Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Diffusive Transfer between a Droplet and an Immiscible Oscillating Liquid in a Radial Hele-Shaw Cell

Laboratory of Vibrational Hydromechanics, Perm State Humanitarian Pedagogical University, Perm, 614990, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Ivan Karpunin. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Non-Equilibrium Processes in Continuous Media)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(3), 543-553. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.061163

Received 18 November 2024; Accepted 23 January 2025; Issue published 01 April 2025

Abstract

An experimental study of the diffusive mass transfer between a droplet and an oscillating immiscible liquid in a horizontal axisymmetric Hele-Shaw cell is carried out. The liquid oscillates radially in the cell. The transverse size of the droplet exceeds the cell thickness. The viscosities of the droplet and the surrounding liquid are comparable. Relevant effort is provided to design and test an experimental setup and validate a protocol for determining the mass transfer rate of a solute in a two-liquid system. In particular, fluorescent dye Rhodamine B is considered as the solute. A critical comparison of the situations with and without oscillation is implemented. A procedure is introduced and validated to determine the molecular and effective diffusion coefficients through evaluation of the growth of the diffusion zone width over time. It is shown that, in the presence of the liquid oscillations, there is a significant increase in the width of the zone in which Rhodamine B is present compared to the reference case with no oscillations. The oscillatory flow leads to an intensification of the solute diffusion due to intense time-averaged flows inside the droplet and the surrounding liquid and oscillations of the drop itself. The study is of significant practical interest with particular relevance to typical processes for liquid-liquid extraction.Keywords

Molecular diffusion is a fundamental process that enables the transfer of substances in various technological and biological systems. This transfer occurs in multiple media, including gases, liquids, and solids. The following examples illustrate the aforementioned diffusion: drying, adsorption, dissolution, impregnation, desorption, distillation, and reactions involving chemical changes [1–3]. Diffusion plays an important role in a number of practical applications, including fluid extraction and mass transfer in porous materials, semiconductor manufacturing, and the food industry [4–6]. Moreover, diffusion affects the metabolic processes occurring between the organism and the environment as well as between different cellular and tissue components within the organism [7–9]. It is, therefore, essential to study diffusion and develop methods of mass transfer intensification, both in relation to practical applications and from a fundamental perspective.

Droplet inclusions are a widely employed technique for the study of diffusion exchange within multicomponent media. The review [10] presents a discussion of the results of theoretical and experimental studies of droplets and multicomponent systems that have gradients in concentration. The study includes both the ‘seated’ droplets (maintaining their mean position) on a surface and the dynamics of droplet movement within the liquid. The diffusion rate depends on numerous conditions, both external and intrinsic to the diffusion system itself. A number of factors, including the physical and chemical properties of the interface, the presence of surfactant or nanoparticles at the interface, thermal effects, external oscillations, and the physical and chemical characteristics of the solvent (liquid droplet) or the solute, affect the diffusion rate. The oscillatory dynamics of systems with an interface in a Hele-Shaw cell are carried out for both low-viscosity fluids and fluids with high-viscosity contrast. The dynamics of the interface in a rectangular Hele-Shaw cell between miscible and immiscible fluids are studied in [11] and [12], respectively. It is revealed that fluid oscillations affect the interface stability and the mass transfer rate. The excitation of fluid oscillations in flat channels of different geometry by means of a hydraulic pump and a shaker is demonstrated to be an effective tool for external influence on various fluid systems. Fluid oscillations in a thin layer can cause the interface to become unstable [11,13]. For example, when a droplet is in an oscillating fluid, the droplet surface oscillates while the droplet drifts due to the inhomogeneity of the oscillatory motion of the ambient fluid [14]. The oscillatory flow gives rise to interface oscillations, which in turn give rise to intense time-averaged flow within the droplet. The effect of wall oscillations in an elastic sphere (deformable container) on the fluid velocity field within the sphere is examined in [15]. Here, the sphere plays the role of a droplet model. It is revealed that the intense time-averaged flow can significantly intensify mass transfer inside a drop in an oscillating flow.

The study aims to develop and validate an experimental setup and experimental technique for determining the mass transfer rate at the interface between two fluids. In [16], the authors previously described and tested a method for determining the diffusion mass transfer rate under conditions of a rectangular Hele-Shaw cell filled with water using the laser-induced fluorescence method, in other words, the spectroscopic method. The method is based on the determination of the concentration of fluorescent Rhodamine B in water by measuring the intensity of fluorescence emission and the rate of its diffusion in the liquid with time (on the rate of change of diffusion zone width). In the present study, diffusive mass transfer in a more complex system between a phase inclusion and the surrounding fluid in a radial Hele-Shaw cell is considered. A droplet of chlorobenzene or octanol is used as the phase inclusion, while distilled water plays the role of the surrounding fluid. The Rhodamine B dissolved in the droplet is used as a tracer dye to determine the mass transfer rate. In the absence of oscillations, the dye penetrates through the interface and then spreads in the radial and azimuthal directions due to molecular diffusion. When the surrounding liquid oscillates, the diffusion rate of the dye is determined by the amplitude of these oscillations.

The experimental setup (Fig. 1a) consists of several principal elements: an experimental cell, a linear motor with a power supply and control system, a hydraulic system, and a phase inclusion injection device. The linear motor 1 generates fluid oscillations within the cell. The motor rod undergoes linear translational oscillations in the horizontal plane. The rod is directly coaxially connected with the rod of a hydraulic pump 2, which consists of two volumes separated by a rubber membrane and operates on the ‘pull-push’ principle. The motor rod oscillations are transmitted to the separating membranes 3 by displacement of the pump membrane. The oscillatory motion of the liquid within the cell 4 is a consequence of the stretching and compression of the separating membranes. The cell is a circular layer confined between two glass plates of thickness

Figure 1: Scheme of the experimental setup (side view, a): 1—linear motor; 2—pump; 3—separation membranes; 4—radial axisymmetric Hele-Shaw cell; 5—linear motor driver and power supply; 6—computer; 7—droplet inclusion injection device; 8—laser; 9—digital camera. Schematic of a radial Hele-Shaw cell filled with a working fluid with droplet inclusion (top view, b)

The linear motor is managed by a driver, a power supply unit 5, and a computer 6. The frequency of the fluid oscillations

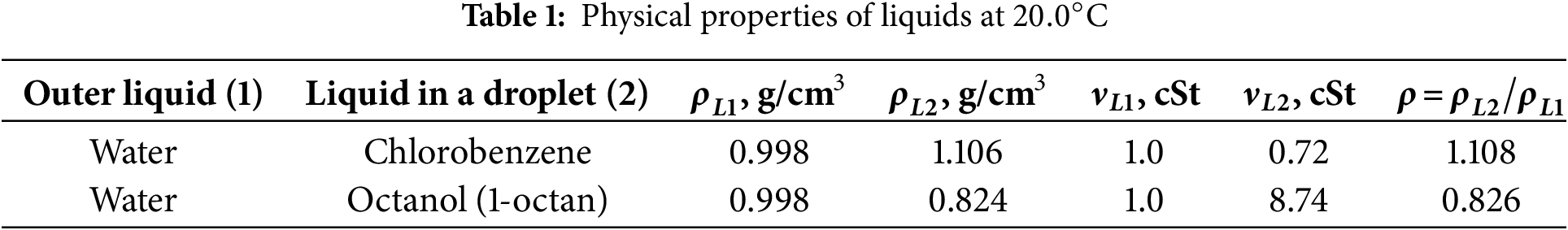

The droplet is made of chlorobenzene or octanol (1-octane). These liquids are immiscible with water and have different densities with respect to the latter. In particular, chlorobenzene has a higher density than water, whereas octanol has a lower density. The physical properties of the fluids are presented in Table 1.

A droplet is injected into the fluid layer volume by means of the injection device 7. Due to the specific feature of the droplet inclusion injection, its shape is elongated along the radius of the layer. In this case, the diametral size of the drop along the azimuthal direction is

3 Experimental Results and Discussion

3.1 Molecular Diffusion of Rhodamine B

The mass transfer rate of Rhodamine B from the droplet to the surrounding fluid in the absence of oscillations is determined by molecular diffusion. The droplet and the surrounding liquid are illuminated with a laser sheet, which allows for the observation of the fluorescence emission of both liquids and the control of the concentration of Rhodamine B within them. The liquid droplet undergoes radial stretching within the liquid layer as a consequence of the injection process. The elongated shape of the droplet along the radial direction of the radial Hele-Shaw cell leads to noticeable differences in its azimuthal and diametral dimensions

Figure 2: Photos of an octanol droplet containing Rhodamine B illuminated by the laser sheet: (a) azimuthal and (b) both azimuthal and radial directions

The primary objective of the experiments is to investigate the azimuthal propagation of solute under fluid oscillations. Fig. 3 illustrates the diffusion of Rhodamine B from chlorobenzene and octanol droplets into the surrounding water over time. A grayscale filter is applied to the photos for further image processing in order to obtain quantitative data. Each pixel in the grayscale image is identified by a color, with a numerical value ranging from 0 to 255 (from black and white, respectively). The maximum concentration of solute is associated with a white color while a zero concentration is associated with a black color. The study of diffusion is carried along the

Figure 3: Photos of a droplet of chlorobenzene (a, c) and octanol (b, d) illuminated with a laser sheet oriented in the azimuthal direction at (a) 900 s; (b) 300 s; (c) 10,800 s; (d) 7200 s

The gray value is measured in dependence on the

Figure 4: Dependence of the gray number on the x-coordinate at time

If it is assumed that the Rhodamine B diffuses only in the chosen direction, as it was described in [17], the second Fick’s law may be written in the following form:

where C is the concentration of dissolved fluorescent dye, x is the coordinate along which the diffusion of dye in water is considered and D is the diffusion coefficient. The corresponding boundary conditions are

The solution of Eq. (1) and the expression for calculating the concentration gradient of the solute are provided in [17,18]. Bushueva et al. [16] used the findings of [17,18] to develop an experimental technique for determining the molecular diffusion coefficient of Rhodamine B in water in a vertical rectangular cell. The basic principle of the technique is to determine the width of the diffusion zone

The technique described is applied to the liquids under investigation in this study. The square of the diffusion zone width as a function of time is determined for Rhodamine B diffusing from octanol and chlorobenzene droplets into the surrounding water. The size of the droplets is considerably smaller than the characteristic size of the liquid layer, and the diffusion of Rhodamine B can be considered uniform in all directions. Fig. 5 illustrates the dependence of

Figure 5: Dependence of the square of the diffusion zone width on time (parameter

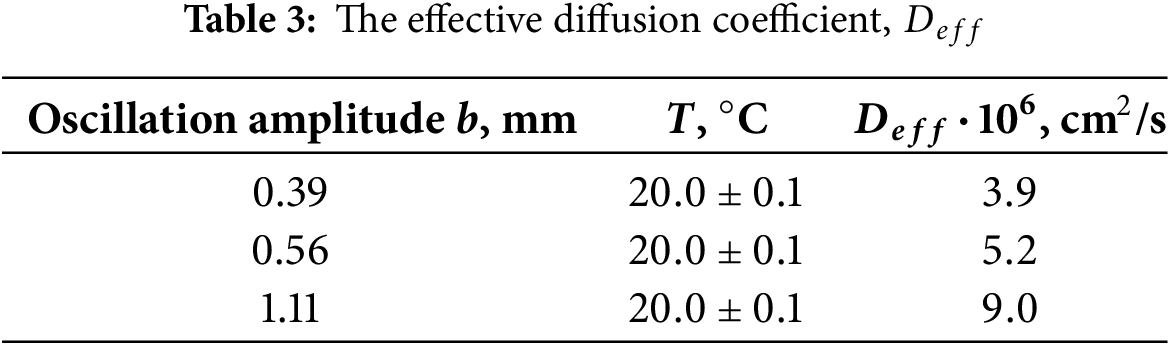

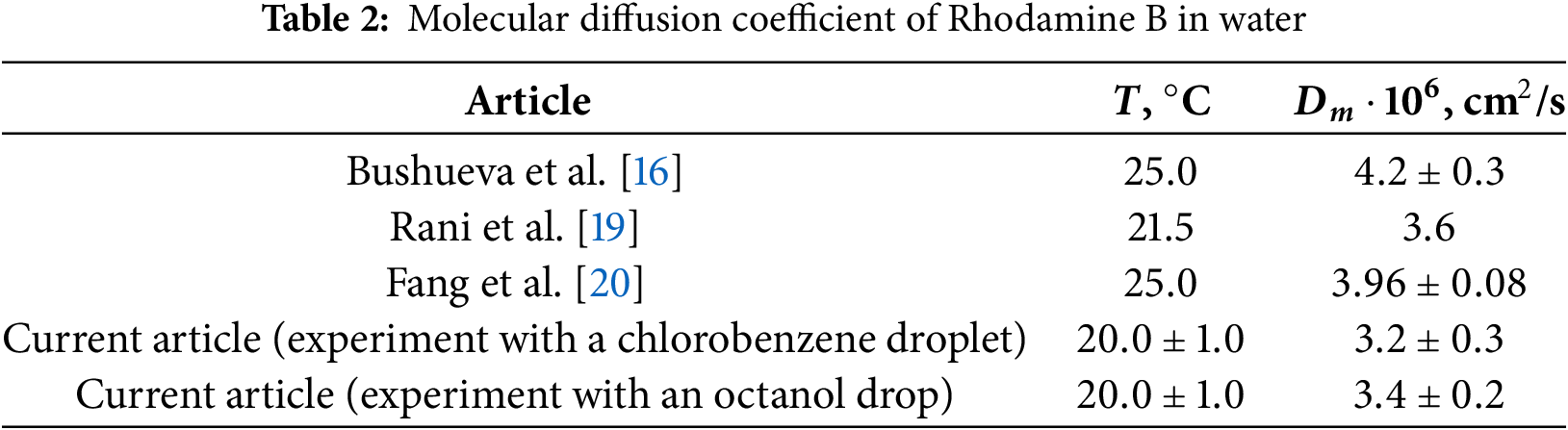

Table 2 presents values of the molecular diffusion coefficient of Rhodamine B in water. The diffusion coefficients calculated using expression (2) are in good agreement with the known values of the coefficient

It is demonstrated that this approach for determining the diffusion coefficient is applicable for quantifying the intensity of mass transfer between the droplet and the surrounding liquid in the absence of fluid oscillations. The discussed technique will be employed to calculate the effective diffusion coefficient of Rhodamine B from a droplet in a surrounding oscillating water.

3.2 Effective Diffusion of Rhodamine B

When water oscillates, the droplet remains in a fixed position and does not drift due to the formation of a more effective wetting layer on the glass walls of the cell than water. Simultaneously, the interface between the droplet and the surrounding water oscillates in the direction of water flow. The dynamics of fluid flow within a droplet with an oscillating surface is modelled in the experiments of Kozlov et al. [15]. It is demonstrated that the surface oscillations result in the generation of time-averaged flows, the structure and intensity of which are dependent on the parameters of surrounding liquid oscillations. The present study demonstrates that the oscillation of the ambient liquid enhances the mass transport of solute at the interface and increases the solute diffusion rate in the ambient liquid. This study examines the oscillatory dynamics of a droplet and mass transfer of Rhodamine B in the case of a droplet of octanol (Fig. 6). Once the surrounding water begins to oscillate, the droplet inclusion deforms while maintaining elongation along the cell radius. The experiments are conducted with a single droplet at a fixed frequency and a varying amplitude

Figure 6: Photos of the aqueous solution of Rhodamine B near the octanol droplet at a frequency

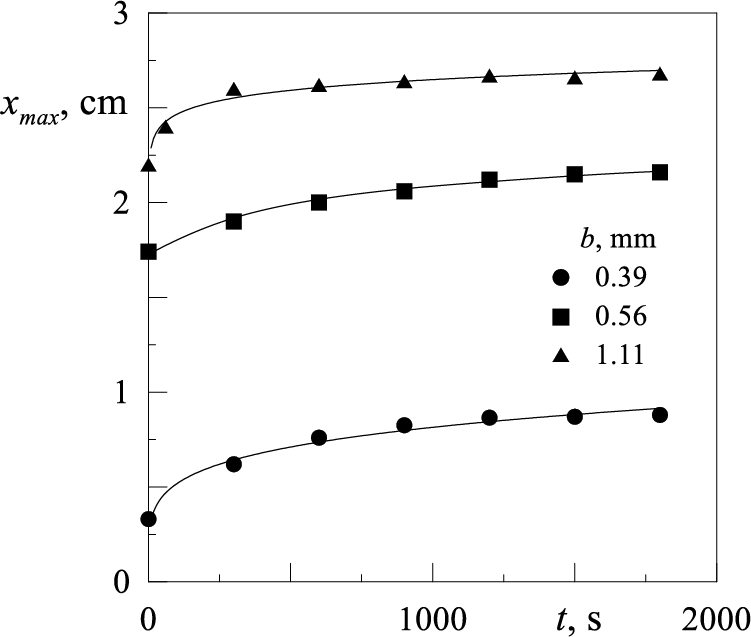

It can be assumed that the amplitude of radial oscillations is dependent on the radial coordinate within the cell, but not on the azimuthal one. Consequently, when the laser sheet is azimuthally oriented, the amplitude of water oscillations is approximately unchanged in the area of Rhodamine B concentration measurements. The diffusion of the dye is examined over time for given values of

The experiments show that the width

Figure 7: Dependence of the gray value on the coordinate

Thus, oscillating fluids provide additional solute transport to molecular diffusion. The combined effect of molecular diffusion and mass transport caused by fluid oscillations is quantified by the effective diffusion coefficient

Fig. 8 illustrates the temporal evolution of the width of the diffusion zone at different amplitudes of the fluid oscillations. The experiment is carried out in the three distinct phases. In the initial phase of the experiment, the oscillation amplitude is set to

Figure 8: Temporal evolution of the zone in which Rhodamine B is present at different amplitudes of fluid oscillations at a fixed frequency

The effective diffusion coefficients

Finally, it is demonstrated that the oscillations of the liquid near the droplet enhance the solute mass transfer due to the azimuthal time-averaged flow. In the future, the objective is to conduct a detailed study of mass transfer in relation to a number of key parameters, including oscillation frequency and amplitude, fluid viscosities, surface tension, and the intensity of the time-averaged flows.

The effect of the oscillatory flow on the mass transfer of a dye between a droplet and a surrounding liquid in a radial Hele-Shaw cell is studied experimentally. An experimental setup comprising a linear motor and a flat radial cell which permits the direct injection of a droplet inclusion into the fluid layer, has been designed and assembled. The experimental technique for determining the diffusion rate of Rhodamine B in water by measuring the width of the diffusion zone is validated. The experimental results demonstrate the intensification of solute mass transfer which is caused by intensive time-averaged flow in the liquid near the droplet. It is revealed that the solute mass transfer and the growth of the mixing zone increase with the oscillation amplitude. The experimental technique employed for the determination of the effective diffusion coefficient is examined in the context of the diffusion zone peripheral to the mixing zone. It is demonstrated that an increase in the amplitude of the fluid oscillations leads to a considerable widening of the diffusion zone and a marked enhancement in the rate of the solute mass transfer.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to express their gratitude to Professor Victor Kozlov for invaluable assistance in the preparation of this article.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Grant No. 23-11-00242).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Ivan Karpunin; data collection: Ivan Karpunin; analysis and interpretation of results: Ivan Karpunin; draft manuscript preparation: Ivan Karpunin and Denis Polezhaev; interpretation of results in the process of preparing responses to reviewers: Denis Polezhaev. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| Cell radius (mm) | |

| Radial size of the observation area (mm) | |

| Fluid layer thickness (mm) | |

| Fluid oscillation amplitude (mm) | |

| Coordinate (cm) | |

| Time (s) | |

| Acceleration of gravity (m/s2) | |

| Temperature (°C) | |

| Droplet diameter (mm) | |

| Molecular diffusion coefficient (cm2/s) | |

| Effective diffusion coefficient (cm2/s) | |

| Oscillation frequency (Hz) | |

| Greek Symbols | |

| Liquid density (g/cm3) | |

| Kinematic liquid viscosity (cSt) | |

| Relative density (–) | |

| Diffusion zone width (cm) | |

| Concentration change (–) | |

References

1. Bennamoun L, Belhamri A, Mohamed AA. Application of a diffusion model to predict drying kinetics changes under variable conditions: experimental and simulation study. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2009;5(2):177–92. doi:10.3970/fdmp.2009.005.193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rudobashta SP, Kartashov EM. Chemical technology: diffusion processes. Moscow: Yurait Publishing House; 2024 (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

3. Abdeljabar R. On the behavior of an interface under molecular diffusion: a theoretical prediction and experimental study. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2009;5(2):193–210. doi:10.3970/fdmp.2009.005.193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bokhary A, Leitch M, Liao BQ. Liquid-liquid extraction technology for resource recovery: applications, potential, and perspectives. J Water Process Eng. 2021;40:101762. doi:10.1016/j.jwpe.2020.101762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Dentz M, Hidalgo JJ, Lester D. Mixing in porous media: concepts and approaches across scales. Transport Porous Med. 2023;146(1):5–53. doi:10.1007/s11242-022-01852-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Cussler EL. Diffusion: mass transfer in fluid systems. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

7. Stein W. Transport and diffusion across cell membranes. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2012. [Google Scholar]

8. Kapellos GE, Alexiou TS, Payatakes AC. A multiscale theoretical model for diffusive mass transfer in cellular biological media. Math Biosc. 2007;210(1):177–237. doi:10.1016/j.mbs.2007.04.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Mogre SS, Brown AI, Koslover EF. Getting around the cell: physical transport in the intracellular world. Phys Biol. 2020;17(6):061003. doi:10.1088/1478-3975/aba5e5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Lohse D, Zhang X. Physicochemical hydrodynamics of droplets out of equilibrium. Nat Rev Phys. 2020;2(8):426–43. doi:10.1038/s42254-020-0199-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Bushueva A, Vlasova O, Polezhaev D. Averaged dynamics of fluids near the oscillating interface in a Hele-Shaw cell. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2024;20(4). doi:10.32604/fdmp.2024.048271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Kozlov VG, Vlasova OA, Dyakova VV. Stability of the interface of liquids oscillating in a vertical flat channel. Interfacial Phenom Heat Transf. 2024;12(1). doi:10.1615/InterfacPhenomHeatTransfer.v12.i1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kozlov V, Karpunin I, Kozlov N. Finger instability of oscillating liquid-liquid interface in radial Hele-Shaw cell. Phys Fluids. 2020;32(10):102102. doi:10.1063/5.0018541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Karpunin IE, Kozlov VG, Kozlov NV. Influence of high-frequency fluid oscillations on viscous droplet inclusion in a Hele-Shaw cell. Convective Flows. 2019;9:36–51 (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

15. Kozlov VG, Sabirov RR, Subbotin SV. Steady flows in an oscillating spheroidal cavity with elastic wall. Fluid Dyn. 2018;53(2):189–99. doi:10.1134/S0015462818020118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bushueva A, Polezhaev D. Mass transfer of solute in an oscillating flow in a two-dimensional channel. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(4):045150. doi:10.1063/5.0204206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Rashidnia N, Balasubramaniam R, Kuang J, Petitjeans P, Maxworthy T. Measurement of the diffusion coefficient of miscible fluids using both interferometry and Wiener’s method. Int J Thermophys. 2001;22:547–55. doi:10.1023/A:1010735117408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ray E, Bunton P, Pojman JA. Determination of the diffusion coefficient between corn syrup and distilled water using a digital camera. Am J Phys. 2007;75(10):903–6. doi:10.1119/1.2752819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Rani SA, Pitts B, Stewart PS. Rapid diffusion of fluorescent tracers into Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms visualized by time lapse microscopy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(2):728–32. doi:10.1128/AAC.49.2.728-732.2005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Fang X, Xuan Y, Li Q. Experimental investigation on enhanced mass transfer in nanofluids. Appl Phys Lett. 2009;95(20). doi:10.1063/1.3263731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools