Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effects of Wear-Induced Surface Roughness and Pore Taper on the Performance of Porous ZnS/Ag High-Temperature Solar Absorbers

1 Institute of Thermal Science and Technology, Shandong University, Jinan, 250061, China

2 Institute for Advanced Technology, Shandong University, Jinan, 250061, China

* Corresponding Authors: Haiyan Yu. Email: ; Mu Du. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Microscale Heat Transfer and Renewable Energy Utilization)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(5), 1495-1509. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.071263

Received 04 August 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 31 October 2025

Abstract

High-temperature radiative cooling is essential for solar absorbers, as it mitigates efficiency degradation resulting from thermal accumulation. While porous structures have proven effective in enhancing absorber performance, practical manufacturing processes and prolonged operational wear inevitably introduce surface roughness and structural deviations, which profoundly impact radiative properties. This study constructs a ZnS/Ag solar absorber model with surface roughness and employs the finite-difference time-domain method to investigate how characteristic length, surface roughness, porosity, pore shape factor, and taper influence its radiative properties in the 3 μm–5 μm band at 750 K. Results show optimal absorption at a 1 μm characteristic length with a 36.72% improvement compared to the model with l = 0.25 μm, increased absorption with higher porosity with a 69.29% improvement at 0.6 compared to the non-porous structure, lower circularity with a 19.03% improvement for C = 0.89 compared to C = 1.00, while surface roughness with a 61.24% improvement at RMS = 0.031 compared to RMS = 0 and taper with a 38.29% improvement at β = 20° compared to β = 0° also exert significant effects. This work provides engineering design guidelines for high-efficiency, low-cost absorbers.Keywords

Against the backdrop of the continuous growth in global energy demand and the increasing awareness of environmental protection, solar energy, as a clean and renewable energy source, has received widespread attention [1,2]. Among various solar energy utilization technologies, high-temperature solar absorbers play a core role in solar thermal power generation, thermophotovoltaic systems, and high-efficiency cooling systems [3,4]. Their main function is to efficiently absorb solar radiation and convert it into thermal energy or utilize it in other energy conversion processes. To achieve this goal, researchers are constantly exploring new materials and structures to improve the performance of absorbers [5,6].

Porous materials, with their high specific surface area and excellent optical properties, are key for enhancing solar absorber efficiency [7,8], especially ZnS/Ag porous nanomembranes, which exhibit superior radiative cooling performance at high temperatures due to their favorable optical characteristics and thermal stability [9]. However, long-term operation leads to pore structure wear, changes in pore size, and increased surface roughness, all of which significantly affect radiative properties and thus the long-term stability and efficiency of absorbers, making studies on the performance changes of such absorbers—particularly the impact of actual wear on their radiative properties—crucial for improving long-term working efficiency and advancing solar energy technology. Wu et al. [10] from Shandong Institute of Advanced Technology developed a broadband, wide-angle, polarization-insensitive solar absorber for the visible to near-infrared range, achieving ~98% average absorption in the 380–2000 nm band; it maintains high performance at large angles, has size tolerance, reduces manufacturing costs, and holds potential in solar capture and thermophotovoltaics. The optoelectronic team at Southwest University of Science and Technology proposed a three-layer Ti-SiO2 ring stack absorber [11], showing 98.03% average absorption in 280–4000 nm. He et al. [12] noted porous structures improve efficiency by uniformly distributing solar radiation across the absorber volume, while Tian et al. [13] fabricated Cu-rich plasmonic absorbers on aluminum alloys via solution-based leaching, with stable, scalable coatings. Lin et al. [14] discussed high-thermal-conductivity polymer composites for solar thermal storage, emphasizing nano-enhancers’ role. Liu et al. [15] highlighted key factors in radiative cooling, noting hybrid strategies boost performance. Guan et al. [16] designed transparent colored cooling films with dual color and cooling functions via optimized emitters. Pakdel and Wang [17] reviewed radiative cooling fibers, summarizing manufacturing methods. and Tsai et al. [18] developed superhydrophobic silica nanofibers with ~97% solar reflectance, 6°C sub-ambient cooling, and excellent durability, suitable for long-term use. None of these works incorporate the effects of wear-induced surface roughness or pore taper—factors explicitly modeled in our study to address the critical gap of operational wear in high-temperature solar absorber performance.

Although the design and optimization of high-temperature porous solar absorbers have progressed rapidly in recent years, most research has concentrated on improving optical properties and radiative cooling performance through structural design. However, in practical high-temperature applications, changes in surface roughness and pore geometry due to long-term wear can greatly affect the radiative performance and stability of these materials, which has not been fully addressed in previous studies.

This study investigates ZnS/Ag nanomembrane porous solar absorbers with a focus on the effects of surface roughness and pore taper caused by actual wear. Using the finite-difference time-domain method, we systematically analyze how structural parameters such as characteristic length, porosity, pore shape factor, surface roughness, and pore taper influence the reflectivity and absorptivity of the absorber in the second atmospheric window (3–5 μm) at 750 K. Special attention is given to the impact of wear-related changes in pore taper on wavelength-dependent radiative properties. The findings provide theoretical guidance for optimizing high-temperature solar absorber structures and improving their long-term efficiency and operational stability.

The finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method [19–21] is an efficient numerical technique for simulating electromagnetic field evolution by discretizing Maxwell’s equations in the time domain [22–24]. In this work, FDTD is used to investigate the microscale thermal radiation characteristics of the WHRA. The electromagnetic fields in vacuum are governed by Maxwell’s equations as [25]:

where B indicates the magnetic flux density, Wb/m2; D stands for the electric flux density while De is the electric displacement vector, C/m2; E presents the electric field, V/m; H is the magnetic field, A/m; J indicates the current density, A/m2; t is the time, s, ρ is the volume charge density, C/m3. To obtain the Maxwell equations in media instead of vacuum, the material equations are needed as [25]:

where ε indicates the permittivity, F/m; μ is permeability, H/m; σ indicates the conductivity, S/m. Bring Eqs. (2) into (1), the obtained Maxwell equations in media as Eq. (3) [25]:

In electromagnetic theory, the absorption cross section Q(a) describes the ratio of absorbed to incident energy [26]:

where (s) indicate the scattered electric and magnetic fields, respectively, (i) is incident electric and magnetic fields, respectively, * indicates the conjugate complex vector, (a) indicates the absorption rate,

where (r) presents the reflected and (t) indicates the transmitted. Then the magnetic fields in the transmission matrix are normalized by

where Zi is the wave impedance of the i-th layer medium. The transmission relation is then [27]:

For Fabry–Pérot resonance, destructive interference occurs when the phase difference of reflected waves is π, described by n∙d = (1 + 2x) λx/4 [27], where x is the positive integer, λx is the incident wave. Spectral irradiance F (λ), commonly used in solar cell analysis, is [27]:

where h indicates the Planck’s constant, c presents the speed of light, k is the Boltzmann’s constant.

To quantitatively assess the capability of the absorber to harvest and utilize solar energy, the solar absorption efficiency A and solar enhancement efficiency η are calculated as [27].

η indicates the solar enhancement efficiency; Ap is the solar absorptivity of the flat plate. The Eqs. (5) and (10) would use to calculate the absorption, reflection solar energy effectively in the following calculation.

3.1 Physical Model of High-Temperature Radiative Cooling Solar Absorber

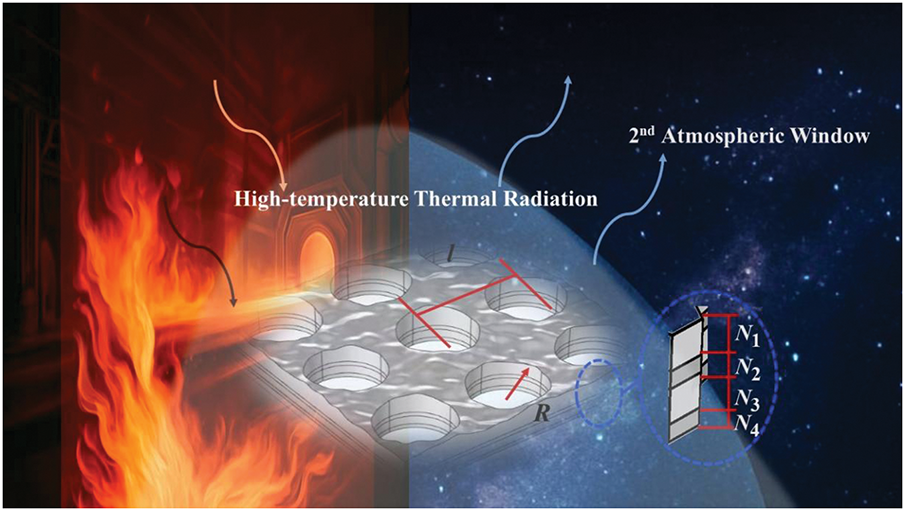

In this work, a wear-influenced high-temperature radiative cooling solar absorber (hereinafter referred to as WHRA) is proposed. The absorber employs a ZnS-Ag-ZnS-Ag nanomembrane substrate featuring micropore arrays, with explicit consideration of surface roughness induced by wear, shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of high-temperature radiative cooling solar absorber

As shown in Fig. 1, the radius of the bottom surface of the cylindrical pore is R, while the characteristic length can be represented by the distance l between the centers of adjacent cylindrical pores, and additionally, the porosity can be defined by φ = πR2/l2.

At a high temperature of 750 K, the designed multilayers achieve over 99% reflectivity in the second atmospheric window (mid-infrared atmospheric window, MIAW, approximately 3–5 μm), which has high atmospheric transmittance. The thicknesses of the multilayers perpendicular to the incident direction are N1, N2, N3, and N4. In this work, the thicknesses of the multilayers are N1=174.43, N2=348.86, N3=523.2, and N4=697.72 nm, respectively. To ensure the accuracy of numerical calculations, the following parameter settings are adopted for the thermal radiation integration process. The wavelength range is set to 0.4 to 6 μm, the incident angles are discretized into 20,000-unit angles from 0° to 90°, and the frequency resolution is set to 2 × 10¹² Hz. This refined discretization scheme can effectively support the requirements of high-precision radiation transfer calculations.

In this study, high-reflectivity Silver was selected as the reflection layers, N2 and N4 without considering the oxidation condition, with its refractive index and extinction index, while low-emissivity Zinc sulfide was chosen as the absorption layers, with the refractive index and extinction index of N1 and N3. In consideration of the effect of continuity in the simulation on n and k, the Bessel spline function was applied to this curve. The n and k for Ag were extracted from experimental data reported by Yang et al. [28], while those for ZnS were obtained from Querry [29]; these discrete data points, spanning specific wavelength ranges, were then interpolated using a Bessel spline function to generate continuous n and k curves across the 3–5 μm wavelength band analyzed in this study, ensuring smooth and accurate optical property inputs for the FDTD simulations.

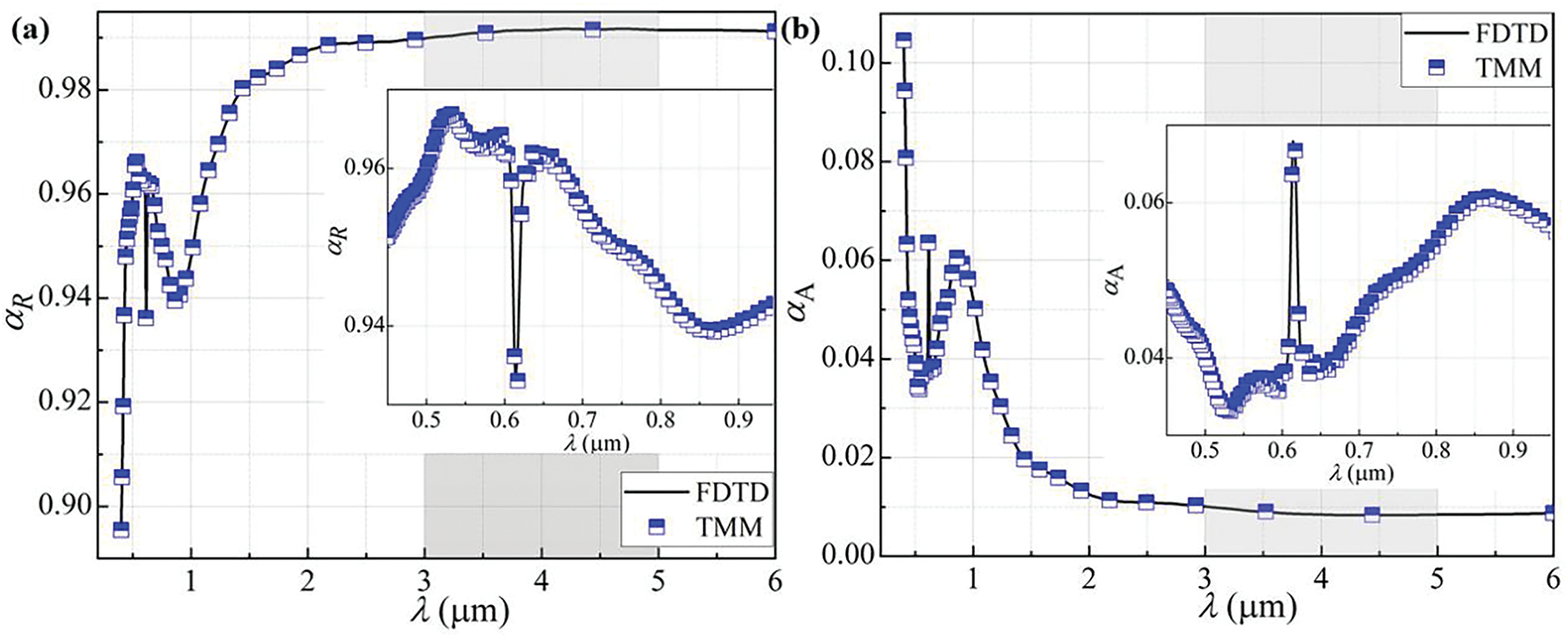

To verify the accuracy of the numerical simulation method, the reflectivity αR and absorptivity αA of the WHRC with R = 0, the ZnS-Ag-ZnS-Ag multilayer structure, were calculated using the TMM and FDTD methods respectively, and the results are plotted in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: The thermal radiative properties of WHRC calculated by FDTD and TMM methods: (a) Reflectivity; (b) Absorptivity

As shown in Fig. 2, the results of the αR and αA calculated by the FDTD method are almost consistent with those given by the TMM, with an error within 1.7%, especially at mid-infrared wavelengths. Since the TMM is almost an exact analytical solution, the calculation results of the FDTD method are considered accurate in the calculation of the WHRC in this study, with errors within acceptable limits. Therefore, the following calculations of the thermal radiative properties of the WHRC are all carried out using the FDTD method.

As can be seen from Fig. 2, in the wavelength range from 3.0 to 5.0 μm, αR >0.99 while αA <0.01. The WHRC with R = 0 exhibits good cooling radiation performance under the high-temperature condition of 750 K.

To qualitatively determine the influence of geometric structures and incident conditions on the radiative properties of the HRC solar absorber, based on the FDTD method, we discuss the effects of the following factors on the absorptivity (αA) and reflectivity (αR) of the solar absorber, including characteristic length (l = 0.25–1.25 μm), porosity (φ = 0–0.7), pore shape factor (C = 0.89–1.00), surface roughness (RMS = 0–0.031), and taper (β = 0°–20°).

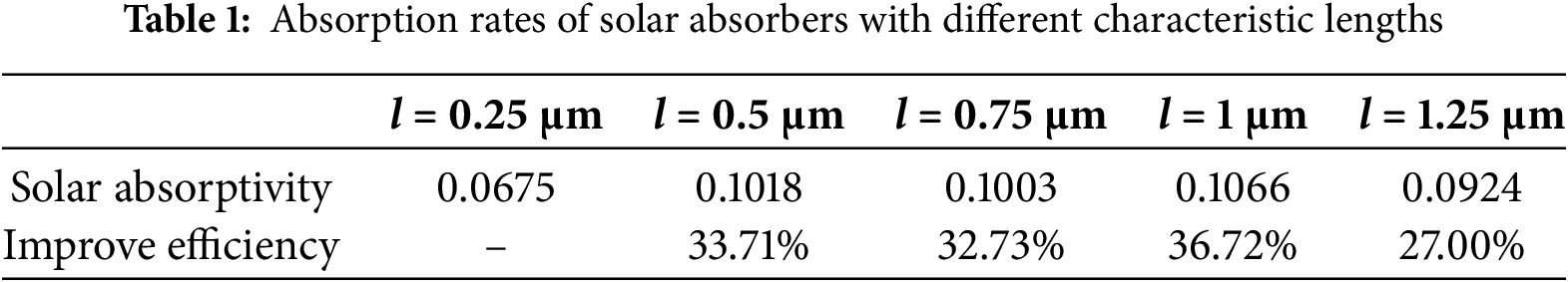

4.1 The Effect of Characteristic Length

To investigate the influence of characteristic length on the reflection and absorption properties of solar absorbers, this study constructed five HRC models with different characteristic lengths (l = 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, 1, 1.25 μm) for comparative analysis. In the experiment, parameters such as bottom circularity C = 1.00, porosity φ = 0.2, incident angle θ = 90°, surface roughness RMS = 0.007, and taper β = 0° were kept constant. The calculation results are detailed in Table 1 and Fig. 3.

Figure 3: The thermal radiative properties of WHRC solar absorbers with different characteristic lengths: (a) Reflectivity; (b) Absorptivity

The data indicate that the solar absorptivity of all models with varying characteristic lengths is enhanced by over 27% in comparison to the traditional flat-plate structure. Among these, the model with l = 1 μm exhibits the optimal performance, achieving an absorptivity of 0.1066 with an efficiency improvement of 36.72%. The results show that as the characteristic length increases from 0.25 to 1 μm, solar absorptivity presents an overall upward trend with a slight fluctuation at 0.75 μm. When the characteristic length exceeds 1 μm—specifically at 1.25 μm—solar absorptivity decreases. In terms of improvement efficiency relative to the l = 0.25 μm model, the l = 1 μm model achieves the highest improvement efficiency at 36.72%, followed by the l = 0.5 μm model at 33.71%, the l = 0.75 μm model at 32.73%, and finally the l = 1.25 μm model at 27.00%. Considering both solar absorptivity and improvement efficiency, the optimal characteristic length is around 1 μm, where solar absorption performance peaks.

Through in-depth analysis of Fig. 3a,b, a significant influence of the characteristic length l on the reflectivity αR and absorptivity αA can be observed: as l increases, the reflectivity αR shows a decreasing trend in the MIAW (the specific wavelength band of λ = 3–5 μm), while the absorptivity αA exhibits an increasing trend in the same region. Specific data indicate that when the characteristic length l is 0.25 μm, 25% of the wavelength bands in the MIAW have a reflectivity αR exceeding 0.99; when l < 1 μm, all wavelength bands reach αR > 0.95, whereas increasing l to 1.25 μm, this proportion decreases significantly to 91.67%. Meanwhile, for the absorptivity αA, when l = 0.25 μm, 83.3% of the wavelength bands in the MIAW have an absorptivity αA lower than 0.01; when l = 1.25 μm, this proportion also drops to 25%. Further analysis reveals that when l does not exceed 0.75 μm, all wavelength bands in the MIAW can meet the criteria of reflectivity αR > 0.95 and absorptivity αA < 0.02, and this performance basically conforms to the technical requirements for cooling radiation in a high-temperature environment of 750 K.

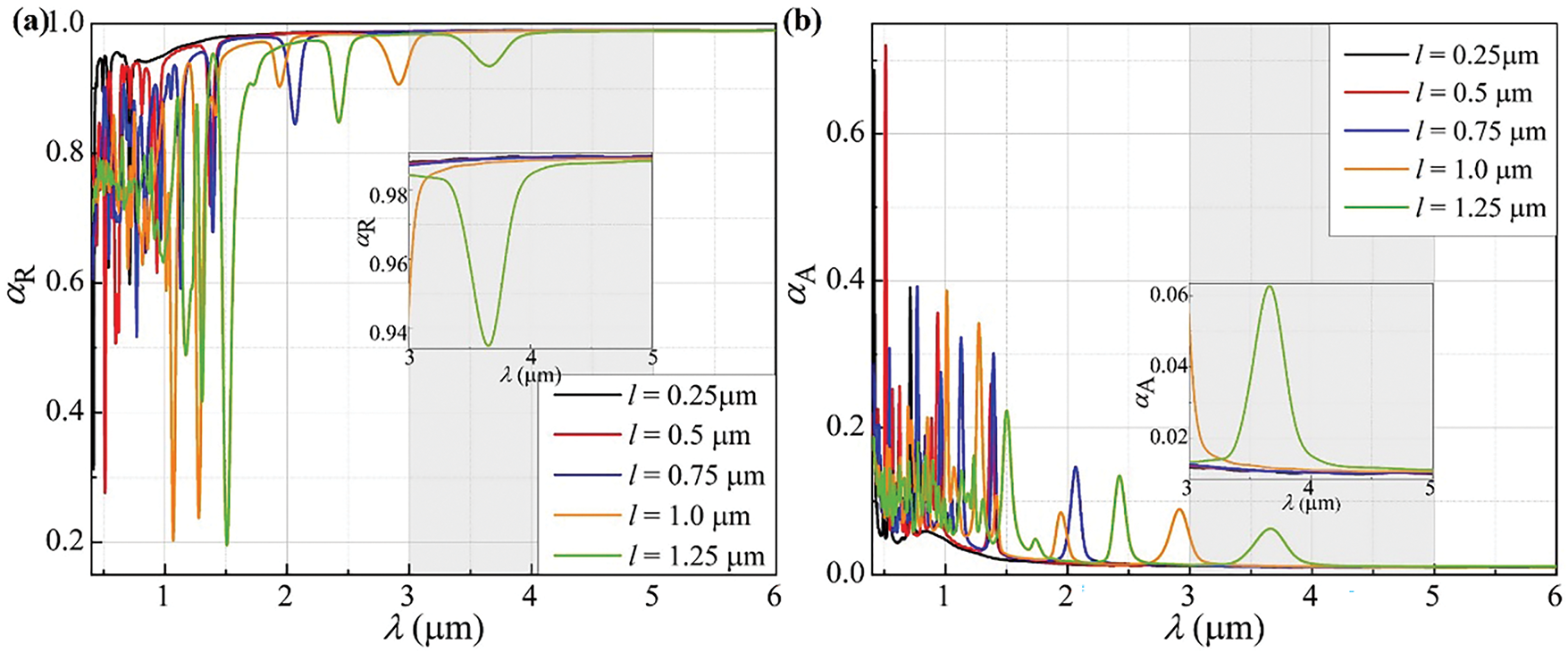

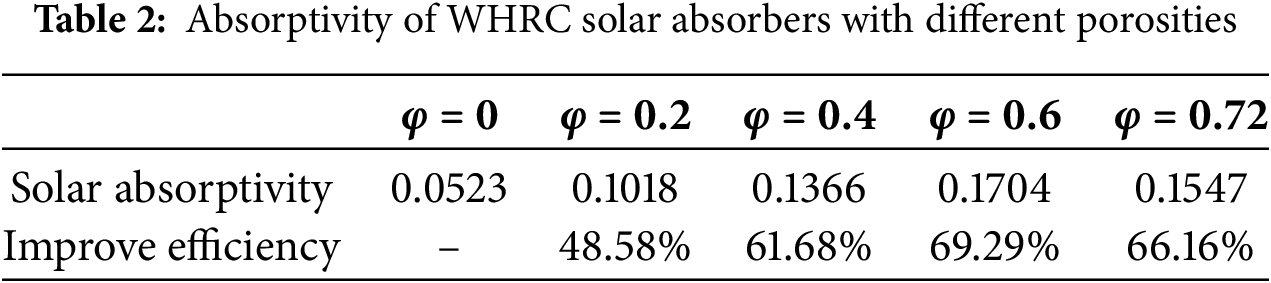

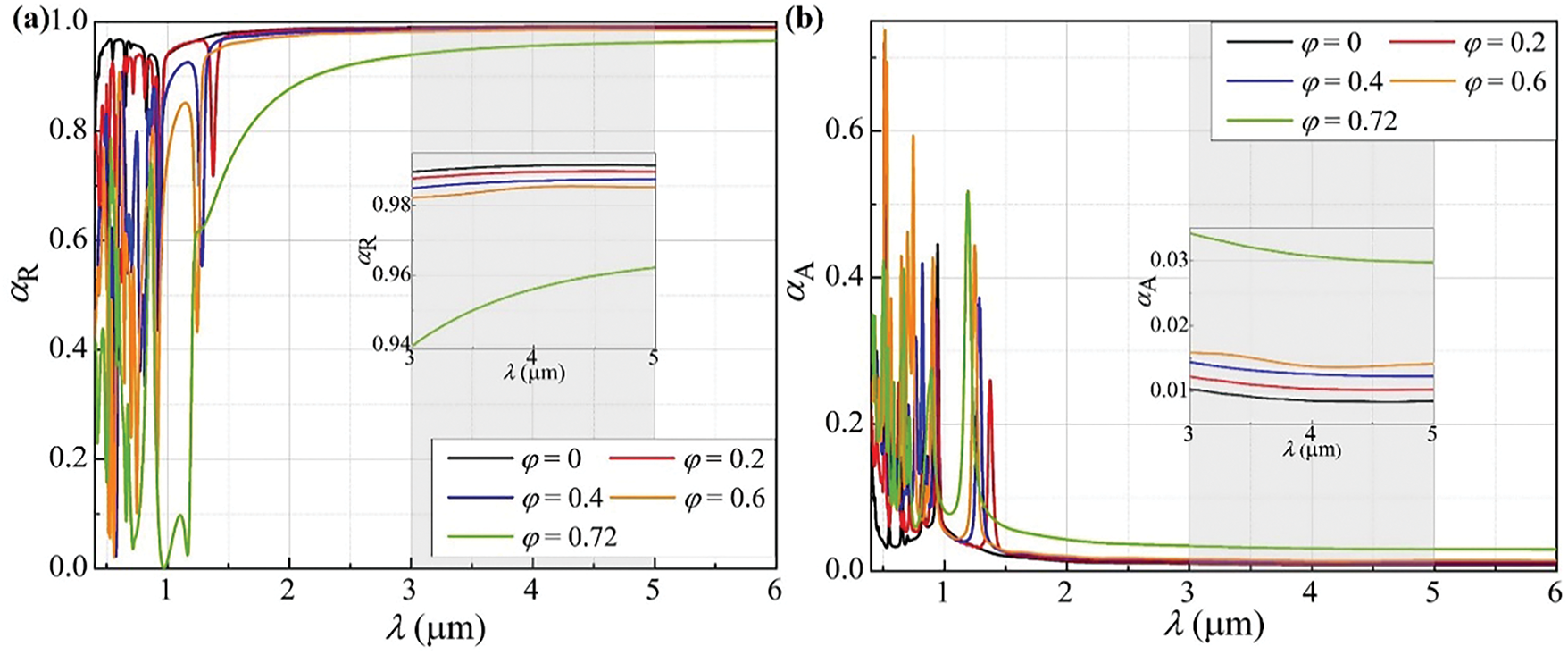

To investigate the influence of porosity φ on the spectral performance of HRC solar absorbers, this section establishes six sets of models with different porosity parameters (φ = 0, 0.2, 0.4, 0.6, 0.72). In the experiments, structural parameters including bottom circularity C = 1.00, characteristic length l = 0.5 μm, incident angle θ = 90°, surface roughness RMS = 0.007, and taper β = 0° are strictly kept constant. The calculation results are detailed in Table 2 and the spectral characteristic curves presented in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The thermal radiative properties of WHRC solar absorbers with different porosities: (a) Reflectivity; (b) Absorptivity

According to the data in Table 2, the spectral absorption performance of all models is significantly enhanced compared to the traditional flat-plate structure, with the improvement rate exceeding 48.58%. Among them, the model with φ = 0.6 demonstrates the optimal absorption performance, achieving an absorptivity of 0.1704, which is an 69.29% improvement compared to the benchmark structure. It is followed by the model with φ = 0.72, which has an absorptivity of 0.1547 and an efficiency improvement of 66.16%. The model with φ = 0 (non-porous structure) exhibits the lowest absorptivity of only 0.0523. The data analysis results indicate that under the condition of keeping other structural parameters constant, the solar absorptivity of the WHRC absorber is positively correlated with porosity. As the porosity increases from 0 to 0.6, the light-trapping capability is significantly enhanced, reaching the performance peak at φ = 0.6. With this parameter combination, the absorber can meet the spectral selectivity requirements of αR > 0.98 and αA < 0.02 within the operating temperature range around 750 K, providing a basis for the optimized porous structure design in high-temperature thermophotovoltaic applications.

Analysis of the spectral characteristics in Fig. 4 can reveal the regulatory mechanism of porosity φ on optical properties: with the increase of porosity φ, the reflectivity αR shows a continuous decreasing trend in the MIAW band, while the absorptivity αA increases synchronously. This phenomenon of reciprocal growth and decline stems from the essential influence of porous structure parameters on photon trapping capability—when φ increases, the equivalent specific surface area of the material increases significantly, leading to enhanced multiple scattering effects of photons in the pore network, which macroscopically manifests as an increase in αA and a decrease in αR.

This porosity-dependent spectral regulation characteristic provides a clear optimization direction for the porous structure design of high-temperature thermophotovoltaic devices: under the premise of ensuring structural mechanical stability, appropriately increasing the porosity can significantly enhance the light absorption capability, but attention should be paid to avoiding the degradation of spectral selectivity caused by excessive porosity.

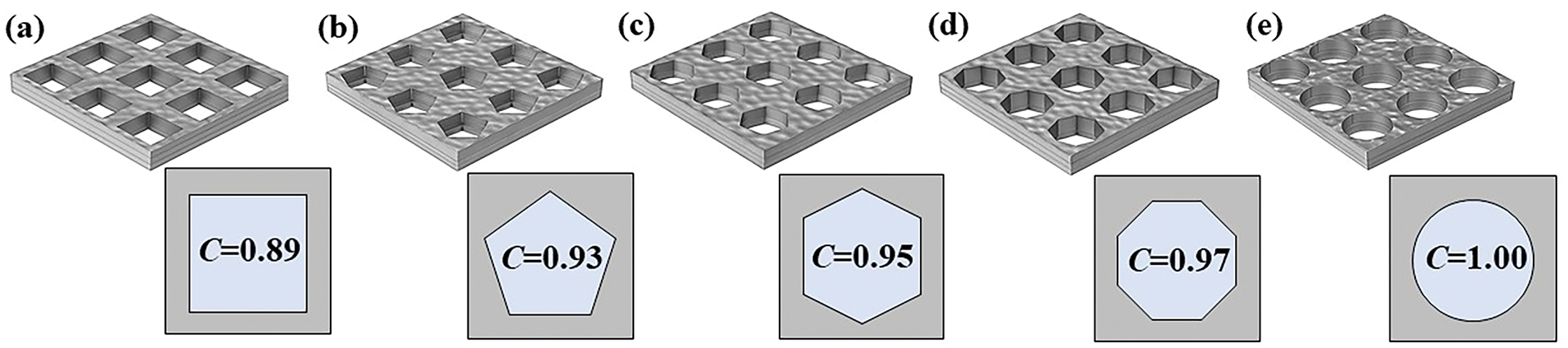

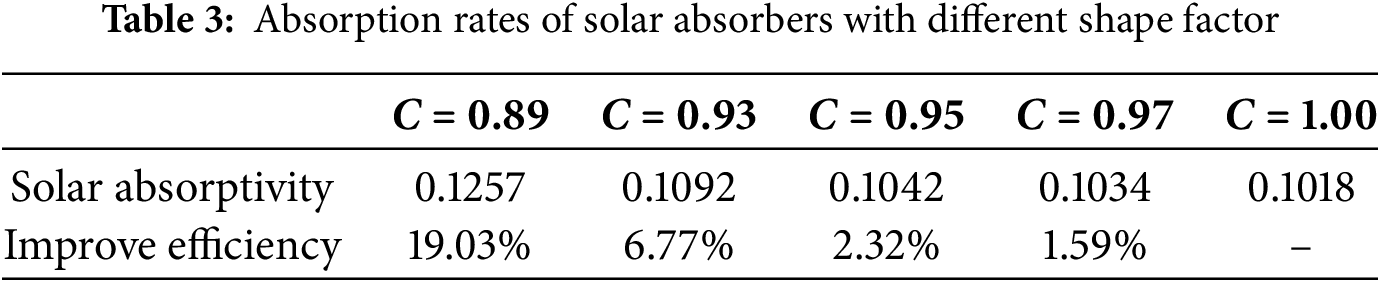

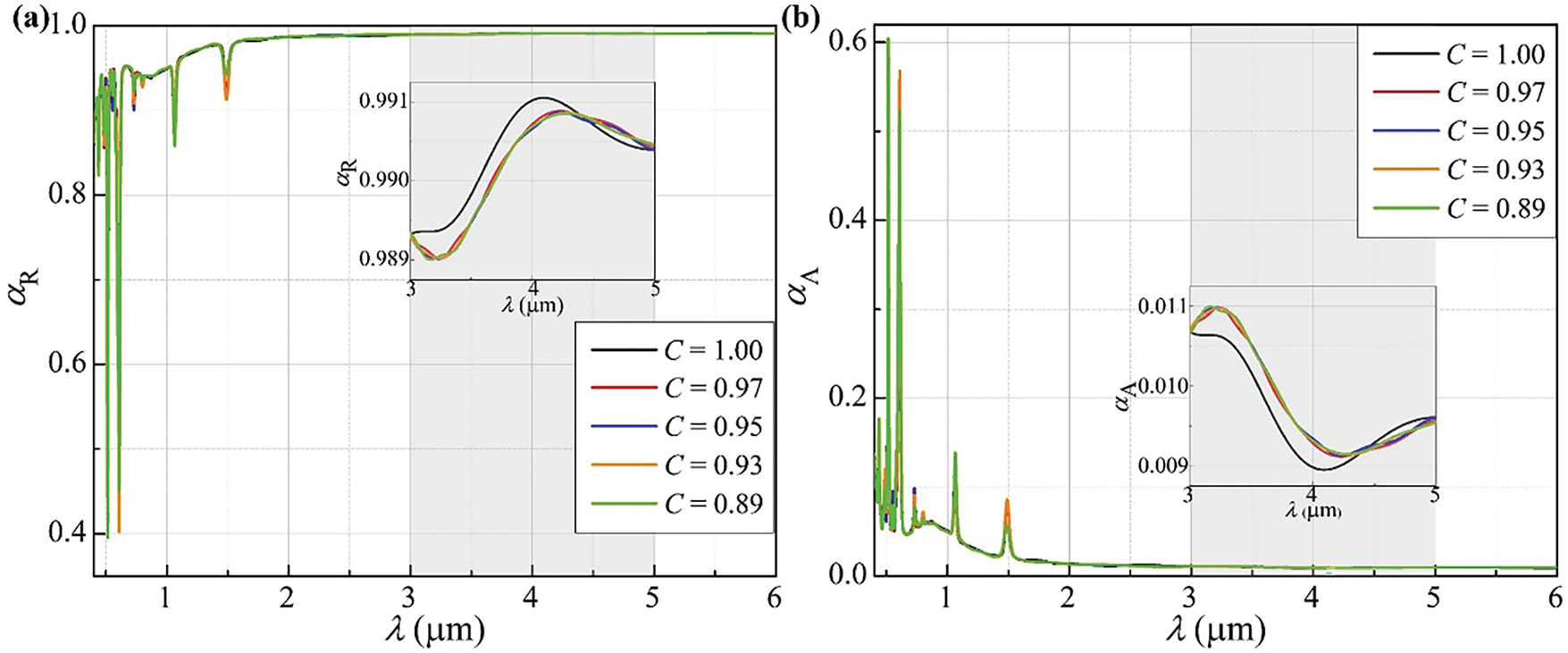

4.3 The Effect of Shape Factor

Circularity (C) as a shape factor to characterize geometric shapes according to ISO9276-6 [30], was described as C = (4πS/P) − 2, where S is the internal specific surface area, P represents the pore projected perimeter, measured by the software during image analyses [31]. To systematically investigate the influence mechanism of pore morphology on spectral radiation properties, this study constructs five pore models with typical cross-sectional shapes (as shown in Fig. 5), with their circularity parameters being C = 0.89 (quadrilateral), C = 0.93 (pentagon), C = 0.95 (hexagon), C = 0.97 (octagon), and C = 1.00 (circle), respectively. To ensure the singularity of experimental variables, all models adopt the design principle of equivalent circumscribed circle radius: when the circularity C increases from 0.89 to 1.00, the corresponding circumscribed circle radii are 111.80, 102.54, 98.09, 94.01, and 89.21 nm, respectively. This design strategy ensures that the internal surface areas of pores with different morphologies are consistent, thereby decoupling the morphological effect from other structural parameters. In the experiments, key parameters such as characteristic length l = 0.5 μm, porosity φ = 0.2, incident angle θ = 90°, surface roughness RMS = 0.007, and taper β = 0° are strictly kept constant. The calculation results are detailed in Table 3 and Fig. 6. This indicates the influence of pore morphology on thermal radiation properties: as the pore shape evolves from polygon to circle (with C approaching 1), the scattering paths of photons at the pore boundaries change regularly. This morphology modulation effect provides a new design idea for optimizing the spectral selectivity of high-temperature solar absorbers.

Figure 5: The schematic diagrams of models with different shape factors: (a) C = 0.89; (b) C = 0.93; (c) C = 0.95; (d) C = 0.97; and (e) C = 0.97

Figure 6: The thermal radiation properties of WHRC solar absorbers with different shape factors: (a) Reflectivity; (b) Absorptivity

According to the quantitative analysis in Table 3, the solar absorptivity of all five geometric configuration absorbers is significantly enhanced compared to the traditional flat structure. According to the quantitative analysis of the data, the solar absorptivity of the four geometric configuration absorbers with C values of 0.89, 0.93, 0.95 and 0.97 is enhanced compared to the configuration with C = 1.00. The configuration with C = 0.89 performs best with an absorptivity of 0.1257 and an improvement efficiency of 19.03%, followed by the one with C = 0.93 which has an absorptivity of 0.1092 and an improvement efficiency of 6.77%. Next is the configuration with C = 0.95 showing an absorptivity of 0.1042 and an improvement efficiency of 2.32%, and then the one with C = 0.97 presenting an absorptivity of 0.1034 and an improvement efficiency of 1.59%. The configuration with C = 1.00 has the lowest absorptivity of 0.1018 with no improvement efficiency relative to the others. Statistics indicate that the influence of the inner pore shape factor C on absorption performance is notable as absorptivity decreases with the increase of C.

Fig. 6 reveals the effect of circularity C on photon regulation: αR slightly increases while αA in MIAW decreases with higher C. At C ≥ 0.97, 66.7% of bands meet αR ≥ 0.99 and αA < 0.01; at C ≤ 0.95, this drops to 50%. Notably, all bands in 0.89 ≤ C ≤ 1.00 satisfy αR > 0.98 and αA < 0.02, meeting high-temperature radiation control needs around 750 K. At λ = 4 μm, the perfect circle (C = 1.00) shows a 15%–20% stronger reflectivity peak, guiding specific-band optical device design.

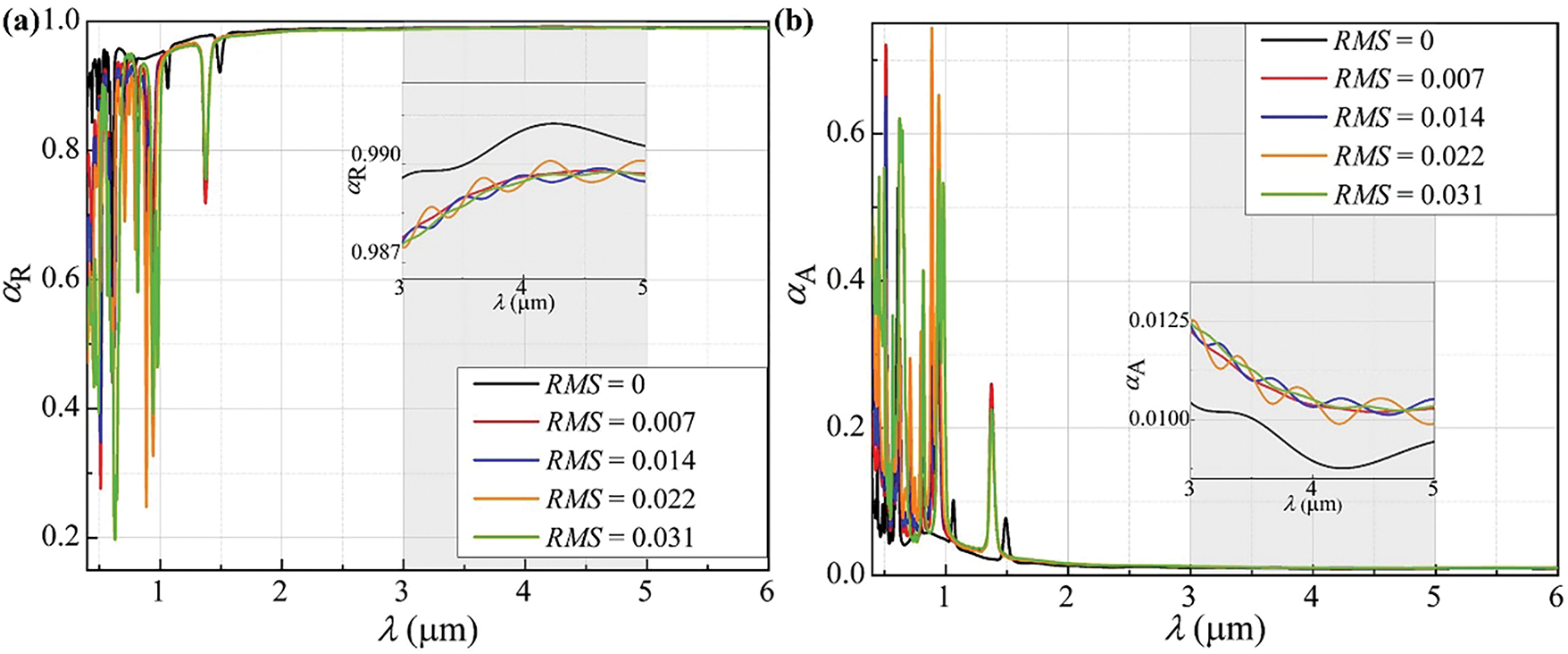

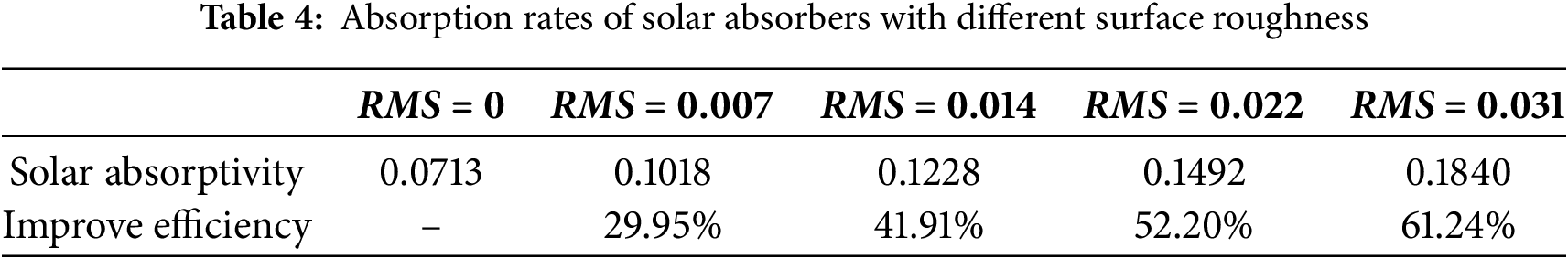

4.4 The Effect of Surface Roughness

To investigate the influence of surface roughness RMS on the spectral performance of HRC solar absorbers, this section constructs five sets of models with different surface roughness parameters (RMS = 0, 0.007, 0.014, 0.022, 0.031). In the experiments, parameters including bottom circularity C = 1.00, characteristic length l = 0.5 μm, porosity φ = 0.2, and taper β = 0° are strictly kept constant. The calculation results are detailed in the spectral characteristic curves shown in Fig. 7.

Figure 7: The thermal radiation properties of WHRC solar absorbers with different surface roughness RMS: (a) Reflectivity; (b) Absorptivity

According to the quantitative analysis in Table 4, the solar absorptivity of the four geometric configuration absorbers with RMS values of 0.007, 0.014, 0.022 and 0.031 is significantly enhanced compared to the configuration with RMS = 0. The configuration with RMS = 0.031 performs best with an absorptivity of 0.1840 and an improvement efficiency of 61.24%, followed by the one with RMS = 0.022 which has an absorptivity of 0.1492 and an improvement efficiency of 52.20%. Next is the configuration with RMS = 0.014 showing an absorptivity of 0.1228 and an improvement efficiency of 41.91%, and then the one with RMS = 0.007 presenting an absorptivity of 0.1018 and an improvement efficiency of 29.95%. The configuration with RMS = 0 has the lowest absorptivity of 0.0713 with no improvement efficiency relative to the others. Statistics indicate that the influence of the RMS on absorption performance is notable as absorptivity increases with the increase of RMS.

Fig. 7a depicts the variation trend of reflectivity αR of HRC solar absorbers with wavelength under different RMS values. When the surface roughness is low, the reflectivity curve is relatively flat, indicating that the reflectivity changes uniformly with wavelength. As the surface roughness increases, the reflectivity curve begins to show obvious fluctuations. These fluctuations indicate that the rough surface makes the reflection behavior of light at different wavelengths more complex, and the reflectivity presents undulating characteristics with wavelength changes. Within specific wavelength ranges, the differences in reflectivity corresponding to different RMS values are particularly significant, implying that the influence of surface roughness on material reflectivity has wavelength selectivity.

Fig. 7b shows the variation of absorptivity αA of HRC solar absorbers with wavelength under different RMS values. Similar to reflectivity, the absorptivity curve is relatively flat at low roughness. With the increase of RMS values, the absorptivity curve also changes, with the most significant feature being the emergence of absorptivity peaks. These peaks indicate that the rough surface significantly enhances the absorptivity of the material at specific wavelengths. The positions and heights of the peaks in the absorptivity curves corresponding to different RMS values are distinct, which suggests that surface roughness not only affects the magnitude of absorptivity but also influences the wavelength characteristics of material absorptivity.

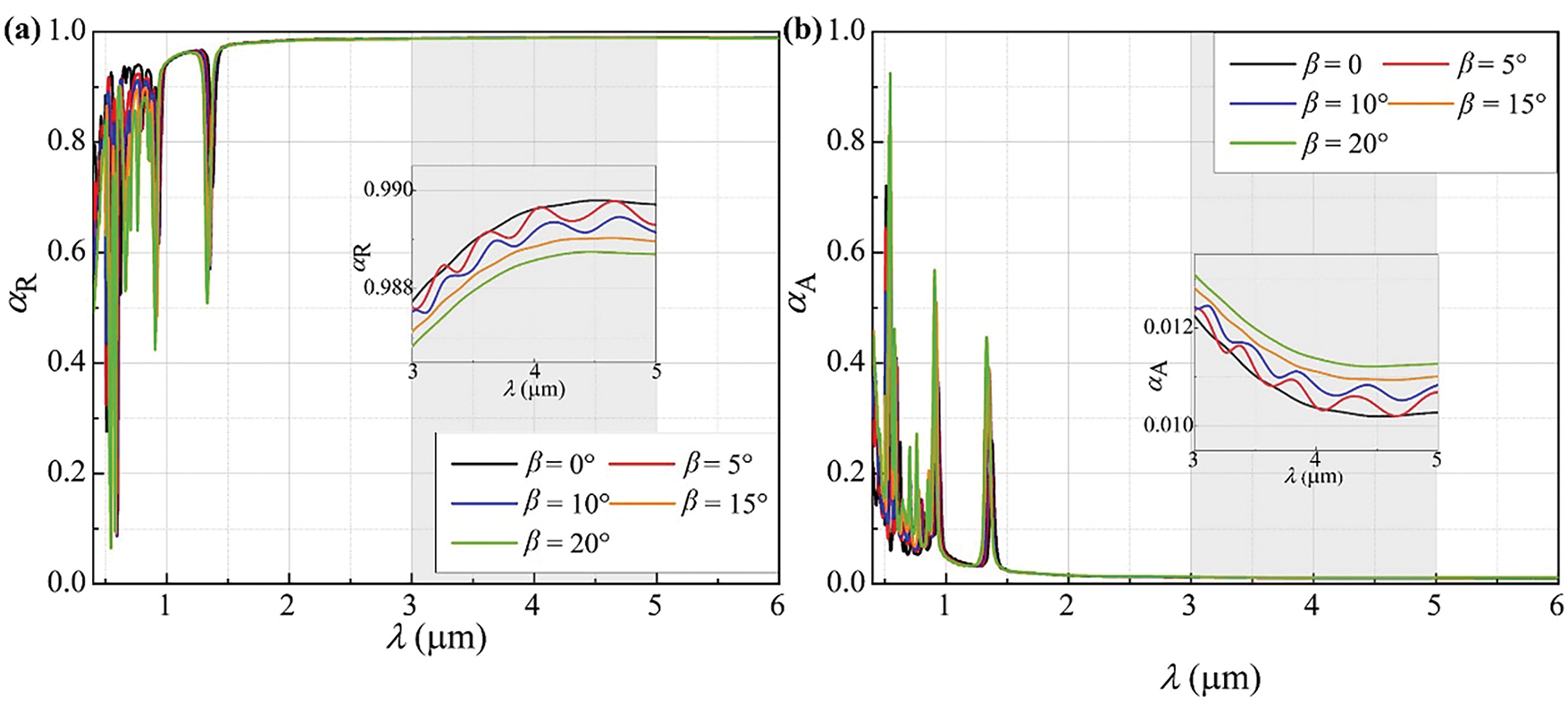

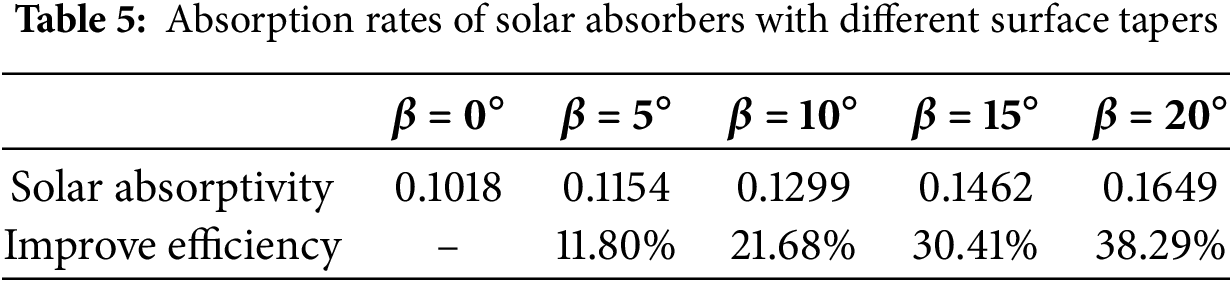

This paper constructs five sets of models with different taper parameters (β = 0°, 5°, 10°, 15°, 20°). In the experiments, structural parameters such as bottom circularity C = 1.00, characteristic length l = 0.5 μm, incident angle θ = 90°, porosity φ = 0.2, and surface roughness RMS = 0.007 are strictly kept constant. Fig. 8 mainly shows the influence of different taper angles β on the reflectivity αR and absorptivity αA of the solar absorber. Due to the wear of the solar absorber during actual use, including surface wear and internal pore wear, the pore diameter increases from bottom to top. The taper β is a parameter characterizing the wear degree, and there is a positive correlation between them. The calculation formula of taper β is

Figure 8: The thermal radiation properties of WHRC solar absorbers with different surface tapers β: (a) Reflectivity; (b) Absorptivity

According to the quantitative analysis in Table 5, the solar absorptivity of the four geometric configuration absorbers with β values of 5°, 10°, 15° and 20° is significantly enhanced compared to the configuration with β = 0°. The configuration with β = 20° performs best with an absorptivity of 0.1649 and an improvement efficiency of 38.29%, followed by the one with β = 15° which has an absorptivity of 0.1462 and an improvement efficiency of 30.41%. Next is the configuration with β = 10° showing an absorptivity of 0.1299 and an improvement efficiency of 21.68%, and then the one with β = 5° presenting an absorptivity of 0.1154 and an improvement efficiency of 11.80%. The configuration with β = 0° has the lowest absorptivity of 0.1018 with no improvement efficiency relative to the others. Statistics indicate that the influence of β on absorption performance is notable as absorptivity increases with the increase of β.

Fig. 8 clearly shows that with the increase of the taper angle, the peak position and height of αR change significantly, indicating that the taper angle is an important factor affecting reflectivity. In addition, the reflectivity has a strong dependence on wavelength. Under different taper angles, the variation trends of reflectivity with wavelength show significant differences, which suggests that the taper angle not only affects the magnitude of reflectivity but also influences the law of reflectivity variation with wavelength.

As the taper angle increases, the fluctuation of αA at specific wavelengths increases significantly. Such fluctuations indicate that changes in taper have a significant impact on the absorption properties of the film, which may lead to an increase or decrease in absorptivity, depending on the wavelength and taper angle. Similar to reflectivity, the changes in absorptivity also exhibit wavelength selectivity. At certain specific wavelengths, the changes in absorptivity are more significant, implying that the taper angle has a stronger modulation effect on light absorption at these wavelengths.

In this work, considering the wear or process defects existing in practical applications or processing, a ZnS/Ag porous nanomembrane solar absorber with surface roughness and pore taper angle was constructed. Based on the finite difference time domain method, the effects of five key parameters, i.e., characteristic length, porosity, pore shape factor, surface roughness, and pore taper on solar energy absorption capability and high-temperature radiative cooling performance are comprehensively discussed. The main conclusions are as follows:

(1) Introducing surface roughness with an RMS of 0.031 μm increases the average absorptivity in the 3–5 μm band by up to 61.24% compared to the configuration with RMS = 0, and causes pronounced irregular fluctuations in reflectivity, thereby significantly enhancing the wavelength selectivity and absorption performance of the absorber.

(2) Increasing the pore taper angle from 0° to 20° results in an approximate 38.29% increase in average absorptivity within the same wavelength range, and intensifies the wavelength dependence of both absorptivity and reflectivity, leading to more variable radiative performance.

(3) In the presence of surface roughness, the optimal characteristic length for maximum absorption is 1 μm, and at a porosity of 0.6, the absorptivity increases by 69.29% compared to the non-porous structure (φ = 0), while at a porosity of 0.72, the absorptivity is 0.1547 with an improvement efficiency of 66.16% compared to φ = 0. The influence of characteristic length and porosity on absorption efficiency is more significant than in ideal, defect-free structures.

(4) The optimal parameters guide manufacturing by balancing performance and feasibility. Surface roughness of 0.031 μm enhances absorptivity by 61.24% compared to RMS = 0 but requires precise fabrication to avoid uniformity issues. Taper angles ≤10° improve absorptivity by 21.68% relative to β = 0° while supporting stability, whereas higher angles (up to 20°) with a 38.29% absorptivity improvement risk thermal stress, demanding trade-offs in wear resilience. Porosity of 0.6 maximizes efficiency with a 69.29% absorptivity increase compared to the non-porous structure (φ = 0), yet even at 0.72 with a 66.16% improvement, uniform pore control is needed to prevent structural fragility.

(5) The study’s idealized pore distribution may not match real-world variations in size and spacing. Focus on 750 K limits insights into higher temperatures where material stability could decline. Fixed material properties overlook thermally induced optical changes that affect long-term performance. Dynamic wear processes like time-dependent taper evolution are not included, leaving room for deeper operational analysis.

In summary, to ensure stable and efficient operation of porous high-temperature solar absorbers in practical applications, it is essential to control fabrication precision and select structural parameters that account for surface wear and pore geometry variations.

Acknowledgement: Sincere gratitude is extended to Shandong University for providing an excellent academic and research environment that has significantly facilitated the completion of this work. The university’s well-equipped facilities, supportive academic atmosphere, and dedication to fostering research innovation have been invaluable throughout the entire research process.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 52406102, received by Haiyan Yu; and by Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation, grant number ZR2023QE258, received by Haiyan Yu. The URLs to the sponsors’ websites are: https://www.nsfc.gov.cn/ (National Natural Science Foundation of China) and http://kjt.shandong.gov.cn/index.html (accessed on 01 August 2025) (Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Haiyan Yu, Mingdong Li; data collection: Haiyan Yu, Mingdong Li, Ning Guo; analysis and interpretation of results: Haiyan Yu, Mingdong Li, Fengying Ren, Yongheng Lu; draft manuscript preparation: Haiyan Yu, Mingdong Li, Mu Du; critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Ning Guo, Fengying Ren, Yongheng Lu, Mu Du. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang T, Liu W, Kramer GJ, Sun Q. Seasonal thermal energy storage: a techno-economic literature review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2021;139(6):110732. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2021.110732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Wang W, Yuan B, Sun Q, Ronald W. Analysis and modeling of calendar aging and cycle aging of LiCoO2/graphite cells. J Therm Sci. 2024;33(3):1109–18. doi:10.1007/s11630-024-1918-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhou L, Yang W, Li C, Lin S. Numerical investigation on thermal performance of two-phase immersion cooling method for high-power electronics. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(1):157–73. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2023.045135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Navalho JEP, Silva LGG, Pereira JCF. An investigation on the thermal performance of volumetric solar absorbers with lateral wall power losses. Sol Energy. 2024;282(6):112937. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2024.112937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. AbdelFatah RT, Fahim IS, Kasem MM. Investigative review of design techniques of parabolic trough solar collectors. Front Heat Mass Transf. 2024;22(1):317–39. doi:10.32604/fhmt.2023.044706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhao P, Dong M, Liu X, Wang YF, Wang WM, Liu BH, et al. Ultrahigh thermal robustness of high-entropy spectrally selective absorbers for next-generation concentrated solar power system. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(52):2411316. doi:10.1002/adfm.202411316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Chen A, Chai J, Ren X, Li M, Yu H, Wang G. A novel prediction model for thermal conductivity of open microporous metal foam based on resonance enhancement mechanisms. Energies. 2025;18(6):1529. doi:10.3390/en18061529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Abdel-Aziz MM, ElBahloul AA. Innovations in improving photovoltaic efficiency: a review of performance enhancement techniques. Energy Convers Manag. 2025;327(2):119589. doi:10.1016/j.enconman.2025.119589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Yu H, Zhang H, Dai Z, Xia X. Design and analysis of low emissivity radiative cooling multilayer films based on effective medium theory. ES Energy Environ. 2019;6(2):69–77. doi:10.30919/esee8c333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wu J, Sun Y, Wu B, Sun C, Wu X. Broadband and wide-angle solar absorber for the visible and near-infrared frequencies. Sol Energy. 2022;238(1):78–83. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2022.04.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Sun C, Liu H, Yang B, Zhang K, Zhang B, Wu X. An ultra-broadband and wide-angle absorber based on a TiN metamaterial for solar harvesting. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2022;25(1):806–12. doi:10.1039/d2cp04976g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. He YL, Du S, Shen S. Advances in porous volumetric solar receivers and enhancement of volumetric absorption. Energy Rev. 2023;2(3):100035. doi:10.1016/j.enrev.2023.100035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Tian Y, Liu X, Caratenuto A, Li J, Zhou S, Ran R, et al. A new strategy towards spectral selectivity: selective leaching alloy to achieve selective plasmonic solar absorption and infrared suppression. Nano Energy. 2022;92(10):106717. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2021.106717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lin Y, Li P, Liu W, Chen J, Liu X, Jiang P, et al. Application-driven high-thermal-conductivity polymer nanocomposites. ACS Nano. 2024;18(5):3851–70. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c08467. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Liu J, Zhang Y, Li S, Valenzuela C, Shi S, Jiang C, et al. Emerging materials and engineering strategies for performance advance of radiative sky cooling technology. Chem Eng J. 2023;453(2):139739. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.139739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Guan Q, Raza A, Mao SS, Vega LF, Zhang T. Machine learning-enabled inverse design of radiative cooling film with on-demand transmissive color. ACS Photonics. 2023;10(3):715–26. doi:10.1021/acsphotonics.2c01857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Pakdel E, Wang X. Thermoregulating textiles and fibrous materials for passive radiative cooling functionality. Mater Des. 2023;231(6518):112006. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Tsai MT, Chang SW, Chen YJ, Chen HL, Lan PH, Chen DC, et al. Scalable, flame-resistant, superhydrophobic ceramic metafibers for sustainable all-day radiative cooling. Nano Today. 2023;48:101745. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2022.101745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Inan US, Marshall RA. Numerical electromagnetics: the FDTD method. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

20. Hao Y, Mittra R. FDTD modeling of metamaterials: theory and applications. Norwood, MA, USA: Artech House; 2011. [Google Scholar]

21. Sullivan DM. Electromagnetic simulation using the FDTD method. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013. [Google Scholar]

22. Gedney S. Introduction to the finite-difference time-domain (FDTD) method for electromagnetics. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2022. [Google Scholar]

23. Liu B, Xia XL, Chen X, Ma M. Integrated-scale prediction of radiative properties of open-cell metal foam based on the pore-scale transfer and microscopic morphology of ligaments. Int J Therm Sci. 2021;163(9):106750. doi:10.1016/j.ijthermalsci.2020.106750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Yu H, Zhang H, Buahom P, Liu J, Xia X, Park CB. Prediction of thermal conductivity of micro/nano porous dielectric materials: theoretical model and impact factors. Energy. 2021;233(1):121140. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2021.121140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ball JM, Li W. Using high-resolution microscopy data to generate realistic structures for electromagnetic FDTD simulations from complex biological models. Nat Protoc. 2024;19(5):1348–80. doi:10.1038/s41596-023-00947-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Yu H, Zhang H, Wang H, Zhang D. The equivalent thermal conductivity of the micro/nano scaled periodic cubic frame silver and its thermal radiation mechanism analysis. Energies. 2021;14(14):4158. doi:10.3390/en14144158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Yu C, Li H, Wu R. Performance analysis of porous solar absorbers with high-temperature radiation cooling function. Chin Phys B. 2025;34(6):068102. doi:10.1088/1674-1056/add4e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Yang HU, D’Archangel J, Sundheimer ML, Tucker E, Boreman GD, Raschke MB. Optical dielectric function of silver. Phys Rev B. 2015;91(23):235137. doi:10.1103/physrevb.91.235137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Querry MR. Optical constants of minerals and other materials from the millimeter to the ultraviolet. In: Aberdeen proving ground. Gaithersburg, MD, USA: Chemical Research, Development & Engineering Center, US Army Armament Munitions Chemical Command; 1998. [Google Scholar]

30. Olson E. Particle shape factors and their use in image analysis—part 1: theory [Internet]. [cited 2025 Aug 1]. Available from: https://particletechlabs.com/ptl-press/particle-shape-factors-and-their-use-in-image-analysis-part-1-theory/#. [Google Scholar]

31. Guimarães TF, Lanchote AD, da Costa JS, Viçosa AL, de Freitas LAP. A multivariate approach applied to quality on particle engineering of spray-dried mannitol. Adv Powder Technol. 2015;26(4):1094–101. doi:10.1016/j.apt.2015.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools