Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Role of Inertial Force and Dynamic Contact Angle on the Incipient Motion of Droplets in Shearing Gas Flow

1 Hangzhou International Innovation Institute, Beihang University, Hangzhou, 311115, China

2 Tianmushan Laboratory, Yuhang District, Hangzhou, 311115, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaoyan Ma. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Materials and Energy an Updated Image for 2023)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(7), 1601-1610. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.067414

Received 02 May 2025; Accepted 30 June 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study experimentally investigates the oscillatory dynamics of wind-driven droplets using high-speed imaging to capture droplet profiles within the symmetry plane and to characterize their natural oscillation frequencies. Results reveal that the eigenfrequencies vary spatially due to distinct oscillation modes occurring at different droplet locations. Notably, the fundamental eigenfrequency decreases with reducing droplet volume, while droplet viscosity exerts minimal influence on this frequency. Prior to the onset of motion, the dynamic contact angle consistently remains between the advancing and receding angles. The inertial forces generated by droplet oscillation are found to be significantly greater than the adhesion forces, indicating that classical static models are inadequate for capturing inertial contributions to droplet motion. These findings offer new insights into the role of oscillatory behavior in influencing the dynamics of droplet motion, and contribute to a more detailed understanding of wind-driven droplet transport phenomena.Keywords

Supercooled water droplets on aircraft wings are a critical factor in icing phenomena, posing significant hazards to aviation safety. During icing, supercooled droplets impact and freeze on surfaces, while unfrozen droplets migrate as films, rivulets, or discrete droplets—particularly on superhydrophobic surfaces [1]. The movement of these droplets represents a fundamental fluid mechanics challenge, with implications for industrial applications such as heat exchanger efficiency [2] and aircraft anti-/de-deicing [3]. Under high-Reynolds-number (high-Re) airflow, droplet dynamics become highly complex due to the coupling between droplet oscillation and unsteady wake vortices (Re > 120) [4].

Investigating high-Re droplet dynamics remains challenging, with only limited studies addressing the problem. To simplify analysis, Dussan [5] applied lubrication theory, finding that critical wind speed scales linearly with surface tension and inversely with viscosity. However, this approach is restricted to droplets with small contact angles and low hysteresis, resembling liquid films rather than true droplets. Durbin [6] extended this model by incorporating flow separation effects, though still under similar limitations. Ding and Spelt [7] numerically studied shear-driven droplets with 90° contact angles but were constrained to Re < 250 due to flow unsteadiness. Zhang et al. [8] experimentally observed that droplets exhibit rhythmic oscillations before incipient motion, generating inertial forces comparable to adhesion forces, suggesting a strong influence on mobility [9], suggesting a strong influence on mobility.

The oscillation dynamics of wind-driven droplets have been partially characterized. Noblin et al. [10] modeled droplet oscillation as capillary standing waves, predicting frequency proportional to the inverse square root of droplet volume (∝V−1/2), (where V is droplet volume), later confirmed by Milne et al. [11]. Sharp et al. [12] validated Noblin’s theory across wettability gradients, while Chiba et al. [13] developed a Laplace-equation-based model to describe oscillation modes. Milne et al. [11] further identified multimodal oscillations, where the zeroth mode (axisymmetric) and first mode (non-axisymmetric) dominate in the absence of gravity. However, these models fail to predict viscosity-dependent damping effects on amplitude. However, these models fail to predict viscosity-dependent damping effects on amplitude [14], limiting their applicability to mobility analysis.

Despite its presumed importance, droplet oscillation has rarely been directly linked to mobility. Milne and Amirfazli [15] derived a scaling law relating critical wind speed to droplet geometry (arc length × projected area), while Fan et al. [16] found that viscosity primarily affects mobility via contact angle modification—contrasting with Stokes flow, where critical speed scales linearly with viscosity. Roisman et al. [17] extended static analysis to subfreezing conditions, and Barwari et al. [18] and Chahine et al. [19] correlated critical Re with Laplace and Weber numbers across viscosity ranges. However, these approaches neglect transient oscillation effects.

Oscillation also modifies near-droplet flow fields, potentially influencing mobility. Burgman et al. [14] observed synchronization between vortex shedding and droplet oscillation, suggesting coherent interactions. While some attribute oscillation to vortex forcing [16], its self-excited nature remains unconfirmed. Zhang et al. [3] used particle image velocimetry (PIV) to show that oscillation negligibly affects aerodynamic drag but enhances flow reattachment—a phenomenon lacking clear physical explanation. The unresolved interplay between oscillation, vortex dynamics, and mobility underscores the need for further investigation.

Despite investigations in the fields of droplet mobility and oscillation, whether droplet oscillation precedes the shedding of wind-driven droplets is not completely understood. Several studies hypothesized that substantial droplet oscillation precedes the depinning of droplet contact line by adding inertial force to the droplet [9]. However, the hypothesis lacks experimental support. Previous studies have also rarely investigated the dynamic contact angle, which is crucial for droplet adhesion. The influences of oscillation on droplet mobility need to be provided insights to bridge the knowledge gap between droplet oscillation and mobility. In this way, the present study experimentally explores the effect of wind speed, droplet volume and viscosity on the oscillation characteristics of wind-driven droplets. The experimental setup will be described first. After analyzing the frequencies of droplet oscillation, the experimental results will be presented. Finally, the results will be used to demonstrate the underlying physics pertinent to the influences of droplet oscillation on droplet mobility.

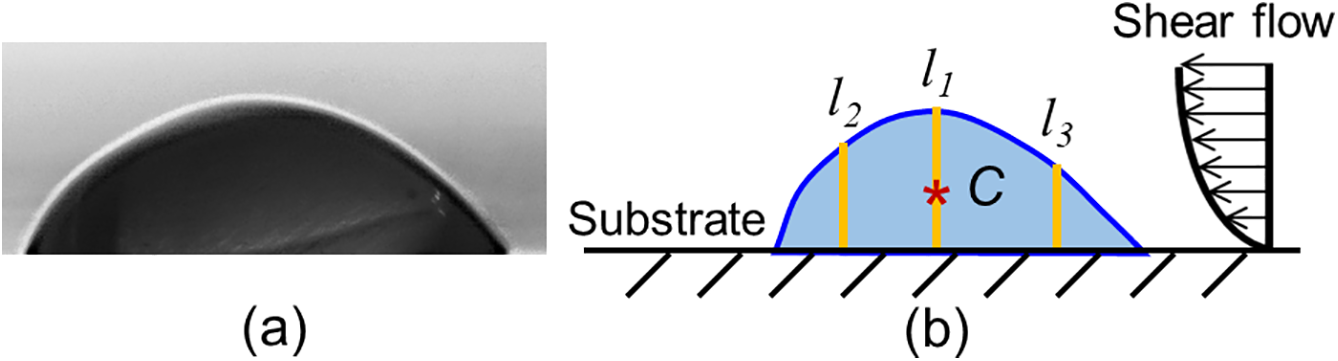

2.1 Measurement of Droplet Height and Centroid Position

Experiments were performed in a wind tunnel, with a test section of 0.60 m (L, Length in the vertical direction) × 0.15 m (W, Width in the spanwise direction) × 0.15 m (H, Height in the vertical direction). The turbulence intensity in the test section was below 1%, as measured by a time-resolved particle image velocimetry (TR-PIV) system. A polymethyl methacrylate (PMMA) plate of dimensions 0.40 m (L) × 0.10 m (W) × 0.01 m (H), was mounted on the substrate on the test section to generate high-quality boundary layer flows. Droplets were placed on the 100 mm from the leading edge at the center of the plate to match the experimental conditions in [14]. Deionized water was used to generate 20 µL droplets by a micropipette, which had a precision of 0.1 μL. The droplet profile was recorded by a high-resolution camera (2560 × 1920 pixels, the droplet image see Fig. 1a) to study the oscillation characteristics of wind-driven droplets. The measurement frequency was set at 1000 Hz, which is at least 10 times greater than the oscillation frequency measured by Zhang et al. [8]. A high measurement frequency allows for capturing more detailed oscillation characteristics, such as oscillation frequency, mode and amplitude.

Figure 1: (a) An example of droplet image; (b) Schematic diagrams of the experimental setup used to measure droplet oscillation at different locations (l1, l2, l3 and mass center, C)

Due to different oscillation modes, the characteristics of droplet oscillation may vary with changes in position [11]. Therefore, the height variation at the front (l1 in Fig. 1b), middle (l2) and rear (l3) of wind-driven droplets, as well as centroid displacement (C in Fig. 1b) were measured following the method of Zhang et al. [8]. After subtracting the background image, images were binarized to obtain uniform black and white regions. The white pixels in the binarized images were determined as the droplet to calculate the centroid displacement (ξ) and droplet height.

Droplet centroid acceleration can be determined from the variation of centroid position over time. The centroid acceleration in the x direction (along the wind direction) is given by

2.2 Measurement of Droplet Viscosities

Water-glycerin mixtures were used in the present study due to their similar surface tension and significant difference in viscosity. The similar surface tension results in only a slight difference in droplet shape. The viscosity of water-glycerin mixtures was measured with a precise viscometer (DVNext, BrookField, Middleboro, MA, USA). The static contact angle, advancing contact angle and receding contact angle of the droplets (see Table 1) were characterized by a droplet shape analyzer (DSA25, Kruss, Hamburg, Germany) with a measurement uncertainty of 0.5°. The measurements were repeated 5 times to reduce the uncertainty.

2.3 Measurement of Dynamic Contact Angles

The primary parameters of interest in the present study include the dynamic contact angles at the front edge (θfront) and the rear edge (θrear), centroid displacement, oscillation-induced inertial force and adhesion force. The measurement accuracy was established by measuring these parameters of a sessile droplet without wind, since the results were a priori. The measurement of θfront and θrear follows the method of Bateni et al. [20], using a third-order polynomial with 150 pixels to fit the curve. θfront and θrear could be accurately measured with an uncertainty within 0.5°.

The critical wind speed (U∞), beyond which either the front edge or the rear edge of droplets begins to move on the plate, was determined using a high-resolution camera. The verge of shedding was defined as the point where droplets have no displacement at either the front edge or the rear edge.

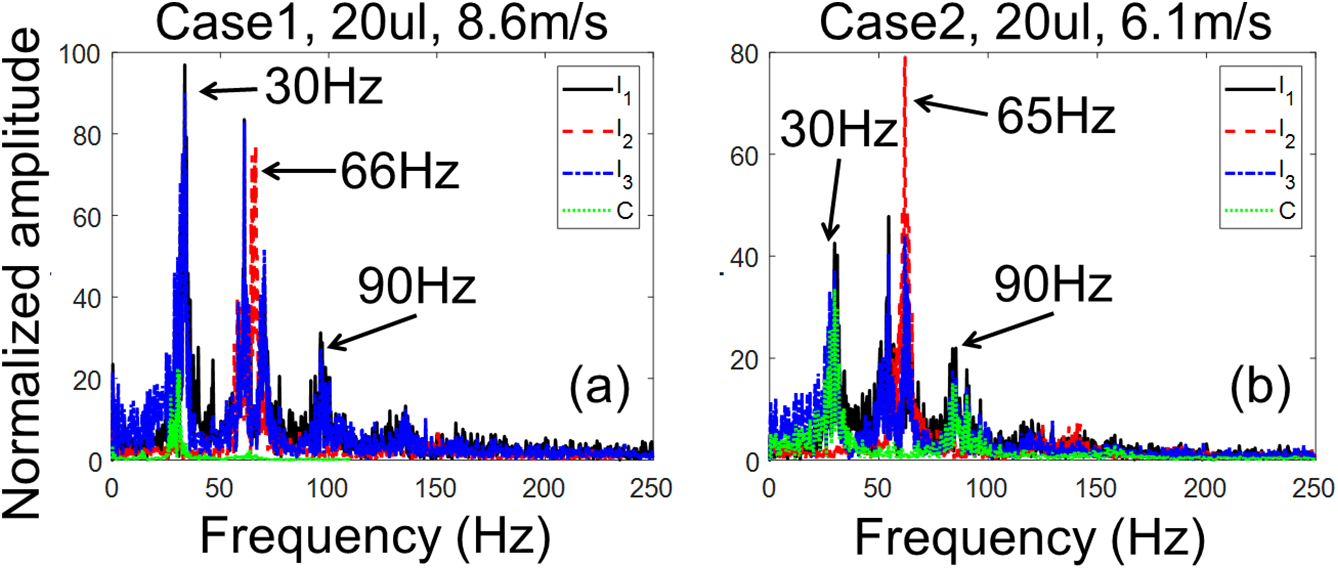

Experimental cases and physical conditions were summarized in Table 1. The selection of experimental conditions was designed to effectively elucidate the underlying physics by which viscosity, wind speed, and volume influence droplet oscillation dynamics.

3.1 Droplet Oscillation Frequencies

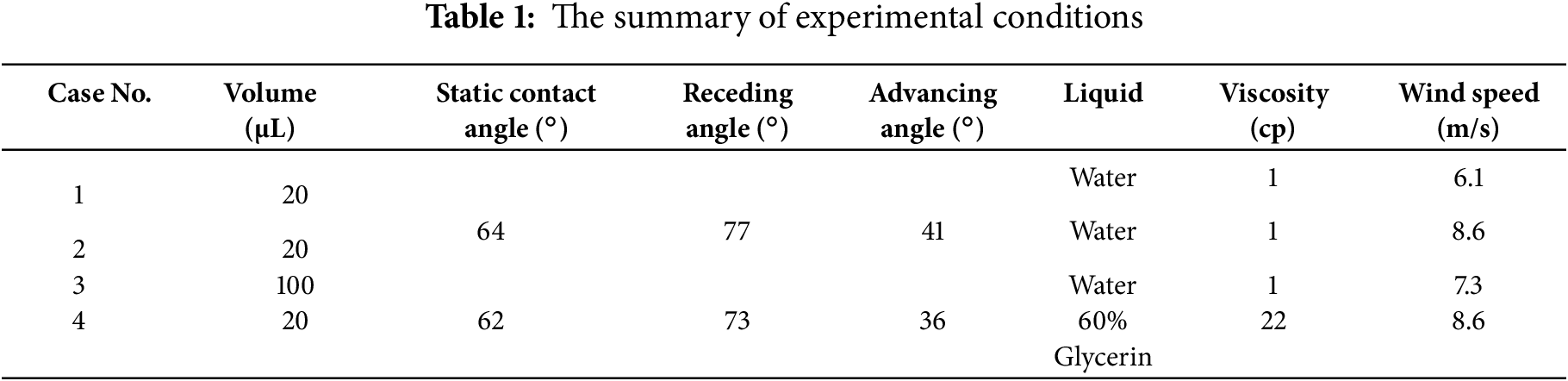

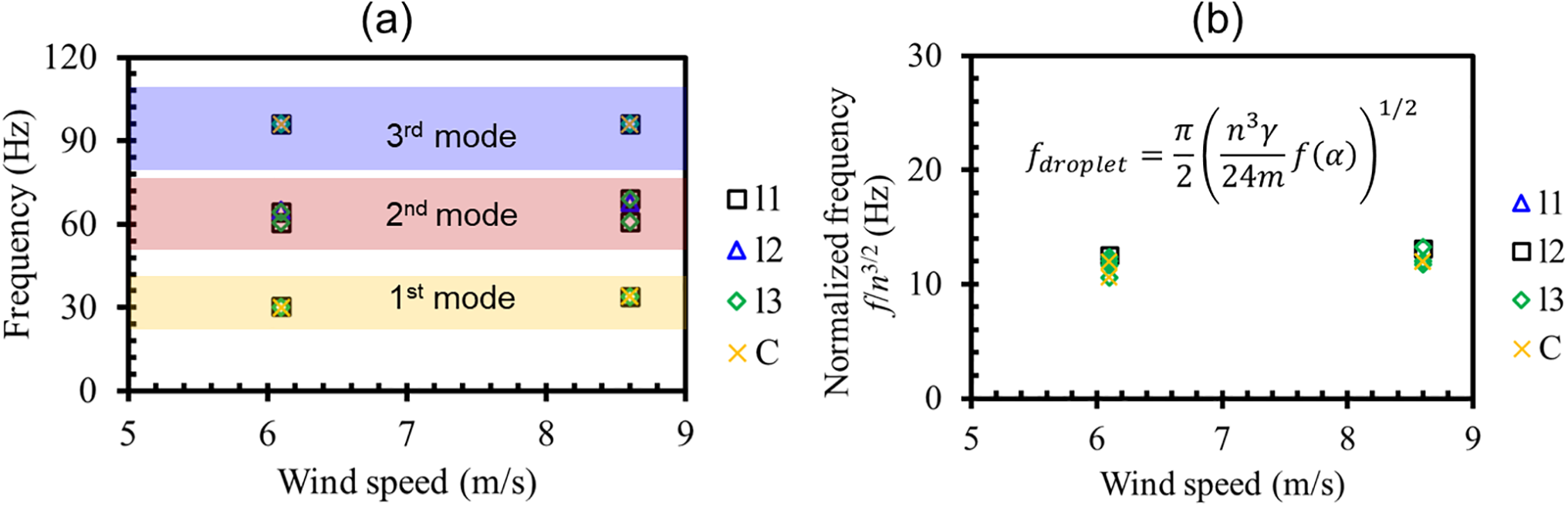

To further elucidate the characteristics of droplet oscillation, the time signal at l1–l3 and centroid is analyzed by Fast Fourier Transformation (FFT). Fig. 2a shows the frequency spectra of velocity fluctuation under different wind speeds. The amplitude in Fig. 2a was normalized by the square root of the number of data points. Droplet oscillation exhibits multiple frequencies, with the oscillation frequency varying at different locations (i.e., l1, l2, l3 and centroid). Fig. 2a,b shows the frequency spectra of wind-driven droplets at various wind speeds and locations. Fig. 2a,b illustrates that the wind speed has a negligible effect on the oscillation frequencies, which was also observed by Burgmann et al. [14]. The primary and secondary peaks in the frequency spectra are summarized in Fig. 2. It was found that at l2 (near droplet apex), the primary frequency (66 ± 1 Hz) of droplet oscillation matches the vortex shedding frequency. In contrast, at l1 and l3, the primary and secondary frequencies (32 ± 2 and 64 ± 4 Hz) differ from those at l2. The frequency spectrum of the droplet centroid agrees well with that at l1 and l3. Zhang et al. [8] also observed this phenomenon, but the underlying physics remains unclear.

Figure 2: Droplet oscillation frequency of droplets under different wind speeds: a 20 μL water droplet in airflows of (a) 8.6 m/s and (b) 6.1 m/s

The present study hypothesizes that the variation in oscillation frequency at different locations results from different oscillation modes. Droplet oscillation is multimodal. Typical oscillation modes include the first axisymmetric mode, the first non-axisymmetric mode and another non-axisymmetric mode observed in the oscillation of wind-driven droplets [11]. Sharp et al. [12] stated that droplet oscillation can be regarded as the propagation of standing waves along the droplet surface with different wavelengths. Since the contact line is pinned, the arc length of droplets should be an integer multiple of half the wavelength, i.e.,

Figure 3: (a) The oscillation frequency and (b) the normalized frequency of cases 1–4 (droplets on the PMMA surface with wind speeds from 4.7 to 8.6 m/s)

Eq. (2) shows that the oscillation frequency is proportional to n3/2, so the frequencies in Fig. 3a are normalized by n3/2 shown in Fig. 3b. The normalized frequencies cluster around 13 Hz with a standard deviation of 1.5 Hz, demonstrating the good accuracy of the scaling law of

According to the finding of Burgmann et al. [14], the frequency of vortex shedding matches closely with the primary frequency at l2, indicating the coherence between flow and droplet oscillation. The corresponding Strouhal number (St) and Re were calculated with the droplet diameter and the wind speed. St and Re vary from 0.046 to 0.084 and 2072 to 2922, in the cases 1–2, respectively. Comparing these results with previous studies poses challenges due to the absence of any known research conducted within the same Re and St range and under comparable conditions [14]. However, it is noteworthy that St of the present study falls within a range where aeroelastic effects, such as galloping, might occur: St = 0.05 [21]. By integrating the results of St, it was found that droplet oscillation could be self-excited arising from the coherence between droplets and airflows under the influence of the aeroelastic effect. This new insight into droplet-flow coherence may help in understanding the incipient motion of wind-driven droplets.

Fig. 4 shows the flow characteristics in the wake of wind-driven droplets with different volumes and viscosities. Eq. (2) shows that as the increase of droplet mass, the oscillation frequency of wind-driven droplets is reduced, resulting in a reduction of the vortex shedding frequency, which is validated by the experimental results shown in Fig. 4a. The oscillation frequency is proportional to the reciprocal of the square root of drop volume (

Figure 4: Droplet oscillation frequency of droplets under different conditions: (a) a 100 μL water droplet in an airflow of 7.3 m/s; (b) a 20 μL viscous droplet in an airflow of 8.6 m/s

3.2 Influence of Droplet Oscillation on Inertial Force

In previous studies, the balance between time-averaged adhesion force and time-averaged aerodynamic drag serves as the criterion for assessing droplet mobility. However, this criterion is not comprehensive, as both time-averaged adhesion force and time-averaged aerodynamic drag are complex, and the effects of droplet oscillation have not yet been considered. Mortazavi et al. [9] added the peak of inertial force into the force balance of wind-driven sessile droplets, which introduces the impact of droplet oscillation on droplet mobility. However, this approach is incomplete, as it conflates the static analysis of time-averaged aerodynamic drag and time-averaged adhesion force with the dynamic analysis of peak inertial force.

Fig. 5 shows that time-averaged inertial force is almost zero, so it should not be considered as analyzing the time-averaged force balance over wind-driven droplets, which is counterintuitive. Furthermore, peak inertial force could be significantly greater than adhesion force, especially for low-viscosity droplets at the verge of shedding (see Fig. 5a,b), which violates the principle of force balance. Therefore, wind-driven droplets should be analyzed within a dynamic system rather than as a system reaching the equilibrium.

Figure 5: Inertial force and adhesion force evolutions of droplets with different experimental conditions: (a) a 20 μL water droplet under the wind speed of 8.6 m/s; (b) a 20 μL water droplet under the wind speed of 6.1 m/s; (c) a 100 μL water droplet under the wind speed of 7.3 m/s; (d) a 20 μL droplet with a viscosity of 22 cp under the wind speed of 8.6 m/s

Fig. 5c shows that inertial force of larger droplets is significantly lower than that of smaller droplets since larger droplets require a lower wind speed to initiate motion so the oscillation is slower. Although oscillation is slower for larger droplets, their deformation leads to greater fluctuations in adhesion force, which may precede droplet motion since intense fluctuations in adhesion force could cause the adhesion force to exceed the maximum value that a sessile droplet can withstand. Due to the larger damping force, droplets with a higher viscosity exhibit a smaller oscillation amplitude and experience lower inertial force and less fluctuations in adhesion force.

Fig. 5d shows that for low-viscosity droplet, the inertial force could be significantly higher than the adhesion force, suggesting that the inertial force may precede droplet motion. This hypothesis appears to be valid since the critical wind speed of water droplets (i.e., 8.6 m/s) is indeed lower than that of glycerin droplets (i.e., 11.2 m/s), and the surface tension are highly similar. However, this statement should be approached with caution since aerodynamic drag and damping force in the dynamic system remain unclear.

3.3 Instantaneous Dynamic Contact Angles

Analyzing droplet mobility based on force balance is challenging because establishing accurate models for the forces involved is difficult. Determining whether the dynamic contact angle at the rear part (θrear, see the inset in Fig. 6b) of an oscillating droplet exceeds the advancing contact angle is an important and direct criterion for assessing droplet mobility [9]. Fig. 6 shows that before incipient motion, θrear indeed does not reach the advancing contact angle. Fig. 6a,b shows that as approaching the critical wind speed beyond which droplets start to move, θrear consistently less than the advancing contact angle. Fig. 6c,d shows that wind-driven droplets with different volumes and viscosities also have the dynamic contact angles smaller than the advancing contact angle, which partially corroborates this hypothesis for wind-driven droplets on the PMMA surface. It was found that as wind speed increases, the fluctuation of θrear becomes more significant. This facilitates the likelihood that θrear exceeds the advancing contact angle and promotes droplet motion. In Fig. 6a,c, a larger droplet has a larger fluctuation in θrear, leading to a more intensified fluctuation of adhesion force, which facilitates droplet incipient motion. Due to high damping force, θrear of high-viscosity droplets has little fluctuations.

Figure 6: The dynamic contact angles (see the inset in (b)) at the rear and front part of droplets with different experimental conditions: (a) a 20 μL water droplet under the wind speed of 8.6 m/s; (b) a 20 μL water droplet under the wind speed of 6.1 m/s; (c) a 100 μL water droplet under the wind speed of 7.3 m/s; (d) a 20 μL droplet with an viscosity of 22 cp under the wind speed of 8.6 m/s. The red dotted line indicates the advancing contact angle. The black dash-dotted line indicates the receding contact angle

However, predicting droplet mobility cannot solely rely on the dynamic contact angle. Although the dynamic contact angle is approaching the advancing contact angle before incipient motion occurs, it may not reach the advancing contact angle when incipient motion occurs due to the complex internal flow and pressure field. Therefore, formulating a comprehensive criterion that integrates the forces involved and the dynamic contact angle presents an effective approach for evaluating droplet mobility.

A series of experiments was conducted to investigate the oscillation dynamics of wind-driven droplets by measuring the characteristics of droplet oscillation using the high-speed imaging technique. The effects of droplet volume, viscosity and wind speed on the characteristics of droplet oscillation were explored.

The primary eigenfrequency keeps constant regardless of wind speed, and the Strouhal number falls in the range of galloping. These phenomena indicate that the oscillation of wind-driven droplets could be self-excited rather than the vortex-induced hypothesized in previous studies. Due to the existence of multiple vibrational modes, different positions on the droplet exhibit different oscillation frequencies. The primary eigenfrequency of droplet oscillation shows an inverse dependence on volume while demonstrating negligible sensitivity to viscous effects. Prior to the incipient motion, the dynamic contact angle remains bounded between the advancing and receding angles, suggesting that exceeding this angular range may initiate droplet motion. The inertial force significantly exceeds the adhesion force, rendering traditional static analysis methods inadequate for studying droplet oscillations. This necessitates the establishment of dynamic models to thoroughly investigate the impact of droplet oscillations on motion characteristics.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12402291); the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (No. 3244043); the Research Start-up Funds of Hangzhou International Innovation Institute of Beihang University (Grant Nos. 2024KQ008, 2024KQ062).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Zichen Zhang; methodology, Zichen Zhang; software, Zichen Zhang; validation, Zichen Zhang and Aoyu Zhang; formal analysis, Zichen Zhang and Xiaoyan Ma; investigation, Zichen Zhang, Aoyu Zhang and Tongtong Qi; resources, Xiaoyan Ma; data curation, Tongtong Qi; writing—original draft preparation, Zichen Zhang and Xiaoyan Ma; writing—review and editing, Xiaoyan Ma; supervision, Xiaoyan Ma; project administration, Xiaoyan Ma; funding acquisition, Xiaoyan Ma and Zichen Zhang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Xiaoyan Ma, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Waldman RM, Hu H. High-speed imaging to quantify transient ice accretion process over an airfoil. J Aircr. 2016;53(2):369–77. doi:10.2514/1.C033367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Shakeri Bonab M, Kempers R, Amirfazli A. Determining transient heat transfer coefficient for dropwise condensation in the presence of an air flow. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2021;173(1):121278. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2021.121278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang Z, Emami RY, Amirfazli A. Effects of surface wettability on the aerodynamics of wind-driven droplets at the verge of shedding. Phys Fluids. 2023;35(1):17129. doi:10.1063/5.0128516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hooshanginejad A, Lee S. Dynamics of a partially wetting droplet under wind and gravity. Phys Rev Fluids. 2022;7(3):033601. doi:10.1103/PhysRevFluids.7.033601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Dussan EB. On the ability of drops to stick to surfaces of solids. Part 3: the influences of the motion of the surrounding fluid on dislodging drops. J Fluid Mech. 1987;174:381–97. doi:10.1017/S002211208700017X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Durbin PA. On the wind force needed to dislodge a drop adhered to a surface. J Fluid Mech. 1988;196:205–22. doi:10.1017/S0022112088002678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ding H, Spelt PDM. Onset of motion of a three-dimensional droplet on a wall in shear flow at moderate Reynolds numbers. J Fluid Mech. 2008;599:341–62. doi:10.1017/S0022112008000190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang J, Sato T, Ooyama T, Koumura K, Ito T, Tsuji Y. Observation of water droplet motion in a shear flow. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2023;141(3):110775. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2022.110775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Mortazavi M, Jung SY. Role of droplet dynamics on contact line depinning in shearing gas flow. Langmuir. 2023;39(30):10301–11. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.3c00065. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Noblin X, Buguin A, Brochard-Wyart F. Vibrations of sessile drops. Eur Phys J Spec Top. 2009;166(1):7–10. doi:10.1140/epjst/e2009-00869-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Milne AJB, Defez B, Cabrerizo-Vílchez M, Amirfazli A. Understanding (sessile/constrained) bubble and drop oscillations. Adv Colloid Interface Sci. 2014;203(8):22–36. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2013.11.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Sharp JS, Farmer DJ, Kelly J. Contact angle dependence of the resonant frequency of sessile water droplets. Langmuir. 2011;27(15):9367–71. doi:10.1021/la201984y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Chiba M, Michiue S, Katayama I. Free vibration of a spherical liquid drop attached to a conical base in zero gravity. J Sound Vib. 2012;331(8):1908–25. doi:10.1016/j.jsv.2011.12.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Burgmann S, Dues M, Barwari B, Steinbock J, Büttner L, Czarske J, et al. Flow measurements in the wake of an adhering and oscillating droplet using laser-doppler velocity profile sensor. Exp Fluids. 2021;62(3):1–16. doi:10.1007/s00348-021-03148-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Milne AJB, Amirfazli A. Drop shedding by shear flow for hydrophilic to superhydrophobic surfaces. Langmuir. 2009;25(24):14155–64. doi:10.1021/la901737y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Fan J, Wilson MCT, Kapur N. Displacement of liquid droplets on a surface by a shearing air flow. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2011;356(1):286–92. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.12.087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Roisman IV, Criscione A, Tropea C, Mandal DK, Amirfazli A. Dislodging a sessile drop by a high-Reynolds-number shear flow at subfreezing temperatures. Phys Rev E. 2015;92(2):23007. doi:10.1103/PhysRevE.92.023007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Barwari B, Burgmann S, Bechtold A, Rohde M, Janoske U. Experimental study of the onset of downstream motion of adhering droplets in turbulent shear flows. Exp Therm Fluid Sci. 2019;109(3):109843. doi:10.1016/j.expthermflusci.2019.109843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Chahine A, Sebilleau J, Mathis R, Legendre D. Sliding droplets in a laminar or turbulent boundary layer. Phys Rev Fluids. 2022;7(11):113605. doi:10.1103/PhysRevFluids.7.113605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Bateni A, Susnar SS, Amirfazli A, Neumann AW. A high-accuracy polynomial fitting approach to determine contact angles. Colloids Surf A Physicochem Eng Asp. 2003;219(1–3):215–31. doi:10.1016/S0927-7757(03)00053-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Poirel D, Harris Y, Benaissa A. Self-sustained aeroelastic oscillations of a NACA0012 airfoil at low-to-moderate Reynolds numbers. J Fluids Struct. 2008;24(5):700–19. doi:10.1016/j.jfluidstructs.2007.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools