Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Thermal Performance Assessment of a Trombe Wall in Social Housing through Numerical Simulation: A Case Study in Mexico

1 División de Estudios de Posgrado e Investigación, Tecnológico Nacional de México/IT de Pachuca, Colonia Venta Prieta, Pachuca de Soto, C.P. 42080, Mexico

2 Grupo de Investigación IRSE, Departamento de Ingeniería Mecánica, División de Ingenierías, Campus Irapuato-Salamanca, Universidad de Guanajuato, Salamanca, C.P. 36885, Mexico

3 Departamento de Ingeniería en Aeronáutica, Universidad Politécnica Metropolitana de Hidalgo, Tolcayuca, C.P. 43860, Mexico

* Corresponding Author: J. Serrano-Arellano. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Cooling Systems: Design, Optimization, and Applications)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(6), 2073-2107. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.069564

Received 26 June 2025; Accepted 19 September 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

The Trombe Wall (TW) is a low-cost, passive heating system known for its high thermal efficiency, particularly in cold and temperate climates. Recent research has explored its adaptability to warm-dry climates with high thermal variability, such as those found in central Mexico. This study presents a dynamic simulation-based analysis of the TW’s thermal performance in a representative social housing unit located in Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo. Two models were compared—one with a south-facing TW system and one without—to evaluate indoor thermal comfort throughout a full annual cycle. The simulations were conducted using OpenStudio and EnergyPlus, integrating detailed climate data and construction parameters. Results indicate significant improvements in interior temperature stability and comfort during winter, with temperature increases of up to 5.1°C in living areas. The system’s implementation made it possible to attain a new level of average winter indoor temperature of 18.3°C by using solar energy, up from 14.4°C without mechanical heating. The introduction of the TW significantly reduces the interior thermal oscillation and enhances the habitability conditions during the winter, with an increase of 167% in the annual number of hours within the thermal comfort range of 18°C–24°C vs. the base model. Currently, temperature fluctuations inside buildings due to climate change affect the health of users. The system presented in this study reduces these temperature fluctuations to improve quality of life.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

The building sector accounts for about 36% of global energy consumption and 39% of energy-related CO2 emissions [1]. Faced with this challenge, passive design presents itself as an effective strategy to improve thermal comfort without relying on active systems. Among the available solutions, the Trombe wall (TW) stands out for its ability to capture, store and transfer solar heat. Its design—a dark thermal mass behind glass, separated by an air chamber—allows taking advantage of the principles of radiation, conduction and natural convection to heat the interior progressively [2], Although its effectiveness has been proven in cold regions since its original development in France in 1967 [3], its application in Mexican social housing is still limited. This study evaluates the thermal performance of the TW in a typical dwelling in Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, where the temperate-subhumid climate and the daily thermal oscillation make it potentially effective. Two scenarios are compared: a house without passive strategies and another with a south-facing convective TW. The dynamic simulation was performed in EnergyPlus with real climate data (TMYx 2009–2023) and evaluated under comfort criteria established by ASHRAE 55 and the Givoni chart. The hypothesis proposes that TW can significantly improve indoor comfort without mechanical air conditioning, which positions it as a replicable, economical and sustainable option for energy vulnerable contexts. The TW has been widely investigated as a low cost and high efficiency passive solution for thermal conditioning in buildings. Although traditionally applied in cold or temperate climates, its usefulness has been re-evaluated in contexts with high thermal variability and hot-dry climates, as in various regions of Mexico. This section reviews key studies published between 2022 and 2025 on the thermal performance of TW, focusing on its benefits for comfort and energy efficiency, as well as its limitations for social housing. The papers are grouped into two methodological categories: theoretical studies (Table 1) and experimental studies (Table 2).

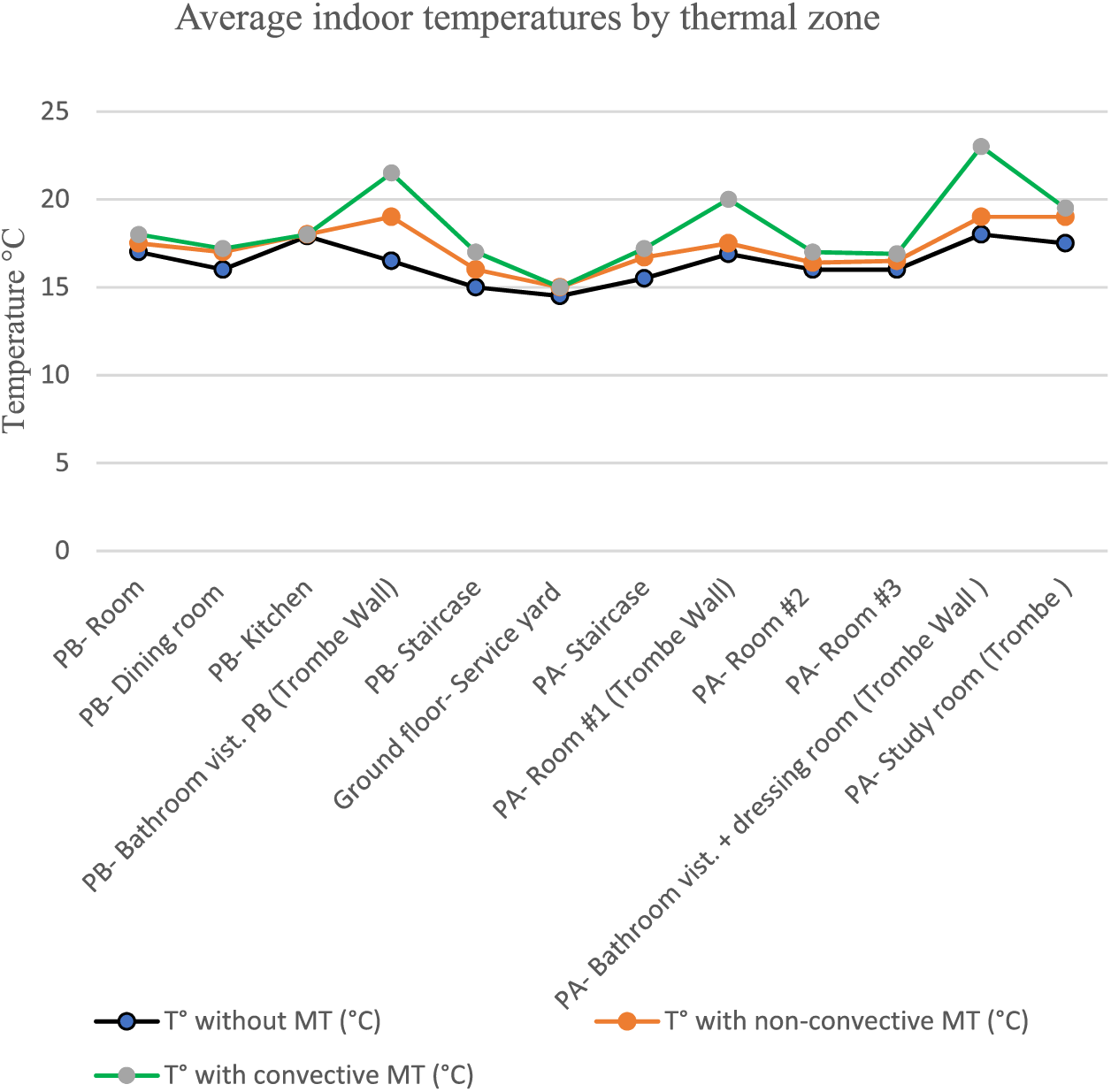

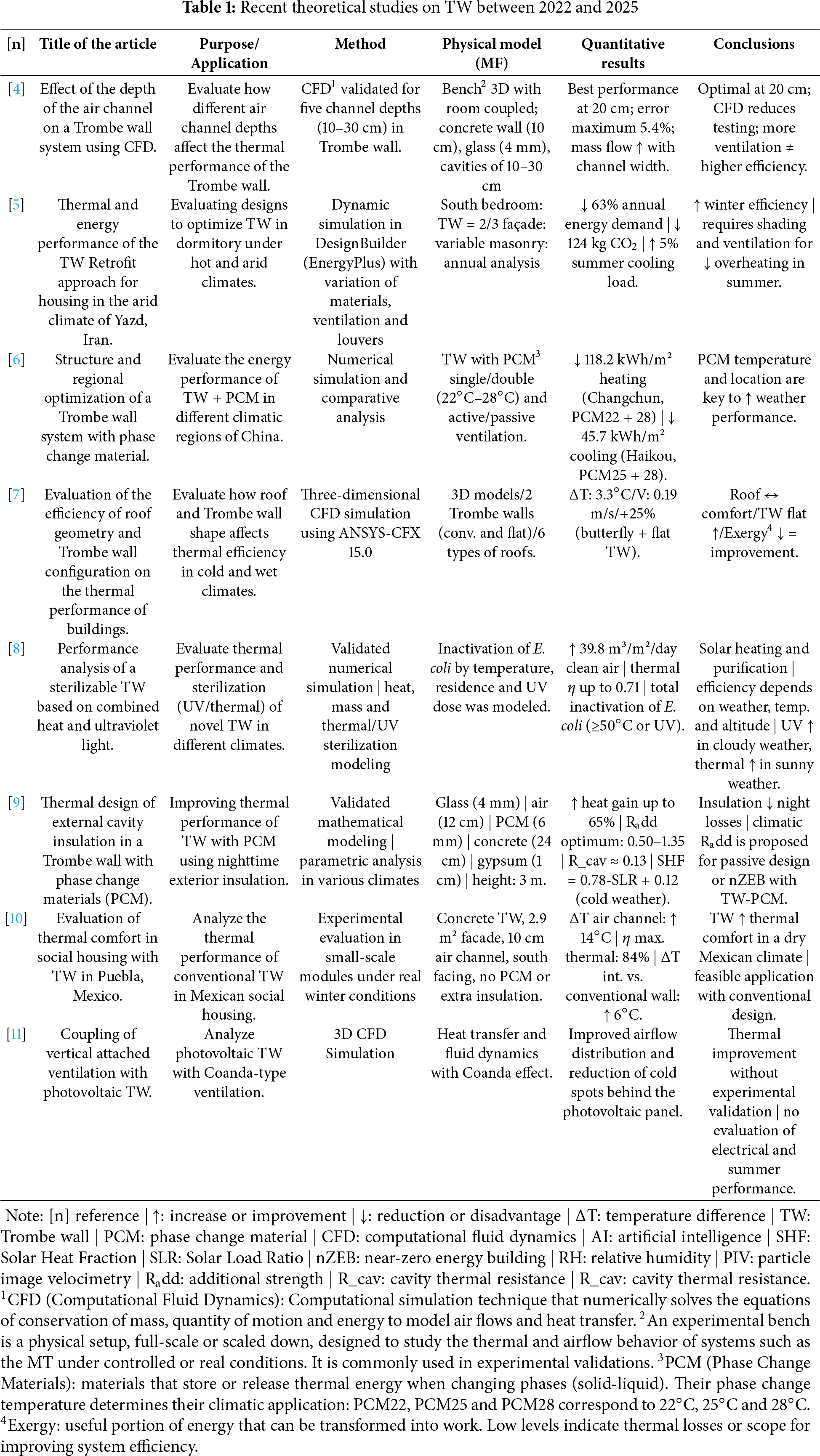

This theoretical block Table 1 summarizes recent research (2022–2025) that evaluates the thermal and energy performance of the TW through numerical simulations and advanced computational modeling. These investigations explore variables such as air channel depth, use of phase change materials (PCM), system geometry, climatic conditions, and application of artificial intelligence. The use of PCM stands out for its ability to improve the seasonal efficiency of TW. Studies such as [6] report energy reductions of up to 39% by incorporating double layers of PCM with optimum depths. Likewise, thermal gains of more than 118 kWh/m²/year are recorded by adjusting the PCM melting temperature to the local climate. Simulation tools such as CFD, EnergyPlus and ANSYS allow modeling thermal behavior with high accuracy. For example, Ref. [10] determines that a 20 cm cavity optimizes heat flow, Ref. [7] reports 25% improvements by modifying the roof geometry and the TW. Some studies extend the function of the system, integrating air purification, UV sterilization or assisted ventilation, as in [8] and [9] reflecting a transition towards hybrid heating, ventilation and power generation solutions. One such study is presented by [11], who analyzed the use of a Trombe wall with reflective panels, achieving a reduction in energy costs and, indirectly, carbon emissions. The study focused on a multi-level building, achieving a 25% reduction in emissions. Finally, the study [10], carried out in Puebla with a conventional TW, shows an increase of up to 6°C in the interior temperature and 84% thermal efficiency, validating its applicability in Mexican social housing. This theoretical review evidences the potential of TW but also underlines the need for experimental validation in real contexts, as will be addressed in the following section.

The Table 2 shows recent research on TW shows an evolution towards multifunctional systems that integrate technologies such as PCMs, photovoltaic modules, cavities with partial vacuum, catalysts and unconventional geometries (zigzag, multichannel). These innovations seek to optimize solar gain and expand the functions of the TW, incorporating natural ventilation, air purification and power generation, in line with passive design principles and nZEB objectives. Methodologically, the studies combine advanced simulations (CFD, transient and multivariable models) with empirical validations in real or controlled contexts. This integration makes it possible to improve thermal performance and adapt it to different climatic conditions and housing typologies. Despite the encouraging results—such as efficiency increases of more than 30%, reduction of thermal losses and improvements in ventilation—there are gaps in longitudinal studies and cost-benefit analysis. These areas should be strengthened to consolidate TW as a viable strategy in sustainable housing public policies.

This study analyzed two case studies. First, a typical dwelling in the region was identified. Subsequently, an energy consumption and interior temperature analysis was performed. The results were found to be unfavorable for thermal comfort. In the second case, an inclined Trombe wall was incorporated, adding a unique element to the dwelling type, giving it aesthetic and functional value. The incorporation of this passive system reduced changes in the home’s interior temperature, reduced energy costs by discontinuing the use of mechanical systems and indirectly contributed to reducing carbon emissions.

Before detailing the design of the Trombe system and its implementation, this section describes the methodological approach adopted to evaluate its thermal performance under real conditions. A comprehensive energy model was developed through dynamic simulation, with the objective of comparing the impact of the TW on indoor comfort in a representative dwelling in the Mexican urban context. The methodology considers climatic, construction and use parameters, guaranteeing a rigorous and replicable evaluation.

System Description and Case Study

The case study corresponds to a two-story social housing located in Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo (2400 m a.s.l.), in a temperate sub-humid climate (C(w1) according to INEGI), with an average annual temperature of 14.2°C, marked daily thermal oscillation and an average solar irradiance of 5.3 kWh/m²-day.

Two comparative scenarios were modeled:

• Base model, without passive strategies.

• Experimental model, with TW attached to the south façade.

The designed Trombe system has an area of 4.8 m² (2.40 × 2.00 m) and consists of: solid block thermal wall (15 cm), with matte black coating (α ≈ 0.9). 10 cm air chamber for natural convection and 6 mm clear glass (τ ≈ 0.85).

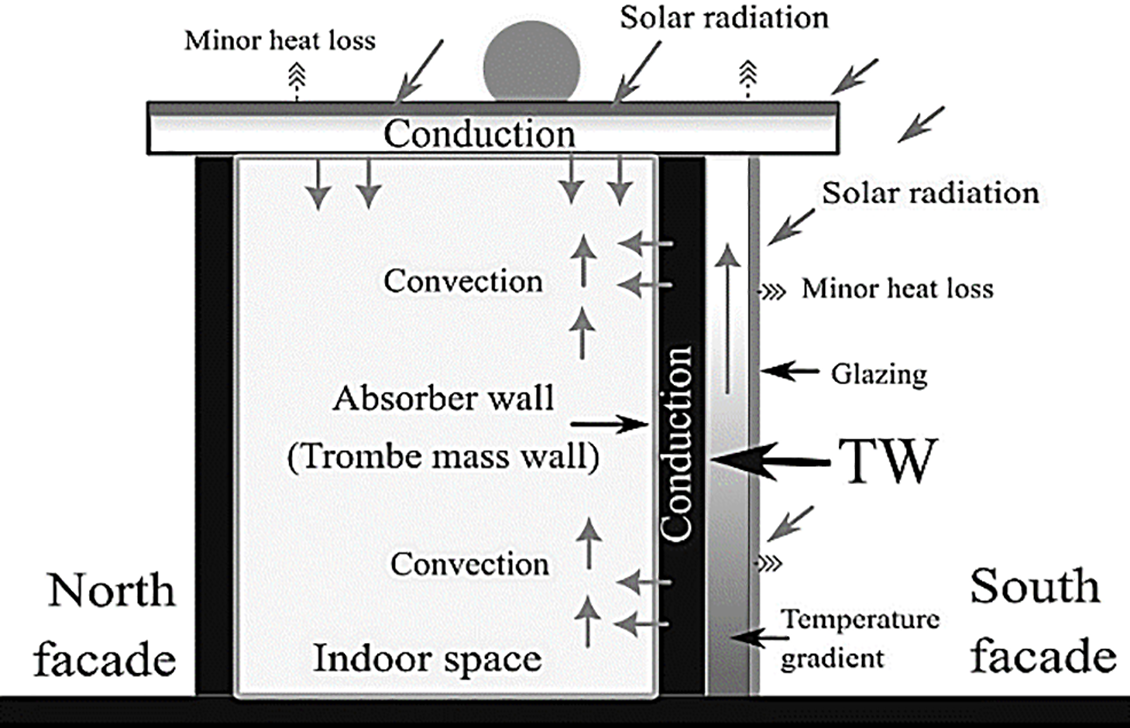

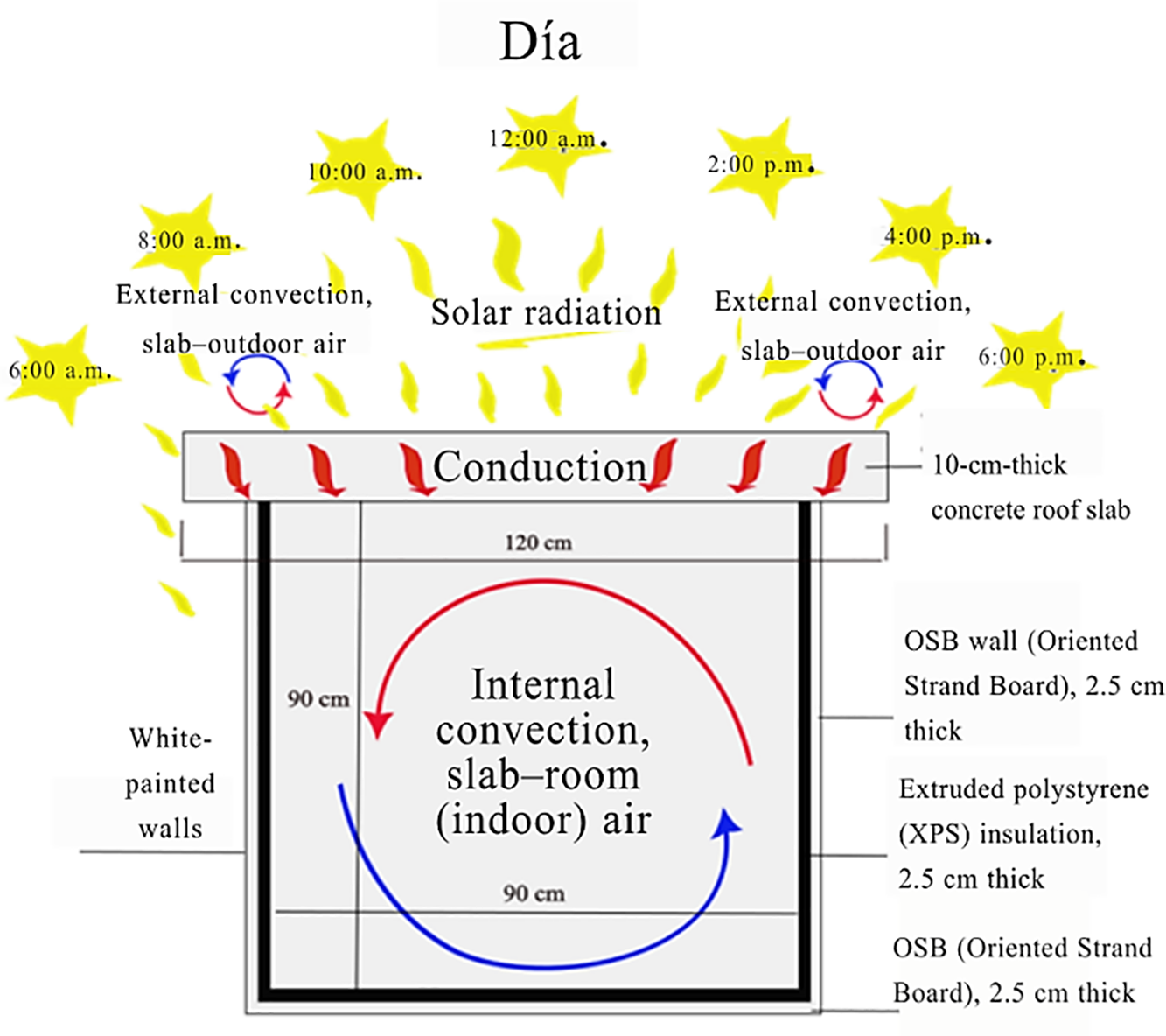

During the day, radiation passes through the glass and is absorbed by the wall, generating upward convection in the chamber (chimney effect) and heat transfer to the interior by conduction. During the night, the wall releases the accumulated heat, stabilizing the temperature without mechanical intervention. This operation is represented in Fig. 1 and is analyzed using radiation, conduction and convection principles, applying expressions based on Beer-Lambert, Fourier and natural convection laws.

Figure 1: Diagram of the thermal performance of the TW in a south-facing dwelling

In Fig. 1, the thermal behavior of the Trombe wall is based on three main heat transfer mechanisms: radiation, conduction and convection. These processes act simultaneously to capture, store and distribute energy to the interior. Mathematical expressions based on the physical properties of the materials and the specific environmental conditions of the study site are used to quantify their contribution.

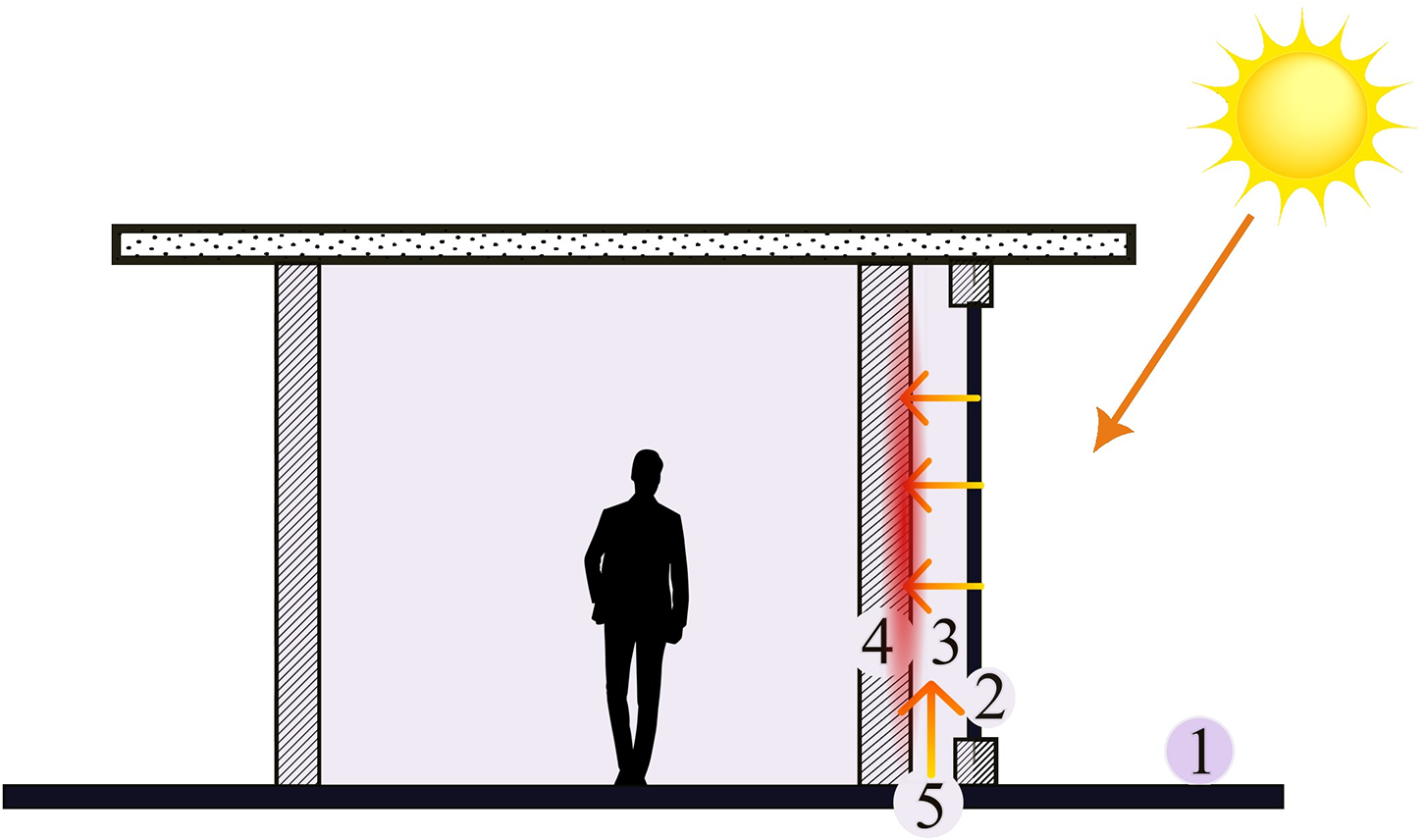

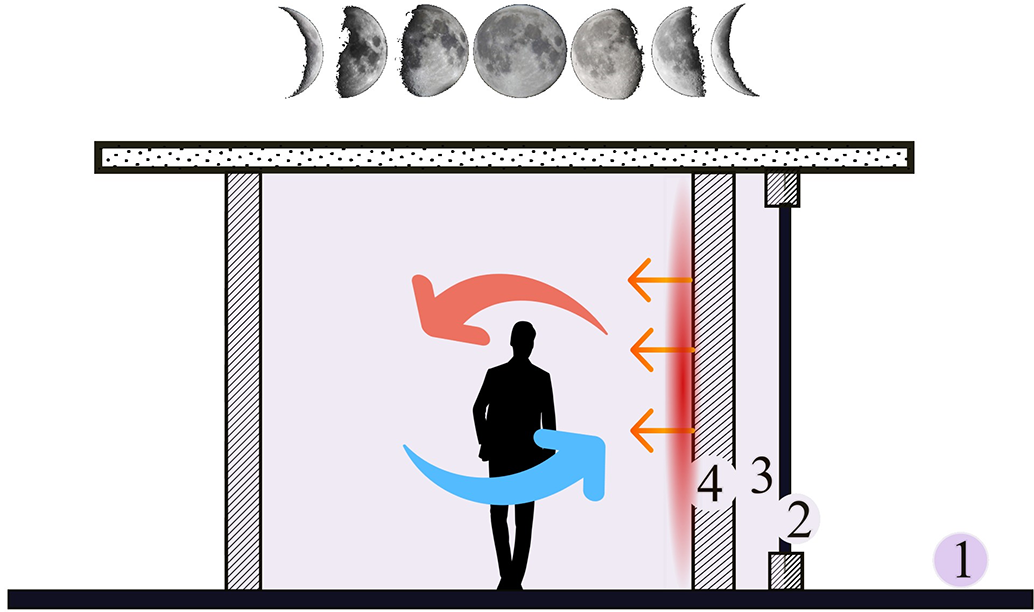

Fig. 2 represents the phenomenon of solar radiation between the Trombe wall and the interior of the room and Fig. 3 represents the physical phenomenon during the night.

Figure 2: Thermal functioning of a Trombe Wall system during winter conditions. Solar radiation enters through the glazing 2, heats the air cavity 3, and is absorbed by the thermal mass wall 4, generating buoyant airflow 5 and inward heat transfer 1

Figure 3: Nighttime thermal behavior of a Trombe Wall system. The heat stored in the thermal mass 4 is gradually released into the indoor space through conduction, while the exterior environment 1 promotes radiative losses. Convection may be inhibited or reversed in the air cavity 3, and the glazing 2 acts as a partial insulator

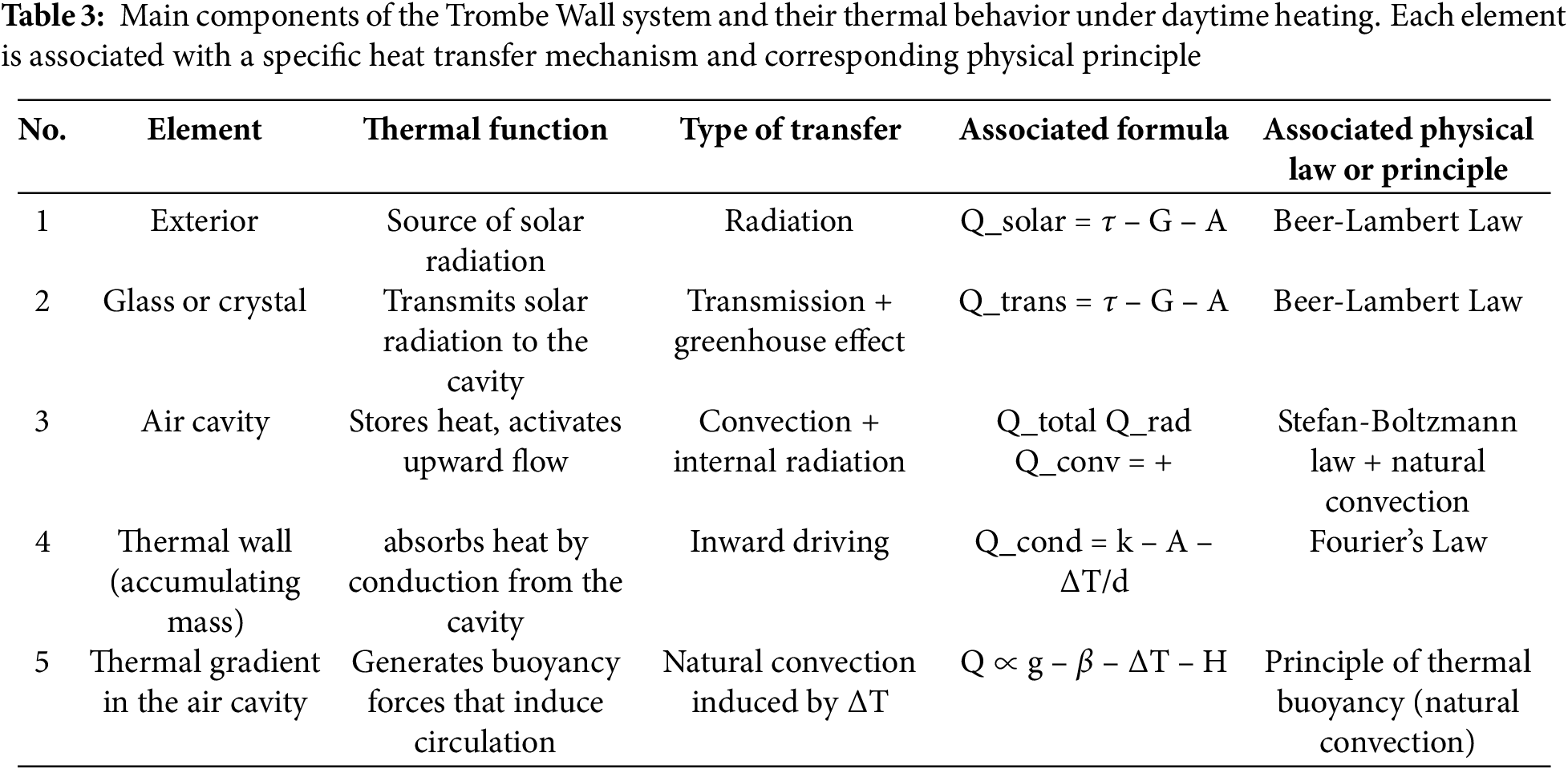

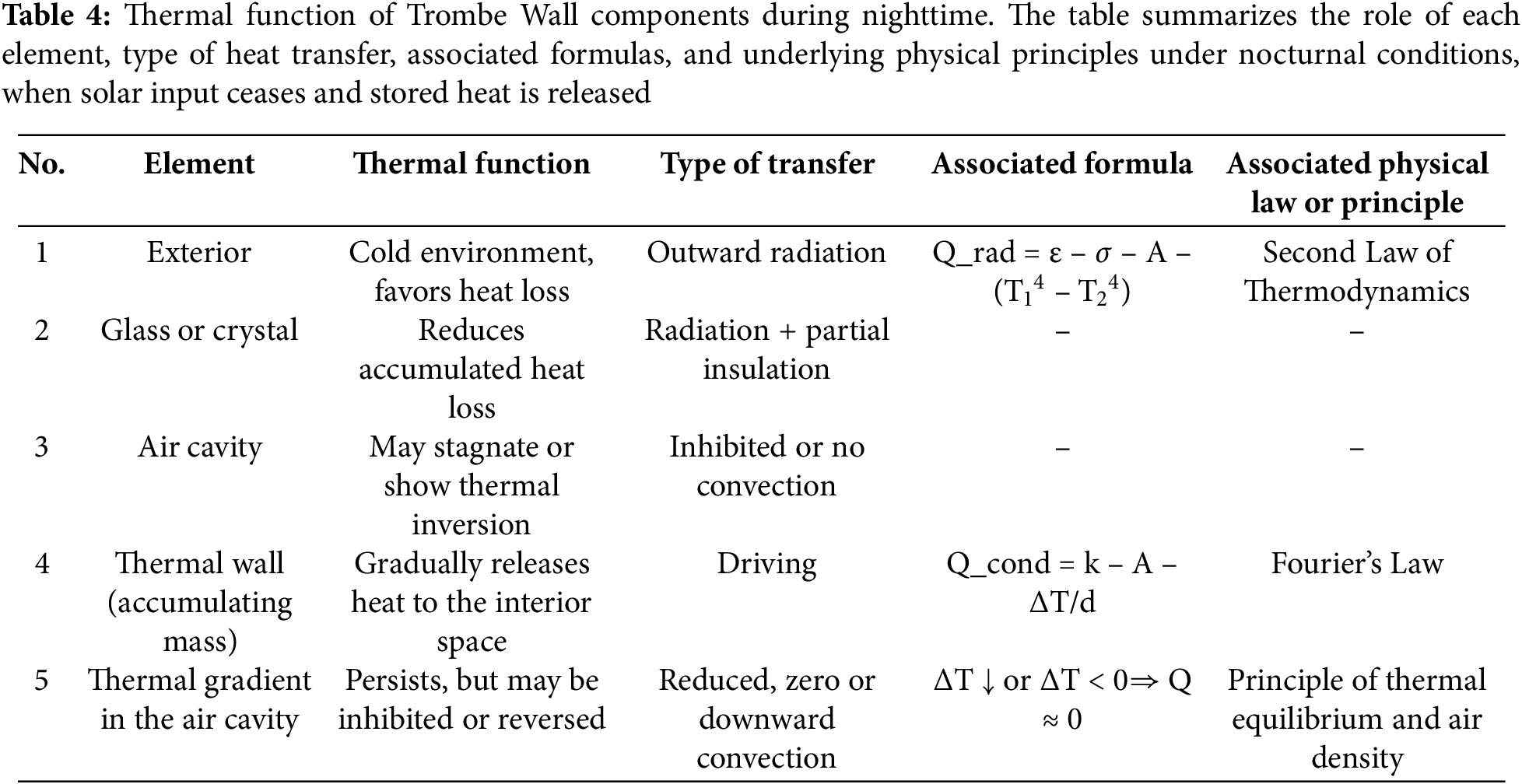

Table 3 shows a summary of the elements that interact in the Trombe wall, thus simplifying the understanding of the physical phenomenon involved.

Table 4 shows a summary of the behavior of the elements that interact with the Trombe wall at night, this is different from that shown in Table 3.

Calculation of the inclination of the Trombe system: the TW tilt was determined based on the geographical latitude of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, located at 20.12° N. According to passive solar design principles and the criteria established by Balcomb [27] and Tiwari [28], the optimum tilt of a flat plate solar collector for winter heating is obtained by adding between 10° and 20° to the latitude of the site:

Therefore, an inclination of 38° with respect to the horizontal plane was not adopted, but of 25.5° due to the structural load it would represent a value that is within the recommended range for temperate-sub-humid climates with high daily thermal oscillation. This inclination allows for direct solar gain during the winter months, improving the efficiency of the TW during the period of highest thermal demand. Both the thermal mass wall and the exterior glass were designed following this same inclination, integrated by means of a south-facing support structure, in accordance with the principles of bioclimatic design in the northern hemisphere.

The Trombe system proposed in this study consists of three main components that, together, seek to improve the thermal performance of social housing through a passive, accessible, replicable and low-cost strategy. In particular, it is composed of three key elements:

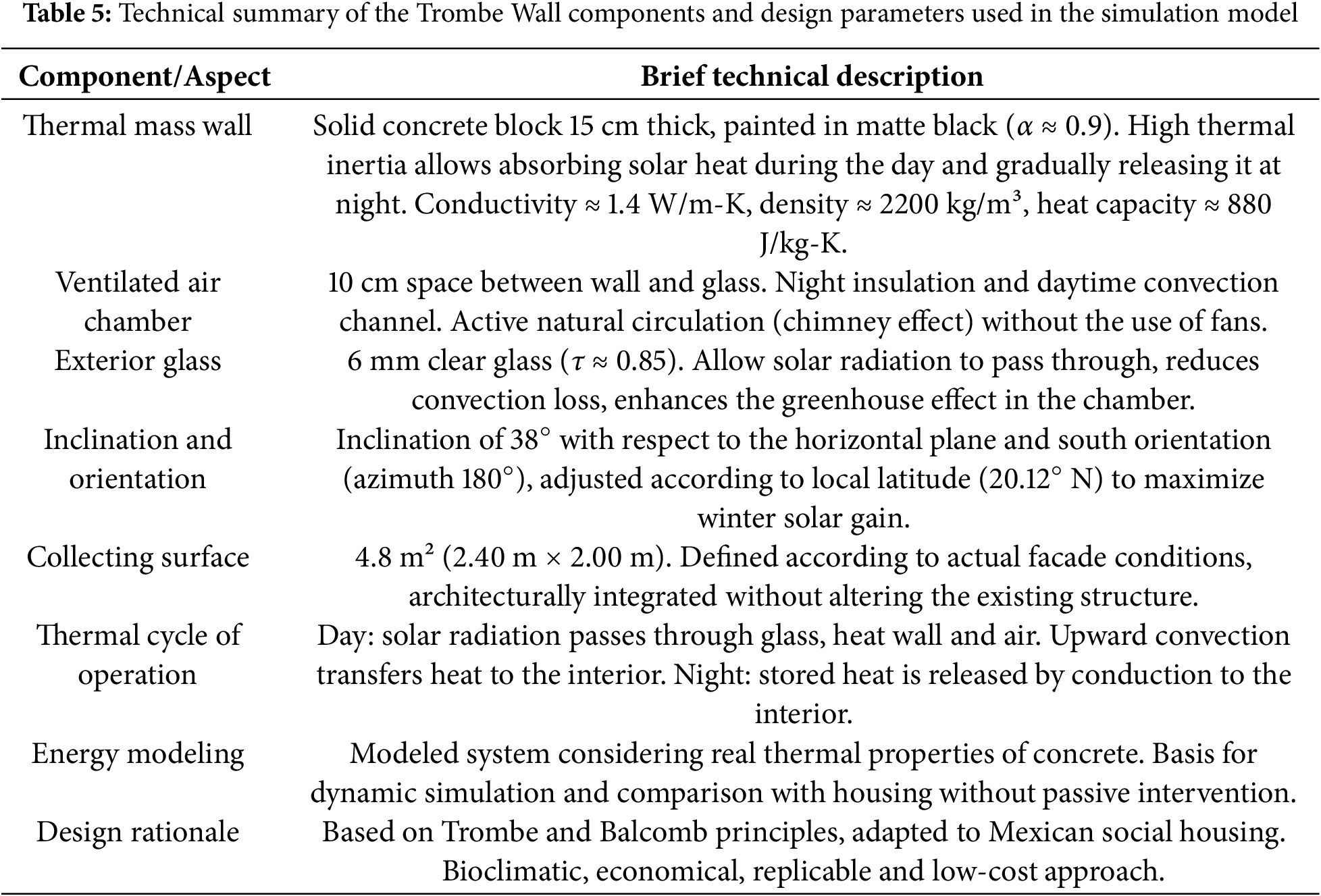

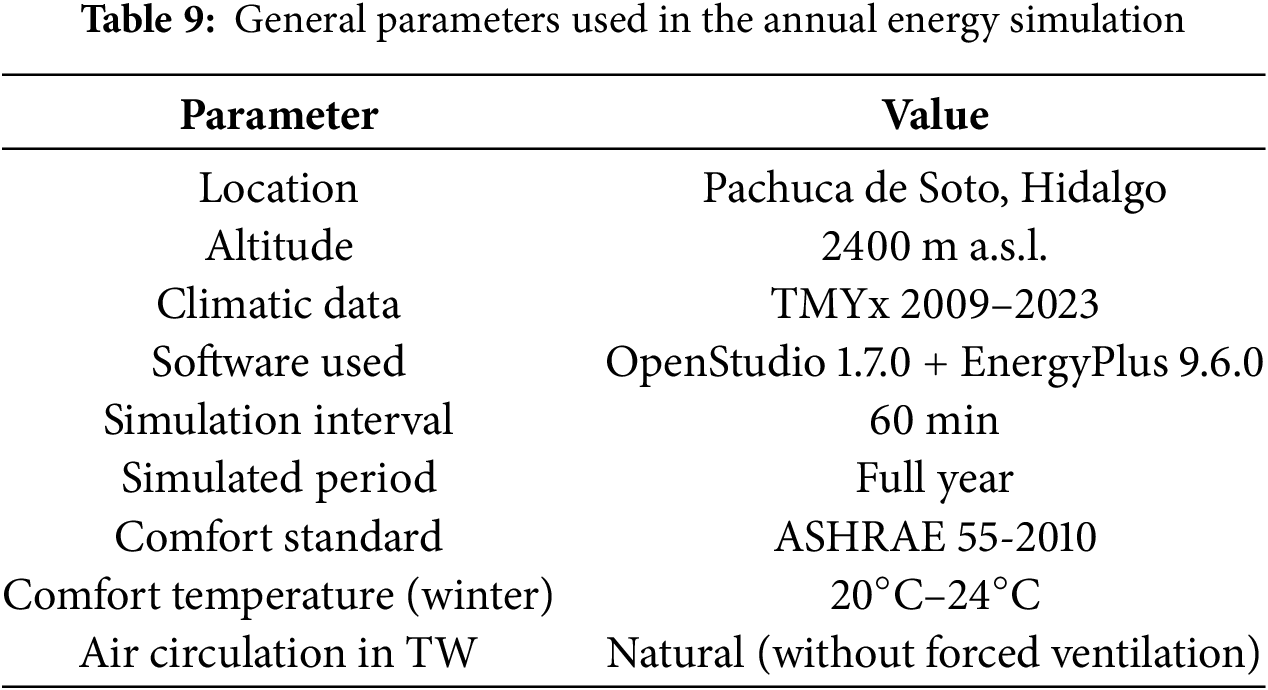

The physical and operational characteristics of the Trombe wall are shown in Table 5, with a brief description of each of them. The evaluation was performed using an interoperable and internationally validated environment, consisting of SketchUp Pro 2022, OpenStudio 1.7.0 and EnergyPlus v9.6.0, ensuring accuracy and reproducibility. The architectural model was developed in SketchUp, integrating geometry, orientation, materials and location of the Trombe wall. It was then exported to OpenStudio to assign thermal zones, usage conditions, internal loads and passive strategies. EnergyPlus solved the heat balance using differential equations that integrate conduction, convection and radiation, considering hourly climatic conditions and specific material properties. For the climate analysis, a TMYx file (2009–2023) of Pachuca de Soto, generated with Element, was used, which allowed a continuous annual simulation (365 days) with an hourly resolution of 60 min and high climatic representativeness. The evaluation of thermal comfort was based on the ASHRAE 55-2010 standard, adopting an acceptable range of 20°C–24°C for winter. Annual comfort hours were calculated for both models (with and without TW), considering only living spaces. The energy simulation was carried out on a two-story architectural model, representative of an urban social housing in Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo. The thermal impact of the TW in different spaces was evaluated under real conditions of climate, use and occupancy.

The analysis covered a continuous period of 365 days with hourly resolution (60 min), using a TMYx file (2009–2023) that includes temperature, solar radiation, humidity, wind and cloudiness.

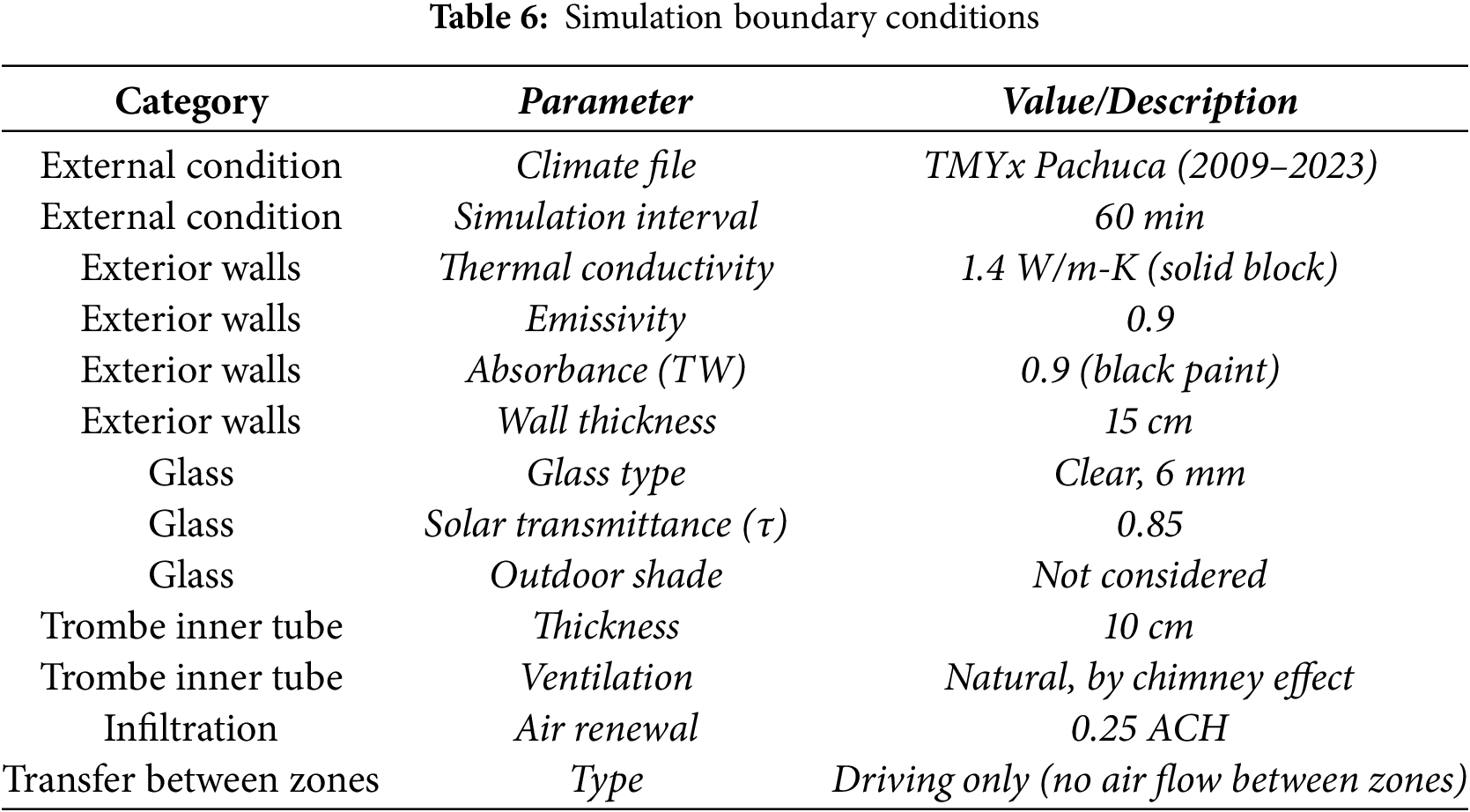

Detailed boundary conditions were defined for each envelope element:

• Walls: conductivity 1.4 W/m-K, emissivity 0.9, solar absorptance 0.9 (in the TW).

• Glazing: 6 mm, solar transmittance 0.85, without solar control devices.

• Infiltration: 0.25 ACH, without mechanical ventilation.

The configuration of the model ensures a passive and coherent evaluation, considering materials, geometry, natural ventilation and local climatic conditions.

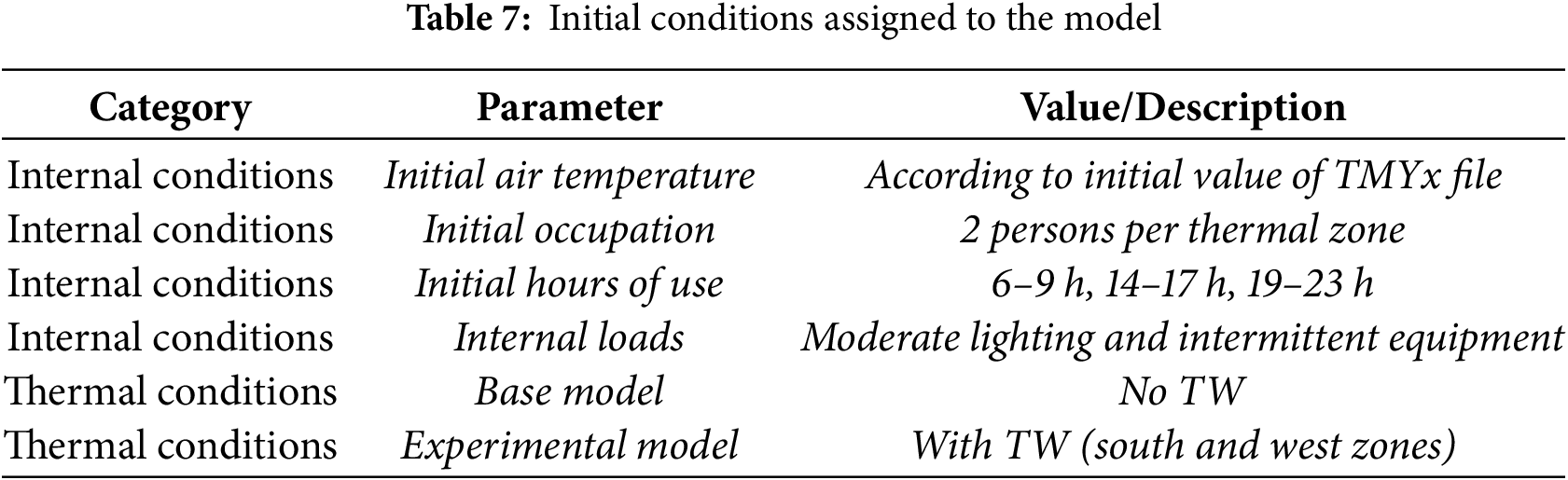

In addition to the physical boundary conditions, a series of initial conditions were established to define the thermal and usage state of the model at the beginning of the simulation. These parameters contemplate the typical occupational behavior of social housing, as well as the comparative configuration between the base model and the experimental model. The following table presents the internal and thermal conditions assigned to the simulation model:

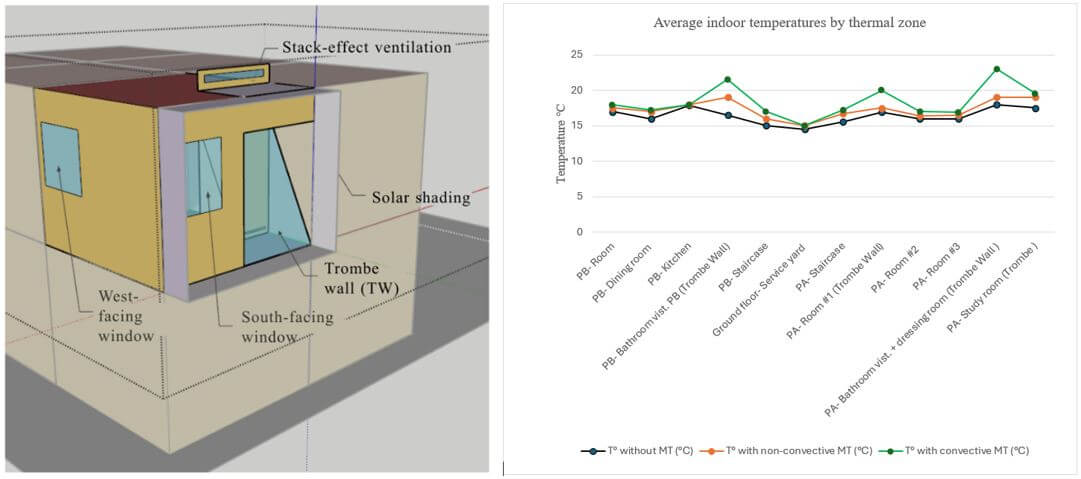

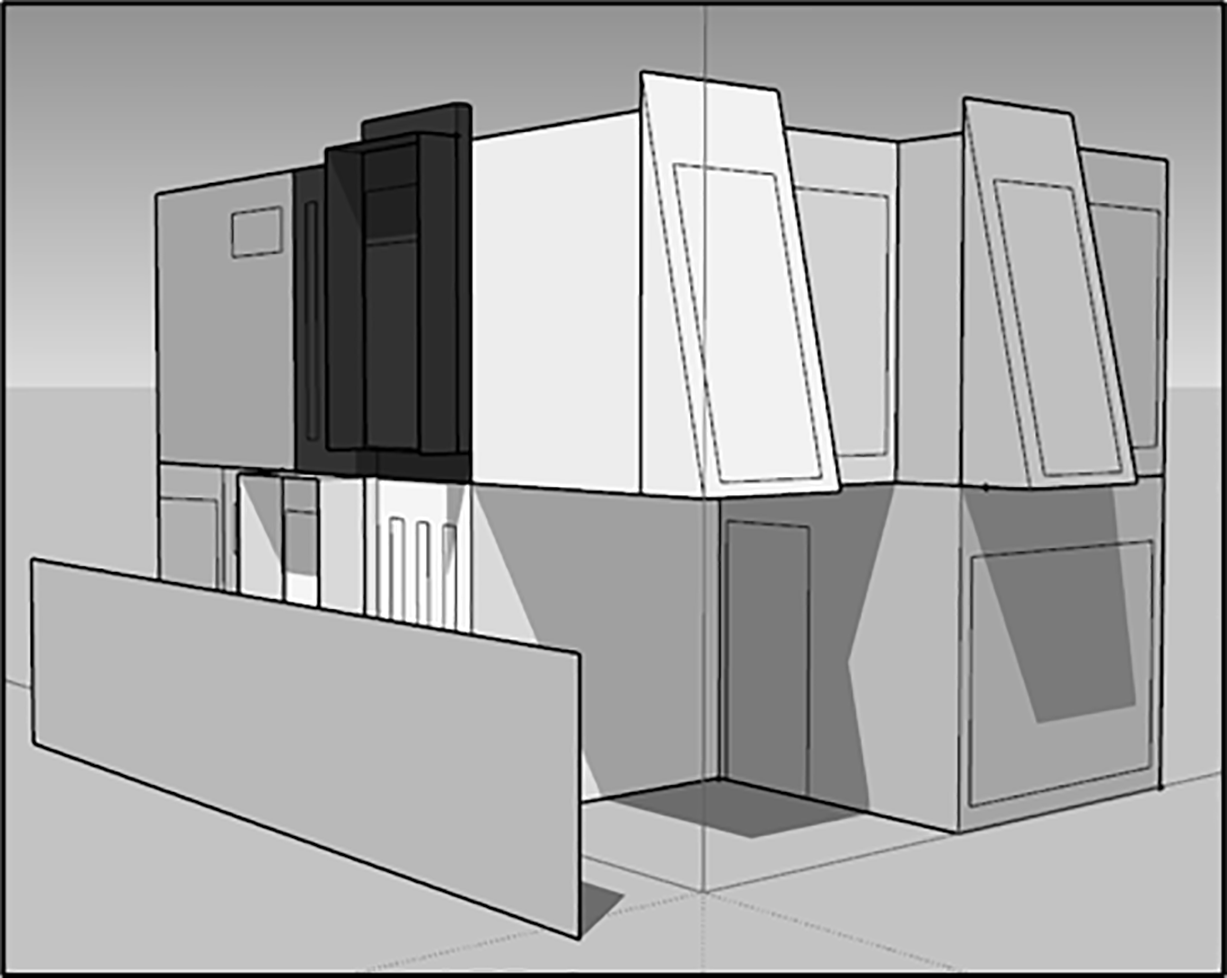

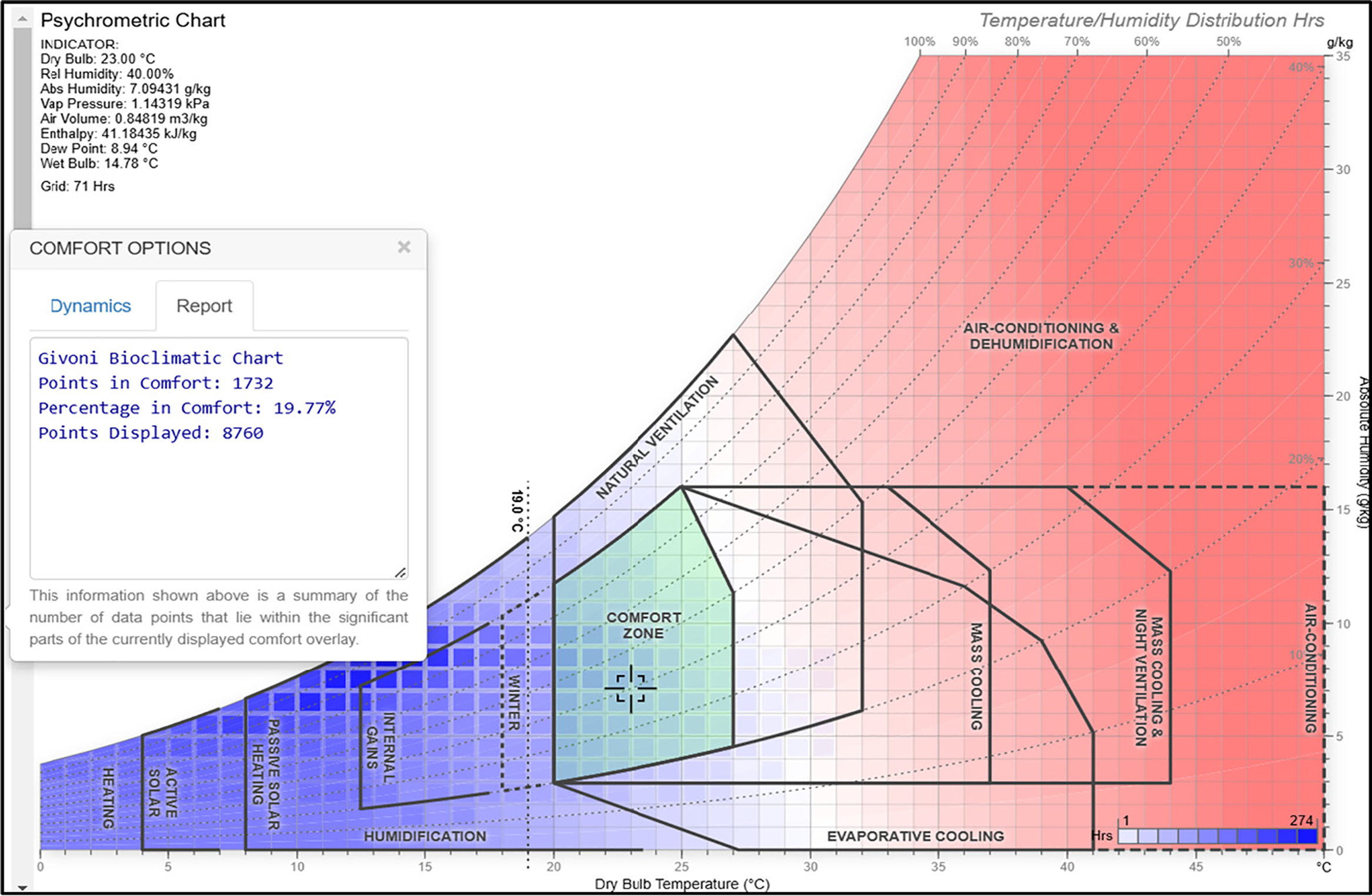

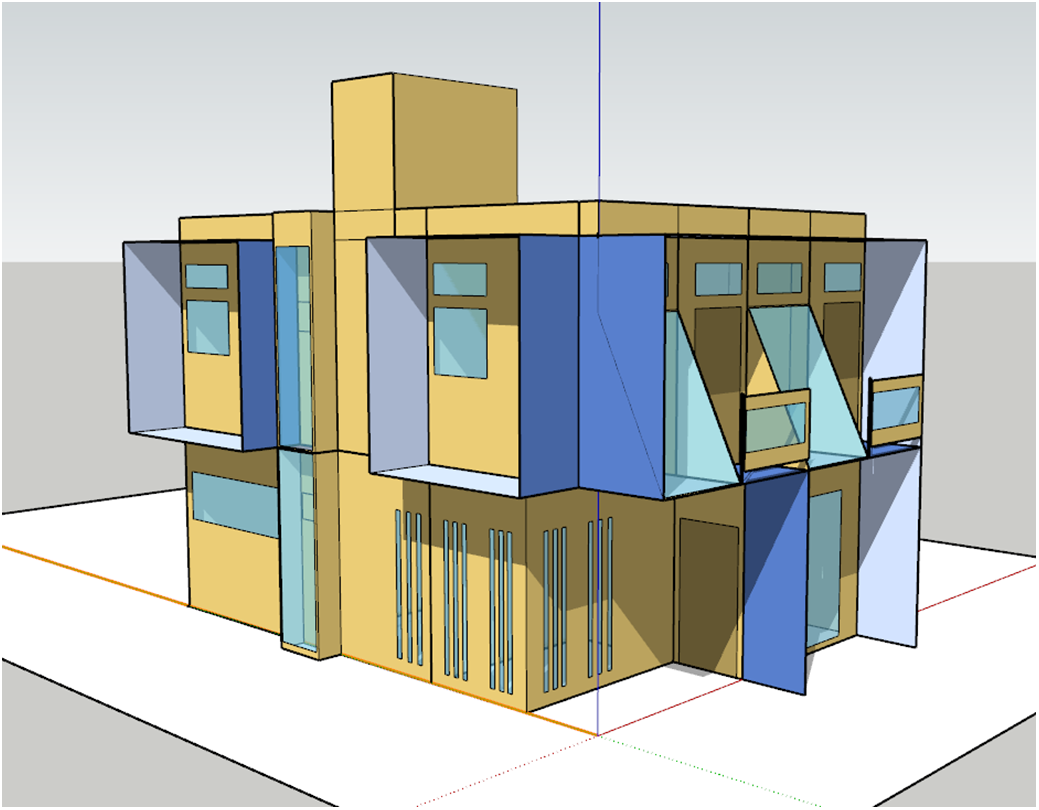

Tables 6 and 7 show the physical parameters and initial conditions for simulating the Trombe wall. Internal loads (occupancy, lighting and appliance use) were defined according to typical residential profiles, as recommended by ASHRAE and default settings in OpenStudio. Thermal zones were modeled as closed compartments with heat transfer by conduction through adjacent walls, ceilings and slabs, with no air recirculation between zones. Following the general configuration outlined above, two variants of the same residential unit were simulated to evaluate the thermal impact of the Trombe Wall (TW) via direct comparative analysis: Base model: house without TW, used as a reference. And an experimental model: housing with TW incorporated in strategic spaces. The architectural model was developed in SketchUp Pro, while the thermal zoning and energy configuration were performed in OpenStudio, defining a total of seven independent thermal zones, distributed as follows: First floor: living-dining room, kitchen, full bathroom and service patio. Upstairs: three bedrooms (two facing south) and two bathrooms, one of them facing west, as shown in Fig. 4. These areas were configured as enclosed spaces with specific thermal properties, which allowed a differentiated analysis of the thermal behavior of each one in both models. The selection of south and west facing rooms to integrate the Trombe wall responds to criteria of strategic solar gain and impact assessment according to exposure. The Fig. 5 shows the three-dimensional model of the house generated in SketchUp Pro, with the TWs integrated in the facades exposed to higher solar radiation. On the upper floor, the system is incorporated in two south-facing rooms, as well as in a west-facing bathroom, which allows evaluating the thermal performance of the TW under different solar exposure conditions. This layout responds to bioclimatic design criteria and was faithfully replicated in the energy simulation environment to ensure a realistic evaluation.

Figure 4: Architectural model of the house with attached Trombe walls on the south and west facades

Figure 5: Configuration of thermal zones associated with the TW in OpenStudio

The comparison between the base model and the experimental model was made by thermal zones, making it possible to identify the impact of the TW according to orientation, use and time of day or year. This approach made it possible to evaluate not only the thermal gain, but also the interior stability against external conditions. In addition to quantifying the energy performance, the applicability of the system in Mexican social housing was assessed, considering its replicability and climate adaptation. To ensure the reliability of the results, a cross-validation strategy was implemented, detailed in the following section. To verify the reliability of the energy simulation, a cross-validation strategy based on three complementary approaches was implemented:

• Empirical comparison: The temperatures of the base model (without TW) were consistent with ranges recorded in social housing in the Mexican highlands (16°C–18°C in winter).

• Literature review: The thermal increases of 3°C to 5°C in the experimental model agree with previous studies on similar passive systems.

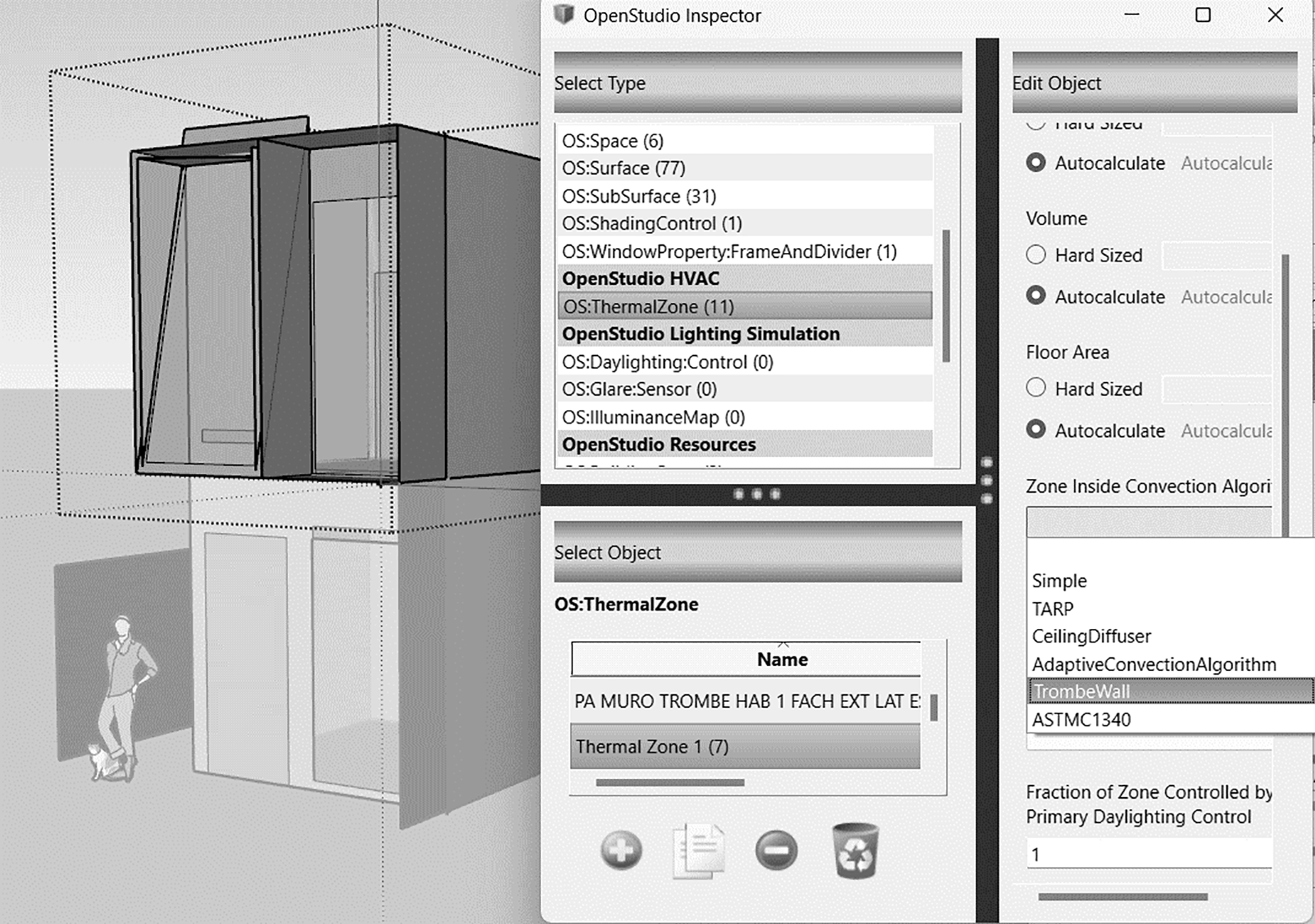

• Psychrometric representation: Climate Consultant 6.0 and the Givoni diagram were used to plot the impact of the TW. Under direct solar gain and partial shade, the system maintained 19.77% of the time in the winter comfort zone (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Psychrometric analysis of thermal comfort with Trombe wall using Climate Consultant 6.0 (Givoni Bioclimatic Chart) [29]

These three approaches reinforce the validity of the model, showing consistency between simulation, background and graphical representation. Specific thermal properties were incorporated for each system material (solid block, glass, air, concrete and ceramic), according to EnergyPlus and ASHRAE databases. This ensures accurate modeling of the behavior of TW under varying conditions.

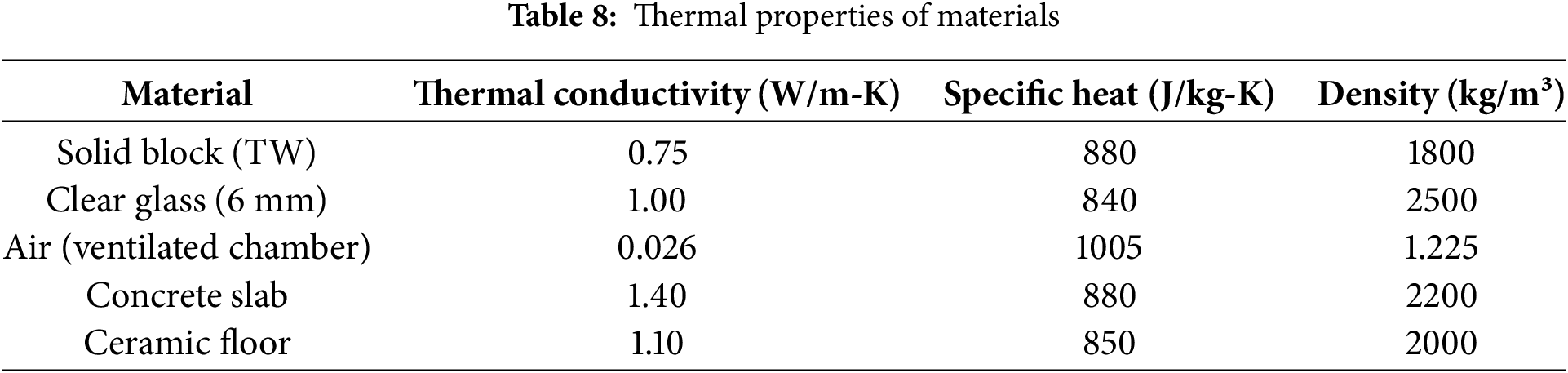

To ensure a faithful representation of the thermal behavior of the model, specific values of thermal conductivity, specific heat and density were assigned to the materials involved in the envelope and the Trombe system. These parameters are essential to calculate the conduction heat transfer and thermal storage capacity of the components. The following Table 8 summarizes the thermal properties used in the simulation model:

The thermal parameters used, taken from standardized bases such as EnergyPlus and ASHRAE, ensure a realistic modeling of the behavior of the TW. With this cross-validation, a solid framework is established for the analysis of results, which are presented below, differentiating intervened areas, seasons of the year and conditions of use. The simulation environment considered key parameters to ensure the validity of the model, Table 9 shows the general information for the housing simulation

With the purpose of evaluating the viability of TW as a passive heating strategy in low-income housing, a methodological sequence was developed based on four case studies. These cases were strategically selected to build a logical progression from the initial familiarization with energy simulation tools to the concrete application of the system in realistic conditions, under the climatic context of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo. Each case study responds to a specific objective within the process of validation and consolidation of the proposed approach. Together, they demonstrate the technical robustness of the methodology, the consistency of the results obtained and the applicability of the Trombe system in representative scenarios.

The following case studies were considered: Case Study #1—Partial reproduction of an article (simulated concrete roof in EnergyPlus). The purpose of this first exercise was to validate the use of EnergyPlus software by partially reproducing a published study. The boundary conditions, materials and thermal results were replicated to check the fidelity of the simulation against reference data. Case Study #2—Methodological reproduction of a residential model in Shenyang (DesignBuilder + EnergyPlus). An international study focused on the optimization of the thermal envelope through dynamic simulation was replicated. This exercise allowed to deepen in the management of critical variables for energy savings and to strengthen the mastery of the simulation environment. Case Study #3—Simulation of a low-income housing unit without a Trombe Wall. A typical house without passive intervention, representative of the urban housing stock in Pachuca de Soto, was modeled. This base model was used to identify the original thermal conditions of the living space, especially during the winter season, and to establish a baseline for comparison. Case study #4—Simulation of a new social housing design without TW, with TW (convective and non-convective). Finally, the Trombe system was modeled under two configurations (natural convection and without convection), integrated in the previously analyzed social housing. This case made it possible to quantify the thermal improvements achieved, evaluate the effectiveness of the system under real conditions and validate its relevance as a replicable bioclimatic solution. A detailed analysis of each of the cases developed is presented below, addressing their particular objectives, the energy modeling process and the results obtained. This step-by-step exploration forms the basis of the methodological framework used to validate the thermal performance of the TW.

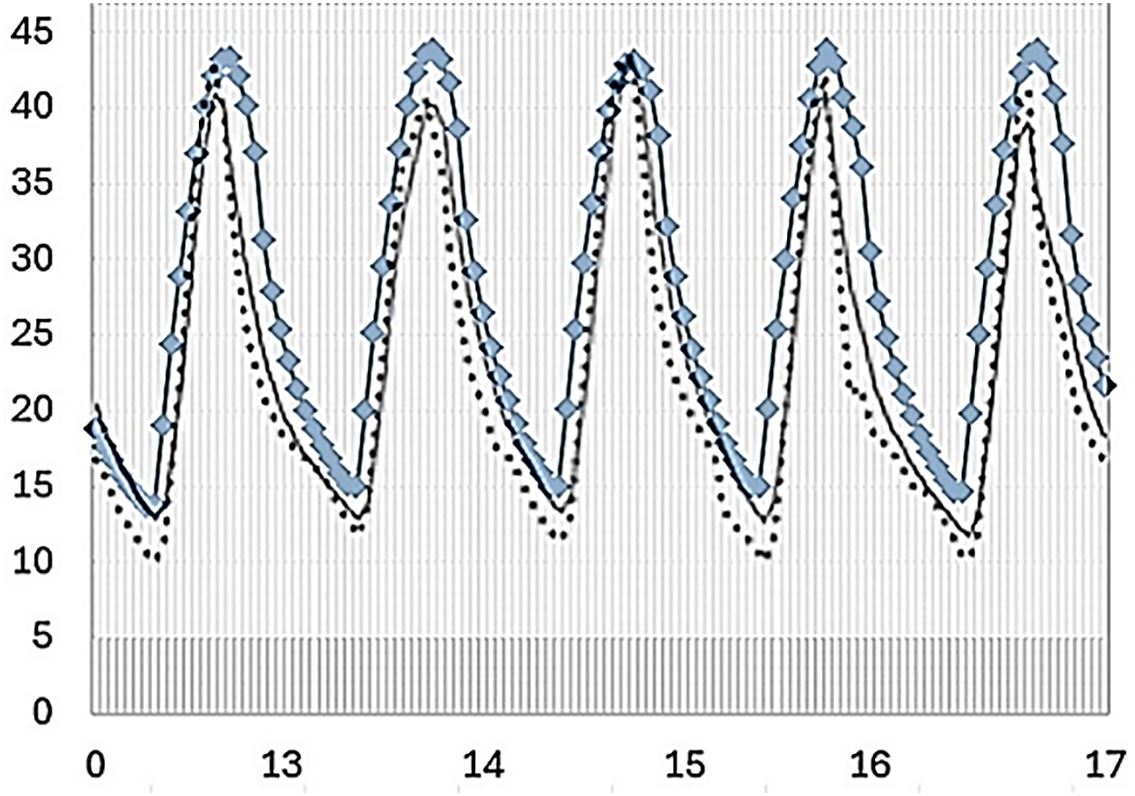

3.1 Case Study #1—Partial Reproduction of an Article (Simulated Concrete Roof in EnergyPlus)

This first case consisted of a partial reproduction of the study conducted by Avila-Hernandez et al. (2020) [30], Fig. 7 with the objective of validating the capability of the EnergyPlus software to simulate the thermal behavior of a traditional concrete roof exposed to typical climatic conditions of Cuernavaca, Mexico. The thermo-physical properties of the original building system were replicated and key parameters, such as solar absorptance and emissivity of the concrete, were adjusted in order to achieve an adequate correspondence between simulated and experimental results. The results obtained showed good agreement between the two thermal curves, with maximum differences of between 3°C and 5°C in the surface temperature peaks. The simulation was able to adequately reproduce the nocturnal thermal decrease observed in the original study, and it was possible to reduce the discrepancies by fine-tuning the model parameters.

Figure 7: Comparison between experimental (dotted line) [30] and simulated (solid line) roof surface temperature results for five consecutive days

3.2 Complementary Physical Modeling

As part of the analysis and interpretation process of the reproduced study, physical models’ representative of the daily thermal behavior of the traditional roof were developed. These models were used to qualitatively visualize the phenomenon of heat accumulation during the day and its release by night cooling, facilitating the understanding of the simulated thermal cycle.

Fig. 8 represents the scale experimental model that I made, which represents a closed cavity where the thermal radiation incident on the upper wall at different times of the day is being evaluated.

Figure 8: Representative physical model of the diurnal thermal behavior of the roof. Own elaboration based on data from Avila-Hernandez et al. (2020) [30]

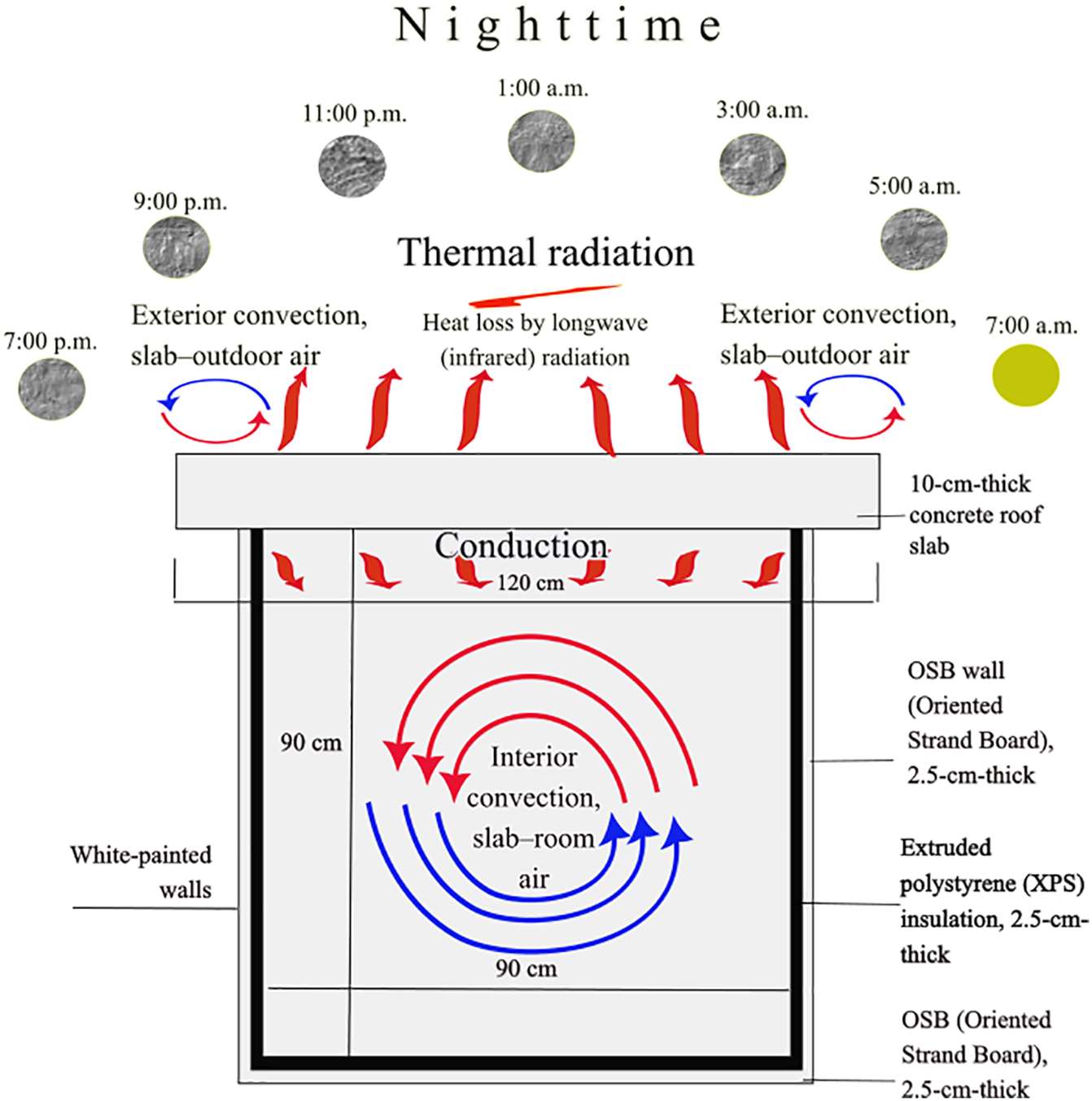

Fig. 9 represents the experimental model of the closed cavity evaluating the thermal behavior of the materials at night.

Figure 9: Representative physical model of the nocturnal thermal behavior of the roof. Own elaboration based on data from Avila-Hernandez et al. (2020) [30]

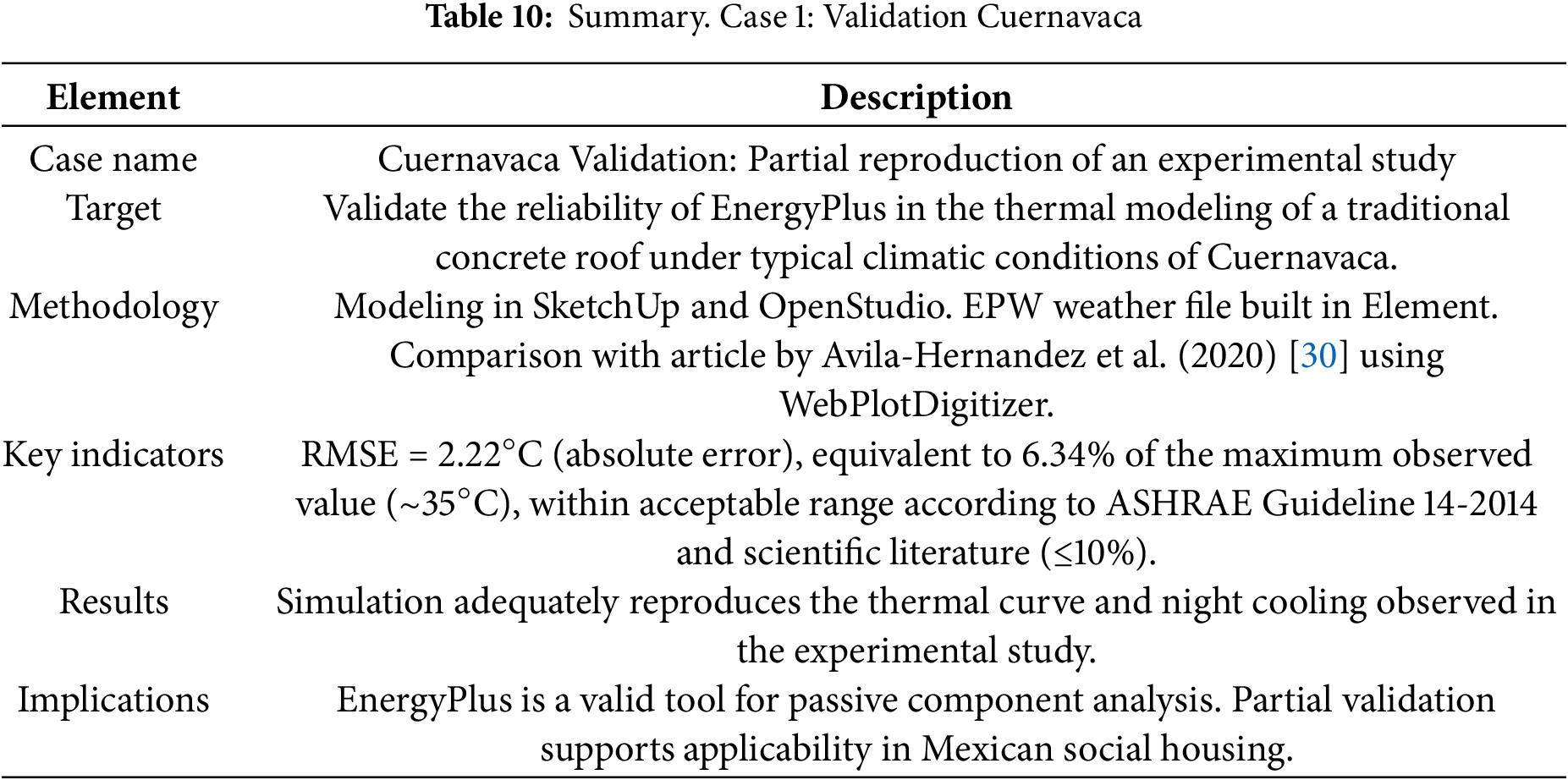

Table 10 shows a summary of the process followed to obtain the comparison results with Case 1. This exercise confirmed the ability of EnergyPlus to replicate real experimental conditions, laying the groundwork for its subsequent application in the analysis of more complex passive strategies, such as the Trombe wall. It also allowed the establishment of a technical protocol for climate preprocessing, which includes the conversion of hourly data, the calculation of astronomical parameters and the verification of compatibility with the simulation engine [31].

3.3 Case Study #2—Methodological Reproduction of a Residential Model in Shenyang (DesignBuilder + EnergyPlus)

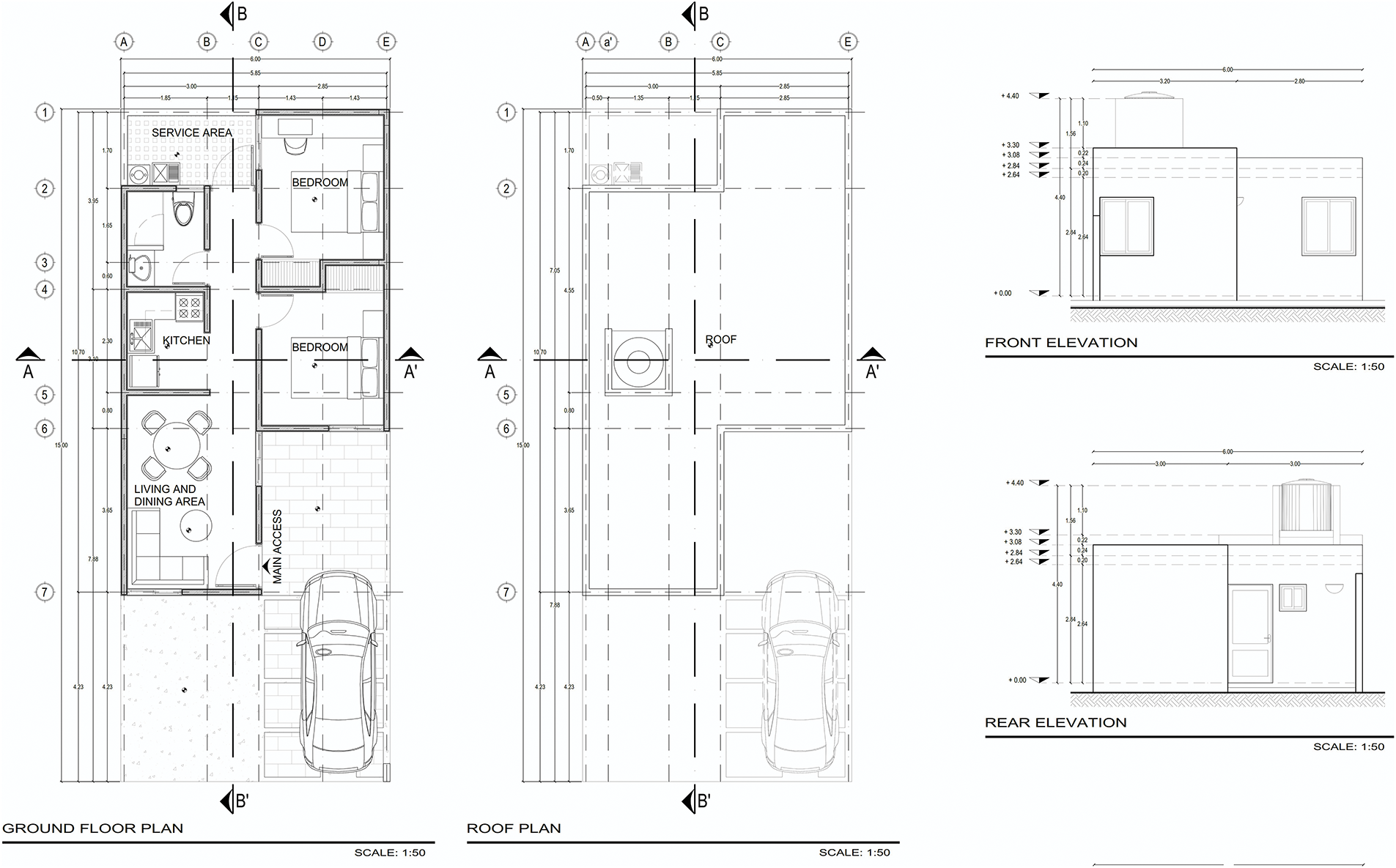

This second case focused on the methodological reproduction of the study conducted by Yu et al. (2015) [32], whose objective was to evaluate the impact of the thermal performance of the envelope—walls, roofs and windows—on the energy consumption of a rural house in Shenyang, China. To this end, the original study used DesignBuilder software for architectural modeling and EnergyPlus as an energy simulation engine, evaluating multiple scenarios with different values of overall heat transfer coefficient (U). The results showed that improving the thermal insulation of the building envelope generates a significant reduction in energy consumption, with walls being the building element with the greatest influence on energy efficiency. The study also validated the ability of EnergyPlus to accurately model variations in the thermal transmittance of different building elements, showing that the reduction of the U coefficient in walls, roofs and windows contributes substantially to the overall energy performance of the building. The reproduction of the study was particularly useful to understand the interaction between the modeling in DesignBuilder and the simulation in EnergyPlus, as well as to identify the most relevant thermal variables in the envelope design, key competencies for the subsequent analysis of the Trombe wall in low-income housing.

Table 11 summarizes the steps followed to solve Case Study 2. This exercise strengthened the understanding of the modeling of thermally efficient building systems and consolidated a useful methodological framework for the application of EnergyPlus in housing projects with a focus on thermal sustainability. This analysis served not only to evaluate the software, but also to establish a thermal evaluation protocol that will be replicated in the following cases.

3.4 Case Study #3—Simulation of a Low-Income Housing Unit without TW (Base Model without Passive Intervention)

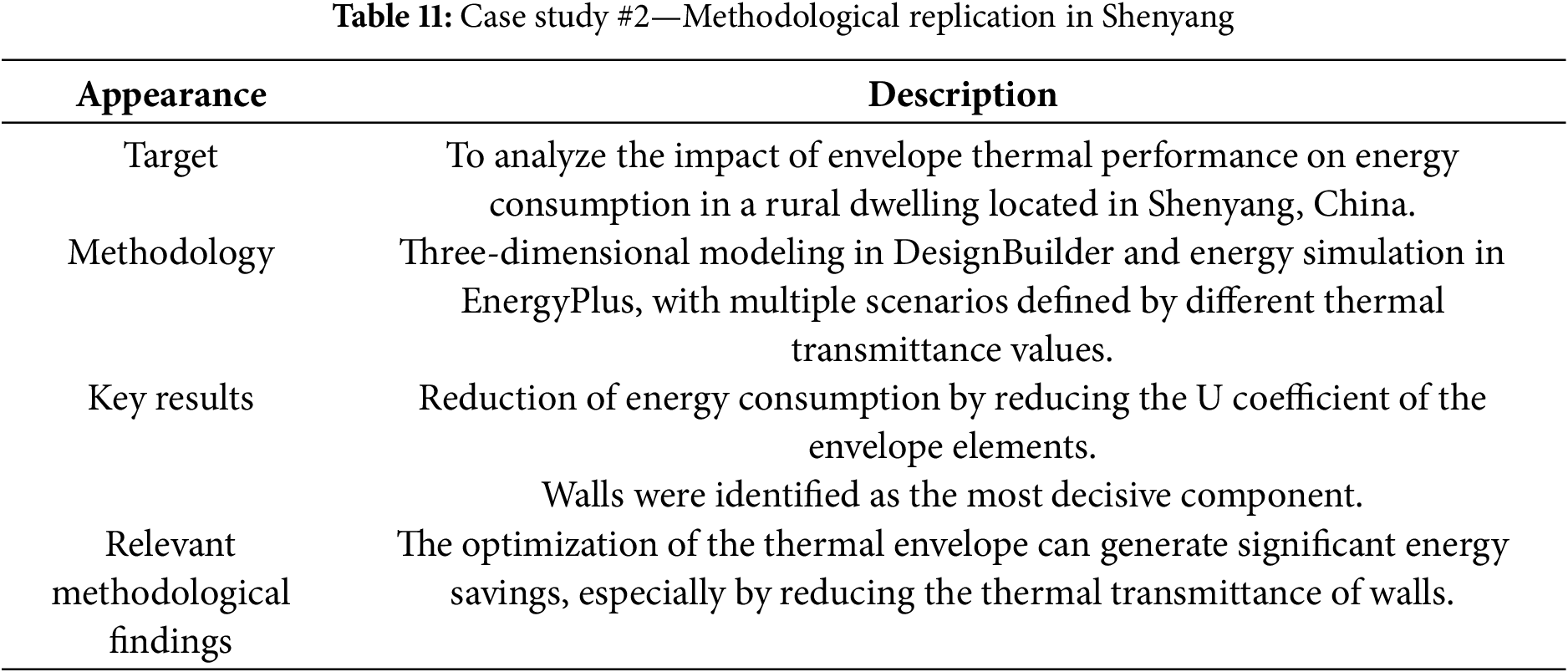

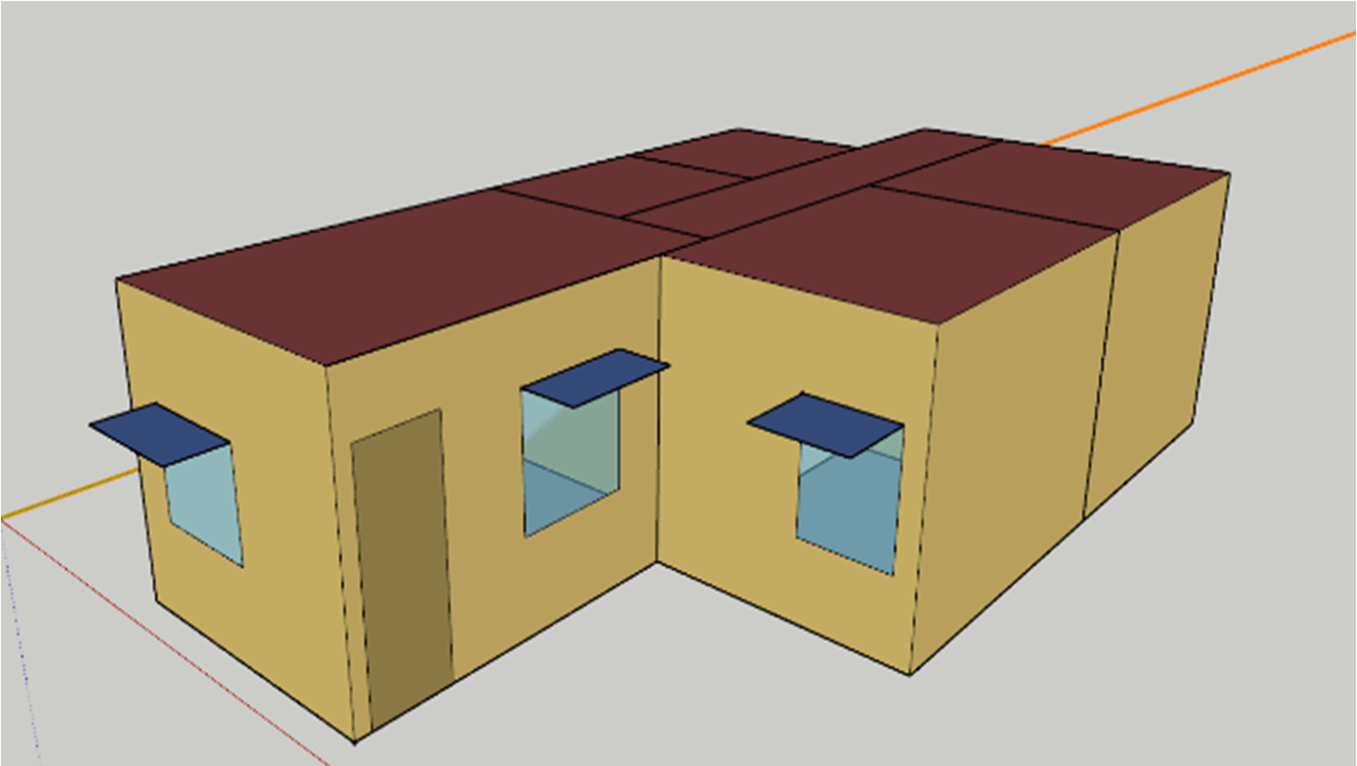

As part of the learning and validation process in the use of energy simulation tools, a practical exercise was developed based on the modeling of a social housing without the incorporation of passive conditioning strategies [33]. The purpose of this case study was twofold: on the one hand, to familiarize the researcher with the operating logic of the EnergyPlus software and, on the other hand, to establish a comparative baseline on the natural thermal behavior of a typical building in the absence of bioclimatic solutions, such as the Trombe wall. The simulation allows us to analyze the resulting interior conditions only because of the conventional thermal envelope and the local climate, which is essential to subsequently evaluate the impact of passive interventions. The modeled housing was selected from the public catalog of the Decide y Construye platform, developed by the Ministry of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development (SEDATU), ensuring architectural representativeness with respect to the existing housing stock in Mexico. The model was implemented three-dimensionally in SketchUp and OpenStudio, considering seven independent thermal zones, without active air conditioning systems. The energy simulation was run with the representative climate file TMYx (2009–2023) for Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo, characterized by a temperate-dry climate, with high solar irradiance and cold winter nights.

Note: The architectural plans used in this study were taken from the Decide y Construye platform, a Mexican Government initiative developed by the Ministry of Agrarian, Territorial and Urban Development (SEDATU). This portal provides a free catalog of housing prototypes intended to support the assisted self-production of decent and safe housing in the country.

Fig. 10 represents the architectural plan of modeled social housing. The ground floor is shown, revealing the living spaces. The figures on the left show front and rear views of the dwelling. The thermal assessment of the dwelling was determined without the use of a passive element. This case study was conducted to analyze the thermal behavior of the dwelling without any modifications.

Figure 10: Original architectural plan of social housing. Source: Plataforma Decide y Construye - Secretaría de Desarrollo Agrario, Territorial y Urbano (SEDATU), Government of Mexico

The architectural model was developed in SketchUp, Fig. 11, with the definition of thermal zones in OpenStudio. In total, seven independent zones were modeled, considering minimum natural ventilation (0.25 ACH) and without the inclusion of active air conditioning systems [34]. The thermal and energy analysis was performed using the TMYx climate file (2009–2023), representative of the typical conditions of the study site. The choice of this typology responds to its wide implementation in urban contexts of the country, which ensures the relevance and applicability of the results. Likewise, the semi-arid temperate climate of Pachuca—characterized by a high altitude (2426 m a.s.l.), average annual temperatures between 12°C and 18°C and cold nights during the winter—evidences the need for passive heat gain strategies. This base model represents the starting point to contrast the thermal behavior of the house before and after the integration of the Trombe system in subsequent scenarios.

Figure 11: Own elaboration of the geometry in SketchUp and OpenStudio of a social housing

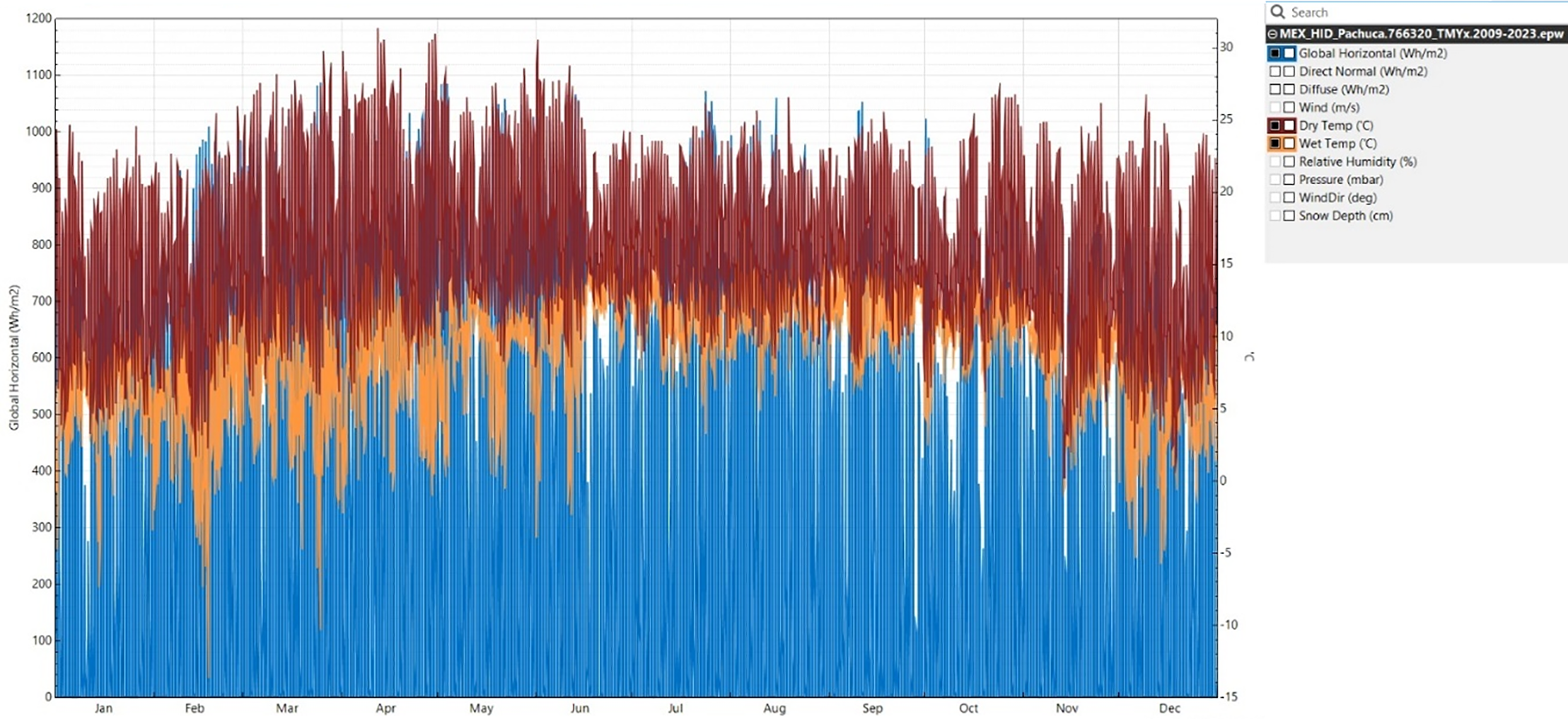

Climate analysis from TMYx file (2009–2023). In order to evaluate the potential application of passive solar strategies such as the Trombe wall, it is essential to understand the climatic conditions of the study site. The Fig. 12 shows the hourly evolution of key climate variables in Pachuca de Soto over a typical year, using data from the TMYx climate archive (2009–2023). Horizontal global radiation (blue line), normal direct radiation (orange), diffuse radiation (gray), and air temperature (red line) are plotted in this graph. The data reveal a high availability of solar radiation, with values exceeding 1000 W/m² on multiple occasions, especially between March and September. Air temperatures oscillate seasonally: minimums are recorded during the winter (below 10°C), while summer maximum reaches between 20°C and 25°C. This climatic pattern—characterized by high solar irradiance and cold temperatures in winter—confirms the viability of the Trombe wall as a passive solution to improve thermal comfort in low-income housing located in this region.

Figure 12: Solar radiation and air temperature in Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo (TMYx file 2009–2023)

The following relevant trends have been identified: Global solar radiation (blue bars) shows high values throughout the year, with greater intensity between March and June, where it exceeds 900 W/m². This high irradiance favors the viability of passive solar strategies such as the Trombe wall. Direct and diffuse radiation (orange and light blue) means direct radiation is dominant in the dry and clear season, while the diffuse component increases during the cloudy months (June–September), corresponding to the rainy season. Air temperature (brown line) reveals a marked seasonal variation, with winter minimum temperatures (December–January) below 10°C, and maximum temperatures around May–June close to 25°C. This thermal amplitude reinforces the need for strategies to mitigate interior thermal changes. This analysis supports the use of passive solutions such as TW, particularly in climates with high solar radiation and cold night temperatures such as Pachuca de Soto.

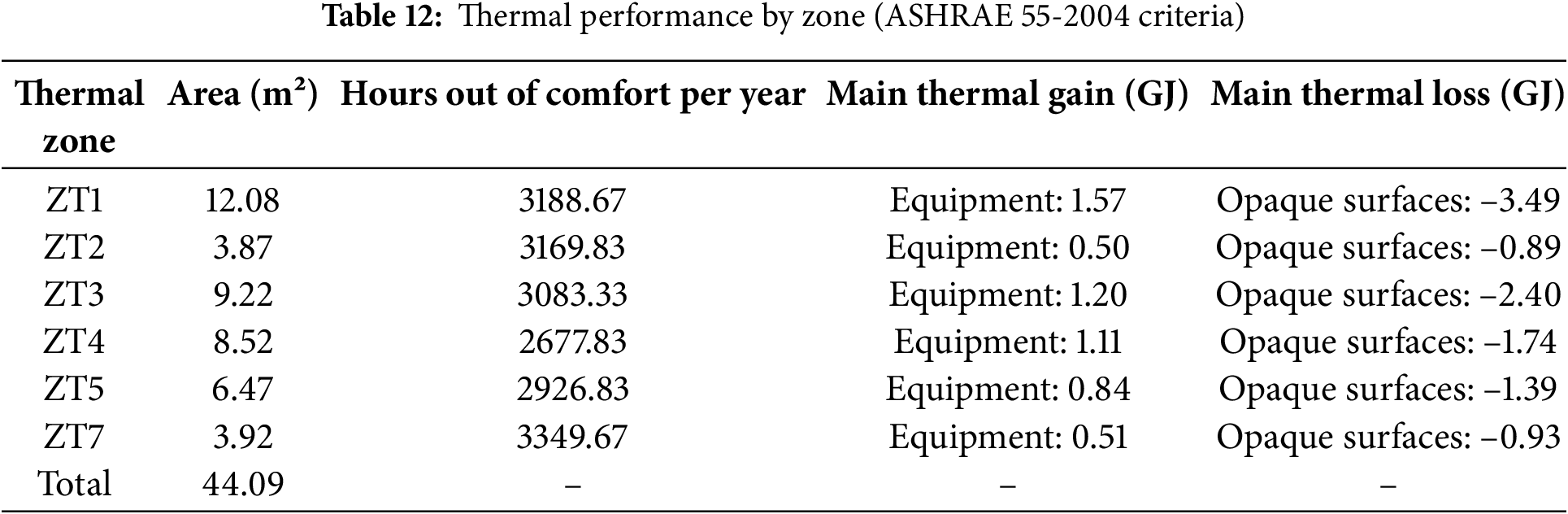

Simulation results. Thermal evaluation of the base model without passive strategies.

The Table 12 presents the most relevant results of the thermal performance of each zone in the simulated social housing without passive intervention [35]. Three key dimensions are identified: 1. Thermal comfort conditions: Annual hours out of thermal comfort, evaluated under ASHRAE 55-2004 criteria, exceed 3000 h in most zones, indicating poor performance. Thermal zone ZT7 presents the worst performance, with 3349.67 h out of comfort ranges, while ZT4, although slightly better, still exceeds 2600 h. 2. Internal thermal gains: In all zones, the main source of heat comes from the use of electrical equipment. However, these gains are limited: for example, ZT1, with the largest area, presents a thermal gain of 1.57 GJ per year per equipment, insufficient to compensate for the thermal losses recorded. 3. Thermal losses through the envelope: Opaque surfaces, such as walls and ceilings, represent the main source of energy loss. In all cases, thermal losses far exceed internal gains. In ZT1, for example, 3.49 GJ are lost annually through these surfaces, which doubles the internal gain of the zone. Overall, the results show a negative thermal balance: more heat is lost than is gained, resulting in inadequate indoor temperatures and a high number of hours out of comfort. This situation justifies the need to incorporate passive strategies such as the Trombe wall, in order to improve the thermal efficiency of the envelope and reduce the thermal loads of the building.

3.5 Case Study #4—Simulation of a New Affordable Housing Proposal with and without TW (Convective and Non-Convective)

The fourth study is proposed as the stage of integral validation of the hypotheses H1-H4 established in this section. A complete social housing is now addressed, both in its original configuration and with the incorporation of TW with two operational variants:

1. Non-convective TW: the chamber remains sealed; only solar gain and thermal inertia are evaluated.

2. Convective TW: the lower and upper dampers are enabled according to the operating schedules derived from H1-H4, allowing the air-mass exchange foreseen by the stack effect.

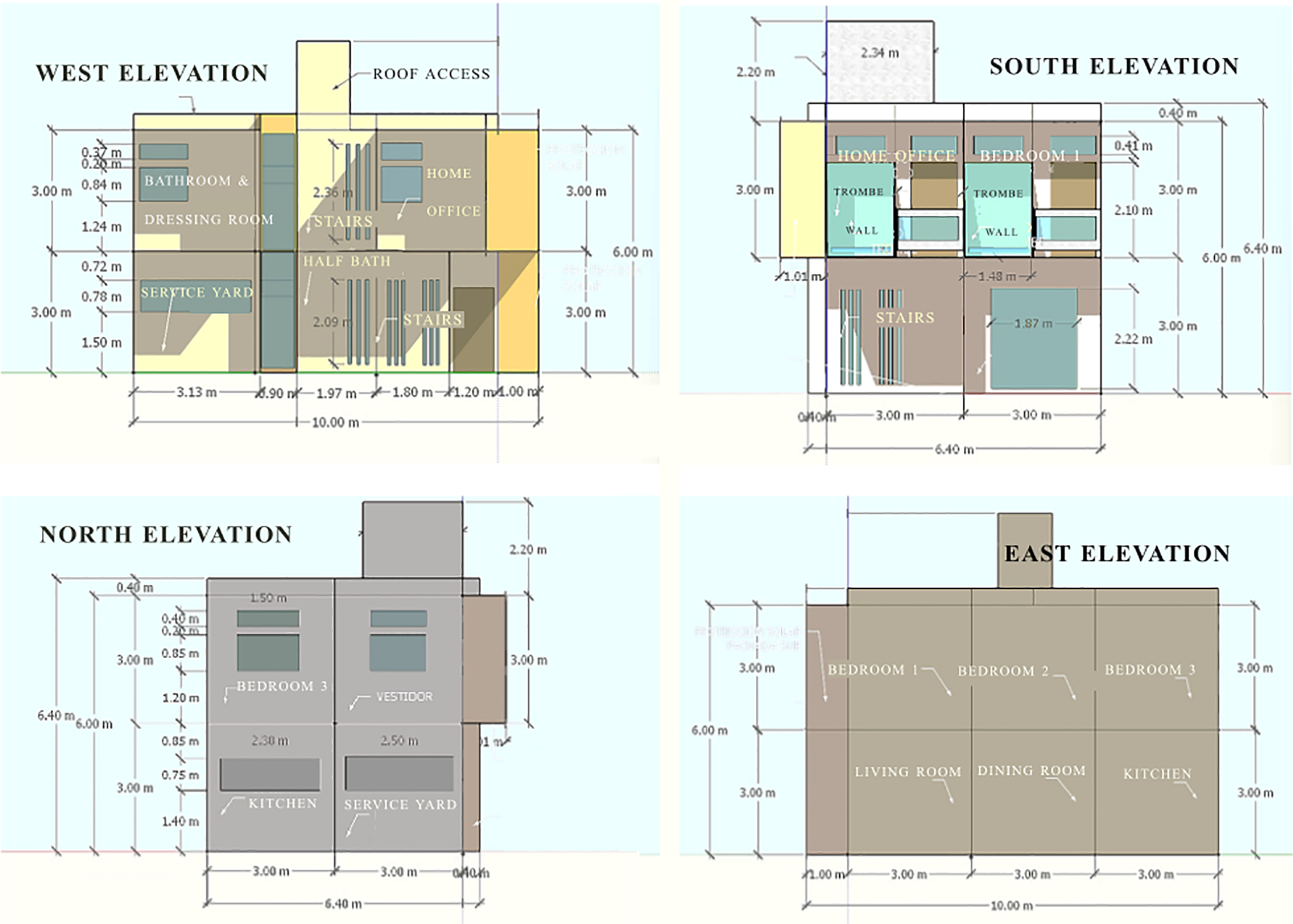

The design presented in Figs. 13 and 14 represents the architectural design of a home where the architectural design methodology was considered, following these steps: analysis of the site and the client’s needs, conceptualization of the design, a needs program, and development of the preliminary design project. The main objective is to quantify the net thermal improvement provided by the system under real climatic conditions of Pachuca de Soto and, simultaneously, to contrast each hypothesis by means of measurable indicators: convective flow, operating temperature and comfort hours (20°C–24°C, ASHRAE 55-2010).

Figure 13: Overview of the case study: space distribution and Trombe system. Geometry in OpenStudio.

Figure 14: Main facades of the house with integration of the Trombe system and passive solar control strategies. Dimensions are in meters

Three scenarios are compared for this purpose: Base model (without TW), Model with non-convective TW and Model with convective TW. The annual simulation in EnergyPlus allows us to analyze the indoor temperature per zone, the daily thermal amplitude and the number of hours in comfort. In addition, the inclusion of key spaces—south rooms and west bathroom on the upper floor, living-dining room and kitchen on the first floor—makes it possible to evaluate the spatial distribution of benefits, verifying the influence of solar orientation and the convective regime of the TW. The following sections present: the geometric and control configuration used in each scenario, hourly and annual thermal results, and discussion of how these results confirm or refute hypotheses H1–H4. This closes the methodological sequence and establishes a solid basis for recommending the adoption of the TM in social housing programs in temperate-sub-humid climates.

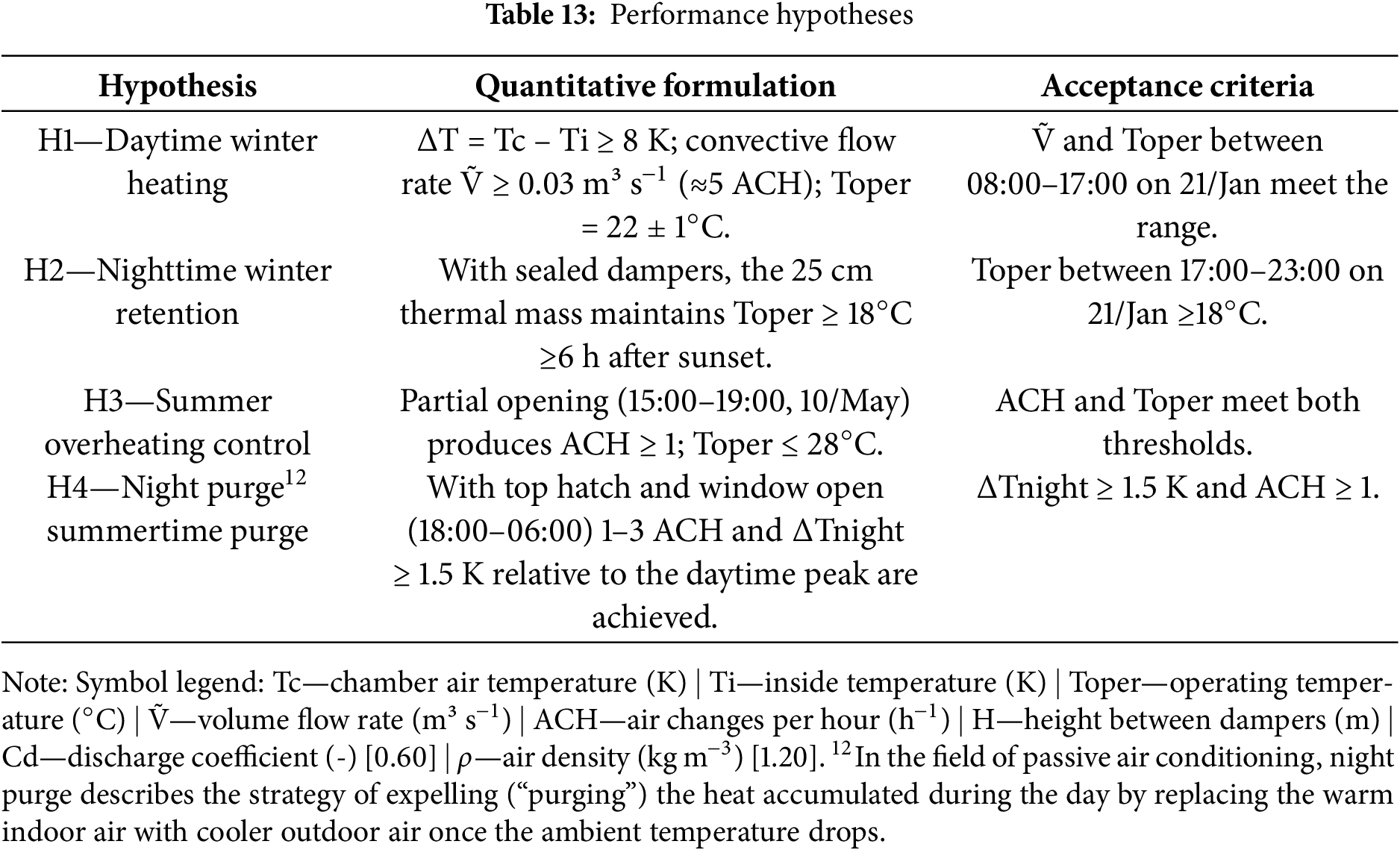

This study formulates and applies the following thermo-energetic performance hypotheses for the TW, which constitute the methodological backbone of the research. First, they establish quantifiable objectives, transforming concepts such as solar gain or stack effect into thresholds that EnergyPlus can calculate directly (e.g., air renewal rate -ACH-, operating temperature, annual percentage of hours in comfort). Secondly, they delimit the analytical scope; by setting, for example, that success implies keeping the nighttime operating temperature (T_oper) above 18°C, any ad hoc interpretation of the results is prevented. Thirdly, they facilitate external verification, since any researcher can reproduce the case by applying the same indicators and boundary conditions. Finally, they guide the design process: when the simulation does not satisfy a particular hypothesis, it immediately identifies which parameter—glazing area, damper schedule, thermal mass, etc.—should be optimized. In summary, the hypotheses convert passive climate principles into operational goals, provide rigor to the numerical contrast and guarantee the reproducibility of the study.

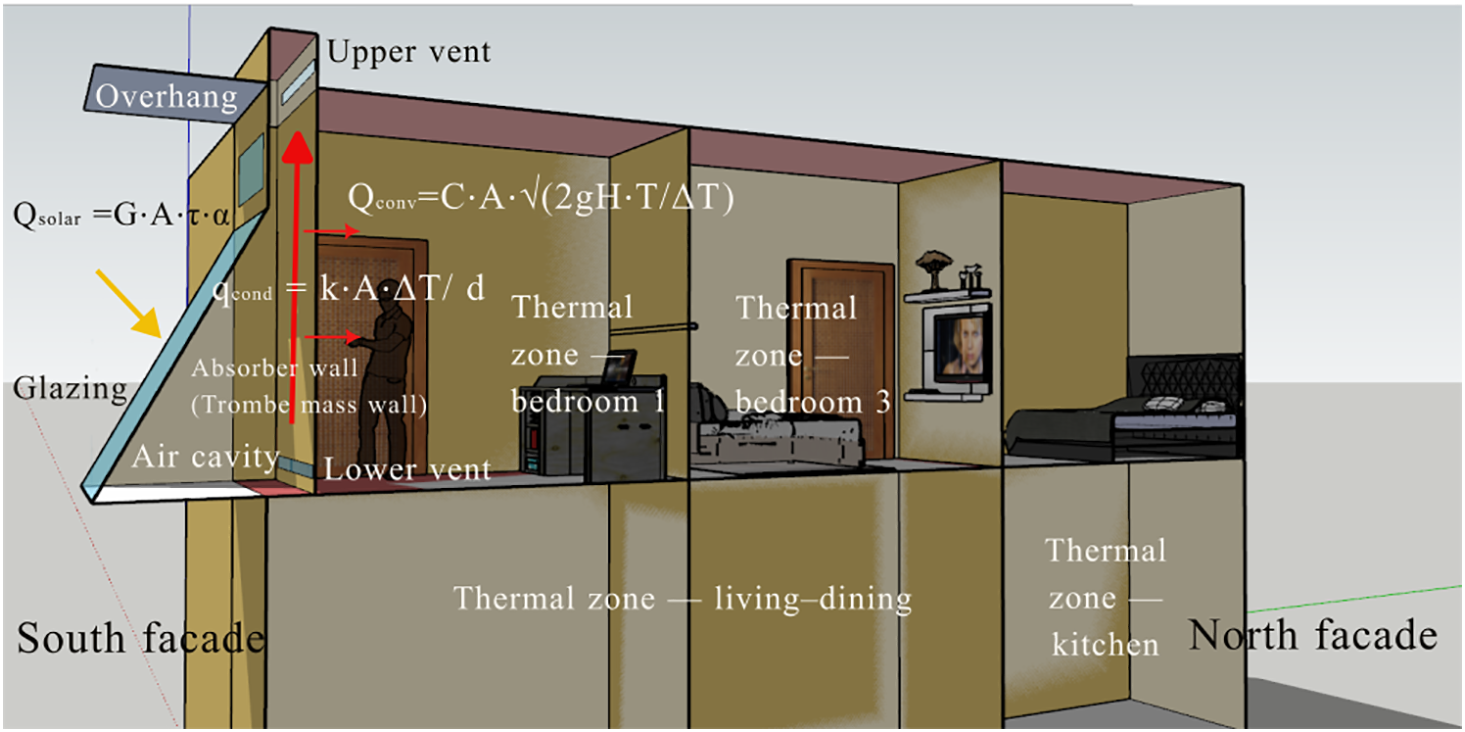

The Fig. 15 shows a cross section of the house towards the south and north facades, highlighting the thermal behavior of the convective Trombe wall. The system is composed of an air gap between an inclined glass and a collector wall [36]. The incident solar radiation Qsol = G – A – τ – α is absorbed by the wall, generating a thermal gradient that promotes heat transfer by conduction (qcond = k – A – ΔT/d) and natural convection of the air in the chamber (Qconv = C – A – √(2gH – ΔT/T)).

Figure 15: Schematic diagram of the thermal performance of the convective Trombe wall on the south façade

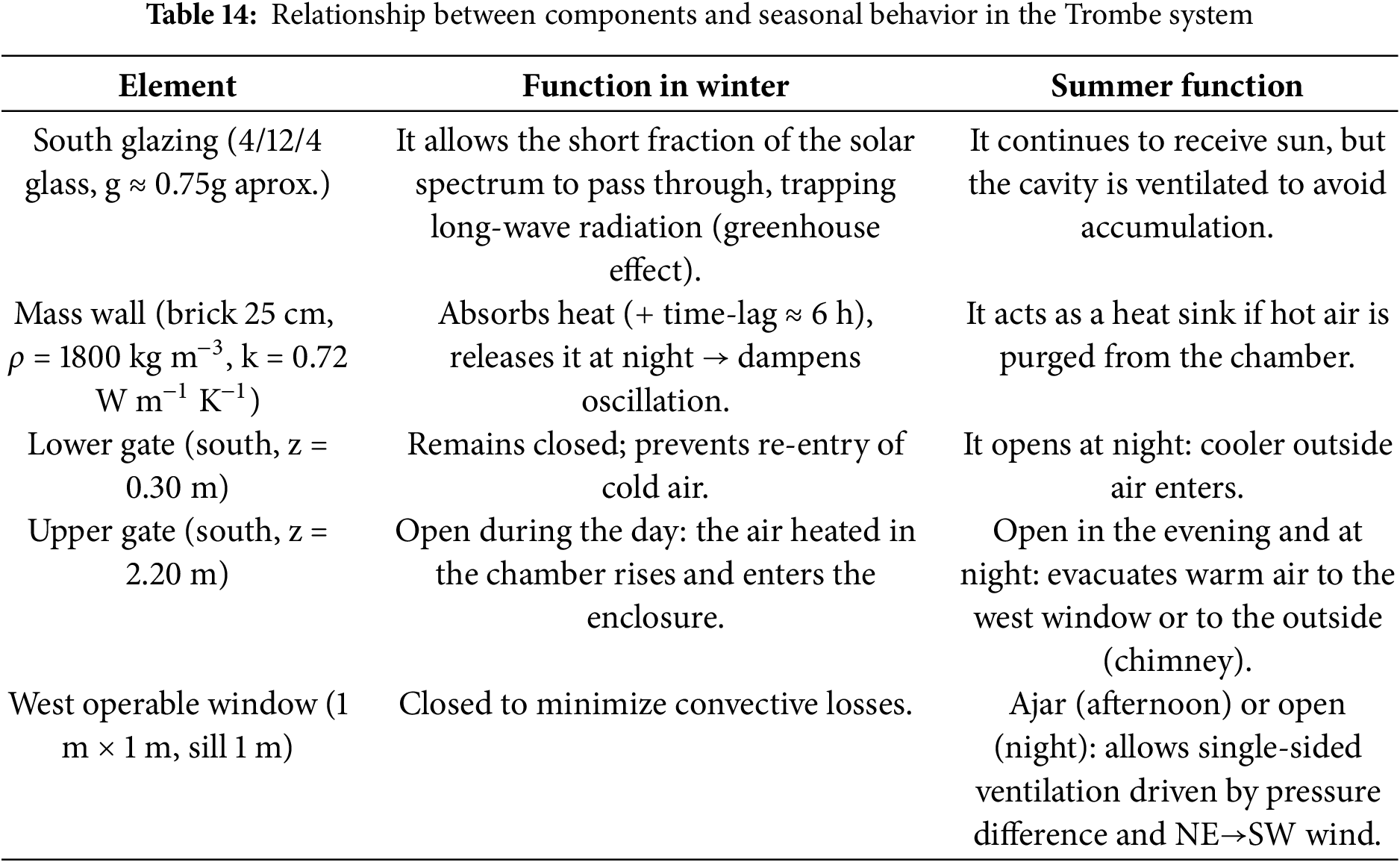

The lower and upper vents allow the exchange of warm air with the interior thermal zones, in this case the living-dining room (ground floor) and bedroom 1 (upper floor). Eaves are included to limit solar gain in summer and maintain passive solar control in winter. The lower and upper vents allow the exchange of warm air with the interior thermal zones, in this case the living-dining room (ground floor) and bedroom 1 (upper floor). Eaves are included to limit solar gain in summer and maintain passive solar control in winter. The TW is a bioclimatic solution that takes advantage of solar radiation to heat the interior of a house. However, its design can limit the direct entry of fresh air. Therefore, it is essential to complement this system with strategically placed windows that facilitate natural ventilation. Although the TW is designed primarily for solar gain, it is possible to integrate windows into its design (Fig. 16). These should be carefully located and sized so as not to compromise the thermal efficiency of the wall. It is recommended to use double-glazed windows and consider shading elements to control solar gain in summer [36].

Figure 16: Solar interaction, thermal mass and air flow in the Trombe-stack system for passive room air conditioning

On the other hand, Controlled Ventilation incorporating louvers or dampers at the top and bottom of the TW allows the circulation of hot air into the interior during the winter and its expulsion in summer, thus improving ventilation and thermal comfort.

Cross Ventilation Windows: Installing operable windows on the west façade facilitates cross ventilation (Fig. 16), allowing cool air to enter and warm air to escape, especially during the afternoon. This is crucial in climates such as Pachuca de Soto, where the predominant winds come from the northeast.

Solar Protection: Since the west façade receives intense solar radiation during the afternoon, it is important to equip the windows with shading elements, such as blinds or eaves, to avoid overheating in summer.

General Considerations

• Window Height: Placing the air inlet windows at a low height and the outlet windows at a high height favors the chimney effect, improving air circulation.

• Interior Obstacles: Avoid placing furniture or partitions that obstruct the flow of air between the inlet and outlet windows.

• Shading Elements: Incorporating eaves or louvers on windows helps to control solar gain, maintaining interior thermal comfort.

Implementing these strategies will allow you to take full advantage of the benefits of TW and ensure adequate ventilation in your room, adapting to the climatic conditions of Pachuca de Soto.

Based on the principles of solar gain, thermal storage and natural convection, the performance hypotheses H1–H4, considered as extreme cases (Table 13) are formulated for the social housing analyzed a 3 m × 3 m × 3 m south-facing typical enclosure, equipped with a convective TW and an operable window on the west façade-. These assumptions constitute the starting point to quantify, by simulation, the passive contribution of the system to the operative temperature and indoor air renewal.

Equations governing natural ventilation by buoyancy effect in a TW:

Buoyancy pressure difference. The driving pressure due to the stack effect is estimated as:

ρ: air density evaluated at mean temperature Tm (kg m−3).

g: gravitational acceleration (9.81 m s−2).

H: effective height between the lower and upper mouth of the channel (m).

Tc: temperature of the hot air in the cavity (K).

Ti: indoor air temperature (K).

Tm: mean temperature (Tc + Ti)/2 (K).

The form comes from the hydrostatic equation ΔP=gH(ρi − ρc) and the linear relationship of ρ∝ 1/T. The term (Tc – Ti)/Tm reflects that the buoyancy force is proportional to the relative temperature gradient and decreases as the air becomes less dense.

Specific application to TW

• H is the distance from the bottom grille (room inlet) to the top grille of the air chamber. Typical values: 2.5–3.5 m in a single-family house.

• Tc is measured at the top of the carcass; it may exceed 50°C on sunny days.

• Cd depends on the type of gate (circular opening ≈ 0.63; slotted slit ≈ 0.55).

• To avoid summer overheating, external louvers are added, or the upper dampers are closed by overriding ΔP

Physical-thermodynamic explanation of the TW system + chimney + windows on south and west facades (north hemisphere orientation, temperate-sub-humid climate: Pachuca de Soto).

The following Table 14 summarizes the thermal and functional behavior of the main components of the Trombe system in a seasonal context, distinguishing its operation in winter and summer. The specific functions fulfilled by each element are included, as well as the relevant physical variables involved in its thermal and ventilation performance. This characterization allows understanding the system’s operating logic as an adaptive passive strategy, depending on climatic conditions and indoor comfort objectives.

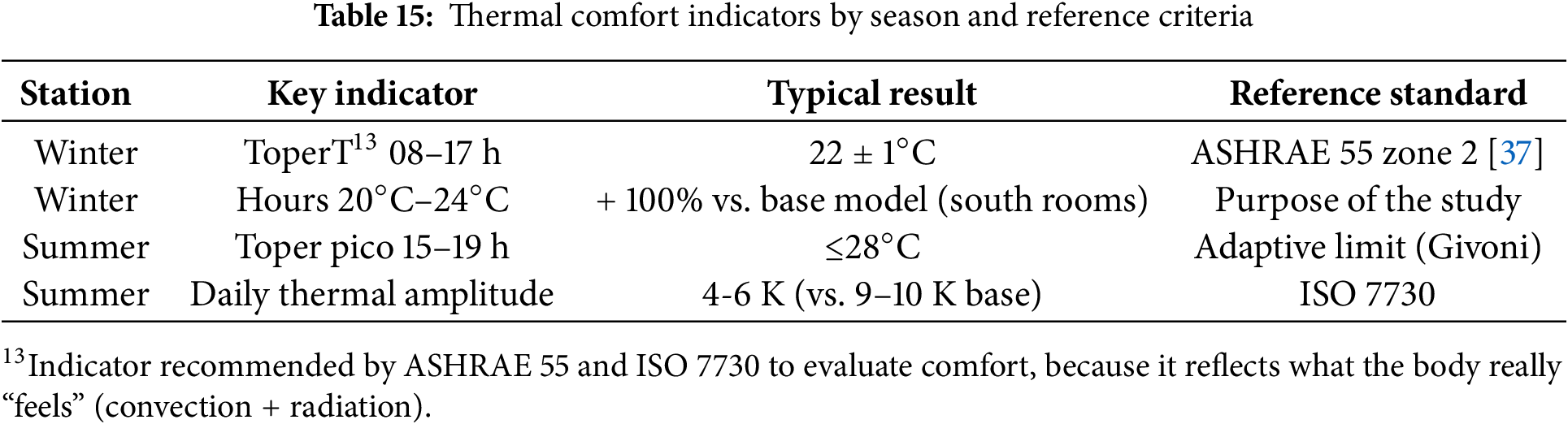

The Table 15 presents a synthesis of the main thermal performance indicators of the experimental model with TW, organized by season of the year. It includes the representative results obtained in simulation, contrasted with international thermal comfort standards (ASHRAE 55, ISO 7730) [37] and adaptive criteria (Givoni). The data allows the evaluation of the system’s ability to maintain comfortable indoor conditions, as well as its efficiency with respect to the base model in winter and summer contexts.

The combination of winter passive heating and summer single-sided ventilation allows areas equipped with TW to exceed 60%–100% of annual hours in the 20°C–24°C range, while areas without TW barely reach 20%–30%.

In the absence of an opposing opening, summer air renewal relies on so-called single-sided ventilation, a mechanism extensively documented in CIBSE AM10 (CIBSE, 2005) and ASHRAE Handbook—Fundamentals (2021). The flow results from the combination of pressure fluctuations and wind turbulence over the west window and a height difference between the inlet and outlet points located on the same façade.

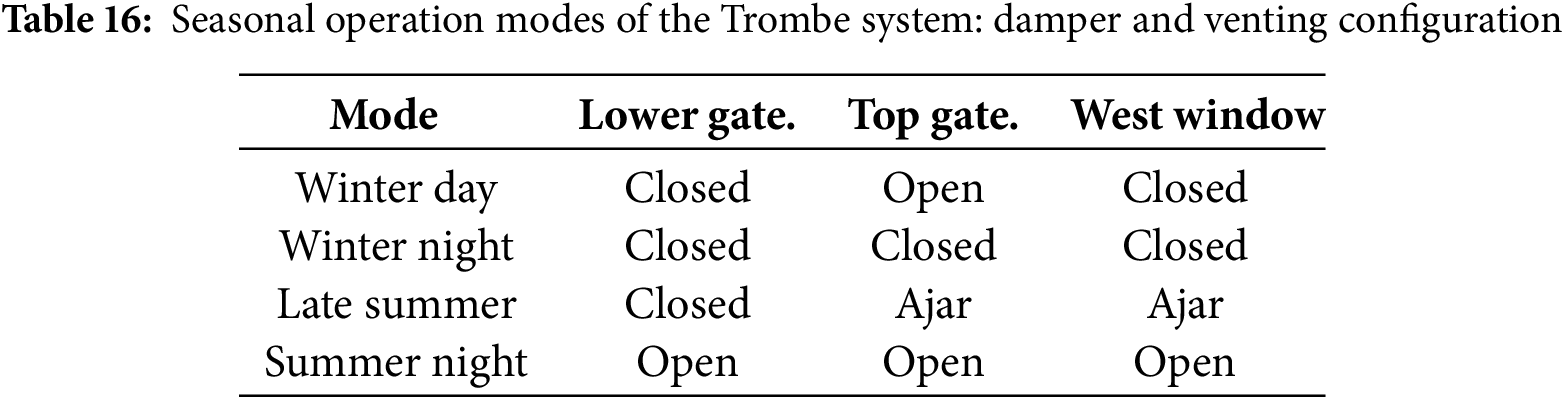

The Table 16 details the operating logic of the Trombe system in different periods of the year, specifying the status of the dampers (lower and upper) and the west window. This dynamic configuration allows regulation of the airflow according to the available solar gain and the indoor comfort needs, favoring heat accumulation in winter and cross ventilation or thermal purge in summer. The strategy is based on passive controlled ventilation principles and responds to the time scheduling of the system.

This sequence explains how a single exterior-sealed TW can provide thermal comfort without classic cross ventilation, combining:

• Solar gain + thermal mass for winter.

• Chimney effect + single facade ventilation for summer.

Finally, the implementation of the TW was simulated in the same house as in the previous case, evaluating two variants (convective and non-convective). This analysis allowed quantifying the thermal improvements achieved and demonstrating the effectiveness of the system under real conditions. This section presents the results obtained from the energy simulation of social housing, comparing the thermal behavior between the base model (without TW) and the experimental model (with TW in selected zones). The indoor temperature per thermal zone, the daily thermal amplitude and the number of hours within the comfort range established between 20°C and 24°C according to the ASHRAE 55-2010 standard were analyzed.

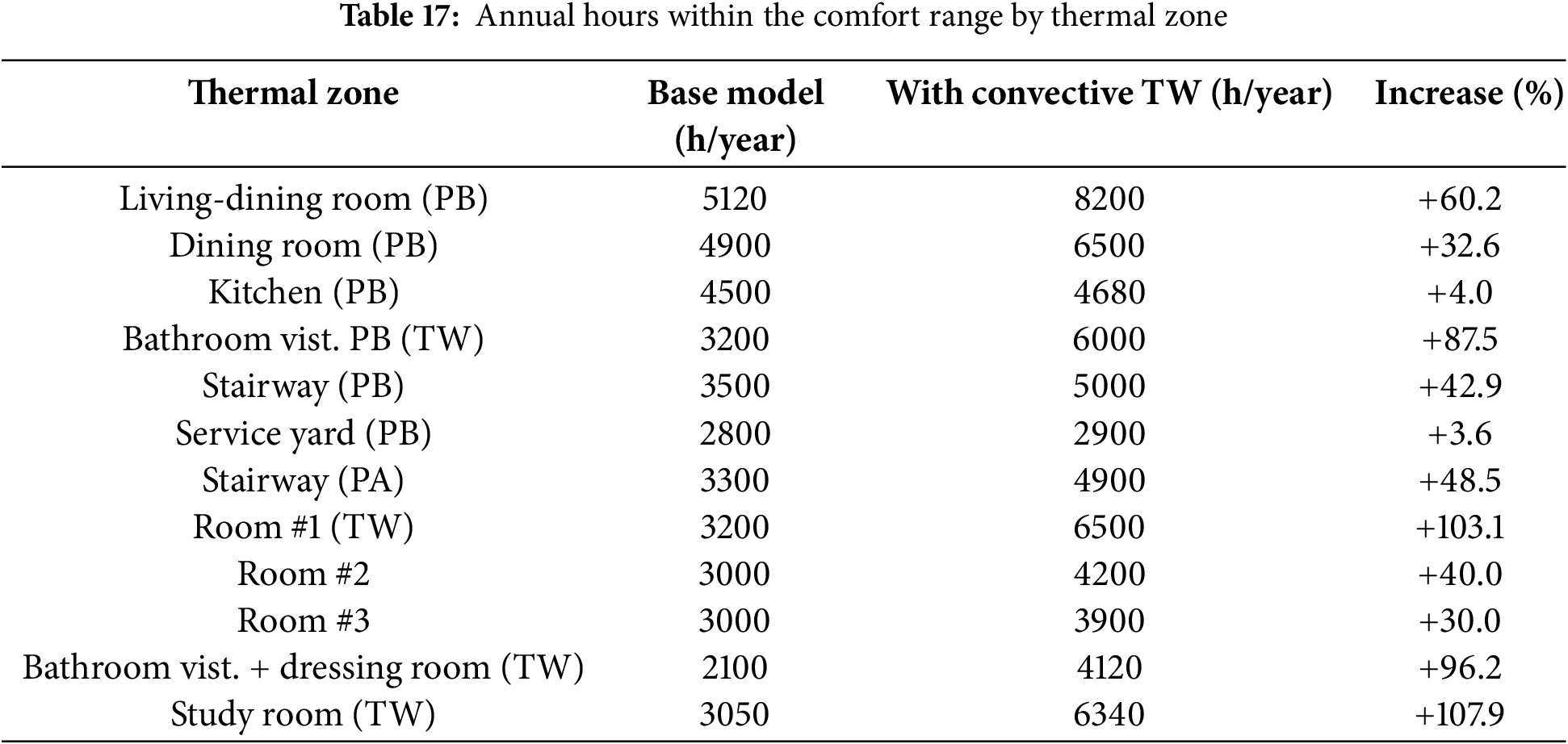

The analysis focused on the thermal zones equipped with TW (south bedrooms and west bathroom upstairs) and the main social areas (living-dining room and kitchen on the first floor). The following table summarizes the total number of annual hours within the comfort range for each zone, and compares the results obtained between the two models.

As can be seen, the areas equipped with TW showed a considerable increase in the number of hours of thermal comfort, especially in the south-facing rooms. The west-facing bathroom also presented relevant improvements, which confirm the effectiveness of the Trombe system in the climatic context of Pachuca de Soto, particularly during the winter. In order to structure and verify the information needed for the detailed thermal analysis of the simulated model, a matrix was developed that identifies the key technical outputs, their availability, expected source and the degree of processing required. This verification makes it possible to anticipate which variables need to be extracted or calculated from the output files generated by EnergyPlus, as well as to determine possible information gaps. Finally, the implementation of the TW was simulated in the same house as in the previous case, evaluating two variants (convective and non-convective). This analysis allowed quantifying the thermal improvements achieved and demonstrating the effectiveness of the system under real conditions.

The analysis focused on the thermal zones equipped with TW (south bedrooms and west bathroom upstairs) and the main social areas (living-dining room and kitchen on the first floor). The following table summarizes the total number of annual hours within the comfort range for each zone, and compares the results obtained between the two models.

Table 17 presents the annual hours within the thermal comfort range for each thermal zone of the house, comparing the base model (without TW) with the scenario that includes convective TW. The results show that the zones with TW present significant increases in comfort hours, especially in those with south and west orientation. The dressing room and study room are the spaces that benefit the most, with increases of more than 95%. On the contrary, areas with north orientation or without useful windows experience marginal improvements. This distribution confirms the positive impact of the TW on passive thermal performance, depending on its location and coupling to the interior.

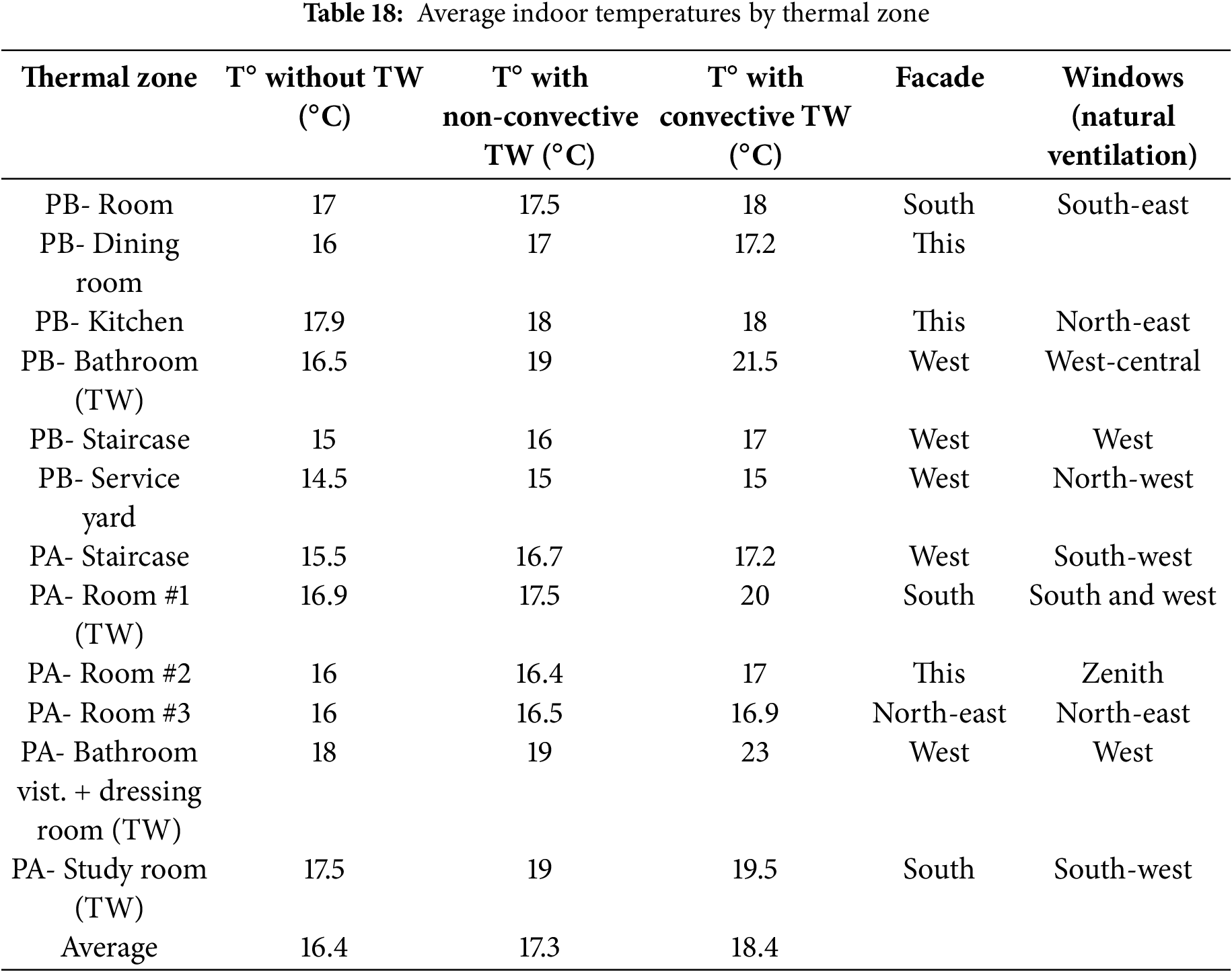

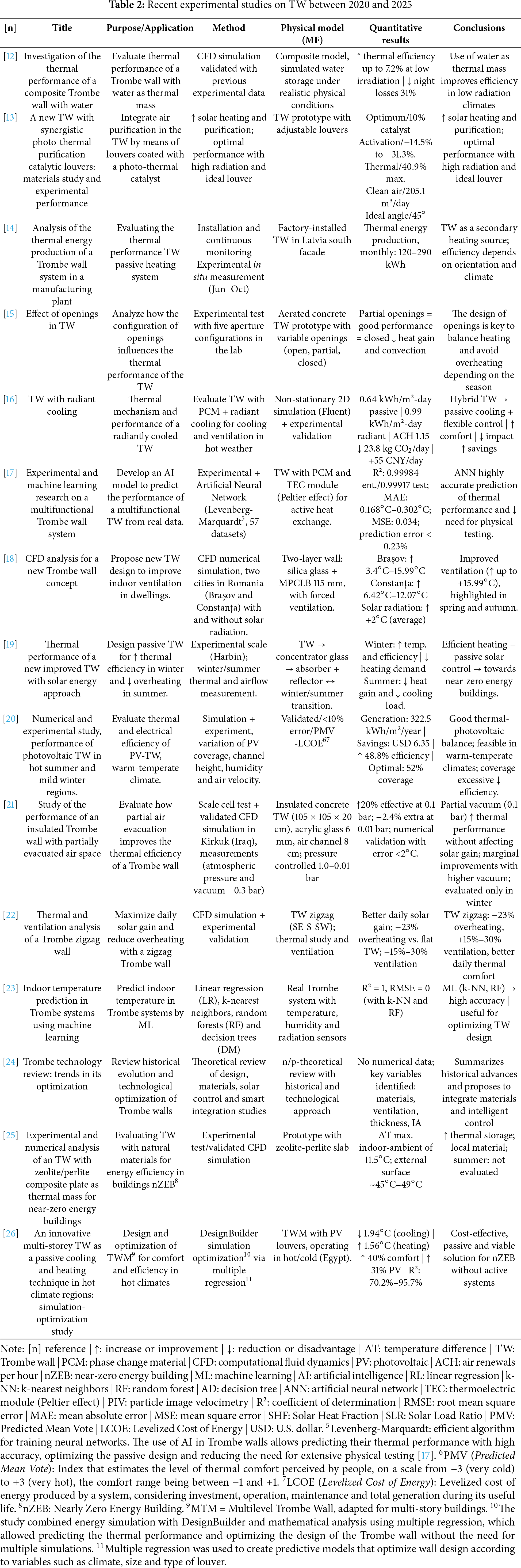

The Table 18 presents the thermal effect of three configurations (without TW, with non-convective TW and with convective TW) on twelve thermal zones of a bioclimatic house. An average increase of 2°C is observed in zones with convective TW compared to the scenario without TW. The thermal behavior is conditioned by solar orientation, glazed surface and type of natural ventilation. The highest thermal gains are recorded in the upstairs dressing room bathroom (+5°C) and the study room (+2°C).

The Fig. 17 shows the comparison of average indoor temperatures in twelve thermal zones of the house, under three configurations: without Trombe wall, with non-convective Trombe wall, and with convective Trombe wall (simulated in EnergyPlus). The areas with convective Trombe wall show significant thermal increases, especially the dressing room (+5°C) and the study room (+2°C). The improvements are greater in south and west facing zones, which supports the effectiveness of the Trombe system in improving passive thermal comfort in temperate-dry climates.

Figure 17: Comparison of indoor temperatures by thermal zone

The methodological progression employed in the four case studies allowed establishing a solid sequence that goes from the validation of energy simulation tools to the specific thermal evaluation of a passive system adapted to the context of social housing in Mexico. This gradual strategy not only increased the reliability of the results obtained but also facilitated the identification of the architectural and operational conditions that enhanced the effectiveness of the TW wall in temperate-dry climates. The results obtained through numerical simulation showed a substantial thermal improvement in the areas equipped with convective TW. In particular, south-facing spaces -such as the main room and the study room- registered increases of more than 100% in annual hours within the thermal comfort range (18°C–24°C), reaching up to 6500 h/year under ideal passive operation conditions. In addition, average thermal gains of up to 5°C were observed in areas with adequate solar gain and thermal coupling. These findings are consistent with previous studies [38], which highlight that orientation, thermal mass and controlled ventilation are key determinants in the thermal performance of passive solutions. From the point of view of practical application, TW shows considerable potential for implementation in urban low-income housing, as it offers a low-cost, low-maintenance solution with high architectural compatibility. Its incorporation does not imply substantial modifications in the volumetry or in the conventional materials used, which facilitates its replicability on a large scale. Particularly, the climate of Pachuca de Soto—characterized by high solar irradiance in winter and nighttime minimums close to 5°C—provides an optimal scenario for passive systems of direct solar gain and thermal storage.

However, some limitations of the present study should be recognized. The simulations assumed ideal natural ventilation conditions (0.25 ACH) and did not consider losses due to uncontrolled infiltration, nor the effect of cross ventilation in real conditions. Likewise, the model does not consider the dynamic behavior of the users (use of curtains, thermal habits), nor the aging of materials, factors that can significantly influence the real performance of the system. For future research, it is suggested to incorporate life cycle analysis of the TW, evaluate its long-term economic impact and consider its seasonal performance in different climatic zones of the country. In addition, the combination of TW with other passive strategies—such as thermal insulation, controlled night ventilation or adaptive solar shading—could lead to more effective integrated bioclimatic solutions that respond to the growing demands for energy efficiency and comfort in the social housing sector.

Research was conducted for two housing case studies, following an architectural design methodology to develop the construction project. This housing project was thermally analyzed, and temperatures were found to be outside the thermal comfort range. A passive system known as a Trombe wall was proposed to improve the interior thermal environment and thus mitigate temperature changes. The contribution is notable in incorporating a novel architectural design with a Trombe wall, ensuring the thermal functionality of the home.

The results obtained in this study confirm the viability of TW as an effective passive strategy to improve thermal comfort in low-income housing located in temperate-sub-humid climates, such as that of Pachuca de Soto, Hidalgo. By means of dynamic energy simulations carried out with EnergyPlus, it was shown that the incorporation of the TW significantly reduces the interior thermal oscillation and improves the habitability conditions during the winter, registering an increase of 167%. It is an indicator counting the hours within the thermal comfort interval in the winter season, comparing the house with and without a TW.

The implementation of the system allowed raising the average winter indoor temperature from 14.4°C to 18.3°C without resorting to the use of mechanical heating systems, which highlights its potential to reduce energy dependence in low-income contexts. These findings are consistent with previous research in regions with similar climatic and typological characteristics [39] and reinforce the relevance of the TW as a replicable and adaptable solution within the Mexican social housing stock.

From a technical and economic perspective, the TW represents an accessible, low-cost, and high-impact alternative, whose architectural integration does not compromise the functionality of the living space. Likewise, its implementation can contribute significantly to the reduction of energy poverty and to the fulfillment of the Sustainable Development Goals, in particular SDG 7 (affordable and clean energy) and SDG 11 (sustainable cities and communities).

In this sense, future research should be oriented not only to validate the results obtained in real conditions of use but also to explore technological improvements, hybrid strategies, and regional application scenarios that broaden its applicability. The integration of optimization tools, artificial intelligence, and economic-social analysis will allow consolidating the TW as an integral passive solution within contemporary sustainable housing.

In order to strengthen the applicability, scalability, and robustness of the TM in the context of Mexican social housing, the following lines of research and development are proposed:

• Experimental validation: Construction of full-scale prototypes that allow for contrasting the results obtained by simulation with empirical data under controlled conditions of daily use.

• Materials innovation: Evaluation of the performance of the TW by incorporating phase change materials (PCM), natural insulation, or other bio-inspired solutions that improve its seasonal thermal behavior.

These proposals provide a solid foundation for future research in the fields of energy efficiency, bioclimatic architecture, and resilient social housing, contributing to the advancement towards more sustainable, adaptive, and equitable living environments.

Acknowledgement: We would like to extend our special thanks to SECIHTI (Secretariat of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation) for awarding Yamila C. Rodriguez Gómez a grant to develop the research project related to this study. We would also like to thank TecNM-Campus Pachuca for its support in financing the publication costs.

Funding Statement: The authors did not receive any funding for the development of the research.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: J. Serrano-Arellano, Y.C. Rodríguez Gómez; data collection: F.N. Demesa-López, J.F. Ituna-Yudonago, Y.C. Rodríguez Gómez; analysis and interpretation of results: J. Serrano-Arellano, J.M. Belman-Flores; draft manuscript preparation: Y.C. Rodríguez Gómez, J. Serrano-Arellano. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [J. Serrano-Arellano], upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature and Abbreviation

| Symbol | Description Units |

| q | Heat flux W/m² |

| k | Thermal conductivity W/m·K |

| cp | Specific heat capacity J/kg·K |

| T | Temperature °C or K |

| ∇T | Temperature gradient K/m or dimensionless |

| ε | Emissivity (or porosity, depending on context) – |

| τ | Glass transmissivity – |

| ρ | Density kg/m³ |

| V | Volume m³ |

| m | Mass kg |

| Mass flow rate kg/s | |

| H | Height of the storage wall m |

| D | Thickness or diameter m |

| Qs | Stored thermal energy J |

| η | Thermal efficiency % |

| Tavg, Tmin, Tmax | Average, minimum, and maximum temperature °C or K |

| Acronyms and Technical Abbreviations | |

| Acronym | Meaning |

| TW | Trombe Wall |

| CFD | Computational Fluid Dynamics |

| HVAC | Heating, Ventilation, and Air Conditioning |

| PCM | Phase Change Material |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| nZEB | Nearly Zero Energy Building |

| DOE | Department of Energy (United States) |

| TMYx | Typical Meteorological Year (extended) climate file |

| ASHRAE | American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers |

| EPS | Expanded Polystyrene (if aparece en la parte constructiva) |

| ACH | Air Changes per Hour (ventilation rate indicator) |

| INEGI | National Institute of Statistics and Geography |

References

1. Pennacchia E, Gugliermetti L, Di Matteo U, Cumo F. New millennium construction sites: an integrated methodology for the sustainability assessment. VITRUVIO. 2023 Dec 21;8(2):102–15. doi:10.4995/vitruvio-ijats.2023.20532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Passive House Institute (PHI); 2024 [2025 Sep 18]. Available from: https://passiv.de/en/index.html. [Google Scholar]

3. Ecohabitat. World’s first Passive House in Kranichstein, Germany; 2019 Jan 22 [2025 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.ecohabitat.gr/worlds-first-passive-house-in-kranichstein-germany/. [Google Scholar]

4. Abbas EF, Al-abady A, Raja V, AL-bonsrulah HAZ, Al-Bahrani M. Effect of air gap depth on Trombe wall system using computational fluid dynamics. Int J Low-Carbon Technol. 2022;17:941–9. doi:10.1093/ijlct/ctac063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Moosavi L, Alidoost S, Norouzi F, Sattary S, Banihashemi S. Trombe wall’s thermal and energy performance—a retrofitting approach for residential buildings in arid climate of Yazd. Iran J Renew Sustain Energy. 2022;14:045101. doi:10.1063/5.0089098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou Y, Zhu J, Zhang Y, Zhou X, Sun X. Structure and regional optimization of a phase change material Trombe wall system. Energy. 2024 Oct;305:132273. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2024.132273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Dhahri M, Yüksel A, Aouinet H, Wang D, Arıcı M, Sammouda H. Efficiency assessment on roof geometry and trombe wall shape for improving buildings’ heating performance. Buildings. 2024 May 1;14(5):1297. doi:10.3390/buildings14051297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Fan M, Li N, Yu B. The performance analysis of a novel sterilizable trombe wall based on the combined effect of heat and UV light. Buildings. 2024 May 1;14(5):1210. doi:10.3390/buildings14051210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Hou L, Tai H, Liu Y, Zhu Y, Zhao X, Yang L. Thermal design of insulation on the outside of the cavity for a Trombe wall with phase change materials. Energy Build. 2024 May;311:114168. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.114168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Hernández-Pérez I, Rodriguez-Ake Á, Sauceda-Carvajal D, Hernández-López I, Kumar B, Zavala-Guillén I. Experimental thermal assessment of a trombe wall under a semi-arid mediterranean climate of Mexico. Energies. 2025 Jan 1;18(1):1858. doi:10.3390/en18010185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Cao S, Ling J, Wu T, Wu L, Guo P. Coupling vertical wall-attached ventilation with PV-Trombe wall: a numerical simulation study. J Build Eng. 2025 Jun;104:112342. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2025.112342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zhou L, Huo J, Zhou T, Jin S. Investigation on the thermal performance of a composite Trombe wall under steady state condition. Energy Build. 2020 May;214:109815. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2020.109815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Gu T, Li N, Li Y, Che L, Yu B, Liu H. A novel Trombe wall with photo-thermal synergistically catalytic purification blinds: material and experimental performance study. Energy. 2023;278:128013. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.128013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Prozuments A, Borodinecs A, Bajare D. Trombe wall system’s thermal energy output analysis at a factory building. Energies. 2023 Feb 1;16(4):1887. doi:10.3390/en16041887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Laribi A, Begot S, Surdyk D, Ait-Oumeziane Y, Lepiller V, Desevaux P, et al. Experimental study of the influence of the vents on the thermal performance of a Trombe wall [Internet]; 2024 Oct [cited 2025 Sep 18]. Available from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4996714. [Google Scholar]

16. Zheng X, Zhou Y. Dynamic heat-transfer mechanism and performance analysis of an integrated Trombe wall with radiant cooling for natural cooling energy harvesting and air-conditioning. Energy. 2024 Feb;288:129649. doi:10.1016/j.energy.2023.129649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Çolak AB, Rezaei M, Aydin D, Dalkilic AS. Experimental and machine learning research on a multi-functional Trombe wall system. Int J Global Warm. 2024;33(4):404–15. doi:10.1504/ijgw.2024.139902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Bulmez AM, Brezeanu AI, Dragomir G, Fratu M, Iordan NF, Bolocan SI, et al. CFD analysis for a new thrombe wall concept. Buildings. 2024 Mar 1;14(3):579. doi:10.3390/buildings14030579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Dong X, Xiao H, Ma M. Thermal performance of a novel Trombe wall enhanced by a solar energy focusing approach. Low-Carbon Mat Green Construct. 2024;2(1):8. doi:10.1007/s44242-024-00039-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Gao Q, Yang L, Shu Z, He J, Huang Y, Gu D, et al. Numerical and experimental study on the performance of photovoltaic-trombe wall in hot summer and warm winter regions. Energy Eff Match Applicat Potent Build. 2024 Sep 1;14(9):2919. doi:10.3390/buildings14092919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Ali MH, Mawlood MK, Jalal RE, Jalal RE. Performance study of an isolated small scale Trombe wall with partially evacuated air gap. Adv Mech Eng. 2024 Jan 1;16(1). doi:10.1177/16878132231224996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zhang HL, Li B, Shi DK, Wang WW, Zhao FY. Thermal performance and ventilation analysis of a zigzag Trombe wall: full numerical and experimental investigations. Energy Build. 2024;306:113955. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2024.113955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Hashemi SH, Besharati Z, Hashemi SA, Hashemi SA, Babapoor A. Prediction of room temperature in Trombe solar wall systems using machine learning algorithms. Energy Stor Sav. 2024 Dec;3(4):243–9. doi:10.1016/j.enss.2024.09.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Xiao Y, Yang Q, Fei F, Li K, Jiang Y, Zhang Y, et al. Review of Trombe wall technology: trends in optimization. Renew Sustain Energ Rev. 2024 Aug;200:114503. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2024.114503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kandilli C, Gür M, Yilmaz H, Öztop HF. Experimental and numerical analyses of a model Trombe wall employing the natural zeolite/perlite composite plate as a thermal mass for nearly zero energy buildings. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2025 Jan 1;160:108386. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2024.108386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Abdelsamea A, Hassan H, Shokry H, Asawa T, Mahmoud H. An innovative multi-story trombe wall as a passive cooling and heating technique in hot climate regions: a simulation-optimization study. Buildings. 2025 Apr 1;15(7):1150. doi:10.3390/buildings15071150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Balcomb JD. Passive solar buildings. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press; 2008 Oct 29. [Google Scholar]

28. Tiwari GN. Solar energy: fundamentals, design, modelling and applications. Oxford, UK: Alpha Science International; 2002. [Google Scholar]

29. Climate Consultant 6 Murray Milne. Climate Consultant 6 [Internet]; 2021 [cited 2025 Feb 18]. Available from: https://energy-design-tools.sbse.org/. [Google Scholar]

30. Ávila-Hernández A, Simá E, Xamán J, Hernández-Pérez I, Téllez-Velázquez E, Chagolla-Aranda MA. Test box experiment and simulations of a green-roof: thermal and energy performance of a residential building standard for Mexico. Energy Build. 2020 Feb;209:109709. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2019.109709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Coakley D, Raftery P, Keane M. A review of methods to match building energy simulation models to measured data. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2014;37(5147):123–41. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2014.05.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Yu S, Cui YM, Xu XL, Feng GH. Impact of civil envelope on energy consumption based on EnergyPlus. Procedia Eng. 2015;121:1528–34. doi:10.1016/j.proeng.2015.09.130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Jiang Y, Chen Q. Buoyancy-driven single-sided natural ventilation in buildings with large openings. Int J Heat Mass Transf. 2003;46(6):973–88. doi:10.1016/s0017-9310(02)00373-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Swami MV, Chandra S. Procedures for calculating natural ventilation airflow rates in buildings. Contract Report. 1987. [Google Scholar]

35. Jiang Z, Kobayashi T, Yamanaka T, Sandberg M, Kobayashi N, Choi N, et al. Validity of Orifice equation and impact of building parameters on wind-induced natural ventilation rates with minute mean wind pressure difference. Build Environ. 2022 Jul;219:109248. doi:10.1016/j.buildenv.2022.109248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kang ST, Park JH, Yuk H, Yun BY, Kim S. Advanced Trombe wall façade design for improving energy efficiency and greenhouse gas emissions in solar limited buildings. Sol Energy. 2025;293:113492. doi:10.1016/j.solener.2025.113492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Kang ST, Park JH, Yuk H, Yun BY, Kim S. ASHRAE Standard 55-2020. [cited 2025 Sep 18]. Available from: https://www.ashrae.org/file%20library/technical%20resources/standards%20and%20guidelines/standards%20addenda/55_2020_a_20210430.pdf. [Google Scholar]

38. Juan S-A, Aguilar-Castro, María K, Trejo-Torres, Betzabeth Z, Méndez-Torres et al. Simulación energética de la sala en una vivienda social con muro trombe para evaluar el confort térmico. Revista de Investigación y Desarrollo. 2017;3(9):31–9. (In Spain). [Google Scholar]

39. Salmerón JM, Álvarez S, Molina JL, Ruiz A. Tightening the energy consumptions of buildings depending on their typology and on Climate Severity Indexes. Energy Build. 2013;58(5):372–7. doi:10.1016/j.enbuild.2012.09.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools