Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

How does perceived human-computer interaction affect employee helping behavior?

1 School of Management, Wuhan Polytechnic University, Wuhan, 430024, China

2 School of Management, Lanzhou University, Lanzhou, 730000, China

* Corresponding Author: Xin Liu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 257-263. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065782

Received 19 July 2024; Accepted 04 March 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study examined how perceived human-computer interaction (HCI) is related to employees’ helping behaviors with role breadth self-efficacy and digital fluency. An online scenario experiment (study 1; female = 61.3%; mean age = 30.79 years; bachelor’s degree = 68.7%) and a questionnaire survey (study 2; male = 44.2%; younger than 30 years = 50.6%; bachelor’s degree = 61.5%) found that perceived HCI exerts a significant positive indirect effect on employee helping behavior through improved role breadth self-efficacy. This positive indirect effect is stronger when employee digital fluency is high. Findings are consistent with social cognitive theory, which proposes that the relationship among environment, individual cognition, and behavior is mutually determined, and the influence of environment on individual behavior varies with individual characteristics. The findings imply a need for employer organizations to create favorable human-computer interaction environment for employees’ digital fluency to promote role breadth self-efficacy and helping behavior in the digital age.Keywords

The rapid development of digital technology has brought increasing work pressure and anxiety to employees (Zhao et al., 2023), which risks impacting employee helping behavior to be lower which may hurt their career development (Koopman et al., 2016; Lin et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2024; Zhang et al., 2020). At the same time. digital technology can enhance employees’ positive emotions and reduce work insecurity (Gao & Gao, 2024; Sun et al., 2024; Topcuoglu et al., 2023), although it may reduce employee person-to-person interactions for work-related quality of life. Digital technology has gradually permeated the employees’ daily activities in the workplace by the fact that. However, the human-digital technology interaction impact employees’ helping behavior requires further study to determine both the nature and direction of the impacts to explain when and how this new experience of interacting between employee and digital technology influences employees’ helping behavior.

Human computer interaction and employee helping behavior

Human-computer interaction (HCI) refers to the individual’s psychological understanding of the interactive communication mode and controllable degree in the process, by the user’s engagement with various virtual contents, commands, or functions on the computer (Wu, 2006). It is about the structure, process, and users’ perception of their interactions in the work environment (Liu & Shrum, 2002), and by perceptual, semantic, and behavioral dimensions (Sohn, 2011). These dimensions may explain their sense of control of the work space from perceived ease of use of the technology (Wu, 2006; Yang & Shen, 2017).

Analyzing how individuals experience a technology is more important than analyzing the technological process or the technical features themselves (Park & Yoo, 2020; Voorveld et al., 2011), and particularly in employment settings HCI can promote improved work performance and encourage innovative behavior (Huang & Zulkifli, 2023) but with a likely unintended consequence on employees’ helping behavior taking away from a sense of participatory teamwork. Helping behavior is an extra-role behaviors that extend beyond the formal job description (Shen & Benson, 2016), and may be enhanced among employees with high digital fluency (Li et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2020). Yet, this proposition remains untested.

Digital technology can help employees with work resources to complete tasks efficiently (Pitafi et al., 2018), and implement extra-role behavior collaboratively with colleagues (Li et al., 2022). It is associated with a sense of reciprocity and reward (Halbesleben & Wheeler, 2012), so that one obtain a more favorable work experience with helping behavior.

Role breadth self-efficacy(RBSE) as a mediator of perceived HCI and helping behavior relationship

RBSE refers to the positive perception of employees that they can finish a series of tasks with a wider range and greater motivation, even exceeding job requirements (Parker, 2000). Prior studies have shown that the perceived work environment can offer favorable support and explicit role information to employees, which consequently facilitates RBSE (Hao et al., 2017). Perceived HCI can easily give rise to RBSE through two cues.

The first clue is repeated success. Digital technology has provided individuals with the means to effectively communicate and foster mutually beneficial interpersonal relationships (Alsharo et al., 2017), compensating for employees’ deficiencies in knowledge management, information transmission, and interpersonal communication (Hovens, 2020). In this way, it is possible for employees to achieve innovation and performance outcome (Wang & Wang, 2012), which is conducive to stimulating RBSE. The second clue is the perception of HCI with organizational identification and trustworthiness (Breuer et al., 2019). With HCI, an employee’s ability to efficiently allocate energy and focus on achieving work objectives would be important.

Prior research found that employees who possess a high level of RBSE are likely to implement higher level of proactive behaviors (Beltrán-Martín et al., 2017; Parker, 1998). Because they have positive self-evaluation, which gives them the motivation to help enterprises and colleagues solve the problems (Ma et al., 2021; McAllister et al., 2007), and they believe that their behaviors can benefit others (Koopman et al., 2016). However, employees with low self-efficacy may refuse even if their colleagues ask for help because of their low self-efficacy and uncertainty regarding whether they will be able to solve the problem.

Employees acquire information from the external environment and construct their self-cognition and behavior in accordance with the external environment. When an individual interprets a certain external situation or itself, a certain motivation will be generated. RBSE is such a motivational variable generated by cognition, which can prompt an individual to display a certain behavior (Hwang et al., 2015). We propose that perceived HCI can indirectly affect employee helping behavior through employee RBSE.

The moderating role of digital fluency

Digital fluency means that create and reformulate information as well as use digital technologies properly (Wang et al., 2013). According to prior research (Li et al., 2018; Wei et al., 2020), digital fluency would moderate the relationship between perceived Human-Computer Interaction (HCI) and employees’ helping behavior.

Digital fluency has been considered an imperative set of skills and capabilities of successful individuals in the digital age (Wei et al., 2020). Employee with higher digital fluency not only involve knowledge about surfing the Internet but also involve the ability to source information, assesses the quality of the sourced information, and produces information to express oneself creatively and appropriately (Chou & Chiu, 2020; Wang et al., 2013). Moreover, employees with digital literacy are more able to fulfill their information needs (Li et al., 2018), encountering fewer psychological and technical barriers (Williams & Crittenden, 2012). In this way, employees who are characterized by higher digital fluency are more likely to obtain more effective resources to finish a series of tasks when they interact with digital technology, which is conducive to improving employees’ RBSE.

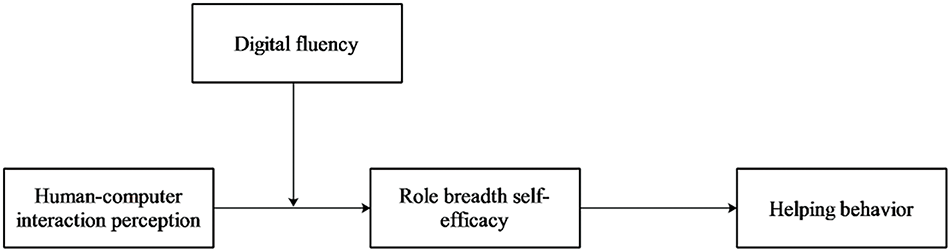

The current study employed a mixed-methods empirical approach to test a moderated mediation model. Specifically, we sought to determine if and how HCI is associated with employee helping behavior, controlling digital fluency. We proposed to test the following hypothesis (see also Figure 1):

Figure 1: Theoretical model

Hypothesis 1. Perceived HCI is associated with higher helping behavior.

Hypothesis 2. Perceived HCI is associated with higher RBSE.

Hypothesis 3. RBSE is associated with higher helping behavior.

Hypothesis 4. RBSE plays a mediating role between perceived HCI and helping behavior.

Hypothesis 5. Digital fluency moderates the positive relationship between perceived HCI and RBSE to be stronger with digital fluency.

Hypothesis 6. Digital fluency moderates the indirect effects of perceived HCI on helping behavior to be stronger.

First, we provided causal evidence that perceived HCI influences employees’ helping behavior from an online scenario experiment, that is study 1. We recruit participants on Credamo (an Online survey platform) and carry out study 1. Ethics approval was granted by the Bioethics Committee of Wuhan Polytechnic University. Subsequently, to further improve the external validity of study 1 and test the mediating role of RBSE and the moderating role of digital fluency, we conducted the questionnaire survey method in study 2. The data for study 2 were collected through Credamo, an online platform.

The participants consented to the study. After consenting, the employees were randomly assigned to an experimental situation (high perceived HCI VS low perceived HCI) and were required to carefully read the experimental manipulation material.

Participants were a convenience sample of 150 employees from manufacturing and service industries. In terms of gender, 58 men and 92 women; In terms of age, the mean age was 30.79 years (SD = 8.559); The average length of service was 7.35 years (SD = 7.110). In terms of education, the number of people with a bachelor’s degree is the largest (103), accounting for 68.7%; In terms of industry types, the number of participants engaged in manufacturing (49) and the service industry (31) was higher.

Finally, the participants were asked to report other variable information according to the experimental materials read above. Participants who complete the experiment will receive a cash reward.

To manipulate participants’ perceived HCI, we collected the process of employee interaction with the phone robot. These workflows, which were distilled after consulting with a sales team, represent a salesman typically needs to undertake when making a high volume of sales calls. Although the tasks chosen were not particularly advanced, they often occur during the process of working with a smart phone robot, and it was anticipated that they would present some challenges for staff. Then, we combined these materials with the scale of Gefen et al. (2003) to compile experimental materials.

All participants were instructed to imagine the following.

You are a telemarketer, your daily work is to contact customers by phone to sell products. However, in the process of traditional outbound calls, there are always problems of high labor costs and low conversion rates. For this reason, your company has introduced a smart phone robot, you need to use this robot to achieve sales performance by completing the specific workflow.

In the higher-HCI (lower-HCI) condition, participants read the following.

1) Recording professional speech. You can store multiple speech templates in the smart phone robot system (only one can be store at a time), and you have the flexibility to switch between call templates whenever needed (Switching call templates requires re-recording and importing). 2) Importing the customers’ phone number. You can import dialed numbers in batches by clicking (manually input numbers) and manage the imported numbers by category (cannot be classified). 3) Setting rule. Set the call time (cannot set the call time). 4) Performing tasks. You can monitor (not monitor) the outbound work of the phone robot, and you can stop calling and adjust the calling task at any time when you find an anomaly (you cannot stop and adjust the calling task). 5) Tracking of tasks. You follow up twice according to the customer intention level provided by the robot (The customer call information recorded by the robot is manually analyzed and the customer intentions are extracted, followed by appropriate follow-up actions).

The scales used in this study are all mature scales published in international journals and validated by empirical studies. Participants were asked to rate all items on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

Perceived HCI. We used a five-item scale developed by Gefen et al. (2003) to assess perceived HCI. As most perceived HCI questionnaires have not addressed employee, we rephrased the items to fit our context. The perceived HCI questionnaire contains a total of 5 items, those were “it is easy for me to become skillful at using the digital technology”, “I find it easy to get the digital technology to do what I want it to do”, “the digital technology is flexible to interact with”, “the digital technology enhances my effectiveness”, “the digital technology improve my job performance” (Cronbach’s a = 0.96).

Helping behavior. Referring to Eissa & Lester (2018), we used three items to measure employees’ helping behavior. A sample item is “we goes out of the way to help coworkers with work-related problems” (Cronbach’s a = 0.85).

Control variables. This study controlled for the basic information of the subjects, including gender, age, years of work, education level and type of industry.

Manipulation Check. First, the participants were tested for manipulation. The results of independent sample t-test showed that there were no significant differences in demographic variables, including gender, age, working years, education level and industry type, between the high-level manipulation group and the low-level manipulation group. Secondly, the results of independent sample t-test showed that they held a higher perceived HCI in the high-level control group (M = 4.31, SD = 0.37; t (148) = 7.25, p < 0.001; Cohen’s d = 1.18.) than in the low-level control group (M = 3.22, SD = 1.23). This indicates that our experimental manipulation of perceived HCI in this study was successful.

Hypothesis Testing. An independent sample t-test was used to carry out the main effect hypothesis test. The results showed that the level of helping behavior of the participants in the high-level manipulation group (M = 3.92, SD = 0.65) was significantly higher than the participants in the low-level manipulation group (M = 3.40, SD = 1.14), t (148) = 3.46, p < 0.001, Cohen’s d = 565. Therefore, perceived HCI has a significant positive impact on employee helping behavior, and hypothesis 1 was supported.

The sample comprised 265 employees of which 50.6% were younger than 30 years. A total of 44.2% of the sample was male. About 61.5% of the sample had a bachelor’s degree. The percentage of the sample with a tenure of six years or less is 57%.

All responses were reported on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Perceived HCI (Cronbach’s a 0.90) and helping behavior (Cronbach’s a 0.84) were measured in the same way as in study 1.

RBSE. Referring to Parker et al. (2006), seven items were used to measure RBSE. A sample item is “Designing new procedures for your work area” (Cronbach’s a 0.85).

Digital Fluency. Digital fluency were measured using the sixteen-item scale developed by Chou and Chiu (2020). The scale items included such as “I can select and use the appropriate tools to accomplish a variety of tasks, such as taking pictures and making films” (Cronbach’s a = 0.94).

Control Variable. Consistent with the extant research (Ouyang et al., 2021), several demographic factors that influence helping behavior were controlled (i.e., gender, age, education and working seniority).

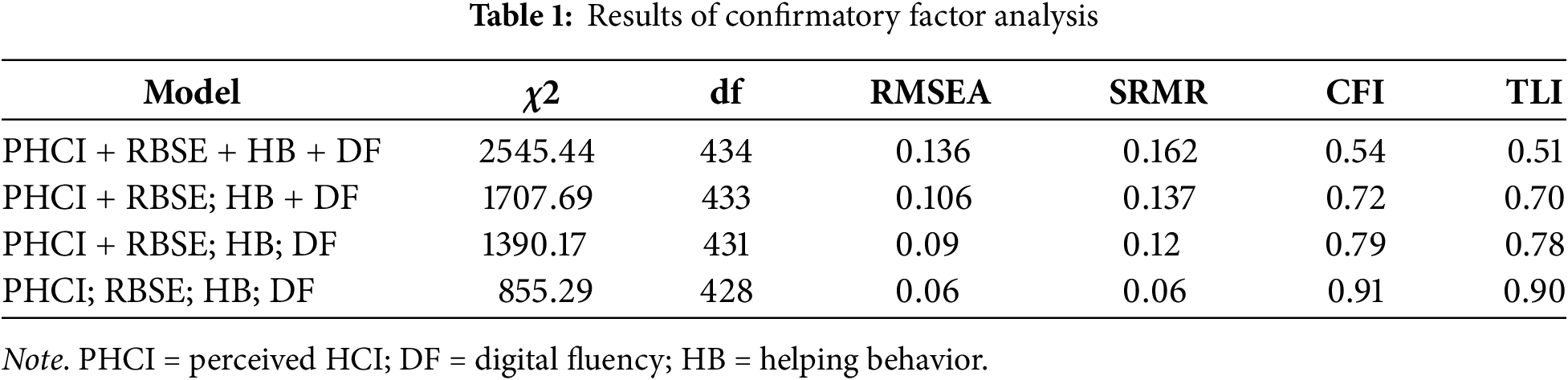

Reliability and validity analyses. All study variables had acceptable construct reliabilities with alphas above 0.8. The average variance extracted (AVE) as shown in Table 1 is greater than 0.5 (Fornell & Larcker, 1981). Therefore, each variable in the study possesses good convergent validity. The results of confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) as shown in Table 1 reveal that the hypothesized four-factor model has better fit indices (χ2 = 855.29, df = 428, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90) compared with alternative models, such as the three-factor model (χ2 = 1390.17, df = 431, RMSEA = 0.09, SRMR = 0.12, CFI = 0.79, TLI = 0.78) grouping digital fluency and RBSE, which initially confirms the discriminant validity.

Common method bias examinations. We tested for CMB by two ways. First, the data collected were tested for common method deviation by Harman single-factor test. The results of the exploratory factor analysis without rotation extracted a total of four factors, and the maximum factor variance interpretation rate was 32.176% (less than 40%). Thus, no dominant factor explained the variance in our sample (Podsakoff & Organ, 1986). Second, we used the unmeasured latent method construct (ULMC) approach to test CMB (Richardson et al., 2009). We construct two models: Model 1 includes independent variables, mediation variables, moderation variables and dependent variables (as shown in Table 1); Model 2 adds a latent variable. The results reveal that the fitting index of model 2 (χ2 = 747.10, df = 398, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.05, CFI = 0.92, TLI = 0.91) is not significantly better than model 1 (χ2 = 855.29, df = 428, RMSEA = 0.06, SRMR = 0.06, CFI = 0.91, TLI = 0.90). Thus, no serious common method bias exists in our study.

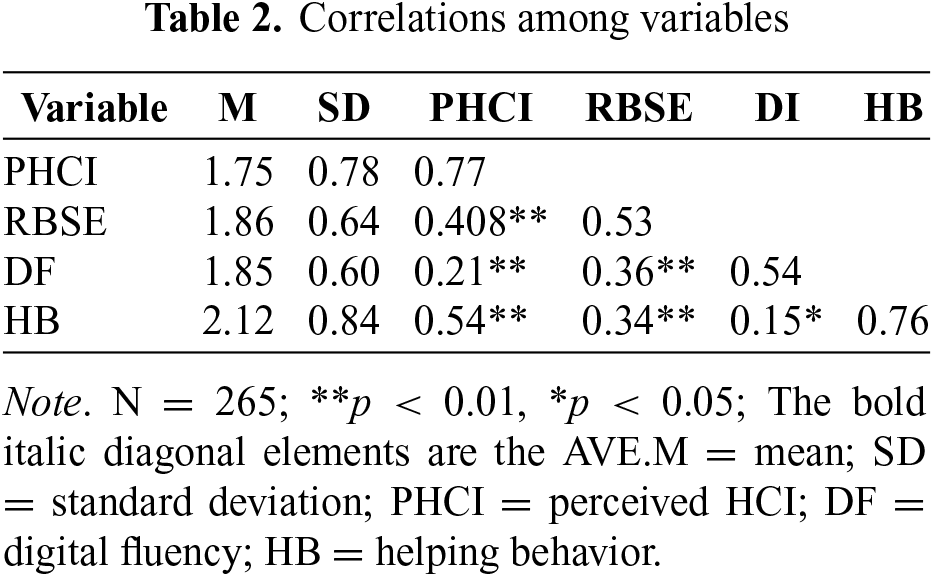

Descriptive statistics and correlations. Table 2 shows the means, standard deviations, intercorrelations among the study variables and AVE. The relatively close correlations provide preliminary support for our hypotheses.

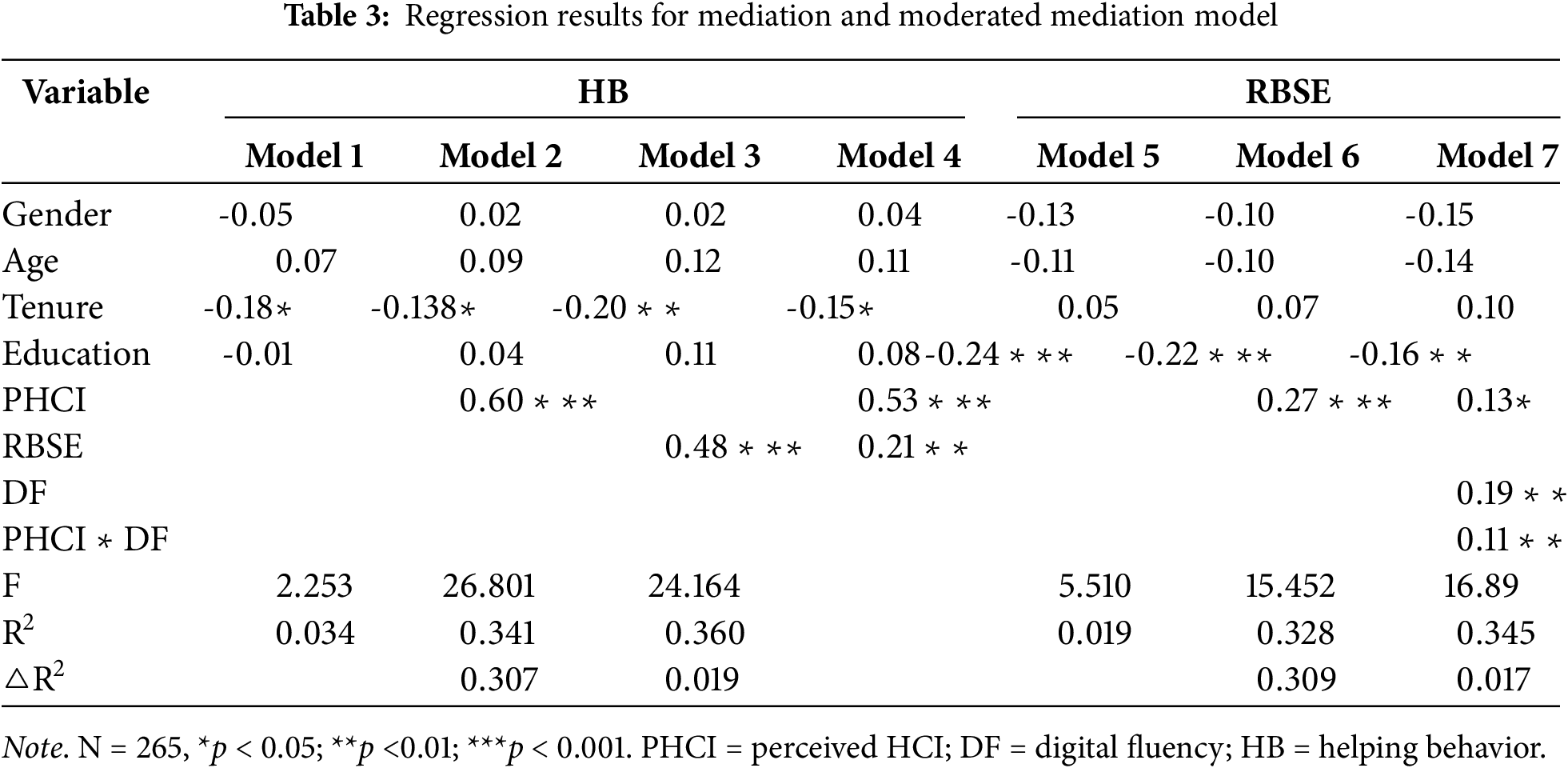

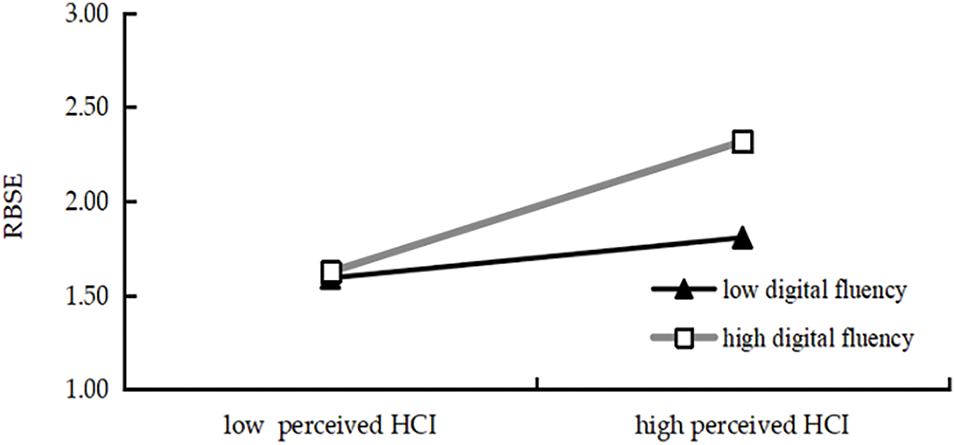

We adopted regression analyses and PROCESS macro in SPSS to test the hypotheses (see Table 3). Hypothesis 1 posits that perceived HCI has a positive effect on helping behavior. With the demographic variables controlled, we entered perceived HCI to predict helping behavior. As presented in Table 3, perceived HCI is positively related to helping behavior (model 2: B = 0.60, p < 0.001), thus supporting Hypothesis 1. Hypothesis 4 assumes the mediating effects of RBSE. The results in Table 3 show that perceived HCI is positively related to RBSE (model 6: B = 0.27, p < 0.001), and RBSE are positively related to helping behavior (model 3: B = 0.48, p < 0.001), supporting Hypothesis 2 and Hypothesis 3. Further, given that bootstrapping could be more powerful when testing the mediation effects (Lau and Cheung, 2012), we applied model 4 of the templates for PROCESS macro to test Hypothesis 4. With 5000 bootstrap samples, the indirect effects of perceived HCI on helping behavior via RBSE are significantly positive (B = 0.07; 95% BCa CI [0.01, 0.15]). Hence, Hypothesis 4 is verified. Hypothesis 5 proposes the moderating effects of digital fluency. We mean-centered the key variables in case of multicollinearity. As demonstrated in Table 3, the interaction item (perceived HCI*digital fluency) has a significantly positive influence

on RBSE (model 7: B = 0.11, p < 0.01), displaying the moderating effects of digital fluency. Furthermore, we conducted simple slope tests using model 1 in the process macro. The conditional effects of perceived HCI on RBSE are significant when digital fluency is high (B = 0.33; 95% BCa CI [0.23, 0.42]) and nonsignificant when it is low (B = 0.02; 95% BCa CI [−0.18, 0.22]). Meanwhile, Figure 2 confirms the effects for employees with high levels of digital fluency. Hypothesis 5 is supported.

Figure 2: Interaction of perceived HCI and digital fluency for RBSE

To test the moderated mediation posited in Hypothesis 6, we employed model 7 in the process macro with 5000 bootstrap samples. We examined the conditional indirect effects of perceived HCI on helping behavior via RBSE at three levels of digital fluency (1-SD, 1 + SD). The results (Figure 2) showed that the indirect effects are significantly positive in the case of high digital fluency (B = 0.07; 95% BCa CI [0.01, 0.16]) but nonsignificant when digital fluency is at low level (B = 0.004; 95% BCa CI [−0.0589, 0.0548). The moderated mediation effect is also significant (B = 0.05; 95% BCa CI [0.0023, 0.1848]). Overall, Hypothesis 6 is supported.

Our study investigated the impact of perceived HCI in the workplace and addresses the need to emphasize the relationship between technology and individuals (Murray et al., 2021). The integration of individuals and digital technology is a crucial concern and significant challenge in the field of human resource management (Stone et al., 2015). However, it should be noted that research in this domain is still evolving. The findings of the current study further enhance confidence in the positive models of perceived HCI and may stimulate further research on HCI between employees and digital technology within the context of a digitalized office.

Second, this study verified the positive impact of perception HCI on helping behavior based on SCT. Previous studies have predominantly relied on social exchange theory and conservation of resources theory to explain the relationship between organizational members’ support and employee helping behavior (De Clercq et al., 2019; Yang et al., 2020). However, SCT was mainly used to explain employee behaviors in interpersonal interaction scenarios in previous studies (Zhang et al., 2020).

Third, the present study findings indicate that employees possessing a high level of digital fluency can enhance the positive association between perceived HCI and RBSE. This aligns with the call for renewed research attention towards understanding the relationship between human beings and technology in physical form (Sergeeva et al., 2020). The result not only underscores the pivotal role of employees’ digital fluency in the contemporary digital era but also offers a means to establish the employee-digital technology relationship from an employee-centric perspective.

Our results have implications for management practices. Importantly managers wanting to increase their employees’ helping behavior, should prioritize the employee experience during the process of HCI. for instance, understand employees’ thoughts and suggestions about digital technology or enhance the performance of digital technologies (i.e., usability and usefulness). Moreover, to promote helping behavior through perceived HCI, managers should focus on enhancing employee RBSE, for instance, optimizing the performance of digital technologies from the perspective of employee needs.

Finally, managers should foster the digital and cognitive capabilities of their employees. This can be achieved through initiatives such as implementing a talent strategy for digital transformation, formulating human resources policies tailored to digital talents, and establishing collaborative digital teams.

Limitations and future recommendations

Firstly, the cross-sectional design and self-reported measures were limitations. Future studies should adopt longitudinal design examine possible causal relationship between variables. Moreover, investigating additional mediators (e.g., work meaningfulness and autonomy of work) can also add value to this research. For future directions, it is worthwhile adding other employee outcomes (e.g., task performance and innovation behavior) as the evidence that may be helpful to guidance for enhancing organizational performance through perceived HCI.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The research was funded and supported by the Ministry of Education in China Project of Humanities and Social Sciences (Grant No. 23YJC630120), Hubei Provincial Department of Education Science and Technology Plan Project (Grant No. Q20221605), and Research Project of Wuhan Polytechnic University (Grant No. 2022Y32).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Xin Liu; data collection: Xin Liu; analysis and interpretation of results: Xin Liu, Zimeng Chen; draft manuscript preparation: Xin Liu, Zimeng Chen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Ethics approval was granted by Bioethics Committee of Wuhan Polytechnic University (No. BME-2024-1-27).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Alsharo, M., Gregg, D., & Ramirez, R. (2017). Virtual team effectiveness: The role of knowledge sharing and trust. Information & Management, 54(4), 479–490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.im.2016.10.005 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Beltrán-Martín, I., Bou-Llusar, J. C., Roca-Puig, V., & Escrig-Tena, A. B. (2017). The relationship between high performance work systems and employee proactive behaviour: Role breadth self-efficacy and flexible role orientation as mediating mechanisms. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(3), 403–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12145 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Breuer, C., Hüffmeier, J., Hibben, F., & Hertel, G. (2019). Trust in teams: A taxonomy of perceived trustworthiness factors and risk-taking behaviors in face-to-face and virtual teams. Human Relations, 73(1), 3–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718818721 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chou, Y.-C., & Chiu, C.-H. (2020). The development and validation of a digital fluency scale for preadolescents. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 29(6), 541–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-020-00505-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

De Clercq, D., Haq, I. U., & Azeem, M. U. (2019). Threatened but involved: Key conditions for stimulating employee helping behavior. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 27(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051819857741 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Eissa, G., & Lester, S. W. (2018). When good deeds hurt: The potential costs of interpersonal helping and the moderating roles of impression management and prosocial values motives. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(3), 339–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051817753343 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gao, P., & Gao, Y. (2024). How does digital leadership foster employee innovative behavior: A cognitive-affective processing system perspective. Behavioral Sciences, 14(5), 362. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14050362 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and tam in online shopping. An Integrated Model MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/30036519 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Halbesleben, J. R. B., & Wheeler, A. R. (2012). To invest or not? The role of coworker support and trust in daily reciprocal gain spirals of helping behavior. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1628–1650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312455246 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hao, P., He, W., & Long, L.-R. (2017). Why and when empowering leadership has different effects on employee work performance: The pivotal roles of passion for work and role breadth self-efficacy. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 25(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051817707517 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hovens, D. (2020). Workplace learning through human-machine interaction in a transient multilingual blue-collar work environment. Journal of Linguistic Anthropology, 30(3), 369–388. https://doi.org/10.1111/jola.12279 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, X., & Zulkifli, N. (2023). How enterprise social media shapes employee job performance: A technology affordance lens. International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, 20(7), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1142/S0219877023500438 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hwang, P. C., Han, M. C., & Chiu, S. F. (2015). Role breadth self-efficacy and foci of proactive behavior: Moderating role of collective, relational, and individual self-concept. The Journal of Psychology, 149(8), 846–865. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2014.985284 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Koopman, J., Lanaj, K., & Scott, B. A. (2016). Integrating the bright and dark sides of OCB: A daily investigation of the benefits and costs of helping others. Academy of Management Journal, 59(2), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0262 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lau, R. S., & Cheung, G. W. (2012). Estimating and comparing specific mediation effects in complex latent variable models. Organizational Research Methods, 15(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110391673 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, S., Jia, R., Seufert, J. H., Luo, J., & Sun, R. (2022). You may not reap what you sow: How and when ethical leadership promotes subordinates’ online helping behavior. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 40(4), 1683–1702. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-022-09831-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Y., Ye, H. J., Liu, A., Yang, X., & Wang, X. (2018). Will digital fluency influence social media use? An empirical study of wechat users. ACM SIGMIS Database: the DATABASE for Advances in Information Systems, 49(4), 30–45. https://doi.org/10.1145/3290768.3290773 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lin, W., Koopmann, J., & Wang, M. (2018). How does workplace helping behavior step up or slack off? Integrating enrichment-based and depletion-based perspectives. Journal of Management, 46(3), 385–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206318795275 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, Y., & Shrum, L. J. (2002). What is interactivity and is it always such a good thing? Implications of definition, person, and situation for the influence of interactivity on advertising effectiveness. Journal of Advertising, 31(4), 53–64. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2002.10673685 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ma, C., Chen, Z. X., & Jiang, X. (2021). Give full play to the talent: Exploring when perceived overqualification leads to more altruistic helping behavior through extra effort. Personnel Review, 51(6), 1727–1745. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-03-2020-0164 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

McAllister, D. J., Kamdar, D., Morrison, E. W., & Turban, D. B. (2007). Disentangling role perceptions: How perceived role breadth, discretion, instrumentality, and efficacy relate to helping and taking charge. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1200–1211. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1200 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Murray, A., Rhymer, J., & Sirmon, D. G. (2021). Humans and technology: Forms of conjoined agency in organizations. Academy of Management Review, 46(3), 552–571. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2019.0186 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ouyang, X., Zhou, K., Zhan, Y.-F., & Yin, W.-J. (2021). A dynamic process of different helping behavior: From the extended self-theory perspective. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 37(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-10-2020-0573 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Park, M., & Yoo, J. (2020). Effects of perceived interactivity of augmented reality on consumer responses: A mental imagery perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 52(3), 101912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.101912 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Parker, S. K. (1998). Enhancing role breadth self-efficacy: The roles of job enrichment and other organizational interventions. Journal of Applied Psychology, 83(6), 835–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.83.6.835 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Parker, S. K. (2000). From passive to proactive motivation: The importance of flexible role orientations and role breadth self-efficacy. Applied Psychology, 49(3), 447–469. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00025 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner, N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. J Appl Psychol, 91(3), 636–652. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636 [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pitafi, A. H., Kanwal, S., Ali, A., Khan, A. N., & Waqas Ameen, M. (2018). Moderating roles of it competency and work cooperation on employee work performance in an ESM environment. Technology in Society, 55(1), 199–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2018.08.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920638601200408 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 762–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109332834 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sergeeva, A. V., Faraj, S., & Huysman, M. (2020). Losing touch: An embodiment perspective on coordination in robotic surgery. Organization Science, 31(5), 1248–1271. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2019.1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shen, J., & Benson, J. (2016). When csr is a social norm: How socially responsible human resource management affects employee work behavior. Journal of Management, 42(6), 1723–1746. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314522300 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sohn, D. (2011). Anatomy of interaction experience: Distinguishing sensory, semantic, and behavioral dimensions of interactivity. New Media & Society, 13(8), 1320–1335. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444811405806 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Stone, D. L., Deadrick, D. L., Lukaszewski, K. M., & Johnson, R. (2015). The influence of technology on the future of human resource management. Human Resource Management Review, 25(2), 216–231. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2015.01.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sun, Z.-Y., Li, J.-M., Li, B., & He, X.-Y. (2024). Digital leadership and deviant innovation: The roles of innovation self-efficacy and employee ambitions. Current Psychology, 43(26), 22226–22237. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-06030-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Topcuoglu, E., Oktaysoy, O., Erdogan, S. U., Kaygin, E., & Karafakioglu, E. (2023). The mediating role of job security in the impact of digital leadership on job satisfaction and life satisfaction. Marketing and Management of Innovations, 14(1), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.21272/mmi.2023.1-11 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Voorveld, H. A. M., Neijens, P. C., & Smit, E. G. (2011). The relation between actual and perceived interactivity. Journal of Advertising, 40(2), 77–92. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367400206 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Q., Myers, M. D., & Sundaram, D. (2013). Digital natives und digital immigrants. Wirtschaftsinformatik, 55(6), 409–420. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11576-013-0390-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, Z., & Wang, N. (2012). Knowledge sharing, innovation and firm performance. Expert Systems with Applications, 39(10), 8899–8908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2012.02.017 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, C., Zhang, Y., & Feng, J. (2024). How do older employees achieve successful ageing at work through generativity in the digital workplace? A self-affirmation perspective. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 97(4), 1475–1501. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12525 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wei, C., Pitafi, A. H., Kanwal, S., Ali, A., & Ren, M. (2020). Improving employee agility using enterprise social media and digital fluency: Moderated mediation model. IEEE Access, 8, 68799–68810. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2020.2983480 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Williams, D. L., & Crittenden, V. (2012). The use of social media: An exploratory study of usage among digital natives. Journal of Public Affairs, 12(2), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/pa.1414 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wu, G. (2006). Conceptualizing and measuring the perceived interactivity of websites. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 28(1), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2006.10505193 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, W., Hao, Q., & Song, H. (2020). Linking supervisor support to innovation implementation behavior via commitment. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(3), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-04-2018-0171 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, F., & Shen, F. (2017). Effects of web interactivity: A meta-analysis. Communication Research, 45(5), 635–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650217700748 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, Z., Zhang, L., Xiu, J., & Zheng, J. (2020). Learning from your leaders and helping your coworkers: The trickle-down effect of leader helping behavior. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(6), 883–894. https://doi.org/10.1108/LODJ-07-2019-0317 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhao, J., Hu, E., Han, M., Jiang, K., & Shan, H. (2023). That honey, my arsenic: The influence of advanced technologies on service employees’ organizational deviance. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 75(4), 103490. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2023.103490 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools