Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Parametrical Comprehensive Review of Solar Assisted Humidification-Dehumidification Desalination Units

1 Faculty of Mechanical Engineering, Microfluidics and MEMS Lab, Babol Noshirvani University of Technology, Babol, 47148-71167, Iran

2 Air Conditioning and Refrigeration Techniques Engineering Department, Al-Mustaqbal University, Babylon, 51001, Iraq

3 Department of Mechanical Engineering, College of Engineering, University of Baghdad, Baghdad, 10071, Iraq

* Corresponding Author: Zahrah F. Hussein. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Heat and Mass Transfer in Energy Equipment)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(3), 765-817. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.059507

Received 10 October 2024; Accepted 10 January 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

The deficiency of potable water resources and energy supply is emerging as a significant and concerning obstacle to sustainable development. Solar and waste heat-powered humidification dehumidification (HDH) desalination systems become essential due to the severe impacts of global warming and water shortages. This problem highlights the need to apply boosted water desalination solutions. Desalination is a capital-intensive process that demands considerable energy, predominantly sourced from fossil fuels worldwide, posing a significant carbon footprint risk. HDH is a very efficient desalination method suitable for remote areas with moderate freshwater requirements for domestic and agricultural usage. Several operational and maintenance concerns are to blame. The flow and thermal balances of humidifiers and dehumidifiers under the right conditions are crucial for system efficiency. These systems comprise a humidifier and dehumidifier, energy foundations for space or process heating and electricity generation, fluid transfer or efficiency enhancement accessories, and measurement-control devices. All technologies that enhance the performance of HDH systems are elucidated in this work. These are utilizing efficient components, renewable energy, heat recovery via multi-effect and multi-stage processes, waste heat-powered, and accelerating humidification and dehumidification processes through pressure variation or employing heat pumps, in addition to exergy and economical analyses. According to the present work, the seawater HDH system is feasible for freshwater generation. Regarding economics and gain output ratio, humidification–dehumidification is a viable approach for decentralized small-scale freshwater production applications, but it needs significant refinement. System productivity of fresh water is much higher with integrated solar water heating than with solar air heating. The HDH offers the lowest water yield cost per liter and ideal system productivity when paired with a heat pump. The suggested changes aim to enhance system and process efficiency, reducing electrical energy consumption and cost-effective, continuous, decentralized freshwater production. This thorough analysis establishes a foundation for future research on energy and exergy cycles based on humidification and dehumidification.Keywords

The beginning and continuous survival of humans depends on water. Water is among the most plentiful resources on the planet, as it covers practically three-quarters of its surface. About 97% of all the water on earth comes from the oceans, that is, salt water. At the poles, in underground water, lakes, and rivers. Water is essential for humans, animals, and agriculture, as it comes from freshwater sources. Freshwater makes up to 3% of water on earth, that is, ice. Nearly 70% of the world’s freshwater supply is found in glaciers, places with permanent snow cover ice, and 3% in permafrost. Thirty percent of the fresh water on earth is underground; much of it is situated in very deep aquifers and inaccessible. Traditionally, man’s main water sources for household, industrial, and agricultural purposes are rivers, lakes, and underground water reservoirs. Approximately 20% of freshwater utilized worldwide is used for industry, only 10% for domestic consumption, and over 70% for agricultural needs [1].

The UN-Water yearly report for 2021 shows that 2 billion people in developing countries do not have access to qualified water for drinking. Furthermore, 3.6 billion individuals, or 46% of the global population, cannot access suitable sanitation [2]. Approximately 3 billion people worldwide do not have sufficient access to fresh water that meets the required standards in terms of quality and quantity. Additionally, 107 countries are not progressing towards achieving sustainable water resource management by 2030 [2]. However, the demand for freshwater for household applications and agriculture to produce enough nourishment has been greatly raised by growing industrialization and the worldwide population explosion.

Furthermore, the effects of large amounts of sewage dumped and industrial pollutants are problematic, contaminating rivers and lakes. The water issue is especially concerning as typical water consumption doubles every 20 years [1,2]. The only infinite source of water available is the oceans. Their strong salinity is the main drawback. Desalination of the water would thus be ideal to solve the oceans shortage. Water salinity is usually restricted to 500 parts per million (ppm), although it can reach up to (103) ppm in exceptional cases. However, most water on earth has a saltiness of upwards of 10,000 ppm, whereas saltwater generally ranges from 35,000 to 45,000 ppm due to dissolved salt [1,3]. Elevated water salinity causes laxative effects, gastrointestinal pain, and loss of taste. A desalination system aims to produce drinkable TDS fewer than 500 ppm or anywhere from 500–1500 ppm in brackish or salt water [4]. It is carried out using several desalination techniques that will be explored; however, desalination processes consume much energy to extract salts from salt water.

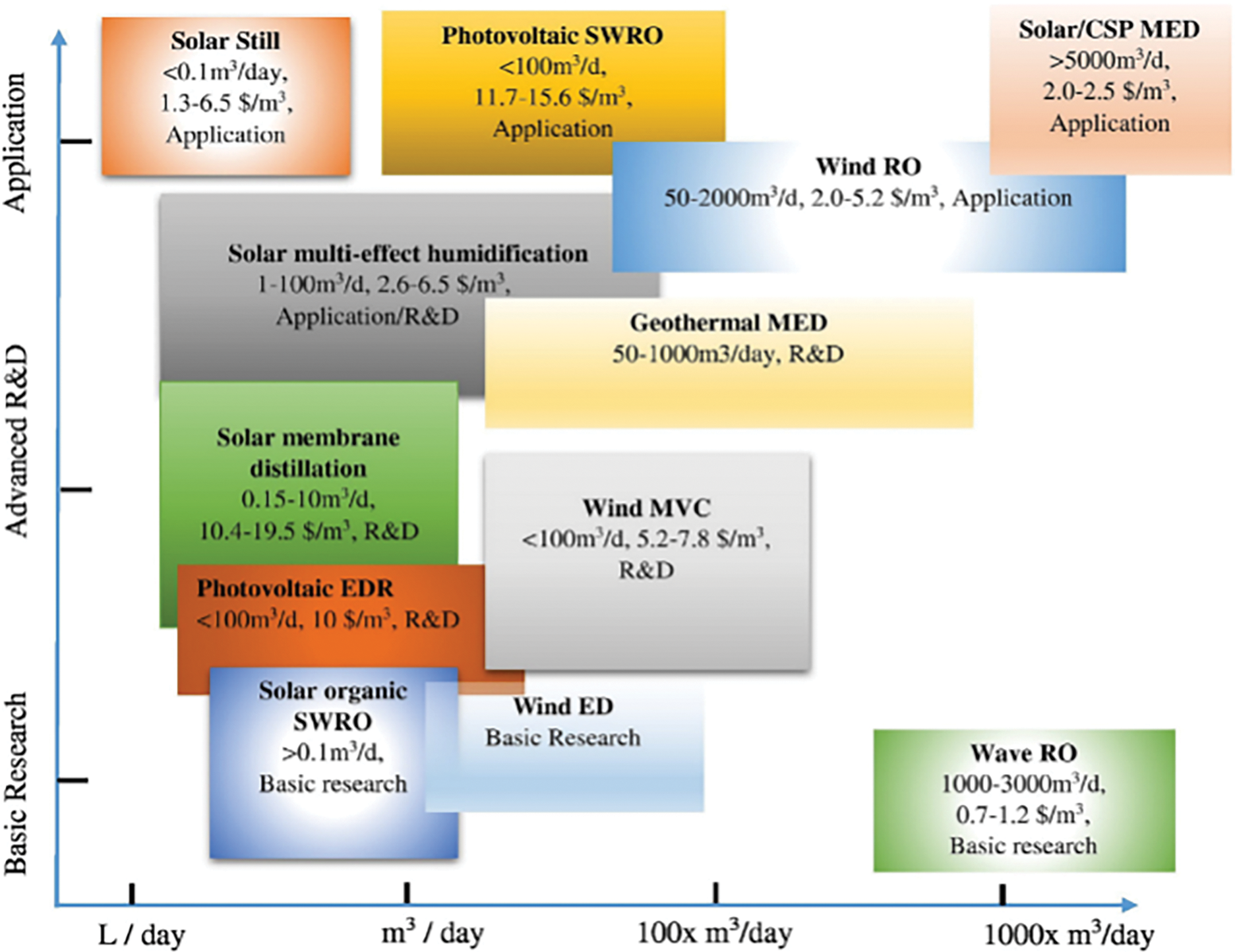

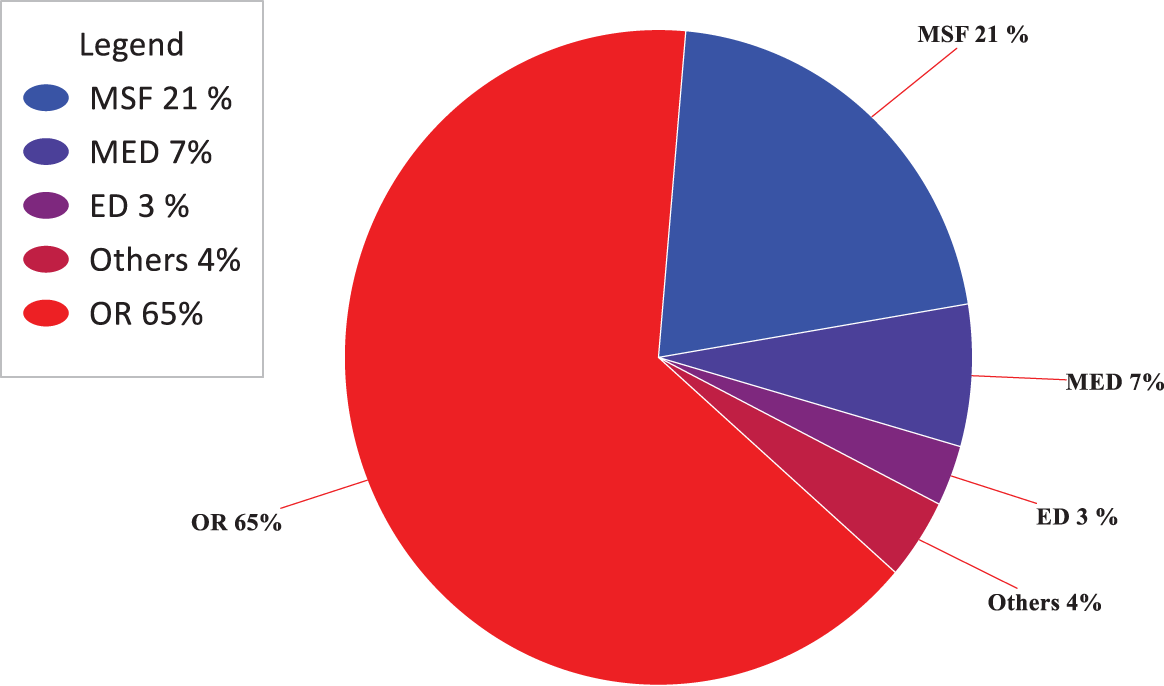

Renewable energy systems generate energy using sustainable sources such as geothermal energy, solar energy, low-quality energy sources, photovoltaic thermal (PV/T) panels, and thermal power plant exhaust heat. Their main virtue is their environmental friendliness. Desalination technology driven by renewable energy systems producing fresh water is seen as an alternative solution to the water shortage in far-off locations lacking accessibility to drinkable drinking water and conventional energy sources, including electric power and heat. Many desalination pilot plants based on renewable energy have been built worldwide, most of which have run efficiently for several years. Nearly all are specifically tailored for specific local areas and produce freshwater using solar or geothermal energy [5]. Although renewable energy-powered desalination systems are not as cost-effective as traditional ones, they are suitable for specific locations. They should become more widely feasible shortly. There were some general suggestions for selecting renewable energy sources and desalination, as well as certain elements for research. Fig. 1 illustrates the technological status of renewable energy desalination techniques [6].

Figure 1: Technological status of renewable energy desalination technologies [6]

Multiple established desalination methods exist, such as RO, MSF, and MED. However, these technologies are quite common and often unsuitable for developing nations due to their extensive infrastructure needs, dependence on fossil fuels for energy, and lack of cost-effectiveness on a large scale.

Various desalination systems based on thermal principles or used membranes are covered to solve the water scarcity problem [7]. Procedures in HDH humidification/dehumidification or vapor compression, either thermal or mechanical (TVC/MVC), multi-effect distillation (MED), multi-stage flash (MSF), and reverse/forward osmosis (RO/FO) are composed. The high-capacity desalination systems are RO, FO, MVC, MSF, TVC, and MED, while HDH covers the suitable medium and small-scale freshwater supply systems [8]. The adoption of massive desalination facilities (such as MSF, MED, or RO) is related to the price of conventional fuel and its availability or requires professional workers [9], typically run on fossil fuels with a significant carbon impact.

A particular emphasis was placed on hybridization combinations, energy performance assessments, and economic assessments of solar MD systems. The integration of various solar thermal units with membrane distillation systems, including solar flat plate collectors, evacuated tube collectors, hybrid photovoltaic/thermal collectors, high-concentrating solar collectors, salt-gradient solar ponds, and solar distillers, is investigated. Comparisons of various solar feed heating processes are critically analyzed and comprehensively tabulated. Investigated sun-based membrane distillation research, focusing on strategic approaches to develop next-generation solar membrane distillation systems capable of meeting future needs and achieving a significantly more cost-effective desalination process [10]. Photovoltaic-powered RO desalination devices remain the predominant method for solar-powered water desalination units. This approach highly reduces the electrical power consumption and cost for the required daily freshwater production per unit area of the solar field. Furthermore, the development of solar-based distillation technique is increasingly favored as an integrated system incorporating two-membrane units or a combined membrane-solar thermal or a membrane-solar-electrical hybrid system. The careful selection of seawater (high-salinity index) distillation approach needs appropriate early and final treatments resulting in thermo-economic benefits in terms of the separation process (specific and cost of freshwater yield) and energy consumption for on or off-grid operational systems [11].

Ideal growth circumstances follow from this: chilly, humid, and with great light intensity. After passing a second evaporator on the roof, heated seawater generates hot, saturated air that passes via a condenser. Saltwater pouring in cools the condenser. Due to the disparity in temperature, the air stream undergoes condensation, resulting in the formation of freshwater. Relative humidity, air temperature, solar radiation, and airflow affect the freshwater count. Enough meteorological data allows these conditions to be modeled, optimizing the design and operation for any suitable site [12,13].

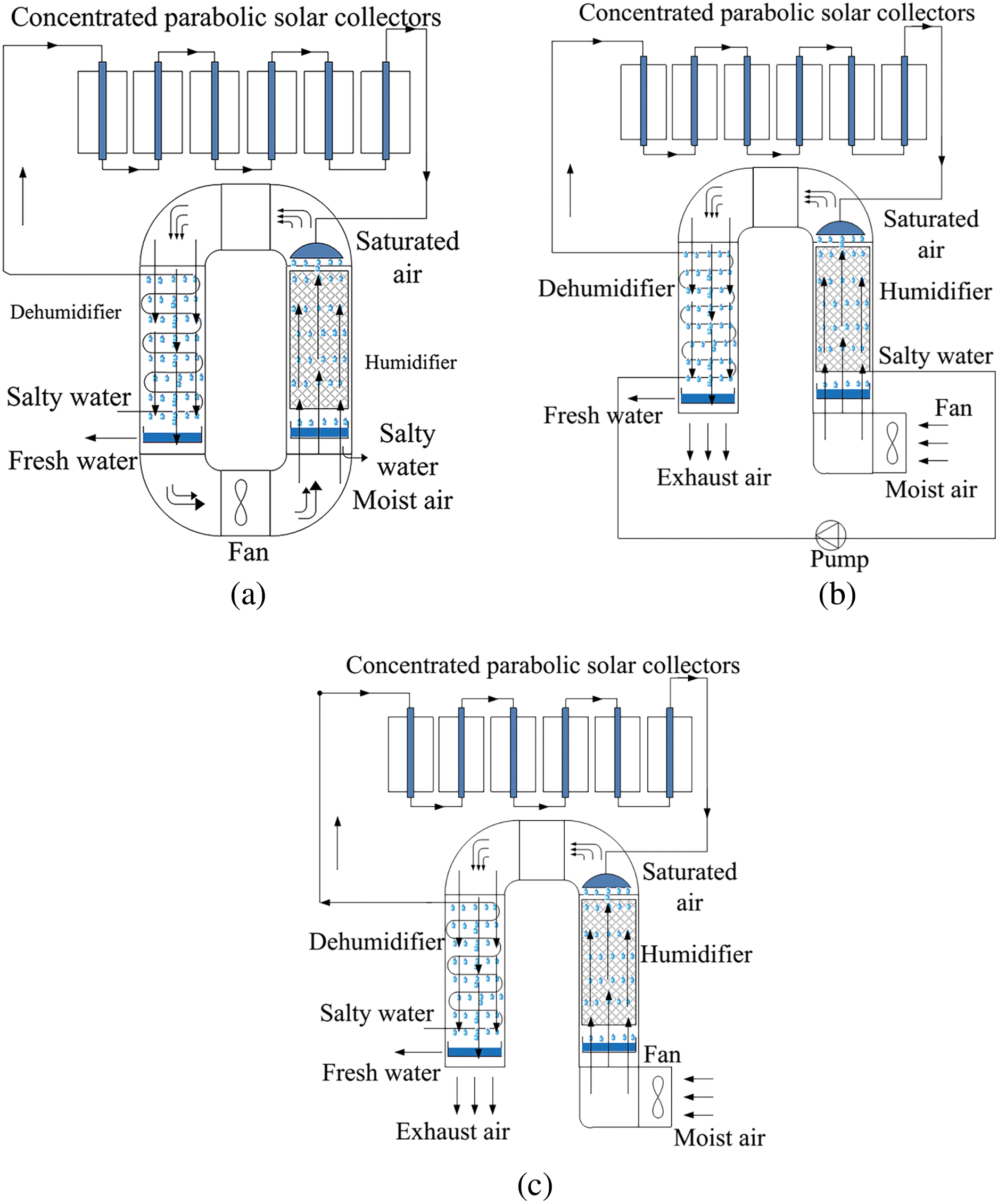

Fig. 2 shows CAOW, OAOW, and OACW cycle combinations. Closed water and air cycles increase energy recovery by preserving water/air heating input energy. The brine reduces the required energy for feed water heating, and the air preheats water in the dehumidifier. Researchers are motivated to improve systems’ efficiency due to their low freshwater yield and excessive energy employment. Thus, the following sections will explain potential solutions. HDH heats water and air to hasten evaporation. Due to water’s larger heat capacity than air, WH-HDH is expected to perform better [14].

Figure 2: A Schematic diagram of HDH system types (a) Closed-air open-water (CAOW) HDH unit, (b) Closed water open-air (CWOA) HDH unit, and (c) Open-air open-water (OAOW) HDH unit

The current work categorizes and analyzes the most recent technical developments in solar HD according to the research methodology employed. They adopted this strategy to organize the findings and better understand the research gaps in the field. This work focused on thermodynamic studies, energy analysis, modeling of HDH based on fundamental equations, analyzing the massive HDH systems based on the techno-economic view, and the areas that previous reviews often overlooked. Also, it aims to encompass all HDH system designs, demonstrating a comprehensive analysis without concentrating on renewable energy. Analyze the influence of several factors on the system’s performance, such as the inlet temperature and flow rate of the working fluids (water and air), the ambient humidity and temperature, recirculation of the brine, the design specifications for the humidifier and dehumidifier. Also, investigate and handle the most recent developments in desalination HD systems and subsystems for by-product treatment.

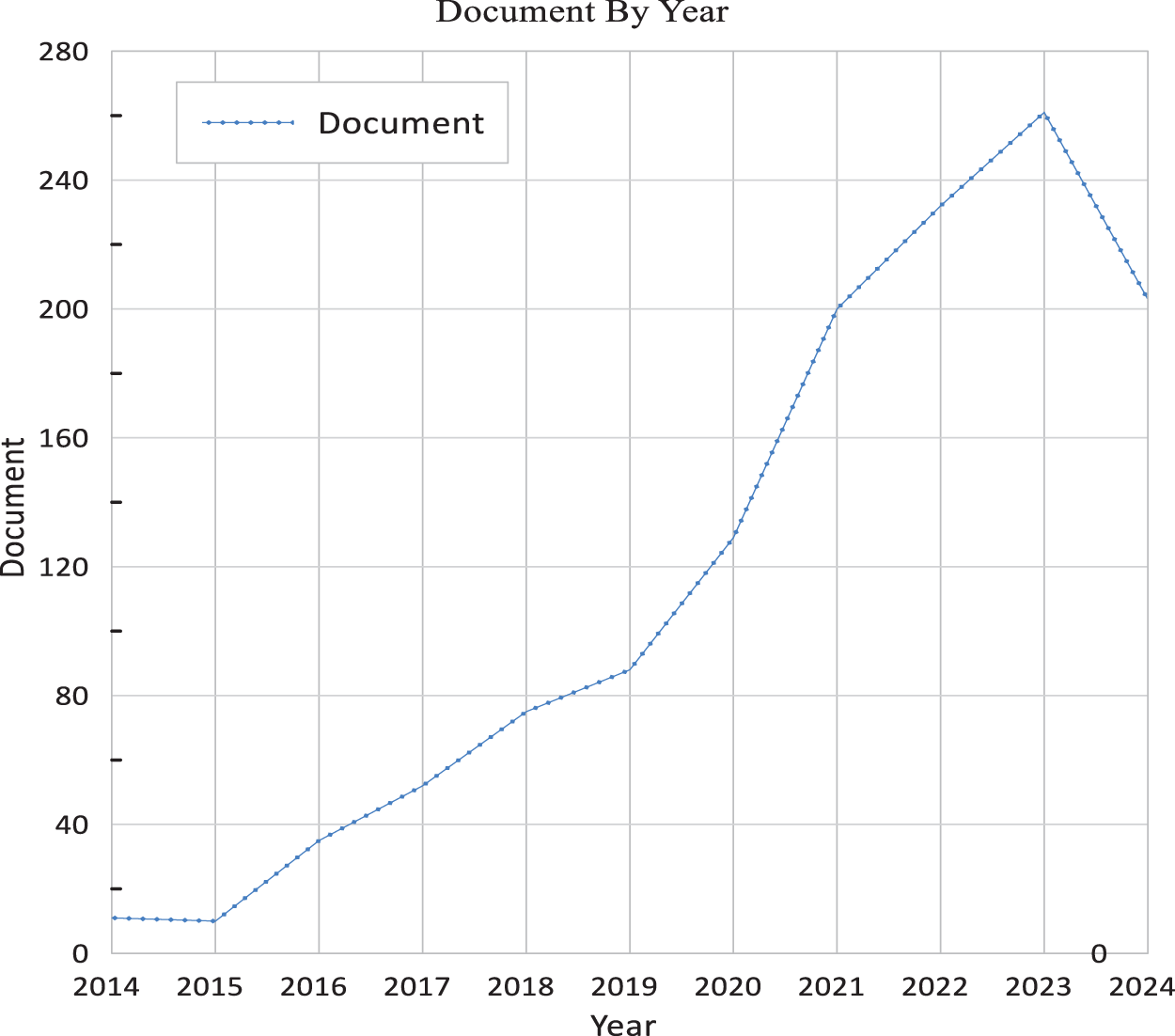

Bibliometric analysis is a statistical technique for calculating the relevant academic literature to identify the key studies [15]. Selecting the right search strategy will enable you to find several pertinent documents and employ this helpful tool. This work’s search string was created below: (Desalination, Solar desalination, Humidification-dehumidification, Solar energy, exergy) and (thermodynamics, energy destruction, and exergy efficiency). The Scopus database’s main pass of the search string contains the abstract, article title, and literature keywords, and it turned up 2157 articles. Exclusion criteria were considered to boost the analysis’s reliability. As a result, peer-reviewed journal articles written in English are considered free of time constraints. Due to this restriction, 1296 articles remain for extra processing.

In the following step, the remaining papers were thoroughly screened and built on their titles and abstracts to confirm the quality of the taster examined. As a consequence, 300 appropriate papers were chosen for the bibliometric study.

The trend in the publication of exergy analysis of Humidification-dehumidification (HDH) from 2014 to 2024 is depicted in Fig. 3. More research has been done recently, especially in the last few years, employing exergy to study the HDH systems.

Figure 3: Publication trend of exergy analysis of HHD

3 HDH System Performance Analysis

Performance improvement of the known HDH desalination systems can be accomplished by integrating them with a sustainable energy sources, adjusting the operating pressure of the processes, inserting other desalination equipment with the HDH system, improving the system key elements, and constructing combined heat pump-HDH units. So conventional HDH systems can be made better and achieve a higher freshwater yield with less power consumption, and the process or freshwater costs can be reduced. The two important performance metrics to assess HDH systems are GOR and performance ratio (PR) [16].

The parameters indicating the performance of the HD system are the recovery ratio (

One primary performance indicator in evaluating HD is the gain-output ratio (GOR). Calculated as the ratio of produced fresh water’s latent heat of vaporization to HD’s total energy input [17]:

where

A high

Compared are HDH systems using the consumption of electrical energy specific (CEES), And the comparison is made between the rate of desalination and the input electrical energy as follows:

where

3.2 Specific Production of Water

The specific water production is daily freshwater collected per square meter of collection area. This indication is usually utilized to find its efficiency when the HD runs on solar energy. Furthermore, solar collectors cost between 40% and 45% for air heating systems [18,19] and 20% and 35% for water heating systems [18–20], a capital cost analysis of HD is essential.

The higher salt rejection causes the recovery ratio (

where

3.4 Ratio of Mass flow Rate (

The performance of HD is substantially influenced by the ratio of mass flow rate (

where

3.5 Factor of Energy Reuse (

In the thermally driven water desalination system using HDH, several attempts have been made to recover heat to minimize energy costs. The energy reuse factor, represented by the symbol ‘

where V represents the vapor loading, expressed in moles of water vapor per mole of carrier gas.

3.6 Generation of Specific Entropy

The total production of specific entropy (

where

Consider that the performance metrics acquired employ either experimental or theoretical investigation to assess the system without considering the energy loss from the system by the process or components. Thus, exergy analysis energy is accessible and can be used on these systems to finish the performance evaluation. Exergy is the most helpful work in a system, and it may be obtained using a heat reservoir toward system equilibrium. Exergy is the capability of a system to induce a change when it approaches equilibrium with its surroundings. Exergy is lost when a process includes pressure, temperature, and humidity variations, unlike energy always maintained during a process. The destruction is commensurate with the system’s and its surrounds’ entropy generation. According to the exergy efficiency, irreversibility destroys part of the exergy entering a system, combining electricity, fuel, and a moving stream of matter.

The exergy rate balance for a control volume for an HDH system under a steady state situation and by eliminating the potential and kinetic energy is given as:

The expression

Furthermore, the expression

The system parts receiving exergies and thermal energy from inlet streaming entry improve the exergy content. In contrast, outlet flows, and consumed electricity reduce the exergy content. The variations in exergy content result in the positive or negative signs of the variables in Eq. (8).

The expression

Physical exergy is the work that can be extracted by transitioning the material through a reversible process from its original state (

When a material is brought from the surrounding state (

where

The fundamental exergy equations for humid air and saline water are delineated as [26]:

where

The exergy of solar radiation is computed from the Petela equation as:

where

Exergy analysis requires a suitable dead state that coincides with the equilibrium of humid air, a mixture of dry air and water. Under normal atmospheric conditions

The decreased exergy efficiency of an operation illustrates the deterioration of various energies since the thermodynamic irreversibility via any action marks the direction of degradation.

Exergy economic analysis is yet another helpful tool for assessing desalination plants. Calculating every stream’s exergetic and financial cost helps one integrate exergy with cost analysis. Formulated for every component of the system is a cost balance equation. Exergy economic cost balances reflect the cost of all resources entering a component (either in the form of cost connected with the exergy flows into the component or capital cost) with those departing the same component. General component equations are stated and calculated as [29]:

where

where the capital investment cost of component

One should observe that reduced water cost results from increased GOR, PR, and exergy efficiency. Designing high-efficiency components and modifying the operational parameters (inlet water and air temperatures and their mass flow rates) helps one to accomplish this.

The traditional HDH desalination system consists of a dehumidifier, a humidifier, and fluid transfer components such as fans and pumps. A humidifier is a device where evaporated saline water interacts with an air stream or other carrier gases such as argon, helium, or carbon dioxide [30]. The humidifier functions analogously to a cooling tower. Conventionally, both the dehumidifier and humidifier operate at atmospheric pressure. Water evaporates into the air to achieve saturation. The humidifier equipment may contain a packed bed with various types of packing, a spray tower, or bubble and wetted wall columns. All humidifier designs aim to increase the moisture content of the outgoing air. It is important to note that the release of latent heat from water vapor upon contact with the process air causes a reduction in water temperature and a decrease in the temperature of the process air. Preheating the process air and saline water is employed to alleviate this impact.

5 The Relevance of Humidifiers and Dehumidifiers on the HDH Desalination Process

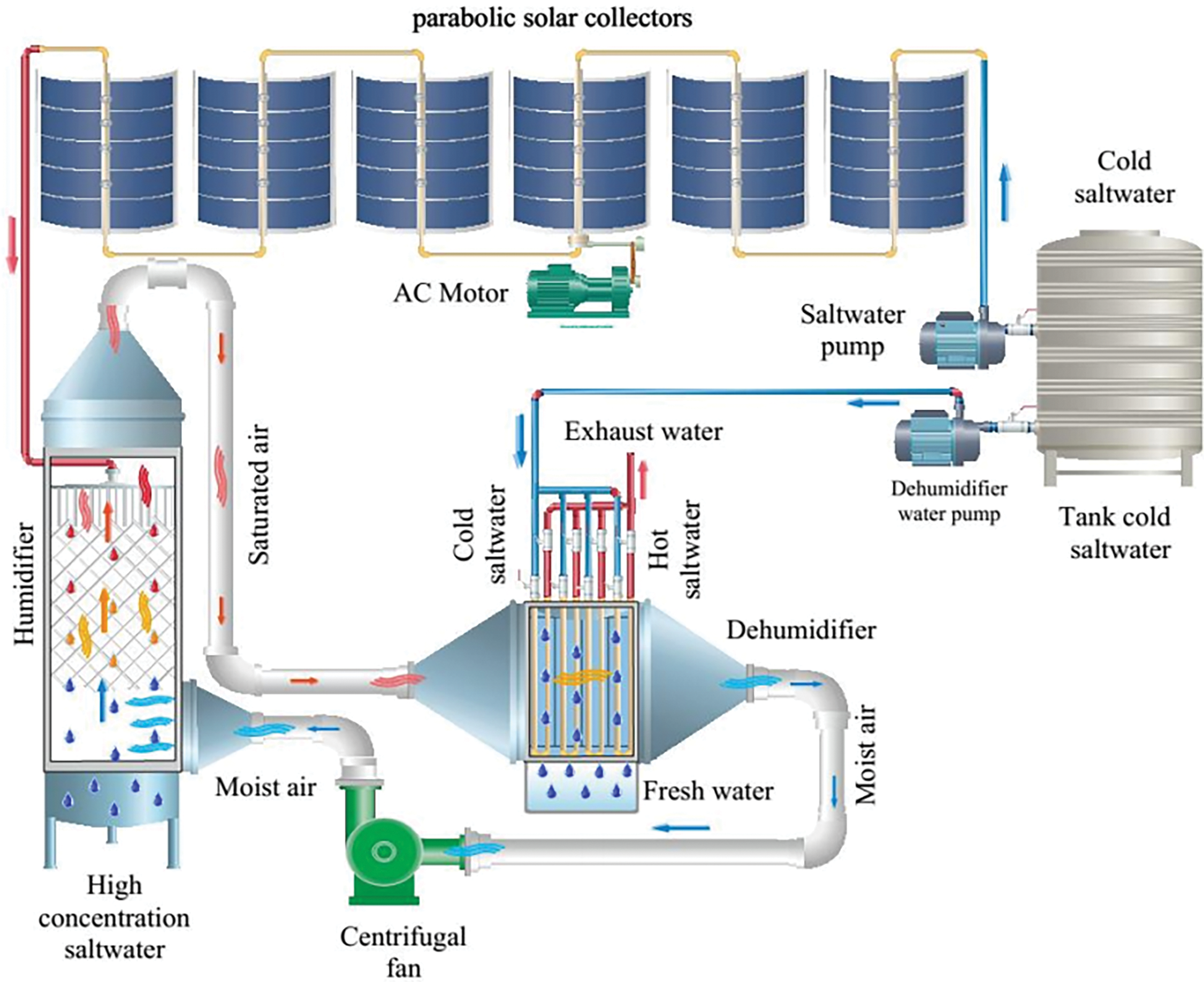

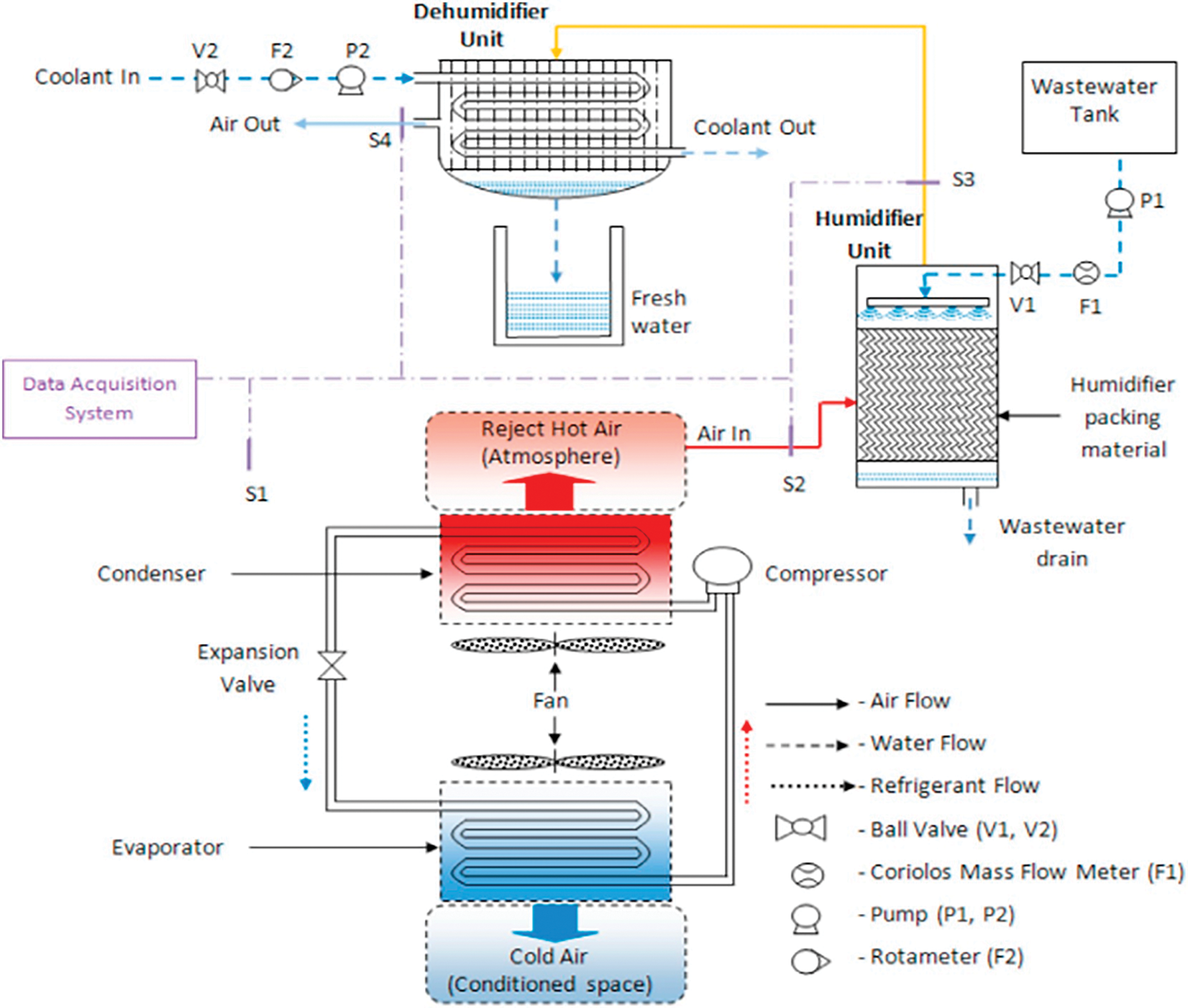

Mostly popular among various designs is a basic closed-air open-water (CAOW) HDH system [19]. As Fig. 4 shows, the system comprises two main parts: a humidifier and a dehumidifier. The humidifier unit helps to humidify through a basic spray-sort or more effective structure-packed bed that facilitates evaporation of feed water on interplay for the air middle. The humidified air is then sent into the dehumidifier unit, where contact with the low-temperature coolant through the tubes causes the water vapor to condense into freshwater. Freshwater and brine collecting systems are at the base of both the humidifier unit and the dehumidifier unit.

Figure 4: Schematic of a simple humidification and dehumidification desalination process

A pump and a fan preserve the intended water and air flow rate over the system. Improvements in system efficiency are achieved using water [31], air [32], or both [33] methods of fluid preheating, humidification for multi-stage, and dehumidification for multi-stage [34]. Of the previously listed techniques for improvement, fluid preheating is considered a dependable method for improving environmental compatibility, economic efficiency, and energy consumption [35,36]. HDH technology is preferred for local freshwater production as it is compatible with waste heat energy or sustainable solar energy for preheating [37]. Due to its low cost and wide access comparison with other sources of renewable energy, solar energy has become very important in the preheating process [38]. Likewise, heat waste has become the most crucial method for desalination in the past ten years since it is required to identify sustainable and effective methods for heat waste usage that lower the effect on the surroundings [39]. An experimental investigation was conducted using a parabolic trough collector (PTC) on the HD desalination system. The HD system in Baghdad, Iraq, consists of six PTCs with a total aperture area of 8.772 m2, a humidifier part, a dehumidifier part, and a system for tracking. The results suggest that the highest amount of freshwater produced daily is around 6.37 L, operating for 6 h daily. On average, the productivity is 1.062 L per hour when the flow rate of salty water is 1 L per minute. The OWCA circuit is the most efficient configuration [40].

Interestingly, the individual evaporation (humidification) and condensation (dehumidification) process capacities of the HDH system determine its whole performance. A suitable HDH procedure depends on the proper choice of humidifier and dehumidifier [41,42]. The selection of humidifier material considers the elements of Surface contact area, water retention capacity, contact time, and cost to provide an efficient heat–mass transfer mechanism during humidity. Likewise, effective extraction of the latent heat energy from the humidified air for a dehumidifier depends on a good design and suitable material to generate the required volume of freshwater. The current study aims to investigate the specific humidification and dehumidification methods used in the HDH desalination system, which runs on potential solar and heat waste energy. The focus is on understanding how these approaches enhance the overall system’s efficiency. Two main features of a humidifier are specific surface area [43] and strong absorption/adsorption capability [44]. Analogous for a dehumidifier include its design [45], material [46], and contact surface area [47]. Furthermore, influencing the HMT properties throughout the operation are optimized temperature and flow rate of water and air [48]. The humidification process is influenced by the amount of water vapor in the air, the difference in concentration at the interface, and the difference in temperature between them [18]. The preheating approach maximizes the disparity in the attributes mentioned above. In the humidification process, the temperature of either water [49], air [50], or both fluids [33] is increased to reach the highest saturation. Additionally, it was shown that the air velocity only had an impact when the intake water temperatures were lower [51]. Reference [52] investigated the exergy consumption of an HD system combined with a pall rings humidifier part. It was found that the length and entering air temperature of the humidifier unit dropped as its diameter climbed and that the exergy efficiency increased. In an experimental context, Reference [53] examined the performance of a solar HD unit in an experimental environment furnished with a fabric humidifier. With ambient temperature and wind speed having little effect, the distillation rate mostly relied on system properties (e.g., feed and air input temperatures/flow rates). Elucidated a solar desalination technique cycle multiple condensation evaporation, utilizing a thorn tree humidifier. Their water input temperature much more impacted the freshwater output of the humidifier and dehumidifier machines than other factors [54].

Another type of humidifier is a spray tower. Water is distributed down from spray nozzles in a cylindrical construction where air flows upward. Though the humidifier may contain a lot of water and air, the decrease in pressure is negligible on the air side. The little contact time between the air and the water stream limits the efficiency of the humidifier [55].

Furthermore, related to reduced mass and heat transfer coefficients rather than forced draught air flow, HD systems utilize natural draught inside the system to circulate air. Usually, aerial water vapor is condensed, and latent condensation is recovered using film condensation over metallic tubes. A tremendous metallic surface area is often required because of the low heat transmission rate, which increases the system’s cost. Although further system efficiency is necessary to lower capital costs, solar HD technologies show tremendous possibilities for distributed small-scale water production applications [56].

Nevertheless, this method has significant drawbacks, such as its suboptimal effectiveness caused by its limited ability to retain water owing to loosely packed flow and the necessity for mist eliminators to prevent water from being carried away at the humidifier outlet. Spray nozzles additionally enhance the pressure differential over the water channel. The HDH desalination technique uses packing materials within the humidifier that boost the time period of air-water interaction [57]. This enhances the efficiency of heat and mass transmission, which underpins the HDH desalination process, as well as humidification efficiency. In other words, HDH efficiency depends much on the packing material of the humidifier. Dehumidifiers differ from humidifiers because they are heat exchangers with intricate shapes. Their physical composition significantly influences the features of HMT (humidity and moisture transfer) during dehumidification [58,59]. The design, size, and material selection depend on the specific system and method [22].

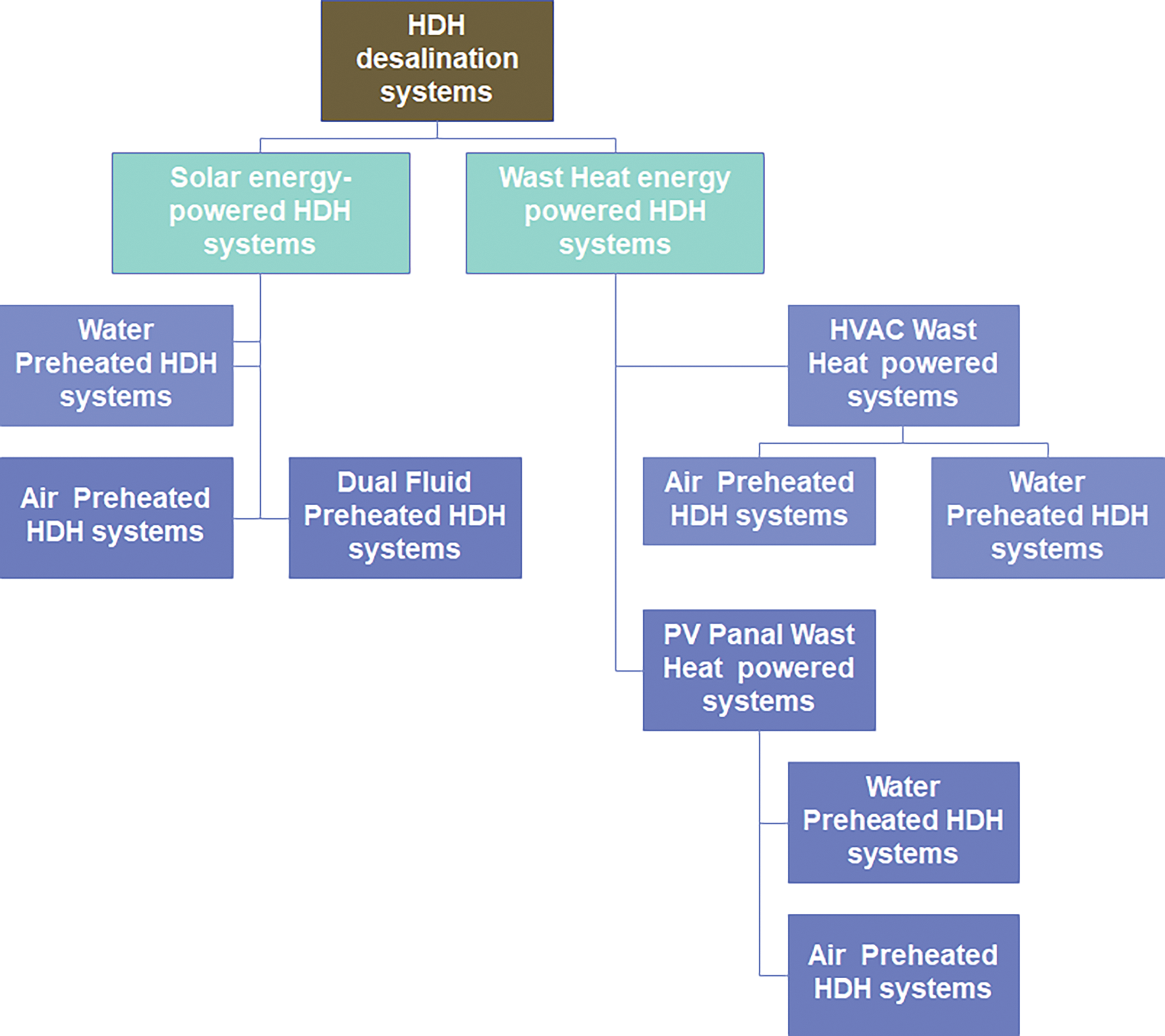

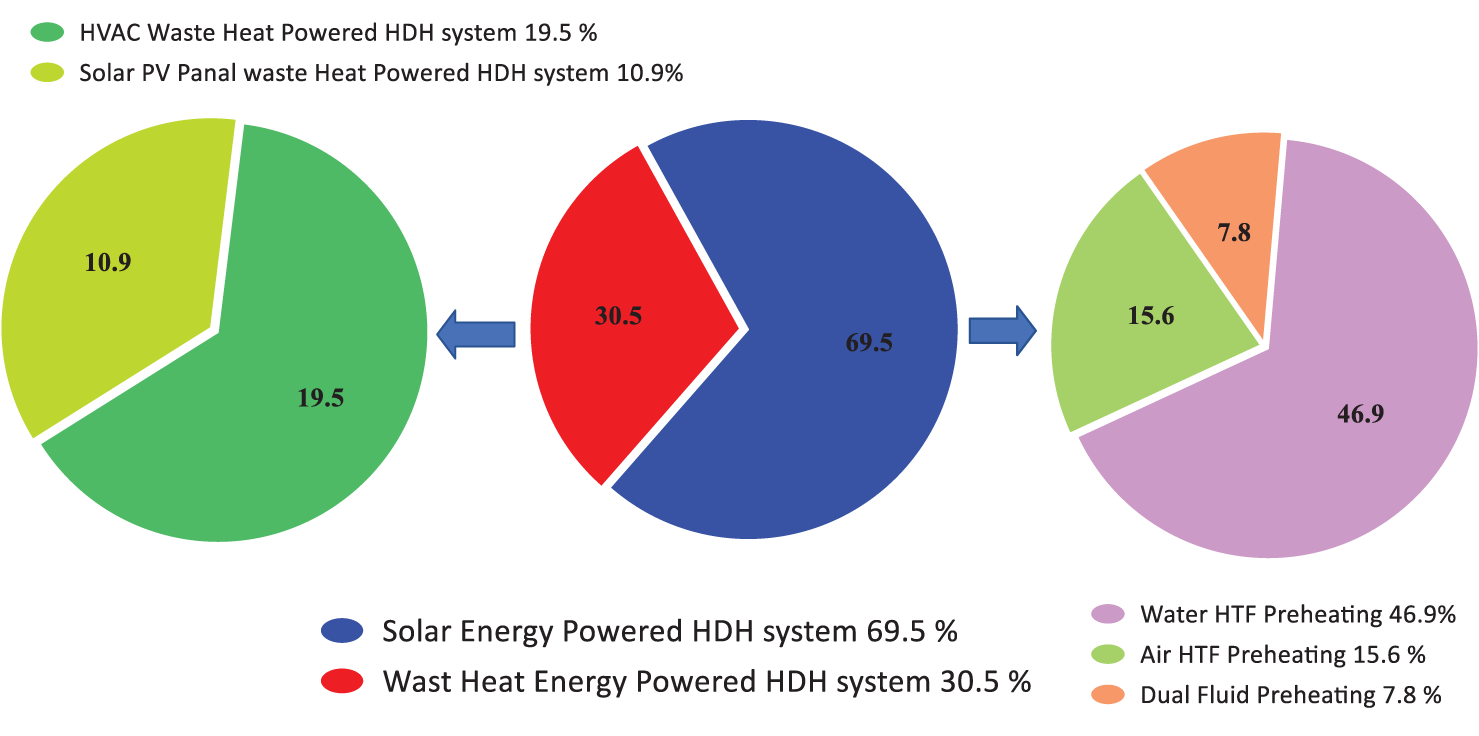

Additionally, the dehumidifier’s performance is influenced by the coolant’s mass flow rate and intake temperature [60]. This study investigates the many methods used to improve the efficiency of HDH-desalination systems using solar and heat waste energy. This research focuses on the various humidifier and dehumidifier approaches used in recent years. Studies on HDH desalination techniques concentrate only on humidifiers [61] and several kinds of renewable energy for running [36]. To improve system performance, however, it is practically necessary to determine the effective mix of dehumidifiers and humidifiers under suitable working circumstances. Unlike earlier studies on large-scale desalination techniques, the present work concentrates on HDH techniques for desalination designed for residential freshwater of decentralized generation. The study works are classified according to the kind of fluid used for preheating, which includes water and air heating and heating-dual-fluid HDH systems, as seen in Fig. 5. Among them also pay attention to co-generation techniques [62–65] and energy recovery [66].

Figure 5: Classify HDH systems powered by heat waste and solar energy

Depending on the air circulation, the HD desalination system might run in forced or natural draft mode. The dehumidifier part comprises one single duct, which houses the condenser and creates unsaturated air. An atomizer flashes salt water within the part humidifier, producing tiny droplets. It maximizes the surface area of interaction between the surrounding air and the flashed salt water [55]. Any packing material that effectively humidifies the air in another duct is a humidifier that delivers saturated air. To optimize system efficiency, the air and (or) water are heated using several energy sources, including solar, hybrid, geothermal, and thermal energy. HDH systems are classified based on their sources of energy, the cycles of air and water circulation, and the sources of water and (or) air heating [67]. The innovative HD of air technologies [38] does not depend on high temperatures. Every thermal energy required in these systems may come from solar energy [68]. Solar HD desalination systems’ effectiveness in providing clean water to remote locations [68] is well-known. Although HD systems have simple operating and design, their low thermal energy efficiency is a main drawback. Usually, inadequate thermodynamic feasibility of low-grade heat accounts for the poor thermal efficiency of HD systems.

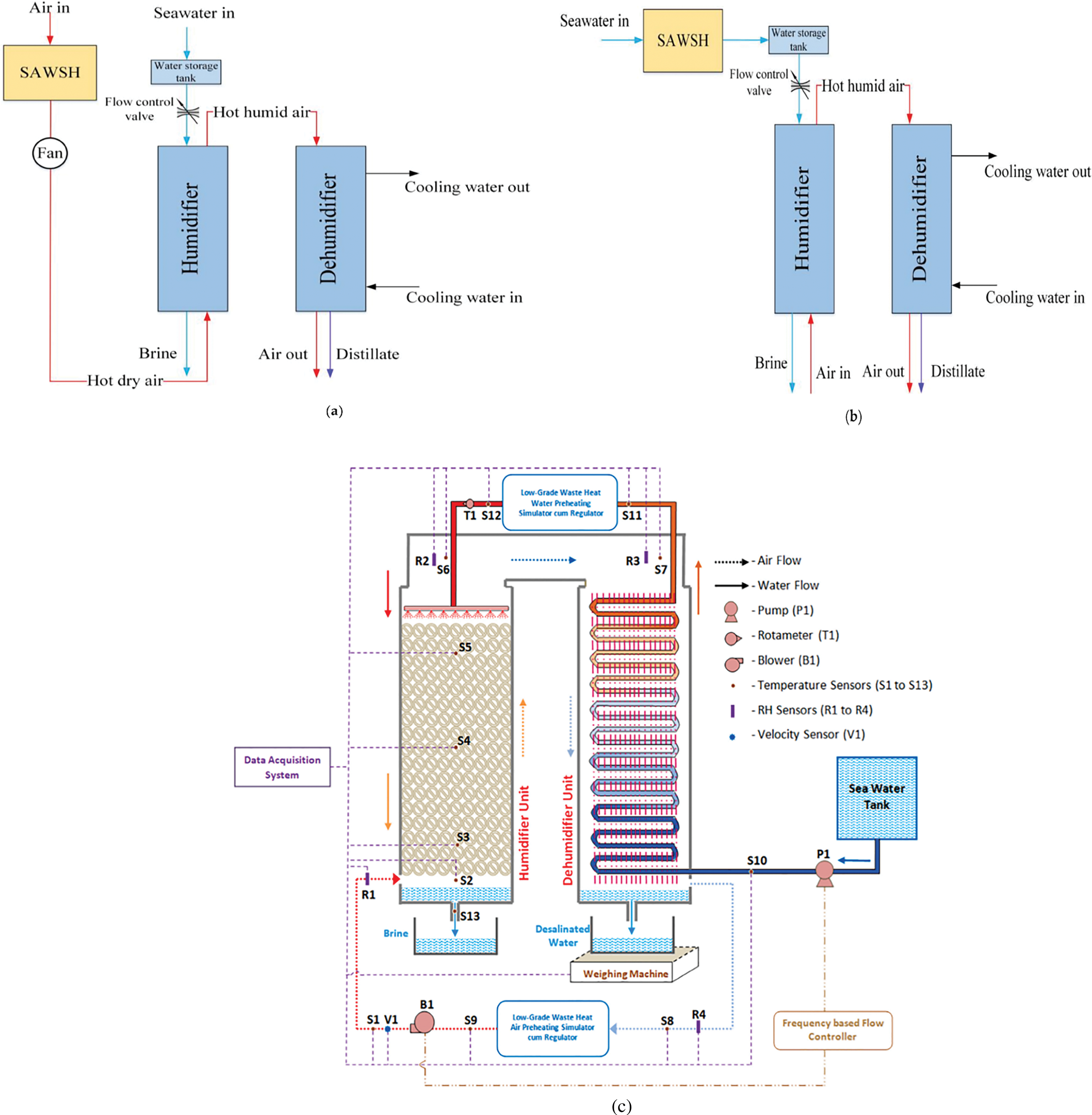

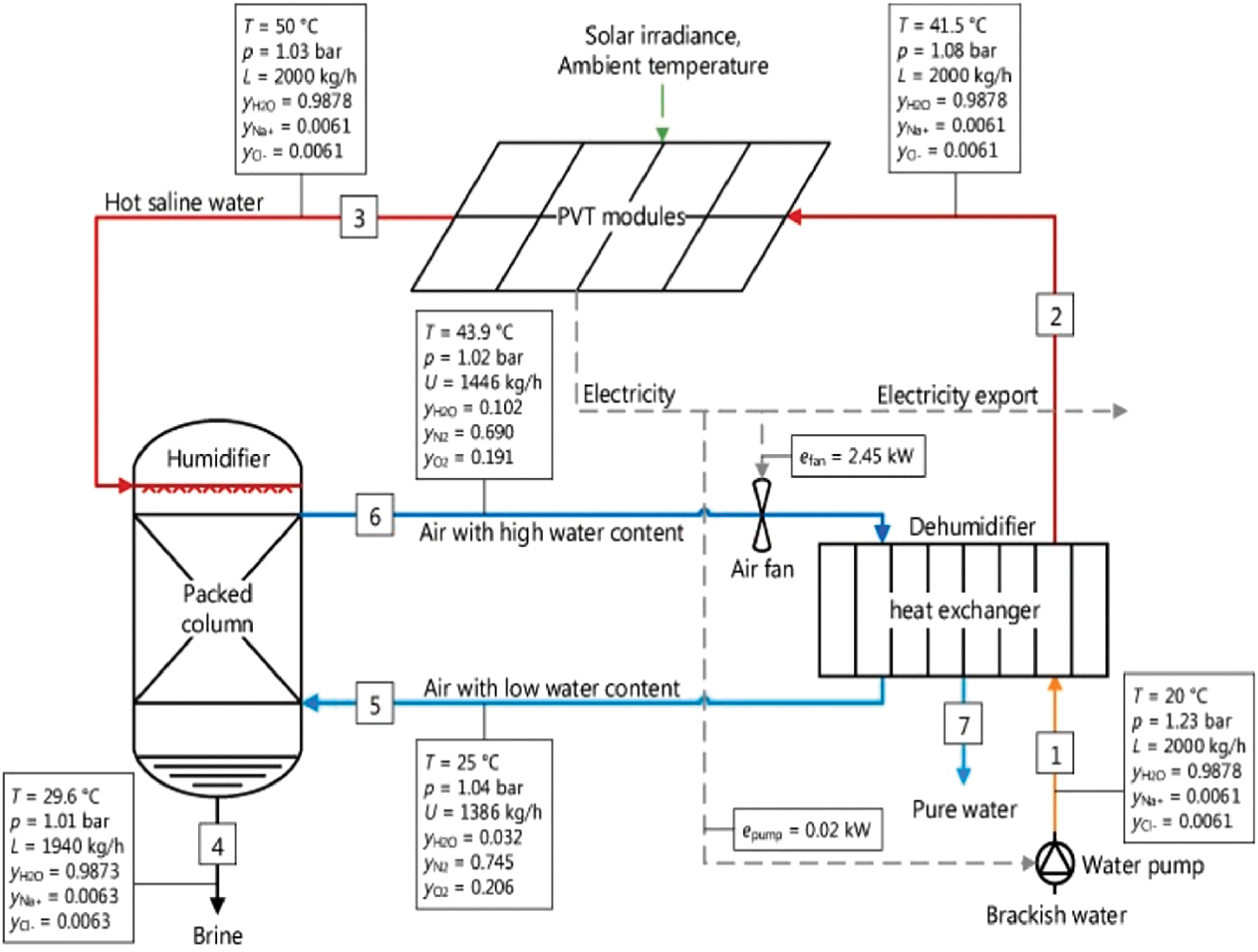

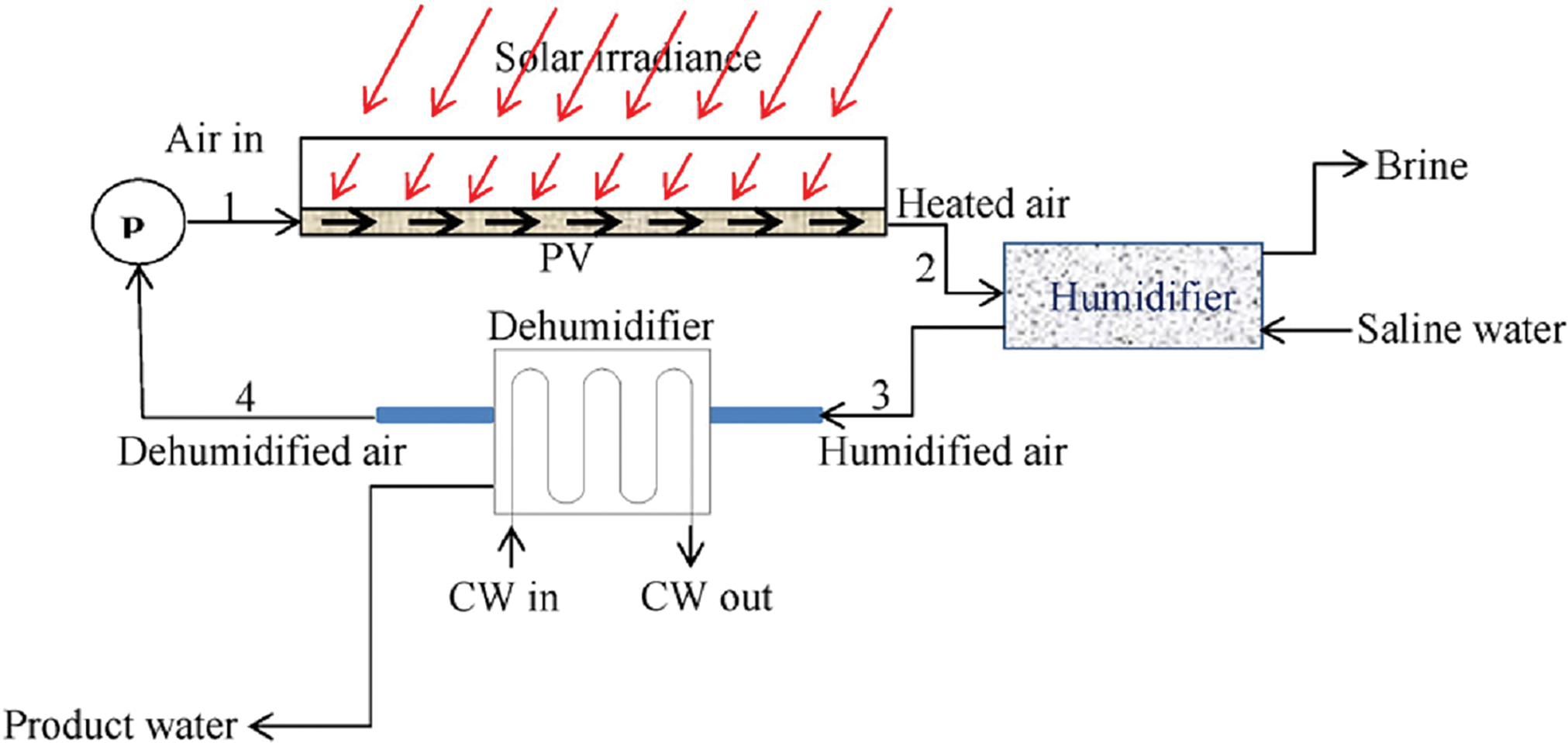

Still, reaching complete efficiency to produce enough steady freshwater is elusive. Thus, the current evaluation will help select, design, and improve HDH systems by employing appropriate materials for dehumidifier and humidifier systems to optimize efficiency. A typical schematic of air-heating, water-heating, and heating dual-fluid HDH systems driven by waste heat energy and solar is shown in Fig. 6. The technique of the working fluid being preheating (air/or water) is the significant distinction between the three distinct systems. The HDH unit receives seawater through the dehumidifier inlet Fig. 6a and heats it using either solar collectors of water or heat waste energy. The warmed seawater is then discharged through the dehumidifier outlet. The preheating process increases the fluid’s thermal energy and the latent heat the dehumidifier produces during condensation, enhancing the humidifier unit’s humidification efficacy during the interaction between water and air. The inlet air flowing into the humidifier is heated using a solar air collector (or waste heat energy) for air-preheated systems, as shown in Fig. 6b. Though air has a lesser heat capacity than water, an air-preheating system uses air because air, when at high temperatures, can hold more moisture than air at low temperatures [69]. Thus, increased water vapor from the hot air interacts with the water in the humidifier part, and the water reaches the condensation process in the dehumidifier part. Because the previous close-air mechanism in HDH systems has better thermal efficiency than the open-air mechanism [70], it is favored in these systems. The air and water preheating systems are preheated for the dual-fluid, circulated via the humidifier part intake and the dehumidifier part output to enhance mass and heat transfer during humidification, increasing freshwater production during dehumidification. Water and air are preheated with the relevant water collector and solar air (or) heat waste energy, as indicated in Fig. 6c.

Figure 6: The schematic illustrates the solar and heat waste energy powered (a) water-heated, (b) air-heated, and (c) dual fluid-heated HDH systems [69,70]

An energy and exergy analysis for a process exceptionally defines how efficient it is. Integrating thermodynamics rules enhances process quality and maximizes system work by comparing it with the reference case. The energy balance offers critical insights into the system’s condition and the unit’s losses. It fails to distinguish between energy kinds and does not account for losses resulting from declining energy quality.

The detailed mass and energy balance equations, humid air specific enthalpy, water vapor pressure, saline water specific enthalpies, and the purity of desalinated water are outlined as given below [71,72]:

The specific enthalpy of a mixture of dry air and water vapor is evaluated as:

The absolute humidity can be calculated per Grosvenor relation (Eq. (22)):

It is related to vapor pressure and atmospheric pressure. The water vapor pressure is calculated by Antoine relation (Eq. (23)) [73]:

The specific enthalpy of distilled and saline water using Eqs. (24) and (25), respectively.

Solar air and water heaters’ general energy balance equations are stated as follows:

The solar collector’s effective heat gain is related to the heat removal factor

The computation of the collectors’ heat gain incorporates its loss of energy

Due to the existence of driven forces, an analysis of HDH systems employing exergy losses was conducted [75]. Applying the sink-source idea, one was thinking about a shift in the humid air concentration. The results indicated that heat transfer significantly contributed to the irreversibility of the system, while mass transfer had no impact on loss of exergy. The HDH system reported a decrease in exergy efficiency, similar to heaters, which exhibited the highest irreversibility. Systems of WH-HDH and AH-HDH were examined in terms of exergy loss. It is observed that when water at low temperatures entered the humidifier in the WH-HDH system, a high level of irreversibility was reported. Air exits from the humidifier and the dehumidifier was considered to be saturated. Inefficiencies of the components might prevent these streams from being saturated. Theoretical and experimental findings so differed significantly.

An exergetic investigation of a solar-integrated AH-HDH plant was achieved [74]. By constructing an appropriate humidifier 0.2 ID × 2 m, optimal production and total exergy efficiency were attained. Applying the energy balance principle to liquid and gas streams and moisture accurately predicted the humidifier’s thermal stress. The total exergy efficiency improved due to a decrease in humidifier axial length and temperature of intake air with the increase of humidifier diameter. The air reached saturation at a specific humidifier length; hence, no more variation in total exergy efficiency was noted beyond this length. In outdoor dynamic tests of solar-assisted HDH systems, fluctuations in the air’s ambient temperature and absolute humidity are reported; nevertheless, the reference (dead) state is a permanent value. The selection of an appropriate dead state might enhance the reliability of results since these factors influence chemical exergy [76].

Dehumidifier performance in an MS-HDH was assessed [77]. Two phases of dehumidification were done using both regular and cold cooling water. With 0.066 kW loss of exergy, the first dehumidifier deduced maximum exergy efficiency. The exergy efficiency increases as the water flow rate increases. For standard and chilled water, the ideal values of input and air-cooling temperatures were found at 25°C–32°C and 13°C–25°C. The strength of this work was the parametric investigation using exergy analysis; the shortcoming of this work may be seen as a disregard for chemical exergy. Future research should consider optimization using the optimization program following the identification of essential parameters via parametric investigation.

The exergetic efficiencies of WH-ME-HDH components were calculated based on humidifier air outlet temperature, salinity, irradiation, (a/w) flow rate ratio, water flow rate and temperature, and solar intensity [78]. The results showed that increasing the (a/w) ratio improved the exergitic efficiency of the HDH system. The reason was a rise in stream input exergy. Reducing and raising the input air temperature helped to increase the exergy efficiencies of the HDH correspondingly. The decrease and increase in exergy degradation at high-level temperatures are attributed to their conceptual performances. The advancement of pinch technology will aid in completing this research. The freed energy from the components enables high energy recovery from the heated process fluids.

A desalination (AH-HDH) system was assessed with a solar-powered air heater incorporating three types of turbulators: twisted tape, conical inserts, and semi-circular perforated disc inserts. The heat transfer rate was analyzed for 3, 4, and 5 pitch ratios to enhance the solar air heater’s performance. Packing materials specified by their capacity for moisture absorptance, such as (sawdust and gunny bag) are utilized in the humidifier to improve the rate of water evaporation since the air-water time contact is more extended. Furthermore, spring inserts were used in the condenser (or the dehumidifier) to enhance the condensation rate since they deform the fluid flow pattern. Comparing the HDH system specified by augmenting the humidifier with moisture absorptance material (gunny bag) and aided by an air heater inserted with turbulators (twisted tape) with conventional HDH (as a reference) resulted in improvement in freshwater yield (100%) thermal (12%), and exergy efficiencies (150%) [79]. A thorough thermodynamic analysis accounting for all related variables affecting HDH processes will enhance performance and expand recovery of energy.

The effectiveness of a cogeneration unit utilizing a combination of AH-HDH and concentrated hybrid thermal/photovoltaic collectors has been assessed [29]. A detailed performance evaluation was conducted through microscopic modeling of the hybrid collector, involving exergy/economic analysis and salinity variations in both brine and freshwater. Further information on the hybrid collector’s performance and the application of the pinch technique are required for the proposed design. The results indicated the system could generate 12 m3 of desalinated water annually and 960 kWh of power. A unit electricity generation costs were evaluated at 0.289 $/kWh, while the desalination rate was determined to be 0.01 $/L. Utilizing the thermal and electrical energy generated from the hybrid PV/T collector for fluid heating or powering system components would improve the system’s overall efficiency.

The exergy, energy, and economic/environmental impact of the air and WH-HDH-PV plant were investigated [80]. The proposed system’s predicted maximum daily energy and exergy efficiencies were approximately 31.50% and 1.91%, respectively. The optimal exergy efficiency for their system occurred between 13:00 and 18:00, attributed to substantial thermal storage in the components during this period. The desalination rate, cost per liter (CPL), and environmental-economic parameters were determined to be around 1.119 lph, 0.0989 $, and 2.4039 $/year, respectively. The hourly variation in ambient temperature, wind speed, and incident solar intensity affects the performance of PV panels. Its’ exergy efficiency decreased throughout the day test hours as the panel rear surface temperature increased. Selecting an appropriate dead state is related to these variations and influences the chemical and total exergy.

Given that exergy deterioration correlates with entropy creation, it is anticipated that optimizing exergy efficiency will result in minimal specific entropy generation, hence reducing the necessary heat for separation. Entropy is produced by discharged streams when they transition from a dynamic state to an equilibrium one. This section summarizes the minimal investigations conducted in this field.

An entropy study of an HDH cycle aimed at lowering specifically generated entropy may enhance component performance [25]. The results showed that maximizing the (GOR) is proportional to minimizing entropy production. At a given water/air flow ratio, the lowest entropy production and highest GOR were defined. One restrictive component in each cycle could not be significantly improved, while a second component became the focus of efforts to reduce entropy production. Analysis of exergy did not provide definitive results for the on-design HDH cycle. Research on entropy generation highlights the impact of irreversibility on the minimum energy required for the extraction of salt from saline water. Reference [81] aimed to evaluate the least amount of labor needed to produce freshwater, excluding hot freshwater. Irreversibility results from the wasted work mixing brine and salty water in a dead state, and the discharge stream’s temperature balance. The thermal imbalance in the discharge fluid streams was a major contributor to entropy generation for the various covered desalination methods (RO, MSF, MD, MEH, and HDH).

In contrast, chemical non-equilibrium played a critical role in high recovery-ratio techniques. Electrical energy was more efficient than thermal energy, and entropy generation was higher during the conversion of heat to electricity. The lack of understanding of entropy development in renewable energy-driven HDH systems is also highlighted.

In summary, studying the HDH system processes, based on thermodynamics second law, provides a practical approach to improving their performance. The systems can be analyzed by developing macroscopic or microscopic equations for energy and continuity foundations. Factors such as the vapor concentration in humid air, components’ size, thermal efficiencies (including heat gained and lost), input electrical and thermal energy, and fluid flow rates influence the system’s thermodynamic performance. It is highly recommended to implement raising the temperature of circulating fluids in the humidifier, lowering the cooling fluid temperature in the dehumidifier, thermally insulating all the system elements, inserting heaters with turbulators, circulating the fluids at the optimum mass flow rates, and adopting the pinch technique in multi-effect processes. These procedures enhance energy efficiency, reduce irreversibility, and lower operational energy input. Further research is needed to optimize parameters, integrate high-efficiency components, and utilize pinch technologies, thereby improving the comparability of HDH systems by clarifying the system’s total exergy.

7 Investigation of Thermodynamics Predicated on Energy Analysis

The early 1960s HDH method relied on hot and cold source stability, which limited it. System performance is assessed after many revisions. Due to the lack and high prices of conventional fuel, HDH systems assisted by fossil fuel were replaced by sustainable energy resources; solar, geothermal, wind, and waste heat sources modify HDH systems to address the challenges posed by low temperatures [82].

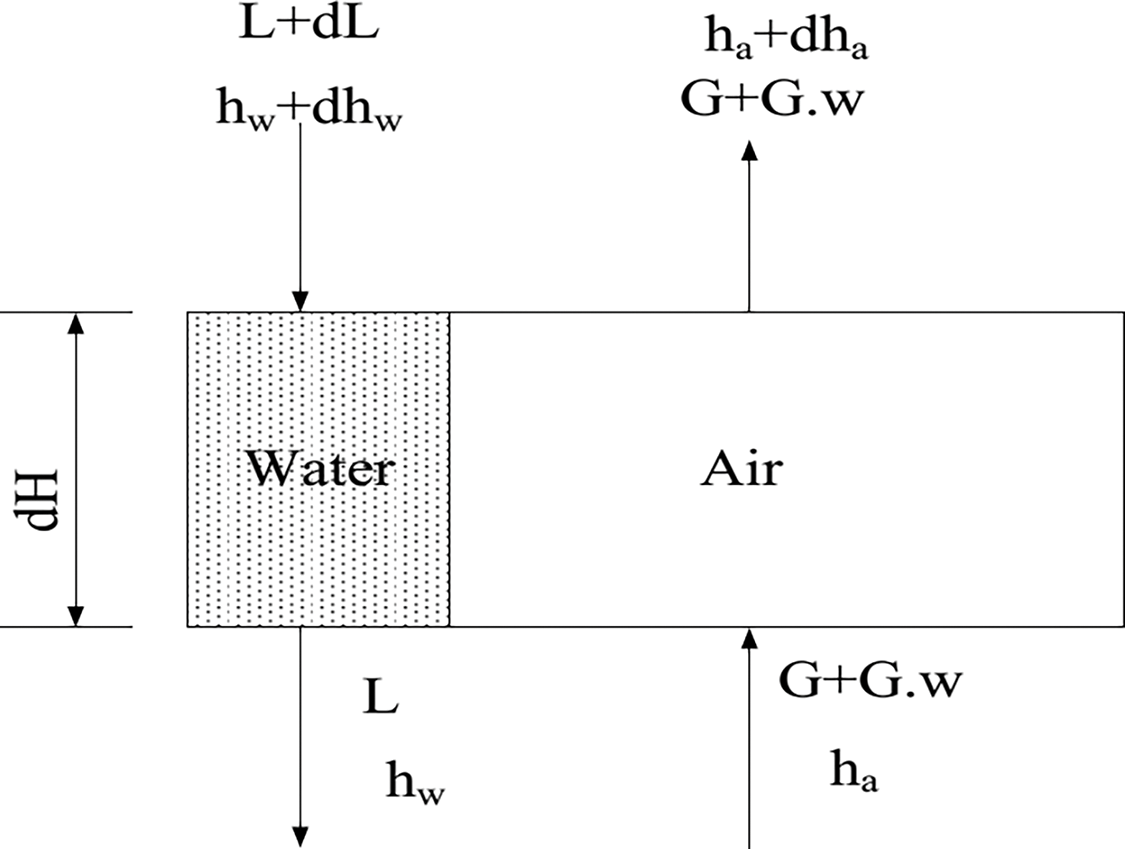

7.1 Thermal Analysis of the Humidifier

Humidifiers in HDH systems must be carefully designed to achieve optimal outlet air saturation while minimizing their size. Examples include ultrasonic humidifiers, packed beds with diverse materials, bubble columns, and spray towers. All of these designs increase contact duration and mass/heat transmission. Salty water spraying in the humidifier causes packings to accumulate water or clog bubble columns or sprayer nozzle holes. Heat/Mass transfer coefficients decline due to cleaning difficulties and maintenance costs. Here are packed bed humidifier design formulae. The humidifier is discretized in Fig. 7. Each humidifier element’s mass and energy balance equations are solved concurrently [83].

Figure 7: Exchange of mass and energy through humidifier control volume

This element’s mass-energy equations are:

Note that Eq. (29) considers ambient heat loss and insulating thickness. Eq. (30) is derived from the liquid phase energy balance equation:

where:

Properly selecting packaging material is crucial for high energy efficiency. Reference [84] conducted a parametric analysis on a WH-HDH system with corrugated aluminum-sheets in the humidifier (cross-properly selecting packing material is crucial for high energy efficiency. Reference [84] conducted a parametric analysis on a WH-HDH system with (0.4225 m2 cross-sectional area and 0.65 m height) of wavy aluminum-sheets as a packing pad in the humidifier. The corrugated type was chosen over the honeycomb kind (cellulosic paper) because of its greater surface area and longer contact duration, resulting in lower pressure-drop and higher evaporation and heat transfer rate in the humidifier. Results showed a boosted freshwater yield for higher water and air flow rates and temperatures. However, raising air temperature increased production somewhat. Energy sources and heating equipment affect feed water temperature, productivity, and cost. Instead of focusing on productivity, it analyses the system using energy sources and GOR. The efficacy of a tubular spray (0.3 m Interior diameter and 4 m height) was compared with a packing pad of (0.2475 m2 rectangular cross-sectional area and 0.1 m thickness). The same productivity was obtained for pad-type and spray-type humidifiers at a thickness of 100 mm. However, pad packing at a thickness of 300 mm exhibited a superior evaporation-rate for elevated values of (a/w) ratios [85]. One may extend the work by doing parametric investigation and CFD simulation.

A small, lightweight WH-HDH humidifier with good efficacy and low energy consumption is studied [86]. For ventilation, a humidifier with vertically aligned strings with a 6.35 cm inner diameter exhibited approximately 50°C top brine temperature TBT owing to its improved heat and mass transfer capabilities attributed to its high specific area. The proposed humidifier increased evaporation five times above the spray tower and the packed bed. Straight gas flow channels reduced pressure drop. GOR determination and process optimization and demonstrated the new design’s advantages.

A membrane HDH humidifier of (0.59 m2) area, assisted by an evacuated-tube solar water heater and finned tube heat exchanger (42 tubes of 9.52 mm OD), is simulated [87]. The suggested humidifier uses a hollow fiber membrane to satisfy drinking water standards. Successful tools to replicate the humidifier with the crossflow hollow fiber membrane and finned tube heat exchanger were found to be the parallel-plates humidifier channel analyzed by ε-NTU models. With a 30% packing fraction, one obtained the least SEEC (stands for specific electrical energy consumption) and highest desalination rate. Usually, humidifiers were replaced by membrane humidifiers. The SEEC is a humidifier that calls for a more humidification process. HDH systems should consider the temperature constraint and fouling effects for membrane humidifiers.

A WH-HDH plant’s packed bed humidifier (0.5 m ID × 1.5 m, with a top brine temperature (TBT) of 46.07°C and feed water at 80°C) was briefly described for entropy minimization [88]. The number of packing blocks influences the performance of the humidifier. Entropy production was primarily affected by the humidifier’s efficiency, enthalpy, and temperature pinches. The heat capacity ratio (HCR) balancing was applied to the HDH system, with humid air extracted from the humidifier and injected into the tube plate dehumidifier (heat transfer area of 8 m2). The mass extraction balanced the humidifier and dehumidifier, enhancing freshwater production. Future studies could optimize the extraction-injection listed HDH system by minimizing entropy.

A Maisotsenko cycle-based air saturator was introduced as the humidifier [89]. The airflow in the wet channel was modified by an infiltration flow from the dry to the wet sections of the humidifier. An infiltration rate of 0.6 was found to achieve the maximum evaporation rate during blower and pump operations. The proposed system demonstrated a 30% increase in productivity and an 11% improvement in GOR compared to an HDH system using a direct contact humidifier. Additionally, it resulted in a 14% reduction in cost. A 7% decrease in carbon footprint demonstrated the proposed system’s cost-effective and ecologically sustainable technology relative to standard HDH. The maximum GOR of 0.57 necessitates alterations to the proposed unit.

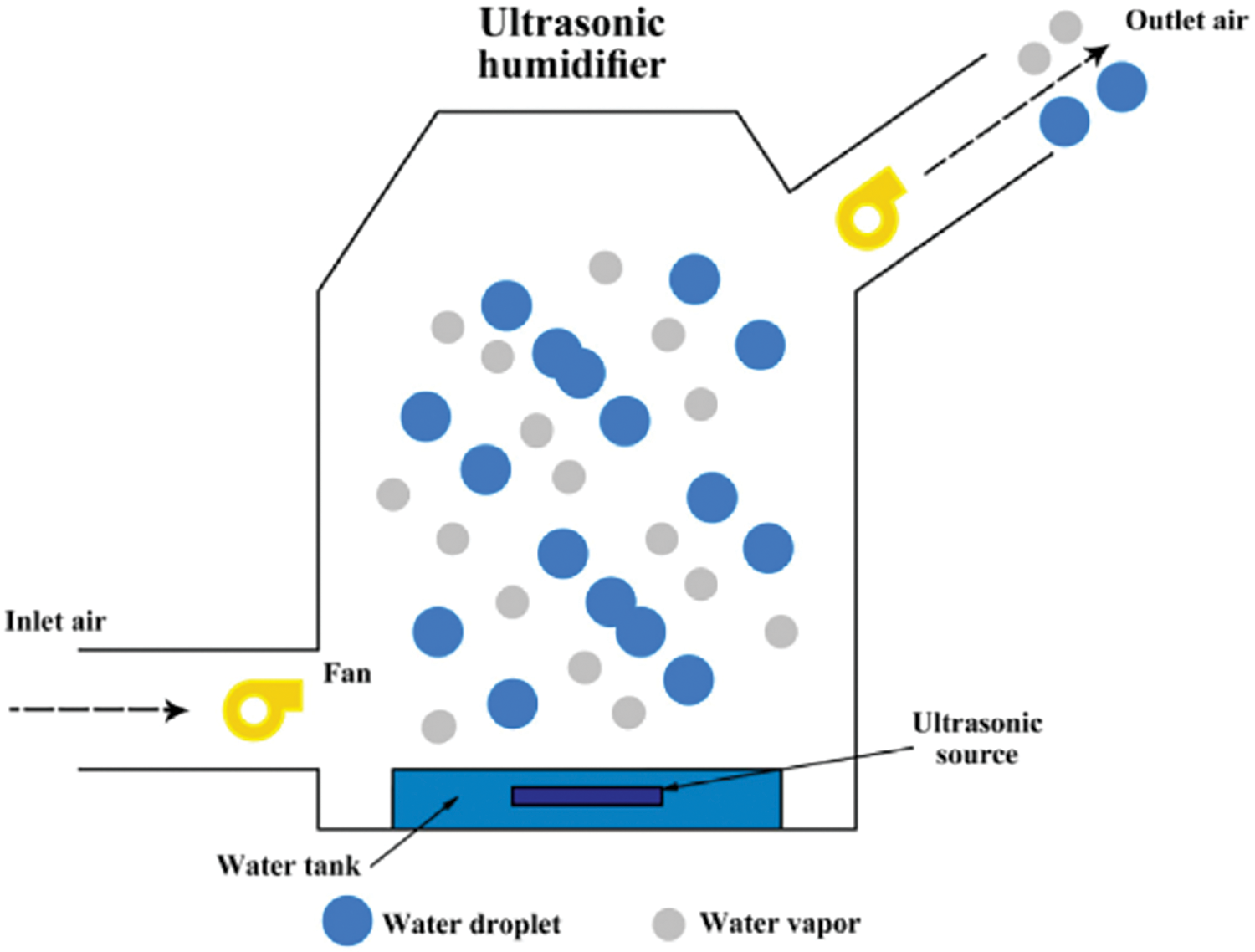

An affordable and widely available ultrasonic humidifier (1 m length, 0.6 m width, 0.02 m height) can be utilized in a WH-HDH system [90]. Ultrasonic vibrations atomize water droplets into the air [91]. A 30 W ultrasonic humidifier that released water vapor was studied [90]. After mixing the indoor air with the water droplets, humid air was pumped into the indoor environment (air exit), as shown in Fig. 8. Compared to steam humidification, the indoor ultrasonic humidifier saved 70% energy and 18% exergy. Exergy loss resulted from partial evaporation and the latent heat of vaporization. The humidifier improved thermal comfort and health by regulating indoor humidity. One significant factor is the energy generated by ultrasonic frequency fluctuations. However, the separation of salt from water vapor in ultrasonic humidifiers remains complex and requires further investigation.

Figure 8: Structure and operating process of the ultrasonic humidifier [90]

In summary, the hydrodynamics within the humidifier, shape, type, material, size, packing pad arrangement, and intake fluids parameters impact HDH performance. The key objectives are optimizing water-air contact duration, humidification process temperature, fluid mass flow rate, and humidifier pressure drop. These actions enhance the heat and mass transfer coefficients and exchange effectiveness, thereby increasing productivity and reducing entropy. Experimental, theoretical, and simulation studies support the industrialization of HDH. Moreover, multi-stage humidification and energy recovery through extraction-injection will further improve system performance. Controlling the use of introduced humidifiers can enhance the design.

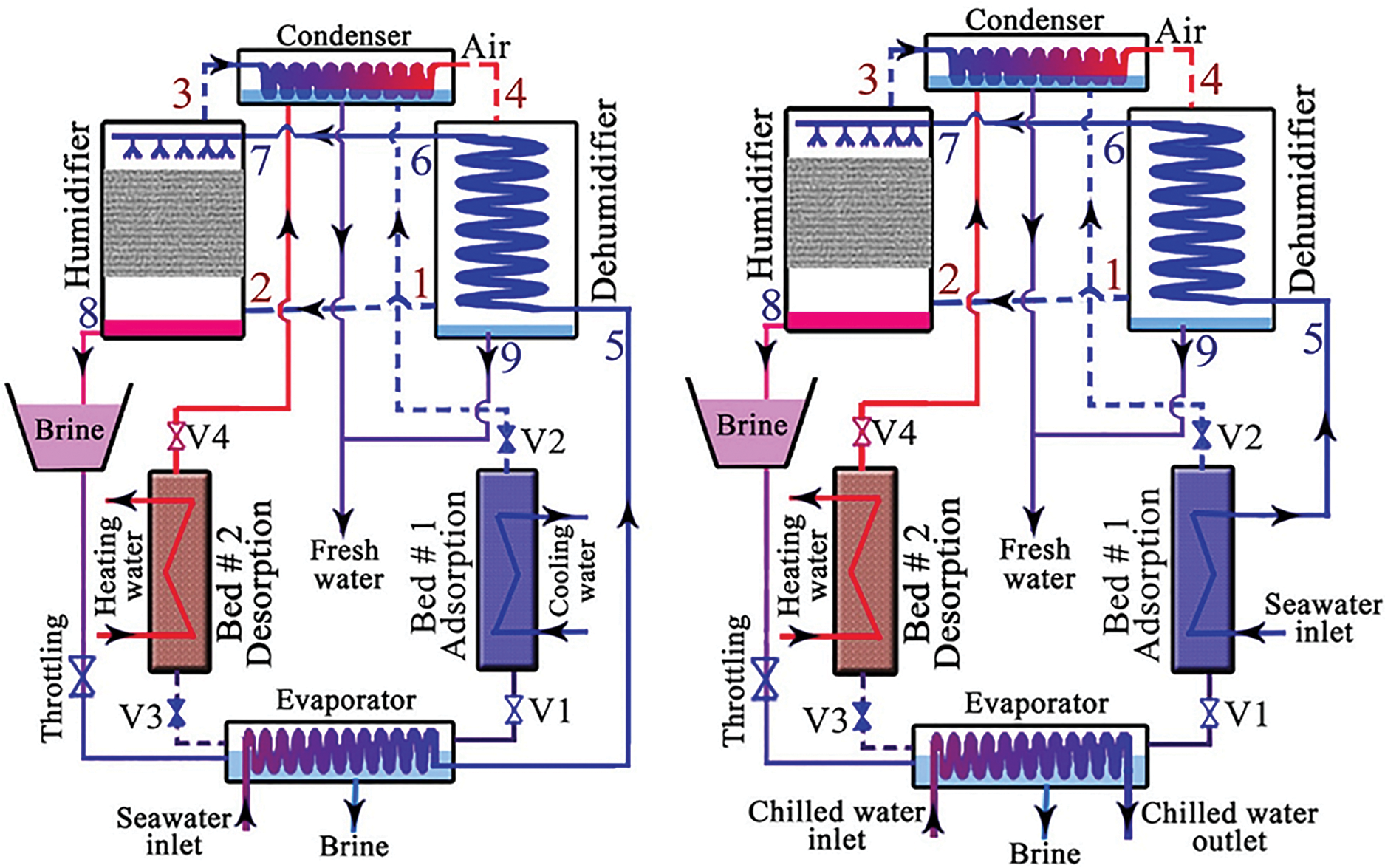

7.2 Thermal Analysis of the Dehumidifier

The energy balance equations for both the humid air and saline water sides in a dehumidifier are as follows:

An HDH system using air injection through a liquid desiccant solution (CaCI2) was investigated. With relatively low energy consumption, the liquid desiccant dehumidifier effectively removes moisture from humid air. Different air flow rates, desiccant solution levels, and regeneration temperatures are covered. At the optimal air flow rate and solution level, the efficiency values for the humidifier and dehumidifier were recorded at 0.92 and 0.87, respectively. The dimensionless groups (Nu Nusselt and Sh Sherwood numbers), related to thermal and mass transfer in the HDH system using a honeycomb desiccant dehumidifier (0.2 m × 0.2 m × 0.2 m), were also examined [92].

The addition or removal of heat and moisture depends on the properties of heat and mass. A higher desorption rate refers to an improved ability to remove moisture. To guarantee the continuous operation of the proposed system, the switching time, defined as the interval for the adsorption and desorption processes, was adjusted. The results showed that the adsorption temperature more significantly influenced the Nu and Sh numbers than the switching time. The lowest desorption temperature produced the highest Nu and Sh values. In OAOW cycles, the efficacy of the humidifier and dehumidifier will vary across locations with different humidity ratios, which must be accounted during the designing procedure. Evaluating system performance by (GOR metric) and cost can aid decision-making using desiccant-type dehumidifiers.

A two-dimensional finned-plate tube heat exchanger model in a WH-HDH system was developed [93]. An optimization of tube diameters, along with tube spacing (in longitudinal and diagonal directions), is performed as a design parameter to enhance heat transfer for the same fin material. Enlarging the tube spacing beyond a certain value reduced heat transfer. Larger tube diameters lowered the thermal conductive resistance between the fin and inner tube surfaces. Thicker fins were recommended due to their lower heat conductivity, which improved the dehumidifier’s effectiveness. It was also shown that reducing the transverse tube spacing led to a higher pressure drop. A comparative analysis of the performance of finned-plate tube dehumidifiers versus other direct or indirect dehumidifiers could help identify the optimal dehumidifier for HDH processes.

A multi-stage bubble-column dehumidifier equipped with two types of cooling helical coiled tubes was used in an experimental HDH system [94]. Experimental findings regarding heat flow and efficacy were delineated to elucidate the aspects affecting the performance of the bubble column dehumidifier. The analysis revealed that the heat flux significantly escalated with reduced coiled tube area and inlet air temperature, whilst the dehumidifier efficacy diminished. It is advised to reduce the liquid height to enhance the air-side pressure drop.

A bubble column dehumidifier was modeled for over-atmospheric pressure [95]. The influence of bubble-column efficacy on the dehumidifiers’ NTU and pressure drop regarding mass and heat transfer coefficients was acknowledged. The conclusion was that heat transmission enhanced while efficacy diminished with increased pressure. A huge dehumidifier at elevated atmospheric pressure offset the diminished efficacy. Huang [96] proposed using a multi-stage bubble-column dehumidifier to condense water vapor from the saturated air. The dehumidifier’s efficiency was improved by optimizing the available space through multi-stage dehumidification to preheat the feed saline water with a maximized recovery energy [97]. Due to the benefits of bubble column dehumidifiers over indirect dehumidifiers’ based on film condensation mechanism, the former may be a more viable substitute for HDH systems. The inlet temperature and air flow rate were the critical parameters influencing the dehumidifier’s efficacy and dimensions.

In summary, several direct and indirect configurations of heat exchangers (such as a plate-finned tube, helical coiled, bubble-column, subsurface, and desiccant-kinds) have previously been examined to enhance the dehumidification operation, resulting in improved HDH thermos-hydrodynamic performance. A non-functional dehumidifier deteriorates the performance of the humidifier. Lowering water inlet temperature to the dehumidifier, augmenting its flow rate over a predetermined threshold, expanding the heat exchange surface by a compact and efficient dehumidifier, employing an appropriate liquid desiccant solution at an optimal concentration, and operating the dehumidifier under elevated atmospheric pressure could enhance its efficacy. The optimal selection of a dehumidifier may be made after the performance metrics (e.g., GOR, PR, SEEC, and manufacturing cost) are disclosed in publications.

8 Technologies for Solar Desalination

Three groups might be used to classify solar desalination depending on the kind of solar system used: CSP facilities power the third; PV power the second; solar thermal systems power the first. Apart from membrane distillation (MD) based on the solar thermal system, the second and third categories mostly rely on membrane technology.

8.1 Types of Solar Thermal Desalination System

Solar-powered thermal desalination has two main types: First, direct solar desalination uses solar distillers to absorb, convert, and desalinate solar energy. The second kind, indirect solar desalination, operates the desalination machine and solar collector concurrently. Solar collectors heat a desalination machine. Solar-powered MED, MSF, RO, HDH, and MD systems are indirect solar distillation systems.

The glass coverage’s lower side condenses evaporated water [98]. The quantity of condensed water is proportional to the temperature differential between saltwater and glass cover. Authors reviewed solar still innovations such as finned and corrugated basin absorbers [99]. They found that fins or corrugated surfaces improve basin surface area and distiller water production. The stepped basin type solar still significantly enhances production by allowing a thin layer of saline water to pass over the stepped absorber. Summarised all approaches employed to improve the performance of stepped distillers, including double slope glass covers, nanofluids, nanocoatings, and reflective mirrors [100]. Other special solar stills, such as double slope-dual basin [101], tubular [102], tray-type [103], vertical [104], and pyramid-shaped [105] have also been reviewed, showing the best techniques and modifications.

The solar distiller tested several sensible heat storage materials, including rock-layered [106], marble pieces [107], concrete layer [108], porous materials [109], iron trays, black matt rubber, black gravel, aluminum waste, and uncoated materials. This sensible thermal storage method is rarely utilized in the solar system due to its lower storage density than latent heat [110]. The high storage density and consistent temperature thermal energy recovery make latent heat storage systems favored in solar stills and all solar thermal applications [111].

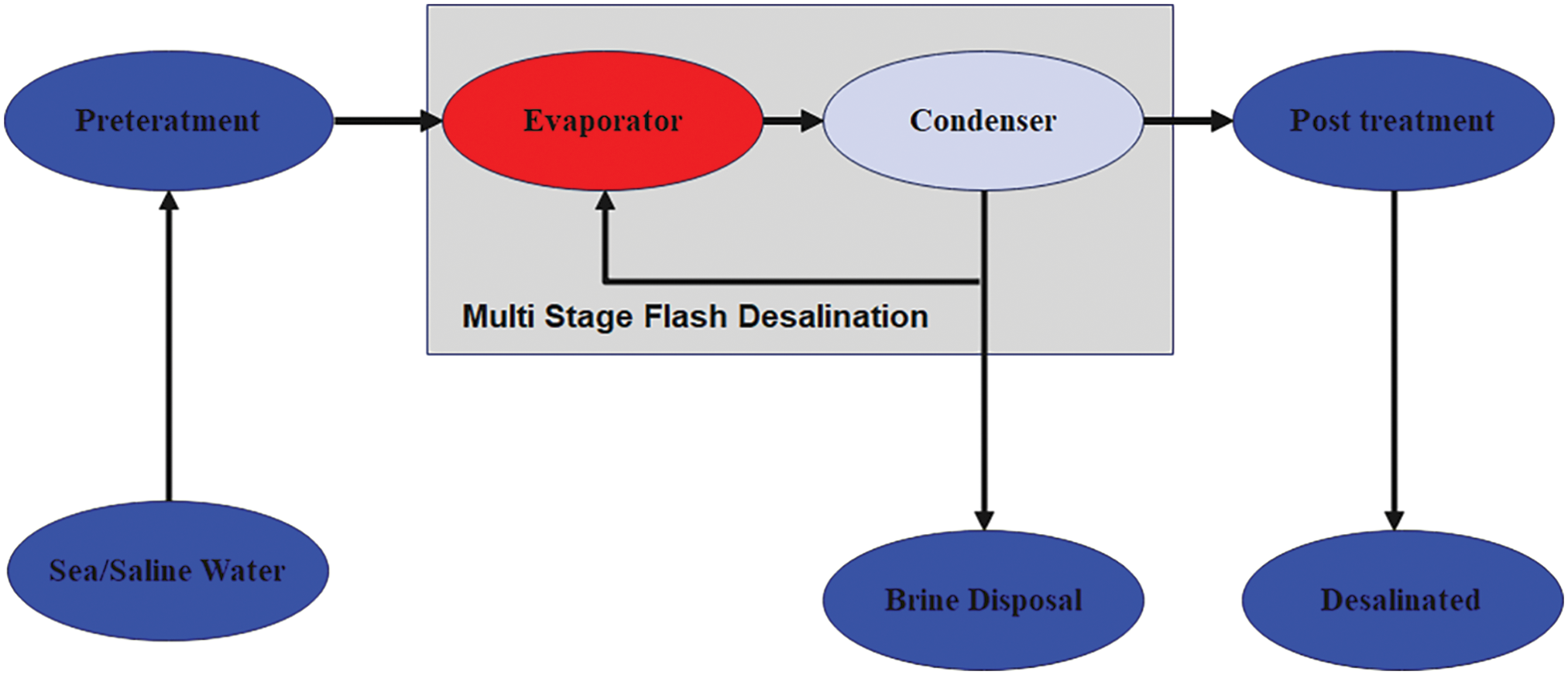

MSF ranks second in global desalinated water output after reverse osmosis (RO), as shown in Fig. 9 [111,113]. In technology MSF, seawater is heated in low-pressure vacuum reactors through which it flows. Subsequently, it is heated above its saturation temperature [114]. Subsequently, it transitions from one stage to the next, whereby a little volume of water swiftly transforms into vapor, while the residual amount advances to the subsequent stage for more vaporization, as seen in Fig. 10. The condensed vapor is then collected as distilled water. The latent heat of condensation is utilized to warm the supply of water. The MSF systems are employed in extensive power station cogeneration due to their compatible heat and temperature requirements with those expelled from power cycles [115].

Figure 9: Ratio of desalination methods to global output of desalinated water [112]

Figure 10: Block schematic of the Multi-Stage Flash distillation process

Integrating MSF with solar thermal heating collectors is one of the latest advancements. Reference [116] employed a dynamic simulator using TRNSYS to evaluate the life-cycle cost of a multi-stage flash (MSF) desalination unit equipped with a solar collector and an auxiliary heater across seven geographical areas. The efficacy of the solar MSF unit was evaluated with and without auxiliary heaters to verify that the hot water temperature satisfied the minimal standards for the MSF unit.

Reference [117] simulated a 20-stage MSF-OT solar desalination plant with twin storage tanks. Their model included all desalination and control system features and reproduced plant behaviour hourly for a year, including day and night operations. According to the study, the solar reflector might be 54% smaller. The average daily performance index was 15.2%, and the recovery ratio was 13.8%.

8.1.3 Multi-Effect Distillation

The competition between MED and MSF distillation remains unresolved, as previously mentioned. Nonetheless, MED ranks third in worldwide desalinated water contribution, behind RO and MSF, as seen in Fig. 10. The MED requires mechanical energy and heat.

Seawater flows via tiny, low-pressure vessels in the MED system. In this system, the initial effect receives heat, and each succeeding effect delivers fusion heat from its vapor. Unlike this processing, MSF sensibly heats seawater to recover latent heat from vapor. MED uses latent heat to vaporize saltwater. Previous research has developed partly solar-powered MED systems. Reference [118] tested a solar-powered hybrid MED-HR system. With a 45% higher performance ratio, the hybrid MED designs beat the standalone MED system. The hybrid system produces 159.84 m3/year of freshwater at $5.37/m3. The hybrid system reduces CO2 emissions by 189 tons/year, making it an eco-friendly and cost-effective way to provide fresh water. The viability of merging an ORC with a parabolic trough solar field and natural gas heater-powered MED-ACS was examined [119]. The energetic, exergetic, and economic performance of MED-ACS was evaluated. The examined system had a lower water cost per unit and higher energy efficiency than single-and double-purpose MED and ACS systems.

Numerous research studies have examined and improved multi-effect desalination (MED) systems. Reference [120] modeled a porous wood solar collector-based MED system to assess its performance. They evaluated how the number of impacts, input seawater flow rate, solar energy, and motive steam temperature affected MED system energy consumption. Researchers found a minimal power consumption of 24.88 kWh/t in the MED unit achieved with an ideal steam production temperature of 145°C in the solar wood collector under specified operating conditions. Reference [121] introduced an innovative approach termed Flash ME, which integrates the MSF and MED designs in a distinctive and compact configuration to generate desalinated water from unusual sources with maximal exergy and energy efficiency. The research delineates the Flash ME system’s process flow diagram and the Aspen Plus simulation software.

According to the above-mentioned survey, the MED design is a suitable technological and efficient choice for combining solar thermal heating collectors in the large-scale industry. However, the examined research on solar-powered MED systems showed a notable improvement in the thermal and financial performances of the stand-alone solar MED systems. Still, combining MED with membrane distillation (MD) systems driven by solar thermal collectors remains limited; more theoretical and experimental research is necessary to determine these hybrid solar distillation systems’ technical viability and financial advantages. Furthermore, the investigation shows that the broad use of economical and thermodynamical evaluations of solar MED systems is infrequently addressed. Although the exergoeconomic optimization studies on these systems. Although the cost of freshwater generated in solar energy-powered desalination facilities already surpasses traditional desalination plants, the environmental benefits might provide a possible balance. Using solar thermal systems to run desalination operations helps to reduce several ecological effects, including energy consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and concentrated brine disposal. Because water vaporizing in thermal desalination systems generates significant energy demand, MSF and MED show greater energy consumption among the desalination techniques than RO. Thus, various research developments help to increase the thermo-economic advantages of CSP-powered MSF and MED designs: A newly stem generation of advanced-scale control additives could be environmentally biodegradable; enhanced MSF brine-recirculation designs to increase total desalination plant recovery; and improved energetic efficiency in solar MED systems by absorption heat pumps.

8.1.4 Humidification/Dehumidification HDH

Fundamentally, based on the direct interaction between air and hot saline water generated in the humidifier where mass and heat transfer from water to air, the HDH desalination systems. The condensation that occurs in the humidifier where the humid air cools follows this step. The salty water is heated constantly via solar water collectors. Although solar air heaters were utilized for air heating, References [122,123] presented a technical direction for a solar-based HDH system. It was decided to heat the saline water pre-humidifier entry using the high-temperature solar heaters. Many setups of HDH were investigated in which a solar collector always heated the salt water. On the other hand, the solar air heater is hardly included to heat the passing air using solar collectors of different types such as parabolic trough [124], vacuum tube [32,125–127], and flat plate [128,129], the saline water cycle may be open or closed. Considered as the closed and open loop of air circulation with a solar HDH system. Among the studied HDH setups, the closed cycle of heated water and air exceeded the very efficient system.

The choice of filling material for the humidifier, also known as packing material PM, is the determinant in enhancing this system. Many research lines were carried out to evaluate the many materials as PM, like cellulose paper [126,127], woody material, and wick [125]. Among the several operational parameters under investigation in literature studies, raising the temperature of saline water is regarded as the most important in increasing the system’s productivity [125,129]. Experimentally, reference [130] investigated a solar-based HDH unit driven by a PTC field and thermal storage unit, employing very salty water sources such as RO brine waste and contaminated unclean water from the oil shale. The HDH-PTC system was claimed to use RO brine waste to gather a daily freshwater yield of 72 kg/d at an input saline water temperature of 85°C.

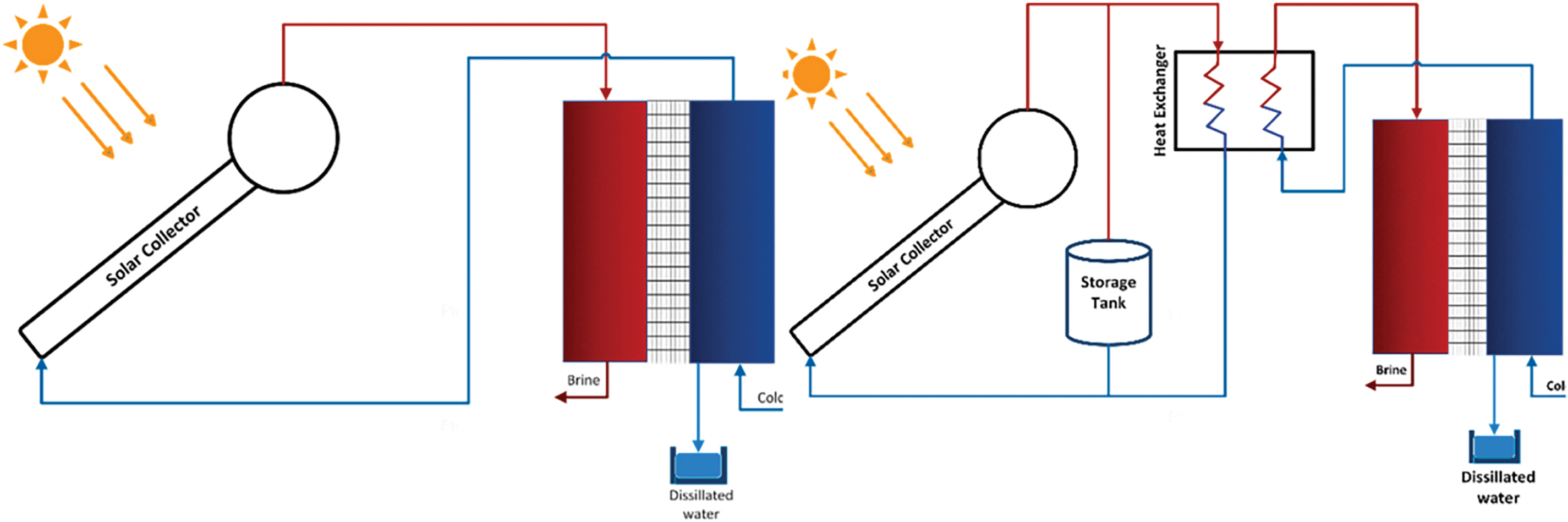

Integrating solar still desalination unit complementary elements increases its capability, as one of these combinations is inserting solar heat pipe into the still, which enhances the water treatment production due to the impact of a thermal augmentation on water evaporation [131]. Membrane distillation (MD), which combines the advantages of membrane and thermal distillation, presents a viable method for desalinating seawater. Four membrane distillation topologies are often employed: DCMD, VMD, AGMD, and SGMD [132,133]. MD differentiates itself from thermal desalination methods by a range of advantages. Initially, MD can operate at lower feed water temperatures by this constrained excess heat. Secondly, compared to thermal conventional desalination systems, it can be designed more compactly and be suitable for smaller systems [134]. Different conceptually designed solar collectors have been used to heat the feed water for MD. Additionally, it is important to consider if the salty water flows directly in the solar collector or is heated via a heat exchanger, i.e., using direct or indirect solar water heaters (direct or indirect fluid loop), as shown in Fig. 11 [135].

Figure 11: Variations in solar-based MD system configurations Direct loop layouts; indirect loop layouts

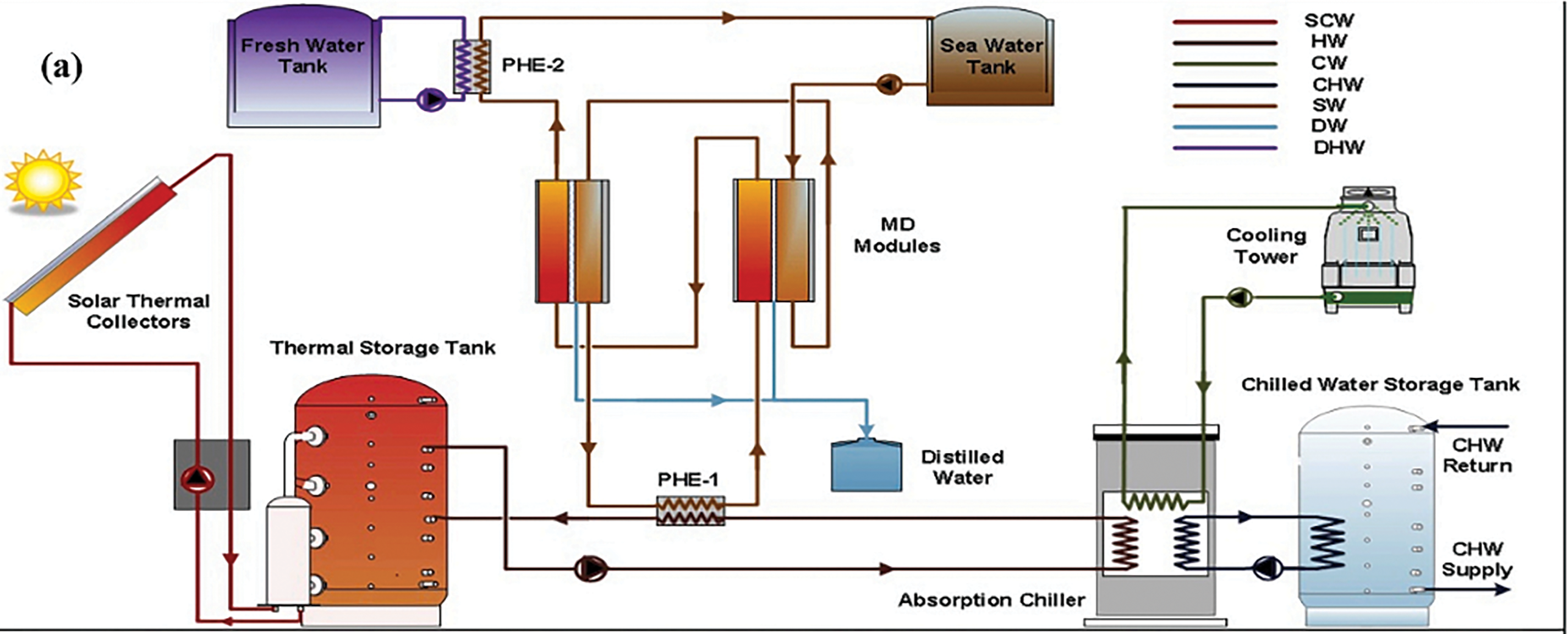

Among various solar collectors, the flat plate solar collector is the most commonly used preheating in conjunction with MD [136–141]. The solar vacuum tube collector is also prevalent in this domain [142–144]. In UAE, Ras Al Khaimah, experimental tests of a unique solar thermal membrane distillation unit are performed [145], comprising an air gap membrane distillation unit, a solar collector, an absorption chiller, and a heat exchanger (refer to Fig. 12). Water is heated in the solar collectors and stored in a thermal energy storage reservoir to be subsequently employed to run the membrane distillation module and the absorption chiller. On the other side, the absorption chiller produces a chilled-water employed for space cooling via the fan-coil system, while hot household water is produced using hot brine water released from the MD unit. The solar-integrated MD plant generated (4.1) lph, reflecting a 23% rise in thermal efficiency. Analysis of the technical-economical sides indicated that land charge significantly influences the payback time, potentially reducing it by around 18% and enhancing cumulative net investments by almost 10%.

Figure 12: Schematic representation of a solar thermal membrane distillation system [146]

Usually, a PV module is used to provide power, and batteries store the electricity for the unpredictable operation of the hybrid system. A desalination system consisting of SFPC (6 m2) and DCMD modular powered by (1.63 m2) PV panel with a total membrane size of ten square meters is developed [146]. The feed salt water is heated by the recovery of condensation latent heat that provides an overall freshwater production of 86 L on a hot summer day in Kairouan, Tunisia.

The analyzed results demonstrate that membrane porosity, solar preheating unit, and saline water inlet temperature are the most important design considerations and operational characteristics influencing the water yield production of hybrid solar-membrane distillation systems. The system’s long-term performance indicates that the daily output of distilled water from the solar-MD systems is excellent, even under optimum climatic circumstances.

8.2 Thermal and Hybrid Solar Desalination System

As previously stated, most desalination processes make extensive use of energy. Nowadays, fossil fuels run most of the desalination plants worldwide. Still, most regions experiencing higher freshwater demand also get significant solar energy. Given its abundance and little pollution, solar energy might thus be an excellent source for this aim. Direct (thermal as a single slope basin or electrical as a powering RO unit by PV panels) and indirect (hybrid thermal/electrical) categories separate the several solar desalination techniques in the literature. In this context, the desalination plant is considered a direct type if its feedwater directly absorbs solar energy. For an indirect desalination plant, the solar energy is converted to electricity, used or gathered by solar thermal collectors, and then transferred to the saline feedwater. A heat engine might run the facility on solar energy in both cases. Adapted from [147], Fig. 13 shows solar-desalination systems’ classification. The HDH desalination system is designated as an effective technique used for small-scale (produced up to ten m3/day) to medium-scale (up to 10,000 m3/day) direct drive. Saline water absorbs energy from solar (thermal or hybrid PV/T) collectors or directly from sunlight in solar integrated HDH system. In this regard, it may be either direct or indirect.

Figure 13: Classify desalination processes based on solar energy

Several factors must be considered when selecting a technique for a desalination project. The project’s outcome is heavily influenced by demand, resources, economics, maintenance, and estimated longevity. For instance, the concurrent need for electricity and freshwater can call for poly-generation plant technology. Furthermore, the desalination plant might employ extra heat solar thermal collectors to satisfy heating requirements. The extent of the request sector might have a major influence on the design process, as some technologies cannot meet high request levels. Examining the operations and maintenance sectors is crucial as certain technologies may run long without demanding major maintenance. One should also consider the possible market and the current availability of land.

Furthermore, environmental issues should not be disregarded as they may be resolved in financial computations. The most efficient form of sustainable renewable energy is thought to be solar energy [148]. Solar-powered HDH desalination systems are categorized primarily by the heated fluid. The features of the humidifier and dehumidifier material and design parts, as well as important performance indicators such as freshwater yield, GOR, FWP, and the cost of freshwater production, are the main focus of additional classification. The thermal performance of a tracked concentrated trough parabolic tubular solar still (TSS) was experimentally studied [149]. A hexagonal glass cover is the feature of this tubular still. The still is tested with and without the insertion of a heat pipe for different tilt angles and depths of saline water to highlight their impact on freshwater productivity. The results showed that incorporating heat pipes increased freshwater yield by 25% to 40% and improved thermal efficiency by 25%.

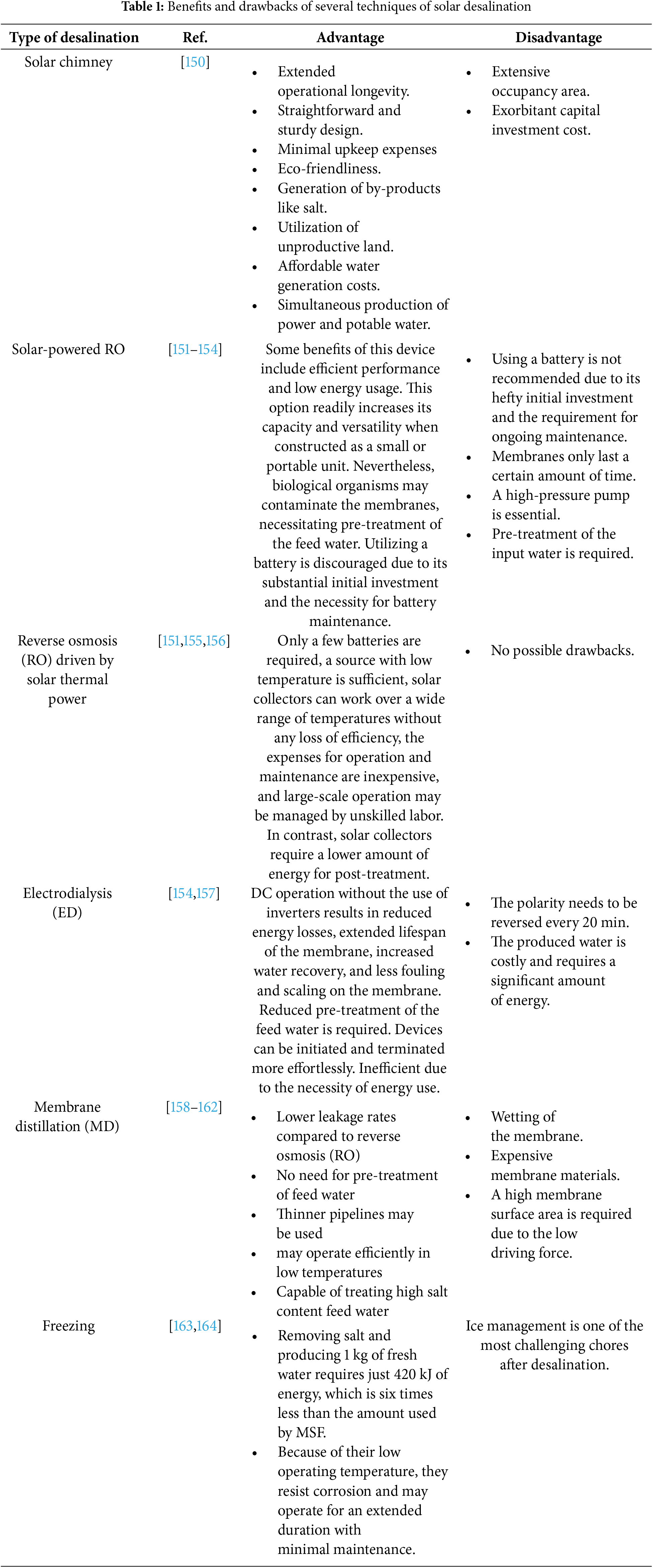

Table 1 provides a comprehensive assessment of the advantages and drawbacks of several solar desalination technologies, including their impact on the environment, economic feasibility, energy usage, building requirements, availability of materials, efficiency, and the quality of the distilled water produced. This table offers pertinent data on the comparison of various desalination technologies.

9 Humidifiers and Dehumidifiers Driven by Waste Heat

The rising need for electrical energy accompanies the increasing demand for water. So, innovative and alternative approaches to powering desalination systems [165] are studied. Additionally, the focus on developing sustainable methods to effectively utilize waste heat forced researchers to explore using HDH desalination systems powered by low-grade waste heat. This waste heat could be recovered from ventilation, heating, air conditioning, HVAC equipment, thermal power plants and can be combined with renewable energy systems to yield freshwater. HDH (humidification-dehumidification) systems fueled by the waste heat generated by HVAC air conditioning units coupled with solar PV panels are samples of this application. In addition, all studies conducted on integrating waste heat from power plants with HDH desalination systems are either theoretical, based on thermodynamic aspects [166,167], as in water power cogenerating system per energy utilization [168], hybrid generation systems [169–171], or involve mathematical investigations [172–174] or economic analysis [175,176]. The actual findings differ significantly due to the transient behavior of the systems and heat loss. Recently, there has been a surge in research on HDH systems driven by air conditioning, HVAC, and solar photovoltaic panel waste heat. There are concentrative theoretical and experimental investigations to understand better how HDH condenser units interact with the environment. A successfully employed waste heat from residential air conditioning units to indirectly or directly warm the air or water in the HDH systems is presented by Santosh et al. [38]. Furthermore, the extraction of waste heat has been recognized as a means to enhance the thermal efficiency of the air conditioning HVAC system while minimizing its environmental footprint [177]. The study focused on harvesting thermal energy from solar radiation for water evaporation involving hydrogel as a distinctive light-absorbing substance, enhancing photo-thermal solar efficiency conversions by minimizing heat loss [178].

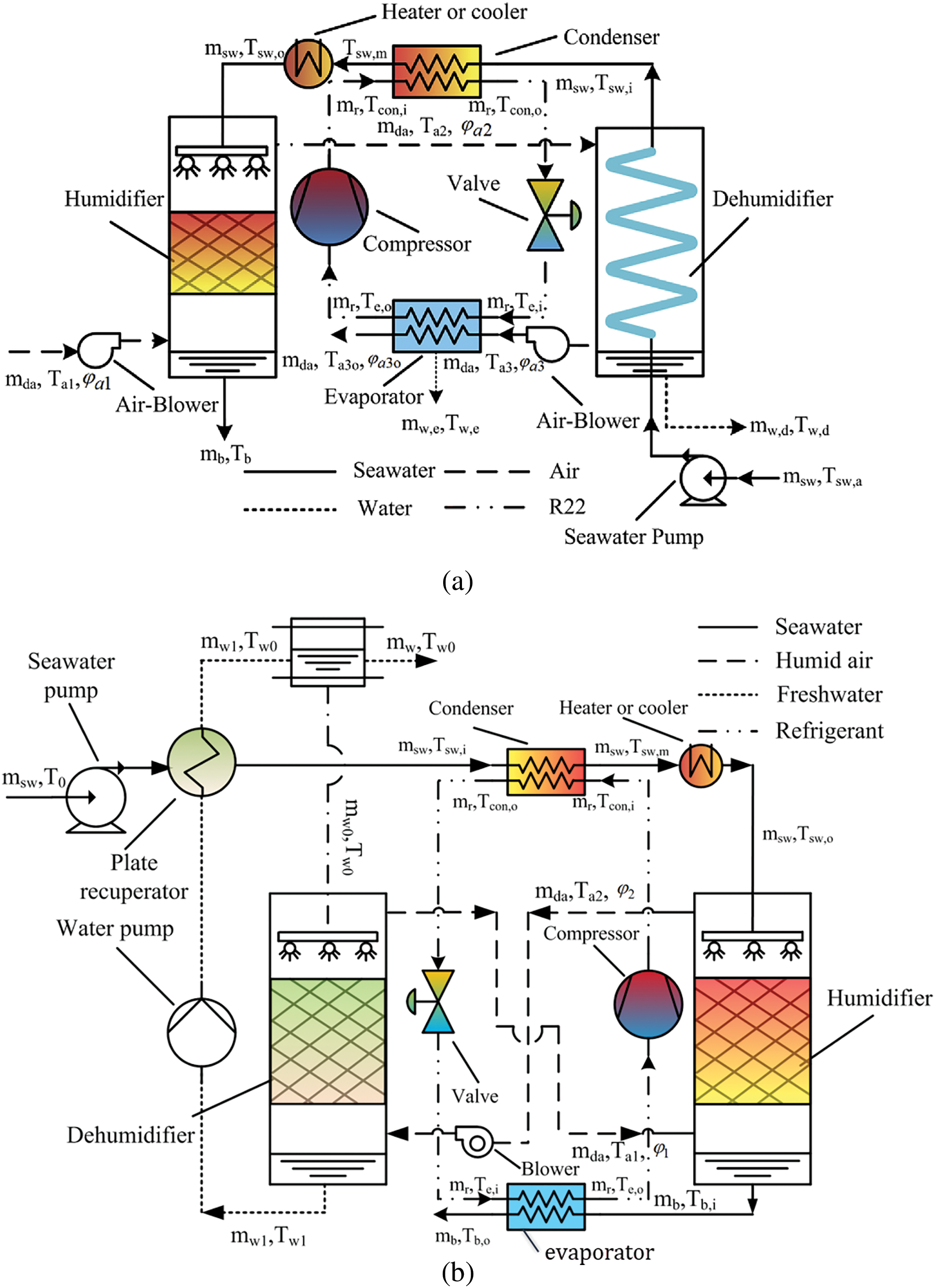

9.1 Saline Water Preheating Systems

A theoretical study investigated the performance of direct contact packed bed humidifiers in a desalination system integrated with a heat pump [179]. The saturated air that leaves the direct contact humidifier is cooled by sea water in the surface-type dehumidifier to yield freshwater, as shown in Fig. 14a. Extra heating is done to see water in the refrigerant condenser of the heat pump before it enters the humidifier. The performance metrics of the combined system demonstrated 82.1 lph of freshwater yield and a GOR index of 5.14. The unit freshwater yield increases with the increasing compression ratio for the heat pump and decreasing the pinch-temperature difference in its condenser. Optimizing this system through an open-air layout [180] improved production output of 88.34 kg/h. However, the gained output ratio (GOR) decreased to 3.72 due to the increased power consumed to attain the desired air temperature at the humidifier inlet. This study extracted that the close-air loop had superior thermal efficiency compared to the open-air cycle. The dehumidifier unit with a closed-air loop inserted with a directly contacted packing-bed is adopted instead of the surface-kind dehumidifier unit, as shown in Fig. 14b [181]. The humidifier’s intake water is preheated by a direct plate recuperator and heat pipe condenser. Freshwater yield and GOR of 71.6 lph and 5.28, respectively, were recorded, indicating that the remaining heat in packed bed dehumidifiers helped lower system energy consumption.

Figure 14: Recovery of waste heat from saline for heating the saltwater in the HDH/REF cycle using (a) traditional dehumidifier [180], (b) packed-bed dehumidifier part [181]

Furthermore, packed-bed material (type Sulzer Mallapak 250-Y) of 0.29 and 0.21 m2 wet surface areas is loaded throughout the humidifier and dehumidifier [182]. The thermodynamic study for the humidifier revealed that the straight contact enabled efficient humidification, even with surroundings of little humidity. Additionally, it was found that the straight contact in the dehumidifier performed similarly to traditional surface dehumidifiers when used in conjunction with the waste heat from the heat pump.

An experimental study examined HDH system powered by solar energy and waste heat, utilizing a honeycomb paper packing in the humidifier and a flat tube heat exchanger (FTHE). The system achieved its maximum output of 12.75 kg/h when air and water mass flow rates were 450 and 0.3 m/h, respectively [49], as an ideal mass flow ratio throughout humidifier and dehumidifier items.

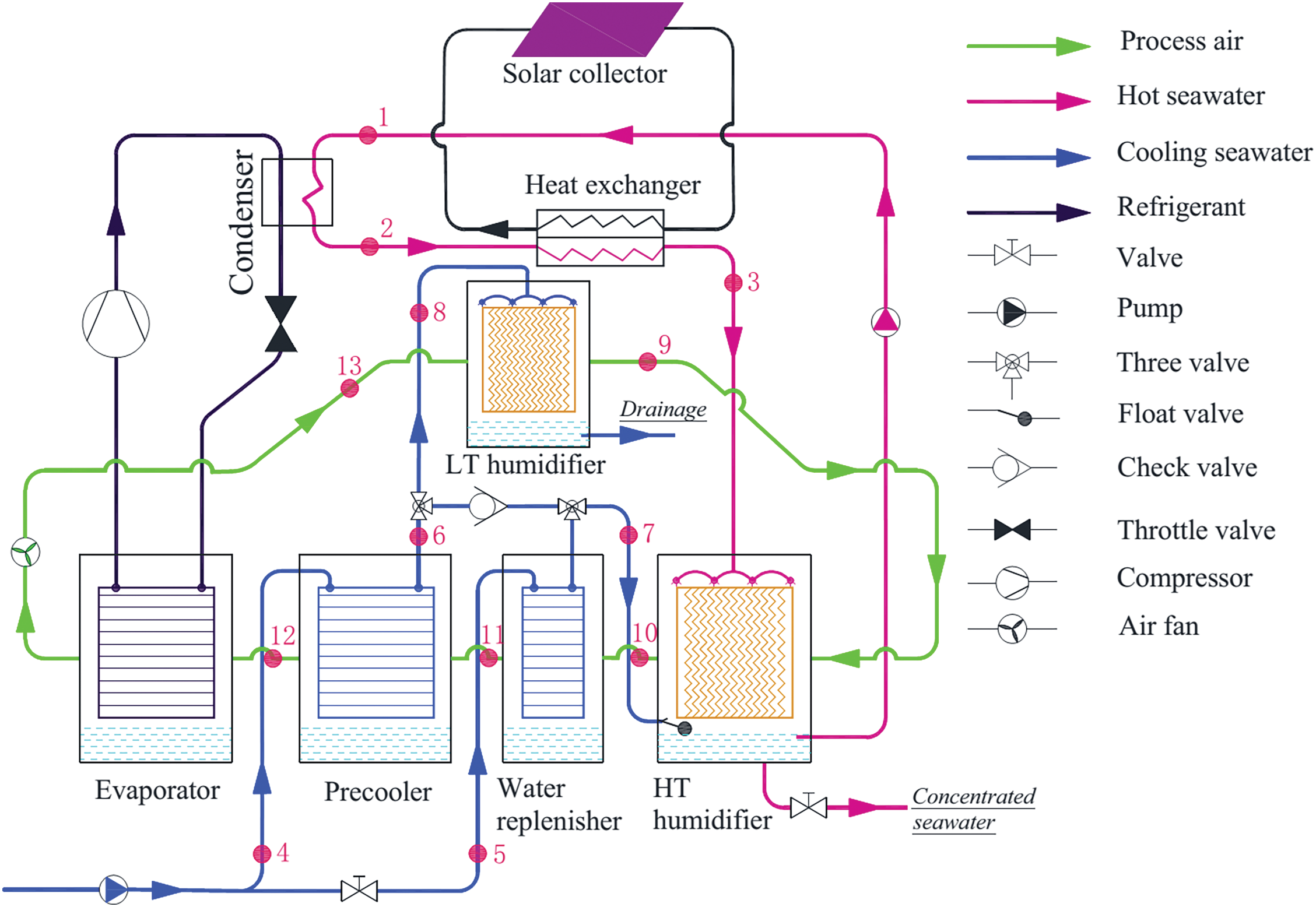

Better yield came from using the leftover heat from the dehumidifier [183]. Both high and low-temperature humidifier units were employed to enhance the performance, coupled with a water-replenishing device known as a dehumidifier, as seen in Fig. 15. Adding a heat recovery system to the humidifier and dehumidifier unit resulted in a 15.15% increase in yield and a 55.64% increase in GOR compared to the prior partial heat recovery system. This improvement was observed when comparing the system to paper and plastic polyhedron ball humidifiers. Paper packing increased the humidification efficiency by 27.76% under identical working conditions. The impact of incorporating various accessible materials into passive Single Slope Solar (SSS) stills on their output is examined [184]. Testing is conducted on a traditional still and three SSS stills equipped with carbon filter media, copper wire mesh, and cellulose sheets. All these stills exhibit symmetrical proportions with a base area of 0.5 m2, tested using Iraqi marsh water of 20 mm head. The results indicated that these materials accumulated energy from solar radiation, prolonging their yield into the early night hours and enhancing the daily distillate output. The freshwater yield was 9506, 4930, and 4160 l/m2.day for stills equipped with copper wire mesh, carbon fiber, and cellulose sheets, respectively, compared to 2000 l/m2.day for the traditional still [184].

Figure 15: A solar collector assists the HDH-REF system with internal heat recovery [183]