Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Hypersonic Flow over V-Shaped Leading Edges: A Review of Shock Interactions and Aerodynamic Loads

1 School of Nuclear Science, Energy and Power Engineering, Shandong University, Jinan, China

2 Shenzhen Research Institute, Shandong University, Shenzhen, China

3 School of Aeronautic Science and Engineering, Beihang University, Beijing, China

* Corresponding Author: Jingying Wang. Email:

Fluid Dynamics & Materials Processing 2026, 22(1), 2 https://doi.org/10.32604/fdmp.2026.076238

Received 17 November 2025; Accepted 09 January 2026; Issue published 06 February 2026

Abstract

For hypersonic air-breathing vehicles, the V-shaped leading edges (VSLEs) of supersonic combustion ramjet (scramjet) inlets experience complex shock interactions and intense aerodynamic loads. This paper provides a comprehensive review of flow characteristics at the crotch of VSLEs, with particular focus on the transition of shock interaction types and the variation of wall heat flux under different freestream Mach numbers and geometric configurations. The mechanisms governing shock transition, unsteady oscillations, hysteresis, and three-dimensional effects in VSLE flows are first examined. Subsequently, thermal protection strategies aimed at mitigating extreme heating loads are reviewed, emphasizing their relevance to practical engineering applications. Special attention is given to recent studies addressing thermochemical nonequilibrium effects on VSLE shock interactions, and the limitations of current research are critically assessed. Finally, perspectives for future investigations into hypersonic VSLE shock interactions are outlined, highlighting opportunities for advancing design and thermal management strategies.Keywords

Over more than a century, the flight of humans has advanced through subsonic, transonic, supersonic, and into hypersonic regimes. Hypersonic vehicles, owing to their extremely high speeds and difficulty in detection and interception, enable rapid global strike with missiles and single-stage-to-orbit space transportation. They are regarded as an important part of aerospace progress in the 21st century [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Hypersonic air-breathing vehicles powered by a supersonic combustion ramjet (scramjet) engine have become a focal point of current research, distinguished from other hypersonic vehicles by their sustained operation and economic efficiency [7].

Hypersonic air-breathing vehicles, which utilize atmospheric oxygen, offer advantages of compact configuration, high speed, maneuverability, strong penetration capability, and high accuracy [8]. As the core propulsion system of such vehicles, the scramjet requires supersonic combustion within the engine [9]. Due to the high inflow velocity, the residence time of fuel inside the combustor is extremely short, necessitating the rapid completion of fuel injection, atomization, evaporation, mixing, ignition, and stabilization within a limited timescale [7,9,10]. The inlet plays a decisive role by decelerating and compressing the high-speed inflow, thereby enabling efficient energy conversion while minimizing pressure losses.

In recent years, three-dimensional inward-turning inlets designed using streamline tracing methods have emerged as a preferred configuration for hypersonic air-breathing vehicles, owing to their compact structure, high compression efficiency, strong mass capture capability, high total pressure recovery, and ease of integration [11]. As a key component of the scramjet, the inlet is influenced by the flow characteristics near its cowl lip, which directly affect the overall propulsion efficiency and flight performance of the vehicle [12]. As shown in Fig. 1, the cowl lip is idealized as the V-shaped leading edges (VSLEs) [13,14,15], characterized by complex shock interactions and severe aerodynamic heating loads, which threaten the structural integrity and flight stability of the vehicle, presenting significant challenges for its development. Therefore, clarifying the mechanisms of shock interaction at the VSLEs and their influence on wall aerodynamic heating loads is vital for the realization of reliable and efficient flight control in hypersonic vehicles [16].

Figure 1: VSLE structure of a scramjet inlet lip [17].

2 Shock Interactions and Flow Characteristics

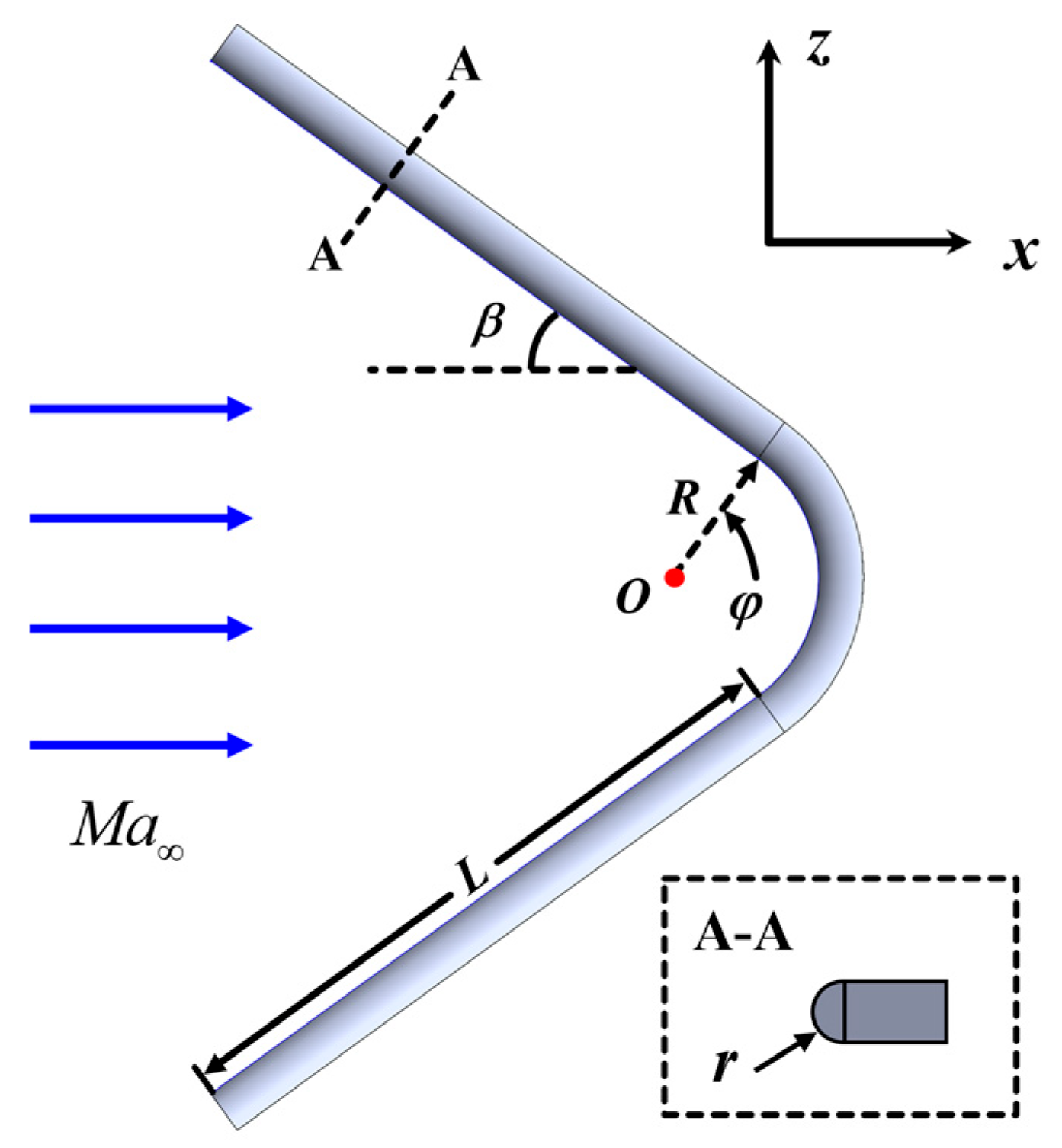

Xiao et al. [18,19] first proposed the VSLEs, which consist of two swept leading edges and a round crotch, based on the inlet lip of an air-breathing scramjet. The geometric model is shown in Fig. 2. The configuration is characterized by four primary parameters: the span angle (β), the curvature radius of the crotch (R), the leading-edge bluntness radius (r), and the length of the straight branch (L). The geometry is symmetric about the x-y and x-z planes, where x, y, and z represent the streamwise, overflow, and spanwise directions, respectively, and θ denotes the circumferential direction around the crotch [19]. The VSLE exhibits quasi-two-dimensional characteristics in the x-z plane, showing the primary shock structures of the flow. Consequently, many analyses are conducted on the shock interaction and the surface aerothermal characteristics based on the x-z symmetry plane [19,20,21,22,23].

Figure 2: VSLE structure of a scramjet inlet lip.

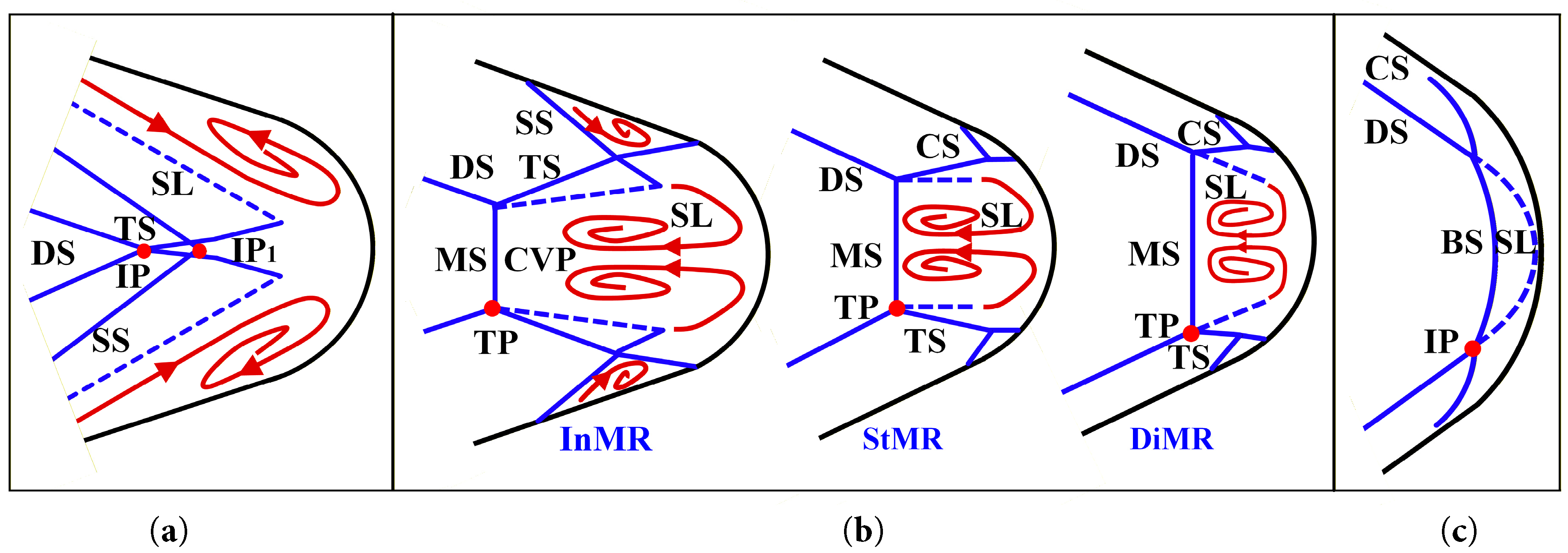

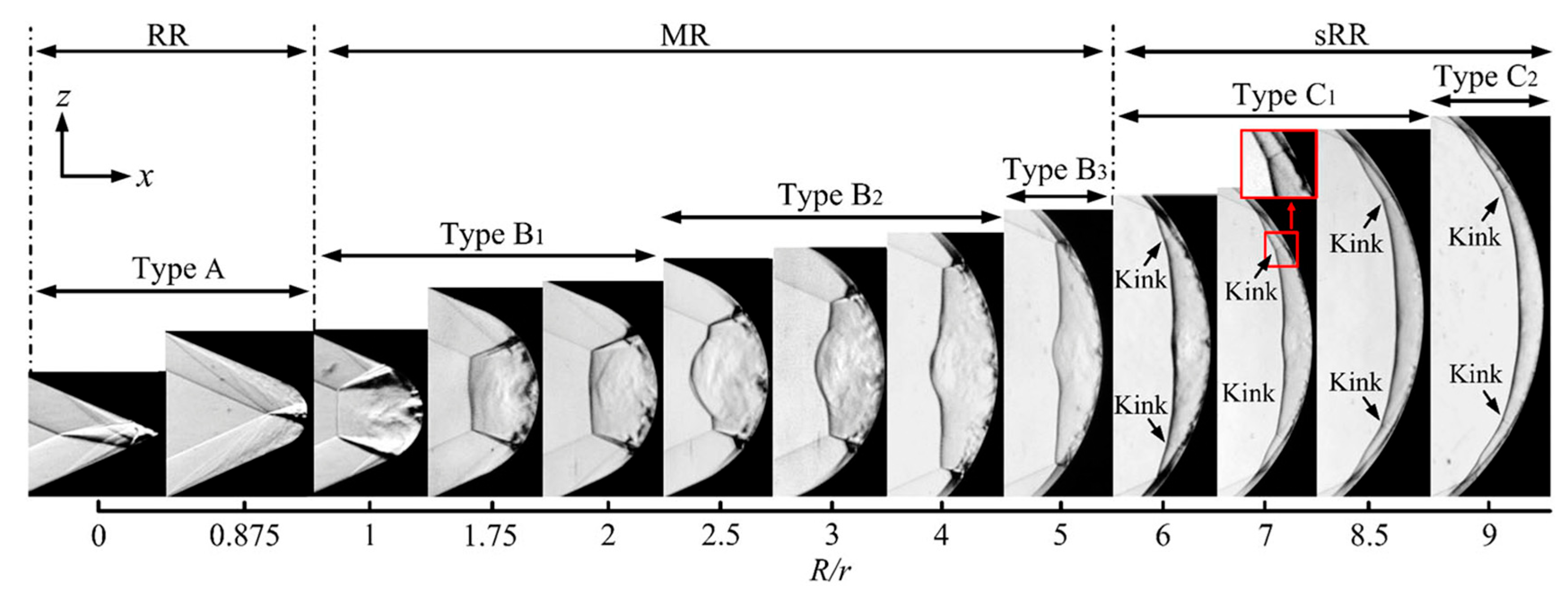

As shown in Fig. 3, the flow at the crotch of VSLEs primarily exhibits three types of shock interactions: regular reflection (RR), Mach reflection (MR), and regular reflection from the same family (sRR) [18]. Under the steady flow, MR can be further classified: when the shear layer deviates from the centerline and forms diverging stream tube, the inverse Mach reflection (InMR) occurs; when the shear layer parallels the centerline, the stationary Mach reflection (StMR) occurs; when the shear layer forms a covering stream tube, the direct Mach reflection (DiMR) occurs [24]. The detached shock (DS) generated by the VSLE can be recognized as the incident shock, while the Mach stem (MS) or Bow shock (BS) at the crotch acts as the bow shock. The resulting shock interaction resembles the Type IV shock interaction proposed by Edney [25]. Unlike conventional Type IV shock interactions, the jet does not directly impinge on the wall, and the vortex shedding induced by jet instability does not lead to flow spillage in the incoming direction [19].

Figure 3: Types of shock interaction: (a) RR; (b) MR; (c) sRR.

When the shock interaction corresponds to RR, the DS generated by the straight branch directly impinges on the interaction point (IP) upstream of the crotch stagnation point, producing a transmitted shock (TS) on the surface. The combined effects of TS impingement and the local surface contraction near the crotch significantly enlarge the separation zone, inducing boundary-layer separation and forming a separation shock (SS). Consequently, the nominal intersection point IP1 of the SS shifts toward the primary interaction point IP. Since the downstream subsonic region does not influence the IP, the RR configuration of the DS can be maintained.

For MR, the DS generated from the opposite positions of the straight branch interacts with the MS in front of the crotch, forming TS and shear layers (SL) in triple points (TP). The first scenario corresponds to the case in which the TS impinges on the straight branch, generating the SS, and the SS subsequently interacts with the incident TS. The other scenario is that the junctions between the crotch and the straight branch are exposed to upstream supersonic flow. The compression of the curved crotch generates a series of compression waves (CWs), which are superimposed to form compression shocks (CS). Near the wall, the TS and CS undergo secondary regular reflection, generating the transmitted shock, which impinges on the wall and triggers a shock-boundary layer interaction (SBLI), which leads to the formation of the outmost surface heat flux peak. The supersonic jets on the opposite sides converge at the stagnation point, forming the central heat flux peak.

In contrast to the MR, the CS induced by the crotch directly intersects with the DS generated by the straight branch at the intersection point (IP). The TP caused by the BS originating from the crotch intersecting with the DS to form TS and SL also occurs at this point. TS impinges on the wall and triggers the SBLI, which causes the outmost wall heat flux peak. The collisions of supersonic jets at the stagnation point result in the formation of the central heat flux peak.

Current research on V-shaped leading edges has primarily concentrated on low Mach number, addressing shock structures and interactions [18,19,20,21,22,23,26,27,28,29], transition correlations [21,24,30,31,32], aerodynamic heating loads [19,20,21,22,23,29,30], and unsteady oscillations [23,26]. Studies have shown that the complex shock interactions near the crotch of the VSLEs produce localized wall regions of elevated pressure and heat flux, which can significantly shorten the operational lifetime of the inlet lip [19,20,29]. Geometric parameters and Mach number influence the shock interaction at the crotch, which in turn affects the wall aerothermal characteristics [24,29,30]. Competition between the opposite jets near the stagnation point and the pulsating motion of the crotch induce unsteady oscillations, leading to periodic fatigue of the inlet lip [23,26]. In addition, the complex shock interaction also affects the downstream flow field [27,28,31].

Based on numerical simulations and wind tunnel experiments, theoretical transition boundaries formulations of shock interaction and correlations for predicting peak wall-centerline heat flux have been proposed [29,30,32]. Given the comparability between wall heat flux and pressure in classical shock interactions, the peak heat flux at different locations exhibits an exponential relationship with the corresponding pressure peaks [33]. For engineering design, the wall heat flux can be estimated through the relatively accessible wall pressure [34].

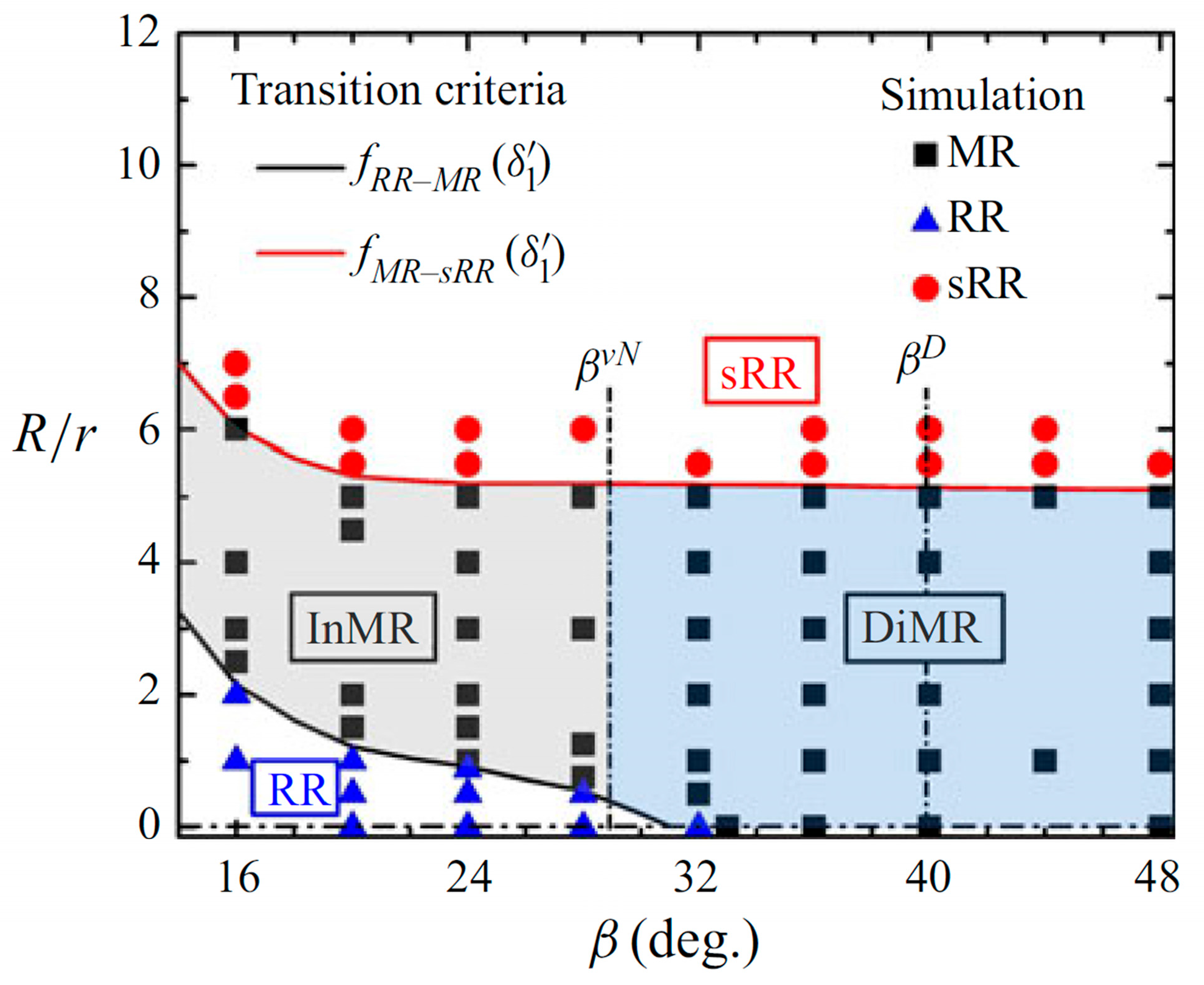

The type of shock interaction for the VSLEs is governed by the freestream Mach numbers and geometric parameters (β and R/r) [35]. Under the same Ma and β conditions, R/r alters the accommodation and relief space for the supersonic flow at the crotch region and the impingement location of the TS on the wall, affecting the type of shock interaction. Under identical Ma and R/r conditions, β influences the shock interaction by modifying the DS strength and its standoff distance [30]. With the geometric parameters fixed, the freestream Ma number affects the shock interaction by altering the DS standoff distance and the strength of the post-shock supersonic flow. Accordingly, the criterion for shock interaction transition can be summarized as follows: when the IP consisting of the DS coincides with the IP1 of the SS, the type shifts from RR to MR; when the CS directly interacts with the DS, the type transitions from MR to sRR [30,35]. Following the proposed transition criterion, the dependence of shock interaction on geometric parameters at Ma = 6 was established, and the corresponding transition boundaries were determined. Fig. 4 illustrates that the theoretical boundary (solid line) agrees well with the numerical simulations, confirming the validity of the theoretical formulation [24,29,35].

Figure 4: Shock interaction transition boundaries at Mach 6 [24].

According to Fig. 4, the shock interaction types of VSLEs exhibit a systematic dependence on the R/r and β. RR is confined to a relatively narrow region, whereas MR dominates a broad portion of the parameter space and extends beyond the classical von Neumann and detachment boundaries. Nevertheless, the MR subtypes can still be identified using conventional transition criteria. sRR occurs only at sufficiently large R/r, and its transition boundary becomes nearly horizontal over an extended range of β, indicating that the shock interaction is more sensitive to R/r than to β. Consequently, adjusting the R/r constitutes one of the most effective design parameters for controlling shock interaction type in VSLEs.

Studies have demonstrated that shock interactions of VSLEs exhibit bistability between RR and InMR below the von Neumann boundary, accompanied by a pronounced hysteresis. Numerical results indicate that as the freestream Ma number increases from 4.3 to 4.4, the shock interaction remains in the RR. With a further increase to Ma number 4.5, the DS detachment distance decreases, triggering a transition from RR to InMR. During subsequent Ma number reduction, the InMR configuration remains stable at Mach 4.4, whereas a reverse transition to RR occurs at Ma number 4.3. Hysteresis leads to flow bistability and a loss of flowfield uniqueness, giving rise to distinct flow structures and pronounced variations in wall pressure and aerothermal loads that cannot be adequately captured by classical shock interaction theories. From a propulsion perspective, hysteresis causes a mismatch between the inlet start condition and the post-unstart restart condition, invalidating traditional start criteria based on static boundaries and significantly increasing the complexity of inlet design and operational control. Consequently, a thorough understanding of hysteresis effects is critical for improving inlet stability, developing robust control strategies, and ensuring aerothermal safety in hypersonic vehicle applications [36,37].

The classification of shock interaction discussed above was based on the time-averaged flow field, without accounting for secondary shock interactions or the unsteady oscillations of the shock structures. To reveal the transition mechanism of flow oscillation, Fig. 5 refines the shock interaction into six subcategories [29], based on the interaction of jet and vortex structures with the primary shock. This provides a more comprehensive description of the shock interaction type. As illustrated in Fig. 5, the evolution of the shock interaction type of VSLEs occurs as the R/r increases. For small R/r, the flow exhibits RR, corresponding to Type A. As R/r increases, the shock interaction transitions into MR. These MR regimes manifest sequentially as Type B1, B2, and B3, each characterized by a different type of unsteady oscillation. The most evident manifestation is the deformation of MS. When R/r exceeds a certain value, the shock interaction turns to sRR. The crotch provides additional buffer space for the supersonic jet, thereby reducing the jet intensity near the stagnation region. As a result, the MR is transformed into a BS. In this regime, two distinct patterns, Type C1 and C2, emerge. Both are marked by pronounced kink points, which become increasingly evident as R/r grows. The distinction between Type C1 and C2 lies in whether the BS is influenced by the jet emanating from the stagnation region.

The VSLEs flowfield involves multiple sources of flow instability, including shock/boundary layer interaction, flow separation, jet, and counter-rotating vortex pairs, which collectively render the shock interaction inherently unsteady. Wang revealed the unsteady oscillatory behavior of shock interactions through large-eddy simulations (LES) and wind-tunnel experiments. Subsequently, Zhang et al. investigated the evolution of unsteady oscillation characteristics with increasing R/r using high-speed schlieren imaging coupled with image-processing techniques. Their results indicate that distinct shock interactions are associated with different oscillation modes. The origin of shock oscillations can be attributed to jet collision and competition near the stagnation region, together with the breathing motion of the supersonic flow at the crotch [23]. Representative shock oscillations include global oscillation of the MS, arching-recovery motion of the MS, and their combined forms [26,38]. In addition, the self-sustained oscillation of the primary shock structure induces pronounced unsteady wall loads, which are jointly driven by mid-frequency oscillations associated with jet and high-frequency disturbances resulting from shear-layer instability near the crotch. The locations of peak pressure fluctuations are strongly dependent on the shock-interaction type, and the fluctuation amplitude increases with model scale [39]. Existing studies demonstrate that increasing the R/r can effectively suppress shock oscillations, thereby reducing wall pressure fluctuations. Under hypersonic conditions, pressure fluctuations in the inlet-lip region can significantly enhance local aero-thermal load oscillations and induce structural fatigue, while simultaneously degrading inlet flow stability and total-pressure recovery. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the underlying mechanisms is essential for the design of hypersonic inlets.

Figure 5: Types of shock interference in unsteady conditions [23].

The complex flow structures of the VSLEs, such as supersonic jets and opposite vortex, propagate downstream and affect the uniformity and performance of the downstream flow, indicating that the shock interaction exhibits three-dimensional effects [28]. The presence of three-dimensional effects causes flow separation, shock sweeping, and jet collisions, which create high-pressure regions in the downstream flow and alter the characteristics of the induced pressure distribution [39]. The streamwise blockage, normal overflow, and spanwise contraction of the VSLEs induce the transition of shock interaction, thereby affecting lateral flow. Under the sRR condition, the straight leading edge generates lateral flow converging toward the spanwise symmetry plane, enhancing the convergence of the shear layer into the streamwise vortex pairs and extending it downstream [27,28].

Previous studies indicate that increasing R/r leads to an expansion of the low total pressure recovery region induced by shock interactions, accompanied by an overall reduction in the total pressure recovery coefficient, thereby exacerbating the degradation of downstream flow uniformity. Meanwhile, the three-dimensional flowfield generated by the VSLEs exhibits a certain self-similarity in the downstream region, providing a basis for scaling analyses across different geometric configurations. Overall, three-dimensional effects not only modify the total pressure recovery distribution and flow uniformity but also exert a direct impact on inlet-engine matching and the performance of air-breathing hypersonic engines. Furthermore, the pronounced three-dimensionality of the VSLEs, together with the geometric confinement imposed by quasi-axisymmetric internal compression configurations, poses new challenges to existing theoretical frameworks for shock interaction. Therefore, in hypersonic aerodynamic layout and inlet system design, more CFD investigations and experimental validations are required to assess the influence of three-dimensional shock interactions on downstream flow characteristics.

3 Thermal Protection Strategies

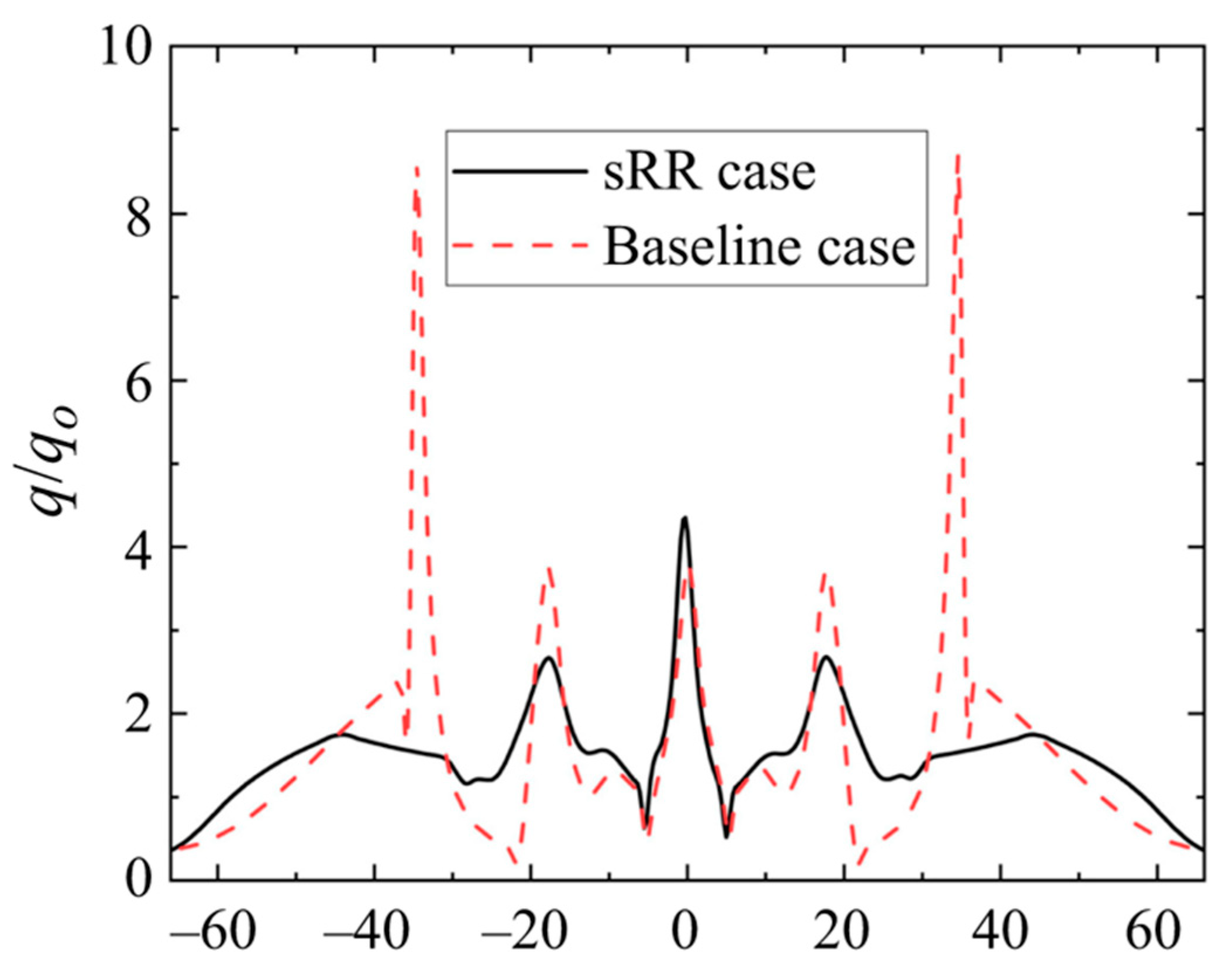

As shown in Fig. 6, at the crotch of the VSLEs, the complex shock structures result in extremely high local aerodynamic heating, reaching up to 24 times the Fay-Riddell prediction [19]. This markedly increases the difficulty of accurately predicting wall aerodynamic characteristics and poses challenges for thermal protection. The peak heat fluxes along the wall centerline of the VSLEs can be categorized into three types: the outermost peak, the central peak, and the innermost peak. These peak heat fluxes arise from distinct mechanisms, and the innermost peak is lower than the central and outermost peaks [30]. The mechanisms leading to the peak surface heat flux at VSLEs primarily include the impingement of supersonic flow on the wall, shock or expansion wave/boundary layer interactions, attachment of shear layers to the wall, and the collisions of supersonic jets [21].

Figure 6: Distribution of the wall heat flux [40].

Given the severe aerothermal loads on the VSLEs, the classical blunt-body thermal protection theory proposed by Allen [41,42] does not reduce the heat flux. It may even exacerbate it [13,19]. Distinguished from traditional aerodynamic configurations, the VSLEs require sufficient sharpness to resist complex shock interaction, while retaining certain bluntness to alleviate wall heat loads [19]. Research has demonstrated that altering the span angle provides limited improvement in reducing the surface heat flux, and that the range of the crotch radius strongly constrains the sensitivity of heat flux to the bluntness radius ratio [43]. The swept leading edges have sufficient thermal protection ability, but shock interaction at the crotch elevates wall heat loads. In conclusion, it is necessary to study the shock interaction and wall aerodynamic loads distributions of the VSLEs [34].

Shock interactions at VSLEs cause many negative effects, making aerodynamic optimization crucial for controlling these interactions. To reduce the extreme wall loads caused by shock interactions, various thermal protection and aerodynamic strategies have been proposed. Increasing R/r transitions the flowfield to sRR, significantly lowering wall loads and suppressing shock oscillations [34]. Since engineering applications limit modifications to the VSLEs geometry, efficient methods are needed to decrease aerodynamic heating of the walls. Using streamline-tracing design with inward-turning inlets, the VSLEs centerline can be shaped as elliptical, hyperbolic, or parabolic [22]. Straight branches provide strong resistance to thermal loads, allowing the blunt section to be shaped elliptically. Adjusting the ellipse’s aspect ratio enables control over the shock interactions [44]. The most intense wall loads for VSLEs occur at the crotch. Changing the blunt radius of the straight branches and the crotch helps control shock interactions effectively [45]. Local shock control bumps are placed along the centerline where peak wall heat flux and pressure occur to reduce aerodynamic heating loads [32]. To manage the powerful supersonic jet at the stagnation point, an opposite jet control strategy is used to lower local wall loads [46]. However, the small bluntness of VSLEs at the inlet lip, the installation of shock control bumps, and the use of opposing jets present practical challenges for engineering applications.

At present, multiple aerodynamic and thermal protection strategies have been proposed to mitigate the extreme wall aerodynamic heating loads at the crotch of VSLEs. These include increasing the R/r [30], using high eccentricity conic crotch [22,44], adapting shock control bump (SCB) [32], elliptic cross-section [47], nonuniform blunt-ness [45], opposing jets [46], and shock control interaction structure [40].

4 Thermochemical Nonequilibrium Effects

Although significant progress has been made in the fundamental mechanisms of shock interactions, most existing studies remain confined to relatively low freestream Mach numbers and rely on the calorically perfect gas assumption [48,49,50,51]. Under such conditions, the thermodynamic behavior of the flow is comparatively simple, and the resulting conclusions cannot be directly extrapolated to high-enthalpy conditions. For hypersonic flows with freestream Mach numbers above 5, the calorically perfect gas model is no longer adequate to represent the underlying physicochemical processes [51,52,53]. Consequently, it is necessary to investigate shock interactions within a more realistic high-enthalpy physical framework to achieve a comprehensive understanding of their evolution and to establish a reliable basis for aerodynamic heating predictions in advanced hypersonic propulsion systems [53,54].

Thermochemical nonequilibrium effects play a critical role in shaping the aerothermal environment and overall vehicle design under high-enthalpy conditions [55,56]. Interactions between the thermochemical nonequilibrium flow and thermal protection materials can induce complex surface phenomena, including catalysis [57,58], oxidation, and ablation-driven pyrolysis [59,60], which significantly alter wall heat flux and aerodynamic characteristics [61]. These effects directly impact the lifetime and safety margins of thermal protection systems, as well as vehicle stability, lift-to-drag performance, and thrust assessment [61,62,63,64]. Furthermore, ionization nonequilibrium leads to nonuniform electron density distributions that affect electromagnetic wave propagation, causing a communication blackout [65,66,67]. Variations in energy-mode and species concentrations under multi-temperature conditions also modify radiative properties and radiative heat transfer, thereby increasing uncertainty in aerothermal predictions [68]. Therefore, accurate modeling of thermochemical nonequilibrium effects is essential for achieving high-fidelity aerothermal analyses, improving thermal protection system design, and enhancing the overall performance and reliability of hypersonic vehicles [61,62].

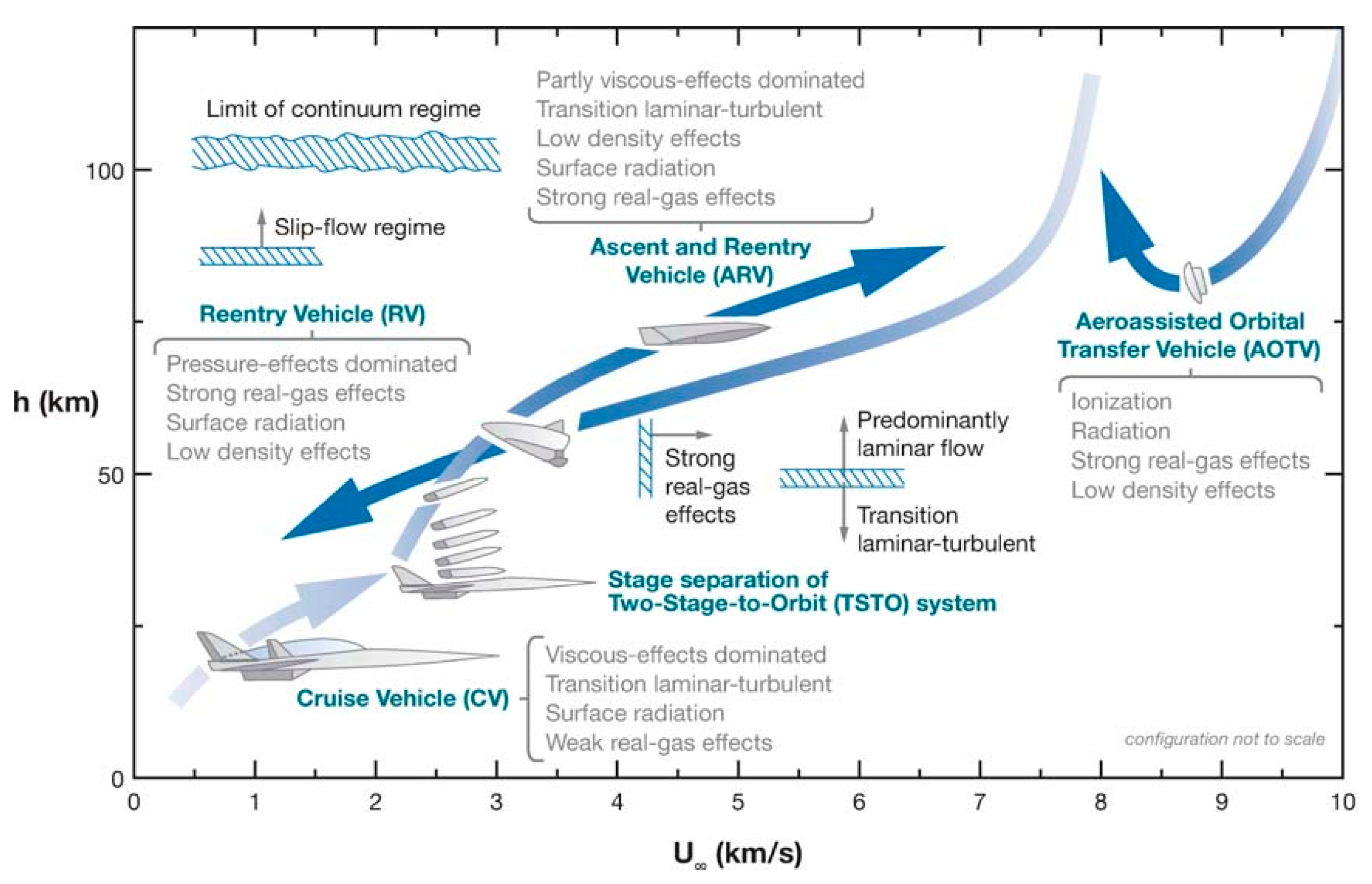

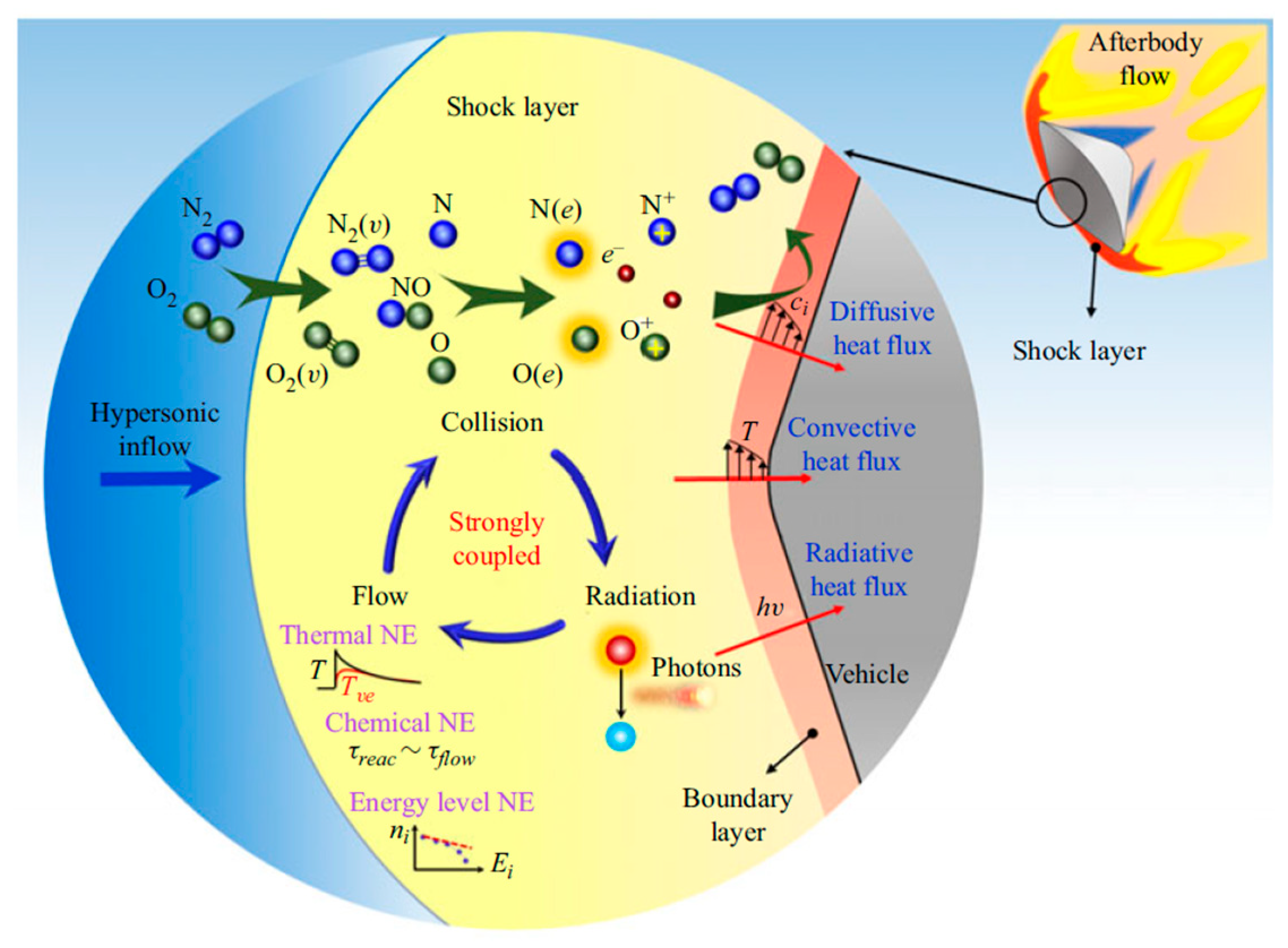

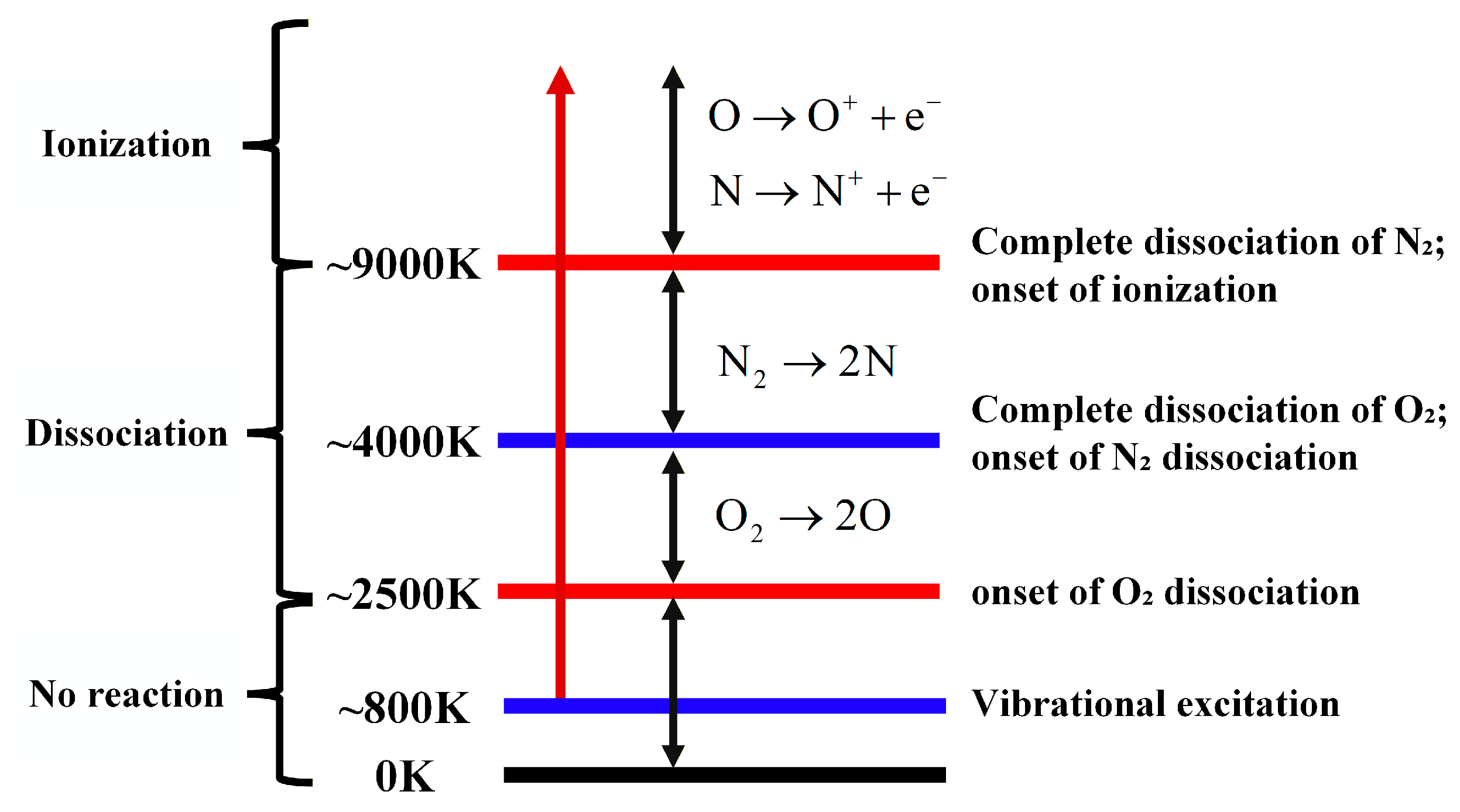

As shown in Fig. 7, under a wide range of freestream conditions, hypersonic air-breathing vehicles inevitably encounter significant changes in the physical and chemical properties of the flow [69,70]. In Fig. 8, the most prominent feature of hypersonic flow is the high-temperature effect [52], which includes the excitation of molecular internal energy modes and the dissociation, exchange, recombination, and ionization reactions of the freestream species. These processes significantly alter the shock standoff distances, species concentrations, and flow parameter distributions, leading to characteristics that deviate from those of a calorically perfect gas [52,69,71]. Thermodynamic excitation and chemical reactions, coupled with high-speed flow, yield energy mode relaxation and chemical reaction processes whose characteristic timescales are comparable to those of the flow dynamics [72,73]. This coupling is typically characterized as thermochemical nonequilibrium flow [74,75,76]. In hypersonic flows, equilibrium, nonequilibrium, and frozen flow may coexist and cannot be strictly distinguished. The equilibrium and frozen flow are commonly regarded as two limiting cases of nonequilibrium flow, which can be described within a unified thermochemical nonequilibrium [77,78].

Figure 7: Thermochemical states of hypersonic vehicles under wide-ranging freestream conditions [79].

Figure 8: Thermochemical state of atmospheric molecules under high temperature conditions [80].

Under such high-temperature conditions, the calorically perfect gas assumption breaks down, necessitating the accurate modeling of thermodynamic properties, transport coefficients, species diffusion, and finite-rate chemical kinetics of air species. Under the continuum hypothesis, the high-speed and high-temperature fluid can be modeled as a chemically reacting mixture of multiple species, each assumed to behave as a thermally perfect gas. This study solves the compressible Navier-Stokes equations based on the relative temperature model framework, coupled with finite-rate chemical kinetics to depict thermochemical nonequilibrium flow.

Considering the complexity of the thermochemical nonequilibrium, extensive efforts have been devoted to the development of thermochemical models, numerical schemes, and CFD solvers, with considerable progress achieved [72]. Concurrently, significant advances have been made in understanding thermochemical nonequilibrium effects on aerodynamic heating loads through wind tunnel experiments, engineering computations, and numerical simulations, including investigations of physical-chemical models, chemical reaction kinetics, wall catalysis, and material ablation [81,82,83]. Thermochemical nonequilibrium effects are strongly influenced by flight altitude and Mach number. Increasing altitude intensifies thermodynamic nonequilibrium but suppresses chemical reactions [84], while higher flight speeds amplify the impact of nonequilibrium effects [85]. One of the most pronounced effects of thermochemical nonequilibrium is the variation in shock standoff distance. As the Mach number increases, the standoff distance decreases [86], whereas the influence of altitude is confined to a limited range [86].

The thermodynamic temperature model and chemical kinetics models affect the distribution of flow field parameters. The thermochemical state of the flow depends on multiple factors, including flight speed, altitude, vehicle geometry, pressure, and temperature. In practice, the selection of an appropriate thermodynamic temperature model should reflect the specific flow characteristics. Commonly used models include the one-temperature, two-temperature, and three-temperature models. More advanced approaches involve multi-vibrational-temperature models that account for the distinct vibrational excitation temperatures of different molecules [87], and even state-to-state models based on quantum mechanics [88,89].

In statistical mechanics, gas molecules are typically assumed to behave independently, and their internal energy is partitioned among several modes, including translational, rotational, vibrational, and electronic energies. Energy exchange occurs continuously among these modes throughout the flowfield. Under given temperature and pressure conditions, if the gas molecules undergo sufficient intermolecular collisions, the energy transfer among the translational, rotational, vibrational, and electronic modes reaches equilibrium. In this state, the thermodynamic properties of the gas no longer vary with time, and all energy modes can be characterized by one temperature. The flow is then regarded as being in thermodynamic equilibrium, corresponding to the conventional one-temperature model (1T) [90,91].

As the flight altitude increases and the ambient air density decreases, the intermolecular collision frequency is reduced. Combined with the high flight velocity, the residence time of gas molecules within the flow field becomes significantly shorter, leaving insufficient time for collisions to establish equilibrium among the different internal energy modes. Consequently, the thermodynamic processes associated with translational, rotational, vibrational, and electronic excitations lag behind their equilibrium states, and the flow enters a thermochemical nonequilibrium regime. Under such conditions, the one-temperature model no longer provides reliable predictions of flowfield properties. Instead, the relaxation processes associated with energy transfer among the various internal modes must be taken into consideration, which necessitates the use of multi-temperature models to describe the thermodynamic behavior of the gas [92,93,94]. The two-temperature model (2T) is a representative formulation for thermochemical nonequilibrium. It assumes that energy exchange between translational and rotational modes is sufficiently rapid to maintain near-equilibrium, allowing these modes to be characterized by a common translational-rotational temperature. In contrast, vibrational and electronic excitations in hypersonic flows require many more molecular collisions, resulting in much longer relaxation times compared with translational-rotational energy. However, vibrational-electronic coupling remains relatively fast, enabling these modes to reach equilibrium with each other. Therefore, a separate vibrational-electronic temperature is introduced to describe their thermodynamic state [95,96].

In addition to internal energy excitation, chemical reactions constitute another major challenge encountered in hypersonic flows. As illustrated in Fig. 9, when the post-shock temperature rises to approximately 2500 K, molecular oxygen begins to dissociate and becomes fully dissociated near 4000 K. This temperature marks the onset of nitrogen dissociation, which continues until the flow temperature reaches roughly 9000 K, at which point nitrogen is fully dissociated. Beyond this temperature range, ionization reactions become significant, leading to the formation of a partially ionized plasma [97]. Between 4000 K and 9000 K, a small amount of NO is also produced. Under these conditions, the thermodynamic properties of the gas mixture may be considered those of a fully reacting mixture, with each species following the characteristics of a thermally perfect gas. These phenomena demonstrate that high-temperature-induced chemical reactions cause substantial variations in species composition within the flow field, giving rise to chemical diffusion heat transfer at the vehicle surface. Similar to the excitation of internal energy modes, chemical reactions are governed by molecular collisions. However, because different reactions require vastly different numbers of collisions to proceed, hypersonic flows generally exhibit pronounced chemical nonequilibrium effects [98,99].

Figure 9: Physicochemical processes in high-enthalpy air across different temperature ranges.

Chemical kinetics models play a crucial role in determining the thermodynamic properties, species composition, temperature, and heat flux distribution in hypersonic flows, making them critical to the accurate prediction of aerothermal environments. Representative models include those proposed by Park [100,101], Gupta et al. [102], and Dunn et al. [103]. According to the treatment of ionization reactions and their intensity, chemical kinetics models are typically formulated with 5, 7, or 11 species. Due to differences in their reaction rate formulations and in the treatment of vibration-dissociation energy coupling [104], these models produce distinct predictions of shock standoff distance, shock interaction, and heat flux distributions. Previous studies have shown that the Gupta model predicts a larger shock standoff distance than the Dunn-Kang and Park models [105,106]. In complex flow regions such as shock/shock interactions, the discrepancies in peak heat flux predicted by different chemical kinetics models can exceed 25% [106]. These findings highlight that the choice of thermochemical model has a decisive impact on the flow field structures and wall heat flux, necessitating a balance between modeling accuracy and computational cost [107].

Under low-altitude and low-Mach-number conditions, variations in species and temperature models cause minor differences in the predicted flowfield and wall characteristics. Therefore, simplified species models combined with the 1T assumption can be used to reduce computational costs. In contrast, under high-altitude and high-Mach-number conditions, 1T models are inadequate for capturing detailed flowfield structures and thermochemical nonequilibrium effects, which require the use of multi-temperature models for accuracy. Additionally, as the number of chemical species increases, the discrepancy between flowfield predictions from different temperature models tends to decrease. This trend suggests that, under high-Mach-number conditions, including a more comprehensive set of species and chemical reactions is crucial for achieving more precise flowfield descriptions and better representation of thermochemical nonequilibrium effects, thus enhancing the reliability of hypersonic flow predictions.

To further investigate the complex flow features under thermochemical nonequilibrium conditions, studies have been conducted on shock interactions and their influence on aerodynamic heating loads. Results have indicated that under high-temperature effects, the classical theoretical criterion for shock interaction based on the calorically perfect gas model is no longer applicable, as the critical angle and hysteresis interval of shock interaction transition increase [108,109]. In such cases, the critical angle can be determined from the shock polar diagram of nonequilibrium streamlines [109]. While only vibrational excitation does not alter the geometric angle of shock interaction, it affects the position of shock interaction and the intensity of the jet [110]. Under high-temperature conditions, increasing model size and the freestream Mach number induce shock interaction transformations of the VSLEs [111,112,113]. Compared with calorically perfect gases, thermochemical nonequilibrium reduces the critical parameters for shock interaction [112], shifts the shock interaction location upstream [113], enhances MS deformation [114], and moves the wall pressure and heat-flux peaks closer to the stagnation point [115]. Furthermore, under the effect of thermochemical nonequilibrium, a correlation has been established between wall heat flux, Mach and Reynolds numbers, enabling a rapid estimation method to assess the influence of freestream conditions and model scale on the wall heat flux at VSLEs [39,111].

In summary, hypersonic flows exhibit highly complex behavior, with pronounced thermochemical nonequilibrium effects that alter the flow structure and the wall aerodynamic heating loads. These effects give rise to shock interaction at VSLEs that differ from those predicted by the calorically perfect gas, and they modify the transition criteria of shock interaction, thereby posing challenges to understanding the shock interaction mechanisms and predicting wall loads. Nevertheless, studies under the calorically perfect gas remain of great importance. Extensive experimental and numerical studies based on this model have clarified the fundamental structures of shock interaction, the evolution of interaction types with Mach and geometry, and the distribution of wall heat flux under different shock interactions, thereby providing a foundation for subsequent research into thermochemical nonequilibrium effects.

5 Conclusions and Perspectives

For hypersonic air-breathing vehicles, the V-shaped leading edge of the inlet involves intricate shock interactions and severe aerodynamic heating loads. This paper focuses on the characteristics of shock interaction of VSLEs, with emphasis on the shock interaction transition and wall loads variation under different freestream Mach numbers and geometric parameters. The transition mechanisms, unsteady oscillations, hysteresis, and three-dimensional effects of shock interactions are examined in detail. Thermal protection strategies for alleviating extreme wall loads are proposed. This review further synthesizes recent studies on thermochemical nonequilibrium flows and their effects on shock interactions, providing a clear contrast to much of the existing literature, which primarily focuses on shock interaction phenomena under calorically perfect gas assumptions.

However, most existing studies on shock interactions and the aerothermal characteristics of VSLEs have been comprehensive under some relatively low hypersonic Mach numbers, such as Ma = 6, with comparatively little attention given to thermo-chemical nonequilibrium effects. However, it is well recognized that hydrogen-fueled hypersonic air-breathing vehicles operate at much higher Ma, reaching Ma 12 or beyond. Under high-enthalpy conditions, the transition of shock interaction and the variation of wall aerodynamic heating loads under different geometric parameters, Mach numbers, and their combined effects remain incomplete. Moreover, most existing theoretical transition formulations for shock interaction, correlations for peak heat flux and peak pressure, and empirical relations for wall heat flux based on Mach and Reynolds numbers have been developed under the calorically perfect gas assumption, with little consideration of thermochemical nonequilibrium effects.

This study does not systematically address the effects of Reynolds number or turbulence modeling. However, both factors play a critical role in shaping the complex shock interaction, flow separation, jet, and unsteady characteristics of the VSLEs. These effects can lead to wall heat flux and pressure levels that differ by orders of magnitude from those predicted under laminar flow assumptions. The situation becomes even more complex under high-enthalpy conditions, where the inclusion of thermochemical nonequilibrium effects further complicates the flow physics. Future studies should place greater emphasis on elucidating the underlying mechanisms associated with Reynolds number, turbulence, and their coupling with thermochemical nonequilibrium effects, to establish a solid foundation for high-fidelity aerodynamic and aerothermal prediction.

Currently, numerical simulations of shock interaction are typically conducted using Reynolds-Averaged Navier-Stokes (RANS) or Large Eddy Simulation (LES) methods, which are challenging to utilize in capturing the full complexity of the flow phenomena. Under thermochemical nonequilibrium conditions, the physical-chemical models of shock interaction remain incomplete, and their accuracy in predicting wall aerothermal loads requires further validation. Future research may focus on developing hybrid RANS-LES simulations (e.g., IDDES and DDES) to more accurately capture the vortex and the unsteady characteristics of shock interactions. In addition, machine learning-based surrogate models, such as physics-informed neural networks (PINNs) and multifidelity deep learning approaches, can be constructed by leveraging high-fidelity DNS data to significantly reduce computational cost while preserving the essential physical mechanisms.

Experimental data for V-shaped leading edges are also limited, particularly under extreme test conditions and high Mach numbers. Such experiments are technically challenging, costly, and difficult to conduct, and limitations in diagnostic techniques make it difficult to obtain sufficiently detailed flow field characteristics and wall heat flux measurements. The advancement of high-speed infrared thermography and pressure-sensitive materials will enable more accurate measurements of aerodynamic and aerothermal characteristics.

Acknowledgement:

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Research Fund of National Key Laboratory of Aerospace Physics in Fluids, grant number 2024-APF-KFZD-01, Guangdong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation, grant number 2025A1515012081, National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 12002193, and Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, China, grant number ZR2019QA018.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Jingying Wang, Chunhian Lee and Xinyue Dong; methodology, Jingying Wang; formal analysis, Xinyue Dong, Wei Zhao and Shiyue Zhang; investigation, Yue Zhou and Xinglian Yang; resources, Jingying Wang and Xinyue Dong; writing—original draft preparation, Xinyue Dong; writing—review and editing, Jingying Wang; visualization, Jingying Wang; supervision, Jingying Wang and Chunhian Lee; project administration, Jingying Wang; funding acquisition, Jingying Wang. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| VSLEs | V-Shaped Leading Edges |

| RR | Regular Reflection |

| MR | Mach Reflectio |

| sRR | Regular Reflection from the Same Family |

| InMR | Inverse Mach Reflection |

| StMR | Stationary Mach Reflection |

| DiMR | Direct Mach Reflection |

| DS | Detached Shock |

| MS | Mach Stem |

| BS | Bow Shock |

| TS | Transmitted Shock |

| IP | Interference Point |

| SS | Separation Shock |

| CS | Curved Shock |

| SBLI | Shock-Boundary Layer Interaction |

| SMS | Secondary Mach Reflection Structure |

References

1. Kim C , Gwan D , Nam MS . Beyond the atmosphere: the revolution in hypersonic flight. Fusion Multidiscip Res Int J. 2021; 2( 1): 152– 63. doi:10.63995/idxp9691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Van Wie D . Hypersonics: past, present, and potential future. Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig. 2021; 35( 4): 335– 41. [Google Scholar]

3. Viola N , Fusaro R , Vercella V . Technology roadmapping methodology for future hypersonic transportation systems. Acta Astronaut. 2022; 195: 430– 44. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2022.03.038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Boretti A . Hydrogen hypersonic combined cycle propulsion: advancements, challenges, and applications. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2024; 55: 394– 9. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2023.11.234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Slayer KM . Hypersonic weapons: background and issues for congress. Washington, DC, USA: Congressional Research Service; 2022. Report No.: R45811. [Google Scholar]

6. Liu C , Ai J , Zhang J , Li X , Zhao Z , Huang W . Research progress of the flow and combustion organization for the high-Mach-number scramjet: from Mach 8 to 12. Prog Aerosp Sci. 2025; 155: 101094. doi:10.1016/j.paerosci.2025.101094. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Min C , Fu Q , Jiao Z . Records of hypersonic flight. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2019. p. 146– 56. [Google Scholar]

8. Ding Y , Yue X , Chen G , Si J . Review of control and guidance technology on hypersonic vehicle. Chin J Aeronaut. 2022; 35( 7): 1– 18. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2021.10.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Van Wie DM , D’Alessio SM , White ME . Hypersonic airbreathing propulsion. Johns Hopkins APL Tech Dig. 2005; 26( 4): 430– 7. [Google Scholar]

10. Kumar S , Murari Pandey K , Kumar Sharma K . Recent developments in technological innovations in scramjet engines: a review. Mater Today Proc. 2021; 45: 6874– 81. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2020.12.1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. You YC , Liang DW , Guo RW , Huang GP . Overview of the integration of three-dimensional inward-turning hypersonic inlet and waverider forebody. Adv Mech. 2009; 39: 513– 25. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

12. Zheng XG , Shi CG , Zhang J , Zhang M , Zhu WL , Zhu CX , et al. Research progress review on hypersonic three-dimensional inward-turning inlet. Acta Aeronaut Astronaut Sin. 2025; 46( 8): 54– 92. (In Chinese). doi:10.7527/S1000-6893.2024.31245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Walker S , Rodgers F , Paull A , Van Wie D . HyCAUSE flight test program. In: Proceedings of the 15th AIAA International Space Planes and Hypersonic Systems and Technologies Conference; 2008 Apr 28–May 1; Dayton, OH, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2008-2580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Zuo FY , Mölder S . Hypersonic wavecatcher intakes and variable-geometry turbine based combined cycle engines. Prog Aerosp Sci. 2019; 106: 108– 44. doi:10.1016/j.paerosci.2019.03.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Hu Z , Li Z , Tang Y , Yu Y , Zhang Y , Zheng X , et al. Conceptual design methodology and performance evaluation of turbine-based combined cycle inward-turning inlet with twin-design points. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2024; 152: 109309. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2024.109309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Ligrani PM , McNabb ES , Collopy H , Anderson M , Marko SM . Recent investigations of shock wave effects and interactions. Adv Aerodyn. 2020; 2( 1): 4. doi:10.1186/s42774-020-0028-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Bisek NJ . High-fidelity simulations of the HIFiRE-6 flow path at angle of attack. In: Proceedings of the 46th AIAA Fluid Dynamics Conference; 2016 Jun 13–17; Washington, DC, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2016-4276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Xiao F . Research on flow characteristics of some typical hypersonic shock wave interactions [ dissertation]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2016. [Google Scholar]

19. Xiao F , Li Z , Zhang Z , Zhu Y , Yang J . Hypersonic shock wave interactions on a V-shaped blunt leading edge. AIAA J. 2018; 56( 1): 356– 67. doi:10.2514/1.j055915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Meng Z , Fan X , Xiong B , Tao Y . Investigation of aerodynamic heating in V-shaped cowl-lip of the inward turning inlet. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part G J Aerosp Eng. 2019; 233( 8): 2792– 801. doi:10.1177/0954410018787137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li Z , Zhang Z , Wang J , Yang J . Pressure–heat flux correlations for shock interactions on V-shaped blunt leading edges. AIAA J. 2019; 57( 10): 4588– 92. doi:10.2514/1.j058538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Wang J , Li Z , Zhang Z , Yang J . Shock interactions on V-shaped blunt leading edges with various conic crotches. AIAA J. 2020; 58( 3): 1407– 11. doi:10.2514/1.j059067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang Z , Li Z , Huang R , Yang J . Experimental investigation of shock oscillations on V-shaped blunt leading edges. Phys Fluids. 2019; 31( 2): 026110. doi:10.1063/1.5084184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhang Z , Li Z , Yang J . Transitions of shock interactions on V-shaped blunt leading edges. J Fluid Mech. 2021; 912: A12. doi:10.1017/jfm.2020.1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Edney B . Anomalous heat transfer and pressure distributions on blunt bodies at hypersonic speeds in the presence of an impinging shock. Linköping, Sweden: Flygtekniska Forsoksanstalten; 1968. Report No.: FFA-115. doi:10.2172/4480948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Wang D , Li Z , Zhang Z , Liu NS , Yang J , Lu XY . Unsteady shock interactions on V-shaped blunt leading edges. Phys Fluids. 2018; 30( 11): 116104. doi:10.1063/1.5051012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Zhang E , Li Z , Li Y , Yang J . Three-dimensional shock interactions and vortices on a V-shaped blunt leading edge. Phys Fluids. 2019; 31( 8): 086102. doi:10.1063/1.5101031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang E . Three-dimensional shock interactions in hypersonic internal/external integration flows [ dissertation]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2019. [Google Scholar]

29. Zhang Z . Shock interactions and aerothermal heating/pressure behaviors on V-shaped blunt leading edges [ dissertation]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2020. [Google Scholar]

30. Wang J , Li Z , Zhang Z , Yang J . Effects of geometry parameters on aerothermal heating loads of V-shaped blunt leading edges. Chin J Theor Appl Mech. 2021; 53( 12): 3274– 83. [Google Scholar]

31. Zhang T , Cheng J , Shi C , Zhu C , You Y . Mach reflection of three-dimensional curved shock waves on V-shaped blunt leading edges. J Fluid Mech. 2023; 975: A45. doi:10.1017/jfm.2023.866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Kang D , Yan C , Liu S , Wang Z , Jiang Z . Modelling and shock control for a V-shaped blunt leading edge. J Fluid Mech. 2023; 968: A15. doi:10.1017/jfm.2023.447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Keyes J , Hains F . Analytical and experimental studies of shock interference heating in hypersonic flows. Hampton, VA, USA: NASA Langley Research Center; 1973. Report No.: NASA TN D-7139. [Google Scholar]

34. Li Z , Wang J , Zhang Z , Yang JM . Shock interactions generated by V-shaped blunt leading edges. Aerodyn Res Exp. 2024; 2: 1– 13. [Google Scholar]

35. Zhang Z , Li Z , Yang J . Categories of shock reflections on the V-shaped blunted leading edge. In: 18th Chinese National Symposium on Shock Waves; 2018 Jun 14–18; Beijing, China. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

36. Ben-Dor G . Shock wave reflection phenomena. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 1992. doi:10.1007/978-1-4757-4279-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang Z , Li Z , Xiao F , Zhu Y , Yang J . Shock interaction on a V-shaped blunt leading edge. In: 31st International Symposium on Shock Waves 1. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 799– 806. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-91020-8_95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Wang D . Large-eddy simulation of the complex flow involving shock wave, separation and turbulent [ dissertation]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2018. [Google Scholar]

39. Zhou B . Shock interactions and aerodynamic loads in the upstream/downstream flow of V-shaped blunt leading edges at high Mach numbers [ dissertation]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2023. [Google Scholar]

40. Zhang T , Rao L , Zhang X , Shi C , Zhu C , You Y . Heating reduction with shock control for a V-shaped blunt leading edge. J Fluid Mech. 2025; 1002: A15. doi:10.1017/jfm.2024.1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Allen H . The aerodynamic heating of atmosphere entry vehicles: a review. Mountain View, CA, USA: NASA, Ames Research Center; 1964. Report No.: NASA TM X-54,056. [Google Scholar]

42. Vincenti WG , Boyd JW , Bugos GE . H. Julian Allen: an appreciation. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2007; 39: 1– 17. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.39.052506.084853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Meng Z , Fan X , Xiong B , Tao Y . Investigation of aerothermal heating on V-shaped leading edge of inward turning inlet. J Propuls Technol. 2018; 39: 1737– 43. [Google Scholar]

44. Zhang Y , Wang J , Li Z . Shock-induced heating loads on V-shaped leading edges with elliptic cross section. AIAA J. 2022; 60( 12): 6958– 62. doi:10.2514/1.j062013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Wang J , Li Z , Yang J . Shock-induced pressure/heating loads on V-shaped leading edges with nonuniform bluntness. AIAA J. 2021; 59( 3): 1114– 8. doi:10.2514/1.j059990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Liu S , Yan C , Kang D , Jiang Z , Sun M . Opposing jets for heat flux reduction and uncertainty analysis on a V-shaped blunt leading edge. Aerosp Sci Technol. 2023; 138: 108353. doi:10.1016/j.ast.2023.108353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang T , Zhang X , Rao L , Shi C , Zhu C , You Y . Mach reflection and pressure/heating loads on V-shaped blunt leading edges with variable cross-sections and crotches. Chin J Aeronaut. 2025; 38( 1): 103163. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2024.07.035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Gaitonde DV , Adler MC . Dynamics of three-dimensional shock-wave/boundary-layer interactions. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2023; 55: 291– 321. doi:10.1146/annurev-fluid-120720-022542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Sabnis K , Babinsky H . A review of three-dimensional shock wave–boundary-layer interactions. Prog Aerosp Sci. 2023; 143: 100953. doi:10.1016/j.paerosci.2023.100953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Helm CM , Martín MP . Scaling of hypersonic shock/turbulent boundary layer interactions. Phys Rev Fluids. 2021; 6( 7): 074607. doi:10.1103/physrevfluids.6.074607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Passiatore D , Sciacovelli L , Cinnella P , Pascazio G . Thermochemical non-equilibrium effects in turbulent hypersonic boundary layers. J Fluid Mech. 2022; 941: A21. doi:10.1017/jfm.2022.283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Shang JJS , Yan H . High-enthalpy hypersonic flows. Adv Aerodyn. 2020; 2( 1): 19. doi:10.1186/s42774-020-00041-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Huete C , Cuadra A , Vera M , Urzay J . Thermochemical effects on hypersonic shock waves interacting with weak turbulence. Phys Fluids. 2021; 33( 8): 086111. doi:10.1063/5.0059948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Passiatore D , Sciacovelli L , Cinnella P , Pascazio G . Shock impingement on a transitional hypersonic high-enthalpy boundary layer. Phys Rev Fluids. 2023; 8( 4): 044601. doi:10.1103/physrevfluids.8.044601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Li W , Wang T , Zhang Z , Zhang J , Dong Z , Huang H , et al. Design of ablation resistant/heat insulation/lightweight integrated thermal protection material for extreme aerothermodynamic environment. Polym Compos. 2021; 42( 12): 6749– 63. doi:10.1002/pc.26336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Jiang H , Liu J , Luo S , Huang W , Wang J , Liu M . Thermochemical non-equilibrium effects on hypersonic shock wave/turbulent boundary-layer interaction. Acta Astronaut. 2022; 192: 1– 14. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2021.12.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Teixeira O , Páscoa J . Numerical analysis of a hypersonic body under thermochemical non-equilibrium and different catalytic surface conditions. Actuators. 2025; 14( 2): 102. doi:10.3390/act14020102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Cui Z , Zhao J , Yao G , Zhang J , Li Z , Tang Z , et al. Competing effects of surface catalysis and ablation in hypersonic reentry aerothermodynamic environment. Chin J Aeronaut. 2022; 35( 10): 56– 66. doi:10.1016/j.cja.2021.11.025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Han L , Han Y . Effect of surface ablation on aerodynamic heating over a blunt cone in hypersonic airflow. Phys Fluids. 2024; 36( 3): 036110. doi:10.1063/5.0196415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Mortensen CH . Effects of thermochemical nonequilibrium on hypersonic boundary-layer instability in the presence of surface ablation or isolated two-dimensional roughness [ dissertation]. Los Angeles, CA, USA: University of California; 2015. [Google Scholar]

61. Al-Jothery HM , Albarody TB , Yusoff PM , Abdullah MA , Hussein AR . A review of ultra-high temperature materials for thermal protection system. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020; 863( 1): 012003. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/863/1/012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. He S , Zhao W , Dong X , Zhang Z , Wang J , Yang X , et al. Analysis of aerodynamic heating modes in thermochemical nonequilibrium flow for hypersonic reentry. Energies. 2025; 18( 13): 3417. doi:10.3390/en18133417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

63. Dai C , Sun B , Zhao D , Zhou S , Zhou C , Man Y . Numerical investigations on flow and heat transfer characteristics of a high-enthalpy double-cone in thermal and chemical non-equilibrium for hypersonic propulsion. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2024; 155: 107522. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.107522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Brune AJ , Hosder S , Edquist KT , Tobin SA . Thermal protection system response uncertainty of a hypersonic inflatable aerodynamic decelerator. J Spacecr Rockets. 2017; 54( 1): 141– 54. doi:10.2514/1.a33732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Miyashita T , Sugihara Y , Takahashi Y . Communication blackout and aerodynamic heating reduction via air film for hypersonic spacecraft. J Appl Phys. 2025; 137( 17): 174701. doi:10.1063/5.0250348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Wang K , Chen X , Wen Z . Analysis of low-frequency communication of hypersonic vehicles in thermodynamic and chemical non-equilibrium state. Appl Sci. 2023; 13( 19): 10815. doi:10.3390/app131910815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Vu HH , Viti V , Tharp J , Staggs E . Prediction of communication blackout and degradation for a re-entry hypersonic capsule through high-fidelity numerical simulations. In: Proceedings of the AIAA SciTech 2023 Forum; 2023 Jan 23–27; National Harbor, MD, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2023-2561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Le Maout V , Jo SM , Munafò A , Panesi M . Numerical investigation of radiative transfers interactions with material ablative response for hypersonic atmospheric entry. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2025; 246: 126999. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2025.126999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Anderson J . Hypersonic and high temperature gas dynamics. 3rd ed. New York, NY, USA: McGraw-Hill Book Company; 2019. p. 7– 15. [Google Scholar]

70. Yan Z , Lu Z , Wang W . Aerodynamics. Beijing, China: Science Press; 2018. p. 2– 8. [Google Scholar]

71. Surzhikov S , Shang J . Kinetic models analysis for super-orbital aerophysics. In: Proceedings of the 46th AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting and Exhibit; 2008 Jan 7–10; Reno, NV, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2008-1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Gao Z , Jiang C , Li C . Review of numerical simulation methods for hypersonic and high-enthalpy non-equilibrium flow. Adv Mech. 2023; 53( 3): 561– 91. [Google Scholar]

73. Kane AA , Peetala RK . Influence of vibration–dissociation coupling and number of reactions in hypersonic nonequilibrium flows. J Fluids Eng. 2022; 144( 8): 081207. doi:10.1115/1.4053650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Dong W . Numerical simulation and analysis of thermochemical nonequilibrium effects at hypersonic flow [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: Beihang University; 1996. [Google Scholar]

75. Hao J . Modeling of thermochemical nonequilibrium coupling effects in hypersonic flows [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: Beihang University; 2018. [Google Scholar]

76. Wang J . Numerical study on coupled effects of the chemical nonequilibrium and thermal radiation in high-speed and high-temperature flows [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: Beihang University; 2017. [Google Scholar]

77. Li H . Numerical simulation of hypersonic and high-temperature gas flowfields [ dissertation]. Mianyang, China: China Aerodynamics Research and Development Center; 2007. [Google Scholar]

78. Ding M . Numerical simulation of magnetohydrodynamic control for hypersonic nonequilibrium flow [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: Academy of Military Sciences; 2019. [Google Scholar]

79. Bertin JJ , Cummings RM . Critical hypersonic aerothermodynamic phenomena. Annu Rev Fluid Mech. 2006; 38: 129– 57. doi:10.1146/annurev.fluid.38.050304.092041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Du Y , Sun S , Tan M , Huang H , Yan C , Meng X , et al. Numerical study on the non-equilibrium characteristics of high-speed atmospheric re-entry flow and radiation of aircraft based on fully coupled model. J Fluid Mech. 2023; 977: A39. doi:10.1017/jfm.2023.962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Yu C , Liu W . Research status of aeroheating prediction technology for hypersonic aircraft. Aeronaut Sci Technol. 2021; 32( 2): 14– 21. [Google Scholar]

82. Peng ZY , Shi YL , Gong HM , Li Z , Luo Y . Hypersonic aeroheating prediction technique and its trend of development. Acta Aeronaut Et Astronaut Sin. 2015; 36( 1): 325– 45. [Google Scholar]

83. Mo F , Gao Z , Jiang C , Lee CH . Progress in the numerical study on the aerodynamic and thermal characteristics of hypersonic vehicles: high-temperature chemical non-equilibrium effect. Sci Sin Phys Mech Astron. 2021; 51( 10): 104703. doi:10.1360/sspma-2021-0110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Chae JH , Mankodi TK , Choi SM , Myong RS . Combined effects of thermal non-equilibrium and chemical reactions on hypersonic air flows around an orbital reentry vehicle. Int J Aeronaut Space Sci. 2020; 21( 3): 612– 26. doi:10.1007/s42405-019-00243-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Emelyanov V , Karpenko A , Volkov K . Simulation of hypersonic flows with equilibrium chemical reactions on graphics processor units. Acta Astronaut. 2019; 163: 259– 71. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2019.01.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Yu M , Qiu Z , Zhong B , Takahashi Y . Numerical simulation of thermochemical non-equilibrium flow-field characteristics around a hypersonic atmospheric reentry vehicle. Phys Fluids. 2022; 34( 12): 126103. doi:10.1063/5.0131460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Wang Y . Research of numerical calculation methods based on multi-vibrational temperature model in high-temperature conditions [ dissertation]. Changsha, China: National University of Defense Technology; 2016. [Google Scholar]

88. Xu D , Zeng M , Zhang W , Liu J . Numerical study of thermochemical nonequilibrium nozzle flow in state-to-state model. Chin J Comput Phys. 2014; 31( 5): 531– 8. [Google Scholar]

89. Li H , Shi A , Ma P , Luo W . Recent advances in hypersonic nonequilibrium flows. In: Proceedings of the Chinese Congress of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics 2017 and the 60th Anniversary of CSTAM; 2017 Aug 13; Beijing, China. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

90. Zhang W , Zhang Z , Wang X , Su T . A review of the mathematical modeling of equilibrium and nonequilibrium hypersonic flows. Adv Aerodyn. 2022; 4( 1): 38. doi:10.1186/s42774-022-00125-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Karpenko A , Tolstoguzov S , Volkov K . Simulation of relaxation processes in hypersonic flows with one-temperature non-equilibrium model. Fluids. 2023; 8( 11): 297. doi:10.3390/fluids8110297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Zhao W , Yang X , Wang J , Zheng Y , Zhou Y . Evaluation of thermodynamic and chemical kinetic models for hypersonic and high-temperature flow simulation. Appl Sci. 2023; 13( 17): 9991. doi:10.3390/app13179991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Ninni D , Bonelli F , Colonna G , Pascazio G . Unsteady behavior and thermochemical non equilibrium effects in hypersonic double-wedge flows. Acta Astronaut. 2022; 191: 178– 92. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2021.10.040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Kim C , Kim KH , Yang Y , Kim JG . Effect of multi-temperature models on heat transfer and electron behavior in hypersonic flows. Phys Fluids. 2024; 36( 9): 096127. doi:10.1063/5.0223900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Xiong R , Han Y , Cao W . Improved two-temperature model of hypersonic thermochemical nonequilibrium flows with correction of non-Boltzmann effect for air. Phys Fluids. 2025; 37( 7): 077141. doi:10.1063/5.0274401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Gao X , Ji X , Liu H , Chen G . A two-temperature gas-kinetic scheme for hypersonic non-equilibrium flow computations. Phys Fluids. 2025; 37( 10): 106138. doi:10.1063/5.0297202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Aiken TT , Boyd ID . Sensitivity analysis of ionization in two-temperature models of hypersonic air flows. J Thermophys Heat Transf. 2024; 38( 4): 478– 90. doi:10.2514/1.t6909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Williams C , Di Renzo M , Urzay J , Moin P . Navier-Stokes characteristic boundary conditions for high-enthalpy compressible flows in thermochemical non-equilibrium. J Comput Phys. 2024; 509: 113040. doi:10.1016/j.jcp.2024.113040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Shen J , Shao Z , Ji F , Chen X , Lu H , Ma H . High enthalpy non-equilibrium expansion effects in turbulent flow of the conical nozzle. Aerospace. 2023; 10( 5): 455. doi:10.3390/aerospace10050455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Park C . Assessment of a two-temperature kinetic model for dissociating and weakly ionizing nitrogen. J Thermophys Heat Transf. 1988; 2( 1): 8– 16. doi:10.2514/3.55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Park C , Howe JT , Jaffe RL , Candler GV . Review of chemical-kinetic problems of future NASA missions. II-Mars entries. J Thermophys Heat Transf. 1994; 8( 1): 9– 23. doi:10.2514/3.496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Gupta RN , Yos JM , Thompson RA . A review of reaction rates and thermodynamic and transport properties for the 11-species air model for chemical and thermal nonequilibrium calculations to 30,000 K. Hampton, VA, USA: NASA Langley Research Center; 1989. Report No.: NASA-TM-101528. [Google Scholar]

103. Dunn M , Kang S . Theoretical and experimental studies of reentry plasmas. Hampton, VA, USA: Langley Research Center; 1973. Report No.: NASA-CR-2232. [Google Scholar]

104. Yang Y , Petha Sethuraman VR , Kim JG . Effect of equilibrium constant for carbon dioxide recombination in hypersonic flow analysis. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2023; 45: 102947. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.102947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Martinez Schramm J , Hannemann K , Beck W , Karl S . Cylinder shock layer density profiles measured in high enthalpy flows in HEG. In: Proceedings of the 22nd AIAA Aerodynamic Measurement Technology and Ground Testing Conference; 2002 Jun 24–26; St. Louis, MO, USA. doi:10.2514/6.2002-2913 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Wang XY , Yan C , Zheng YK , Li EL . Assessment of chemical kinetic models on hypersonic flow heat transfer. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2017; 111: 356– 66. doi:10.1016/j.ijheatmasstransfer.2017.03.102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Hao J , Wang J , Lee C . Numerical study of hypersonic flows over reentry configurations with different chemical nonequilibrium models. Acta Astronaut. 2016; 126: 1– 10. doi:10.1016/j.actaastro.2016.04.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Xiong W . On Shock-shock Interaction in double-wedge flow with high temperature non-equilibrium effects [ master’s thesis]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2017. [Google Scholar]

109. Li J . On Shock Interaction and reflections with high temperature non-equilibrium effects [ dissertation]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2015. [Google Scholar]

110. Peng J . Study on strong shock-shock interaction and the associated mechanism of extreme aerodynamic heating [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: University of Chinese Academy of Science; 2021. [Google Scholar]

111. Wang J . Shock interaction and aerothermal protection optimization of V-shaped blunt leading edges in a wide range of speeds [ dissertation]. Hefei, China: University of Science and Technology of China; 2023. [Google Scholar]

112. Li S , Peng J , Luo C , Hu Z . Prediction of shock interference flow field structure based on the multi-level block building algorithm. Chin J Theor Appl Mech. 2021; 53( 12): 3284– 97. (In Chinese). doi:10.6052/0459-1879-21-385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

113. Xiang G . Theory of three-dimensional shock interaction and its application [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: University of Chinese Academy of Science; 2017. [Google Scholar]

114. Shi X . Investigation on shock reflections and interactions with thermo-chemical non-equilibrium effects [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: University of Chinese Academy of Science; 2018. [Google Scholar]

115. Jiang W . Study on aerodynamic characteristics and flow field mechanism of hypersonic V-shaped leading edge [ dissertation]. Beijing, China: University of Chinese Academy of Science; 2022. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools