractures, especially fault zones. As major discontinuities, faults readily develop tensile or shear damage under stress, leading to fracture network propagation and substantial permeability enhancement. Simultaneously, rapid fluid migration through dilated fractures under high pressure intensifies stress concentrations, accelerates damage evolution, and may trigger catastrophic water inrush. Lin established a damage-seepage coupling analysis model for rock masses and employed the FLAC3D numerical simulation software to simulate deformation characteristics, permeability coefficients, and the surrounding rock’s plastic zone, revealing its deformation and failure mechanism [32]. Triaxial tests under varying pre-existing fracture angles and confining pressures examined coupled processes during loading/unloading cycles, establishing a computational model for fluid-solid coupling in fractured rock. This model elucidates damage mechanisms, failure modes, and permeability evolution during such stress paths [33]. By establishing created a three-dimensional single-fracture seepage model to assess the influences of fracture geometry, particle size, and inflow velocity on fracture damage. This model reconstructed particle migration processes within fault fracture zones under stress-seepage coupling, revealing their progressive evolution [34].

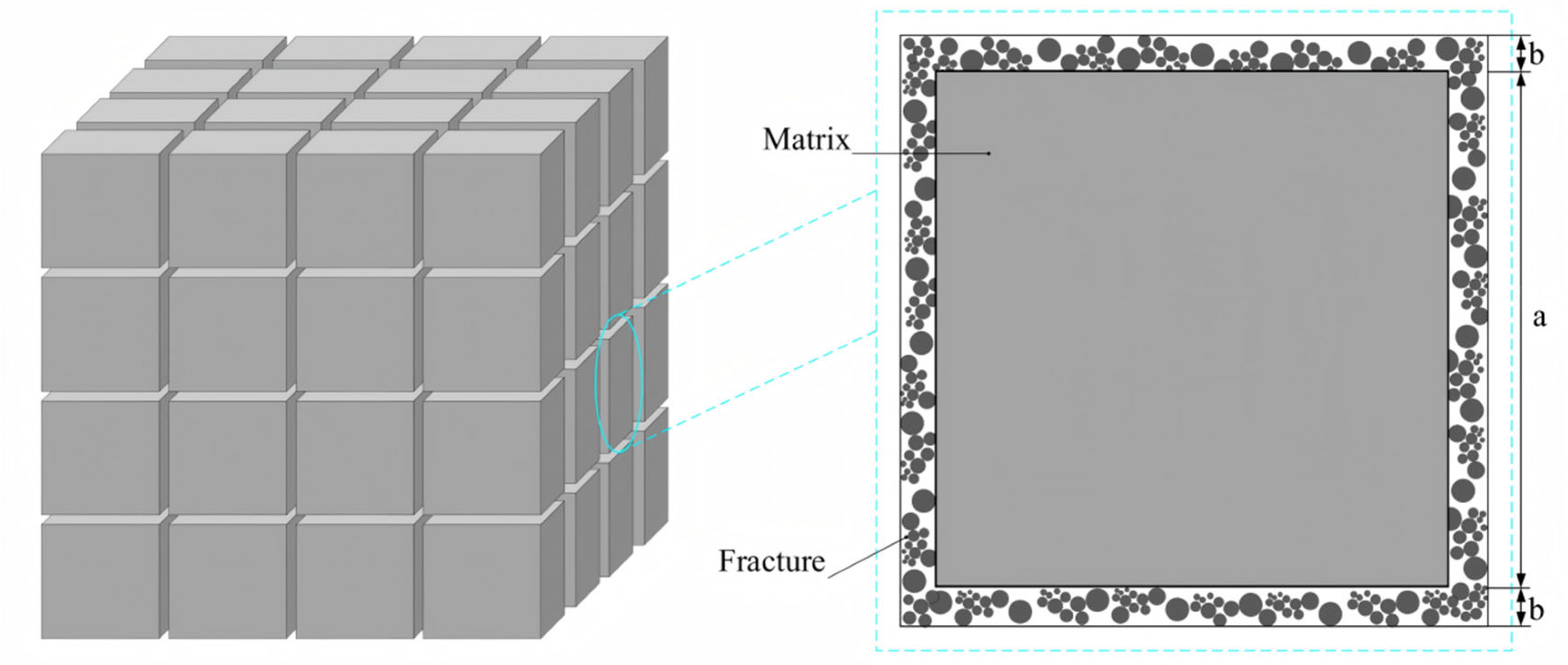

Sandstone samples containing single inclined rough fractures underwent stress-seepage coupling tests under cyclic axial compression and low-frequency pore pressure cycles. Cyclic axial compression progressively degradation in the fractured rock mass, weakening the samples’ deformation resistance. Scholars investigated seepage characteristics in fractured rock during drying-wetting cycles using single-fracture flow experiments. Theoretical analysis revealed distinct anisotropic permeability features. Cao reconstructed fine-grained sandstone fracture sample images using computed tomography and simulated grout migration within fractured rock using COMSOL software. The simulation ignored the rock matrix influence on slurry seepage as illustrated in Fig. 2, demonstrating permeability reduction effects and revealing permeability evolution patterns [35]. Rock fracture roughness significantly influences seepage characteristics. Gan experimentally examined limestone fracture seepage under stress-seepage-chemical coupling [36]. Results indicating that higher joint roughness coefficient (JRC) values correspond to lower seepage flow rates and permeability.

Figure 2: Structure diagram of a micro-element. Adapted with permission from Ref. [35]. Copyright © 2024, Sci Rep.

Fractured rock masses in nature frequently interact with fissure water, significantly impacting engineering stability. To analyze creep damage characteristics of fractured sandstone in water-rich environments, fluid-solid coupling creep tests were conducted on prefabricated specimens. A PSC-CFD coupling model was developed to analyze crack propagation laws in fractured rock masses under hydromechanical coupling. A quantitative creep damage evaluation method was proposed. To reduce computational cost without compromising accuracy, Li established a coupled approach integrating the finite volume method and peridynamics to simulate mechanical extension and fracturing processes in rock under hydromechanical coupling. This method proved effective, demonstrating its feasibility [37].

These researchers investigated damage mechanisms in fractured rock masses. Experiments involving granite under uniaxial/cyclic loading and freeze-thaw cycles, combined with monitoring techniques such as acoustic emission (AE) and digital image correlation (DIC), revealed damage initiation, evolution patterns, and their significant impacts on mechanical properties and permeability. The essence of hydromechanical coupling lies in the dynamic interaction between fluid pressure and rock deformation. This process becomes particularly complex in rock masses containing discontinuities such as faults. Numerical simulations (FLAC 3D, PFC, Comsol) and multi-field coupling experiments (under varying stress paths, seepage conditions, and fracture geometries) jointly elucidated governing laws for rock mass damage, failure mechanisms, seepage evolution, and permeability changes under coupled effects. This provides crucial insights for understanding water inrush channel formation and evolution.

2.2 Current Research Status on Porous Media through Damage and Stress-Seepage Coupling

Porous media are rock formations containing microscopic pores capable of storing and transmitting groundwater. Their high permeability provides natural pathways for groundwater movement. When faults activate or experience engineering disturbances, they form hydraulically weak zones. Pressurized water within the porous media rapidly discharges along these pathways. Simultaneously, the high storage capacity of porous media represents a significant potential water source. Faults intersecting such water-rich formations can trigger instantaneous release of substantial groundwater volumes, potentially causing large-scale, high-pressure water inrush disasters. Thus, porous media function both as water inrush conduits and material sources, with stress-seepage coupling primarily controlling fault-related water inrush risks and disaster magnitude.

Porous media are typically represented as continua or require background grids [38,39]. Tran proposed a novel hybrid discrete-continuum numerical method for simulating unsaturated flow in these materials. Comparison with Finite Difference Method (FDM) results validated its reliability [40]. The vertex-centered Finite Volume Method (FVM) is employed for porous media simulations. This approach utilizes unstructured grids for spatial discretization, effectively addressing non-matching grid issues at interfaces [41]. A poroelastic model couples fluid flow with changes in the medium’s stress state. It investigates relationships between the hydraulic properties of fractured porous media, their stress-strain state, and the fracture network structure. Research indicates permeability is primarily controlled by structural characteristics of the fracture system, characterized through seepage parameters [42]. TOUGH2, a mature hydrogeological simulator, solves multiphase multicomponent flow and heat transport problems. FLAC3D, widely used geomechanical analysis software, handles fluid-mechanical interactions. Coupling TOUGH2 with FLAC3D enables thermo-hydro-mechanical (THM) analysis of multiphase fluid flow and deformation within fractured porous rock [43].

During hydrodynamic modeling of flow through porous media, discontinuities may arise within the solution domain [44]. Wang developed a method for simulating flow in three-dimensional heterogeneous porous media and proposed an associated meshing strategy for discretizing complex computational domains. Analysis of hydraulic behavior in porous media containing intricate fracture networks showed that heterogeneous permeability distributions induce minor pressure field perturbations [45]. A computational homogenization technique for fluid flow in deformable micro-fractured porous media employs efficient multiscale methods for fluid-solid coupling analysis. Compared to direct numerical simulation, the proposed multiscale algorithm, based on domain integral constraints, efficiently yields accurate results [46]. The embedded discrete fracture modeling method simulates flow and transport processes in fractured porous media, incorporating a modified Bandis model that characterizes fracture mechanical response to flow-induced stress perturbations [47]. A closed-form continuum model describes fluid-solid coupling in porous media containing distributed fractures. Coupling microcrack propagation with seepage processes reveals the evolution of mechanical parameter heterogeneity and the control mechanisms for seepage characteristics under general loading [48].

Fracture enlargement generates high-permeability damaged zones; further expansion can trigger water inrush incidents. Studying damage mechanisms enhances understanding of seepage-stress coupling. A unified nonlocal damage model was established to simulate hydraulic fracturing in porous media, where fluid pressure drives damage evolution. Introducing nonlinear anisotropic permeability characterizes seepage differences between damaged zones and intact rock. Numerical verification confirms the model accurately simulates hydraulic fracture propagation [49]. Eghbalian formulated a continuum damage-poroelastic constitutive model, demonstrating that microcracks simultaneously influence poromechanical and hydraulic properties based on oriented density distribution. Microcracks govern damage progression by inducing significant anisotropy and degrading poroelastic performance [50]. A constitutive model for porous rock based on Continuum Damage Mechanics (CDM) unifies elastic, plastic, and damage behavior. It reveals pressure-sensitive plastic deformation laws and damage evolution mechanisms under drained and undrained conditions [51]. Chen conducted pore corrosion tests using a self-developed seepage corrosion device and established a porous rock creep model, as illustrated in Fig. 3. The introduced CRG model investigates rock fracture evolution patterns and macroscopic-microscopic parameter correlations. This study revealed that both instantaneous and creep mechanical properties primarily depend on contact parameters and porosity [52].

Figure 3: Prefabrication and loading of specimens. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [52]. Copyright © 2023, Comput Geotech.

In summary, extensive research has employed diverse numerical simulations to investigate stress-seepage field coupling in porous media and the resulting water inrush channel evolution. These methods effectively model fluid flow and stress-strain behavior within porous media while analyzing hydro-mechanical responses to heterogeneity and complex structures. Simultaneously, they reveal the intrinsic connection between damage evolution driven by fluid pressure—such as microcrack propagation and permeability anisotropy changes—and seepage-stress coupling in porous media.

3 Research Status on Mechanisms of Fault-Induced Floor Water Inrush

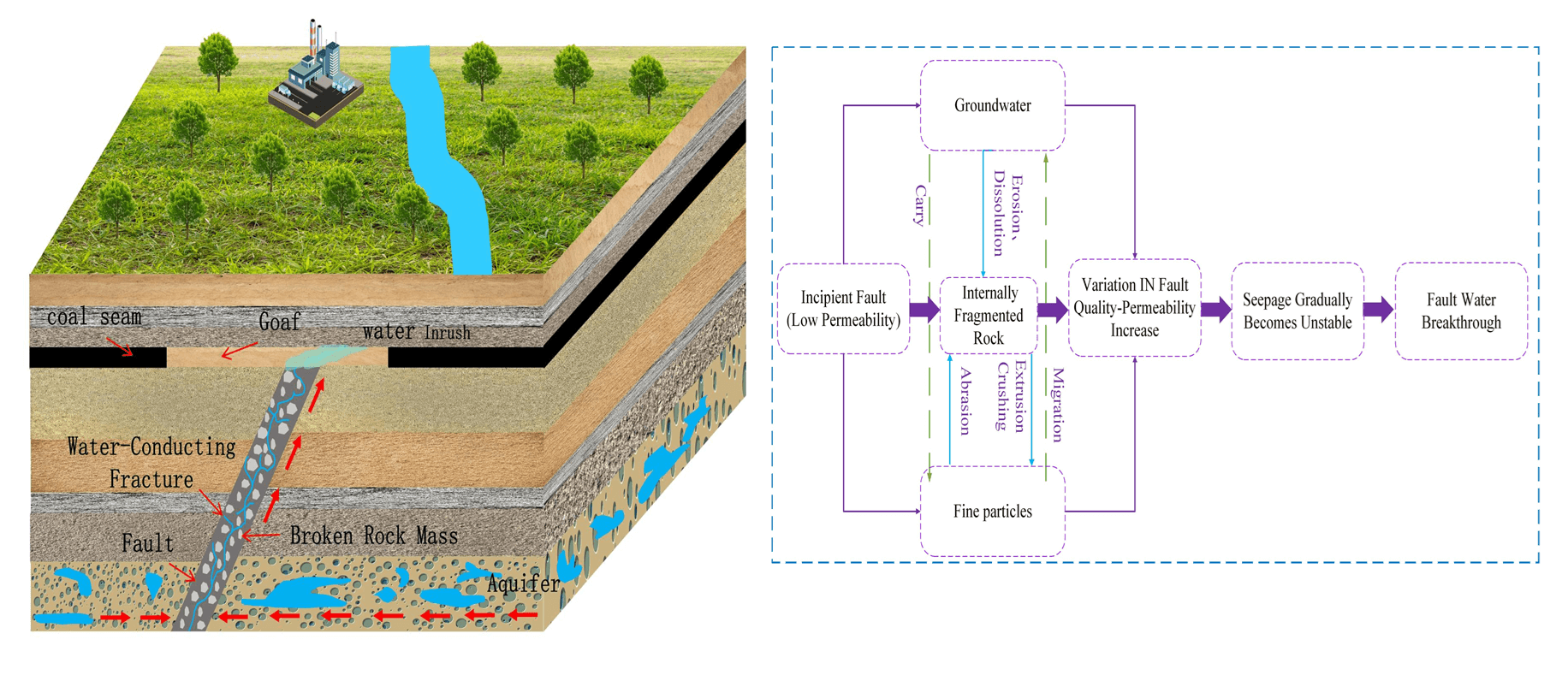

During coal seam mining, the presence of a fault within the floor strata between the coal seam and an aquifer alters the surrounding stress and displacement fields. If this alteration reactivates fault deformation, the fault can serve as a conduit for water, resulting in fault-induced water inrush disasters (Fig. 4). These disasters pose significant hazards. Researchers have employed theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, laboratory testing, and field monitoring to study the stress characteristics of floor faults under mining influence, the characteristics of water inrush through these faults, and the underlying mechanisms.

Figure 4: Schematic diagram of fault seepage and water inrush.

3.1 Stress Characteristics of Mining-Disturbed Floor Faults

Engineering practice reveals that mining-induced stress redistribution in surrounding rocks drives the activation, deformation, and failure of floor faults, ultimately forming water inrush pathways. This process occurs as follows: goaf formation disrupts the original stress equilibrium, redistributing stress fields within floor strata. This redistribution often causes significant stress concentration (particularly shear stress) or tensile stress release in fault zones and adjacent areas. Through integrated field testing, numerical simulation, and theoretical analysis, scholars examine the mechanical behavior of fault bodies under complex stress paths from different mining schemes. They analyze its influence on dynamic stress field evolution patterns in adjacent surrounding rock, focusing on fault body and adjacent stress field evolution under various mining-induced stress paths.

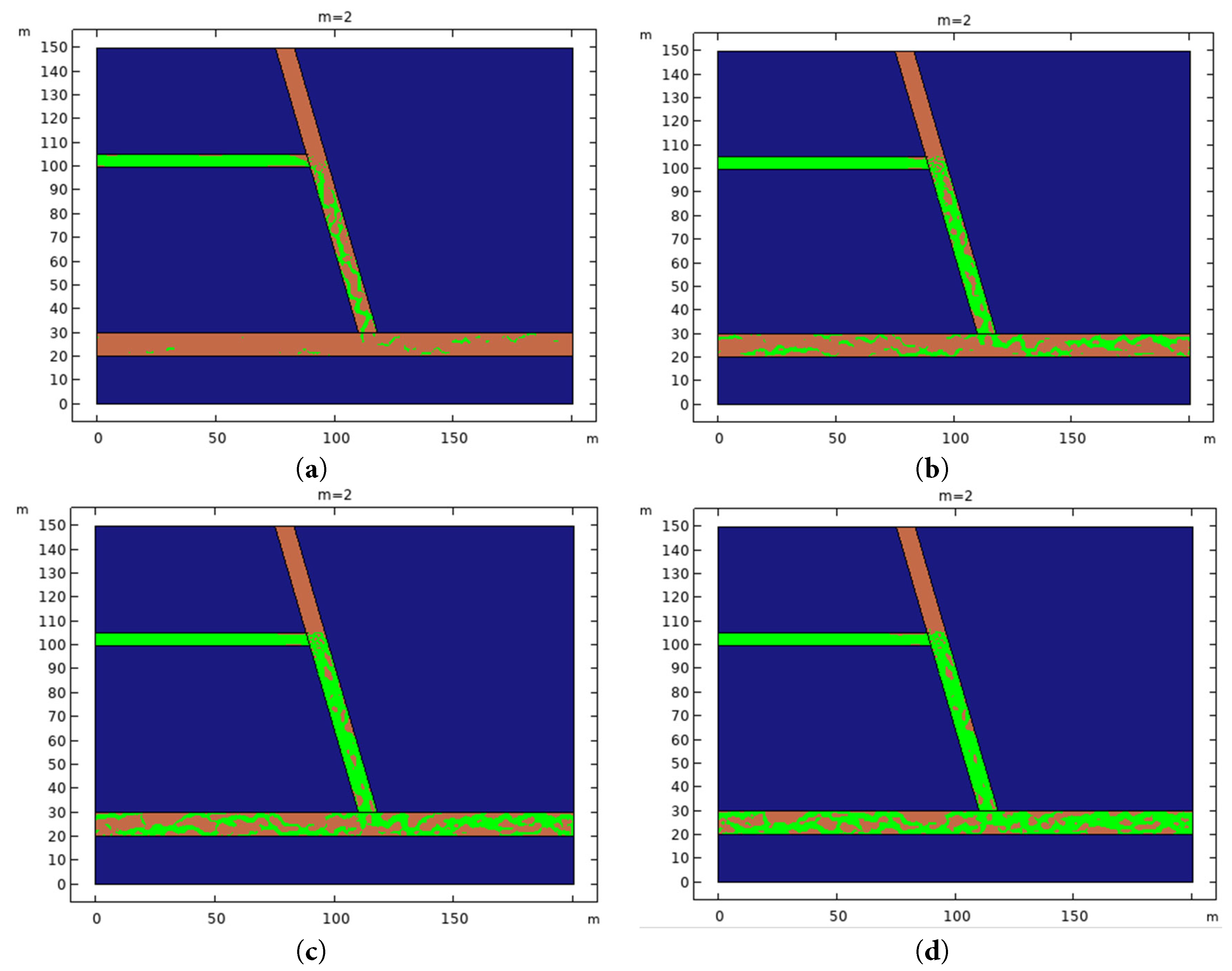

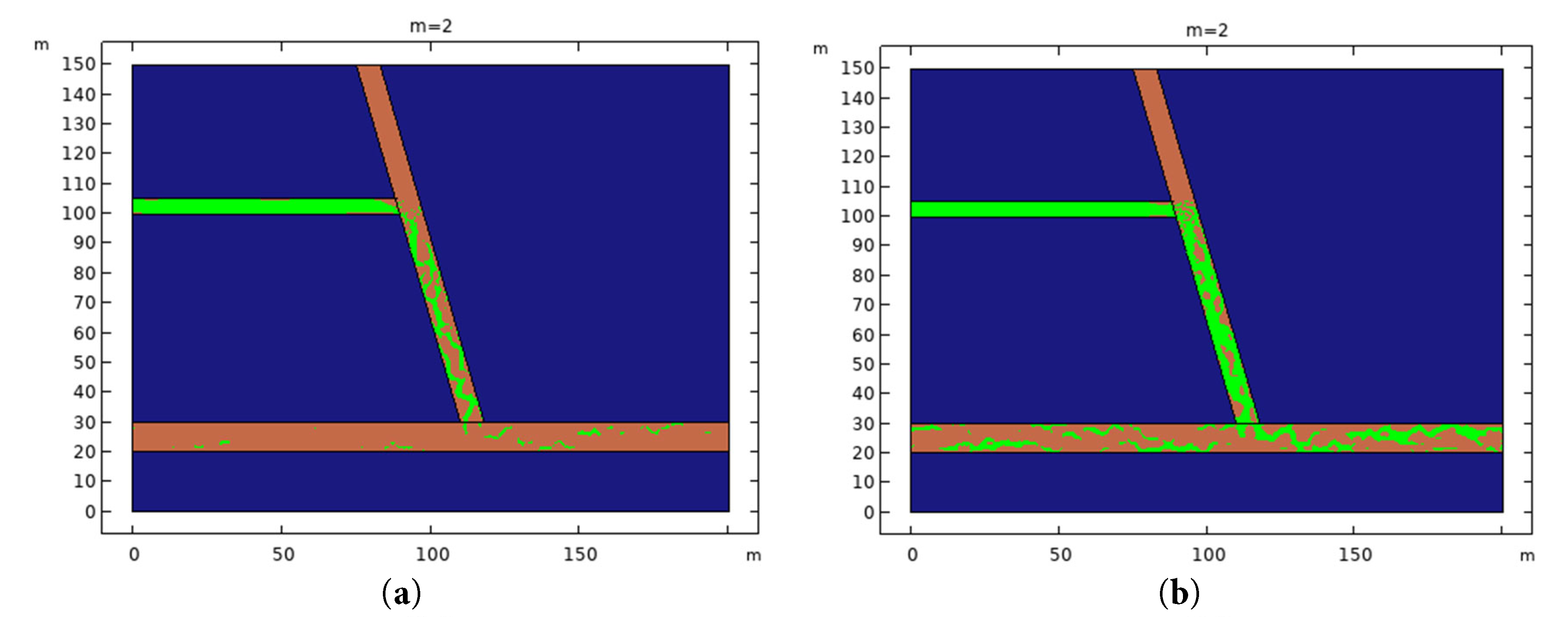

Alber developed a fault friction model using the Mohr-Coulomb failure criterion, analyzing the weakening effect on the safety factor of fault-containing coal seams via 3D elastic boundary element methods [53]. A fault slip model based on the same criterion incorporates cohesive strength weakening during slip [54]. Research using variable-angle normal fault models shows that dynamic stress redistribution in surrounding rocks, induced by mining disturbances, primarily controls fault slip. Different fault dip angles significantly regulate stress evolution paths and slip response characteristics [55]. Sun integrated Flac3D numerical simulation with physical similarity modeling to establish a model for fault stress-displacement response under mining (Fig. 5). This work revealed the mining disturbance mechanism: disturbance energy initially drives stress field (rather than displacement field) development to its peak. As the working face advances, overlying strata fracture macroscopically and connect with the fault zone, inducing fault activation [56].

Figure 5: A model for similar material simulation experiments and itsmonitoring system. Adapted with permission from Ref. [56]. Copyright © 2024, Coal Geol Explor.

Numerous scholars have conducted extensive research on the mining-induced stress state of floor faults [57,58,59,60,61,62,63]. Sainoki et al. employed numerical simulation to investigate how fault properties regulate slip displacement and energy release under excavation disturbance, revealing the dominant control of the internal friction angle [64]. Mining-induced dynamic stress primarily governs catastrophic fault slip. To understand the influence of hard roof rupture on fault slip, a static-dynamic coupling model was established using FLAC3D. This model demonstrated that dynamic loading from roof rupture significantly reduces fault stability, confirming dynamic load disturbance as a key factor inducing slip [65]. Numerical simulation by Liu elucidated stress-displacement field evolution and activation laws near reverse faults under mining disturbance: compared to hanging wall mining, footwall mining more readily triggers fault activation, exhibiting significantly greater intensity and influence scope [66]. Zhang et al. utilized FLAC numerical simulation to investigate fault influence on peak stress and plastic zone evolution in the floor during coal mining, analyzing peak floor stress and plastic zone patterns under different fault dip angles, stiffness values, and floor water pressures [67].

These studies employ mechanical criteria and numerical simulation while comprehensively considering factors such as fault dip angle, internal friction angle, stiffness, and external disturbances to elucidate the catastrophic mechanism of mining-induced stress redistribution driving fault activation. This provides a theoretical foundation for understanding fault-induced water inrushes.

3.2 Mechanisms of Water Inrush from Floor Faults

In coal mine water hazard prevention, fault water inrush represents one of the most destructive disasters during coal mining. Its occurrence arises from complex factors, including tectonic evolution, fluid seepage patterns, and mining-induced disturbances. Understanding its mechanisms is essential for enhancing early warning systems and prevention technologies for mine water hazards (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Mechanism of water inrush in faults.

Karst strata are globally widespread, covering approximately 25% of continental land. Areas with simple hydrogeological conditions have fewer coal mine floor water inrush incidents, while those with complex settings face significant safety threats from such events. Mironenkor identified mining-induced changes in surrounding rock stress fields, fracture development, and hydrostatic pressure fluctuations as primary causes [68]. Motyka emphasized that hydraulic connections between mining-induced floor fractures and underlying confined aquifers critically trigger inrushes [69], while Kuscer systematically described aquifer water level dynamics during inrush processes [70]. Increasing mining depth subjects strata to high ground stress, elevated water pressure, and intense mining disturbance. The thickness of the relatively impermeable floor layer gradually diminishes, substantially increasing water inrush risk under aquifer pressure [71]. Introduced in the 1940s, the concept of a relatively impermeable floor layer centers on its thickness being crucial for preventing and controlling floor water inrush. Aquifer pressure beneath the floor shows a significant negative correlation with this layer’s effective thickness—as water pressure increases, effective thickness decreases [72,73]. Sammarco et al. monitored aquifer water level changes to obtain water inrush precursors for early warning, characterizing mine floor water inrush as a complex dynamic coupling process between confined water and strata during mining [74,75]. Yao established a conceptual model of “mining damage and fault erosion synergistically inducing disasters”. As the working face advances, seepage channels connecting the aquifer, fault, mining-induced fractures, and goaf progressively connect. Continuous erosion promotes development into dominant water-conducting channels, ultimately triggering sharp increases in working-face water inflow and delayed inrush disasters [76].

Bai et al. proposed a three-stage water inrush evolution process (unsaturated seepage, Darcy flow, and rapid seepage), validating the theoretical model’s rationality through numerical simulation [77]. Li et al. employed a CFD-FDEM coupled model to simulate the activation and water inrush process within extremely thick coal seam floor faults under large-amplitude loading and unloading. This revealed the failure characteristics of floor faults under mining stress and the formation mechanism of water inrush channels [78]. A fracture mechanics catastrophe model was established to study the water inrush mechanism in fault branches under mining influence. Incorporating the effects of seepage and stress on fault branches and based on the Mohr-Coulomb criterion for rock mass compression-shear fracture, the model investigated the influence of fault dip angle, minimum principal stress, main fault length, and seepage water pressure on critical water pressure and minimum safe distance. This provides a theoretical basis for preventing coal mine floor water inrushes [79]. Zhou et al. observed that major faults can simultaneously intersect coal seams and aquifers. These faults typically serve as water-conducting structures, directly connecting aquifers and coal seams. In such cases, water inrush accidents may occur as the working face approaches the fault [80]. Although most minor faults lack direct connection to the coal seam, they are susceptible to activation under coupled mining stress and water pressure effects [81,82,83], forming water inrush channels. Fault activation is governed by the degree of stress concentration at the fault tip induced by mining and depends on the spatial relationship between the fault and the working face.

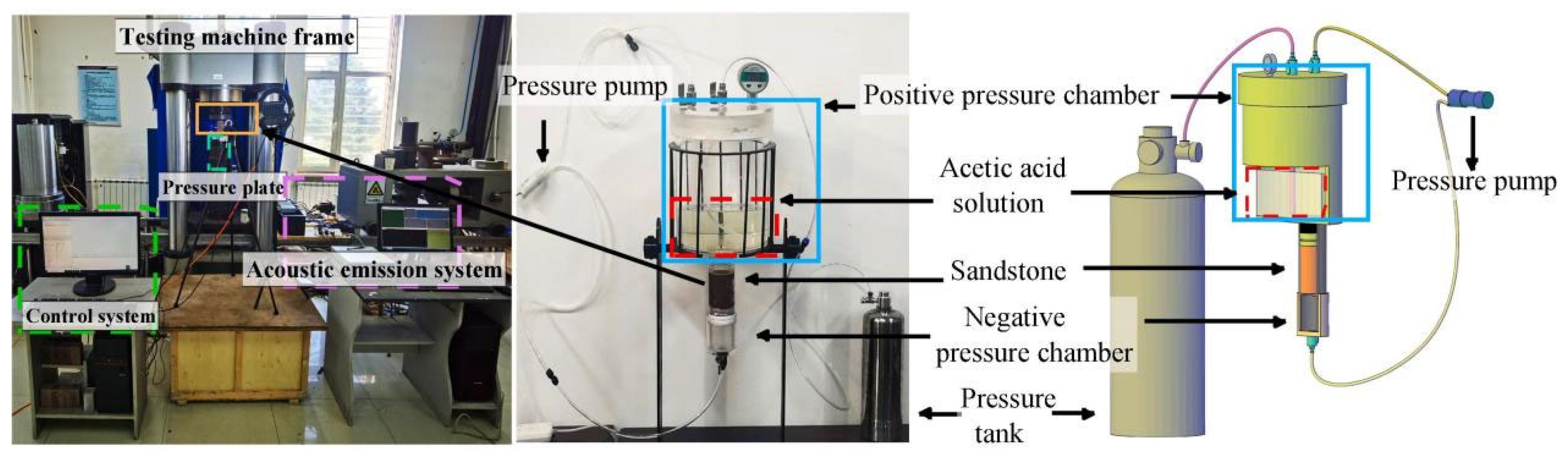

With advances in seepage-stress coupling testing equipment and methodologies, comprehensive experiments on rock stress-strain-permeability—including those by Souley et al. [84] and Park [85]—provide essential data revealing the mechanical and seepage characteristics of overlying and underlying strata. Fig. 7 illustrates the principle of a classic seepage-stress coupling experiment. Significant differences exist in stress-strain-permeability characteristics among rocks of varying lithologies. Based on comparative test data from four rock types, Zhang proposed quantitative indicators for evaluating the rock seepage-stress coupling process [86]. Many researchers consider floor water inrush a catastrophic process wherein coupled seepage and stress fields evolve toward instability within the rock mass. The study of rock-fluid interactions originated in soil mechanics. Terzaghi established effective stress theory [87], later refined by Biot through the effective stress coefficient concept [88]. To reveal the water inrush mechanism in intact strata during seepage-stress coupling, modeling and simulation studies have been conducted. These models demonstrate surrounding rock continuously undergoing crack initiation and propagation under coupled fields, ultimately forming seepage channels and triggering water inrush [89]. Li et al. developed a compression-shear-seepage coupling test system for fractured rock masses based on fluid-solid coupling theory. They simulated coupled shear deformation and seepage processes using the discrete element method to model fractured rock pore networks (Fig. 8) [90]. Multi-variable experiments revealed that particle migration within the shear band of fractured rock under shear loading drives increased porosity and permeability.

Figure 7: Stress–strain-permeability test schematic. Reprinted with permission from Ref. [86]. Copyright © 2021, Mine Water Environ.

Figure 8: Simulation method of crushed rock. Adapted with permission from Ref. [90]. Copyright © 2023, Coal Geol Explor.

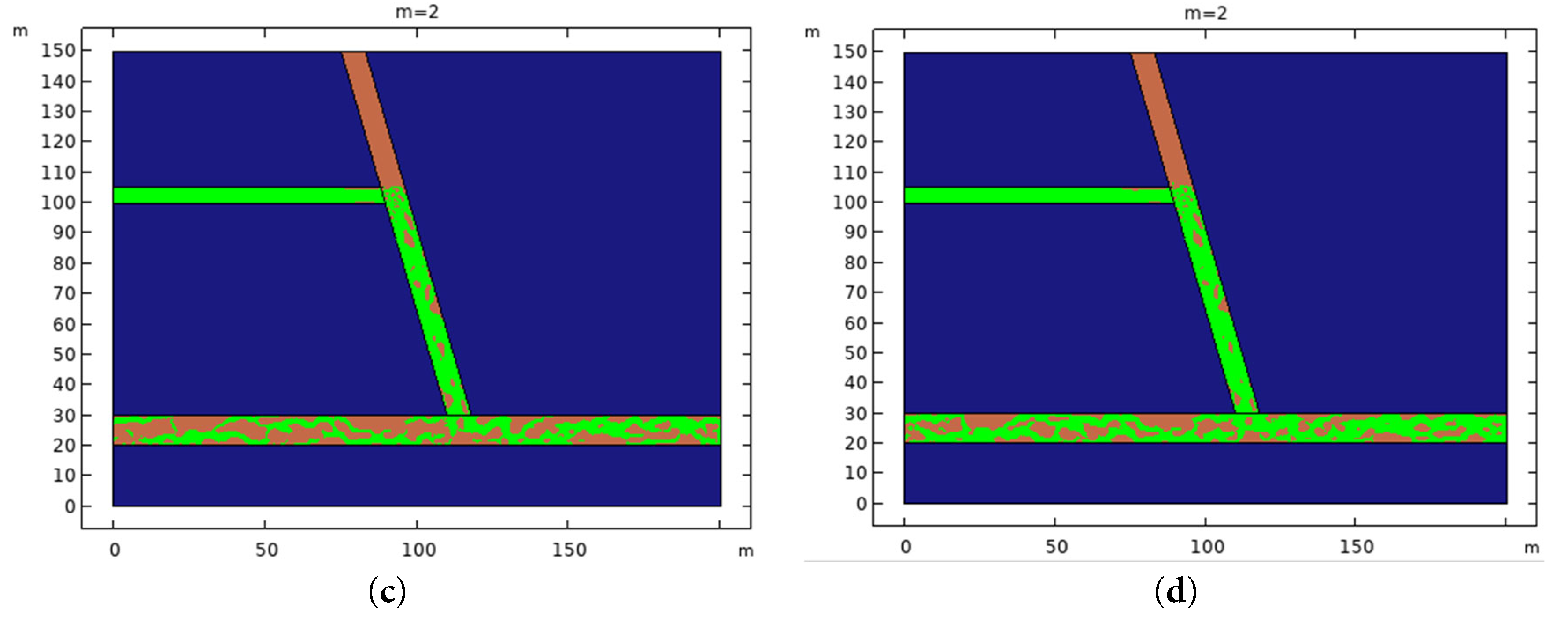

To investigate the evolution of mining-induced fault seepage channels and fluid flow patterns, Jia developed a water inrush model for fractured rock masses under seepage conditions. Simulations under four aquifer pressure conditions (Fig. 9) reveal the fluid channel evolution: initially formed localized seepage zones expand into continuous pathways. As aquifer and fault flows interconnect, continuous particle migration increases porosity and permeability. This enlarges water-conducting fractures and accelerates seepage velocity. Enhanced velocity intensifies particle migration, establishing a positive feedback loop that persistently amplifies permeability and fracture dilation, ultimately inducing water inrush at the working face [91].

Figure 9: Seepage channels in fault formed at different times. (a,b) Adapted with permission from Ref. [91]. Copyright © 2025, Jia Y. (a) 0.5 h, (b) 1 h, (c) 1.5 h, (d) 2 h.

The above research indicates that mining disturbance-induced alterations to the stress field, fracture propagation, hydrostatic pressure fluctuations, and hydraulic connections between mining-induced floor fractures and confined aquifers are key triggers for water inrush. Furthermore, water inrush risk escalates significantly with depth. Analysis shows that relative aquitard thickness exhibits a strong negative correlation with aquifer pressure, making it critical for prevention and control. This study lays the theoretical groundwork for investigating rock mechanics, seepage characteristics, water inrush mechanisms, and prevention strategies.

4 Research Status on Water Inrush Prevention Techniques for Floor Faults in Pressurized Aquifer Working Faces

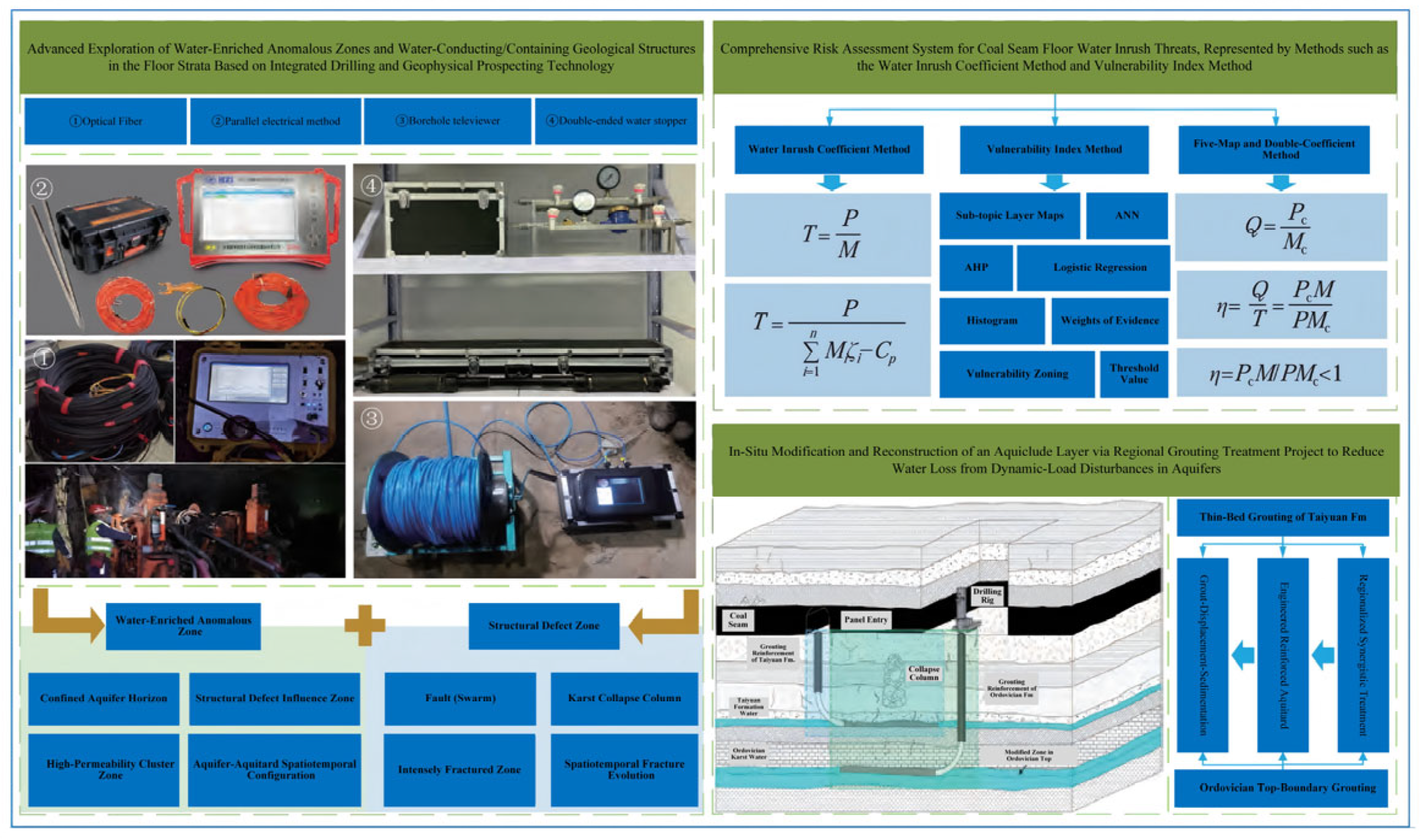

After decades of research on mine water hazard control, prevention theories and technologies for floor water hazards are now mature. Current studies on preventing water inrushes through floor faults focus primarily on detecting fault occurrence and water-richness, implementing control measures, and evaluating/predicting water inrush risks [92,93,94,95,96], establishing a comprehensive technical framework for prevention and control (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: Coal seam floor water disaster prevention and control technology system architecture. Adapted with permission from Ref. [92]. Copyright © 2025, J China Coal Soc.

4.1 Measures for Preventing Water Inrush from Floor Faults

Current technologies for preventing water inrushes from confined aquifers in mine floors and controlling fault activation include theoretical analysis, precise detection, grouting sealing, drainage depressurization, and waterproof coal pillar design. These methods have demonstrated effectiveness in engineering applications. Based on water abundance, floor faults are categorized as non-water-bearing or water-bearing. Non-water-bearing faults generally require no specialized water hazard prevention measures. For water-bearing faults, targeted strategies—such as grouting sealing, drainage depressurization, or combined approaches—must be selected following evaluation of fault geometry, aquifer water abundance, and fault-aquifer hydraulic connectivity [97,98,99,100].

Field practices for confined water hazard control primarily use drainage depressurization and grouting techniques, including floor drainage, floor reinforcement, and fault grouting. Liu et al. studied grout effects on fractured rock masses using a self-developed grouting system, conducting normal and shear mechanical tests on reinforced specimens. Results indicated grouting significantly altered fracture shear shrinkage/dilation characteristics [101]. Relevant scholars proposed multi-stage advance grouting reinforcement in mining panels, achieving substantial inflow reduction and validating the technique’s efficacy. Grouting modification of aquifers effectively mitigates water inrush risks and ensures mining safety. Zhang et al. developed a grouting material comprising rubber particles, fly ash, clay, and nano-silica through orthogonal testing. Its superior fluidity, compressive strength, and impermeability meet floor reinforcement requirements [102] (Fig. 11).

Figure 11: Test process of solid waste grouting materials. Adapted with permission from Ref. [102]. Copyright © 2023, Coal Sci Technol.

Technological advances in monitoring have significantly enhanced groundwater inrush detection. Common methods include borehole injection, rock displacement/hydrological borehole detection, and 3D geophysical prospecting techniques such as infrared, transient electromagnetic, seismic exploration, and ground-penetrating radar [103,104]. Overcoming bottlenecks in microseismic monitoring requires integrating advanced theories and intelligent algorithms to improve system capabilities for identifying low signal-to-noise ratio precursor signals and enhancing localization accuracy [105,106]. Researchers implemented combined borehole-surface microseismic monitoring to achieve comprehensive risk assessment for working face water inrush. Another team developed a mine water monitoring and risk early-warning platform, elucidating mechanisms of typical water hazards, establishing identification criteria and warning indicators, and enabling visualized risk alerts throughout above- and below-ground spaces. This supports intelligent mine water hazard prediction [107].

Current engineering practice for preventing fault activation water inrush primarily relies on establishing waterproof coal pillars. Research focuses on optimizing theoretical modeling, parameter refinement, and factor identification. Researchers developed a formula for mining-induced rock failure depth from multiple perspectives incorporating ground pressure, structural features, and hydraulic fracturing. They subsequently created a computational model for waterproof coal pillar width accounting for water pressure and fault influences [108]. Other researchers established an exact formula for confined water pressure at arbitrary locations and a width calculation model for waterproof coal pillars. This refined design methodology under fault-induced water conduction significantly enhances precision [109]. Another study proposed partitioned analysis for setting fault waterproof coal pillars, introducing design approaches based on fault hydraulic conductivity characteristics while conducting safety stability evaluations. This provides technical support for fault water inrush control [110].

Research indicates that grouting reinforcement enhances fracture mechanical properties, controls water inflow, and mitigates water inrush risks. Water inrush monitoring integrates technologies such as borehole grouting and geophysical exploration to achieve multi-source information fusion, dynamic process analysis, and intelligent early warning. Fault-induced water inrush prevention primarily utilizes grouting and water-resistant coal pillars, where theoretical optimization, parameter design, and engineering validation provide critical foundations for safety design.

4.2 Evaluation and Prediction of Water Inrush Potential in Floor Faults

Accurate prediction of floor water inrush risk is critical for safe mining in confined water coal seams. Modern technology offers advanced support in forecasting this risk [111,112,113,114]. High-risk zones can be identified through water inrush evaluation—integrating hydrogeological and engineering geological characteristics to analyze fault-related natural and mining-induced hazards—and prediction, which quantitatively forecasts the spatiotemporal scale of inrushes relative to mining activities. Researchers have established sophisticated evaluation frameworks using models including gray theory, fuzzy mathematics, catastrophe theory, analytic hierarchy process, and neural networks. These frameworks underpin risk grading and prevention decision-making for fault-related water inrushes in aquifer working faces, enabling stage division of disaster risk assessment and hierarchical early warning, as illustrated in Fig. 12.

Figure 12: The stage division of risk assessment and hierarchical early warning.

Precise identification of water sources causing mine inrushes is essential for safe extraction. Analysis of accident cases by Sammarco revealed that abnormal changes in aquifer water levels and gas concentrations can serve as precursor information for inrushes [115]. For a specific mine, scholars used an integrated approach combining Piper trilinear diagrams, hierarchical cluster analysis, and gray relational analysis for water source identification. Based on ANSYS simulations of complex synclinal coal seam bedding, Sakhno proposed a risk assessment algorithm for aquifer water inrushes. This algorithm showed that the stress-strain safety factor can serve as a criterion for rock mass failure [116]. Shi Longqing and colleagues developed a probability index model for floor water inrushes. They proposed theories for Ordovician limestone water abundance evaluation using gray correlation-FDAHP integrated with geophysical exploration, gray theory-based water inflow prediction, multi-attribute decision-making, and floor water inrush risk early warning [117]. Jiao designed a mine water source identification system based on an improved Fisher discriminant principle, enabling rapid identification of temporary inrush point water sources [118].

Conventional understanding holds that fluid movement within aquifers follows a linear laminar flow regime, where fluid pressure and velocity exhibit a linear relationship [119,120]. However, groundwater flow within mined-out spaces becomes turbulent following water inrush. This indicates a nonlinear relationship between water pressure and velocity; increased pressure does not proportionally increase flow. Identifying the fluid movement state and studying its transition mechanism have significant engineering importance for water inrush hazard assessment and inflow prediction [121]. Coal mine water inrush connects shallow surface water bodies with deep aquifer exploitation. Water inrush may occur when overburden strata above the coal seam roof fail and the water-conducting fracture zone reaches the aquifer [119]. Consequently, determining the separation height of overburden strata in the working face is critical for assessing water inrush risk. The “Voussoir Beam Theory” forms the foundation of the “Key Stratum Theory for Strata Control”. Integrating mining pressure, overburden movement patterns, and surface subsidence, the Key Stratum Theory better explains the evolution of overlying rock fractures under mining influence. Wang et al. combined deep beam theory with numerical simulation to reveal the mechanical properties of the key water-resisting stratum in deep mining floor strata. Through shallow beam decomposition and interlayer compressive stress coupling, they verified the high accuracy of the deep beam strip method for stress analysis, establishing a theoretical basis for predicting deep water inrushes [122]. In addition, the amplification effects of mining-induced fault slip in heterogeneous strata under deep mining conditions, along with the source mechanisms of mining-induced dynamic fault ruptures—both recognized as prominent research frontiers—are well documented in the work of Li et al. [123,124,125,126,127]. These findings underscore the need for further investigation into deep-mining fault dynamics, including the amplification of fault slip in heterogeneous strata, coseismic rupture mechanisms, and the associated transient surges in permeability.

Based on water inrush evaluation and prediction systems, precise water source identification technology, and rock stratum rupture theory, the above research comprehensively considers key factors including fault activation, aquifer recharge, nonlinear fluid flow, and overburden failure height. It proposes a graded early warning method for water inrush risk and water inflow prediction. This provides systematic theoretical and technical support for the advanced identification and prevention decision-making of floor water inrush risk during pressurized-water coal seam mining.

5 Limitations of Existing Research and Future Research Directions

Coal floor water inrush disasters induced by fault activation in pressurized aquifers at working faces subjected to mining disturbance represent a critical scientific challenge that demands urgent attention in mine water hazard prevention. This paper systematically addresses damage to fractured floor rock masses and porous media, water inrush mechanisms, and prevention technologies, providing essential theoretical foundations for disaster control. Nevertheless, several issues require further investigation.

- (1)Research on fractured floor rock failure has achieved significant advances in multiphysical coupling mechanisms and meso-damage theories. However, damage evolution mechanisms in deep engineering environments under coupled high ground stress, elevated temperatures, and high seepage pressures remain insufficiently explored. Specifically, dynamic fracture propagation feedback mechanisms under seepage-stress-temperature multiphysics coupling lack a systematic theoretical framework. Existing models rely primarily on simplified assumptions, inadequately accounting for porous media effects on water-rock interactions. This causes deviations between predicted damage evolution and engineering observations. Future studies should develop multiphysics coupling models incorporating pore effects to elucidate dynamic fracture evolution patterns in deep coal floors through enhanced theoretical frameworks. Particular attention must focus on how mining-induced stress disturbances under deep high-stress conditions influence fracture network initiation, propagation, and connectivity near fault zones via multiphysics coupling. This underpins understanding fault activation.

- (2)The current theoretical framework for floor water inrush primarily addresses conventional geological conditions. Research on water inrush mechanisms through fault structures in mining faces within confined aquifers remains inadequate. Crucially, coupling criteria integrating fault zone composition, structural characteristics, and the dynamic evolution of mining-induced stresses remain unexplored. Physical simulation methods face constraints due to difficulties replicating complex field conditions, causing systematic result deviations. Additionally, unified theoretical formulas for critical parameters such as critical water pressure and key stratum thickness are lacking. Future research must incorporate advances in deep mining fault dynamics, including mining-induced fault slip amplification effects in heterogeneous rock strata, coseismic rupture mechanisms, and associated transient permeability surge effects. Multiscale simulation techniques spanning microscopic fractures to macroscopic inrush processes should be developed. Cross-scale coupling analyses should focus on revealing the dynamic process of fault slip instability (coseismic rupture) under mining stress disturbances, permeability surge patterns, and their spatiotemporal correlation with inrush channel formation. This will enable constructing a comprehensive evolution model for water inrush disasters incorporating fault dynamics and establishing dynamic coupling criteria for fault activation and water inrush integrating slip amplification and permeability mutation characteristics.

- (3)Existing prevention technologies for fault-induced water hazards rely primarily on macroscopic engineering measures. Targeted treatment techniques and specialized equipment for pressurized aquifer faults lag significantly. Conventional grouting materials exhibit limited penetration in complex fractures due to physicochemical constraints. Mainstream geophysical detection methods in deep environments are prone to interference, impeding effective early-warning signal acquisition. Current monitoring systems yield predominantly discrete point data, lacking comprehensive precursor analysis. Research must prioritize directional grouting reinforcement technologies for complex stress environments and intelligent monitoring and early-warning equipment. This will establish an integrated prevention system encompassing hazard prediction, precision reinforcement, and real-time monitoring.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research is supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (242300421246), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52004082, U24B2041, 52174073, 52274079), the Key Research and Development Program of Henan Province (251111320400), the Program for Science & Technology Innovation Talents in Universities of Henan Province (24HASTIT021), the Program for the Scientific and Technological Innovation Team in Universities of Henan Province (23IRTSTHN005).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Zhengzheng Cao, Fangxu Guo; data collection: Wenqiang Wang; analysis and interpretation of results: Feng Du, Zhenhua Li, Shuaiyang Zhang; graphics and curves: Qixuan Wang, Yongzhi Zhai; draft manuscript preparation: Fangxu Guo. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data and models generated or used during the study appear in the submitted article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Hower JC , Finkelman RB , Eble CF , Arnold BJ . Understanding coal quality and the critical importance of comprehensive coal analyses. Int J Coal Geol. 2022; 263: 104120. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2022.104120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Bórawski P , Bełdycka-Bórawska A , Holden L . Changes in the Polish coal sector economic situation with the background of the European union energy security and eco-efficiency policy. Energies. 2023; 16( 2): 726. doi:10.3390/en16020726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mishra A , Das N , Chhetri P . Sustainable strategies for the Indian coal sector: an econometric analysis approach. Sustainability. 2023; 15( 14): 11129. doi:10.3390/su151411129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Homand-Etienne F , Hoxha D , Shao JF . A continuum damage constitutive law for brittle rocks. Comput Geotech. 1998; 22( 2): 135– 51. doi:10.1016/S0266-352X(98)00003-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Wang D , Sui W , Ranville JF . Hazard identification and risk assessment of groundwater inrush from a coal mine: a review. Bull Eng Geol Environ. 2022; 81( 10): 421. doi:10.1007/s10064-022-02925-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li X , Xue Y , Zhang Z . Progressive evolution model of fault water inrush caused by underground excavation based on multiphysical fields. Geofluids. 2023; 2023( 1): 8870126. doi:10.1155/2023/8870126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhu L , Cui S , Pei X , Cheng J , Liang Y . Experimental investigation of the fatigue damage and strength characteristics of heterogeneous rock mass under cyclic loading. KSCE J Civ Eng. 2022; 26( 6): 3007– 18. doi:10.1007/s12205-022-2354-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bui TA , Wong H , Deleruyelle F , Xie LZ , Tran DT . A thermodynamically consistent model accounting for viscoplastic creep and anisotropic damage in unsaturated rocks. Int J Solids Struct. 2017; 117: 26– 38. doi:10.1016/j.ijsolstr.2017.04.015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Amitrano D , Helmstetter A . Brittle creep, damage, and time to failure in rocks. J Geophys Res Solid Earth. 2006; 111( B11): 201. doi:10.1029/2005JB004252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Meng QB , Liu JF , Xie LX , Pu H , Yang YG , Huang BX , et al. Experimental mechanical strength and deformation characteristics of deep damaged–fractured rock. Bull Eng Geol Environ. 2021; 81( 1): 32. doi:10.1007/s10064-021-02529-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao C , Zhang Z , Wang S , Lei Q . Effects of fracture network distribution on excavation-induced coupled responses of pore pressure perturbation and rock mass deformation. Comput Geotech. 2022; 145: 104670. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.104670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Walton G , Alejano LR , Arzua J , Markley T . Crack damage parameters and dilatancy of artificially jointed granite samples under triaxial compression. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2018; 51( 6): 1637– 56. doi:10.1007/s00603-018-1433-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yao N , Ruan X , Liu Y , Ye Y , Zhang W , Oppong F . Particle flow simulation study of damage evolution in expansive slurry–fractured rock mass composites under direct shear conditions. Int J Geomech. 2024; 24( 6): 04024106. doi:10.1061/ijgnai.gmeng-9434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bubshait A , Jha B . Coupled poromechanics-damage mechanics modeling of fracturing during injection in brittle rocks. Int J Numer Meth Eng. 2020; 121( 2): 256– 76. doi:10.1002/nme.6208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. David EC , Brantut N , Schubnel A , Zimmerman RW . Sliding crack model for nonlinearity and hysteresis in the uniaxial stress–strain curve of rock. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2012; 52: 9– 17. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2012.02.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Shirole D , Hedayat A , Walton G . Damage monitoring in rock specimens with pre-existing flaws by non-linear ultrasonic waves and digital image correlation. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2021; 142: 104758. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Kim JS , Lee C , Kim GY . Estimation of damage evolution within an in situ rock mass using the acoustic emissions technique under incremental cyclic loading. Geotech Test J. 2021; 44( 5): 1358– 78. doi:10.1520/gtj20190299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Zafar S , Hedayat A , Moradian O . Micromechanics of fracture propagation during multistage stress relaxation and creep in brittle rocks. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2022; 55( 12): 7611– 27. doi:10.1007/s00603-022-03045-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nadimi S , Shahriar K , Sharifzadeh M , Moarefvand P . Triaxial creep tests and back analysis of time-dependent behavior of Siah Bisheh cavern by 3-Dimensional Distinct Element Method. Tunn Undergr Space Technol. 2011; 26( 1): 155– 62. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2010.09.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Sisodiya M , Zhang Y . A time-dependent directional damage theory for brittle rocks considering the kinetics of microcrack growth. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2022; 55( 5): 2693– 710. doi:10.1007/s00603-021-02577-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Imani M , Walton G , Moradian O , Hedayat A . Temporal and spatial evolution of non-elastic strain accumulation in stanstead granite during brittle creep. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2025; 58( 1): 275– 99. doi:10.1007/s00603-024-04170-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tremblay D , Simon R , Aubertin M . A constitutive model to predict the hydromechanical behavior of rock joints. In: Proceedings of the 60th CGC and 8th Joint CGS/IAH-CNC Groundwater Conference; 2007 Oct 21–25; Ottawa, ON, Canada. [Google Scholar]

23. Halakatevakis N , Sofianos AI . Correlation of the Hoek–Brown failure criterion for a sparsely jointed rock mass with an extended plane of weakness theory. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2010; 47( 7): 1166– 79. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2010.06.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Fereshtenejad S , Kim J , Song JJ . Experimental study on shear mechanism of rock-like material containing a single non-persistent rough joint. Energies. 2021; 14( 4): 987. doi:10.3390/en14040987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Mashhadiali N , Molaei F . Theoretical and experimental investigation of a shear failure model for anisotropic rocks using direct shear test. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2023; 170: 105561. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Yahaghi J , Liu H , Chan A , Fukuda D . Experimental and numerical studies on failure behaviours of sandstones subject to freeze-thaw cycles. Transp Geotech. 2021; 31: 100655. doi:10.1016/j.trgeo.2021.100655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Park K , Kim K , Lee K , Kim D . Analysis of effects of rock physical properties changes from freeze-thaw weathering in Ny-Ålesund region: part 1—experimental study. Appl Sci. 2020; 10( 5): 1707. doi:10.3390/app10051707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Abdolghanizadeh K , Hosseini M , Saghafiyazdi M . Effect of freezing temperature and number of freeze–thaw cycles on mode I and mode II fracture toughness of sandstone. Theor Appl Fract Mech. 2020; 105: 102428. doi:10.1016/j.tafmec.2019.102428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Amirkiyaei V , Ghasemi E , Faramarzi L . Estimating uniaxial compressive strength of carbonate building stones based on some intact stone properties after deterioration by freeze–thaw. Environ Earth Sci. 2021; 80( 9): 352. doi:10.1007/s12665-021-09658-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Yang X , Jiang A , Zheng S . Analysis of the effect of freeze-thaw cycles and creep characteristics on slope stability. Arab J Geosci. 2021; 14( 11): 1033. doi:10.1007/s12517-021-07290-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Ji H , Wang LY , Wu ZX , Tu DM ,. Investigation on 3D modelling and seepage simulation of stochastic fractures for jointed rock masses. Chin J Comput Mech. 2024; 41( 4): 718– 25. (In Chinese). doi:10.7511/jslx20230504002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Lin ZB , Li YH , Lin PZ , Zhang BY , Yang DF . Study on the mechanism of water inrush disasters in overlying karst tunnels under damage-seepage coupling. J Henan Polytech Univ Nat Sci. 2025; 44( 2): 154– 63. (In Chinese). doi:10.16186/j.cnki.1673-9787.2023090052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liu X , Zhang J , Zhou X , Liu Y , Wang Y , Luo X . Damage-seepage evolution mechanism of fractured rock masses considering the influence of lateral stress on fracture deformation under loading and unloading process. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2024; 57( 12): 10973– 99. doi:10.1007/s00603-024-04024-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zheng MH , Wang DL , He ZY , Wang H , Cao HH , Zhang ZM , et al. Analysis of main controlling factors of single fracture erosion damage of rock mass under particle migration. Nonferrous Metall Equip. 2024; 38( 6): 36– 42. (In Chinese). doi:10.19611/j.cnki.cn11-2919/tg.2024.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Cao Z , Wang P , Li Z , Du F . Migration mechanism of grouting slurry and permeability reduction in mining fractured rock mass. Sci Rep. 2024; 14( 1): 3446. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-51557-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Gan L , Liu Y , Zhang Z , Shen Z , Ma H . Roughness characterization of rock fracture and its influence on fractureseepage characteristics. Rock Soil Mech. 2023; 44( 6): 1585– 92. (In Chinese). doi:10.16285/j.rsm.2022.1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Li Z , Zhou Z , Gao C , Zhang D , Bai S . Seepage Simulation method of fractured rock mass based oncoupling of peridynamics and finite volume method. J Tongji Univ Nat Sci. 2022; 50( 9): 1251– 63. (In Chinese). doi:10.11908/j.issn.0253-374x.22076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Qi Y , Chen X , Zhao Q , Luo X , Feng C . Seismic wave modeling of fluid-saturated fractured porous rock: including fluid pressure diffusion effects of discretely distributed large-scale fractures. Solid Earth. 2024; 15( 4): 535– 54. doi:10.5194/se-15-535-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Mitskovets IA , Khokhlov NI . Simulation of propagation of dynamic perturbations in porous media by the grid-characteristic method with explicit description of heterogeneities. Comput Math Math Phys. 2023; 63( 10): 1904– 17. doi:10.1134/S0965542523100093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Tran KM , Bui HH , Nguyen GD . DEM modelling of unsaturated seepage flows through porous media. Comput Part Mech. 2022; 9( 1): 135– 52. doi:10.1007/s40571-021-00398-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Schneider M , Gläser D , Weishaupt K , Coltman E , Flemisch B , Helmig R . Coupling staggered-grid and vertex-centered finite-volume methods for coupled porous-medium free-flow problems. J Comput Phys. 2023; 482: 112042. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2023.112042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Legostaev DY , Rodionov SP . Numerical investigation of the structure of fracture network impact on the fluid flow through a poroelastic medium. Fluid Dyn. 2023; 58( 4): 598– 611. doi:10.1134/S001546282360027X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Rutqvist J , Wu YS , Tsang CF , Bodvarsson G . A modeling approach for analysis of coupled multiphase fluid flow, heat transfer, and deformation in fractured porous rock. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2002; 39( 4): 429– 42. doi:10.1016/S1365-1609(02)00022-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sarkhosh P , Salama A , Jin YC . Implicit finite-volume scheme to solve coupled saint-venant and darcy–forchheimer equations for modeling flow through porous structures. Water Resour Manag. 2021; 35( 13): 4495– 517. doi:10.1007/s11269-021-02963-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Wang L , Wang Y , Vuik C , Hajibeygi H . Accurate modeling and simulation of seepage in 3D heterogeneous fractured porous media with complex structures. Comput Geotech. 2022; 150: 104923. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.104923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Khoei AR , Saeedmonir S , Misaghi Bonabi A . Computational homogenization of fully coupled hydro-mechanical analysis of micro-fractured porous media. Comput Geotech. 2023; 154: 105121. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2022.105121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Tran M , Jha B . Effect of poroelastic coupling and fracture dynamics on solute transport and geomechanical stability. Water Resour Res. 2021; 57( 10): e2021WR029584. doi:10.1029/2021WR029584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wan R , Eghbalian M . Multiscale model for damage-fluid flow in fractured porous media. Int J Mult Comp Eng. 2016; 14( 4): 367– 87. doi:10.1615/intjmultcompeng.2016016951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Zhang H , Mobasher ME , Shen Z , Waisman H . A unified non-local damage model for hydraulic fracture in porous media. Acta Geotech. 2023; 18( 10): 5083– 121. doi:10.1007/s11440-023-01873-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Eghbalian M , Pouragha M , Wan R . A three-dimensional multiscale damage-poroelasticity model for fractured porous media. Int J Numer Anal Meth Geomech. 2021; 45( 5): 585– 630. doi:10.1002/nag.3170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Shojaei A , Dahi Taleghani A , Li G . A continuum damage failure model for hydraulic fracturing of porous rocks. Int J Plast. 2014; 59: 199– 212. doi:10.1016/j.ijplas.2014.03.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Chen D , Wang L , Sun C , Ao Y . Particle flow study on the microscale effects and damage evolution of sandstone creep. Comput Geotech. 2023; 161: 105606. doi:10.1016/j.compgeo.2023.105606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Alber M , Fritschen R , Bischoff M , Meier T . Rock mechanical investigations of seismic events in a deep longwall coal mine. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2009; 46( 2): 408– 20. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2008.07.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Hofmann GF , Scheepers LJ . Simulating fault slip areas of mining induced seismic tremors using static boundary element numerical modelling. Min Technol. 2011; 120( 1): 53– 64. doi:10.1179/037178411X12942393517291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Li Z , Wang C , Shan R , Yuan H , Zhao Y , Wei Y . Study on the influence of the fault dip angle on the stress evolution and slip risk of normal faults in mining. Bull Eng Geol Environ. 2021; 80( 5): 3537– 51. doi:10.1007/s10064-021-02149-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Sun WB , Hao JB , Dai XZ , Kong LJ . Response mechanism characteristics of mining-induced fault activation. Coal Geol Explor. 2024; 52( 4): 12– 20. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

57. Shabanimashcool M , Li CC . Numerical modelling of longwall mining and stability analysis of the gates in a coal mine. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2012; 51: 24– 34. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2012.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Sainoki A , Mitri HS . Effect of fault-slip source mechanism on seismic source parameters. Arab J Geosci. 2015; 9( 1): 69. doi:10.1007/s12517-015-2027-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Yavuz H . An estimation method for cover pressure re-establishment distance and pressure distribution in the goaf of longwall coal mines. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2004; 41( 2): 193– 205. doi:10.1016/S1365-1609(03)00082-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Ziegler M , Reiter K , Heidbach O , Zang A , Kwiatek G , Stromeyer D , et al. Mining-induced stress transfer and its relation to a Mw 1.9 seismic event in an ultra-deep South African gold mine. Pure Appl Geophys. 2015; 172( 10): 2557– 70. doi:10.1007/s00024-015-1033-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Díaz Aguado MB , González C . Influence of the stress state in a coal bump-prone deep coalbed: a case study. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2009; 46( 2): 333– 45. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2008.07.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Nevitt JM , Pollard DD . Impacts of off-fault plasticity on fault slip and interaction at the base of the seismogenic zone. Geophys Res Lett. 2017; 44( 4): 1714– 23. doi:10.1002/2016GL071688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Marcak H , Mutke G . Seismic activation of tectonic stresses by mining. J Seismol. 2013; 17( 4): 1139– 48. doi:10.1007/s10950-013-9382-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Sainoki A , Mitri HS . Dynamic behaviour of mining-induced fault slip. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2014; 66: 19– 29. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2013.12.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Cao MH , Yang SQ , Du SG , Li Y , Wang SS . Study on fault-slip process and seismic mechanism under dynamic loading of hard roof fracture disturbance. Eng Fail Anal. 2024; 163: 108598. doi:10.1016/j.engfailanal.2024.108598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Liu Y , Meng X , Cheng X , Zhao G , Gu Q , Wang Y , et al. Simulation study on fault activation response under mining disturbance of hanging-wall and foot-wall of reverse fault. J Saf Sci Technol. 2024; 20( 8): 33– 41. (In Chinese). doi:10.11731/j.issn.1673-193x.2024.08.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Zhang Y , Zhang Z , Xiao J , Li Y , Yu Q . Study on mining water inrush mechanism of buried fault undercoal seam floor above confined water body. Coal Sci Technol. 2023; 51( 2): 283– 91. (In Chinese). doi:10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2022-1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Mironenko V , Strelsky F . Hydrogeomechanical problems in mining. Mine Water Environ. 1993; 12( 1): 35– 40. doi:10.1007/BF02914797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Motyka J , Pulido-Bosch A . Karstic phenomena in calcareous-dolomitic rocks and their influence over the inrushes of water in lead-zinc mines in Olkusz region (South of Poland). Int J Mine Water. 1985; 4( 2): 1– 11. doi:10.1007/BF02504832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Kuscer D . Hydrological regime of the water inrush into the kotredez coal mine (Slovenia, Yugoslavia). Mine Water Environ. 1991; 10( 1): 93– 101. doi:10.1007/BF02914811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. LaMoreaux JW , Qiang W , Zhou W . New development in theory and practice in mine water control in China. Carbonates Evaporites. 2014; 29( 2): 141– 5. doi:10.1007/s13146-014-0204-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Singh T , Singh B , Model S . Study of coal mining under river bed in India. Int J Mine Water. 1985; 4: 1– 9. doi:10.1007/BF02551565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Mokhov AV . Fissuring due to inundation of coal mines and its hydrodynamic implications. Dokl Earth Sci. 2007; 414( 1): 519– 21. doi:10.1134/s1028334x0704006x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Faria Santos C , Bieniawski ZT . Floor design in underground coal mines. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 1989; 22( 4): 249– 71. doi:10.1007/BF01262282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Sammarco O . Inrush prevention in an underground mine. Int J Mine Water. 1988; 7( 4): 43– 52. doi:10.1007/BF02505391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Yao B , Li S , Du F , Li Z , Zhang B , Cao Z , et al. Mechanical model of deformation-seepage-erosion for Karst collapsecolumn water inrush and its application. J China Coal Soc. 2024; 49( 5): 2212– 21. (In Chinese). doi:10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2023.0394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Bai J , Duan S , Liu R , Xin L , Tian J , Zhang Q , et al. Evolution of delayed water inrush in fault fracture zone considering time effect. Arab J Geosci. 2021; 14( 11): 1001. doi:10.1007/s12517-021-06469-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Li H , Zhu KP , Guo GQ , Zhou Y , Kang ZQ . A simulation study of mechanisms behind water inrush from fault-bearing floors of ultra-thick coal seams under loading and unloading at significantly variable amplitude. Coal Geol Explor. 2024; 52( 5): 118– 28. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

79. Li A , Sun JX , Zhang WZ , Zhang Z , Yang YX , Wang WD , et al. Fracture mechanical criteria and simulation of floors with Y-shaped branches of major faults in coal mines. Coal Geol Explor. 2024; 52( 9): 92– 105. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

80. Zhou Q , Herrera-Herbert J , Hidalgo A . Predicting the risk of fault-induced water inrush using the adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system. Minerals. 2017; 7( 4): 55. doi:10.3390/min7040055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Al-Muqdadi SW , Merkel BJ . Interpretation of groundwater flow into fractured aquifer. Int J Geosci. 2012; 3( 2): 357– 64. doi:10.4236/ijg.2012.32039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Rutqvist J , Rinaldi AP , Cappa F , Moridis GJ . Modeling of fault activation and seismicity by injection directly into a fault zone associated with hydraulic fracturing of shale-gas reservoirs. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2015; 127: 377– 86. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2015.01.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Islam MR , Shinjo R . Mining-induced fault reactivation associated with the main conveyor belt roadway and safety of the Barapukuria Coal Mine in Bangladesh: constraints from BEM simulations. Int J Coal Geol. 2009; 79( 4): 115– 30. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2009.06.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Souley M , Homand F , Pepa S , Hoxha D . Damage-induced permeability changes in granite: a case example at the URL in Canada. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2001; 38( 2): 297– 310. doi:10.1016/S1365-1609(01)00002-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Wang JA , Park HD . Fluid permeability of sedimentary rocks in a complete stress–strain process. Eng Geol. 2002; 63( 3–4): 291– 300. doi:10.1016/S0013-7952(01)00088-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Zhang Y . Mechanism of water inrush of a deep mining floor based on coupled mining pressure and confined pressure. Mine Water Environ. 2021; 40( 2): 366– 77. doi:10.1007/s10230-020-00743-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Terzaghi K . Die berechnung der durchlassigkeitzifer des tones aus dem verlauf der hydrodynamischen spannungserscheinungen. Math-Naturwissenschaftliche. 1923; 132: 125– 38. (In German). [Google Scholar]

88. Biot MA . General theory of three-dimensional consolidation. J Appl Phys. 1941; 12( 2): 155– 64. doi:10.1063/1.1712886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Ma D , Duan H , Zhang J , Bai H . A state-of-the-art review on rock seepage mechanism of water inrush disaster in coal mines. Int J Coal Sci Technol. 2022; 9( 1): 50. doi:10.1007/s40789-022-00525-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Li Q , Ma D , Zhang JX , Liu Y , Hou WT . Mining-induced shear deformation and permeability evolution law of crushed rock mass in fault zone. Coal Geol Explor. 2023; 51( 8): 150– 60. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

91. Jia Y . Study on variable-mass seepage laws in fractured rock masses based on catastrophe theory [ master’s thesis]. Jiaozuo, China: Henan Polytechnic University; 2025. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

92. Zeng Y , Zhu H , Wu Q , Wang H , Fu X , Wang T , et al. Disaster-causing mechanism and prevention and control vision orientation of different types of coal seam floor water disasters in China. J China Coal Soc. 2025; 50( 2): 1066– 93. (In Chinese). doi:10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.XH24.1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Carcione JM , Currenti G , Johann L , Shapiro S . Modeling fluid injection induced microseismicity in shales. J Geophys Eng. 2018; 15( 1): 234– 48. doi:10.1088/1742-2140/aa8a27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Gustafson G , Claesson J , Fransson Å . Steering parameters for rock grouting. J Appl Math. 2013; 2013( 1): 269594. doi:10.1155/2013/269594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Draganović A , Stille H . Filtration of cement-based grouts measured using a long slot. Tunn Undergr Space Technol. 2014; 43: 101– 12. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2014.04.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Zhang E , Xu Y , Fei Y , Shen X , Zhao L , Huang L . Influence of the dominant fracture and slurry viscosity on the slurry diffusion law in fractured aquifers. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2021; 141: 104731. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2021.104731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Saada Z , Canou J , Dormieux L , Dupla JC . Evaluation of elementary filtration properties of a cement grout injected in a sand. Can Geotech J. 2006; 43( 12): 1273– 89. doi:10.1139/t06-082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Li A , Ji BN , Ma Q , Liu C , Wang F , Ma L , et al. Design of longwall coal pillar for the prevention of water inrush from the seam floor with through fault. Geofluids. 2021; 2021( 1): 5536235. doi:10.1155/2021/5536235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Kou T , Wen S , Mu W , Xu N , Gao Z , Lin Z , et al. Slurry leakage channel detection and slurry transport process simulation for overburden bed separation grouting project: a case study from the Wuyang coal mine, northern China. Water. 2023; 15( 5): 996. doi:10.3390/w15050996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Hagiwara T . Determination of dip and anisotropy from transient triaxial induction measurements. Geophysics. 2012; 77( 4): D105– 12. doi:10.1190/geo2011-0503.1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Liu Q , Lei G , Lu C , Peng X , Zhang J , Wang J , et al. Experimental study of grouting reinforcement influence on mechanical properties of rock fracture. Chin J Rock Mech Eng. 2017; 36( S1): 3140– 7. (In Chinese). doi:10.13722/j.cnki.jrme.2016.0459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Zhang WQ , Zhu XX , Li S , Liu Y , Wu XN , Chen B . Experimental study on performance of rubber-fly ash-based mine floor fissure grouting material. Coal Sci Technol. 2023; 51( 5): 1– 10. (In Chinese). doi:10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2022-1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Ge M . Efficient mine microseismic monitoring. Int J Coal Geol. 2005; 64( 1–2): 44– 56. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2005.03.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Harteis S , Dolinar D . Water and slurry bulkheads inunderground coal mines: design, monitoring and safety concerns. Min Eng. 2006; 58( 12): 41– 7. [Google Scholar]

105. Khan M , He X , Song D , Tian X , Li Z , Xue Y , et al. Extracting and predicting rock mechanical behavior based on microseismic spatio-temporal response in an ultra-thick coal seam mine. Rock Mech Rock Eng. 2023; 56( 5): 3725– 54. doi:10.1007/s00603-023-03247-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Robinson DA , Binley A , Crook N , Day-Lewis FD , Ferré TPA , Grauch VJS , et al. Advancing process-based watershed hydrological research using near-surface geophysics: a vision for, and review of, electrical and magnetic geophysical methods. Hydrol Process. 2008; 22( 18): 3604– 35. doi:10.1002/hyp.6963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Lian H , Xu B , Tian Z , Liu D , Yang Y , Pan G , et al. Design and implementation of mine water hazard monitoring and earlywarning platform. Coal Geol Explor. 2021; 49( 1): 198– 207. (In Chinese). doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-1986.2021.01.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Dong Y , Meng X , Gao Z . Study on design of coal pillar rational width for prevent water-inrush under influence of fault. Coal Sci Technol. 2014; 42( S1): 241– 3. (In Chinese). doi:10.13199/j.cnki.cst.2014.s1.090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Yu XG , Luo WN , Xu DJ , Xiang JT , Zhang N . Optimised calculation of retention of waterproof coal (rock) pillars in coal seams containing water-conducting faults. J China Coal Soc. 2025; 50( 8): 3857– 67. (In Chinese). doi:10.13225/j.cnki.jccs.2024.0975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Zhou C , Qiao Y , Zhang H . Study on reasonable size of fault waterproof coal pillar considering fault permeability. Coal Technol. 2025; 44( 02): 86– 90. (In Chinese). doi:10.13301/j.cnki.ct.2025.02.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

111. Caselle C , Bonetto S , Comina C , Stocco S . GPR surveys for the prevention of karst risk in underground gypsum quarries. Tunn Undergr Space Technol. 2020; 95: 103137. doi:10.1016/j.tust.2019.103137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

112. Mahmoodzadeh A , Ibrahim H , Flaih L , Alanazi A , Alqahtani A , Alsubai S , et al. A gene expression programming-based model to predict water inflow into tunnels. Geomech Eng. 2024; 37( 1): 65– 72. doi:10.12989/gae.2024.37.1.065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]