Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Life Cycle-Based Sustainability Assessment and Circularity Mapping for Packaging Materials: Integrating Artificial Intelligence

1 Department of Printing and Packaging Technology, College of Engineering Guindy, Anna University, Chennai, 600025, India

2 Department of Chemical Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai, 600036, India

3 Department of Metallurgical & Materials Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology Madras, Chennai, 600036, India

* Corresponding Author: Ragava Raja R. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 301-327. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.069693

Received 28 June 2025; Accepted 29 August 2025; Issue published 22 September 2025

Abstract

Packaging materials are indispensable in modern industries but also significantly contribute to environmental degradation, resource consumption, and waste generation. This systematic review critically assesses the integration of artificial intelligence (AI), life cycle sustainability assessment (LCSA) following ISO 14040 standards, and circularity mapping to overcome sustainability barriers in packaging. The study identifies environmental, economic, and social hotspots across the life cycle stages of packaging materials by examining real-world case studies such as Coca-Cola’s adoption of recycled PET bottles and Unilever’s commitment to 100% recyclable plastic. AI technologies highlight transformative tools for optimising resource allocation, enhancing waste management, and supporting predictive maintenance in packaging systems. To maximise their impact, circular economy (CE) strategies, including material substitution, reusable packaging, and recycling, are discussed with AI-driven approaches. Policy frameworks like mandatory life cycle reporting and AI-focused capacity-building initiatives drive systemic change. The packaging industry achieves significant sustainability improvements by combining LCSA, CE principles, and AI while fostering economic benefits and social equity. This paper provides a comprehensive foundation for future research and practical applications to transform the packaging sector into a more sustainable and circular system. This review is the first to integrate LCSA, circular economy mapping, and AI applications in sustainable packaging. It highlights practical strategies and identifies research gaps to guide academia, industry, and policymakers toward scalable and intelligent sustainability solutions. Moreover, the review bridges methodological rigour with practical implementation by aligning digital intelligence with material sustainability frameworks, thus forming a multidisciplinary blueprint for a circular future in packaging.Keywords

The global demand for packaging materials has witnessed unprecedented growth, fueled by industrial expansion, e-commerce proliferation, and the intensification of globalisation [1]. Packaging is pivotal in ensuring product safety, facilitating efficient transportation, and enhancing market appeal. However, the environmental ramifications of the packaging sector have raised alarm bells, highlighting the urgent need for sustainable practices [2]. Packaging materials contribute significantly to resource depletion, greenhouse gas emissions, and the growing challenge of waste generation. Addressing these issues necessitates a holistic and systematic approach encompassing environmental, economic, and social dimensions [3].

Life Cycle-Based Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) has emerged as a robust framework for evaluating the comprehensive impacts of packaging materials throughout their life cycle—from raw material extraction and production to usage and end-of-life management [4]. Governed by ISO 14040 standards, LCSA offers a structured methodology to identify environmental hotspots, economic inefficiencies, and social challenges, enabling stakeholders to make informed decisions [5]. However, traditional LCSA approaches are often constrained by their reliance on static data and limited adaptability to dynamic industrial and environmental conditions [6].

In recent years, the principles of the circular economy (CE) have gained significant traction as a transformative paradigm to mitigate the environmental impacts of packaging [7]. Unlike the linear “take-make-dispose” model, the CE emphasises resource efficiency, waste minimisation, and material recovery through recycling, reuse, and material substitution strategies [8]. Circularity mapping, a tool for assessing material flows and identifying circular opportunities, has become indispensable for advancing CE objectives [9]. Nevertheless, achieving circularity at scale requires innovative solutions to overcome technical, logistical, and economic barriers.

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly recognised as a game-changing technology in the quest for sustainable packaging solutions [10]. AI’s data analytics, pattern recognition, and predictive modelling capabilities can augment traditional LCSA and circularity mapping methodologies [11]. By leveraging AI, the packaging industry can optimise resource allocation, improve waste management processes, and enable predictive maintenance of production systems. Moreover, AI can facilitate real-time monitoring and adaptive decision-making, ensuring that sustainability objectives are met efficiently and effectively [12].

The integration of LCSA, circularity mapping, and AI represents a transformative triad for tackling the multifaceted sustainability challenges faced by the packaging sector. While each domain has been studied in isolation, this review is among the first to synthesise their intersection critically. It provides a unified framework that links lifecycle-based impact assessment with regenerative design strategies and intelligent optimisation tools. Through this integration, the study uncovers how AI technologies can enhance the dynamism, accuracy, and responsiveness of both LCSA and circular economy efforts.

This review highlights the practical advancements and lessons learned from industry leaders by examining real-world case studies—such as Coca-Cola’s adoption of recycled PET bottles, Unilever’s pledge toward 100% recyclable plastics, and IKEA’s use of mushroom-based biodegradable packaging. However, unlike prior works that stop at descriptive summaries, this study interrogates how scalable AI techniques can amplify circularity outcomes, bridge performance gaps, and address systemic inefficiencies within traditional packaging systems.

Furthermore, the novelty of this review lies in its dual-layered approach: (1) offering a cross-domain synthesis of sector-specific innovations, and (2) embedding those insights into a technically structured roadmap that maps AI functions (e.g., machine learning, computer vision, reinforcement learning) to packaging sustainability outcomes (e.g., material flow optimisation, lifecycle modelling, waste stream intelligence). This contributes to the field by framing AI not merely as an operational tool, but as an enabler of systems thinking—capable of closing information loops, modelling complex interactions, and dynamically updating lifecycle metrics in real time.

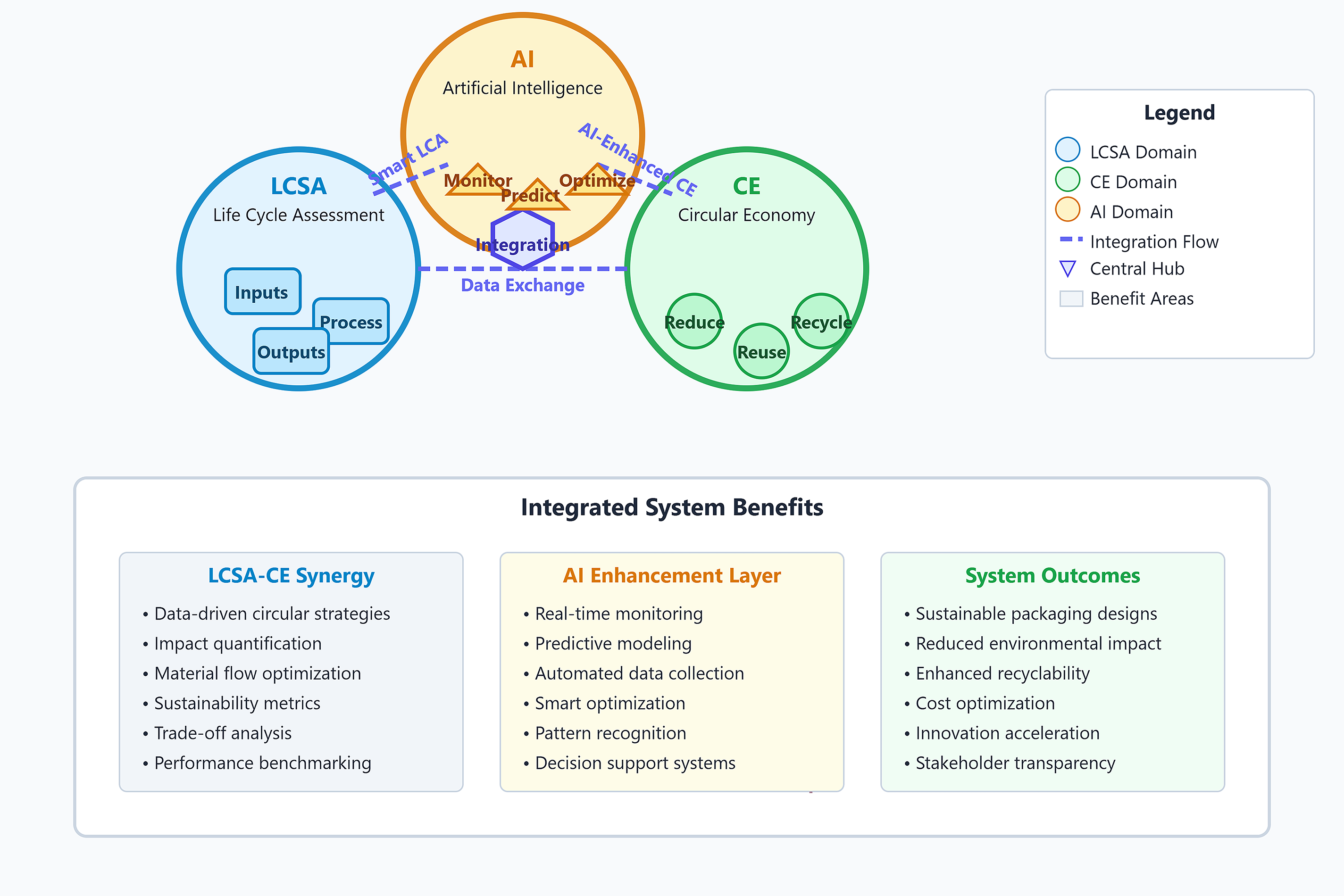

In doing so, this review presents both opportunities and challenges—demonstrating that while AI has enormous potential to augment sustainable packaging systems, it also introduces complexities related to data governance, ethical deployment, and regional equity as illustrated in Fig. 1. Thus, the paper reviews current applications and a strategic foundation for future research and cross-sectoral collaboration to build digitally intelligent, circular packaging ecosystems.

Figure 1: Conceptual integration of LCSA, circular economy, and AI in sustainable packaging

This systematic review followed the PRISMA guidelines to identify and analyse relevant literature published between 2010 and 2025 on sustainable packaging, life cycle assessment, circular economy, and AI applications in the packaging sector [13]. The search was conducted across multiple databases, including Scopus, Web of Science, ScienceDirect, IEEE Xplore, and Google Scholar [14] using combinations of the following keywords: “sustainable packaging,” “life cycle assessment,” “circular economy,” “artificial intelligence,” “packaging waste,” “recycling,” and “biodegradable materials”.

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

• Focused on real-world packaging applications or case studies

• Addressed LCSA frameworks or methodologies for packaging materials

• Described AI-enabled innovations in packaging sustainability

• Proposed or evaluated CE strategies for packaging materials

• Published in peer-reviewed journals or conference proceedings

• Written in English

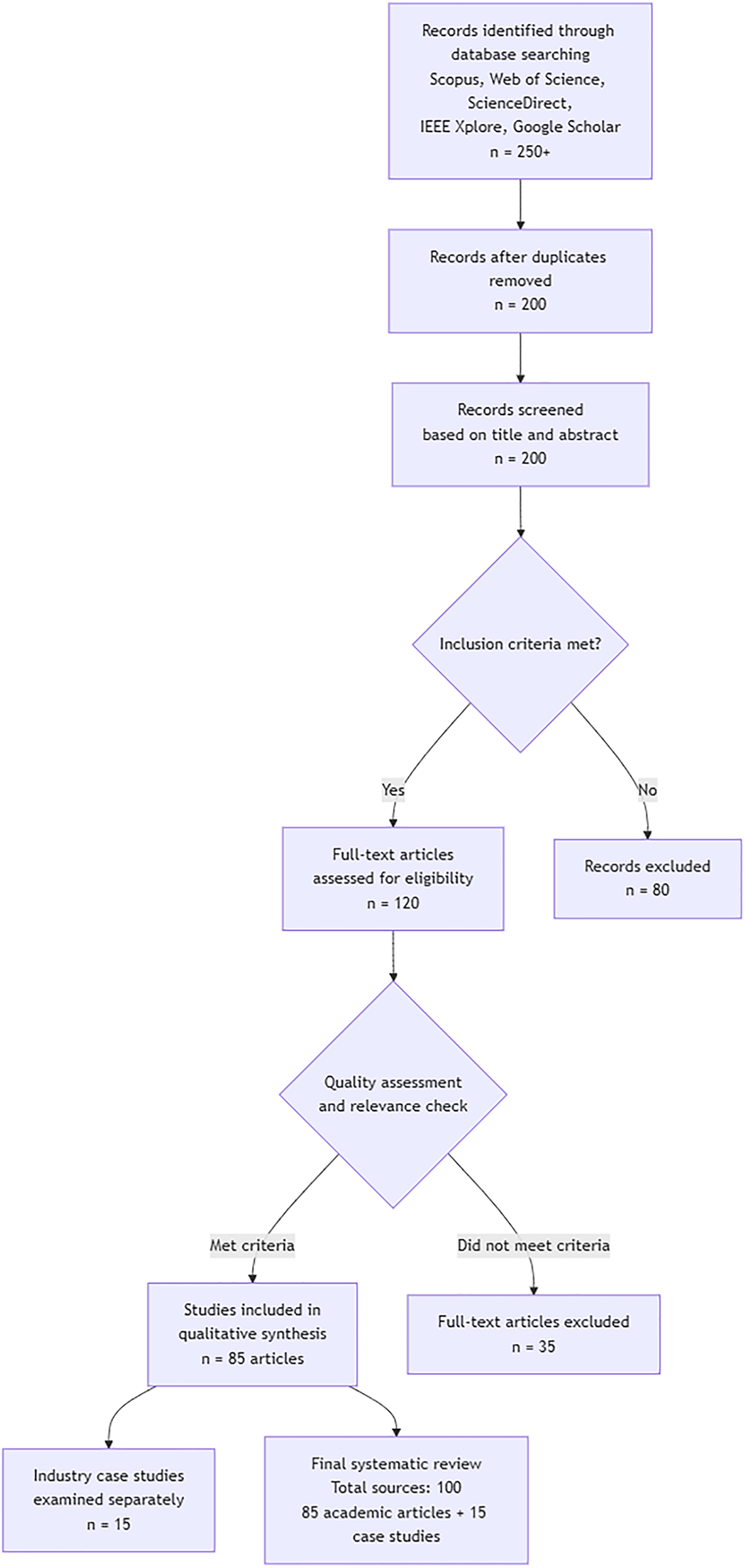

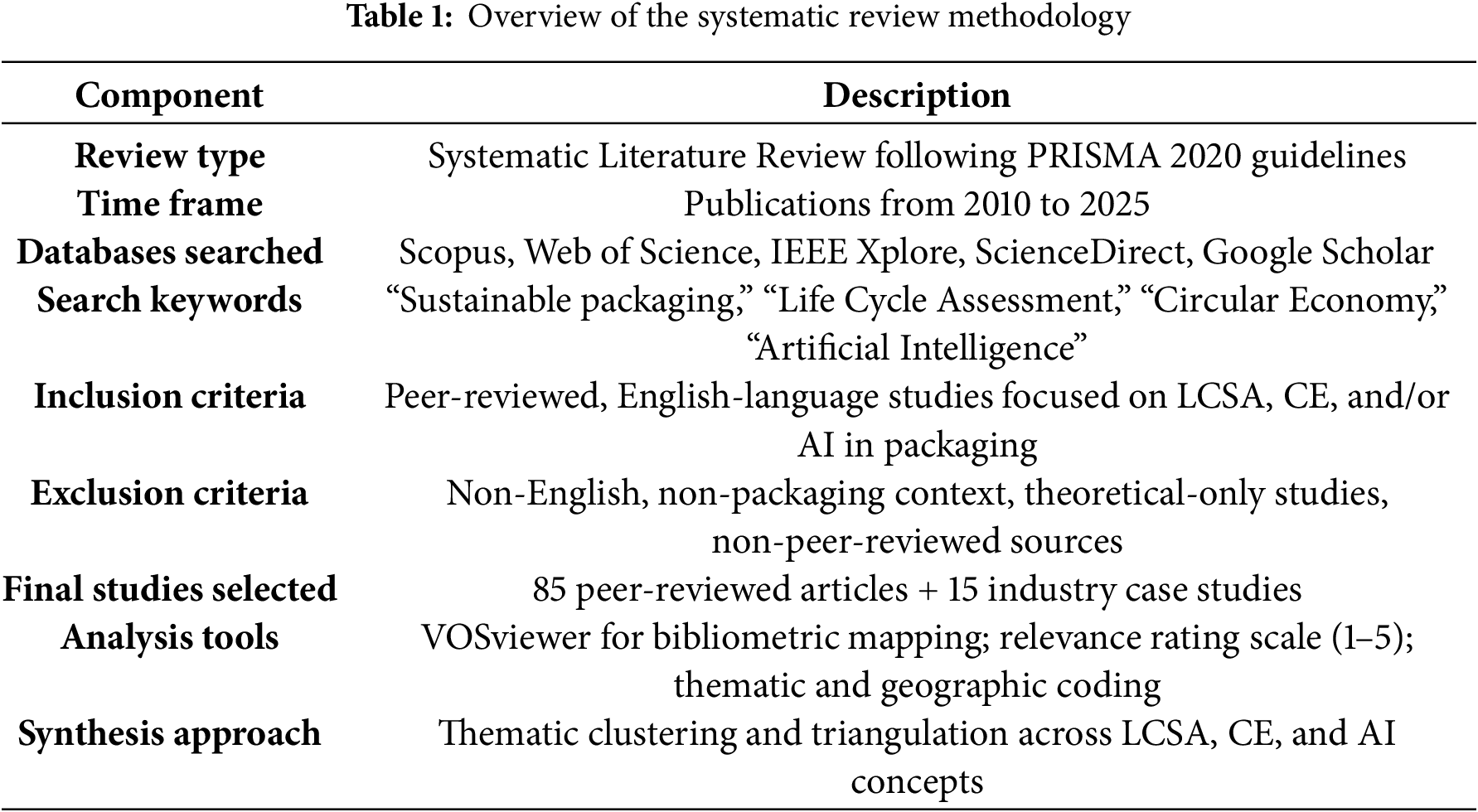

After screening over 250 initial records, as illustrated in Fig. 2, 120 studies were selected for full-text review, and 85 articles were ultimately included in the analysis. Additionally, 15 industry case studies were examined to provide practical insights into implementing sustainable packaging strategies. Data extraction focused on methodological approaches, key findings, technological innovations, and practical implications for the packaging industry. A summary of the review process is provided in Table 1.

Figure 2: PRISMA flow diagram showing the systematic literature review process for identifying and selecting studies on sustainable packaging, life cycle assessment, circular economy, and AI applications in packaging (2010–2025)

Supplementing the initial data extraction, a multi-level coding process facilitated study classification. Key thematic clusters were AI-enhanced LCSA modelling, CE mapping frameworks, and AI-driven recycling/reuse systems. Concurrent geographical categorisation mapped regional variations in adoption patterns. A bibliometric analysis using VOSviewer was conducted to visualise author collaboration networks and keyword co-occurrence, revealing the intellectual structure of the research domain.

A relevance rating (1–5) was assigned to validate selected studies’ relevance based on their methodological transparency, industrial applicability, and thematic depth. Only studies scoring four or above were considered for advanced synthesis. The review also consulted industry white papers, technical guidelines from ISO and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, and public reports from companies like Nestlé, Coca-Cola, and Danone to complement academic insights with practical developments.

A final triangulation step was performed to map intersections across LCSA, CE, and AI. This revealed a critical insight: while CE and LCSA are well integrated in some literature, AI often remains separated from the broader sustainability discourse. This gap underscores the importance of this review. Additionally, the inclusion of cross-sectoral benchmarks allowed the team to detect performance disparities in LCSA adoption between fast-moving consumer goods (FMCG) and industrial packaging sectors. Studies showed that companies employing machine learning for LCA prediction models achieved an average 20% reduction in data processing time. Integrating blockchain for material traceability was also observed in 10% of the case studies, reflecting early convergence between AI and packaging supply chains. A gap analysis further showed that only 5 out of 85 peer-reviewed studies explicitly combined all three concepts—LCSA, CE, and AI—highlighting the critical need for interdisciplinary convergence in this domain.

Positioning with Prior Reviews

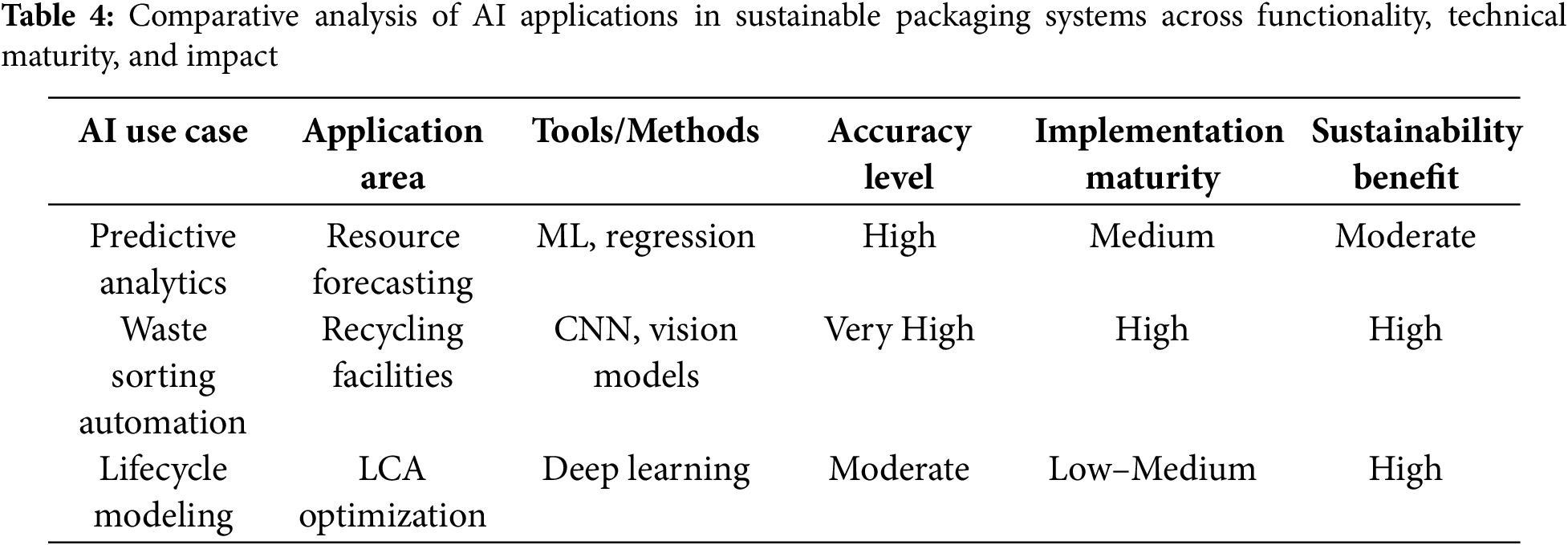

Compared to prior systematic reviews, which primarily addressed AI’s role in circular economy transitions or recycling systems independently, this review is the first to comprehensively integrate Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA), circularity mapping, and artificial intelligence (AI) within the specific context of packaging systems—for example, focused on the role of AI in general CE initiatives without industry-specific granularity [15], while examining AI-based recycling technologies with minimal connection to broader lifecycle frameworks or decision support systems [16,17]. Moreover, existing reviews typically lack cross-domain taxonomies, do not explore model-level AI categorisation, and rarely assess the maturity or scalability of AI tools across packaging functions, as summarised in Table 2.

This paper bridges those gaps by offering a sector-focused synthesis, mapping AI functions to sustainability impacts, and identifying the interoperability barriers across LCSA, CE, and AI frameworks. As such, it presents an application-ready roadmap that enables researchers and industry stakeholders to understand where AI is used and how it can be aligned with lifecycle impact reduction and circular design goals in packaging.

3 Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA)

Life Cycle-Based Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) provides a holistic framework to evaluate packaging materials’ environmental, economic, and social impacts across their entire life cycle [20]. A visual representation of the LCSA framework is shown in Fig. 3. It is guided by ISO 14040 standards, ensuring a standardised approach to sustainability assessment [21]. The LCSA framework incorporates three critical stages:

Figure 3: Visualising the life cycle of sustainable packaging

3.1 Raw Material Extraction and Production

This stage focuses on the initial phases of a packaging material’s life cycle, including the extraction of raw materials and their conversion into packaging products [22]. These processes are often energy-intensive and rely on non-renewable resources, contributing significantly to environmental impacts such as greenhouse gas emissions and habitat destruction [23]. For example, Coca-Cola’s initiative to adopt 100% recycled PET bottles showcases how material innovation can reduce the carbon footprint and reliance on virgin resources [24]. While Coca-Cola and IKEA are frequently cited for sustainable packaging practices, their publicly disclosed AI deployments remain limited primarily to logistics, marketing, and supply chain forecasting—not material-level circularity or packaging-specific AI applications. In this review, these companies are presented as general sustainability leaders, rather than as exemplars of AI-driven packaging systems. Using recycled materials, companies can lower energy consumption by up to 75%, minimise waste, and conserve natural resources.

AI-driven LCA platforms enable dynamic updating of emissions profiles based on operational changes or supply chain disruptions [25]. For instance, machine learning algorithms can analyse raw material sourcing data to identify lower-impact alternatives and optimise processing parameters to reduce energy consumption during production.

The usage phase emphasises the functionality and performance of packaging while minimising its environmental impact [26]. Packaging must balance durability, aesthetic appeal, and environmental performance. Innovations in reusable packaging systems, such as TerraCycle’s Loop program, illustrate how the industry can reduce waste and improve efficiency [27]. This program enables consumers to return used packaging for cleaning and reuse, significantly reducing single-use plastic waste. Lightweighting strategies and intelligent design approaches enhance packaging efficiency and sustainability [28].

AI applications during the use phase include innovative packaging systems that monitor product conditions and optimise shelf life, reducing waste and extending product usability. Computer vision algorithms can assess packaging integrity in real-time, preventing premature disposal of functional packaging [29].

Effective waste management practices are critical for minimising the environmental burden of packaging materials at the end of their life cycle [30]. Recycling, composting, and energy recovery are essential strategies to divert packaging waste from landfills and incineration [31]. Unilever’s investment in advanced recycling technologies demonstrates the potential to enhance material recovery rates and reduce contamination in recycling streams [32]. Moreover, developing biodegradable and compostable materials presents a viable solution to address the challenges of plastic pollution and ensure compatibility with existing waste management infrastructure.

AI technologies have revolutionised end-of-life management through improved waste sorting, recycling process optimisation, and material identification [33]. Systems like AMP Robotics utilise deep learning to identify and sort recyclables with over 99% accuracy, significantly enhancing recovery rates and reducing processing costs [34].

4 Circularity Mapping for Packaging Materials

Circularity mapping aims to establish closed-loop systems for packaging by focusing on strategies such as recycling, reuse, and resource efficiency. A framework illustrating this approach is shown in Fig. 4. It identifies opportunities to minimise waste and optimise resource use across the entire life cycle of packaging materials [35].

Figure 4: Circular economy framework for packaging materials showing material flow optimisation, recycling loops, and waste reduction strategies across the packaging lifecycle

Replacing conventional materials with sustainable alternatives is a fundamental aspect of circularity mapping [36]. For instance, IKEA’s adoption of mushroom-based packaging exemplifies the potential of biodegradable materials to replace traditional plastics [37]. By using renewable and compostable materials, companies can significantly reduce their environmental footprint and align with circular economy objectives [38].

Other promising examples include:

• Dell’s use of bamboo and moulded paper pulp as alternatives to plastic packaging [39]

• Carlsberg’s development of a bio-based “Green Fibre Bottle” [40]

• L’Oréal’s adoption of paper-based cosmetic tubes to replace plastic [41]

AI technologies facilitate material substitution by simulating and predicting the performance of novel materials under various conditions, accelerating the development and adoption of sustainable alternatives.

Effective design strategies are essential for enabling recycling, reuse, and resource efficiency [42]. Packaging that facilitates disassembly and material recovery ensures compatibility with recycling systems. Nestlé’s development of recyclable paper-based packaging serves as a practical example of design for circularity, emphasising the need for innovations that enhance material recovery and reduce waste [43].

Key circular design principles include:

• Mono-material construction to enhance recyclability

• Design for disassembly to facilitate material separation

• Minimalist packaging approaches to reduce resource consumption

• Modular designs that enable component replacement instead of complete disposal

The Material Circularity Indicator (MCI) quantitatively measures circularity in packaging design, helping companies evaluate and improve their packaging systems [44].

A robust waste management infrastructure is crucial for achieving circularity in packaging. Effective waste collection, sorting, and recycling systems maximise material recovery and minimise landfill dependency [45]. TerraCycle’s Loop initiative demonstrates a scalable approach to creating closed-loop systems [46]. By enabling consumers to return used packaging for reuse, the program not only reduces waste but also promotes a culture of circularity [47].

AI enhances waste recovery through:

• Route optimisation for collection vehicles, reducing fuel consumption and emissions [48]

• Real-time waste bin monitoring to optimise collection schedules [49]

• Blockchain-based tracking systems that verify recycled content and ensure transparency [50]

• Predictive maintenance for recycling equipment to minimise downtime and processing inefficiencies [51]

5 Artificial Intelligence Applications in Circular Packaging Systems

AI applications are reshaping sustainable packaging through precision material management, waste stream minimisation, and intelligent recycling enhancement. This technological integration demonstrates significant potential for accelerating circularity in the sector [52]. Fig. 5 illustrates the Artificial Intelligence Integration Network, highlighting key application areas in sustainable packaging.

Figure 5: Artificial intelligence integration network showing key application areas in sustainable packaging: automated waste sorting, predictive analytics, lifecycle optimisation, and intelligent packaging systems

AI-powered systems enable real-time monitoring of packaging processes, improving operational efficiency and minimising environmental impact. Machine learning algorithms are increasingly used to predict material behaviour and optimise packaging design. Furthermore, innovative packaging systems integrated with sensors and IoT facilitate better product tracking, extended shelf life, and informed consumer engagement.

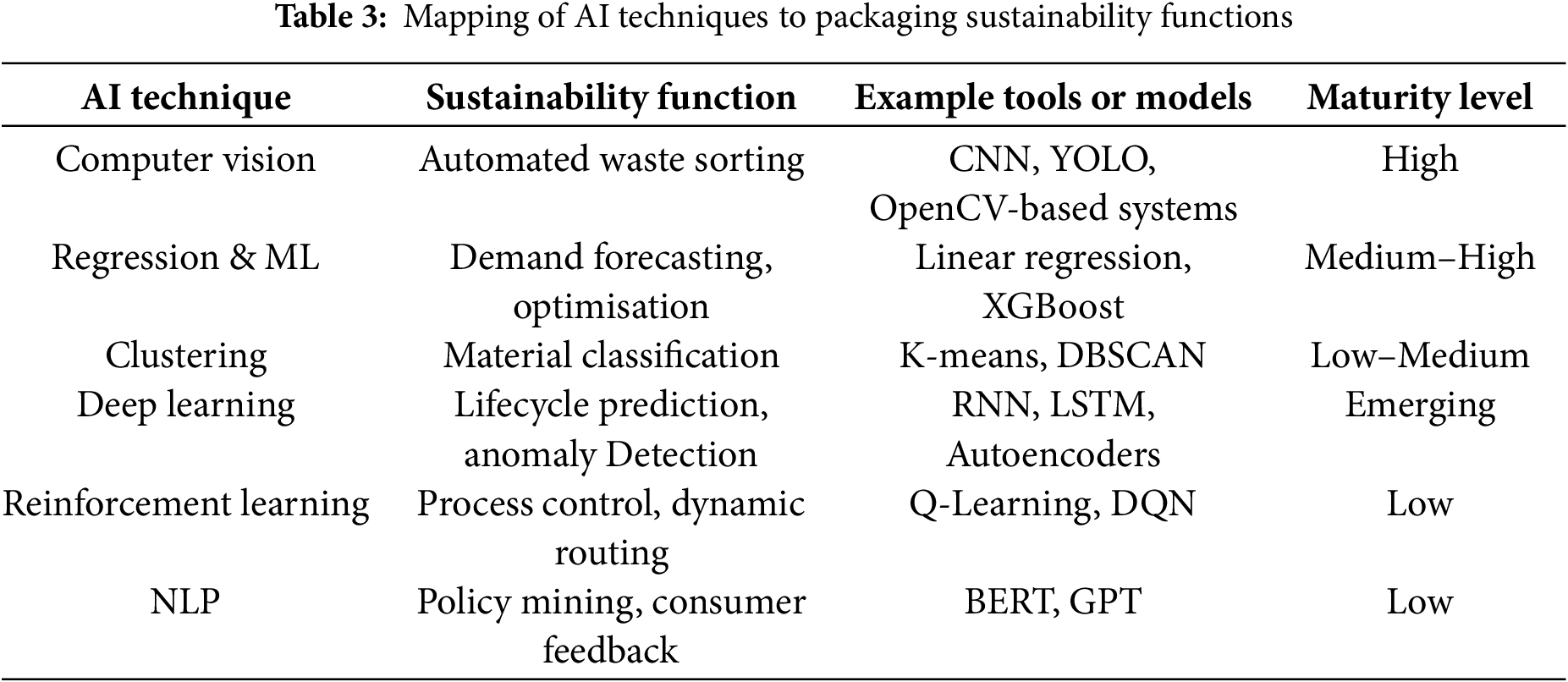

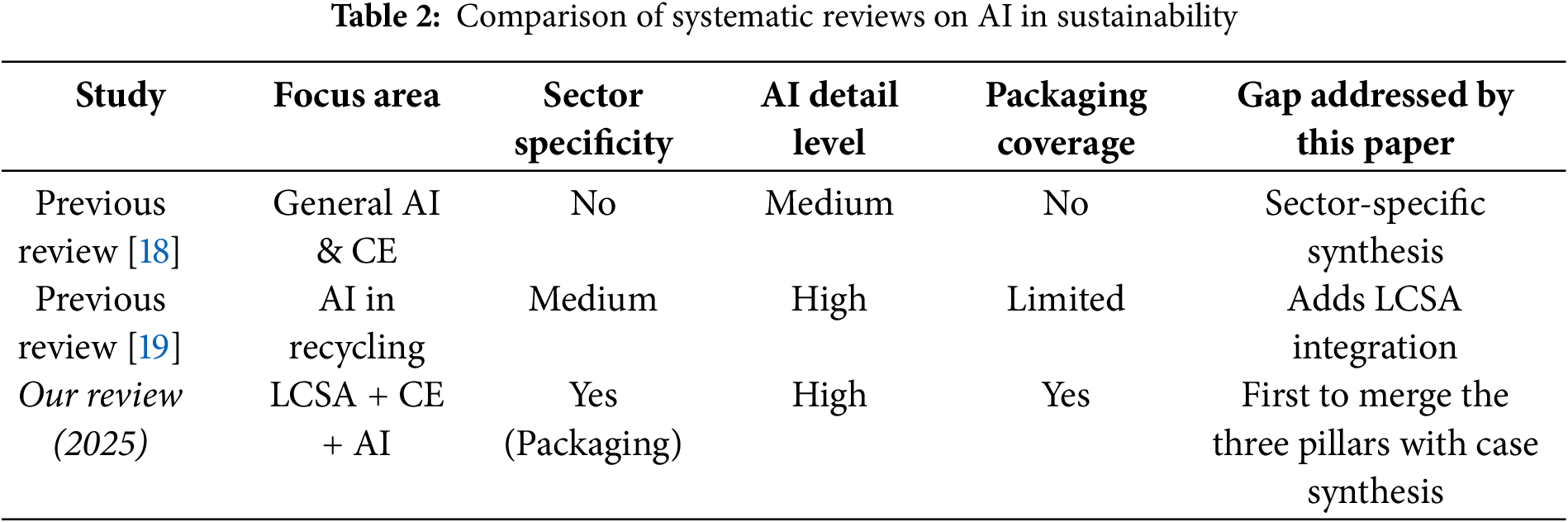

A taxonomy of AI applications in sustainable packaging was developed based on synthesising the reviewed literature. These applications can be categorised into three functional domains aligned with different stages of the packaging lifecycle, as shown in Table 3. First, predictive optimisation involves forecasting material demands, simulating resource flows, and improving packaging configurations through machine learning and statistical models. Second, real-time operational control uses AI in automation tasks such as high-speed waste sorting, defect detection, and sensor-guided process control, often employing computer vision and robotics. Third, by integrating large supply chain and environmental databases, strategic sustainability planning leverages AI to support life cycle sustainability assessments (LCSA), material circularity indicators, and scenario modelling.

Each domain varies in maturity, ranging from early-stage deployment (e.g., LCSA modelling) to industrial-scale implementation (e.g., AI-guided recycling systems). This classification helps clarify how AI contributes across different layers of the packaging value chain and highlights areas that require further technical refinement and real-world validation. A comparative analysis of key AI use cases in sustainable packaging, summarised in Table 4, highlights differences in technical maturity, implementation accuracy, and sustainability benefits across the packaging lifecycle.

While advancements exist, the field lacks established standards for AI deployment in packaging. There is a notable paucity of studies quantitatively measuring essential metrics like AI system precision, scalability, and cost-benefit ratios in practical packaging environments. Furthermore, current AI applications remain narrowly focused on end-of-life waste processing, with fewer innovations in early-stage packaging design or lifecycle forecasting. A cross-comparative framework that integrates technical performance with LCA outcomes is essential to move forward.

5.1 Predictive Analytics for Resource Efficiency

AI-powered predictive analytics has crucial in optimising packaging processes and reducing waste. AI models can accurately forecast material demands by analysing historical data and real-time trends, preventing overproduction and excess packaging. For example, platforms like OptiCycle utilise AI to optimise the recycling process by predicting recycling trends and identifying areas for improvement in packaging supply chains [53]. By leveraging AI’s ability to analyse vast datasets, companies can align production cycles with actual demand, minimising packaging waste and enhancing resource efficiency [54].

Case studies indicate that predictive analytics can reduce packaging material waste by 15%–30% and optimise inventory management, leading to significant cost savings and environmental benefits.

5.2 AI in Automated Waste Sorting

AI has significantly improved waste sorting in recycling facilities, making the process more accurate and efficient [55]. Traditional sorting relies heavily on human labour, which can lead to inefficiencies and contamination of recyclable materials. AI, through machine learning algorithms, is now used in systems like AMP Robotics’ waste sorting robots, which use visual recognition to identify and separate materials such as plastic, metal, and paper with high accuracy [56]. This automation reduces the time and labour required for sorting while improving the quality of recyclable materials, enhancing the efficiency of the recycling process [57].

Recent implementations have demonstrated:

• Increased sorting accuracy from 65%–70% (manual) to 95%–99% (AI-assisted)

• Processing speed improvements of 50%–80%

• Reduced contamination rates in recycling streams by 40%–60%

• Lower operational costs through labour efficiency and improved material recovery [58]

5.3 Lifecycle Optimisation with AI

AI tools help companies optimise the lifecycle of packaging materials by analysing environmental impacts at each stage, from production to disposal [59]. Lifecycle analysis (LCA) tools powered by AI can track energy consumption, raw material usage, and waste generation during packaging production. Google’s AI-driven environmental impact assessments, for instance, provide actionable insights into how packaging can be redesigned to reduce carbon emissions and material waste [60]. AI systems recommend sustainable alternatives, such as using biodegradable materials or reducing packaging weight, ultimately supporting a circular economy where resources are reused and recycled.

Classical LCA models are often deterministic and rely on linear assumptions, static data, and predefined system boundaries. However, real-world packaging systems involve nonlinear relationships, such as feedback loops in supply chains, material degradation over time, and dynamic consumer behaviours. AI, particularly machine learning and neural networks, can more effectively model complex, uncertain, and multidimensional patterns than rule-based simulations. For example, AI can adapt to noisy or incomplete sensor data, learn probabilistic relationships between material properties and lifecycle impact, and update predictions as new data becomes available. This capability is handy for integrating real-time emissions data, evaluating multiple packaging configurations simultaneously, and personalising sustainability assessments based on regional or product-specific variables.

Integration of AI with LCA enables:

• Dynamic updating of environmental impact assessments based on real-time data [61]

• Scenario modelling to evaluate alternative packaging strategies [62]

• Identification of environmental hotspots for targeted improvement [63]

• Automated data collection across complex supply chains [64]

5.4 Smart and Connected Packaging Systems

AI-enabled innovative packaging is a significant advancement in sustainable packaging. By integrating Internet of Things (IoT) sensors, innovative packaging provides real-time data on product usage, packaging condition, and disposal [65]. This data allows for better waste management and more efficient resource allocation. For example, smart tags can monitor packaging integrity during transport and storage, ensuring the product remains in optimal condition [66]. Additionally, these intelligent systems can provide consumers with information on how to dispose of or recycle packaging correctly, encouraging responsible consumer behaviour [67]. The use of innovative packaging extends to areas like reducing food waste by ensuring that perishable items are kept at the right temperature, further enhancing sustainability [68].

Notable applications include:

• Temperature-sensitive indicators that reduce food waste by 15%–25% [69]

• QR codes linking to detailed recycling instructions specific to local infrastructure [70]

• Embedded sensors that monitor product freshness and extend shelf life [71]

• NFC tags enabling product authentication and preventing counterfeit products [72]

5.5 Categorisation of AI Techniques for Sustainable Packaging

Artificial Intelligence encompasses various methodologies suited to different functions within the sustainable packaging lifecycle. While earlier sections have discussed application areas, this section classifies AI techniques based on their underlying learning paradigms—providing a more transparent framework for understanding how different models are aligned with specific sustainability goals in packaging systems.

Supervised learning is the most commonly applied category in sustainable packaging, particularly for predictive modelling tasks such as demand forecasting, lifecycle impact estimation, and material behaviour prediction [73]. These models are trained on historical datasets with labelled outputs, enabling packaging engineers to anticipate environmental or operational outcomes under varying conditions. For instance, linear regression and random forest models forecast material needs and reduce inventory waste. At the same time, support vector machines have been applied to quality control in packaging processes.

Unsupervised learning techniques, by contrast, are employed when labelled data is scarce [74]. These methods—such as clustering and dimensionality reduction—are used to identify hidden patterns in waste streams, segment consumer behaviour in packaging disposal, or detect anomalies in sensor-based monitoring systems. For example, clustering algorithms can help categorise types of recyclable materials from mixed waste datasets without prior labelling, enabling better sorting decisions and targeted recycling interventions.

Deep learning, a subset of machine learning, has seen growing adoption in areas requiring complex pattern recognition—especially image-based applications like automated waste classification using convolutional neural networks (CNNs). These models can accurately identify and sort packaging materials such as PET, HDPE, or mixed plastics, improving both efficiency and purity in recycling systems [75]. Innovative packaging also uses deep learning to enable real-time environmental sensing and dynamic condition monitoring through sensor fusion and signal interpretation.

Reinforcement learning (RL) is an emerging area in circular packaging systems, particularly in adaptive control and sequential decision-making. In RL, agents learn optimal actions through environmental feedback—making it well-suited for route optimisation in waste collection logistics or real-time adjustment of energy inputs during packaging production [76]. For example, RL algorithms can continuously improve the performance of smart bins that signal when they need to be emptied or optimise packaging line operations for minimum material use and energy consumption.

By mapping these AI categories to their specific roles in sustainable packaging, researchers and practitioners can better select and design solutions for each stage of the packaging lifecycle. This classification also reveals opportunities for hybrid models that combine supervised and reinforcement learning or integrate unsupervised pre-processing for enhanced prediction accuracy. Understanding and leveraging these model-level distinctions will be essential for building scalable and interpretable AI solutions as digital infrastructure expands in the packaging sector.

6 Policy Frameworks and Recommendations for Sustainable Packaging

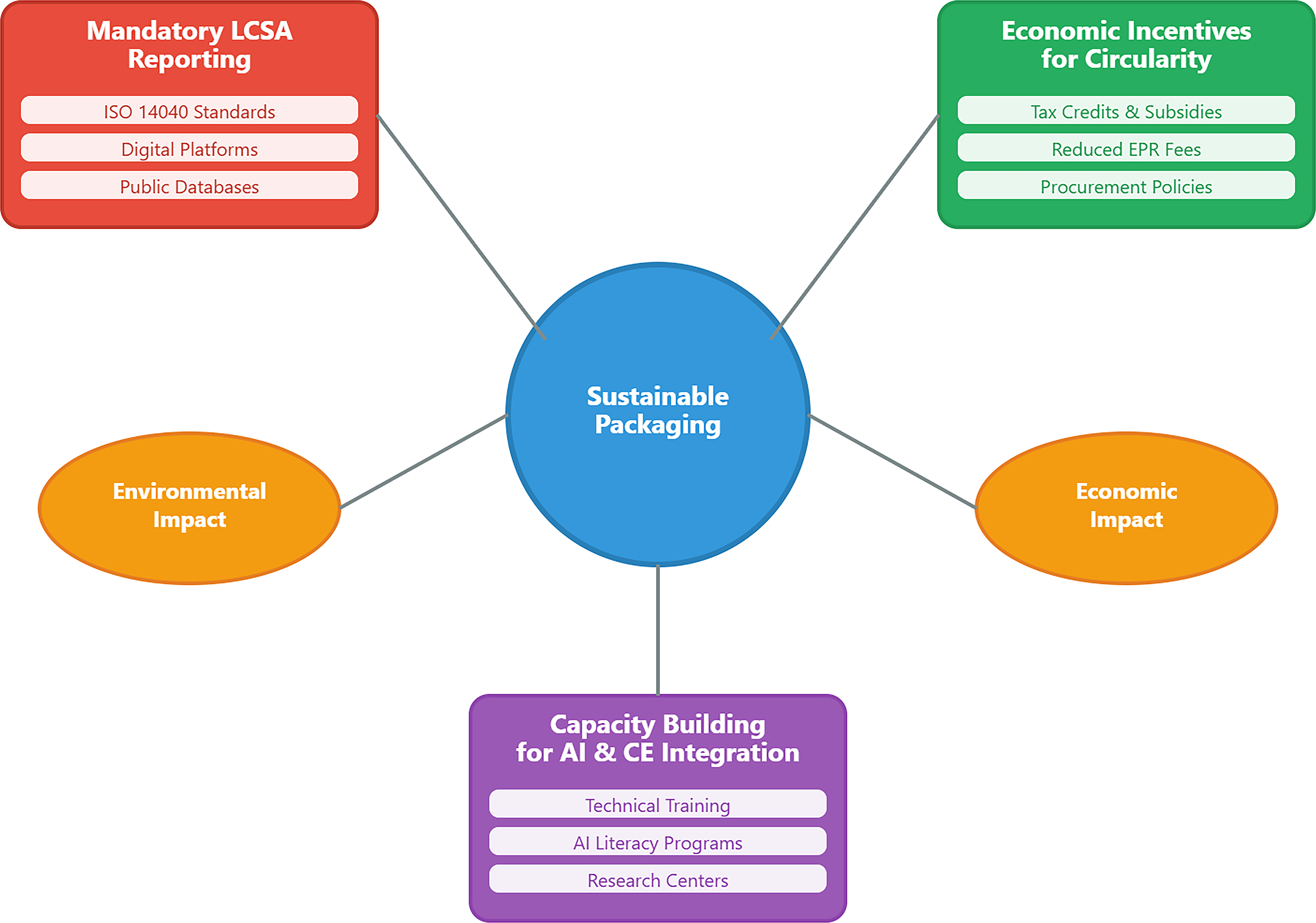

The transition to sustainable packaging systems requires comprehensive policy frameworks that encourage innovation, accountability, and widespread adoption of sustainable practices [77]. Governments play a crucial role in driving this change by creating supportive policies and providing incentives for businesses to shift toward more environmentally-friendly packaging solutions [78]. Fig. 6 illustrates the interconnected nature of these policy frameworks.

Figure 6: Visual representation of sustainable packaging policy frameworks showing the relationship between mandatory Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA) reporting, economic incentives for circular economy adoption, and capacity-building initiatives for AI and circular economy integration

In addition to regulatory mandates, governments must align industrial, environmental, and digital strategies to accelerate circular transformation. Precise definitions of sustainable packaging, standardised compliance metrics, and enforcement mechanisms are essential to ensure industry-wide consistency. Moreover, policy frameworks should be dynamic and adaptive, incorporating feedback from emerging technologies such as AI and real-time environmental monitoring systems.

Implementing Life Cycle Sustainability Assessments (LCSA) for all packaging materials is crucial in ensuring sustainable packaging. LCSA, aligned with ISO 14040 standards, evaluates the environmental, social, and economic impacts of packaging across its entire life cycle—from raw material extraction to disposal [79]. By enforcing LCSA, governments can create a system of accountability and transparency, where companies are required to assess and report the sustainability of their packaging choices [80]. This will incentivise businesses to adopt more sustainable materials, optimise packaging designs, and reduce waste. Mandating LCSA not only helps track the environmental impact of packaging but also provides businesses with valuable insights into where improvements can be made, thus enabling more sustainable choices at every stage of the packaging lifecycle [81].

Policy recommendations include:

• Establishing standardised LCSA reporting frameworks compatible with international standards

• Implementing phased approaches that prioritize high-impact packaging sectors [82]

• Developing digital platforms for streamlined reporting and transparency [83]

• Creating public databases of LCSA results to enable benchmarking and comparative analysis [84]

6.2 Economic Incentives for Circularity

To drive the adoption of circular economy principles in packaging, governments can offer tax benefits, subsidies, and grants for companies that embrace circular designs and sustainable materials [85]. Circular economy practices focus on designing products and materials for reuse, recycling, and remanufacturing, ensuring that packaging materials are used for as long as possible [86]. The European Union’s Circular Economy Action Plan is a strong model for such initiatives, including measures to reduce packaging waste, promote recycling, and encourage using renewable or recycled materials in packaging production [87]. By incentivising circular practices, governments can help businesses offset the initial costs of transitioning to sustainable materials and processes [88]. These incentives will also make sustainable packaging options more competitive, encouraging widespread adoption.

Effective economic mechanisms include:

• Tax credits for investments in circular packaging technologies [89]

• Reduced extended producer responsibility fees for easily recyclable packaging [90]

• Preferential procurement policies for products with sustainable packaging [91]

• Subsidies for research and development of innovative circular packaging solutions [92]

• Landfill taxes and disposal fees that reflect actual environmental costs [93]

6.3 Capacity-Building for AI and CE Integration

Building capacity within organisations and communities is essential to ensure the effective implementation of sustainable packaging practices [94]. Governments should invest in training programs focused on circular economy principles, life cycle assessments, and the integration of advanced technologies such as AI for optimising packaging systems [95]. By offering education and certification programs, businesses, packaging professionals, and policymakers can gain the knowledge and skills needed to support sustainability efforts [96]. Partnerships with organisations such as the Ellen MacArthur Foundation, which focuses on accelerating the transition to a circular economy, can help facilitate knowledge-sharing and create networks of expertise [97]. Additionally, these initiatives should involve collaboration between industry stakeholders, academia, and government agencies to ensure that the latest research and technology are incorporated into policy development and business practices [98].

Priority capacity-building initiatives should include:

• Technical training programs for packaging designers and engineers

• AI literacy programs for packaging industry professionals [99]

• Knowledge-sharing platforms connecting researchers, industry experts, and policymakers

• Interdisciplinary research centres focused on sustainable packaging innovation [100]

• Public awareness campaigns to promote consumer understanding of sustainable packaging [101]

The convergence of LCSA, circularity mapping, and AI presents a powerful opportunity for redefining sustainability in packaging. As industries evolve toward digitised sustainability, combining life cycle thinking with intelligent technologies can transform reactive compliance strategies into proactive optimisation. This section reflects on emerging trends, integration gaps, and future priorities based on the literature examined.

Packaging systems enhanced by AI show potential in automating LCA data collection, reducing errors, and improving granularity in emissions tracking—circularity mapping benefits from real-time material tracking and improved scenario modelling [102]. However, there is a visible fragmentation in the research focus—most studies address only one or two dimensions, and the complete triad is rarely addressed.

The lack of standardised interfaces between LCA tools and AI software limits smooth integration [103]. There is also hesitancy in adopting AI in packaging workflows due to technical skill shortages, data security concerns, and uncertainty in return on investment.

At the same time, the transition to AI-enabled circular packaging is not without risks [104]. Excessive dependence on automation can overlook social and ethical implications. Over-optimising for recyclability may undermine broader product performance. Similarly, designing exclusively for circularity without considering material safety and regulatory compliance can backfire.

To build momentum, industry and academia must collaborate to create open-source AI models tailored to packaging applications [105]. Regional capacity-building must be prioritised, especially in the Global South, to avoid exacerbating digital divides in sustainability transitions [106].

Finally, transparency and accountability will be essential as packaging becomes smarter and more traceable. Stakeholders will need algorithms and assurance that these systems align with social equity, ecological justice, and ethical innovation. Thus, the integration of LCSA, CE, and AI must be guided by interdisciplinary dialogue and long-term systems thinking. This perspective bridges technology foresight and sustainable policy planning, urging a shift from fragmented experimentation to systemic transformation. Success will depend on innovation, transparency, inclusivity, and shared governance across the value chain. As the field advances, integrating behavioural insights, regulatory alignment, and equity-centred design will be as critical as technological sophistication.

8 Future Research Directions in Sustainable Packaging

The future of sustainable packaging is dependent on continued innovation and research [107]. As the demand for eco-friendly solutions grows, addressing key challenges in material use, waste management, and packaging lifecycle is critical [108]. The following research directions are essential for advancing sustainable packaging systems and ensuring their widespread adoption across industries [109].

8.1 Scalable AI Models for Material Flow Optimisation

AI holds immense potential in transforming material and waste management processes, but further research is needed to develop scalable AI models that can be applied across diverse packaging systems [110]. While AI-driven technologies have demonstrated success in optimising packaging designs, waste sorting, and material recovery, there is still a need for more sophisticated models that can handle larger datasets and more complex systems [111]. Researchers should focus on enhancing machine learning algorithms to predict material flows more accurately, optimise recycling processes, and reduce waste generation in real-time [112]. Additionally, AI models must be adaptable to a variety of industries, ensuring that solutions can be customised for different packaging materials and production scales [113]. The development of these scalable AI models will support the circular economy by improving waste management efficiency, extending material lifecycles, and promoting sustainable production practices [114].

Priority research areas include:

• Open datasets and collaborative AI platforms focused on packaging sustainability [115]

• Edge computing solutions for real-time packaging optimisation [116]

• Transfer learning approaches to adapt AI models across different packaging contexts [117]

• Digital twins of packaging systems for simulation and optimisation [118]

8.2 Innovation in Biodegradable Materials

One of the most significant areas for future research is the development of innovative biodegradable materials that can replace traditional plastics and packaging materials [119]. These materials must offer enhanced lifecycle performance, ensuring that they not only decompose efficiently but also provide adequate protection and durability during their use [120]. Research efforts should focus on creating biodegradable materials derived from renewable resources, such as plant-based polymers, that meet the performance standards of conventional packaging [121]. Additionally, these materials should be cost-effective, scalable, and compatible with existing manufacturing processes [122]. Improving the environmental impact of biodegradable materials requires comprehensive studies on their end-of-life behaviour, including biodegradation rates and potential ecological effects [123]. Such research will drive the widespread adoption of biodegradable materials, reducing reliance on single-use plastics and fostering a more sustainable packaging industry [124].

Promising research directions include:

• Novel biopolymers derived from agricultural and food waste [125]

• Composite materials combining natural fibres with biodegradable binders [126]

• Enzymatically triggered degradation for controlled end-of-life management [127]

• Nanocellulose-based packaging with enhanced barrier properties [128]

8.3 Socio-Economic Analysis of Circular Transitions

While the environmental benefits of circular packaging systems are well-documented, there is a need for more research on the socio-economic impacts of such systems, particularly on global supply chains [129]. The transition to circular packaging practices will have far-reaching effects on economies, labour markets, and industries worldwide [130]. Research should focus on understanding how circular packaging systems influence job creation, economic growth, and the redistribution of resources in different regions [131]. Additionally, studies should explore the potential barriers to implementing circular packaging, such as cost, infrastructure challenges, and consumer behaviour [132]. By assessing these socio-economic factors, policymakers and businesses can make informed decisions about the most effective strategies for scaling circular packaging solutions in global supply chains [133].

Key research questions include:

• Job creation and labour market impacts of transitioning to circular packaging systems

• Economic implications for developing economies dependent on packaging production

• Consumer acceptance and willingness to pay for sustainable packaging options

• Supply chain resilience in circular vs. linear packaging systems

• Equity considerations in the distribution of benefits from circular packaging transitions

8.4 Expanding ISO 14040-Based Methodologies

ISO 14040 provides a standardised methodology for life cycle assessments (LCA), but future research should focus on expanding its applicability to a broader range of packaging innovations [134]. While LCA is an essential tool for assessing the environmental impact of packaging materials and systems, there are emerging technologies and materials that require new LCA methods to evaluate their sustainability [135]. Researchers should explore how to adapt and expand ISO 14040 frameworks to account for novel materials, advanced production processes, and innovative packaging designs [136]. By doing so, researchers can create more robust and flexible LCA tools that can be applied to diverse packaging solutions, helping businesses make data-driven decisions that align with sustainability goals [137].

Methodological advances should address:

• Streamlined LCA approaches suitable for rapid innovation cycles [138]

• Integration of social impact metrics within LCA frameworks [139]

• Standardised methods for assessing reusable packaging systems [140]

• Accounting for technological obsolescence in long-lived packaging systems [141]

• Harmonised approaches to quantify the impacts of AI and digital technologies [142]

8.5 Ethical and Algorithmic Governance in AI-Driven Packaging

Future research should develop regulatory frameworks to address ethical concerns surrounding AI in packaging. These concerns include algorithmic bias in waste classification, potential misuse of consumer data from innovative packaging, and a lack of transparency in AI-driven decision-making processes [143]. Ethical AI frameworks specific to packaging technologies must be developed to ensure trust and fairness. These frameworks should incorporate principles of equity, fairness, and environmental justice.

• Developing standardised ethical AI protocols for packaging technologies can ensure fairness, accountability, and transparency across the value chain, particularly where AI automates classification or lifecycle predictions.

• Inclusion of equity and fairness indicators in AI-LCA models can help assess whether outputs support socially inclusive and environmentally just outcomes, especially when targeting underserved or vulnerable populations.

• Third-party auditing systems and traceability tools should be embedded into AI infrastructure to allow stakeholders to verify algorithmic decisions and mitigate risks associated with opaque AI systems.

8.6 Human-AI Collaboration and Cross-Disciplinary Interfaces

Sustainable packaging solutions increasingly depend on collaboration between AI developers, packaging engineers, materials scientists, social scientists, and policymakers. As AI tools become embedded in lifecycle optimisation and intelligent packaging systems, the importance of developing accessible and inclusive interfaces grows [144]. Non-technical users, such as designers or sustainability officers, should be able to interpret AI-generated lifecycle results through intuitive dashboards or simulation tools [145].

• Co-creation platforms and participatory design approaches must be strengthened to enable real-time collaboration between industry, academia, and civil society, ensuring that various perspectives shape AI tools [146].

• Cross-disciplinary training programs and simulation environments (e.g., policy sandboxes) can bridge communication gaps and encourage innovation, enabling diverse teams to experiment with AI-packaging applications in low-risk settings [147].

These strategies ensure that AI-enhanced sustainability systems are technologically advanced, inclusive, equitable, and rooted in social and cultural realities.

The transition to sustainable packaging is both a necessity and a strategic opportunity in the face of escalating environmental challenges. This review demonstrates that integrating Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA), circularity mapping, and Artificial Intelligence (AI) offers a robust framework for designing intelligent, resource-efficient packaging systems. LCSA enables a holistic assessment of environmental, economic, and social impacts, while circular economy principles provide regenerative strategies such as reuse and material recovery. AI complements both by enabling real-time monitoring, predictive modelling, and adaptive control—bridging the gap between static assessments and dynamic decision-making.

AI’s role extends beyond automation; it transforms how packaging systems respond to variability and complexity across the value chain. From material selection to end-of-life recovery, AI facilitates data-driven interventions that enhance efficiency, reduce waste, and support long-term sustainability goals. While companies like Coca-Cola, Unilever, and IKEA illustrate the practical feasibility of these approaches, their implementations also reveal gaps in the consistent use of AI specifically for packaging circularity, indicating untapped potential.

This review contributes a novel synthesis by mapping AI functions to packaging sustainability objectives, classifying AI techniques by their lifecycle application, and integrating them with LCSA and CE frameworks. It highlights best practices and innovations and surfaces interoperability-related challenges, ethical governance, and regional disparities.

Ultimately, the path to sustainable packaging cannot rely on technology alone. Real progress requires coordinated action—standardised methodologies, inclusive policy frameworks, and cross-disciplinary collaboration. The roadmap presented in this review serves both as a conceptual guide and a practical toolkit for transforming packaging from a linear, impact-heavy system into a cornerstone of circular and intelligent sustainability.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This research received no specific grants from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualisation, Ragava Raja R; methodology, Ragava Raja R; validation, Ragava Raja R; investigation, Ragava Raja R; writing—original draft preparation, Ragava Raja R; writing—review and editing, Ragava Raja R; visualisation, Ragava Raja R; supervision, Girish Khanna R. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data supporting the findings of this study will be made available by the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Syed Ali SA, Ilankoon IMSK, Zhang L, Tan J. Packaging plastic waste from e-commerce sector: the Indian scenario and a multi-faceted cleaner production solution towards waste minimisation. J Clean Prod. 2024;447(4):141444. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Rai S, Gurung A, Bhakta Sharma H, Prakash Ranjan V, Ravi Sankar Cheela V. Sustainable solid waste management challenges in hill cities of developing countries: insights from eastern Himalayan smart cities of Sikkim. India Waste Manag Bull. 2024;2(2):1–18. doi:10.1016/j.wmb.2024.02.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Marques C, Güneş S, Vilela A, Gomes R. Life-cycle assessment in agri-food systems and the wine industry—a circular economy perspective. Foods. 2025;14(9):1553. doi:10.3390/foods14091553. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Ziegler-Rodriguez K, Garfí M. Life cycle assessment of constructed wetlands: measuring their contribution to sustainable development. In: Emerging developments in constructed wetlands. Amsterdam, The Netherland: Elsevier; 2025. p. 169–93. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-14078-5.00006-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Padilla-Rivera A, Hannouf M, Assefa G, Gates I. Enhancing environmental, social, and governance, performance and reporting through integration of life cycle sustainability assessment framework. Sustain Dev. 2025;33(2):2975–95. doi:10.1002/sd.3265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Grassi D. The impact of industry 4.0 technologies on circular economy adoption: the case of the Finnish packaging industry [master’s thesis]. Lahti, Finland: LUT University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

7. Otasowie O, Aigbavboa CO, Oke AE. The principles of circular economy. In: Circular economy business model for construction organisations. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 13–32. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-88322-4_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Munonye WC. Towards circular economy metrics: a systematic review. Circ Econ Sustain. 2025;434(3):140066. doi:10.1007/s43615-025-00604-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kalemkerian F, Pozzi R, Tanco M, Creazza A, Santos J. Unlocking circular economy potential: evaluating production processes through circular value stream mapping in real case studies. Manag Environ Qual. 2024;35(3):610–33. doi:10.1108/meq-08-2023-0244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Wu S, Zhang M, Mujumdar AS, Chu C. Sweets and smarts: a comprehensive review of AI applications in future candy research and development. Food Rev Int. 2025:1–23. doi:10.1080/87559129.2025.2504606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Tarazona NA, Machatschek R, Balcucho J, Castro-Mayorga JL, Saldarriaga JF, Lendlein A. Opportunities and challenges for integrating the development of sustainable polymer materials within an international circular (bio) economy concept. MRS Energy Sustain. 2022;9(1):28–34. doi:10.1557/s43581-021-00015-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Al-Raeei M. The smart future for sustainable development: artificial intelligence solutions for sustainable urbanization. Sustain Dev. 2025;33(1):508–17. doi:10.1002/sd.3131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Miller T, Durlik I, Kostecka E, Kozlovska P, Staude M, Sokołowska S. The role of lightweight AI models in supporting a sustainable transition to renewable energy: a systematic review. Energies. 2025;18(5):1192. doi:10.3390/en18051192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Rahaman MT, Pranta AD, Ahmed S. Transitioning from industry 4.0 to industry 5.0 for sustainable and additive manufacturing of clothing: framework, case studies, recent advances, and future prospects. Mater Circ Econ. 2025;7(1):20. doi:10.1007/s42824-025-00176-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. AI-Driven Process for Analyzing Business Actors and their Capabilities in CE Ecosystem—theseus [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jul 27]. Available from: https://www.theseus.fi/handle/10024/857941. [Google Scholar]

16. Elahi M, Afolaranmi SO, Martinez Lastra JL, Perez Garcia JA. A comprehensive literature review of the applications of AI techniques through the lifecycle of industrial equipment. Discov Artif Intell. 2023;3(1):43. doi:10.1007/s44163-023-00089-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Qu C, Kim E. Reviewing the roles of AI-integrated technologies in sustainable supply chain management: research propositions and a framework for future directions. Sustainability. 2024;16(14):6186. doi:10.3390/su16146186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Noman AA, Akter UH, Pranto TH, Haque AB. Machine learning and artificial intelligence in circular economy: a bibliometric analysis and systematic literature review. Ann Emerg Technol Comput. 2022;6(2):13–40. doi:10.33166/aetic.2022.02.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhang S. Research on energy-saving packaging design based on artificial intelligence. Energy Rep. 2022;8(7):480–9. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2022.05.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Larsen VG, Tollin N, Sattrup PA, Birkved M, Holmboe T. What are the challenges in assessing circular economy for the built environment? A literature review on integrating LCA, LCC and S-LCA in life cycle sustainability assessment. LCSA J Build Eng. 2022;50(6223):104203. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2022.104203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Schaubroeck T. Sustainability assessment of product systems in dire Straits due to ISO 14040–14044 standards: five key issues and solutions. J Ind Ecol. 2022;26(5):1600–4. doi:10.1111/jiec.13330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen X, Chen F, Yang Q, Gong W, Wang J, Li Y, et al. An environmental food packaging material part I: a case study of life-cycle assessment (LCA) for bamboo fiber environmental tableware. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;194(10):116279. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Leinonen V. A comparative life cycle assessment (LCA) based biodiversity impact assessment of high-density polyethylene: comparison of end-of-life treatment options: incineration and landfill, mechanical recycling, and chemical recycling [master’s thesis]. Lahti, Finland: LUT University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

24. Naqvi S, Srivastava A, Fatima S, Naqvi N, Pandey P, Lata T. Embracing sustainability: unveiling the dynamics of supply chain practices and processes. In: Transformation of supply chain ecosystems. Leeds, UK: Emerald Publishing Limited; 2025. p. 243–65. doi:10.1108/978-1-83549-246-820251015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Huang R, Mao S. Carbon footprint management in global supply chains: a data-driven approach utilizing artificial intelligence algorithms. IEEE Access. 2024;12:89957–67. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2024.3407839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. da Silva SBG, Barros MV, Radicchi JÂZ, Puglieri FN, Piekarski CM. Opportunities and challenges to increase circularity in the product’s use phase. Sustain Futur. 2024;8(2):100297. doi:10.1016/j.sftr.2024.100297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Shee Weng L. Circular economy in action: case studies of transformative supply chain practices. 2024;5:1–72. doi:10.2139/SSRN.5152884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Li H, Wang B. Green packaging materials design and efficient packaging with Internet of Things. Sustain Energy Technol Assess. 2023;58(3):103186. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2023.103186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Li X, Liu D, Pu Y, Zhong Y. Recent advance of intelligent packaging aided by artificial intelligence for monitoring food freshness. Foods. 2023;12(15):2976. doi:10.3390/foods12152976. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Mostaghimi K, Behnamian J. Waste minimization towards waste management and cleaner production strategies: a literature review. Environ Dev Sustain. 2023;25(11):12119–66. doi:10.1007/s10668-022-02599-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Saravanan A, Kumar PS, Nhung TC, Ramesh B, Srinivasan S, Rangasamy G. A review on biological methodologies in municipal solid waste management and landfilling: resource and energy recovery. Chemosphere. 2022;309(Pt 1):136630. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Baragiola G, Mauri M. SDGs and the private sector: unilever and P & G case studies [master’s thesis]. Milan, Italy: Politecnico di Milano; 2022. [Google Scholar]

33. Stasiškienė Ž, Barbir J, Draudvilienė L, Chong ZK, Kuchta K, Voronova V, et al. Challenges and strategies for bio-based and biodegradable plastic waste management in Europe. Sustainability. 2022;14(24):16476. doi:10.3390/su142416476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Sayem FR, Islam MSB, Naznine M, Nashbat M, Hasan-Zia M, Kunju AKA, et al. Enhancing waste sorting and recycling efficiency: robust deep learning-based approach for classification and detection. Neural Comput Appl. 2025;37(6):4567–83. doi:10.1007/s00521-024-10855-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Sitadewi D, Yudoko G, Okdinawati L. Bibliographic mapping of post-consumer plastic waste based on hierarchical circular principles across the system perspective. Heliyon. 2021;7(6):e07154. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2021.e07154. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Mukherjee PK, Das B, Bhardwaj PK, Tampha S, Singh HK, Chanu LD, et al. Socio-economic sustainability with circular economy—an alternative approach. Sci Total Environ. 2023;904(2):166630. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166630. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Chen R. Sustainable supply chain management as a strategic enterprise innovation. Adv Econ Manag Polit Sci. 2024;85(1):24–9. doi:10.54254/2754-1169/85/20240831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Yang M, Chen L, Wang J, Msigwa G, Osman AI, Fawzy S, et al. Circular economy strategies for combating climate change and other environmental issues. Environ Chem Lett. 2023;21(1):55–80. doi:10.1007/s10311-022-01499-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Srivastava V, Singh S, Das D. Enhancing packaging sustainability with natural fiber reinforced biocomposites: an outlook into the future. E3S Web Conf. 2023;436(3):08016. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202343608016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Marrucci L, Daddi T, Iraldo F. Identifying the most sustainable beer packaging through a Life Cycle Assessment. Sci Total Environ. 2024;948(12):174941. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2024.174941. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Muthana B. Lumene’s entry into the Australian market [master’s thesis]. Joensuu, Finland: Karelia University of Applied Sciences; 2024. [Google Scholar]

42. Chaturvedi R, Darokar H, Patil PP, Kumar M, Sangeeta K, Aravinda K, et al. Maximizing towards the sustainability: integrating materials, energy, and resource efficiency in revolutionizing manufacturing industry. E3S Web Conf. 2023;453(4):01036. doi:10.1051/e3sconf/202345301036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Versino F, Ortega F, Monroy Y, Rivero S, López OV, García MA. Sustainable and bio-based food packaging: a review on past and current design innovations. Foods. 2023;12(5):1057. doi:10.3390/foods12051057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Vadoudi K, Deckers P, Demuytere C, Askanian H, Verney V. Comparing a material circularity indicator to life cycle assessment: the case of a three-layer plastic packaging. Sustain Prod Consum. 2022;33:820–30. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2022.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Pluskal J, Šomplák R, Nevrlý V, Smejkalová V, Pavlas M. Strategic decisions leading to sustainable waste management: separation, sorting and recycling possibilities. J Clean Prod. 2021;278(18):123359. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.123359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ukrainka Volyn L. Project management for the implementation of resource-saving technologies [master’s thesis]. Lutsk, Ukraine: Lesya Ukrainka Volyn National University; 2024. [Google Scholar]

47. Ellsworth-Krebs K, Rampen C, Rogers E, Dudley L, Wishart L. Circular economy infrastructure: why we need track and trace for reusable packaging. Sustain Prod Consum. 2022;29(3):249–58. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2021.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Fang B, Yu J, Chen Z, Osman AI, Farghali M, Ihara I, et al. Artificial intelligence for waste management in smart cities: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2023;21(4):1959–89. doi:10.1007/s10311-023-01604-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Lakhouit A. Revolutionizing urban solid waste management with AI and IoT: a review of smart solutions for waste collection, sorting, and recycling. Results Eng. 2025;25(7):104018. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2025.104018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Bułkowska K, Zielińska M, Bułkowski M. Blockchain-based management of recyclable plastic waste. Energies. 2024;17(12):2937. doi:10.3390/en17122937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Patil D. Artificial intelligence-driven predictive maintenance in manufacturing: enhancing operational efficiency, minimizing downtime, and optimizing resource utilization. 2024. doi:10.2139/SSRN.5057406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Singh A. AI-driven innovations for enabling a circular economy: optimizing resource efficiency and sustainability. In: Innovating sustainability through digital circular economy. Hershey, PA, USA: IGI Global; 2025. p. 47–64. doi: 10.4018/979-8-3373-0578-3.ch003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Guyader H, Ottosson M, Frankelius P, Witell L, Karlstad KU. Identifying the resource integration processes of green service. J Serv Manag. 2020;31(4):839–59. doi:10.1108/josm-12-2017-0350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Bashynska I, Prokopenko O. Leveraging artificial intelligence for circular economy: transforming resource management, supply chains, and manufacturing practices. Sci J Bielsko-Biala School Finance Law. 2024;28:85–91. [Google Scholar]

55. Olawade DB, Fapohunda O, Wada OZ, Usman SO, Ige AO, Ajisafe O, et al. Smart waste management: a paradigm shift enabled by artificial intelligence. Waste Manag Bull. 2024;2(2):244–63. doi:10.1016/j.wmb.2024.05.001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Lubongo C, Bin Daej MAA, Alexandridis P. Recent developments in technology for sorting plastic for recycling: the emergence of artificial intelligence and the rise of the robots. Recycling. 2024;9(4):59. doi:10.3390/recycling9040059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Lubongo C, Alexandridis P. Assessment of performance and challenges in use of commercial automated sorting technology for plastic waste. Recycling. 2022;7(2):11. doi:10.3390/recycling7020011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. AI Recycling is the Answer to Faster, More Accurate Materials Sorting [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jun 11]. Available from: https://en.reset.org/ai-recycling-faster-accurate-materials-sorting/. [Google Scholar]

59. Wang L, Liu Z, Liu A, Tao F. Artificial intelligence in product lifecycle management. Int J Adv Manuf Technol. 2021;114(3):771–96. doi:10.1007/s00170-021-06882-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Sikander A. Artificial intelligence and the circular economy: how AI advances waste reduction. Green Environ Technol. 2024;1(2):23–34. [Google Scholar]

61. da Costa TP, da Costa DMB, Murphy F. A systematic review of real-time data monitoring and its potential application to support dynamic life cycle inventories. Environ Impact Assess Rev. 2024;105(4):107416. doi:10.1016/j.eiar.2024.107416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Yi Y, Wu J, Zuliani F, Lavagnolo MC, Manzardo A. Integration of life cycle assessment and system dynamics modeling for environmental scenario analysis: a systematic review. Sci Total Environ. 2023;903(4):166545. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.166545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Ghoroghi A, Rezgui Y, Petri I, Beach T. Advances in application of machine learning to life cycle assessment: a literature review. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2022;27(3):433–56. doi:10.1007/s11367-022-02030-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Popowicz M, Katzer NJ, Kettele M, Schöggl JP, Baumgartner RJ. Digital technologies for life cycle assessment: a review and integrated combination framework. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2025;30(3):405–28. doi:10.1007/s11367-024-02409-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Khan Y, Bin Mohd Su’ud M, Alam MM, Ahmad SF, Ahmad Ayassrah AYAB, Khan N. Application of Internet of Things (IoT) in sustainable supply chain management. Sustainability. 2023;15(1):694. doi:10.3390/su15010694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Kiritsis D, Bufardi A, Xirouchakis P. Research issues on product lifecycle management and information tracking using smart embedded systems. Adv Eng Inform. 2003;17(3–4):189–202. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2004.09.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Nemat B, Razzaghi M, Bolton K, Rousta K. The role of food packaging design in consumer recycling behavior—a literature review. Sustainability. 2019;11(16):4350. doi:10.3390/su11164350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Karanth S, Feng S, Patra D, Pradhan AK. Linking microbial contamination to food spoilage and food waste: the role of smart packaging, spoilage risk assessments, and date labeling. Front Microbiol. 2023;14:1198124. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2023.1198124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Gurunathan K. Time-temperature indicators (TTIs) for monitoring food quality. In: Smart food packaging systems: innovations and technology applications. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2024. p. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

70. Stanković S, Milutinović N, Ivanović M, Milenković M. Integration of smart waste management solutions: a case study of QR code-based recyclable waste monitoring system. In: 2024 47th MIPRO ICT and electronics convention (MIPRO); 2024 May 20–24; Opatija, Croatia. p. 1943–8. doi:10.1109/MIPRO60963.2024.10569338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Ghosh T, Raj GVSB, Dash KK. A comprehensive review on nanotechnology based sensors for monitoring quality and shelf life of food products. Meas Food. 2022;7:100049. doi:10.1016/j.meafoo.2022.100049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Rastogi R, Sharma BP, Gupta N, Gaur V, Gupta M, Kohli V, et al. NFC-enabled packaging to detect tampering and prevent counterfeiting: enabling a complete supply chain using blockchain and CPS. In: Blockchain applications for healthcare informatics. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2022. p. 27–55. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-90615-9.00002-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Salla JVE, de Almeida TA, Silva DAL. Integrating machine learning with life cycle assessment: a comprehensive review and guide for predicting environmental impacts. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2025;35(2):103. doi:10.1007/s11367-025-02437-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Agrawal K, Abid C, Kumar N, Goktas P. Machine vision and deep learning in meat processing. In: Innovative technologies for meat processing. Boca Raton, FL, USA: CRC Press; 2025. p. 170–210. doi:10.1201/9781003531791-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Qi GJ, Luo J. Small data challenges in big data era: a survey of recent progress on unsupervised and semi-supervised methods. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2022;44(4):2168–87. doi:10.1109/TPAMI.2020.3031898. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Rolf B, Jackson I, Müller M, Lang S, Reggelin T, Ivanov D. A review on reinforcement learning algorithms and applications in supply chain management. Int J Prod Res. 2023;61(20):7151–79. doi:10.1080/00207543.2022.2140221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Ashiwaju BI, Orikpete OF, Fawole AA, Alade EY, Odogwu C. A step toward sustainability: a review of biodegradable packaging in the pharmaceutical industry. Matrix Sci Pharma. 2023;7(3):73–84. doi:10.4103/mtsp.mtsp_22_23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Yadav M, Maurya AK, Chaurasia SK. Eco-friendly polymer composites for green packaging: environmental policy, governance and legislation. In: Sustainable packaging strengthened by biomass. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2025. p. 317–46. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-26637-9.00013-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Valdivia S, Backes JG, Traverso M, Sonnemann G, Cucurachi S, Guinée JB, et al. Principles for the application of life cycle sustainability assessment. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2021;26(9):1900–5. doi:10.1007/s11367-021-01958-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Ostojic S, Backes JG, Kowalski M, Traverso M. Beyond compliance: a deep dive into improving sustainability reporting quality with LCSA indicators. Standards. 2024;4(4):196–246. doi:10.3390/standards4040011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

81. Leroy-Parmentier N, Valdivia S, Loubet P, Sonnemann G. Alignment of the life cycle initiative’s principles for the application of life cycle sustainability assessment with the LCSA practice: a case study review. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2023;28(6):704–40. doi:10.1007/s11367-023-02162-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Zeug W, Bezama A, Thrän D. A framework for implementing holistic and integrated life cycle sustainability assessment of regional bioeconomy. Int J Life Cycle Assess. 2021;26(10):1998–2023. doi:10.1007/s11367-021-01983-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Tokede O, Globa A. Life cycle sustainability tracker: a dynamic approach. Eng Constr Archit Manag. 2025;32(5):2971–3006. doi:10.1108/ecam-07-2023-0680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

84. Poderytė I, Banaitienė N, Banaitis A. Life cycle sustainability assessment of buildings: a scientometric analysis. Buildings. 2025;15(3):381. doi:10.3390/buildings15030381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Chenavaz RY, Dimitrov S. From waste to wealth: policies to promote the circular economy. J Clean Prod. 2024;443(14):141086. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.141086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

86. Zhu Z, Liu W, Ye S, Batista L. Packaging design for the circular economy: a systematic review. Sustain Prod Consum. 2022;32(1):817–32. doi:10.1016/j.spc.2022.06.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

87. Matthews C, Moran F, Jaiswal AK. A review on European Union’s strategy for plastics in a circular economy and its impact on food safety. J Clean Prod. 2021;283:125263. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

88. Tan J, Tan FJ, Ramakrishna S. Transitioning to a circular economy: a systematic review of its drivers and barriers. Sustainability. 2022;14(3):1757. doi:10.3390/su14031757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Bening CR, Pruess JT, Blum NU. Towards a circular plastics economy: interacting barriers and contested solutions for flexible packaging recycling. J Clean Prod. 2021;302:126966. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2021.126966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Joltreau E. Extended producer responsibility, packaging waste reduction and eco-design. Environ Resour Econ. 2022;83(3):527–78. doi:10.1007/s10640-022-00696-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Tanksale AN, Das D, Verma P, Tiwari MK. Unpacking the role of primary packaging material in designing green supply chains: an integrated approach. Int J Prod Econ. 2021;236(3):108133. doi:10.1016/j.ijpe.2021.108133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

92. Cantu CL, Tunisini A. A circular innovation strategy in a supply network context: evidence from the packaging industry. J Bus Ind Mark. 2023;38(13):220–38. doi:10.1108/jbim-07-2021-0325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Yaashikaa PR, Kumar PS, Nhung TC, Hemavathy RV, Jawahar MJ, Neshaanthini JP, et al. A review on landfill system for municipal solid wastes: insight into leachate, gas emissions, environmental and economic analysis. Chemosphere. 2022;309(Pt 1):136627. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2022.136627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. Asim Z, Al Shamsi IR, Wahaj M, Raza A, Abul Hasan S, Siddiqui SA, et al. Significance of sustainable packaging: a case-study from a supply chain perspective. Appl Syst Innov. 2022;5(6):117. doi:10.3390/asi5060117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Seyyedi SR, Kowsari E, Gheibi M, Chinnappan A, Ramakrishna S. A comprehensive review integration of digitalization and circular economy in waste management by adopting artificial intelligence approaches: towards a simulation model. J Clean Prod. 2024;460(3):142584. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2024.142584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Abina A, Temeljotov Salaj A, Cestnik B, Karalič A, Ogrinc Mž, Kovačič Lukman R, et al. Challenging 21st-century competencies for STEM students: companies’ vision in Slovenia and Norway in the light of global initiatives for competencies development. Sustainability. 2024;16(3):1295. doi:10.3390/su16031295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. Espuny M, da Mota Reis JS, Giupponi ECB, Rocha ABT, Costa ACF, Poltronieri CF, et al. The role of the triple helix model in promoting the circular economy: government-led integration strategies and practical application. Recycling. 2025;10(2):50. doi:10.3390/recycling10020050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Rossoni AL, de Vasconcellos EPG, de Castilho Rossoni RL. Barriers and facilitators of university-industry collaboration for research, development and innovation: a systematic review. Manag Rev Q. 2024;74(3):1841–77. doi:10.1007/s11301-023-00349-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Sayles J. Capacity building for AI actors. In: Principles of AI governance and model risk management. Berkeley, CA, USA: Apress; 2024. p. 321–31. doi:10.1007/979-8-8688-0983-5_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Cerf ME. Health research, development and innovation capacity building, enhancement and sustainability. Discov Soc Sci Health. 2023;3(1):18. doi:10.1007/s44155-023-00051-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Stojic S, Salhofer S. Capacity development for plastic waste management—a critical evaluation of training materials. Sustainability. 2022;14(4):2118. doi:10.3390/su14042118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Jensen HH. Data-driven circularity—the brain of a circular economy. In: Circular economy opportunities and pathways for manufacturers. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature; 2025. p. 389–412. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-75279-7_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

103. Teclaw W, O’Donnel J, Kukkonen V, Pauwels P, Labonnote N, Hjelseth E. Federating cross-domain BIM-based knowledge graph. Adv Eng Inform. 2024;62:102770. doi:10.1016/j.aei.2024.102770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Roberts H, Zhang J, Bariach B, Cowls J, Gilburt B, Juneja P, et al. Artificial intelligence in support of the circular economy: ethical considerations and a path forward. AI Soc. 2024;39(3):1451–64. doi:10.1007/s00146-022-01596-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Maheshwari C. Beyond proprietary: how open-source software accelerates machine learning innovation. Int J Sci Technol. 2025;16(1):3018. doi:10.71097/ijsat.v16.i1.3018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

106. Buckingham Shum S, Aberer K, Schmidt A, Bishop S, Lukowicz P, Anderson S, et al. Towards a global participatory platform: democratising open data, complexity science and collective intelligence. Eur Phys J Spec Top. 2012;214(1):109–52. doi:10.1140/epjst/e2012-01690-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

107. Keränen O, Lehtimäki T, Komulainen H, Ulkuniemi P. Changing the market for a sustainable innovation. Ind Mark Manag. 2023;108(8):108–21. doi:10.1016/j.indmarman.2022.11.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Hussain S, Akhter R, Maktedar SS. Advancements in sustainable food packaging: from eco-friendly materials to innovative technologies. Sustain Food Technol. 2024;2(5):1297–364. doi:10.1039/d4fb00084f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Moshood TD, Nawanir G, Mahmud F, Mohamad F, Ahmad MH, AbdulGhani A, et al. Green product innovation: a means towards achieving global sustainable product within biodegradable plastic industry. J Clean Prod. 2022;363(44):132506. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. Farghali M, Osman AI. Revolutionizing waste management: unleashing the power of artificial intelligence and machine learning. In: Advances in energy from waste. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2024. p. 225–79. doi:10.1016/b978-0-443-13847-8.00007-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]