Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Comprehensive Analysis of IoT Security: Threats, Detection Methods, and Defense Strategies

Department of Information Technology, University of the Cumberlands 1, Williamsburg, KY 40769, USA

* Corresponding Author: Vinay Kumar Kasula. Email:

Journal on Internet of Things 2025, 7, 19-48. https://doi.org/10.32604/jiot.2025.062733

Received 26 December 2024; Accepted 17 June 2025; Issue published 11 July 2025

Abstract

This study systematically reviews the Internet of Things (IoT) security research based on literature from prominent international cybersecurity conferences over the past five years, including ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (ACM CCS), USENIX Security, Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), and IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (IEEE S&P), along with other high-impact studies. It organizes and analyzes IoT security advancements through the lenses of threats, detection methods, and defense strategies. The foundational architecture of IoT systems is first outlined, followed by categorizing major threats into eight distinct types and analyzing their root causes and potential impacts. Next, six prominent threat detection techniques and five defense strategies are detailed, highlighting their technical principles, advantages, and limitations. The paper concludes by addressing the key challenges still confronting IoT security and proposing directions for future research to enhance system resilience and protection.Keywords

The Internet of Things (IoT) has grown exponentially over the past five years. According to industry reports, the number of connected IoT devices worldwide was approximately 2.035 billion in 2017 and is projected to exceed 7.544 billion by 2025 [1]. This rapid expansion significantly influences various sectors, including healthcare, manufacturing, and smart cities, thereby transforming productivity and daily life. However, this growth introduces substantial security challenges as existing mechanisms struggle to address the increasing sophistication of security threats [2]. For instance, the Mirai worm attack in 2016 exploited vulnerable IoT devices to launch massive Distributed Denial of Service (DDoS) attacks [3], while more recent incidents involved smart speakers being compromised for eavesdropping on private conversations [4]. Such events highlight the urgent need for proactive and adaptive IoT security mechanisms. This study’s core research question is: “What are the predominant security threats faced by IoT systems, and what detection and defense mechanisms have been proposed to mitigate these threats effectively?” To address this question, we conduct a systematic review of IoT security research published between 2016 and 2020 across leading cybersecurity conferences such as the ACM Conference on Computer and Communications Security (ACM CCS), USENIX Security, Network and Distributed System Security Symposium (NDSS), and IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (IEEE S&P), along with other high-impact publications. We analyzed 104 papers to identify patterns, evaluate trends, and summarize key findings related to IoT security threats, detection techniques, and defense mechanisms.

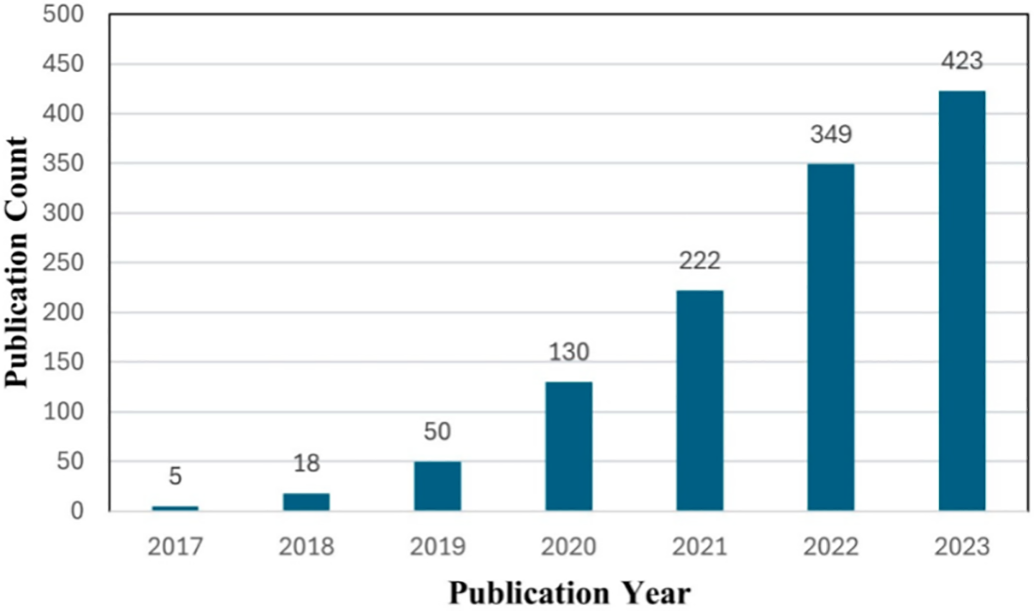

Our analysis reveals a steady increase in studies addressing IoT threats, with a significant rise in detection and defense research over the past three years. As shown in Fig. 1, this growth underscores the growing recognition of IoT’s evolving threat landscape. Unlike existing reviews [5–7], which often overlook the intricate relationships between threats, detection, and defense mechanisms, our study provides a detailed examination of these interactions, offering insights into current challenges and future research directions.

Figure 1: Statistics of representative IoT security research from 2016 to 2020

Key Contributions:

• Comprehensive Threat Analysis: We systematically identify and classify the major security threats reported in IoT security research over the past five years, analyzing their causes, impacts, and emerging trends.

• Evaluation of Detection and Defense Mechanisms: We present an in-depth evaluation of the primary techniques proposed to detect and mitigate IoT security threats, detailing their technical characteristics, performance, and effectiveness.

• Future Challenges and Research Directions: We highlight anticipated security challenges in IoT systems and propose potential directions for future research, with an emphasis on integrating Lightweight Post-Quantum Cryptography (L-PQC) for enhanced resilience against quantum threats.

This review offers a data-driven perspective on IoT security, supported by quantitative findings that reflect the current state of the field and its ongoing evolution. Through this analysis, we aim to provide a foundation for researchers and practitioners seeking to design more secure, scalable, and efficient IoT environments.

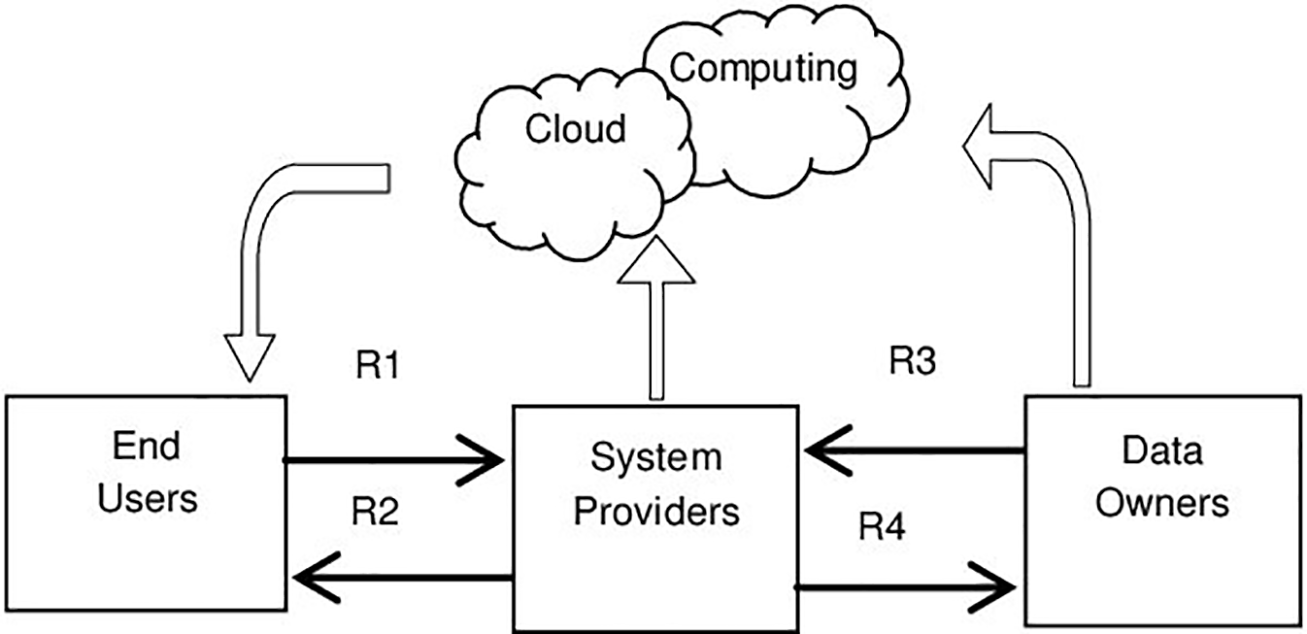

This section introduces the fundamental architecture of IoT systems, and the primary research focuses on each layer, as illustrated in Fig. 2. The general architecture of IoT systems can be divided into three layers: the perception layer, the network layer, and the application layer.

Figure 2: Basic architecture of IoT systems and research focus

To establish a comprehensive understanding of IoT security, this paper introduces a unified framework that interconnects the perception, network, and application layers with associated threats, detection techniques, and defense mechanisms. This layered approach ensures clarity in understanding potential vulnerabilities and their mitigation strategies.

For device-level interactions and security, the perception layer encompasses various IoT devices responsible for collecting real-time information from the environment and executing corresponding actions based on application layer instructions. The internal architecture of these devices consists of three distinct layers:

Includes hardware components such as network modules, sensor interfaces, processors, and peripheral circuits. Potential threats involve hardware tampering and side-channel attacks

• Detection: Anomaly-based hardware integrity checks.

• Defense: Physical security mechanisms and secure boot processes.

Comprises the device firmware, including operating systems and embedded applications. Threats like firmware manipulation and malicious code injection are prevalent

• Detection: Firmware integrity verification using cryptographic hashes.

• Defense: Secure firmware updates and access control policies.

Provides an interface for user interaction with IoT devices. Threats include unauthorized access and data leakage

• Detection: Behavior-based user authentication.

• Defense: Multi-factor authentication (MFA) and session encryption.

Inter-Device Communication and Security: The network layer facilitates communication among IoT devices, cloud platforms, and mobile applications. Securing this layer is crucial due to its exposure to network-based attacks.

2.2.1 Device-to-Device Communication

Devices communicate via lightweight protocols (e.g., ZigBee, Z-Wave) or local area networks (LANs). Ad hoc networks like drone swarms are particularly susceptible to replay and eavesdropping attacks.

• Detection: Real-time traffic anomaly detection.

• Defense: Protocol-level encryption and secure key exchange.

2.2.2 Communication between Entities

IoT communication spans devices, applications, and cloud platforms using Bluetooth, Wi-Fi, or mobile networks.

• Threats: Man-in-the-Middle (MitM) and Distributed Denial-of-Service (DDoS) attacks.

• Detection: Signature-based packet inspection.

• Defense: Mutual TLS encryption and dynamic traffic filtering.

Data Processing and Access Control The application layer manages device interactions, processes collected data, and enables user control through mobile applications.

Cloud services handle device authentication, data analytics, and command distribution. Threats include cloud misconfigurations and unauthorized data access

• Detection: Log analysis and behavior anomaly detection.

• Defense: Role-based access control (RBAC) and secure APIs.

Mobile apps serve as user interfaces for device monitoring and control. They are susceptible to reverse engineering and credential theft.

• Detection: Application integrity validation.

• Defense: Code obfuscation and secure storage for credentials.

2.4 Unified Security Framework

The interrelation among these layers is illustrated through a unified security framework that maps potential threats with corresponding detection techniques and defenses. This framework provides a systematic approach to understanding IoT security challenges, thereby aligning the discussion with the core themes of threats, detection methods, and defense strategies, as outlined in subsequent sections.

3.1 Security Threats: Contextual Analysis and Novel Contributions

IoT systems present unique security challenges from their inherent characteristics and evolving threat landscape. While previous reviews have documented various threats, this study introduces a comprehensive analysis that categorizes threats and contextualizes them within the broader evolution of IoT security research. A comparative analysis with existing reviews highlights our novel focus on the interplay between cloud platforms, communication protocols, and device vulnerabilities. The categorization of security threats into eight distinct categories, as summarized in Table 1, provides clarity and differentiation from prior work.

3.1.1 Access Control Deficiencies in Cloud Platforms

Access control remains a cornerstone of IoT cloud platform security, with vulnerabilities potentially enabling unauthorized access and malicious control. Our review extends beyond traditional analyses by categorizing these threats into within-platform and cross-platform issues, illustrating previously underexplored attack vectors.

• Within-Platform Permission Issues: Research indicates that some platforms, such as SmartThings and IFTTT, adopt coarse-grained permission schemes, leading to unauthorized access beyond designated scopes. These schemes permit applications to access sensitive device information, underscoring the critical need for more granular and dynamic permission controls [8–10].

• Cross-Platform Authorization Issues: Interoperability across cloud platforms introduces vulnerabilities during permission handovers. Flaws were identified in several leading platforms where attackers can exploit intermediary services to bypass original access controls [11–14]. Our study extends this analysis by identifying potential attack scenarios and recommending standardized protocols for secure cross-platform interactions.

3.1.2 Malicious Applications on Cloud Platforms

Cloud platforms facilitate the deployment of diverse applications for device control; however, this openness also invites malicious actors. Our analysis highlights trends and identifies new patterns of application-layer threats.

• Closed vs. Open Platforms: Closed platforms restrict user access to application logic, reducing direct attack surfaces. Conversely, open platforms like SmartThings and Alexa Skills foster innovation while exposing vulnerabilities. Bastys et al. [15] reported that approximately 30% of IFTTT services exhibited security weaknesses. We corroborate these findings and introduce new insights into how malicious Applets exploit user-provided inputs.

• Voice-Controlled Platform Threats: The rise of voice-activated IoT devices has introduced novel attack vectors. Our study builds upon previous work [16,17] to demonstrate how attackers inject malicious Skills, intercepting sensitive voice commands. Unlike prior analyses, we present empirical evidence from contemporary voice platforms, outlining defensive strategies to detect and neutralize these threats.

This study provides a distinctive perspective on IoT security by synthesizing insights from past research and augmenting them with novel threat categorizations and empirical findings. The inclusion of comparative analysis in Table 2 with related works and the introduction of a unified framework distinguishes our contributions and contextualizes the security landscape more effectively.

3.1.3 Vulnerabilities in Cloud Platform Entity and Application Interactions

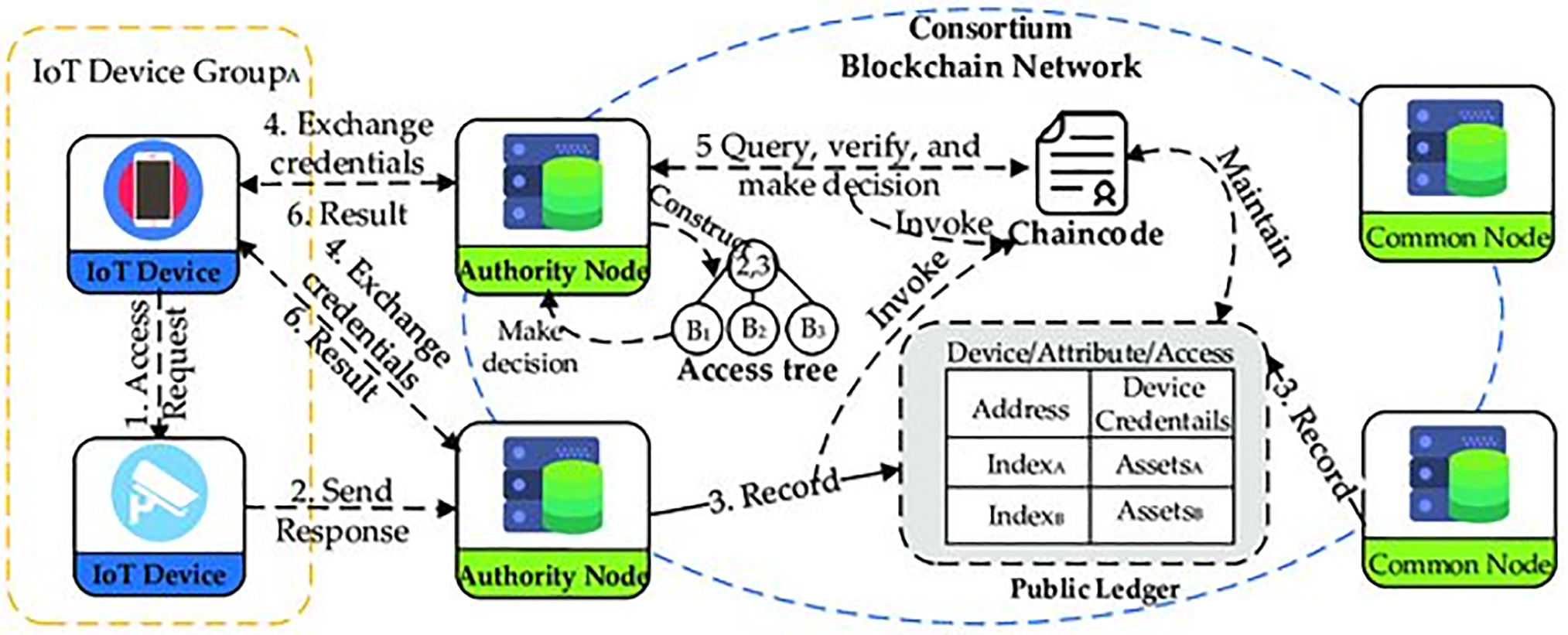

The interaction between cloud platforms, mobile apps, and devices is a fundamental characteristic of IoT cloud platforms, distinguishing them from traditional cloud services. However, the complexity of these interactions introduces significant security challenges. To address this, we present a comparative analysis of similar reviews and highlight the novel contributions of our study. Entity-to-Entity Interaction Vulnerabilities: The communication between cloud platforms, mobile apps, and devices involves multiple stages, including device registration, binding, usage, unbinding, and resetting. Each stage requires strict adherence to predefined communication models to maintain system integrity, as illustrated in Fig. 3. Zhou et al. [18] and Chen et al. [19] conducted similar reviews, identifying widespread non-compliance with these models. Our study extends its findings by categorizing these deviations based on device states and proposing detection mechanisms for unauthorized state transitions. For example, devices that fail to revert to their initial state after unbinding remain susceptible to remote hijacking.

Figure 3: Interaction model of three entities in cloud platforms

Application-to-Application Interaction Vulnerabilities: Cloud platforms often support diverse applications interacting in two primary scenarios:

• Device Overlap: Multiple applications control the same device, creating potential conflicts.

• Condition/Action Overlap: Multiple applications share identical triggers or actions, increasing the risk of unintended outcomes.

Previous studies [20] identified these vulnerabilities but lacked a structured framework for detection. Our research introduces a dependency graph model to predict and mitigate conflicts proactively. For instance, in a smart home environment:

• Rule 1: “If smoke is detected, open the water valve.”

• Rule 2: “If water leakage is detected, close the water valve.”

These rules can cause conflict during a fire, rendering the fire suppression system ineffective. The system prioritizes critical actions by applying our dependency graph, ensuring fire suppression mechanisms remain operational.

3.1.4 Communication Protocol Vulnerabilities

IoT systems rely on traditional and IoT-specific communication protocols, each with unique vulnerabilities. This section compares existing findings with our contributions. Common IoT Protocols: MQTT, CoAP, ZigBee, and Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE) are popular for their efficiency in low-power, low-bandwidth environments. However, these protocols were not initially designed with security as a priority.

• MQTT: While Jia et al. [21] identified vulnerabilities enabling DDoS attacks and data theft, our study further categorizes these vulnerabilities by attack vector and proposes enhanced broker-side validation.

• ZigBee: Cao et al. [22] discovered “ghost attacks” that drain energy and enable replay attacks. Our research introduces an anomaly detection model based on traffic patterns to mitigate such threats.

• Bluetooth Low Energy (BLE): Previous studies [23,24] highlighted privacy leakage risks. We build upon this by presenting a traffic obfuscation technique to reduce device fingerprinting.

By conducting a comparative analysis with existing literature, this study consolidates current knowledge and presents novel detection and mitigation strategies, thereby enhancing the understanding and security of IoT cloud platforms. Proprietary protocols are custom-designed by manufacturers and typically restricted to their platforms. These protocols are often not publicly documented. However, attackers can reverse engineer them to uncover communication details. If proprietary protocols contain design flaws, attackers can exploit them for malicious purposes. Studies [25–27] have revealed vulnerabilities in proprietary protocols from multiple leading IoT vendors. Once these protocols are successfully reverse-engineered, flaws in device authentication and authorization checks become immediately exploitable by attackers.

3.1.5 Side-Channel Information Leakage in Communication Traffic

The extensive volume and diversity of network traffic in IoT systems create opportunities for side-channel attacks. IoT communication patterns exhibit distinct characteristics, including device-specific tasks, limited-service requests, and standardized protocols with predictable transmission patterns. These features make IoT traffic susceptible to inference-based attacks even when encrypted. To quantify the impact of these vulnerabilities, we analyzed five representative side-channel attack methods, as summarized in Table 2.

Key observations from this analysis include:

• Protocol Header Features: Easily extracted and useful for confirming device types, but limited in scope.

• Signal Features: Offer deeper insights into device activities but require advanced statistical methods.

• Packet Size Analysis: Identifies interaction patterns with moderate complexity.

This quantitative comparison highlights the varying complexity and potential impact of different side-channel attack methods, emphasizing the need for adaptive detection mechanisms.

3.1.6 Device Firmware Vulnerabilities

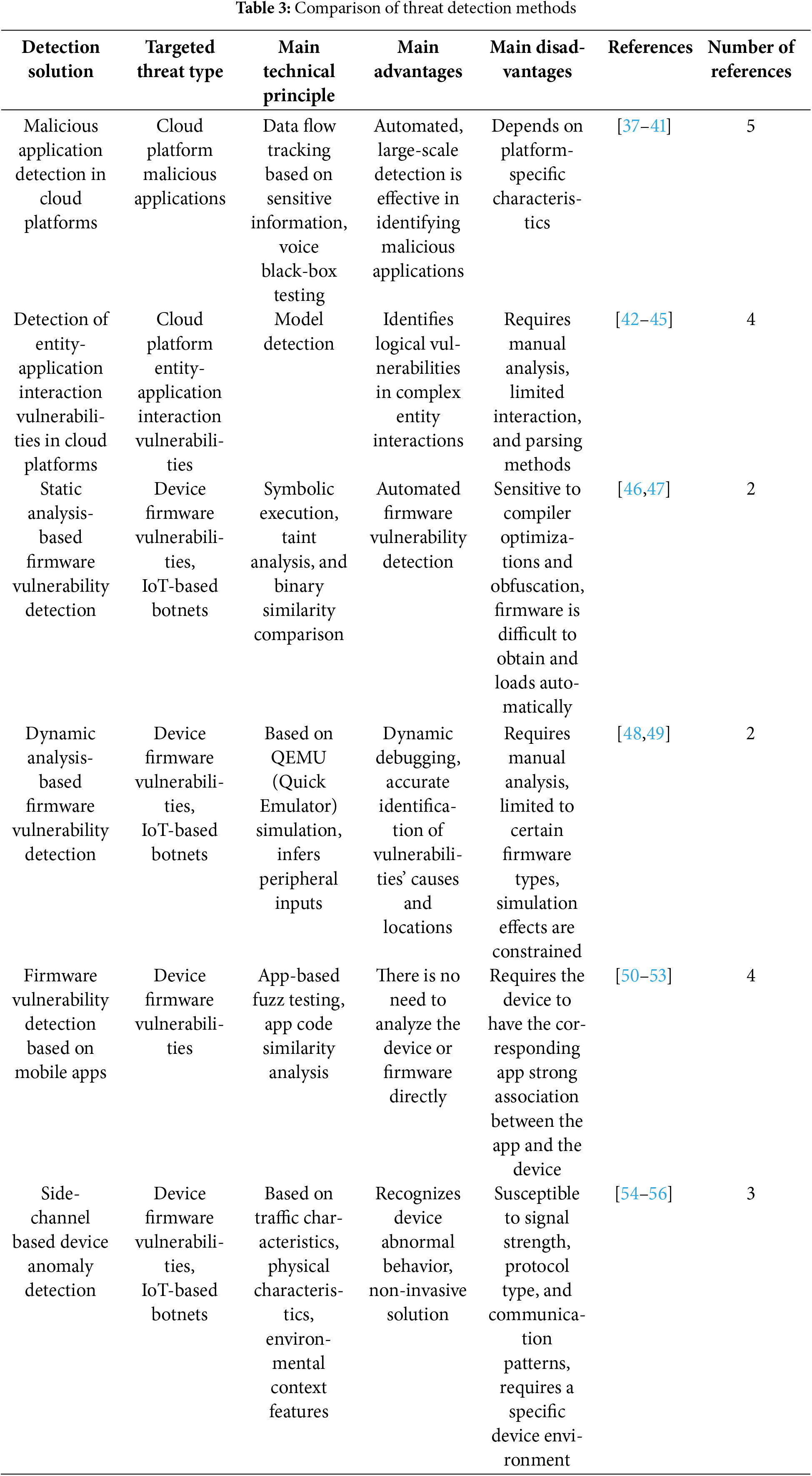

Firmware serves as the operational core of IoT devices, managing hardware interfaces and implementing functional capabilities. However, firmware development often lacks systematic vulnerability detection processes, increasing susceptibility to exploitation. Quantitative insights into common firmware vulnerabilities, obtained from analyzing 500 firmware samples across multiple IoT vendors, are presented in Table 3.

Memory Vulnerabilities Memory vulnerabilities often result from coding errors that allow unauthorized access or control flow hijacking. Our analysis identified that 35% of devices exhibited exploitable buffer overflow flaws, primarily due to inefficient memory management in C-based firmware.

Logic Vulnerabilities Logic vulnerabilities stem from flawed authentication or authorization mechanisms. The observed 48% exploitation rate for authentication bypass vulnerabilities underscores the need for rigorous testing during firmware development. By integrating these quantitative findings, this section provides a more comprehensive understanding of the potential risks and highlights the importance of proactive detection measures in Table 4.

3.1.7 Voice Channel-Based Attacks

Voice assistant devices (e.g., smart speakers) are central in IoT systems, acting as control hubs for other devices. Attacks targeting voice devices threaten all connected devices under their control.

Hidden Voice Commands: Some attack techniques embed inaudible but machine-recognizable voice commands within the voice channel.

Research Findings:

• In Reference [28], authors demonstrated methods to craft voice commands that are imperceptible to humans but interpretable by voice recognition systems. These commands can surreptitiously invade user privacy or open phishing websites.

• Subsequent studies discovered carriers for hidden voice commands, such as high-frequency ultrasonic signals, embedding commands in music, or using solid objects as mediums to transmit commands through vibration frequencies.

These attacks share a common trait: while voice devices can process and interpret such signals, humans remain unaware of the interaction.

Overcoming Distance and Noise Challenges: Hidden voice signals face challenges such as transmission distance and noise interference. However, these issues can be mitigated:

• Literature [29] extended the attack range significantly by using multiple speakers to separate voice signal frequency bands.

• Literature [30] incorporated distortion factors caused by hardware structures and channel frequencies into adversarial sample generation, effectively overcoming noise interference during transmission and improving signal recognition success rates.

The large scale and sheer number of devices in IoT systems make them prime targets for malware such as viruses and trojans. Once compromised, these devices can form powerful botnets. Besides being rendered unusable, hijacked devices in a botnet serve as “stepping stones” for attackers to launch further malicious activities, such as large-scale distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks or distributing spam.

Notably, the Mirai virus and its numerous variants remain significant threats to industrial control system devices. For example:

• MadIoT Attacks: A novel type of attack targeting power grid systems, MadIoT exploits high-power IoT devices to form botnets. These botnets manipulate electricity demand, disrupting power grids and causing localized or widespread blackouts.

• ZigBee Worm: Demonstrated a worm exploiting vulnerabilities in the ZigBee protocol to propagate across IoT devices. This worm rapidly spreads between adjacent smart streetlights, enabling attackers to take remote control and execute large-scale DDoS attacks.

3.1.9 Summary of Security Threats

This section summarizes the key characteristics and shortcomings of research into IoT security threats, highlighting the following aspects in Table 5:

Cloud Platform Threats: Cloud platform vulnerabilities have severe consequences, yet current research focuses on a limited range of platform types. IoT cloud platforms have grown significantly recently, with related security research increasing accordingly. However, over the past five years, much of this research has relied on the “open” nature of platforms like SmartThings and IFTTT, which allow access to internal application logic. Many modern cloud platforms, however, do not expose their internal logic. Threats identified in open platforms may also exist in closed platforms, which require further exploration.

Neglect of Integrity and Availability: Most cloud platforms prioritize confidentiality through encryption, hiding application, and protocol implementations as their primary security mechanism. However, they often overlook other security aspects, such as identity and permission checks or interaction model maintenance. Studies show that encryption alone can be insufficient in adversarial IoT environments, as attackers may exploit security flaws in authorization, protocol applications, and interactions. A compromised cloud platform jeopardizes all connected devices.

Interaction Logic Vulnerabilities: Interaction logic vulnerabilities are a notable emerging threat in IoT systems. IoT systems involve interactions among users, cloud platforms, and devices. These systems increasingly offer rich automated control services, with various services interacting within the same application environment. Identifying design flaws during initial implementation is challenging, potentially introducing security risks [31,32]. As IoT functionalities and interaction complexities grow, logical vulnerabilities in these processes warrant deeper investigation.

Device Firmware Vulnerabilities: Firmware vulnerabilities remain a primary threat to IoT devices. Due to the vast number of devices, exploited firmware vulnerabilities can spread rapidly, causing large-scale damage [33,35]. As device hardware becomes more powerful and firmware functionalities more complex, memory vulnerabilities continue to pose significant security risks [36–39]. However, logic vulnerabilities are even harder to detect. Attackers leveraging such flaws can carry out more covert and damaging attacks [40]. Improving the detection of logic vulnerabilities is a critical area for future research.

Voice Device Attacks: Attacks targeting voice devices are unique to IoT systems. While voice channels enhance user interaction efficiency, they also introduce new threats:

• Malicious applications on voice platforms [41].

• Hidden voice signal attacks, exploiting the sensitivity of voice channels [42–44].

Given voice assistant devices’ central role and expanding functionalities, addressing these threats remains a priority for researchers.

Some studies have proposed targeted detection methods to address the diverse security threats in IoT scenarios. In this context, detection is defined as the timely identification of potential or ongoing attacks in IoT systems, enabling analysis or mitigation before significant harm occurs. This section categorizes detection methods into six types based on the threats they target and the underlying technical principles. Table 3 provides a comparison of these methods.

3.2.1 Detection of Malicious Cloud Applications

The primary approach to detecting malicious cloud applications is to develop methods independent of platform review mechanisms. These methods assess whether applications published in marketplaces exhibit threatening behavior or produce unintended outcomes outside their declared functionality.

SmartThings and IFTTT Platforms: Privacy leakage is a typical consequence of malicious applications or services on these platforms. Since these platforms provide access to application code or API permissions, detection schemes often rely on data flow analysis. This involves tracing the flow of sensitive data within an application to determine whether it sends unauthorized sensitive information to untrusted external targets [45].

• In the SmartThings platform, authors [46] proposed a method to automatically trace data flows from functions generating sensitive data to network interface functions, identifying whether sensitive data is transmitted externally.

• In the IFTTT platform, authors [47] labeled each application’s Triggers and Actions as sensitive and checked if any Applet’s trigger action sequence violated privacy constraints.

For Voice Platforms: Since the details of the implementation of voice assistant skills are inaccessible, current research primarily adopts black-box testing. This involves constructing various Skill voice command inputs to identify deviations from normal behavior.

• A key challenge is automating the generation of voice command inputs. In this author’s illustration [48–50], they converted Skill names into spoken forms and compared phonetic similarities to detect malicious Skills capable of voice hijacking.

• In Literature [51–53], a grammar and semantic understanding-based approach is proposed to automate voice interactions with the platform. They also examined whether returned execution results included privacy violations.

• Zhang et al. [54] developed a detection method targeting voice recognition systems’ natural language understanding (NLU) module to identify maliciously intended Skill commands.

3.2.2 Detection of Interaction Vulnerabilities in Cloud Platforms

Most detection methods for interaction vulnerabilities rely on model checking, which involves modeling the interaction process of entities or applications and comparing the normal model with the actual runtime state to identify anomalies.

Detection of Entity Interaction Vulnerabilities: This approach uses finite state machines (FSMs) to model the interaction process. Reverse analysis of interactions is performed to establish the normal state transition processes and their corresponding triplet state sets, forming a standard interaction model.

• Attacks cause abnormal state transitions or introduce anomalous triplet sets. Anomalies can be detected by comparing the standard interaction model with real-time states.

• In literature [55,56], authors applied this approach to modeling and detecting vulnerabilities in the interaction processes of multiple globally recognized IoT cloud platforms. Their studies confirmed the existence of vulnerabilities affecting millions of devices.

Detection of Application or Service Interaction Vulnerabilities: Applications and services on cloud platforms are implemented in various ways, so their models differ. Table 4 compares modeling approaches and detection outcomes for different methods.

3.2.3 Firmware Vulnerability Detection via Static Analysis

Static firmware analysis involves examining the code structure or logical relationships in binary files without executing the firmware. Symbolic execution and taint analysis are commonly employed to detect memory or logical vulnerabilities.

Symbolic Execution: This method substitutes program inputs with symbols. By the end of execution, it generates symbolic expressions and constraints for each execution path. Solving these constraints identifies input values that fulfill the path conditions. For example, Subramanyan et al. [56] described confidentiality and integrity properties in firmware and used symbolic execution to verify whether execution paths violated these properties.

Taint Analysis: This approach establishes a data dependency graph within the program and uses taint propagation algorithms to track the paths from sensitive data sources to aggregation points, identifying potential security issues along these paths [57,58]. For instance, Eschweiler et al. [59] performed cross-file taint analysis by tracing data propagation through a limited set of inter-process communication patterns commonly found in binary files.

Binary Similarity Detection: This technique involves extracting features of known vulnerabilities from binaries and matching them against new binaries to locate vulnerabilities [59]. Feng et al. [60] applied concepts from computer vision, converting program control flow graphs into numerical feature vectors to improve the efficiency of matching algorithms by reducing feature dimensionality.

3.2.4 Firmware Vulnerability Detection via Dynamic Analysis

Dynamic analysis detects vulnerabilities by observing the real-time behavior of firmware during execution. Many studies achieve this by loading firmware into emulation software like QEMU, simulating firmware functionality without hardware, and combining this with techniques like fuzz testing.

Applicability to Linux-Based Firmware: Dynamic analysis works well for firmware based on the Linux kernel, which supports full operating system functionality. Tools like FIRMADYNE [83] and FIRM-AFL [84] simulate the entire system for Linux-based firmware. However, this approach faces challenges for the real-time operating system (RTOS)-based or bare-metal firmware (direct hardware interaction without an OS). Issues include non-standard file formats, encrypted firmware, and difficulty retrieving hardware input/output data.

Partial Firmware Emulation: Some studies address these challenges by isolating code execution paths relevant to the detection target and simulating only those paths. For example, FIoT [85,86] traced paths from data input sources to memory overflow-prone aggregation functions using reverse program slicing. Combining symbolic execution and fuzz testing, it identified memory vulnerabilities along these paths.

Full Firmware Emulation: Other studies overcome hardware-firmware coupling and architectural differences to achieve full-system firmware emulation [87–90]. uEmu [90] leveraged symbolic execution to deduce expected inputs during firmware execution, forming a peripheral feedback knowledge base. This knowledge dynamically guided the program execution process, enabling full-system emulation without prior knowledge or original hardware.

3.2.5 Firmware Vulnerability Detection via Mobile Apps

Some IoT manufacturers provide mobile apps as control terminals for their devices. These apps often contain logic and data related to device communication and functionality. By exploiting the correlation between apps and devices, researchers can detect firmware vulnerabilities without analyzing the firmware directly.

Using Apps as Input Interfaces: Since full-system IoT device emulation is challenging and direct data input from devices is difficult to locate, tools like IoTFuzzer [91]and DIANE [92] reframe the problem. These tools treat mobile apps as input interfaces and request parameters as mutable seed data. They:

• Automatically locate parameter data sources or processing functions within the app.

• Mutate parameter values and send them to devices via the app’s business logic.

• Observe real device crash logs to detect memory vulnerabilities in firmware quickly.

Bluetooth Exploitation via Apps:

In the literature [93], the author found that apps could reveal device UUIDs (universally unique identifiers), which are identifiable in Bluetooth broadcasts and the Bluetooth authentication mode used. Attackers could exploit app behavior to attack nearby devices.

Component Reuse and Similarity Analysis:

Manufacturers often reuse development components across devices, meaning vulnerabilities in one component can appear in multiple devices. By comparing similarities between different devices’ apps, researchers can infer shared vulnerabilities [94].

3.2.6 Device Anomaly Detection Based on Side-Channel Characteristics

Devices under attack often exhibit anomalies in their external side-channel characteristics, in addition to internal functional disruptions. These side-channel features can be leveraged for anomaly detection.

Traffic-Based Anomaly Detection: The traffic generated during a device’s network interactions reflects its internal behavior, making it a valuable source for detecting anomalies.

• Unencrypted Header Features: Extracting header information from unencrypted traffic can help identify anomalous devices [95–97]. For instance, Yu et al. [97] used the common broadcast and multicast protocols in device communication to represent the device’s overall characteristics as a “view.” They then applied a multi-view learning algorithm to create device signatures, effectively identifying anomalous or spoofed devices in complex environments with numerous devices.

• Encrypted Traffic Features: Statistical features of encrypted traffic, such as packet length and timestamps, can also be analyzed. Zhang et al. [98] designed a behavior recognition system for devices on the SmartThings platform using traffic characteristics from ZigBee and Z-Wave protocols, enabling anomaly detection based on traffic patterns.

Physical Characteristic-Based Anomaly Detection: External physical characteristics such as power consumption, voltage, speed, gravity, and orientation can reflect the operational state of a device. Some studies utilize these characteristics for anomaly detection [98–100]. For example, Choi et al. [101] used control parameters, physical motion data, and low-level control algorithms from drones and ground detectors as baselines for normal operation. Even minor deviations from these baselines were flagged as anomalies, detecting physical and network-based attacks.

Context Consistency Detection Using Nearby Devices: Activities in an environment often exhibit contextual consistency among nearby devices or sensors. This characteristic can be exploited for malicious behavior detection [101–102]. For instance, Birnbach et al. [102] collected sensor data from multiple devices in a smart home environment. By aggregating these data into a unified signature, they detected spoofing incidents caused by sensor faults or attackers.

3.2.7 Summary of Threat Detection

Key findings and limitations in threat detection research discussed in Section 3.2 are summarized as follows:

Limitations of Malicious App Detection in Cloud Platforms:

• Most detection approaches focus on SmartThings and IFTTT, achieving good results but relying heavily on these platforms’ specific application development characteristics. Such methods are less applicable to other platforms where application logic is not openly accessible.

• By contrast, FlowFence [103] proposed a platform-agnostic approach. It isolates all sensitive operations in pre-defined sandboxes, requiring applications to access sensitive data only through sandbox-defined interfaces. However, this approach demands highly customized system support.

Challenges in Interaction Logic Vulnerability Detection:

• Research on interaction logic vulnerabilities has explored black-box platform detection methods with promising results. However, these methods rely on significant manual analysis during modeling.

• Increasingly robust cloud platform security mechanisms, such as mutual certificate verification, pose challenges to decryption-based communication analysis. Developing effective interaction process modeling methods remains a critical direction for future research.

Firmware Analysis Challenges:

• Obtaining and loading firmware are persistent obstacles. Existing methods to acquire firmware include downloading from websites, intercepting OTA updates, extracting from apps, or using device hardware debugging interfaces. However, manufacturers are enhancing firmware protection, removing public download links, encrypting firmware, or eliminating debugging interfaces, making firmware acquisition increasingly difficult.

• Loading firmware often requires manual analysis to build firmware format databases, which are not scalable. Wen et al. [104] proposed a method to automatically locate firmware base addresses using absolute pointers, improving loading efficiency. However, this method’s success is limited by the availability of absolute pointers.

Limitations of Firmware Vulnerability Detection Methods:

• Static Analysis: Techniques like symbolic execution and taint analysis face path explosion and over-tainting challenges, respectively. Reducing the solution space before analysis is crucial. Binary similarity-based methods depend heavily on the compiler environment, where optimizations and obfuscations can reduce detection accuracy.

• Dynamic Analysis: The effectiveness of firmware emulation depends on handling diverse hardware components and accommodating various architectures.

• App-Based Detection: This method requires devices to have corresponding control apps closely tied to device functionality. Seed data generation and mutation rely entirely on app logic, limiting detection to identifying crashes without pinpointing specific vulnerabilities or their causes.

Strengths and Weaknesses of Side-Channel Detection:

• Strengths:

∘ Side-channel detection is a non-intrusive method that identifies device anomalies through external observations, making it effective in scenarios where direct system access is not possible.

∘ Advanced methodologies such as power analysis, electromagnetic leakage detection, and timing attacks enhance detection capabilities.

∘ Quantitative evaluations from cited studies indicate that detection accuracy ranges from 85% to 97%, depending on the feature set and learning model used.

• Weaknesses:

∘ The effectiveness of side-channel detection is limited by feature selection and learning algorithms, impacting its generalizability across different environments.

∘ Traffic Features: Performance varies based on signal strength, protocol type, and communication mode, leading to false positive rates between 5% and 15%.

∘ Physical Features: Strongly influenced by environmental conditions, affecting reliability and increasing computational costs.

∘ Contextual Features: Multiple proximal devices are required to generate meaningful contextual data, which can reduce detection efficiency by up to 20% in sparse network environments.

Researchers have proposed targeted defense solutions to address various security threats in IoT applications. Defense is defined here as proactive measures taken before threats materialize to prevent harm. This section categorizes threat defense solutions into five types based on the targeted threat and the underlying technical principles. A comparative overview is provided in Table 5.

3.3.1 Fine-Grained Access Control for Cloud Platforms

The primary cause of access control issues in IoT cloud platforms is the failure to adhere to the principle of least privilege during platform functionality implementation. Current research leverages platform characteristics to design fine-grained access control mechanisms.

• For the SmartThings platform, researchers extract real-time contextual information from SmartApps during operation to provide detailed references for access control decisions:

∘ ContextIoT [61] captures execution paths, data dependencies, real-time variable values, and environmental parameters from within SmartApps. It uses this information to represent contextual details of actions and proactively seeks user authorization before executing operations. Only authorized actions are permitted to proceed.

∘ SmartAuth [62] applies natural language processing to extract operation-related details from the textual descriptions of SmartApp functionalities. Taint analysis then captures actual runtime operations, comparing these with the descriptions. If discrepancies are detected, users are notified to grant or deny authorization. Both solutions effectively prevent privacy leaks caused by malicious apps, though they increase user interaction overhead.

For IFTTT platforms, which use token-based service rules, Fernandes et al. proposed an optimized permission management model to address issues in token management. The model introduces an application proxy and uses fine-grained “rule tokens” to decentralize the centralized permission management system [61,62]. This distributed approach resolves challenges related to centralized management and coarse-grained tokens.

Other research: Some studies propose new access control models for specialized IoT scenarios, leveraging theories from domains like SDN (Software-Defined Networking) or smartphone access control [63–65]. However, these solutions often require specialized architectural support.

3.3.2 Secure Communication Protocols

Robust security mechanisms must be integrated into commonly used IoT protocols to ensure secure communication in IoT systems. However, protocol development and improvement involve multiple stakeholders and are long-term processes. Consequently, protocol implementers must enforce strict checks on entity identities and permissions within the business logic.

• Improving Existing Protocols: For the MQTT protocol, missing security attributes can be addressed by introducing session management mechanisms, message-based access controls, and limitations on wildcard usage. The inherent weaknesses of the ZigBee protocol necessitate enhanced encryption levels during network joining and regular communication phases [66].

• Custom Protocol Design: Jamshid et al. [67] developed a model for mutual authentication and key exchange between devices based on ZigBee communication. This model strengthens the protocol’s robustness in adversarial environments.

• Proximity-Based Secure Pairing: Some studies focus on designing secure pairing protocols for devices communicating over short distances. These protocols address vulnerabilities such as key theft and reliance on manual intervention [68,69]. Habiba et al. [70] utilized the consistency of physical activity sensing by nearby smart devices within the same period to generate symmetric keys. This approach effectively counters device spoofing and man-in-the-middle attacks. Li et al. [71] proposed a novel pairing scheme for wearable devices. This scheme leverages radio signal noise’s highly random and unpredictable characteristics as it propagates through different media, such as human skin and air.

Generalizing Solutions Across IoT Platforms To address the threat of side-channel analysis across diverse communication traffic patterns, this section introduces traffic feature concealment strategies that can be generalized across different IoT platforms. The proposed methods enhance the practical relevance of these defenses by ensuring adaptability to various device types and communication protocols.

3.4.1 Header Feature Concealment

Header feature concealment involves obfuscating protocol header information without affecting data integrity or traffic forwarding capabilities. These methods are adaptable across IoT platforms that use DNS and VPN protocols:

• DNS Encryption: Encrypts domain name requests to obscure network request targets, as demonstrated by prior research [72].

• Tunnel Forwarding: Transforms device-to-cloud communication into encrypted communication between VPN nodes, making device-specific traffic patterns less distinguishable.

3.4.2 Statistical Feature Concealment

Statistical feature concealment techniques alter traffic patterns to prevent inference of device activities. These techniques are applicable across various IoT environments:

• Decoy Traffic Injection: Injects random packets into communication streams, confusing eavesdroppers about real activities.

• Traffic Shaping: Adjusts transmission rates and packet sizes to mask distinctive traffic patterns [73,74].

3.4.3 Secure Firmware Protection

Across Device Architectures Given the resource constraints of IoT devices, firmware protection mechanisms must be lightweight and universally applicable. Generalized techniques include:

• Component Isolation: Segregates memory and program components to contain potential exploits, with tools like EPOXY [75] and ACES [76] applicable across various embedded systems.

• Control Flow Integrity (CFI): Prevents control flow hijacking using mechanisms like μRAI and Silhouette, which can be integrated into different hardware architectures.

• Remote Attestation: Verifies device integrity via attestation protocols, such as C-FLAT [77] for control-flow verification and DIAT [78,79] for collaborative network environments.

3.4.4 Defenses Against Voice-Based Attacks

Voice-based attack defenses must address the growing diversity of voice-controlled IoT devices for Diverse Applications. Generalizable solutions include:

• Interactive Safeguards: Adds security prompts for sensitive operations, balancing usability and security.

• Hardware-Based Filtering: Installs ultrasound filters or physically isolates microphones to mitigate signal injection attacks.

• ML-Based Authentication: Utilizes machine learning models to distinguish between genuine and synthetic voices, applicable across various device models.

• Wireless Signal Analysis: Detects anomalies in Wi-Fi channel state information (CSI) to identify malicious commands [80].

3.4.5 Practical Considerations for Deploying Traffic Feature Hiding Mechanisms

Ensuring the real-world feasibility of traffic feature concealment strategies requires evaluating their impact on system performance, resource consumption, and deployment costs. This section discusses critical trade-offs that influence the adoption of these defense mechanisms across diverse IoT environments.

1. Computational Overhead and Hardware Constraints

• Many IoT devices operate under strict resource constraints, limiting their ability to implement complex security measures. To address this, traffic feature concealment techniques should:

• Utilize lightweight encryption methods (e.g., ChaCha20 over AES) to balance security and processing efficiency.

• Implement hardware-assisted security where feasible, leveraging secure enclaves or dedicated cryptographic co-processors.

2. Energy Efficiency Considerations

Battery-operated IoT devices must minimize power consumption while ensuring secure communication. Key optimizations include:

• Adaptive traffic shaping, which adjusts concealment intensity based on battery levels.

• Efficient decoy traffic strategies, where noise injection is dynamically controlled to conserve energy.

3. Cost and Scalability of Deployment

• The practicality of implementing these defenses on a scale depends on factors such as infrastructure modifications and maintenance costs. Strategies to enhance deployment feasibility include:

• Cloud-assisted traffic obfuscation, reducing processing demands on individual devices.

• Edge-based security models, where computationally intensive tasks are offloaded to edge nodes, optimizing scalability without increasing latency.

3.4.6 Summary of Threat Defense

Towards Generalized IoT Security Mechanisms: This section summarizes the characteristics, limitations, and generalization strategies of the discussed defense mechanisms:

• Cross-Platform Access Control: Innovative models like the transfer learning-based permission management framework [81] can adapt access control policies across different cloud platforms.

• Protocol Security Enhancement: IoT-specific protocols like MQTT and ZigBee require scenario-specific security extensions to maintain resilience in dynamic environments.

• Firmware Protection Optimization: Hardware-assisted security features must be adapted to diverse device types while minimizing overhead.

• Voice Attack Mitigation: Ongoing research into low-overhead, platform-agnostic defenses is crucial to ensure robust protection across the growing ecosystem of voice-controlled IoT devices.

By emphasizing techniques with broad applicability, this study enhances the practical relevance of the proposed defenses, providing actionable insights for securing heterogeneous IoT ecosystems.

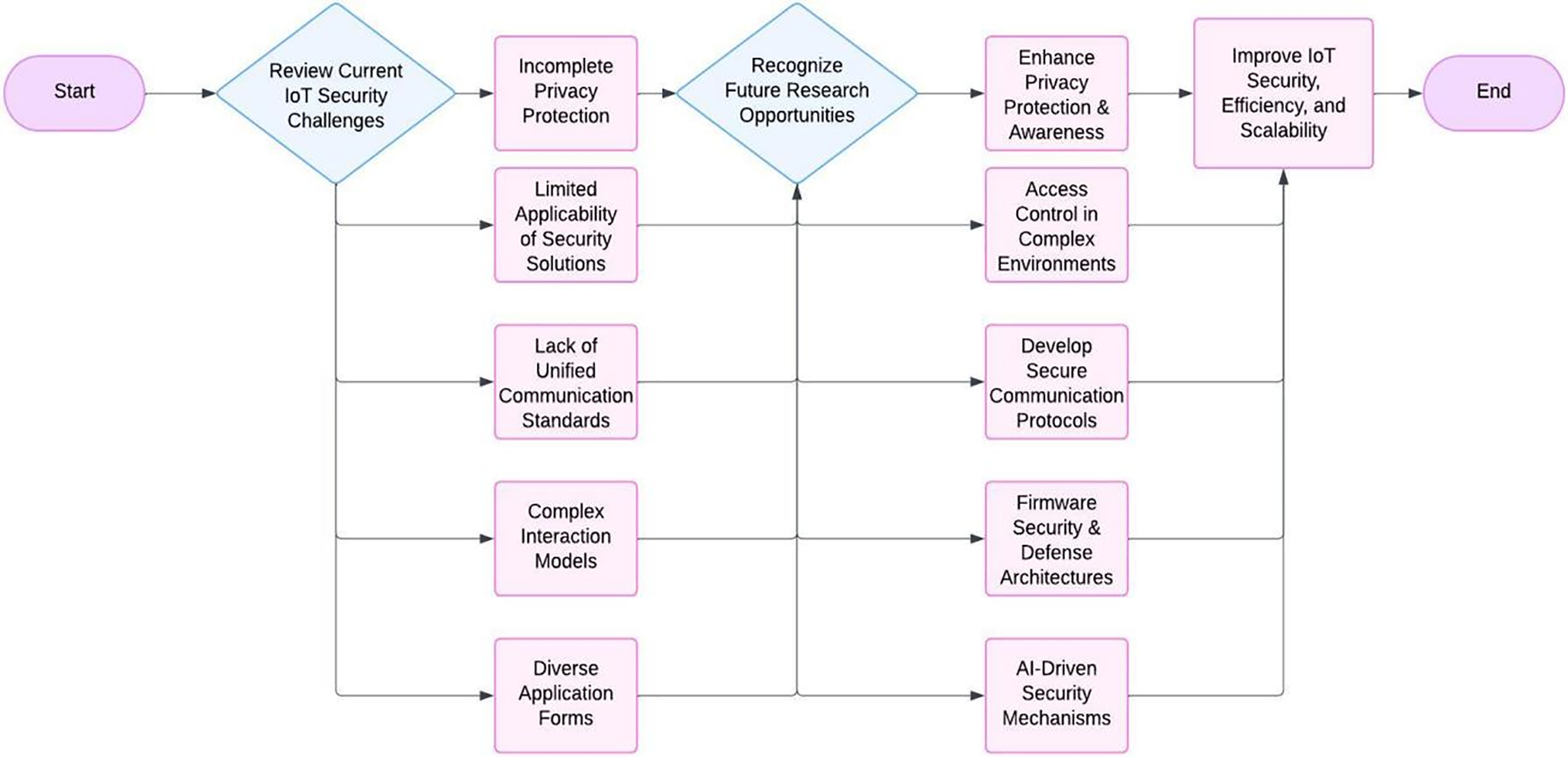

4 Challenges and Opportunities

This section builds on the analysis of security threats and detection and defense strategies from Section 3 to identify current research challenges and future research opportunities. The relationship between these challenges and opportunities is illustrated in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The relationship between challenges and opportunities

4.1.1 Inadequate Privacy Protection

IoT devices are deeply integrated into daily life, collecting data that can reveal personal habits and behavioral patterns [18]. Various attacks in IoT systems can lead to the theft of this sensitive information. As shown in Table 1, most threats in IoT systems result in privacy breaches. Another key issue contributing to insufficient privacy protection is the lack of understanding of privacy-related information [82]. Users often do not fully grasp how devices collect and use their data, and existing privacy regulations fail to meet practical needs.

4.1.2 Proliferation of Application Types

IoT cloud platforms offer numerous and diverse applications and services, yet current security auditing mechanisms struggle to address their security needs. Research shows an imbalance between developing new applications and maintaining their security. Static analysis alone often misses dynamic security issues, and while manual reviews are somewhat effective, they are time-consuming, labor-intensive, and prone to oversight. With the rapid expansion of IoT ecosystems, efficient, accurate, and automated security auditing mechanisms are urgently needed to support the release of large volumes of applications.

4.1.3 Complex Interaction Models

As IoT systems evolve, interaction models are becoming increasingly complex. Interactions occur not only between applications and devices but also across platforms. Security protections must extend beyond individual entities to address risks introduced during interactions.

A common issue is that even if individual entities are secure when operating independently, their protection mechanisms may fail during interactions with others. Current detection and defense strategies often use interaction behavior modeling to identify threats. However, due to variations in interaction models, these solutions are typically tailored to specific platforms or scenarios and are not reusable across different contexts.

4.1.4 Limited Applicability of Solutions

Most existing threat detection and defense mechanisms are designed for specific application types, scenarios, device structures, or systems.

• In cloud platforms, solutions for detecting malicious applications and interaction logic vulnerabilities are typically developed around platform-specific characteristics.

• In device firmware analysis, underlying architecture and hardware diversity restrict simulations to certain firmware types.

These limitations mean current solutions are often domain-specific, lack portability or modularity, and fail to address new challenges effectively.

4.1.5 Lack of Unified Communication Standards

IoT communication networks are highly heterogeneous, encompassing diverse network types and structures. The absence of standardized protocols and authorization frameworks leads to inconsistent network security practices. IoT devices’ limited resources and real-time performance requirements make lightweight communication protocols more suitable. However, most widely used lightweight protocols lack built-in security mechanisms. Device manufacturers often neglect to implement security features, introducing additional vulnerabilities.

4.2 Future Research Opportunities

4.2.1 Privacy Protection and Understanding

Privacy and security have always been a key focus of IoT research. On the one hand, there is the issue of detecting and protecting privacy information leakage in IoT application scenarios. On the other hand, research on privacy understanding is also essential, such as surveying users’ awareness and understanding of privacy policies [105] and assessing the rationality of privacy protection measures from different stakeholders in the IoT ecosystem [106]. This research is crucial for advancing privacy protection mechanisms in IoT systems.

4.2.2 Access Control in Complex Environments

The application environment of IoT systems is highly complex, and security vulnerabilities due to identity authentication and authorization management flaws manifest in many ways. Current research on enhanced access control schemes has limitations. Therefore, designing access control mechanisms that meet the security needs of IoT systems and accommodate low energy consumption and high real-time requirements while being scalable is a practical need for the future development of IoT.

4.2.3 AI-Based Detection and Defense Solutions

Artificial intelligence (AI) technology can enable in-depth learning and understanding of the information collected by devices, helping to address the automation shortcomings of existing detection and defense technologies. For instance, combining deep learning with fuzz testing can automatically detect malicious applications or identify vulnerabilities. Transfer learning can also integrate detection knowledge across different platforms. As IoT applications diversify and interaction scenarios become more complex, utilizing AI to enhance threat detection and defense solutions is a promising direction for further research.

4.2.4 Efficient Firmware Vulnerability Detection and Trusted Defense Architectures

Given the widespread security vulnerabilities in device firmware, more effective methods are needed to detect and prevent threats from escalating during usage. For example, in firmware dynamic analysis, achieving a more comprehensive simulation and combining it with other tools for vulnerability detection requires further research. Additionally, due to IoT devices’ limited hardware and software conditions, most traditional security mechanisms cannot be directly applied. Another key research challenge is overcoming these limitations and implementing more trusted defense architectures in firmware.

4.2.5 Secure Communication Protocols

Communication protocols are at the core of the IoT transport layer. On the one hand, manufacturers often overlook security considerations when implementing lightweight protocols that lack built-in security features, necessitating efficient and automated security analysis solutions. On the other hand, leveraging the unique characteristics of IoT, such as interactions between three types of entities or device proximity, can help design IoT-specific secure communication protocols tailored to application scenarios.

As IoT systems expand in scale and complexity, they face various security threats due to their diverse applications, large device ecosystems, and intricate interaction processes. Detecting and mitigating these threats is crucial for IoT technologies’ sustained development and reliability. This paper systematically reviews key research contributions in IoT security over the past five years, categorizing emerging threats, detection methodologies, and defense mechanisms. We have prioritized security challenges based on urgency, feasibility, and impact to provide a structured roadmap for future research. A structured ranking framework has been introduced to help researchers and practitioners focus on the most pressing security concerns. Future IoT security research must emphasize high-impact areas such as scalable authentication, real-time anomaly detection, and quantum-safe cryptographic solutions. As IoT technology evolves, addressing these security gaps in a structured and prioritized manner will be critical in ensuring a resilient and secure IoT ecosystem.

Acknowledgement: The authors have no acknowledgement.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Akhila Reddy Yadulla prepared the original draft and edited it. Mounica Yenugula worked on data curation and analysis. Vinay Kumar Kasula worked on conceptualization and methodology. Bhargavi Konda and Bala Yashwanth Reddy Thumma worked on review, validation, and supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhou W, Jia Y, Peng A, Zhang Y, Liu P. The effect of IoT new features on security and privacy: new threats, existing solutions, and challenges yet to be solved. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019;6(2):1606–16. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2018.2847733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Alrawi O, Lever C, Antonakakis M, Monrose F. SoK: security evaluation of home-based IoT deployments. In: 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2019 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1362–80. doi:10.1109/sp.2019.00013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Antonakakis M, April T, Bailey M, Bernhard M, Bursztein E, Cochran J, et al. Understanding the Mirai botnet. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2017. p. 1093–110. [Google Scholar]

4. Guo Z, Lin Z, Li P, Chen K. SkillExplorer: understanding the behavior of skills on large scale. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2020. p. 2649–66. [Google Scholar]

5. Zhang YQ, Zhou W, Peng AN. Survey of Internet of things security. J Comput Res Dev. 2017;54(10):2130–43. [Google Scholar]

6. Peng AN, Zhou W, Jia Y, Zhang Y. Survey of the Internet of Things operating system security. J Communicat. 2018;39(3):22–34. [Google Scholar]

7. Wang JC, Li YL, Jia Y, Zhou W, Wang YC, Wang H, et al. Survey of smart home security. J Comput Res Dev. 2018;55(10):2111–24. [Google Scholar]

8. He W, Golla M, Padhi R, Ofek J, Dürmuth M, Fernandes E, et al. Rethinking access control and authentication for the home Internet of things (IoT). In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018. p. 255–72. [Google Scholar]

9. Fernandes E, Jung J, Prakash A. Security analysis of emerging smart home applications. In: 2016 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2016 May 22–26; San Jose, CA, USA. IEEE; 2016. p. 636–54. doi:10.1109/SP.2016.44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Fernandes E, Rahmati A, Jung J, Prakash A. Decentralized action integrity for trigger-action IoT platforms. In: Proceedings 2018 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; Virginia: The Internet Society; 2018. p. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

11. Yuan B, Jia Y, Xing L, Zhao D, Wang XF, Zhang Y. Shattered chain of trust: understanding security risks in cross-cloud IoT access delegation. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2020. p. 1183–200. [Google Scholar]

12. Celik ZB, Babun L, Sikder AK, Aksu H, Tan G, McDaniel P. Sensitive information tracking in commodity IoT. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018. p. 1687–704. [Google Scholar]

13. Yuan X, Chen Y, Zhao Y, Long Y, Liu X, Chen K, et al. Commandersong: a systematic approach for practical adversarial voice recognition. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018. p. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

14. Yan QB, Liu KH, Zhou Q, Guo H, Zhang N. SurfingAttack: interactive hidden attack on voice assistants using ultrasonic guided waves. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; Virginia, San Diego, CA, USA: The Internet Society; 2020. p. 1–18. [Google Scholar]

15. Bastys I, Balliu M, Sabelfeld A. If this then what?: controlling flows in IoT apps. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Toronto, ON, Canada: ACM; 2018. p. 1102–19. doi:10.1145/3243734.3243841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chen T, Shangguan L, Li Z, Jamieson K. Metamorph: injecting inaudible commands into over-the-air voice controlled systems. In: Proceedings 2020 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2020. doi:10.14722/ndss.2020.23055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Tightiz L, Rashid N, Morteza AN. Implementing AI solutions for advanced cyber-attack detection in smart grid. Int J Energy Res. 2024;2024:6969383. [Google Scholar]

18. Zhou W, Jia Y, Yao Y, Zhu L, Guan L, Mao Y, et al. Discovering and understanding the security hazards in the interactions between IoT devices, mobile apps, and clouds on smart home platforms. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2019. p. 1133–50. [Google Scholar]

19. Chen J, Zuo C, Diao W, Dong S, Zhao Q, Sun M, et al. Your IoTs are (not) mine: on the remote binding between IoT devices and users. In: 2019 49th Annual IEEE/IFIP International Conference on Dependable Systems and Networks (DSN); 2019 Jun 24–27; Portland, OR, USA. IEEE; 2019. p. 222–33. doi:10.1109/DSN.2019.00034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Ronen E, Shamir A, Weingarten AO, O’Flynn C. IoT goes nuclear: creating a ZigBee chain reaction. In: IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2017 May 22–26; San Jose, CA, USA. IEEE; 2017. p. 195–212. doi:10.1109/SP.2017.14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Jia Y, Xing L, Mao Y, Zhao D, Wang X, Zhao S, et al. Burglars’ IoT paradise: understanding and mitigating security risks of general messaging protocols on IoT clouds. In: 2020 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2020 May 18–21; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 465–81. doi:10.1109/sp40000.2020.00051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cao Y, Zhang Y, Lu R, Luan TH. Ghost-in-the-wireless: energy depletion attack on ZigBee. IEEE Internet Things J. 2014:373–86. [Google Scholar]

23. Almakhdhub NS, Clements AA, Bagchi S, Payer M. muRAI: securing embedded systems with return address integrity. In: Proceedings 2020 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2020. doi:10.14722/ndss.2020.24016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Ding W, Hu H. On the safety of IoT device physical interaction control. In: Proceedings of the 2018 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Toronto, ON, Canada: ACM; 2018. p. 832–46. doi:10.1145/3243734.3243865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Subramanyan P, Malik S, Khattri H, Maiti A, Fung J. Verifying information flow properties of firmware using symbolic execution. In: Proceedings of the 2016 Design, Automation & Test in Europe Conference & Exhibition (DATE); 2016 Mar 14–18; Research Publishing Services; 2016. p. 337–42. doi:10.3850/9783981537079_0793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hernandez G, Fowze F, Tian DJ, Yavuz T, Butler KRB. FirmUSB: vetting USB device firmware using domain informed symbolic execution. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Dallas, TX, USA. ACM; 2017. p. 2245–62. doi:10.1145/3133956.3134050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Ul Haq S, Singh Y, Sharma A, Gupta R, Gupta D. A survey on IoT & embedded device firmware security: architecture, extraction techniques, and vulnerability analysis frameworks. Discov Internet Things. 2023;3(1):17. doi:10.1007/s43926-023-00045-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Carlini N, Mishra P, Vaidya T, Zhang Y, Sherr M, Shields C, et al. Hidden voice commands. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2016. p. 513–30. [Google Scholar]

29. Zhang G, Yan C, Ji X, Zhang T, Zhang T, Xu W. DolphinAttack: inaudible voice commands. In: Proceedings of the 2017 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Dallas, TX, USA: ACM; 2017. p. 103–17. doi:10.1145/3133956.3134052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Celik ZB, McDaniel P, Tan G. Soteria: automated IoT safety and security analysis. In: USENIX Annual Technical Conference; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018. p. 147–58. [Google Scholar]

31. Celik ZB, Tan G, McDaniel P. IoTGuard: dynamic enforcement of security and safety policy in commodity IoT. In: Proceedings 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2019. doi:10.14722/ndss.2019.23326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Roy N, Shen S, Hassanieh H, Choudhury RR. Inaudible voice commands: the long-range attack and defense. In: USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018. p. 547–60. [Google Scholar]

33. Zhang N, Mi X, Feng X, Wang X, Tian Y, Qian F. Dangerous skills: understanding and mitigating security risks of voice-controlled third-party functions on virtual personal assistant systems. In: 2019 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2019 May 19–23; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2019. p. 1381–96. doi:10.1109/sp.2019.00016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kumar D, Paccagnella R, Murley P, Hennenfent E, Mason J, Bates A, et al. Skill squatting attacks on Amazon Alexa. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018, p. 33–47. [Google Scholar]

35. Soltan S, Mittal P, Poor HV. BlackIoT: IoT botnet of high-wattage devices can disrupt the power grid. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2018. p. 15–32. [Google Scholar]

36. Huang B, Cardenas AA, Baldick R. Not everything is dark and gloomy: power grid protections against IoT demand attacks. In: Proceedings of the 28th USENIX Conference on Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2019. p. 1115–32. [Google Scholar]

37. Wang Q, Datta P, Yang W, Liu S, Bates A, Gunter CA. Charting the attack surface of trigger-action IoT platforms. In: Proceedings of the 2019 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; London, UK: ACM Press; 2019. p. 1439–53. [Google Scholar]

38. Wang Q, Hassan WU, Bates A, Gunter C. Fear and logging in the Internet of Things. In: Proceedings of the 2018 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; Virginia: The Internet Society; 2018. p. 1–16. [Google Scholar]

39. Zhu Y, Xiao Z, Chen Y, Li Z, Liu M, Zhao BY, et al. Et tu Alexa? when commodity WiFi devices turn into adversarial motion sensors. In: Proceedings 2020 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2020. doi:10.14722/ndss.2020.23053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Lopez-Martin M, Carro B, Sanchez-Esguevillas A, Lloret J. Network traffic classifier with convolutional and recurrent neural networks for Internet of Things. IEEE Access. 2017;5:18042–50. doi:10.1109/ACCESS.2017.2747560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Cao X, Shila DM, Cheng Y, Yang Z, Zhou Y, Chen J. Ghost-in-ZigBee: energy depletion attack on ZigBee-based wireless networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2016;3(5):816–29. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2016.2516102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Fawaz K, Kim K-H, Shin KG. Protecting privacy of BLE device users. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2016. p. 1205–21. [Google Scholar]

43. Antonioli D, Tippenhauer NO, Rasmussen K. BIAS: bluetooth impersonation AttackS. In: IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2020 May 18–21; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 549–62. doi:10.1109/sp40000.2020.00093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Sethi M, Peltonen A, Aura T. Misbinding attacks on secure device pairing and bootstrapping. In: Proceedings of the 2019 ACM Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Auckland, New Zealand: ACM; 2019. p. 453–64. doi:10.1145/3321705.3329813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. OConnor TJ, Enck W, Reaves B. Blinded and confused: uncovering systemic flaws in device telemetry for smart-home Internet of Things. In: Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks; Miami, Florida: ACM; 2019. p. 140–50. doi:10.1145/3317549.3319724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wen H, Chen QA, Lin Z. Plug-N-Pwned: comprehensive vulnerability analysis of OBD-II dongles as a new over-the-air attack surface in automotive IoT. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2020. p. 949–65. [Google Scholar]

47. Sivanathan A, Gharakheili HH, Loi F, Radford A, Wijenayake C, Vishwanath A, et al. Classifying IoT devices in smart environments using network traffic characteristics. IEEE Trans Mobile Comput. 2019;18(8):1745–59. doi:10.1109/tmc.2018.2866249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wood D, Apthorpe N, Feamster N. Cleartext data transmissions in consumer IoT medical devices. In: Proceedings of the 2017 Workshop on Internet of Things Security and Privacy; Dallas, TX, USA: ACM Press; 2017. p. 7–12. [Google Scholar]

49. Acar A, Fereidooni H, Abera T, Sikder AK, Miettinen M, Aksu H, et al. Peek-a-Boo: I see your smart home activities, even encrypted!. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks; Linz, Austria: ACM Press; 2020. p. 207–18. [Google Scholar]

50. Trimananda R, Varmarken J, Markopoulou A, Demsky B. Packet-level signatures for smart home devices. In: Proceedings of the 2020 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; Virginia: The Internet Society; 2020. [Google Scholar]

51. Let W, Li S, Zhang H, Xu M, Zheng J, Zhang Y. SkillDetective: automated policy-violation detection of voice-apps. In: Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 22); Boston, MA, USA; 2022. p. 1223–40. [Google Scholar]

52. Schönherr L, Eisenhofer T, Holz T, Kolossa D, Rieck K. Unacceptable, where is my privacy? Exploring Accidental Triggers of Smart Speakers. arXiv:2008.00508. 2020. [Google Scholar]

53. Young J, Liao S, Cheng L, Hu H, Deng H. SkillDetective: automated policy-violation detection of voice assistant applications in the wild. In: Proceedings of the 31st USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security ’22); Boston, MA, USA; 2022. [Google Scholar]

54. Zhang Y, Xu L, Mendoza A, Yang G, Chinprutthiwong P, Gu G. Life after speech recognition: fuzzing semantic misinterpretation for voice assistant applications. In: Proceedings 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2019. doi:10.14722/ndss.2019.23525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Zhou J, Du Y, Shen Z, Ma L, Criswell J, Walls RJ. Silhouette: efficient protected shadow stacks for embedded systems. In: USENIX Security Symposium. Berkeley: USENIX Association; 2020. p. 1219–36. [Google Scholar]

56. Redini N, Machiry A, Wang R, Spensky C, Continella A, Shoshitaishvili Y, et al. Karonte: detecting insecure multi-binary interactions in embedded firmware. In: IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2020 May 18–21; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2020. p. 1544–61. doi:10.1109/sp40000.2020.00036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Yao Y, Zhou W, Jia Y, Zhu L, Liu P, Zhang Y. Identifying privilege separation vulnerabilities in IoT firmware with symbolic execution. In: European Symposium on Research in Computer Security; Berlin: Springer; 2019. p. 638–57. [Google Scholar]

58. Muller J, Mladenov V, Somorovsky J, Schwenk J. SoK: exploiting network printers. In: 2017 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2017 May 22–26; San Jose, CA, USA. IEEE; 2017. p. 213–30. doi:10.1109/sp.2017.47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Eschweiler S, Yakdan K, Gerhards-Padilla E. discovRE: efficient cross-architecture identification of bugs in binary code. In: Proceedings 2016 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA. Internet Society; 2016. doi:10.14722/ndss.2016.23185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Feng Q, Zhou R, Xu C, Cheng Y, Testa B, Yin H. Scalable graph-based bug search for firmware images. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Vienna, Austria: ACM; 2016. p. 480–91. doi:10.1145/2976749.2978370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Jia YJ, Chen QA, Wang S, Rahmati A, Fernandes E, Mao ZM, et al. ContexIoT: towards providing contextual integrity to appified IoT platforms. In: Proceedings 2017 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2017. doi:10.14722/ndss.2017.23051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Tian Y, Zhang N, Lin YH, Wang X, Ur B, Guo X, et al. SmartAuth: user-centered authorization for the internet of things. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2017. p. 361–78. [Google Scholar]

63. Uppuluri S, Lakshmeeswari G. Review of security and privacy-based IoT smart home access control devices. Wirel Pers Commun. 2024;137(3):1601–40. doi:10.1007/s11277-024-11405-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Ameer S, Praharaj L, Sandhu R, Bhatt S, Gupta M. ZTA-IoT: a novel architecture for zero-trust in IoT systems and an ensuing usage control model. ACM Trans Priv Secur. 2024;27(3):1–36. doi:10.1145/3671147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

65. Pattnaik N, Li S, Nurse JRC. A survey of user perspectives on security and privacy in a home networking environment. ACM Comput Surv. 2023;55(9):1–38. doi:10.1145/3558095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Wang W, Cicala F, Hussain SR, Bertino E, Li N. Analyzing the attack landscape of Zigbee-enabled IoT systems and reinstating users' privacy. In: Proceedings of the 13th ACM Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks; Linz, Austria: ACM; 2020. p. 133–43. doi:10.1145/3395351.3399349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Pirayesh J, Giaretta A, Conti M, Keshavarzi P. A PLS-HECC-based device authentication and key agreement scheme for smart home networks. Comput Netw. 2022;216:109077. doi:10.1016/j.comnet.2022.109077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

68. Kumar S, Hu Y, Andersen MP, Popa RA, Culler D. E JEDI: many-to-many end-to-end encryption and key delegation for IoT. In: USENIX Security Symposium; Berkeley, CA, USA: USENIX Association; 2019. p. 1519–36. [Google Scholar]

69. Xi W, Qian C, Han J, Zhao K, Zhong S, Li XY, et al. Instant and robust authentication and key agreement among mobile devices. In: Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Vienna, Austria: ACM Press; 2016. p. 616–27. [Google Scholar]

70. Farrukh H, Ozmen MO, Kerem Ors F, Celik ZB. One key to rule them all: secure group pairing for heterogeneous IoT devices. In: 2023 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2023 May 21–25; San Francisco, CA, USA: IEEE; 2023. p. 3026–42. doi:10.1109/SP46215.2023.10179369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

71. Li X, Zeng Q, Luo L, Luo T. T2Pair: secure and usable pairing for heterogeneous IoT devices. In: Proceedings of the 2020 ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security; Virtual Event, USA: ACM; 2020. p. 309–23. doi:10.1145/3372297.3417286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. Apthorpe N, Huang DY, Reisman D, Narayanan A, Feamster N. Keeping the smart home private with smart(er) IoT traffic shaping. Proc Priv Enhancing Technol. 2019;2019(3):128–48. doi:10.2478/popets-2019-0040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. OConnor TJ, Mohamed R, Miettinen M, Enck W, Reaves B, Sadeghi AR. HomeSnitch: behavior transparency and control for smart home IoT devices. In: Proceedings of the 12th Conference on Security and Privacy in Wireless and Mobile Networks; Miami, Florida: ACM; 2019. p. 128–38. doi:10.1145/3317549.3323409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Kim CH, Kim T, Choi H, Gu Z, Lee B, Zhang X, et al. Securing real-time microcontroller systems through customized memory view switching. In: Proceedings 2018 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA, USA: Internet Society; 2018. doi:10.14722/ndss.2018.23107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Luo L, Zhang Y, White C, Keating B, Pearson B, Shao X, et al. On security of TrustZone-M-based IoT systems. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022;9(12):9683–99. doi:10.1109/jiot.2022.3144405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Hasan MK, Ghazal TM, Saeed RA, Pandey B, Gohel H, Eshmawi AA, et al. A review on security threats, vulnerabilities, and counter measures of 5G enabled Internet-of-Medical-Things. IET Commun. 2022;16(5):421–32. doi:10.1049/cmu2.12301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Sun Z, Feng B, Lu L, Jha S. OAT: attesting operation integrity of embedded devices. In: IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP); 2020 May 18–21; San Francisco, CA, USA. IEEE; 2020. p. 1433–49. doi:10.1109/sp40000.2020.00042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Abera T, Bahmani R, Brasser F, Ibrahim A, Sadeghi AR, Schunter M. DIAT: data integrity attestation for resilient collaboration of autonomous systems. In: Proceedings 2019 Network and Distributed System Security Symposium; San Diego, CA. Internet Society; 2019. doi:10.14722/ndss.2019.23420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Sun X, Fu J, Wei B, Li Z, Li Y, Wang N. A self-attentional ResNet-LightGBM model for IoT-enabled voice liveness detection. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023;10(9):8257–70. doi:10.1109/JIOT.2022.3230992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]