Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

DWaste: Greener AI for Waste Sorting Using Mobile and Edge Devices

DWaste, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA

* Corresponding Author: Suman Kunwar. Email:

Journal on Artificial Intelligence 2026, 8, 39-49. https://doi.org/10.32604/jai.2026.076674

Received 24 November 2025; Accepted 30 December 2025; Issue published 22 January 2026

Abstract

The rise in convenience packaging has led to generation of enormous waste, making efficient waste sorting crucial for sustainable waste management. To address this, we developed DWaste, a computer vision-powered platform designed for real-time waste sorting on resource-constrained smartphones and edge devices, including offline functionality. We benchmarked various image classification models (EfficientNetV2S/M, ResNet50/101, MobileNet) and object detection (YOLOv8n, YOLOv11n) including our purposed YOLOv8n-CBAM model using our annotated dataset designed for recycling. We found a clear trade-off between accuracy and resource consumption: the best classifier, EfficientNetV2S, achieved high accuracy (Keywords

The growth of convenience packaging has increased waste generation [1], underscoring the need for efficient sorting. Global waste is projected to grow from 2.1 to 3.8 billion tons by 2050 [2], an increase that compounds the financial, environmental and planetary burdens. For instance, a study on Chilean municipal solid waste (MSW) found the cost of the unsorted waste to be € 297.66 per ton [3]. Furthermore, waste contamination poses a significant challenge to implementing a circular economy, particularly given that the US has seen its recycling rate stagnate at around 35% for over a decade [4].

To address this challenge, traditional waste management has begun to incorporate technology. During the past decades, various machine learning (ML) models, such as linear regression (LR), support vector machine (SVM), and random forest (RF), have evolved to predict the inbound contamination rates [5]. Simultaneously, IoT devices integrated with bins, vehicles, and recycling facilities are helping to sort waste and collect data, utilizing GPS for route tracking and temperature sensors for fire protection. The field is now undergoing a pivotal shift with the move from traditional ML to Deep Learning (DL) for perception tasks, alongside the adoption of the Edge Artificial Intelligence (Edge AI) paradigm. The shift to Edge AI addresses critical needs for low latency, private, and reliable on-device processing [6]. This requires a systems approach spanning efficient model architectures, inference engines, and hardware-aware optimization. Deploying models on resource-constrained IoT and mobile devices presents significant challenges, including strict limits on computational power, memory, and energy consumption [7]. These constraints are amplified by the need for sustainable and carbon-aware AI, which demands minimizing the computational and energy footprint of ML systems throughout their lifecycle [8]. This dual focus on edge efficiency and environmental impact forms the core motivation for our work. To meet this challenge, various specialized lightweight model architectures have been developed based on principles such as depthwise separable convolutions (MobileNets [9]), pointwise group convolution and channel shuffling (ShuffleNet [10]), and feature redundancy reduction (GhostNet [11]). These models dramatically reduce parameter and computation (FLOPs) with minimal accuracy loss, making them critical enablers for edge deployment.

The economic viability of these systems is a crucial factor, as research by Liu et al. demonstrated that computer vision-enabled systems (CVAS) become cost-effective when labor costs are high, while conventional sorting (CS) is preferable when machinery or maintenance costs are higher; their comprehensive cost model included labor, training, machinery, maintenance, and net present values of investments [12]. Special DL architectures, particularly object detection models, have shown promising results in sorting applications. For example, YOLOv5 models equipped with a webcam and robotic arms have demonstrated waste sorting capabilities with a precision of 93.3% [13]. More recently, a YOLOv8 model embedded in a Raspberry Pi achieved 98% accuracy in complex tasks within real-time intelligent garbage monitoring and collection systems [14] that showcase practical, low-cost solutions for smart waste management in urban environments.

In the realm of classification, high accuracy has been achieved with CNN architectures. Ahmad et al. utilized a ResNet-based CNN to automatically classify 12 waste types, achieving 98.16% [15]. Tran et al. achieved an accuracy of 96% using ResNet-50 for organic and inorganic waste classification with a Raspberry Pi 4 for direct sorting [16]. Additionally, a comparative study by Soni et al. found that MobileNet, despite achieving an accuracy of 80%, offered superior accuracy relative to its size and lower computation cost, making it highly suitable for scalable real-world applications [17].

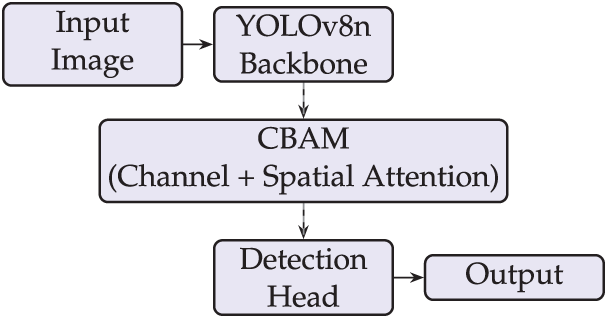

System efficiency, particularly for mobile and edge computing, remains a key consideration, with YOLOv11n proved to be the most power-efficient (125,000 μAh in 590 s), while YOLOv11m/11s performed best in accuracy-driven applications [18]. Despite these advances, challenges persist, as highlighted in a review by Gelar et al. on YOLO and IoT applications, which identified issues with accurate detection, environmental adaptability, and optimizing low-power IoT performance [19]. The Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) integrated with YOLO architectures to improve feature extraction and spatial attention has shown promising results [20]. For real-time waste detection requiring simultaneous localization and classification, single-stage object detectors such as YOLO are more suitable than CNNs based only on classification. Their nano variants are specifically engineered for edge devices, optimizing the critical accuracy-efficiency-speed trade-off [21]. CBAM’s channel and spatial attention mechanisms [22] direct computational focus to the most discriminative features and crucial spatial regions, which is essential for detecting partially obscured waste and thereby improving overall precision and recall. Unlike generic multi-stage CBAM-YOLO integrations, our approach injects a single lightweight CBAM module solely at YOLOv8n’s deepest backbone layer, enabling targeted attention with minimal edge-computational overhead.

Although our own previous study focused on benchmarking models based on accuracy and carbon emission to determine a “greener” classification model, it was limited to classification tasks only [23]. This paper aims to address these challenges by systematically evaluating the trade-off in deploying advanced DL models. To bridge the gap between detection accuracy and sustainable edge deployment, we propose a computationally optimized YOLOv8n variant enhanced with CBAM attention modules. We then benchmark this model against state-of-the-art alternatives, using model quantization as the primary optimization technique to precisely measure reductions in VRAM usage, model size, and carbon emissions, validating a path toward a “Greener AI” solution for waste sorting. Subsequently, the greener model was deployed to mobile and edge devices.

The section discusses the dataset used in this study, the methods for benchmarking and training the models, and the carbon emission measurement.

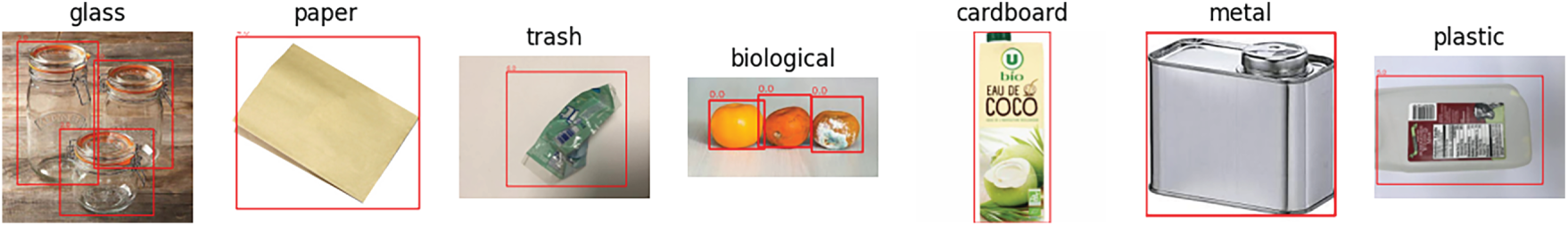

In this study, we used our garbage dataset [24] focusing on seven categories deemed critical for recycling efficiency: biological, cardboard, glass, metal, paper, plastic, and trash. These images were collected from the internet, DWaste platform, and community submissions. All images were annotated with category labels and bounding boxes using Annotate Lab [25]. The final processed dataset consists of 11,163 images and 19,700 bounding box instances shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Dataset class distribution

The above images show a non-uniform distribution characteristic of real world municipal solid waste streams. For classification models, class imbalance was addressed using the undersampling technique, where images were selectively removed from oversampled classes [26]. Conversely, for object detection models, the imbalance was addressed by applying computed class weights during training phase [27], which up-weighted the loss contribution of underrepresented classes. The finalized dataset was then partitioned using an 80/20 split for the training and validation sets. The sample annotated waste image of the above classes is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Sample annotated images from our dataset

We evaluated both classification (EfficientNetV2S/M, MobileNet, ResNet50/101) and object detection (YOLOv8n, YOLOv11n) architectures, including our proposed YOLOv8n-CBAM model shown in Fig. 3, using a transfer learning approach.

Figure 3: Architecture of the proposed Improved YOLOv8n model with CBAM-enhanced backbone

All classification models were initialized with weight pre-trained on the ImageNet dataset. All models were trained for 20 epochs using NVIDIA Tesla T4x2 GPU in Kaggle. The performance of each model was benchmarked using standard performance metrics including Accuracy, Precision, Recall, F1-score, and Mean Average Precision (mAP). With our focus on sustainable AI deployment, we conducted a detailed analysis of VRAM usage, model size, and carbon emissions at various phases of the workflow. The resulting full-precision models were further optimized via quantization, a technique known to achieve a reduction of up to 95% in the number of parameters and model size [28], thus significantly lowering energy use.

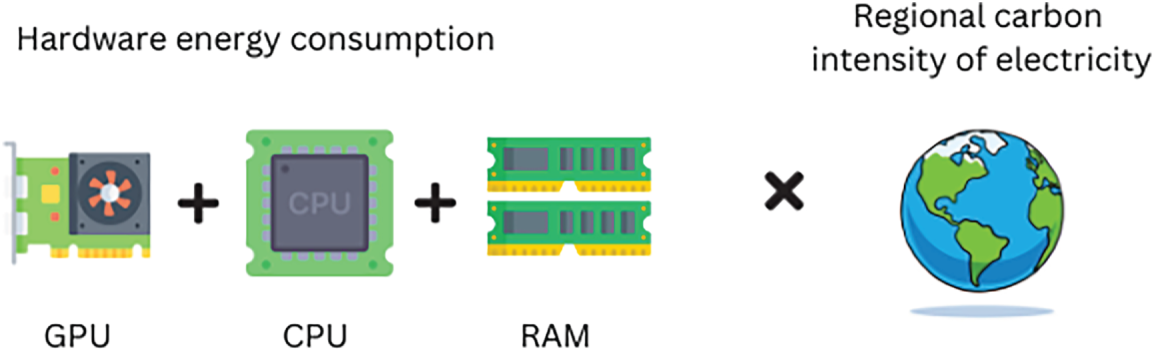

2.3 Carbon Emission Measurement

Carbon emissions were measured using the CodeCarbon (v3.0.4) library [29]. Emissions were benchmarked on a fixed Kaggle instance with a Tesla T4x2 GPU, an Intel Xeon CPU (4 threads), and 32 GB RAM. The emission formula of codecarbon is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Codecarbon carbon emission formula

Measurements covered three phases per model: data preparation, model development (full 20-epoch training), and single-image inference (one forward pass). Due to platform constraints, CPU power was estimated via a constant Thermal Design Power (TDP) model, while GPU power was measured directly via pynvml. All runs used dedicated instances and default Iowa region grid (USA), carbon intensity for consistent comparative analysis.

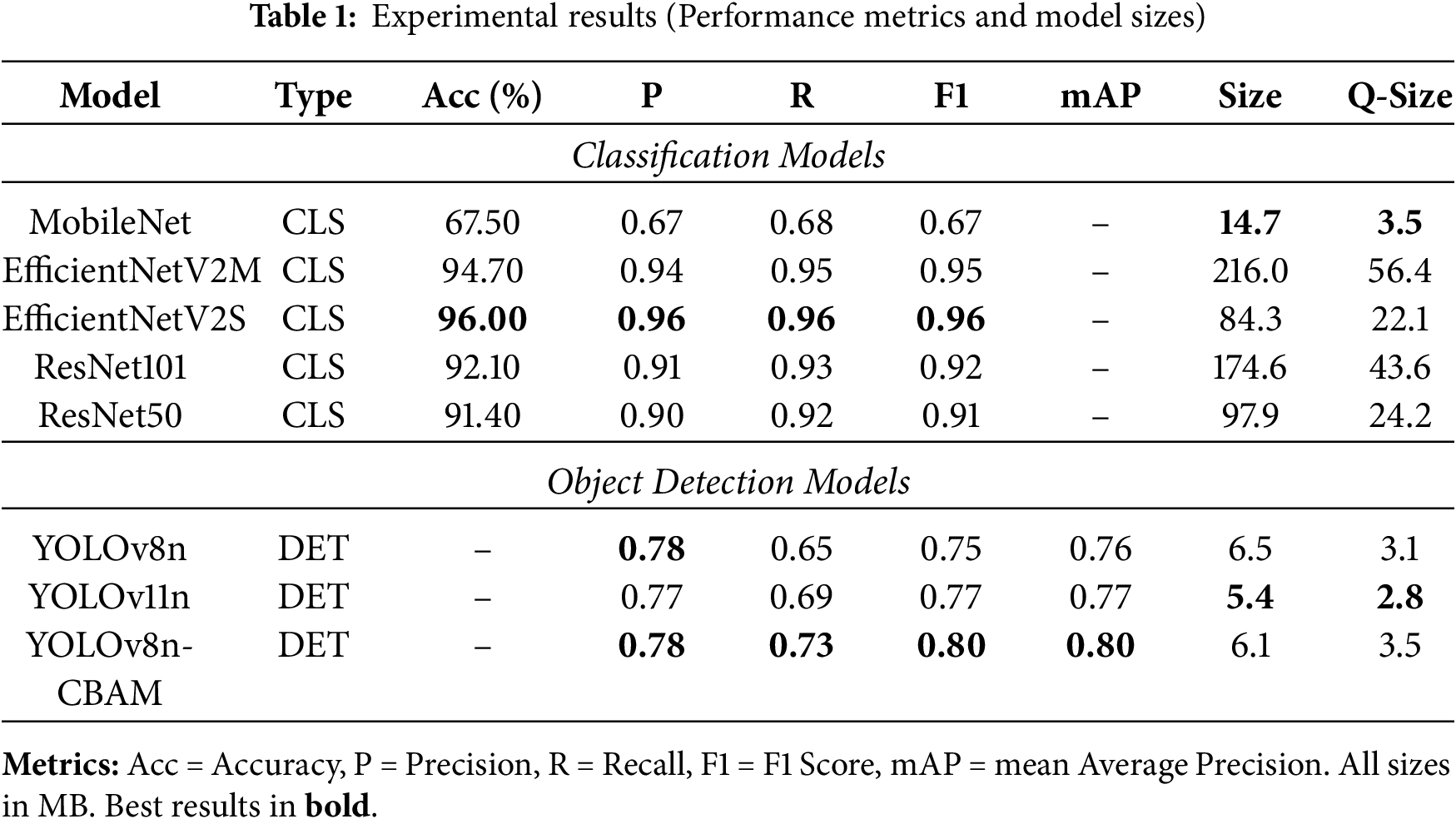

Our experiment revealed a distinct tradeoff between model accuracy, size, and carbon efficiency as shown in Table 1.

The high-performance classification models EfficientNetV2M and EfficientNetV2S showed the highest accuracy (

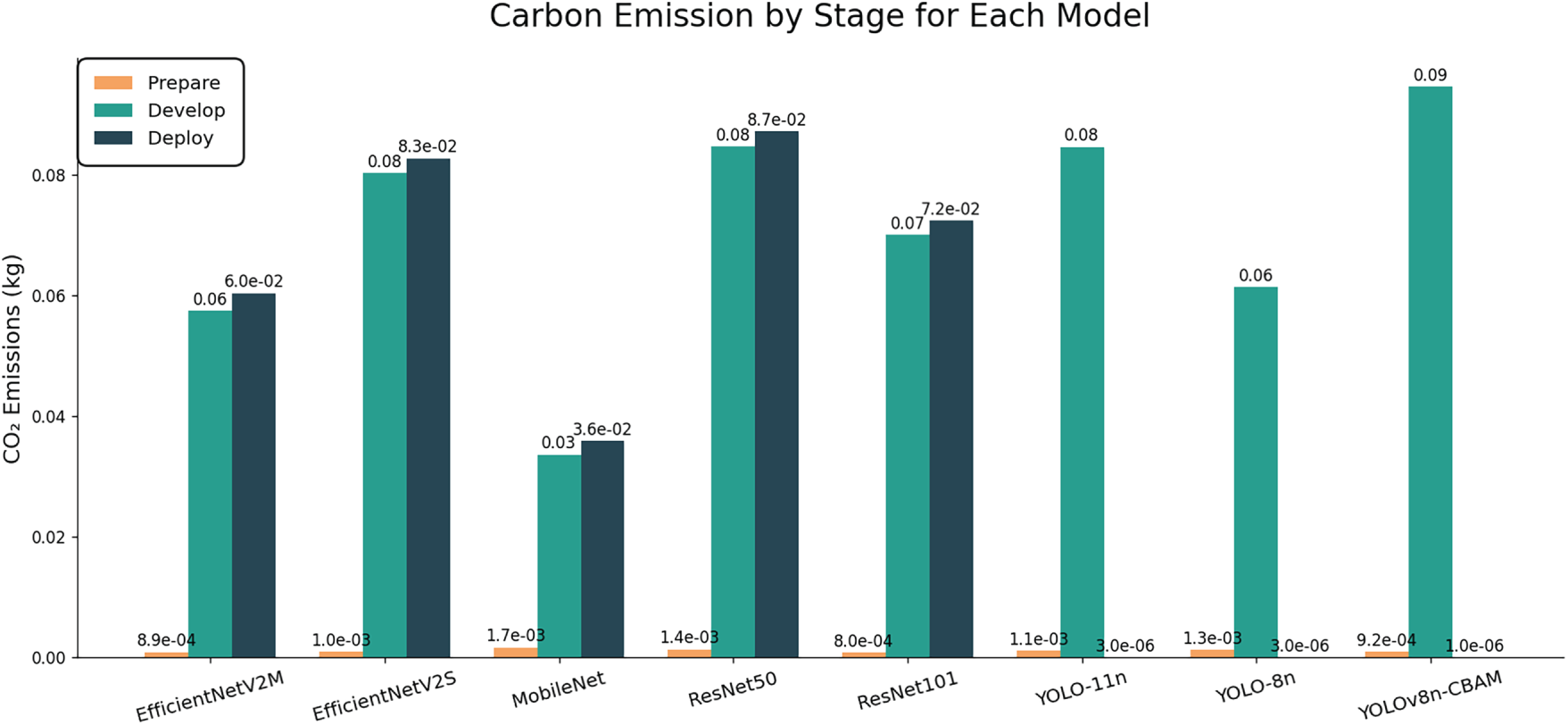

Figure 5: Carbon emission by stage for each model

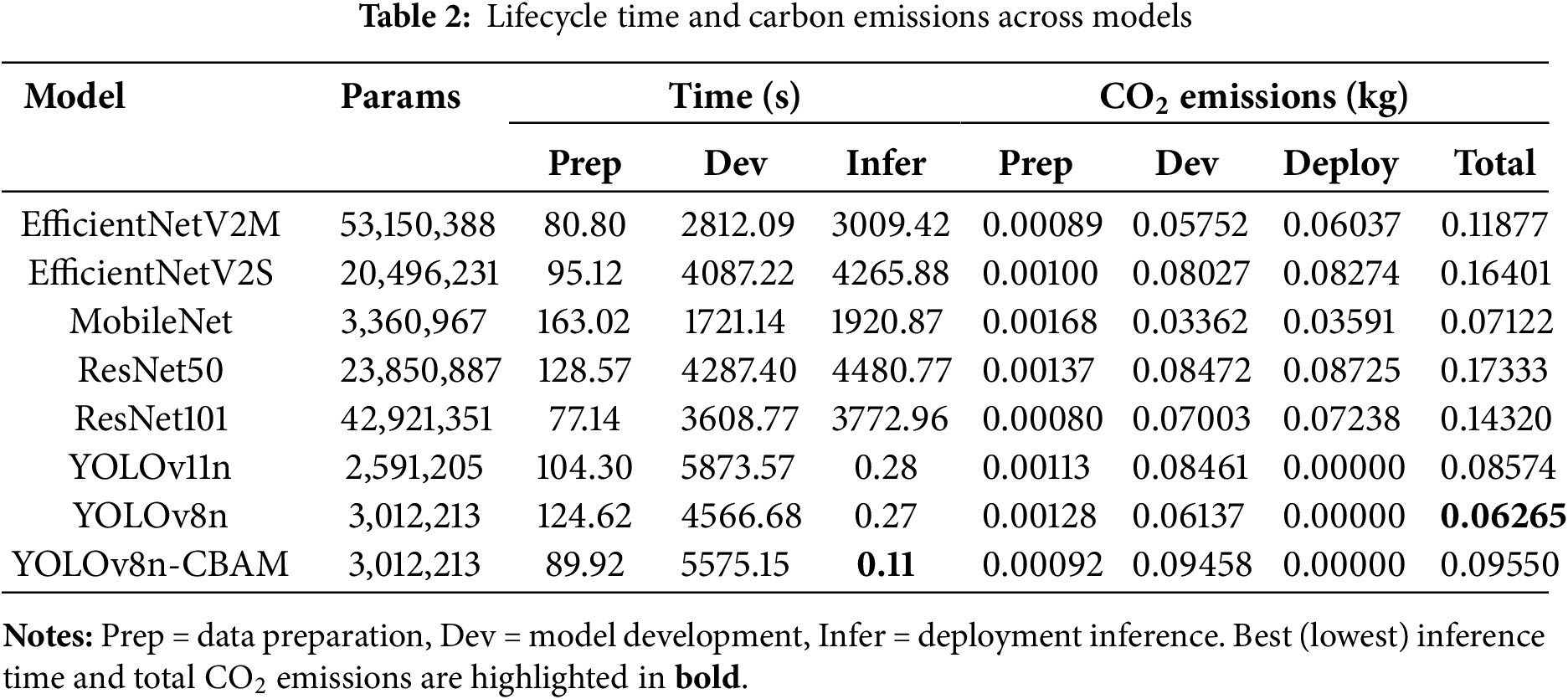

An integrated analysis of parameters, runtime and their carbon emissions, shown in Table 2, reveals that ResNet50 incurred the highest total emissions total (0.173

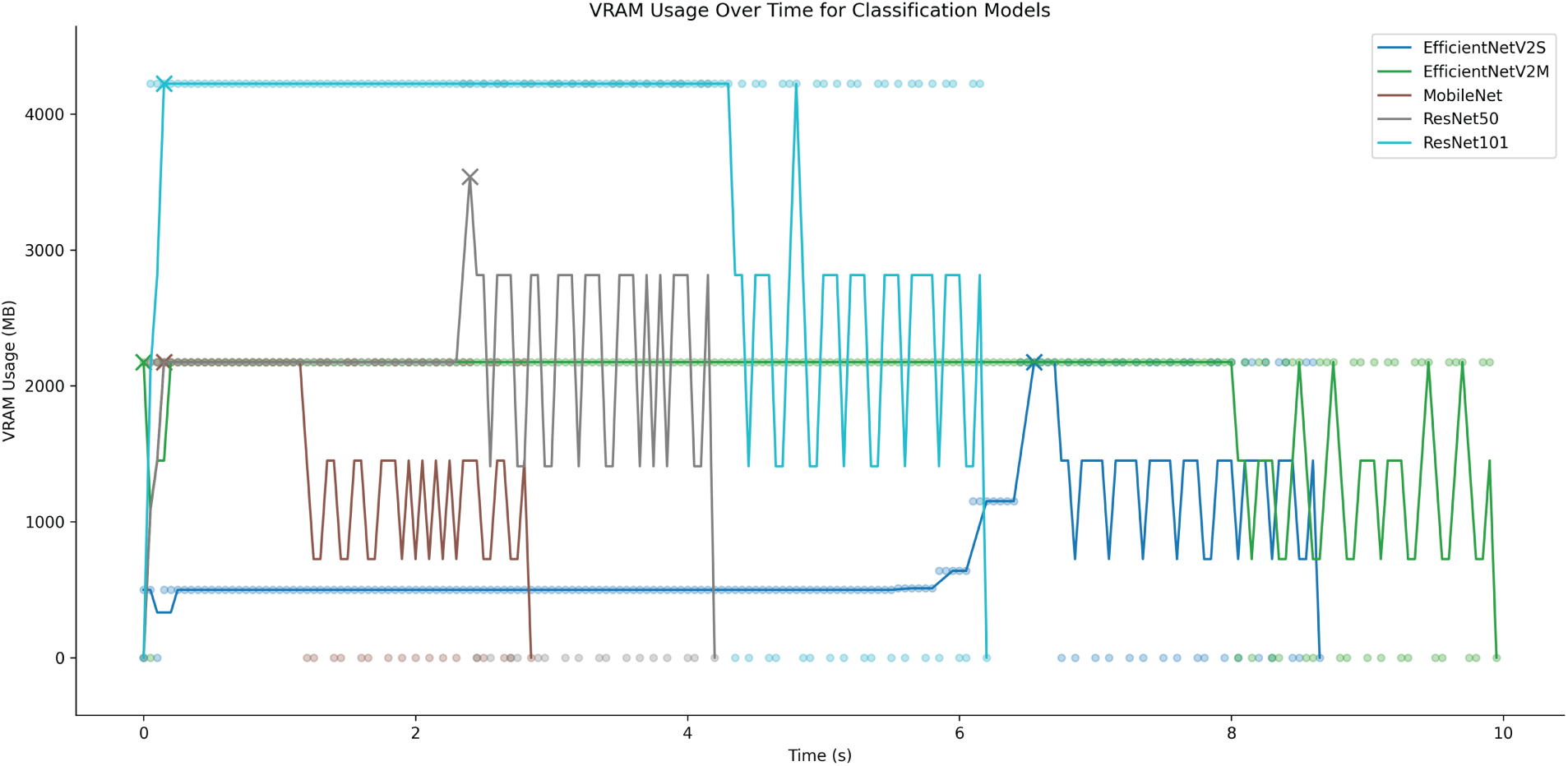

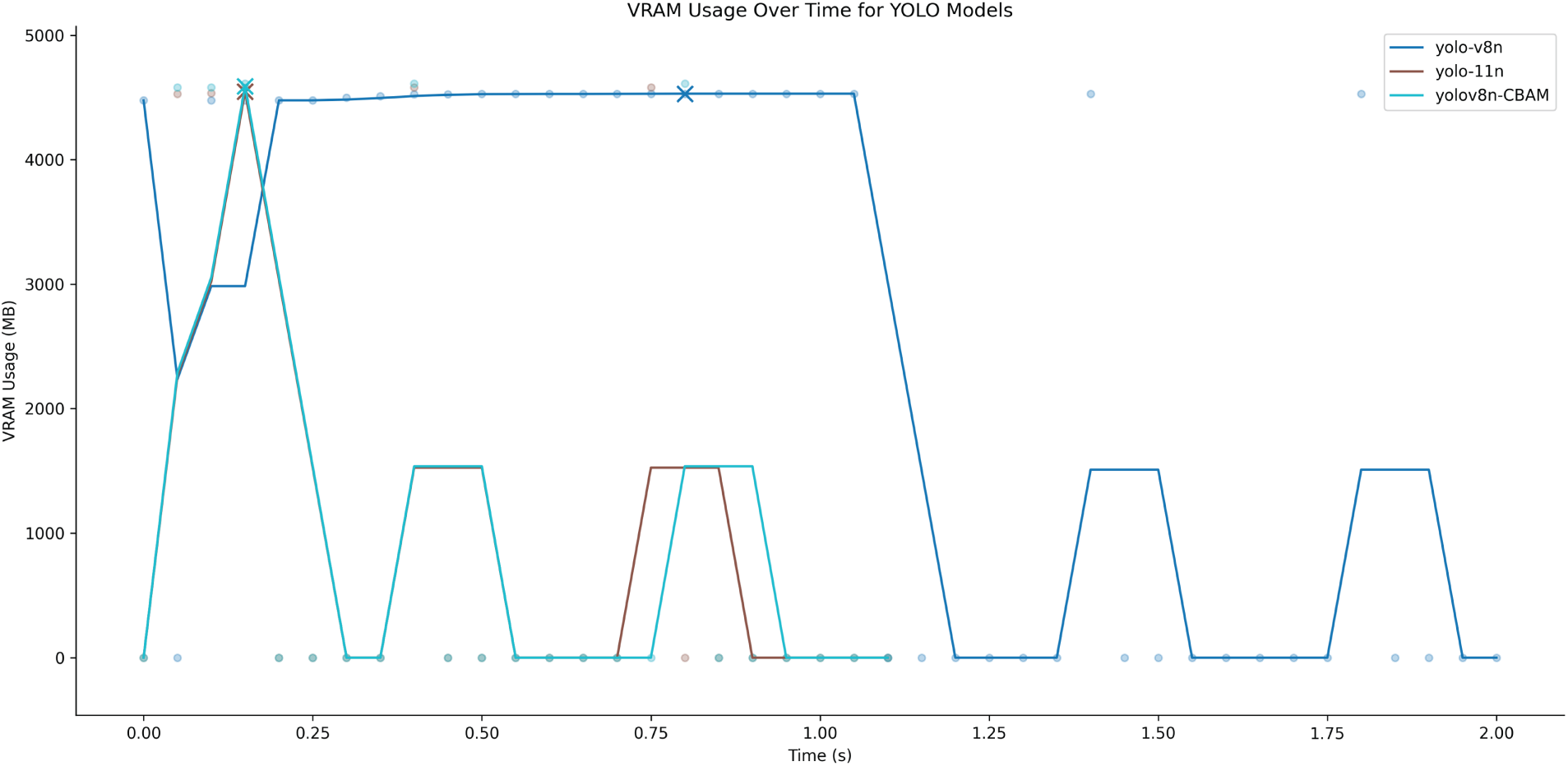

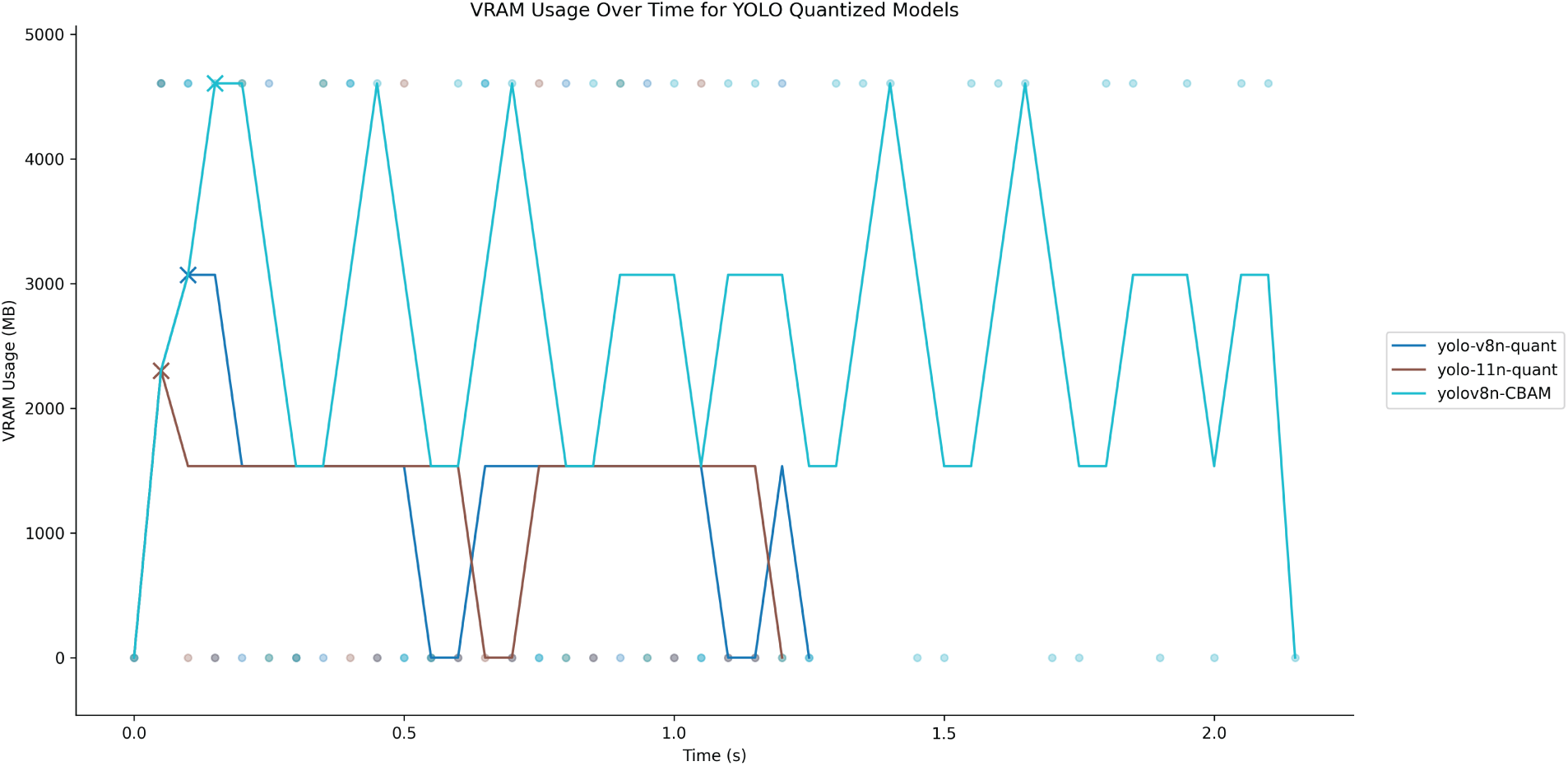

While all classification models, including MobileNet, exhibited low VRAM usage during inference time, as shown in Figs. 6 and 7. In contrast, YOLO models initially consumed slightly more VRAM as shown in Fig. 8, but achieved a faster inference time, which improved significantly after quantization.

Figure 6: Classification models VRAM usage under inference

Figure 7: Object detection models VRAM usage under inference

Figure 8: Object detection models VRAM usage after quantization under inference

Notably, YOLOv11n emerged as the optimal architecture for edge deployment, attaining the best mean Average Precision (mAP = 0.77) with the smallest quantized footprint (2.8 MB) and the fastest speed, confirming its efficacy for resource-constrained applications with minimal carbon emissions. Our proposed model performed best in terms of precision, recall, F1-score, and mAP before quantization, and also had low VRAM usage compared to YOLOv8n and YOLOv11n. However, its VRAM usage increased significantly after quantization.

The VRAM analysis reveals a system-level trade-off. YOLOv8n-CBAM’s higher quantized VRAM (4604 MB) stems from quantization overhead in its attention-augmented graph [31], while YOLOv11n’s minimal usage reflects native edge optimization. This architectural difference explains their performance divergence, CBAM enhances precision through focused attention, whereas YOLOv11n achieves higher mAP via balanced, efficient design. Crucially, YOLOv8n-CBAM’s 25% larger size (3.5 vs. 2.8 MB) increases lifecycle carbon costs through update and storage energy at scale [32]. Thus, model selection balances precision needs against sustainability goals for edge deployment.

The YOLOv8n-CBAM model was deployed to both the DWaste mobile application and a dedicated edge device for a real time waste object. An example of waste detection using both app and the edge device is shown in Fig. 9.

Figure 9: Real-world detection on edge and mobile device: (a) Edge device detecting waste near bins; (b) Mobile app detecting waste

The study has several limitations. The dataset collected from DWaste and online sources lacks lighting, environmental, and camera diversity. Unseen performance waste categories and challenging conditions (soiled, occluded items) remain unvalidated. Carbon measurements are operational only (Scope 2), exclude embodied hardware emissions, and use estimated CPU power. Single-inference measurements do not capture long-term deployment dynamics. Future work will expand the diversity of the dataset and include longitudinal edge-device measurements with comprehensive carbon accounting.

This study successfully quantified the inherent trade-off between model accuracy and energy efficiency for deep learning-based waste sorting systems. Our results clearly demonstrate that while larger architectures (EfficientNetV2S/M, ResNet101/50) achieve superior classification accuracy, they demand greater computational resources and incur significantly higher carbon emissions. Conversely, lightweight object detection models, specifically YOLOv11n and YOLOv8n-CBAM, strike a crucial balance, offering strong real-time performance (mAP 77% and 78%) with minimal resource overhead. Furthermore, we confirmed that the application of model quantization dramatically aids deployment, consistently and substantially reducing VRAM usage and model size, thus directly lowering the energy required for inference on edge and mobile devices. Given these findings, the YOLOv8n-CBAM model, which achieved the best combination of accuracy, inference speed, and minimal resource usage, was selected and successfully embedded into the DWaste mobile app and a dedicated edge device for practical waste sorting implementation. Future work must begin by expanding the dataset to refine model accuracy and initiating a longitudinal study to assess the long-term effectiveness of the current edge system. Beyond this, the core challenges remain, including developing adaptive AI for unseen and occluded waste, integrating full lifecycle carbon accounting (including hardware emissions), and establishing robust continuous learning systems for scalable real-world deployment.

Acknowledgement: The author wishes to express gratitude to the contributors who provided the waste image dataset essential for this research.

Funding Statement: The author received no specific funding for this study.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this study is publicly available and can be accessed at: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/sumn2u/dwaste-data-v4-annotated. The source code and details of the experiments are available at: https://github.com/sumn2u/AIMS-2025.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Pinos J, Hahladakis JN, Chen H. Why is the generation of packaging waste from express deliveries a major problem? Sci Total Environ. 2022;830(2):154759. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.154759. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. UNEP, editor. Beyond an age of waste: turning rubbish into a resource—global waste management outlook 2024 for youth. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP; 2024. [Google Scholar]

3. Sala-Garrido R, Mocholi-Arce M, Molinos-Senante M, Maziotis A. Monetary valuation of unsorted waste: a shadow price approach. J Environ Manage. 2023;325(3):116668. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.116668. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Turner K, Kim Y. Problems of the US recycling programs: what experienced recycling program managers tell. Sustainability. 2024;16(9):3539. doi:10.3390/su16093539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Runsewe T, Damgacioglu H, Perez L, Celik N. Machine learning models for estimating contamination across different curbside collection strategies. J Environ Manage. 2023;340(11):117855. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2023.117855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Singh R, Gill SS. Edge AI: a survey. Internet Things Cyber-Phys Syst. 2023;3(5):71–92. doi:10.1016/j.iotcps.2023.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Surianarayanan C, Lawrence JJ, Chelliah PR, Prakash E, Hewage C. A survey on optimization techniques for edge artificial intelligence (AI). Sensors. 2023;23(3):1279. doi:10.3390/s23031279. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Bolón-Canedo V, Morán-Fernández L, Cancela B, Alonso-Betanzos A. A review of green artificial intelligence: towards a more sustainable future. Neurocomputing. 2024;599(12):128096. doi:10.1016/j.neucom.2024.128096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Howard AG, Zhu M, Chen B, Kalenichenko D, Wang W, Weyand T, et al. MobileNets: efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv:1704.04861. 2017. doi:10.48550/arXiv.1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Zhang X, Zhou X, Lin M, Sun J. ShuffleNet: an extremely efficient convolutional neural network for mobile devices. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 6848–56. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Howard A, Sandler M, Chu G, Chen LC, Chen B, Tan M, et al. Searching for MobileNetV3. In: 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2020 Jun 14–19; Seattle, WA, USA. p. 1314–24. doi:10.1109/CVPR42600.2020.00165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Liu X, Farshadfar Z, Khajavi SH. Computer vision-enabled construction waste sorting: a sensitivity analysis. Appl Sci. 2025;15(19):10550. doi:10.3390/app151910550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Lahoti J, Sn J, Krishna MV, Prasad M, Bs R, Mysore N, et al. Multi-class waste segregation using computer vision and robotic arm. PeerJ Comput Sci. 2024;10(4):e1957. doi:10.7717/peerj-cs.1957. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Abo-Zahhad MM, Abo-Zahhad M. Real time intelligent garbage monitoring and efficient collection using Yolov8 and Yolov5 deep learning models for environmental sustainability. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):16024. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-99885-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ahmad G, Aleem FM, Alyas T, Abbas Q, Nawaz W, Ghazal TM, et al. Intelligent waste sorting for urban sustainability using deep learning. Sci Rep. 2025;15(1):27078. doi:10.1038/s41598-025-08461-w. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Khai Tran T, Tu Huynh K, Le D-N, Arif M, Minh Dinh H. A deep trash classification model on Raspberry Pi 4. Intell Autom Soft Comput. 2023;35(2):2479–91. doi:10.32604/iasc.2023.029078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Soni T, Gupta D, Uppal M. MobileNet-based garbage classification: enhancing recycling with machine learning. In: 2024 International Conference on Intelligent Computing and Emerging Communication Technologies (ICEC). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 1–4. doi:10.1109/ICEC59683.2024.10837152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Eva Urankar. Waste detection on mobile devices: model performance and efficiency comparison. Int J Sci Res Arch. 2025;15(1):722–31. doi:10.30574/ijsra.2025.15.1.1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Gelar T, Fitriani S, Rachmat S. A systematic literature review of YOLO and IoT applications in smart waste management. Green Intell Syst Appl. 2025;5(2):123–39. doi:10.53623/gisa.v5i2.706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Xu P, Luo X, Li J. Improved YOLOv8 underwater object detection combined with CBAM. In: 2024 International Symposium on Digital Home (ISDH). Piscataway, NJ, USA: IEEE; 2024. p. 43–8. doi:10.1109/ISDH64927.2024.00014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Terven J, Córdova-Esparza DM, Romero-González JA. A comprehensive review of YOLO architectures in computer vision: from YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Mach Learn Knowl Extraction. 2023;5(4):1680–716. doi:10.3390/make5040083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Woo S, Park J, Lee JY, Kweon IS. CBAM: convolutional block attention module. In: Ferrari V, Hebert M, Sminchisescu C, Weiss Y, editors. Computer vision—ECCV 2018. Lecture notes in computer science. Vol. 11211. Cham, Switzerland: Springer; 2018. p. 3–19. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-01234-2_1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Kunwar S. Managing household waste through transfer learning. Ind Domestic Waste Manag. 2024;4(1):14–22. doi:10.53623/idwm.v4i1.408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Kunwar S. dwaste-data-v4-annotated [Internet]. 2025 [cited 2025 Oct 22]. Available from: https://www.kaggle.com/ds/7619147. [Google Scholar]

25. Kunwar S. Annotate-Lab: simplifying image annotation. J Open Source Softw. 2024;9(103):7210. doi:10.21105/joss.07210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. He H, Ma Y, editors. Imbalanced learning: foundations, algorithms, and applications. 1st ed. Hoboken, NJ, USA: Wiley; 2013. doi:10.1002/9781118646106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Singh S, Singh H, Bueno G, Deniz O, Singh S, Monga H, et al. A review of image fusion: methods, applications and performance metrics. Digit Signal Process. 2023;137(6):104020. doi:10.1016/j.dsp.2023.104020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Francy S, Singh R. Edge AI: evaluation of model compression techniques for convolutional neural networks. arXiv:2409.02134. 2024. doi:10.48550/arXiv.2409.02134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Courty Benoit, Schmidt Victor, Goyal-Kamal, MarionCoutarel, Feld Boris, Lecourt Jérémy, et al. mlco2/codecarbon: v2.4.1 [Software]. 2024 [cited 2025 Oct 21]. Available from: https://zenodo.org/doi/10.5281/zenodo.11171501. [Google Scholar]

30. Tan M, Le QV. EfficientNetV2: smaller models and faster training. arXiv:2104.00298. 2021. [Google Scholar]

31. Jacob B, Kligys S, Chen B, Zhu M, Tang M, Howard A, et al. Quantization and training of neural networks for efficient integer-arithmetic-only inference. In: 2018 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR); 2018 Jun 18–22; Salt Lake City, UT, USA. p. 2704–13. doi:10.1109/CVPR.2018.00286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Patterson D, Gonzalez J, Le Q, Liang C, Munguia LM, Rothchild D, et al. Carbon emissions and large neural network training. arXiv:2104.10350. 2021. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2026 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools