Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Mental health literacy in sub-Saharan Africa: A scoping review

1 Department of Psychology, College of Human Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, 0002, South Africa

2 Little Manhattan Lower East Village, Pretoria West, 0001, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Daniel Lesiba Letsoalo. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(1), 159-165. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065764

Received 20 March 2024; Accepted 03 August 2024; Issue published 30 April 2025

Abstract

There has been an increase in mental health problems in Sub-Saharan Africa. Considering this, it is critical to track the region’s level of mental health literacy (MHL) to identify key mental health priorities and to direct the most effective interventions. The purpose of this study was to review the existing literature on MHL in sub-Saharan Africa. EBSCOhost (inclusive of Academic Search Ultimate, MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, APA Psych Articles, and Global Health), CINAHL with full text, Wiley Online Library, Taylor and Francis Online Journals and Google Scholar databases were searched to retrieve relevant articles. The study only considered original full-text, peer-reviewed, English-written research on MHL carried out in sub-Saharan Africa and published between 2015 and 2023. Scoping review steps by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) were followed. Grey literature, review studies, and review protocols were excluded. The data was analysed using reflexive thematic analysis (RTA). The results showed that MHL varies within the region, making it difficult to determine the exact state. Furthermore, the study uncovered factors that contribute to both poor and better MHL in the region. Poor MHL was linked to residing in the township and being male. Better MHL was associated with higher education levels, being female, urban residence, and having a history of mental illness, among other factors. The study findings provide evidence-based recommendations for regional, policy, or legislative-led interventions and prioritisations of mental health education programs and public mental health campaigns to increase awareness of mental health.Keywords

Mental health is a major global public health concern with significant economic costs, as experts estimate it to cost the world economy 2.5 trillion dollars, with a projected increase to 6 trillion in the year 2030 (World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa, 2023; World Health Organisation, n.d.). Within the African and/or sub-Saharan context, the effects of mental health conditions are even more pronounced due to severe underfunding, competing development and health priorities, as well as poor health infrastructure (World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa, 2023). Across the African region, an estimated 116 million people live with mental health conditions (World Health Organisation, n.d.). This number is significant considering that, globally, it was estimated that approximately 970 million people were living with mental disorders in 2019.

According to Dybdahl and Lien (2018), WHO considers mental health integral to attaining sustainable development goals (SDGs). However, people with mental health conditions in sub-Saharan Africa are discriminated against and their human rights violated due to widespread gaps in care and access (World Health Organisation, n.d.). Increasing MHL would be part of the solution (World Health Organisation, n.d.).

Mental health literacy. Mental health literacy (MHL) refers to “knowledge and beliefs about mental disorders which aid in their recognition, management and/or prevention” (Carvalho et al., 2022; Jorm et al., 1997; Sampaio et al., 2022). It comprises: (a) the ability to recognise specific disorders or types of psychological distress; (b) knowledge and beliefs about risk factors and causes; (c) knowledge and beliefs about self-help interventions; (d) knowledge and beliefs about professional help available; (e) attitudes that facilitate recognition and appropriate help-seeking; and (f) knowledge of how to seek mental health information (Carvalho et al., 2022; Jorm, 2000; Sampaio et al., 2022). Tambling et al. (2021) described suboptimum MHL as a barrier to mental health awareness, seeking help, treatment needs, and utilisation of mental health services. Individuals and communities with lower MHL are at risk of mental health distress (Coles et al., 2016; Madlala et al., 2022).

The sub-Saharan context. Overall, sub-Saharan African populations would have lower MHL (Aluh et al., 2018; Atilola, 2014; Chinene et al., 2023; Marangu et al., 2021; Spedding et al., 2018). They also hold to cultural beliefs for their conceptualisation, diagnosis, and treatment of mental health disorders (MHDs). For instance, in one of the Ugandan tribes (the Baganda), psychosis is conceptualised as an illness that is a consequence of not appeasing the ancestors (Okello & Musisi, 2006). Other studies have reported that some MHDs are believed to be caused by spiritual forces and witchcraft (Galvin et al., 2023; Okafor et al., 2022; Subu et al., 2022). Within the same context, in one study conducted in Ethiopia exploring MHL, the participants were able to identify only visible psychotic symptoms and not covert psychotic symptoms (Deribew & Tamirat, 2005), meaning that they struggled to identify conditions such as depression as it is more covert. Kabir et al. (2004) reported similar results in Nigeria.

Goal of the study. The current scoping review aimed to synthesize MHL findings in the sub-Saharan region and explore their implications for the region’s recognition of MHDs, mental health service utilization, and alignment with SDG aspirations. The study addressed the following question:

• What is the emerging evidence on the state of mental health literacy in sub-Saharan Africa?

This scoping review followed the steps by Arksey and O’Malley (2005): (a) identifying the research question; (b) identifying relevant studies; (c) study selection (d) charting the data; (e) collating, summarising, and reporting results; and (f) consulting, which is optional. A scoping review was appropriate for this study because it allowed for a comprehensive examination of the existing literature on MHL in sub-Saharan Africa, considering the diverse contexts within the region. This made it possible to capture the range of definitions, approaches, and outcomes associated with MHL in the different regions.

The studies included in the review investigated MHL in countries within the sub-Saharan region. The following databases were consulted for the identification and retrieval of relevant studies: EBSCOhost (inclusive of Academic Search Ultimate, MEDLINE, APA PsycINFO, APA Psych Articles, and Global Health), CINAHL with full text, Wiley Online Library and Taylor and Francis Online Journals. Through a freehand search, the researchers crosschecked the retrieved studies via Google and Google Scholar. All the authors decided upon the Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) and Boolean search term combinations and/or strings and the databases to consult.

The following MeSH term was used and/or adapted for all the databases consulted: “mental health literacy”. The Boolean search was performed through the use of a combination of terms or truncations, which were: mental health literacy OR mental health awareness OR mental health education OR mental health knowledge AND Africa OR sub-Saharan Africa OR sub-Sahara OR specific sub-Saharan country. Studies were screened for relevance and eligibility in line with the inclusion and exclusion criteria presented in Table 1 below.

Following the PRISMA-ScR flow chart adapted from Madonsela et al. (2023), the authors chose studies for relevance and eligibility based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. PRlSMA-ScR flow diagram for the scoping review process

Initially, the search of all selected databases identified 251 articles, and an additional 3 articles were identified through Google Scholar, totalling 254. Nine (9) duplicates were subsequently removed. The titles and abstracts of the remaining 245 articles were then screened, and 228 were excluded. Of the remaining 17 peer-reviewed full-text articles assessed for eligibility, 03 did not meet the inclusion criteria because of the wrong location or region, the other article was an adaptation of content validity, and the last one was a protocol for systematic review. Figure 1 provides a step-by-step description of the review process. Following a robust process in line with the PRISMA-ScR flow diagram (see Figure 1), a total of 14 peer-reviewed full-text articles met the inclusion criteria. All 14 studies were published between 2015 and 2023—as the objective, of this review was to provide a synthesis of literature based on recent original studies as much as possible. Doing so, we believed, would give us a better estimate of the state of MHL in the region. Of the 14 studies included, 3 used a mixed methods research design, 8 were quantitative, 2 were qualitative and 1 was ethnography.

All the authors (DL, MV, AJ and JK) conducted data extraction independently. The authors entered the retrieved studies into an Excel sheet for management. All authors were responsible for screening articles for eligibility. The authors resolved any disagreement that emerged through consensus.

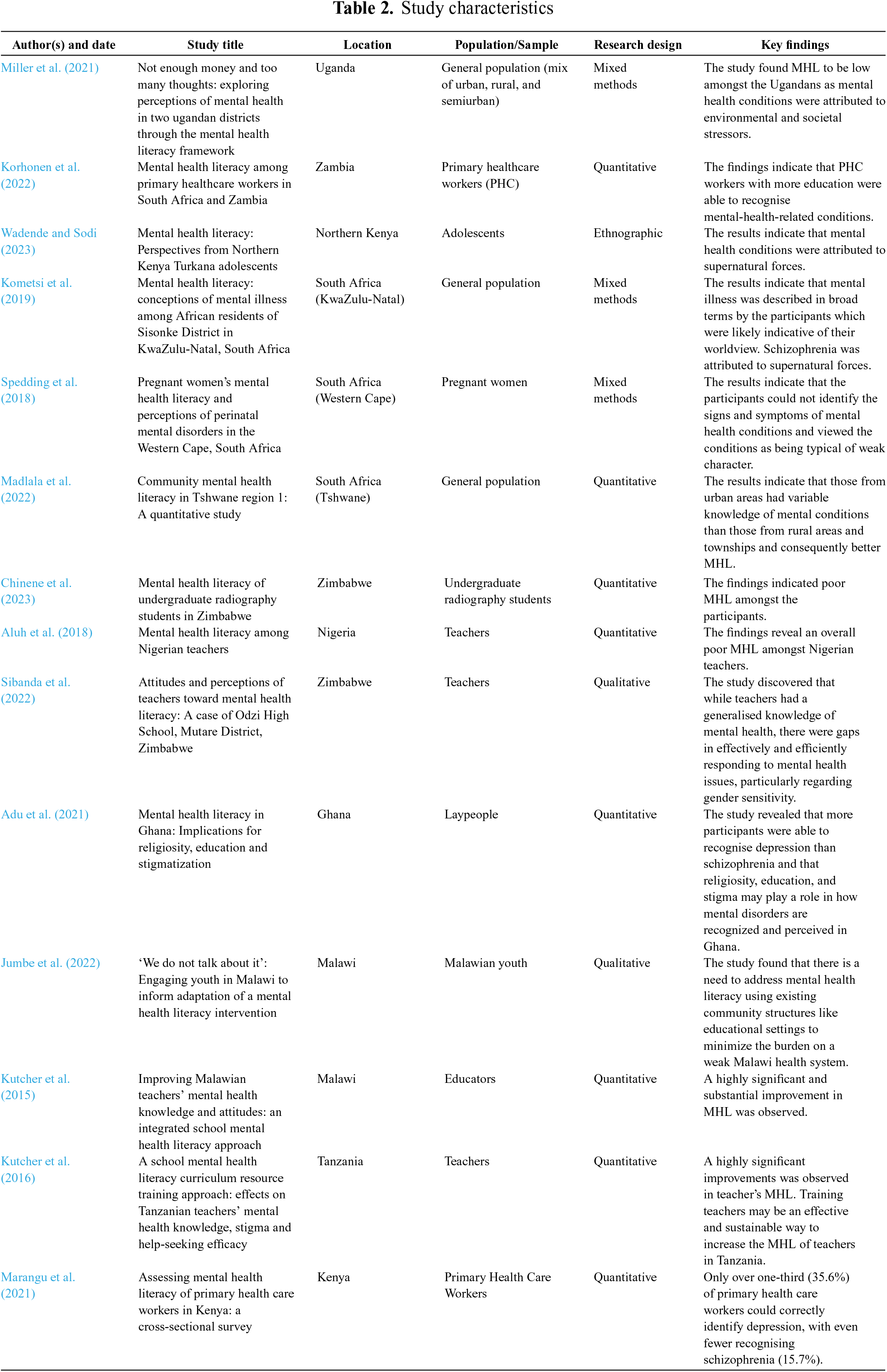

Following the studies review for eligibility, the reviewers charted the final articles on a table (Table 2). In accordance with the following characteristics: authors and year of publication, study title, country or location, research approach or design, population, and main findings.

Collating, summarising, and reporting of the results

Post-data extraction, screening and charting, all authors analysed, collated and synthesized the results using RTA (Braun & Clarke, 2021). Following the data analysis process, three themes and one subtheme were identified.

Following a thorough review and/or perusal of the selected articles by the review team and the subsequent reflexive analysis process following steps by Braun and Clarke (2021), three major themes and one subtheme emerged. The three themes were: identifying mental health disorders and cultural lenses, sociodemographic factors and MHL, and sources of help and intervention. The subtheme was: cultural and spiritual factors associated with the conceptualisation of schizophrenia.

Theme 1. Identifying mental health disorders and cultural lenses

Mental health disorder identification is low. For instance, Aluh et al. (2018) reported low MHL among secondary school teachers in southeast Nigeria. Similarly, Chinene et al. (2023) reported low MHL among undergraduate radiography students in Zimbabwe. Spedding et al. (2018) also reported low MHL among pregnant women receiving antenatal care in a primary healthcare facility in the Western Cape province of South Africa of which only 26% recognized well documented mental health disorders ascribing the conditions to “typical weak character”. Similar findings were reported by Marangu et al. (2021) in a Kenyan study, Adu et al. (2021) in a Ghanaian study, Sibanda et al. (2022) in a Zimbabwean study and Korhonen et al. (2022) in a study in South Africa and Zambia.

Cultural lenses. Sub-Saharan populations may prefer local terms for mental health disorders such as “Akiyalong” for depression, “Waarit/Ngikerep” for schizophrenia, and “Ngatameta naaronok” for anxiety. For example, Wadende and Sodi (2023) found in their study that for the schizophrenia vignette, the participants attributed the individual’s symptoms to curses, implying that it is the work of a supernatural force. Similarly, in Kometsi et al. (2019), it was found that among the three conditions investigated through vignettes (depression, alcohol dependency and schizophrenia), schizophrenia was the only condition attributed to supernatural causes and the descriptions used were bewitchment and “ukuthwasa” (being called and/or chosen to become a traditional healer). In the study by Miller et al. (2021), altered appearance and behaviour were perceived by participants as major signs of mental health problems. Along the same lines, a positive correlation between higher levels of formal education and better MHL was observed by Kutcher et al. (2016).

Theme 2. Sociodemographic factors and MHL

Participants from the township displayed poor MHL (Madlala et al., 2022; Sibanda et al., 2022). They were also more likely to attribute MHL to curses, guilt, and family conflict (Wadende & Sodi, 2023).

Similarly, Chinene et al. (2023) reported poor MHL among male participants who were less knowledgeable about familial, social, environmental and biological aetiological factors. Being female is associated with better chances of being able to recognise certain mental disorders, as well as residing in an urban area and having a history of mental illness. Miller et al. (2021) attributed poor MHL to interpersonal factors such as poverty, intimate partner violence (IPV) and substance abuse, rather than intrapersonal ones. Life stress was a primary cause of MHDs. Additionally, Adu et al. (2021) reported an association between religiosity and mental health disorders. Furthermore, stigma surrounding mental health, a lack of resources and support systems, cultural beliefs, being from the township, curses, guilt, family conflict, hunger, sexual assault, communicable diseases, being male, less knowledgeable about familial, social, environmental and biological factors, poverty, IPV, substance abuse, stress and religiosity were reported to be sociodemographic factors associated with poor MHL (Chinene et al., 2023; Wadende & Sodi, 2023 ). Comparably, Madlala et al. (2022), also revealed that urban participants in their study, as compared to their township counterparts, were better at recognising MDD as a mental illness.

Subtheme 2.1: Cultural and spiritual factors associated with the conceptualisation of Schizophrenia

A noteworthy finding from the review of the studies was the consistent association of schizophrenia with supernatural forces. Despite limited supporting evidence from reviewed studies, we (as authors) contend that schizophrenia warrants attention, especially considering its interpretation through indigenous cultural lenses and local disease theories within many African cultures.

Theme 3: Sources of help and intervention

Regarding seeking help, the participants in the reviewed studies suggested various sources where individuals who suffer from mental illness can acquire assistance. For instance, Wadende and Sodi (2023) reported, the participants to suggest family members, friends, teachers, and community leaders as sources of help rather than medical services. The participants also believed in the power of meditation and one’s willpower to overcome difficulties. On the contrary, in Madlala et al. (2022), for all the disorders, MDD, GAD and schizophrenia, most of the participants chose professional help as the best form of intervention (counselling, psychotherapy and medication). On the same note, in Aluh et al. (2018), counsellors were the most recommended, followed by teachers and family. Similarly, in Spedding et al. (2018), the participants expressed confidence in counsellors or social workers as sources of help. Of significance to note in the study, however, was that the participants also expressed the same level of confidence in seeking religious/spiritual advisor’s help. Considering the context, it is evident that Africans utilize diverse support systems, resulting in varied help and intervention sources.

Implications for research and practice

Based on the reviewed studies, it is evident that MHL in sub-Saharan Africa is variable, regarding cause, recognition, treatment, and attitude, consequently leading to discrimination and stigmatisation of those with mental conditions. Moreover, there are societal, environmental, and traditional gender norms as well as socioeconomic disparities in MHL among populations. The attribution of MHDs to supernatural forces also seems to be a common theme in sub-Saharan Africa. In Wadende and Sodi (2023), the participants described people with schizophrenia as being cursed. This implies that some form of external force inflicted harm on these individuals. Kometsi et al. (2019) also came to a similar realisation, as they found that most of the participants in their study attributed schizophrenia to supernatural forces such as bewitchment. Furthermore, individuals with more education, exposure, experience, and training had higher MHL. The opposite was true for those with less education, less exposure, less experience, and less training.

It is interesting to note that, in all the studies participants rarely referred to medical intervention as a source of help. It can be argued that the overall MHL variability may influence the variability of the sources of help observed in the region.

Strengths, limitations, and future directions

Each study has strengths and limitations, and this review is no different. The strength of the review is that it followed Arksey and O’Malley (2005) methodological framework for conducting a scoping review. The findings contribute to the field of mental health and the scant research available on MHL in the sub-Saharan region and, as such, offer valuable insight into the recent state of MHL in the region which can help inform prioritisation, legislation and/or policy development or amendments. The limitation of this review is that the studies were retrieved through specific databases, and it is possible that other studies that could have enhanced or offered a different perspective were excluded. Furthermore, this review focused on sub-Saharan Africa, as such the results should be interpreted within the parameters of the region and not be generalised to other regions. Additionally, studies written in other languages and grey literature were excluded. As such, the conclusions of this review, although valuable and insightful, are based on few studies and should therefore be considered tentative and interpreted with this in mind. Future reviews should seek to address these limitations utilizing a systematic review.

The results indicate that MHL and sources of help and intervention for those with mental health challenges are variable within the region. The review also brought forth factors which contribute to both poor and better mental health in the region. People in the region may be using local terms to describe and explain the causes, progression, and treatment of mental health challenges. The latter was evidenced by the observation that we (the authors) made regarding the way participants in some of the studies responded, whereby they provided general rather than specific names or descriptors for MHDs. In this regard, the results are an accurate representation of the participants’ mental health knowledge and theory of disease causality in sub-Saharan Africa.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Daniel Lesiba Letsoalo, Anastasia Julia Ngobe, Joy Katlego Hlokwe, Mahlatsi Venolia Semenya; data collection: Daniel Lesiba Letsoalo, Anastasia Julia Ngobe, Joy Katlego Hlokwe; analysis and interpretation of results: Daniel Lesiba Letsoalo, Anastasia Julia Ngobe, Joy Katlego Hlokwe, Mahlatsi Venolia Semenya; draft manuscript preparation: Mahlatsi Venolia Semenya. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Adu, P., Jurcik, T., & Grigoryev, D. (2021). Mental health literacy in Ghana: Implications for religiosity, education and stigmatization. Transcultural Psychiatry, 58(4), 516–531. https://doi.org/10.1177/13634615211022177 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Aluh, D. O., Dim, O. F., & Anene-Okeke, C. G. (2018). Mental health literacy among Nigerian teachers. Asia-Pacific Psychiatry, 10(4), e12329. https://doi.org/10.1111/appy.12329 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Atilola, O. (2014). Level of community mental health literacy in sub-Saharan Africa: Current studies are limited in number, scope, spread, and cognizance of cultural nuances. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 69(2), 93–101. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2014.947319 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic Analysis. London, UK: SAGE. http://books.google.ie/books?id=mToqEAAAQBAJ&printsec=frontcover&dq=Thematic+Analysis&hl=&cd=1&source=gbs_api. [Google Scholar]

Carvalho, D., Sequeira, C., Querido, A., Tomás, C., Morgado, T., et al. (2022). Positive mental health literacy: A concept analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 877611. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.877611 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chinene, B., Mpezeni, L., & Mudadi, L. (2023). Mental health literacy of undergraduate radiography students in Zimbabwe. Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences, 54(4), 662–669. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmir.2023.08.005 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Coles, M. E., Ravid, A., Gibb, B., George-Denn, D., Bronstein, L. R., et al. (2016). Adolescent mental health literacy: Young people’s knowledge of depression and social anxiety disorder. Journal of Adolescent Health, 58(1), 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.09.017 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Deribew, A., & Tamirat, Y. S. (2005). How are mental health problems perceived by a community in Agaro town? Ethiopian Journal of Health Development, 19(2), 153–159. https://doi.org/10.4314/ejhd.v19i2.9985 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dybdahl, R, & Lien, L. (2018). Mental health is an integral part of the sustainable development goals. Preventive Medicine and Community Health, 1(1). https://doi.org/10.15761/pmch.1000104 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Galvin, M., Chiwaye, L., & Moolla, A. (2023). Perceptions of causes and treatment of mental illness among traditional health practitioners in Johannesburg, South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 53(3), 403–415. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463231186264 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jorm, A. F. (2000). Mental health literacy. British Journal of Psychiatry, 177(5), 396–401. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.177.5.396 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jorm A. F., Korten A. E., Jacomb P. A., Christensen H., Rodgers B., et al. (1997). Mental health literacy: A survey of the public’s ability to recognise mental disorders and their beliefs about the effectiveness of treatment. Medical Journal of Australia, 166(4), 182–186. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1997.tb140071.x [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jumbe S., Nyali J., Simbeye M., Zakeyu N., Motshewa G.et al. (2022). We do not talk about it’: Engaging youth in Malawi to inform adaptation of a mental health literacy intervention. PLoS One, 17(3), e0265530. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0265530 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kabir, M., Iliyasu, Z., Abubakar, I. S., & Aliyu, M. H. (2004). Perception and beliefs about mental illness among adults in Karfi village, northern Nigeria. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 4(1), 3. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-4-3 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kafor, I. P., Oyewale, D. V., Ohazurike, C., & Ogunyemi, A. O. (2022). Role of traditional beliefs in the knowledge and perceptions of mental health and illness amongst rural-dwelling women in western Nigeria. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 14(1), a3547. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v14i1.3547 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kometsi, M. J., Mkhize, N. J., & Pillay, A. L. (2019). Mental health literacy: Conceptions of mental illness among African residents of Sisonke District in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology, 50(3), 347–358. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246319891635 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Korhonen J., Axelin A., Stein D. J., Seedat S., Mwape L., et al. (2022). Mental health literacy among primary healthcare workers in South Africa and Zambia. Brain and Behavior, 12(12), e2807. https://doi.org/10.1002/brb3.2807 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kutcher S., Gilberds H., Morgan C., Greene R., Hamwaka K., et al. (2015). Improving Malawian teachers’ mental health knowledge and attitudes: An integrated school mental health literacy approach. Global Mental Health, 2, e1. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2014.8 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kutcher S., Wei Y., Gilberds H., Ubuguyu O., Njau T., et al. (2016). A school mental health literacy curriculum resource training approach: Effects on Tanzanian teachers’ mental health knowledge, stigma and help-seeking efficacy. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 10(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-016-0082-6 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Madlala, D., Joubert, P. M., & Masenge, A. (2022). Community mental health literacy in Tshwane region 1: A quantitative study. South African Journal of Psychiatry, 28(4), a1661. https://doi.org/10.4102/sajpsychiatry.v28i0.1661 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Madonsela, S., Ware, L. J., Scott, M., & Watermeyer, J. (2023). The development and use of adolescent mobile mental health (m-health) interventions in low- and middle-income countries: A scoping review. South African Journal of Psychology, 53(4), 471–483. https://doi.org/10.1177/00812463231186260 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marangu E., Mansouri F., Sands N., Ndetei D., Muriithi P., et al. (2021). Assessing mental health literacy of primary health care workers in Kenya: A cross-sectional survey. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15(1), 55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00481-z [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Miller A. P., Ziegel L., Mugamba S., Kyasanku E., Wagman J. A., et al. (2021). Not enough money and too many thoughts: Exploring perceptions of mental health in two Ugandan districts through the mental health literacy framework. Qualitative Health Research, 31(5), 967–982. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732320986164 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Okello, E., & Musisi, S. (2006). Depression as a clan illness (eByekikaAn indigenous model of psychotic depression among the Baganda of Uganda. https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:80319548. [Google Scholar]

Sampaio, F., Gonçalves, P., & Sequeira, C. (2022). Mental health literacy: It is now time to put knowledge into practice. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7030. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127030 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sibanda, T., Sifelani, I., Kwembeya, M., Matsikure, M., & Songo, S. (2022). Attitudes and perceptions of teachers toward mental health literacy: A case of Odzi High School, Mutare District. Zimbabwe Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1003115. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1003115 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Spedding, M. F., Stein, D. J., Naledi, T., & Sorsdahl, K. (2018). Pregnant women’s mental health literacy and perceptions of perinatal mental disorders in the Western Cape, South Africa. Mental Health & Prevention, 11(5), 16–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhp.2018.05.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Subu M. A., Holmes D., Arumugam A., Al-Yateem N., Maria Dias J., et al. (2022). Traditional, religious, and cultural perspectives on mental illness: A qualitative study on causal beliefs and treatment use. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 17(1), 2123090. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2022.2123090 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tambling, R. R., D’Aniello, C., & Russell, B. S. (2021). Mental health literacy: A critical target for narrowing racial disparities in behavioral health. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 21(3), 1867–1881. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-021-00694-w [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wadende, P., & Sodi, T. (2023). Mental health literacy: Perspectives from Northern Kenya Turkana adolescents. Cambridge Prisms: Global Mental Health, 10, 65. https://doi.org/10.1017/gmh.2023.25 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

World Health Organisation Regional Office for Africa (2023). World Mental Health Day 2022. Retrieved from: https://www.afro.who.int/regional-director/speeches-messages/world-mental-health-day-2022. [Google Scholar]

World Health Organization. (n.d.). Mental health. Retrieved from: https://www.who.int/health-topics/mental-health#tab=tab_3. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools