Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Flowback Behavior of Deep Coalbed Methane Horizontal Wells

1 China United Coalbed Methane National Engineering Research Center Co., Ltd., Beijing, China

2 PetroChina Coalbed Methane Co., Ltd., Beijing, China

3 Petrochina (Tianjin) International Petroleum Exploration & Development Technology Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China

4 School of Energy Resources, China University of Geosciences, Beijing, China

* Corresponding Author: Yanqing Feng. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Multiphase Fluid Flow Behaviors in Oil, Gas, Water, and Solid Systems during CCUS Processes in Hydrocarbon Reservoirs)

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2026, 22(1), 10 https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2026.075630

Received 05 November 2025; Accepted 27 January 2026; Issue published 06 February 2026

Abstract

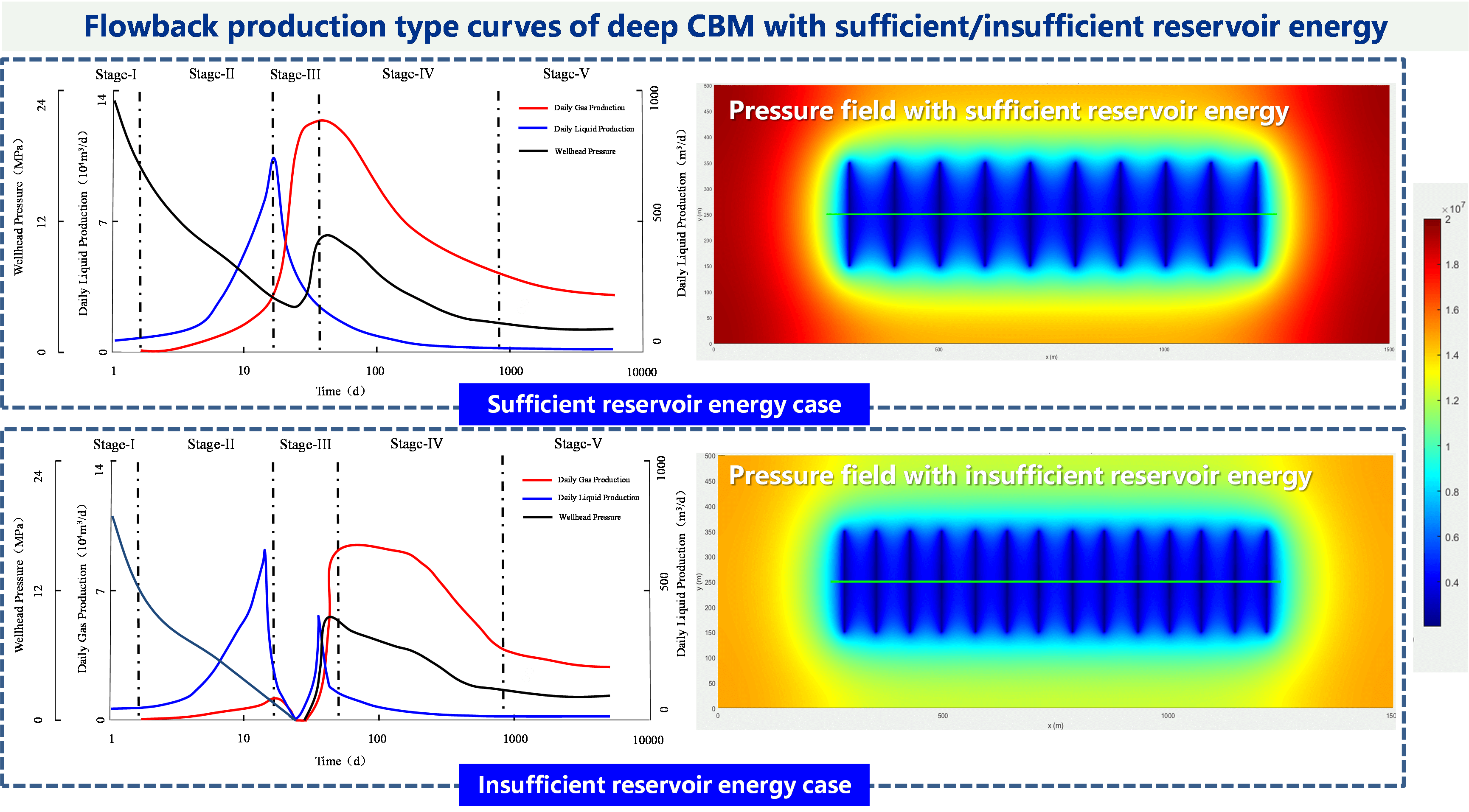

Significant differences exist between deep and medium-shallow coalbed methane (CBM) reservoirs. The unclear understanding of flowback and production behavior severely constrains the development of deep CBM resources. To address this challenge, guided by the gas-liquid two-phase flow theory in ultra-low permeability reservoirs, and integrating theoretical analysis, numerical simulation, and insights from production practices, this study classifies the flowback and production stages of deep CBM well considering the Daning-Jixian Block, Eastern Ordos Basin as a representative case. We summarize the flowback characteristics for each stage and establish a standard flowback production type curve, aiming to guide field operations. The results indicate that: (a) The production process of deep CBM horizontal wells can be divided into five distinct stages: initial single-phase water dewatering stage, initial gas appearance to peak water production stage, gas breakthrough to peak gas production stage, stable production and decline stage, and low-rate production stage. (b) Based on reservoir energy, two standard type curves for horizontal well flowback production are established: the ‘Sufficient Reservoir Energy’ type and the ‘Insufficient Reservoir Energy’ type. The former achieves a higher initial gas rate (up to 12 × 104 m3/d) but exhibits poorer stability, while the latter achieves a lower stable rate (up to 8 × 104 m3/d) but demonstrates stronger stability. Numerical simulation confirms these behavioral patterns and reveals the underlying mechanisms related to the effectively drained area where pressure is significantly depleted. The findings from this study have guided the flowback production operations in 53 deep CBM wells with positive results, demonstrating high potential for broad application.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

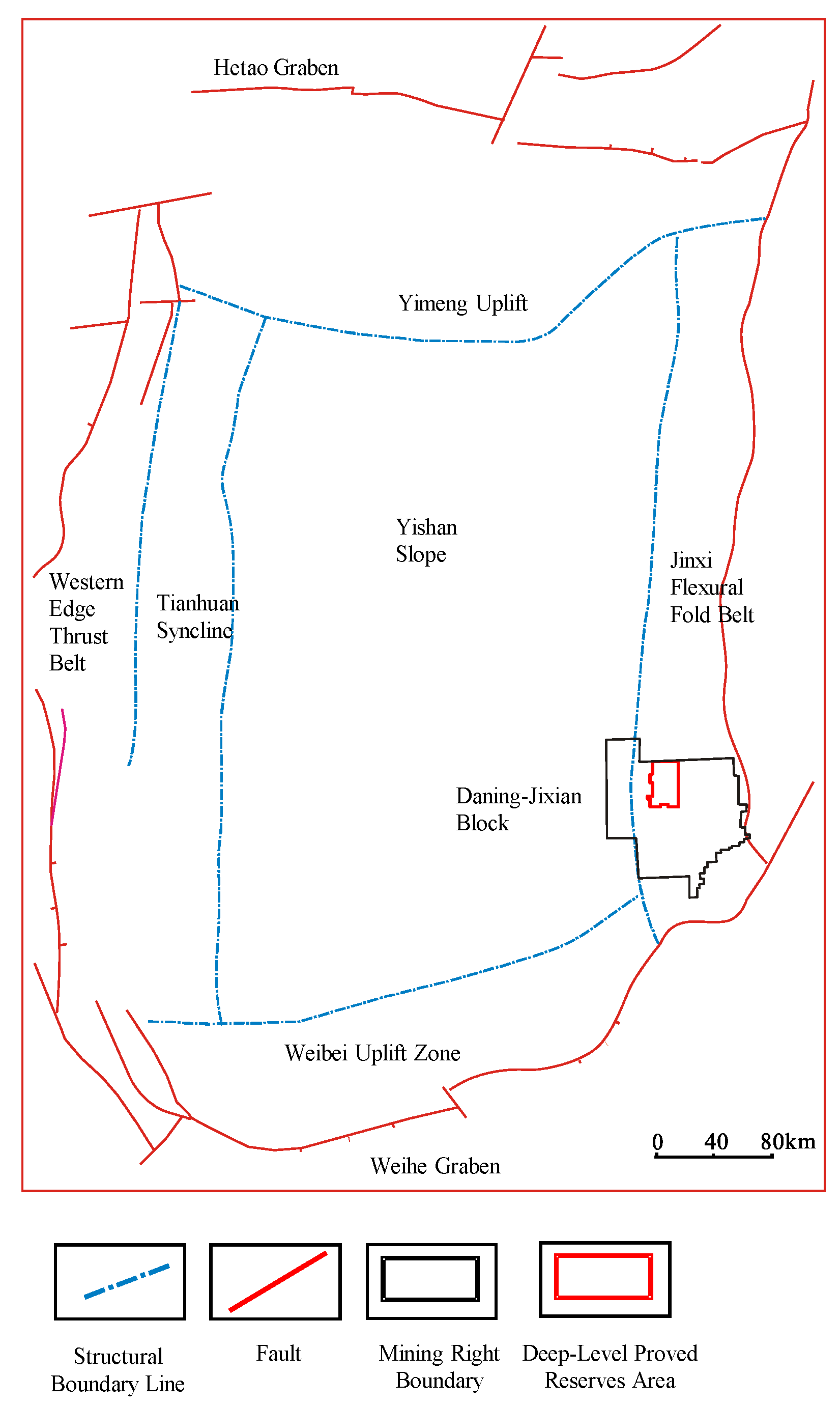

The study area is located in the Daning-Jixian Block, situated on the eastern margin of the Ordos Basin, which is noteworthy for its geological and resource characteristics (Fig. 1). This region is particularly rich in various vertically stacked resources, prominently featuring coalbed methane (CBM), tight gas, and shale gas. The geological structure within the study area is relatively simple, characterized by gently dipping strata with an angle of less than 2 degrees and a distinct lack of significant faults. Previous research primarily focused on deep coal seams, which were studied mainly as source rocks. However, these seams had not been systematically examined as potential reservoirs for gas production until more recently [1,2]. Since 2018, there have been significant breakthroughs in the cost-effective development of deep coalbed methane, which has propelled the implementation of two innovative pilot projects along with a substantial construction project aimed at achieving a production capacity of 1 billion cubic meters annually (bcm/a). As a result of these efforts, the Daning-Jixian Block has established itself as a pioneering deep CBM field in China, boasting an impressive annual output that exceeds one million tons of oil and gas equivalent. This milestone marks a substantial achievement in the country’s energy landscape and underscores the region’s importance in the broader context of natural resource development.

Figure 1: Location of the deep coalbed methane (CBM) proved reserves area in the Daning-Jixian Block, eastern margin of the Ordos Basin.

Current operational practices within the block reveal marked differences between deep CBM horizontal wells and their medium-shallow CBM counterparts. These differences manifest in various aspects, including drilling techniques, fracturing operations, and flowback production methodologies [3,4,5]. A notable challenge arises from the considerable variability observed in critical aspects of post-fracturing flowback, such as the duration of flowback time, the recovery rates of fracturing fluids, and the distinctive characteristics of gas and water production [6,7,8]. These factors are particularly intriguing, given that they can vary significantly even among wells situated within the same geological block and under similar engineering conditions. Such variability can subsequently lead to substantial differences in well productivity outcomes [9,10], making it essential to closely examine these phenomena to enhance understanding of the underlying mechanisms.

In light of these observations, there is an urgent need to conduct thorough investigations into the post-fracturing flowback behavior of deep CBM wells. This exploration is crucial for better evaluating their productivity potential and developing tailored production management systems that can optimize output and efficiency. Currently, there is a notable gap in the literature, as no published research findings specifically addressing the flowback behavior of deep CBM wells have been made available, neither within China nor on an international scale [11,12,13,14]. This absence of data presents a unique opportunity for further research and exploration into this pivotal aspect of deep CBM development.

Consequently, this study aims to provide a comprehensive analysis of the geological characteristics relevant for development, fracturing engineering principles, and the unique flowback production features associated with deep CBM. By integrating empirical data from flowback and production experiences, the research investigates the intricacies of post-fracturing flowback behavior specifically for deep CBM horizontal wells. The findings of this study are anticipated to offer crucial guidance for optimizing field flowback operations, thereby enhancing recovery rates and overall performance in deep CBM development endeavors. This research not only aims to fill the existing knowledge gap but also seeks to contribute valuable insights that can benefit industry stakeholders and policymakers alike.

2 Development Characteristics of Deep Coalbed Methane

There are significant differences between deep and medium-shallow coalbed methane (CBM) reservoirs that impact their development and production potential. Understanding these differences is crucial for optimizing extraction strategies. The development characteristics of deep CBM reservoirs can be summarized in three key areas: development geology [15,16], fracturing engineering [17,18], and flowback production [19,20]. The Daning-Jixian Block represents China’s first and most productive deep CBM field, making it a highly representative case for studying deep CBM characteristics. To clarify the distinctions between deep and medium-shallow CBM reservoirs, Table 1 summarizes key differences in geological, engineering, and production aspects. These differences directly influence development strategies: deep CBM requires horizontal wells with large-scale multi-stage fracturing to overcome ultra-low permeability, whereas medium-shallow CBM often uses vertical wells with smaller-scale stimulation.

Table 1: Comparisons between deep CBM and medium-shallow CBM.

| Characteristics | Deep CBM | Medium-Shallow CBM | Influences on Deep CBM Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth (m) | >1500 m (typically 2000–2500 m) | <1500 m (typically 500–1000 m) | Higher stress, lower permeability, requiring more aggressive fracturing. |

| Initial pressure | Normal to high | Normal to low | Higher reservoir energy in deep CBM favors faster initial flowback. |

| Permeability (mD) | Ultra-low (0.0001–0.001 mD) | Low to moderate (0.1–10 mD) | Horizontal wells with large-scale hydraulic fracturing are essential for economic production. |

| Gas Content | High, with significant free gas | Mainly adsorbed gas | Deep CBM exhibits a “free gas + adsorbed gas” co-production mechanism. |

| Fracturing Scale | Large-volume, high proppant concentration | Moderate volume and proppant | Deep CBM requires more fluid and proppant to create effective fracture networks. |

| Flowback Behavior | Rapid initial gas, but may decline quickly | Slower gas appearance, more stable decline | Flowback strategy must be adjusted to reservoir energy (sufficient vs. insufficient). |

2.1 Geological Characteristics for Deep CBM Development

The target layer in this study is the No. 8 coal seam of the Taiyuan Formation. The overall geological structure is relatively simple, featuring a continuously developed coal seam, high gas content, relatively well-developed fractures, and effective sealing conditions in both the roof and floor. Additionally, it operates under a normal pressure system. However, there are minor variations between the northern and southern parts of the study area in terms of micro-structures, burial depth, coal seam thickness, gas-bearing properties, and fracture development. The primary structural feature of the roof of the No. 8 coal seam is a northwest-dipping slope, characterized mainly by gentle structural areas and positive micro-structural areas. The northern section is relatively flat, while the southern section shows low-amplitude uplifts. The burial depth of the No. 8 coal seam generally ranges from 2200 to 2360 m in the north and from 2100 to 2220 m in the south. The thickness of the coal seam is predominantly between 8 to 10 m in the north and 5 to 8 m in the south, indicating that the seam is thicker in the northern section.

Fracture development, predicted through pre-stack seismic azimuthal anisotropy and ant body tracking, indicates that fractures are generally well-developed, with a greater degree of development in the south compared to the north [17,18]. The distribution of coal rock thermal maturity shows higher values in the north and lower values in the south, with vitrinite reflectance (R0) ranging from 2.4% to 3.0% in the north and from 2.1% to 2.6% in the south. The higher thermal maturity in the north enhances hydrocarbon generation capacity, making it more capable of generating hydrocarbons and providing better gas content than the south. These differences lead to greater reservoir energy in the north compared to the south, thereby facilitating the formation of coalbed methane (CBM) reservoirs with higher saturation [19,20,21,22,23,24].

2.2 Fracturing Engineering Characteristics for Deep CBM Horizontal Wells

Deep coal reservoirs are distinguished by their unique geological characteristics, primarily low porosity and ultra-low permeability, which create significant challenges for effective resource extraction. As a result, these reservoirs are typically developed using advanced techniques such as horizontal drilling combined with large-scale multi-stage hydraulic fracturing. To optimize the extraction process from these challenging formations, specific fracturing parameters are essential. For instance, horizontal wells are generally designed to operate at a pumping rate of approximately 20 cubic meters per minute. The fluid volume used per well can range significantly, typically between 23,000 and 53,000 cubic meters, depending on the particular geological conditions and operational goals. In terms of proppant usage, each well usually requires a proppant volume ranging from 3500 to 7600 cubic meters. This proppant plays a critical role in ensuring that the fractures remain open after the hydraulic pressure is released, thereby facilitating the continuous flow of natural gas or coalbed methane. Further emphasizing the granularity of the fracturing approach, the fluid volume required per meter of horizontal wellbore is generally between 27 and 38 cubic meters. Correspondingly, the proppant volume employed per meter averages around 3.5 to 5.5 cubic meters. Notably, there is a regional variation in proppant requirements; in well operations located in the southern regions, the proppant volume needed per meter is approximately 1.1 times greater than that required for wells in northern regions. These parameters not only reflect the technological advances in resource extraction but also underscore the importance of tailored engineering strategies to navigate the complexities associated with deep coal reservoir development. By meticulously adjusting these variables, operators can enhance the efficiency and effectiveness of their extraction processes, potentially leading to improved economic returns and resource recovery rates.

2.3 Flowback Production Characteristics of Deep CBM Horizontal Wells

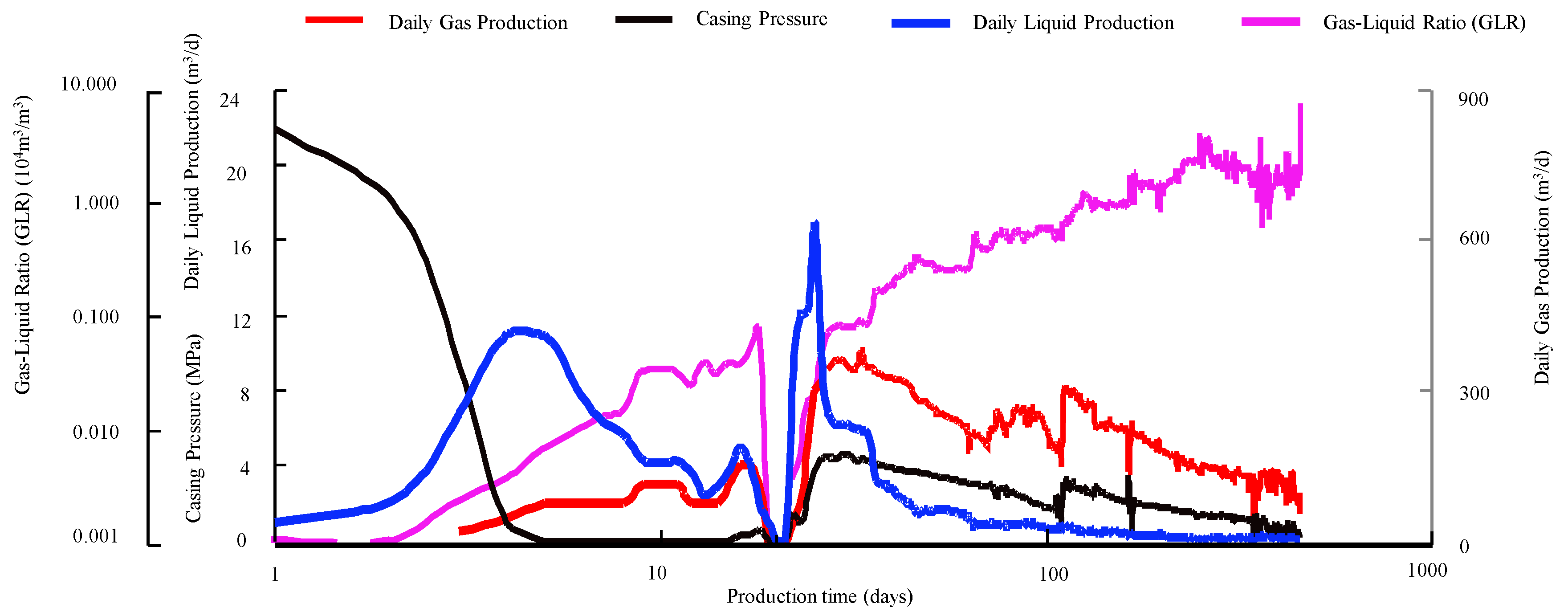

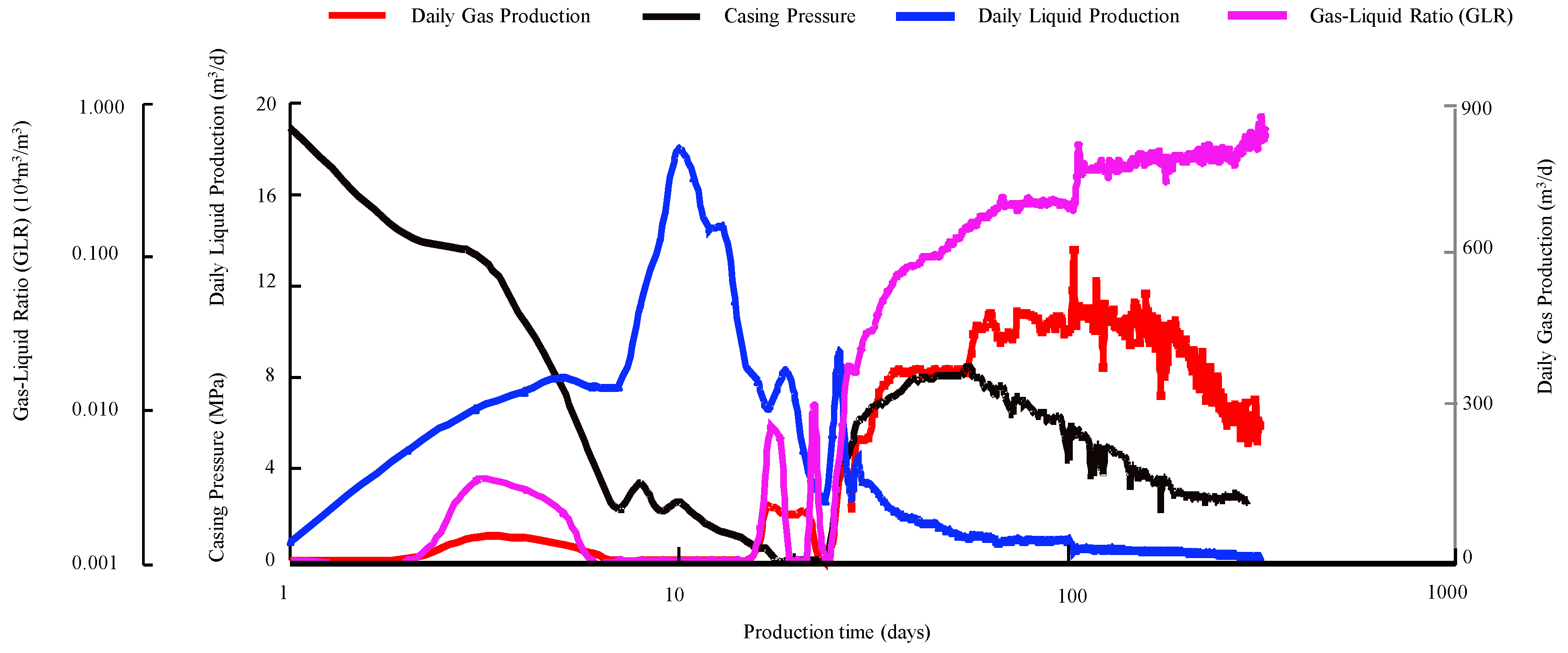

Geological variations create a significant disparity in reservoir energy between the northern and southern parts of the study area, which dramatically influences the flowback production behaviors of deep coalbed methane (CBM) horizontal wells. In the northern region, wells exhibit robust reservoir energy characteristics, resulting in an impressive flowback time of just 20 days and a flowback recovery ratio of 18.4%. Upon commissioning, these northern wells showcase their potential by initially producing gas at rates between 90,000 and 160,000 m3/d, ultimately stabilizing at an impressive 120,000 m3/d (refer to Fig. 2). In stark contrast, wells located in the southern part of the study area struggle with insufficient reservoir energy, as evidenced by a longer flowback time of 24 days. They have a recovery ratio of 21.2%, an initial gas production rate that ranges from 60,000 to 130,000 m3/d, and a stabilized gas rate of only 80,000 m3/d (see Fig. 3). Wells in regions with adequate reservoir energy enter a phase of high and stable production immediately following commissioning, allowing operators to maximize output right from the start. After a brief period of peak production, these wells typically experience a gradual decline, yet their gas-water ratio (GWR) consistently increases and stabilizes at an impressive 10,000 m3/m3. Conversely, wells with insufficient reservoir energy can achieve high and stable production levels after a brief ramp-up period of 30 to 40 days and are capable of maintaining this output for a relatively extended duration. However, their GWR stabilizes at a much lower rate of 5000 m3/m3. This clear distinction in production capabilities underscores the importance of evaluating reservoir energy as a critical factor in overall well performance, revealing that the geological context plays a crucial role in optimizing resource extraction and driving economic viability in the region.

Figure 2: Flowback production curve for Well JS6-7P01 in Daning-Jixian Block (with sufficient reservoir energy).

The differences in production characteristics between the northern and southern regions of the study area can be attributed to several key factors, including geological foundations and the specific techniques employed for fracturing stimulation. First, examining the geological aspects, the northern area is characterized by thicker coal seams, higher gas saturation levels, and a greater free gas content in its coal reservoirs compared to the southern area. These geological advantages provide a more favorable environment for gas production, directly impacting the overall resource potential of the northern region. Second, when we consider fracturing stimulation techniques, the results differ notably between the two regions. In the northern area, wells that have sufficient energy have typically undergone smaller-scale fracturing treatments. In contrast, wells in the southern region that have sufficient energy benefitted from larger-scale treatments. Due to better natural fracture development in the south, larger-scale fracturing treatments create a more complex network, resulting in a larger ESRV (Effectively Stimulated Reservoir Volume). In contrast, northern reservoirs with higher energy require less intensive fracturing, leading to a simpler fracture network and smaller ESRV. ESRV refers to the reservoir volume that is both hydraulically fractured and effectively drained during production. Unlike conventional SRV (Stimulated Reservoir Volume), which only considers fractured volume, ESRV emphasizes the productive portion connected to the wellbore under actual flow conditions.

A comprehensive analysis of the production characteristics reveals that the northern region possesses a high abundance of coal reservoir resources, a rapid initial production ramp-up rate, and a consistently high stabilized daily gas rate. However, the smaller ESRV in this area results in a limited effective drainage area, which poses challenges for maintaining sustainable high-rate production over time. On the other hand, the southern area exhibits relatively lower resource abundance, a slower initial production ramp-up rate, and a lower stabilized daily gas rate. Nevertheless, the larger ESRV achieved through extensive fracturing treatments contributes to a greater effective drainage area. This larger drainage area, in turn, enhances the production stability of the gas wells in the southern region, allowing them to maintain steadier output over longer periods, despite the initial disadvantages in resource abundance and production rates. Overall, the interplay between geological characteristics and fracturing techniques explains the distinct production outcomes observed in these two regions, highlighting the importance of tailored approaches to maximize gas extraction efficiency.

Figure 3: Flowback production curve for Well JS14-5P02 in Daning-Jixian Block (with insufficient reservoir energy).

3 Numerical Simulation of Production Performance for Deep CBM Wells

Field observations from the Daning-Jixian Block have revealed two distinct production behavioral patterns correlated with reservoir energy. To move beyond empirical correlation and gain a mechanistic understanding of these behaviors, particularly the rapid decline in high-energy wells versus the prolonged stability in low-energy wells, a numerical simulation investigation was undertaken. This approach is necessary to quantify the impact of key parameters, such as initial pressure and fracture network extent, on production dynamics and to visualize the evolving pressure fields and drainage areas that are not directly measurable in the field. The following section details the mathematical model and presents simulation results that validate and elucidate the field-based classification.

In coalbed methane development, the injection and flowback of fracturing fluids represent a highly dynamic and complex process of gas-water two-phase flow. To accurately characterize the post-fracturing core mechanism—where injected water rapidly channels through the fracture system while simultaneously imbibing into the matrix, as desorbed gas diffuses within the matrix before ultimately flowing into the fractures for production—it is imperative to adopt a dual-porosity/dual-permeability model that more closely reflects geological reality. This model conceptualizes the reservoir as coupled matrix and fracture systems. Building upon this conceptualization, separate governing equations for gas-water two-phase flow are established for each system. The following section details the governing equations and corresponding auxiliary conditions for both the matrix and fracture systems.

3.1.1 Governing Equations for Gas-Water Two Phase Flow in Coal Matrix

In the matrix, the motion equations for gas-water two phase flow are as follows:

In those equations, subscripts g and w represent gas phase and water phase, respectively; subscript m represents matrix; Km denotes the absolute permeability of the coal matrix, mD; Krg and Krw represent the relative permeability of gas phase and water phase, respectively; Sw represents the water saturation; Pg and Pw represent the pressure of gas phase and water phase, respectively; μg and μw are viscosity of gas phase and water phase, respectively.

In accordance with the gas-water two phase motion equations and the fundamental continuity equation, we obtain the governing equations of each component in coal matrix.

Notably, the coal matrix permeability usually changes with the formation pressure, known as the stress dependence effect, which can be given as the exponential function. Notably, in deep CBM reservoirs under high stress conditions, the permeability change is dominated by stress dependence. Matrix shrinkage effect is relatively minor compared to shallow CBM and is thus neglected in this model to simplify the simulation while preserving key flow mechanisms.

Other complementary auxiliary equations are below.

3.1.2 Governing Equations for Gas-Water Two Phase Flow in Fractures

Because of the significant pressure drop around the wellbore, high flow gases will experience fast, non-Darcy flow in the fracture area, which increases flow resistance. This phenomenon can be characterized by the Forchheimer number, as illustrated in the following equation:

Frederick and Graves’ (1994) second non-Darcy correction equation is used to obtain the β.

Other complementary auxiliary equations are provided below.

3.1.3 Equations for the Capillary Pressure

When fracturing fluid is injected into a reservoir, it seeps into the deeper areas due to significant capillary forces. This seepage determines how the fracturing fluid is distributed within the reservoir, which in turn affects both the backflow rate and the overall productivity of the fracturing fluid. Therefore, capillary force plays a crucial role in this process. In this simulation, the capillary force during the displacement process is calculated using the empirical formula as follows.

The seepage mechanisms differ significantly between the shut-in period and the flowback period. During the shut-in period, the process involves the wet phase displacing the non-wet phase. In contrast, the flowback period features the non-wet phase displacing the wet phase. This difference is characterized by variations in capillary displacement and suction, which leads to a lag in the suction curve. The inhalation curve can be calculated using the following formula.

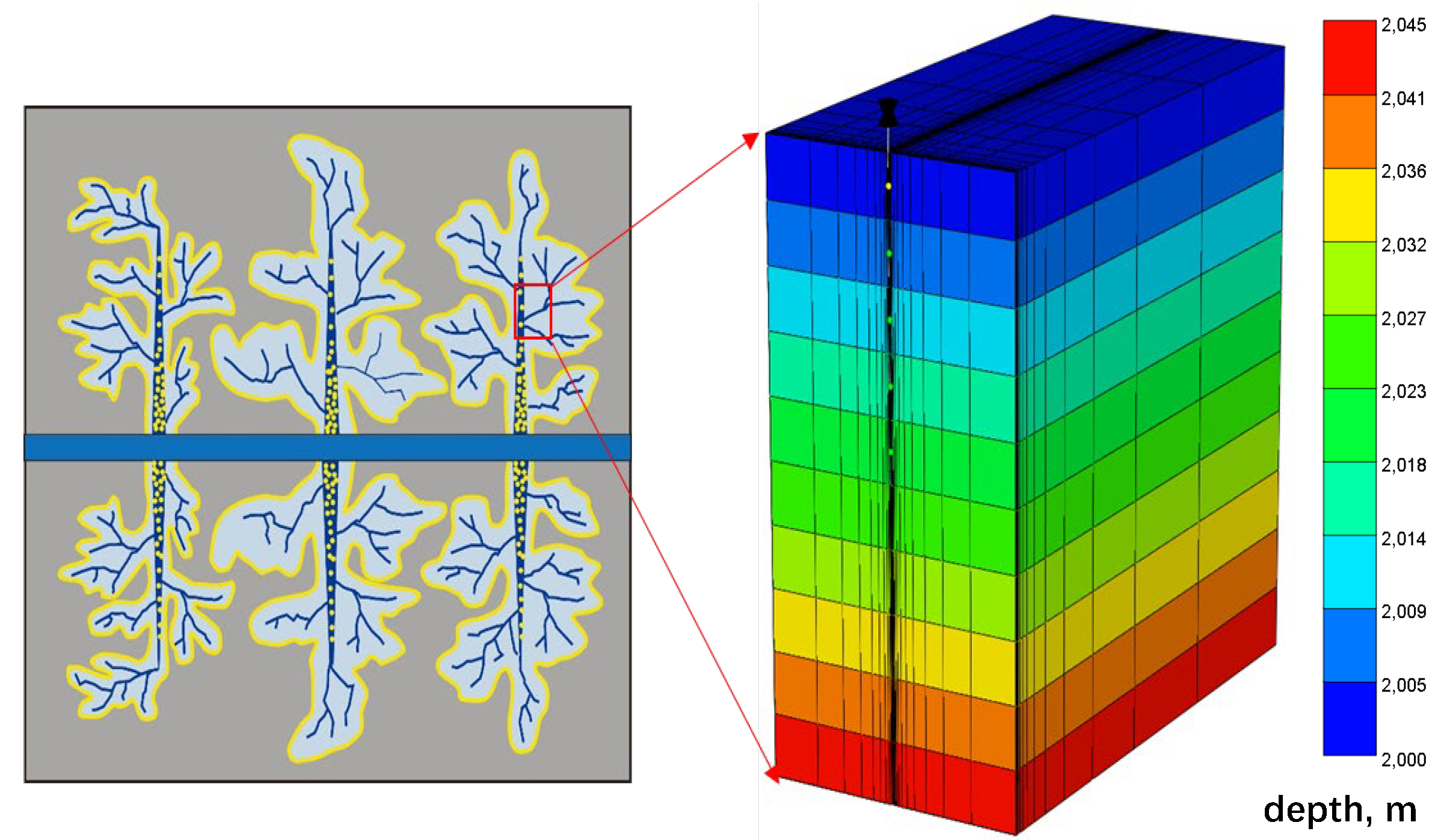

A dual-porosity, dual-permeability numerical model was established using CMG software [25], representing a typical multi-stage hydraulic fracturing horizontal well. The artificial fractures are evenly distributed at both ends of the horizontal section of the well. The horizontal section of the well is 1000 m long. A schematic diagram of the model is provided in the following Fig. 4. To illustrate the difference in production performance between deep coalbed methane (CBM) wells with insufficient reservoir energy and those with sufficient reservoir energy, we utilize two sets of parameters, as shown in Table 1. The initial pressure for the wells with sufficient reservoir energy is set at 20 MPa, while the initial pressure for those with insufficient reservoir energy is 15 MPa. Moreover, the case with insufficient reservoir energy is simulated with 15 fractures, whereas the case with sufficient reservoir energy has 10 fractures. This aligns with field conditions, where coalbeds with insufficient reservoir energy typically exhibit a larger Enhanced Strain Recovery Volume (ESRV). In summary, a dual-porosity/dual-permeability numerical model was adopted to simulate matrix-fracture interaction, which accounts for gas desorption, diffusion, as well as two-phase flow. Main parameters for deep coal seams are listed in Table 1. Temperature, as listed in Table 2, is incorporated into the calculation of gas phase properties, including the gas formation volume factor (Bg) and viscosity (μg), which are pressure- and temperature-dependent. And, fracture counts (10 vs. 15) are based on post-fracturing micro-seismic interpretation. Matrix permeability of 0.0002 mD is derived from core analysis and well test data in deep CBM reservoirs.

Figure 4: The schematic of the established numerical model for the multi-fractured horizontal well.

Table 2: Main parameters utilized in the numerical simulation.

| Parameters | Value | Parameters | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formation thickness | 10 m | Fracture porosity | 0.6 |

| Formation depth | 2000 m (Sufficient reservoir energy) 1500 m (Insufficient reservoir energy) | Fracture permeability | 100 mD |

| Matrix porosity | 0.05 | Formation temperature | 80°C (Sufficient reservoir energy) 65°C (Insufficient reservoir energy) |

| Matrix permeability | 0.0002 mD | Initial formation pressure | 20 MPa (Sufficient reservoir energy) 15 MPa (Insufficient reservoir energy) |

| Number of fractures | 15 (Insufficient reservoir energy) 10 (Sufficient reservoir energy) | Initial water saturation | 0.20 |

| Fracture half-length | 100 m | Coal compressibility | 4 × 10−6 KPa−1 |

| Horizontal wellbore length | 1000 m | Bottom-hole pressure | 3 MPa |

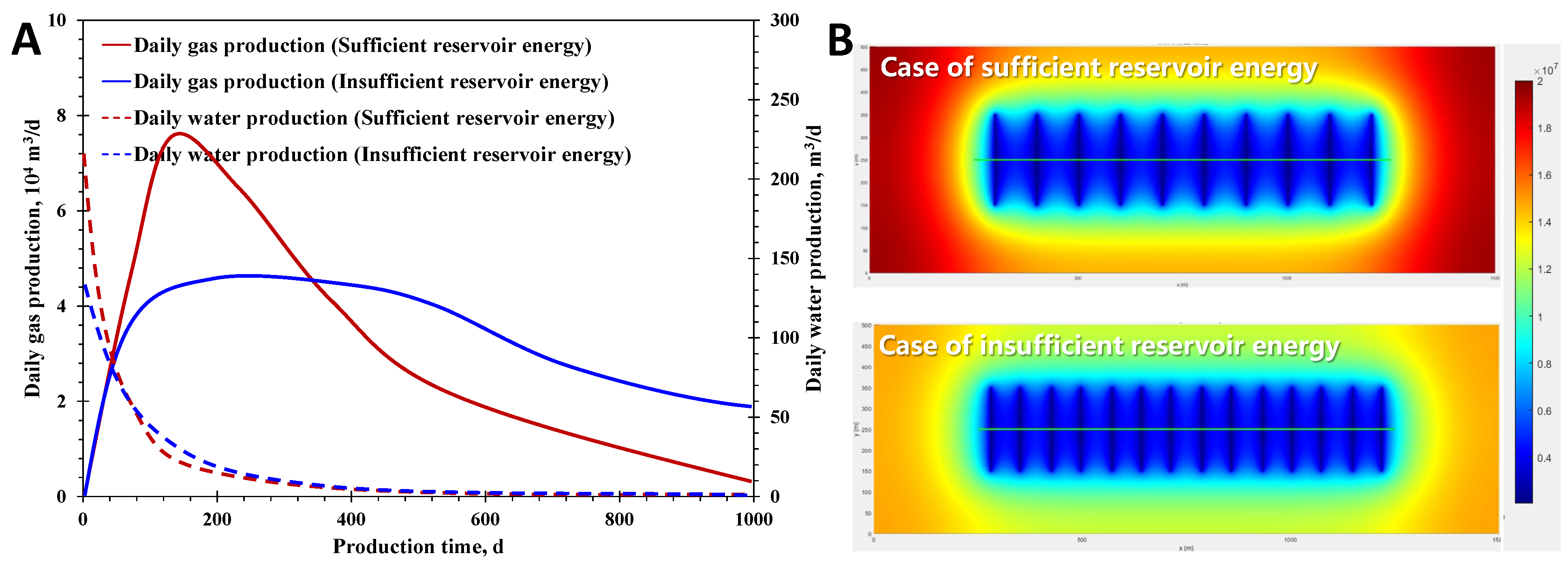

As depicted in Fig. 5A, the production trend analysis reveals two distinct profiles that significantly impact gas output over time. In scenarios characterized by sufficient reservoir energy, the gas production rate experiences a swift peak, reaching impressive levels of up to 80,000 m3/d. However, this initial surge is followed by a pronounced decline, indicating a rapid depletion of the resource. Conversely, in situations where reservoir energy is insufficient, the production rate begins at a lower level. Yet, this profile is notable for its ability to maintain a stable production plateau over an extended duration, lasting approximately 450 days. This observation draws a clear distinction between the two cases, highlighting how energy levels within the reservoir can drastically influence production profiles. Correspondingly, Fig. 5B presents pressure distribution maps that further elucidate these differences. The maps reveal that the effectively drained area in the high-energy scenario is considerably more confined compared to the other case. Notably, the effectively drained area is defined as the region where pressure drops below 80% of initial reservoir pressure. It is visualized via pressure contours in the simulation. This phenomenon can be primarily attributed to the larger stimulated fracture network in the insufficient energy scenario, which allows for a greater controlled reservoir volume. As a result, the coal matrix provides a more robust and sustained gas supply capacity, facilitating better long-term production stability. The simulation captures the key flow mechanisms: (1) initial displacement of water by free gas in the fracture network, (2) capillary-driven imbibition of water into the matrix, (3) pressure depletion triggering gas desorption from the matrix, and (4) diffusion of desorbed gas towards the fractures. The ‘effectively drained area’ visualized in Fig. 5B is the region where this coupled process has significantly reduced pressure, governing the long-term gas supply.

Moreover, the numerical simulation results indicate the presence of distinct productivity zones that align closely with the field performance analysis discussed in Section 2. This correlation not only reinforces the classification of deep CBM well production dynamics observed in the study area into these two distinct types but also underscores the scientific rigor and reliability of this analytical approach. Such findings are crucial for optimizing resource extraction strategies and informing future developments in the field.

Figure 5: Impact of reservoir energy on production performance of deep CBM wells: (A) Daily gas production and daily water production; (B) Pressure fields after 1000 Production days.

4 Flowback and Production Stage Division and Behavioral Patterns

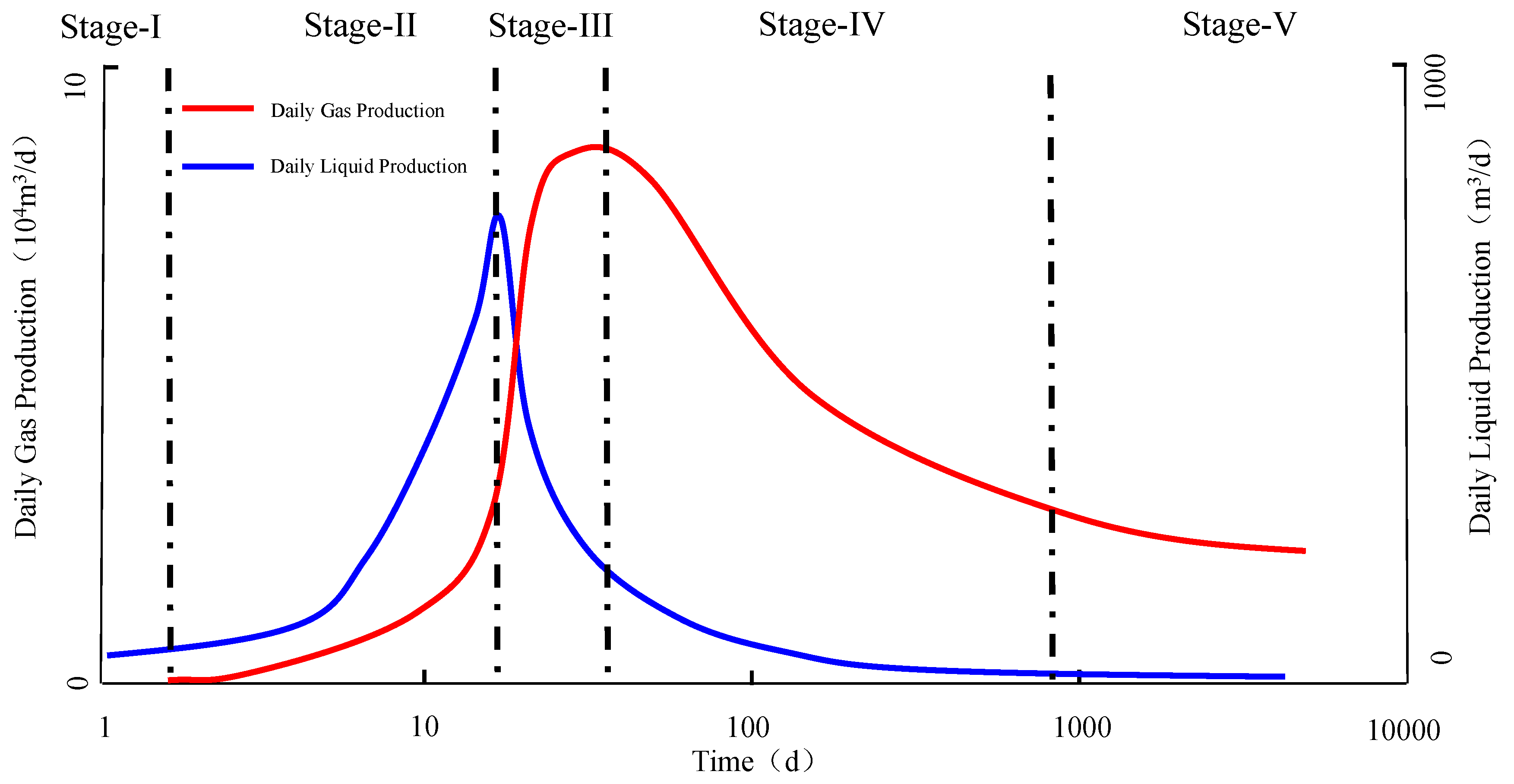

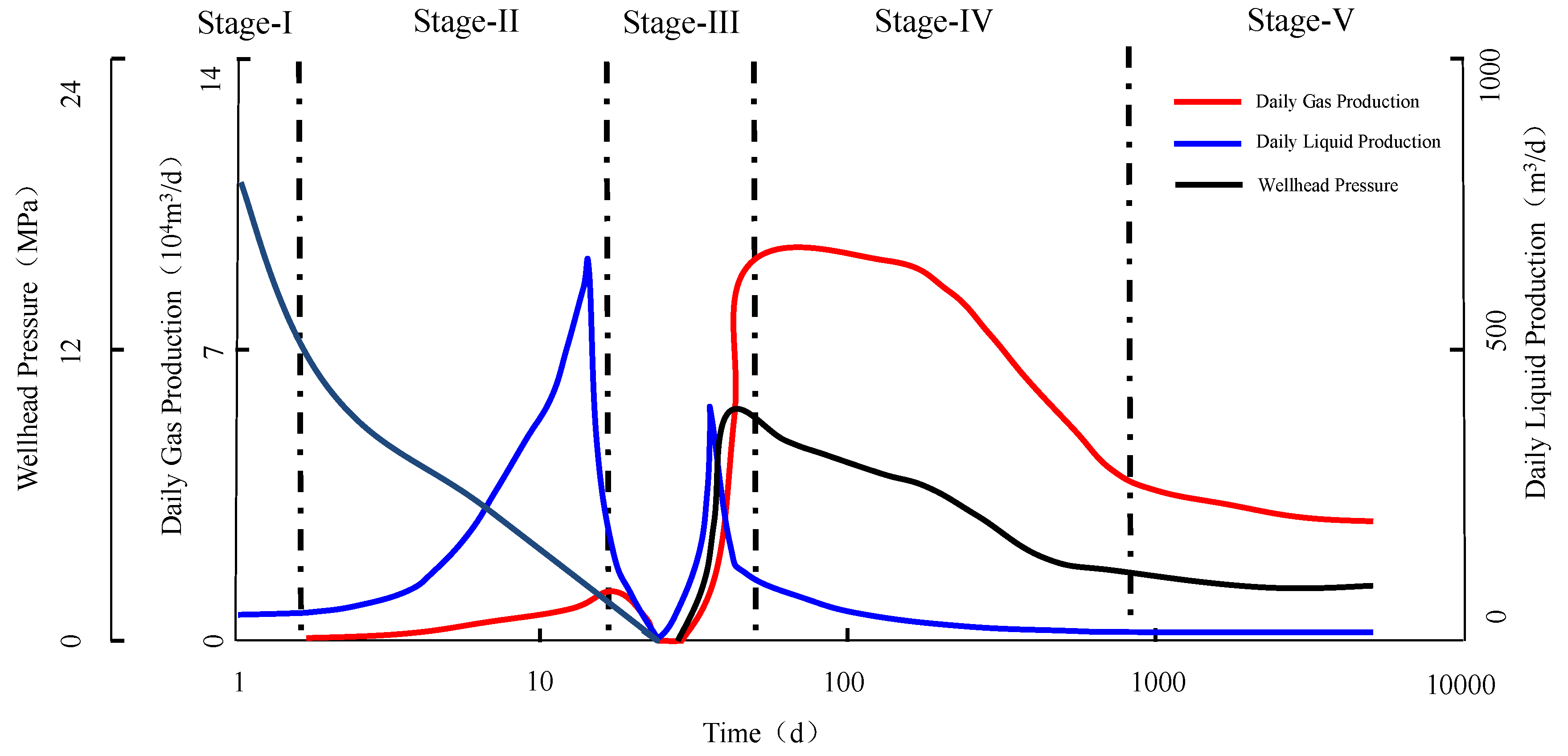

Based on the geological and engineering characteristics of deep coal reservoirs, guided by the gas-liquid two-phase flow theory for ultra-low permeability reservoirs, and referencing the flowback and production experience from 29 deep CBM horizontal wells in the study area, the flowback and production process of deep CBM horizontal wells is divided into five stages (Fig. 6). Building on this stage division, flowback and production parameters for these five stages across the 29 horizontal wells were statistically analyzed, clarifying the parameter variation patterns for each stage (see Table 3, Table 4 and Table 5).

- Stage I—Initial Single-Phase Dewatering Stage: The period from well opening for flowback until gas is first detected and ignited at the wellhead.

- Stage II—Initial Gas Appearance to Peak Water Production Stage: The period from sustained combustible gas flaring at the wellhead until the daily water production rate gradually increases to its peak.

- Stage III—Gas Breakthrough to Peak Gas Production Stage: The period where the daily gas production rate rapidly increases from a relatively low level to its peak, and the wellhead pressure gradually rises and stabilizes relatively.

- Stage IV—Stable Production and Decline Stage: The period where the daily gas production rate stabilizes at a relatively high level before slowly declining, and the wellhead pressure stabilizes relatively before slowly decreasing.

- Stage V—Low-Rate Production Stage: The period of stable production at a relatively low rate, with relatively low wellhead pressure.

Figure 6: Stage division for the production performance of deep CBM horizontal wells.

Table 3: Flowback and production stage parameters for Well JS6-7P01, Daning-Jixian Block.

| Production Stage | Duration (days) | Water Production (m3/d) | Gas Production (104 m3/d) | Flowback Recovery (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | End | Initial | End | |||

| Stage I | 1.9 | - | 253 | - | - | 0.5 |

| Stage II | 23 | 253 | 634 | - | - | 16.6 |

| Stage III | 8 | 634 | 221 | - | 10.2 | 22.9 |

| Stage IV | 407 | 221 | 5 | 10.2 | 2.3 | 44.6 |

| Stage V | - | 8 | - | 2.4 | - | - |

Table 4: Flowback and production stage parameters for Well JS14-5P02, Daning-Jixian Block.

| Production Stage | Duration (days) | Water Production (m3/d) | Gas Production (104 m3/d) | Flowback Recovery (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | End | Initial | End | |||

| Stage I | 0.4 | - | 217 | - | - | 0.1 |

| Stage II | 9 | 217 | 807 | - | - | 7.4 |

| Stage III | 95 | 807 | 43 | - | 13.6 | 28.1 |

| Stage IV | 309 | 43 | 2 | 13.6 | 2.9 | 35.1 |

| Stage V | - | 11 | - | 4.6 | - | - |

Table 5: Flowback and Production Stage Parameters for 29 Horizontal Wells, Daning-Jixian Block.

| Production Stage | Duration (days) | Water Production (m3/d) | Gas Production (104 m3/d) | Flowback Recovery (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initial | End | Initial | End | |||

| Stage I | 2 ± 0.2 | - | 140 ± 0.9 | - | - | 0.6 ± 0.1 |

| Stage II | 11 ± 0.8 | 140 ± 2.3 | 660 ± 18.3 | - | - | 10.7 ± 1.3 |

| Stage III | 17 ± 1.3 | 660 ± 9.2 | 136 ± 7.1 | - | 11.0 ± 0.5 | 28.4 ± 2.9 |

| Stage IV | 350 ± 8.3 | 136 ± 12.8 | 2.9 ± 1.2 | 11.0 ± 2.6 | 2.6 ± 0.7 | 39.5 ± 3.2 |

| Stage V | - | 10.3 ± 1.2 | - | 3.5 ± 0.6 | - | - |

4.2 Flowback Production Behavioral Patterns

In an analysis of the stage division and parameter evaluation for 29 deep coalbed methane (CBM) horizontal wells, the flowback production patterns across the five distinct stages were thoroughly clarified. This detailed examination highlighted several key aspects of the production process. Typically, deep CBM wells do not experience an extended shut-in period following hydraulic fracturing, and this is for two primary reasons. Firstly, a prolonged shut-in can lead to swelling of the clay minerals present within the coal reservoir. When these minerals come into contact with the fracturing fluid, they can expand and cause blockages in existing pores and fractures. This phenomenon is critical as it can significantly impair the reservoir’s permeability, ultimately leading to reduced gas production. Secondly, minimizing the shut-in period is crucial to prevent long-term retention of the fracturing fluid within the formation. If fracturing fluids remain in the reservoir for an extended duration, they can contribute to water blocking effects, which hinder gas flow by reducing the relative permeability of the formation to gas. Both of these factors underscore the importance of managing flowback strategies effectively in deep CBM operations to optimize overall production outcomes.

4.2.1 Stage I—Initial Single-Phase Dewatering Stage

This stage lasts from well opening until gas is first detected at the wellhead, with single-phase liquid flow in the wellbore. Due to the massive injection of fracturing fluid, the pressure within the induced fractures is significantly higher than the original reservoir pressure. Fracturing fluid in the main fractures can flow back rapidly due to this high pressure. The flowback liquid volume gradually increases during this stage, producing only liquid and no gas. Initially, due to the high-pressure differential, the flowback rate must be controlled to prevent proppant flowback or even transport back into the wellbore. Excessively rapid flowback can also cause the closure of distal fractures or loss of fracture conductivity, compromising the stimulation effectiveness. This stage typically employs a 2–3 mm choke to control flowback, lasts about 2 days, sees the daily liquid rate gradually rise to 140 m3, and ends with a flowback recovery of 0.6%.

4.2.2 Stage II—Initial Gas Appearance to Peak Water Production Stage

Gas begins to appear at the wellhead in this stage, transitioning the wellbore flow to a gas-liquid two-phase regime. As fracturing fluid from secondary fractures continuously converges into the main fractures, the flowback liquid volume increases further, reaching its peak. Simultaneously, as fracturing fluid continues to be produced, free gas in the coal reservoir migrates with the fluid and gradually gathers within the fractures. However, since the fracture pressure still exceeds the formation pressure at this stage, only a small amount of free gas—released from the coal matrix during fracturing—is produced with the fluid. The gas-liquid ratio remains relatively low (<0.01 × 104 m3/m3) due to the increasing liquid rate and minimal free gas production. This early two-phase flow regime, characterized by water dominance with minor gas, initiates the pressure depletion process that later evolves into the distinct drainage patterns shown in Fig. 5B.

Given the strong heterogeneity of coal reservoirs and variations in gas content, different fracture stages may have been stimulated to varying degrees even under identical operations. This heterogeneity leads to differing gas productivity per stage. Using too large a choke early in gas production can cause rapidly increasing gas production from the more productive stages, negatively impacting liquid and gas production from other stages and hindering overall well depressurization. Furthermore, because fracture pressure remains relatively high, a small choke is still required to control flowback and prevent fracture closure or loss of conductivity. Wellhead pressure continues to decline throughout this stage. At the end of this stage, wells with sufficient reservoir energy exhibit higher wellhead pressure than those with insufficient energy. This stage lasts about 11 days, sees the daily liquid rate rise to 660 m3, and ends with a flowback recovery of 10.7%.

4.2.3 Stage III—Gas Breakthrough to Peak Gas Production Stage

As fracturing fluid is continually produced, the overall pressure within the fracture network equalizes with the formation pressure. Free gas is produced continuously, increasing the gas saturation and decreasing the water saturation within the fractures, leading to a rapid rise in gas relative permeability. With substantial free gas production, the wellhead pressure begins to slowly rise. As the pressure within the fracture network drops further below the formation pressure, free gas is produced rapidly, adsorbed gas in the matrix begins to desorb slowly, the gas production rate increases sharply, the liquid production rate drops rapidly, the gas-liquid ratio increases swiftly and continuously, and the wellhead pressure rises rapidly to its peak. This stage lasts about 17 days, sees the gas rate climb rapidly to 11 × 104 m3/d, the daily liquid rate falls to 136 m3, the gas-liquid ratio rises to 0.1 × 104 m3/m3, and ends with a flowback recovery of 28.4%.

4.2.4 Stage IV—Stable Production and Decline Stage

Initially, wellhead pressure and daily gas rate are relatively stable. Notably, stable production in this work is defined as a period with <10% variation in daily gas rate over 30 consecutive days. As pressure within the fracture network continues to decrease, the reservoir pressure around the network slowly declines. Free gas continues to be produced in large quantities, and the volume of adsorbed gas desorbed per unit pressure drop increases slowly but steadily. The daily liquid rate drops rapidly to a low level and stabilizes. In the later part of this stage, due to the low permeability of the coal reservoir, gas migration from the matrix to the fractures encounters significant resistance and requires relatively long time. The volume of adsorbed gas desorbing in the low-pressure zone near the wellbore fractures is less than the reduction in free gas volume, coupled with insufficient supply from distal parts of the fracture network, leads to a production decline in the later part of this stage. Gas production in this late phase is predominantly from adsorbed gas, and the gas volume produced per unit pressure drop increases rapidly. As the gas rate decreases, artificial lift methods such as foam assisted lift may be needed to maintain production and prevent liquid loading. This stage has a relatively long duration. The initial stable gas rate is around 11 × 104 m3/d, declining later to a stable 3–4 × 104 m3/d. The liquid rate drops rapidly initially to 40–50 m3/d, then declines slowly later to 10–20 m3/d. The gas-liquid ratio ranges from 0.5 to 1.0 × 104 m3/m3.

4.2.5 Stage V—Low-Rate Production Stage

Wellhead pressure is relatively low in this stage. Formation pressure continues to decrease slowly and production is primarily from desorbed gas. The gas volume produced per unit pressure drop continues to increase. However, due to the slow decline in formation pressure, the gas production rate stabilizes at a low level. Since the production rate falls below the critical liquid-carrying rate, artificial lift is typically required to ensure continuous and stable well production.

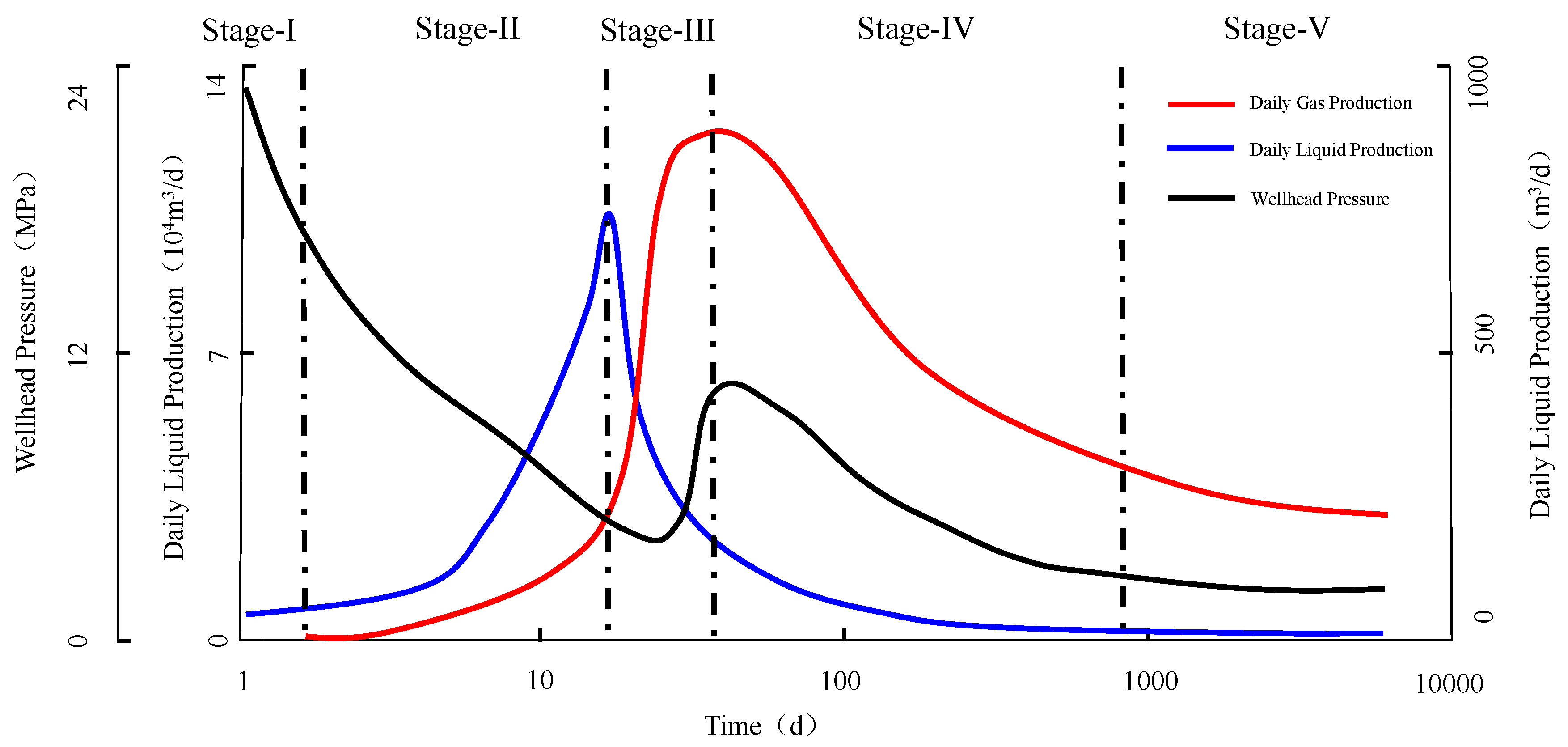

5 Standard Type Curves for Flowback Production of Deep CBM Horizontal Wells

Integrating theoretical analysis and insights from production practices, the 29 deep CBM horizontal wells in the Daning-Jixian Block were categorized into two types: those with Sufficient Reservoir Energy and those with Insufficient Reservoir Energy. This included 11 wells of the sufficient energy type and 18 wells of the insufficient energy type. Standard type curves for flowback production were established for each type respectively, which can guide field flowback and production operations.

5.1 Flowback Production Behavior of Horizontal Wells with Sufficient Reservoir Energy

For deep CBM horizontal wells with sufficient reservoir energy, flowback is initially controlled using a 2 mm choke. When the flowback rate and pressure stabilize, the choke size is gradually increased step-by-step until gas is consistently detected and flares sustainably at the wellhead. Upon entering the initial gas appearance stage, the wellbore flow regime transitions from single-phase liquid to gas-liquid two-phase flow, and wellhead pressure declines slowly. Flowback rate must still be controlled during this stage, and the choke should only be changed once the flowback rate and pressure have stabilized under the current size. When the wellhead pressure begins to rise slowly, the daily gas production rate increases rapidly. During this stage, the choke size should be adjusted promptly based on production rate and pressure. When wellhead pressure and daily gas rate stabilize, the choke size should be maintained, and the well can be switched to pipeline production. Wells with sufficient reservoir energy exhibit a relatively high initial gas production rate, reaching up to 120,000 m3/d. However, their production stability is relatively poorer. After a short high-rate stable production period of about 60 days, production enters a slow decline phase. In the later production stages, assisted deliquification techniques like foam lift and surface compressors are often required to ensure continuous and stable production. When the production rate falls below the critical liquid-carrying rate, artificial lift is implemented (Fig. 7). For wells with sufficient energy, rapid choke adjustment and early artificial lift are recommended.

Figure 7: Standard flowback production type curve for deep CBM horizontal wells with sufficient reservoir energy in the Daning-Jixian Block.

5.2 Flowback Production Behavior of Horizontal Wells with Insufficient Reservoir Energy

For deep CBM horizontal wells with insufficient reservoir energy, the wellhead pressure declines relatively rapidly during both the initial single-phase dewatering stage and the initial gas appearance to peak water production stage. After the daily water production rate peaks, the wellhead pressure drops to 0 MPa, and the daily water rate decreases swiftly. Due to the lack of reservoir energy, gas lift is typically employed during this phase to ensure continuous flowback, usually for a duration of about 42 h. Following this, the wellhead pressure begins to rise slowly, and the daily gas production rate increases rapidly. During this stage, the choke size should be adjusted promptly based on production and pressure to ensure stable wellhead pressure and gas rate, after which the well can be switched to pipeline production. Wells with insufficient reservoir energy have a lower initial gas production rate compared to the sufficient energy type, with a maximum stable gas rate of up to 80,000 m3/d. However, this well type exhibits relatively stronger production stability, maintaining stable production for over 130 days. The later production stages are managed similarly to wells with sufficient reservoir energy (Fig. 8). In comparison, sufficient-energy wells decline at ~15% per month after peak, while insufficient-energy wells maintain a plateau for >130 days with <5% monthly decline. For insufficient-energy wells, extended gas lift during early flowback and conservative choke management are advised to maintain stability.

Figure 8: Standard flowback production type curve for deep CBM horizontal wells with insufficient reservoir energy in the Daning-Jixian Block.

5.3 Application of the Standard Flowback Production Type Curves for Deep CBM Horizontal Wells

Notably, the standard type curves are statistical summaries derived from the production data of 29 wells, representing the characteristic behavior for each reservoir energy type. While precise numerical history matching for each well is challenged due to geological heterogeneity, the simulation results (Fig. 5) successfully reproduce the fundamental trends, suggesting that rapid initial production followed by decline in high-energy cases, and a lower but more stable plateau in low-energy cases, thus validating the conceptual model behind the type curves and aligning with field observations. In this section, the flowback and production operations for 53 deep coalbed methane (CBM) horizontal wells, part of the 1 BCM/a production capacity construction project in the study area, were conducted in accordance with the previously mentioned standard type curves. Of these wells, 36 exhibited sufficient reservoir energy, while 17 had insufficient energy. The characteristics observed at various stages across the different well types demonstrated a strong alignment with the standard type curves. Currently, all 53 horizontal wells have reached the stable production phase. The average stabilized gas production rate per well is 75,000 m3/d. Specifically, the wells with sufficient energy are stabilizing at a production rate of 80,000 m3/d, whereas those with insufficient energy are stabilizing at 70,000 m3/d, both showing favorable production performance. Production practices have indicated that these standard type curves effectively guide the development of deep CBM horizontal wells in the Daning-Jixian Block. Therefore, they can be recommended for broader application in deep CBM development within the region.

This research presents the first systematic framework for understanding the post-fracturing flowback behavior of deep CBM horizontal wells. By integrating gas-liquid two-phase flow theory with field data from 29 wells, it establishes a novel five-stage division of the production process. Crucially, the study introduces two reservoir-energy-based standard type curves ("Sufficient" and "Insufficient"), validated by numerical simulation, which explain distinct production stability patterns linked to effectively drained areas. This original classification provides practical guidance for choke management and artificial lift timing, successfully applied to 53 wells, filling a critical knowledge gap in deep CBM development.

- (1)The geological characteristics of the Daning-Jixian Block, including higher thermal maturity, less developed natural fractures and greater gas content in the north, create a fundamental dichotomy in reservoir energy. This dichotomy is the root cause of the two distinct production behavioral types observed, forming the basis for the subsequent classification for production type curves.

- (2)The flowback and production process of deep CBM wells consists of five distinct stages. Initially, gas production originates primarily from free gas until the peak gas rate is reached. During the subsequent stable production phase, both free gas and adsorbed gas contribute to output, while later stages are increasingly supported by adsorbed gas as production declines and enters low-rate phases.

- (3)Wells with sufficient reservoir energy generally experience immediate high and stable production upon commissioning, followed by a gradual decline after an initial phase of consistent output. In contrast, wells with limited reservoir energy require a ramp-up period to achieve high production rates, which, although generally lower than their sufficiently energized counterparts, can be sustained for longer durations. Numerical simulation corroborates these field observations, demonstrating that the larger effectively stimulated volume in insufficient-energy scenarios leads to a broader pressure depletion and a more stable gas supply from the coal matrix.

- (4)Two standardized type curves for the flowback production of deep CBM horizontal wells have been established based on reservoir energy classification. These curves provide practical guidance for flowback choke management, artificial lift timing, and production forecasting. Their successful application in guiding the production strategies of 53 wells highlights their significant potential for broader application within the field.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: The research was supported by the National Science and Technology Major Project of China (No. 2025ZD1405702), and the Scientific Research and Technology Development Project of PetroChina Coalbed Methane Co., Ltd. (Project No. 25MQCTSG010), and Applied Science and Technology Project of PetroChina Company Limited (2023ZZ18YJ04).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization, Wei Sun, Yanqing Feng, and Yuan Wang; methodology, Wei Sun, Yanqing Feng, and Zengping Zhao; validation, Wei Sun, and Qian Wang; formal analysis, Yanqing Feng, and Xiangyun Li; investigation, Wei Sun, Yanqing Feng, and Xiangyun Li; resources, Yuan Wang; data curation, Qian Wang; writing—original draft preparation, Wei Sun, and Yanqing Feng; writing—review and editing, Dong Feng, and Yuan Wang. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Xu FY , Yan X , Lin ZP , Li SG , Xiong XY , Yan DT , et al. Research progress and development direction of key technologies for efficient coalbed methane development in China. Coal Geol Explor. 2022; 50( 3): 1– 14. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Zhao L , Yang H , Wei Y , Bu Y , Jing S , Zhou P . Integrity and failure analysis of cement sheath subjected to coalbed methane fracturing. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2023; 19( 2): 329– 44. doi:10.32604/fdmp.2022.020216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Yang F , Mi H , Wu J , Yang Q . Factors influencing proppant transportation and hydraulic fracture conductivity in deep coal methane reservoirs. Fluid Dyn Mater Process. 2024; 20( 11): 2637– 56. doi:10.32604/fdmp.2024.048574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mohamed T , Mehana M . Coalbed methane characterization and modeling: review and outlook. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util Environ Eff. 2025; 47( 1): 2874– 96. doi:10.1080/15567036.2020.1845877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Nie ZH , Shi XS , Sun W , Yan X , Huang HX , Liu Y , et al. Production characteristics of deep coalbed methane gas reservoirs in Daning-Jixian Block and its development technology countermeasures. Coal Geol Explor. 2022; 50( 3): 193– 200. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

6. Sharma R , Singh S , Anand S , Kumar R . A review of coal bed methane production techniques and prospects in India. Mater Today Proc. 2024; 99: 177– 84. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2023.08.150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Clarkson CR , Bustin RM . Coalbed methane: current evaluation methods, future technical challenges. In: Proceedings of the SPE Unconventional Gas Conference; 2010 Feb 23–25; Pittsburgh, PA, USA. doi:10.2523/131791-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Prabu V , Mallick N . Coalbed methane with CO2 sequestration: an emerging clean coal technology in India. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015; 50: 229– 44. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.05.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Park SY , Liang Y . Biogenic methane production from coal: a review on recent research and development on microbially enhanced coalbed methane (MECBM). Fuel. 2016; 166: 258– 67. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2015.10.121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fan C , Yang L , Sun H , Luo M , Zhou L , Yang Z , et al. Recent advances and perspectives of CO2-enhanced coalbed methane: experimental, modeling, and technological development. Energy Fuels. 2023; 37( 5): 3371– 412. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c03823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Freij-Ayoub R . Opportunities and challenges to coal bed methane production in Australia. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2012; 88: 1– 4. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2012.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Li S , Qin Y , Tang D , Shen J , Wang J , Chen S . A comprehensive review of deep coalbed methane and recent developments in China. Int J Coal Geol. 2023; 279: 104369. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2023.104369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Blasingame TA . The characteristic flow behavior of low-permeability reservoir systems. In: Proceedings of the SPE Unconventional Reservoirs Conference; 2008 Feb 10–12; Keystone, CO, USA. doi:10.2118/114168-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zhou J , Fu T , Wu K , Zhao Y , Feng L . Optimization design of multi-gathering mode for the surface system in coalbed methane field. Petroleum. 2023; 9( 2): 237– 47. doi:10.1016/j.petlm.2022.01.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Kędzior S . The occurrence of coalbed methane in the depocentre of the Upper Silesian Coal Basin in the light of the research from the Orzesze-1 deep exploratory well. Int J Coal Geol. 2024; 292: 104588. doi:10.1016/j.coal.2024.104588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Han S , Sang S , Zhang J , Xiang W , Xu A . Assessment of CO2 geological storage capacity based on adsorption isothermal experiments at various temperatures: a case study of No. 3 coal in the Qinshui Basin. Petroleum. 2023; 9( 2): 274– 84. doi:10.1016/j.petlm.2022.04.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Sarhosis V , Jaya AA , Thomas HR . Economic modelling for coal bed methane production and electricity generation from deep virgin coal seams. Energy. 2016; 107: 580– 94. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2016.04.056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. He Y , Wang J , Huang X , Du Y , Li X , Zha W , et al. Investigation of low water recovery based on gas-water two-phase low-velocity Non-Darcy flow model for hydraulically fractured horizontal wells in shale. Petroleum. 2023; 9( 3): 364– 72. doi:10.1016/j.petlm.2022.03.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Sun Z , Shi J , Wu K , Zhang T , Feng D , Li X . Effect of pressure-propagation behavior on production performance: implication for advancing low-permeability coalbed-methane recovery. SPE J. 2019; 24( 2): 681– 97. doi:10.2118/194021-PA. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wen S , Wei B , You J , He Y , Xin J , Varfolomeev MA . Forecasting oil production in unconventional reservoirs using long short term memory network coupled support vector regression method: a case study. Petroleum. 2023; 9( 4): 647– 57. doi:10.1016/j.petlm.2023.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Olajossy A , Cieślik J . Why coal bed methane (CBM) production in some basins is difficult. Energies. 2019; 12( 15): 2918. doi:10.3390/en12152918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Salmachi A , Clarkson C , Zhu S , Barkla JA . Relative permeability curve shapes in coalbed methane reservoirs. In: Proceedings of the SPE Asia Pacific Oil and Gas Conference and Exhibition; 2018 Oct 23–25; Brisbane, Australia. doi:10.2118/192029-MS. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kholod N , Evans M , Pilcher RC , Roshchanka V , Ruiz F , Coté M , et al. Global methane emissions from coal mining to continue growing even with declining coal production. J Clean Prod. 2020; 256: 120489. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Sun Z , Huang B , Liu Y , Jiang Y , Zhang Z , Hou M , et al. Gas-phase production equation for CBM reservoirs: interaction between hydraulic fracturing and coal orthotropic feature. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2022; 213: 110428. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. CMG (Computer Modelling Group). GEM user’s guide. Calgary, AB, Canada: Computer Modelling Group Ltd.; 2023. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools