Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Improving the Performance of AI Agents for Safe Environmental Navigation

Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and Computer Science, Jackson State University, Jackson, MS 39217, USA

* Corresponding Author: Khalid H. Abed. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2025, 7, 615-632. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2025.073535

Received 20 September 2025; Accepted 06 November 2025; Issue published 01 December 2025

Abstract

Ensuring the safety of Artificial Intelligence (AI) is essential for providing dependable services, especially in various sectors such as the military, education, healthcare, and automotive industries. A highly effective method to boost the precision and performance of an AI agent involves multi-configuration training, followed by thorough evaluation in a specific setting to gauge performance outcomes. This research thoroughly investigates the design of three AI agents, each configured with a different number of hidden units. The first agent is equipped with 128 hidden units, the second with 256, and the third with 512, all utilizing the Proximal Policy Optimizer (PPO) algorithm. Importantly, all agents are trained in a uniform environment using the Unity simulation platform, employing the Machine Learning Agents Toolkit (ML-agents) in conjunction with the PPO algorithm enhanced by an Intrinsic Curiosity Module (PPO + ICM). The main aim of this study is to clearly highlight the benefits and limitations of increasing the number of hidden units. The results convincingly show that expanding the hidden units to 512 leads to a notable 50% enhancement in the agent’s Goal (G) and a substantial 50% decrease in the Collision (C) value. This study offers a detailed analysis of how the number of hidden units affects AI agent performance using the Proximal Policy Optimizer (PPO) algorithm, augmented with an Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM). By systematically comparing agents with 128, 256, and 512 hidden units in a controlled Unity environment, the research provides valuable insights into the connection between network complexity and task performance. The consistent use of the ML-Agents Toolkit ensures a standardized training process, facilitating direct comparisons between the different configurations.Keywords

The incorporation of Artificial Intelligence (AI) has greatly improved our daily lives by autonomously performing a variety of tasks, thus reducing the necessity for human involvement. However, AI systems can still make mistakes that might lead to serious repercussions. For example, autonomous systems can be designed to locate or transport objects to designated areas, highlighting the critical need for meticulous supervision during their use. To maintain safety, it is crucial that these systems are equipped with the right hardware and software. This will enable them to navigate their surroundings safely and effectively, thereby preventing accidents.

Trust, Risk, and Security Management (TRISM), specifically Artificial Intelligence TRiSM (AI TRiSM), constitutes a vital governance framework aimed at addressing the distinct ethical, safety, and security challenges associated with the swift integration of AI systems. This framework is generally founded on key pillars, including Explainability (ensuring transparent decision-making), ModelOps (governance and monitoring of models in production), AI Application Security (safeguarding the AI pipeline from adversarial attacks), and Privacy (protecting sensitive training and input data). The complexity of governance has significantly increased with the advent of autonomous systems, necessitating a precise distinction in agent terminology. AI agents operate within a goal-oriented paradigm, wherein the AI system is capable of autonomous reasoning, multi-step planning, and adaptive execution to achieve a high-level objective, often employing multiple AI agents. The primary TRISM concern with AI agents is the unprecedented accountability gap engendered by their autonomy: a minor error can rapidly escalate into severe consequences, outpacing human intervention. Specific risks include Goal Hijacking (manipulating the agent’s intent via prompt injection), Lateral Movement (agents with excessive privileges escalating a security breach across the network), and Emergent Harmful Behavior due to the system’s capacity to generate novel, unpredicted plans. Recent scholarly discourse is increasingly concentrating on governance for agent actions, not merely their outputs, advocating for Zero Trust principles for agents, mandating tamper-evident audit logs for every tool call, and establishing Human-in-the-Loop checkpoints for irreversible or high-risk autonomous decisions, thereby transitioning from passive risk management to proactive Agentic Governance Councils [1–3].

To effectively tackle these challenges, one of the most dependable strategies is to integrate AI safety algorithms, such as the conflict-aware safe reinforcement learning (CAS-RL) algorithm [1], into autonomous systems. The successful application of AI safety protocols in ensuring safety has been illustrated through the use of the Reinforcement Learning (RL) algorithm [2]. AI has become an integral part of our daily lives, enhancing efficiency and improving various processes. It automates numerous tasks, thereby increasing productivity and ensuring smooth operations. However, the increased reliance on AI also brings potential risks that must be carefully considered and managed. The potential for AI-induced errors, particularly in critical areas like autonomous agents responsible for identification or transportation, highlights the necessity for strong safety measures and vigilant oversight during their deployment and operation.

To address these concerns and ensure the safe operation of AI systems, particularly autonomous agents, it is crucial to implement comprehensive safety protocols. This includes equipping the agents with appropriate hardware and software that enable them to navigate their environments safely and effectively prevent accidents. Advanced AI safety algorithms, such as the conflict-aware safe reinforcement learning (CAS-RL) algorithm [1], have emerged as promising solutions to enhance the safety and reliability of autonomous systems. The effectiveness of these AI safety measures has been demonstrated through the application of RL algorithms in safety exploration [2]. By incorporating these advanced safety mechanisms, we can work towards maximizing the benefits of AI integration while minimizing potential risks and ensuring responsible deployment of autonomous technologies.

This algorithm facilitates the training of an agent within a defined environment, encouraging the exploration of new areas by providing rewards for successful navigation [3]. During the training process, the agent engages in a variety of actions and behaviors, which may include encountering obstacles or experiencing simulated failures, such as collisions.

RL algorithms find applications in a wide range of real-world contexts, such as autonomous vehicles, robotic cleaning devices, military and delivery drones, and various consumer-focused technologies. During the training process, these algorithms improve the agent’s capabilities while reducing risks by using a specific punishment function to deter unsafe or inappropriate actions. An RL algorithm can effectively enhance the agent’s performance through a clearly defined reward function [4]. It is crucial for the intelligent agent to be encouraged for achieving positive results and guided to avoid undesirable actions. To ensure safety and prevent any potential physical harm during training or testing, it is advisable to use adaptable tools like Virtual Reality (VR) environments for model training [5,6].

A team of researchers from esteemed institutions like Google, OpenAI, UC Berkeley, and Stanford has collaboratively identified five significant challenges in the realm of artificial intelligence (AI) safety [7]. These challenges are: (1) minimizing negative side effects, (2) preventing reward manipulation, (3) creating scalable oversight frameworks, (4) promoting safe exploration, and (5) ensuring resilience to distributional shifts. The researchers suggest that these challenges originate from three primary issues: (i) the design of flawed objective functions, (ii) the substantial cost of regularly assessing these functions, and (iii) undesirable behaviors during the learning process. To address these AI safety challenges, several proposed solutions employ Reinforcement Learning (RL) techniques. The researchers’ thorough investigation included Machine Learning (ML), RL, safe exploration strategies, and AI safety principles in relation to these five challenges [7]. In our research, we have developed two innovative strategies to tackle these challenges. The first strategy uses the Machine Learning Agents Toolkit (ML-Agents) [8] to train an intelligent agent with the Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) algorithm and an Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM) [9]. This approach aims to enhance the agent’s learning and exploration capabilities. The second strategy involves human intervention to guide the agent towards its target, providing a more controlled and supervised learning environment. Our research focuses on addressing two of the five identified challenges: minimizing negative side effects and promoting safe exploration by teaching the agent to ignore non-goal objects and navigate around obstacles. The human-guided method demonstrates higher accuracy in obstacle avoidance, as it allows for direct control over the agent’s movement towards the goal, eliminating the need for ML-Agent toolkits. In the first method, we utilized the ML-Agents Toolkit to train the agent using a combination of the Proximal Policy Optimizer and Intrinsic Curiosity Module (PPO + ICM) within a virtual reality (VR) environment. This training aims to improve the agent’s ability to avoid obstacles, find alternative paths, and disregard non-goal objects while navigating its environment. The primary goal of this training is to enhance AI safety by reducing or preventing errors that could lead to dangerous collisions involving the intelligent agent.

To validate our research findings and assess the efficacy of our proposed methodologies, we conducted a series of four experiments utilizing the Unity environment and ML agents. These experiments were designed to test and execute the formulated algorithm, providing empirical evidence to support our hypotheses and evaluate the performance of our AI safety enhancement techniques. This algorithm employs RL to train an agent within a specific environment, encouraging exploration through reward-based navigation. The agent performs various actions during the training process, including encountering obstacles and experiencing simulated failures like collisions. RL algorithms find diverse real-world applications in self-driving vehicles, robotic cleaning systems, military and delivery drones, and consumer-oriented applications. These algorithms improve the agent’s performance during training while minimizing risks by implementing a punishment function that discourages inappropriate or dangerous behavior. The effectiveness of the RL algorithm relies on a well-defined reward function that encourages positive outcomes and guides the agent away from undesirable behaviors [3,4].

To ensure safety and prevent physical damage during training or testing, the use of Virtual Reality (VR) environments is recommended for model training [5,6]. Researchers from prominent institutions have identified five key problems in AI safety: preventing negative side effects, avoiding rewards hacking, implementing scalable oversight, enabling safe exploration, and ensuring robustness to distributional shift [7]. These issues stem from incorrect objective functions, costly evaluation of objective functions, and undesirable behavior during the learning process. Many proposed solutions to address these AI safety concerns involve RL techniques. The research presented here explores two distinct approaches: one using the Machine Learning Agents Toolkit (ML-Agents) with the PPO algorithm and an Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM) [8,9], and another requiring human intervention to guide the agent. Both methods aim to solve two of the five identified problems: avoiding negative side effects and exploring safely by ignoring non-goal objects and evading obstacles.

This study frames its investigation around two research questions:

Q1: Which hidden units 256 or 512 are the best to minimize the number of collisions for an autonomous explorer agent?

Q2: What are the differences between using 256 and 512 hidden units in training the agent?

The rest of the paper is constructed as follows: Section 2 discusses the relevant related works research method. In Section 3, we present the proposed methodology and the tools. Section 4 presents the results, and Section 5 presents the discussion. The paper’s structure follows a logical progression, beginning with a review of relevant literature and research methods in Section 2. This section likely provides context for the study, highlighting previous work in the field and identifying gaps in current knowledge. It may also outline the theoretical framework underpinning the research and justify the chosen methodological approach. Section 3 delves into the core of the research, detailing the proposed methodology and tools employed. This section is crucial for understanding the study’s design, data collection methods, and analytical techniques. It may include descriptions of experimental setups, survey instruments, or computational models used. The tools mentioned could range from statistical software to specialized equipment, depending on the nature of the research. Sections 4 and 5 focus on the outcomes and their interpretation. The results section highlights a remarkable 50% improvement in the agent’s Goal (G), which signifies the final destination the agent is expected to reach, along with a significant 50% reduction in the Collision (C) value, indicating the number of faults encountered by the agents while navigating to the final destination G. Further details are provided in the results section. The discussion section then interprets these results, exploring their implications, relating them back to the initial research questions, and contextualizing them within the broader field of study.

RL is a distinct area of machine learning that can autonomously gather data without requiring any human input. This ability greatly speeds up the ML process by reducing the amount of time needed. RL functions by collecting information based on the actions and behaviors of agents operating in each environment. This methodology not only improves the model’s durability but also adds to its overall strength. For example, a proficient reinforcement learning (RL) model is adept at modifying its actions in response to the current state, thereby enabling dynamic and efficient control. An RL-trained robot, for instance, can finely tune its grip force in accordance with the weight and texture of an object, ensuring the successful execution of a task. RL has experienced significant success in managing various agents and is acknowledged as the pioneering deep learning model that can learn control policies directly from complex sensory data using reinforcement learning methods [10]. RL has demonstrated its capabilities in various games, including Go [11], StarCraft2 [12], and in managing multiplayer games [13]. AI has significantly enhanced various technologies and influenced human lifestyles. Nonetheless, it must prioritize safety and be free of risks to provide greater assistance [14]. AI must maintain stability and continuously observe the behavior of the agent within each environment [15]. Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) were applied to minimize the risks associated with autonomous navigation [16]. An important area of reinforcement learning focuses on developing an agent capable of navigating safely and doing what others may typically do in the kitchen to learn how to act in the kitchen [17].

Our group has carried out and released multiple research studies aimed at improving AI safety protocols and minimizing the hazards linked to the secure exploration and navigation of autonomous agents [18–20]. The PPO algorithm is an advanced reinforcement learning approach created by OpenAI that can be effectively applied with ML agents to build reliable AI safety systems. The agent developed can manage various reinforcement learning situations, including intricate games like hide-and-seek [21]. Additionally, the agent is capable of outperforming other agents in the 8-bit gaming realm [22]. Furthermore, the PPO algorithm has been utilized in a real-time setting to operate an autonomous system [23].

This study intends to demonstrate the impact of varying the number of hidden units (128, 256, and 512) within the PPO algorithm in a single environment. It employs three distinct approaches to manage the RL agent: the first approach utilizes an AI controller with a PPO algorithm featuring 128 hidden units, the second one includes 256 hidden units, and the final method incorporates 512 hidden units. Expanding the number of hidden units in a neural network from 128 to 256 to 512 significantly enhances the model’s capacity to learn and represent complex policies and value functions. This increase in network size allows for a more intricate internal representation of the problem space, enabling the model to capture subtle patterns and relationships within the data. With more hidden units, the network can form a larger number of feature detectors, each potentially specializing in different aspects of the input, leading to a more nuanced understanding of the environment or task at hand. However, it’s important to note that while increasing the number of hidden units can potentially improve performance, it also comes with trade-offs. A larger network requires more computational resources and may be more prone to overfitting, especially if the training data is limited. Additionally, the increased complexity may lead to longer training times and potentially more difficult optimization. Therefore, the decision to increase hidden units should be balanced with considerations of available data, computational resources, and the specific requirements of the task being addressed. The agent will undergo training in the same environment for all three approaches. By observing and learning from the actions and behaviors of agents within specific environments, RL models can rapidly improve their performance without human intervention. This approach not only enhances the efficiency of the learning process but also contributes to the development of more robust and versatile AI systems. The robustness and versatility of the RL model’s policy is evident in its capacity to sustain high performance despite minor perturbations in input (state/observation) or alterations in environmental dynamics. RL agents, particularly those trained using techniques such as domain randomization or within diverse simulations, develop the ability to withstand noise and minor variations, thereby enhancing their resilience in real-world applications. The success of RL has been demonstrated across various domains, from complex board games like Go to real-time strategy games such as StarCraft2, showcasing its ability to master intricate decision-making processes and adapt to dynamic environments [10–13].

As AI technologies continue to evolve and integrate into various aspects of human life, the focus on safety and risk mitigation has become paramount [14,15]. Researchers have employed sophisticated techniques like Markov Decision Processes (MDPs) to enhance the safety of autonomous navigation systems [16]. Additionally, efforts are being made to develop RL agents capable of safely navigating and performing tasks in everyday environments, such as kitchens, mimicking human behavior to learn appropriate actions [17]. The development of advanced algorithms like the PPO by OpenAI has further propelled the field, enabling the creation of more reliable AI safety systems. These systems have shown remarkable performance in diverse scenarios, from complex games to real-time autonomous operations [21–23]. The ongoing research, including studies on varying the number of hidden units in the PPO algorithm, aims to refine and optimize these systems, pushing the boundaries of what AI can achieve while maintaining a strong focus on safety and reliability.

The primary advantage of employing RL is that it removes the necessity for pre-prepared training data, which can often be time-consuming and difficult to obtain. Instead of relying on static datasets, we focus on developing a dynamic virtual environment using Unity3D, where our agents can freely explore and learn through interaction. In this virtual environment, we will train our agents using a variety of scenarios that simulate real-world challenges, allowing them to adapt and improve their decision-making abilities.

Once the training process is complete, we will utilize the PPO algorithm to evaluate the performance of the trained agents within the same environment. This method ensures that our evaluation is consistent with the conditions they were trained under. Throughout our study, we will experiment with different configurations by varying the number of units in our agents. This will enable us to assess how changes in capacity affect their performance across a range of scenarios. We will also provide a detailed explanation of the settings and parameters required to effectively implement the PPO algorithm, ensuring clarity for future researchers looking to replicate our methodology. Finally, we will systematically compare the outcomes generated by the PPO algorithm, meticulously analyzing the performance of the agents under each variable condition. This comprehensive approach will help us draw meaningful conclusions about the efficacy of RL and the PPO algorithm in training autonomous agents within our designed environment. The utilization of RL in this study offers a significant advantage by eliminating the need for pre-prepared training data. Instead, the focus is on creating a dynamic virtual environment using Unity3D, where agents can explore and learn through interaction. This approach allows for the simulation of real-world challenges, enabling agents to adapt and improve their decision-making abilities in a more organic and flexible manner. The training process is followed by an evaluation phase using the PPO algorithm, ensuring consistency between the training and testing conditions.

The research methodology involves experimenting with various agent configurations by altering the number of units, providing insights into how capacity changes affect performance across different scenarios. A detailed explanation of the PPO algorithm’s implementation settings and parameters will be provided, facilitating replication by future researchers. The study culminates in a systematic comparison of outcomes generated by the PPO algorithm, with a meticulous analysis of agent performance under variable conditions. This comprehensive approach aims to yield meaningful conclusions about the effectiveness of RL and the PPO algorithm in training autonomous agents within the designed virtual environment, potentially advancing the field of artificial intelligence and autonomous systems. The primary metric for performance evaluation utilized in this study is the Goal to Collision Ratio (GC-ratio). In application-specific contexts, such as those involving autonomous agents, the GC-ratio serves as a direct indicator of an agent’s efficacy in navigating its environment. The GC-ratio is determined by counting the two pertinent events over a specified period, a fixed number of episodes, or throughout the entire training duration. Further details are provided in Section 3.2.

3.1 Unity Environment and ML-Agents

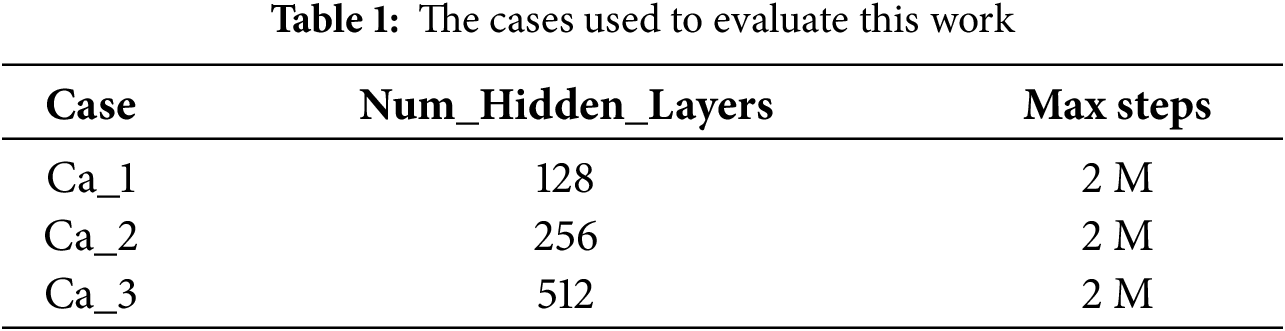

We developed our virtual environment using the Unity game engine and integrated it with ML-agents release 12 to enhance its functionality. Unity’s design as a real-time game engine prioritizes dynamic interaction and performance optimization over precise measurement tools. This focus allows developers to create immersive, interactive experiences that can be rendered in real-time across various platforms. While Unity lacks a built-in measurement feature, it provides a robust set of tools for creating and manipulating 3D environments, including a coordinate system, transform components, and scripting capabilities. To optimize our agent’s performance, we conducted extensive training, running 2 million iterations for each specific case. This rigorous process allowed us to fine-tune the agent’s behavior effectively. Table 1 offers a detailed breakdown of the number of hidden units used in the PPO algorithm across the three cases we explored in our research. This information is crucial for understanding the configuration and capacity of our neural network models in relation to their performance.

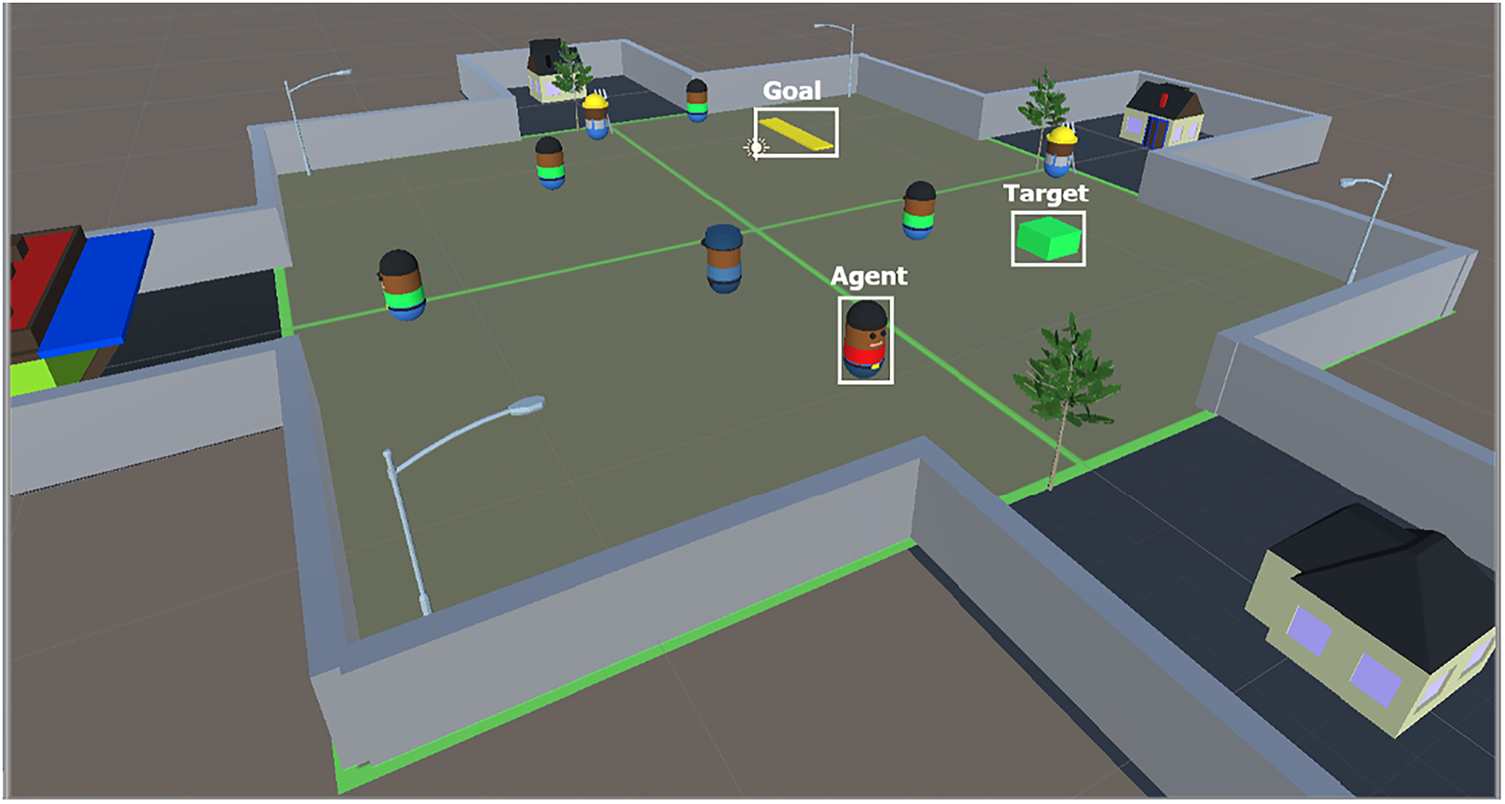

Fig. 1 showcases Unity alongside our virtual environment designed for training the agent. The scene includes four individuals in green shirts, two workers wearing yellow helmets, a police officer with a blue hat, and our controlled Agent in a red shirt. The target is marked by a green box and encircled by a white square. We have highlighted the goal with a yellow rectangular area within a white rectangle.

Figure 1: Unity3D virtual environment used to implement the proposed model

3.2 Goal Collision Ratio (GC-Ratio)

The Goal (G) Collision (C) ratio, or GC-ratio, serves as a crucial metric for evaluating the frequency of collisions between our agent and obstacles, which include other agents or walls. Despite being programmed to avoid obstacles, our agent may occasionally encounter them on its path to the goal. Nevertheless, it ultimately reaches its target. The GC-ratio metric aids in determining the ratio value for instances where our agent encounters barriers. In our work, we calculate the GC-ratio using Eq. (1).

Eq. (1) is used to calculate the GC-ratio for each round. In this formula, K is assigned a value of 0.001 to prevent any potential issues from division by zero. The variable C denotes the total number of errors made by the agent, including collisions, while G represents the total number of successful goal completions by the agent. The GC-ratio is recalibrated each time the agent either achieves a new goal or encounters a collision, with updates made accordingly.

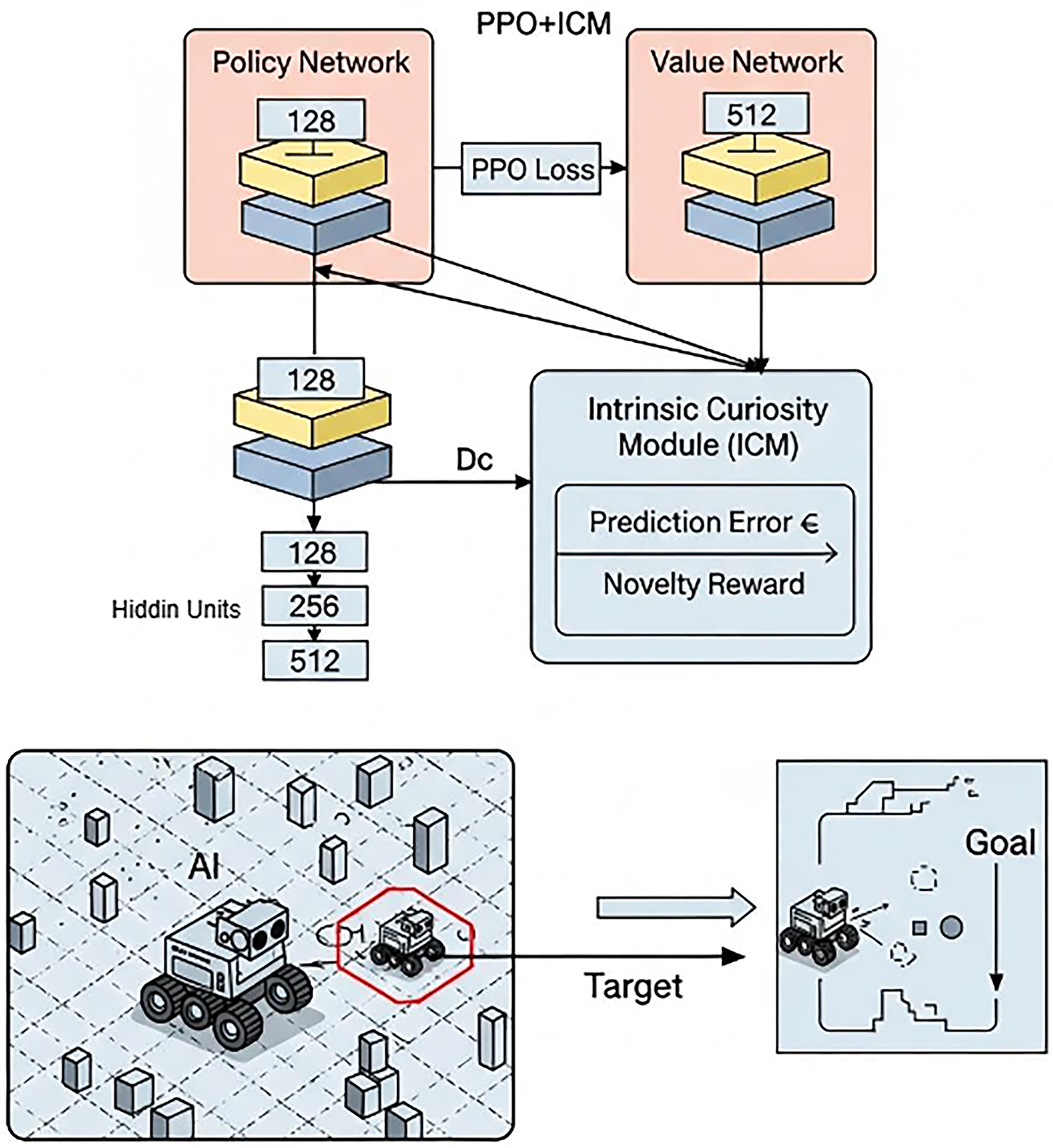

In this study, we developed and evaluated three distinct configurations for controlling the agent, each employing the PPO algorithm. The first configuration incorporates 128 hidden units, enabling the agent to learn and adapt to its environment at a fundamental level. The second configuration increases complexity by utilizing 256 hidden units, thereby enhancing the agent’s capacity to process information and make more nuanced decisions. The final configuration employs 512 hidden units, maximizing the agent’s ability to capture intricate patterns and strategies within its environment. Each configuration was systematically assessed to determine its effectiveness in controlling the agent’s behavior through the PPO algorithm. The varying number of hidden units allowed us to observe how changes in model complexity influence the agent’s performance. Fig. 2 provides a visual representation of these three configurations, illustrating the differences in architecture employed in our experiments. This detailed comparison contributes to a deeper understanding of the relationship between neural network complexity and agent performance in reinforcement learning scenarios.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the three cases involving PPO agents with 128, 256, and 512 hidden units

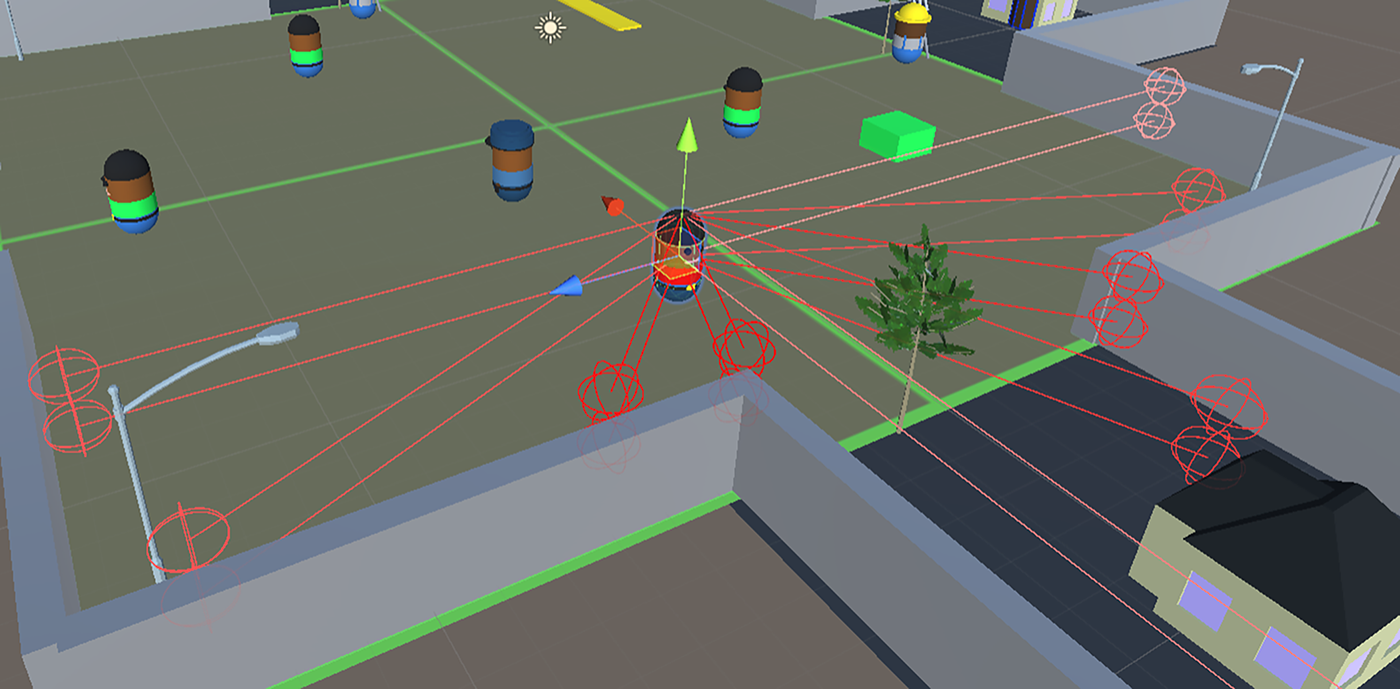

The agent is equipped with Ray Perception Sensors, positioned at a 90-degree angle. This strategic configuration enables the agent to accurately measure the distance to nearby obstacles, thereby enhancing situational awareness. The Ray Perception Sensors detect obstacles, and the ICM provides intrinsic rewards to encourage safe exploration. This system of checks and balances is designed to inspire the agent to glide through its environment with grace and precision, avoiding unnecessary collisions. For a visual symphony, Fig. 3 unveils the operational range of the Ray Perception Sensors, showcasing the expansive coverage area for obstacle detection. This intricate feedback mechanism is the cornerstone for honing the agent’s prowess and enhancing its ability to engage with complex environments. The Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM) represents a significant advancement in reinforcement learning by enhancing the processes related to agent exploration. When integrated with the ICM with the PPO algorithm, the ICM is shown to improve PPO’s performance. By providing the agent with intrinsic reward signals, the ICM encourages thorough exploration of the environment and promotes the selection of safer pathways. The Intrinsic Curiosity Module (ICM) represents a significant advancement in reinforcement learning by enhancing the processes related to agent exploration. When integrated with the PPO algorithm, the ICM has been shown to improve PPO’s performance substantially. By providing the agent with intrinsic reward signals, the ICM encourages thorough exploration of the environment and promotes the selection of safer pathways.

Figure 3: Measuring the distance between the AI agent and the surrounding environment using the ray perception sensor

This intrinsic motivation drives the agent to seek out novel experiences and states within the environment, effectively addressing the exploration-exploitation dilemma that is common in reinforcement learning tasks.

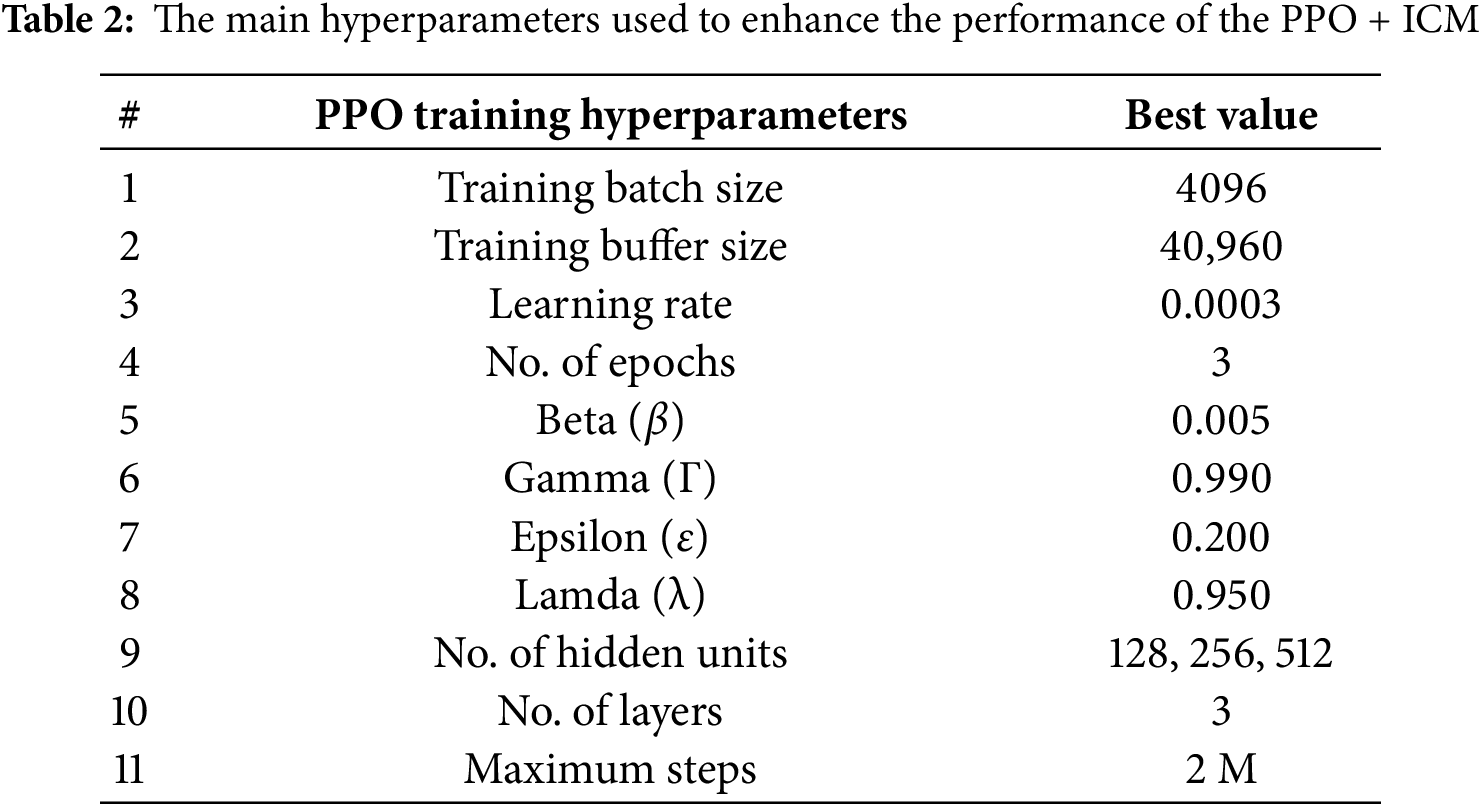

The combination of ICM and PPO creates a powerful learning framework that balances efficient policy updates with curiosity-driven exploration. The ICM generates intrinsic rewards based on the agent’s ability to predict the consequences of its actions, encouraging it to explore areas of the environment where its predictions are less accurate. This approach is particularly beneficial in environments with sparse extrinsic rewards, where traditional reinforcement learning methods may struggle to find optimal policies. By incorporating the ICM, agents can discover useful behaviors and strategies that might otherwise be overlooked, leading to more robust and adaptable learning outcomes. Additionally, the promotion of safer pathways through intrinsic rewards can result in more stable and reliable agent behavior, which is crucial in real-world applications where safety considerations are paramount. Table 2 displays the PPO algorithm and ICM configuration hyperparameters. The batch_size parameter indicates the quantity of input data given to the neural network in a single iteration. The buffer_size parameter represents the amount of data necessary to commence the learning model update or to start the training procedure. The buffer_size is equivalent to 40,960, 10 times the batch_size of 4096. The beta value promotes the agent’s exploration of new areas during training. Generalized Advantage Estimate (GAE) [24] utilizes Lamda (λ) to estimate PPO algorithm features. We have implemented a maximum of three layers in our model architecture. The training process will be conducted over 2 million steps, incorporating 128, 256, and 512 hidden units across all cases presented in this study. The PPO algorithm and ICM configuration hyperparameters outlined in Table 2 play a crucial role in optimizing the learning process. The batch_size of 4096 determines the volume of input data processed by the neural network in each iteration, while the buffer_size of 40,960 represents the threshold of data accumulation required to initiate the model update or training procedure. This 10:1 ratio between buffer_size and batch_size ensures a balance between data collection and processing efficiency. The beta value serves as a key factor in encouraging the agent to explore new territories during the training phase, promoting a more comprehensive learning experience.

The implementation of Generalized Advantage Estimate (GAE) with its Lambda (λ) parameter enhances the estimation of PPO algorithm features, contributing to more accurate and stable learning.

The model architecture incorporates a maximum of three layers, striking a balance between complexity and computational efficiency. The training process is designed to span 2 million steps, allowing for thorough exploration and refinement of the model’s performance. The study investigates various configurations with hidden units of 128, 256, and 512, enabling a comprehensive analysis of the model’s behavior and performance across different levels of neural network capacity. This systematic approach to hyperparameter configuration and model architecture design aims to optimize the learning process and achieve robust results in the given task.

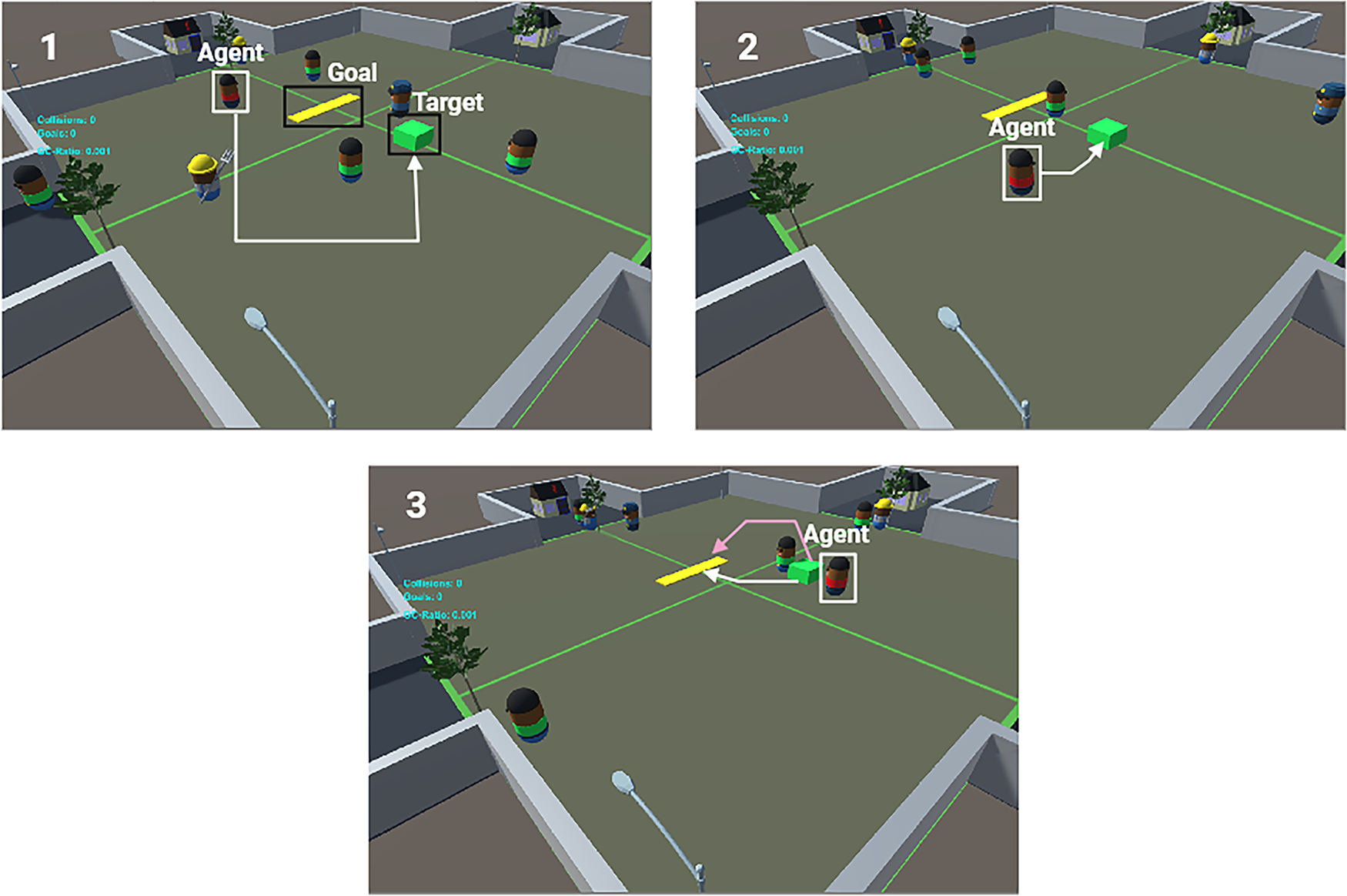

We have developed a comprehensive training environment using the Unity game engine to enhance the training of our agents. At the commencement of the training session, the agent is assigned a specific task to identify a target that is visually indicated by a green box within a designated area. Once the agent successfully identifies the target, it must then navigate through the environment to transport the target to a designated goal area, which is indicated by a yellow-filled rectangle. This process not only tests the agent’s ability to recognize and locate the target but also evaluates its navigation and transport skills within the training simulation.

Fig. 4 shows different stages. In Fig. 4 (1), we see the starting positions of the Agent, target, and Goal. An arrow shows the best way to find the target. After the Agent finds the target, it plans a path to move the target to the goal, as seen in Fig. 4 (2). In Fig. 4 (3), the Agent has two choices: one path is white, and the other is pink. Alternatively, the Agent may choose to wait for another agent (agents with green shirt in Fig. 4) to proceed, enabling a direct approach to driving the target to the goal. In this environment, all agents can interact with one another. Our Agent is equipped with sensors to assist in detecting obstacles and making informed decisions regarding path alterations or the option to wait. This controlled setting enables us to develop a robust model capable of navigating complex scenarios and effectively avoiding barriers. In this context, obstacles may obstruct the Agent’s route to the target, necessitating that the Agent evaluate alternative pathways or choose to remain stationary until the route is clear.

Figure 4: The agent navigating in the unity environment. (1) The path to the goal during the training. (2) The target has been acquired by the AI agent. (3) Three options the AI agent have: navigate in the white or pink path, wait for the worker to pass, or proceed to the goal

We are currently conducting a performance evaluation of our agent across three distinct scenarios, each utilizing an AI controller that employs a PPO algorithm with varying configurations of hidden units: 128, 256, and 512.

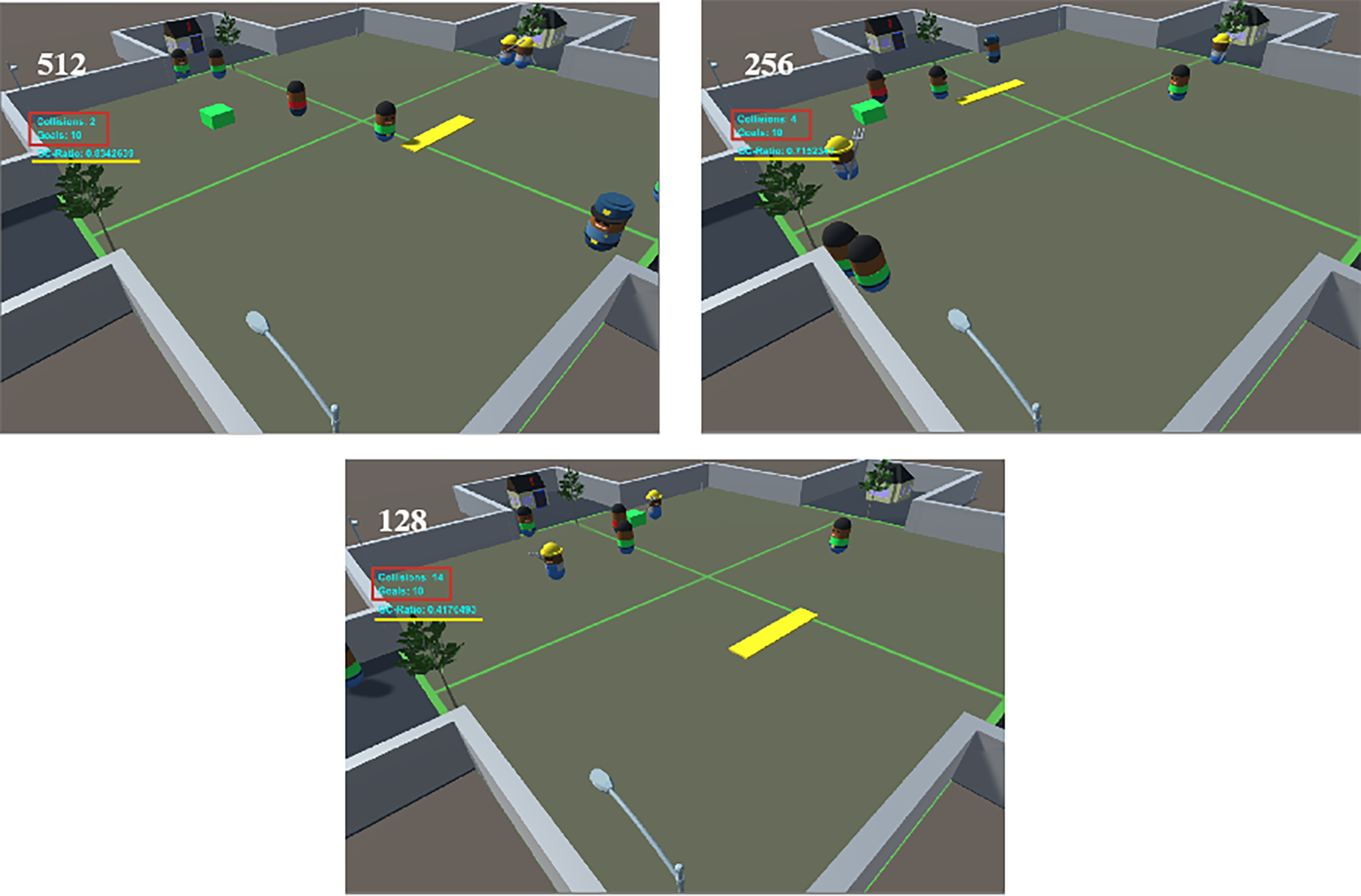

In numerous instances, the agent is able to safely explore its environment, avoiding collisions with walls and other obstacles, while being effectively guided toward its intended destination. The AI employs a search algorithm to identify the target and navigate toward the goal with precision. We have conducted a series of trials, successfully completing 10 goals across the three scenarios. Throughout this process, we measured key performance indicators, including the goal, collision, and Goal Collision (GC-ratio). Fig. 5 shows a comparison of goals achieved and collisions for three scenarios. We tested our agents with different numbers of hidden units. The first agent, Ca_1, had 128 hidden units. It reached 10 goals but had 14 collisions, giving a GC-ratio of 0.417, as seen in Fig. 5 (128). The second agent, Ca_2, had 256 hidden units. It also reached 10 goals but had only 4 collisions, resulting in a better GC-ratio of 0.715, all in less than a minute, as shown in Fig. 5 (256). The third agent, Ca_3, had 512 hidden units. It achieved 10 goals with just 2 collisions, also in under a minute, as highlighted in Fig. 5 (512). These results suggest that more hidden units can improve agent performance. Ca_2 and Ca_3 had fewer collisions and higher GC-ratios than Ca_1. This means adding more hidden units might help our agents in this environment. Next, we will look at the training results of all three agents to see which one performed best at the start. Fig. 5 shows the goals and collisions for Ca_1 (128), Ca_2 (256), and Ca_3 (512). We marked the goals and collisions with a red rectangle and added a yellow line under the GC-ratio. The agent’s performance in three scenarios uses an AI controller with a PPO algorithm and different hidden unit setups: 128, 256, and 512. The agent is good at exploring its environment, avoiding obstacles, and reaching its destination using a search algorithm.

Figure 5: Comparison between the number of the achieved goals and collisions (bounded in red color box), and GC-ratio value (yellow line) for the three cases

The evaluation process involved completing 10 goals across three scenarios, measuring key performance indicators such as goal achievement, collision frequency, and Goal Collision (GC-ratio). The results reveal a clear correlation between the number of hidden units and agent performance. The agent with 128 hidden units (Ca_1) achieved 10 goals but incurred 14 collisions, resulting in a GC-ratio of 0.417. In contrast, the agent with 256 hidden units (Ca_2) maintained the same goal achievement while significantly reducing collisions to 4, improving the GC-ratio to 0.715. The agent with 512 hidden units (Ca_3) further optimized performance, achieving 10 goals with only 2 collisions. Both Ca_2 and Ca_3 completed their tasks in under one minute, demonstrating enhanced efficiency. These findings suggest that increasing the number of hidden units leads to improved agent performance, particularly in terms of collision avoidance and overall efficiency. The study’s next steps involve visualizing the training results to determine which configuration yielded the highest performance during the initial training phase, potentially guiding future optimizations in agent design and implementation.

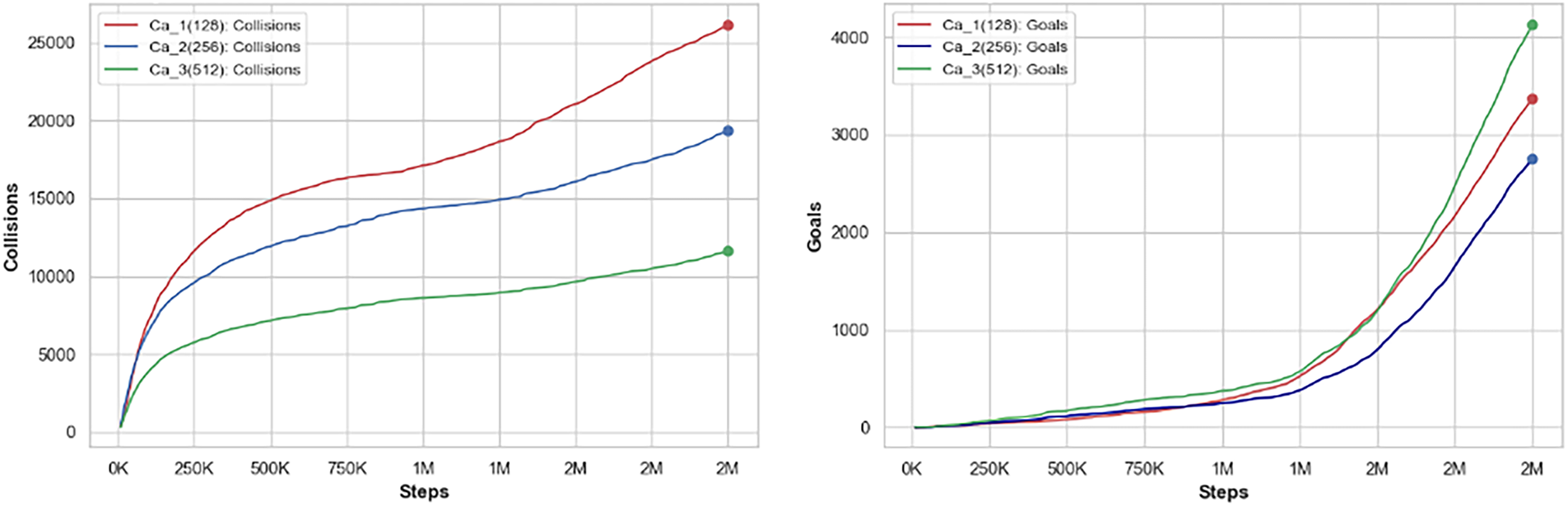

We conducted a comprehensive analysis of the training data for three distinct agents, each representing a different case in our study. Case 1 (denoted as Ca_1) was configured with 128 hidden units, Case 2 (Ca_2) utilized 256 hidden units, and Case 3 (Ca_3) implemented 512 hidden units. To facilitate data analysis and comparison among these cases, we exported all relevant information into a comma-separated values (CSV) file, which allows for straightforward visualization of the results. Fig. 6 shows a detailed comparison of training metrics, focusing on goals and collisions for three setups. Each setup has a different color: Case 1 (Ca_1) is red, Case 2 (Ca_2) is blue, and Case 3 (Ca_3) is green. We found that increasing the number of hidden units from 128 in Case 1 to 512 in Case 3 improved results. There were fewer collisions and more goals achieved.

Figure 6: A comparison between the goals and collisions, for every training step for Case 1 (Ca_1) 128 hidden units, Case 2 (Ca_2) 256 hidden units, and Case 3 (Ca_3) 512 hidden units

The results of our analysis revealed an interesting pattern regarding the performance of different configurations of hidden units in our model. Specifically, Case 2, which utilized 256 hidden units, exhibited a weak performance in goal scoring when compared to Case 1, which had a different configuration. This outcome was unexpected, as our initial hypothesis posited that an increase in the number of hidden units would inherently improve performance across all metrics. In contrast, Case 3 proved to be significantly more effective. With a total of 512 hidden units, it not only rectified the shortcomings displayed by Case 1, but it also outperformed Case 2 by a notable margin. This improvement in performance underscores the importance of the number of hidden units in influencing the efficiency of the agent within our specific environment. The findings suggest that there is an optimal range for hidden units, where too few can hinder performance, while a well-tuned larger number appears to enhance the agent’s ability to score and navigate challenges effectively. This highlights the need for careful consideration when designing neural architectures to maximize agent performance.

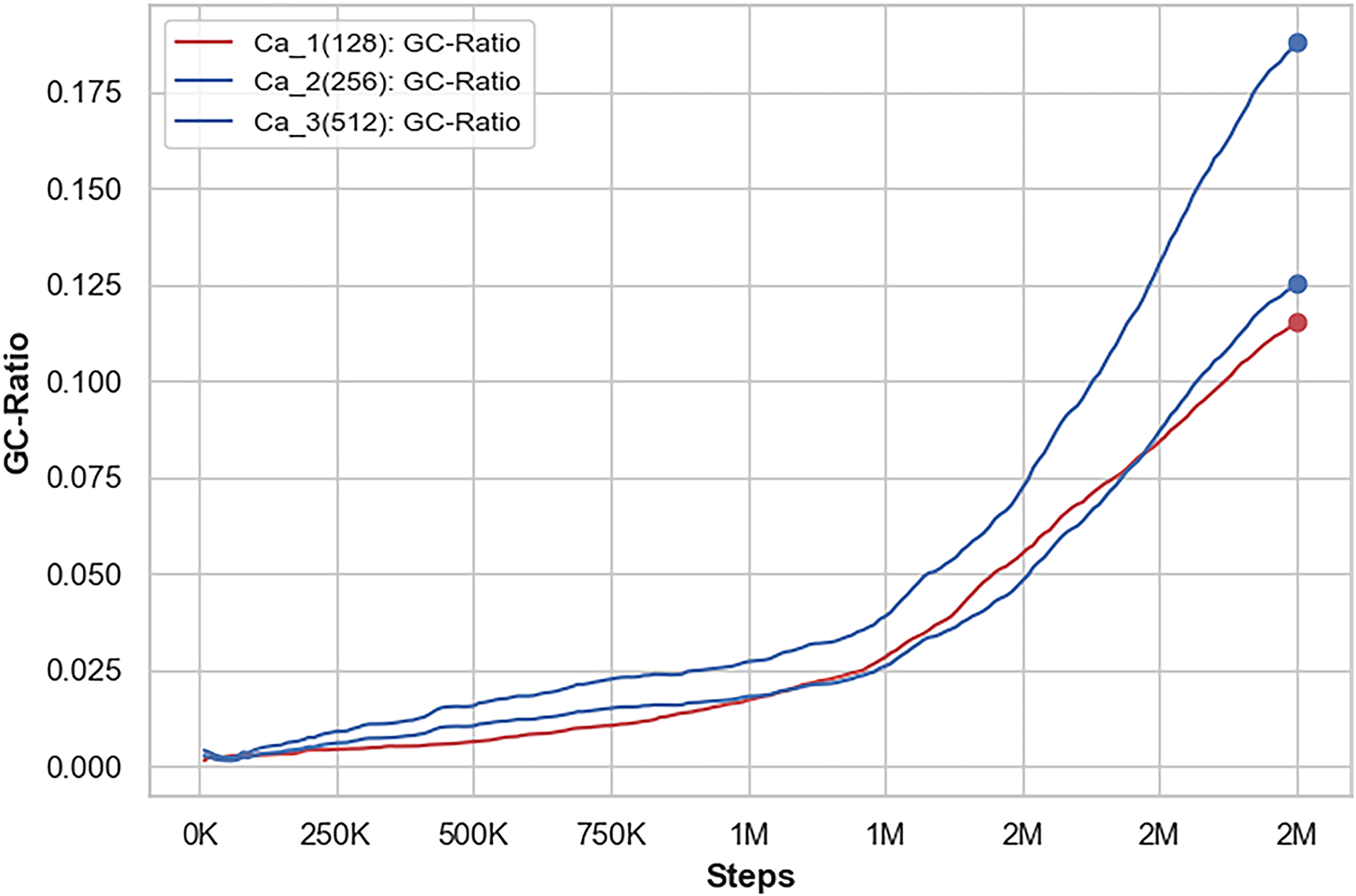

The GC-ratio is an essential metric used to evaluate the performance of an AI agent, as it provides a quantitative measure of the agent’s effectiveness in reaching its goals while minimizing collisions during its operations in a specified environment. This metric reflects the average outcomes of two critical factors: the total number of goals successfully achieved and the number of collisions encountered by the agent. To incentivize the AI agent to continually improve, a reward function is employed. This function encourages the agent to exceed its past performance metrics by rewarding it for achieving targets more quickly or efficiently than in previous attempts. Fig. 7 shows a comparison of the GC-ratio in three cases. Each case uses a different number of hidden units in the agent’s design. Case 3, with 512 hidden units, has the highest GC-ratio. This means the agent in Case 3 reaches the most goals with the fewest collisions. The agent works best with 512 hidden units, better than with 128 or 256 units. This improvement is mainly because the agent can navigate complex environments better.

Figure 7: A comparison between the GC-ratio value for Case 1 (Ca_1) with 128 hidden units, Case 2 (Ca_2) with 256 hidden units, and Case 3 (Ca_3) with 512 hidden units

The increased accuracy in navigation is likely a byproduct of the enhanced capacity afforded by the 512 hidden units. With more hidden units, the agent can capture and learn intricate patterns and relationships within the data, leading to more informed decision-making during exploratory tasks. This ability to discern complex patterns enables the AI agent to react more adeptly to different scenarios it encounters in its environment, thus improving overall performance.

Based on these findings, it is highly advisable to commence the training process for the AI agent using the configuration with 512 hidden units. Implementing this configuration not only suggests a higher potential for achieving superior performance across a variety of tasks but also indicates a substantial increase in reliability during navigation through intricate environments. Consequently, adopting this advanced configuration may result in more effective outcomes, ultimately leading to enhanced operational efficiency and better overall functionality for the AI agent across diverse applications.

Reinforcement learning is crucial in the design and development of AI agents, significantly simplifying the process by minimizing the need for extensive data collection. This study specifically aimed to evaluate the performance of AI agents across three carefully crafted scenarios, each distinguished by the number of hidden units in their neural network architectures. In the first scenario, known as Case 1, the agents operated with 128 hidden units. This configuration served as the foundational baseline for the experimental analysis, providing a clear understanding of the agents’ capabilities. Building upon the foundation of Case 1, the study progressed to explore more complex neural network architectures. In Case 2, the number of hidden units was increased to 256, allowing for a more intricate representation of the environment and potentially enabling the agents to capture more nuanced patterns in the data.

This expansion in network capacity was designed to test whether the additional complexity would translate into improved performance across various reinforcement learning tasks. The investigation culminated in Case 3, where the neural networks were further expanded to incorporate 512 hidden units. This significant increase in network size was intended to push the boundaries of the agents’ learning capabilities, potentially enabling them to handle more complex decision-making processes and adapt to a wider range of environmental challenges. By systematically varying the number of hidden units across these three cases, the study aimed to provide a comprehensive analysis of how neural network architecture impacts the performance of AI agents in reinforcement learning scenarios, offering valuable insights for future AI system designs and optimizations.

In Case 2, the complexity was increased by utilizing 256 hidden units, which were intended to enhance the agents’ ability to process and learn from their environment more effectively. This modification aimed to determine whether a greater number of hidden units could lead to improved performance in decision-making tasks. Finally, Case 3 represented the most sophisticated architecture in this study, featuring 512 hidden units. By employing this advanced configuration, the research sought to explore the upper limits of the agents’ processing potential and ascertain how this increased complexity impacted their overall effectiveness in various scenarios.

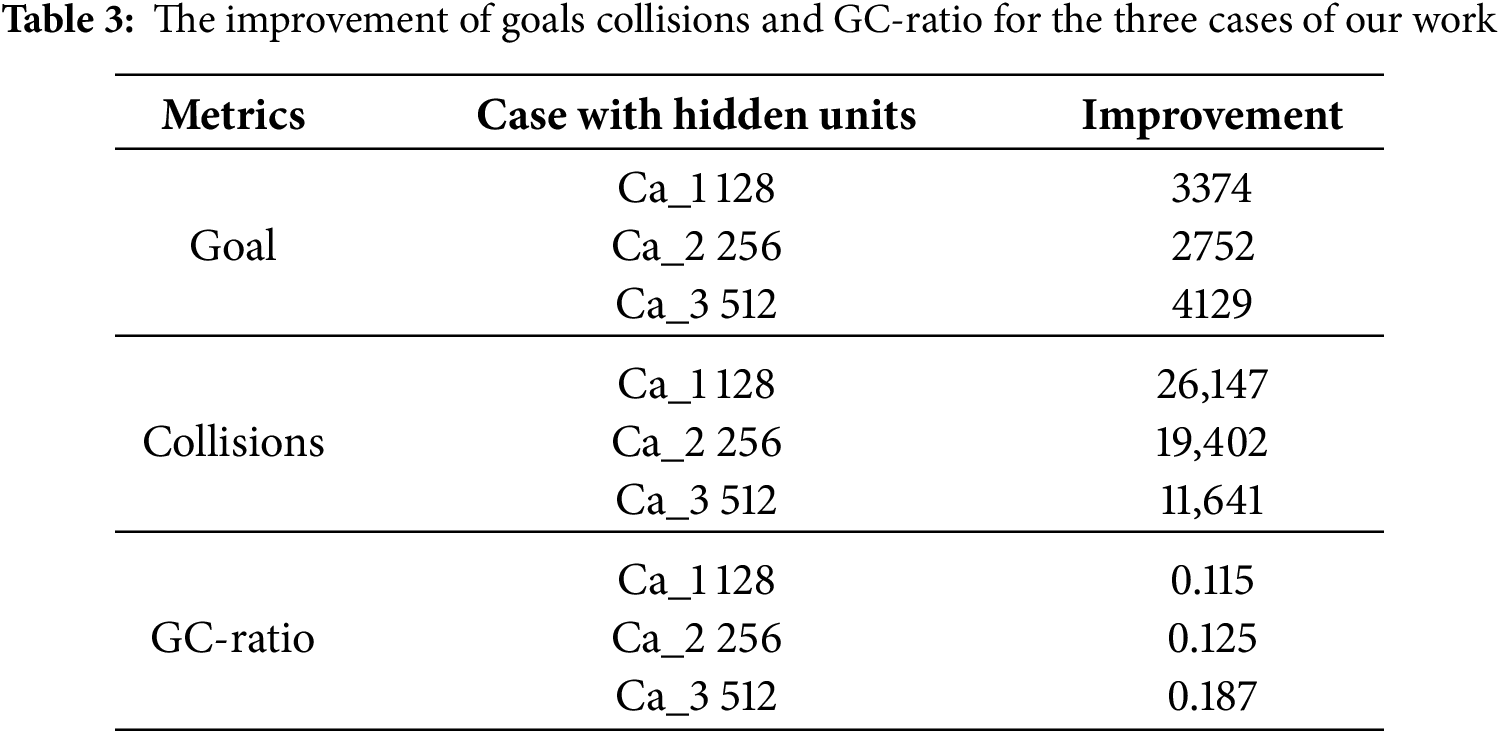

To facilitate the agents’ learning and interaction with their environment, we employed the PPO algorithm. This algorithm is well-regarded in the field of Reinforcement Learning for its ability to balance exploration and exploitation, allowing agents to effectively navigate their surroundings, seek targets, and achieve designated goals. The results from our analysis indicated that all agents were able to navigate their environments and successfully avoid obstacles. However, their performance levels varied markedly between the different configurations. In Case 1, the agent with 128 hidden units demonstrated the highest collision rate with obstacles but managed to achieve a commendable number of goals. This resulted in a Goal-Collision (GC) ratio of 0.115, indicating that while many goals were accomplished, they were often overshadowed by the frequency of collisions. In Case 2, the agents utilizing 256 hidden units exhibited improved performance in terms of collision avoidance. They recorded fewer instances of collisions compared to Case 1; however, their goal attainment was somewhat reduced, leading to a GC ratio of 0.125. The standout performance was observed in Case 3, where the agent featured 512 hidden units. This configuration significantly enhanced its navigation capabilities, resulting in the lowest collision count among all scenarios, paired with the highest level of goal attainment. Consequently, the GC ratio for Case 3 was measured at 0.187, marking a substantial improvement of approximately 50% over Case 2. This comprehensive analysis emphasizes the significant impact that the configuration of hidden units has on optimizing the performance of AI agents.

The research findings offer detailed insights into how specific architectural decisions can directly affect the effectiveness of RL applications, ultimately influencing the agents’ ability to learn and adapt in varying environments. To illustrate these outcomes more effectively, Table 3 provides a detailed overview of the maximum values achieved across several key performance indicators, including the total goals met, the number of collisions encountered, and the corresponding GC (goal Completion) ratios for each of the three distinct cases investigated in this study. This table serves as a valuable reference for understanding the trade-offs and performance variations associated with different hidden unit configurations in AI models.

In our ongoing research, we have developed three distinct AI agents, each designed with a different number of hidden units that allow them to navigate their environments more effectively. The first agent utilizes 128 hidden units, the second agent employs 256 hidden units, and the third agent is equipped with 512 hidden units. To facilitate navigation and decision-making, all agents implement the PPO algorithm, a popular reinforcement learning method known for its efficiency and effectiveness in various tasks. Our research findings indicate that all three configurations are capable of successfully guiding their respective agents toward predetermined goals, demonstrating their viability as autonomous navigators. However, it is crucial to recognize that each configuration comes with its own advantages and limitations. For instance, the agents with 128 and 256 hidden units exhibited nearly identical results in terms of performance metrics. Specifically, the first agent, referred to as Ca_1, was able to achieve a significantly higher number of goals within the same time frame. In contrast, the second agent, Ca_2, exhibited a notable reduction in collision incidents, indicating a more cautious approach to navigation. The most notable improvement emerged from the third agent, which is equipped with an impressive 512 hidden units. This sophisticated configuration led to an extraordinary 50% reduction in collisions when compared to its counterparts. Furthermore, the third agent demonstrated a remarkable 50% increase in the number of successfully achieved goals, underscoring its exceptional performance in terms of both efficiency and safety. The ability to significantly reduce collisions is particularly advantageous for autonomous agents, as it greatly enhances overall safety, especially in the unpredictable and dynamic environments that autonomous vehicles frequently encounter. These environments can include busy urban areas, highways with varying traffic conditions, and unpredictable weather scenarios, all of which present unique challenges for navigation. By minimizing the risk of collisions, autonomous technology not only improves the reliability and effectiveness of navigation systems but also plays a crucial role in ensuring the safety of both the autonomous agents themselves and the people and property in their vicinity. This proactive approach to safety helps build trust in autonomous systems among users and the general public. Moreover, the advancements in collision reduction technologies, such as improved sensors, advanced algorithms for obstacle detection, and refined decision-making processes, highlight significant progress in the field of autonomous technology. These innovations represent a promising step forward in creating a safer and more efficient transportation system, where considerations for safety and operational efficiency take precedence. Overall, this development paves the way for broader acceptance and integration of autonomous vehicles into everyday life.

These advanced AI agents, powered by Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO), present significant challenges for AI governance. Traditional control methodologies prove inadequate due to the systems’ unpredictability, complexity, and autonomous capabilities. Effective governance necessitates stringent regulations applicable at every operational stage, rather than solely at the conclusion. Key areas of control include: Control (implementing mechanisms to reverse actions and deactivate the system), Visibility (maintaining comprehensive records of actions, akin to “Autonomy Passports”), and Security (restricting the agent’s access and utilization capabilities). Future regulatory frameworks should concentrate on three primary domains. Firstly, it is imperative to delineate accountability in instances where AI causes harm, such as security breaches or financial losses, determining whether the responsibility lies with the designer, the company, or the AI itself. Secondly, it is essential to ensure human oversight in critical sectors, such as healthcare facilities or power plants, to authorize high-risk actions. Lastly, attention must be directed towards monitoring significant risks and employment shifts. Regulators should be vigilant of simultaneous failures across multiple agents and facilitate workforce skill development in response to increasing automation.

Acknowledgement: The authors acknowledge the contribution and the support of the Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering and Computer Science at Jackson State University (JSU).

Funding Statement: This work was partly supported by the United States Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) contract FA9550-22-1-0268 awarded to KHA, https://www.afrl.af.mil/AFOSR/. The contract is entitled: “Investigating Improving Safety of Autonomous Exploring Intelligent Agents with Human-in-the-Loop Reinforcement Learning,” and in part by Jackson State University.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Khalid H. Abed, Miah A. Robinson, Abdulghani M. Abdulghani, Mokhles M. Abdulghani; data collection: Miah A. Robinson, Abdulghani M. Abdulghani; analysis and interpretation of results: Abdulghani M. Abdulghani; draft manuscript preparation: Miah A. Robinson, Abdulghani M. Abdulghani, Mokhles M. Abdulghani, Khalid H. Abed. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The code used and/or analyzed during this research are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Mazouchi M, Nageshrao S, Modares H. Conflict-aware safe reinforcement learning: a meta-cognitive learning framework. IEEE/CAA J Autom Sin. 2022;9(3):466–81. doi:10.1109/jas.2021.1004353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yamagata T, Santos-Rodriguez R. Safe and robust reinforcement learning: principles and practice. arXiv:2403.18539. 2024. [Google Scholar]

3. Almón-Manzano L, Pastor-Vargas R, Troncoso JMC. Deep reinforcement learning in agents’ training: unity ML-agents. In: Bio-inspired systems and applications: from robotics to ambient intelligence. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2022. p. 391–400. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-06527-9_39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mataric MJ. Reward functions for accelerated learning. In: Machine Learning Proceedings 1994. Amsterdam, The Netherland: Elsevier; 1994. p. 181–9. doi:10.1016/b978-1-55860-335-6.50030-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Brockman G, Cheung V, Pettersson L, Schneider J, Schulman J, Tang J, et al. OpenAI gym. arXiv:1606.01540. 2016. [Google Scholar]

6. Bellemare MG, Naddaf Y, Veness J, Bowling M. The arcade learning environment: an evaluation platform for general agents. J Artif Intell Res. 2013;47:253–79. doi:10.1613/jair.3912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Amodei D, Olah C, Steinhardt J, Christiano P, Schulman J, Mané D. Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv:1606.06565. 2016. [Google Scholar]

8. Juliani A, Berges V-P, Teng E, Cohen A, Harper J, Elion C, et al. Unity: a general platform for intelligent agents. arXiv:1809.02627. 2018. [Google Scholar]

9. Schulman J, Wolski F, Dhariwal P, Radford A, Klimov O. Proximal policy optimization algorithms. arXiv:1707.06347. 2017. [Google Scholar]

10. Cuccu G, Togelius J, Cudré-Mauroux P. Playing Atari with few neurons. Auton Agents Multi-Agent Syst. 2021;35(2):17. doi:10.1007/s10458-021-09497-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Silver D, Schrittwieser J, Simonyan K, Antonoglou I, Huang A, Guez A, et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature. 2017;550(7676):354–9. doi:10.1038/nature24270. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Vinyals O, Ewalds T, Bartunov S, Georgiev P, Vezhnevets AS, Yeo M, et al. StarCraft II: a new challenge for reinforcement learning. arXiv:1708.04782. 2017. [Google Scholar]

13. Kiumarsi B, Modares H, Lewis F. Reinforcement learning for distributed control and multi-player games. In: Handbook of reinforcement learning and control. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2021. p. 7–27. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-60990-0_2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Yu D, Zou W, Yang Y, Ma H, Li SE, Yin Y, et al. Safe model-based reinforcement learning with an uncertainty-aware reachability certificate. IEEE Trans Automat Sci Eng. 2024;21(3):4129–42. doi:10.1109/tase.2023.3292388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Berkenkamp F, Turchetta M, Schoellig AP, Krause A. Safe model-based reinforcement learning with stability guarantees. arXiv:1705.08551. 2017. [Google Scholar]

16. Chow Y, Ghavamzadeh M, Janson L, Pavone M. Risk-constrained reinforcement learning with percentile risk criteria. arXiv:1512.01629. 2015. [Google Scholar]

17. Alizadeh Alamdari P, Klassen TQ, Toro Icarte R, McIlraith SA. Be considerate: Avoiding negative side effects in reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the 21st International Conference on Autonomous Agents and Multiagent Systems; 2022 May 9–13; Virtual Event. [Google Scholar]

18. Rosser C, Abed K. Curiosity-driven reinforced learning of undesired actions in autonomous intelligent agents. In: Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 19th World Symposium on Applied Machine Intelligence and Informatics (SAMI); 2021 Jan 21–23; Herl’any, Slovakia. p. 39–42. [Google Scholar]

19. Abdulghani AM, Abdulghani MM, Walters WL, Abed KH. AI safety approach for minimizing collisions in autonomous navigation. J Artif Intell. 2023;5:1–14. doi:10.32604/jai.2023.039786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Abdulghani MM, Abdulghani AM, Walters WL, Abed KH. Obstacles avoidance using reinforcement learning for safe autonomous navigation. In: Proceedings of the 2023 Congress in Computer Science, Computer Engineering & Applied Computing (CSCE); 2023 Jul 24–27; Las Vegas, NV, USA. p. 341–5. doi:10.1109/CSCE60160.2023.00059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Baker B, Kanitscheider I, Markov T, Wu Y, Powell G, McGrew B, et al. Emergent tool use from multi-agent autocurricula. arXiv:1909.07528. 2019. [Google Scholar]

22. Reizinger P, Szemenyei M. Attention-based curiosity-driven exploration in deep reinforcement learning. In: Proceedings of the ICASSP 2020—2020 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP); 2020 May 4–8; Barcelona, Spain. p. 3542–6. doi:10.1109/icassp40776.2020.9054546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Goecks VG, Gremillion GM, Lawhern VJ, Valasek J, Waytowich NR. Efficiently combining human demonstrations and interventions for safe training of autonomous systems in real-time. Proc AAAI Conf Artif Intell. 2019;33(1):2462–70. doi:10.1609/aaai.v33i01.33012462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Schulman J, Moritz P, Levine S, Jordan M, Abbeel P. High-dimensional continuous control using generalized advantage estimation. arXiv:1506.02438. 2015. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools