Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Drying Performance and Quality Variations of Corn Kernels at Different Drying Methods

1 Department of Mechanical and Electrical Engineering, Hunan Automotive Engineering Vocational University, Zhuzhou, 412000, China

2 Department of Mechanical and Intelligent Manufacturing, Central South University of Forestry and Technology, Changsha, 410004, China

* Corresponding Author: Shihui Xiao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovations in Drying Technologies: Bridging Industrial, Environmental, and Energy Efficiency Challenges)

Frontiers in Heat and Mass Transfer 2025, 23(6), 2127-2146. https://doi.org/10.32604/fhmt.2025.070973

Received 28 July 2025; Accepted 28 October 2025; Issue published 31 December 2025

Abstract

This study evaluated corn kernel drying performance and quality changes using hot air drying (HAD) and infrared drying (ID) across temperatures ranging from 55°C to 80°C. Optimal drying parameters were determined by using the entropy weight method, with drying time, specific energy consumption, damage rate, fatty acids, starch, polyphenols, and flavonoids as indicators. Results demonstrated that ID significantly outperformed HAD, achieving drying times up to 20% shorter and reducing specific energy consumption and kernel damage by up to 79.3% and 66.7%, respectively, while also better preserving quality attributes. Both methods exhibited drying profiles characterized by acceleration, constant, and falling rate periods, although the constant rate phase was distinctly observable only at lower temperatures. The effective moisture diffusivity under ID was consistently higher than that under HAD, with a maximum increase of 20.4%. The optimal drying conditions were HAD at 65°C and ID at 80°C. A BP model was also developed and it showed better predictive performance and adaptability than classical mathematical models.Keywords

Waxy corn has simple cultivation technology, a short growth cycle, and high nutritional and economic value; thus, it is welcomed by corn producers and is planted around the world [1]. A lot of nutrients, such as fatty acids, polyphenols, flavonoids, and starch, exist in waxy corns, which not only have an anti-aging effect on the heart and brain vessels of the human body, but also can promote the intellectual development of teenagers [2]. Waxy corn is one of the important foods for humans and animals; however, fresh corn kernel has a high moisture content. If they cannot be dried in time, they will become rancid and deteriorated, which will adversely affect the safe storage and edible quality of corn. Therefore, selecting an appropriate drying method is crucial for corn kernels. Proper drying minimizes seed respiration and organic matter decomposition, while also eliminating moth infestations and preventing mold growth and reproduction.

Hot air drying (HAD), as a traditional drying method, has been widely used in the field of agricultural product drying [3–5]. Wei et al. [6] studied the uneven drying of corn kernels in HAD and proposed a new convection strategy to effectively alleviate this uneven phenomenon. Wang et al. [7] investigated the changes in starch structure and physicochemical properties of two types of corn kernels during HAD. The study showed that HAD reduced the crystallinity and disordered structure of starch in corn kernels, which may affect their performance in food processing applications. Elqadhi et al. [8] focused on the flavor of corn kernels and found that the samples treated with HAD would form more volatile components, which significantly enhanced the flavor of sweet corn. However, HAD usually requires a long drying time, which may lead to the degradation or deactivation of the thermosensitive substances (such as vitamins, enzymes, aroma components, etc.), affecting the quality of the product. In addition, long-term exposure of materials to hot air may cause the surface to become excessively dry or brittle, affecting the appearance and taste of the materials. Therefore, it is necessary to explore new drying methods, such as infrared drying (ID), microwave drying (MD), and vacuum drying (VD) [9–11]. Among them, ID is considered a potential drying method that can be applied to various foods. Barba et al. [12] used ID to successfully increase the polyphenolic recovery rate from purple corn by over 120%. Bassey et al. [13] improved the quality of dragon fruit by adopting a new ID method. Xu et al. [14] found that ID was more suitable for producing products with strong flavors. Chao et al. [15] observed that pretreated pumpkins had higher drying efficiency and quality under ID.

In addition, mathematical modeling serves as a critical tool for investigating the effects of different drying parameters and optimizing the process. Furthermore, it enables the prediction of dynamic changes during drying, thereby facilitating the transition toward modernized and intelligent industrial production. For example, Senadeera et al. [16], Mondal et al. [17] and Kusuma et al. [18] used various classical mathematical models, such as Page, Lewis, and Midilli and Kucuk to predict the drying characteristics of persimmon slices, corn kernels, and clove leaves, all of which achieved good results. However, when describing complex and nonlinear relationships between various factors during materials drying, backpropagation neural networks (BP) have stronger modeling capabilities, adaptability, and high fault tolerance compared to traditional models, making them increasingly widely used. Zhang et al. [19] adopted a BP neural network in the drying of yams and successfully optimized the drying process. Wang et al. [20] applied BP to monitor the drying process of rice and found that the BP neural network could effectively reflect the influence of different factors on the drying process.

In summary, different drying methods (ID and HAD) have their own advantages. Although studies on corn kernel drying under ID and HAD exist, a comprehensive comparative analysis of ID and HAD methods is still required to provide energy-efficient and quality preserving strategies from different perspectives. Therefore, this article explores the effects of these two drying methods on drying characteristics and various qualities (drying time, drying rate, energy consumption, effective moisture diffusivity, damage rate, fatty acids, starch, polyphenols, and flavonoids, etc.) of corn kernels at different drying temperatures. In addition, a BP network model and multiple classical mathematical models were used to fit the drying process of corn kernels to predict the moisture variations under different drying conditions. By comprehensively evaluating the drying kinetics and quality metrics of dried corn kernels, optimal methods and conditions were subsequently identified, establishing a theoretical framework for corn kernel storage and processing.

The white waxy corn used in this experiment was purchased from Jining, Shandong, China, which was planted at a farm there. Fresh waxy corn without mildew was stored in the artificial climate chamber with a temperature of 6°C ± 1°C.

The instruments used in this experiment are: electric constant temperature drying oven (DHG-9075A) (Fig. 1), temperature control accuracy ≤ ±1°C, Yiheng Scientific Instrument Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China, with a box size of 450 mm × 440 mm × 500 mm and a constant air velocity of 1 m/s; infrared drying oven (YLHW) (Fig. 2), temperature control accuracy ≤ ±1°C, Yuecheng Industrial Equipment Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China, with a box size of 450 mm × 350 mm × 400 mm, containing four 500 W infrared lamps inside; analytical balance with an accuracy of 0.001 g (JY1003), Calvin Technology, Ningbo, China; SFY-60 infrared rapid moisture, Guanya Electronic Technology Co., Ltd., Shenzhen, China.

Figure 1: Hot air drying oven

Figure 2: Infrared drying oven

Fresh white waxy corns were taken out of the artificial climate chamber and placed at room temperature. After the corns were restored to room temperature, they were shelled. The complete corn kernels (no pulp exposure) were placed on an aluminum plate in a single layer with a thickness of about 8 mm, and immediately put into the drying oven. Corn kernel mass was recorded at 30-min intervals until reaching the target moisture content (5% d.b.). Dried samples were then sealed in airtight bags and stored at ambient temperature (25°C ± 2°C) pending analysis. For ID, 100 complete corn kernels were placed in an infrared drying oven at 55°C, 60°C, 65°C, 70°C, 75°C, and 80°C. The infrared wavelength varied from 3–40 μm, and the heating power was 4 kW. For HAD, 100 complete corn kernels were placed in a hot air drying oven at 55°C, 60°C, 65°C, 70°C, 75°C, and 80°C. The air velocity was stabilized at 1 m/s throughout the experiments.

where mt is the mass at time t and md is the mass of the dry sample [21].

where Mt is the dry moisture content at time t, M0 is the initial dry moisture content [22].

The drying rate is the moisture content loss divided by the drying time interval [23]:

where ΔM is the difference in moisture content between adjacent samples, Δt represents the time gap between successive measurements.

2.3.4 Effective Moisture Diffusivity (Deff)

The effective water diffusion coefficient of corn kernels under different drying conditions was calculated and obtained using Fick’s second law as follows [24]:

where Re represents the equivalent radius of corn kernels (m), t represents the drying time (s).

2.3.5 Specific Energy Consumption (SEC)

where E represents the energy consumed during the drying process (kW·h), Δm is the mass of water removed during the drying process (kg) [25].

The damage rate was determined by observing corn kernel cracks with the naked eye and counting the number of cracked corn kernels.

Free fatty acid content was determined according to the national standard GB/T20570-2015 as follows: 10 g of the crushed sample was mixed with 50 mL of anhydrous ethanol, and shaken on a reciprocating shaker for 30 min, then stood for 1–2 min and filtered into a colorimetric tube. A 25 mL aliquot of the filtrate was placed in a 150 mL conical flask. Then, 50 mL of CO2-free distilled water and 5 drops of phenolphthalein indicator were added. This mixture was titrated with standard KOH solution to a faint pink endpoint that persisted for 30 s, and the volume of the consumed KOH standard titration solution was recorded. Blank experiments were conducted to calculate the free fatty acid content of the sample.

The total polyphenol content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method. A mixture was prepared by combining 5 μL of the sample solution with 195 μL of distilled water and 25 μL of Folin-Ciocalteu reagent. After 6 min, 75 μL of 7% sodium carbonate (Na2CO3) solution was added. The solution was then incubated in the dark for 30 min. Absorbance was measured at 765 nm against a water blank. Results were quantified using a gallic acid standard curve.

The total flavonoid content was determined using a colorimetric assay. A mixture was prepared by combining 25 μL of the sample solution with 110 μL of NaNO2 solution. After 5 min incubation at room temperature, 15 μL of AlCl3 solution was added. The solution was incubated for an additional 6 min, followed by the addition of 100 μL of NaOH solution. Following a final 15-min incubation, absorbance was measured at 510 nm against a water blank. Results were quantified using a catechin standard curve.

The starch content was determined according to the Chinese National Standard GB5009.9-2016 (enzymatic hydrolysis method). Following the removal of fat and soluble sugars, starch was enzymatically hydrolyzed to dextrins using amylase, then quantitatively hydrolyzed to glucose using hydrochloric acid. The resulting reducing sugars were determined as glucose equivalents and converted to starch content using a factor of 0.9.

The sample solution mentioned above was prepared as follows: 1 g of the sample powder was passed through a 40 mesh sieve, then 40 mL of 80% methanol solution was added. The mixture was ultrasonically extracted at 65°C for 30 min, then centrifuged at 4000 rpm at 25°C for 4 min. The supernatant was taken, and the residue was filtered and extracted according to the above steps. The combined supernatants were concentrated using a rotary evaporator to remove methanol. The extract was then adjusted to a final volume of 25 mL with solvent, yielding a solution concentration of 40 mg/mL. Then the sample solution was put in the refrigerator for later use, and it should be diluted to 1 mg/mL during the measurement.

A BP neural network and several commonly used thin-layer drying mathematical models were adopted to fit the changes in moisture content during the drying process of corn kernels. The input of the BP neural network is the drying method, drying temperature, and drying time, and the output is the moisture ratio. Statistical indicators, including R2, RMSE, and

where MRpre, i is the i-th predicted dimensionless moisture ratio; MRexp, i is the i-th experimental dimensionless moisture ratio; MR is the average dimensionless moisture ratio; N is the number of observations and nm is the number of constants in the model.

The experimental data were processed using Excel, and the drying curve was plotted using Origin2022. Statistical analysis was conducted using SPSS software, and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for testing (p < 0.05). All mathematical models were modeled using Origin2022 and fitted for prediction.

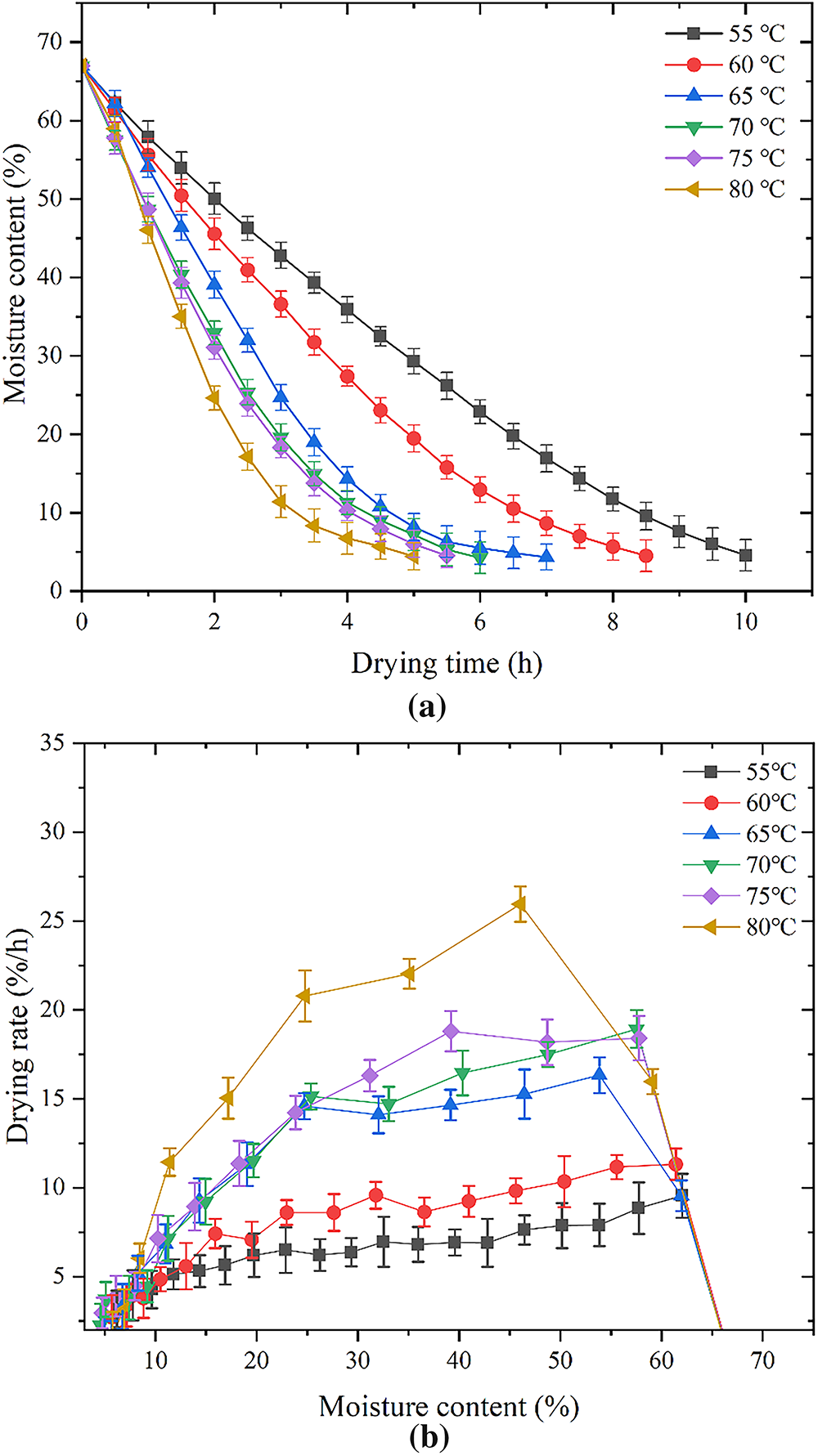

Fig. 3 illustrates the corn kernel drying dynamics under HAD at 55°C, 60°C, 65°C, 70°C, 75°C, and 80°C. As expected, the drying duration decreased with rising temperatures, requiring 10 h (55°C), 8.5 h (60°C), 7 h (65°C), 6 h (70°C), 5.5 h (75°C), and 5 h (80°C) to reach the target moisture content (about 5%). Under different hot air temperatures, the loss of moisture content was rapid in the initial stage of drying, and then gradually slowed down [27]. This was because there was free water, which was in great freedom and strong fluidity, and bound water, which was in a low degree of freedom, inside the corn kernels [28]. During the early drying, the moisture content, especially the free water content, was relatively high, and the surface of the corn kernel was in direct contact with hot air. At this time, the migration of water with a high freedom was relatively easy, and thus the loss of moisture content was fast. As the drying time extended, the corn kernel epidermis shrank, the cell structure became tight, and the internal channels were squeezed and narrowed by starch, protein, etc., thus increasing moisture migration resistance. Besides, the remaining bound water with restricted mobility further hindered the drying process. Therefore, the water removal slowed down. Ren et al. [29] investigated the internal moisture variation in corn kernels under HAD by the low field-NMR method. They also found that the water loss decreased with the extension of drying time as the internal channels became compact and the driving force of internal water migration reduced. Charmongkolpradit et al. [30] also studied the drying characteristics of fresh white waxy corn under HAD. Their study showed that the drying time was 5.75 and 5 h at 75°C and 80°C, respectively, which was very close to this study.

Figure 3: HAD characteristics of corn kernels: (a) Mt vs. drying time; (b) DR vs. Mt

From Fig. 3b, one can see that the higher the temperature, the greater the drying rate (DR) and the shorter the drying time. The drying process of corn kernels can be divided into an acceleration rate period, a constant rate period and a falling rate period. The drying rate at each temperature increased in the initial stage, and then showed a downward trend. This was because free water inside the corn kernels continuously diffused to the surface to evaporate rapidly at the beginning, and thus, the DR value was high. As the drying progressed, free water—readily evaporated in early stages—diminished, leaving bound water strongly associated with the macromolecular substances in the cell. The constrained fluidity of this bound phase increased mass transfer resistance, causing the drying rate to decline gradually. When the drying temperature was relatively low, there was an obvious constant rate period, while at high temperature (e.g., 80°C), the drying curve quickly turned from the acceleration rate period to the falling rate period and the constant rate period disappeared. This is because drying is a process which the water on the surface and inside the material evaporates at the same time, i.e., when the water on the corn kernel surface vaporizes, the internal moisture also diffuses outward. The migration of water was mainly controlled by surface vaporization at the beginning. At this time, the heat absorbed by the corn kernel was used for the moisture vaporization; the material itself did not heat up. When the temperature was relatively high, the moisture vaporization was fast and the drying process quickly shifted from surface vaporization to internal moisture diffusion, thus the constant rate period was not obvious.

Besides, it was noted that when the temperature was low (55°C), the falling-rate deceleration was gradual. However, when the temperature was high (80°C), the corresponding decrease in the DR value was fast. This might be because when the temperature was relatively high, the moisture on the corn kernel surface was lost quickly, leading to the shrinkage and hardening of the epidermis, and thereby increasing the resistance to moisture migration. Moreover, the internal channel became narrow during the drying process, which also hindered the moisture inside the corn kernel from migrating outward. While at 55°C, the epidermal shrinkage was not as severe as at 80°C, thus the resistance of moisture migration was relatively small and the decrease of drying rate was slow. However, due to the lower driving force of internal moisture migration, the overall drying rate at 55°C was smaller than that at 80°C. The same conclusion also appears in the drying of Camellia oleifera fruit. Researchers have found that high temperatures may cause the surface of orange peel to harden, resulting in higher energy consumption at 80°C [23].

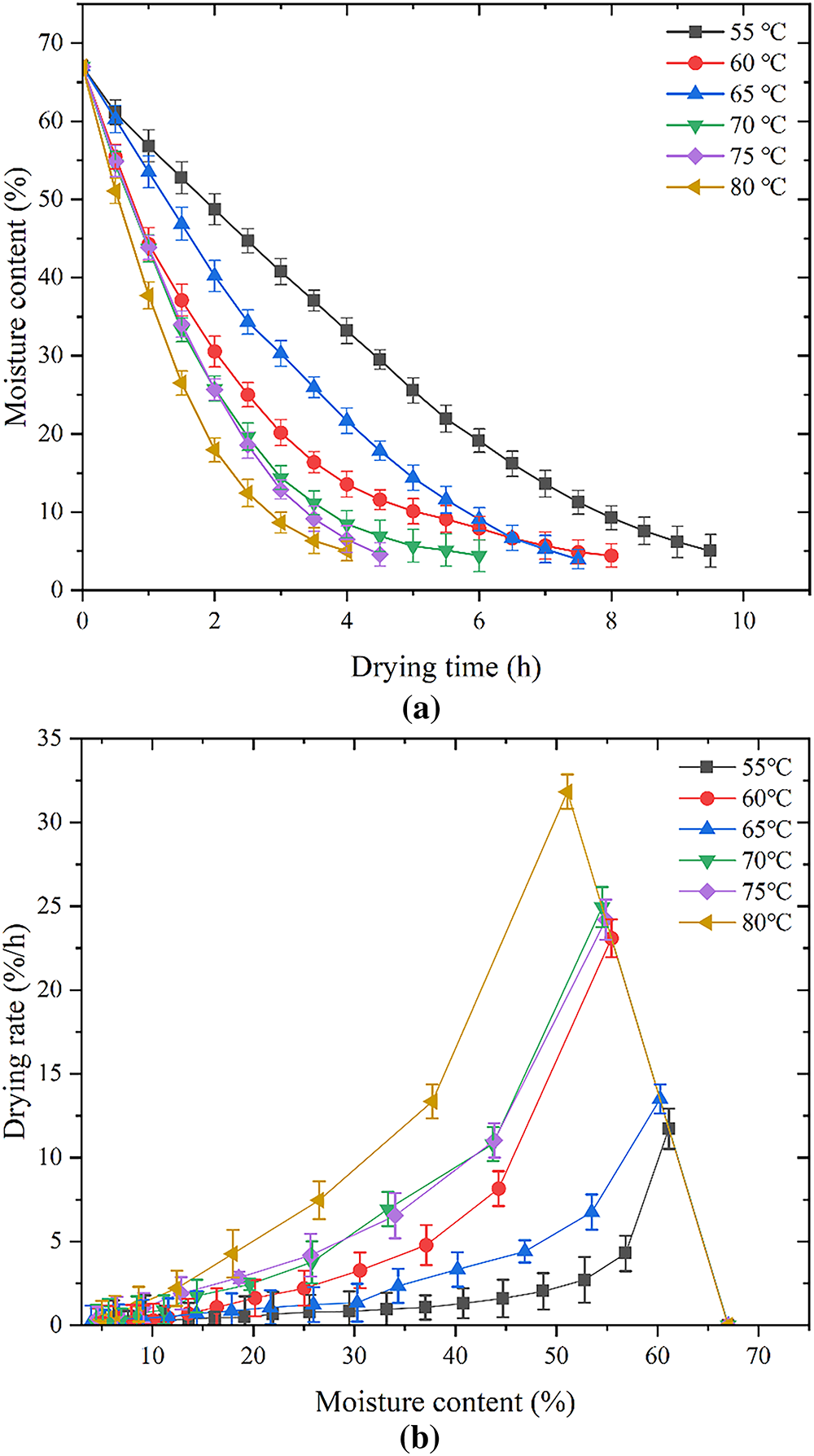

Fig. 4 shows the drying characteristics of corn kernels under ID at 55°C, 60°C, 65°C, 70°C, 75°C, and 80°C. Similar to HAD, the higher the infrared temperature, the shorter the total drying time, which was 9.5, 8, 7.5, 6, 4.5 and 4 h at 55°C, 60°C, 65°C, 70°C, 75°C and 80°C, respectively. The infrared rays irradiated the sample surface and penetrated into the interior of the sample with a certain radiation depth. This heating method makes the inside and outside of the corn kernel generate heat at the same time, which is beneficial for reducing the hindering effects caused by temperature gradient and shrinkage of epidermis when the material is heated only from the surface of the material, such as HAD; therefore, the DR value is relatively high. The drying time of ID was shorter than that of HAD, except for 65°C. The relatively slow descending trend of moisture content at 65°C might be caused by the hybrid effects of drying temperature and epidermal shrinkage of corn kernels. Fig. 4b shows the relationship between DR and Mt. DR values under various temperatures, showing a short acceleration rate period followed by a continuous falling rate period, which was caused by the low freedom of remaining bound water and the epidermal shrinkage of corn kernels. The constant rate period occurred only at low temperatures, which meant that the ID was mainly controlled by internal water diffusion at relatively high temperatures (>65°C). Timm et al. [31] also observed a drying time of approximately 280 min at 70°C, a result that aligns closely (within 10%) with the data from this study.

Figure 4: ID characteristics of corn kernels: (a) Mt vs. drying time; (b) DR vs. Mt

3.3 Comparison between HAD and ID

Comparing HAD and ID, it was found that the drying rate of corn kernels under ID was higher than that under HAD, with a drying time reduced by up to 20% and the characteristic of falling rate period drying was more obvious under ID. This is because HAD is a kind of surface heating that which the water directly evaporates on the surface [32]. The epidermal shrinkage of the corn kernel is easy to occur under HAD, which prevents the water inside the corn kernel from migrating outside. ID is a drying method with uniform heating which the infrared rays penetrate into the material and heat the material directly from the inside. The volumetric heating mechanism of ID—penetrating radiation simultaneously energizes internal and external moisture—reduced thermal gradients and shrinkage effects prevalent in HAD. Thus, the infrared drying rate is higher and the drying time is shorter.

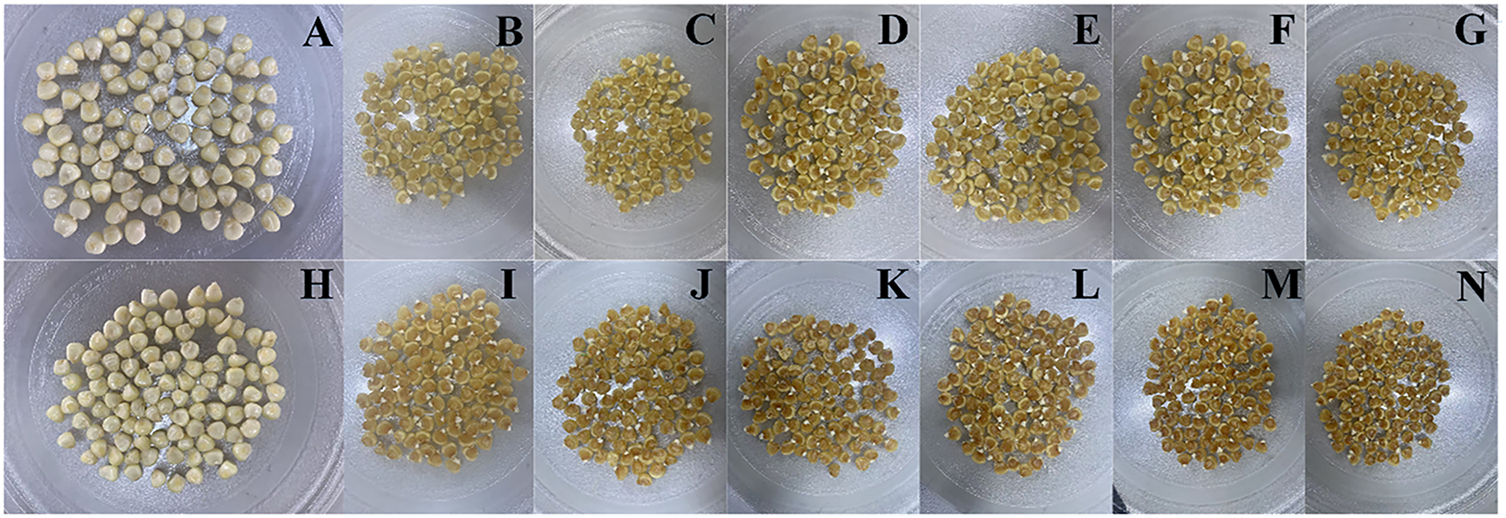

Fig. 5 shows the corn kernels dried under HAD and ID at six different drying temperatures. As shown in the figure, with the increase of temperature, the coking reaction of corn kernels during the drying process becomes more obvious, and the corn kernels will show shrinkage, dryness, and deepening of color. Compared with HAD, the color change of ID dried corn kernels was more pronounced. This may be because ID provides more energy per unit time to the corn kernels, causing a rapid increase in surface temperature in a short period of time, leading to surface cracking, coking, and discoloration. In the study of citrus peel under various drying methods, Lin et al. [25] also found that ID would cause a darker color of citrus peel.

Figure 5: Corn kernel images under different methods and drying temperatures. (A–G) HAD method: (A) fresh corn kernels; (B) 55°C; (C) 60°C; (D) 65°C; (E) 70°C; (F) 75°C; (G) 80°C; (H–N) ID method: (H) fresh corn kernels; (I) 55°C; (J) 60°C; (K) 65°C; (L) 75°C; (M) 75°C; (N) 80°C

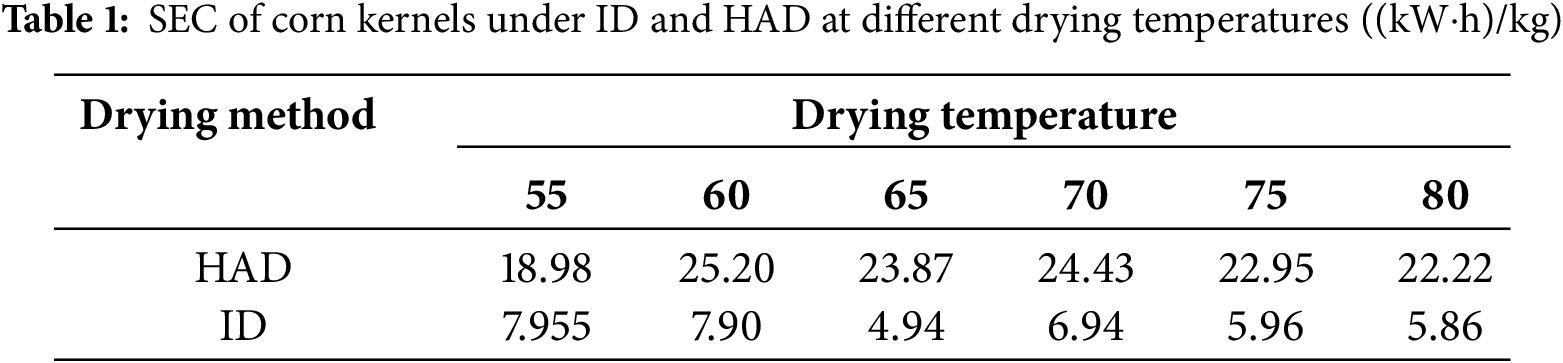

Table 1 shows the specific energy consumption (SEC) of corn kernels at six drying temperatures in HAD and ID. According to the table, the energy consumption is not proportional to the drying temperature. The lowest SEC value in both HAD and ID is at 65°C, indicating that the energy utilization efficiency reaches its maximum at this temperature. This is because the drying oven maintained at 65°C required only a moderate amount of energy while the drying time was significantly shortened (30% reduction in HAD and 21% in ID compared to 55°C). Moreover, ID method requires less SEC than HAD method, because a large part of the energy used in HAD is for heating the medium, while ID directly heats the material through radiation, resulting in higher energy utilization efficiency and lower SEC. The same conclusion also appeared in Lin et al. [25]’s study on the drying of citrus peel, in which the minimum SEC required for citrus peel in ID was only 73% of that in HAD. In the study of Yu et al. [33] on the drying of blueberries under different drying methods, it was also found that the SEC value of ID was always lower than that of HAD at the same drying conditions.

3.4 Effective Moisture Diffusivity (Deff)

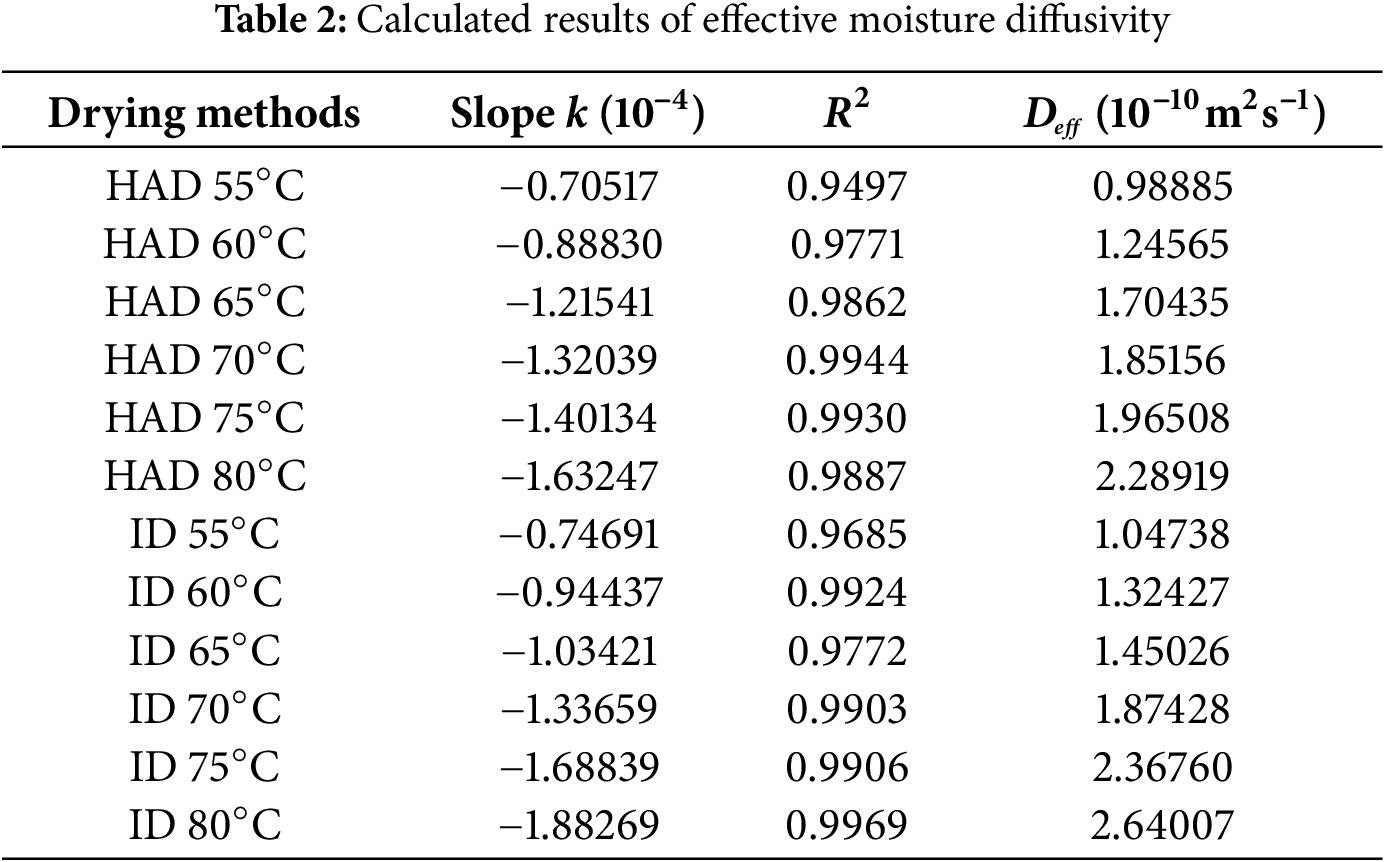

Table 2 shows the calculated results of the effective moisture diffusivity of HAD and ID. The results indicated that as the drying temperature increased from 55°C to 80°C, Deff value increased from 0.98885 × 10−10 m2/s to 2.28919 × 10−10 m2/s under HAD, and from 1.04738 × 10−10 m2/s to 2.64007 × 10−10 m2/s under ID. This demonstrates that elevated temperature significantly promotes internal moisture diffusion. At all tested temperatures, Deff values under ID were consistently higher than those under HAD and the difference was particularly pronounced at higher temperatures (75°C–80°C), where the maximum Deff under ID was 20.4% higher than that of HAD. These findings suggest that ID offers a distinct advantage in enhancing internal moisture migration. This can be attributed to the nature of infrared radiation, as it enables direct energy transfer into the material, reducing the heat transfer path and improving thermal efficiency. Consequently, the mobility of water molecules is enhanced and the moisture diffusion process is accelerated. Similar results were also found in the drying of various agricultural products, such as passion fruit, pumpkin seeds, etc. [34].

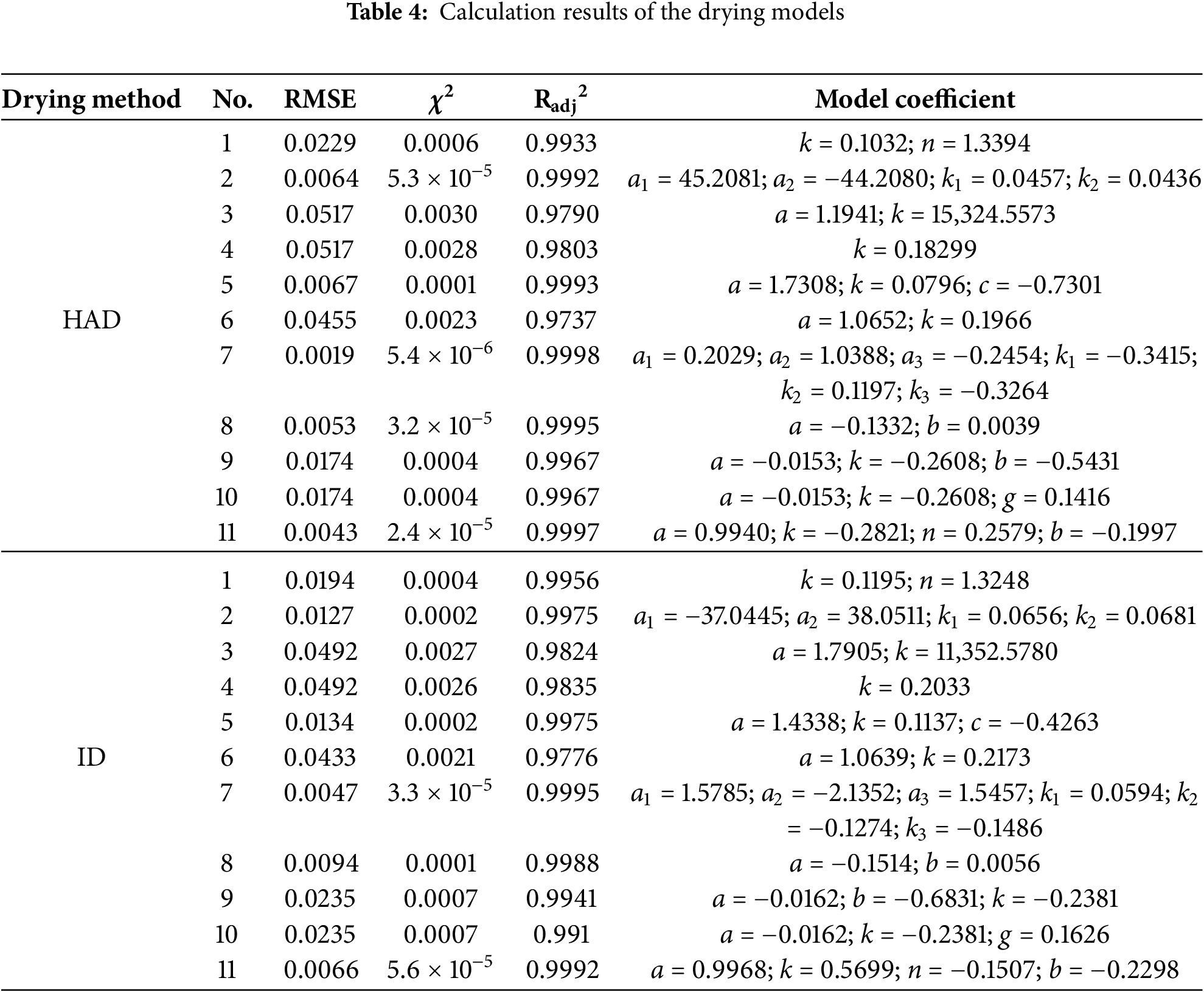

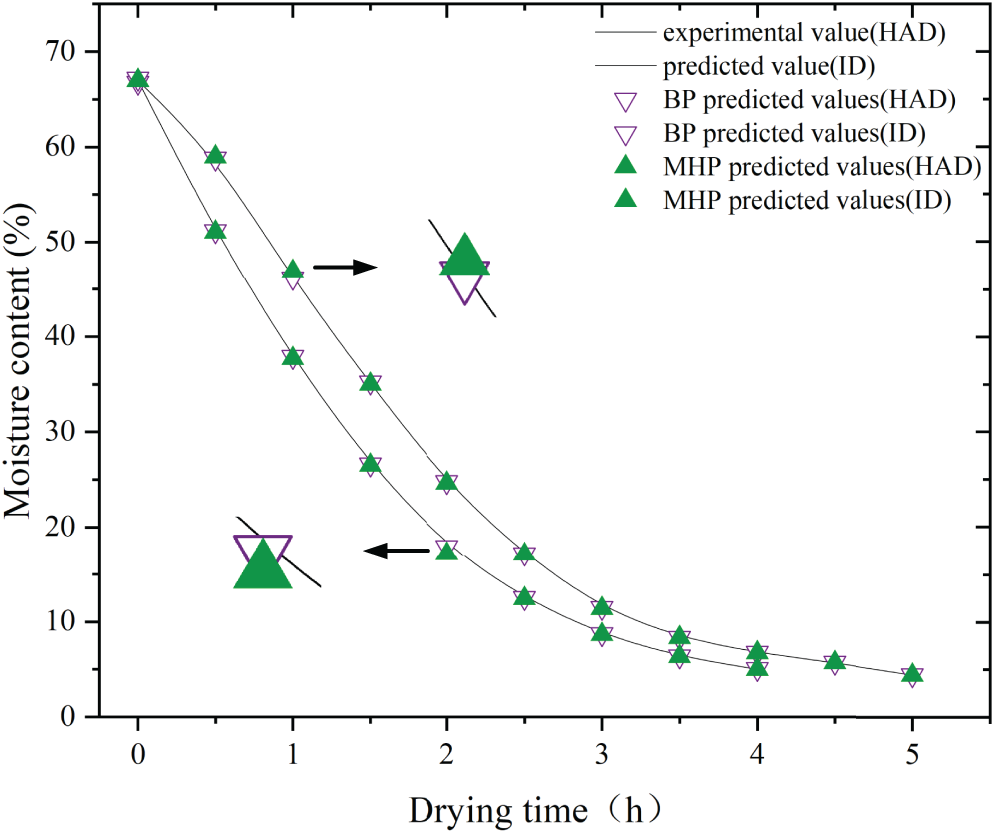

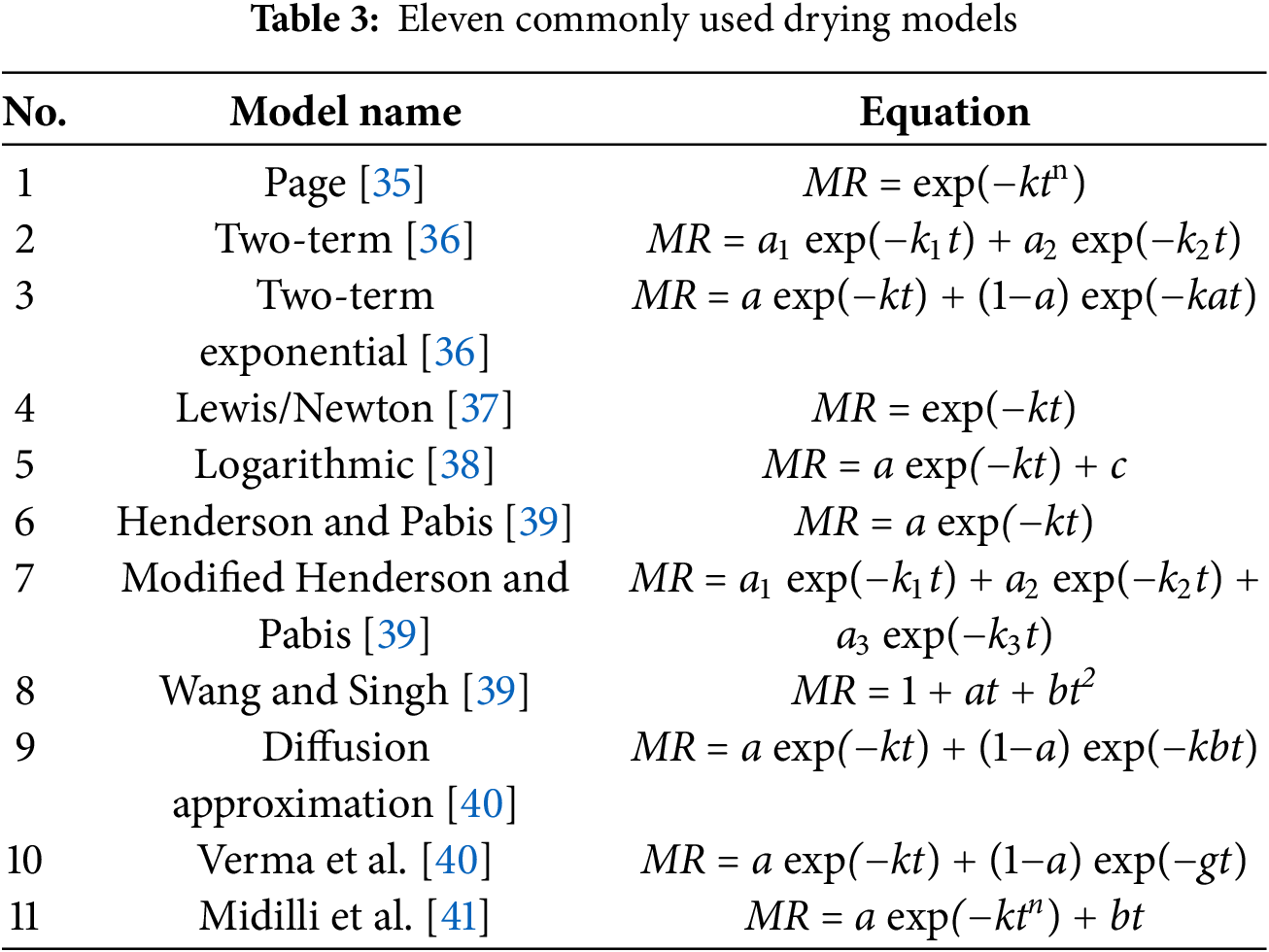

Eleven drying kinetic models were chosen to describe the HAD and ID processes of corn kernels, as shown in Table 3. The fitting results at a hot air and infrared drying temperature of 55°C are presented in Table 4. As shown in Table 4, 11 kinetic models all agreed well with the experimental data under the two drying methods. Among them, the fitting degree of the No. 7 model (MHP model) was the highest. The R2 values under HAD and ID were 0.9998 and 0.9995, respectively, and the χ2 and RMSE (0.0019 and 0.0047) values were the lowest. The BP network model was developed by training the experimental data. The R2 and RMSE values were 0.9999 and 0.0007, respectively, indicating that the model has a high accuracy. However, unlike classical mathematical models (e.g., MHP Model), which require the recalibration of parameters (e.g., a and k) for different drying methods and conditions, the BP model demonstrates high adaptability by maintaining its parameter set across varying operational scenarios. Fig. 6 shows the comparison of predicted and experimental moisture ratios at 80°C. A close agreement is observed, with the maximum error not exceeding 8%, indicating that these two models can accurately predict the moisture change of waxy corn kernels during HAD and ID processes.

Figure 6: Comparison of experimental and predicted values at 80°C

3.6 Evaluation of Drying Quality

Damage rate is an important index to evaluate the quality of corn kernel drying. For HAD, the damage rate of corn kernel at 55°C, 60°C, 65°C, 70°C, 75°C, and 80°C was 6%, 9%, 13%, 20%, 27%, and 31%, respectively, while for ID, the damage rate was 2%, 3%, 5%, 12%, 16%, and 25% at 55°C, 60°C, 65°C, 70°C, 75°C, and 80°C, respectively. It can be seen that the damage rates of HAD and ID both escalated with temperature. Under the same drying temperature, the damage rate of ID was smaller than that of HAD, and the damage rate can be reduced by up to 66.7%, showing that the HAD method would damage the quality of corn kernels. While ID had a relatively small effect on the quality of corn kernels, this was attributable to uniform volumetric heating minimizing thermal stress gradients. Therefore, in terms of damage rate, the ID method is more suitable for the drying of corn kernels. Jiang et al. [42] also found in their study that HAD caused more severe damage to ginseng than ID.

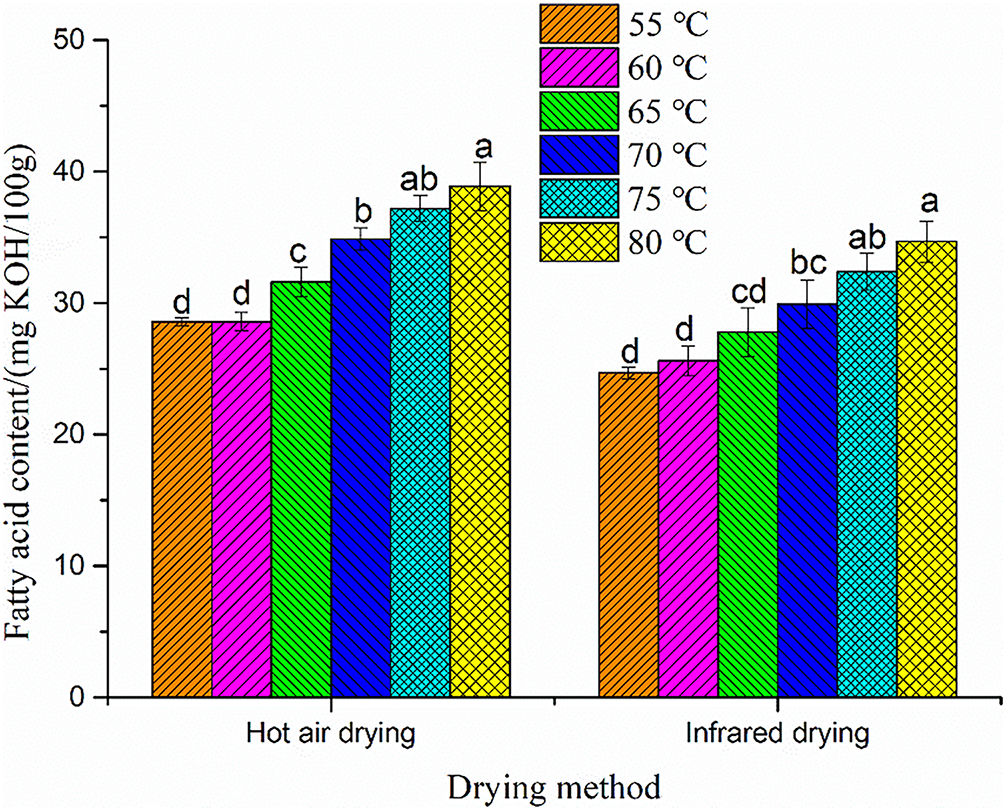

As shown in Fig. 7, the fatty acid value increased with temperature under both HAD and ID methods and the value under ID was lower than that under HAD. This was consistent with the experimental result of Çetin et al. [43]. The fatty acids contained in corn kernels were produced by the hydrolysis and oxidation of their original fatty substances. As the temperature increased during the drying process, the hydrolysis of fatty substances accelerated, thus the fatty acid value increased. Besides, the longer the drying time, the more fatty acids were converted and also the higher the fatty acid value. ID consistently yielded lower values than HAD at equivalent temperatures, correlating with shorter processing times. The fatty acid content of corn kernels under low temperatures (55°C and 60°C) was not significantly different under both the drying methods (HAD: p = 0.316 > 0.05; ID: p = 0.248 > 0.05), however, significant differences at high temperatures were observed. Besides, the statistical results showed that the difference in fatty acid content between HAD and ID was significant (p = 0.0003 < 0.05).

Figure 7: Fatty acid variation of corn kernel under different drying methods and temperatures. Note: Different letters mean there are statistical differences under different temperatures

3.6.3 Starch Content Variation

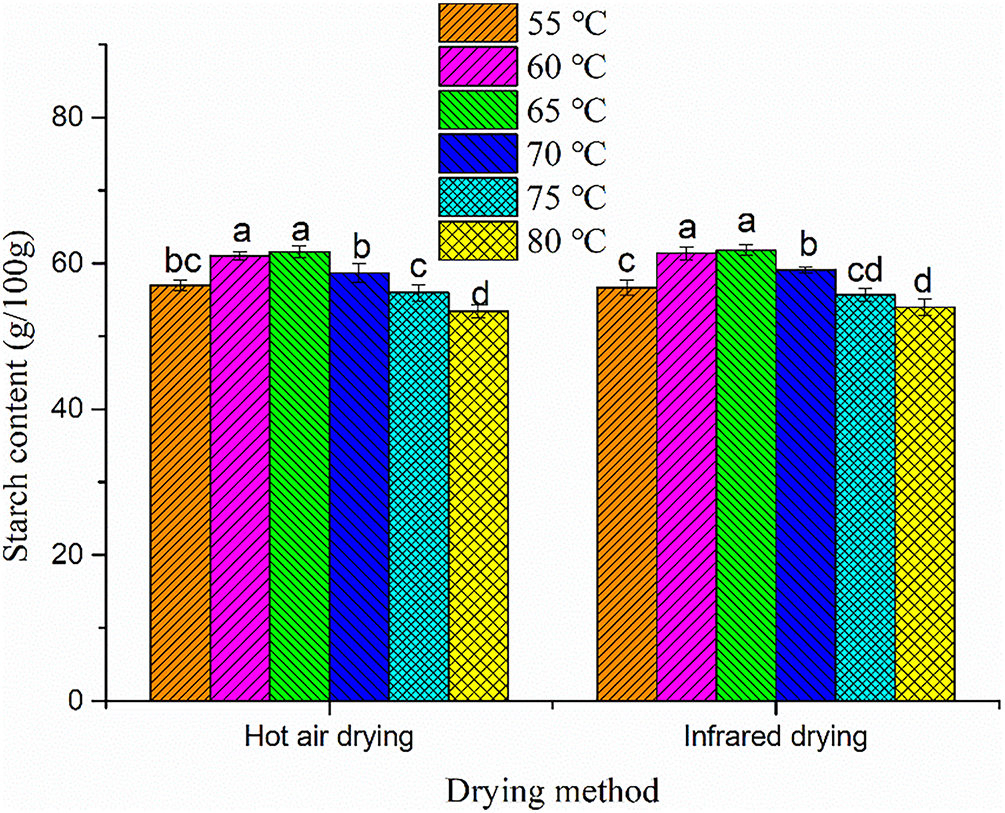

The starch content variation vs. the drying temperature under HAD and ID is depicted in Fig. 8. It showed that the starch content exhibited a trend of first increasing and then decreasing with drying temperature under the two drying methods. The starch in corn kernel includes amylose and amylopectin and it was mainly hydrolyzed into reduced sugars by total amylase, α-amylase and debranching enzyme (DBE), thus the content of starch was closely related to the content of amylase. On one hand, high temperature would significantly reduce the enzyme activities of total amylase, α-amylase and DBE, leading to a decrease in the degree of starch hydrolysis and the starch content. On the other hand, the debranching enzyme acted on amylopectin, resulting in the rupture of the amylopectin side chain, and the broken part was a straight chain; thus, the content of amylose increased [44]. Ren et al. [45] also found an increase in amylose content of corn kernel under a high drying temperature. When the temperature was relatively low (<65°C), the enzyme activities were relatively high and the increase of amylose content led to the increase of starch content with temperature. When the temperature was relatively high, enzyme activities were highly suppressed; thus, the starch content decreased with increasing temperature. The optimum condition of amylase activity was found to be 65°C and in this paper, the highest starch content was achieved at a drying temperature of 60°C–65°C. Therefore, 60°C–65°C was an ideal drying temperature range for achieving high starch content. The starch content of corn kernels between 60°C and 65°C was not significantly different under both the drying methods (HAD: p = 0.625 > 0.05; ID: p = 0.654 > 0.05), while significant differences at other temperatures were observed. Besides, there was no significant difference in starch content between the two drying methods (p = 0.507 > 0.05).

Figure 8: Starch content variation of corn kernel under different drying methods and temperatures. Note: Different letters mean there are statistical differences under different temperatures

3.6.4 The Polyphenol Content Variation (TPC)

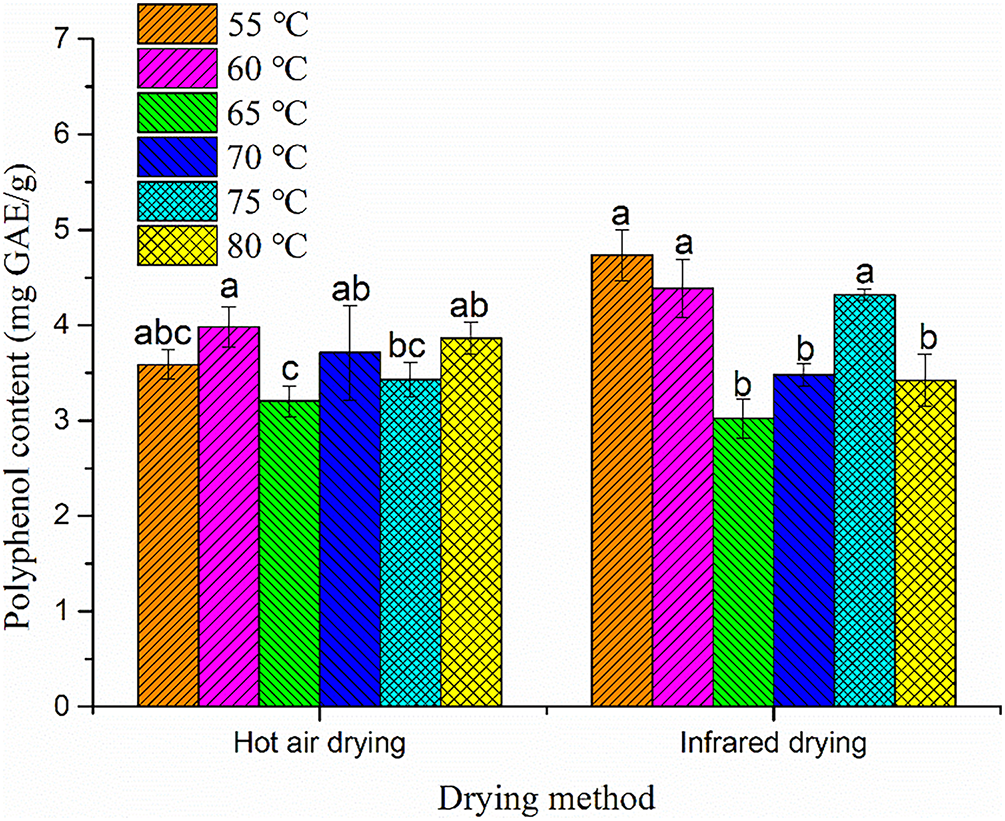

Polyphenols have important functions such as antioxidant, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and hypoglycemic. The content of phenolic compounds in corn is relatively high. Therefore, the polyphenol content variation under different drying methods and conditions is important for the evaluation of corn kernel drying quality. The effects of drying method and temperature on the content of polyphenols are shown in Fig. 9. Basically, the polyphenol content under ID was higher than that under HAD, though the difference was not significant. Besides, the polyphenol content variation vs. the drying temperature was complex. The enzymatic oxidation of PPO (polyphenol oxidase) was the main reason to induce the loss of phenols and the PPO activity decreased with the increase of temperature [46]. When the drying temperature was low, the PPO activity was relatively high and the drying time was relatively long, thus the polyphenols were oxidized significantly and a relatively large number of polyphenols were lost. When the drying temperature was relatively high, the polyphenol oxidase activity decreased significantly, and the drying time was also shortened; thus, the loss of polyphenols was relatively small and the content of polyphenols gradually increased with temperature. However, the phenolic substances were also sensitive to heat and they were thermally degraded when the temperature was relatively high. Thus, the total polyphenol content was the lowest at 65°C under the two drying methods, which might be due to the combined effects of PPO activity variations during the drying process and the heat sensitivity of phenolic substances.

Figure 9: Polyphenol content variation of corn kernel under different drying methods and temperatures. Note: Different letters mean there are statistical differences under different temperatures

3.6.5 The Flavonoid Content Variation (TFC)

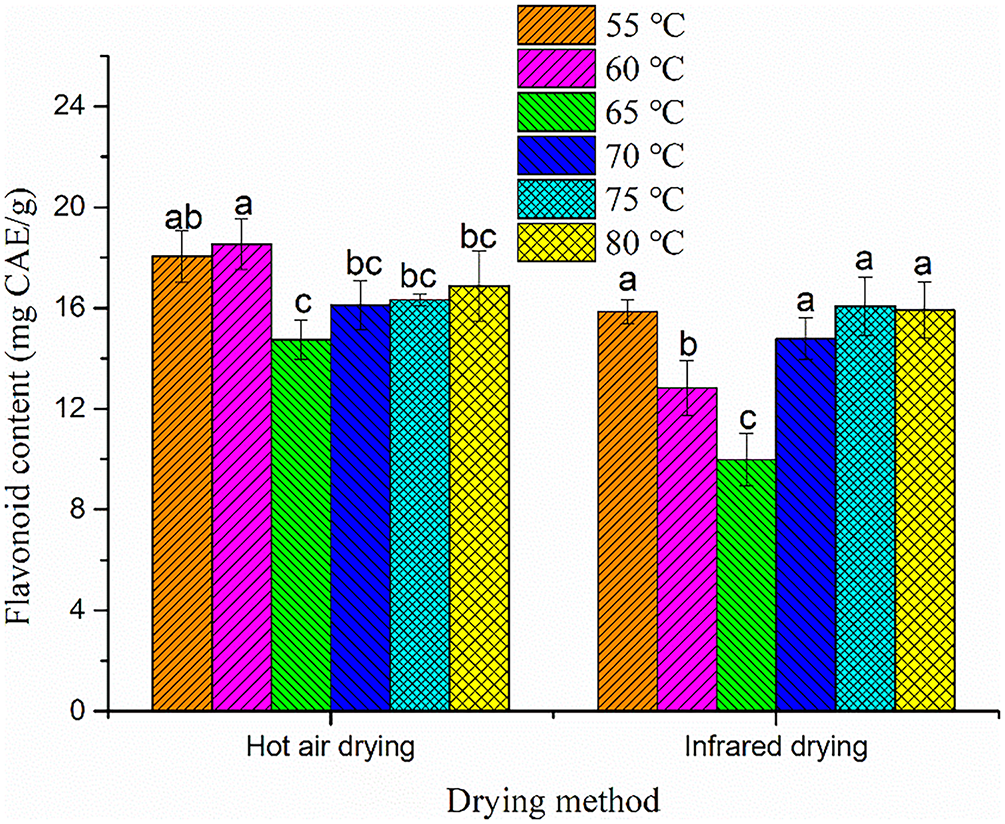

Corn is rich in flavonoids. Studies have indicated that flavonoids have good antioxidant properties and can enhance immunity. It can be used as a natural antioxidant and has great benefits to the human body. Therefore, the flavonoid content variation of corn kernels after drying can also be used as an index for quality evaluation. From Fig. 10, one can see that the content of flavonoids dried by HAD was higher than that by ID. The flavonoid contents had similar changes at different drying temperatures under the two drying methods. When the drying temperature was 65°C, the flavonoid content decreased to a lowest value of 14.8 and 10 mg CAE/g under HAD and ID methods, respectively. When the drying temperature was greater than 65°C, the flavonoid contents under the two drying methods tended to increase with the increase in temperature. Under HAD, the flavonoid content was the highest at a drying temperature of 60°C, while under ID, the flavonoid content was the highest at a drying temperature of 75°C. Flavonoids were sensitive to temperature; thus, continuous drying at high temperatures could destroy the structure of flavonoids and lead to a large loss of nutrients. Therefore, the content of flavonoids first decreased with increasing drying temperature. However, further increasing the temperature could significantly shorten the drying time, and accordingly, also reduce the time to destroy the structure of flavonoids. Therefore, the loss of flavonoids was reduced under short-term high-temperature drying. Significance analysis showed that the drying method and temperature both had significant effects on the flavonoid content at low temperatures (55°C–70°C, HAD: p = 0.049 < 0.05; ID: p = 0.022 < 0.05), while the difference of flavonoid content at high temperatures (70°C–80°C) was negligible under both the two drying methods (HAD: p = 0.23 > 0.05; ID: p = 0.796 > 0.05).

Figure 10: Flavonoid content variation of corn kernel under different drying methods and temperatures. Note: Different letters mean there are statistical differences under different temperatures

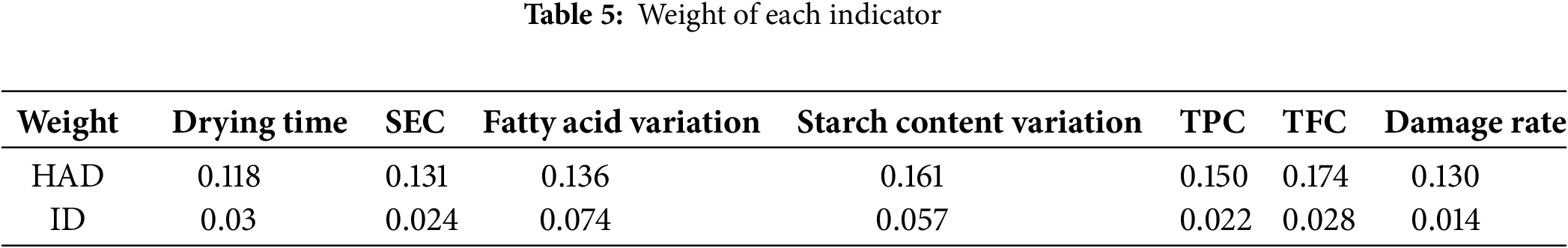

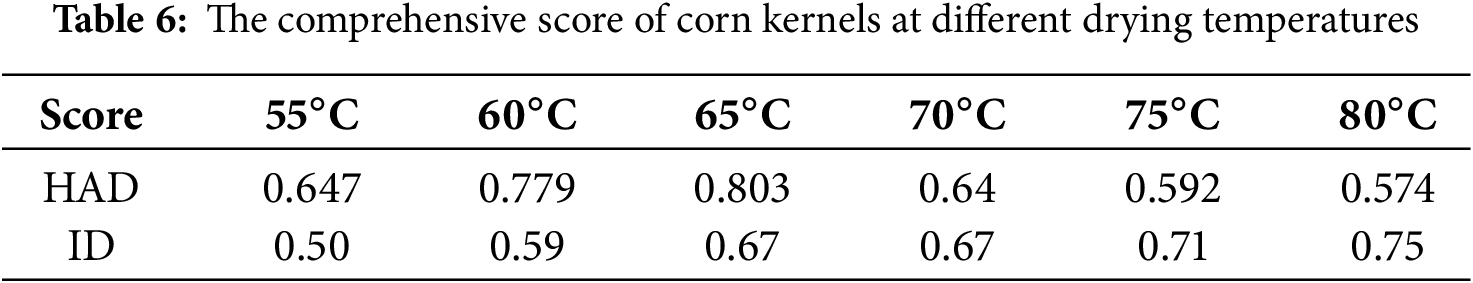

The optimal drying temperature for corn kernels in HAD and ID was determined using the entropy weight method, with drying time, specific energy consumption, damage rate, fatty acids, starch, polyphenols, and flavonoids as indicators. The weights of each index and the comprehensive scores of six temperatures under HAD and ID are shown in Tables 5 and 6, respectively. According to the table, the optimal drying temperature for corn kernels in HAD is 65°C, and the optimal drying temperature for ID is 80°C.

The drying performance and quality variations of corn kernels under ID and HAD methods were experimentally investigated and compared. The key findings were as follows:

(1) The drying time decreased with increasing hot air and infrared drying temperatures. The drying process exhibited three characteristic phases: acceleration, constant rate, and falling rate periods, though the constant rate period was not obvious under high drying temperatures. The drying rate of ID was higher than that of HAD, with a drying time reduced by up to 20% and a Deff value increased by up to 20.4%.

(2) The optimal drying temperatures for HAD and ID are 65°C and 80°C, respectively. At this temperature, the comprehensive score—based on drying time, specific energy consumption, damage rate, and the content of fatty acids, starch, polyphenols, and flavonoids—is maximized.

(3) The BP and MHP model can accurately predict the moisture variation of corn kernels under HAD and ID. However, the BP model exhibits superior adaptability to changes in drying methods and conditions, as it does not require parameter recalibration.

In this paper, the drying characteristics and quality variations of corn kernels under ID and HAD methods were investigated. However, numerical simulations to observe the internal temperature and moisture profiles were not conducted. The subsequent step will involve applying different pretreatment methods to corn kernels before drying to further increase the drying rate and improve energy efficiency. Numerical modeling will also be utilized to assist in elucidating the underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed phenomena.

Acknowledgement: The authors are grateful to the financial support for the work by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province.

Funding Statement: This study was financially supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (project No. 2024JJ8037: https://kjt.hunan.gov.cn/kjt/xxgk/tzgg/tzgg_1/202403/t20240311_33144606.html, accessed on 27 October 2025). The grant was received by the first author.

Author Contributions: The author confirms the following contributions to the paper: Study conception and design: Yang Liu; Data collection: Biao Chen, Xin Liu; Result analysis and interpretation: Yang Liu, Chenxi Luo; Manuscript preparation: Yang Liu, Shihui Xiao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the results of this study can be obtained from the corresponding author Xiao Shihui upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Nomenclature

| DR | Drying rate, g/(g∙h) |

| M | Moisture content, % |

| m | Mass, kg |

| Me | Equilibrium moisture content, % |

| MR | Moisture ratio |

| N | Number of observation |

| n | Number of constants in the model |

| R2 | Coefficient of determination |

| RMSE | Root mean square error |

| t | Drying time, s |

| χ2 | Chi square value |

| Δt | Time interval |

| Subscripts | |

| i | i-th |

| m | Mass |

| pre | Predicted |

| t | Time |

References

1. Fernandez Aulis F. Extraction and identification of anthocyanins in corn cob and corn husk from Cacahuacintle maize. J Food Sci. 2019;84(5):954–62. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.14589. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Miano AC, Ibarz A, Augusto PED. Ultrasound technology enhances the hydration of corn kernels without affecting their starch properties. J Food Eng. 2017;197(2):34–43. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2016.10.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Guo X, Hao Q, Qiao X, Li M, Qiu Z, Zheng Z, et al. An evaluation of different pretreatment methods of hot-air drying of garlic: drying characteristics, energy consumption and quality properties. LWT. 2023;180(6):114685. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2023.114685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. El-Mesery HS, Farag HA, Kamel RM, Alshaer W. Convective hot air drying of grapes: drying kinetics, mathematical modeling, energy, thermal analysis. J Therm Anal Calorim. 2023;148(14). [Google Scholar]

5. Li X, Yi J, He J, Dong J, Duan X. Comparative evaluation of quality characteristics of fermented napa cabbage subjected to hot air drying, vacuum freeze drying, and microwave freeze drying. LWT. 2024;192(3):115740. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2024.115740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wei S, Xie W, Zheng Z, Ren L, Yang D. Numerical study on drying uniformity of bulk corn kernels during radio frequency-assisted hot air drying. Biosyst Eng. 2023;227(4):117–29. doi:10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2023.01.020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Wang X, Wang Y, Zhao H, Tao H, Gao W, Wu Z, et al. Influence of hot-air drying on the starch structure and physicochemical properties of two corn cultivars cultivated in East China. J Cereal Sci. 2023;114(1):103796. doi:10.1016/j.jcs.2023.103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Elqadhi MER, Škrbić SV, Mohamoud OA, Ašonja AN. Energy integration of corn cob in the process of drying the corn seeds. Therm Sci. 2024;28(4 Part B):3325–36. [Google Scholar]

9. Zhang D, Huang D, Zhang Y, Lu Y, Huang S, Gong G, et al. Ultrasonic assisted far infrared drying characteristics and energy consumption of ginger slices. Ultrason Sonochem. 2023;92(10):106287. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Handayani S, Mujiarto I, Siswanto A, Ariwibowo D, Atmanto I, Mustikaningrum M. Drying kinetics of chilli under sun and microwave drying. Mater Today Proc. 2022;63(2):S153–S8. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.02.119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Liu Z-L, Xie L, Zielinska M, Pan Z, Deng L-Z, Zhang J-S, et al. Improvement of drying efficiency and quality attributes of blueberries using innovative far-infrared radiation heating assisted pulsed vacuum drying (FIR-PVD). Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2022;77(8):102948. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2022.102948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Barba FJ, Rajha HN, Debs E, Abi-Khattar A-M, Khabbaz S, Dar BN, et al. Optimization of polyphenols’ recovery from purple corn cobs assisted by infrared technology and use of extracted anthocyanins as a natural colorant in pickled turnip. Molecules. 2022;27(16):5222. doi:10.3390/molecules27165222. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Bassey EJ, Cheng J-H, Sun D-W. Improving drying kinetics, physicochemical properties and bioactive compounds of red dragon fruit (Hylocereus species) by novel infrared drying. Food Chem. 2022;375(22):131886. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131886. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Xu Y, Liu W, Li L, Cao W, Zhao M, Dong J, et al. Dynamic changes of non-volatile compounds and evaluation on umami during infrared assisted spouted bed drying of shiitake mushrooms. Food Control. 2022;142(3):109245. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2022.109245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Chao E, Li J, Fan L. Enhancing drying efficiency and quality of seed-used pumpkin using ultrasound, freeze-thawing and blanching pretreatments. Food Chem. 2022;384(12):132496. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2022.132496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Senadeera W, Adiletta G, Önal B, Di Matteo M, Russo P. Influence of different hot air drying temperatures on drying kinetics, shrinkage, and colour of persimmon slices. Foods. 2020;9(1):101. doi:10.3390/foods9010101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Mondal MHT, Akhtaruzzaman M, Sarker MSH. Modeling of dehydration and color degradation kinetics of maize grain for mixed flow dryer. J Agric Food Res. 2022;9(3):100359. doi:10.1016/j.jafr.2022.100359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Kusuma HS, Al Lantip GI, Mutiara X, Iqbal M. Evaluation of mini bibliometric analysis, moisture ratio, drying kinetics, and effective moisture diffusivity in the drying process of clove leaves using microwave-assisted drying. Appl Food Res. 2023;3(1):100304. doi:10.1016/j.afres.2023.100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang J, Zheng X, Xiao H, Shan C, Li Y, Yang T. Quality and process optimization of infrared combined hot air drying of yam slices based on BP neural network and Gray Wolf algorithm. Foods. 2024;13(3):434. doi:10.3390/foods13030434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang H, Che G, Wan L, Wang X, Tang H. Combination of LF-NMR and BP-ANN to monitor the moisture content of rice during hot-air drying. J Food Process Eng. 2022;45(9):e14102. doi:10.1111/jfpe.14102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jindal V, Siebenmorgen T. Effects of oven drying temperature and drying time on rough rice moisture content determination. Trans ASAE. 1987;30(4):1185–92. doi:10.13031/2013.30542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Kalman H. Effect of moisture content on flowability: angle of repose, tilting angle, and Hausner ratio. Powder Technol. 2021;393:582–96. doi:10.1016/j.powtec.2021.08.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yu J, Huang D, Ling X, Xun C, Huang W, Zheng J, et al. Drying kinetics of camellia oleifera seeds under hot air drying with ultrasonic pretreatment. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;222(18):119467. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Doymaz I. Air-drying characteristics of tomatoes. J Food Eng. 2007;78(4):1291–7. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.12.047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Lin Y, Yu J, Huang D, Chen Y, Fu Y, Zhang L, et al. The effect of ultrasonic pretreatment on the drying kinetics of orange peels under different drying methods. Ind Crops Prod. 2025;233(5):121479. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2025.121479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Pei J, Huang D, Fu Y, Huang S, Zhang L, Ren H, et al. Drying performance of Gastrodia elata by intermittent microwave combined with hot air drying. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2025;165(1):109089. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2025.109089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wei S, Chen P, Xie W, Wang F, Yang D. Prediction of stress cracks in corn kernels drying based on three-dimensional heat and mass transfer. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2019;35(23):296–304. [Google Scholar]

28. Hao Q, Qiao X, ZhengZ-J, Lu X. Effects of ultrahigh pressure and ultrasound pretreatments on hot-air drying process and quality of garlic slices. Trans Chin Soc Agric Eng. 2021;37:278–86. [Google Scholar]

29. Ren G, Zeng F, Duan X, Liu W, Yan S. Analysis of internal moisture changes in corn dry process investigated by low field-NMR. J Chin Cereals Oils Assoc. 2016;31(8):95–9. [Google Scholar]

30. Charmongkolpradit S, Somboon T, Phatchana R, Sang-aroon W, Tanwanichkul B. Influence of drying temperature on anthocyanin and moisture contents in purple waxy corn kernel using a tunnel dryer. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2021;25(2):100886. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2021.100886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Timm NDS, Lang GH, Ramos AH, Pohndorf RS, Ferreira CD, Oliveira MD. Effects of drying methods and temperatures on protein, pasting, and thermal properties of white floury corn. J Food Process Preserv. 2020;44(10):e14767. doi:10.1111/jfpp.14767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Wang C, Kou X, Zhou X, Li R, Wang S. Effects of layer arrangement on heating uniformity and product quality after hot air assisted radio frequency drying of carrot. Innov Food Sci Emerg Technol. 2021;69(8):102667. doi:10.1016/j.ifset.2021.102667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Yu J, Huang D, Chen Y, Xun C, Fu Y, Tang R, et al. Drying characteristics of blueberries by blanching water combined with ultrasonic pretreatment and convolutional neural network modeling. Int Commun Heat Mass Transf. 2025;169(5):109576. doi:10.1016/j.icheatmasstransfer.2025.109576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Batista AS, Souza MF, Prado MM. Moisture diffusion in passion fruit seeds under infrared drying. Diffus Found Mater Appl. 2022;30:25–32. doi:10.4028/p-w52h5b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Page GE. Factors influencing the maximum rates of air drying shelled corn in thin layers [master’s thesis]. West Lafayette, IN, USA: Purdue University; 1949. [Google Scholar]

36. Sharaf-Eldeen YI, Blaisdell J, Hamdy M. A model for ear-corn drying. Trans ASAE. 1981;23(5):1261–65. doi:10.13031/2013.34757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. O’callaghan J, Menzies D, Bailey P. Digital simulation of agricultural drier performance. J Agric Eng Res. 1971;16(3):223–44. doi:10.1016/s0021-8634(71)80016-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Degirmencioglu A, Yagcioglu K, Cagatay F. Drying characteristic of laurel leaves under different conditions. In: Proceedings of the 7th International Congress on Agricultural Mechanization and Energy; 1999 May 26–27; Adana, Turkey. p. 565–9. [Google Scholar]

39. Hendreson S, Pabis S. Grain drying theory. I. Temperature effect on drying coefficients. J Agric Eng Res. 1961;6:169–74. [Google Scholar]

40. Verma LR, Bucklin R, Endan J, Wratten F. Effects of drying air parameters on rice drying models. Trans ASAE. 1985;28(1):296–301. doi:10.13031/2013.32245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Midilli A, Kucuk H, Yapar Z. A new model for single-layer drying. Dry Technol. 2002;20(7):1503–13. doi:10.1081/drt-120005864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Jiang D, Liu Y, Lin Z, Wang W, Zheng Z. Effects of combined infrared and hot-air drying on ginsenosides and drying characteristics of Panax notoginseng (Araliaceae) roots. Int J Agric Biol Eng. 2022;15(1):267–76. doi:10.25165/j.ijabe.20221501.6210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Çetin N, Ciftci B, Kara K, Kaplan M. Effects of gradually increasing drying temperatures on energy aspects, fatty acids, chemical composition, and in vitro ruminal fermentation of acorn. Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2023;30(8):19749–65. doi:10.1007/s11356-022-23433-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Zhang D, Ji H, Liu S, Gao J. Similarity of aroma attributes in hot-air-dried shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) and its different parts using sensory analysis and GC–MS. Food Res Int. 2020;137:109517. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Ren L, Zheng Z, Fu H, Yang P, Xu J, Yang D. Hot air–assisted radio frequency drying of corn kernels: the effect on structure and functionality properties of corn starch. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;267:131470. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Cheng X-F, Zhang M, Adhikari B. The inactivation kinetics of polyphenol oxidase in mushroom (Agaricus bisporus) during thermal and thermosonic treatments. Ultrason Sonochem. 2013;20(2):674–9. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.09.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools