Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Review of Methods for “Pump as Turbine” (PAT) Performance Prediction and Optimal Design

1 School of Mechanical Engineering, Hunan University of Technology, Zhuzhou, 412007, China

2 College of Information Engineering, Quzhou College of Technology, Quzhou, 324000, China

3 Quzhou Academy of Metrology and Quality Inspection, Quzhou, 324024, China

4 College of Mechanical Engineering, Quzhou University, Quzhou, 324000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Yanjuan Zhao. Email: ; Lianghuai Tong. Email:

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(6), 1261-1298. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.064329

Received 12 February 2025; Accepted 21 April 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

The reverse operation of existing centrifugal pumps, commonly referred to as “Pump as Turbine” (PAT), is a key approach for recovering liquid pressure energy. As a type of hydraulic machinery characterized by a simple structure and user-friendly operation, PAT holds significant promise for application in industrial waste energy recovery systems. This paper reviews recent advancements in this field, with a focus on pump type selection, performance prediction, and optimization design. First, the advantages of various prototype pumps, including centrifugal, axial-flow, mixed-flow, screw, and plunger pumps, are examined in specific application scenarios while analyzing their suitability for turbine operation. Next, performance prediction techniques for PATs are discussed, encompassing theoretical calculations, numerical simulations, and experimental testing. Special emphasis is placed on the crucial role of Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD) and internal flow field testing technologies in analyzing PAT internal flow characteristics. Additionally, the impact of multi-objective optimization methods and the application of advanced materials on PAT performance enhancement is addressed. Finally, based on current research findings and existing technical challenges, this review also indicates future development directions; in particular, four key breakthrough areas are identified: advanced materials, innovative design methodologies, internal flow diagnostics, and in-depth analysis of critical components.Keywords

The use of pumps as turbines has been explored and studied since the 1930s, a practice that now boasts over ninety years of history. Researchers such as Thoma D were the first to recognize that by reversing the operation direction of a pump, it could be transformed into an effective hydraulic power generation device for the recovery and utilization of energy [1].

Over time, PAT technology has garnered significant attention due to its unique advantages [2,3]. It is not only relatively low-cost and easy to install and maintain but also capable of efficiently recovering residual pressure from water resources. This offers new solutions in various fields including small-scale hydropower stations, surplus pressure recovery in urban water supply systems, agricultural irrigation, and drainage. These characteristics make PAT technology one of the crucial tools for promoting sustainable development.

For instance, enterprises and research institutions in Italy and Germany have developed various models of PAT equipment and successfully applied them in numerous real-world scenarios [4–6], demonstrating their significant effects in enhancing energy efficiency and reducing environmental pollution [7–9].

In recent years, an increasing number of research institutions and companies have engaged in the research, development, and practical application of PAT technology [3,10–12], striving to address energy and environmental challenges through technological innovation [13–16]. Currently, PAT technology has begun to be applied in some small and medium-sized hydraulic engineering projects, showcasing promising application prospects and development potential [17].

With the continuous growth in energy demand and enhanced environmental protection awareness nowadays, the study and application of PAT technology are particularly important. As an efficient energy recovery technology, PAT not only significantly improves energy utilization efficiency and reduces energy waste [18] but also effectively lowers carbon emissions, contributing to the establishment of a clean, low-carbon, safe, and efficient energy system. By converting fluid pressure energy into mechanical energy and then into electrical energy or other forms of energy, this technology is especially suitable for use in hydropower stations and the recovery of residual pressure in industrial processes.

The core of PAT technology lies in reversing a pump, originally used for fluid transport, under specific conditions to recover energy from the fluid and convert it into mechanical or electrical energy [19–21]. This technology is not only suitable for recovering residual energy from tailwater in hydropower stations [22,23] but can also be widely applied in various fields such as industrial recirculating water systems [24], urban water supply networks [25], and irrigation systems [26]. In hydropower stations, PAT can recover residual energy from tailwater, enhancing the overall efficiency of the station, and reducing energy waste [22]. In industrial recirculating water systems, PAT can recover energy from high-pressure water flows, converting it into electrical energy to reduce power consumption and lower operating costs [27]. In urban water supply networks, PAT can generate electrical energy by utilizing pressure differences, thereby reducing the energy consumption of the water supply system [28,29]. In irrigation systems, PAT can recover residual pressure after irrigation, improving the efficiency of water resource utilization and reducing energy consumption [30,31]. In mine drainage systems, PAT can recover energy from mine drainage, lowering operational costs and improving economic benefits [32].

Despite the significant application potential and economic benefits demonstrated by PAT technology, further in-depth research is required in hydraulic optimization design and internal flow characteristics [33,34]. Currently, there are numerous challenges in optimizing PAT performance under different operating conditions, understanding internal flow mechanisms, and addressing wear and corrosion issues. For instance, how to improve the efficiency of PAT under low flow and high head conditions through the optimization of impeller design and flow passage structure [35,36]; how to reveal the physical mechanisms of complex flows inside PAT through numerical simulations and experimental studies, providing theoretical support for its design [37,38]; and how to develop new materials and surface treatment technologies that resist wear and corrosion, thereby extending the service life of PAT [39,40], are all critical issues that need to be addressed urgently.

By conducting in-depth research on hydraulic optimization design and internal flow characteristics of PAT, it is possible not only to further enhance its performance and reliability but also to provide significant support for technological innovation in related fields. For example, through optimized design, the adaptability and stability of PAT under various operating conditions can be improved [36,41], thus broadening its application scope. By thoroughly investigating internal flow characteristics [37–39,42], new design concepts and methods can be discovered, promoting continuous advancements in PAT technology. Additionally, the application of new materials and surface treatment technologies [43] can significantly improve the durability and economy of PAT, reduce maintenance costs, and strengthen its market competitiveness. Therefore, the study of PAT technology holds substantial socioeconomic value and deserves focused attention and investment in the current and future periods.

This review primarily examines pump selection, performance prediction, and optimization design aspects of PAT through original published articles. It extensively discusses methodologies for selecting pumps suitable for PAT, performance prediction models for such pumps, and objectives for optimizing pump design, aiming to offer a comprehensive understanding of the current progress in PAT technology.

Since most pump manufacturers do not provide reverse operation performance data, this poses a challenge for selecting pumps to be used as turbines [44,45]. However, proper selection is crucial when using a pump as a turbine, even though pumps and turbines share structural similarities, their working mechanisms and application scenarios are distinctly different. The role of a pump is to convert mechanical energy into fluid pressure energy, whereas a turbine converts the kinetic or pressure energy of a fluid into mechanical energy. Therefore, when choosing a pump to function as a turbine, it is essential to thoroughly consider its performance characteristics and applicable conditions during reverse operation. When a pump is used as a turbine, its design features directly impact the efficiency of energy conversion.

Centrifugal pumps used as turbines are particularly popular in micro-hydropower stations and the chemical industry, mainly due to their cost-effectiveness, availability, simple design, and ease of operation and maintenance. In remote areas or small hydropower projects, PATs are utilized to convert water flow energy into electricity. Given that they do not require special customization and have relatively low production costs, they are highly suitable for such projects. For instance, in countries like Nepal with unstable power grids, PATs are widely used in micro-hydropower stations as backup power sources, especially in mountainous regions far from urban power grids [46]. Stephen et al.’s research shows that PATs are not only cost-effective but also capable of efficiently utilizing water resources [47]. In the petrochemical industry, PATs are employed to recover high-pressure residual heat energy; multi-stage PATs can cater to a broader range of energy recovery needs and application scenarios. Li et al. verified the efficiency and stability of PATs in such industrial applications through numerical simulations and experimental testing [48]. Additionally, Yang et al. pointed out that in hydraulic systems, PATs can replace pressure-reducing valves for pressure regulation [49]. Tahani et al. emphasized the economic and mechanical performance advantages of using centrifugal pumps as turbines in water supply networks, making them a highly valuable option [50].

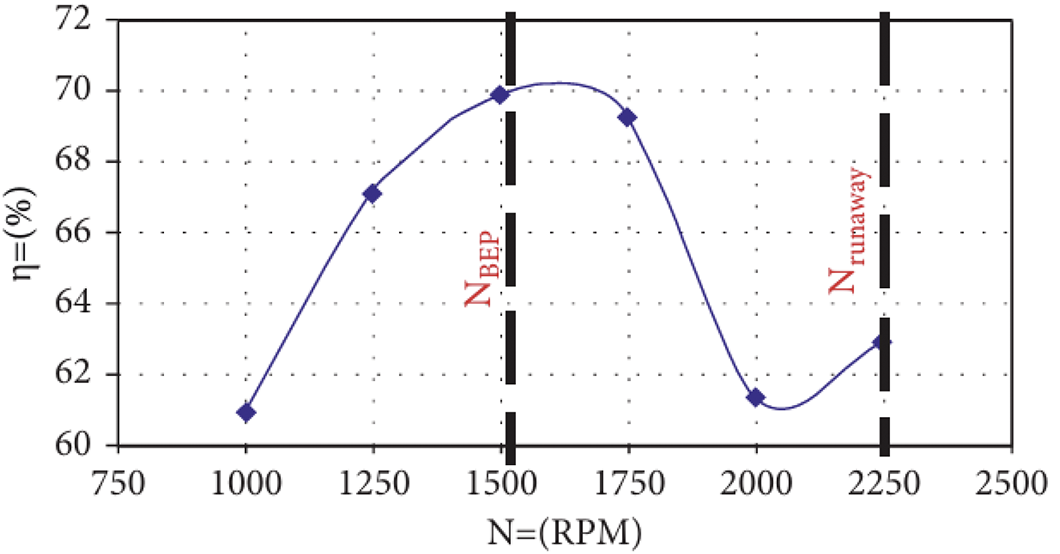

Du et al. tested the performance of a centrifugal pump specified at Q = 1.2 m3/s as a PAT within a speed range of 1000 to 2000 rpm, finding that the performance was optimal in this range [51]. Fig. 1 shows the PAT performance curve tested by Du et al. The results indicate that the peak efficiency of the PAT is achieved when operating between 1500 and 1750 rpm, after which the efficiency begins to decline. Overall, the selected PAT can achieve favorable operating conditions when run between 1000 and 2000 rpm. In summary, using centrifugal pumps as part of small-scale hydropower projects showcases their unique advantages.

Figure 1: PAT speed-efficiency curve Adapted with permission from Ref. [51], Copyright ©2021, Complexity publishing

Due to their unique capabilities, twin-screw pumps can replace traditional control valves in specific applications, enabling the recovery of wasted energy within systems, especially when operating in turbine mode. Research by Ali Moghaddam indicates that using twin-screw pumps as turbines for high-viscosity fluids can potentially recover up to about 50% of the energy, preventing this portion of energy from being dissipated through conventional control valves [52,53]. This demonstrates that twin-screw pumps are highly suitable as turbines for handling high-viscosity fluids, not only improving the system’s energy utilization efficiency but also reducing energy loss.

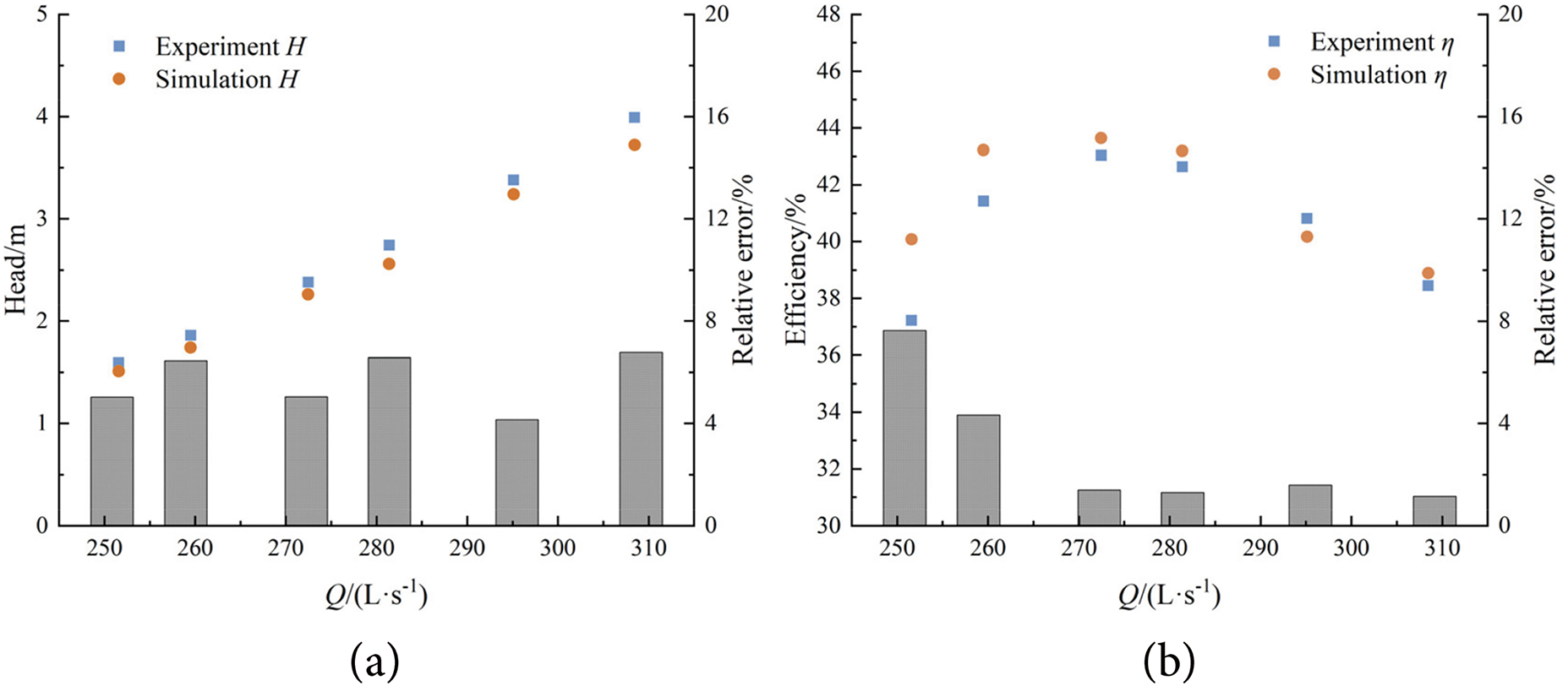

Yang et al.’s research shows that axial-flow pumps used as turbines exhibit high efficiency and large flow rates under low head conditions, making them particularly suitable for hydropower stations in plain areas [44]. They also highlight the advantages of axial-flow pumps, which are not restricted by terrain and have lower costs [54]. Fig. 2 presents the test data of an axial-flow pump PAT from Fan Yang’s study. The results indicate that, within a low head range of 1 to 4 m and a high flow rate range of 250 to 310 L/s, the PAT efficiency remains above 36%, with a peak efficiency of 43% to 44% at a flow rate of 270 L/s. This demonstrates that axial-flow pumps used as turbines can maintain high efficiency under conditions of low head and high flow rates.

Figure 2: Performance curve of the axial-flow PAT: (a) head; (b) efficiency Adapted with permission from Ref. [44], Copyright ©2022, Processes publishing

Chen’s research further indicates that in tidal power stations, axial-flow pumps used as turbines can operate bidirectionally according to tidal changes, significantly enhancing energy utilization efficiency [55]. This demonstrates that axial-flow pumps are highly suitable as turbines in low head environments, not only effectively utilizing natural resources but also adapting to environmental changes, thereby improving the system’s flexibility and economy.

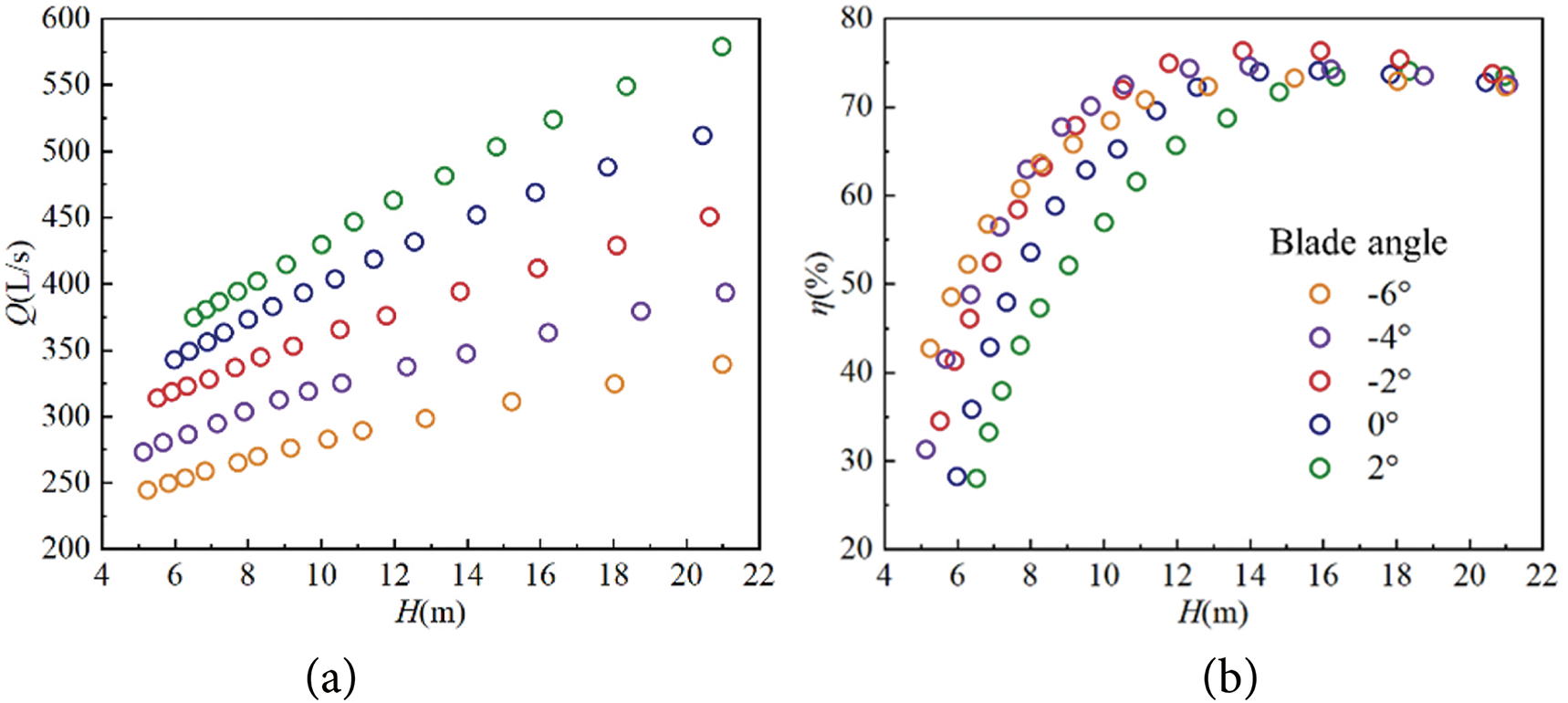

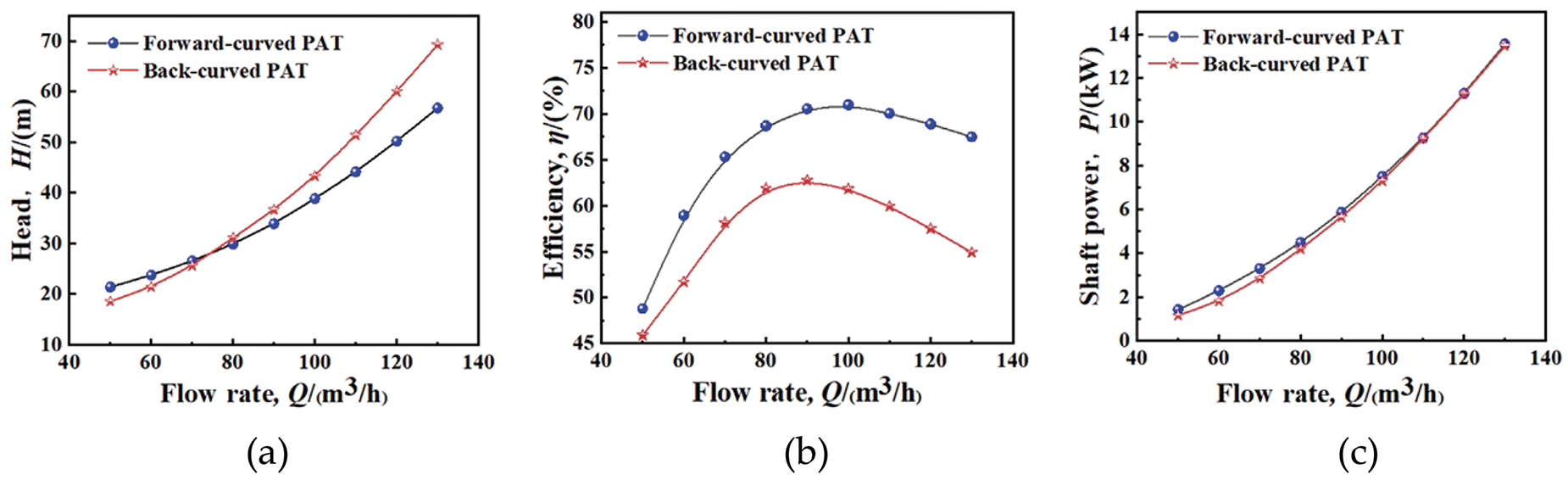

In certain industrial application scenarios, mixed-flow pumps used as turbines can recover waste thermal energy or pressure energy, thereby enhancing energy utilization efficiency. For instance, in chemical plants and oil refineries, mixed-flow pumps can effectively recover energy from high-pressure gases [56]. Additionally, the use of mixed-flow pumps as turbines in micro-hydropower stations has been extensively studied. These pumps are suitable for environments with high head and high flow rates, efficiently converting hydraulic energy into electrical energy [15]. As shown in Fig. 3, which presents the characteristic curve of a mixed-flow pump tested by Shuaihao Lei et al., it was found that under conditions of high flow rates (above 400 L/s but below 600 L/s) and high heads (above 12 m but below 22 m), the mixed-flow pump exhibited very high efficiency, around 75%.

Figure 3: Mixed-flow pump PAT characteristics: (a) H-Q curves; (b) H-η curves Adapted with permission from Ref. [15], Copyright ©2024, Energy publishing

The application of mixed-flow pumps in tidal power stations also demonstrates their potential [57], capable of adapting to varying head conditions caused by tidal changes, thus improving energy conversion efficiency. Simultaneously, mixed-flow pumps are one of the ideal choices for micro hydropower plants [58], suitable for scenarios requiring compact, low-cost solutions. Chen studied the hydraulic model of a mixed-flow pump used as a turbine in a pumped storage power station. The results showed that during high water levels, increasing the rotational speed helps enhance energy recovery efficiency; whereas during low water levels, the opposite effect occurs [59]. This indicates that mixed-flow pumps perform more effectively under high water level conditions. In summary, as a multi-functional energy recovery device, mixed-flow pumps have demonstrated unique value and advantages across various applications.

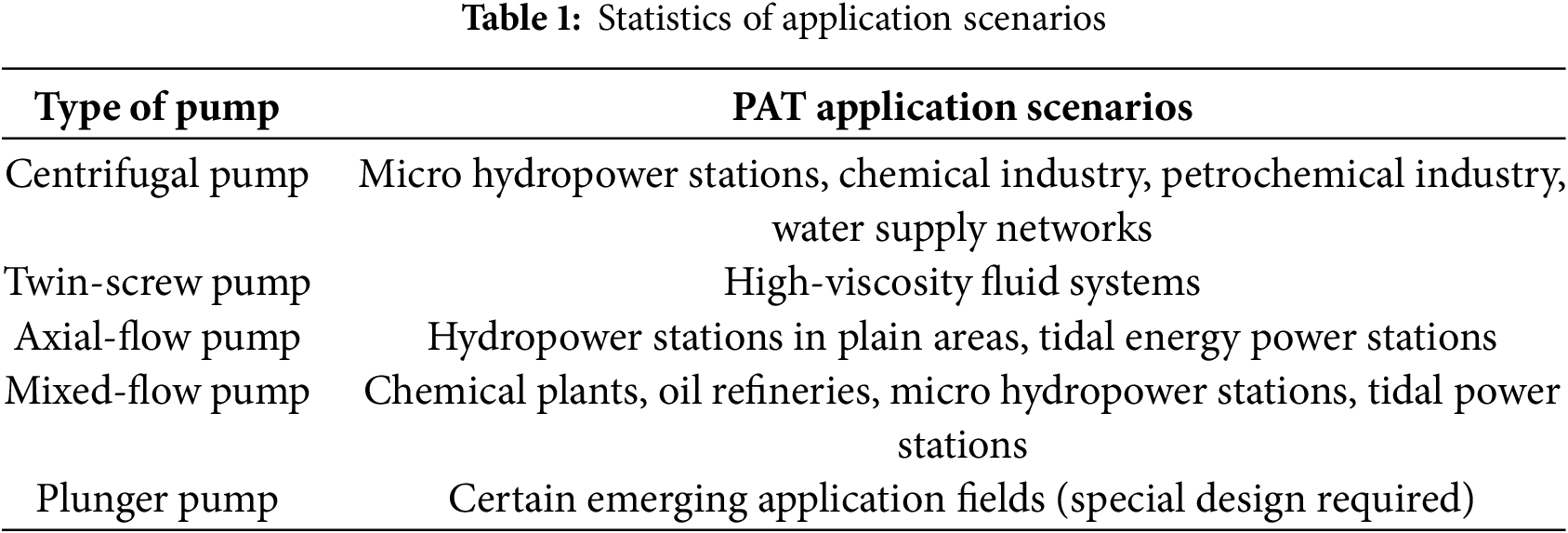

Zielinski et al. proposed a new possibility of using a novel low-speed radial piston pump as part of the hydrostatic transmission in small hydropower stations [60], an innovative idea that expands the application scope of pumps as energy conversion devices. Therefore, when selecting pumps as turbines, it is essential to fully consider the type and design characteristics of the pump based on specific application requirements. This means carefully assessing the specific conditions of the target application before deciding which type of pump to use as a turbine, including but not limited to factors such as head height, flow rate demand, and working medium properties, to ensure that the selected pump can operate efficiently and stably under predetermined conditions. The application scenarios of various types of pumps are summarized in Table 1.

Based on the described application scenarios, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Centrifugal pumps could become the preferred option for small-scale hydropower projects and industrial energy recovery applications due to their cost-effectiveness, availability, simple design, and ease of operation and maintenance.

(2) In situations involving high-viscosity fluids, twin-screw pumps may exhibit significant energy recovery capabilities, contributing to improved overall energy utilization efficiency of the system.

(3) Axial-flow pumps are particularly suitable for low head applications, such as hydropower stations in plain areas and tidal energy power stations. Their high efficiency and adaptability to environmental changes could bring notable economic benefits to these fields.

(4) Mixed-flow pumps likely perform excellently under conditions of high head and high flow rates, making them suitable for various energy recovery scenarios, including waste heat recovery in chemical plants, micro hydropower stations, and tidal power stations. They possess considerable flexibility and adaptability.

(5) The use of plunger pumps as turbines might still be in the exploration phase. However, in certain specific conditions, such as those requiring precise control and hydrostatic transmission, they may present new possibilities.

Performance prediction is a crucial aspect of the design and optimization process for both centrifugal pumps and turbines, helping to ensure that equipment achieves expected efficiency and reliability during actual operation. PAT performance prediction is mainly achieved through three methods: theoretical calculations, numerical simulations (CFD), and experimental testing [61]. Each method has its unique advantages and is often used in combination to obtain the most accurate results.

This method is based on the fundamental principles of fluid mechanics and empirical formulas. For centrifugal pumps, this may involve applying Euler’s equation, Bernoulli’s equation, and others to estimate key parameters such as pump head and efficiency. For turbines, it involves more extensive application of thermodynamic laws, such as the ideal gas state equation and the law of conservation of energy. Although theoretical calculations can provide a quick preliminary estimate of performance, the results may differ from actual conditions because simplified models are used for ease of solving.

Performance prediction for PATs utilizes the Best Efficiency Point (BEP) and Specific Speed [17]. Typically, selecting an appropriate pump for use as a PAT begins with performance prediction based on two key conversion factors, q and h, which represent the capacity ratio and head ratio at the best efficiency point between the turbine and pump modes [62–64], respectively.

q is the ratio of the turbine capacity to the pump capacity at the BEP:

h is the ratio of the head between the turbine and the pump:

For the above two equations, QT and HT represent the flow rate and head in turbine mode, while QP and HP represent the flow rate and head in pump mode.

Then, the calculation of the specific speed can be carried out. The specific speed of a pump is a dimensionless parameter that describes the relationship between the pump’s geometry and its hydrodynamic characteristics, which is crucial for pump design, selection, and performance prediction. Through specific speed, engineers can select the most suitable pump type based on application requirements and predict its performance under various operating conditions, including changes in flow rate, head, and efficiency. Maintaining the same specific speed ensures similar performance characteristics when scaling the pump design. Additionally, when using a pump in reverse as a turbine for energy recovery, the specific speed helps identify the most appropriate pump type and predict its performance. As mentioned in [63], the formula for calculating specific speed is as follows:

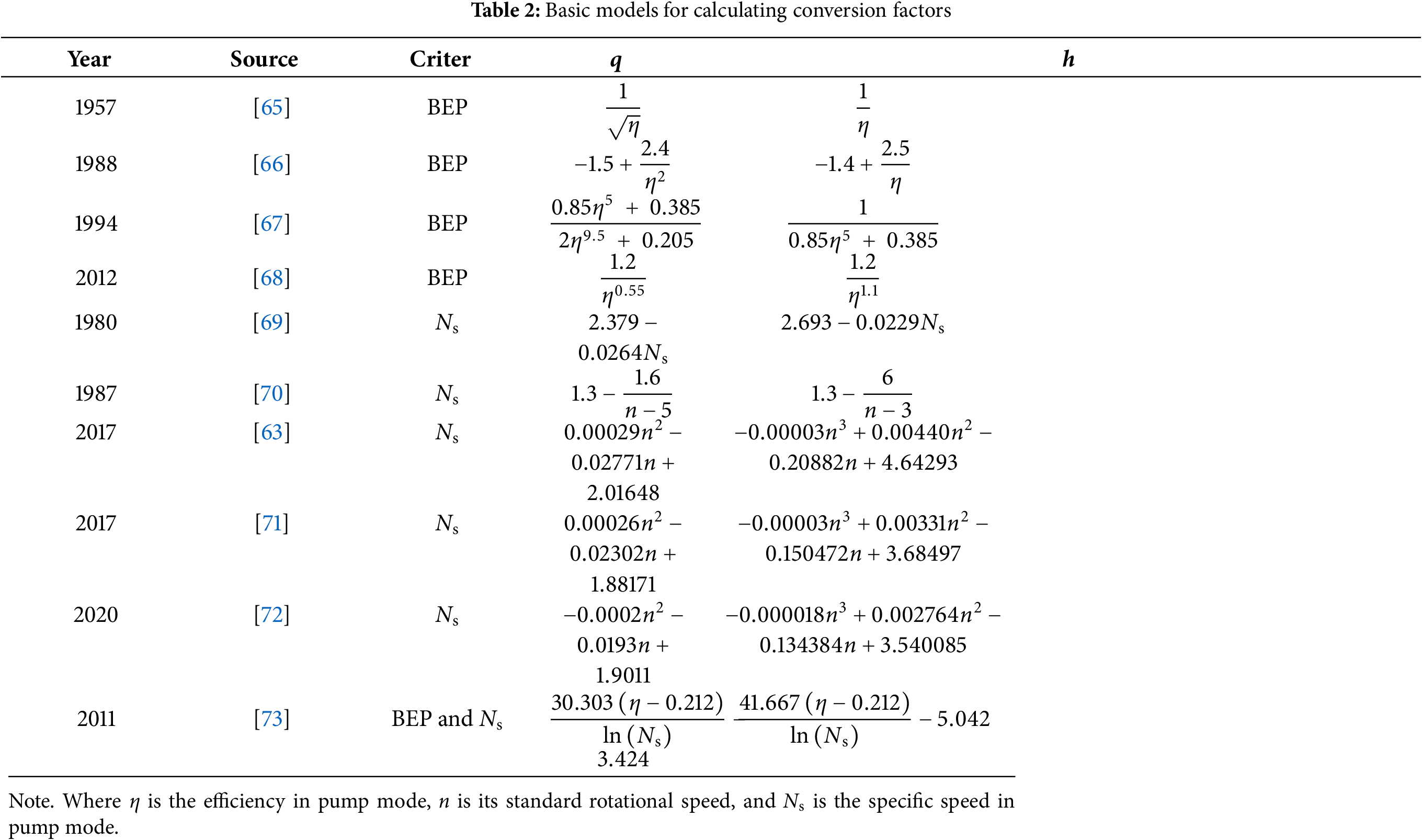

Based on this, many scholars have contributed to the performance prediction of PATs from this perspective, as shown in Table 2.

The empirical formulas obtained by these scholars are basically derived from fitting a large amount of data, primarily using efficiency and rotational speed to calculate the conversion factors q and h. Although the formulas differ, the prediction results are relatively accurate. This is because different formulas are suitable for predicting the performance of PATs with different parameters.

Although theoretical calculations can provide a quick preliminary estimate of performance, the results may deviate from actual conditions because simplified models are used for ease of solving. Additionally, since predictions are made using formulas, this approach cannot account for various factors such as parameter variations, material properties, manufacturing tolerances, and changes in operating conditions. These inadequately addressed factors can lead to a decrease in prediction accuracy.

With the advancement of technology, using machine learning methods for prediction has become particularly important. Machine learning methods can automatically identify patterns and relationships from large amounts of historical data without relying on specific physical models or assumptions. By training algorithms, machine learning models can capture complex and nonlinear system behaviors, thereby providing more accurate predictions. Additionally, machine learning is capable of handling multi-variable inputs, meaning it can simultaneously consider the impact of various factors mentioned above, thus improving the accuracy and reliability of predictions.

Gabriella Balacco utilized traditional BEP and specific speed performance prediction methods as a basis, employing Artificial Neural Networks (ANN) and Evolutionary Polynomial Regression (EPR) to predict the performance of PATs. A comparison highlighted the advantages of machine learning methods. Although ANN has the inherent limitation of not being able to provide a clearly defined formula, it offers users the possibility to identify the optimal model structure and emphasizes the correlation between the most influential input factors and outputs [74].

This does not mean that machine learning is superior to polynomial regression methods. Gabriella Balacco also noted that using one method does not preclude the other, as Evolutionary Polynomial Regression not only provides clear formulas but also achieves good prediction accuracy [74]. Therefore, these methods can be combined; for instance, Painter R proposed a generalized predictive model for comprehensive performance studies of PATs in micro-hydropower applications. This model integrates Ensemble Regression Models (ERM) with polynomial regression to predict the BEP and the complete characteristic curves [75]. Specifically, machine learning algorithms were used to predict the BEP of PATs, followed by the development of polynomial equations to predict the head and efficiency curves of PATs. This illustrates that combining machine learning algorithms with regression methods can enhance both the efficiency and accuracy of models. It also indicates that early performance prediction methods based on BEP and specific speed, as well as recent approaches based on hydraulic loss modeling, are not obsolete. These traditional methods provide a foundation for the application of machine learning in PAT performance prediction.

Computational Fluid Dynamics is a powerful tool that solves complex fluid flow problems through numerical methods. During the design phase of pumps or turbines, engineers can utilize CFD software to conduct detailed simulations and analyses of internal flow fields, thereby obtaining more accurate information on pressure distribution, velocity distribution, and vortex conditions. This detailed data not only aids in optimizing the design but also helps predict equipment performance under various operating conditions. Compared to theoretical calculations, CFD can handle more complex geometries and boundary conditions, providing more precise prediction results.

3.2.1 Applicability of Turbulence Models

Selecting an appropriate turbulence model is crucial for effective numerical calculations. According to references, there are several turbulence models available, each with its characteristics and applicable scenarios:

(1) Standard k-ε (k-epsilon) model: This is a two-equation turbulence model that describes turbulence characteristics using turbulent kinetic energy (k) and turbulent dissipation rate (ε).

(2) RNG k-ε (Re Normalization Group k-epsilon) model: An improved version of the standard k-ε model based on renormalization group theory, providing better prediction capabilities near walls.

(3) Realizable k-ε model: Ensures physical realizability of stress ratios, i.e., guarantees the positive definiteness of second moments, making it another enhanced k-ε model.

(4) SST k-ω (Shear Stress Transport k-omega) model: Combines the advantages of the k-ω model in free shear flows and the good behavior of the k-ε model near walls, suitable for complex flows.

(5) Standard k-ω (k-omega) model: This model uses turbulent kinetic energy (k) and specific dissipation rate (ω), generally offering better predictive capability for separated flows.

(6) SST-CC (Curvature Correction) model: Based on the SST k-ω model with added curvature correction to improve the capture of rotational and curvature effects.

(7) S–A (Spalart–Allmaras) model: A one-equation model particularly suitable for aerospace applications due to its relative simplicity and lower dependency on mesh quality.

(8) Wilcox k-ω model: Developed by David Wilcox, this k-ω model aims to achieve better results by adjusting constants and formulas.

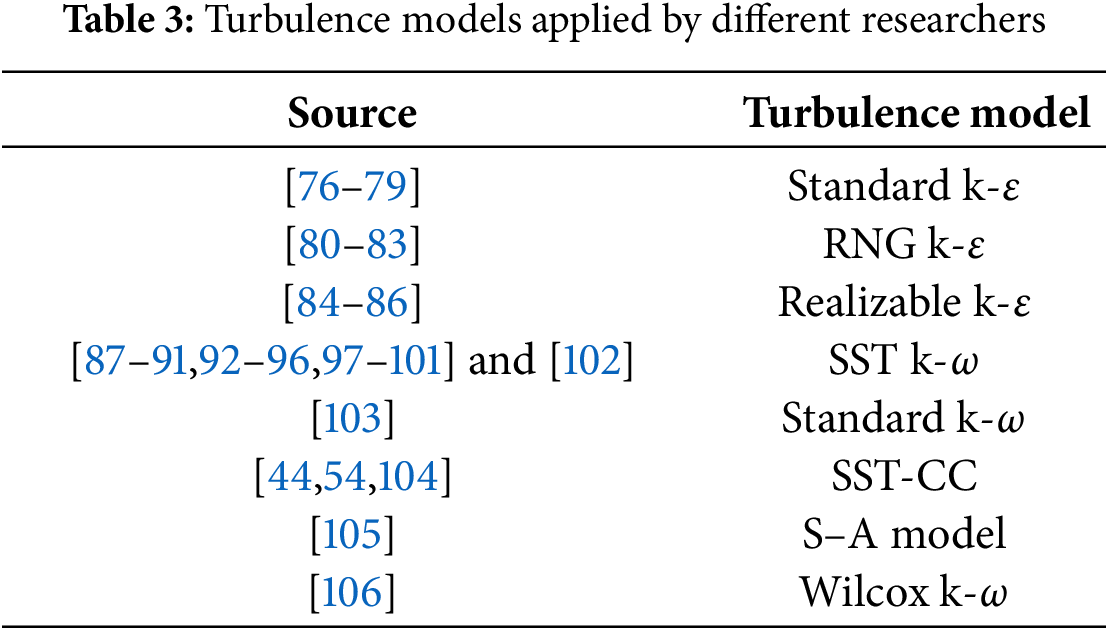

Depending on different research needs and specific applications, researchers will choose the most suitable turbulence model for CFD analysis. Table 3 summarizes and statistically analyzes the turbulence models applied by various researchers in their numerical calculations of PATs.

Based on the above statistics and literature analysis, engineers and researchers are presented with a diverse toolbox when selecting turbulence models for CFD analysis, each model possessing unique characteristics and applicable scenarios. The Standard k-ε model is widely used in the preliminary design phase due to its simple structure and low computational cost [107], but it may not accurately capture complex flow features common in PATs, such as separated flows or free shear flows. The improved RNG k-ε model, based on renormalization group theory, offers better prediction capabilities near walls, which is crucial for understanding boundary layer behaviors, especially close to blade surfaces. The Realizable k-ε model ensures physical realizability of stress ratios, making it suitable for problems involving rotational effects or strong curvature effects, which are particularly important in PAT design due to the typically complex geometries and flow paths of these devices.

The SST k-ω model combines the good description capability of the k-ω model for free shear flows and the performance of the k-ε model near walls, making it highly suitable for simulating complex flow situations in PATs, especially those involving significant vortex structures and mixing regions. Additionally, the SST k-ω model effectively handles separated flows, a critical factor in PAT operations. To further improve the accuracy of capturing rotational and curvature effects, the SST-CC model adds curvature correction to the SST k-ω model, making it particularly suitable for analyzing flow behaviors within blade passages, which directly impacts the efficiency and performance of PATs.

The S–A model is very popular in aerospace applications due to its relatively simple structure and reduced dependency on mesh quality. However, in the context of PAT applications, while it can simplify calculations to some extent, it may not provide the high accuracy required. The Wilcox k-ω model, which improves prediction accuracy by adjusting constants and formulas, might be a more suitable choice for studying detailed flow phenomena, such as complex flow interactions occurring under specific conditions.

Therefore, in the design and analysis of PATs, selecting the most suitable turbulence model depends on specific research needs, flow characteristics, and available resources. Considering the operating conditions and geometric complexity of PATs, the SST k-ω model and its improved version, the SST-CC model, seem to be the preferred choices. These models can provide more accurate results under complex flow conditions, aiding in the optimization of PAT performance and ensuring efficient operation across various working points.

Although current mesh generation techniques have made significant progress in CFD simulations, there is still room for improvement. Particularly, the impact of different mesh densities on computational results requires further investigation to determine the optimal meshing strategy. With advancements in computer technology and algorithms, mesh generation methods have become diversified, and multiple software tools for mesh creation are now available on the market. Among these methods, tetrahedral, hexahedral, and polyhedral meshes are the three primary types, each possessing unique characteristics and applicable scenarios [108].

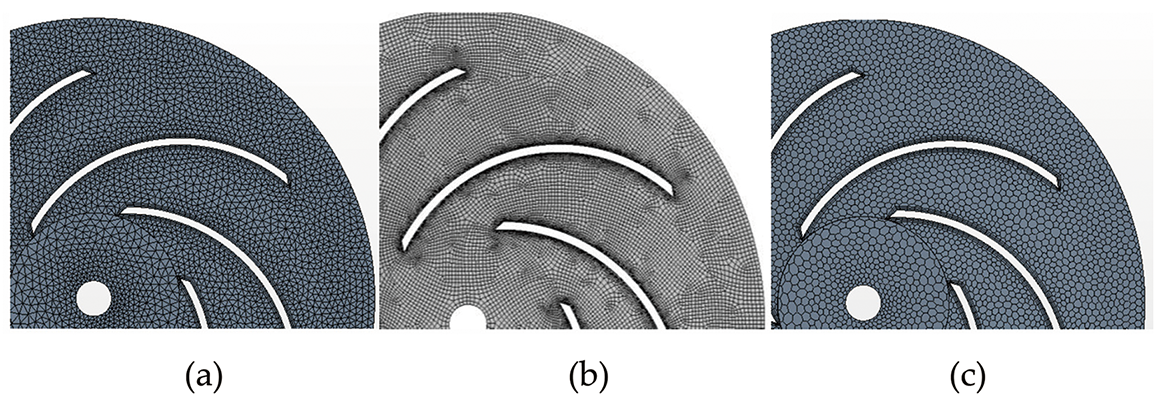

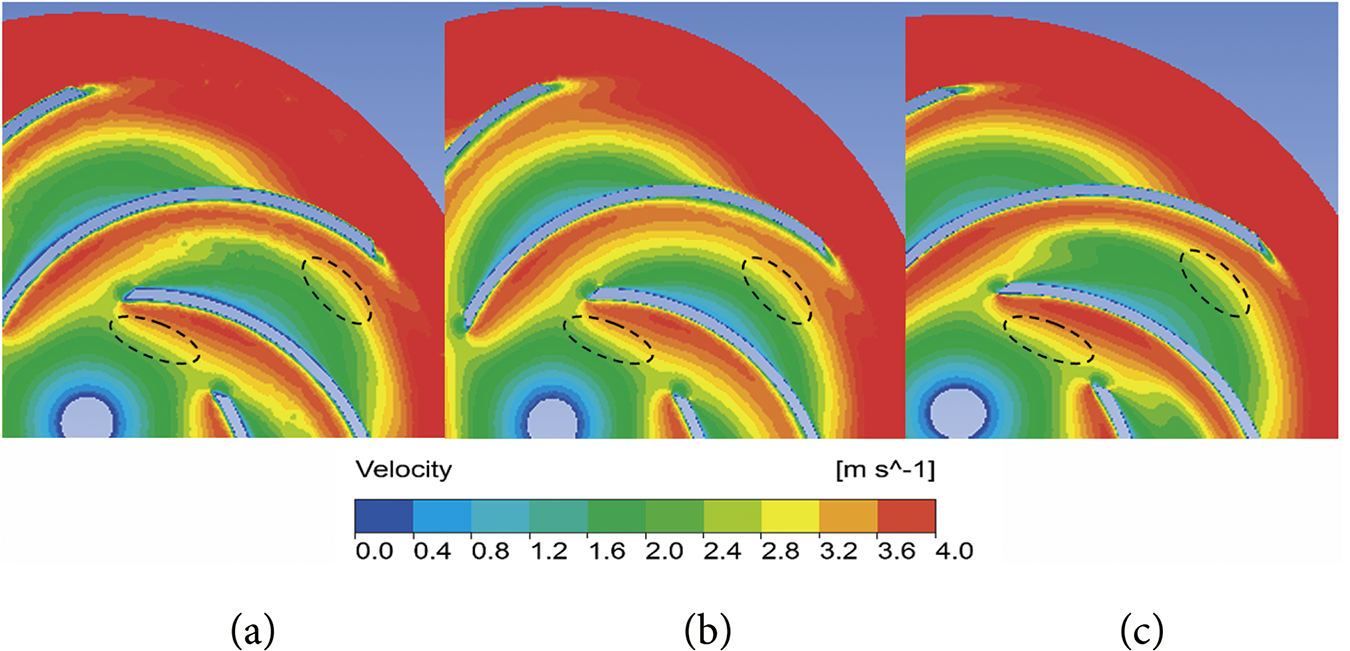

Zheng et al.’s research compared Tetrahedron, Hexahedron, and Polyhedron meshing schemes. Fig. 4 shows images of different mesh types, while Fig. 5 presents a comparison of the corresponding velocity contours [109]. Their study demonstrated that polyhedral meshes offer advantages in simulating complex flows, capable of more accurately capturing the internal flow field characteristics of recirculation pumps. This not only improves model accuracy but also enhances computational efficiency and adaptability.

Figure 4: Grid diagram: (a) tetrahedron; (b) hexahedron; (c) polyhedron Adapted with permission from Ref. [109], Copyright ©2018, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science publishing

Figure 5: Comparison of velocity contour: (a) tetrahedron; (b) hexahedron; (c) polyhedron Adapted with permission from Ref. [109], Copyright ©2018, IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science publishing

Furthermore, Tang et al.’s research further confirms the effectiveness of polyhedral meshes [110], especially when dealing with irregular geometries. Therefore, for devices such as pumps that contain complex internal flow paths and rotating components, adopting a flexible and adaptable mesh generation strategy is particularly important.

Although polyhedral meshes have advantages in handling irregular geometries, a single type of mesh model often cannot meet all requirements. Therefore, a hybrid mesh approach has become an effective solution. This method combines the advantages of hexahedral, tetrahedral, and polyhedral meshes, enhancing mesh generation efficiency and computational speed while ensuring calculation accuracy.

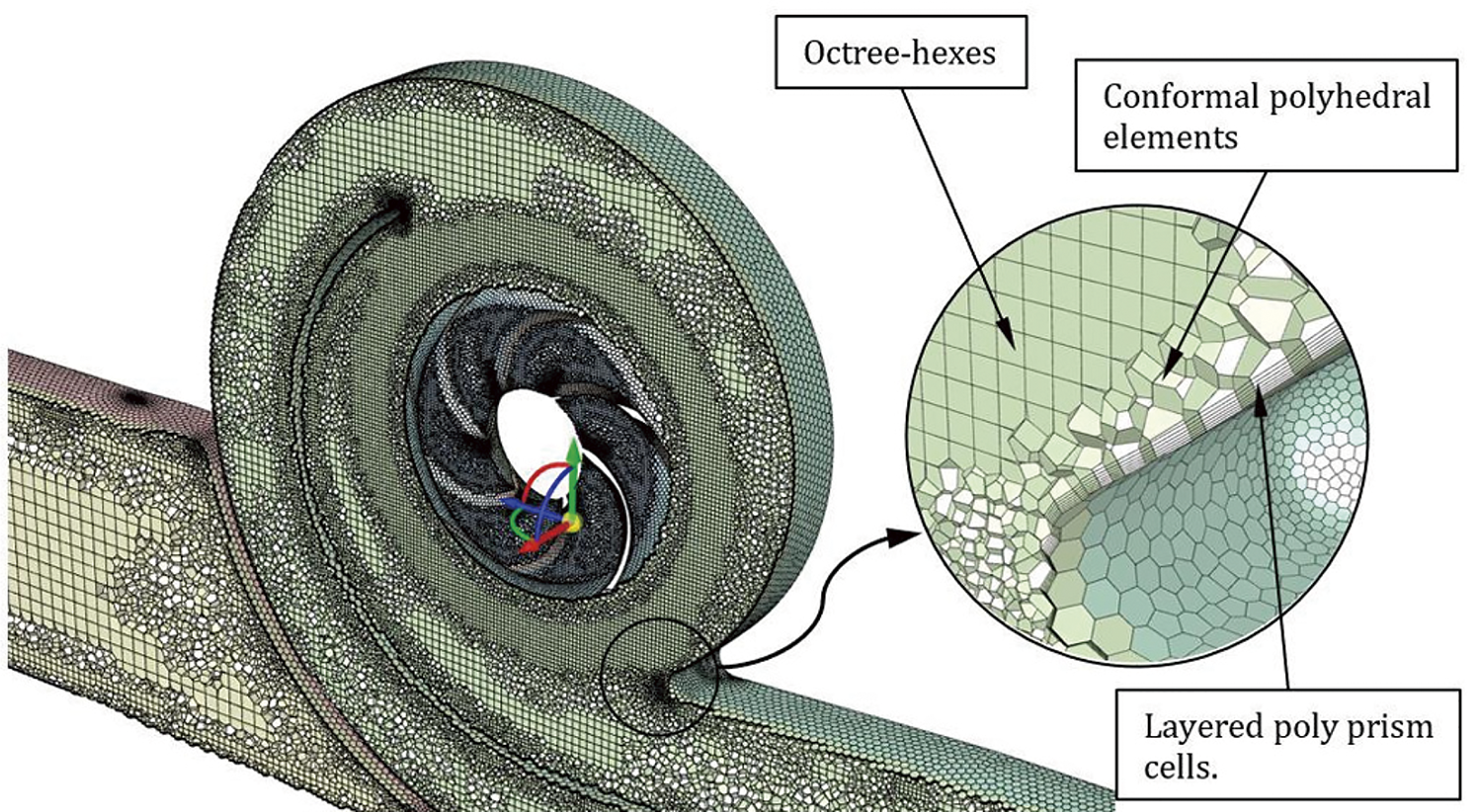

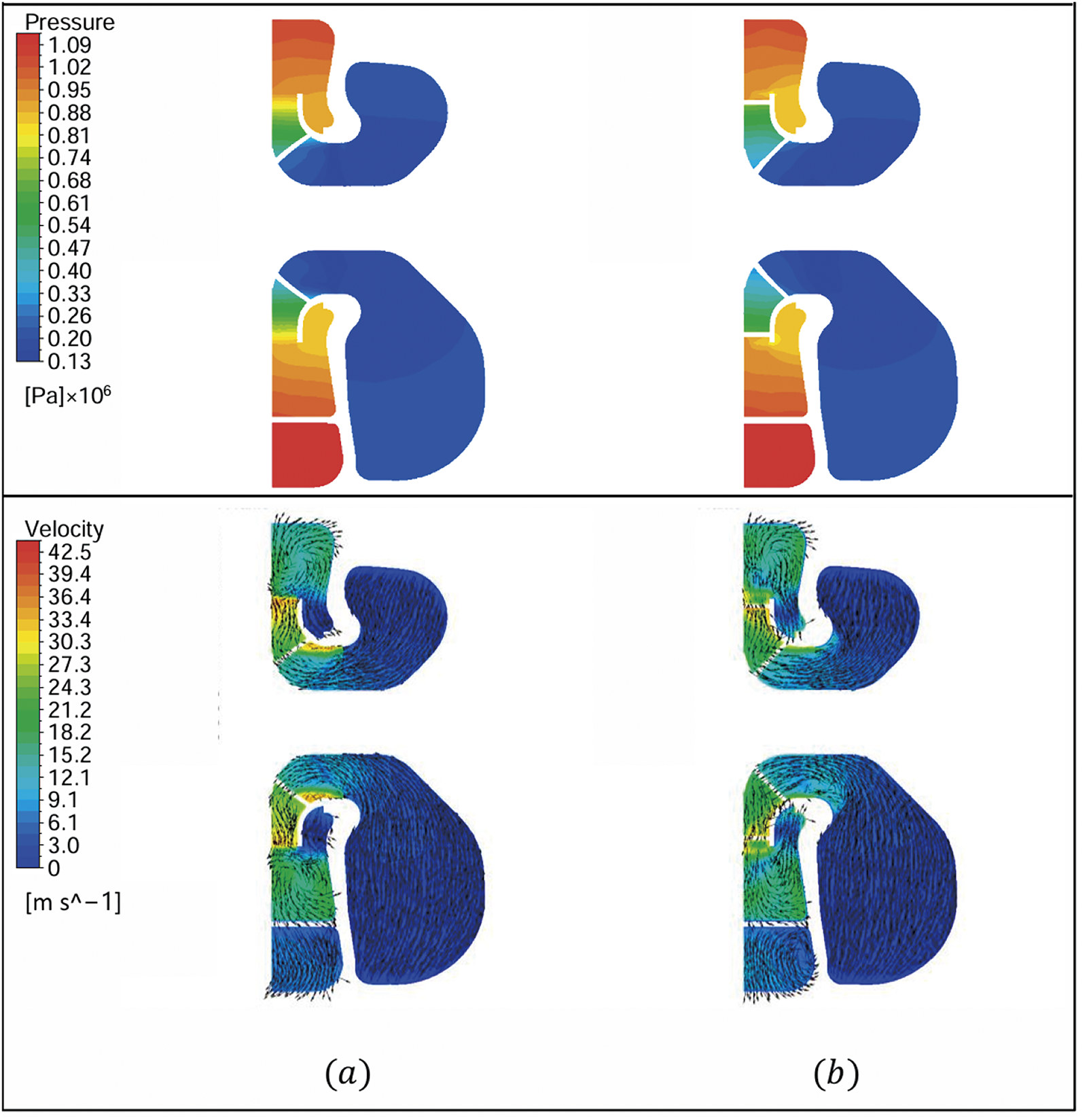

Arocena and Danao compared the use of a Poly-Hexcore hybrid mesh (with Polyhedron used for boundary layers and Hexahedron for the interior, as shown in Fig. 6) to structured hexahedral meshes. The Poly-Hexcore hybrid mesh reduced the number of cells by approximately 37%. Under design conditions, both mesh models predicted pump head, efficiency, and shaft power within 1% of each other, and their internal flow characteristics were consistent, as shown in Fig. 7. However, the Poly-Hexcore hybrid mesh model reduced computation time by about 25%. Compared to data provided by the manufacturer, additional simulations using the Poly-Hexcore hybrid mesh demonstrated that this model could accurately predict performance [111]. This indicates that the Poly-Hexcore hybrid mesh achieves high accuracy while reducing the number of mesh elements.

Figure 6: Poly-Hexcore hybrid mesh Adapted with permission from Ref. [111], Copyright ©2023, Processes publishing

Figure 7: Pressure and velocity contour plots at rated flow: (a) poly-hexcore mesh; (b) multi-block structured hexagonal mesh Adapted with permission from Ref. [111], Copyright ©2023, Processes publishing

For pumps, the fluid domain structure is not a regular geometry, so dividing it into a high-quality mesh model requires a more flexible and adaptable mesh generation strategy; using just one type of mesh model is insufficient. Therefore, for devices like pumps that have complex internal flow paths and rotating components, a hybrid mesh approach is often an effective method. This approach combines the advantages of hexahedral, tetrahedral, and polyhedral meshes, enhancing both mesh generation efficiency and computational speed while ensuring calculation accuracy.

3.3 Internal Characteristics Prediction

Experimental testing is one of the most direct and effective ways to verify theoretical calculations and numerical simulation results. By constructing physical prototypes and testing them under laboratory conditions, real performance data can be obtained. Experimental values not only serve to calibrate the accuracy of theoretical models and numerical simulations but also help identify potential problem areas. Additionally, experimental testing is an indispensable part when selecting suitable PAT units, helping ensure that the final results meet expected standards for reliability and efficiency. Despite the high costs and time consumption associated with experiments, they are key steps in ensuring design success.

A PAT test bench typically requires flow meters, pressure sensors, tachometers, torque measurement devices, data acquisition systems, and necessary safety protection equipment. Moreover, appropriate piping connections and valve control systems are needed to adjust fluid flow and ensure a stable and adjustable fluid source. The entire setup should simulate actual operating conditions to accurately evaluate the performance and efficiency of pumps used as turbines.

To accurately select suitable pumps for use as turbines, it is essential to establish effective performance prediction methods. Current research trends focus on developing universal and robust prediction models aimed at replacing traditionally expensive, inaccurate, and time-consuming experimental methods [112]. These new predictive models must be capable of handling a wide range of pump types while maintaining high accuracy and reliability under different operating conditions, thus helping engineers make informed decisions during the design phase and reducing trial-and-error costs.

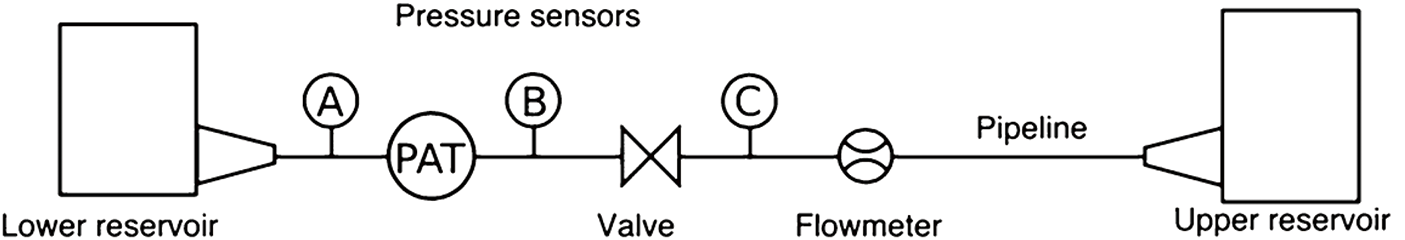

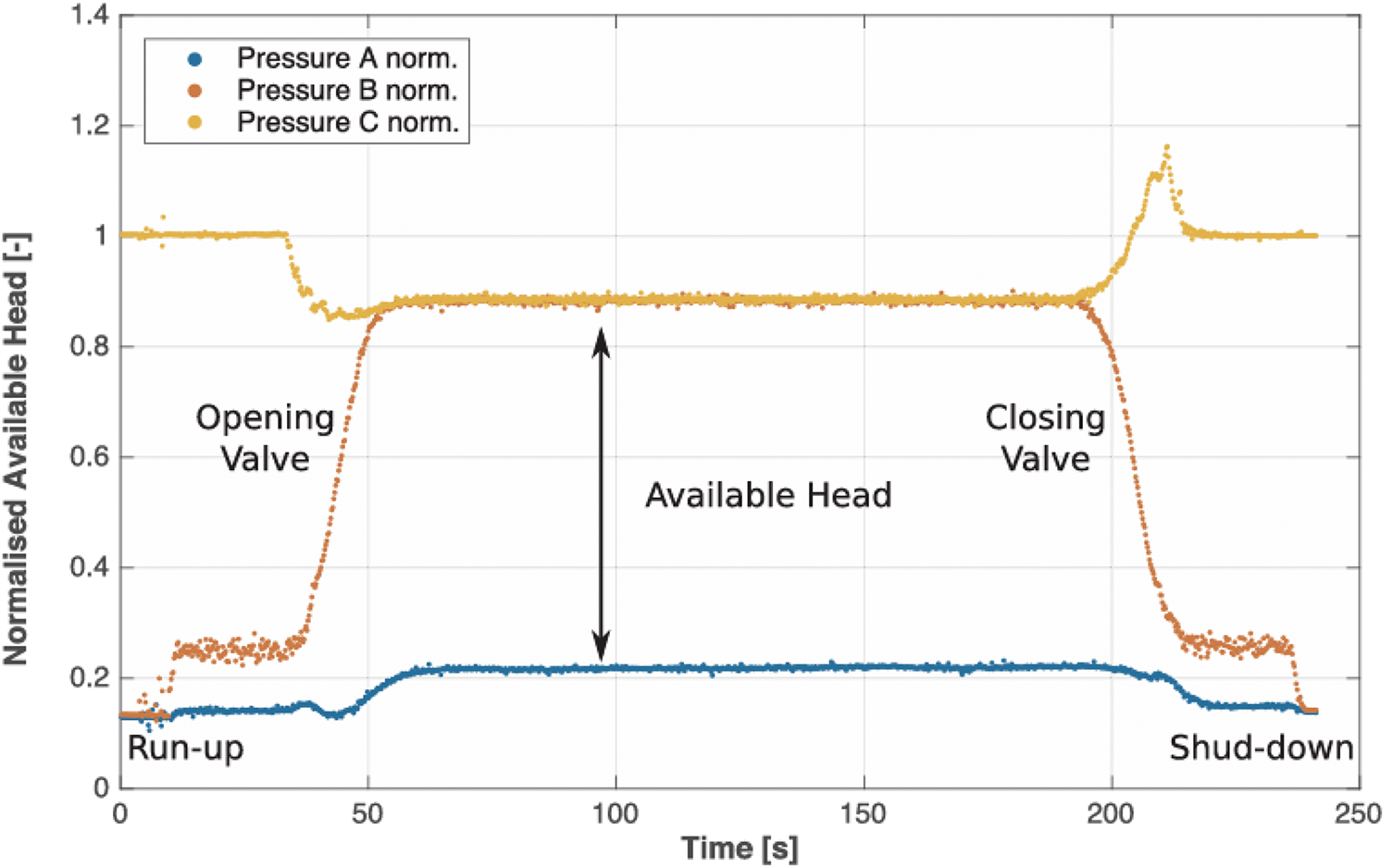

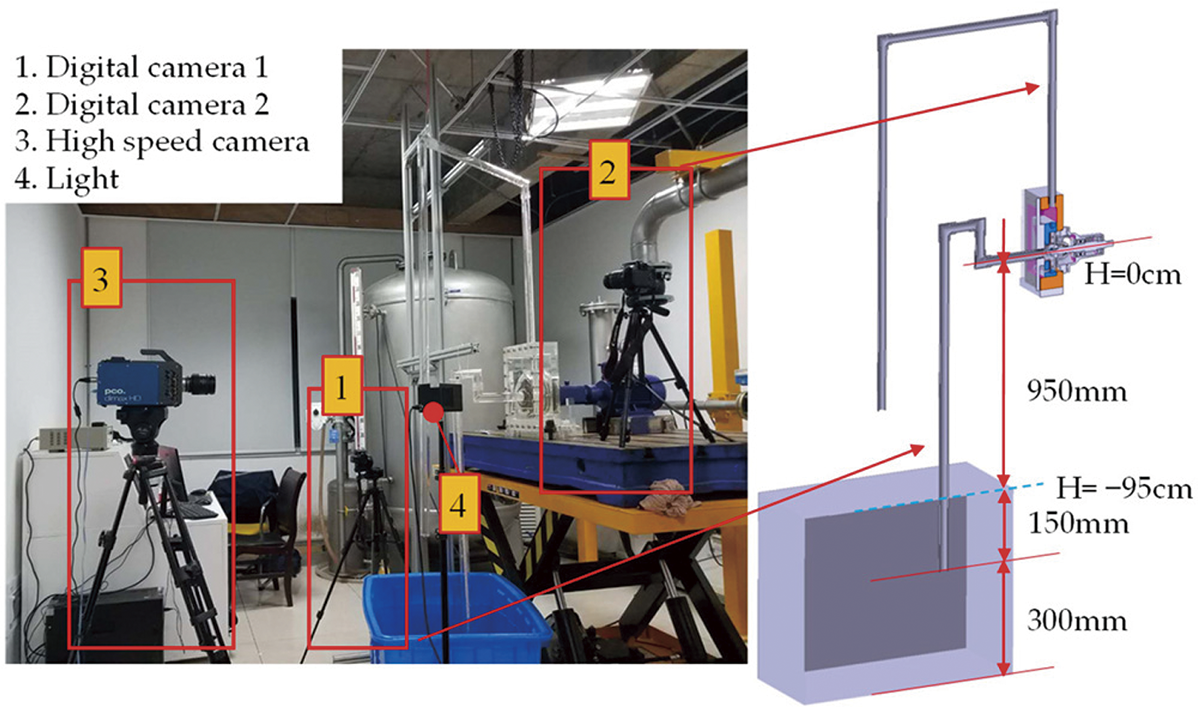

Researchers such as Alessandro Morabito have proposed an innovative experimental installation method for PATs [113], illustrated in Fig. 8, with detailed experimental setups shown in Fig. 9, ensuring precise pressure measurements throughout the system as depicted in Fig. 10. This method allows the research team to conduct in-depth analysis of experimental characteristics, providing a solid data foundation for subsequent theoretical modeling and practical applications. The work of Alessandro Morabito et al. demonstrates that optimizing experimental setups can yield higher quality data, thereby enhancing understanding of the operational characteristics of pumps used as turbines.

Figure 8: Model installation scheme Adapted with permission from Ref. [113], Copyright ©2019, Applied Energy publishing

Figure 9: Experimental setup Adapted with permission from Ref. [113], Copyright ©2019, Applied Energy publishing

Figure 10: Pressure measurements for sensor A, B and C facing PaT run-up, opening valve, normal operation, closing valve and shut-down Adapted with permission from Ref. [113], Copyright ©2019, Applied Energy publishing

3.3.1 Internal Flow Characteristics Testing

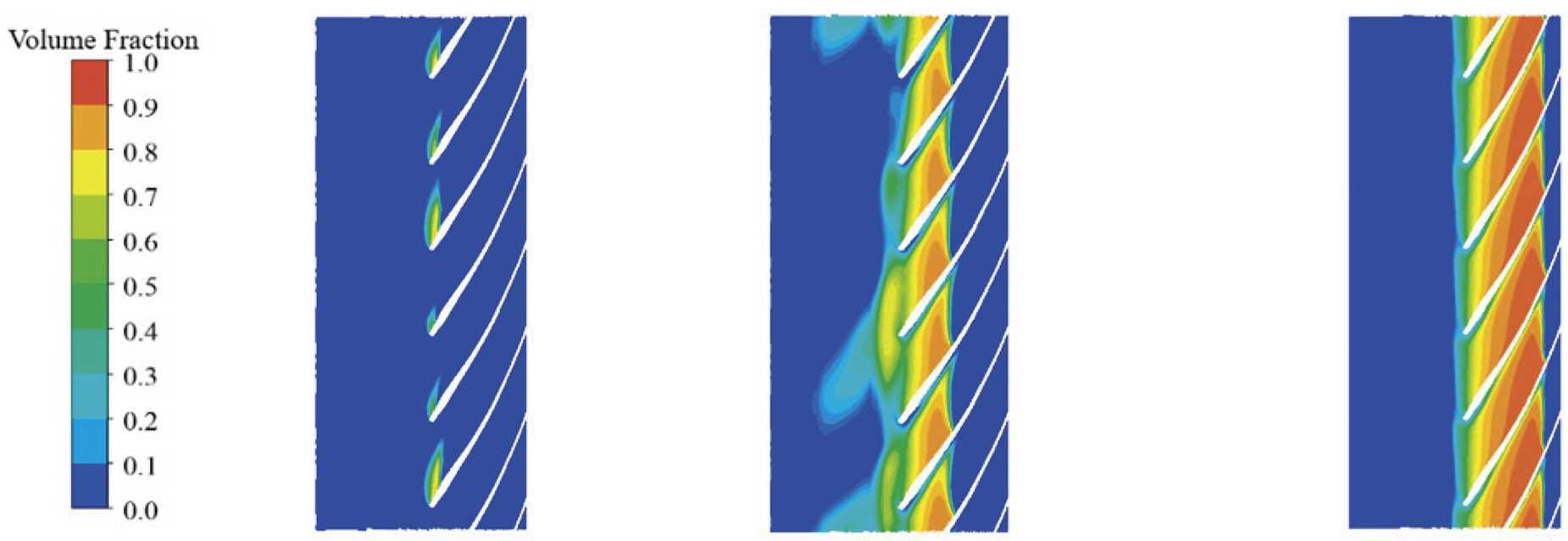

Scholars Qian et al. successfully observed the dynamic changes of gas-liquid two-phase flow during pump operation using a transparent experimental pump and high-speed photography technology [114,115]. This direct method provides a new perspective for understanding complex internal fluid dynamics mechanisms, allowing researchers to visually observe phenomena that were previously difficult to capture, such as bubble formation, development, and collapse. Their transparent test rig is shown in Fig. 11.

Figure 11: Transparent experimental bench Adapted with permission from Ref. [114], Copyright ©2022, Energies publishing

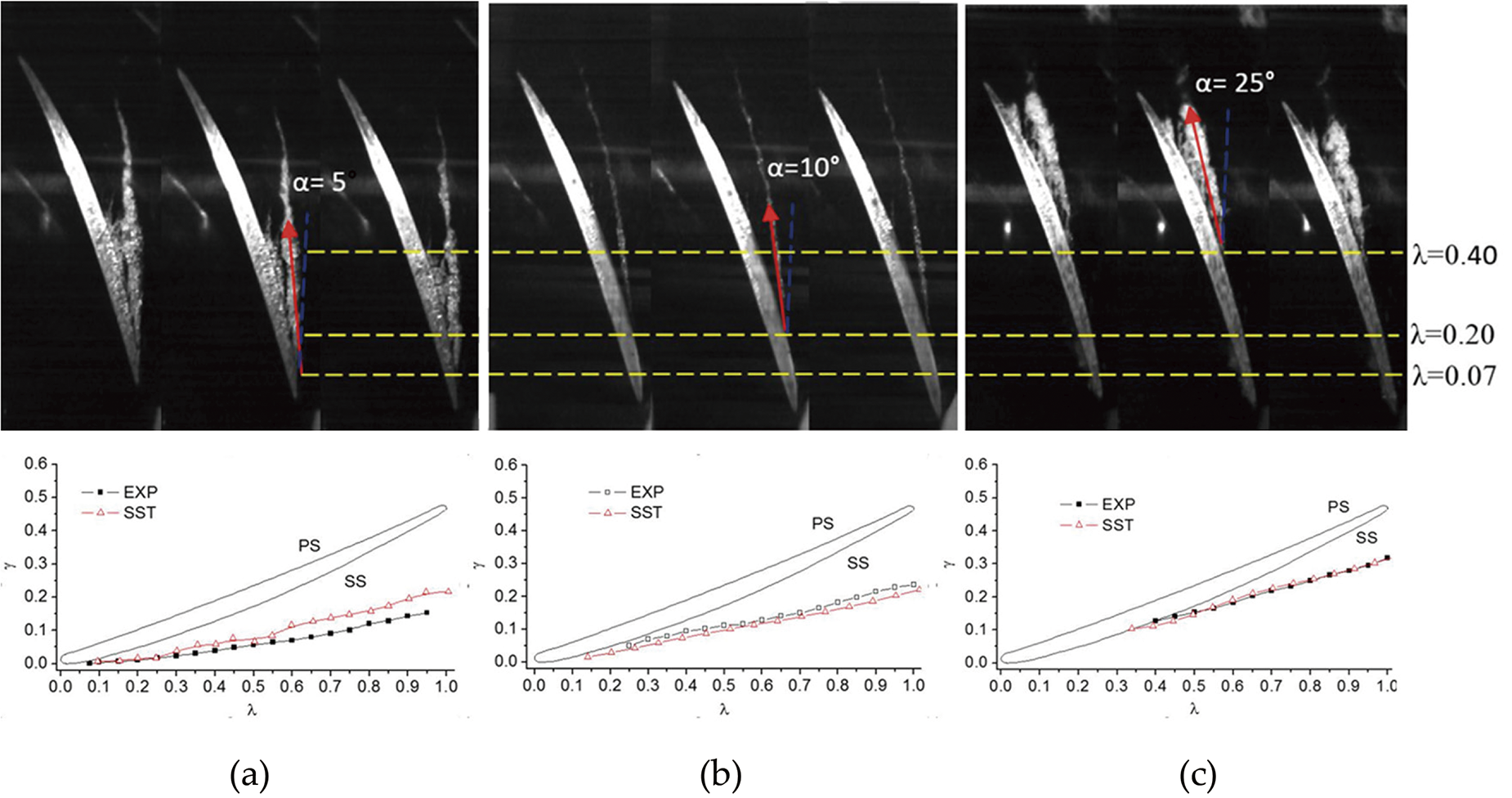

Moreover, when evaluating the numerical simulation results of pump operations, accuracy and reliability are two key considerations. Some studies have shown that high-speed photography experiments conducted with axial pumps featuring transparent casings are significant for tracking bubble trajectories based on cavitation phenomena [116]. As shown in Fig. 12, these experiments reveal that when using the SST k–ω turbulence model for numerical calculations, the predicted bubble trajectories closely match the actual visualized results captured by high-speed cameras. This finding underscores the importance of correctly selecting turbulence models and also demonstrates the effectiveness of combining experimental and numerical simulation methods. Such an approach can significantly improve prediction accuracy, providing strong support for engineering practices.

Figure 12: Comparison of predicted and experimental TLV trajectories at different flow rate conditions: (a) Q/QBEP = 0.85; (b) Q/QBEP = 1.0; (c) Q/QBEP = 1.2 Adapted with permission from Ref. [116], Copyright ©2015, Computers & Fluids publishing

Therefore, establishing a suitable experimental bench model can greatly facilitate the prediction of PAT internal flow characteristics, providing scientific basis for optimization design and efficiency improvement.

3.3.2 Internal Flow Numerical Prediction

Compared to relying on a physical experimental bench to test PAT’s internal flow characteristics, using CFD technology provides a more convenient and cost-effective solution. CFD technology can thoroughly analyze internal flow characteristics such as pressure pulsations, cavitation effects, velocity field distribution, turbulent kinetic energy, and vortex distribution without the need for a physical prototype. This is particularly useful for the design optimization and fault diagnosis of PATs.

(1) Velocity field distribution

As shown in Fig. 13, Wei Wang’s research illustrates the velocity vectors and streamlines in the guide vane-impeller region [117], which helps to understand the specific movement paths and velocity variation patterns of the fluid inside the PAT. This is significant for identifying potential flow non-uniformities and improving geometric design.

Figure 13: The internal flow characteristics of guide vanes and runners in one period Adapted with permission from Ref. [117], Copyright ©2021, Journal of Marine Science and Engineering publishing

(2) Pressure field

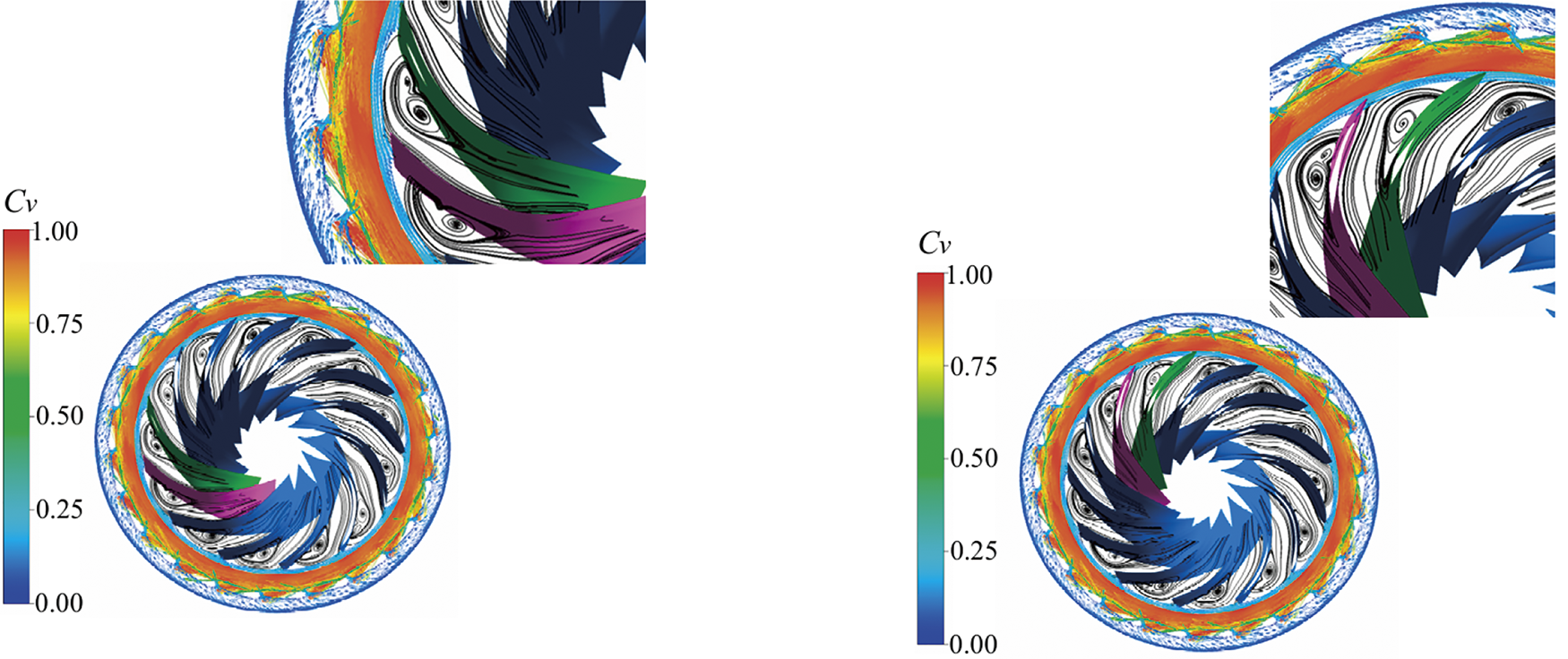

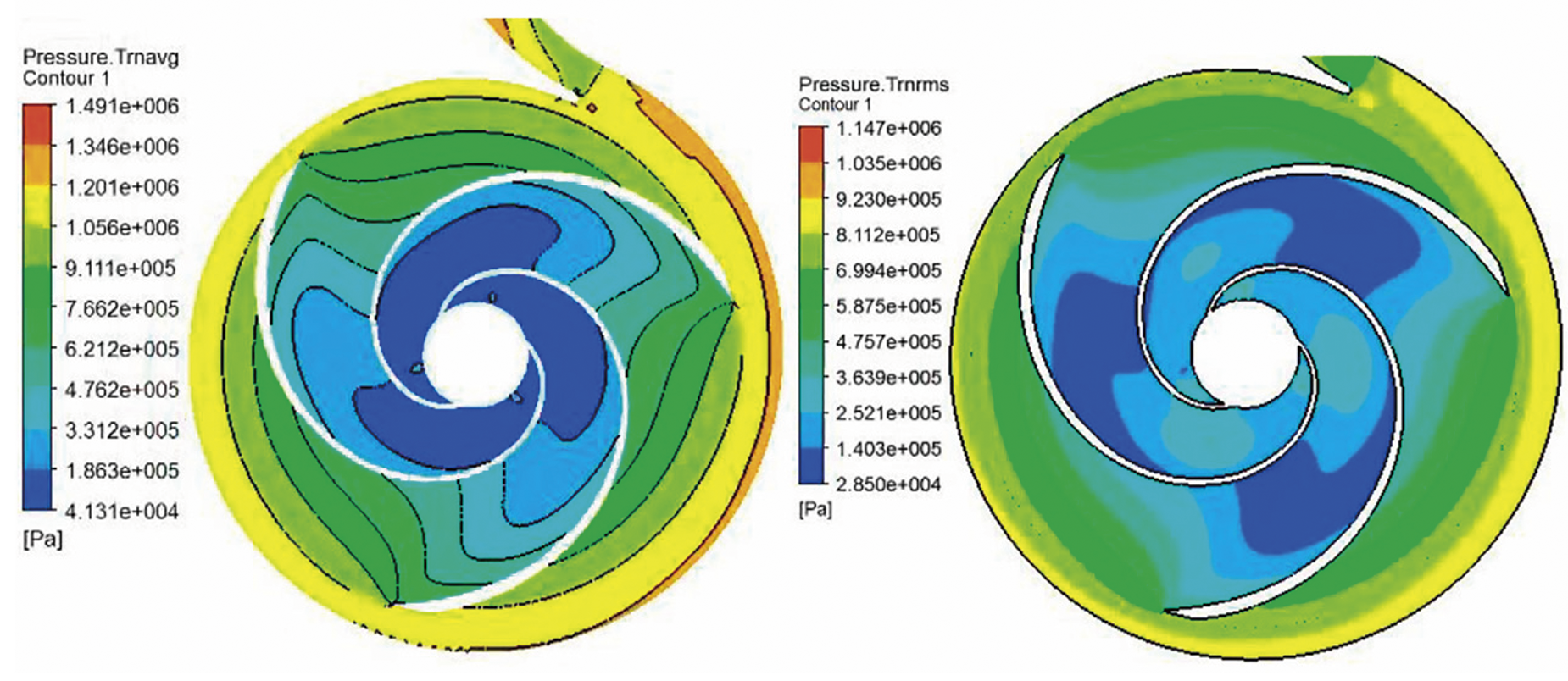

As shown in Fig. 14, the work of Wei et al. reveals the pressure distribution and pressure variation intensity inside the impeller [93], while, as shown in Fig. 15, Xiang et al. delve into the time-domain and frequency-domain pressure pulsations within the volute under different flow conditions [118]. These studies are crucial for assessing the stability, noise levels, and potential vibration issues of PATs.

Figure 14: Distribution of mean pressure and pressure fluctuation intensity in the impeller Adapted with permission from Ref. [93], Copyright ©2023, Frontiers in Energy Research publishing

Figure 15: Time histories and spectra of pressure in volute at three flow rates Adapted with permission from Ref. [118], Copyright ©2022, Physics of Fluids publishing

(3) Cavitation effects

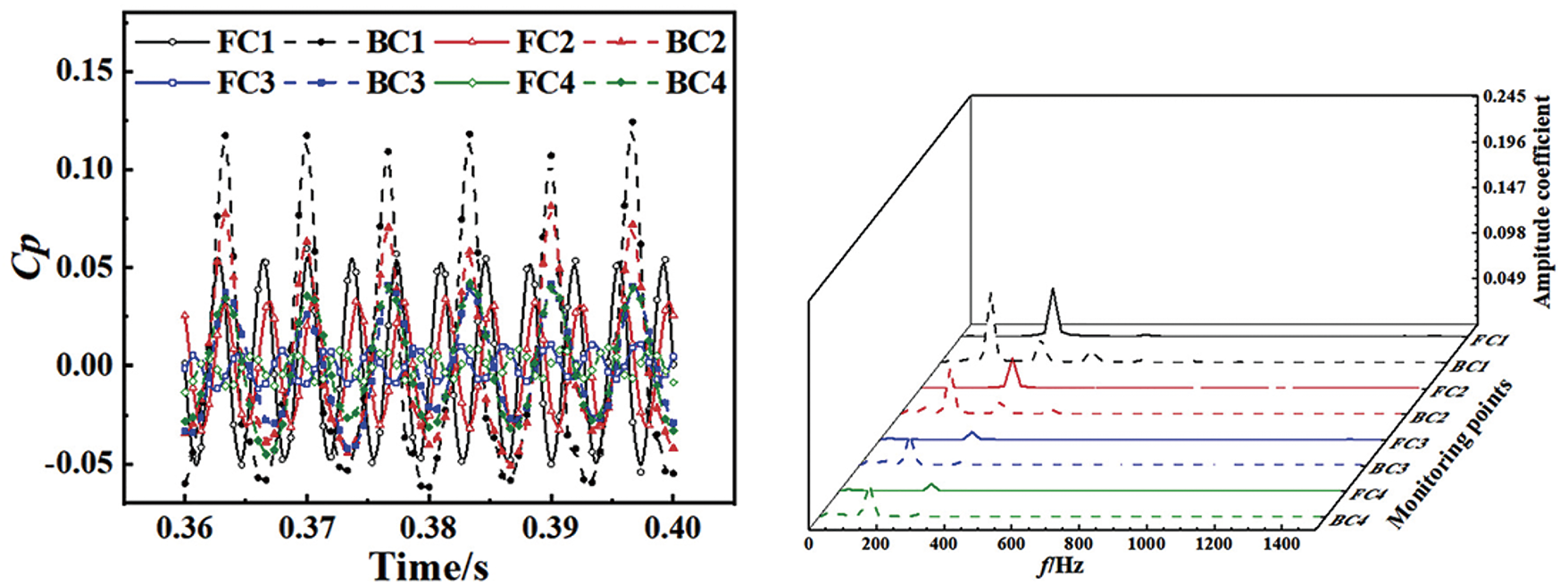

As shown in Fig. 16, Jia et al. conducted research on the air volume fraction [119], which refers to the variation in bubble volume. This is crucial for understanding the mechanisms behind the occurrence and development of cavitation, as cavitation not only affects the efficiency of PATs but can also lead to equipment damage.

Figure 16: Bubble volume Adapted with permission from Ref. [119], Copyright ©2023, Physics of Fluids publishing

(4) Turbulent kinetic energy

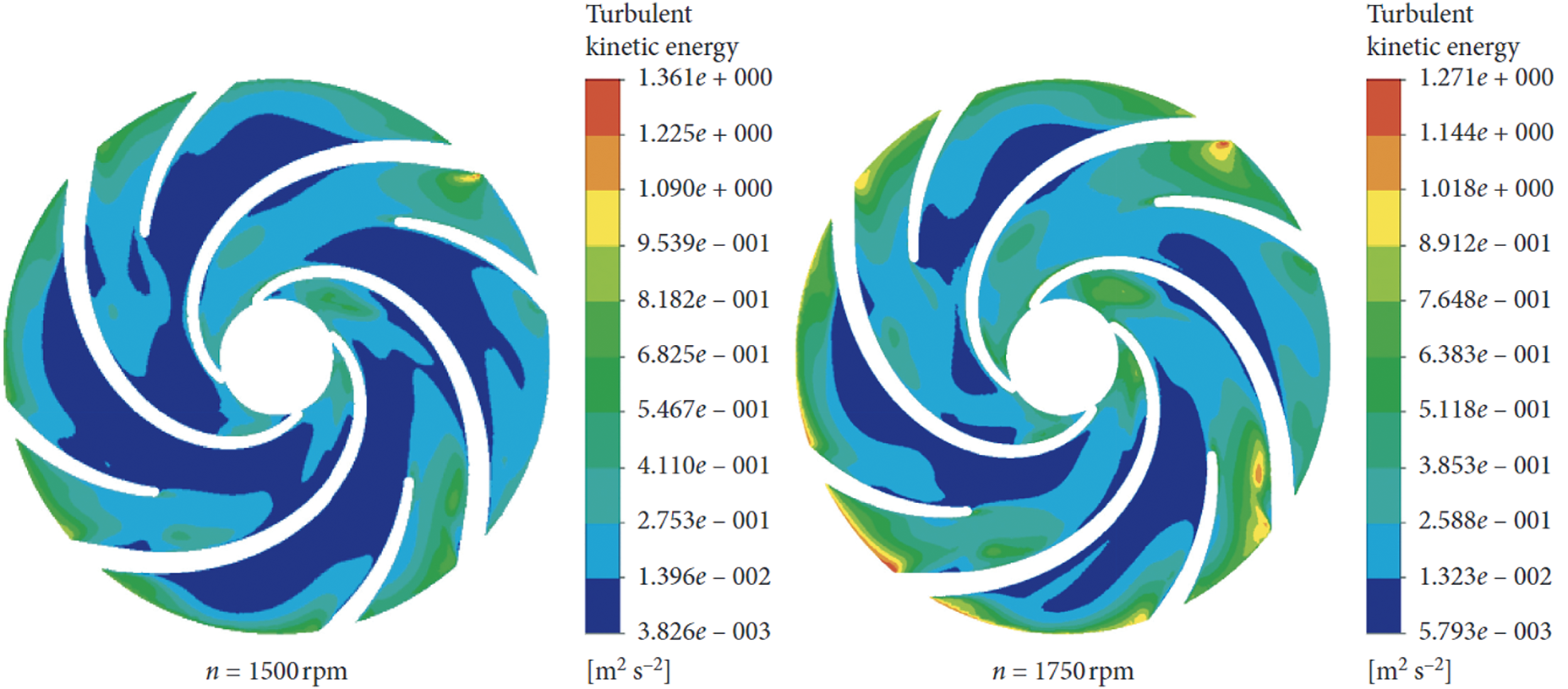

As shown in Fig. 17, Du et al. explored the propagation characteristics of turbulent kinetic energy within PATs at different speeds, particularly at the best efficiency point [96]. This research is significant for understanding energy loss mechanisms and is also important for optimizing the selection of turbulence models.

Figure 17: Turbulence dissemination for the Pump as Turbine diverse speed at BEP Adapted with permission from Ref. [96], Copyright ©2020, Complexity publishing

(5) Vortex distribution

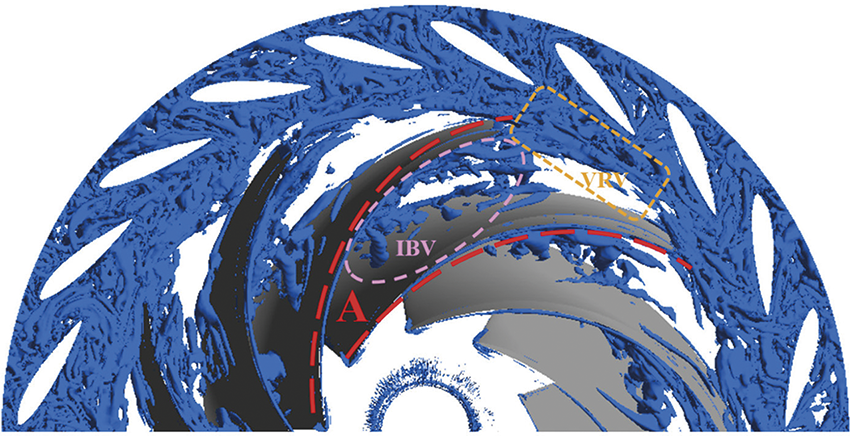

As shown in Fig. 18, Hao et al. analyzed the vortex distribution at the impeller [120]. The presence of vortices directly affects the efficiency of fluid transmission and is one of the primary causes of energy loss. Therefore, gaining a deep understanding of the formation and evolution of vortices is crucial for improving the flow characteristics and overall performance of PATs.

Figure 18: Vortex distribution in runner and vaneless region Adapted with permission from Ref. [120], Copyright ©2024, Journal of Energy Storage publishing

Therefore, compared to physical experimental models, utilizing CFD technology allows for a more convenient and comprehensive prediction and analysis of the internal flow characteristics of PAT.

3.4 External Characteristics Prediction

When a pump is used as a turbine, predicting its external characteristics becomes a key step in evaluating its performance. This process is typically carried out in a controlled laboratory environment to ensure consistency and repeatability of testing conditions. To accurately collect data, researchers use specially designed test platforms and high-precision sensors to monitor and record various parameters of the equipment.

(1) Steady-state testing

Steady-state testing forms the basis for establishing performance curves of PAT. By testing PAT under a series of preset different operating conditions, key parameters such as flow rate, pressure drop, and output power can be systematically recorded during stable operation. This data not only helps in understanding PAT’s performance under various working conditions but also serves to draw detailed performance curve charts, providing critical reference information for engineers to optimize design and operational efficiency. Moreover, by comparing theoretical models with actual measurement results, mathematical models can be further validated and adjusted to improve prediction accuracy.

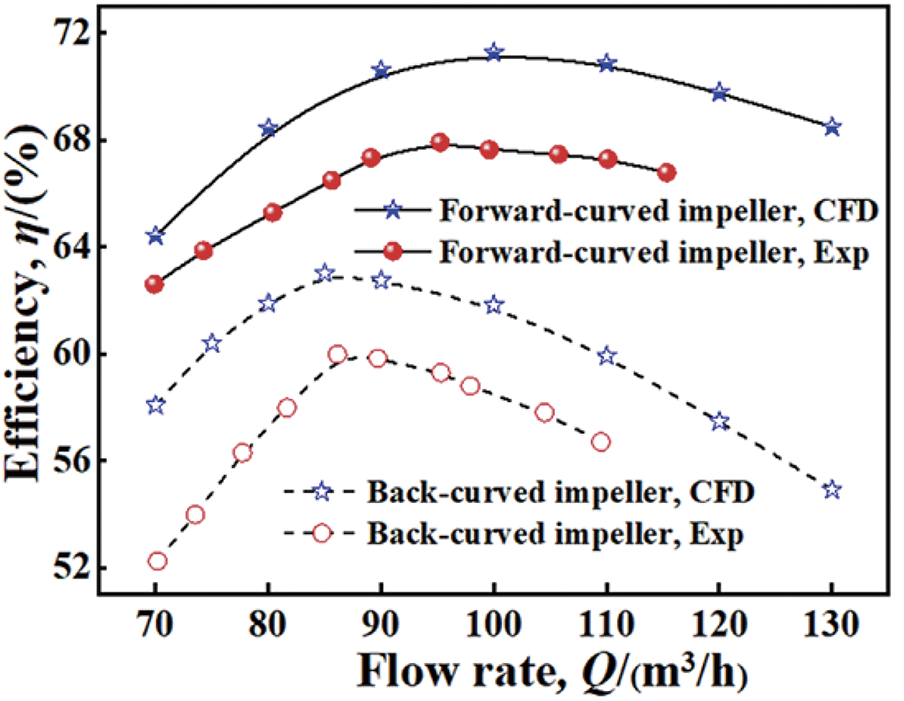

As shown in Fig. 19, Xiang et al. conducted external characteristic tests on PAT using both experimental and CFD methods, and compared the results from both approaches [118]. The study found that the error between CFD and experimental tests was within 5%. This demonstrates that numerical simulation can effectively replace some physical experiments, especially during the preliminary design phase or when conducting actual tests is challenging.

Figure 19: Efficiency curves of two PATs by testing and numerical calculation Adapted with permission from Ref. [118], Copyright ©2022, Physics of Fluids publishing

Fig. 20 shows other external characteristic numerical calculations performed by Xiang et al. using CFD technology [118], including the flow-head (Q-H) curve, flow-speed (Q-n) curve, and flow-power (Q-P) curve. These curves not only visually present the performance characteristics of PAT under different operating conditions but also provide a solid data foundation for subsequent analysis and optimization.

Figure 20: Comparison of external characteristic curves of two PATs: (a) Q-H curves; (b) Q-n curves; (c) Q-P curves Adapted with permission from Ref. [118], Copyright ©2022, Physics of Fluids publishing

(2) Transient testing

In addition to steady-state testing, transient testing is equally crucial for evaluating the response capability of PAT under dynamically changing conditions. This type of testing simulates various real-world operational scenarios such as startup, shutdown, and sudden load increases or decreases, aiming to capture how PAT reacts under non-steady conditions. Transient testing particularly focuses on assessing the equipment’s performance in the face of rapidly changing work environments, including startup times and speeds, the time required to switch from one load level to another, and other related parameters. Through detailed analysis of these aspects, manufacturers can identify potential problem areas and implement corresponding improvements to ensure that PAT operates efficiently and stably under various operating conditions.

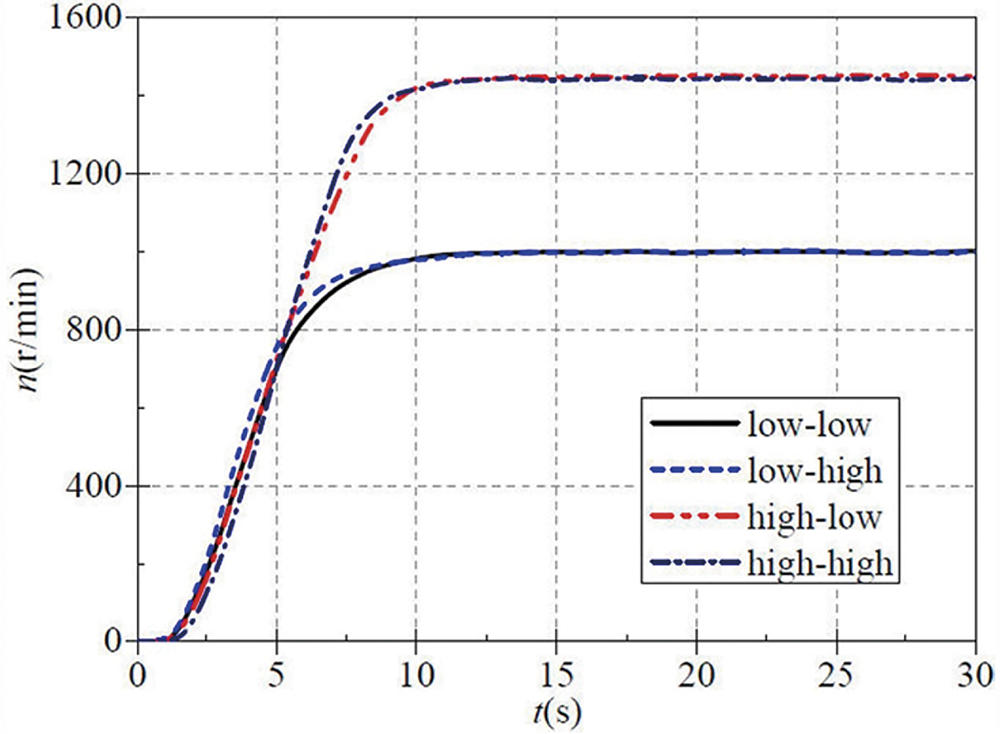

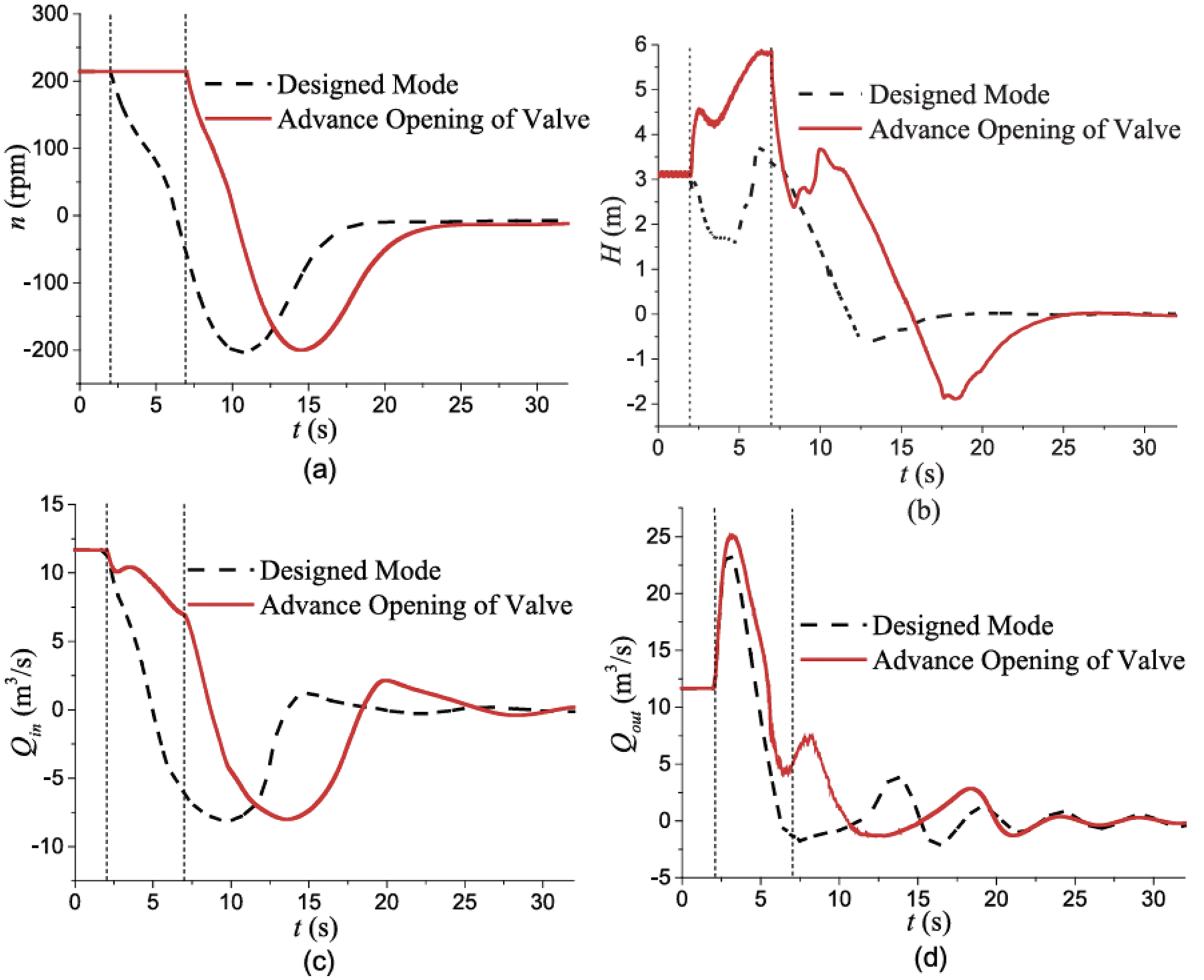

Zhang et al. conducted a study on the transient characteristics prediction of PAT startup using experimental testing methods [121]. As shown in Fig. 21, they recorded the immediate rotational speed changes of PAT during the startup process, providing direct evidence for understanding behavior at the startup stage. Fig. 22 illustrates the changes in immediate flow rate during PAT startup. Such meticulous analysis helps reveal complex flow phenomena during startup, offering guidance for improving startup performance.

Figure 21: Instantaneous rotational speed of pump as turbine Adapted with permission from Ref. [121], Copyright ©2022, Energy Science & Engineering publishing

Figure 22: Instantaneous flow rate of pump as turbine: (a) overall; (b) local Adapted with permission from Ref. [121], Copyright ©2022, Energy Science & Engineering publishing

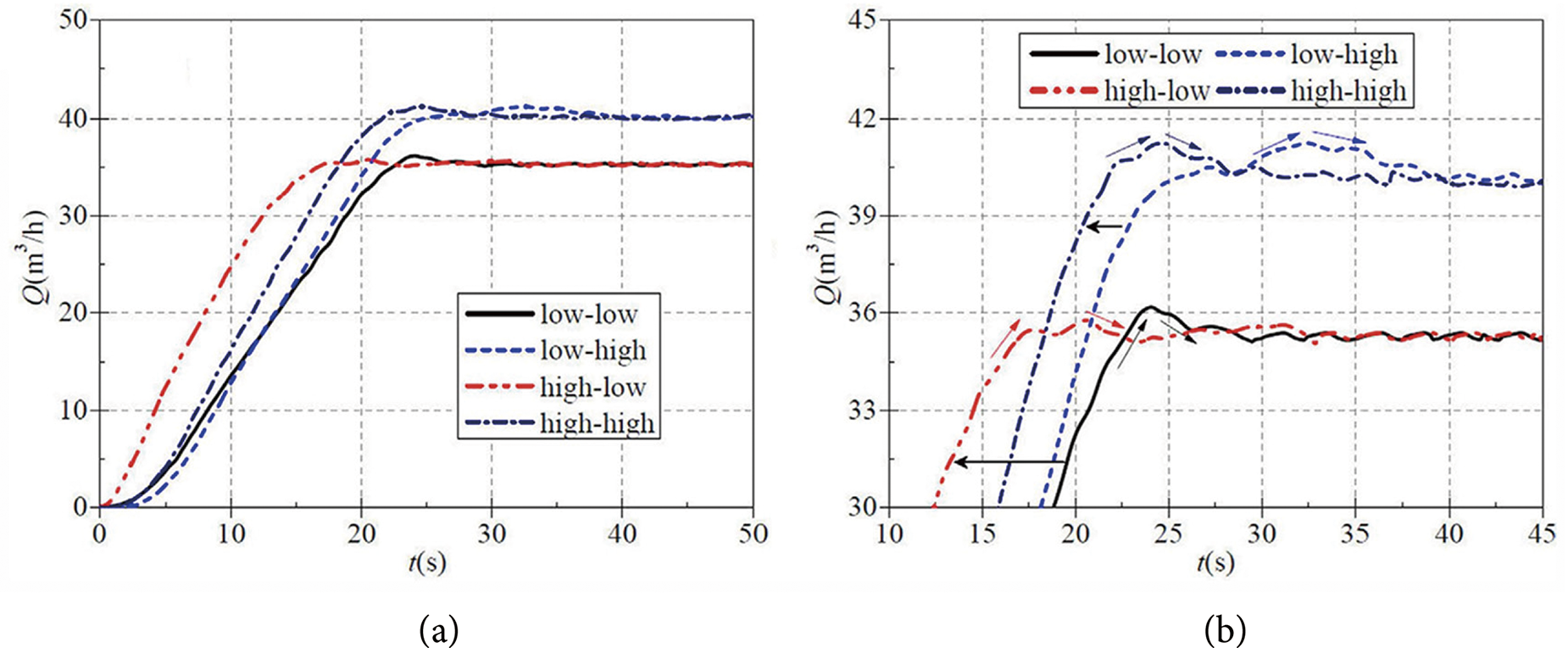

Liu et al. conducted a study on the shutdown process of axial-flow pumps. They used numerical calculations to simulate and analyze this process. Fig. 23 summarizes the variation of different parameters over time under two modes, specifically including the relationship between rotational speed (n) and time (t), head (H) and time (t), inlet flow rate (Qin) and time (t), as well as outlet flow rate (Qout) and time (t). These charts reveal the dynamic evolution of internal flow conditions in axial-flow pumps during shutdown, providing important theoretical foundations for understanding and improving performance during this process. Their numerical calculation results also highlight significant differences in shutdown characteristics under various operating conditions, which is crucial for ensuring the safe and reliable operation of pumps [122].

Figure 23: Variation laws of parameters of two modes: (a) n–t; (b) H–t; (c) Qin–t; (d) Qout–t Adapted with permission from Ref. [122], Copyright ©2017, Advances in Mechanical Engineering publishing

Through the analysis of related studies on PAT performance prediction, the following conclusions can be drawn:

(1) Importance of integrated approaches

The prediction of PAT performance requires the integrated application of three primary methodologies: theoretical calculations, numerical simulations, and experimental testing. Each approach possesses distinct advantages and limitations, and only through their combined utilization can more accurate results be obtained. While theoretical calculations enable rapid preliminary assessments, their precision is often constrained by simplified model assumptions. CFD technology effectively addresses complex flow phenomena and provides detailed data such as internal flow fields, yet it necessitates careful selection of turbulence models and meshing strategies, and discrepancies between computational results and actual conditions may still persist. Despite being costly and time-consuming, experimental testing plays an indispensable role in directly validating the accuracy of the aforementioned two approaches.

(2) Integration of traditional and modern technologies

Traditional conversion factor methods based on the best efficiency point and specific speed, despite certain limitations, lay the groundwork for applying modern technologies such as machine learning. Machine learning can automatically identify patterns from large amounts of historical data, capture complex nonlinear system behaviors, and consider multiple influencing factors, thereby enhancing prediction accuracy and reliability. Methods like evolutionary polynomial regression and artificial neural networks demonstrate potential in PAT performance prediction, while also highlighting the importance of complementary cooperation between different approaches.

(3) Significance of CFD technology

With advancements in computer technology and algorithms, CFD technology has made significant progress in handling complex geometries and boundary conditions (including method optimization and computational efficiency), becoming an indispensable tool for PAT performance prediction. Selecting suitable turbulence models is critical for ensuring the accuracy of simulation results, while hybrid mesh methods improve computational efficiency and adaptability. These developments not only deepen the understanding of PAT’s internal flow characteristics but also provide strong support for optimization design.

(4) Irreplaceability of experimental testing

Despite the valuable insights provided by numerical simulations and theoretical analyses, experimental testing remains a key step for verifying the accuracy of predictive models, identifying potential problem areas, and ensuring that final results meet expected standards of reliability and efficiency. Innovative methods such as transparent test benches and high-speed photography further enhance the capabilities of experimental testing, allowing researchers to visually observe phenomena that were previously difficult to capture, such as bubble formation and development processes.

(5) Comprehensive prediction of internal and external characteristics

To comprehensively assess PAT’s performance, both internal flow characteristics (such as pressure pulsations, cavitation effects, velocity field distribution, turbulent kinetic energy, and vortex distribution) and external characteristics (including steady-state and transient conditions, startup or shutdown scenarios, flow-head curves, flow-speed curves, flow-power curves, etc.) must be considered. Combining steady-state and transient testing methods can more fully reflect the equipment’s performance under various operating conditions, aiding engineers in making more applicable design decisions.

4.1 Optimal Design of Geometric Structures

After selecting the PAT and conducting detailed performance predictions, if the initial evaluation shows that its efficiency does not meet expectations or there is potential for optimization, an in-depth exploration of optimization design is necessary. As a key step to enhance the operational efficiency, reliability, and economic benefits of PAT, optimization design aims to minimize energy consumption and maintenance costs while meeting specific application requirements through systematic improvements. Structural optimization is the starting point of this process because the internal structure of PAT directly determines fluid flow characteristics and energy conversion efficiency.

Before embarking on optimization design, selecting the appropriate analytical perspective is crucial. For instance, the research by Bai et al. revealed that as flow rate increases, the load on the blades decreases linearly from inlet to outlet, while the net load acting on the blades distributes along the radial position in a concave parabolic shape. This study indicates that during the design or optimization of hydraulic turbines, focusing on the inlet and middle regions of the blade profile would be more beneficial [123], providing a new methodological approach for impeller design or optimization. Additionally, the study by Wang et al. further deepens the understanding of internal flow fields in PAT. Their findings show that the size and position of vortices generated at the impeller inlet remain constant during rotation, but the swirl intensity at the vortex core varies periodically at twice the rotational frequency. These vortices significantly affect pressure fluctuations in PAT, deteriorating operational stability, especially under low-flow conditions where large axial vortices lead to greater power losses near the impeller inlet region [124]. These research outcomes not only aid in understanding the flow field characteristics of PAT but also provide important guidance for blade optimization design.

Such studies lay a solid foundation for subsequent structural optimization design, not only revealing key areas for design improvement but also providing general technical pathways. This enables researchers to more targetedly explore methods for enhancing efficiency, stability, and durability.

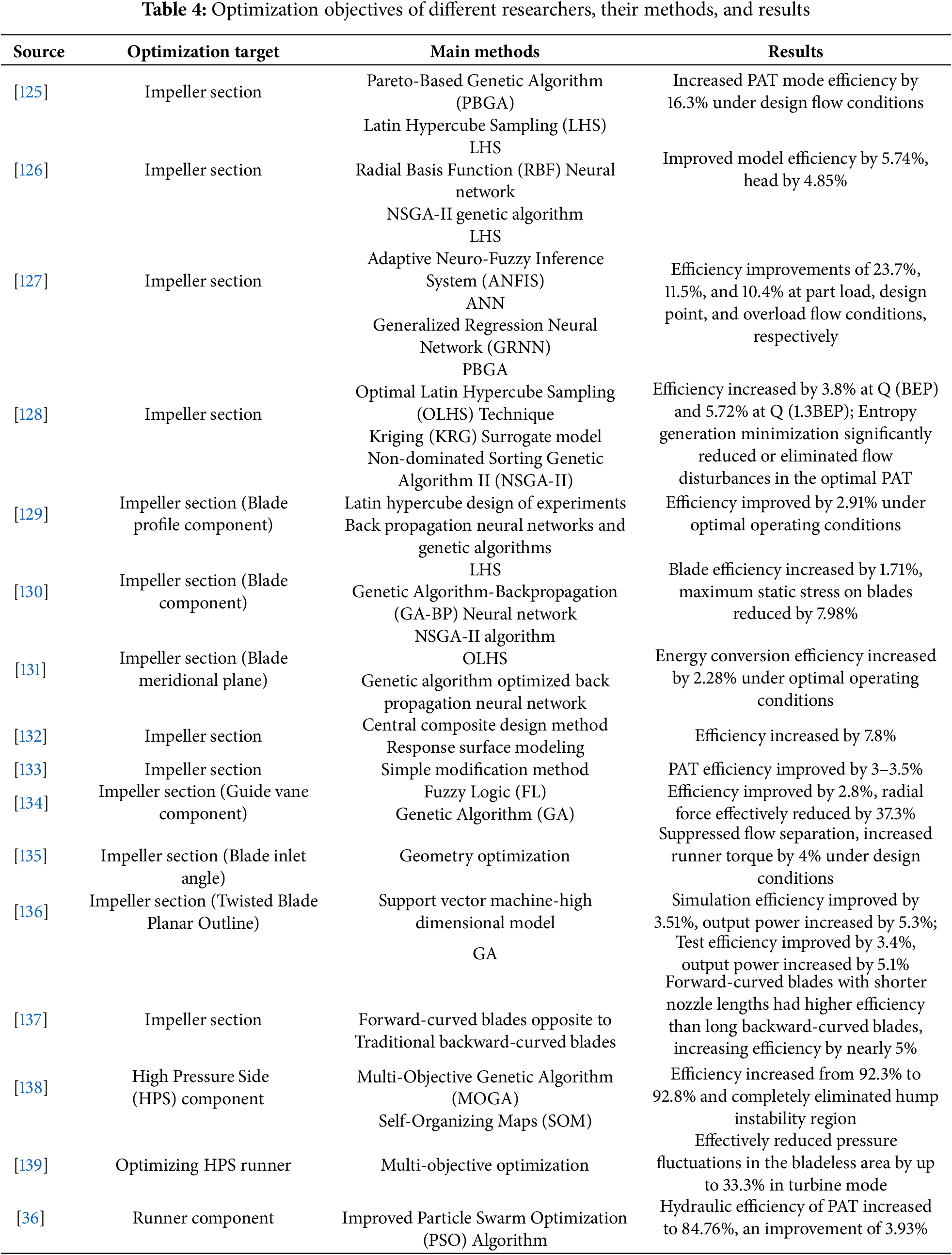

From a practical operational perspective, specific optimization attempts and their outcomes by different researchers on their selected PATs, as shown in Table 4, demonstrate a variety of innovative methods and technologies. These cases not only highlight the diversity of optimization strategies but also confirm that significant advancements in PAT performance can indeed be achieved through proper mathematical modeling, simulation analysis, and experimental validation. For example, by employing advanced computational techniques and optimization algorithms such as the Pareto genetic algorithm, Latin hypercube sampling, radial basis function neural networks, and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems, researchers have successfully improved the efficiency of PATs under various flow conditions while enhancing head and other important performance indicators. These specific optimization examples not only validate the value of theoretical research but also provide successful experiences and technical references for future PAT designs.

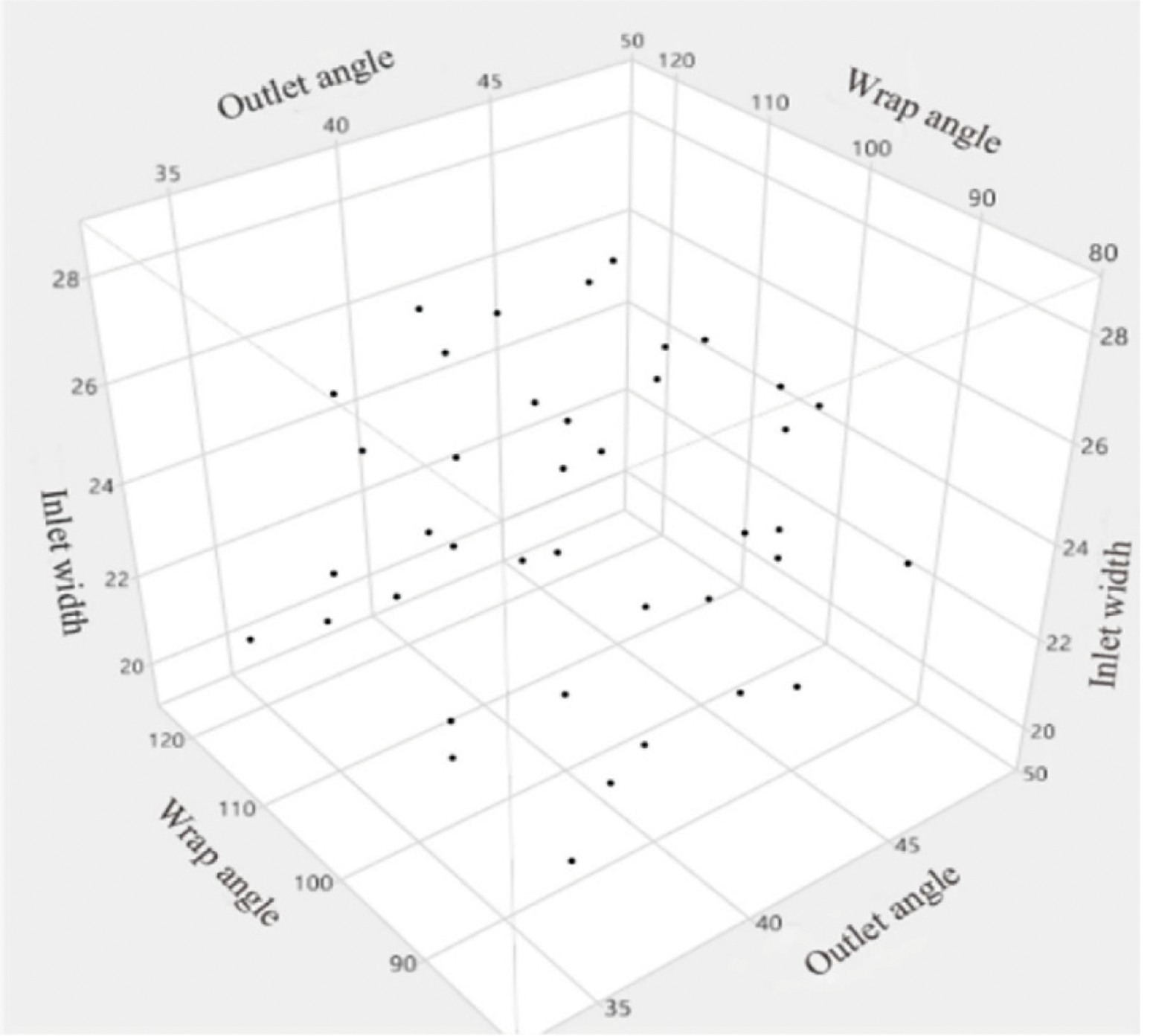

Notably, Latin Hypercube Sampling and multi-objective optimization methods seem to dominate the optimization studies of PATs, being widely applied to enhance key performance indicators such as efficiency, head, and reduction of power loss. LHS reduces the number of experiments needed with its efficient parameter space coverage, as shown in Fig. 24. Multi-objective optimization, on the other hand, provides a range of optimized solutions by addressing conflicting objectives.

Figure 24: Latin hypercube sampling scatter plot Adapted with permission from Ref. [126], Copyright ©2021, Energy Reports publishing

Moreover, these two methods are often used in combination and work synergistically with other advanced algorithms such as genetic algorithms and neural networks. This not only significantly enhances the design and operational performance of PATs but also provides powerful tools and support for solving complex engineering problems. This indicates that, in the field of PAT optimization, the adoption of these integrated methods has become a trend, laying a solid foundation for future research and applications.

During the optimization process, challenges often arise. For instance, when using genetic algorithms, there are multiple objective functions, making it impossible to determine the efficiency of an individual based solely on the value of each function. To address this issue and determine individual efficiency, Wang et al. introduced the expression from Eq. (4) [125].

here, x represents any single individual in the population; y represents the Pareto-efficient individual closest to x; and ||x-y|| denotes the Euclidean distance between x and y.

Although there are various methods for geometric structure optimization, the scope for optimizing the flow passage components of PAT remains limited. Current research primarily focuses on the optimization of the impeller and runner components, with less attention given to other parts such as the volute and draft tube. Moreover, most studies concentrate on using centrifugal pumps as turbines. This suggests that future efforts should place more emphasis on the optimization of other types of pumps and their components to achieve comprehensive performance improvements.

4.2 Optimal Selection of Materials

In addition to geometric structure optimization, the selection and treatment of materials are equally important. Utilizing high-performance materials such as high-strength alloy steel, stainless steel, or composite materials can not only enhance the corrosion resistance and wear resistance of components [140], but also reduce weight, lower startup energy consumption, and minimize mechanical losses during operation. This is because, during the operation of a pump as a turbine, issues such as particle wear, cavitation erosion, and blade impact fracture frequently arise.

Particularly in practical applications, the working medium often consists of complex heterogeneous mixtures containing solid particles, bubbles, and other non-uniform components. Such multiphase flows can lead to unstable and complex flow patterns within the pump, easily triggering vortices, air binding, and sudden flow pattern changes. For equipment operating under harsh conditions, such as in slurry or sandy water environments, wear-related issues become especially severe.

Minemura et al. demonstrated that the combined impact effects of solid particles and bubbles accelerate blade wear progression, particularly under high-velocity and high-concentration conditions, where particle friction and impact significantly intensify equipment wear, directly resulting in reduced turbine output power [141,142]. Further studies indicate that in liquid-solid two-phase flows, particle deposition and imbalances in suspension can induce flow blockages and energy losses [143,144]. The presence of gaseous components may also trigger cavitation, causing a drop in pump head and efficiency [145]. Additionally, bubble collapse can generate localized high-temperature and high-pressure conditions, thereby inducing material corrosion and fatigue failure [146]. Moreover, bubble coalescence and fragmentation exacerbate pressure pulsations and fluid-induced noise [147,148].

To address the above issues, optimizing surface treatment technology and selecting high-performance wear-resistant materials are the core solutions. Studies have shown that TiC-CuNi-Cr composite coatings prepared via high-velocity oxygen fuel (HVOF) spraying on SS316 stainless steel demonstrate significant advantages in particle wear resistance across various operating conditions [149]. Techniques such as boronizing [43] and coating [150] can also effectively improve friction characteristics between fluid and solid surfaces, further reducing energy losses.

Polymer coatings play a critical role in metal surface protection, with graphene incorporation significantly enhancing corrosion resistance. A review by Kausar et al. highlights that polymer/graphene nanocomposites, which block corrosive medium penetration and enhance wear resistance, provide an innovative approach to pump material surface protection [151].

Friction stir processing (FSP) technology forms composite layers by mechanical stirring. For instance, FSP treatment of stainless steel powder on magnesium alloy surfaces significantly improves hardness and corrosion resistance, making it suitable for pumps operating in harsh environments [152]. Surface oxidation treatments, such as chemical or electrochemical methods, enhance corrosion resistance by forming protective oxide layers. For example, NiCrAlY powder-coated SS-304 stainless steel exhibits superior high-temperature oxidation resistance, suitable for high-temperature applications [153]. Sola et al.’s research demonstrates that nitrogen and nitrogen-carbon co-penetration followed by oxidation treatment significantly improves corrosion and wear resistance in 42CrMo4 steel under corrosive conditions [154].

Ion implantation technology modifies material surfaces using high-energy ion beams. Kukareko et al. confirmed that nitrogen ion implantation generates nanoscale nitride particles on austenitic steel surfaces, significantly enhancing hardness and wear resistance [155]. Additionally, the addition of Y2O3 nanoparticles to WC-10Co-4Cr coatings further improves the microhardness and wear resistance of pump impeller steels [156]. Fe-Cr-Ni-B-C coatings prepared via HVOF technology exhibit excellent cavitation wear resistance in distilled water environments, offering new directions for pump material selection [157].

Material selection is equally critical. Aluminum matrix composites reinforced with nano-SiO2 significantly enhance wear resistance and perform well in dynamic load scenarios like wind turbine blades [158,159]. High-entropy alloys (HEAs), renowned for their mechanical strength and thermal stability, are emerging as promising materials for cavitation-resistant coatings. For instance, AlCrFeCoNi alloys demonstrate exceptional cavitation resistance under dynamic impact conditions [160].

Epoxy resin composites with nano-Si3N4 and Al2O3 particles effectively improve corrosion and wear resistance [161]. The wear resistance of composites is primarily attributed to the hardness and distribution of reinforcement phases. For example, silicon carbide (SiC) particles in aluminum matrix composites inhibit micro-cutting and plastic deformation during friction, thereby enhancing wear resistance [162].

In pump equipment, composites are primarily applied to critical components in high-wear and corrosive environments, such as impellers, bearings, and seals. For instance, the application of carbonized composites in impellers exhibits good chemical stability [163], and ceramic matrix composites used in lead-bismuth coolant pump bearings demonstrate excellent resistance to corrosion and wear [164].

Despite extensive research and promising applications, composite materials face challenges. Key issues include weak interfacial bonding between reinforcement phases and matrix materials, which may cause delamination or fracture during pump operation. Additionally, high manufacturing costs hinder large-scale industrial adoption. Future research should focus on optimizing interfacial bonding, developing low-cost manufacturing techniques, and evaluating long-term performance under extreme conditions.

Blade impact fracture primarily results from fatigue failure under high dynamic loads. Solutions include using high-toughness materials and optimizing structural designs. Medium-to-high carbon alloy steels, with their high fatigue strength, are suitable for high-dynamic load conditions. Enhanced toughness and impact resistance can be achieved through optimized heat treatment processes [165]. High-entropy alloy/steel composites exhibit superior fracture resistance under high-speed impacts, significantly improving blade reliability and service life [160]. These materials suppress crack propagation, delaying fatigue failure progression.

While composites offer superior specific strength and fatigue resistance, interfacial delamination and impact damage remain unresolved challenges [166,167]. Systematic material optimization is critical. There are some ways to choose. For instance, segmental sample testing and electrochemical analysis under varying NaCl concentrations can systematically evaluate corrosion resistance for optimal material selection [168].

During pump-turbine operation, cavitation erosion, particle wear, and blade impact fractures are primary failure modes. High-performance materials combined with advanced surface treatments can significantly enhance corrosion resistance, wear resistance, and impact resistance. Optimizing alloy design and welding techniques further improves component reliability and service life. These measures extend equipment lifespan, reduce maintenance costs, and improve operational efficiency [169,170].

Despite progress, challenges persist, such as optimizing interfacial bonding strength, achieving uniform particle distribution in coatings, and developing materials for extreme environments. Future research should explore novel materials, such as high-toughness nanostructured or gradient materials, to enhance fatigue resistance. Advanced manufacturing techniques like additive manufacturing and rapid solidification could also optimize microstructures to prolong fatigue life [171].

Although there has been significant progress in the type selection, performance prediction, and optimization design of Pump as Turbine (PAT), there are still some deficiencies that need to be addressed in the future:

(1) Application of new materials

With the progress in material science, future PAT technology is expected to benefit from the application of new high-performance materials. For instance, the use of high-strength alloy steel, stainless steel, and composite materials can not only improve the equipment’s durability and corrosion resistance but also reduce weight, lower maintenance costs, and extend service life. The development of smart materials like shape memory alloys and self-healing coatings will further enhance PAT’s reliability and adaptability in extreme environments.

(2) Application of advanced design methods

The future will see the introduction of more advanced design methods, such as topology optimization, multi-physics coupling simulations, and AI-based design assistance tools. These new technologies will make PAT designs more precise and efficient, better meeting the needs of specific application scenarios.

(3) Transparent testing research on internal flow characteristics

Current research lacks transparent test rigs for studying internal flow characteristics of PATs. Such studies are crucial for a deeper understanding of internal flow mechanisms, especially when complex gas-liquid two-phase flow phenomena are involved. Transparent test rigs combined with advanced technologies like high-speed photography allow researchers to directly observe previously hard-to-capture phenomena, providing valuable data support for theoretical modeling and numerical simulation.

(4) Comprehensive expansion of research

Significant work has been done by researchers on optimizing PATs, mainly focusing on the impeller components. However, future research should comprehensively cover other key components such as volutes and draft tubes to achieve overall system optimization. This comprehensive research can not only address existing bottlenecks but also promote the improvement of industry technology levels, contributing more wisdom to the development of PAT technology.

PAT technology is currently in a rapid development phase, with future breakthroughs expected through the application of new materials, the development of novel design methods, and widespread adoption in emerging fields. Facing growing market demand, PAT, with its advantages of high efficiency and energy savings, will play an important role in various industries. Strengthening research on internal flow characteristics and expanding focus to all key components will bring broader development prospects for PAT technology. Therefore, PAT not only possesses significant commercial potential but also serves as an essential tool for achieving sustainable development goals. This review summarizes current knowledge on PAT as follows:

(1) In terms of pump selection, centrifugal pumps are ideal for small-scale hydropower generation and industrial energy recovery systems due to their cost-effectiveness. They are suitable for applications with medium to low head and large flow rates. Twin-screw pumps excel in energy recovery when handling high-viscosity fluids, ensuring smooth medium transmission and minimizing energy loss, making them particularly suitable for industries such as chemical and petroleum. Axial-flow pumps are designed for low-head conditions, like hydroelectric power stations or irrigation systems in plain areas, characterized by large flow rates and low heads, achieving efficient liquid transport in gentle water flow scenarios. Mixed-flow pumps combine the advantages of centrifugal and axial-flow pumps, demonstrating high flexibility and adaptability in high-head and high-flow environments, suitable for applications requiring a balance between pressure and flow. Although still in the exploratory stage, plunger pumps have shown significant potential in precision control and hydrostatic transmission, promising broader application prospects in extremely precision-demanding scenarios in the future.

(2) In terms of performance prediction for PAT, to enhance the accuracy of PAT performance evaluation tools, a combination of theoretical calculations, CFD numerical simulations, and experimental testing can be utilized. Traditional conversion factors, when combined with modern machine learning techniques, improve prediction accuracy and reliability, while CFD technology is indispensable for dealing with complex geometries and boundary conditions. Meanwhile, experimental testing plays a crucial role in verifying model accuracy and identifying problem areas, ensuring the effectiveness of design schemes through practical operation tests.

(3) In terms of optimization design for PAT, multi-objective optimization methods, such as Latin Hypercube Sampling and Genetic Algorithms, can enhance the design performance of PAT when used in conjunction. Geometric structure and material optimization, including the use of high-performance materials and surface treatments, improve corrosion resistance and wear resistance, reduce weight, and minimize mechanical losses. These measures collectively advance pump technology and its applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The research was financially supported by Science and Technology Project of Quzhou (Nos. 2023K256, 2023NC08, 2022K41), Research Grants Program of Department of Education of Zhejiang Province (Nos. Y202455709, Y202456243), and Hunan Province Key Field R&D Plan Project (No. 2022GK2068).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Yanjuan Zhao and Lianghuai Tong; methodology, Xiao Sun; formal analysis, Huifan Huang; investigation, Haibin Lin; writing—original draft preparation, Yuliang Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Thoma D, Kittredge CP. Centrifugal pumps operated under abnormal conditions. Power. 1931;73:881–4. [Google Scholar]

2. Nejadali J. Analysis and evaluation of the performance and utilization of regenerative flow pump as turbine (PAT) in Pico-hydropower plants. Energy Sustain Dev. 2021;64(1):103–17. doi:10.1016/j.esd.2021.08.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yu W, Zhou P, Miao Z, Zhao H, Mou J, Zhou W. Energy performance prediction of pump as turbine (PAT) based on PIWOA-BP neural network. Renew Energy. 2024;222:119873. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.119873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pugliese F, De Paola F, Fontana N, Giugni M, Marini G. Experimental characterization of two Pumps as Turbines for hydropower generation. Renew Energy. 2016;99(5):180–7. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2016.06.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Fontanella S, Fecarotta O, Molino B, Cozzolino L, Della Morte R. A performance prediction model for pumps as turbines (PATs). Water. 2020;12(4):1175. doi:10.3390/w12041175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. De Marchis M, Milici B, Volpe R, Messineo A. Energy saving in water distribution network through pump as turbine generators: economic and environmental analysis. Energies. 2016;9(11):877. doi:10.3390/en9110877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Carravetta A, Fecarotta O, Sinagra M, Tucciarelli T. Cost-benefit analysis for hydropower production in water distribution networks by a pump as turbine. J Water Resour Plan Manag. 2014;140(6):04014002. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)WR.1943-5452.0000384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Alberizzi JC, Renzi M, Righetti M, Pisaturo GR, Rossi M. Speed and pressure controls of pumps-as-turbines installed in branch of water-distribution network subjected to highly variable flow rates. Energies. 2019;12(24):4738. doi:10.3390/en12244738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Adu D, Jianguo D, Darko RO, Boamah KB, A Boateng E. Investigating the state of renewable energy and concept of pump as turbine for energy generation development. Energy Rep. 2020;6(3):60–6. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2020.08.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Dong W, Dong Y, Sun J, Zhang H, Chen D. Analysis of the internal flow characteristics, pressure pulsations, and radial force of a centrifugal pump under variable working conditions. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Mech Eng. 2023;47(2):397–415. doi:10.1007/s40997-022-00533-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang L, Wang D, Yang G, Pan Q, Shi W, Zhao R. Optimization of hydraulic efficiency and internal flow characteristics of a multi-stage pump using RBF neural network. Water. 2024;16(11):1488. doi:10.3390/w16111488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li W, Yang Q, Yang Y, Ji L, Shi W, Agarwal R. Optimization of pump transient energy characteristics based on response surface optimization model and computational fluid dynamics. Appl Energy. 2024;362(4):123038. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2024.123038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Wang Z, Wang W, Wang D, Song Y. Numerical analysis of energy loss characteristics of guide vane centrifugal pump as turbine. Front Energy Res. 2024;12:1410679. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2024.1410679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhu Z, Gu Q, Chen H, Ma Z, Cao B. Investigation and optimization into flow dynamics for an axial flow pump as turbine (PAT) with ultra-low water head. Energy Convers Manag. 2024;314:118684. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2024.118684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lei S, Cheng L, Yang W, Xu W, Yu L, Luo C, et al. Dynamic multiscale pressure fluctuation features extraction of mixed-flow pump as turbine (PAT) and flow state recognition of the outlet passage using variational mode decomposition and refined composite variable-step multiscale multimapping dispersion entropy. Energy. 2024;305(7):132230. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.132230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Lin T, Zhang J, Wei B, Zhu Z, Li X. The role of bionic tubercle leading-edge in a centrifugal pump as turbines(PATs). Renew Energy. 2024;222(1):119869. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2023.119869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Liu M, Tan L, Cao S. Performance prediction and geometry optimization for application of pump as turbine: a review. Front Energy Res. 2022;9:818118. doi:10.3389/fenrg.2021.818118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Souza DES, Mesquita ALA, Blanco CJC. Pump-as-turbine for energy recovery in municipal water supply networks. A review. J Braz Soc Mech Sci Eng. 2021;43(11):489. doi:10.1007/s40430-021-03213-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Carravetta A, Del Giudice G, Fecarotta O, Morani MC, Ramos HM. A new low-cost technology based on pump as turbines for energy recovery in peripheral water networks branches. Water. 2022;14(10):1526. doi:10.3390/w14101526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li W. Vortex pump as turbine for energy recovery in viscous fluid flows with Reynolds number effect. J Fluids Eng. 2022;144(2):021207. doi:10.1115/1.4051313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Adu D, Du J, Darko RO, Baffour GE, Asomani SN. Overcoming CO2 emission from energy generation by renewable hydropower-The role of pump as turbine. Energy Rep. 2023;9(Supple. 6):114–8. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2023.09.155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Quaranta E, Muntean S. Wasted and excess energy in the hydropower sector: a European assessment of tailrace hydrokinetic potential, degassing-methane capture and waste-heat recovery. Appl Energy. 2023;329(6):120213. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2022.120213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sari MA, Badruzzaman M, Cherchi C, Swindle M, Ajami N, Jacangelo JG. Recent innovations and trends in in-conduit hydropower technologies and their applications in water distribution systems. J Environ Manag. 2018;228(11):416–28. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.08.078. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Wang P, Luo X, Chen S, Cai Q, Lu J. Energy saving application of variable speed auxiliary pump plus hydro turbine in circulating cooling water system. J Phys: Conf Ser. 2021;2029(1):012070. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/2029/1/012070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Spedaletti S, Rossi M, Comodi G, Salvi D, Renzi M. Energy recovery in gravity adduction pipelines of a water supply system (WSS) for urban areas using Pumps-as-Turbines (PaTs). Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2021;45(4):101040. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2021.101040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Crespo Chacón M, Rodríguez Díaz JA, García Morillo J, McNabola A. Pump-as-turbine selection methodology for energy recovery in irrigation networks: minimising the payback period. Water. 2019;11(1):149. doi:10.3390/w11010149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jafari R, Khanjani MJ, Esmaeilian HR. Pressure management and electric power production using pumps as turbines. J AWWA. 2015;107(7):E351–63. doi:10.5942/jawwa.2015.107.0083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Muhammetoglu A, Nursen C, Karadirek IE, Muhammetoglu H. Evaluation of performance and environmental benefits of a full-scale pump as turbine system in Antalya water distribution network. Water Supply. 2018;18(1):130–41. doi:10.2166/ws.2017.087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Kramer M, Terheiden K, Wieprecht S. Pumps as turbines for efficient energy recovery in water supply networks. Renew Energy. 2018;122:17–25. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2018.01.053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Crespo Chacón M, Rodríguez Díaz JA, García Morillo J, McNabola A. Hydropower energy recovery in irrigation networks: validation of a methodology for flow prediction and pump as turbine selection. Renew Energy. 2020;147(4):1728–38. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2019.09.119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Pérez-Sánchez M, Fernandes JFP, Costa Branco PJ, López-Jiménez PA, Ramos HM. PATs behavior in pressurized irrigation hydrants towards sustainability. Water. 2021;13(10):1359. doi:10.3390/w13101359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Roux DL. Energy recovery from incoming high pressure cold water in deep level mines. In: 2012 Proceedings of the 9th Industrial and Commercial Use of Energy Conference; 2012; IEEE. p. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

33. Jain SV, Patel RN. Investigations on pump running in turbine mode: a review of the state-of-the-art. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2014;30(5–6):841–68. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2013.11.030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]