Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Thermal Performance and Application of a Self-Powered Coal Monitoring System with Heat Pipe and Thermoelectric Integration for Spontaneous Combustion Prevention

1 School of Electrical Engineering, Guangzhou City University of Technology, Guangzhou, 510800, China

2 Guangzhou Pukai Thermovoltaic Micro Energy Technology Ltd., Guangzhou, 510800, China

* Corresponding Author: Tao Lin. Email:

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(5), 1661-1680. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.070787

Received 23 July 2025; Accepted 23 September 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

Targeting spontaneous coal combustion during stacking, we developed an efficient heat dissipation & self-supplied wireless temperature measurement system (SPWTM) with gravity heat pipe-thermoelectric integration for dual safety. The heat transfer characteristics and temperature measurement optimization of the system are experimentally investigated and verified in practical applications. The results show that, firstly, the effects of coal pile heat production power and burial depth, along with heat pipe startup and heat transfer characteristics. At 60 cm burial depth, the condensation section dissipates 98% coal pile heat via natural convection. Secondly, for the temperature measurement error caused by the heat pipe heat transfer temperature difference, the correction method of “superimposing the measured value with the heat transfer temperature difference” is proposed, and the higher the coal temperature, the better the temperature measurement accuracy. Finally, the system can quickly (≤1 h) reduce the temperature of the coal pile to the spontaneous combustion point, significantly inhibiting the spontaneous combustion phenomenon, the maximum temperature does not exceed 49.2°C. Meanwhile, it utilizes waste heat to drive thermoelectric power generation, realizing self-supplied, unattended, and long-term accurate temperature measurement and warning. In a word, synergistic active heat dissipation and self-powered temperature monitoring-warning ensure dual coal pile thermal safety.Keywords

Coal, one of the most abundant fossil fuels, has been extensively utilized in thermal power generation and industrial production. Notably, thermal power contributes over 40% of the global electricity supply [1], making the secure and stable provision of this energy material crucial for power infrastructure development. However, constituents including sulfur, nitrogen, and microorganisms [2,3] within coal render it highly susceptible to oxidation reactions during storage. This process triggers internal heat accumulation that, without timely temperature monitoring and heat dissipation, escalates progressively until spontaneous combustion occurs [4,5]. Consequently, developing an internal temperature monitoring and early-warning system coupled with effective cooling strategies is imperative for enhancing coal storage safety.

Coal pile spontaneous combustion has garnered significant scholarly attention. Conventional monitoring approaches include calorimetry, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and related techniques [6–8]. Zhang et al. [9] proposed a differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) exothermic onset method to determine coal self-ignition temperatures, demonstrating enhanced spontaneous combustion propensity with increasing heating rates or decreasing oxygen concentrations. Numerical modeling to reveal both the critical self-ignition temperatures and minimum time-to-ignition is now widely employed [10]. Zhang et al. [11] employed machine learning methodologies to represent complex physicochemical processes and external influencing factors, establishing a regression prediction model correlating the crossover point temperature with 13 input features. Results demonstrated that the machine learning-predicted crossover point temperature achieved ≥90% accuracy across test datasets. Zhao et al. [12] constructed a rectangular coal pile spontaneous combustion experimental platform, revealing intrinsic combustion characteristics and high-temperature zone migration patterns. Through correlation analysis, they successfully predicted internal hotspot distributions. Deng et al. [13] emphasized that accurate CO detection is critical for preventing coal ignition. They proposed a compensation model based on the Grey Wolf Optimizer-Support Vector Machine (GWO-SVM), effectively suppressing temperature and pressure interference on measured concentrations and enhancing CO measurement precision. Additionally, experimental monitoring techniques—including temperature sensors [14], wireless temperature monitoring systems [15], and infrared thermal imagers [16] enable timely detection of temperature anomalies in coal stockpiles, thereby preventing spontaneous ignition and fire incidents. Miranda et al. [17] validated infrared thermography as a highly effective method for coal pile temperature mapping. Qiu et al. [18] developed a portable detection system leveraging laser spectroscopy technology to precisely quantify gaseous inhibitors. By utilizing lasers as sensing light sources, they monitored the real-time concentration dynamics of carbon monoxide (CO) and methane (CH4) in coal yards, accurately identifying two critical temperature thresholds. Li et al. [19] designed a high-sensitivity fiber-optic photoacoustic (PA) gas sensor for coal spontaneous combustion monitoring. This system integrates gas-sensitive heads, optical fibers, and demodulators to transmit laser-generated PA signals and detect PA pressure via white light interferometry.

Temperature monitoring is critical for coal pile safety, yet timely and effective heat dissipation methods constitute another vital aspect of enhancing storage security. Conventional heat dissipation approaches include manual water spraying, forced-air cooling, evaporative cooling, and advanced phase-change materials (PCMs) [20,21]. Sun et al. [22] identified coal oxidation propensity as the decisive factor in spontaneous combustion. They constructed molecular models based on experimental analyses and performed quantum chemical simulations to reveal the mechanism of coal oxidative capacity. Consequently, suppressing oxidation reactivity emerges as an effective prevention strategy. Ma et al. [23] developed an antioxidant gel-foam using foam, gel, and chemical inhibitor OPC. This material isolates coal from oxygen, reduces oxidation rates, and prevents spontaneous ignition. Yin et al. [24] engineered encapsulated PCMs, where shell rupture at phase-transition temperatures, releases inhibitory liquids that permeate coal seams, creating oxygen barriers to effectively suppress combustion. Zhang et al. [25] synthesized microencapsulated PCMs with polyethylene glycol 6000, analyzing inhibition mechanisms for different core-wall ratios on spontaneous combustion of coal in combination with thermodynamic parameters. However, these methods face limitations in large-scale applications, such as incomplete oxygen isolation, high material synthesis costs, and implementation constraints. Thus, low-cost, high-efficiency thermal regulation technologies represent the optimal solution for heat dissipation and spontaneous combustion prevention in bulk coal stockpiles.

Gravity heat pipes (GHPs) are widely deployed in industrial and electronic applications due to their high thermal efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and operational safety [26–28]. Zhang et al. [29] developed non-uniform diameter GHPs, investigating how condenser inner diameter, evaporator/condenser lengths, condenser wall temperature, and working fluids affect filling envelopes, operational envelopes, and thermal resistance under vertical orientation.

Dai et al. [30] systematically analyzed the impacts of working media, structural configurations, and installation layouts on GHP thermal efficiency. Jin et al. [31] established a GHP boiling characteristic test platform to resolve heat dissipation challenges in fuel cell operations. GHPs have been implemented in mine exhaust heat recovery (Zhai et al. [32]) and geothermal energy extraction (Ma et al. [33]).

Zhang et al. [34] pioneered GHP deployment for coal gangue temperature regulation while enhancing waste heat recovery efficiency. Zhang et al. [35] experimentally analyzed GHP-mediated heat dissipation in coal piles by simulating central heat sources with bottom-up heating, creating vertically decreasing thermal gradients by increasing the point of high temperature heat sources. Their findings revealed that gravity heat pipes (GHPs) inserted into the coal pile had different cooling effects on the coal at different horizontal positions, and the effect of GHPs on the coal at lower horizontal positions was the most obvious. The heat pipe can effectively prevent and control the spontaneous combustion of coal and effectively disperse the heat accumulation inside the coal pile that causes temperature rise, which provides a new idea for suppressing the spontaneous combustion of coal and centralised extraction of heat energy from the coal pile [36].

From the perspective of heat transfer medium, Zhang et al. [37] investigated the regulation of the influence on the heat dissipation effect of the heat pipe under different heat source input power conditions by comparing the methanol working material with no working material, and the results showed that the copper-methanol gravity heat pipe can best control the continuous temperature increase at the heat source location, destroy its heat storage environment, and inhibit the self-heating of the coal pile. Ren et al. [38] used a methanol matrix with a 23% higher heat dissipation efficiency than the ethanol/hexane variant of a gravity heat pipe. Wang et al. [39] used a hybrid nanofluid matrix in a gravity heat pipe inclined at 60°. The results showed a 15.2% reduction in thermal resistance and a 6.83% increase in heat transfer efficiency with reduced nanoparticle agglomeration. In summary, these findings demonstrate GHPs’ efficacy in dissipating internal heat accumulation from coal stockpiles, thereby preventing spontaneous combustion.

In summary, the problem of preventing the spontaneous combustion of coal during storage and stacking needs to be solved urgently. Academics have tried to use active temperature sensors combined with wireless temperature measurement and monitoring systems, infrared thermal imagers, and laser spectroscopy to monitor the temperature of coal piles, and the effect is remarkable. However, these traditional temperature monitoring methods face significant limitations. They rely on external data sources, require grid power or other external electricity supplies, and cannot measure internal temperatures within coal piles. The thermal safety of coal piles not only relies on the safe monitoring of coal pile temperature but also relies on efficient heat dissipation systems, including water spray cooling and gravity heat pipe cooling. Gravity heat pipes, as efficient heat sink devices, are mostly used for waste heat recovery from coal piles. Comprehensive analysis reveals that existing technical solutions feature relatively independent temperature monitoring and cooling systems for coal piles, lacking efficient synergistic operation. In coal yards, innovative integration of gravity heat pipes—used for heat dissipation and waste heat power generation—with temperature monitoring systems remains scarcely explored. A critical research gap lies in quantifying and reducing the temperature measurement error caused by the inherent heat transfer temperature difference of heat pipes in coal pile applications. This constitutes the core research objective of the present technical solution.

Therefore, it is necessary to develop a coal internal heat dissipation with efficient temperature measurement and early warning technology, which is of great significance to improve the safety of coal storage and stacking. In order to curb the spontaneous combustion of coal during stockpiling, this study develops an efficient heat dissipation & self-supplied wireless temperature measurement system (SPWTM) integrating gravity heat pipe and thermoelectric power generation, which can provide double coal stockpile safety. The heat dissipation of the coal pile is realized by the phase change heat transfer of the gravity heat pipe. The SPWTM is self-powered by waste heat-driven thermoelectric power generation in the condensing section of the heat pipe, and the SPWTM transmits the temperature measurement results to the temperature monitoring and warning platform in real-time. To this end, the startup characteristics, heat transfer, and heat dissipation characteristics of the gravity heat pipe are investigated for different coal pile heat production powers and burial depths. Based on the natural convection heat transfer analysis, the heat dissipation performance of heat pipe heat dissipation is deeply investigated. Considering the temperature difference of heat pipe heat transfer, the optimization method of SPWTM accurate temperature measurement is deeply explored. Then, it is applied in a real coal pile to verify the feasibility of maintaining the thermal safety of the coal pile based on the synergistic effect of heat pipe active heat dissipation and thermoelectric power generation self-supplied energy temperature measurement.

2 Efficient Heat Dissipation and Self-Powered Wireless Temperature Measurement System

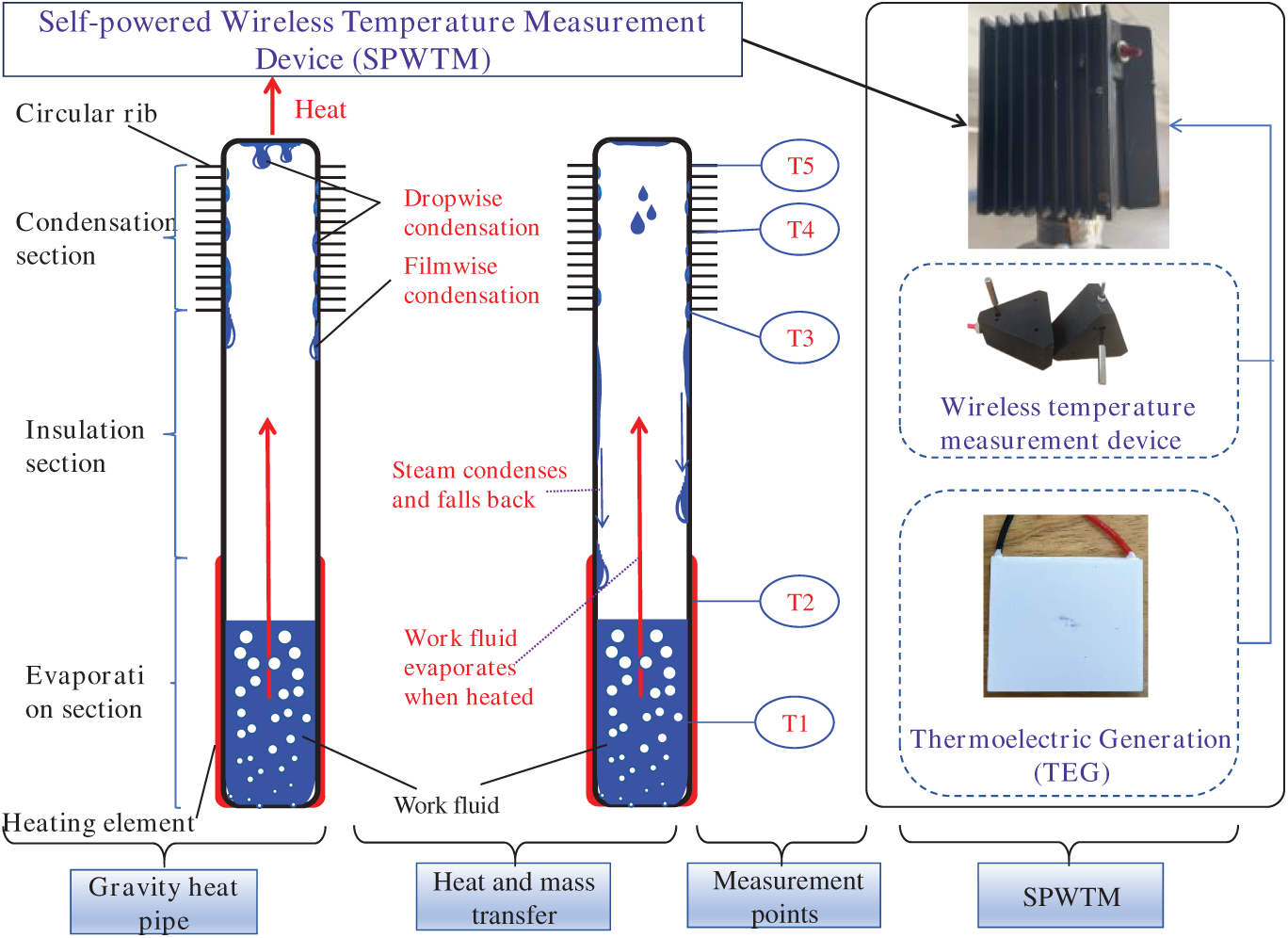

To prevent spontaneous combustion in coal stockpiles and enhance storage safety, this study develops an integrated system combining high-efficiency thermal regulation with self-powered wireless temperature monitoring. The composition and working principle of the efficient heat dissipation and self-powered wireless temperature measurement system for the coal yard is shown in Fig. 1. Thus, the device consists of a heat dissipation part and a wireless temperature measurement module. In the heat dissipation section, heat transfer is achieved by relying on the phase change heat transfer of the work mass (water) inside the gravity heat pipe (The dimensions of gravity heat pipe are height 160 cm, diameter 3 cm). The evaporation section of the heat pipe absorbs heat from the oxidised heat of the coal pile. In the condensation section, the exposed annular fins exchange heat with the ambient air through natural convection. This causes the vapor within the heat pipe to condense into numerous small droplets via dropwise condensation. These droplets gradually coalesce and form a liquid film through filmwise condensation. Under the action of gravity, the liquid film flows back to the evaporation section. Consequently, heat is transferred from the coal pile to the external environment through the gravity-assisted heat pipe. In addition, the structural parameters of the gravity heat pipe can be seen in Table 1. The fill ratio of the working fluid in the heat pipe does not vary with burial depth. The length of the condenser section remains largely consistent. In this study, the influence of coal pile depth on heat generation power is neglected. Therefore, a uniform heat flux can be applied at the evaporator section.

Figure 1: System architecture and operational principle of the high-efficiency thermal regulation and self-powered wireless monitoring system

As illustrated in Fig. 1, the SPWTM comprises a control chip, a wireless communication module, an energy management circuit, a thermoelectric generation (TEG) module, and a temperature probe (wireless sensing unit). It is installed at the end of the condenser section. The TEG modules harvest thermal energy from the heat source of the condensation section to generate electricity, which powers the wireless temperature monitoring system. Thermocouple probes integrated with the device measure condensation section temperatures and transmit readings to a cloud-based acquisition platform. The PWTM achieves ultra-low power consumption and extended battery life through several key design features. It employs an ultra-low-power control chip that operates at only 0.6 μA with a supply voltage ranging from 1.8 to 5.5 V. The wireless communication module uses an RF chip (1.9~3.6 V), which modulates data and transmits periodically every 2~5 min over a distance of 70 m. Additionally, the device incorporates a built-in 2.4 V/500 mAh miniature lithium battery. Supported by an automatic buck-boost energy management circuit (0.8~25 V), the thermoelectric generation module charges the battery in real time.

The three 12,706 thermoelectric generators in the module produce a total voltage ranging from 0.9 to 2.7 V. An energy management circuit uses this electricity to charge the battery in real time, meeting the power demand of the wireless temperature measurement device. The device employs an NTC thermistor probe for temperature sensing. Its total operating current is 30 μA, and the temperature measurement range is −50°C to +125°C. As a result, through self-powering via thermoelectric generation, the device can theoretically operate for several years, enabling long-term stable wireless temperature monitoring. Additionally, the thermoelectric materials, heat pipes, and wireless sensors used in this study are all commercially available components with minimal environmental impact.

To comprehensively evaluate the heat dissipation capacity of gravity heat pipes (GHPs) and effectively inhibit coal pile temperature escalation beyond the critical 50°C–60°C threshold—ensuring coal storage safety—this study addresses two pivotal challenges. First is the Thermal Performance Validation: Quantifying GHP efficacy in preventing thermal runaway. The second is Measurement Accuracy Optimization: Resolving condenser temperature representativeness for internal coal conditions. Ultimately, the integrated system—combining GHP-mediated thermal regulation with thermoelectric generator (TEG)—powered wireless monitoring—establishes a dual-safeguard mechanism for coal yard thermal risk management.

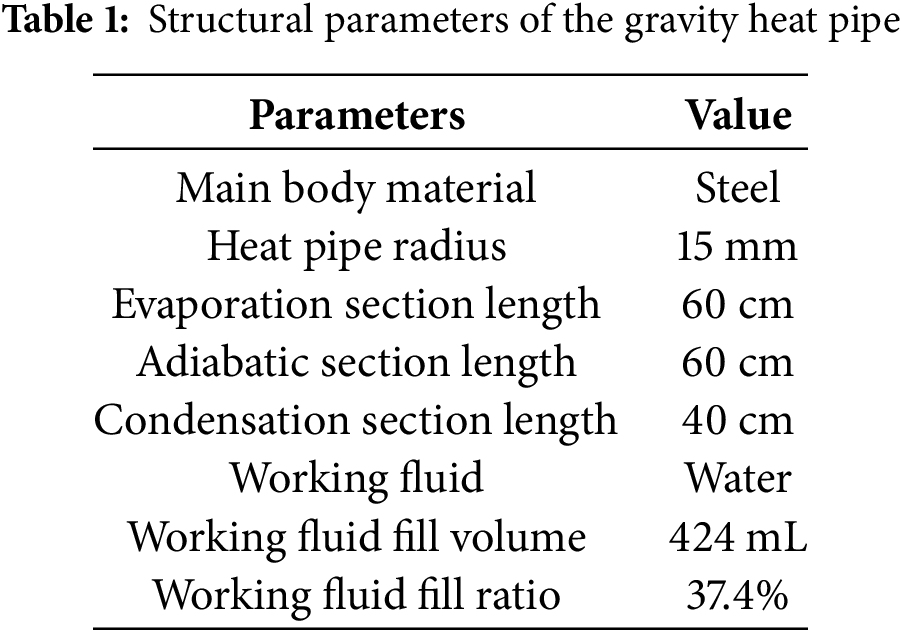

Fig. 2 presents the integrated experimental platform for performance validation and optimization of the high-efficiency thermal regulation and self-powered wireless monitoring system. The system employs electric heating patches at burial depths of 60 and 30 cm to simulate shallow and deep coal oxidation heat sources, respectively, with thermal output controlled via a DC power supply (0–200 W). Thermocouples (K-type, ±0.5°C accuracy) are axially distributed at three critical positions on both evaporator and condenser sections, with temperature data acquired by an Agilent DAQ970 system. Simultaneously, thermoelectric generator (TEG) modules mounted at the condenser apex harvest thermal energy to power wireless sensors that transmit real-time data to a cloud-based monitoring platform. Temperature streams from the cloud system and Agilent DAQ970 undergo synchronized cross-validation using dynamic calibration algorithms to achieve measurement accuracy, enabling precise thermal mapping optimization.

Figure 2: Experimental validation platform for performance evaluation of the high-efficiency thermal regulation and self-powered wireless monitoring system

3 Implementation and Field Application of Coal Yard Thermal Safety System

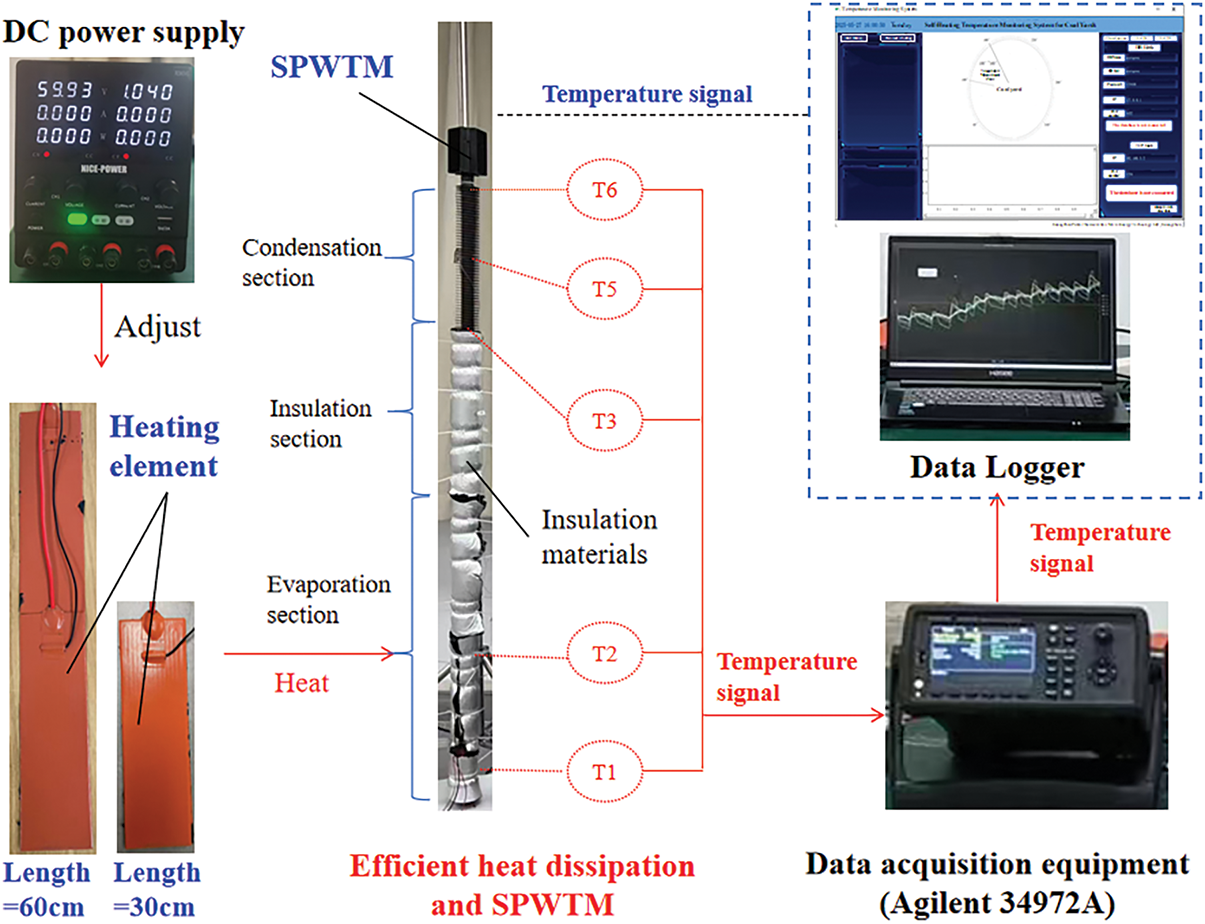

Based on the developed high-efficiency heat dissipation and self-powered wireless temperature measurement system, the application test in the coal yard is carried out. Fig. 3 is the schematic diagram of the efficient heat dissipation and self-powered wireless temperature measurement system in the coal yard temperature monitoring and early warning system.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of self-powered wireless temperature measurement device in a coal yard

Firstly, a large number of SPWTM devices are inserted into the coal pile for efficient heat dissipation using gravity-assisted heat pipes. The system operates highly automatically and can function under unattended conditions. During dynamic temperature measurement and monitoring, the thermoelectric generation module (TEG) is positioned at the top of the condenser section of the heat pipe, where it utilizes residual heat for power generation. The TEG converts thermal energy into electricity, supplying power to the SPWTM and supporting the operation of its temperature probe and wireless communication module.

Secondly, the wireless communication module inside the SPWTM transmits temperature data from the probe to a wireless base station at regular intervals of two minutes. The wireless base station delivers all collected temperature data in real time to a temperature monitoring and early warning platform. Through this platform, temperature changes and early warning information across the entire coal yard are promptly communicated to site managers.

Finally, the temperature monitoring and early warning platform performs temperature correction, real-time display, and early warning functions. It can also send commands to the SPWTM to adjust its sampling frequency.

Since the natural range of the coal pile is 60°C or more, the phase change boiling point of the work mass inside the developed gravity heat pipe is optimal at about 60°C or so. The aim is to fully utilize the heat absorption capacity of the sensible heat and the latent heat of phase change of the heat pipe work mass. Wireless temperature monitoring helps to improve the heat dissipation capacity of the gravity heat pipe. In addition, to prevent the coal pile from reaching the spontaneous ignition point (60°C), the temperature of the heat pipe’s evaporation section should not exceed 60°C.

The experimental procedure of this study is shown below.

First, the evaporative and adiabatic sections of the gravity heat pipe are insulated (see Fig. 2) to ensure that all heat is efficiently transferred to the condensing section, thus clarifying the start-up characteristics of the gravity heat pipe.

Secondly, considering that the adiabatic section in the actual application process is not installed with a heat insulation layer, the influence laws of the buried depth of the coal pile (30 and 60 cm) and the heat production power of the coal pile (The power ranges of 5~25 W and 10~50 W correspond to the same heat flux density range of 176.83 to 884.19 W/m²) on the heat transfer-heat dissipation characteristics of the gravity heat pipe are studied in depth to elucidate the overall heat transfer law of the gravity heat pipe. At the same time, the influence of the strength of natural convection heat transfer on the heat dissipation efficiency

As shown in Fig. 1, the condensing section of the heat pipe in this study uses annular cooling fins for heat dissipation. The heat dissipation efficiency

where, for annular fins, mH is calculated by Eq. (3).

Define AL = δH to denote the longitudinal cross-sectional area of the annular cooling fins.

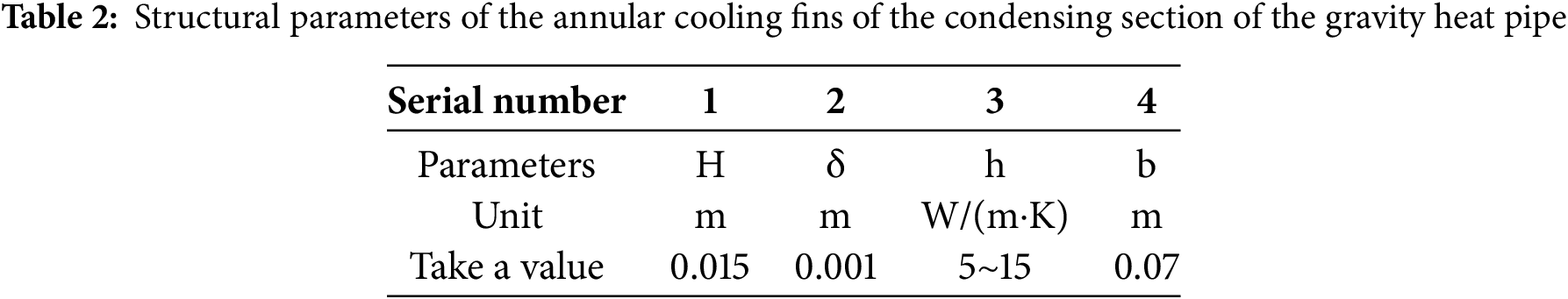

Where λ is the thermal conductivity of the material, H is the height of the rib, δ is the thickness of the rib, h is the heat transfer coefficient between the fluid and the surface of the rib, AC is the cross-sectional area along the direction of the height of the heat dissipation fins, and L is the perimeter of the cross-section of the heat dissipation fins involved in heat transfer. The spacing between the heat sink fins is b. The specific structural dimensions and parameters are shown in Table 2.

The efficiency of the ring-shaped cooling fins is

Considering that 50 pieces of annular cooling fins are used in this research system, let the temperature of the air in the coal yard be tf, the natural convection heat transfer system between the air and the cooling fins in the whole condensing section be h, the total surface area of the cooling fins be Af, the area of the root between the two cooling fins be Ar, and the temperature of the root be t0, then the sum of the area of all annular cooling fins and the root be A0, then A0 = Af + Ar. The total heat dissipation Q of the condensing section is

where

Thirdly, in order to avoid the phenomenon of high energy consumption generated by the efficient and accurate temperature measurement of the self-powered temperature measurement system and to shorten the duration of the self-powered energy supply, this study optimizes the actual measured values of the self-powered temperature measurement system, after comparing them with the temperature values measured by the high-accuracy measurement device (DAQ970). The optimization direction is to correct the temperature measurement on the temperature monitoring and warning platform by comparing the difference between the two. In the end, the high power consumption of self-powered temperature measurement systems that are self-correcting will be avoided, thus realizing effective temperature measurement over a long period of time.

Finally, the wireless temperature measurement system with high-efficiency heat dissipation and self-supply is applied in the coal yard to verify its heat dissipation performance and its ability to monitor and warn the temperature, so as to ensure the thermal safety of the coal pile in the coal yard.

5.1 Heat Transfer Characteristics of Gravity Heat Pipe

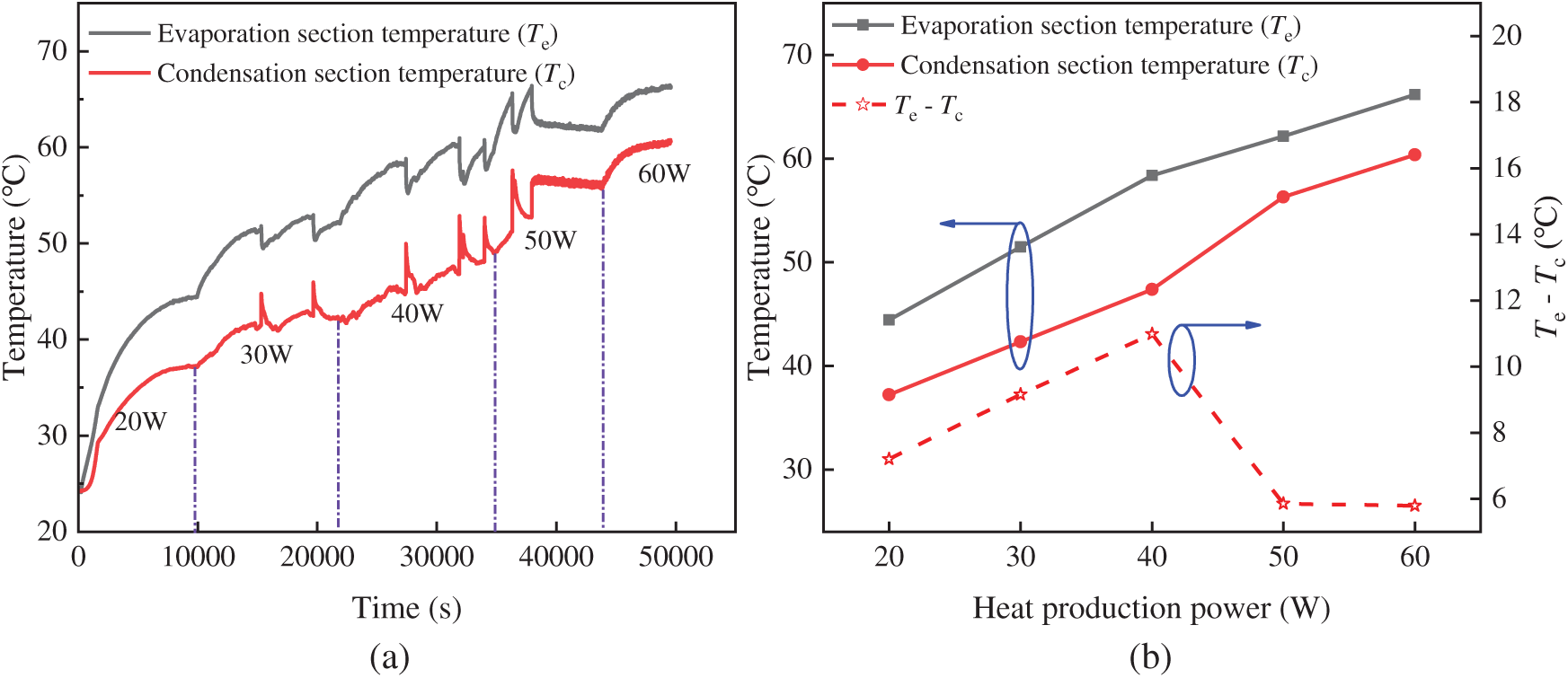

The variation of the evaporation temperature, condensation temperature, and the temperature difference between them with time and power of the gravity heat pipe when insulated in the adiabatic section is shown in Fig. 4. The effect of temperature with time and power for the evaporation and condensation sections is shown in Fig. 4a. The power to simulate the heat production from the coal pile is increased from 20 to 60 W, and the single power working interval is about 10,000 s. It can be seen that the evaporation temperature and condensation temperature of the gravity heat pipe increase with the increase of power, as shown in Fig. 4a,b. During this change, it can be roughly divided into 3 stages, a steady temperature rise stage at 20 W, an intermittent oscillating temperature rise stage at 30~40 W, and a heat pipe start-up stage at 50~60 W. The reason for this phenomenon is analyzed by combining the gravity heat pipe heat transfer process shown in Fig. 1 as follows.

Figure 4: (a) Influence of heat production power of coal pile on evaporation temperature, and condensation temperature; (b) The heat transfer temperature difference of gravity heat pipe when insulated in adiabatic section (burial depth 60 cm)

During the steady rise phase at 20 W, the steam generation inside the gravity heat pipe is small due to the low power input. Some of the heat is transferred through the walls of the heat pipe, while a small amount of heat is transferred through water evaporation. At this time, the water vapor in the condensing section undergoes a bead-like condensation process, with a small number of water droplets adhering to the inside of the tube. As a result, the temperature rise is very stable with a smooth curve.

As the power increases to 30~40 W, the temperature of the evaporation section increases and gradually approaches 60°C, resulting in a continuous increase in vapor generation inside the heat pipe. At this time, the bead-like condensation process in the condensing section part of the heat pipe increases significantly. A large number of small water beads merge and grow, and some of the beads grow too large and form a liquid film, which flows back under the action of gravity (see the heat and mass transfer analysis in Fig. 1). The heat transfer temperature difference between the condensing section and the evaporating section as shown in Fig. 4b. It can be seen that the liquid film or condensate temperature in the condensing section is lower than that in the evaporating section. When the condensate flows back, the condensing section temperature is heated by the high-temperature steam and warms up instantly. On the contrary, the evaporator section receives the low-temperature condensate and cools down instantly. In summary, the intermittent temperature oscillations between the evaporating section and condensing section of the heat pipe at 30 to 40 W are caused by discontinuous condensate return.

At the power of 50 to 60 W, the amount of vapor produced inside the heat pipe increases further. The amount of bead-like condensation produced in the condensing section increases significantly. At this time, the frequency of condensate return increases, causing continuous oscillations in the temperature of the evaporation and condensation sections. However, when the 50 W power is operated for some time, the condensate reaches a continuous and stable reflux state, which makes the evaporation section temperature and condensation section temperature change curves, stable and smooth. The heat transfer temperature difference between the evaporation section and the condensation section shown in Fig. 4b is significantly reduced, and the heat pipe homogeneity is significantly increased, indicating that the gravity heat pipe is successfully activated internally. The start-up temperature is about 60°C, while the start-up power and the length of the evaporation section are 50 and 60 cm, respectively.

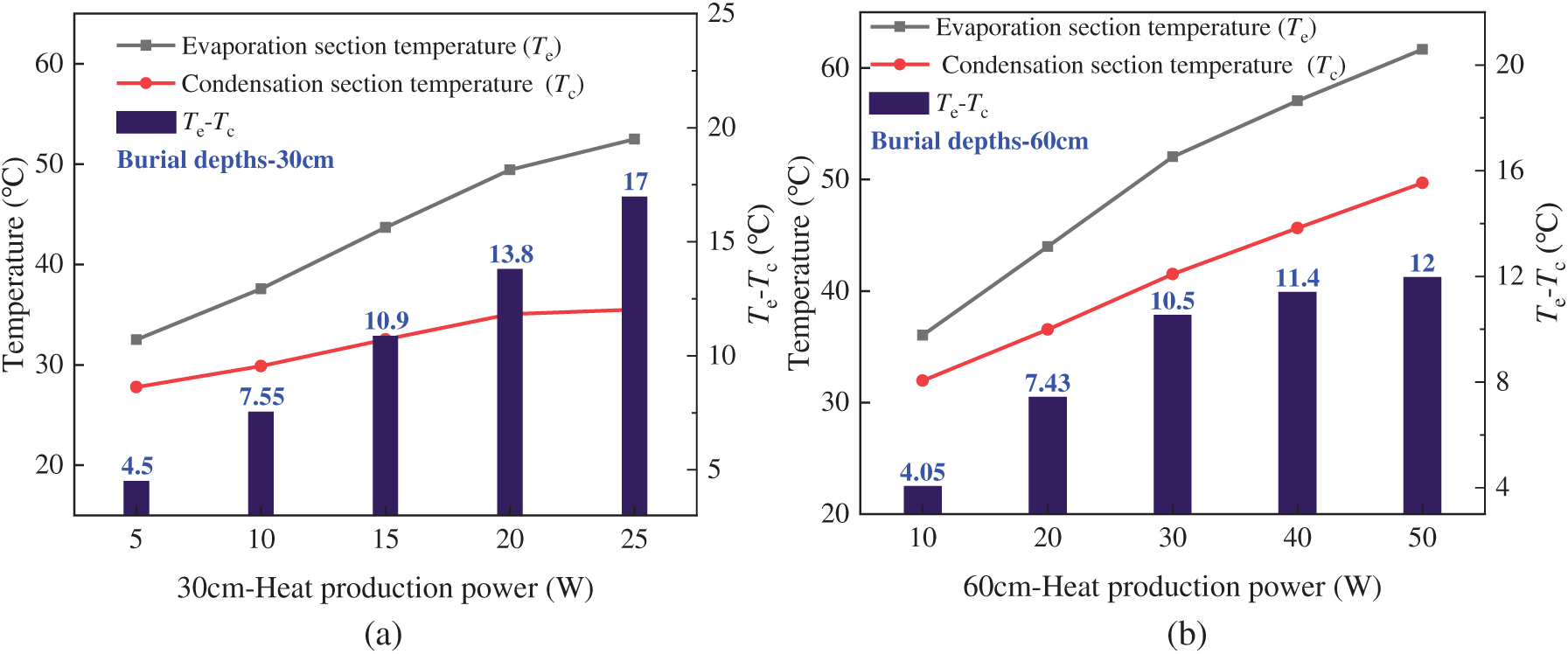

5.2 Influence of Coal Pile Burial Depth and Heat Production Power

During the installation and application of SPWTM in coal piles, the adiabatic section is usually installed without thermal insulation. Therefore, when the adiabatic section is not insulated, the effect of the depth of the coal pile burying the SPWTM and the oxidized heat production power of the coal mine on the SPWTM is of concern. The heat production power should be consistent under the same coal mine. In other words, the heat generation power of coal mines per unit depth is consistent. Here, the parameters of burial depth were investigated as 30 and 60 cm, and the heat production power was 5~25 W and 10~50 W, respectively.

The influence of coal pile heat production power and burial depth on heat pipe evaporation temperature, condensation temperature, and heat transfer temperature difference when the adiabatic section is not insulated is shown in Fig. 5a,b. Overall, the evaporation and condensation temperatures and the temperature difference between them increase due to the increase in power, regardless of whether the adiabatic section is insulated or not. However, the evaporation and condensation temperatures at a burial depth of 30 cm are lower than those at a burial depth of 60 cm. This is because the heat produced in the coal mine is transferred through the adiabatic section and the condensation section. Therefore, the shallower the burial depth, the stronger the heat dissipation ability, making the temperature of the evaporation section slightly lower. Because of this, the shallower the burial depth is, the greater the temperature difference between the evaporation section and the condensation section.

Figure 5: Effect of coal pile heat production power and burial depth on heat pipe evaporation temperature, condensation temperature, and heat transfer temperature difference when the adiabatic section is not insulated. (a) 30 cm, 5~25 W; (b) 60 cm, 10~50 W

As shown in Fig. 5a,b, the maximum temperature difference is as high as 17°C and 12°C for 30 and 60 cm burial depth, respectively. The evaporator sections maintain an identical heat flux density of 884.19 W/m², achieved by applying power inputs of 25 W for the 30 cm case and 50 W for the 60 cm case. This phenomenon occurs because the configuration with 30 cm depth provides a larger total surface area, including both the condenser and uninsulated sections. The increased area enhances heat dissipation and reduces condenser temperature, thereby amplifying the heat transfer temperature difference between the evaporator and condenser sections. Moreover, compared to the 6°C temperature difference between the evaporator and condenser at 50 W in Fig. 4b, the uninsulated adiabatic section exhibits a temperature difference of only 12°C. This occurs due to heat loss from the uninsulated section, which reduces condensate accumulation in the condenser at 50 W. Approximately 18.2% of the total heat dissipation area contributes to this environmental heat loss. Consequently, under uninsulated conditions at 50 W, continuous large-scale condensate return to the evaporator does not occur, resulting in a higher temperature difference between the condenser and evaporator. The smaller the heat transfer temperature difference, the smaller the difference between the condensing section temperature and the evaporation temperature. The actual measurement value of the self-powered wireless temperature measurement system is the condensation section temperature. Therefore, the results show that the deeper the burial depth and the smaller the heat production power, the higher the measurement accuracy of the self-powered wireless temperature measurement device.

The thermal safety of coal piles is improved here to efficiently prevent spontaneous combustion of coal piles. Early warning is performed before the coal pile reaches the spontaneous combustion temperature point of 60°C. As shown in Fig. 5b, if the warning temperature of the coal pile is selected to be 50°C, the temperature difference (Th − Tc) between the evaporation section and condensation section of the gravity heat pipe is close to 10°C. In other words, the difference between the self-powered wireless temperature measurement value and the actual temperature of the coal pile is less than 10°C before the temperature of the coal pile reaches 50°C. Based on Th − Tc ≤ 10°C, it is proposed to add 10°C to the self-powered wireless temperature measurement feedback value to improve the reliability of temperature monitoring. This approach serves as a simplified expedient for measurement error correction rather than a comprehensive solution. It represents a trade-off between measurement accuracy and system power consumption for extended operational longevity. For a more complete error correction method, one may consider constructing a high-precision dynamic compensation model based on real-time heat flux density or heat pipe operating status to improve measurement accuracy. In addition, it is suggested that the burial depth of SPWTM should be greater than 60 cm in practical applications.

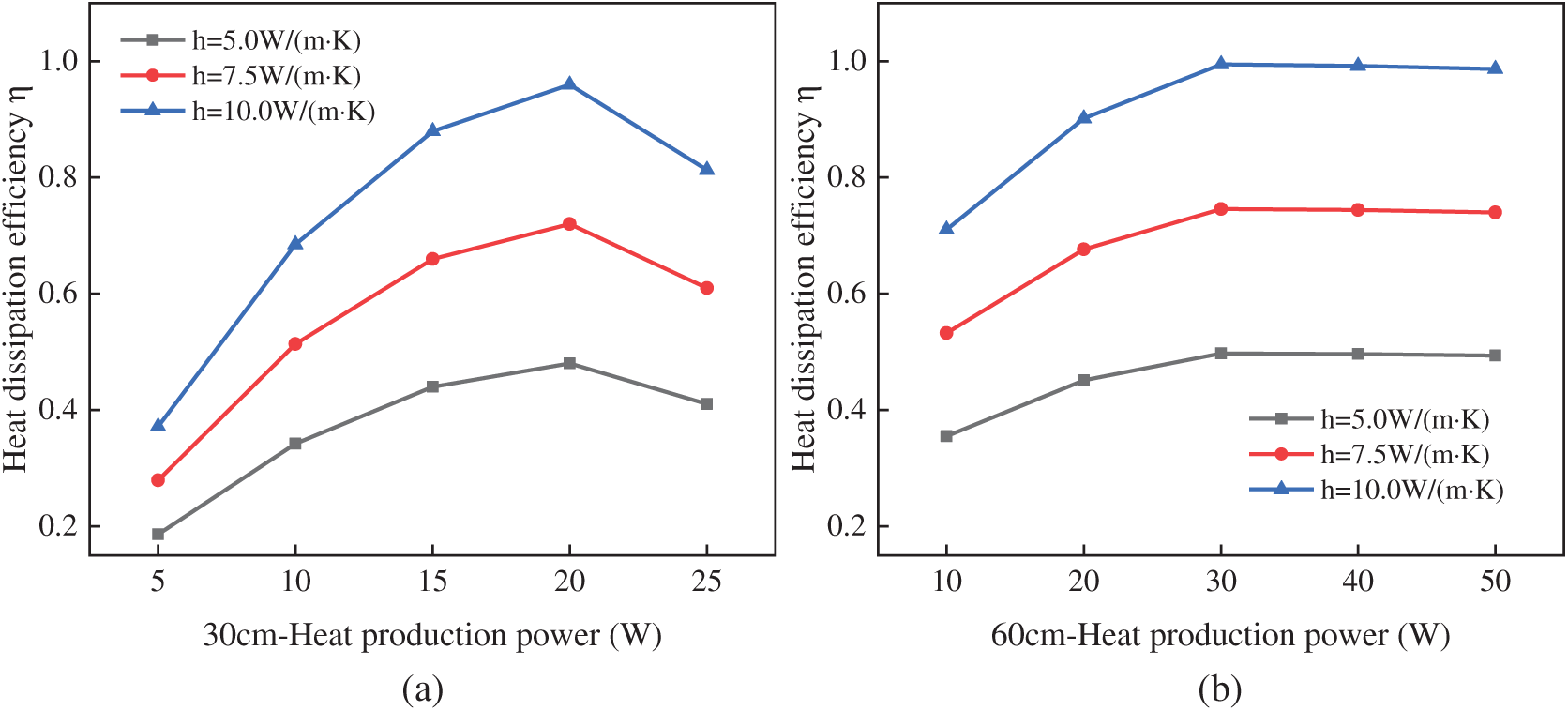

To demonstrate the effect of burial depth on heat transfer performance, in particular, the effect of the intensity of natural convection of air on the heat dissipation capacity of the condensing section was explored, as shown in Fig. 6, the effects of burial depth and heat production power on the heat dissipation efficiency

Figure 6: Effect of coal pile heat production power and burial depth on the heat dissipation efficiency

Unlike a burial depth of 30 cm, the heat dissipation capacity of a heat pipe with a burial depth of 60 cm depends on the heat sink fins in the condensing section. Therefore, the heat transfer area of the heat sink fins at 60 cm is a larger percentage of the total heat transfer area. It can be seen that as the heat production power increases, the heat dissipation efficiency first increases and then levels off. Equal efficiency after 30 W indicates that the heat dissipation capacity has reached its maximum value. The resistance to heat dissipation reflected laterally comes from the natural convection surface heat transfer coefficient. Therefore, the higher the natural convection heat transfer coefficient, the greater the heat dissipation capacity and efficiency. In summary, in deeper burial depth conditions, the heat dissipation capacity and heat dissipation efficiency of the gravity heat pipe are greater, which contributes to the efficient heat dissipation of the coal pile. When the natural convection heat transfer coefficient is 10 W/(m·K), the heat dissipation efficiency based on the cooling fins in the condensing section is as high as 0.98. The heat dissipation efficiency of the condensing fins is as high as 0.98.

5.3 Research on Optimization Strategy of Temperature Measurement

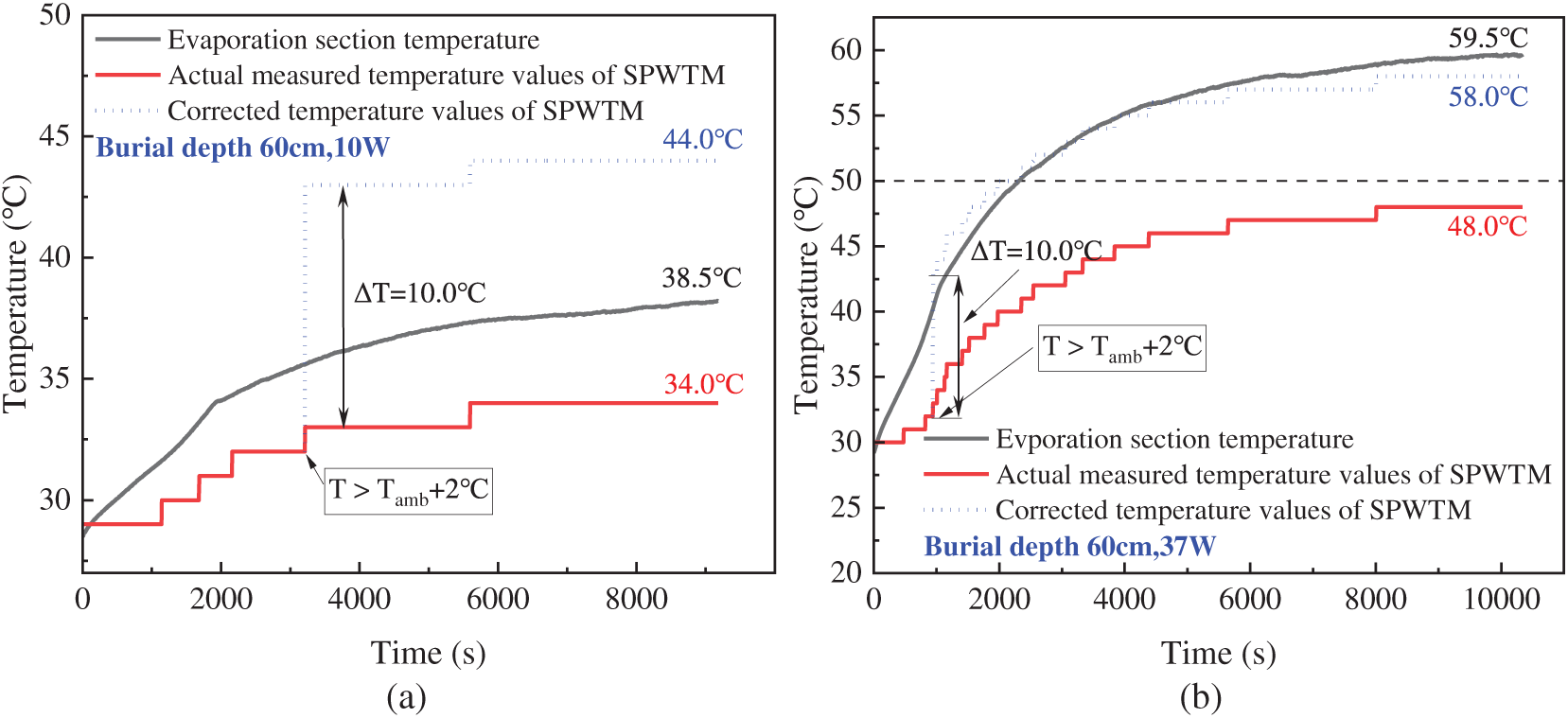

Based on the results obtained in Fig. 5, it is proposed to add 10°C to the actual value of the self-powered wireless temperature measurement to improve the reliability of temperature monitoring. This is the result of combining the temperature monitoring with the heat transfer characteristics of the gravity heat pipe. As shown in Fig. 7, the temperature of the evaporation section slowly changes to increase to 38.5°C when the heat production power is 10 W. Due to the heat transfer temperature difference between the evaporating and condensing sections of the heat pipe, the measured temperature of the SPWTM at the top of the condensing section is lower than the temperature of the evaporating section, which makes it impossible to obtain an accurate temperature of the coal pile. Based on the above-mentioned optimization method of “adding 10°C to the actual value of self-powered wireless temperature measurement”, the reliability of coal yard temperature monitoring is guaranteed. In Fig. 7a, it is shown that when the measured temperature value of SPWTM is 2°C higher than the ambient temperature, 10°C is added to the measured temperature value of SPWTM. The temperature correction value of SPWTM is higher than the evaporation temperature.

Figure 7: Comparison of the actual measured temperature values of the SPWTM with the corrected values and the actual measured temperature values of the evaporation section for the heat production power of (a) 10 W and (b) 37 W, respectively

The temperature correction value of SPWTM optimized by this method is also very reliable at higher heat production power. As shown in Fig. 7b, the temperature correction value of SPWTM is very close to the evaporation section temperature (coal pile temperature) at 37 W. Specifically, the measured temperature correction value of SPWTM is very close to the evaporation temperature (coal pile temperature) 42.5°C to 55°C curve. Comparing the correction results in Fig. 7a,b, the results show that the higher the coal pile temperature is before reaching the warning temperature of 50°C, the closer the temperature correction value of SPWTM is to the actual coal pile temperature. Therefore, the higher the coal pile temperature is, the more accurate the warning results of SPWTM are, which helps to ensure the thermal safety of the coal yard. It is worth noting that in order to reduce the energy consumption of SPWTM, the optimization or correction runs are carried out in the temperature monitoring and warning platform.

5.4 Application and Analysis of Long-Time Coalfield Temperature Monitoring

5.4.1 Coalfield Field Application Cooling Effect

The temperature correction of SPWTM was performed based on the above temperature measurement optimization results. Then, field operation in coal pile temperature monitoring in the coal yard was conducted to evaluate the heat dissipation capability of this efficient heat dissipation & self-powered wireless temperature measurement system (Efficient heat dissipation & SPWTM) and the warning capability of the temperature warning platform. The key field conditions declared for the coal stockyard include the type of coal, burial depth, and weather condition. Specifically, the coal is high-sulfur lignite, the burial depth is no less than 60 cm (as supported by findings from Figs. 6 and 7), and the weather condition is sunny.

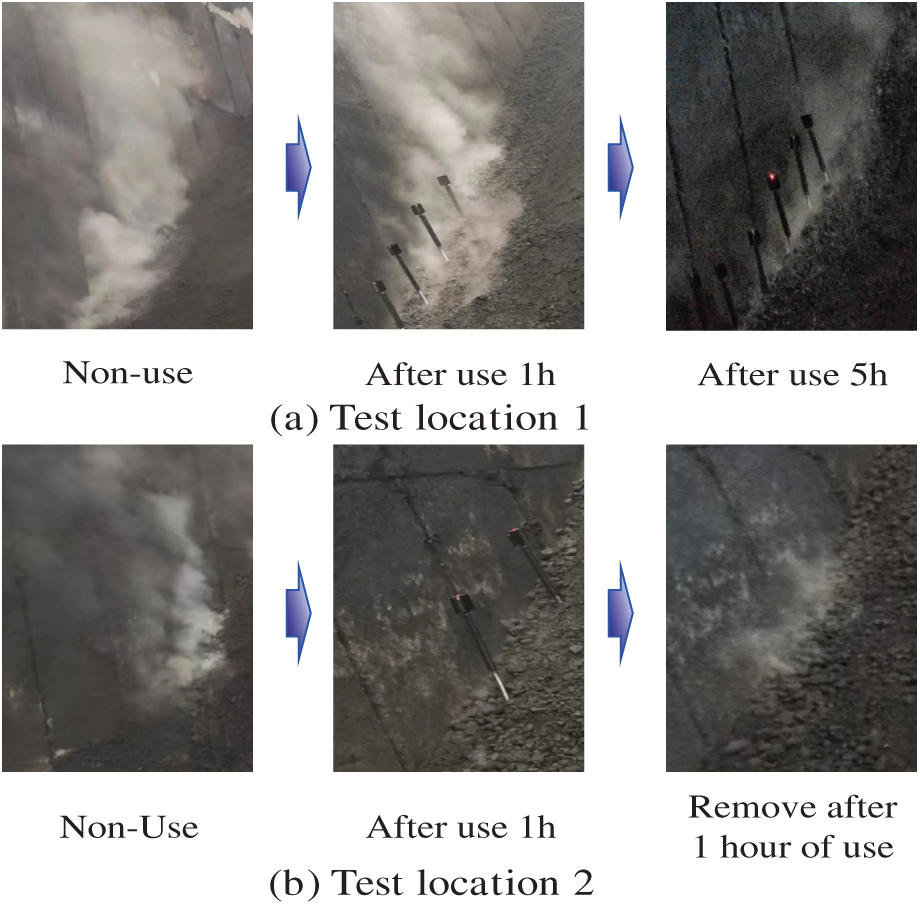

Fig. 8 demonstrates the actual use of two highly efficient heat dissipation and self-powered wireless temperature measurement systems in a coal pile. These temperature measurement devices are used in a coal-fired power plant in Southwest China. In test point 1 of Fig. 8a, without the use of Efficient heat dissipation & SPWTM, the temperature of the coal pile reaches the ignition point due to the oxidation reaction of the coal, and a large amount of white smoke is generated. After using Efficient heat dissipation & SPWTM for 1 to 5 h, the white smoke in the coal pile was significantly reduced. Similarly, in Test Point 2 of Fig. 8b, there was a slight amount of white smoke without the use of a heat dissipation device. The white smoke suddenly disappeared 1 h after using Efficient heat dissipation & SPWTM and reappeared or rekindled 1 h after removing the heat sink. Based on the above analysis, it shows that the gravity heat pipe in Efficient heat dissipation & SPWTM plays a key role in heat dissipation, which helps to reduce the temperature of the coal pile and inhibit the spontaneous combustion of coal.

Figure 8: Practical use of two high-efficiency heat dissipation and self-powered wireless temperature measurement systems in a coal pile, (a) test position 1, (b) test position 2

5.4.2 Coalfield-Wide Temperature Monitoring and Early Warning

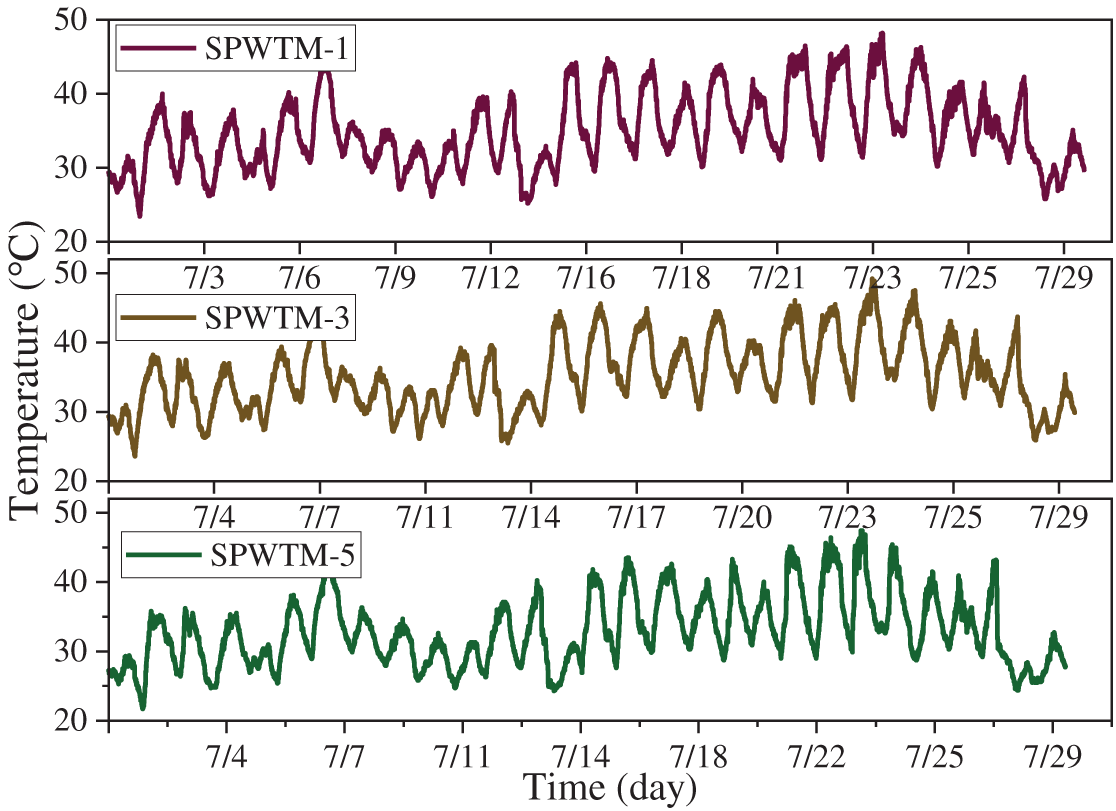

The function of Efficient heat dissipation & SPWTM is not only to dissipate the heat from the coal pile and inhibit the burning of coal utilizing gravity heat pipe but also the temperature monitoring of its SPWTM is equally important. In the coal pile temperature monitoring process, the optimized temperature monitoring and warning platform receives temperature information from all SPWTMs. In this study, six temperature measurement points at the same coal pile are demonstrated. Fig. 9 shows the coal pile information of July 2024 in the coal yard for 3 SPWTMs. It can be seen that based on the self-powered nature of the SPWTM, it can work continuously for at least up to one month without maintenance. Compared with the artificial or active power supply temperature measurement method, the maintenance and labor costs are greatly reduced. In addition, the temperature information measured by the three SPWTMs shows the same trend over time. This indicates the accuracy of SPWTM temperature measurement. In the middle of July, the overall temperature of the coal pile first increased, then decreased, and then increased. With the temperature change of SPWTM, the coal yard managers can effectively analyze the temperature trend of the coal yard. If the temperature is too high, measures such as cooling can be applied in advance.

Figure 9: Coalfield temperatures measured by different SPWTM in the coalfield over time in July

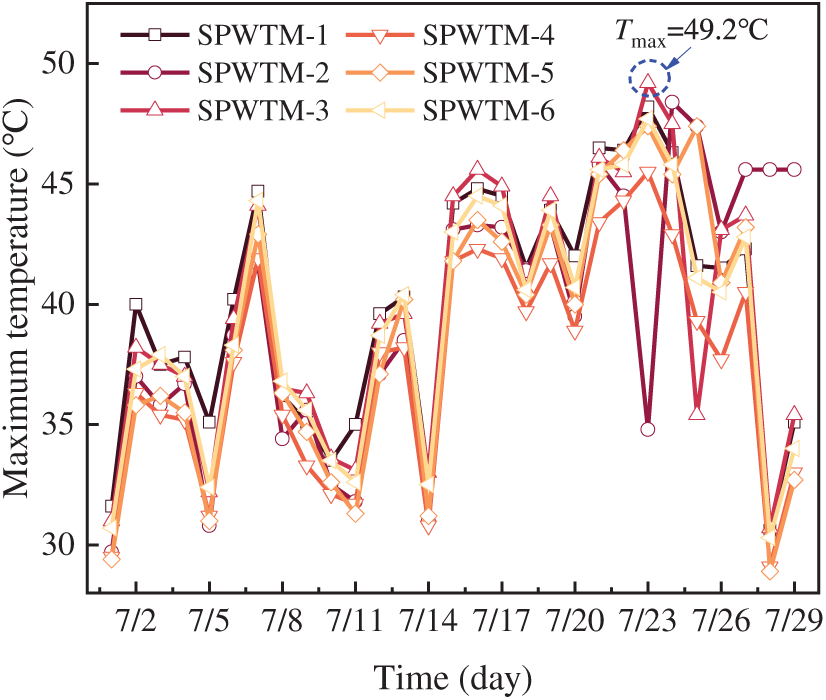

The maximum coal pile temperatures measured at several SPWTMs for July are shown in Fig. 10. As a whole, the maximum temperature variations were essentially the same for almost all SPWTMs. Moreover, the maximum coal pile temperatures were inconsistent from day to day, with very large variations. However, it was observed that on 7/23, the maximum temperature of SPWTM-2 showed a sharp decrease, which was different from the other SPWTMs. This was caused by the fact that the coal mine at SPWTM-2 was moved and sold and the heat production from the coal disappeared. It was also found that the maximum temperature of the coal pile through efficient heat dissipation by gravity heat pipe did not exceed 49.2°C, which again proved the reliability of heat dissipation of the system in this study.

Figure 10: Maximum coal pile temperatures measured at six SPWTMs in mid-July

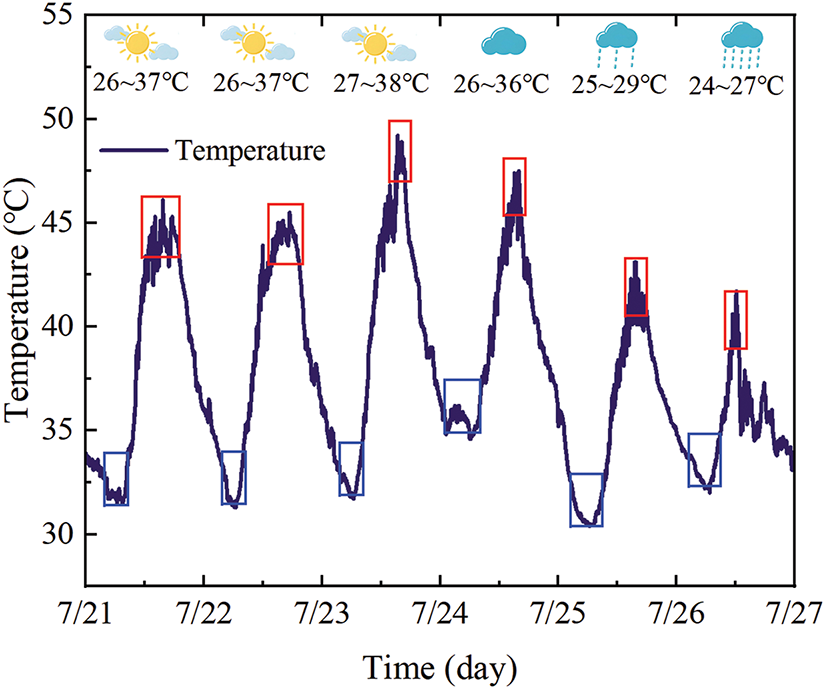

In Fig. 10, the time of the highest temperature is located from 7/21 to 7/27, 2024. For this purpose, SPWTM-3, where the highest temperature occurs, was extracted, and the period of the temperature measurements is from 7/21 to 7/27. In Fig. 11, the temperature change of SPWTM-3 from 7/21 to 7/27 is demonstrated. Based on Fig. 11, three main arguments were obtained.

Figure 11: Temperature change of SPWTM-3 from 7/21 to 7/27

First, all the blue and red boxes indicate the temperatures in the morning hours (5:00~8:00) and afternoon hours (13:00~15:00), respectively. The highest and lowest temperatures occur in these two time periods, which are in line with the daily temperature change pattern, and again demonstrate the reliability of SPWTM temperature measurement.

Secondly, the temperature oscillates significantly in the afternoon period when the maximum temperature occurs, a change process that is consistent with the reasons analyzed in Fig. 4. The reason is that at high temperatures, the cold water in the condensing section of the gravity heat pipe flows back to the evaporating section from time to time, resulting in temperature oscillations in the condensing section and the evaporating section at the same time.

Thirdly, the temperature variations of SPWTM-3 were related to the weather in the place where this coal yard belongs to (Ruijin, Jiangxi, China). The weather forecast for 7 days time is located at the top of Fig. 11. As shown in Fig. 11, during the three days from 7/21 to 7/24, the weather was mainly sunny and cloudy. The maximum temperature values were relatively high at 37°C~38°C, and the corresponding coal pile temperatures likewise appeared high at about 45°C~50°C. During the three days from 7/24 to 7/27, the temperature of the coal pile was decreasing due to the occurrence of increasing rainfall. It can be seen that the rainfall weather contributes to the thermal safety of the coal yard.

As shown above, the Efficient heat dissipation & SPWTM developed in this study realize double safety for the coal yard. The efficient heat dissipation of the heat pipe reduces the temperature of the coal yard to the spontaneous combustion temperature of the coal pile, so that the spontaneous combustion phenomenon in the coal pile can be significantly suppressed within 1~5 h, and the fastest time is 1 h. Because the white smoke produced by the spontaneous combustion of coal is significantly reduced. At the same time, the temperature measurement reliability of the self-supplied wireless temperature measurement system is optimized to achieve accurate monitoring and early warning of the temperature trend of the coal pile in the coal yard. The results of temperature oscillations of the obtained experimental tests (Fig. 4) and weather variations are argued one by one in Fig. 11. In addition, the thermoelectric power generation module utilizes the waste heat from the condensing section of the gravity heat pipe to generate electricity, which can be used for the wireless temperature measurement system to achieve continuous energy supply for at least 1 month (This conclusion is obtained from field measurements conducted in July (summer) under both sunny and rainy conditions, as shown in Fig. 9.). This study is of great significance for the development of temperature monitoring and early warning systems under long-duration and unattended operation at the coal yard.

To curb the spontaneous combustion of coal piles caused by the oxidizing reaction between coal and air during the coal stacking process, in this study, an efficient heat dissipation & self-powered wireless temperature measurement system (SPWTM) integrating gravity heat pipe and thermoelectric power generation was developed to provide a double safeguard against spontaneous combustion of coal. The main research results are as follows:

(1) The temperature change characteristics under different coal pile heat production power and burial depths were studied experimentally to clarify the heat transfer characteristics and startup characteristics of the gravity heat pipe. The process of stabilizing the temperature of the evaporation section and the temperature of the condensation section of the gravity heat pipe, as well as the process of decreasing the temperature difference between the two, are analyzed. That is, when the thermal resistance of heat transfer by phase change of the work material becomes small, the startup temperature of the heat pipe is about 60°C. The influence of the natural convection heat transfer coefficient on the heat dissipation efficiency of the condensing section points out that the burial depth of 60 cm can guarantee efficient heat dissipation of the gravity heat pipe. Specifically, at a burial depth of 60 cm, the heat dissipation efficiency of the condensing section remains highly stable for power values above 30 W. The maximum efficiency reaches approximately 98%.

(2) The heat transfer temperature difference between the evaporation section and condensation section of the gravity heat pipe makes it inevitable that there is a measurement error in the measured temperature value. Based on the change of burial depth on the value of heat transfer temperature difference between the evaporation section and condensation section, the optimized correction method of superimposing 10°C is proposed for the actual temperature measurement value of SPWTM. The measured value plus 10°C is taken as the actual coal pile temperature value to realize efficient and accurate early warning. This optimization method means that the higher the coal pile temperature, the closer the temperature correction value of SPWTM is to the actual temperature of the coal pile. Therefore, the more accurate the early warning result of SPWTM is, the more it will help to guarantee the thermal safety of the coal yard.

(3) In the practical application of the coal yard, the efficient heat dissipation & self-supply wireless temperature measurement system reduces the coal yard temperature to below the spontaneous combustion temperature of the coal pile with the help of the efficient heat dissipation of the heat pipe. The spontaneous combustion phenomenon in the coal pile is suppressed within 1~5 h, the fastest one hour. Moreover, the maximum temperature of the actual coal pile does not exceed 49.2°C. The thermoelectric power generation module utilizes the waste heat from the condensing section of the gravity heat pipe to generate electricity, which can be used to supply the wireless temperature measurement system and the safety warning for at least 1 month without maintenance, thus ensuring the thermal safety of the coal pile again.

Outlook: It is evident that the SPWTM system facilitates temperature measurement and enables efficient early-warning monitoring in coal stockyards. However, fluctuations in TEG output power limit its temperature monitoring frequency (e.g., once every 2 min) and long-term continuous operation capability. Under prolonged shadow weather, low temperatures in autumn and winter, or conditions involving low-calorific-value coal, the power generation of the TEG decreases significantly. This reduction may compromise the system’s ability to maintain long-term stable and high-precision temperature monitoring. Therefore, further research is necessary to investigate the thermodynamic mechanisms of heat transfer in gravity-assisted heat pipes across different types of coal piles and to optimize temperature monitoring performance. These efforts will enhance the system’s reliability and adaptability in practical applications.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work is supported by the Engineering Research Centre for Digital Grid Technology for Coordinating New Energy under Grant [Grant number 2021GCZX003]; Yunnan Fundamental Research Projects under Grant [Grant number 202301CF070031]; Hundred Talents Project 2023 under Grant [Grant number B0201001]; 2024 Distinctive Innovation Scientific Research Projects for Higher Education Institutions [Grant number 2024KTSCX157]; and the Young Innovative Talent Project under Grant [Grant numbers K0223021, K0224014].

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Tao Lin, Chengdai Chen; data collection: Liyao Chen; analysis and interpretation of results: Fengqin Han, Guanghui He; draft manuscript preparation: Chengdai Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data are available on request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wu XD, Xia XH, Chen GQ, Wu XF, Chen B. Embodied energy analysis for coal-based power generation system-highlighting the role of indirect energy cost. Appl Energy. 2016;184:936–50. doi:10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.03.027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Gao D, Guo L, Wang F, Zhang Z. Study on the spontaneous combustion tendency of coal based on grey relational and multiple regression analysis. ACS Omega. 2021;6(10):6736–46. doi:10.1021/acsomega.0c05736. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Liu Y, Wen H, Chen C, Guo J, Jin Y, Zheng X, et al. Research status and development trend of coal spontaneous combustion fire and prevention technology in China: a review. ACS Omega. 2024;9(20):21727–50. doi:10.1021/acsomega.4c00844. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Fujitsuka H, Ashida R, Kawase M, Miura K. Examination of low-temperature oxidation of low-rank coals, aiming at understanding their self-ignition tendency. Energy Fuels. 2014;28(4):2402–7. doi:10.1021/ef402484u. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhou A, An J, Wang K, Zhang J, Liu Y, Wang J, et al. Modeling and parametric analysis of low-temperature oxidative self-heating in coal stockpiles driven by natural convection. Fuel. 2024;361:130670. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2023.130670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Garcia Torrent J, Fernandez Anez N, Medic Pejic L, Montenegro Mateos L. Assessment of self-ignition risks of solid biofuels by thermal analysis. Fuel. 2015;143:484–91. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2014.11.074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Vikram M, Bhattacharjee RM, Paul PS. Determination of spontaneous combustion propensity and ignition time of Indian coal using adiabatic oxidation method. Fuel. 2025;388:134569. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2025.134569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Choi H, Jo W, Kim S, Yoo J, Chun D, Rhim Y, et al. Comparison of spontaneous combustion susceptibility of coal dried by different processes from low-rank coal. Korean J Chem Eng. 2014;31(12):2151–6. doi:10.1007/s11814-014-0174-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Zhang Y, Liu Y, Shi X, Yang C, Wang W, Li Y. Risk evaluation of coal spontaneous combustion on the basis of auto-ignition temperature. Fuel. 2018;233:68–76. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2018.06.052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Muthu Kumaran S, Raghavan V, Rangwala AS. A parametric study of spontaneous ignition in large coal stockpiles. Fire Technol. 2020;56(3):1013–38. doi:10.1007/s10694-019-00917-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhang Y, Song Z, Wu D, Luo Z, Zhao S, Wang Y, et al. Prediction of coal self-ignition tendency using machine learning. Fuel. 2022;325:124832. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.124832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhao J, Meng R, Yuan S, Wang B. Research on spontaneous combustion characteristics and high temperature point prediction method of rectangular coal pile. Int J Coal Prep Util. 2024;44(12):2240–56. doi:10.1080/19392699.2024.2316664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Deng J, Chen WL, Liang C, Wang WF, Xiao Y, Wang CP, et al. Correction model for CO detection in the coal combustion loss process in mines based on GWO-SVM. J Loss Prev Process Ind. 2021;71:104439. doi:10.1016/j.jlp.2021.104439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bhar I, Mandal N. A review on advanced wireless passive temperature sensors. Measurement. 2022;187:110255. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2021.110255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Masud M, Vazquez P, Rehman MRU, Elahi A, Wijns W, Shahzad A. Measurement techniques and challenges of wireless LC resonant sensors: a review. IEEE Access. 2023;11:95235–52. doi:10.1109/access.2023.3309300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Cai T, Gao G, Wang M, Wang G, Liu Y, Gao X. Experimental study of carbon dioxide spectroscopic parameters around 2.0 μm region for combustion diagnostic applications. J Quant Spectrosc Radiat Transf. 2017;201:136–47. doi:10.1016/j.jqsrt.2017.07.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Fierro V, Miranda JL, Romero C, Andrés JM, Arriaga A, Schmal D, et al. Prevention of spontaneous combustion in coal stockpiles. Fuel Process Technol. 1999;59(1):23–34. doi:10.1016/S0378-3820(99)00005-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Qiu X, Wei Y, Li J, Zhang E, Li N, Li C, et al. Early detection system for coal spontaneous combustion by laser dual-species sensor of CO and CH4. Opt Laser Technol. 2020;121:105832. doi:10.1016/j.optlastec.2019.105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li C, Chen K, Guo M, Zhao X, Qi H, Zhang G, et al. Intrinsically safe fiber-optic photoacoustic gas sensor for coal spontaneous combustion monitoring. IEEE Trans Instrum Meas. 2022;71:1–9. doi:10.1109/tim.2022.3184343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Yue Y, Wang S, Shen Y. Spout deflection in spouted beds and countermeasures: a review. Powder Technol. 2021;389:309–27. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2021.05.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Zhang J, An J, Zhou A, Wang K, Si G, Xu B. Development and parameterization of a model for low-temperature oxidative self-heating of coal stockpiles under forced convection. Fuel. 2023;339:127349. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.127349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Sun W, Zhang Y, Wang F, Li Y, Gao D, Li J, et al. Microscopic analysis of the differential low-temperature oxidation ability of coal. Energy. 2025;325:136048. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.136048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ma L, Fan X, Wei G, Sheng Y, Liu S, Liu X. Preparation and characterization of antioxidant gel foam for preventing coal spontaneous combustion. Fuel. 2023;338:127270. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2022.127270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yin C, Jiang S, Zhao Y, Wu Z, Xi X. Study on optimization of preparation and liquid content of thermo-responsive inhibitor for preventing coal spontaneous combustion. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;253:123763. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.123763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Zhang Y, Shu P, Zhai F, Chen S, Wang K, Deng J, et al. Preparation and properties of hydrotalcite microcapsules for coal spontaneous combustion prevention. Process Saf Environ Prot. 2021;152:536–48. doi:10.1016/j.psep.2021.06.021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Tyagi VV, Pandey AK, Buddhi D, Kothari R. Thermal performance assessment of encapsulated PCM based thermal management system to reduce peak energy demand in buildings. Energy Build. 2016;117:44–52. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2016.01.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lu W, Liu Y, Zhang L, Liu F, Wu J, Zhan Z, et al. Flow and heat transfer characteristics of a new coke oven gas Ascension pipe heat exchanger: experimental validation and numerical study. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2025;60:103386. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2025.103386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Nikolaenko YE, Pekur DV, Sorokin VM, Кravets VY, Melnyk RS, Lipnitskyi LV, et al. Experimental study on characteristics of gravity heat pipe with threaded evaporator. Therm Sci Eng Prog. 2021;26:101107. doi:10.1016/j.tsep.2021.101107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhang T, Cai J, Wang L, Meng Q. Comparative and sensitive analysis on the filling, operating and performance patterns between the solar gravity heat pipe and the traditional gravity heat pipe. Energy. 2022;238:121950. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.121950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Dai J, Tian ZJ, Shi XY, Lu Y, Chi WL, Zhang Y. Research progress on gravity heat pipe technology to prevent spontaneous combustion in coal storage piles. MRS Commun. 2024;14(4):480–8. doi:10.1557/s43579-024-00559-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Jin L, Wang S, Guo J, Li H, Tian X. Performance study of gravity-type heat pipe applied to fuel cell heat dissipation. Energies. 2023;16(1):563. doi:10.3390/en16010563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhai Y, Zhao X, Dong Z. Research on performance optimization of gravity heat pipe for mine return air. Energies. 2022;15(22):8449. doi:10.3390/en15228449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ma Q, Chen J, Huang W, Li Z, Li A, Jiang F. Power generation analysis of super-long gravity heat pipe geothermal systems. Appl Therm Eng. 2024;242:122533. doi:10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2024.122533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Zhang X, Wang T, Zhang X, Ge S. Analysis of multiple factors influencing the efficiency of gravity thermal pipe waste heat recovery: a case study of heat accumulation management in spoil tips. Energy. 2025;322:135526. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2025.135526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Zhang Y, Quan X, Ning N, Wang J. Experimental study on heat extraction from coal pile by heat pipe. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2020;446(2):022065. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/446/2/022065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Zhang Y, Zhang S, Wang J, Hao G. Cooling effect analysis of suppressing coal spontaneous ignition with heat pipe. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2018;362:012022. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/362/1/012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang XF, Zhou XX. Experimental study on wall temperature and heat transfer characteristics of gravity heat pipe by heat input power and working materials. Combust Sci Technol. 2023;195(10):2311–26. doi:10.1080/00102202.2021.2015763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Ren WX, Liu X, Sun ZG, Guo Q. Internal heat extraction by gravity heat pipe for spontaneous combustion remediation. Combust Sci Technol. 2022;194(15):3175–87. doi:10.1080/00102202.2021.1915296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Wang Z, Zhang H, Yin L, Yang D, Yang G, Akkurt N, et al. Experimental study on heat transfer properties of gravity heat pipes in single/hybrid nanofluids and inclination angles. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2022;34:102064. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2022.102064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Yang S, Tao W. Heat transfer. 4th ed. Beijing, China: Higher Education Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools