Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

3D Printing of Organic and Biological Materials

ROFEL Shri G.M. Bilakhia College of Pharmacy, Rajju Shroff ROFEL University, Vapi, 396191, India

* Corresponding Author: Komal Parmar. Email:

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(12), 2855-2903. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.069428

Received 23 June 2025; Accepted 26 December 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

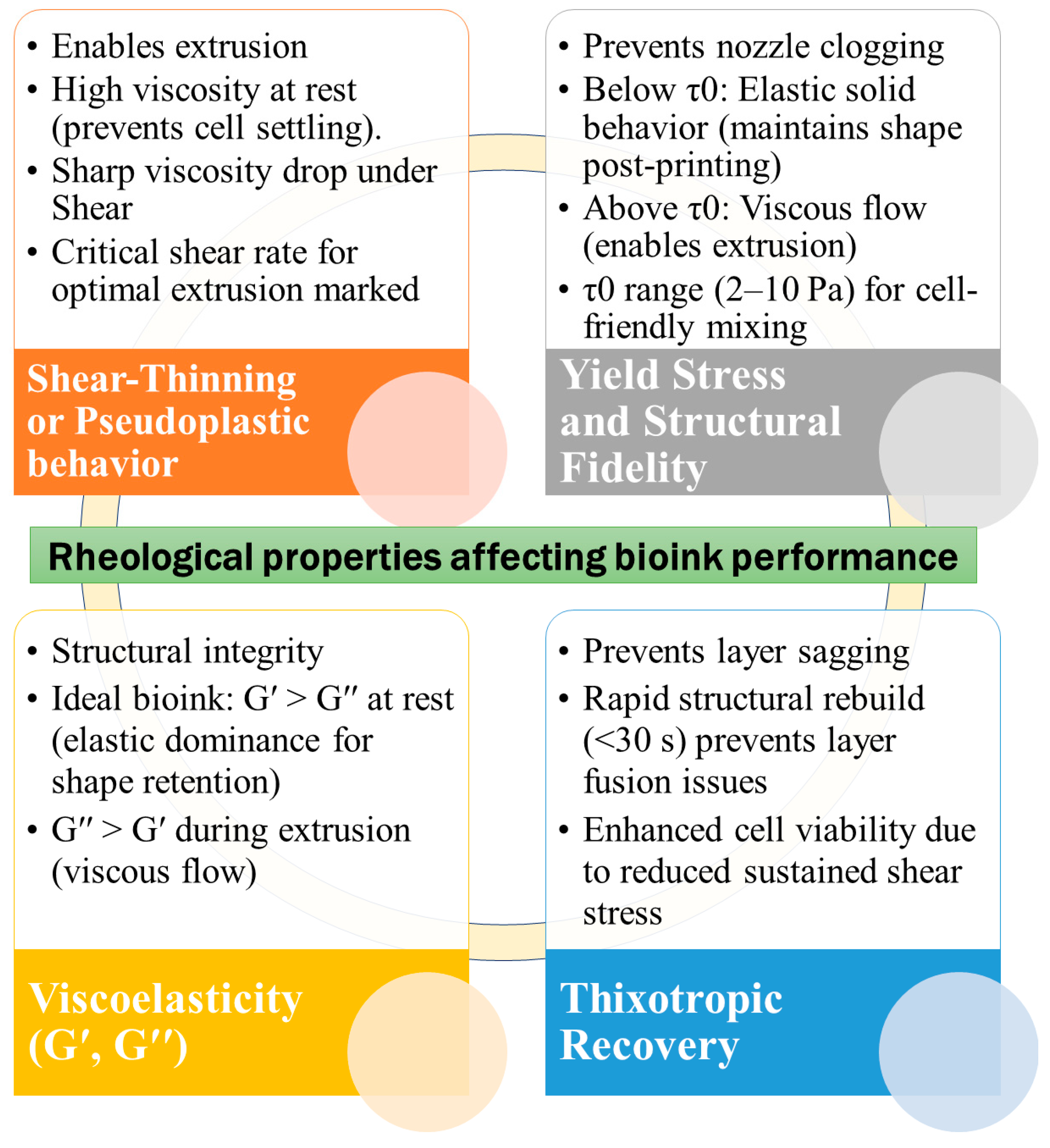

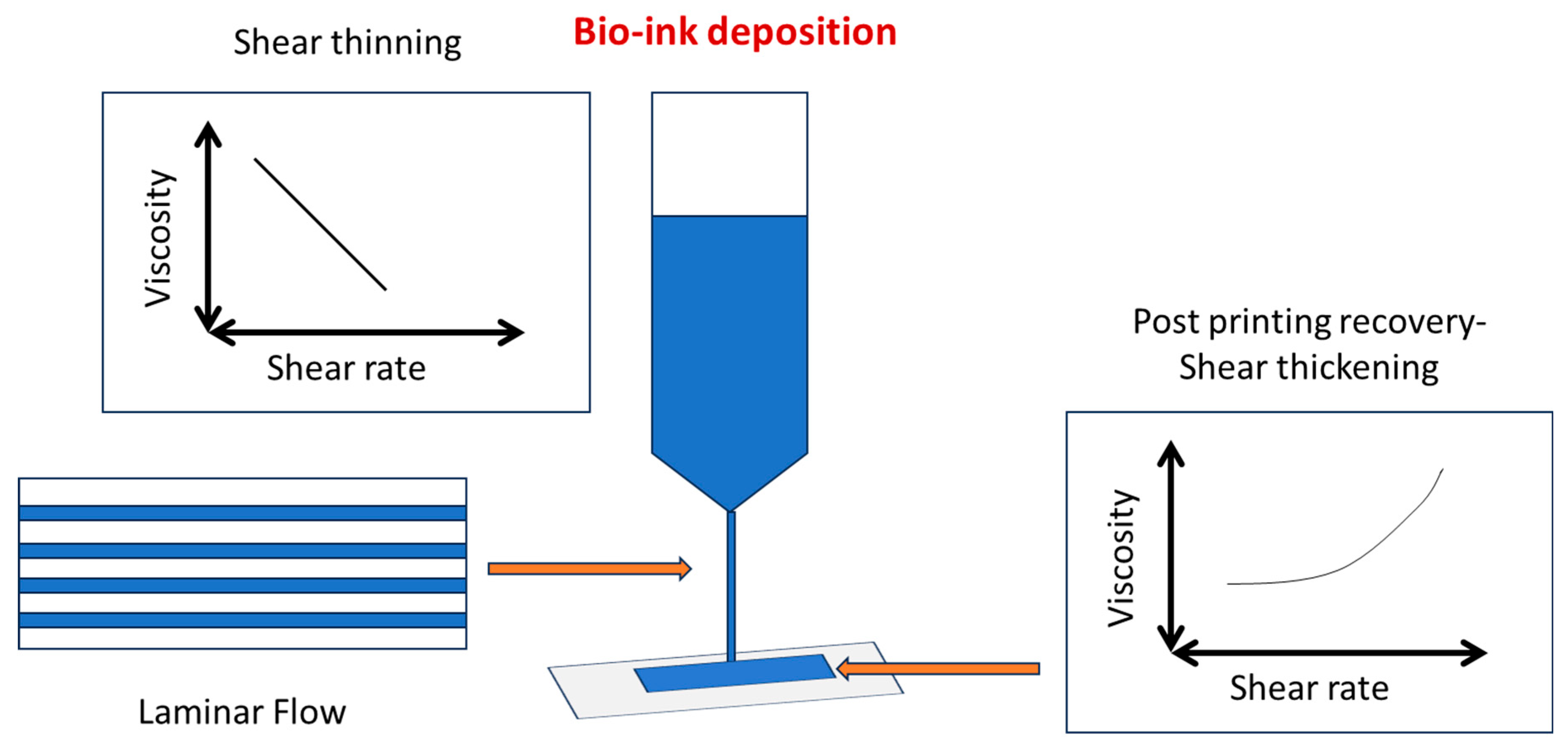

Tissue engineering has advanced remarkably in developing functional tissue substitutes for pharmaceutical and regenerative applications. Among emerging technologies, three-dimensional (3D) printing, or additive manufacturing, enables precise fabrication of biocompatible materials, living cells, and scaffolds into complex, viable constructs. Within regenerative medicine, 3D bioprinting addresses the growing demand for transplantable tissues and organs by assembling biological materials that replicate native architectures. This paper reviews biomaterials used in 3D bioprinting, emphasizing how their rheological behavior, particularly viscoelasticity and thixotropy, governs printability, structural fidelity, and cellular viability. The advantages and limitations of natural, synthetic, and composite bioinks are analyzed in relation to their mechanical performance and flow properties. In addition, common 3D bioprinting techniques such as extrusion, inkjet, and laser-assisted methods are outlined with reference to their compatibility with various material systems. Recent applications in bone, cartilage, vascular, skin, neural, cardiac, hepatic, and pulmonary tissue engineering are briefly summarized.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The advent of the printing press altered human history. The revolutionary technique of printing text and images had a global influence, serving as a medium for education, religion, politics, language, and culture [1]. Numerous developments since then have improved printing processes much further. The consumer market was transformed, for instance, by the advent of dot matrix printers, which reduced costs and time by enabling desktop publishing and on-demand printing via a computer connected to a printer as a peripheral device. The general public now has more access to education, scientific research, and the arts due to personalized printing.

In recent years, additive manufacturing (AM) has gained significant attention. Additive Manufacturing (AM) is recognized as a noteworthy sustainable manufacturing technology [2]. Numerous industries, including engineering, architecture, medicine, industrial design, construction, and many more, have discovered broad uses for 3D printing, the process of producing a three-dimensional product from a computer-driven digital model [3]. Three-dimensional (3D) printing, sometimes referred to as additive manufacturing (AM), layered manufacturing, rapid prototyping (RP), or solid freeform fabrication, is the process of directly fabricating parts one layer at a time using digital data from a computer-aided design (CAD) file without the need for part-specific tools. In 3D printing, CAD models of the objects that need to be created are first sliced in a virtual environment to generate a stack of two-dimensional (2D) slices. Based on the 2D slice information, a 3D printer then constructs the components one layer at a time, stacking and combining subsequent layers to create the finished 3D product [4,5]. Unlike mass production, it enables individuals to make personalized things on demand at cost-effective pricing. The rapid spread of this technology can be attributed to cost reductions that make it advantageous for producing certain product categories, such as those made in limited quantities, require personalization, or are not possible to manufacture using traditional manufacturing methods. Technology has become widely used in several industries, leading to the third industrial revolution [6]. Applications for 3D printing are widespread in a wide range of industries, including the food industry, biotechnology, biomedical, and analytical fields. It has been reported that 3D printing can be used to visualize molecules and proteins, as well as to teach about orbitals and surfaces [7].

Bioprinting is made feasible by the capability of a 3D printer to dispense biological materials. Bioprinting is described as: “the utilization of material transfer techniques for designing and assembling biological relevant materials, molecules, cells, tissues, and biodegradable biomaterials—using predefined architecture to execute one or more biological functions” [8,9]. Biomaterials and living cells can typically be positioned layer by layer to accomplish bio-printing. 3D tissue architectures, including skin, cartilage, tendons, heart muscle, and bone, may be created because of the functional materials’ exquisite spatial control. The first step in the procedure is choosing the appropriate cells for the tissue [10]. Patient-specific treatments are crucial in the biomedical industry to enhance biological repair, replacement, and regeneration [9]. With programmable micro-architecture, 3D printers may create custom structures for each patient using clinical image data from X-rays, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or computerized tomography (CT) scans [11,12]. For instance, utilizing 3D printing and CT scans of the patient’s airway, medical professionals recently designed a biodegradable tracheal splint for a baby. Additional examples include medicine delivery implants, customized medications, and printed artificial ears made especially for individuals [13,14]. 3D printing is a cost-effective and time-saving alternative to traditional production methods for prosthetic implants [15].

Printing scaffolds, which serve as supports for developing cells, is one technique of bioprinting. This enables the precise placement of biomaterials, live cells, growth agents, and other biological elements for generating complex 3D living tissue [16]. Scaffolds are essential for tissue engineering as they offer the following: extracellular matrix production and remodeling space, structure for cell infiltration and proliferation, biochemical signals to guide cell activity, and physical connections for wounded tissue. Designing scaffold architecture at the macro, micro, and nano levels is crucial for optimal structural, nutrient transport, and cell-matrix interaction conditions. The macroarchitecture refers to the device’s overall form, which might be complicated due to patient and organ specialization and anatomical factors. The tissue architecture (including pore size, shape, porosity, spatial distribution, and pore connections) is reflected in the microarchitecture. Nanoarchitecture involves surface modification, such as biomolecule attachment, to promote cell adhesion, proliferation, and differentiation [17].

While an ideal scaffold should address all of these criteria, difficulties persist with biomaterial selection and 3D shape specificity. Commonly utilized biomaterials include synthetic and natural polymers, ceramics, metals and carbon based nanomaterials. Each biomaterial has unique material and mechanical qualities, manufacturing techniques, chemical properties, cell-material interactions, and approval from the FDA [18]. Bioprinting technologies have made significant contributions to biomedical research, although they are still in their early stages of development [19,20]. Developing scaffolds for high load bearing applications presents challenges due to the limited biodegradability and bioactivity of current printable materials like ceramics and metals, as well as the potential for inflammatory responses from host tissues. Furthermore, metals and ceramics cannot be functionalized with drugs or biomolecules.

Using organic materials in the form of powders can help produce scaffolds with acceptable mechanical characteristics, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and bioactivity [21,22]. Polymers (macromolecules) are the major scaffolding materials used in a variety of tissue engineering applications, including bone and mineralized tissues [23,24]. BioPolymers are a remarkable choice for tissue engineering applications, thanks to their adaptability and the extensive variety of mechanical, chemical, and physical characteristics they can deliver. These materials demonstrate high biocompatibility, are lightweight, inert, and are resistant to biochemical assaults and are easily available at affordable prices and can be rapidly shaped into the desired forms. Polymeric biomaterials may originate from both natural and synthetic polymers, each having its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Natural polymers include proteins such as collagen, elastin, keratin, gelatin, and fibrin, along with carbohydrates like chitin, cellulose, starch, alginate, and hyaluronic acid; synthetic polymers include polyesters such as poly ε-caprolactone, polylactic acid, and polyglycolic acid [25,26].

Even though three-dimensional (3D) printing was initially introduced in the late 1980s using a process known as stereo lithography, its importance didn’t become apparent until the turn of the twenty-first century [27]. Stereolithography (SLA), the earliest additive manufacturing (AM) technique, was first invented in 1981 by Dr. Hideo Kodama. In contrast to holographic methods, he considered it a quick and inexpensive way to recreate models in 3D space [28]. Several 3D printing techniques have been explored since the first stereolithographic 3D printer was invented in 1986 by Chuck Hull, the most common being fused deposition modeling (FDM), stereolithography (SLA), selective laser sintering (SLS), selective laser melting (SLM), electronic beam melting (EBM), digital light processing (DLP), and laminated object manufacturing (LOM). Their goal was to make it easier to quickly prototype plastic components [29]. SLA has greatly expanded beyond its initial applications in modeling and prototyping with the invention of several techniques, and it can now be used to build intricate and custom-designed geometries. The material is no longer confined to traditional polymers, but may also be used to generate composites [30], metallic [31], and ceramic [32] specimens. However, SLA is currently only being used to build one material at a time, and when compared to other AM technologies, typical SLA techniques demonstrate improved resolution and surface characteristics, but at a higher cost and slower printing durations [33].

The actual printing of the bioink utilizing the bio-printers is known as the processing stage. In order to generate the required biological structures, the processing step involves the development of bioink, clinical cell sorters (like Celution and Cytori Therapeutics), cell propagation bioreactors (like Aastrom Bioscience), and cell differentiators.

During the post-processing phase, the printed construct is converted into a functioning tissue-engineered organ that may be surgically implanted. Cell encapsulators, perfusion bioreactors, and a collection of bio-monitoring devices may also be employed in the postprocessing phase [34].

The aim of this review is to provide a comprehensive overview of the current state of bioink technology. The review covers both natural and synthetic biomaterials, employed alone or in combination. This paper will also review sophisticated techniques for 3D printing used for developing tissue engineering scaffolds, with a focus on their capacity to design cells and various materials along complex 3D gradients.

2 Characteristics of Biomaterials and Biomaterial Scaffolds

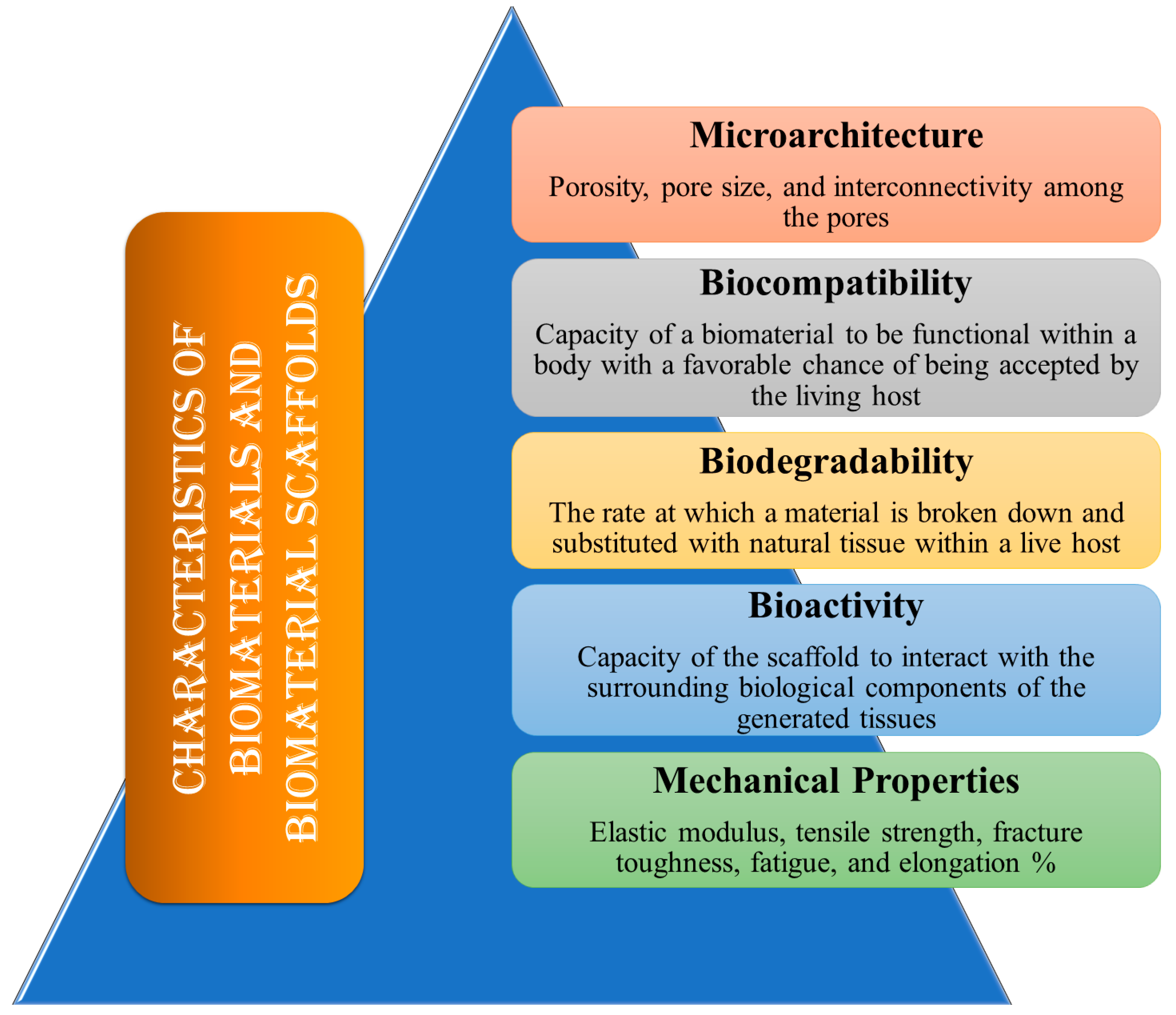

Biomaterials are natural or synthetic materials that repair injured body components and interact with biological systems. Innovative biomedical devices to enhance human life have been developed during the past century with the advent of metallic, ceramic, and polymeric biomaterials [35]. To be effective, these substances must not be harmful and must be compatible with the tissues of the body. Three-dimensional (3D) porous biomaterials known as scaffolds offer an ideal platform for cells to regenerate and repair tissues and organs [36]. In addition to encouraging cell attachment, proliferation, extracellular matrix regeneration, and the repair of nerves, muscles, and bones, it acts as a template for the rebuilding of tissue defects. Furthermore, as a mechanical barrier against the invading native tissues, scaffolds can carry bioactive substances, including medications, inhibitors, and cytokines, which might impede tissue regeneration and repair [37]. The success of generating biomedical scaffolds depends on the choice of biomaterials. The scaffolds must have comparable properties that match the application at hand and be specifically built to perform specific functions. These characteristics fall under the categories of mechanical qualities, biodegradability, biocompatibility, and structural architecture as displayed in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: The ideal features of biomaterials and biomaterial scaffolds.

Porosity, pore size, and interconnectivity among the pores are all components of the scaffold’s microarchitecture. Primarily, the size of the pores must be adequate to facilitate cell motility and scaffold attachment. This provides adequate vascularization and infiltration, as well as the efficient movement of waste products and nutrients into and out of the cells and tissues. For in vitro applications, a smaller pore size of 75 to 100 μm is recommended, while in vivo, the maximum pore size should be between 200 and 500 μm to achieve the most effective tissue penetration and vascularization [38,39]. Additionally, to augment the scaffold surface area that supports cell adhesion, a network of interconnected pores is required. Greater porosity aids in the integration of the designed tissues with the natural tissues by improving cell-to-cell connections [40].

The capacity of a biomaterial to be functional within a body with a favorable chance of being accepted by the living host is the single most significant characteristic that distinguishes it from a normal material. The ability of a biomaterial to work in conjunction with a medical therapy, producing the best possible cellular and tissue response in the specified anatomical site, optimizing the effectiveness of the medical treatment, and avoiding any undesirable local or systemic effects on the recipient is termed biocompatibility [41]. Biocompatibility refers to a material that is safe for humans and has the necessary properties for medical applications, such as mechanical properties and degradability, while remaining non-toxic and non-carcinogenic. The scaffold must exhibit a high degree of biocompatibility to facilitate cell adhesion and proliferation, while also minimizing chronic immune responses to avert significant inflammatory reactions that could hinder healing or lead to rejection within the body [42,43].

Biodegradability refers to the rate at which a material is broken down and substituted with natural tissue within a live host. By-products are absorbed and released by the body’s metabolic processes [44]. Scaffolds should be gradually broken down chemically or enzymatically when transplanted into living organisms, since they serve only as a transitory platform for growing cells or tissues. Biodegradability is the rate at which the scaffold materials decompose. The scaffold’s rate of biodegradation needs to be proportionate to the pace of tissue regeneration or new bone development. Through a process known as “creeping substitution,” newly generated tissues will eventually replace the biomaterial scaffolds after they have been effectively integrated with the host bone. The mechanical properties and structural integrity of a biomaterial during its entire lifespan are also described by its biodegradability, which in turn indicates the kind of application for which the biomaterial is appropriate [45].

Biomaterial scaffolds must possess a certain level of mechanical integrity in relation to their intended use. Preferably, structures ought to possess the same consistency as the anatomical location where they are situated into, yet sufficiently robust to be handled and inserted [46]. There are differences in the mechanical characteristics of tissue. In addition to offering form stability and structural support, it also reduces the chance of stress shielding, implant-related osteopenia, and future refracture. In furtherance of necessitating the appropriate mechanical characteristics to support heavy load bearing applications, these scaffolds also must stay in perform until the healing process has been completed [46,47]. Elastic modulus, tensile strength, fracture toughness, fatigue, and elongation % are a few examples of mechanical characteristics [48].

The capacity of the scaffold to interact with the surrounding biological components of the generated tissues is known as scaffold bioactivity. Bioactive scaffolds are intended to promote appropriate cell migration or differentiation, tissue regeneration or neoformation, and host integration, thereby preventing processes like scarring, in contrast to conventional passive biomaterials, which typically have minimal or no interactions with the environment [39]. Scaffolds can be affixed to physical markers like topography to improve cell morphology and alignment, or they can be affixed to cell-adhesive ligands to encourage cell adhesion. Furthermore, to promote tissue regeneration, bioactive scaffolds may act as a reservoir or transporter for growth-stimulating stimuli like GFs [49].

3 Materials/Biomaterials Utilized for 3D Bioprinting

Current scaffold research confronts the problem of developing materials with good mechanical integrity for high load bearing applications while preserving optimal levels of biodegradability, biocompatibility, and bioactivity. Scaffold material selection should be based on the patient’s condition. Those with cancer or osteoporosis often experience diminished bone metabolism, thus it is essential that the scaffold material is not resorbable. Scaffolds are typically constructed from four categories of biomaterials: polymers, bio-ceramics, metals, and carbon nanomaterials. These scaffolds can incorporate various biomaterials owing to their distinct advantages and disadvantages. Currently, carbon-based nanomaterials, bioceramics, biodegradable metals, as well as both natural and synthetic polymers, among other materials, are utilized in the development of scaffolds [50].

Polymers are among the most often utilized materials for bioink. Because of their affordable cost, biocompatibility, degradation, and safe processing, polymer bioinks are employed in bioprinting. The capacity of polymer bioinks to alter shape is one of their additional benefits. For instance, they can be utilized as powders for laser bioprinting or as filaments for fused-deposition modeling. Polymeric biomaterials, which are essential components in many biomedical applications, come from two sources: naturally occurring polymers and synthetically engineered polymers. Each category has a distinctive combination of benefits and drawbacks that determine its applicability for various applications [25]. Artificial organs and blood arteries, breast implants, contact lenses, coatings for pharmaceutical tablets and capsules, joint replacements, cardiac assist devices, and external and internal ear repairs are a few biomedical applications employing polymers.

Natural polymers are non-toxic, biocompatible, attach well to cells, and promote proliferation and differentiation. However, they lack mechanical strength and are vulnerable to high temperatures [51]. Natural polymers are derived from natural sources. They fall into two categories: biomaterials based on proteins (which are naturally occurring polymers in the human body, like collagen, fibrin, and elastin) and biomaterials based on polysaccharides (which include silk, chitosan, alginate, and gelatin). Their properties are similar to those of soft tissues, demonstrating bioactivity, better cell growth and adhesion, and meeting biodegradability and biocompatibility requirements. They are also renowned for being widely accessible, environmentally safe, and adaptable to many uses. Nonetheless, natural sources suggest that a purification phase is necessary to prevent post-implantation foreign immune response. Furthermore, natural polymers usually exhibit low mechanical and physical stability, which restricts their use in the load-bearing orthopedic industry [24].

Collagen is a biocompatible polymer that has been extensively studied in bioprinting and, more specifically, tissue engineering. It is the predominant constituent of musculoskeletal tissue and constitutes the extracellular matrix of the majority of tissues. In reality, collagen is a naturally occurring triple-helical biocompatible protein. As a result, collagen scaffolds cause low immunological responses. In addition, collagen can promote cell proliferation, adhesion, and attachment. Although collagen type 1 has been widely employed in 3D printing, it has limits [52]. Three alpha helices combine to produce a triple helical shape in type I collagen, which is a member of the fibril-forming collagen group. Collagen molecules begin to organize themselves into fibrils at physiological temperatures (37°C and neutral pH), and the collagen solution turns into a hydrogel. Collagen bioink printability is dependent on the kinetics of this process; the faster the process, the more accurate the print [53].

Hyaluronic acid (HA) is a naturally occurring polymer found in the extracellular matrix of numerous tissues that is not immunogenic. It can control a wide range of cell behaviors and tissue functions and has outstanding hydrophilicity and biocompatibility [54,55]. However, HA by itself is not a good bioink for 3D bioprinting because of its low mechanical strength and rapid rate of breakdown. In addition, the concentration of the component may be changed to modify the hydrogel’s mechanical characteristics [56]. The researchers chemically modified HA and combined it with a printable hydrogel to create an HA-based hydrogel solution. In contrast to pure HA and/or other hydrogels, the solution demonstrated not only high biocompatibility and biodegradability, but also the mechanical strength and stiffness needed for bioink applications. HA-based hydrogel solutions are currently gaining popularity as bioinks, with promising future applications in the bioprinting of skin, nerve tissue, cartilage, and bone [57,58].

Fibrin is a vital protein for blood clotting and wound healing. These proteins play critical roles in neoplasia, cell-matrix interactions, and inflammatory responses. Fibrinogen, a glycoprotein generated by the liver, rises in response to trauma. Thrombin, a serine protease produced after arterial injury, hydrolyzes fibrinogen and polymerizes it into fibrin. Fibrin is a scaffolding material commonly utilized in tissue engineering, notably for vascular grafts. Fibrin gels (gelation time is rapid) provide desirable properties, including differentiation, biodegradability, promote cell proliferation, angiogenesis, biocompatibility, and regeneration of tissues. Additional benefits of fibrin include its superior mechanical qualities, heparin-binding domains with affinity for growth hormones, and binding sites for natural extracellular matrix proteins [59]. A fibrin-gelatin hybrid hydrogel was utilized as biopaper for skin bioprinting. Fibrin-factor XIII-hyaluronate hydrogel scaffolds were used in an in vitro study to encapsulate Schwann cells, potentially improving nerve regeneration and repair [60].

Chitosan, a polycationic biocompatible natural polymer, has certain distinct advantages for bioprinting applications. Solutions containing chitosan exhibit suitable viscosity profiles and maintain stability in physiological environments, making them suitable for use in bioprinting applications. Additionally, chitosan promotes healthy cell differentiation and proliferation. High vitality is demonstrated by cells grown on chitosan scaffolds. As a result, chitosan hydrogels and resins satisfy these criteria; moreover, chitosan hydrogels may be adjusted to effectively replicate the natural extracellular matrix (ECM) of tissues [61]. However, in tissue engineering, this natural polymer has demonstrated several limitations, such as poor mechanical strength and a sluggish gelation rate. It is important to remember that a bioink must be a liquid or semi-solid substance that may be crosslinked chemically or physically in order to have mechanical strength and physical stability. Therefore, to increase the likelihood of stronger crosslinking, chitosan-based biomaterials can be altered using a number of techniques, such as coupling with methacrylic anhydride (methacrylation of backbone). Because of its appealing set of qualities listed above, chitosan hydrogels are a preferred biomaterial for bioprinting, and crosslinking them helps to overcome their inherent slight drawbacks. As an outcome, chitosan and its derivatives are appropriate for tissue engineering applications such as replacing or repairing bone, cartilage, and skin. As natural biomaterials, chitosan-based bioinks are thought to be the best choice for designing and creating multiple scaffolds using 3D bioprinting because of their remarkable biological qualities and unique dynamic reversibility [62,63].

Gelatin, a protein derived from collagen, is shear-thinning, has cell-adhesive ligands, may be broken by cells enzymatically, and physically gels below room temperature. Gelatin bioinks have garnered a lot of interest in tissue development because of these properties. In order to find bioinks that support certain cell types, many gelatin-based bioinks have been developed thus far. Gelatin-based bioinks have been used with a variety of encapsulated cell types (i.e., primary cells, stem cells, and cancer cells) and bioprinting processes (extrusion, droplet, and light/laser-based) [64]. While gelatin and collagen have a similar molecular makeup, gelatin has a less organized macromolecular structure and nevertheless contains crucial binding moieties for cell adhesion, such as the tripeptide Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD) sequence. Furthermore, it has peptide sequences that the matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) enzymes may break and exhibits lower antigenicity than collagen. Gelatin’s sensitivity to MMP allows it to be broken down by the MMP enzymes released by encapsulated cells, which promotes microenvironment remodeling. Additionally, gelatin has viscoelastic characteristics that support cell proliferation, differentiation, and migration. These qualities make gelatin one of the most popular natural biomaterials for bioprinting [65].

The FDA authorized the use of silk fibroin (SF), a natural polymer derived from the silkworm Bombyx mori, as a biomaterial in 1993. Because of its remarkable biocompatibility, adaptable mechanical characteristics, regulated biodegradation, and low tendency to elicit immunological responses, it has been widely used recently in the tissue engineering and biomedical domains. Gly–Ala–Gly–Ala–Gly–Ser repetitions of amino acid sequences make up SF, which self-assembles to create a β-sheet structure. SF has been shaped into a variety of shapes for a wide range of biomedical applications, including films, hydrogels, sponges, electrospun mats, and nano- or microparticles. Because of the versatility it offers, SF has been used as a major bioink material for a number of 3D printing techniques, such as extrusion-based and inkjet bioprinting [66]. However, SF’s limited abundance and poor viscosity are major disadvantages for using it as a bioink for broad 3D printing applications. To improve its printability, SF is therefore being used as a bioink for 3D bioprinting by combining it with other high-viscosity materials. Adding more crosslinking to natural biomaterials is a popular tactic to enhance their mechanical qualities and printability. A cross-linking technique called photo-crosslinking has produced more intra- and intermolecular chemical connections, resulting in a quick and reliable cure [67].

An inexpensive biopolymer, alginate—also known as algin or alginic acid—is typically made from calcium, magnesium, and sodium alginate salts found in the intracellular spaces and cell walls of various brown algae. Alginate is made up of β-d-mannuronic (M) and α-l-guluronic acids (G), which are (1–4) connected. Longer M or G blocks, separated by MG regions, form the polyanionic linear block copolymer known as alginate. Alginate is a negatively charged polysaccharide. This soluble biopolymer has excellent biocompatibility and promotes cell development. While MG and M blocks improve flexibility and G blocks boost gel formation, an excessive quantity of M blocks may result in immunogenicity. Capillary forces can trap water and other molecules in an alginate matrix while yet allowing them to disperse. This property qualifies alginate hydrogels for bioink compositions [68]. Numerous alginate-based inks have been documented, some of which are marketed commercially (e.g., “CELLINK”) [69]. One of the most beneficial aspects of alginate is its adaptability to a range of bioprinting technologies (such as extrusion, inkjet, and microfluidic bioprinting) and scaffold construction techniques (such as spheroids, vascular constructs, and microfluidic fiber-shaped scaffolds) [70].

Synthetic polymers are man-made polymers with modifiable chemical structures and physical characteristics that are manufactured by chemical processes. In contrast to natural polymers, the majority of synthetic polymers possess super mechanical features. Because 3D printing frequently uses organic solvents, heat, and toxic activators that may lessen the bioactivities of cells and growth factors, synthetic polymers are relatively bio-inert and cannot easily incorporate bioactive ingredients, such as cells and growth factors, directly. There are synthetic polymers that decompose naturally. In vivo, microbes or biological fluids can break down these polymers [71].

Polyethylene glycol (PEG), Polycaprolactone PCL, polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP), poly(L-lactic) acid (PLA), Polyurethane (PU) and poly(lactic-co-glycolic) acid (PLGA) are examples of synthetic polymers that are often utilized in 3D bioprinting. They may be tailored to meet the mechanical property specifications for the target tissues and organs, as well as tissue-specific breakdown [72].

Synthetic polymers with appropriate mechanical qualities can tolerate internal and external stresses throughout the in vivo implantation and 3D printing phases. Therefore, as compared to natural polymers, the majority of synthetic polymers have several inherent benefits in the field of bioartificial organ 3D printing. Convenient synthesis, resource abundance, ease of processing, stress tolerance, light weight, and affordability are among the apparent benefits [71].

Despite this, they only make up around 10% of the systems utilized in bioprinting because of an assortment of drawbacks that prevent them from being employed in translational applications (hard to encapsulate cells, usage of toxic solvents, melting temperatures greater than body temperature). Furthermore, locations for cellular recognition and other biological signals present in natural extracellular matrix (ECM) that promote cellular proliferation and differentiation are typically absent from synthetic polymers. The existence of flexible side groups becomes necessary for appropriate customization of a construct’s mechanical and biological features, even if functionalization of synthetic bioinks might enhance their biological qualities [72].

PEG is a synthetic polyether that is inexpensive, soluble in organic solvents or aqueous solutions, and has a high degree of biocompatibility. PEG is widely used for wound dressing and medication administration because it has no negative effects on cell adhesion or proliferation. Cell adhesion can be improved by including cell-binding motifs into the PEG hydrogel network, such as arginylgly-cylaspartic acid (Arg-Gly-Asp) peptides [73].

Another work used polyethylene glycol diacrylate (PEGDA) and self-assembled peptide nanofibers to generate a hybrid bioink for 3D printing lumens. First, peptide-loaded 2D and 3D layers of adult human dermal fibroblast (aHDF) cells were seeded, and the behavior of the cells was examined. After being injected into the 3D hydrogel, the cells’ shape remained spherical and closely matched that of the 2D overlay hydrogels. HDF cells were able to attach and multiply on PEGDA/peptide lumens but did not adhere to unmodified PEGDA lumens. Furthermore, a characteristic distributed F-actin shape was shown by HDF cells implanted on the hybrid PEGDA/peptide lumens [74].

Through the use of off-stoichiometry thiolene click chemistry, a novel PEG microgel was developed. It was readily extruded as bioink and demonstrated excellent stability following printing because of the intraparticle adhesion forces. In the end, the method generated printed structures with long-term stability and endurance and permitted a second thiolene click reaction. One benefit of this bioink is its modularity, which is a result of the versatile physicochemical features of PEG microgels. Since the cells could spread and multiply in the PEG micro-gel interstitial gaps, the bioink’s low extrusion force and the thiolene annealing process enabled good cell survival during bioprinting [75].

Another study uses therapeutic protein-loaded nanoengineered bioink to control cell activity in a 3D-printed structure. A 2D synthetic nanoparticle and a hydrolytically degradable polymer are used to develop the bioink. Acrylate-terminated degradable macromer is produced using a Michael-like step growth polymerization process used to synthesize poly(ethylene glycol)-dithiothreitol (PEGDTT). Shear-thinning bioinks with excellent printability and structural integrity are created when 2D nanosilicates are added to PEGDTT. Altering the PEG: PEGDTT ratio and the concentration of nanosilicates can modify the mechanical characteristics, swelling kinetics, and rate of degradation of 3D printed structures. Protein therapies may be contained in 3D printed structures for an extended period of time because of the large surface area and charged nature of nanosilicates. The fast migration of human endothelial umbilical vein cells was facilitated by the sustained release of pro-angiogenic therapies from 3D printed structures [76].

The United States Food and Drug Administration (USFDA) has approved PCL, a thermoplastic polymer, for use in adhesion barriers in the human body, suture materials, and drug delivery devices. PCL has a glass transition temperature (Tg) of approximately −60°C and a melting point of around 60°C. It is a biodegradable, semicrystalline polyester that breaks down under physiological circumstances by hydrolyzing its ester bonds. The biodegradation rate of PCL is far slower than that of the majority of natural polymers, including collagen, fibrin, and gelatin [77].

3D-printed scaffolds constructed from polycaprolactone (PCL) and bioink produced from decellularized human cartilage were utilized in a study to improve mechanical stability and tissue regeneration. Similar to natural cartilage, the de-cellularization technique preserved glycosaminoglycan and total collagen while successfully eliminating cellular components. The bioink was formulated by incorporating decellularized human cartilage particles into hyaluronic acid and carboxymethyl cellulose gels, optimizing the rheological properties for 3D printing. The decellularized bioink made from human cartilage showed no cytotoxicity in in vitro testing, and it promoted the migration and chondrogenic differentiation of human adipose-derived stem cells. Using this bioink in conjunction with PCL, 3D-printed scaffolds were generated, and the effectiveness of the scaffolds was assessed in rabbits over the course of a year after implantation. According to the results, the scaffolds showed notable neovascularization and chondrogenesis and retained their structural integrity throughout the course of the year. In scaffolds with higher ratios and more decellularized cartilage, histological investigation showed enhanced blood vessel development [78].

The natural human meniscus, which has a zone-specific biochemical composition, was intended to be functionally and structurally mimicked by the 3D-printed meniscus scaffold. In particular, the design included a cartilaginous inner area and a fibrous outer portion. A composite material made of polycaprolactone (PCL) reinforced with nanohydroxyapatite (HA) was chosen as the base component in order to accomplish this. The selection was based on the material’s mechanical characteristics, which closely resemble those of natural meniscus tissue. Two different hydrogels were used as bioinks: glycidyl methacrylate-modified silk fibroin (PVA-g-GMA/SF-g-GMA) for the inner region, which was intended to induce chondrogenesis, and gelatin methacrylate (GelMA) for the outer region, which was thought to encourage fibrogenesis. The scaffold was printed using a dual-nozzle 3D printing method. The inner area demonstrated chondrogenic properties while the outside region successfully displayed fibrogenic features, both of which successfully mirrored the zonal biochemical composition of the natural meniscus. Additionally, the mechanical characteristics of the 3D-printed PCL/HA/hydrogel scaffold were similar to those of the human meniscus, ensuring structural integrity. The scaffold’s form was quite similar to that of the lateral and medial menisci [79].

In another investigation, two structurally distinct scaffolds—a PCL/45S5 Bioglass (BG) composite and a PCL/hyaluronic acid (HyA) composite—were created using 3D printing technology and assessed for their ability to promote dentin and pulp tissue regeneration, respectively. Their physicochemical analysis demonstrated that the mechanical characteristics, surface roughness, and bioactivity of the PCL/BG scaffolds were enhanced by the presence of BG. Additionally, applying HyA to the PCL scaffold’s surface significantly increased the scaffolds’ hydrophilicity, which improved cell attachment. Additionally, the gene expression data demonstrated that the presence of both PCL/BG and PCL/HyA scaffolds significantly increased the expression of odontogenic markers [80].

PU is a class of linearly segmented polymers made up of organic (hard segment) and oligodiol (soft segment) units joined by carbamate (urethane) bonds (–NH–(C=O)–O–). Because of their superior mechanical qualities and superior biocompatibilities, PUs—which can be either biodegradable or non-biodegradable—have found extensive usage in biomedical applications. It is distinguished by the solvent used, which is either an organic solvent-based traditional PU or a water-based PU. The latter uses water as a solvent, whereas the former uses volatile organics. The chemical composition of PUs determines their physicochemical and physicochemical characteristics, including biodegradability, PH sensitivity, and thermosensitivity [81]. Because of their superior mechanical qualities, adjustable chemical structures, and greater biocompatibilities, biodegradable PUs are currently being utilized extensively for the 3D printing of bioartificial organs [82].

In a study prior to gelation, neural stem cells (NSCs) were incorporated into the polyurethane dispersions. After that, the NSC-containing dispersions were printed and kept at 37°C. The NSCs in PU hydrogels demonstrated superior differentiation and proliferation. Furthermore, the function of the impaired nervous system may be restored by injecting NSC-rich PU hydrogels into the zebrafish embryo neural damage model. Moreover, following the implantation of the 3D-printed NSC-loaded PU structures, the function of adult zebrafish suffering from traumatic brain damage was restored [83].

In another work, a novel waterborne PU (WBPU)gel that is biodegradable and thermoresponsive was developed as a bioink. For cell reprogramming, PU hydrogel was co-extruded with human fibroblasts and FoxD3 plasmids. The outcomes demonstrated that human fibroblasts co-printed with FoxD3 in the thermoresponsive PU hydrogel could undergo reprogramming and develop into cells that resembled neural crest stem cells and had an elevated cell viability [84].

In a different study, 3D bioprinting technology was used to generate scaffolds made of functional alginate and WBPU for the regeneration of articular cartilage. Mature chondrocytes have been embedded into various alginate-WBPU inks in order to manufacture the scaffolds for 3D bioprinting. Bioinks demonstrated superior 3D printing capability, cell viability, and structural integrity, making them ideal for scaffold construction. Following 28 days of in vitro cartilage formation experiments, scaffolds maintained a cell population of 104 chondrocytes/scaffold in differentiated phenotypes and were able to synthesize up to 6 μg of glycosaminoglycans (GAG) and specialized ECM [85].

Poly(N-vinylpyrrolidone) (PVP), a synthetic polymer that has been around since 1938, has a distinctive ability to dissolve in water and a variety of organic solvents. Researchers have shown considerable interest in PVP for biomedical applications, attributed to its inert characteristics, stable chemical composition, low toxicity, non-irritating effects on biological systems, and overall biocompatibility. PVP has found broad application in the development of hydrogels, wound dressings, nanofibers/scaffolds, drug delivery systems, and gene therapies [86].

In a study, the physical characteristics of the bioinks were altered using an inert polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP360, molecular weight = 360 kDa) polymer, and the impact of these qualities on printing efficiency and cell health was examined. The findings of the experiment demonstrated that a greater viscoelasticity of the bioink aids in stabilizing droplet filaments prior to their rupture from the nozzle orifice. Since the polymer in the printed droplets gives the encapsulated cells an extra cushioning effect (greater energy dissipation) during droplet impact on the substrate surface, improves the measured average cell viability even at higher droplet impact velocity, and preserves the printed cells’ ability to proliferate, additional analysis revealed that cell-laden bioinks with higher viscosity exhibited higher measured average cell viability (%) [87].

PCL and PVP were employed as matrix polymers in an investigation by Izgordu et al. Low-molecular-weight chitosan (CS), hyaluronic acid (HA), and alginic acid sodium salt (SA) were integrated independently with the polymer matrix to create the constructs. According to the findings of mechanical characterization, the printed PCL/3wt.%PVP/1wt.%CS had the maximum compressive strength, measuring around 9.51 MPa. 5.38 MPa was the difference in compressive strength between PCL/3wt.%PVP and PCL/3wt.%PVP/1wt.%CS. Mitochondrial dehydrogenase activity was used to examine the constructions’ biocompatibility, and in vitro experiments using the mesenchymal stem cell line revealed that the PCL/3wt.%PVP/1wt.%HA composite construct had higher cell viability than the other constructs [88].

Another study used macromolecules of PVP to generate bioink. The printability of several PVP-based bioinks was assessed, and the printed cells’ short- and long-term vitality was initially examined. The results showed that a bioink with a threshold Z value of ≤9.30 may print cells without causing any major problems. The survival of printed cells is dependent on the Z values of the bioinks. The cell production was then assessed for 30 min. PVP molecules were shown to reduce cell adhesion and sedimentation throughout the printing process; the 2.5% w/v PVP bioink showed the most constant cell output over a 30-min timeframe, enhancing cell survival and homogeneity throughout the bioprinting experience [89].

PLA is an aliphatic and biodegradable polyester made from lactic acid obtained from renewable sugarcane or maize starch. The cyclization and oligomerization processes combine to form PLA, or lactic acid cyclic dimer. Due to its biocompatibility and lack of toxicity or carcinogenic effects on local tissue, PLA is frequently utilized in biomedical applications [90].

A 3D printed PLA: calcium phosphate (CaP): Graphene oxide (GO) scaffold was designed in a study for bone tissue engineering purposes. Polylactic acid (PLA), CaP, and the optimized GO dose (0.10 mg mL−1) were combined to fabricate a 3D printed PLA: CaP:GO scaffold, which upon physicochemical characterization (SEM/EDS, XRD, FT-Raman, nano-indentation) and in vivo tests, confirmed its biocompatibility, enabling a novel approach for bone tissue-related applications [91].

In a study, mixed matrix scaffolds were created using a PLA/mesoporous bioactive glass (MBG) composite with a weight ratio of 30:70, which resembles the natural bone composition. According to the SEM study, the 3D printed PLA/MBG composite scaffolds have pores that range in size from 500 to 700 μm, indicating that they are macroporous and beneficial for bone cell proliferation. The PLA/MBG composite scaffold’s good bioactivity behavior was demonstrated by the in-vitro bioactivity evaluation, which revealed quick apatite crystallization by achieving a Ca/P ratio of 1.66 similar to natural bone mineral during the third day after SBF treatment. Through in-vitro biological evaluation utilizing MG-63 osteosarcoma cells, the 3D bioprinted PLA/MBG composite scaffold shown encouraging responses in terms of cell attachment and proliferation, mineralization, and gene expression features [92].

Kolan et al. examined the survival of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells (ASCs) in an alginate-gelatin (1:1) hydrogel (bioink) that is deposited in the spaces between composite filaments of PLA and borate glass. PLA + B3 glass composites were generated by adding B3 glass to PLA in two distinct weight ratios (50 and 33%). The mechanical characteristics, pH change of the surrounding fluid, and weight loss of the 3D printed composite scaffold were all examined over time. A physical examination of the composite scaffolds revealed full glass dissolution after two weeks and enhanced mechanical qualities. To examine ASC viability, cellularized scaffolds were bioprinted in three different configurations: PLA + Bioink, PLA + Bioink, and PLA + B3 glass + Bioink. They were then grown under dynamic circumstances. With hypoxic-like circumstances and decreased viability in the bottom area to higher viability in the upper layers of the scaffold, the results showed non-uniform cell viability along the scaffold thickness [93].

Polylactic-Co-Glycolic Acid (PLGA)

PLGA is a biodegradable functional polymer organic molecule formed by the polymerization of two monomers, lactic acid (LA) and glycolic acid (GA), with excellent biocompatibility and no biotoxicity [94]. Depending on the LA:GA ratio, PLGA’s molecular weight (g/mol) can range from thousands to hundreds of thousands. Because of its biodegradability, biocompatibility, broad range of erosion times, and flexible mechanical qualities, PLGA is widely employed in tissue engineering and drug administration. The FDA has authorized this polymer due to its physical strength and biocompatibility, which have led to its widespread usage in several studies [95].

In one study, a 3D printed dermal scaffold containing bioactive PLGA was designed for burn wound healing. Ring-opening metathesis polymerization (ROMP) was used to create bioactive brush copolymers with pendant side chains of PLGA and PEGylated Arg-Gly-Asp tripeptide (RGD) or HA. These copolymers demonstrated strong thermal stability when processed using melt-extrusion techniques. The 3D printed scaffolds showed high biocompatibility in both in vivo animal models and in vitro cell testing. In comparison to Biobrane, the clinical gold standard for treating second-degree burn wounds, a porcine investigation using a partial thickness burn wound model demonstrated that these PLGA scaffolds promoted re-epithelization with less inflammation [96].

Song et al. studied the impact of three-dimensional (3D) printed PLGA scaffolds mixed with Gly-Phe-Hyp-Gly-Arg (GFOGER) and bone morphogenetic protein 9 (BMP-9) on extensive bone defect recovery. PLGA scaffolds were created using the 3D printing technique, and the sample was examined using optical microscopy, SEM, XRD analysis, water absorption, compressive strength, and other techniques. This scaffold has slower rates of degradation and mechanical qualities that are acceptable. Over the course of a 12-week in vivo investigation, the scaffold demonstrated improved new bone mineral deposition and density following surface modification using GFOGER peptide and BMP-9. This scaffold up-regulated the expression of Runx7, OCN, COL-1, and SP7, which helped to produce the observed uniform trabeculae development and new bone regeneration, according to histological examination and Western Blot [97].

Choe et al. designed a variety of bioinks for mesenchymal stem cell (MSC) printing and osteogenic differentiation induction utilizing poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) (PLGA) nanoparticles loaded with bone morphogenetic protein-2 (BMP-2). PLGA nanoparticles added to alginate might boost the bioink’s printability and mechanical characteristics. BMP-2-loaded PLGA nanoparticles (NPBMP-2) exhibited up to two weeks of sustained BMP-2 release in vitro. Additional in vitro research revealed that, in comparison to other controls, bioinks made of alginate and NPBMP-2 markedly increased the osteogenesis of MSCs, as shown by increased calcium deposition, alkaline phosphatase activity, and osteogenic marker gene expression [98].

PVA, a synthetic polymer made by breaking down poly (vinyl acetate), has the repeating unit [-CH2-CH(OH)-]n and dissolves easily in water. Because of the large number of hydroxyl (-OH) groups that are distributed throughout its backbone, it is highly water-attracting (hydrophilic) and has the ability to create hydrogen bonds. PVA’s well-known ability to form thin films is also a result of these properties. Importantly, PVA’s hydroxyl groups make it simple to modify or combine with other polymers, improving its mechanical strength and flow characteristics—two crucial aspects for utilization in bioinks and 3D printing [99].

Small-diameter artificial blood vessels were developed in a study using a porous composite hydrogel of sodium alginate, gelatin, and polyvinyl alcohol (SA/Gel/PVA). Using the multiple crosslinking approach, the porous composite hydrogel ink was designed with the goal of resolving the issues of inadequate mechanical characteristics and an unsatisfactory printing effect of blood vessels with tiny diameters [100].

Polyvinyl alcohol cryogels (PVA-C) were used in an alternate study for vascular tissue engineering because of their hydrophilicity, biocompatibility, and mechanically adjustable qualities. Sub-zero extrusion-based three-dimensional (3D) bioprinting was used to manufacture multi-layered PVA-C structures, and their mechanical performance was examined. The outcomes demonstrated that a multi-layered design affects PVA-C’s mechanical profile and indicated that functionally graded design techniques might improve compliance matching and replicate native blood vessel biomechanics in small-diameter vascular grafts [101].

A new 3D bioprinted construct was designed by Loukelis et al. using pre-osteoblastic cells, the synthetic polymer PVA and the natural anionic polysaccharide gellan gum (GG). Additionally, as an osteoinductive biomaterial, nano-hydroxyapatite (nHA) was added to the GG/PVA blend. The findings showed that the generated bioinks had biological responsiveness and viscoelastic characteristics that make them appropriate for bone tissue engineering applications [102].

Bioceramics are a category of ceramics that emerged in the 1970s. Bioceramics offer superior biocompatibility and bioactivity potential in addition to the mechanical qualities of ceramics. Thus, these biomaterials are also utilized in the field of tissue engineering to induce osteogenesis in many dental implants, bone grafts, and scaffolds [103]. However, the brittle surface and limited elasticity of bio-ceramics restrict their application in implants. To increase their strength and flexibility, they are typically coated or mixed with other materials. Alumina, zirconia, bioactive glass, glass-ceramics, hydroxyapatite, and resorbable calcium phosphates are some of the most extensively utilized bioceramics [103,104]. High density ceramics like zirconia and alumina have excellent mechanical strength and resistance to corrosion; nevertheless, prior research indicates that zirconia is somewhat less resistant to corrosion than alumina. The two may be used as hip and knee replacement components since they are also biocompatible and bioinert. As a body implant, they can reduce negative tissue responses to ion toxicity from metallic stents or prostheses and provide structural support that prevents stress shielding.

The chemical formula for HAp, a naturally occurring calcium phosphate-based mineral, is Ca10(PO4)6(OH)2. Its structure is comparable to that of bone mineral, a biological apatite found in the human body that accounts for between 60 and 70 percent of the dry weight of human bone tissues. Its physical and chemical characteristics are comparable to those of human bone and tooth tissues [105]. Hydroxyapatite is well-known for its capacity to repair injured cells and form connections with nearby tissues. Because of its bioactivity and bioresorbability, osteogenesis will stop when the substance eventually dissolves in the body. Therefore, scaffolds are made from hydroxyapatite-rich natural materials such as animal bones, corals, algae, shells, and fish scales [106]. HAp has great osteoinductivity and osteoconductivity, as well as outstanding biocompatibility and bioactivity, non-inflammatory and non-toxic properties. Additionally, it stimulates cell growth and proliferation and vitalizes growth factors. Thus, HAp is regarded as a very promising bone replacement and implant material. However, HAp is not appropriate for many BTE applications due to its poor mechanical qualities, sluggish resorption and remodeling rates, and slow degradation rates in vivo. For this reason, HAp is typically combined with other synthetic or natural polymers to produce composite scaffolds that are more effective [107].

The investigation involved the preparation of polymer solutions based on methacrylated gelatin and methacrylated hyaluronic acid modified with HAp particles (5 weight percent) as primary human adipose-derived stem cells were encapsulated in HAp-containing gels and cultured for 28 days, the storage moduli ascended substantially to 126% ± 9.6% as compared to the value on day 1 due to the HAp’s exclusive impact. The ink demonstrated outstanding printability when used as bioinks to build up pertinent geometries utilizing the cell-laden polymer solutions, and the integrity of the printed grid structure held up during a 28-day culture period. As shown by rheological measurements and bone component staining, the results showed that HAp-containing bioinks and hydrogels based on methacrylated gelatin and hyaluronic acid are both highly appropriate for the development of pertinent three-dimensional geometries with microextrusion bioprinting and have a notable positive impact on bone matrix development and remodeling in the hydrogels [108].

In another investigation, two bioinspired nanohydroxyapatite (nHA)s, differing in their chemical compositions, crystallinity, and structures, were produced and analyzed: one is a more crystalline, needle-shaped Mg2+-doped nHA (N-HA), while the other is a more amorphous, rounded Mg2+- and CO32–-doped nHA (R-HA). To explore how various compositions and structures of these nanoparticles influence the bioprinting of human bone marrow stromal cells (hBMSCs), gelatin and gelatin methacryloyl (GelMA) were chosen as the backbone for the bioink. Both nHAs demonstrated substantial cell viability, with N-HA exhibiting a large increase in metabolic activity under non-osteogenic conditions and R-HA exhibiting a considerable increase with osteogenic stimulation. These results emphasize the significance of both chemistry and morphology in bioink performance by indicating that the two nHAs interact with their surroundings in distinct ways. Osteogenic differentiation further demonstrated how nHAs’ physicochemical characteristics affect osteogenic markers at the RNA and protein levels [109].

Using silk-hydroxyapatite bone cements with osteoinductive, proangiogenic, and neurotrophic growth factors or morphogens for faster bone formation, functionalized 3D-printed scaffolds for bone regeneration were created in another study. Building on the understanding that the osteoinductive factor Bone Morphogenetic Protein-2 (BMP2) can also favorably impact vascularization, Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) can affect osteoblastic differentiation, and Neural Growth Factor (NGF)-mediated signaling can affect bone regeneration, 3D printing was used to create macroporous scaffolds with controlled geometries and architectures that support osseointegration. The materials were osteoconductive, cytocompatible, and preserved the action of the morphogens and cytokines, and the scaffolds had mechanical qualities appropriate for bone. Based on the overexpression of genes linked to osteoblastic differentiation, synergistic effects of BMP-2, VEGF, and NGF were found in terms of osteoblastic differentiation in vitro [110].

Numerous ceramics based on calcium phosphate (CaP), including hydroxyapatite (HA), biphasic calcium phosphate (BCP), calcium polyphosphate (CPP), and β-tricalcium phosphate (β-TCP), have exceptional osteoinductive and osteoconductive qualities. Although β-TCP and hydroxyapatite (HA), the mineral component of natural bone tissue, have molecular similarities, β-TCP degrades more quickly because of its lower Ca/P ratio. When processed into different porous shapes, β-TCP, a biocompatible ceramic, offers an environment that is conducive to cell adhesion and growth. However, ceramics are problematic to utilize in load-bearing body areas because of their high brittleness and poor strength [111].

Melo et al. coated 3D-printed β-TCP scaffolds with bioactive glasses, 45S5 (45SiO2–24.5Na2O–24.5CaO–6P2O5, wt.%) and 58S (58SiO2–33CaO–9P2O5, wt.%), utilizing sol-gel solutions using a vacuum impregnation approach. The β-TCP ink displayed pseudoplastic behavior, which facilitates 3D printing. With well-aligned filaments and little collapse of the bottom layers during sintering, the resultant scaffolds showed excellent reliability to the designed model. An apatite mineralization experiment in simulated bodily fluid was used to validate bioactivity. It showed that both coated scaffolds precipitated hydroxyapatite, albeit in different morphologies [112].

β-TCP scaffolds with different amounts of multi-walled carbon nanotubes (MWCNT) (0.25–1.00 wt%) were designed in a study. The results show that adding MWCNTs improved the viscosity of β-TCP suspensions in a concentration-dependent manner. The addition of MWCNT decreased the in vitro degradation of β-TCP and altered compressive strength. Furthermore, the results showed that the scaffold enhanced the expression levels of the genes for alkaline phosphatase, osteopontin, and osteocalcin in adipose-derived stem cells; however, MWCNT produced greater levels of gene expression [113].

In another study, cationic functional molecules were added to hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. In the 3D-printed tricalcium phosphate/hydroxyapatite (TCP/HA) scaffold, 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (HA-NPs-APTES) containing microRNA-302a-3p (miR) can promote the repair of the critical-sized bone defect. Two techniques were used to modify 3D-printed TCP/HA with HA-NPs-APTES (M1, M2). The M1 and M2 scaffolds both have cell adhesion on their surface and were biocompatible. Following effective delivery, the M2 scaffold demonstrated a significant increase in miR, which led to the overexpression of RUNX2 mRNA and the downregulation of its target mRNA, COUP-TFII. At all-time points, the calvarium defect with M2 scaffold also had much greater BV/TV and more filled gaps. New bone grew at the middle of the HA-NPs-APTES-miR scaffold earlier than controls, according to histomorphometry. HA-NPs-APTES-modified TCP/HA scaffold improved bone regeneration and made miR distribution easier [114].

In 1971, Hench et al. discovered 45S5 bioactive glass (45S5 Bioglass®), a silicate glass with 45% silica (SiO2), 24.5% calcium oxide (CaO), 24.5% sodium oxide (Na2O), and 6% phosphorous pentoxide (P2O5), which paved the way for the field of bioactive materials. “Bioactive” in this instance describes “a material that elicits a specific biological response at the material surface which results in the formation of a bond between the tissues and the materials”. Bioactive materials are designed to modify the extracellular matrix in a regulated way and interact with the biological environment to provide the desired therapeutic effect. Bioactive materials are preferred for BTE scaffolds for the repair or replacement of bones, joints, and teeth. Bioactive materials, such as bioactive glasses (BGs) and bioactive ceramics, modify their surfaces dynamically in response to biological fluids. The creation of a highly reactive hydroxycarbonate apatite (HCA) layer offers a bonding contact with both bone and soft tissues [115]. BG utilized in bone tissue engineering is often categorized as silicate-, phosphate-, and borate-based BG, based on the forming units of the glass network. Although bulk BG may be used in bulk form to repair bone defects, BG/polymer composites are a more practical option because of their higher ductility and plasticity [116].

In a research, silicate-based, three-dimensional bioactive glass scaffolds were constructed employing novel sol-gel ink-based robocasting, and their structural and morphological properties were investigated. Furthermore, under static conditions, their in vitro bioactivity was examined in phosphate-buffered saline at 37°C and simulated body fluids. In contrast to the colloidal-based robocasting approach that uses bioactive glass particles, the results show that the patterned, multilayered, macroporous bioactive glass scaffolds can be successfully formed. Additionally, the structures prepared in this manner can be manufactured in considerably finer filament dimensions. Additionally, it was demonstrated that the bioactive glass scaffolds, which were maintained in physiological fluids, developed hydroxyapatite on their surface [117].

In another paper, two-photon lithography (TPL) is employed for the first time to form BG with single-micron features. A composite comprising BG nanoparticles is constructed with TPL and thermally treated to yield glass scaffolds. The glass utilized in a study showed cytocompatibility with human mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs) and in vitro bioactivity in simulated bodily fluid, which qualified it as a material for tissue engineering [118].

In another study, nanocomposites were made using mesoporous bioactive glasses (MBGs) in the ternary SiO2, CaO, and P2O5 system doped with metallic silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) that were homogeneously inserted in the MBG matrix. Three-dimensional mesoporous bioactive glass scaffolds with silver were developed, displaying mesopores, macropores, and ultrapores that are evenly linked. The biological characteristics of Ag/MBG nanocomposites were assessed using MC3T3-E1 preosteoblastic cell culture tests and bacterial (E. coli and S. aureus) assays. The findings demonstrated that while preosteoblastic proliferation declined with increasing silver concentration, MC3T3-E1 cell shape remained unaffected. According to antimicrobial experiments, the higher concentration of AgNPs in the MBG matrices was positively correlated with the suppression of bacterial growth and the breakdown of biofilms. Moreover, in vitro co-culture of S. aureus bacteria with MC3T3-E1 cells demonstrated that AgNPs had a minor impact on cell proliferation measures and that their presence was essential for antibacterial action [119].

Because of their superior mechanical qualities and structural stability, metals—the first materials to be employed as orthopedic devices—have proven to be appealing biomaterials for bone implants. However, employing metal as a scaffold has several drawbacks. A metal implant, for example, has a greater Young’s modulus than natural bone, which may result in stress shielding, which is a reduction of bone as a result of the implant removing stress from the bone. Another disadvantage of using metal as a scaffold is its low degradability, which might eventually prevent the host cells from forming new bone tissues and result in long-term concerns, including inflammation and corrosion. Numerous approaches were proposed to address this, including boosting porosity and mixing metal with other substances that can offset its disadvantages [120].

Bone scaffolds have been made using iron (Fe) and magnesium (Mg)-based metals, including pure Fe, Mg-RE (rare earth) alloys, Mg-Ca, Fe-Mn alloys, and Fe foam. Compared to magnesium (41GPa) and its alloys (44GPa) and 316L stainless steel (190GPa), iron has a greater elastic modulus (211GPa) [121]. Ti, Ti alloys, Mg, Fe, 316L stainless steel, and NiTi are the metal scaffolds constructed primarily using AM. Due to its inexpensive cost and comparable elastic modulus to human bone, Ti–6Al–4V (Ti alloy) is a preferred choice [122].

For metallic scaffolds, magnesium and its alloys work well as well. They are biodegradable in biological fluids, have mechanical qualities comparable to those of human bone, and have an ionic composition that is compatible with the body’s physiological systems. Because magnesium alloys have a lower elastic modulus than titanium alloys, they can lessen the stress-shielding effect, which is the reduction of bone density brought on by the removal of normal stress from the bone as a result of the presence of an implant, which causes the implant to loosen. Nevertheless, their fast rate of corrosion results in the quick release of breakdown products into the body [122].

Due to its robust mechanical qualities, superior biocompatibility with living tissues, and exceptional longevity, titanium and its alloys have been among the most widely used metal-based bone implants since they were first used in surgeries in the 1950s. Ti is readily formed and adjusted to imitate the mechanical characteristics of bone, providing an osteogenic environment for cells [123]. However, Ti cannot be replaced by newly developed bone since it is not osteoconductive and biodegradable under normal physiological circumstances. Furthermore, bulk Ti implants may result in stress shielding because of the significantly larger Young’s modulus of Ti compared to cortical bone [124]. Numerous strategies including coating, surface treatment, and structural modification, were proposed to address its shortcomings [120].

A variety of coating techniques were proposed for Ti, including coating with antimicrobial substances to avoid implant-induced inflammation [125] and coating with osteogenic agents, such as HAP or silica nanoparticles to encourage bone growth [126,127]. Kapat et al. employed powder metallurgy to create Ti6Al4V with various pore sizes and porosities, and then assessed the pore distribution, mechanical characteristics, surface roughness, contact angle, and protein adsorption capacity. The optimum effect on cell distribution and differentiation was established by further in vitro and in vivo studies [128]. High biocompatibility and considerable flexibility for bone scaffolding have been demonstrated by nitinol (NiTi), a titanium-nickel metal alloy that has also been utilized for nail production and as a spine separator in the treatment of scoliosis. It is widely used in orthopedic implants, such as spinal rods, arc nails, artificial ribs, arched connections, patellar concentrators, three-dimensional memory alloy fixation systems, and interbody fusion devices, because of its beneficial shape memory effect and superelasticity [129].

Since SS has a high chromium content (12%) and is biocompatible and corrosion resistant, it is one of the common metal biomaterials used in orthopedic implants. Because of its desirable mechanical qualities, stainless steel may be used as a sturdy scaffold in a variety of load-bearing shapes, including plates, rods, and screws. However, SS requires additional improvements, such as surface modification, coating, and material combination, to promote bone regeneration without significantly altering its advantageous qualities [130,131].

Cobalt, a crucial component of cobalamin, promotes angiogenesis and red blood cell formation by activating hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1), which in turn speeds up bone repair. More precisely, cobalt is known to cause hypoxia, which activates HIF-1 and promotes cellular processes that promote regeneration [132]. Furthermore, the production of collagen matrix for bone regeneration is significantly impacted by cobalt. Because of its mechanical strength and in vivo corrosion resistance, cobalt chromium is one of the most commonly utilized alloys in the area of regenerative medicine [133].

In a study, calcium/cobalt alginate beads were utilized to encapsulate human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Instead of depending on expensive growth factors like transforming growth factor betas or bone morphogenetic proteins to facilitate the differentiation of human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells into chondrocytes that produce cartilage, these advanced scaffolds for promoting chondrogenesis utilize the combined effects of the alginate matrix and Co+2 ions [134].

In an alternate investigation, new scaffolds made of porous PVA polymer and bioactive glasses (BG) with cobalt were developed by combining the non-toxicity, non-carcinogenicity, and processability of PVA with the osteogenic and bioactive qualities of BG and the angiogenic effect of Co using the sol-gel and foaming processing methods. This resulted in a new scaffold with angiogenic qualities. Co-incorporated samples had favorable pore sizes and high porosity. In tissue engineering applications, PVA–BG hybrid scaffolds with Co demonstrated an ionic release rate within the therapeutic range and show potential for angiogenesis [135].

3.4 Carbon Based Nanomaterials

Since carbon and carbon-based materials have unique mechanical, electrical, thermal, tribological, and biological properties that enable high-performance applications in every conceivable industrial field—from biotechnology to aerospace, from energy to electronics—they are frequently positioned as the materials of the future. Typically, a single kind of carbon material has been used with varying degrees of effectiveness to restore a single tissue. Remarkably, recent breakthroughs in the synthesis, processing, and use of carbon-based materials, such as the discovery of carbon nanotubes, fullerenes, and graphene, have broadened the scope of this material family and paved the way for the creation of cutting-edge tissue engineering and biomedical devices. With their exceptional qualities and enormous potential, every class of carbon-based nanomaterials, including 3D graphite, 2D graphene, 1D carbon nano-tubes (CNTs), 0D carbon dots (C-dots), fullerene, and nanodiamonds (NDs), has captivated the materials industry [136].

Due to their chemical stability, mechanical strength, biological compatibility, and cost effectiveness, carbon-based materials have also gained interest as BTE scaffold materials in this aspect. Significant progress has been made in their applications in the context of BTE in recent decades, particularly as the 21st century has dawned [137].

3.4.1 Carbon Nanotubes Composite Materials as Scaffolds

Carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are allotropic, cylindrical nano-structured carbon. Although several additional forms of carbon nanotubes and their biocompatibility have been documented, CNTs are typically classified as single-wall carbon nanotubes (SWCNTs) or multiple walls carbon nanotubes (MWCNTs). SWCNTs tend to be curved rather than straight, with diameters that are usually between 1 and 2 nm, and are generally thinner than MWCNTs. The outer diameter of MWCNTs varies from 2 to 30 nm and is dependent on the number of layers. Although it can vary from 1 μm to a few centimeters, the length is usually in the micrometer range. Because of their distinctive structural, electrical, mechanical, electromechanical, and chemical characteristics, CNTs have been extensively studied for their potential use in regenerative medicine [138].

In a study, scaffolds made of CNT-reinforced 3D-printed polycaprolactone/β-tricalcium phosphate were developed and evaluated for their potential use in bone tissue engineering. In comparison to the polycaprolactone/β-tricalcium phosphate scaffold, the incorporation of CNTs significantly enhanced the mechanical properties, strength, and compressive modulus. Each scaffold exhibited a wide range of pore sizes (50–500 μm) and demonstrated high porosity of more than 70%. The scaffolds demonstrated remarkable biocompatibility, exhibiting hemolysis rates of less than 5% and outstanding cell viability [139].

In another work, innovative porous scaffolds were constructed by integrating varying concentrations of functionalized carbon nanotubes (fCNTs) into a matrix of hydroxyapatite (HAp) and silk fibroin (SF) and freeze-drying. The findings showed that the inclusion of fCNTs enhanced the proportion of SF’s β-sheet structure and promoted the in-situ development of HAp inside the scaffold. According to an evaluation of the scaffold’s properties, the addition of fCNTs considerably increased the compressive strength while reducing porosity and pore size. An increase in fCNT concentration is associated with an approximate decline in swelling and degradation rate, according to research on scaffold behavior in aqueous environments. All scaffolds, however, demonstrated a controlled and gradual release profile, underscoring their stability in maintaining fCNT release throughout time, regardless of the fluctuating fCNT levels. According to biological research, adding fCNTs up to 5 weight percent had no negative effects on cell adhesion or survival. The integration of fCNTs showed synergistic impacts on the scaffolds’ mechanical, biological, and physical characteristics [140].

Zhao et al. used carboxylated MWCNTs and bacterial cellulose (BC) to create composites with gradients of 0, 0.25, 0.5, and 1 wt%. The most suitable filler for polycaprolactone (PCL) was determined to be 1 weight percent MWCNT@BC based on its physicochemical characteristics, bioactivity, and osteogenic performance. With a compressive strength of 85.99 ± 10.03 MPa, the scaffold demonstrated improved mechanical characteristics and an appropriate scaffold design. Cellular tests showed that the scaffold has high osteoinductive performance, cell adhesion qualities, and biocompatibility. This was supported by a rat mandibular defect model that demonstrated outstanding biocompatibility and mandibular healing capabilities in vivo [141].

3.4.2 Graphene Based Composite Materials as Scaffolds

Graphene is a two-dimensional honeycomb structure made up of carbon atoms. The graphene family includes several derivatives such as graphene oxide (GO), reduced graphene oxide (RGO), graphene quantum dots (GQDs), graphene nanosheets, monolayer graphene, and few-layer graphene.

Graphene’s high aspect ratio, mechanical qualities, and electrical conductivity have made it appealing in a variety of applications. Graphene, Graphene based materials and composites are widely employed for significant biotechnological and biomedical applications, and they are also becoming stars in scientific domains other than biology and medicine. Numerous instances have been studied in recent years, and nearly all graphene derivatives and composites are being employed and tailored to provide unique delivery carriers for drug delivery, gene therapy, and theranostics [142].

In one study, graphene and graphene quantum dots (GQD) were integrated into PCL scaffolds and compared and assessed from mechanical, biological, thermal, and surface aspects. The mechanical and biological performance of PCL scaffolds was shown to be greatly enhanced by the inclusion of both materials at a weight percentage of less than 5%. In comparison to PCL/G scaffolds, PCL/GQD scaffolds demonstrated superior compressive strength under 3%wt. while retaining the same degree of biological performance [143].

Another investigation investigated the potential combination of an organic material (collagen) and an inorganic (nano)material (GO) as components of a bioink for vascular graft bioprinting. When compared to the control formulation, the collagen and GO-modified bioink showed better mechanical and viscoelastic qualities. Furthermore, the bioink exhibited complete in vitro biocompatibility and no harmful effects. Coculturing human muscle cells and endothelial cells (C2C12) revealed promise for vascular graft applications [144].

In another research, PCL/GO scaffolds were generated utilizing 3D bioprinting technology for meniscus cartilage repair. GO was added to PCL scaffolds to improve their mechanical, thermal, rheological, and bioactivity characteristics. According to rheological studies, GO considerably increased the yield shear and storage modulus, indicating greater elasticity and flow resistance. According to mechanical tests, scaffolds closely resembled the mechanical behavior of the native meniscus in terms of balance and ultimate tensile strength. While DSC research showed enhanced thermal stability with higher melting temperatures, FTIR analysis verified that GO was successfully integrated into the PCL matrix without compromising its chemical integrity. A roughened appearance of the surface that promotes cellular adhesion and proliferation was shown by SEM examination. DAPI-stained fluorescence microscopy on PCL/GO scaffolds demonstrated consistent nuclear distribution and improved cell adhesion. Cytotoxicity testing verified the PCL/GO scaffolds’ biocompatibility with fibroblast cells, while antibacterial assays showed greater inhibition zones against E. coli and S. aureus [145].

4 Trade-Offs between Biomaterials for 3D Printing