Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Playful work design, flow, and employee creativity

Business School, Xiangtan University, Xiangtan, 411105, China

* Corresponding Author: Jian Zhu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(2), 199-205. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065792

Received 28 August 2024; Accepted 25 January 2025; Issue published 30 June 2025

Abstract

This study explores the impact of playful work design on employee creativity through flow, as well as the moderating role of playful climate in this relationship. We collected data from 272 employees across various industries in China (47.2% from the service industry; 61.8% female; 63.6% aged 26–40 years). Participants completed measures of playful work design, flow, playful climate, and creativity. Through hierarchical regression and bootstrapping analyses, the results indicate that: (a) playful work design is positively associated with creativity; (b) flow mediates this relationship; and (c) playful climate strengthens the link between playful work design and flow, thereby enhancing employee creativity. These findings support work flow theory by demonstrating that playful work design satisfies employees’ basic psychological needs, stimulates intrinsic motivation, and ultimately induces flow to enhance creativity. For practical implications, managers should prioritize employees’ work experience, monitor their flow states, and foster a playful climate.Keywords

Employee creativity is critical to organizational competitiveness. However, employee creativity cannot be externally imposed on employees; they must discover and explore it based on their inclinations and within a supportive work climate (Amabile, 1983). Work climate characteristics—including leadership styles, collaborative behaviors, physical workspace design, and technological infrastructure—significantly influence creative engagement (Anderson et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2016; Lee et al., 2020). Notably, creative potential often emerges serendipitously when employees engage in playful experimentation to optimize work outcomes. This aligns with the concept of playful work design, defined as the process in which employees proactively create conditions that promote enjoyment and challenge without altering the inherent design of the job itself (Bakker et al., 2020b; Bakker et al., 2023).

Despite the documented impact on productivity and competitive advantage (Caracuzzo et al., 2024; Fluegge-Woolf, 2014), the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity remains insufficiently explored. This study aims to address this gap by investigating the impact of playful work design on employee creativity, the mediating role of flow, and the moderating effect of playful climate in the playful work design-creativity relationship.

Playful work design and employee creativity

The core concept of playful work design asserts that “play” is not merely an activity but a mode of executing tasks (Mainemelis & Ronson, 2006). As an individual work design strategy, playful work design is embedded in work—specifically, play as engagement with work (Hoang & Le, 2024; Mainemelis & Ronson, 2006). Through playful work design, employees may experience enhanced overall work engagement (Gerdenitsch et al., 2020; Lazazzara et al., 2020). Existing research suggests that when employees approach their work in an entertaining manner, they are more likely to exhibit higher engagement, generate greater creativity, and achieve better job performance (Bakker et al., 2020a; Caracuzzo et al., 2024; Dishon-Berkovits et al., 2024; Scharp et al., 2019). Hunter et al., (2010) argues that workplace playfulness can alleviate job stress and fatigue while fostering social interaction among organizational members. Moreover, employees who embrace playfulness often produce more innovative ideas, break free from routine, and even enhance divergent and creative thinking through playful activities (Liu et al., 2023, 2024).

Flow, in the context of work experience, is characterized by intense concentration, enjoyment of work, and intrinsic motivation (Csikszentmihalyi, 2014). Research on the application of flow in the workplace indicates that employees can not only experience flow in specific gamified tasks but also sustain it across tasks when appropriate playful elements are incorporated (Nakamura & Csikszentmihalyi, 2002; Silic et al., 2020).

Flow is hypothesized to mediate the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity by fostering divergent and creative thinking, thereby enhancing innovative behaviors (Dan, 2021; Li & Tao, 2023). When interest and challenge are balanced, individuals experience heightened work efficiency, enabling them to quickly develop solutions to problems (Silic et al., 2020). Engaging in gamified work tasks facilitates flow experiences, allowing employees to maintain psychological engagement and full immersion in their tasks (Rich, et al., 2010). Moreover, playful work design enhances enjoyment at work by incorporating playful or competitive task performance—such as through humor, fun, and imagination (Scharp et al., 2022; Tews et al., 2014).

Playful work climate is by playful interactions among employees (Pors & Andersen, 2015; Chang et al., 2013), contributes to employee creativity. A playful climate frees the mind for creativity (Zhou et al., 2022). When employees experience a playful work environment, they are more likely to autonomously develop their creative outputs (Deci & Vansteenkiste, 2004; Ryan & Deci, 2000) through a sense of autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Celestine & Yeo, 2021). In such a climate, employees enjoy flexible decision-making, and work leaders who are open and receptive to employee perspectives and emotions. This environment unleashes individual potential for novel problem-solving approaches rather than conventional thinking (Silic et al., 2020; Yao et al., 2024; Yu et al., 2003; Zhou et al., 2022).

This study aimed to explore the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity through flow, as well as the moderating role of playful climate in this relationship. Figure 1 presents the hypothesized model for this study. Based on our conceptual model, we tested the following hypotheses.

Figure 1: Theoretical model

Hypothesis 1 (H1): Playful work design is positively associated with employee creativity.

Hypothesis 2 (H2): Playful work design is positively associated with flow.

Hypothesis 3 (H3): Flow mediates the positive relationship between playful work design and employee creativity.

Hypothesis 4 (H4): Playful climate moderates the relationship between playful work design and for higher work flow.

Hypothesis 5 (H5): Playful climate moderates the mediating role of flow between playful work design and employee creativity for higher employee creativity.

The total sample (n = 272) comprised of 104 (38.2%) males and 168 (61.8%) females. In terms of industry, mostly (47.2%) from service industry. In terms of age, the majority (63.6%) were aged between 26 and 40 years old. In terms of education, the majority (94.5%) have a bachelor’s degree or above. In terms of work experience, the majority (63.6%) were with more than three years on their jobs.

We adopted established scales to measure the constructs under study. To ensure accuracy, the original English versions were translated into Chinese through the forward-and-backward translation process. All measures used a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree; 5 = strongly agree).

Playful work design. Playful work design was measured using a 24-item scale developed by Scharp et al. (2023), comprising two dimensions: fun design (12 items; e.g., ‘I handle my work in a fun way’) and competitive design (12 items; e.g., ‘I often set time records in work tasks’). In the present study, the scale demonstrated good reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.75.

Flow. Flow was measured using a 9-item scale developed by Martin and Jackson (2008). Sample items include: “I don’t think about other things while working”, and “My attention is completely focused on the task at hand”. In the present study, the scale demonstrated good reliability, with a Cronbach’s α of 0.82.

Employee creativity. Employee creativity was measured using the 7-item scale developed by Farmer et al. (2003). Sample items include: “At work, I often come up with creative ideas or suggestions”, and “I promote my new viewpoints and ideas to other colleagues”. The Cronbach’s α for the employee creativity scale in this study was 0.81.

Playful climate. Playful climate was measured with a 20-item scale developed by Yu et al. (2003). The scale consists of four subscales: colleague affection (5 items, e.g., ‘Members in the organization are close, friendly, and communicate pleasantly with each other’), supervisor support (5 items, e.g., ‘My supervisor can set aside status differences and connect with everyone’), joy at work (5 items, e.g., ‘Playing with colleagues gives me a sense of teamwork’), and environmental construction (5 items, e.g., ‘The workplace environment makes it easy for everyone to get close and familiar with each other’). The Cronbach’s α for the playful climate scale in this study was 0.875.

Control Variables. Drawing on previous research on employee creativity, individuals’ personal characteristics can influence creativity. Additionally, playfulness traits are often conceptualized as expressions of certain personality characteristics (Barnett, 2007; Celestine & Yeo, 2021; Petelczyc et al., 2018; Tett & Burnett, 2003). Therefore, this study considers individual characteristics such as gender, age, education level, working seniority as control variables.

This study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Xiangtan University (Approval Number: 20240201). All participants informed consent prior to participation. Using a two-wave longitudinal design with a one-week interval, we first collected data on playful climate and control variables (Time 1), followed by measures of playful work design, flow, and employee creativity (Time 2). The survey was implemented via the Credamo online research platform.

We conducted the analysis using MPLUS 8.3 and SPSS 25.0. First, we performed confirmatory factor analysis and tested common method variance. Second, we applied hierarchical regression analysis and bootstrapping analysis to test our hypotheses.

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted using Mplus 8.3 to examine discriminant validity. As presented in Table 1, the hypothesized four-factor model demonstrated superior fit to the data (X2/df = 2.076, RMSEA = 0.065, CFI = 0.923, TLI = 0.91, SRMR = 0.025) compared with alternative models, thereby supporting the discriminant validity of the four constructs.

Common method variance testing

Given that all measures (playful work design, flow, employee creativity, and playful climate) were collected through self-report questionnaires, we performed Harman’s single-factor test using SPSS 25.0 to examine potential common method variance (CMV). Principal component analysis without rotation indicated that the first factor explained 33.27% of the total variance, below the recommended 40% threshold (Podsakoff et al., 2003), suggesting that common method bias was not a substantial concern in this study.

Descriptive statistics and correlation analysis

Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations of the study variables. Playful work design is positively correlated with flow (γ = 0.539, p < 0.01) and employee creativity (γ = 0.623, p < 0.01). Employee creativity is positively correlated with flow (γ = 0.540, p < 0.01). The correlations among the main variables provided initial support for the theoretical model.

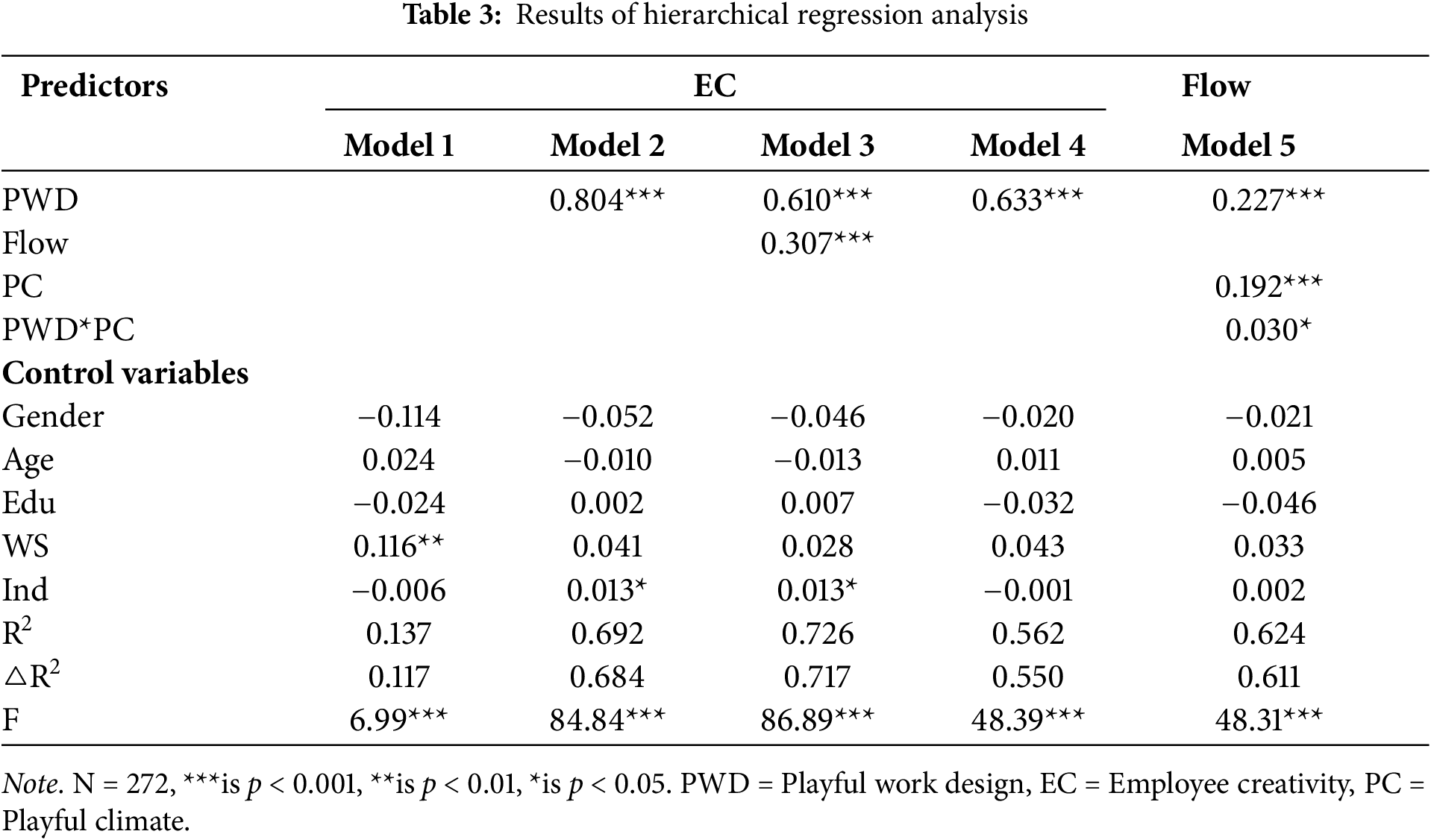

We employed hierarchical regression analysis to test the hypotheses. The results are presented in Table 3. As shown in Table 3, playful work design is positively related to employee creativity (β = 0.804, p < 0.001, Model 2), thus confirming H1. Additionally, playful work design is positively associated to flow (β = 0.633, p < 0.001, Model 4), which supports H2. Model 3 (which controls for playful work design), examines the impact of flow on employee creativity. The results indicate that, compared to Model 2, the regression coefficient for the effect of playful work design on employee creativity decreases (β = 0.610, p < 0.001, in Model 3), while the coefficient for the effect of flow on employee creativity is significantly positive (β = 0.307, p < 0.001, in Model 3). These findings indicate that flow partially mediates the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity, thereby supporting H3.

The interaction between playful work design and playful climate has a significant positive effect on flow (β = 0.030, p < 0.05, Model 5), supporting H4. Furthermore, Figure 2 illustrates that when playful climate is high (+1 SD), the positive relationship between playful work design and flow is stronger compared to when playful climate is low (−1 SD). This indicates that a higher playful climate enhances the positive effect of playful work design on flow.

Figure 2: The moderation effect of PC on the relationship between PWD and Flow

Furthermore, we used Hayes’s (2017) SPSS macro PROCESS to test the moderated mediation effect through bias-corrected bootstrapping. This analysis estimated the conditional indirect effects of the predictor on the outcome via the mediator at low (mean −1 SD) and high (mean +1 SD) levels of the moderator. As shown in Table 4, the indirect effect of playful work design on employee creativity through flow was insignificant under low playful climate (effect = −0.014, 95% CI [−0.170, 0.088], including zero). However, under high playful climate, this indirect effect became significant (effect = 0.182, 95% CI [0.053, 0.404], excluding zero). The index of moderated mediation was also significant (effect = 0.084, 95% CI [0.032, 0.138], excluding zero). These results confirm that playful climate significantly moderates the indirect effect of playful work design on employee creativity through flow, thereby supporting H5.

First, playful work design waspositively associated with employee creativity, aligning with prior research (Bakker et al., 2020b; Scharp et al., 2019). This relationship can be explained through the lens of basic psychological needs: By incorporating enjoyable tasks or competitive elements, playful work design fulfills employees’ needs for autonomy, relatedness, and competence, thereby increasing work engagement and fostering employees’ creativity.

Second, playful work design indirectly enhanced employees’ creativity through flow. This finding can be explained by the fact that during the execution of playful work tasks, the generation of flow allows employees to maintain a psychological connection with the tasks enabling them to immerse themselves wholeheartedly in the work (Rich, et al., 2010). Moreover, employees who derive enjoyment from their work are more likely to concentrate on their tasks, leading to better creative performance (Fluegge-Woolf, 2014).

Third, playful climate moderated both the relationship between playful work design and flow and the indirect positive effect of playful work design on employee creativity through flow. Specifically, a stronger playful climate amplified the positive influence of playful work design on flow, resulting in higher creativity. These findings echo Yu et al.’s (2003) conclusion that in work environments with strong playful climates, employees gradually develop tacit understanding through spontaneous and casual exchanges—such as light-hearted jokes or leisurely games—which promote both physical/mental relaxation and enhanced creativity.

Contributions to theory and practice

This study makes significant contributions to existing theories in multiple dimensions. First, it extends the application of flow theory to research on playful work design. The findings reveal that playful work design provides a novel perspective for stimulating employee creativity. Acting as a partial mediator between playful work design and creativity, flow effectively transmits the positive influence of playful work design.

Second, by integrating flow theory with self-determination theory, the findings suggest that an organization’s playful climate acts as a boundary condition for the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity. Specifically, in organizations with a strong playful climate, the positive impact of playful work design on employee creativity becomes more pronounced, and flow’s mediating role is more significant. Simultaneously, it broadens the scope of application of the self-determination theory within the realm of organizational management.

Regarding practical implications, managers should attach importance to personalized task models that foster flow experiences at work, thereby enhancing employee creativity. Organizations should grant employees a degree of autonomy in their work to stimulate creative thinking among employees. Therefore, in recruiting and selecting employees for positions that demand high creativity (e.g., product design, advertising design, technical research and development, copywriting, marketing, etc.), managers can assess candidates’ playful thinking patterns and work styles through resume screening, interviews, and other selection processes.

Organizations should actively cultivate a playful climate. We recommend integrating playful management philosophies by: (a) creating relaxed and enjoyable work environments; (b) establishing cultures that tolerate mistakes and encourage risk-taking; and (c) promoting openness and inclusiveness.

Lastly, organizations should focus on enhancing employees’ job experiences, monitoring their work states, and helping them develop the ability to engage in playful work design. The secret to stimulating employee creativity through a playful work climate lies in the fact that a relaxed and enjoyable work environment can evoke positive emotions, leading employees into a state of flow. Training initiatives (or programs) should be combined with goal-setting and coaching to help employees discover game-like features in their work tasks and implement new work design strategies in their daily practices, thereby stimulating their bottom-up proactiveness.

Limitations and future studies

Firstly, all variables in this study are based on self-reports, which may lead to CMV. Although the Harman single-factor test confirmed that CMV is within an acceptable range, future research should consider using cross-level analyses to eliminate potential issues caused by CMV. Secondly, flow only partially mediates the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity, indicating that there is still considerable unexplored territory in the mechanism between the two. Future research could consider other potential mediating variables to explore the influence mechanism of playful work design on employee creativity. Lastly, it must be acknowledged that not all jobs are suitable for playful work design. Future in-depth investigations could focus on specific industrial sectors.

This study constructs a moderated mediation model to provide a comprehensive understanding of the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity, with flow serving as the mediator and playful climate as the moderator. The results indicate: (a) playful work design directly and positively affects employee creativity. (b) playful work design indirectly and positively affects employee creativity through flow. (c) Playful climate positively moderates the relationship of playful work design and flow. (d) Playful climate positively moderates the mediating effect of flow on the relationship between playful work design and employee creativity. This study extends the theoretical framework of antecedents of employee creativity from a new perspective and expands the literature that applies games to the workplace.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the scientific research project of the Education Department of Hunan Province, China (Grant No. 24A0123).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Jian Zhu, Xin Wen; data collection: Xin Wen; analysis and interpretation of results: Jian Zhu, Xin Wen; draft manuscript preparation: Jian Zhu, Xin Wen. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated for this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1983). The social psychology of creativity: A componential conceptualization. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 45(2), 357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Anderson, N., Potočnik, K., & Zhou, J. (2014). Innovation and creativity in organizations: A state-of-the-science review, prospective commentary, and guiding framework. Journal of Management, 40(5), 1297–1333. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314527128 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., Breevaart, K., Scharp, Y. S., & de Vries, J. D., (2023). Daily self-leadership and playful work design: Proactive approaches of work in times of crisis. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 59(2), 314–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/00218863211060453 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., Hetland, J., Olsen, O. K., Espevik, R., & De Vries, J. D. (2020a). Job crafting and playful work design: Links with performance during busy and quiet days. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 122, 103478. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103478 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bakker, A. B., Scharp, Y. S., Breevaart, K., & De Vries, J. D. (2020b). Playful work design: Introduction of a new concept. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 23, 567. https://doi.org/10.1017/SJP.2020.20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Barnett, L. A. (2007). The nature of playfulness in young adults. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(4), 949–958. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.018 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Caracuzzo, E., Caputo, A., Callea, A., Cortese, C. G., & Urbini, F. (2024). Playful work design in fostering organizational citizenship behaviors and performance: Two studies on the mediating role of work engagement. Management Research Review, 47(9), 1422–1440. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-05-2023-0354 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Celestine, N. A., & Yeo, G. (2021). Having some fun with it: A theoretical review and typology of activity-based play-at-work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 42(2), 252–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2444 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chang, C. P., Hsu, C. T., & Chen, I. J. (2013). The relationship between the playfulness climate in the classroom and student creativity. Quality & Quantity, 47(3), 1493–1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-011-9603-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chen, T., Li, F., & Leung, K. (2016). When does supervisor support encourage innovative behavior? Opposite moderating effects of general self-efficacy and internal locus of control. Personnel Psychology, 69(1), 123–158. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12104 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2014). Toward a psychology of optimal experience. In: Flow and the foundations of positive psychology, pp. 209–226. Dordrecht: Springer, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-017-9088-8_14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dan, Y. (2021). Examining the relationships between learning interest, flow, and creativity. School Psychology International, 42(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034320983399 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2004). Self-determination theory and basic need satisfaction: Understanding human development in positive psychology. Ricerche Di Psicologia, 27, 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60130-6 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dishon-Berkovits, M., Bakker, A. B., & Peters, P. (2024). Playful work design, engagement and performance: The moderating roles of boredom and conscientiousness. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 35(2), 256–283. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2023.2227920 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Farmer, S. M., Tierney, P., & Kung-McIntyre, K. (2003). Employee creativity in Taiwan: An application of role identity theory. Academy of Management Journal, 46(5), 618–630. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040653 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fluegge-Woolf, E. R. (2014). Play hard, work hard: Fun at work and job performance. Management Research Review, 37(8), 682–705. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-11-2012-0252 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gerdenitsch, C., Sellitsch, D., Besser, M., Burger, S., Stegmann, C. et al. (2020). Work gamification: Effects on enjoyment, productivity and the role of leadership. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 43(2), 100994. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.elerap.2020.100994 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hayes, A. F. (2017). Partial, conditional, and moderated moderated mediation: Quantification, inference, and interpretation. Communication Monographs, 85(1), 4–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1352100 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hoang, T. H., & Le, Q. H. (2024). A self-regulatory adapting mechanism to changing work setting: Roles of playful work design and ambidexterity. Current Research in Behavioral Sciences, 6(1), 100148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crbeha.2024.100148 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hunter, C., Jemielniak, D., & Postuła, A. (2010). Temporal and spatial shifts within playful work. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 23(1), 87–102. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534811011017225 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lazazzara, A., Tims, M., & De Gennaro, D. (2020). The process of reinventing a job: A meta-synthesis of qualitative job crafting research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 116, 103267. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/a9wf7 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, A., Legood, A., Hughes, D., Tian, A. W., Newman, A. et al. (2020). Leadership, creativity and innovation: A meta-analytic review. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(1), 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2019.1661837 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, L., & Tao, H. (2023). Leveraging employee creativity through playfulness climate: The mediating role of working smart. Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal, 51(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.12678 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, Z., Yuan, L., Cao, C., Yang, Y., & Zhuo, F. (2024). How playfulness climate promotes the performance of millennial employees-the mediating role of change self-efficacy. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(3), 603–618. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-08-2023-0344 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Liu, W., Zhang, W., van der Linden, D.,, & Bakker, A. B. (2023). Flow and flourishing during the pandemic: The roles of strengths use and playful design. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24(7), 2153–2175. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-023-00670-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mainemelis, C., & Ronson, S. (2006). Ideas are born in fields of play: Towards a theory of play and creativity in organizational settings. Research in Organizational Behavior, 27(248), 81–131. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-3085(06)27003-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Martin, A. J., & Jackson, S. A. (2008). Brief approaches to assessing task absorption and enhanced subjective experience: Examining ‘short’ and ‘core’ flow in diverse performance domains. Motivation and Emotion, 32(3), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-008-9094-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nakamura, J., & Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2002). The concept of flow. Handbook of Positive Psychology, 89, 105. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780195135336.003.0007 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Petelczyc, C. A., Capezio, A., Wang, L., Restubog, S. L. D., & Aquino, K. (2018). Play at work: An integrative review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 44(1), 161–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317731519 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.879. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pors, J. G., & Andersen, N.Å. (2015). Playful organisations: Undecidability as a scarce resource. Culture and Organization, 21(4), 338–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/14759551.2014.924936 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rich, B. L., Lepine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 617–635. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.51468988 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Scharp, Y. S., Bakker, A. B., & Breevaart, K. (2022). Playful work design and employee work engagement: A self-determination perspective. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 134, 103693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2022.103693 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scharp, Y. S., Bakker, A. B., Breevaart, K., Kruup, K., & Uusberg, A. (2023). Playful work design: Conceptualization, measurement, and validity. Human Relations, 76(4), 509–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267211070996 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scharp, Y. S., Breevaart, K., Bakker, A. B., & van der Linden, D. (2019). Daily playful work design: A trait activation perspective. Journal of Research in Personality, 82(5), 103850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.103850 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Silic, M., Marzi, G., Caputo, A., & Bal, P. M. (2020). The effects of a gamified human resource management system on job satisfaction and engagement. Human Resource Management Journal, 30(2), 260–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/1748-8583.12272 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tett, R. P., & Burnett, D. D. (2003). A personality trait-based interactionist model of job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88, 500–517. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.3.500. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Tews, M. J., Michel, J. W., & Allen, D. G. (2014). Fun and friends: The impact of workplace fun and constituent attachment on turnover in a hospitality context. Human Relations, 67(8), 923–946. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713508143 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yao, H., Liu, W., & Chen, S. (2024). Teachers sustainable teaching innovation and graduate students creative thinking: The chain mediating role of playfulness climate and academic self-efficacy. The International Journal of Management Education, 22(1), 100900. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2023.100900 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yu, P., Wu, J., Lin, W., & Yang, J. X. (2003). Development of the adult playfulness scale and organizational playfulness atmosphere scale. Journal of The Chinese Psychological Testing Association, 50(1), 18–26. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Zhou, F., Zhang, N., & Mou, J. (2022). Universities as incubators of innovation: The role of a university playfulness climate in teachers’ sustainable teaching innovation. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100693. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100693 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools