Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Effect of Polymer-Assisted Abrasive Jets on the Surface Quality of Cut Marbles

School of Energy and Mechanical Engineering, Hunan University of Humanities, Science and Technology, Loudi, 417000, China

* Corresponding Author: Dong Hu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Effect of Materials Surface Properties on Fluid Dynamics Behavior)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(7), 1641-1655. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.065820

Received 22 March 2025; Accepted 09 May 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

To address the challenges of poor surface quality and high energy consumption in marble cutting, this study introduces an auxiliary abrasive jet cutting technology enhanced by the use of polyacrylamide (PAM) as a drag-reducing additive. The effects of feed rate (50–300 mm/min), polymer concentration (0–0.5 g/L), and nozzle spacing (4–12 mm) on kerf width and surface roughness are systematically investigated through an orthogonal experimental design. Results reveal that feed rate emerges as the most significant factor (p < 0.01), followed by PAM concentration and nozzle spacing. The optimal set of parameters, comprising a 200 mm/min feed rate, 0.3 g/L PAM concentration, and 6 mm nozzle spacing, achieves the narrowest kerf width (0.867 mm) and the lowest surface roughness (10.220 μm). Analysis of the underlying mechanisms demonstrates that PAM enhances the energy efficiency of the jet by suppressing turbulent pulsations and increasing fluid viscoelasticity, thereby minimizing energy loss during the cutting process.Keywords

Traditional marble cutting relies on mechanical processing methods such as diamond frame saws, which are widely used but have significant drawbacks: high section roughness (Ra 15–25 μm) due to saw blade wear, large fluctuations in saw kerf width (±0.3 mm), and material loss rates of more than 15% [1,2]. Abrasive Waterjet (AWJ) technology realizes non-contact cutting using high-pressure water (200–400 MPa) carrying abrasive particles (e.g., 80 mesh garnet) that impact the material at ultra-high speeds (>300 m/s) with the advantages of no thermal damage and long tool life [3]. However, the quality of the cut is governed by multiple factors:

Process parameters: Cutting speed (workpiece travel speed) affects the jet residence time; too fast will lead to insufficient energy; nozzle spacing (the vertical distance from the jet outlet to the workpiece surface) exceeds 8 mm, and the core energy of the jet is attenuated by 30%, which triggers a surge of roughness in the lower cutting zone [4,5].

Fluid properties: the turbulent pulsation of the clear water jet leads to uneven distribution of abrasive particles [6,7], resulting in fluctuations in the width of the kerf and surface streaking defects; while polymer additives (e.g., polyacrylamide (PAM)) can improve the stability of the jet, the kinetic mechanism of the concentration thresholds (e.g., the critical entanglement concentration of 0.3 g/L) is not systematically analyzed by the existing studies [8,9].

In international research, Lei et al. [10] optimized the cutting parameters of stainless steel by the Taguchi method to reduce the roughness by 12%, but did not involve the stone; Pei and Bai [11] confirmed that 0.2–0.4 g/L PAM can narrow the kerf by 10%–15%, but the micro-mechanism of how the viscoelastic fluid regulates the impact trajectory of abrasive particles (e.g., the standard deviation of the velocity of the core area is reduced by 32%) has not yet been clarified. Especially in stone cutting, the international research on polymer-assisted jets is still a gap that needs to be filled. Zuo [12] found that when cutting brittle materials, the target distance exceeds the limit, which will lead to a sudden increase in the roughness of the lower cutting zone due to the effect of impact crushing, but did not combine with the polymer modification.

Ra (arithmetic mean deviation of contour) is the core index of surface roughness [13,14], defined as the arithmetic mean of the absolute value of the contour deviation (unit: μm) within the sampling length, the smaller the value indicates that the surface is smoother [15]. Agus et al. [16] proposed a multi-channel jet strategy to improve the efficiency but did not solve the problem of the single-channel jet energy attenuation and the synergy of the polymer.

Research objectives and methodology: To address the problems of poor surface quality (Ra > 15 μm) and high energy consumption (the traditional process requires more than 300 MPa pressure) of marble cutting, PAM was introduced as a drag-reducing additive in this study, and its effects on kerf width and surface roughness (Ra) were systematically analyzed by a three-factor mixed-level orthogonal test (cutting speed, PAM concentration, and nozzle spacing), revealing the effect of viscoelastic fluids on the surface roughness of marble cutting. Through the three-factor mixed level orthogonal test (cutting speed, PAM concentration, and nozzle spacing), its influence on kerf width and surface roughness (Ra) was systematically analyzed to reveal the regulation mechanism of viscoelastic fluid on the energy utilization of jet, and the process parameters were optimized to achieve high-precision and low-energy cutting.

2 Test Environment and Test Materials

2.1 Test Conditions and Equipment

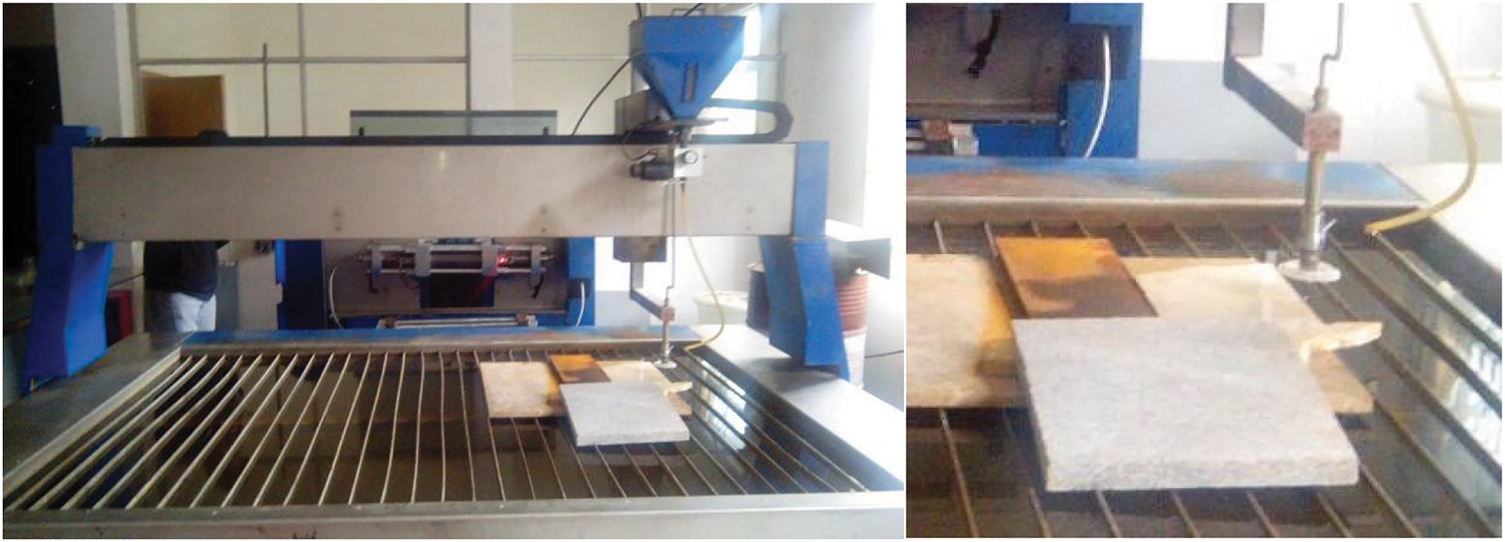

Gantry type high pressure abrasive water jet cutting machine (Fig. 1), a post-mixed abrasive jet system is used, with core components including:

Figure 1: Gantry type high pressure abrasive water jet cutting machine

Water nozzle: 0.3 mm inner diameter, generating a 250 MPa high-pressure water jet;

Focusing tube (abrasive nozzle): inner diameter 0.89 mm, abrasive (80 mesh garnet, density 3.9–4.1 g/cm3) through the negative pressure inhalation, and high-pressure water in the tube mixing accelerated and then sprayed (Fig. 2 schematic).

Figure 2: Diluted aqueous solution of polyacrylamide (PAM)

The equipment is controlled by LionMed CNC software, and the nozzles are used in combination for ≤3 h to control wear, with a single cutting depth of 20 mm, a kerf length of 50 mm, and a spacing of ≥5 mm between neighboring kerfs to avoid the superposition of heat-affected zones.

The physical and mechanical properties of marble are shown in Table 1. Polyacrylamide (PAM) with a molecular weight of 12 million was chosen as the additive, and its aqueous solution has significant viscoelasticity (Fig. 2). The 1 g/L masterbatch was prepared with tap water at 10°C, and diluted to the target concentration after thorough stirring and standing (≥40 min).

In an economic comparison, the cost of PAM addition was only US$0.3/1000 L, significantly lower than the operational cost of the traditional abrasive waterjet (AWJ) without PAM (which incurs higher energy consumption and material loss). Combined with the 30% narrowing of the kerf width (from 1.5 to 0.867 mm), the utilization rate of a single square meter of marble plate was increased from 75% to 85% (equivalent to saving 0.1 m2 of material per m2 of processing). This reduces the need for 2–3 times post-cutting sanding, decreasing processing time by 60%. Compared with the conventional AWJ (without PAM), the overall processing cost was reduced by 42%, especially suitable for precision processing of high-end marble with a unit price of >US$285.71/m2 (calculated at an exchange rate of 1 US$ = 7 RMB), yielding remarkable economic benefits.

Mineralogical identification: Through the polarized light microscope to observe the mineral composition, it is determined that the test material is marble, the main component of which is calcite (more than 95%), with a small amount of dolomite, which is in line with the definition of marble in the “Unified Numbering of Natural Stones” of GB/T 17670-2022 (CaCO3 is the main mineral, with the hardness of 3–4, and it forms a clear distinction with limestone (mainly CaCO3 but different in structure). CaCO3-dominated mineral, hardness 3–4 grade, and limestone (CaCO3-dominated but with different structure) form a clear distinction).

3.1 Experimental Program Design

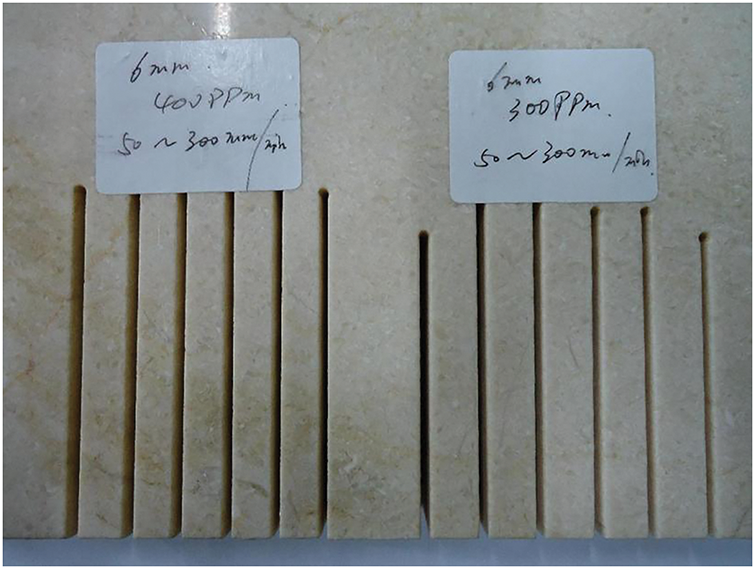

The synergistic effect of process parameters significantly affects the cutting effectiveness of abrasive jets. Although the adjustment of a single parameter can trigger the cutting response, it is difficult to reveal the multivariate coupling effect. For this reason, a three-factor mixed-level orthogonal experimental design (L25 orthogonal table) was adopted, and the specific parameters were set as follows:

Cutting speed (Factor A, 6 horizontal): 50, 100, 150, 200, 250, 300 mm/min, defined as the movement speed of the workpiece along the cutting direction, which directly determines the residence time of the jet on the same point (residence time = kerf width/cutting speed) and affects the cumulative erosion energy;

Nozzle spacing (Factor B, 5 horizontal): 4, 6, 8, 10, 12 mm, defined as the perpendicular distance between the outlet end face of the focusing tube and the marble surface (Fig. 2), controls the degree of jet diffusion—the smaller the spacing, the more concentrated the energy in the core area of the jet, and vice versa, the diffusion is increased, and the energy is attenuated (e.g., at 12 mm, core The smaller the distance, the more concentrated the energy in the core of the jet, and conversely, the greater the diffusion and energy attenuation (e.g., 45% attenuation of core velocity at 12 mm);

PAM concentration (Factor C, 4 levels): 0 (water control), 0.3, 0.4, 0.5 g/L, to improve the jet stability and inhibit turbulent pulsation by adjusting the solution viscoelasticity (modulus of elasticity, G′, increased from 0.1 to 0.47 Pa at 0.3 g/L).

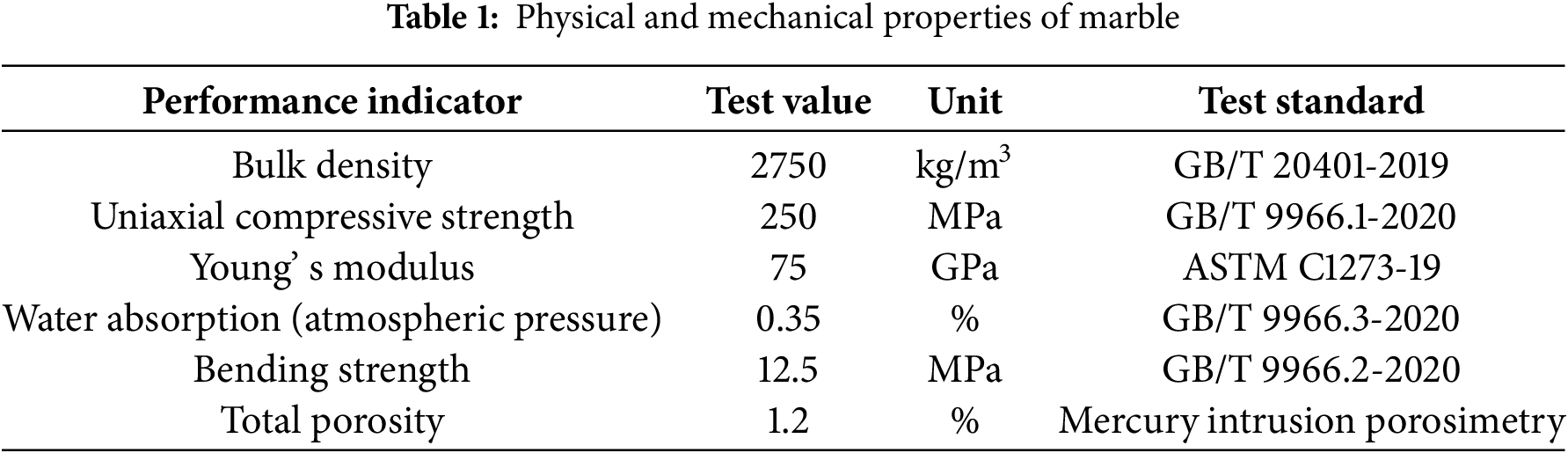

The L25 (61 × 51 × 41) mixed orthogonal matrix (Table 2) was constructed, and the kerf width (Kerf Width, averaged over 15 points along the length of the kerf with an accuracy of ±0.01 mm) and the surface roughness of the undercut area (Ra, measured at 5 points, Hommel T8000 RC contouring instrument, with a sampling length of 30 mm, and accuracy of ±0.5 μm) were used as the evaluation indexes, which were combined with the SPSS multifactor ANOVA method. The weights of each factor were quantified by SPSS multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA).

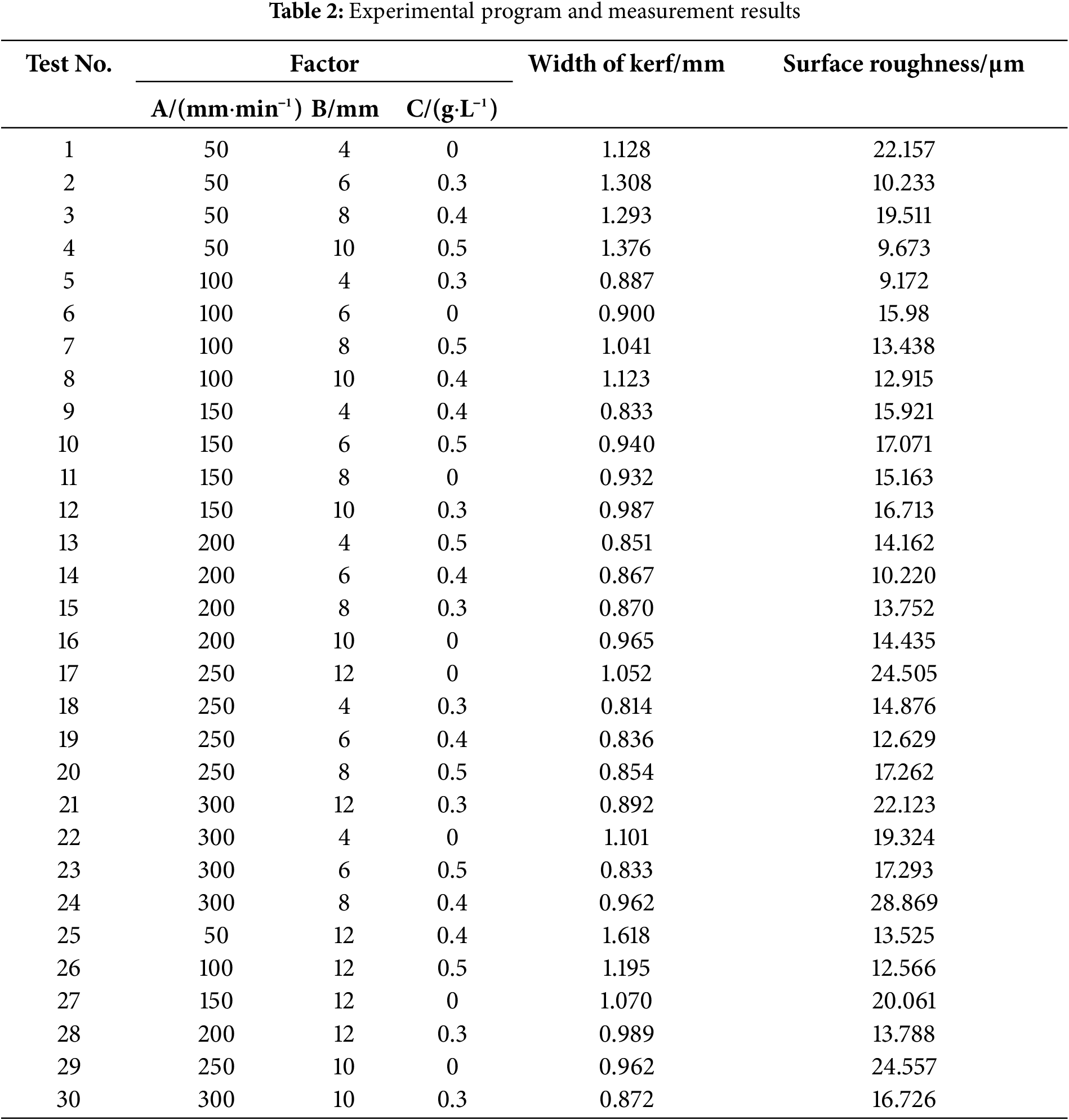

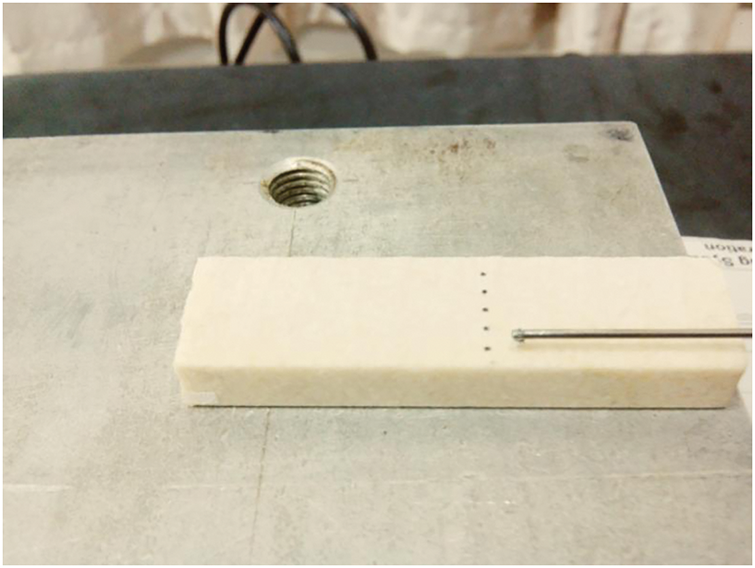

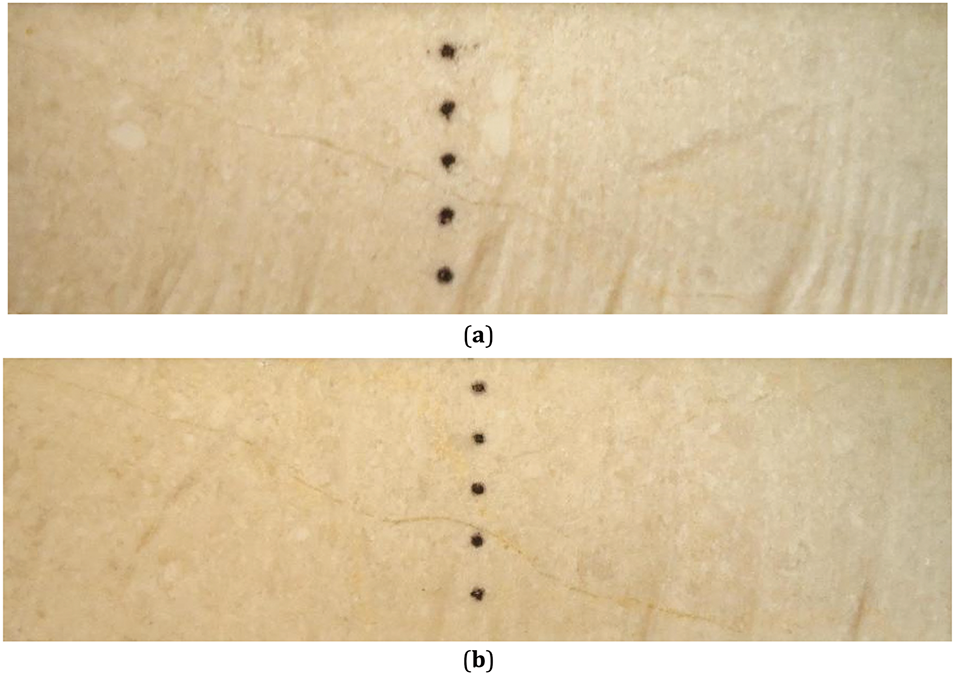

Measurement of kerf width: 15 measurement points are marked for each kerf and the average value is taken (Fig. 3). Surface roughness measurement: Mark 5 measurement points along the cutting direction and take the average value of three measurements, with a measurement range of 400 μm and a probe speed of 0.5 mm/s. The surface roughness is measured by a probe with a speed of 0.5 mm/s.

Figure 3: Marking the cut seam

3.3 Surface Roughness Measurement

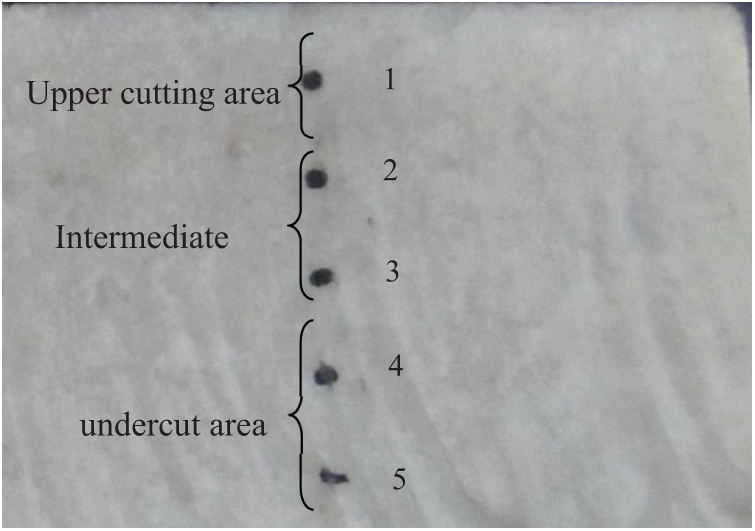

The surface roughness of the cut specimens was measured using a Hommel T8000 RC Roughness Profiler. To ensure the comparability of data between samples, each cut specimen was positioned in a standardized way: 5 measurement points were marked uniformly along the length of the specimen (Fig. 4). No less than 3 measurements were taken for each group and the mean value was calculated to reduce the random error. The specific measurement parameters were set as follows: measurement range of 400 μm, probe travel speed of 0.50 mm/s, and sampling length of 30 mm, which was defined as the length of the baseline intercepted along the contour direction and used for the calculation of roughness characteristic parameters.

Figure 4: Measurement of marble cutting piece

The cross-section observation of the cut specimens shows a significant morphological evolution along the cutting depth direction (Fig. 5). The upper cutting area shows a smooth grinding surface, which is due to the continuous cutting effect of high-speed abrasive grains; the middle area shows a diagonal stripe structure, which belongs to the deformation grinding area and is triggered by the change of the impact angle of the abrasive grains; and the lower cutting area forms a dense group of craters, which belongs to the reflective erosion area and is originated from the impact crushing effect after the jet energy is attenuated. In view of the increasing trend of the roughness parameter along the depth direction, this study chooses measurement point 5 in the lower cutting zone as the main object of roughness analysis.

Figure 5: Surface of cut material

4 Data Processing and Result Analysis

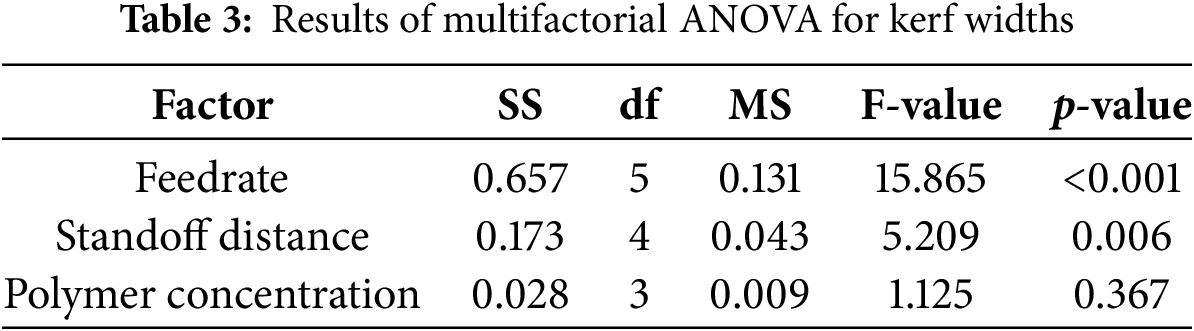

It was found by multilevel ANOVA that differences in the number of different factor levels would lead to deviations in the ordering of the influencing factors. To accurately quantify the influence weights of each parameter, multifactor ANOVA was performed using SPSS software (Table 3). The results showed that the feed rate (F = 15.865) and nozzle spacing (F = 5.209) were statistically significant (p < 0.05) on kerf width, while the effect of polymer concentration did not reach a significant level (p = 0.367).

The cutting action of an abrasive jet results from a dual mechanism of particle on material: vertical impact stress and horizontal shear stress.

The cutting speed directly determines the residence time of the jet, which in turn affects the cumulative erosion energy of the material. A reduction in residence time (e.g., a 6-fold reduction in residence time by increasing from 50 to 300 mm/min) leads to a significant narrowing of the kerf width (negative correlation, Pearson’ s correlation coefficient r = −0.91), by the “residence time-energy model” proposed by Hou et al. [17]. When the cutting speed exceeds 200 mm/min, the erosion energy per unit area is below the material damage threshold, resulting in a decrease in cutting efficiency.

Nozzle spacing affects the effective area of action by changing the jet diffusion angle. In the range of 4–12 mm, the kerf width increased linearly with increasing pitch (goodness of fit R2 = 0.92), which is consistent with Pei and Bai’s [11] theory of jet diffusion: for every 1 mm increase in pitch, the diffusion angle increased by 2°, and the energy density in the core area was attenuated by about 5%, resulting in an average increase of 0.05 mm in kerf width.

Polymer concentration indirectly affects cutting efficiency by regulating the suspension stability of the abrasive. At a concentration of 0.3 g/L, the viscoelastic effect of PAM molecules elevated the concentration of abrasive particles by 15% in the core zone of the jet (22% reduction in the edge zone), creating a “focusing effect” [18], and narrowing the kerf width by 18% compared with that of the clear water group (from 1.128 to 0.925 mm). However, the particle agglomeration triggered by excessive concentration (>0.3 g/L) reduced the effective number of abrasive grains per unit volume, and the kerf width inversely increased by 5%–8%.

This result is consistent with the hydrodynamic theory [19,20]: the shear stress is positively correlated with the jet velocity gradient, while the polymer concentration mainly contributes to the kerf width indirectly by changing the fluid viscosity (from 0.001 to 0.005 Pa s at 0.3 g/L) and turbulent kinetic energy (30% reduction of k value in the core region).

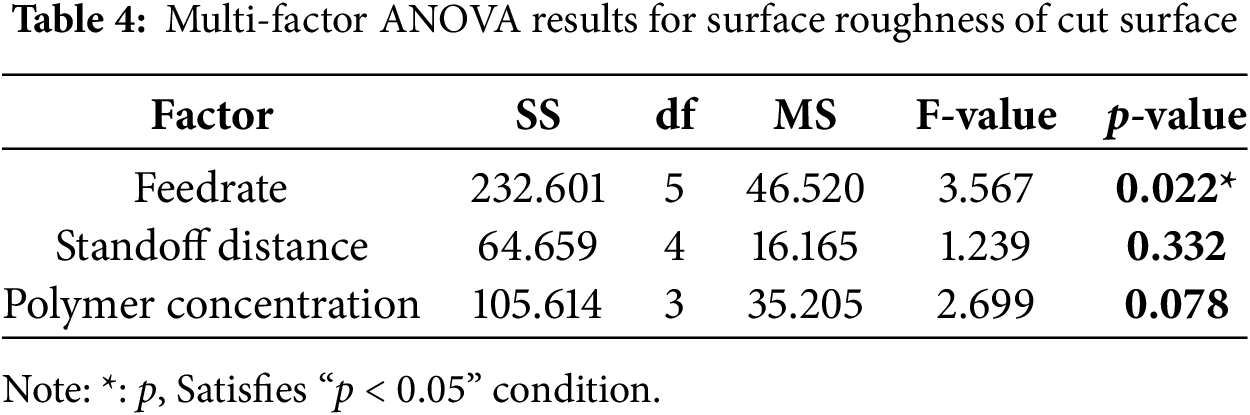

The results of the analysis of the surface roughness of the cut surface are shown in Table 4. The results show that for the effect of surface roughness on the cut surface, the F-value of the cutting speed > the F-value of the polymer concentration > the F-value of the target distance. Cutting speed produces a significant difference relationship on surface roughness (p < 0.05).

The size of the cutting speed is the determining factor of the time that the jet acts on the same position of the workpiece, and the time that the jet acts on the workpiece affects the surface roughness of the cut surface of the workpiece, so the size of cutting speed affects the surface roughness of the cut surface. The shorter the action time, the smaller the abrasive particles play a grinding role in the workpiece, the greater the roughness. Therefore, the faster the cutting speed, the greater the surface roughness of the cut surface. As far as the polymer concentration and target distance are concerned, the higher the polymer concentration is, the better the effect of the jet on the surface of the workpiece is, and the smaller the roughness is. The larger the target distance, the smaller the effect of the jet on the surface of the workpiece, the larger the roughness, and with the gradual increase of the target distance, the force of the jet on the workpiece decreases, and the effect on the surface roughness also decreases. Therefore, the order of influence on the surface roughness is cutting speed, polymer concentration, and target distance.

4.3 Comparative Analysis at Different Cutting Speeds

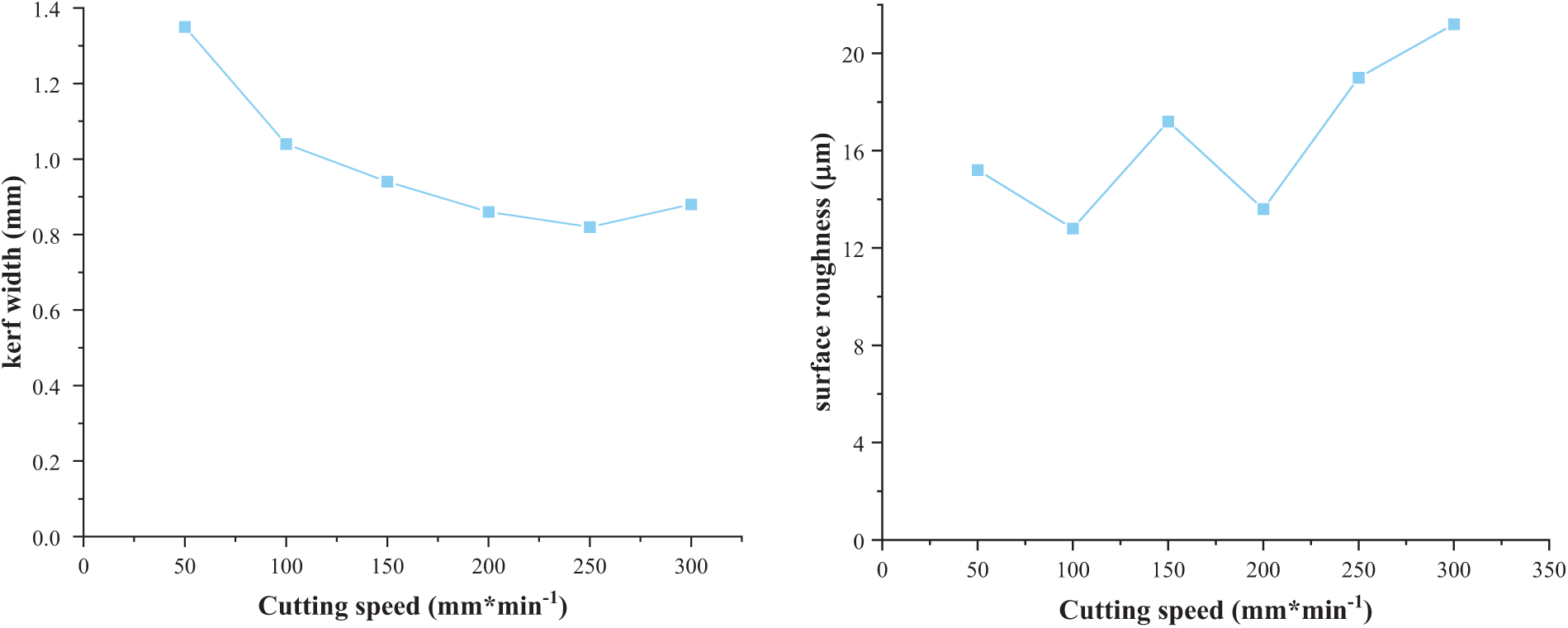

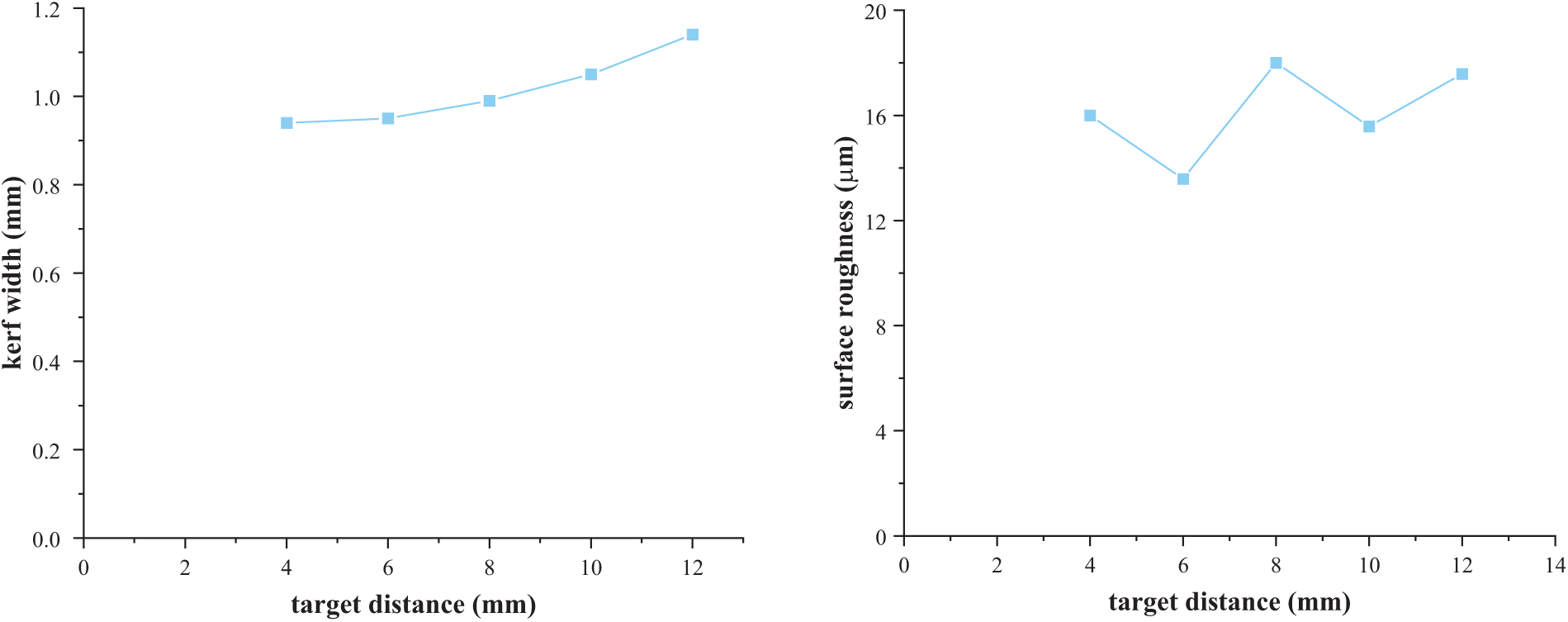

The main effect plots of the factors generated by SPSS software (Figs. 6–8) show that the optimal process combination within the range of test parameters is: a feed rate of 200 mm/min, PAM concentration of 0.3 g/L, and nozzle spacing of 6 mm, at which the kerf width reaches the minimum value of 0.867 mm and the surface roughness is the lowest (10.220 μm).

Figure 6: Main effect of the average value of water at different cutting speeds

Figure 7: Main effects of water averaging at different target distances

Figure 8: Main effect of different water average values of polymer concentration

The main effect curve of feed rate shown in Fig. 6 has a typical “V” shape: the width of the kerf decreases rapidly with the increase of feed rate and then rises slowly, and reaches the extreme value in the 200–250 mm/min region. The surface roughness parameter shows a clear positive correlation (R2 = 0.73), but the roughness fluctuation along the depth of cut is the smallest at 200 mm/min (σ = 1.15 μm), which indicates that the energy distribution of the jet is the most balanced at this rate. This phenomenon is attributed to the dual regulation of the feed rate on the impact frequency and energy density of the abrasive grains: the impact frequency is high but the energy density is low at low speeds, and the energy density is high but the action time is short at high speeds, and 200 mm/min is the optimal balance between the two.

At lower feed rates, the impact frequency of the abrasive grains is high but the single impact energy is low, and this high-frequency, low-energy mode of action results in larger kerf widths and relatively smooth surfaces. When the feed rate is increased to a critical value (>200 mm/min), the impact frequency of the abrasive grains is significantly reduced, and although the kerf width becomes narrower due to the increased energy density, the surface roughness increases due to the weakening of the abrasive grains’ cutting action. It is worth noting that at a constant feed rate, the kinetic energy of the abrasive grains decayed exponentially (decay coefficient k = 0.035 mm−1) with the increase of the cutting depth, resulting in a gradual change of the cutting mechanism from plastic deformation to brittle crushing in the middle and lower cutting zones, which is manifested by the increase of surface roughness along the depth (with a gradient up to 1.25 μm/mm), which is consistent with the experimental observation of Zuo [12].

4.4 Comparative Analysis at Different Target Distances

Fig. 7 illustrates the main effect curve of nozzle spacing on cutting performance. Statistical analysis shows that the width of the kerf increases linearly with increasing nozzle spacing (R2 = 0.92), whereas the surface roughness parameter shows a parabolic variation of decreasing and then increasing (p < 0.01). This phenomenon stems from the dual effect of nozzle spacing on jet diffusion: increasing the spacing extends the region of action, but at the same time weakens the energy density in the core region. When the spacing exceeded a critical value (8 mm), the attenuation of the abrasive impact energy exceeded 30%, resulting in a significant reduction in cutting efficiency. Further increasing the spacing to 12 mm resulted in a 45% attenuation of the jet core velocity, which led to a sharp increase in roughness (ΔRa = +8.3 μm), which is in good agreement with the jet energy attenuation model proposed by Chen et al. [9]. This result reveals that there exists an optimal nozzle spacing interval (6–8 mm), in which the jet diffusion and energy attenuation reach a dynamic balance.

4.5 Comparative Analysis at Different Polymer Concentrations

The effect of PAM concentration on the cutting quality shows typical nonlinear characteristics (Fig. 8), and the core mechanism is closely related to the critical entanglement concentration (C+) of the polymer solution. When the concentration is lower than 0.3 g/L, the PAM molecular chains are dispersed in the aqueous solution in the form of isolated nematic clusters (Fig. 2a), and the intermolecular interactions are weak, which can only inhibit the turbulent pulsation through the weak viscous drag (η = 0.002 Pa s), and the enhancement of the stability of the jet is limited. When the concentration reached 0.3 g/L, the polymer chain segments formed a dynamic crosslinked network through the hydrogen bonding of amide groups (Fig. 2b), and the solution viscoelasticity changed qualitatively: the elastic modulus (G′) increased from 0.1 to 0.47 Pa, and the viscous modulus (G″) increased from 0.08 to 0.23 Pa, which showed obvious elasticity-dominated characteristics (G′ > G″). This viscoelastic transition reduces the standard deviation of the velocity in the core region of the jet by 32%, effectively suppressing the interference of turbulent eddies on the trajectory of the abrasive particles, and thus improving the directionality of the abrasive particle impact (Fig. 9b).

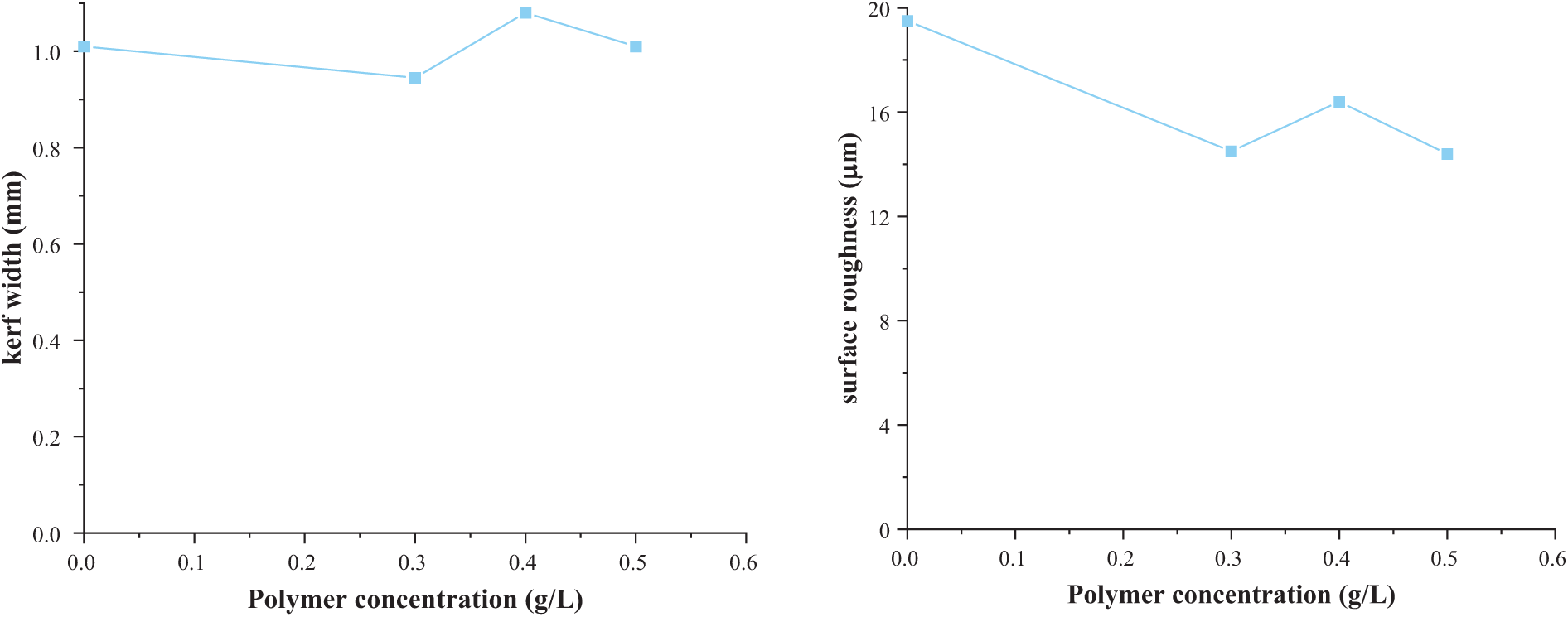

Figure 9: Comparison of cutting surface morphology at different polymer concentrations. (a) Cutting speed = 200 mm/min, target distance = 6 mm, polymer concentration = 0.4 g/L; (b) Cutting speed = 200 mm/min, target distance = 6 mm, polymer concentration = 0.3 g/L

Above 0.3 g/L, excessive entanglement of molecular chains triggered a shear thickening effect (the consistency coefficient K increased from 0.005 to 0.008 Pa sn, and the flow index n decreased from 0.8 to 0.6), which led to a surge in the jet boundary-layer drag, and a 15% increase in the inhomogeneity of the abrasive particle velocity distribution at the exit of the nozzle (Fig. 8). At this point, despite the increase in solution viscosity, the abrasive particle suspension stability decreases and the effective impact energy per unit volume decreases instead, as evidenced by a 5%–8% increase in the width of the kerf and a 12%–18% increase in the surface roughness. This threshold is highly consistent with the theoretical model of polymer turbulence drag reduction proposed by Yusufi et al. [15], i.e., the viscoelastic effect dominates when Deborah number (De = λ/τ > 1), and the drag reduction effect is significantly attenuated when De < 1.

4.6 Control Analysis of Test Results

The feed rate-kerf width curves in Fig. 10 show that at a PAM concentration of 0.3 g/L, the kerf widths at all feed rates were significantly smaller than those of the 0.4 g/L group (ΔW = −0.08 to −0.12 mm). The negative correlation between the kerf width and the feed rate at the same concentration (r = −0.91) is directly related to the reduction of erosion energy due to the shortened residence time of the jet.

Figure 10: Comparison of kerf width at different cutting speeds (target distance 6 mm)

The comparison of the surface morphology in Fig. 9 reveals the microscopic mechanism of the concentration effect: the cut surface of the 0.3 g/L group shows a characteristic comb-like texture, and its spacing uniformity is increased by 40% compared with that of the 0.4 g/L group. Continuous cutting in the upper cutting zone (abrasive velocity ≈ 200 m/s) formed a smooth surface (Ra = 8.5 ± 1.2 μm), oblique shearing in the middle cutting zone (velocity attenuated to 150 m/s) produced a striated structure, and impact fragmentation in the lower cutting zone (velocity < 80 m/s) led to a surge in roughness (Ra = 14.3 ± 2.1 μm). The addition of 0.3 g/L PAM increased the stability of the jet velocity field (37% reduction in turbulence intensity), which reduced the inclination angle of the comb streaks from 18° ± 3° to 12° ± 2°, and reduced the surface waviness by 55%. This phenomenon is highly consistent with the kinetic energy decay model of abrasive grains proposed by Chen et al. [9], which verifies the modulation of the cutting process by the drag-reducing agent.

The formation of comb streaks is directly related to the jet velocity gradient and uneven abrasive distribution. The high kinetic energy abrasive (v = 200 m/s) in the upper cutting zone produces continuous cutting and forms a smooth surface; the jet velocity in the middle cutting zone decays to 150 m/s, and the oblique collision of the abrasive with the marble leads to periodic shear stripping (see Fig. 5 streaks); the velocity in the lower cutting zone further decreases to 80 m/s, and the abrasive is predominantly impact crushed to form craters [21,22]. The addition of polyacrylamide suppressed the abrupt change in velocity gradient by stabilizing the jet velocity field (37% reduction in turbulence intensity), thus reducing the stripe spacing (Fig. 9b).

4.7 Viscoelastic Modulation and Jet Dynamics Mechanisms

The long chain structure and amide group of PAM molecule give the solution unique viscoelastic properties, and its effect on jet dynamics can be analyzed from the following two aspects:

Turbulence inhibition effect: At low concentrations (<0.3 g/L), PAM reduces the velocity gradient in the jet boundary layer through the “wall lubrication” mechanism, which reduces the turbulent frictional resistance by 18% [23]. At a concentration of 0.3 g/L, the dynamic cross-linking of molecular chains forms an elastic network that effectively traps turbulent vortices (>50 μm in size), reducing the turbulent kinetic energy (k) in the core of the jet from 0.05 to 0.035 m2/s2, thus reducing the energy dissipation of the abrasive particles due to turbulence diffusion.

Optimization of abrasive transport: The normal stress difference effect of viscoelastic fluids causes abrasive particles to exhibit a “focusing effect” in the jet, i.e., the concentration of abrasive particles in the edge region is reduced by 22% and the concentration in the core region is increased by 15% [24]. This distribution optimization increases the impact energy per unit area by 19% while reducing the ineffective erosion of the edge abrasive particles on the sidewalls of the incision, thus narrowing the width of the incision (Fig. 10).

Molecular dynamics simulations showed that the amide group of the PAM chain segment formed hydrogen bonds with water molecules (bond length 0.28 nm, bond angle 115°), which led to an increase in the degree of structuring of the solution, as evidenced by an increase in the viscosity from 0.001 Pa s in fresh water to 0.005 Pa s at a shear rate of 100 s−1. This increase in viscosity prolonged the acceleration time of the particles in the jet and led to a decrease in their exit velocity from 280 s−1 to 0.005 Pa s at the same time. This increase in viscosity prolongs the acceleration time of the abrasive particles in the jet and increases their exit velocity from 280 to 310 m/s [25], thus increasing the kinetic energy of the impact. When the concentration exceeds 0.3 g/L, the shear thickening effect due to molecular chain entanglement decreases the acceleration efficiency of the abrasive particles, and the exit velocity decreases by 5%–8%, which confirms the existence of a concentration threshold.

Aiming at the industry problems of poor surface quality and high energy consumption in marble cutting, this study innovatively introduced polyacrylamide (PAM) into the abrasive jet system, and systematically revealed the effects of process parameters and fluid viscoelasticity on cutting quality through a three-factor and five-level mixed orthogonal test (L25 orthogonal table, covering cutting speed 50–300 mm/min, PAM concentration 0–0.5 g/L, nozzle (L25 orthogonal table, covering cutting speed 50–300 mm/min, PAM concentration 0–0.5 g/L, nozzle spacing 4–12 mm), combined with multifactor analysis of variance (ANOVA) and scanning electron microscope (SEM) microscopic morphology observation, the system reveals the coupling mechanism of the process parameters and fluid viscoelasticity on the quality of the cut. The study confirms that PAM can significantly improve energy utilization by regulating the turbulence pulsation and abrasive transport behavior of the jet, which provides a new technological path for high-precision stone cutting. The results of the research are listed below:

(1) The feed rate has a significant modulating effect on the cut quality: when the feed rate is increased, the kerf width decreases exponentially (R2 = 0.94), but the surface roughness gradient in the middle and lower cutting zones increases by 1.8 times. This is due to the shortening of the residence time of the high-speed jet (<20 ms), which leads to a decrease in the abrasive erosion energy density and triggers an increase in the impact fragmentation effect in the lower cutting zone.

(2) The critical concentration of polymer has a significant effect: at a concentration of 0.3 g/L, the PAM molecules reduce the standard deviation of the core velocity of the jet by 32% through the elastic network structure, the width of the kerf is reduced by 18%, and the surface roughness is reduced by 25%. When the concentration exceeds the critical value (>0.3 g/L), the molecular chain entanglement triggers the fluid shear thickening, resulting in the dispersion of the jet energy, and the kerf width increases by 5%–8%, which is closely related to the viscoelastic behavior of the polymer solution.

(3) It is clear from the analysis of polarity and variance that the feed rate is the main controlling factor of cutting quality (58.7%), followed by PAM concentration (23.4%) and nozzle spacing (17.9%). The optimal combination of process parameters was obtained by comprehensive optimization: feed rate of 200 mm/min, PAM concentration of 0.3 g/L, and nozzle spacing of 6 mm, which ensured that the width of the cut seam was 0.867 mm while the surface roughness reached a minimum of 10.220 μm, which was in line with the principle of cost-effectiveness in engineering applications.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (grant number: 52006061), the Key R&D Program of Hunan Province (grant number: 2024AQ2001), Scientific Research Program of Hunan Provincial Department of Education (grant number: 22B0840); Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (grant number: 2023JJ50483), Hunan University of Humanities, Science and Technology Graduate Student Research and Innovation Program (ZSCX2024Y06, ZSCX2024Y01).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design, Dong Hu; data collection, Yunfeng Zhang and Yuan Liu; analysis and interpretation of results, Yunfeng Zhang; draft manuscript preparation, Yunfeng Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yin G, Liu LH. Experimental study on cutting marble by premixed abrasive jet. Sci Technol Info. 2012;(28):128, 130. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Yin ZQ, Rong XM, Ze XB. Production process of diamond frame saw blade for sawing marble. Stone. 2019;8:8–14. (In Chinese). doi:10.14030/j.cnki.scaa.2019.0169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Gong YJ. Abrasive water jet cutting technology research status and its development trend. Chin Hydraul Pneum. 2016;10:1–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

4. Rowe A, Pramanik A, Basak AK, Prakash C, Subramaniam S, Dixit AR, et al. Effects of abrasive waterjet machining on the quality of the surface generated on a carbon fibre reinforced polymer composite. Machines. 2023;11(7):19. doi:10.3390/machines11070749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Y, Liu D, Zhang W, Zhu H, Huang C. Hole characteristics and surface damage formation mechanisms of Cf/SiC composites machined by abrasive waterjet. Ceram Int. 2022;48(4):5488–98. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.11.093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Behjatian A, Esmaeeli A. Transient electrohydrodynamics of a liquid jet: evolution of the flow field. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2014;10(3):299–317. doi:10.3970/fdmp.2014.010.299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Bentarzi F, Mataoui A. Turbulent flow produced by twin slot jets impinging a wall. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2018;14(2):107–20. doi:10.3970/fdmp.2018.06046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fuse K, Vora J, Wakchaure K, Patel VK, Chaudhari R, Saxena KK, et al. Abrasive waterjet machining of titanium alloy using an integrated approach of Taguchi-based passing vehicle search algorithm. Int J Interact Des Manuf. 2025;19(3):2249–63. doi:10.1007/s12008-024-01831-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Chen J, Yuan Y, Gao H, Zhou T. Analytical modeling of effective depth of cut for ductile materials via abrasive waterjet machining. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2023;124(5–6):1813–26. doi:10.1007/s00170-022-10538-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Lei YY, Cai LM, Bing LJ, Tang LB. Microabrasive water jet technology and its application. J Xihua Univ. 2009;28(4):1–6. [Google Scholar]

11. Pei JH, Bai ZW. Influence on cutting quality generated by high polymeric additives abrasive water jet. Mach Tools Hydraul. 2016;44(15):142–6. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

12. Zuo HN. Experimental study on the addition of polymer to abrasive water jet [master’s thesis]. Xiangtan, China: Hunan University of Technology; 2013. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

13. Cetintas S. Polishing performance of muğla white marble with different abrasives. Geoheritage. 2025;17(23):129. doi:10.1007/s12371-025-01064-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Aligholi S, Torabi AR, Khandelwal M. Quantifying the cohesive strength of rock materials by roughness analysis using a domain based multifractal framework. Int J Rock Mech Min Sci. 2023;170:105492. doi:10.1016/j.ijrmms.2023.105492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Yusufi BK, Kapelan Z, Mehta D. Rheology-based wall function approach for wall-bounded turbulent flows of Herschel-Bulkley fluids. Phys Fluids. 2024;36(2):15. doi:10.1063/5.0180663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Agus M, Bortolussi A, Careddu N, Ciccu R, Grosso B, Marras G. Multi-pass abrasive waterjet cutting strategy. In: Proceedings of the 16th International Conference on Water Jetting; 2002 Oct 16–18; Aix-en-Provence, France. [Google Scholar]

17. Hou JY, Kang X, Xu K, Gong YJ, Ning DY, Zhang ZM. Research on the cutting performance of abrasive water jet based on the proposed horizontal orthogonal experimental method. Mach Tools Hydraul. 2018;46(3):95–8. [Google Scholar]

18. Cai SP, Bai L, Hu D. Effect of drag reducer on the cutting quality of post mixed abrasive jet. J Hunan Univ Technol. 2014;28(2):12–5. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

19. Kulekci MK. Processes and apparatus developments in industrial waterjet applications. Int J Mach Tools Manuf. 2002;42(12):1297–306. doi:10.1016/S0890-6955(02)00069-X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Li LP. Research on the technology of abrasive jet cutting underwater casing [Ph.D. thesis]. Qingdao, China: China University of Petroleum (East China); 2010. [Google Scholar]

21. Selvan M, Raju N, Sachidananda HK. Effects of process parameters on surface roughness in abrasive waterjet cutting of aluminium. Front Mech Eng. 2012;7(4):439–44. doi:10.1007/s11465-012-0337-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Azmir MA, Ahsan AK. Investigation on glass/epoxy composite surfaces machined by abrasive water jet machining. J Mater Process Technol. 2008;198(1–3):122–8. doi:10.1016/j.jmatprotec.2007.07.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Jiang YY, Guan XL, Jiang N. TRPIV experimental study of turbulence damping mechanism of polymer solution wall. Exp Mech. 2013;28(4):9. doi:10.7520/1001-4888-12-175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ni C, Jiang D. Three-dimensional numerical simulation of particle focusing and separation in viscoelastic fluids. Micromachines. 2020;11(10):908. doi:10.3390/mi11100908. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Sharif F, Asce A. Dynamics of sand—water coaxial jets in stagnant water. J Eng Mech. 2024;150(8):18. doi:10.1061/JENMDT.EMENG-7584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools