Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Lattice Boltzmann-Based Numerical Simulation of Laser Welding in Solar Panel Busbars

1 School of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Quzhou College of Technology, Quzhou, 324000, China

2 School of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Huainan Normal University, Huainan, 232038, China

* Corresponding Author: Mingliang Zheng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Model-Based Approaches in Fluid Mechanics: From Theory to industrial Applications)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2025, 21(8), 1955-1968. https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2025.069254

Received 18 June 2025; Accepted 30 July 2025; Issue published 12 September 2025

Abstract

To address the limitations of traditional finite element methods, particularly the continuum assumption and difficulties in tracking the solid-liquid interface, this study introduces a lattice Boltzmann-based mathematical and physical model to simulate flow and heat transfer in the laser welding molten pool of tin-coated copper used in solar panel busbars (a thin strip or wire of conductive metal embedded on the surface of a solar cell to collect and conduct the electricity generated by the photovoltaic cell). The model incorporates key external forces, including surface tension, solid-liquid interface tension, and recoil pressure. A moving and rotating Gaussian-body heat source is adopted, with temperature treated as an implicit function of enthalpy. Coupled iterative schemes for the temperature and velocity fields are constructed using a dual-distribution function approach with a D3Q15 lattice structure. The model is implemented in Python, utilizing libraries such as NumPy, SciPy, Mayavi, and Matplotlib for computation and visualization. Simulation results reveal that the heat transfer mechanism in the molten pool transitions from pure conduction to conduction-convection due to surface tension effects, leading to the formation of multiple counter-rotating vortex structures. The peak temperature at the pool center reaches 3200 K, with maximum melt depth and width measured at 0.5 and 1.2 mm, respectively. Over time, both penetration depth and melt width increase, though the width exhibits a more pronounced growth. Comparison with experimental thermal cycling data from laser weld joints shows strong agreement, with a maximum error of less than 1%, validating the accuracy of the proposed method.Keywords

Busbar welding is a critical process in the production of solar panel modules, as its performance directly influences the operational efficiency of the panels [1]. Laser welding, in particular, offers several advantages including non-contact welding, high energy density, significant weld depth and width, rapid welding speed, excellent repeatability, minimal workpiece deformation, and a reduced heat-affected zone [2]. Consequently, the application of laser welding for busbars presents promising prospects for the photovoltaic power generation industry worldwide. In this process, the interconnection ribbon is welded to the busbar connecting two adjacent battery strings, functioning as a parallel battery string. The fluid dynamics of the weld pool are intricately linked to the shape of the weld pool, dendritic growth, and solidification, which can significantly influence the microstructure and properties of the welded joint. Thus, understanding the dynamic behavior of the laser welding pool in solar panel busbar applications holds substantial value for numerical simulations and engineering experiments.

Currently, traditional computational fluid dynamics (CFD) methods based on continuous fluid assumptions are employed in the simulation research of laser welding. However, these methods struggle to adequately explain the microscopic characteristics of physical systems [3]. For instance, reference [4] utilized commercial software Fluent to simulate the dynamic behavior of the molten pool in laser deep penetration welding of stainless steel, while reference [5] employed ABAQUS for numerical simulations of laser welding between dissimilar magnesium alloys and steel. Zhang [6] conducted a computational modeling and experimental investigation of laser keyhole welding between duplex stainless steel 2205 and low carbon steel (A516). Additionally, Zhang [7] examined the influence of laser beam deviation on the temperature field and melt flow during the laser welding of two distinct metals, brass and 308 stainless steel (S.S 308), through both numerical and experimental approaches. In the aforementioned methods, accurately simulating potential defects during the welding process, such as porosity and cracks, poses a challenge, particularly when considering the nonlinear behavior of materials and the complexities of multi-phase flow interface tracking and boundary condition processing. Notably, in recent years, the lattice Boltzmann method (LBM) [8,9] has emerged as a novel mesoscopic approach in computational fluid dynamics. This method is characterized by fewer assumptions compared to microscopic methods and offers advantages over macroscopic methods that overlook molecular motion details. LBM has achieved significant advancements in both fundamental theory and practical applications, demonstrating considerable advantages and potential in addressing complex flow problems involving multi-scale and multi-physics processes, such as its application in interface dynamics and complex boundaries [10,11]. Furthermore, LBM programming is simplified and conducive to parallelization [12,13], resulting in enhanced computational efficiency. For example, reference [14] presents thread-safe, highly-optimized lattice Boltzmann implementations, specifically aimed at exploiting the high memory bandwidth of GPU-based architectures, and in reference [15], the melting and resolidification of ultrashort laser interaction with thin gold film is investigated in terms of a meso-scale method. The lattice Boltzmann method (LBM), including the electron-phonon collision term is established. These researches provide a certain reference value for the work of this paper.

Currently, there is a limited body of literature addressing the application of the Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) in the context of laser welding. Notably, research specifically focusing on the laser welding of solar panel busbars is virtually absent. This paper employs the LBM to simulate the dynamic evolution process within the three-dimensional laser welding pool of solar panel busbars. The program code is implemented using logical arrays in Python, and the simulation results are subsequently analyzed. Although this study primarily targets the simulation of busbar laser welding and aims to provide insights for process improvement, it is noteworthy that by altering the thermophysical properties of materials and the parameters of the equivalent heat source, the approach can be adapted to other advanced welding processes, such as plasma arc welding and friction stir welding.

2 Mathematical Model of Solar Panel Busbar Laser Welding

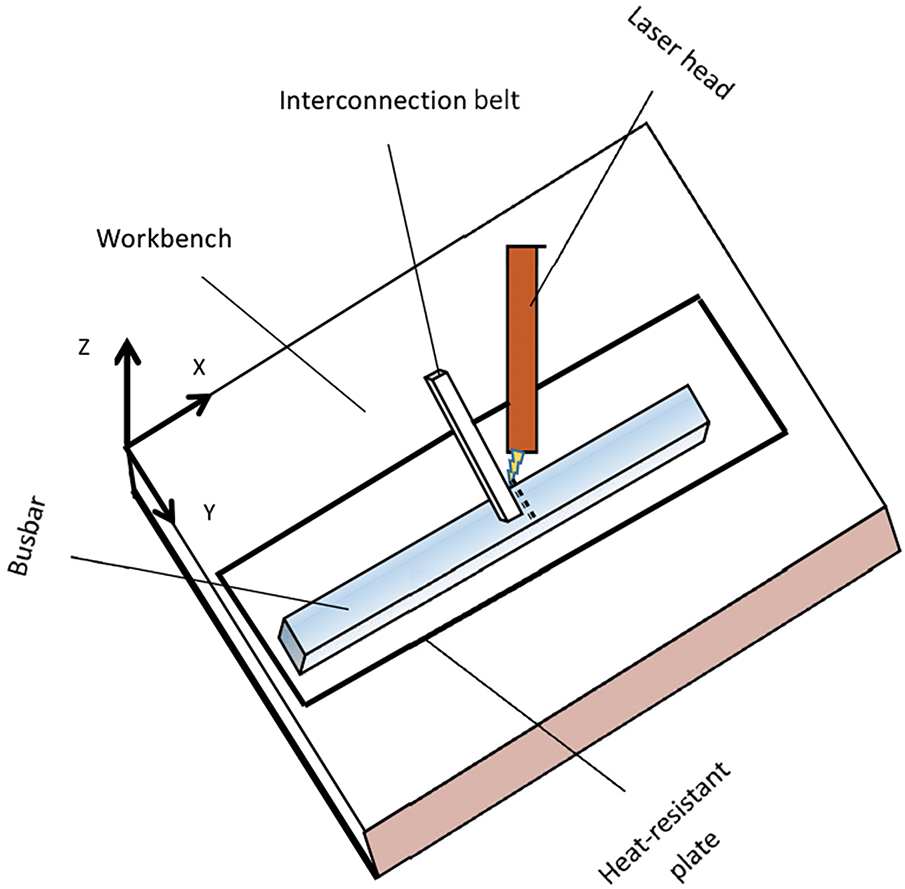

The laser welding process for solar panel busbars employs a laser, workbench, phenolic resin heat-resistant plate, flux for oxide film removal, busbars, and interconnection belts. Both the busbars and the interconnection belts are manufactured from tin-coated copper alloy. The interconnection belts serve to connect battery strings in series, while the busbars are used to weld the interconnection belts, thereby achieving a parallel connection among the battery strings. Fig. 1 illustrates the welding device employed in this process.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of laser welding of busbar

Since the laser welding power density of solar-panel busbars exceeds 1 × 106 W/cm2, the process is categorized as laser penetration welding [16]. This welding process is inherently complex, involving not only the melting and solidification of materials but also the influence of metal vapor recoil pressure on the weld pool, which can lead to the formation of micropores. To simplify the model, several fundamental assumptions are adopted [17]: (1) the liquid metal in the weld pool is assumed to be laminar and incompressible; (2) the material is considered isotropic, with thermal conductivity and dynamic viscosity represented as single-valued functions of temperature, while other thermophysical parameters, such as density and specific heat capacity, are assumed constant; and (3) chemical reactions between the melt and the gas are neglected.

According to fluid Navier-Stokes equations, the continuity (mass) equation, momentum equation and energy equation of laser welding of busbar are:

here,

The external forces

here,

The initial condition

here,

3 Lattice Boltzmann Algorithm Construction

The Lattice Boltzmann Method (LBM) operates without requiring the fluid continuity assumption. This approach involves discretizing the space, time, and velocity components of a fluid system. In this framework, all fluid particles migrate and collide on a discrete lattice (discrete space) according to evolution mechanisms that adhere to specific physical laws. The macroscopic fluid properties are ultimately obtained through statistical averaging.

For modeling the velocity and temperature fields in laser welding of busbars using LBM, the double distribution function model can be employed. The velocity distribution is calculated using an isothermal lattice Boltzmann scheme incorporating external force [18,19], while the temperature distribution is determined through a lattice Boltzmann scheme based on enthalpy change [20,21]. The corresponding LBM evolution equations are as follows:

here, subscript

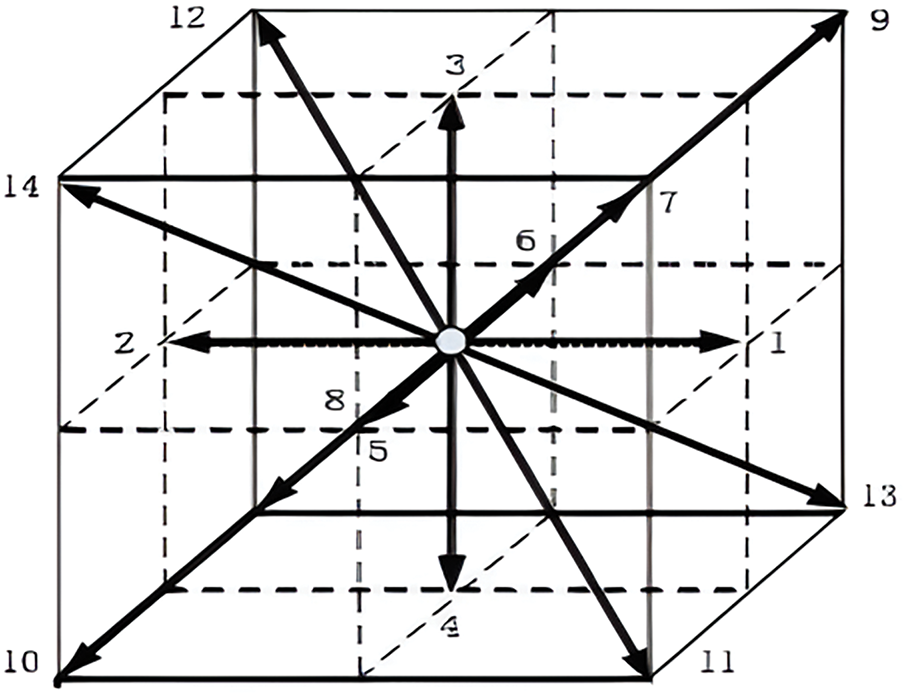

Without loss of generality, the three-dimensional D3Q15 model is selected, as shown in Fig. 2. The relevant parameters in the LBM iteration format are:

here,

Figure 2: Lattice discrete velocity mode of three dimensional D3Q15

By calculating the moment of the distribution function, we can obtain the macroscopic physical quantities velocity and temperature of fluid flow in laser welding:

here,

On the boundary of solid-liquid interface, the boundary conditions can be acquired by utilizing the rebound scheme after incorporating pertinent correction terms to lattice Eqs. (7) and (8) of momentum and energy. Moreover, on other boundaries, the non-equilibrium rebound scheme can be used, so the initial and boundary conditions of the LBM model can be stated as:

here,

4 Numerical Simulation Analysis

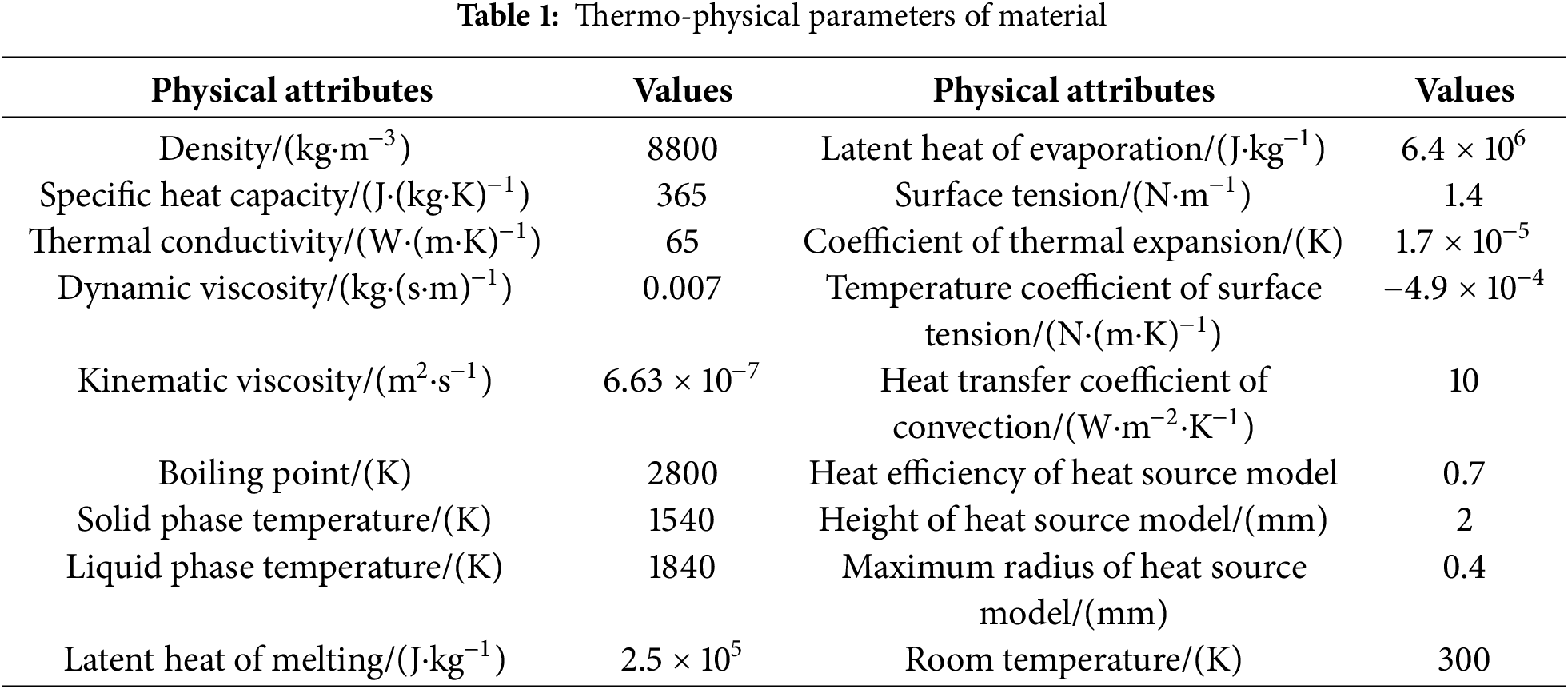

The materials are the unleaded-tin solder and the TU1 oxygen free copper alloy, and the size of interconnection belt is 1 mm × 0.15 mm × 0.125 mm, the size of busbar is 6 mm × 0.35 mm × 0.325 mm. Table 1 is the main thermophysical properties of materials. Please refer to the literature [22] for the measurement method of thermo-physical parameters. The laser is a 500 W medium power continuous fiber laser, the welding speed is 20 mm/s and the spot diameter is 1 mm.

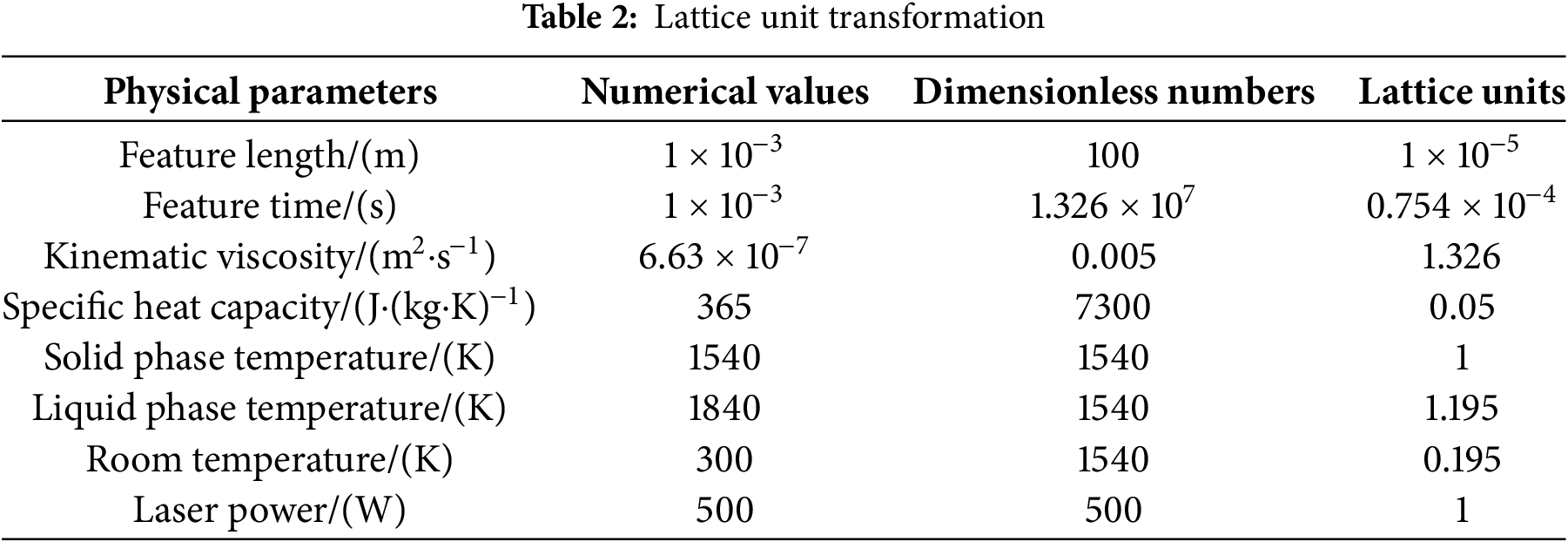

When programming the LBM evolution equations, the feature length and feature time can be introduced, and then the actual thermophysical parameters of materials can be converted into dimensionless lattice units [23]. The conversion result of lattice unit is shown below (Table 2):

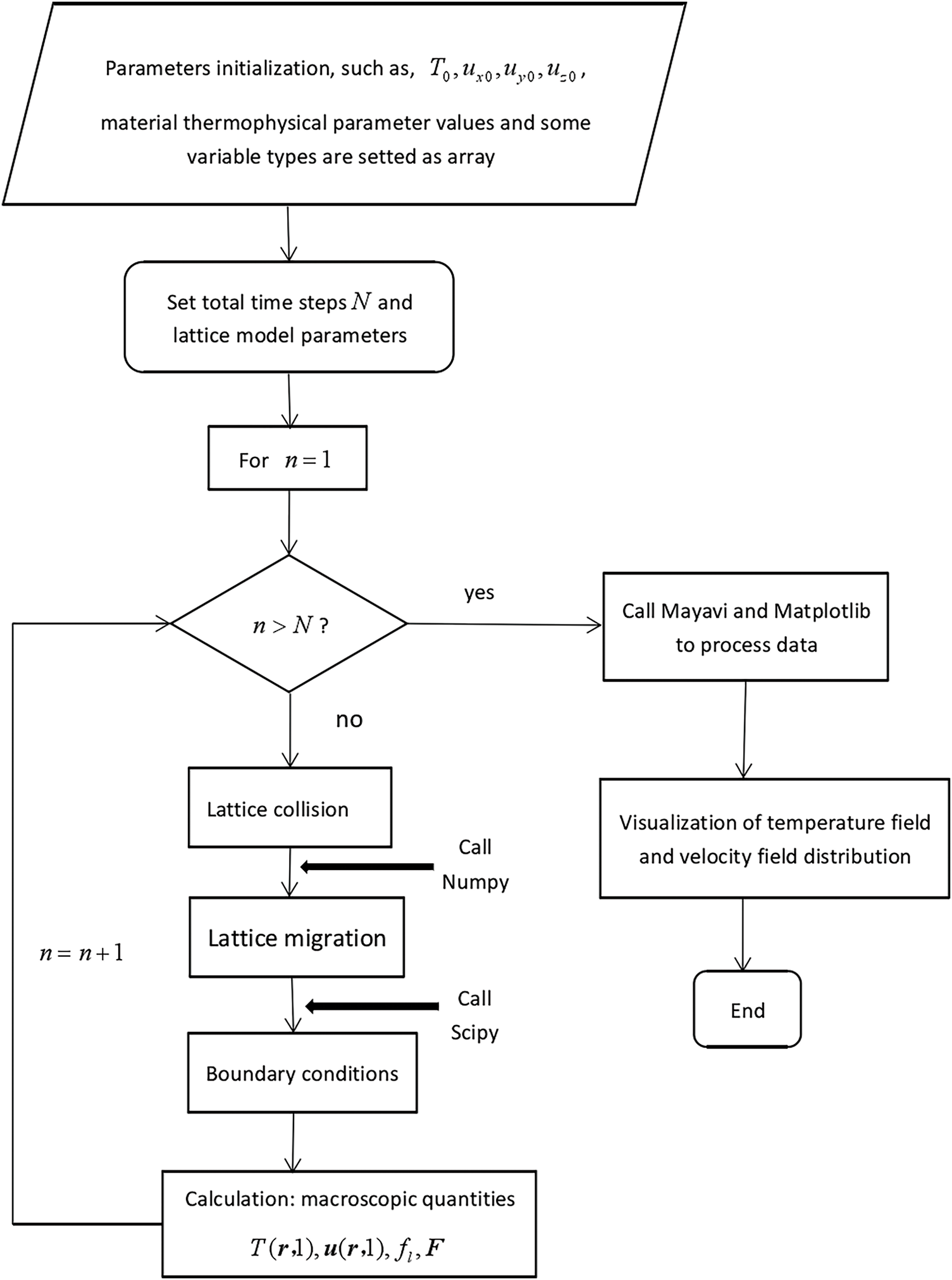

In this numerical replication, because of geometric symmetry, the calculation discipline involves half of the factual workpiece. The Python verbal communication is utilized for programming, we largely use expansion packages as an example Numpy, Scipy, Mayavi and Matplotlib. In the program, the “for loop” is changed into the array calculation over Numpy, and the “if-else” judgment logic engaged in piecewise functioning is changed to the means logic of “zeroing are immaterial values” over Scipy. The program manner movement as said by Python is displayed in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The flow chart of program

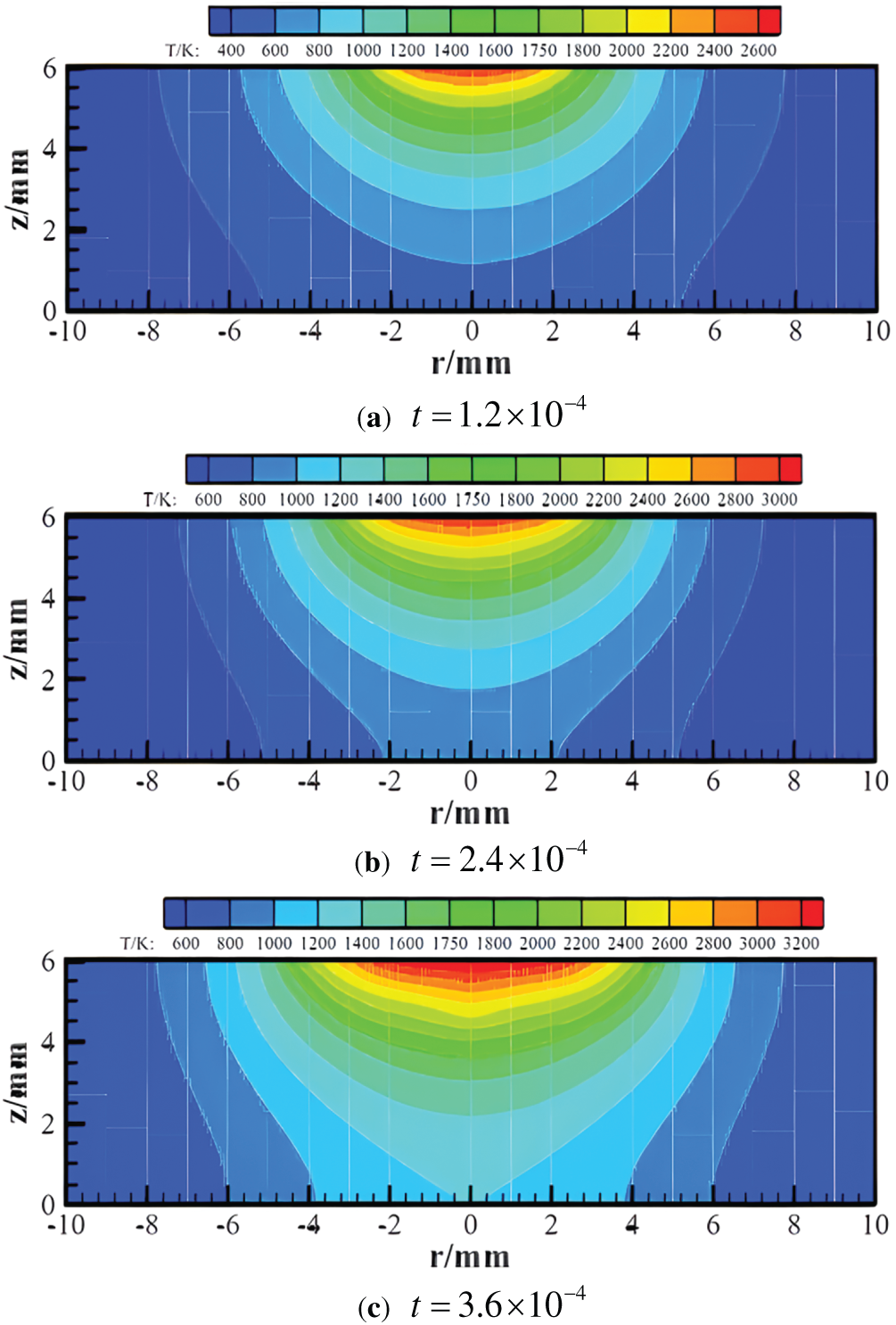

The Fig. 4 is the dynamic process of the temperature field distribution of solar panel busbar laser welding at a weld position when the lattice time is

Figure 4: Temperature field of weld pool at different time

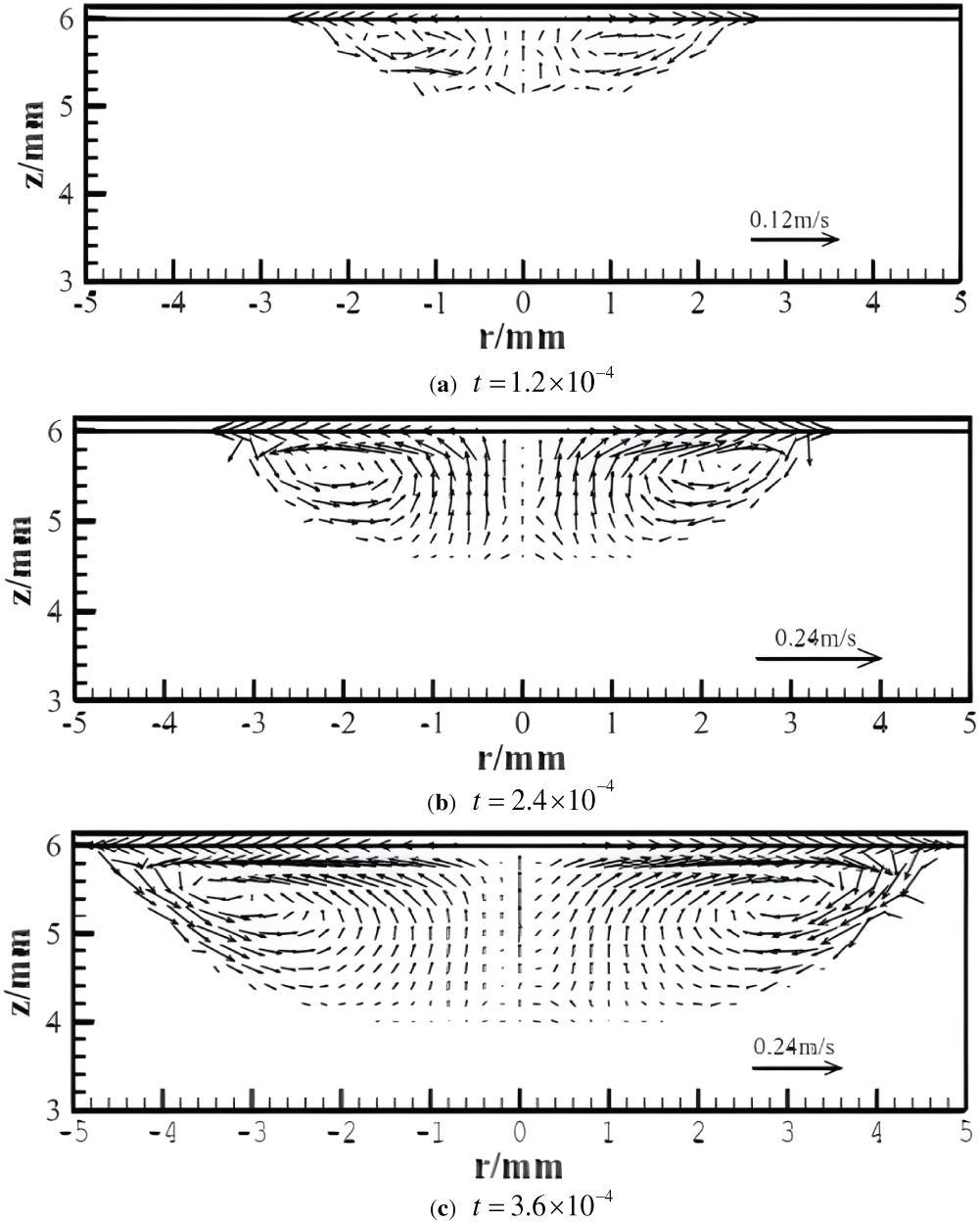

Fig. 5 is the dynamic process of the velocity field distribution of solar panel busbar laser welding at a weld position when the lattice time is

Figure 5: Velocity field of weld pool at different time

To sum up, during the busbar laser welding, the hot fluid in the center of weldpool flows to the edge, which increases the weld width and decreases the weld depth, thus forming a “wide and shallow” molten pool morphology.

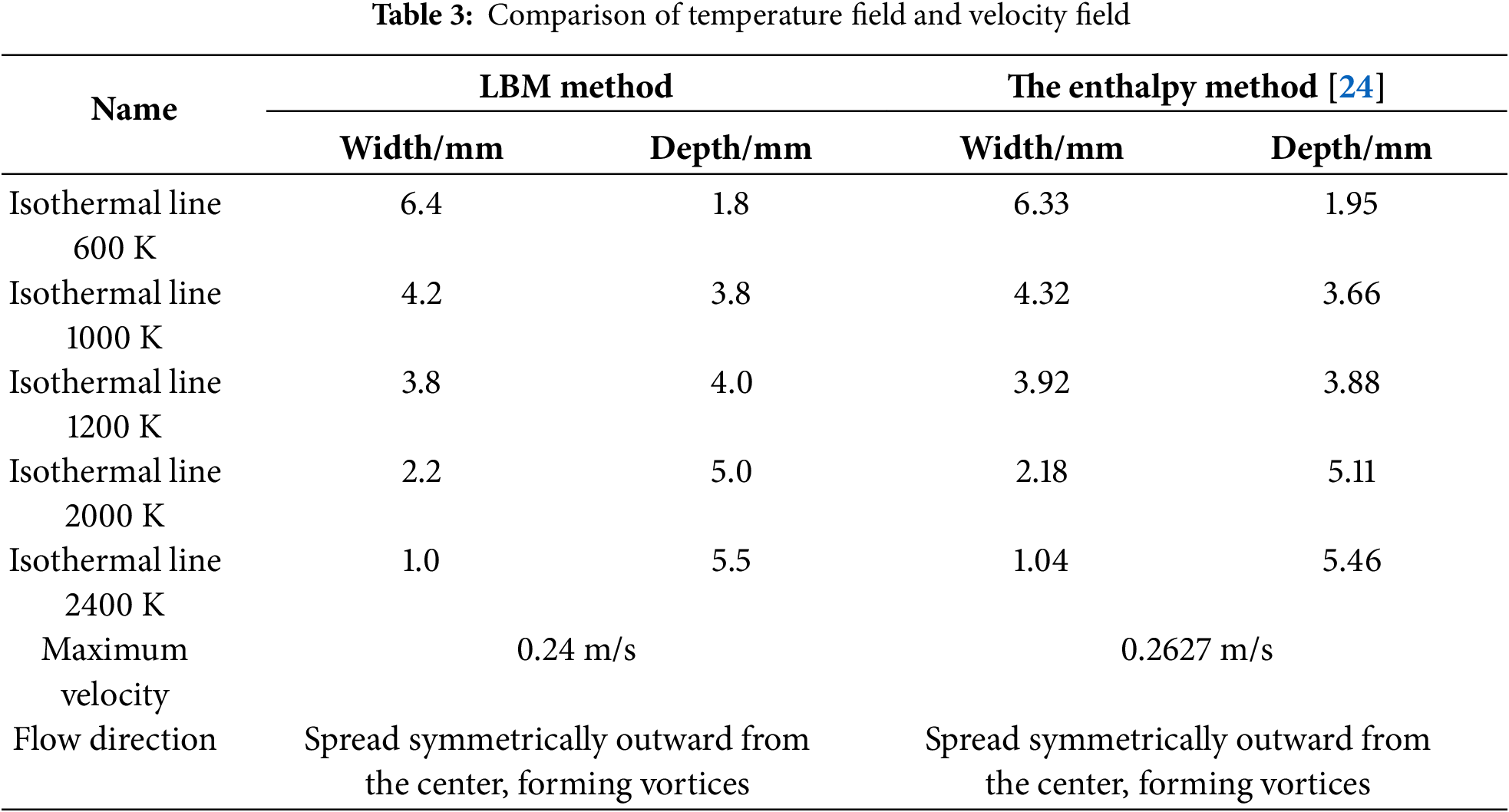

To confirm the precision of the LBM procedure in simulating the climate and velocity fields below the rotating Gaussian heat source algorithm, it was compared and verified with the numerical replication of laser welding as said by enthalpy procedure [24]. The enthalpy procedure adopts the power equation with enthalpy and applies it to the warmth progression replication of melting procedure. Determining the boundary of liquefy pool by tracking the situation of the liquidus cold fitting with the enthalpy.

The thermophysical parameters, heat source parameters, momentum equation, energy equation, and boundary conditions are consistent with the reference [24]. The relative mistake is calculated by the ratio of the absolute disagreement between the LBM and enthalpy procedure outcomes to the enthalpy procedure outcomes. Table 3 reveals the cold and velocity fields of two methods. As per the comparison outcomes, there exists a highest relative mistake of 3.846% between LBM and the liquefy pool width acquired as said by enthalpy procedure, and a highest relative mistake of 7.692% in the liquefy pool depth. It is obvious that the relative mistake between the width and depth of the dissolution pool calculated by LBM and the results based on enthalpy method is less than 8%, indicating the reliability of LBM calculation.

Additionally, it might be seen from the Table 3 that as said by the enthalpy procedure, the highest velocity in the velocity area of study is about 0.2627 m/s, and the highest velocity in the velocity area of study of LBM is 0.24 m/s. The velocity and progression direction in the two dissolution pools are consistent. The overhead verification denotes that there exist a powerful consistency between the outcomes acquired from the common LBM and the enthalpy methods informed in the mention [24], that ensures the precision of the LBM algorithm at present utilized in the task.

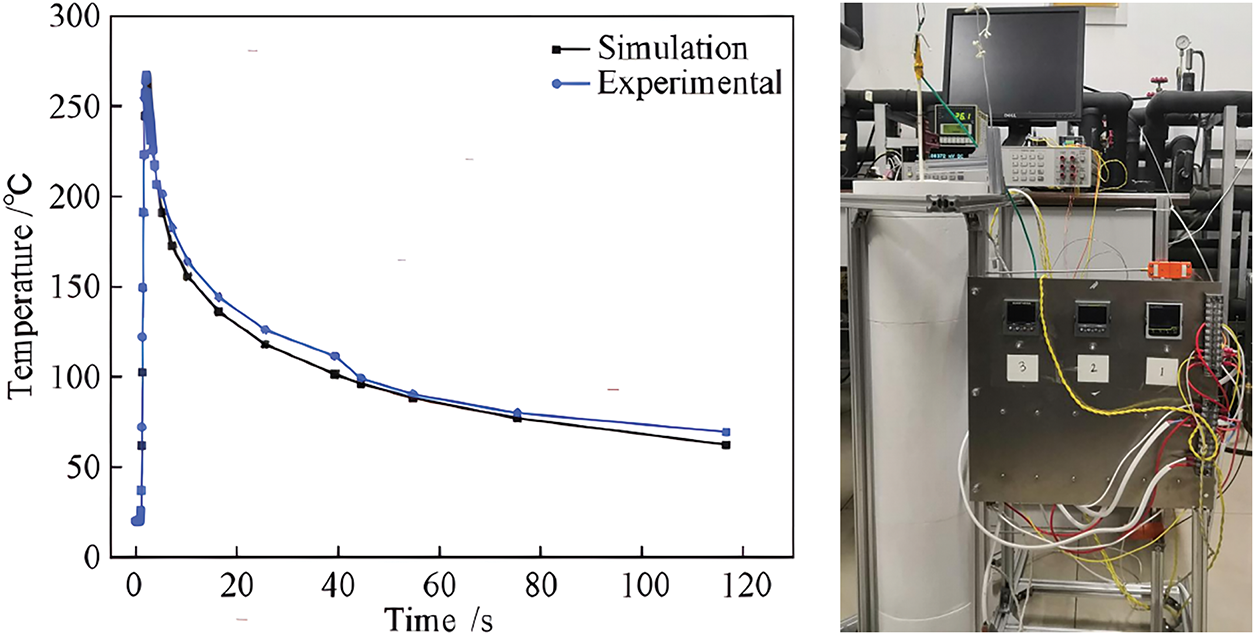

To confirm the correctness of the mathematical algorithm and lattice Boltzmann numerical procedure for laser welding of solar panel busbar in this notes, laser welding off-site fabricating is conducted below similar materials specification and similar procedure limits. classic for comparison, the K-type thermocouple climate measuring intention is utilized to gauge the thermal cycle arc at the node from the weld middle line 0.1 mm, where needs to be drilled and a high-temperature ceramic sleeve utilized to improve the thermocouple measuring end. The Fig. 6 is the comparison between the replication outcomes and the experimental outcomes. It might be seen from Fig. 6 that the replication information are smaller than the experimental information, but their alter trends are identical and the relative deviation is diminutive, so the outcomes are consistent. Hence, the replication formed in this money as said by LBM can more accurately foretell the qualities of heat transfer and fluid movement in of busbar laser welding procedure, that has more user-friendly study on the welding procedure.

Figure 6: Comparison of experimental result and simulation result of thermal cycle curve

The replication outcomes of LBM are in comaprison with the experimental outcomes. The node thermal cycle arc illustrates that the replication data are entirely in agreement with the experimental data, and the mistake is smaller, that illustrates that the LBM of laser welding of solar panel busbar is precise and dependable.

This document utilizes the LBM to analyze the distribution of temperature and flow fields in the laser welding process of solar panel busbars. Utilizing this technique circumvents the constraints inherent in finite element approaches in the study of computational fluid dynamics. Key findings can be summarized thus:

(1) An established three-dimensional lattice Boltzmann mathematical model serves to characterize the process of welding solar panel busbar lasers. The model takes into account the impacts of surface tension and the transition from solid to liquid phases, along with the outlined boundary condition treatment approaches for momentum and energy. The algorithmic software utilizes Python-based array logic, enhancing computational efficiency.

(2) Utilizing the lattice Boltzmann method, a technique that simulates fluid dynamics based on particles, it’s capable of accurately replicating intricate fluid dynamics and heat transfer events in laser welding. This technique, through mimicking the movement and impact of fluid particles, is capable of precisely depicting the large-scale dynamics of fluids.

(3) The arrangement of temperature and velocity fields reveals the significant impact of surface tension on the movement and thermal exchange of metal fluid. There is a notable drop in temperature moving from the weldpool’s core to its outer edges. The liquid descends from the weldpool’s surface center to its base, proceeds along the bond line to its surface, and ultimately bends back from the weldpool’s edge to its center, creating a vortex. As the duration of busbar laser welding extends, the convection within the weldpool intensifies progressively, leading to a steady rise in both penetration and width. However, this increase in penetration is not as significant as the width itself, resulting in a “broad and shallow” shape of the molten pool.

(4) The lattice Boltzmann technique exhibits inherent parallelism, making it apt for extensive parallel computing. When simulating laser welding numerically, this technique can greatly enhance computational speed and reduce the duration of the research process.

Additionally, this document will further explore how welding power and speed affect the microstructure and characteristics of solar panel busbar laser welding.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: Science and Technology Research Key Competitive Project of Quzhou Science and Technology Bureau (Nos. 2023K266, 2024K010), General Project for Cultivating Outstanding Young Teachers in Anhui Province’s Universities (2025).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Mingliang Zheng; data collection: Dongfang Li; analysis and interpretation of results: Dongfang Li; draft manuscript preparation: Dongfang Li. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Mingliang Zheng, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Dieng B, Tine JP, Mbodji S. Solar panels optimization for a better efficiency and for hot water production: determination of the exchange coefficient. Int J Eng Technol. 2020;12(3):476–82. doi:10.21817/ijet/2020/v12i3/201203005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Skupov AA, Panteleev MD, Shcherbakov AV, Shein EA, Belozor VE. Laser welding of fuselage panels from aluminum V-1579 and aluminum-lithium V-1481 alloys. Weld Int. 2022;36(2):92–6. doi:10.1080/09507116.2022.2031757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Balasubramanian KR, Suthakar T, Sankaranarayanasamy K, Buvanashekaran G. Laser welding simulations of stainless steel joints using finite element analysis. Adv Mater Res. 2011;383–390:6225–30. doi:10.4028/www.scientific.net/amr.383-390.6225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. He LJ, Zhang TL, Xu G, Ma CW. Numerical simulation of dynamic behavior of molten pool in laser deep penetration welding. Intell Comput Appl. 2021;11(3):124–9,133. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

5. Wang ZJ, Jiang S, Chen Y. Numerical simulation of laser welding of magnesium and steel dissimilar metal based on ABAQUS. J Mater Heat Treat. 2021;42(7):134–41. (In Chinese). doi:10.1088/1757-899X. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang Y, Hossein Razavi Dehkordi M, Javad Kholoud M, Azimy H, Li Z, Akbari M. Numerical modeling of the temperature distribution and melt flow in dissimilar fiber laser welding of duplex stainless steel 2205 and low alloy steel. Opt Laser Technol. 2024;174(2):110575. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.110575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang J, Dehkordi MHR, Kholoud MJ, Azimy H, Daneshmand S. Experimental and numerical study of melt flow, temperature behavior and heat transfer mechanisms during the dissimilar laser welding process. Opt Laser Technol. 2025;180(4):111521. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2024.111521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Seta T, Takada N. Preface: lattice Boltzmann method. Multiph Sci Technol. 2022;34(3):10–5. doi:10.1615/multscientechn.v34.i3.10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Ezzatneshan E, Salehi A, Vaseghnia H. Study on forcing schemes in the thermal lattice Boltzmann method for simulation of natural convection flow problems. Heat Trans. 2021;50(8):7604–31. doi:10.1002/htj.22245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Eichler P, Fučík R, Strachota P. Investigation of mesoscopic boundary conditions for lattice Boltzmann method in laminar flow problems. Comput Math Appl. 2024;173(6):87–101. doi:10.1016/j.camwa.2024.08.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Agarwal G, Singh S. Coupling of first collision source method with Lattice Boltzmann Method for the solution of neutron transport equation. Ann Nucl Energy. 2022;175(2):109242. doi:10.1016/j.anucene.2022.109242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Fijneman AJ, Goudzwaard M, Keizer ADA, Bomans PHH, Gebäck T, Palmlöf M, et al. Local quantification of mesoporous silica microspheres using multiscale electron tomography and lattice Boltzmann simulations. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2020;302:110243. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2020.110243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Matyka M, Dzikowski M. Memory-efficient Lattice Boltzmann Method for low Reynolds number flows. Comput Phys Commun. 2021;267:108044. doi:10.1016/j.cpc.2021.108044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Montessori A, Lauricella M, Tiribocchi A, Durve M, La Rocca M, Amati G, et al. Thread-safe lattice Boltzmann for high-performance computing on GPUs. J Comput Sci. 2023;74(2):102165. doi:10.1016/j.jocs.2023.102165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li L, Wu M, Zhou L. Lattice Boltzmann simulations for melting and resolidification of ultrashort laser interaction with thin gold film. Int J Thermophys. 2018;39(7):88. doi:10.1007/s10765-018-2409-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Hu Y, Xiong Z, Yan F, Liu Z, Zhao Z, Wang C. Investigation of collapse defect suppression in 20 mm-thick plate laser penetration welding via beam energy spatial control. J Manuf Process. 2025;151(1):408–25. doi:10.1016/j.jmapro.2025.07.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ruhi A, Raghurama Rao SV, Muddu S. A lattice Boltzmann relaxation scheme for incompressible fluid flows. Int J Adv Eng Sci Appl Math. 2022;14(1):34–47. doi:10.1007/s12572-022-00320-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bellotti T, Graille B, Massot M. Finite Difference formulation of any lattice Boltzmann scheme. Numer Math. 2022;152(1):1–40. doi:10.1007/s00211-022-01302-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Kohanpour MS, Imani G. Lattice Boltzmann study of fluid flow and heat transfer characteristics of a heated porous elliptic cylinder: a two-domain scheme. Int J Numer Meth Heat Fluid Flow. 2023;33(1):282–310. doi:10.1108/hff-04-2022-0233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Boolakee O, Geier M, De Lorenzis L. A new lattice Boltzmann scheme for linear elastic solids: periodic problems. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2023;404(20):115756. doi:10.1016/j.cma.2022.115756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Chatterjee D, Chakraborty S. An enthalpy-based lattice Boltzmann model for diffusion dominated solid-liquid phase transformation. Phys Lett A. 2005;341(1–4):320–30. doi:10.1016/j.physleta.2005.04.080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhao J. Experimental study on heat transfer coefficient of copper alloy and ultra high strength steel in contact with mold materials [dissertation]. Dalian, China: Dalian University of Technology; 2024. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

23. Succi S. Lattice Boltzmann equation: for fluid dynamics and beyond. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

24. Kou S, Sun DK. Fluid flow and weld penetration in stationary arc welds. Metall Trans A. 1985;16(2):203–13. doi:10.1007/BF02816047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools