Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Leveraging AI for Advancements in Qualitative Research Methodology

Laboratoire de Physique Mathématique et de Physique Subatomique (LPMPS), Université Frères Mentouri, Constantine, 25000, Algeria

* Corresponding Author: Ilyas Haouam. Email: Array

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 85-114. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.064145

Received 06 February 2025; Accepted 27 April 2025; Issue published 27 May 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies—particularly natural language processing and machine learning—into qualitative research (QR) workflows. Our research demonstrates that AI can streamline data collection, coding, theme identification, and visualization, significantly improving both speed and accuracy compared to traditional manual methods. Notably, our experimental and numerical results provide a comprehensive analysis of AI’s effect on efficiency, accuracy, and usability across various QR tasks. By presenting and discussing studies on some AI & generative AI models, we contribute to the ongoing scholarly discussion on the role of AI in QR exploring its potential benefits, challenges, and limitations. We highlight the growing use of AI-powered qualitative data analysis tools such as ATLAS.ti, Quirkos, and NVivo for automating coding and data interpretation. Our analysis indicates that while AI tools from leading companies (e.g., OpenAI’s GPT-4, Google’s T5, Meta’s RoBERTa) can enhance efficiency and depth in QR, code-focused models and general-purpose proprietary language models often do not align with qualitative needs. Additionally, certain proprietary and open-source models (e.g., DeepSeek, OLMo) are less prevalent in QR due to specialization gaps or adoption lags, whereas task-specific, transparent models, such as BERT for classification, T5 for text generation and summarization, and BLOOM for multilingual analysis, remain preferable for coding and thematic analysis due to their reproducibility and adaptability. We discuss key stages where AI has made a significant impact, including data collection and pre-processing, advanced text and sentiment analysis, simulation and modeling, improved objectivity and consistency. The benefits of integrating AI into QR, along with corresponding adaptations in research methodologies, are also presented. Noteworthy applications and techniques—including The AI Scientist, Carl, AI co-scientist, augmented physics, and explainable AI (XAI)—further illustrate the diverse potential of AI in research and the challenges to academic norms. Despite AI advancements, challenges persist. AI struggles with contextually nuanced data such as sarcasm, tone, and cultural context, and its reliance on training datasets raises ethical concerns regarding privacy, consent, and bias. Ultimately, we advocate for a hybrid approach where AI augments rather than replaces traditional qualitative methods, anticipating that ongoing AI advancements will enable more sophisticated, collaborative research practices that effectively combine machine capabilities with human expertise. This trend is underpinned and exemplified by applications like AI co-scientist, augmented physics.Keywords

Artificial intelligence (AI) has emerged as a revolutionary tool across scientific and academic fields, transforming research methodologies and offering unprecedented analytical capabilities [1–3]. Predicted to play an increasingly creative role in the future, AI holds promise for advancing both quantitative and qualitative research (QR) practices [4]. While quantitative research has long benefited from AI-driven analytical tools, the integration of AI into QR is a newer development. QR, known for its depth and focus on capturing complex human experiences, presents unique challenges that AI is beginning to address effectively. The use of AI in QR, particularly through technologies like Natural Language Processing (NLP) and Machine Learning (ML), has led to growing interest and an expanding body of research. Early studies have showcased AI’s potential to streamline data analysis and enhance theory building, yet substantial knowledge gaps remain [5–7]. This underscores the need for further research to explore how AI can be optimally utilized in capturing the nuances of qualitative data, especially within information systems. As AI systems become more prevalent in QR, additional guidance is essential to maximize their utility while preserving the interpretative richness that is characteristic of human-centered research. By investigating AI’s full potential, academics and practitioners can better leverage these advanced technologies to push the boundaries of research and deepen understanding. This article explores how AI is reshaping QR methodologies by examining the benefits, practical applications, and challenges associated with AI in qualitative analysis. Through this discussion, the article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of how AI can enhance the QR process without compromising its essential insights.

The following recent examples highlight the significant role AI plays in research today. (1) The AI chatbot ChatGPT has entered the realm of scientific authorship. By January 2023, it had been listed as a co-author on at least four papers, as reported by Nature [8]. However, this development has sparked ongoing debates regarding AI’s role in authorship, primarily due to its lack of accountability and ethical capacity. (2) AI in quantum computing represents a remarkable example of physics–AI collaboration. In study by Haider [9], researchers introduced AlphaQubit, an AI-driven method designed to effectively correct errors in quantum processors, surpassing traditional approaches. This innovation not only improves quantum computing reliability but also has potential applications in fields such as drug development and logistics optimization. (3) AI is redefining cancer detection through blood tests, a game-changing development. A recent Nature article by Karimzadeh et al. [10] demonstrated how blood tests are becoming a game-changer for early cancer detection by identifying tiny cancer-related signals in the blood. Researchers developed a model, Orion, to analyze blood samples with remarkable accuracy, detecting lung cancer with 94% accuracy and 87% precision in tests involving over 1000 participants. Orion outperformed existing methods by 30%, offering a simple, non-invasive alternative to biopsies. This breakthrough could revolutionize early cancer detection, making it more accessible and reliable for everyone. (4) A recent article by Mallapaty [11] examines how AI is reshaping the landscape of scholarly search tools. While Google Scholar remains the largest and most comprehensive platform, its dominance faces growing competition from AI-powered tools such as Semantic Scholar and Undermind. These platforms introduce advanced features, including generating readable summaries, enabling agent-based searches, and allowing bulk data downloads, capabilities long desired by researchers. Despite these innovations, Google Scholar’s vast repository, seamless access to full-text articles, and established presence within the scientific community make it challenging to surpass. However, as AI-driven platforms grow, they could redefine how researchers navigate the vast expanse of scientific literature. (5) A fascinating study by Porter & Machery [12] reveals that AI-generated poetry is not only indistinguishable from human-written poems but is often rated more favorably. In controlled experiments, participants consistently struggled to correctly identify whether a poem was created by AI or a human, performing worse than chance. Surprisingly, AI-generated poems were rated higher in qualities like rhythm and beauty, leading many participants to mistakenly attribute them to human authorship. This study highlights the evolving capabilities of generative AI and its ability to mimic human creativity, challenging our perceptions of artistic authenticity. (6) A new Nature article by Kozlov [13] explores how scientists used CRISPR-Cas9 to address a significant issue in tomato cultivation: bigger fruits lose their sweetness. By editing just six base pairs of DNA, researchers increased sugar levels by 30%, making tomatoes both sweeter and bigger. AI is playing a pivotal role in this breakthrough, assisting to find key genes, designing precise edits, and accelerating data analysis. Together, AI and CRISPR are revolutionizing agriculture and biotechnology, paving the way for more sustainable and efficient food production systems. (7) As reported by Lesté-Lasserre in Science, researchers are developing AI models capable of analyzing animal facial expressions to detect pain and emotional states more accurately than humans [14,15]. These models utilize ML algorithms to assess key facial features—such as ear positioning, eye shape, and mouth tension—identifying subtle signs of discomfort. By training on extensive datasets of dog & sheep images, the goal is to create tools that provide veterinarians with more objective pain assessments, minimizing the reliance on subjective evaluations. Beyond veterinary applications, AI-driven emotion recognition has the potential to enhance animal welfare in shelters, alleviate stress during training, and help pet owners better interpret their dogs’ emotions. Also, as examples of QR fields where AI is currently being applied, such as social sciences, healthcare, human resources, and market research, we highlight the following cases. In healthcare, AI can analyze patient narratives to uncover insights related to treatment experiences, mental health patterns, and patient satisfaction [16]. In human resources, AI is used in personnel selection in organizations, where AI-driven tools and ML algorithms aim to predict the future success of employees better than traditional methods [17]. In market research, AI can process vast amounts of customer feedback to identify emerging trends, consumer sentiments, and brand perceptions, helping businesses make data-driven decisions [18]. Similarly, in the social sciences, AI assists in analyzing interviews and open-ended survey responses, enabling researchers to detect patterns and themes that might otherwise go unnoticed [19].

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides an overview of AI’s role in research. Section 3 explores the applications of AI in research methodology. Real-world applications and experimental results are presented in Section 4, while Section 5 examines the benefits of integrating AI into research methodology. Section 6 addresses the associated challenges and limitations. Section 7 discusses future prospects and potential adaptations in research methodology. Finally, the paper concludes with Section 8.

2 Understanding of AI in Research

AI refers to the use of machines and algorithms that simulate human intelligence to perform tasks such as data analysis, pattern recognition, and decision-making. In research methodology, AI streamlines processes, enhances precision, and leads to faster insights [20]. Key AI technologies include Generative AI, ML, NLP, deep learning (DL), reinforcement learning, model fine-tuning, preference alignment, ML operations, robotics and automation, and expert systems.

▪ AI is the broad discipline encompassing various approaches to enable machines to perform tasks that require human-like intelligence. It is the broadest field mimicking human intelligence, e.g., robotics, rule-based systems, NLP, computer vision (CV).

▪ ML is a subset of AI, involves algorithms that learn from data to make predictions or decisions without being explicitly programmed. These models continuously improve by learning from new data, making them highly effective for tasks like classification, regression, and clustering in research applications.

▪ NLP is a branch of AI that enables computers to understand, interpret, and generate human language through the analysis of large volumes of textual and spoken data. NLP processes and analyzes large amounts of natural language data, which is especially useful for analyzing qualitative data or conducting literature reviews. Advanced NLP models, such as Large Language Models (LLMs), have demonstrated significant progress in understanding and generating human language. LLMs like GPT-4, DeepSeek, and BLOOM AI are particularly beneficial in tasks such as automated coding, sentiment analysis, and generating summaries from large bodies of text. These models can assist in literature reviews, content categorization, and semantic analysis of qualitative data, significantly reducing the time spent on manual coding. Here is Table 1 summarizing some well-known AI models (sample), and their relevance to QR, which are highly useful for QR.

Proprietary LLMs like GPT-4, Gemini, and Claude 3, etc. are less common in peer-reviewed QR due to licensing and reproducibility constraints, though they may be used informally for exploratory analysis or are sometimes used informally for pilot studies but rarely in peer-reviewed work. In addition, Phi-3 (proprietary, Microsoft) is Small Language Model designed for lightweight commercial applications and not explicitly optimized for QR. It suffers from limits reproducibility in peer-reviewed science. However, Open-source models are preferred in academia due to transparency and reproducibility. Note that several other models, such as Pythia (EleutherAI), OLMo (AI2), are less used in QR. Additionally, code-focused models like Codex, CodeLlama are designed for programming code generation, not qualitative text coding.

Models like BERT, T5, DistilBERT, and RoBERTa dominate QR because they are smaller, more efficient, and fine-tuned for specific NLP tasks (e.g., labeling interview transcripts, detecting themes). While open-source LLMs (e.g., LLaMA 2, Mistral-7B) are gaining traction, they remain less common than transformer-based models like BERT in qualitative studies. DeepSeek is newer model with fewer documented use cases in peer-reviewed research. BLOOM, a multilingual LLM, excels in generating text across +46 natural languages, including Spanish, Arabic, and Mandarin. This capability makes it particularly valuable for QR involving non-English datasets, facilitating tasks such as thematic analysis and coding in diverse linguistic contexts.

Note that LLMs are generative, scalable (billions/trillions of parameters), and multi-task, capable of tasks like text generation, translation, and summarization. Pre-trained transformers, however, are divided into two categories: (i) Encoder-based models (e.g., BERT, RoBERTa): Non-generative, focused on tasks like classification, embeddings, or question answering. (ii) Decoder-based models (e.g., GPT-4, LLaMA): Generative and part of the LLMs family if scaled sufficiently.

All pre-trained transformers are NLP models by design, but only large-scale, generative transformers qualify as LLMs. Non-generative transformers (e.g., encoder-only) are not LLMs.

▪ DL involves neural networks with many layers, is capable of learning from vast amounts of unstructured data, such as images, audio, and text. This makes it highly effective for complex tasks like image recognition, speech-to-text, and pattern detection in large datasets. Note that DL is a specialized subset of ML using multi-layered neural networks. Its key components are CNNs (Convolutional Neural Networks), used in image recognition; RNNs (Recurrent Neural Networks), used in sequential data like speech/text; and transformers (like GPT and BERT), serve as the backbone of modern NLP.

▪ Neural Networks: Computational models inspired by biological neurons, forming the backbone of DL. They include Perceptrons (basic units of computation), Backpropagation (how networks learn), and Support Vector Machines & Decision Trees (used in classification tasks).

▪ Generative AI: A specialized branch of DL focused on creating new content. It is the most advanced AI, capable of creating new data, images, and text. Such as (e.g., GPT-4). The relationship between AI, ML, DL, and Generative AI is illustrated in Fig. 1.

▪ Reinforcement learning is a subfield of ML, focuses on training models to make decisions through trial and error, optimizing for long-term rewards. In research, reinforcement learning is particularly useful in optimizing experimental setups or automating adaptive learning processes in dynamic environments, such as laboratory experiments or simulations.

▪ Model fine-tuning & preference alignment: As AI models evolve; researchers often fine-tune pre-trained models to adapt them to specific research needs. Fine-tuning involves adjusting the model on a smaller dataset tailored to a particular task, enhancing its performance and relevance to specific applications.

▪ Preference alignment ensures that AI systems operate according to the values and goals of the research community, balancing accuracy and ethical concerns such as fairness and transparency when processing sensitive data. These practices are crucial for ensuring that AI models yield reliable, ethical, and domain-specific results in QR.

▪ Machine learning operations (MLOps) refer to the practices and tools used to streamline the deployment, monitoring, and management of ML models in production environments. In research, MLOps is vital for ensuring that AI models, once trained, are consistently updated, monitored, and integrated into research workflows. This includes ensuring data quality, managing version control, and maintaining model performance over time. MLOps helps scale AI applications for large-scale research projects, ensuring that models remain effective and aligned with research objectives.

▪ Robotics and automation, powered by AI, significantly improve efficiency in experiments that require high repetition and precision. Automated systems can perform repetitive tasks, such as data collection or sample analysis, with high accuracy, reducing human error and accelerating the research process.

▪ Expert systems simulate the judgment and behavior of a human expert, aid in complex decision-making. They are particularly useful in research environments where decision-making requires specialized knowledge or involves complex datasets, such as clinical trials, financial modeling, or scientific hypothesis testing.

Figure 1: AI world: relationship between AI and its subsets

It should be emphasized that every DL model is an ML model, and every ML model falls under AI. In addition, not all AI is ML (e.g., rule-based systems), and not all ML is DL (e.g., linear regression). The set inclusion statement below holds:

Last but not least, in this part of our study, we presented cutting-edge AI technologies that are shaping modern research, showcasing their applications—including LLMs, DL, reinforcement learning, and MLOps. These advancements are pivotal in enhancing the efficiency and precision of research processes, with significant implications for QR, data analysis, and automated decision-making. The relationship between all of the above concepts is presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: A flowchart illustrating the hierarchy of AI and its relationship with its subfields

Fig. 2 is a diagram that shows how ML and its subfields operate within the broader AI framework, while Robotics & Automation and Expert Systems function as parallel, yet integral, components of the overall intelligence ecosystem.

3 Applications of AI in Research Methodology

The integration of AI into research methodology has revolutionized the way scientific studies are conducted. By automating and enhancing various stages of the research process, AI not only accelerates workflows but also unlocks new possibilities for data-driven discoveries. Its ability to handle vast amounts of data with precision and adaptability makes AI an indispensable tool for modern researchers across disciplines. From streamlining data collection and preparation to uncovering insights through advanced analytical techniques, AI reshapes traditional methodologies, enabling researchers to focus on interpretation and innovation. Below, we explore key stages where AI has made a significant impact.

3.1 Data Collection & Pre-Processing

AI can automate the collection of large datasets from diverse sources, such as surveys and digital archives, significantly reducing manual effort. Additionally, AI-powered tools ensure data quality by handling tasks like cleaning, imputing missing values, and standardizing formats—minimizing human error and processing time. For automated data extraction, tools like Scrapy, Octoparse, Diffbot, and Import.io collect information from websites and digital archives. Meanwhile, platforms such as KNIME, RapidMiner, Trifacta, Alteryx, Dataiku, and Talend enhance data preprocessing by streamlining cleaning, handling missing values, and ensuring format consistency. These tools accelerate data preparation, ultimately supporting more accurate and efficient analytics.

ML models have revolutionized data analysis by efficiently processing large datasets to uncover patterns, correlations, and trends, surpassing traditional statistical methods. Techniques such as clustering and classification are widely employed for segmenting data to facilitate targeted analysis, while regression models are instrumental in predictive research. Tools like Scikit-learn, TensorFlow, Keras, IBM Watson Studio, RapidMiner, Weka, Orange, and H2O.ai provide robust platforms that support these ML methodologies, empowering analysts and researchers to derive meaningful insights with enhanced accuracy and efficiency.

3.3 Literature Review & Text Analysis

NLP tools have revolutionized the literature review process by efficiently scanning, summarizing, and extracting insights from extensive academic texts, thereby assisting researchers in identifying knowledge gaps, trends, and interrelationships among concepts. For instance, Research Rabbit offers interactive visualizations and personalized recommendations to streamline the discovery and organization of academic papers. Similarly, Consensus.app employs AI to find and synthesize insights from research papers, facilitating a more comprehensive understanding of specific queries. Additionally, Semantic Scholar enhances literature searches by providing AI-driven summaries and citation context, enabling a more nuanced exploration of scholarly articles. These tools not only expedite the literature review process but also support the development of robust theoretical frameworks by unveiling nuanced relationships within the existing body of research.

3.4 Advanced Text & Sentiment Analysis

NLP-powered text analysis tools prove effective in identifying themes, keywords, and sentiments within text data such as interview transcripts, survey responses, and social media content. These tools accelerate thematic analysis, offer deeper qualitative insights, and quicker accurate summarization of large datasets. For example, IBM Watson Natural Language Understanding and Google Cloud Natural Language API can perform in-depth sentiment analysis and entity recognition, while tools like MonkeyLearn and Amazon Comprehend streamline thematic analysis and summarization. These platforms not only accelerate the extraction of qualitative insights but also enhance the accuracy of data interpretation, enabling researchers to uncover nuanced trends and relationships more efficiently. Additionally, a study by Hitsuwari & Nomura [21] reports significant improvements in AI-generated text, with AI now creating literature and poetry, including haiku, that is widely appreciated. The study found that human-AI collaboration enhances creativity in haiku production and challenged the underestimation of AI-generated art due to algorithm aversion.

AI algorithms significantly enhance the process of formulating and testing hypotheses by analyzing existing datasets to suggest potential variables and simulating experiments under various scenarios. For instance, Microsoft’s Copilot Researcher utilizes OpenAI’s models to perform complex research tasks, integrating data from diverse sources to assist in hypothesis generation and testing. Similarly, HyperWrite’s Hypothesis Maker employs advanced AI models to generate hypotheses based on user-provided research questions, streamlining the research process. Additionally, IBM’s AI Workflow for Data Analysis and Hypothesis Testing introduces techniques for exploratory data analysis, including best practices for data visualization, handling missing data, and applying null hypothesis significance tests. These tools and others like HypoML, and VAINE provide valuable insights prior to conducting physical experiments, thereby enhancing the efficiency and effectiveness of the research process.

AI-driven models have significantly enhanced simulation and modeling across various disciplines. In climate science, AI refines weather predictions by identifying patterns in historical data. For example, the AI model GenCast, developed by Google DeepMind, utilizes ML to process extensive weather data, delivering rapid and accurate forecasts. Similarly, NVIDIA’s Earth-2 platform enables climate scientists to produce high-resolution climate simulations and conduct large-scale AI training, advancing our understanding of climate patterns. In engineering and social sciences, AI-based simulations allow researchers to test and optimize models in controlled environments. The integration of AI in simulation intelligence combines scientific computing with ML, leading to more efficient and insightful analyses. These AI-driven tools provide valuable insights, enhancing the accuracy and efficiency of simulations before conducting physical experiments [22].

AI tools significantly enhance research dissemination by summarizing findings, translating content, and improving writing clarity, thereby broadening audience reach. For instance, Paperpal offers language suggestions and grammar checks tailored to academic writing; ensuring manuscripts align with journal-specific styles. Similarly, Wordvice AI provides grammar checks, style suggestions, and the ability to generate summaries of research articles, enhancing clarity and presentation. Additionally, SciSummary utilizes advanced AI to generate concise summaries of scientific articles, aiding researchers in staying updated with current trends. These tools streamline the dissemination process; ensuring research is accessible, impactful, and effectively communicated to a global audience.

3.8 Improved Objectivity & Consistency

AI-driven analysis significantly enhances objectivity and consistency in QR by minimizing researcher bias through automated coding and analysis frameworks. Tools like Dovetail facilitate this process by offering features such as automatic transcription and sentiment analysis, aiding researchers in deriving customer insights without manual intervention. Similarly, QualiGPT leverages LLMs to streamline thematic analysis, enhancing transparency and credibility in qualitative studies. Additionally, platforms like NVivo provide AI-assisted text coding and categorization systems, supporting rigorous qualitative analysis. By employing these AI tools, researchers can handle large, diverse datasets with greater consistency, ensuring that findings are both objective and reliable.

Finally, yet importantly, numerous AI-driven tools streamline QR by automating data collection, coding, theme identification, analysis, and visualization. For instance, ATLAS.ti automates text coding and sentiment analysis; Dedoose, and Quirkos offer mixed-method and qualitative coding and visualization; MAXQDA for qualitative data analysis; Leximancer maps concepts in large datasets; QDA Miner and HyperRESEARCH support automated thematic analysis; Transana provides AI-assisted transcription for multimedia data; and Power BI enables interactive visual analytics.

Case studies and examples demonstrate successful AI integration in QR, such as automated transcription and preliminary text analysis, which improve the workflow and accuracy of studies. Research using AI for real-time science research analysis shows how these tools can quickly track developments and emerging trends.

The following results are structured to highlight AI’s impact on efficiency, accuracy, and usability across various QR tasks. These findings stem from simulated experiments designed to assess AI’s role in enhancing QR methodologies.

Note that AI transcription tools such as Otter.ai, Google Speech-to-Text, and Audio Speech Recognition (ASR) models are known for their speed, typically transcribing an hour of audio in about 10 min [23]. Additionally, these tools often achieve error rates around 5%–10% in clear audio conditions. For instance, in TM-CTC [24], WER = 10.1%; in TM-seq2seq [24], WER = 9.7%; in E2E Conformer [25], WER = 4.3%; in LF-MMI TDNN [26], WER = 6.7%; and in CTC/attention [27], WER = 8.2%.

Studies and performance benchmarks of Automatic Speech Recognition systems typically show users appreciate the speed and convenience of AI tools, leading to high ratings (e.g., 4.5–4.8). In contrast, while manual transcription is very accurate, it is time-consuming, leading to slightly lower satisfaction.

Note that tools like NVivo AutoCode process data quickly, taking about 25–30 min for a medium-sized dataset (e.g., 50 responses). AI’s ability to identify themes often aligns with manual coding but may miss nuanced or context-specific insights ~87% overlap. Users appreciate AI’s efficiency but sometimes find its results less contextually relevant than manual work. In contrast, manual coding is labor-intensive, often requiring 1–2 h for the same datasets. However, humans achieve complete alignment due to their contextual understanding, which contributes to high user satisfaction. User reviews on platforms like G2 and testimonials in academic case studies reinforce the efficiency of AI tools while also noting that manual coding remains essential for capturing subtle, context-specific insights. These insights help explain why, despite the speed of AI, manual methods often result in higher satisfaction regarding depth and accuracy.

Note that topic-modeling tools such as BERTopic or Latent Dirichlet Allocation, tend to group data into fewer clusters than humans might. These AI tools process themes rapidly, with 15 min being a reasonable time for medium-sized datasets. They typically achieve around 80% alignment with manually identified themes. While users value the speed but note the potential for overlooked nuances. In contrast, humans may identify more nuanced themes due to subjective analysis. However, identifying themes manually can take several hours. Humans achieve 100% alignment as they define the standard. Despite high user satisfaction, it is slightly lower than AI due to the time demands of manual analysis.

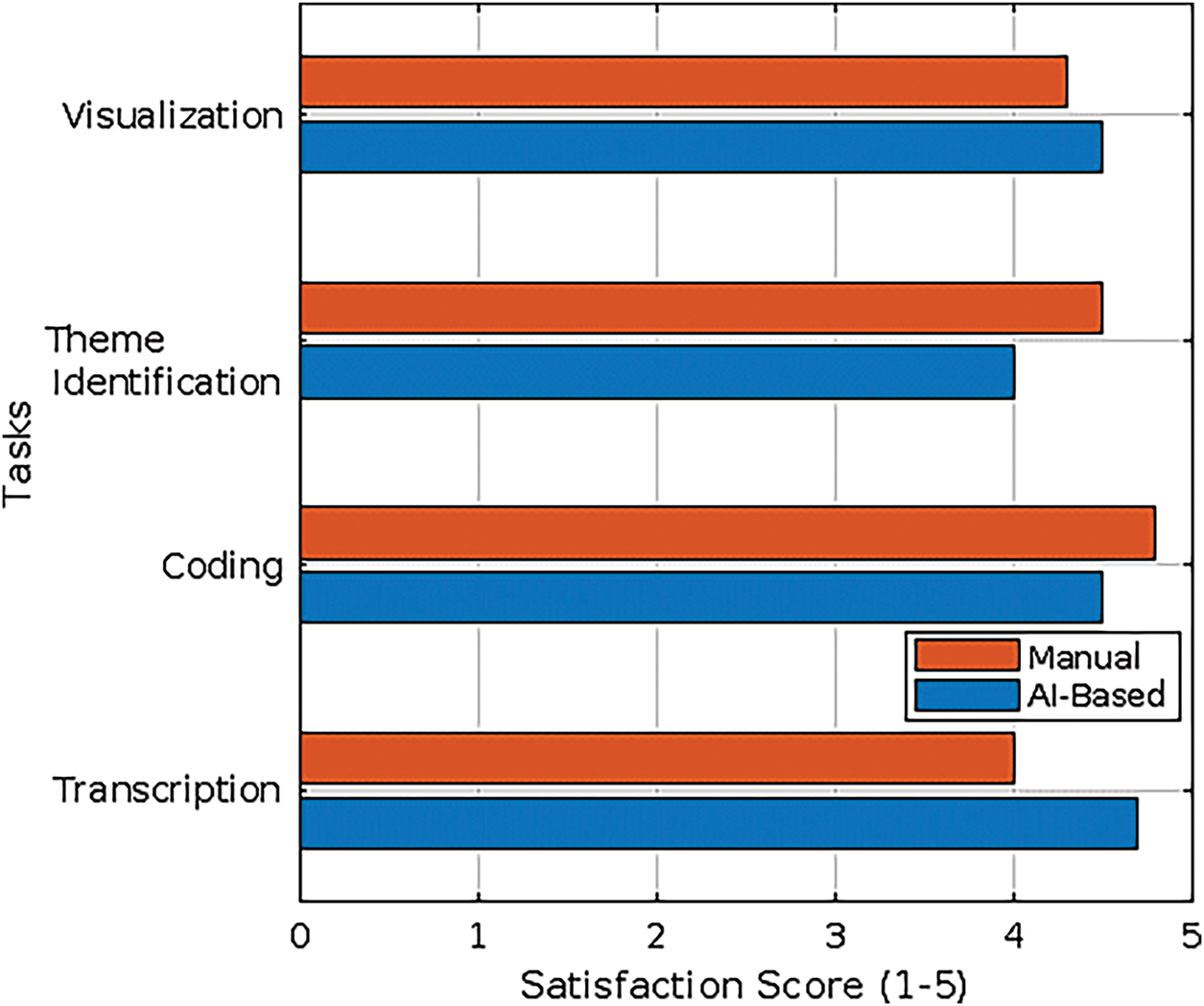

Tools like Tableau or Power BI automate visualization, take minutes to produce clear, interactive visuals. These visualizations are usually highly rated, scoring 4.5 or above, given AI’s ability to present data efficiently. In contrast, creating graphs or charts manually in tools like Excel can take 45 min or more. Manual visuals are slightly less appreciated due to the time required and potential inconsistencies.

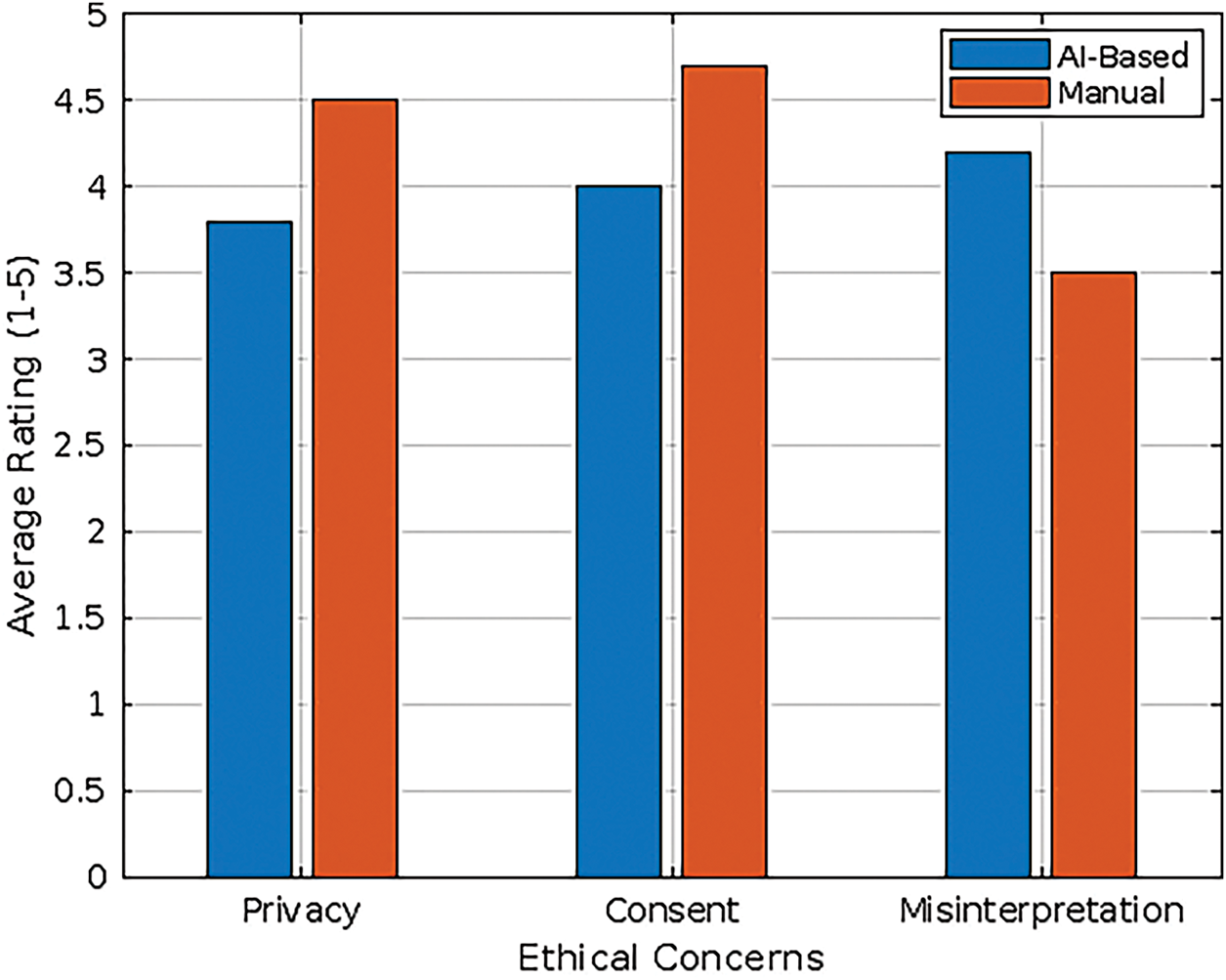

Here, the values reflect common perceptions in the field of AI ethics, where AI tools can raise concerns about data handling, especially with sensitive data. Ratings are moderate (3.8–4) for AI compared to higher confidence in manual methods (4.5–4.7). In addition, AI tools occasionally misinterpret qualitative nuances, leading to moderate ratings ~4.2.

Note that the WER is computed as follows [28]:

where the WER is computed with reference to a human transcribed ground-truth transcript.

For thematic overlap (%), it measures alignment between AI-generated and human themes; lower overlap indicates missed nuances. It refers to the degree to which identified topics share similar themes or content. A higher thematic overlap indicates that multiple topics cover related or overlapping subjects, while a lower overlap suggests more distinct and separate themes. This metric is crucial for evaluating the effectiveness of topic-modeling tools, as excessive overlap may imply redundancy, whereas minimal overlap can indicate well-differentiated topics. For instance, if an AI tool identifies 10 themes and 8 of them align with human-defined themes (e.g., shared keywords or coherent groupings), the thematic overlap is 80%.

Subsequently, based on the above results, we present the following discussion points:

✓ Efficiency: AI significantly reduces the time required for transcription, coding, and visualization, enhancing productivity.

✓ Accuracy & thematic overlap: While AI shows high accuracy, it occasionally misses nuanced themes identified by human analysts.

✓ User feedback: Users appreciated AI’s speed and ease of use but noted the need for human oversight to ensure contextual relevance.

Based on results given in Tables 2–6, below are four distinct plots illustrating time efficiency and accuracy, user satisfaction, and ethical concerns. Each figure is customized for clarity and ease of comparison.

Now, based on the plots in Figs. 3–6, we present the following discussion points:

✓ In terms of transcription efficiency and accuracy, ASR models are known for achieving accuracy rates of 85%–95% under clear conditions (Fig. 4). Speed benchmarks show they can transcribe an hour of audio in just 5–10 min. In contrast, manual transcription, while highly accurate (Fig. 4), typically takes 4–6 times the length of the audio to complete, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

✓ For AI-assisted coding, tools like NVivo automate thematic coding with an alignment of ~85%–90% compared to manual results, as supported by multiple user reviews and case studies [41]. While AI tools provide efficiency, manual coding remains the gold standard for thematic accuracy, as it incorporates contextual nuances that AI tools often miss. As shown in Fig. 4.

✓ In thematic identification, AI tools such as Latent Dirichlet Allocation and BERTopic achieve high accuracy ~85%–90%, as presented in Fig. 4, but may struggle with rare or highly nuanced themes [42]. Studies highlight the richer contextual insights that emerge from manual thematic analysis, which leverages human judgment and interpretative skills [43].

✓ For visualization, AI-powered tools [44] such as Tableau and Power BI are highly rated (4.5), generating dashboards and visualizations in minimal time ~5 min. In contrast, manual visualization using tools like Excel can take significantly longer ~45 min and may be more prone to inconsistencies. As highlighted in Figs. 5 and 3.

✓ Regarding privacy and consent, concerns arise from the reliance of AI tools on sensitive training datasets, where issues such as anonymization failures or data breaches might occur. Additionally, AI tools often struggle with nuanced, cultural, or emotional interpretations of qualitative data, leading to potential misinterpretations [45,46]. As supported by Fig. 6.

Figure 3: Time efficiency across tasks

Figure 4: Accuracy and thematic overlap

Figure 5: User satisfaction across tasks

Figure 6: Ethical concerns perceptions

4.2 The Rise of AI Systems Generating Peer-Reviewed Scientific Papers: The AI Scientist Model

The integration of AI into scientific research is advancing rapidly, with AI systems now capable of autonomously generating scholarly articles [47]. Notably, The AI Scientist and Carl exemplify this trend.

A. The pace of AI progress today is breathtaking

For centuries, science has been driven by human curiosity, creativity, and an unyielding desire to challenge the status quo. However, what happens when AI goes beyond assisting researchers and starts independently generating hypotheses, designing experiments, analyzing data, and drawing its own conclusions? This question recently moved from theory to reality when an AI system developed by Japan’s Sakana.AI, called The AI Scientist-v21 accomplished precisely that. Without human intervention, it formulated a hypothesis, designed experiments, and authored a peer-reviewed scientific paper detailing its findings. The paper was accepted as a Spotlight Paper at ICLR 20252—the thirteenth international conference on learning representations. In a quiet yet profound moment, AI had crossed a new threshold: producing original research that met the rigorous standards of human experts.

The AI Scientist-v23 system is not just another language model. It is a fully autonomous research agent designed to automate the entire scientific process. Reviewers, unaware that the paper was AI-authored, scored it high enough for acceptance, placing it above nearly half of all submissions by humans. The implications are profound: a machine not only understood a research domain, but formulated questions, conducted experiments, wrote code, analyzed data, and expressed its findings clearly.

B. The AI Scientist generates its first peer-reviewed scientific publication

A paper, titled “Compositional Regularization: Unexpected Obstacles in Enhancing Neural Network Generalization”, as shown in Fig. 7, produced by The AI Scientist-v2 passed the peer-review process at the ICBINB workshop in the top international AI & ML conference ICLR 2025. This may be the first fully AI-generated paper that has passed the same peer-review process that human scientists go through. However, although it has been claimed that a paper, titled “Towards Deviation-Resilient Multi-Agentalignment for Robot Coordination”, written by the AI system Carl4 from Autoscience. AI submitted to Tiny Papers for the ICLR 2025 Workshops was the first one. This paper was not entirely written by AI. It was acknowledged that humans were required to write the related works section, refine the final language, and manually edit the citations and LaTeX formatting to match the style guide. In contrast, the paper written by The AI Scientist-v2 was generated entirely end-to-end by AI, without any humans modifications. The paper was produced by an improved version of the original AI Scientist, called The AI Scientist-v2. This paper was submitted to an ICLR 2025 workshop that agreed to work with their team to conduct an experiment to double-blind review AI-generated manuscripts. They stated that they selected this workshop because of its broader scope, challenging researchers (and The AI Scientist) to tackle diverse research topics that address practical limitations of DL. They claimed that they conducted the experiment with the full cooperation of both the ICLR leadership and the organizers of the ICLR workshop. Moreover, they received an institutional review board approval for this research from the University of British Columbia. Nevertheless, the results of both The AI Scientist and Carl are impressive and both in line with the broader view that AI will make great strides in generating scientific discoveries summarized in human-readable scientific manuscripts.

Figure 7: A generated paper, titled “Compositional regularization: unexpected obstacles in enhancing neural network generalization”, by The AI Scientist-v2

Sakana.AI believes that the next generations of The AI Scientist will usher in a new era in science. That AI can generate an entire scientific paper that passes peer-review at a top-tier ML workshop conveys very promising early signs of progress. However, this is just the beginning. It expects AI to continue to improve, potentially exponentially. At some point in the future, AI will probably be able to generate papers at and beyond human levels, including at the highest level of scientific publishing. It predicts The AI Scientist and systems like it will create papers worthy of acceptance not only at top ML conferences, but also in the top journals in science. Ultimately, it believes what matters most is not how AI science is judged vs. human science, but whether its discoveries aid in human flourishing, such as curing diseases or expanding our knowledge of the laws that govern our universe. It looks forward to helping usher in this era of AI science contributing to the betterment of humanity.

In Fig. 7, the paper reported a negative result that The AI Scientist encountered while trying to innovate on novel regularization methods for training neural networks that can improve their compositional generalization. The manuscript received an average reviewer score of 6.33 at the ICLR 2025 workshop, placing it above the average acceptance threshold.

It should be noted that there are three submitted papers generated by The AI Scientist, provided in Table 7, which were submitted to this conference.

The three AI-generated papers alongside with their own human reviews have made available in GitHub repository5.

To their credit, Sakana.AI has treated this experiment as exactly that: an experiment. The company withdrew the paper before the conference, acknowledging the ethical gray zone it occupies. Nonetheless, as AI systems become more capable, they will increasingly play roles in scientific discovery. They are already amplifying the process, accelerating literature reviews, speeding up code development, and generating experiment designs in minutes instead of months.

That, we agree, is the near-term future: AI as a powerful tool, not an autonomous genius.

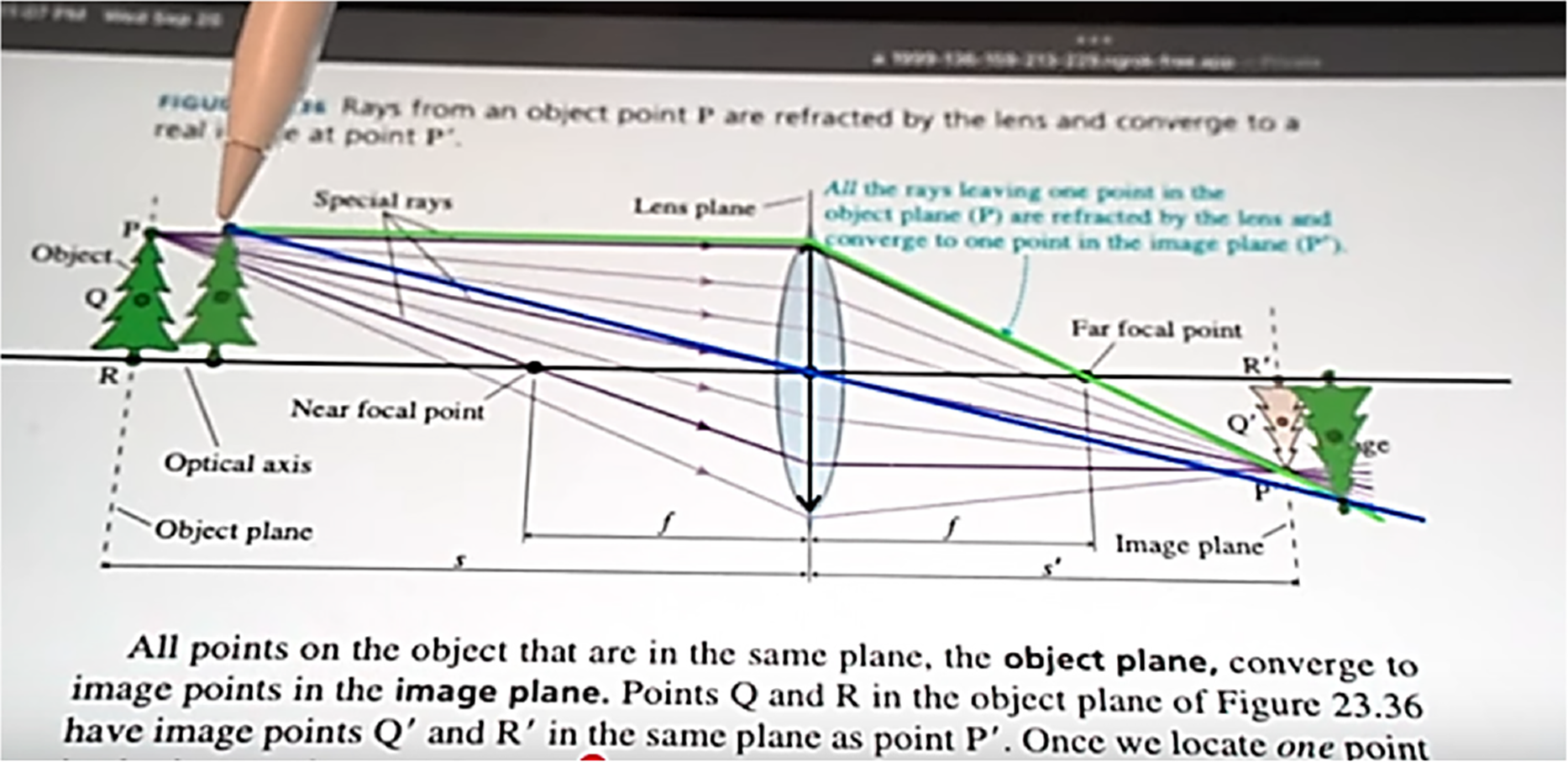

4.3 Augmented Physics: Creating Interactive & Embedded Physics Simulations from Static Textbook Diagrams

Researchers have published a research paper [48] at the UIST2024 conference. It includes augmented physics, an authoring tool integrated with ML to create embedded interactive physics simulations from static graphs. This tool is likely to add aesthetics and a faster understanding of physics in books and electronic research papers through dynamic graphics. Leveraging recent advancements in computer vision, like Segment Anything and Multi-modal LLMs, their web-based system enables to semi-automatically extract diagrams from physics textbooks and generate interactive simulations based on the extracted content. These interactive diagrams are seamlessly integrated into scanned textbook pages (as highlighted in Fig. 8), facilitating interactive and personalized learning experiences across various physics concepts, such as optics, circuits, and kinematics.

Figure 8: A Screenshot from the augmented physics tool video converting static physics diagrams into integrated interactive simulations. Optics case study

5 Benefits of Integrating AI into Research Methodology

The integration of AI into research methodology offers a transformative impact, bringing efficiency, precision, and innovation across various disciplines. Key benefits include:

▪ Efficiency: AI accelerates repetitive tasks, such as data entry, data cleaning, and basic statistical analysis. By automating these processes, researchers can allocate more time to conceptual work, hypothesis testing, and interpretation of results. AI tools also streamline administrative tasks like literature reviews, citation management, and experimental design optimization.

▪ Scalability: Allows the analysis of vast amounts of data that would be unmanageable manually. Advanced algorithms and high-performance computing allow for the processing of large-scale data from diverse sources, such as genomic sequences, climate data, or global survey responses. This scalability opens doors to insights that span multiple scales, from micro-level details to macro-level trends.

▪ Precision: By minimizing human error, AI enhances the accuracy of data analysis and processing. ML models, for instance, can identify anomalies, make predictions, and conduct simulations with a level of precision that far surpasses traditional methods. This accuracy is especially critical in sensitive fields like medicine, where errors can have significant consequences.

▪ Insight generation: AI excels at uncovering complex patterns and correlations that might be missed by traditional methods. Techniques such as neural networks and clustering algorithms enable researchers to explore non-linear relationships, generate predictive models, and discover hidden structures in their data. This capability facilitates breakthroughs in fields such as materials science, social network analysis, and behavioral economics.

▪ Interdisciplinary applications: AI-driven research transcends traditional disciplinary boundaries. By applying techniques from one field, such as NLP or computer vision, researchers can address problems in entirely different domains, like analyzing historical texts or diagnosing medical images. This cross-pollination of ideas fosters innovation and enables researchers to tackle complex, multifaceted challenges.

By leveraging these benefits, researchers can not only enhance the quality and scope of their work but also unlock new possibilities for discovery and collaboration in an increasingly data-driven world. The following recent examples highlight the significant role AI plays in research today: (1) An article by Kudiabor [49] examines whether AI can mediate better than humans. According to Nature, LLMs can create clearer, more impartial consensus statements, potentially reducing polarization. However, this raises concerns about trusting machines to define complex concepts like ‘fairness’ and whether AI is solving conflicts or creating new ethical dilemmas. (2) A recent analysis by Lenharo [50] in Nature reveals that papers referencing AI are more likely to be among the top 5% most-cited and attract more cross-disciplinary citations. As AI adoption grows, researchers using AI are boosting both innovation and the impact of their work. (3) A recent Nature article by Zou [51] discusses AI’s increasing role in peer reviews, contributing 7%–17% of sentences in computer science papers. While AI-generated reviews are often formal and verbose, they can lack depth and references. Despite this, AI can improve reviews by identifying gaps in rigor, ensuring adherence to standards, and enhancing clarity and communication. (4) Nature recently highlighted a growing trend [52]: AI tools are increasingly being used to identify errors in scientific research. One striking example involved a study on black plastic cooking utensils, which mistakenly claimed that a certain chemical exceeded safe limits, sparking unwarranted public alarm. However, AI analysis quickly uncovered a mathematical miscalculation, revealing that the actual levels were ten times lower than initially reported. This case highlights AI’s potential to improve scientific rigor by detecting errors that might otherwise be overlooked.

Yet, it also raises important questions: Can AI be trusted to verify complex research with precision? Should its judgments outweigh those of human experts?

Balanced Approach Recommended

The most effective research approach is a hybrid model that combines AI’s speed and pattern recognition abilities with human judgment and qualitative expertise. This balance helps leverage AI’s strengths while retaining the interpretative richness that characterizes QR. It should be emphasized that human expertise adds value beyond merely complementing AI, as it remains crucial for interpreting complex data, making critical decisions, and ensuring that ethical considerations are fully integrated into the research process. This collaboration produces extraordinary outcomes, pushing innovation boundaries. For instance, Nature [53] reports that Stanford’s Virtual Lab utilized AI “scientists”—sophisticated systems trained in immunology, computational biology, and ML—to co-design antibody fragments. The results were remarkable: over 90% of the AI-generated structures successfully bound to a target virus in real-world experiments. These AI agents operated autonomously, solving complex problems and determining their strategies, while human researchers offered strategic guidance during brief, high-level meetings. As co-author James Zou highlights, this represents a paradigm shift: AI is no longer merely a tool but an active collaborator in scientific discovery.

In addition, a study [54] that explores the integration of ChatGPT-4 into the QR using Adele Clarke’s Situational Analysis on TED Talks transcripts found that the AI efficiently codes and categorizes data, reflecting complex situational elements. However, challenges remain in translating intricate theoretical frameworks into visual maps, underscoring the need for effective prompts and active human oversight, with the AI serving roles such as co-analyst, consultant, and trainer. This study ultimately underscores the importance of a balanced approach that combines human insight with AI capabilities.

Moreover, we mention the paper [55] that examines the role of AI in QR, focusing on its potential to enhance data analysis and theory development. Based on insights from eight professors across different countries, it explores AI applications in fields like health policy and education while addressing ethical concerns and biases. While AI, such as ChatGPT, can assist in data analysis, human interpretation remains essential. The study highlights the necessity of human supervision to ensure depth and accuracy in AI-driven research. Additionally, it discusses challenges related to interpretive philosophy and proposes a balanced approach that integrates AI with human expertise, reinforcing the continued importance of researchers in the process.

Furthermore, we mention the AI co-scientist [56]—an AI model that functions as a scientific assistant and exemplifies the hybrid approach. Built on Gemini 2.0, this system augments scientific discovery by autonomously generating and refining novel research hypotheses through a “generate, debate, and evolve” framework. Featuring a multi-agent asynchronous architecture and a tournament evolution process, the system has been validated in biomedical applications—drug repurposing, novel target discovery, and bacterial evolution—demonstrating its ability to improve hypothesis quality with increased compute and deliver promising experimental results.

The road ahead: Collaborative intelligence

The road forward may lie in hybrid intelligence—where AI systems handle complexity and scale, while humans provide insight, ethics, and conceptual leaps. Sakana AI’s milestone is not the destination, but a waypoint on a longer journey toward reshaping how we do science. The Sakana.AI experiments (as previously highlighted) reignites the long-simmering discussion of whether AI will soon be optimizing its own architecture, refining its own reasoning capabilities, and accelerate the rate of discovery in ways we cannot yet predict. The AI Scientist’s or even Carl automates agent success does not mean we are at that inflection point—but it does suggest we may be closer than many people think.

While AI has revolutionized research methodologies, it does come with challenges:

▪ Contextual understanding: AI tools often struggle with contextual understanding, particularly when it comes to interpreting cultural nuances, sarcasm, and complex contextual meanings. For example, in sentiment analysis, an AI might mistakenly label a sarcastic comment as positive due to its literal wording. Similarly, culturally specific idioms or humor can be misinterpreted—what is a light-hearted joke in one culture might be seen as serious or even offensive in another. These challenges underscore the importance of integrating human insight with AI-driven analysis to ensure that subtle nuances are accurately captured and interpreted.

▪ Ethical and privacy concerns: The integration of AI into QR raises critical ethical and privacy issues, particularly around data security, informed consent, and the management of sensitive information. For instance, if AI tools analyze interview transcripts without adequate anonymization, there is a risk of exposing personal details of participants. Similarly, when using AI to sift through social media content, researchers must ensure that individuals’ posts are treated with confidentiality and that data usage complies with informed consent protocols, as scraping data without permission can lead to privacy breaches. Such examples underline the need for stringent data protection measures and clear ethical guidelines to safeguard participants’ rights throughout the research process [57].

▪ Bias in AI algorithms: If the training data is biased, the outcomes of the AI analysis could also be biased, leading to skewed analysis. Note that AI models, trained on large datasets, can inadvertently carry biases that may distort QR [58]. For instance, when AI tools are used to perform sentiment analysis on open-ended survey responses, they might misinterpret culturally specific language or idioms, often underrepresenting the views of minority groups. Similarly, automated coding systems in qualitative studies can reinforce gender or racial stereotypes if the training data predominantly reflects dominant narratives. Another example is the bias observed in topic-modeling, where the algorithm might favour prevalent topics at the expense of less represented yet significant ones, thereby skewing the overall interpretation of qualitative data.

▪ Interpretability: Some AI models, especially deep learning, act as “black boxes”, making it difficult to interpret how decisions are made. For example, when a deep neural network classifies text or images, it performs complex, layered computations that obscure the specific features or data patterns that led to its decision. This opacity can pose significant challenges, such as difficulty in diagnosing errors or biases in the system. In practical applications, such as in healthcare diagnostics or legal decision support, stakeholders require clear explanations for why a particular decision was made. As a result, there has been growing interest in the development of explainable AI (XAI) [59] techniques, which is a set of methods and processes designed to enable human users to comprehend and trust the outcomes produced by machine learning algorithms. XAI aims to provide transparency and insights into the inner workings of these models, allowing users to understand the reasoning behind specific decisions or predictions. However, these techniques are still evolving and often involve a trade-off between model performance and interpretability, meaning that increasing transparency can sometimes come at the cost of reduced predictive accuracy.

▪ Dependence on quality data: The accuracy of AI’s insights relies heavily on the quality of input data that can be a limitation in fields with limited or noisy data. For instance, inadequate data may lead to skewed or inaccurate results.

A recent Nature article by Gibney [60] reveals a critical challenge in AI development. Training models on AI-generated data can lead to “model collapse”, where outputs degrade into nonsense over successive iterations. As human-generated data dwindles online, large language models risk consuming their own “AI echo chambers,” which amplifies errors and reduces reliability. This highlights the urgent need to rethink training approaches for sustainable AI advancement. Fig. 9 illustrates the model collapse. Another recent study by Hosseini & Donohue [61], published in Nature Machine Intelligence, underscores the critical need for caution and clear guidelines when utilizing AI in genomics research. While AI holds immense promise for revolutionizing genetic data analysis and driving breakthroughs in personalized medicine, it also presents significant challenges. For instance, AI-powered genetic predictions could advance early disease detection, yet, without robust oversight, they risk enabling discriminatory practices in areas such as insurance and employment. Moreover, an article by Matthew Sparkes in NewScientist discusses the complexity of large AI models like OpenAI’s ChatGPT, which rely on billions of numerical weights, functioning as neurons within neural networks. These weights are meticulously fine-tuned during training to enable the models to perform various tasks. Altering just one weight can destabilize the entire system, leading to errors. This highlights the fragility of current AI systems and the challenges in ensuring their reliability, security, and maintainability. Building more resilient AI will require significant innovations in design.

Figure 9: The increasingly distorted images produced by an AI model that is trained on data generated by a previous version of the model. Credit: Boháček & Farid. From [61]

6.1 The Generative AI Paradox and How It Impacts Education

A study [62] led by researchers at Wharton and Penn reveals that while generative AI boosts student performance during practice sessions, it might also hinder the development of essential skills. The experiment, involving nearly 1000 Turkish high school math students, showed that those using GPT Base outperformed the control group by 48% in practice but scored 17% lower on exams, indicating an over-reliance on the tool. In contrast, students who used a teacher-guided GPT Tutor, which offers hints rather than direct answers, improved practice performance by 127% without any decline in exam scores. These findings underscore the importance of implementing AI with safeguards to support deep, foundational learning. While the study’s strong randomized controlled trial design and large sample are commendable, confounding factors—such as math proficiency, motivation, teacher effectiveness, and socioeconomic status—may affect its validity. Future research should address these issues through stratified randomization, detailed data collection, regression modeling, standardized teacher training, and follow-up assessments. As reported in [63] (which is a critic to [62]).

In the end, what can be said is that the study [62] reveals a paradox: while generative AI simplifies tasks, overreliance on it can impair skill development and deep understanding. Researchers warn that without proper oversight and training, both students’ overconfidence and teachers’ concerns about AI misuse may lead to learning gaps and misinformation.

6.2 The Rise of AI in Peer Review: Enhancing Evaluation while Sparking Debate

Is AI set to dominate peer review? Alternatively, let say AI is increasingly involved in reviewing papers—provoking interest and unease.

In fact, AI is transforming peer review and many scientists are worried. AI is increasingly being used in the peer-review process, offering potential benefits such as enhanced efficiency and accuracy. However, this integration has raised concerns among scientists regarding confidentiality, ethical implications, and the potential for AI to replace human judgment. While AI can assist in tasks like checking statistics and summarizing findings, its role in generating comprehensive reviews is controversial. Many publishers currently prohibit the use of AI in peer review due to fears of leaking confidential information and compromising the integrity of the evaluation process [64]. As AI technology continues to evolve, the scientific community is grappling with establishing guidelines to ensure responsible and transparent use in scholarly assessments. Fig. 10 presents a survey asked 300 researchers to compare human and LLM (using GPT-4) reviews of their own papers. Respondents found LLM feedback slightly less helpful, on average, than human feedback, though LLMs outperformed some human reviewers.

Figure 10: Comparing AI and human peer review from [64]. Percentages may not add up to 100% due to rounding

In contrast, researchers at Stanford University are developing a “feedback agent” to help improve human peer review by identifying vague feedback. AI tools like Eliza and Review Assistant aim to enhance peer review by suggesting improvements, recommending references, and verifying claims. Additionally, Grounded AI’s Veracity tool checks the accuracy of citations, streamlining the peer review process.

In addition, we refer to [51], which discusses how ChatGPT is transforming the peer review process. It has been reported that, at major computer science publication venues, up to 17% of peer reviews are now written by AI.

AI tools like Paper-Wizard offer automated peer reviews, analyzing aspects such as statistical rigor, but opinions on AI-led reviews are divided. Some believe AI could improve review speed and accuracy, while others warn that AI lacks the critical judgment needed for true peer review. There is a growing concern over AI potentially replacing human reviewers, leading to calls for transparency and clear guidelines.

6.3 Beyond Human? Assessing AI as Participant in QR

Many studies explore the role of AI as a participant in QR, evaluating its ability to generate humanlike responses. For instance, the study [65] examines the challenges posed by generative AI, such as ChatGPT, in online studies reliant on human participants. The authors contribute to debates on ‘AI as participant’ and the risks of AI-generated imposter responses. Drawing from their story completion study on mobile dating during the COVID-19 pandemic, they describe how they identified AI-generated responses by analyzing affective and discursive qualities of participant data. Their findings reveal that AI-generated responses lack the depth of human affect and experiential richness, concluding that AI cannot fully replicate the lived experiences essential to QR. The study also distinguishes AI as a research participant from AI tools that supplement human analysis.

Some research, such as that by Hämäläinen et al. [66], suggests that AI-generated responses can be ind-istinguishable from human ones, indicating AI’s potential in ideation and pilot studies, though not as a full replacement for human data. From a positivist perspective, studies in psychology and computer science demonstrate that ChatGPT can replicate human moral judgments and problem-solving abilities. However, concerns persist regarding AI’s reproduction of societal biases and the implications for research integrity when qualitative studies depend on human subjectivity. The authors highlight these risks through their own encounter with AI-generated data, emphasizing the need for researchers to anticipate and address such challenges.

6.4 Beyond Imitation: Toward Original Thinking

Is compositional regularization truly original research? In a narrow sense—yes. A study in [47] introduced a novel experimental setup, explored a fresh perspective on generalization, and was deemed worthy of presentation. However, its findings were incremental, ultimately demonstrating that its hypothesis failed.

From a broader philosophical perspective, originality in science extends beyond novelty; it involves intuition, the ability to ask meaningful questions, and seeing beyond the data. This distinction is akin to the difference between solving a math problem and inventing an entirely new branch of mathematics. The latter requires a system capable of understanding the world, making predictions based on experience, and planning actions based on abstract goals—abilities that remain out of AI’s reach. Nonetheless, the fact that AI can convincingly imitate scientific reasoning is significant. It raises the bar for what is possible. In the coming years, AI may generate hypotheses, automate laboratory work, and even co-author groundbreaking research. However, authorship does not imply understanding, and prediction is not equivalent to comprehension, as reported by Craig S. Smith in Forbes, titled “When AI takes over scientific discovery”.

This discussion underscores AI’s fundamental limitations in achieving true originality. While AI can mimic human-like reasoning, it lacks the deep intuition, creativity, and conceptual understanding that define genuine scientific innovation.

7 Future Prospects & Research Methodoly Adaptations

The integration of AI in research is set to revolutionize the landscape of scientific inquiry, paving the way for more advanced and autonomous research systems. These systems are expected to go beyond routine tasks, enabling researchers to focus on creative and strategic aspects of science. Key advancements may include:

▪ Formulating and refining research questions: AI systems could leverage large datasets and domain-specific knowledge to identify unexplored areas, generate hypotheses, and propose innovative research directions

▪ Designing experiments and analyzing results autonomously: Advanced AI algorithms can simulate experimental scenarios, optimize research protocols, and process complex data efficiently, reducing the time from hypothesis to conclusion.

▪ Collaborating with human researchers: AI systems may function as co-researchers, assisting in drafting manuscripts, identifying errors in analyses, or providing alternative interpretations of results. This human-AI collaboration could improve research output quality and speed.

To fully realize the potential of AI in research, methodologies must evolve to integrate AI seamlessly into existing paradigms. Some essential adaptations include:

▪ Training in AI techniques: Modern researchers must develop foundational knowledge of AI tools and their applications. This includes understanding ML models, NLP, and data visualization tools to interact effectively with AI systems.

▪ Collaborative approach: Multidisciplinary teams will become the norm, combining domain experts with data scientists and AI specialists. Such collaboration ensures both technical rigor and domain relevance in research projects.

▪ Adapting ethical frameworks: With the increased reliance on AI, researchers must revisit and update ethical guidelines to address challenges like algorithmic bias, data privacy, and accountability in decision-making. These frameworks should ensure transparency and fairness in AI-assisted research practices.

▪ Developing standards for AI-generated content: Establishing protocols to distinguish human input from AI-generated results will help maintain the integrity of scientific communication.

Looking ahead, researchers who embrace these adaptations and harness AI’s potential stand to drive groundbreaking discoveries while responsibly addressing the ethical and technical complexities of this transformative era.

In an article by Schaul [67], it is argued that philosophy plays a pivotal role in shaping the future of AI. At its core, philosophy provides the tools to think critically, challenge assumptions, and explore the nature of knowledge—skills that are as essential for machines as they are for humans. Centuries ago, Socrates revolutionized learning with his method of teaching through questions rather than answers. The Socratic method encouraged critical thinking, questioned deeply held beliefs, and uncovered profound truths through dialogue, transforming the way knowledge is pursued. Building on this legacy, Tom Schaul introduced the concept of “Socratic learning” for AI. By engaging in language games, AI transcends static datasets, learning dynamically through interaction and self-discovery. This represents more than a technical innovation; it marks a paradigm shift in how intelligence evolves and aligns with human values and aspirations.

7.1 Ethical Use of AI in QR: Key Considerations

AI tools can be ethically integrated into QR, provided their use aligns with responsible research practices. Below are essential considerations:

▪ Institutional/organizational policies: Review guidelines from your university, journal, or ethics board regarding AI use in research. Compliance avoids conflicts and ensures accountability.

▪ Transparency in methodology: Explicitly document how AI tools (e.g., ChatGPT) were applied (e.g., thematic coding, pattern analysis) in your research design. This fosters reproducibility and trust. Disclose the AI tool’s role (e.g., AI-assisted analysis) in publications or appendices.

▪ Data privacy & security: Anonymize sensitive data rigorously before AI tool usage. Avoid uploading identifiable participant information. Review AI providers’ data use policies. For instance:

∘ OpenAI: User data may train models by default; disable this via settings.

∘ Anthropic: Data is not used for training by default.

▪ AI as a supplementary tool: Treat AI as a co-pilot, not a replacement for researcher expertise. Critical thinking must drive interpretation, hypothesis-building, and validation. Example: Use ChatGPT to generate initial coding frameworks, but refine results through human analysis.

▪ Mitigating bias and ensuring rigor: Validate AI outputs via triangulation (e.g., cross-checking with human-coded data using NVivo) or peer review. Establish structured protocols:

∘ Begin with clear research questions to guide AI input.

∘ Audit AI-generated insights for biases (e.g., cultural, linguistic).

▪ Technical competence: Understand the AI tool’s limitations (e.g., ChatGPT’s tendency to “hallucinate” or reproduce societal biases).

Note that participants in a study of [55] emphasized the ethical considerations of using AI in QR, including bias mitigation, data privacy compliance, and transparency, ensuring adherence to regulations like GDPR to maintain trust and credibility.

Ethical AI use in QR hinges on how—not whether—tools are applied, as shown in Fig. 11. By prioritizing transparency, rigor, and human oversight, researchers can responsibly harness AI’s efficiency while upholding ethical standards.

Figure 11: Diagram of ethical considerations in AI-assisted QR

7.2 Recommend AI Tools for Qualitative Methods

Many researchers, including participants in a study in [55] highlight the limited availability of free AI tools for QR, with ChatGPT being the most commonly recommended. Other suggested tools include PSPP, Weka, Claude, QuillBot, PaperPal, Iris.ai, Zotero, Scite, Litmaps, Research Rabbit, Reverso, Jasper Al, Dall-E 2, SEO.ai, Hemingway Editor, Grammarly, JenniAl, Lateral, Turnitin and Perplexity.

Experts also advocate for AI solutions from major companies like OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, and Meta, which enhance QR through data collection, transcription, coding, analysis, visualization, and interpretation. For instance, Azure Cognitive Services provides speech-to-text, sentiment analysis, and text analytics, while Microsoft Power BI enables data visualization and real-time analytics. Google Cloud Natural Language API supports entity recognition, sentiment analysis, and syntax analysis. Google Speech-to-Text and Meta AI facilitate transcription, social media data analysis, and image recognition. IBM Watson offers advanced NLP tools, including sentiment analysis and entity extraction, useful for analyzing customer feedback. NVivo and Atlas.ti are preferred for ethnographic research and thematic analysis, while Dedoose integrates qualitative and quantitative data for mixed-methods research. Furthermore, AI-powered platforms like Qualz.ai and Insight7 have emerged to streamline qualitative data analysis. Qualz.ai offers AI-driven data collection, automated coding, and interactive visualization, enabling researchers to derive deeper insights more efficiently. Insight7 provides automated transcription, thematic analysis, and customizable reports, facilitating the synthesis of insights from interviews and open-ended survey responses.

By leveraging these AI tools, researchers can enhance the efficiency and depth of qualitative research methodologies, overcoming traditional limitations and unlocking new analytical possibilities.

The contribution of QR to theory development and advancement remains significant and highly valued, especially in an era of various epochal shifts and technological innovation in the form of AI. Even so, the academic community has not yet fully explored the dynamics of AI in research and there are significant gaps in our understanding of how AI can be used most effectively in the context of theory building [68]. The integration of AI into QR methodology presents significant opportunities and challenges. AI technologies, such as NLP and ML, have the potential to revolutionize how researchers collect, analyze, and interpret qualitative data, offering enhanced efficiency, scalability, and objectivity. These advancements allow for the rapid processing of large data sets and the identification of subtle patterns that may be overlooked in manual analysis. However, AI should be seen as a complementary tool rather than a replacement for human insight. The inherent richness of QR, centered on context, emotion, and complex human experiences, still requires the nuanced interpretation that only human researchers can provide. Moreover, challenges such as data privacy, ethical concerns, and AI’s limitations in understanding cultural or contextual subtleties must be carefully managed. Moving forward, the most effective approach will be a hybrid model that combines AI’s analytical power with the depth of human expertise. This balanced integration enhances the quality of QR while preserving its essential character. As AI technologies continue to evolve, researchers must adapt their methodologies and ethical frameworks to harness these tools responsibly, ensuring that the core values of qualitative inquiry remain intact. Despite AI’s potential, further research is needed to explore how it can be effectively utilized as a research tool while maintaining the integrity of qualitative inquiry [69].

AI is advancing rapidly in scientific research, with systems like The AI Scientist and Carl now capable of generating scholarly articles. These developments highlight the growing role of AI in authoring scholarly articles, suggesting that AI may be closer to conducting original scientific research than previously anticipated. However, concerns over AI-generated fraudulent papers have prompted journals to implement stricter authorship guidelines. While AI offers promising tools for research, its role in publishing must be carefully managed to uphold academic integrity. As well as its role in peer reviewing. For instance, the Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh, published by Sage, has issued editorial guidelines on the responsible use of AI in scientific writing and peer review [70].

Finally, most AI models today are static—once deployed, they do not evolve in response to new information. This rigidity is a major limitation, setting AI apart from biological intelligence, which continuously learns and adapts. However, this is rapidly changing with researchers developing models that can update their parameters in real time, allowing them to improve and refine their performance as they encounter new data. This emerging approach—often called continual learning, self-adaptive AI, or test-time training—is revolutionizing the AI field. By dissolving the traditional separation between training and inference, it is unlocking unprecedented capabilities and reshaping the competitive landscape for AI-driven businesses. As continual learning advances, it is poised to challenge existing assumptions and expand the boundaries of what AI can achieve.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research did not receive any specific grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

1https://sakana.ai/ai-scientist/ (accessed on 02 April 2024)

2https://iclr.cc/ (accessed on 02 April 2024)

3https://github.com/SakanaAI/AI-Scientist (accessed on 02 April 2024)

4https://www.autoscience.ai/blog/meet-carl-the-first-ai-system-to-produce-academically-peer-reviewed-research (accessed on 02 April 2024)

5https://github.com/SakanaAI/AI-Scientist-ICLR2025-Workshop-Experiment (accessed on 02 April 2024)

References

1. Zdeborová L. New tool in the box. Nat Phys. 2017;13(5):420–1. doi:10.1038/nphys4053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Fösel T, Tighineanu P, Weiss T, Marquardt F. Reinforcement learning with neural networks for quantum feedback. Phys Rev X. 2018;8(3):031084. doi:10.1103/PhysRevX.8.031084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Longo L. Empowering qualitative research methods in education with artificial intelligence. In: Costa A, Reis L, Moreira A, editors. Computer supported qualitative research. WCQR 2019. Advances in intelligent systems and computing. Vol. 1068. Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany: Springer; 2020. p. 1–21. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-31787-4_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Melnikov AA, Poulsen Nautrup H, Krenn M, Dunjko V, Tiersch M, Zeilinger A, et al. Active learning machine learns to create new quantum experiments. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2018;115(6):1221–6. doi:10.1073/pnas.1714936115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Benbya H, Davenport TH, Pachidi S. Artificial intelligence in organizations: current state and future opportunities. MIS Q Exec. 2020;19(4). doi:10.2139/ssrn.3741983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Wu F, Lu C, Zhu M, Chen H, Zhu J, Yu K, et al. Towards a new generation of artificial intelligence in China. Nat Mach Intell. 2020;2(6):312–6. doi:10.1038/s42256-020-0183-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhang C, Lu Y. Study on artificial intelligence: the state of the art and future prospects. J Ind Inf Integr. 2021;23(1):100224. doi:10.1016/j.jii.2021.100224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Stokel-Walker C. ChatGPT listed as author on research papers: many scientists disapprove. Nature. 2023;613(7945):620–1. doi:10.1038/d41586-023-00107-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Haider N. Quantum computing: physics-AI collaboration quashes quantum errors. Nature. 2024;635(8040):822–3. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-03557-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Karimzadeh M, Momen-Roknabadi A, Cavazos TB, Fang Y, Chen NC, Multhaup M, et al. Deep generative AI models analyzing circulating orphan non-coding RNAs enable detection of early-stage lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):10090. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-53851-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mallapaty S. Can Google Scholar survive the AI revolution? Nature. 2024;635(8040):797–8. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-03746-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Porter B, Machery E. AI-generated poetry is indistinguishable from human-written poetry and is rated more favorably. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):26133. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-76900-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Kozlov M. CRISPR builds a big tomato that’s actually sweet. Nature. 2024;635(8039):532–3. doi:10.1038/d41586-024-03722-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]