Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing knowledge sharing in banking: The roles of responsible leadership, supportive climate and creative self-efficacy

School of Management, Harbin Institute of Technology, Harbin, 150001, China

* Corresponding Author: Li Zhang. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 299-308. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067169

Received 26 August 2024; Accepted 20 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study explores the interaction of responsible leadership, supportive climate, and creative self-efficacy in enhancing knowledge sharing among employees in the banking sector. Data from 314 employees (42% Females, 58% Males) were analyzed using structural equation modeling (SEM) and a time-lagged survey design. The analysis revealed a higher responsible leadership to be associated with both creative self-efficacy and knowledge sharing. Additionally, the study found that supportive climate moderation to significantly, strengthening the relationship between responsible leadership and knowledge sharing. Creative self-efficacy partially mediated this relationship to be stronger. The results indicate that responsible leadership and a supportive climate are crucial socio-cognitive mechanisms for enhancing knowledge sharing in organizations. The banking sector should aim to promote collaborative work partnerships implementing responsible leadership practices and cultivating supportive work environments to bolster organizational growth and competitiveness.Keywords

In today’s fast-paced and complex business environment, the ability to share knowledge effectively is not just advantageous but essential for sustaining growth and competitiveness (Aly, 2016). This assumes responsible leadership and a supportive work climate. Responsible leadership aligns organizational strategies with broader societal objectives, extending beyond mere profit-seeking to the well-being of stakeholders (Greige Frangieh & Khayr Yaacoub, 2017) and the environment (Lin et al., 2020). Supportive climate is conducive to exchanging creative ideas, risk-taking, and celebrating creativity (Holdren et al., 1986), all of which are integral to knowledge sharing and organizational innovation (Khalili, 2016). In theory, a supportive work climate facilitates employee creative self-efficacy or self-perceptions as a capable contributor (Mosia and Ngulube, 2005). How these attributes operate in the highly regimented banking sector is the object of this study.

Drawing on Social Cognitive Theory (SCT), which emphasizes the role of self-efficacy in human behavior (Bandura and Cervone, 1986), this study explores how responsible leadership influences creative self-efficacy and, in turn, knowledge sharing (Tantawy et al., 2021). The reciprocal determinism concept of SCT highlights the dynamic interaction between individual factors, social influences, and environmental conditions, providing a robust framework for examining these relationships in the context of Pakistani industries.

Knowledge sharing and responsible leadership

Knowledge sharing refers to the dynamic process through which individuals exchange both explicit and tacit knowledge (Kim & Yun, 2015), experiences, and insights within an organization. This process not only involves the transmission of factual information but also the sharing of personal know—how and problem-solving techniques, which enhances collective competence (Bock et al., 2005; Brown & Treviño, 2006). Such an exchange fosters innovation and adaptability by building a shared understanding that can be leveraged to address complex challenges (Ahmed et al., 2020). Moreover, effective knowledge sharing can drive continuous learning and improvement (Ellison et al., 2015), contributing to sustainable competitive advantage in fast-evolving industries (Bradshaw et al., 2015). In addition, leadership plays a pivotal role in creating an environment that encourages open communication and trust (Al Hawamdeh & AL-edenat, 2022), essential ingredients for robust knowledge exchange.

Responsible leadership, characterized by a commitment to ethical behavior, social responsibility, and sustainable decision-making, transcends traditional profit-oriented goals (Jones Christensen et al., 2014; Gotsis and Kortezi, 2008). Responsible leadership creates an environment that bolsters employees’ creative self-efficacy (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999). Leaders who demonstrate ethical practices (Doh & Quigley, 2014), transparency, and a holistic commitment to employee well-being set the stage for a culture where creativity is nurtured and valued (Maak & Pless, 2006; Tierney & Farmer, 2002). This leadership style is instrumental in fostering environments where creativity and ethical concerns are nurtured, empowering employees to develop and share innovative ideas (Walumbwa et al., 2011).

Knowledge sharing is associated with responsible leadership (Abrams et al., 2003), perhaps through promoting a culture of transparency (Cheung et al., 2013) and openness to enhance employee trust (Cabrera et al., 2006), which is critical for effective knowledge exchange (Bock et al., 2005; Brown & Treviño, 2006). Moreover, knowledge sharing in organizational teams is likely with with leadership that values information sharing (Bavik et al., 2017; Lu et al., 2019).

Creative self-efficacy mediation

Creative self-efficacy as the belief in one’s ability to generate new and innovative ideas, plays a pivotal role in fostering creativity within organizations (Puente-Díaz, 2016) involves the confidence to explore new possibilities, take calculated risks, and persist in the face of challenges (Hu and Zhao, 2016). It would flourish with knowledge sharing aimed at organizational growth (Amabile et al., 2004) and adaptability (Azeem et al., 2021). This effect could be collective learning and cross-functional collaboration (Ghobadi and D’Ambra, 2012). Moreover, employees who are confident in their creative abilities are more likely to share their ideas (Auernhammer & Hall, 2014) and insights (Gu et al., 2017), contributing to the organization’s knowledge pool (Hu and Zhao, 2016; Çakar and Ertürk, 2010). Thus, creative self-efficacy would bridge the gap between responsible leadership and knowledge sharing (Tierney & Farmer, 2002), and for unique contributions (Hung et al., 2011).

Responsible leadership would enhance employees’ belief in their creative abilities, with employees viewing their ideas as valuable contributions which would add to their active work engagement collective learning and innovation (Arshad et al., 2021; Sita Nirmala Kumaraswamy and Chitale, 2012).

A supportive workplace culture encourages employees to express their ideas without fear of retribution (Hughes et al., 2008) resulting in a culture of innovation (Edmondson, 2018). In addition, a supportive work environment leads to higher levels of creativity and problem-solving among employees (Amabile et al., 2014). Responsible leadership would be for a supportive climate by encourages employees to share their ideas and knowledge without fear of reprisal (Mayer et al., 2013). Moreover, a supportive climate enhances knowledge-sharing behavior with high creative self-efficacy (Mittal and Dhar, 2015, Černe et al., 2017).

In other words, a supportive environment would enhance the relationship between creative self-efficacy and knowledge-sharing behavior (Hu and Zhao, 2016).

The banking sector, characterized by its stringent regulatory environment and emphasis on risk management, provides a unique context in which the variables of responsible leadership, creative self-efficacy (García-Morales et al., 2009), and supportive climate are especially critical. Evidence suggests that when ethical leadership is paired with a supportive work environment, banks can foster greater knowledge sharing among employees, leading to enhanced problem solving and innovation (Lin et al., 2020; Khalili, 2016; Bock et al., 2005). Research in this area underscores that responsible leadership not only drives employee performance but also catalyzes organizational learning processes that are vital for adapting to rapid technological and market changes (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Maak & Pless, 2006).

Despite these encouraging findings, significant gaps remain. Much of the existing literature has concentrated on non-financial sectors, leaving the specific mechanisms and challenges within the banking industry underexplored (Lu et al., 2019; Voegtlin et al., 2012). For instance, while responsible leadership is generally linked to improved creative self-efficacy and knowledge sharing, the conservative and risk-averse nature of the banking sector may dampen these effects (Rhee & Choi, 2017; Hu & Zhao, 2016). Addressing this gap requires more nuanced research that examines how banking-specific factors—such as regulatory constraints, legacy systems, and cultural inertia—moderate these relationships. Understanding these sector-specific dynamics can offer deeper insights into how banks can best design leadership and climate interventions to promote innovation and competitive performance (Kim & Park, 2020).

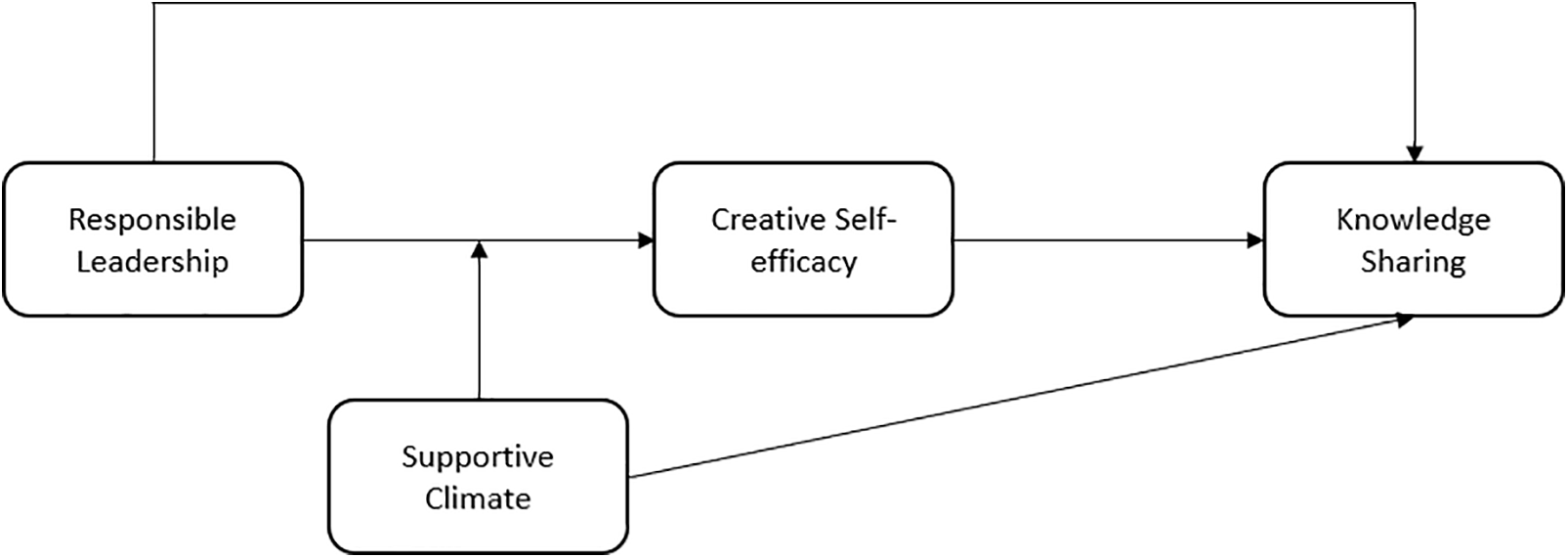

This study aims examines knowledge sharing behaviors may occur in the banking sector the interplay between responsible leadership, supportive climate and creative self-efficacy (see Figure 1). It tested the following hypotheses with data from banking sector employees:

H1: Responsible Leadership is associated with higher knowledge sharing

H2: Creative Self-efficacy mediates the relationship between Knowledge Sharing behavior and supportive organizational culture.

H3: Supportive Climate moderates the relationship between responsible leadership and creative self-efficacy so that the impact will be more substantial in a more robust supportive climate.

H4: Supportive climate has a significant direct effect on knowledge sharing, fostering a creative organizational culture where employees feel confident and motivated to share their knowledge and insights.

Figure 1: Conceptual model

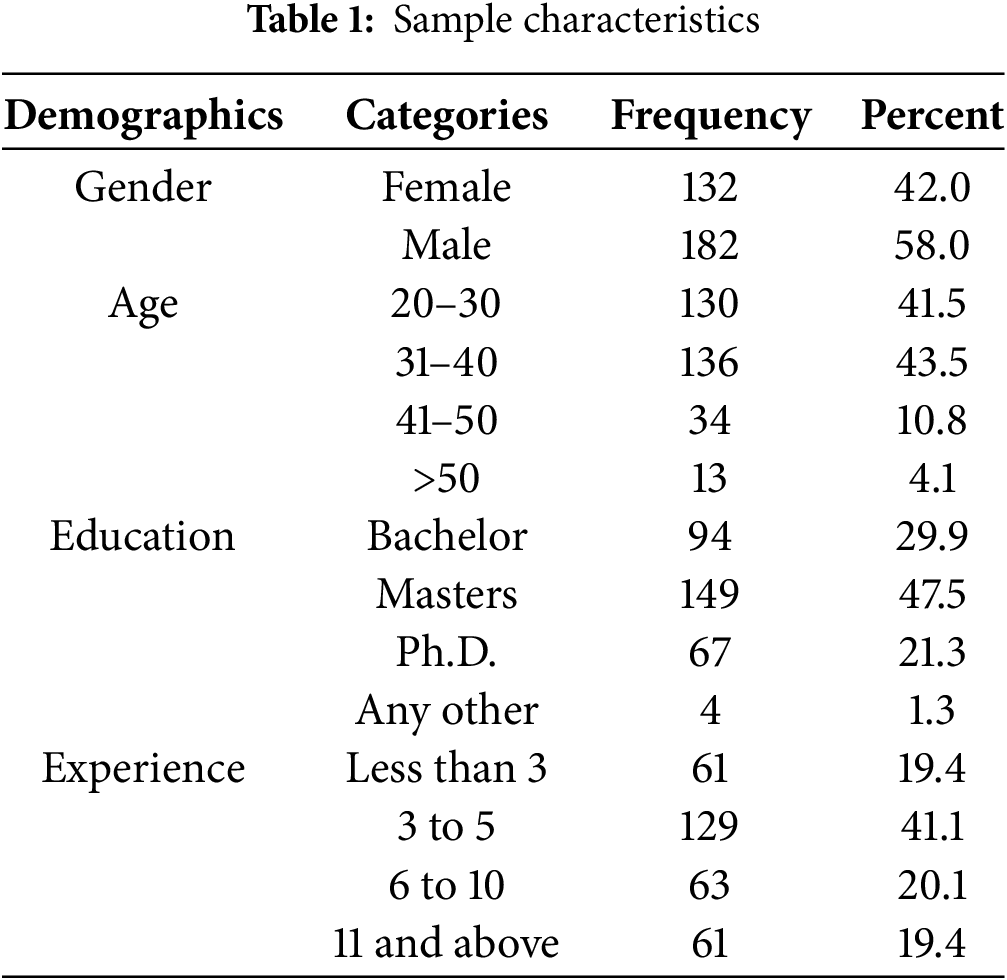

Participants were 314 participants banking sector employees (See Table 1). By gender distribution, the proportions were 51.7% men and 37.5% women. Most respondents held either Master’s or Bachelor’s degrees, and a majority had 3 to 6 years of work experience (See Table 1).

The surveys utilized a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (Strongly Disagree) to 5 (Strongly Agree), was used for quantitative data gathering (Etikan et al., 2016). Data were collected using the following scales:

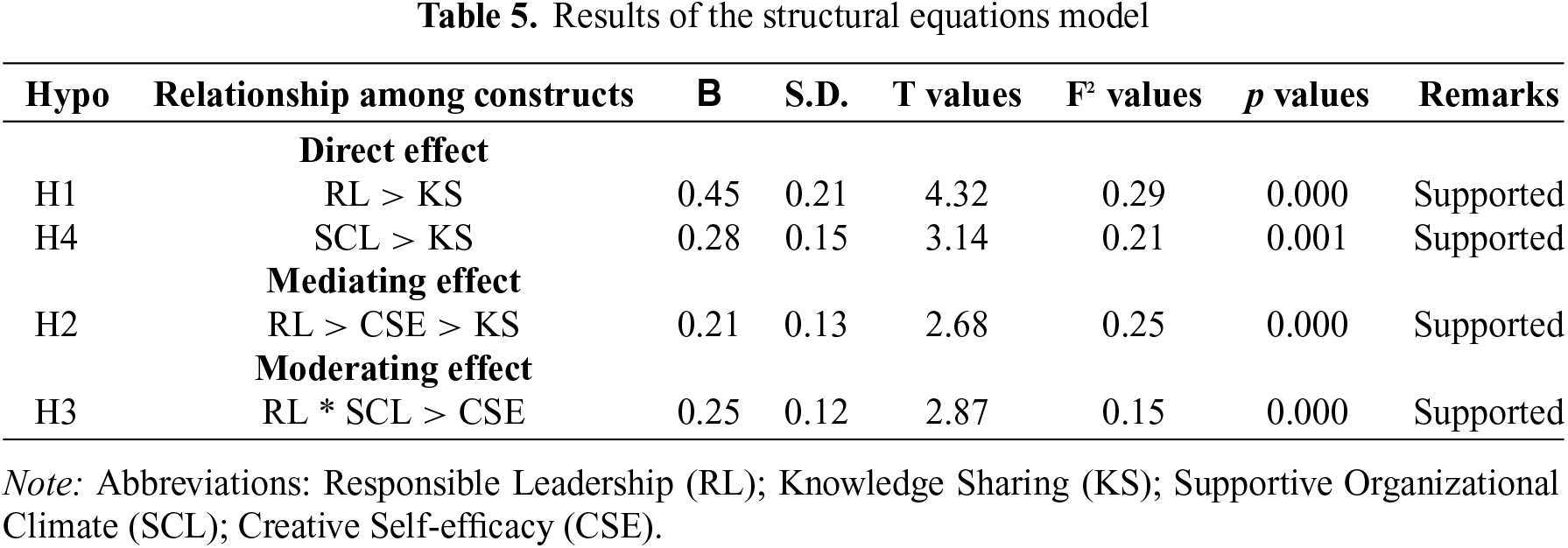

Measured by a scale developed by Voegtlin et al. (2012), this variable included 5 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale, focusing on aspects such as employee awareness and ethical behavior (e.g., “Demonstrates awareness of relevant employee claims”). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient of the scale was 0.84 (See Table 2).

Assessed using Tierney and Farmer’s (2002), scale, which originally had 6 items. For this study, 3 items were selected to focus on core aspects of creative self-efficacy, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (e.g., “I feel that I am good at generating novel ideas”). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient of the scale was 0.86 (See Table 2).

Gauged using an adapted version of Bock et al.’s (2005) scale. It consisted of 5 items on a 7-point Likert scale, measuring the extent and effectiveness of knowledge sharing within the organization (e.g., “My knowledge sharing with other organizational members is good”). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient of the scale was 0.92 (See Table 2).

Supportive organizational climate

This moderator was measured using a dimension from Rogg et al.’s (2001) scale, focusing on Managerial Considerations. It comprised 8 items on a 6-point Likert Scale, evaluating the supportive nature of the organizational climate (e.g., “Leaders follow through on commitments”). In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha (α) coefficient of the scale was 0.85 (See Table 2).

The Harbin Institute of Technology Ethics Committee approved this study. The participants consented to this study. The survey process emphasized voluntary participation, confidentiality, and the option for participants to withdraw at any time. The collected data were encrypted, anonymized, and securely coded for analysis, adhering to the ethical guidelines.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS and SmartPLS software (Purwanto, 2021). The analysis utilized regression and mediation techniques to explore the relationships among responsible leadership, creative self-efficacy, knowledge sharing, and the moderating role of a supportive climate. To address potential common method bias, Harman’s single factor test was applied, with the results showing that the sums of squared loading accounted for 14.38% of the variance, which is well below the 50% threshold, indicating that common method bias was not a significant issue in this data set (Tehseen et al., 2017).

Additionally, factor loading and convergence, discriminant validity (using the Heterotrait-Monotrait Ratio, HTMT-Ratio), and structural equation models (calculating explained predictive relevance Q2, variance R2, and effect size f2) were assessed to ensure the robustness of the measures (Hair et al., 2017).

The data was quantitatively analyzed using the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM) technique. Given that PLS-SEM does not necessitate traditional assumption tests, conventional sample data were employed for the analysis (Hair et al., 2017; Ramayah et al., 2018). This approach allowed for the direct measurement of latent variables, grounded in existing theories, and provided insights into the relationships among the study’s variables.

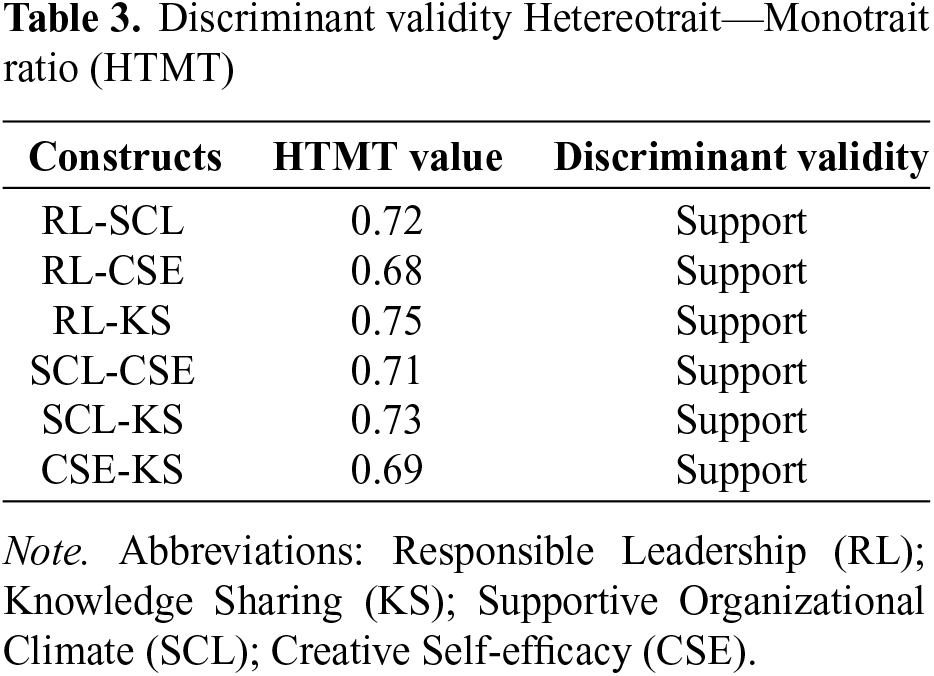

The measurement model’s convergent and discriminant validity were evaluated. Convergent validity was confirmed as all factor loadings, Composite Reliability (CR), and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values exceeded the respective cutoff thresholds (Shrestha, 2021). Specifically, factor loadings greater than 0.70 were considered significant, and no items were deleted as all contributed positively to the CR and AVE values (Hair et al., 2020). Discriminant validity was assessed using the Heterotrait-Monotrait (HTMT) ratio of correlations (Ab Hamid et al., 2017). All HTMT values were below the recommended threshold of 0.85 (Hair et al., 2020), confirming that the constructs were distinct (Cohen, 1988) and captured unique variances (See Table 3).

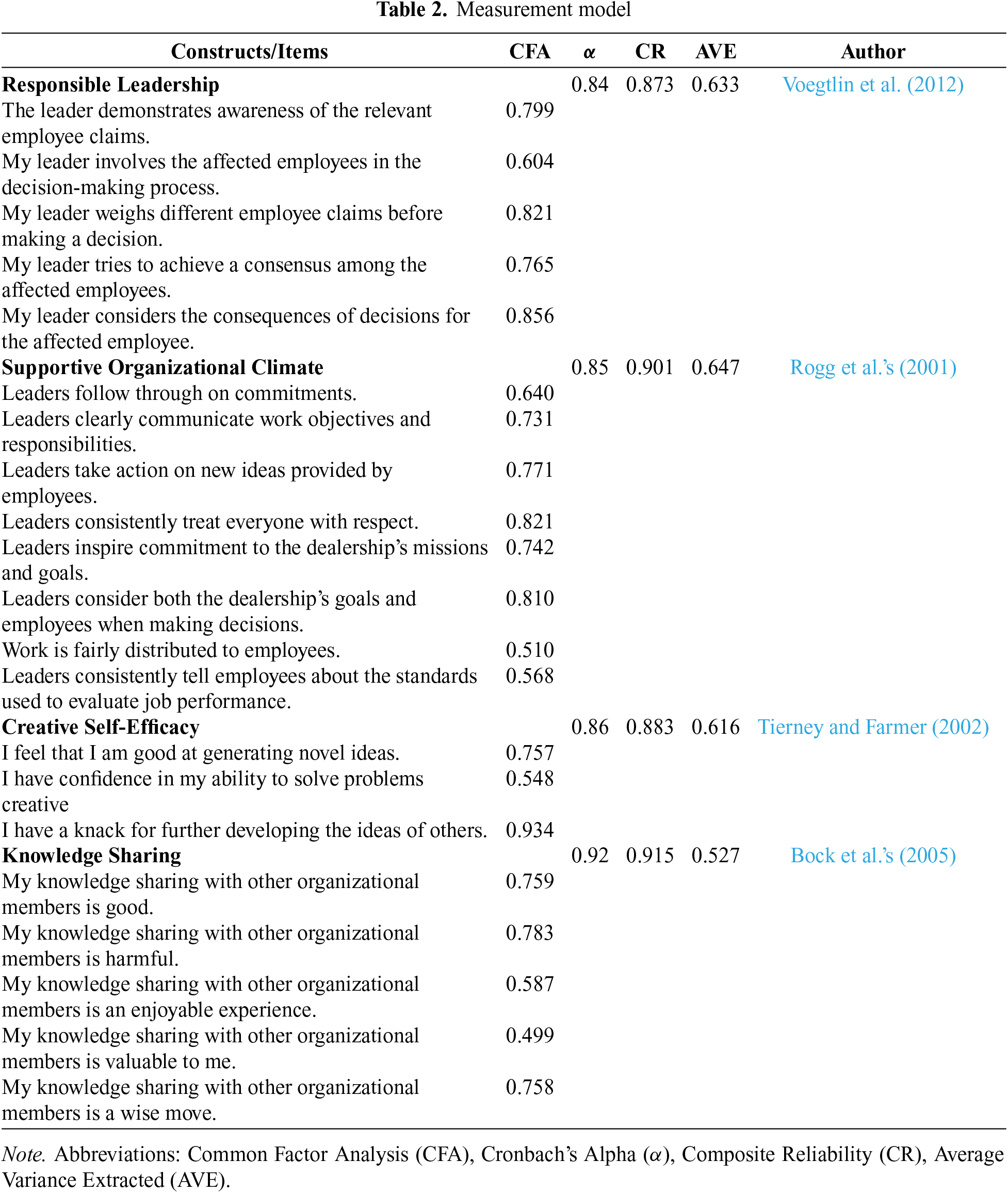

Model’s predictive relevance and variance

Cross-validated redundancy (Q2) values were used to assess the model’s predictive relevance. The Q2 values for creative self-efficacy (0.32) and knowledge sharing (0.28) were above zero, indicating strong predictive relevance. Additionally, the R2 values revealed that responsible leadership explained 25% of the variance in creative self-efficacy and 22% in knowledge sharing, while supportive climate accounted for 15% of the variance in knowledge sharing. These findings highlight the significant influence of responsible leadership and supportive climate on key organizational behaviors.

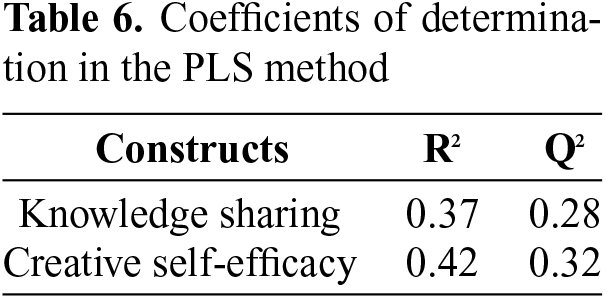

Effect sizes (f2) were computed to assess the magnitude of the independent variables’ impact on the dependent variables.

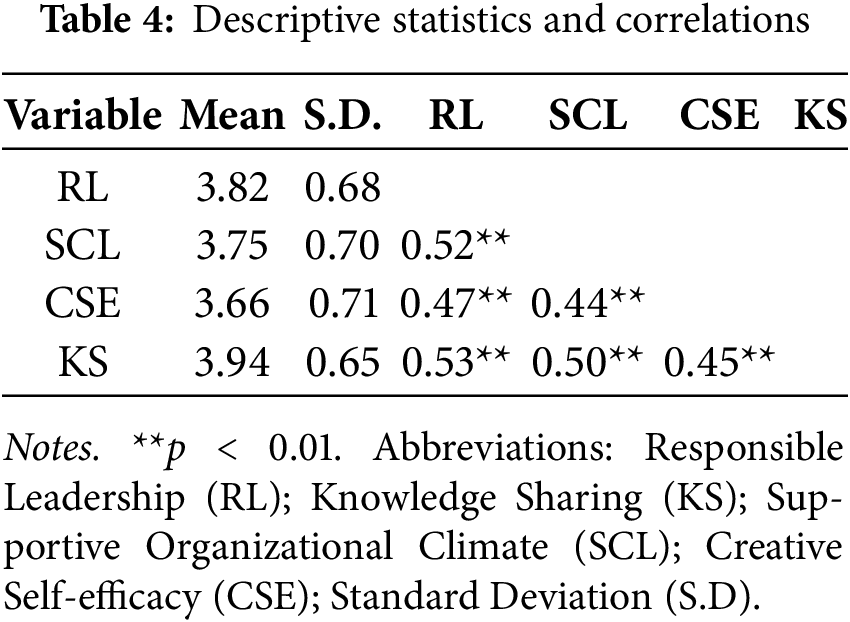

Descriptive statistics—Means and correlations

Table 4 indicates that banking employees report moderately high scores for all four constructs. Responsible Leadership has a mean of 3.82 (SD = 0.68), Supportive Climate a mean of 3.75 (SD = 0.70), Creative Self-efficacy a mean of 3.66 (SD = 0.71), and Knowledge Sharing a mean of 3.94 (SD = 0.65). The relatively small standard deviations suggest that the perceptions across respondents are fairly consistent.

The correlation matrix reveals significant positive associations among all constructs. For example, Responsible Leadership is significantly correlated with Supportive Climate (r = 0.52, p < 0.01), Creative Self-efficacy (r = 0.47, p < 0.01), and Knowledge Sharing (r = 0.53, p < 0.01). Likewise, Supportive Climate is significantly associated with Creative Self-efficacy (r = 0.44, p < 0.01) and Knowledge Sharing (r = 0.50, p < 0.01), while Creative Self-efficacy is significantly related to Knowledge Sharing (r = 0.45, p < 0.01).

These results support the theoretical framework of the study, suggesting that a positive leadership approach combined with a supportive organizational climate not only boosts employees’ confidence in their creative abilities but also enhances their willingness to share knowledge. This is consistent with prior research showing that ethical leadership and a nurturing work environment play critical roles in promoting both individual creativity and collaborative knowledge-sharing behaviors (Bock et al., 2005; Brown & Treviño, 2006)

Responsible leadership effects

Responsible leadership showed substantial effects on knowledge sharing (f2 = 0.29). Similarly, the supportive climate had a considerable effect on knowledge sharing (f2 = 0.21) and its mediating effect between responsible leadership and knowledge sharing was significant (f2 = 0.25). The moderating effect of the supportive climate also demonstrated a significant impact (f2 = 0.15) (See Table 5, indicating its amplifying role in the relationship between responsible leadership and knowledge sharing.

The direct effects of responsible leadership on creative self-efficacy (β = 0.39, p < 0.001) and knowledge sharing (β = 0.45, p < 0.001) were significant, as was the effect of the supportive climate on knowledge sharing (β = 0.28, p < 0.002) (See Table 5) indicating that the hypothesis was supported.

Creative self-efficacy mediation and supportive climate moderation. Creative self-efficacy strongly affected knowledge sharing (β = 0.32, p < 0.001).

The mediating role of creative self-efficacy in the relationship between responsible leadership and knowledge sharing was substantial (indirect effect = 0.21, p < 0.001), indicating that the hypothesis was supported. Furthermore, the moderating effect of the supportive climate on the relationship between responsible leadership and creative self-efficacy was significant (β = 0.25, p < 0.001) (See Table 5), indicating that the hypothesis was supported.

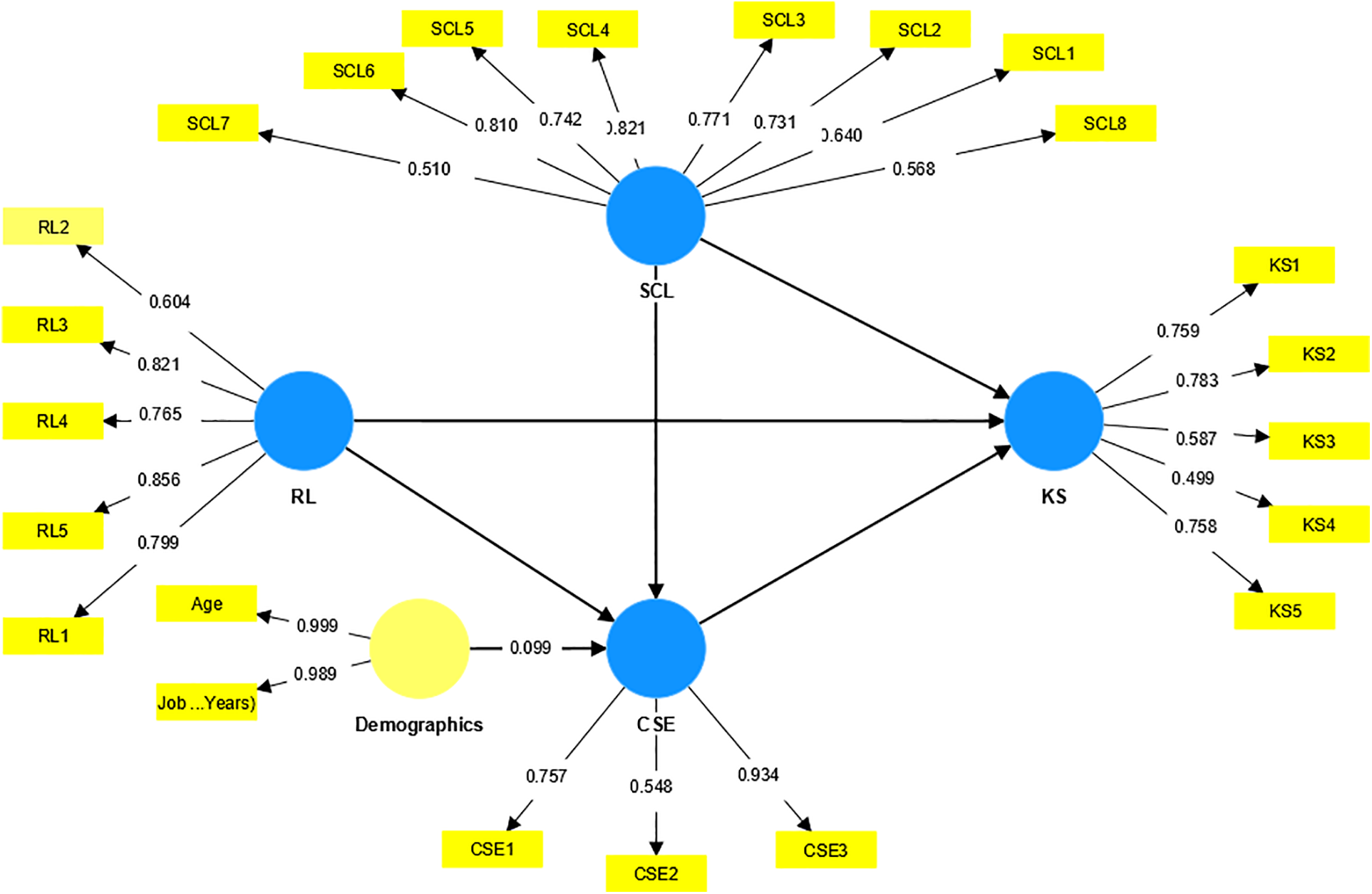

These results in Figure 2 demonstrates the substantial direct, indirect, and moderating impacts of responsible leadership and supportive climate on fostering creative self-efficacy and knowledge-sharing behaviors. The findings provide robust evidence of the intricate interplay among these constructs within the organizational context of the banking sector).

Figure 2: Structural equation modelling

Table 6 indicates that the model explains 37% of the variance in knowledge sharing and 42% of the variance in creative self-efficacy, demonstrating substantial explanatory power of the included constructs. The Q2 values, at 0.28 for knowledge sharing and 0.32 for creative self-efficacy, further affirm the model’s predictive relevance, suggesting that the constructs have strong potential to forecast outcomes in similar contexts. These coefficients of determination imply that responsible leadership, along with supportive climate and creative self-efficacy, plays a critical role in shaping knowledge sharing behaviors among banking employees. This outcome is consistent with previous research that has highlighted the central role of leadership and environmental factors in organizational learning and innovation (Hair et al., 2017; Shrestha, 2021). Additionally, the substantial R2 values offer practical insights for practitioners, suggesting that interventions targeting these variables could yield considerable improvements in knowledge management practices. Overall, the findings validate the proposed model and encourage further investigation into how these dynamics operate in various organizational settings.

The study found that responsible leadership has a positive and significant influence on employees’ knowledge-sharing behavior. In other words, bank employees who perceive their leaders as more responsible and ethical tend to share knowledge more freely. This result aligns with prior research showing that leadership which promotes transparency (Nonaka & Takeuchi, 1995) and trust fosters greater knowledge exchange among followers (Brown & Treviño, 2006; Lin et al., 2020). Even in the traditionally conservative banking sector, responsible leadership proved effective in encouraging knowledge sharing—a finding that contrasts with concerns that rigid, risk-averse climates might dampen leadership’s impact on such behaviors (Rhee & Choi, 2017). One explanation is that responsible leaders create an environment of mutual trust and openness, signaling to employees that sharing ideas and information is safe and valued. By emphasizing ethical conduct and stakeholder well-being, these leaders reduce employees’ fear of negative repercussions and inspire a sense of purpose (Zhao et al., 2023), which in turn motivates staff to contribute their knowledge for the organization’s benefit. Thus, effective responsible leadership can overcome sectoral barriers by cultivating a pro-sharing culture built on trust and ethical values.

The second key finding was that employees’ creative self-efficacy partially mediates the relationship between responsible leadership and knowledge sharing. Responsible leadership was associated with higher creative self-efficacy in employees (Slåtten, 2014), which in turn led to greater knowledge-sharing behavior. This mediated pattern is similar to observations in prior studies on empowering or transformational leadership, where leader support boosts followers’ self-belief and thereby promotes proactive outcomes (Shin & Zhou, 2007; Tierney & Farmer, 2002). It extends those findings to the domain of knowledge management: whereas previous research linked creative self-efficacy mainly to creative performance, our results show it also plays a crucial role in facilitating knowledge exchange. The explanation for this finding lies in how responsible leaders influence employees’ mindsets. By providing encouragement, autonomy, and recognition, a responsible leader helps employees feel more confident in their creative abilities. Social cognitive theory suggests that such elevated self-efficacy makes individuals more likely to initiate and persist in behaviors like sharing novel ideas or expertise. In practice, an employee who believes in the value of their knowledge (thanks to leader support) is more inclined to voice suggestions, best practices, or improvements. This finding highlights creative self-efficacy as an important psychological mechanism through which a supportive leadership style translates into higher knowledge sharing. Notably, the mediation was partial rather than full-indicating that while bolstering employees’ self-confidence is a key pathway, responsible leaders may also influence knowledge sharing through other routes (e.g., directly shaping norms of open communication).

The third finding confirmed that a supportive organizational climate significantly moderates the effect of responsible leadership on creative self-efficacy. The positive impact of responsible leadership on an employee’s creative self-confidence was stronger in the presence of a more supportive, innovation-friendly climate. This result is consistent with the idea that leadership and context work in tandem to shape employee attitudes. When the broader work climate encourages creativity, learning, and open exchange, it amplifies the influence of a responsible leader’s behavior on employees’ beliefs. Our finding echoes evidence that pairing an ethical or empowering leadership style with a supportive environment yields especially strong outcomes in terms of employee motivation and knowledge behaviors (Mittal & Dhar, 2015; Lin et al., 2020). A plausible explanation is that a supportive climate provides congruent cues and resources that reinforce the leader’s messages. Under a robust supportive climate, employees receive consistent encouragement from both their immediate leader and the organizational culture (Ng & Lucianetti, 2016), which accelerates their confidence to experiment and share ideas (Srivastava et al., 2006). In contrast, if the climate is unsupportive or discourages risk-taking, even a well-intentioned leader’s efforts might be undermined by prevailing norms of silence or caution. Thus, a “climate–leadership fit” is critical: a workplace environment that echoes the leader’s responsible values creates a synergistic effect, empowering employees to fully believe in their creative capabilities. Rather than substituting for leadership, a supportive climate complements it-together they ensure that employees feel genuinely safe and empowered to contribute, thereby enhancing creative self-efficacy and subsequent knowledge sharing.

The fourth key finding was that a supportive organizational climate itself has a significant direct effect on knowledge-sharing behavior. Employees in the banking sector who reported a more supportive, open climate were more likely to engage in sharing knowledge and ideas with colleagues. This outcome is highly consistent with previous studies highlighting the importance of organizational climate and culture for knowledge management (Nguyen & Malik, 2022). A climate characterized by trust, cooperation, and support has been shown to facilitate knowledge sharing in a variety of settings (Khalili, 2016; Al-Alawi et al., 2007). Our study reinforces that principle and extends it to the context of banking: even in an industry often seen as hierarchical and formal, creating a supportive climate markedly encourages employees to disseminate information and expertise. The likely explanation is that a supportive climate fosters psychological safety – employees feel secure in sharing their insights without fear of ridicule or reprisal. When management and peers openly value knowledge exchange (for example, through encouragement and recognition of shared ideas), individuals are intrinsically motivated to contribute what they know (Taştan & Davoudi, 2019). This aligns with the notion that “it takes a village” to encourage proactive behaviors (Mayer et al., 2013); an organization’s collective norms and support systems strongly influence personal willingness to speak up or share. In practice, a supportive climate might include clear policies rewarding collaboration, leadership that listens to new ideas, and an atmosphere of mutual respect. Such conditions directly lower the barriers to knowledge sharing by assuring employees that their input is welcome and beneficial (Tu et al., 2017). Consequently, the presence of a supportive climate leads to more frequent and free knowledge exchanges (Wiig, 2012). This finding underscores that beyond individual leadership actions, the general work environment plays a pivotal role in knowledge-sharing outcomes. For banks and similar organizations, investing in a supportive, knowledge-friendly climate (e.g., through team-building, open communication channels, and innovation encouragement) can significantly boost the circulation of knowledge and drive organizational learning.

Implications for theory and practice

Theoretically, this study extends Social Cognitive Theory by demonstrating that responsible leadership and supportive climate act as critical environmental factors shaping employees’ creative self-efficacy and knowledge-sharing behaviors. While SCT traditionally emphasizes individual agency and self-efficacy, our findings reveal that ethical leadership practices and organizational climates are equally vital in fostering cognitive and behavioral outcomes. This bridges a gap in SCT by contextualizing its principles within leadership and organizational dynamics, offering a more holistic framework for future research. By interlinking responsible leadership with creative self-efficacy and knowledge sharing, we offer a more comprehensive understanding of how ethical and transparent leadership practices can yield a multiplicative effect on organizational innovation and collaboration.

The findings provide a nuanced view of Social Cognitive Theory (SCT) in a corporate setting, extending its applicability beyond individual behavior to encompass organizational dynamics. By integrating responsible leadership into the SCT framework, this research highlights how leadership styles can influence employees’ self-perception and motivation, thereby impacting their behavior in the workplace. This integration offers a novel perspective on SCT, suggesting that leadership can be a significant environmental factor that shapes cognitive processes and behaviors.

For practitioners, banks should prioritize leadership development programs that emphasize ethical decision-making, transparency, and employee empowerment. For instance, training managers to adopt responsible leadership behaviors—such as involving employees in decision-making and addressing societal impacts—can enhance creative self-efficacy. Additionally, fostering a supportive climate through open communication channels, recognition of innovative ideas, and psychological safety protocols (e.g., anonymous suggestion systems) can amplify knowledge sharing. Policymakers in the banking sector could mandate annual audits of workplace climate to ensure alignment with these practices. Additionally, the study underscores the importance of a supportive climate as a critical contextual factor in enhancing the effectiveness of leadership styles. This finding extends the SCT by illustrating how organizational climate interacts with personal and behavioral factors. It suggests that for leadership to be truly effective in promoting creativity and knowledge sharing, it must be complemented by an environment that supports and nurtures these behaviors.

For practitioners and policymakers, these insights emphasize the need for leadership development programs that focus not only on ethical decision-making but also on fostering environments that encourage creative thinking and knowledge exchange. Organizations should consider how their climate can be shaped to support the positive effects of responsible leadership, such as through policies that promote open communication and psychological safety.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

The study’s reliance on a specific sector and region may limit the generalizability of its findings. Future research could explore these dynamics in different sectors or cultural contexts to verify the applicability of the findings more broadly. Given the self-reported nature of the data, the potential for common method variance suggests a need for future studies to incorporate more diverse data sources, such as observational or qualitative data, to enrich the understanding and mitigate any biases.

Our findings reveal that responsible leadership is a key driver of knowledge sharing, influencing it both directly and indirectly through its impact on creative self-efficacy. The role of a supportive climate as a moderator further underscores its importance in creating an environment conducive to knowledge exchange and innovation.

The research highlights the mediating effect of creative self-efficacy, shedding light on how employees’ belief in their creative capabilities is shaped by responsible leadership and, in turn, influences their knowledge-sharing behaviors. The study also identifies the supportive climate’s critical role in strengthening the relationship between responsible leadership and knowledge sharing. These nuanced relationships enrich our understanding of the factors that foster a thriving knowledge-sharing culture within organizations.

From a theoretical perspective, this study adds to the literature on responsible leadership and organizational behavior, offering a deeper understanding of how leadership styles and organizational climate interact to impact employee behavior and organizational outcomes. The integration of these concepts provides a comprehensive framework that can guide future research in similar contexts. For practitioners and policymakers, the study underscores the importance of fostering responsible leadership practices and nurturing a supportive climate to encourage knowledge sharing and innovation. In the competitive landscape of the banking sector, these elements are crucial for promoting a culture of continuous learning and adaptability.

In conclusion, embracing responsible leadership and cultivating a supportive organizational climate can significantly contribute to creating a dynamic, collaborative, and innovative workforce. This approach is essential for organizations aiming to navigate the challenges of the modern business environment and achieve sustainable growth and success.

Acknowledgement: We would like to thank Harbin Institute of Technology for helping us with furthering our work.

Funding Statement: There was no funding provided for this research.

Author Contributions: Study Conception and Design: Ali Hasan Mumtaz, Li Zhang; Data Collection: Ali Hasan Mumtaz; Analysis and Interpretation: Ali Hasan Mumtaz, Ziyi Huang; Supervision: Li Zhang; Draft Manuscript: Ali Hasan Mumtaz, Ziyi Huang; Revision: Jiajing Wang, Gavaa Zanabazar. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of Harbin Institute of Technology.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ab Hamid, M. R., Sami, W., & Sidek, M. M. (2017). Discriminant validity assessment: Use of Fornell & Larcker criterion versus HTMT criterion. Journal of Physics: Conference Series, 890(1), 012163. [Google Scholar]

Abrams, L. C., Cross, R., Lesser, E., & Levin, D. Z. (2003). Nurturing interpersonal trust in knowledge-sharing networks. Academy of Management Perspectives, 17(4), 64–77. [Google Scholar]

Ahmed, T., Khan, M. S., Thitivesa, D., Siraphatthada, Y., & Phumdara, T. (2020). Impact of employees’ engagement and knowledge sharing on organizational performance: Study of HR challenges in COVID-19 pandemic. Human Systems Management, 39(4), 589–601. [Google Scholar]

Al Hawamdeh, N., & AL-edenat, M. (2022). Investigating the moderating effect of humble leadership behaviour on motivational factors and knowledge-sharing intentions: Evidence from Jordanian public organisations. VINE Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, 54(2), 280–298. [Google Scholar]

Al-Alawi, A. I., Al-Marzooqi, N. Y., & Mohammed, Y. F. (2007). Organizational culture and knowledge sharing: Critical success factors. Journal of Knowledge Management, 11(2), 22–42. [Google Scholar]

Aly, W. O. (2016). The learning organization: A foundation to enhance the sustainable competitive advantage of the service sector in Egypt. Journal of Public Management Research, 2(2), 37–62. [Google Scholar]

Amabile, T., Fisher, C. M., & Pillemer, J. (2014). IDEO’s culture of helping. Harvard Business Review, 92(1), 54–61. [Google Scholar]

Amabile, T. M., Schatzel, E. A., Moneta, G. B., & Kramer, S. J. (2004). Leader behaviors and the work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 5–32. [Google Scholar]

Arshad, M., Yu, C. K., Qadir, A., Ahmad, W., & Xie, C. (2021). The moderating role of knowledge sharing and mediating role of employee creative self-efficacy on the association of empowering leadership and employee creativity. International Journal of Management Practice, 14(6), 660–681. [Google Scholar]

Auernhammer, J., & Hall, H. (2014). Organizational culture in knowledge creation, creativity and innovation: Towards the Freiraum model. Journal of Information Science, 40(2), 154–166. [Google Scholar]

Azeem, M., Ahmed, M., Haider, S., & Sajjad, M. (2021). Expanding competitive advantage through organizational culture, knowledge sharing and organizational innovation. Technology in Society, 66, 101635. [Google Scholar]

Bandura, A., & Cervone, D. (1986). Differential engagement of self-reactive influences in cognitive motivation. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 38(1), 92–113. [Google Scholar]

Bass, B. M., & Steidlmeier, P. (1999). Ethics, character, and authentic transformational leadership behavior. The Leadership Quarterly, 10(2), 181–217. [Google Scholar]

Bavik, A., Bavik, Y. L., & Tang, P. M. (2017). Servant leadership, employee job crafting, and citizenship behaviors: A cross-level investigation. Cornell Hospitality Quarterly, 58(4), 364–373. [Google Scholar]

Bock, G. W., Zmud, R. W., Kim, Y. G., & Lee, J. N. (2005). Behavioral intention formation in knowledge sharing: Examining the roles of extrinsic motivators, social-psychological forces, and organizational climate. MIS Quarterly, 29(1), 87–111. [Google Scholar]

Bradshaw, R., Chebbi, M., & Oztel, H. (2015). Leadership and knowledge sharing. Asian Journal of Business Research, 4(3). [Google Scholar]

Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. [Google Scholar]

Cabrera, A., Collins, W. C., & Salgado, J. F. (2006). Determinants of individual engagement in knowledge sharing. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 17(2), 245–264. [Google Scholar]

Çakar, N. D., & Ertürk, A. (2010). Comparing innovation capability of small and medium-sized enterprises: Examining the effects of organizational culture and empowerment. Journal of Small Business Management, 48(3), 325–359. [Google Scholar]

Cheung, C. M., Lee, M. K., & Lee, Z. W. (2013). Understanding the continuance intention of knowledge sharing in online communities of practice through the post-knowledge-sharing evaluation processes. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 64(7), 1357–1374. [Google Scholar]

Černe, M., Hernaus, T., Dysvik, A., & Škerlavaj, M. (2017). The role of multilevel synergistic interplay among team mastery climate, knowledge hiding, and job characteristics in stimulating innovative work behavior. Human Resource Management Journal, 27(2), 281–299. [Google Scholar]

Cohen, J. (1988). Set correlation and contingency tables. Applied Psychological Measurement, 12(4), 425–434. [Google Scholar]

Doh, J. P., & Quigley, N. R. (2014). Responsible leadership and stakeholder management: Influence pathways and organizational outcomes. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(3), 255–274. [Google Scholar]

Edmondson, A. C. (2018). The fearless organization: Creating psychological safety in the workplace for learning, innovation, and growth. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

Ellison, N. B., Gibbs, J. L., & Weber, M. S. (2015). The use of enterprise social network sites for knowledge sharing in distributed organizations: The role of organizational affordances. American Behavioral Scientist, 59(1), 103–123. [Google Scholar]

Etikan, I., Musa, S. A., & Alkassim, R. S. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1–4. [Google Scholar]

García-Morales, V. J., Verdú-Jover, A. J., & Lloréns, F. J. (2009). The influence of CEO perceptions on the level of organizational learning: Single-loop and double-loop learning. International Journal of Manpower, 30(6), 567–590. [Google Scholar]

Ghobadi, S., & D’Ambra, J. (2012). Knowledge sharing in cross-functional teams: A coopetitive model. Journal of Knowledge Management, 16(2), 285–301. [Google Scholar]

Gotsis, G., & Kortezi, Z. (2008). Philosophical foundations of workplace spirituality: A critical approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 78, 575–600. [Google Scholar]

Greige Frangieh, C., & Khayr Yaacoub, H. (2017). A systematic literature review of responsible leadership: Challenges, outcomes and practices. Journal of Global Responsibility, 8(2), 281–299. [Google Scholar]

Gu, J., He, C., & Liu, H. (2017). Supervisory styles and graduate student creativity: The mediating roles of creative self-efficacy and intrinsic motivation. Studies in Higher Education, 42(4), 721–742. [Google Scholar]

Hair, J., Hollingsworth, C. L., Randolph, A. B., & Chong, A. Y. L. (2017). An updated and expanded assessment of PLS-SEM in information systems research. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 117(3), 442–458. [Google Scholar]

Hair, Jr, J. F., Nitzl, C., & Nitzl, C. (2020). Assessing measurement model quality in PLS-SEM using confirmatory composite analysis. Journal of Business Research, 109, 101–110. [Google Scholar]

Holdren, J. P., Ehrlich, P. R., Ehrlich, A., Stahl, G., Lang, B. et al. (1986). Nuclear weapons and the future of humanity: The fundamental questions. Rowman & Littlefield Publisher. [Google Scholar]

Hu, B., & Zhao, Y. (2016). Creative self-efficacy mediates the relationship between knowledge sharing and employee innovation. Social Behavior and Personality, 44(5), 815–826. [Google Scholar]

Hughes, L. W., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2008). A study of supportive climate, trust, engagement and organizational commitment. Journal of Business & Leadership: Research, Practice, and Teaching (2005–2012), 4(2), 51–59. [Google Scholar]

Hung, S. Y., Durcikova, A., Lai, H. M., & Lin, W. M. (2011). The influence of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation on individuals’ knowledge sharing behavior. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 69(6), 415–427. [Google Scholar]

Jones Christensen, L. I. S. A., Mackey, A., & Whetten, D. (2014). Taking responsibility for corporate social responsibility: The role of leaders in creating, implementing, sustaining, or avoiding socially responsible firm behaviors. Academy of Management Perspectives, 28(2), 164–178. [Google Scholar]

Khalili, A. (2016). Linking transformational leadership, creativity, innovation, and innovation-supportive climate. Management Decision, 54(9), 2277–2293. [Google Scholar]

Kim, E. J., & Park, S. (2020). Transformational leadership, knowledge sharing, organizational climate and learning: An empirical study. Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 41(6), 761–775. [Google Scholar]

Kim, S. L., & Yun, S. (2015). The effect of coworker knowledge sharing on performance and its boundary conditions: An interactional perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 100(2), 575–587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Lin, C. P., Huang, H. T., & Huang, T. Y. (2020). The effects of responsible leadership and knowledge sharing on job performance among knowledge workers. Personnel Review, 49(9), 1879–1896. [Google Scholar]

Lu, X., Zhou, H., & Chen, S. (2019). Facilitate knowledge sharing by leading ethically: The role of organizational concern and impression management climate. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34, 539–553. [Google Scholar]

Maak, T., & Pless, N. M. (2006). Responsible leadership in a stakeholder society-a relational perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 66, 99–115. [Google Scholar]

Mayer, D. M., Nurmohamed, S., Treviño, L. K., Shapiro, D. L., & Schminke, M. (2013). Encouraging employees to report unethical conduct internally: It takes a village. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 121(1), 89–103. [Google Scholar]

Mittal, S., & Dhar, R. L. (2015). Transformational leadership and employee creativity: Mediating role of creative self-efficacy and moderating role of knowledge sharing. Management Decision, 53(5), 894–910. [Google Scholar]

Mosia, L. N., & Ngulube, P. (2005). Managing the collective intelligence of local communities for the sustainable utilisation of estuaries in the Eastern Cape, South Africa. South African Journal of Libraries and Information Science, 71(2), 175–186. [Google Scholar]

Ng, T. W., & Lucianetti, L. (2016). Within-individual increases in innovative behavior and creative, persuasion, and change self-efficacy over time: A social-cognitive theory perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 101(1), 14–25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Nguyen, T. M., & Malik, A. (2022). Impact of knowledge sharing on employees’ service quality: The moderating role of artificial intelligence. International Marketing Review, 39(3), 482–508. [Google Scholar]

Nonaka, I., & Takeuchi, H. (1995). The knowledge-creating company. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

Puente-Díaz, R. (2016). Creative self-efficacy: An exploration of its antecedents, consequences, and applied implications. The Journal of Psychology, 150(2), 175–195. [Google Scholar]

Purwanto, A. (2021). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) analysis for social and management research: A literature review. Journal of Industrial Engineering & Management Research, 2(4), 114–123. [Google Scholar]

Ramayah, T., Cheah, J., Chuah, F., Ting, H., & Memon, M. A. (2018). Partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) using SmartPLS 3.0: an updated guide and practical guide to statistical analysis. Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Pearson. [Google Scholar]

Rhee, Y. W., & Choi, J. N. (2017). Knowledge management behavior and individual creativity: Goal orientations as antecedents and in-group social status as moderating contingency. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 38(6), 813–832. [Google Scholar]

Rogg, K. L., Schmidt, D. B., Shull, C., & Schmitt, N. (2001). Human resource practices, organizational climate, and customer satisfaction. Journal of Management, 27(4), 431–449. [Google Scholar]

Shrestha, N. (2021). Factor analysis as a tool for survey analysis. American Journal of Applied Mathematics and Statistics, 9(1), 4–11. [Google Scholar]

Sita Nirmala Kumaraswamy, K., & Chitale, C. M. (2012). Collaborative knowledge sharing strategy to enhance organizational learning. Journal of Management Development, 31(3), 308–322. [Google Scholar]

Slåtten, T. (2014). Determinants and effects of employee’s creative self-efficacy on innovative activities. International Journal of Quality and Service Sciences, 6(4), 326–347. [Google Scholar]

Srivastava, A., Bartol, K. M., & Locke, E. A. (2006). Empowering leadership in management teams: Effects on knowledge sharing, efficacy, and performance. Academy of Management Journal, 49(6), 1239–1251. [Google Scholar]

Tantawy, M., Herbert, K., McNally, J. J., Mengel, T., Piperopoulos, P. et al. (2021). Bringing creativity back to entrepreneurship education: Creative self-efficacy, creative process engagement, and entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 15, e00239. [Google Scholar]

Taştan, S. B., & Davoudi, S. M. M. (2019). The relationship between socially responsible leadership and organisational ethical climate: In search for the role of leader’s relational transparency. International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics, 13(3), 275–299. [Google Scholar]

Tehseen, S., Ramayah, T., & Sajilan, S. (2017). Testing and controlling for common method variance: A review of available methods. Journal of Management Sciences, 4(2), 142–168. [Google Scholar]

Tierney, P., & Farmer, S. M. (2002). Creative self-efficacy: Its potential antecedents and relationship to creative performance. Academy of Management Journal, 45(6), 1137–1148. [Google Scholar]

Tu, Y., Lu, X., & Yu, Y. (2017). Supervisors’ ethical leadership and employee job satisfaction: A social cognitive perspective. Journal of Happiness Studies, 18, 229–245. [Google Scholar]

Voegtlin, C., Patzer, M., & Scherer, A. G. (2012). Responsible leadership in global business: A new approach to leadership and its multi-level outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 105, 1–16. [Google Scholar]

Walumbwa, F. O., Christensen, A. L., & Hailey, F. (2011). Authentic leadership and the knowledge economy: Sustaining motivation and trust among knowledge workers. Organizational Dynamics, 40(2), 110–118. [Google Scholar]

Wiig, K. (2012). People-focused knowledge management. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

Zhao, L., Yang, M. M., Wang, Z., & Michelson, G. (2023). Trends in the dynamic evolution of corporate social responsibility and leadership: A literature review and bibliometric analysis. Journal of Business Ethics, 182(1), 135–157. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools