Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Parental psychological control and cyberbullying in vocational college students: The role of the moral disengagement and the dual system of self-control

1 School of Education, Fujian Polytechnic Normal University, Fuzhou, 350000, China

2 Department of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, China

3 Military Psychology Section, Logistics University of PAP, Tianjin, 300309, China

4 Military Mental Health Services & Research Center, Tianjin, 300309, China

5 School of Basic Medicine, Air Force Medical University, Xi’an, 710032, China

6 Innovation Research Institute, Xijing Hospital, Air Force Medical University, Xi’an, 710032, China

7 School of Nursing, Putian University, Putian, 351100, China

* Corresponding Author: Qingyi Wang. Email:

# Huaibin Jiang and Huihang Qin are co-first authors

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(3), 355-360. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.067170

Received 01 December 2024; Accepted 04 April 2025; Issue published 31 July 2025

Abstract

This study examined the role of moral disengagement dual system of self-control in the relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying. Participants were involved 802 vocational college students (46.01% females; M = 18.11, SD = 1.23). They completed measures on parental psychological control, moral disengagement, dual system of self-control (impulse and control system), and cyberbullying. The results from mediation-moderation analysis indicated that parental psychological control directly predicts higher cyberbullying. Specifically, moral disengagement partially mediated this relationship, as higher parental psychological control increases moral disengagement, which in turn elevates the risk of cyberbullying. Furthermore, parental psychological control moderated the relationship between parental control and cyberbullying through impulse control systems within the dual system of self-control. Individuals with high impulsivity scores are more likely to engage in cyberbullying when exposed to high levels of parental psychological control, whereas individuals with low impulsivity scores exhibit a lower incidence of cyberbullying.Keywords

Parents are key to the development and maturation of emerging adults, such as college students. However, in the digital age, college students have recourse to the convenience and abundance of information available on the Internet outside direct parental control. They carry the risk of cyberbullying in their digital lives both as perpetrators and victims of cyberbullying, for example. Nonetheless, how young adults relate to their parents may explain, in part, their cyber lives, perhaps by their moral engagement and sense of control. Family dynamics, particularly parental psychological control, significantly influence children’s moral development and social adjustment (Bornstein et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023). The General Aggressive Model states that individual factors and situational factors (such as negative parenting) will affect individual aggressive behavior through the process of cognition and arousal (DeWall et al., 2011). According to the General Aggression Model, parental psychological control would be associated with higher cyberbullying through moral disengagement. This study aimed to explore the role of moral disengagement dual system of self-control in the relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying.

Parental psychological control and cyberbullying

Parental psychological control refers to the degree of authority over their children (Scharf & Goldner, 2018). Depending on the cultural context, it may involve inducing guilt, withdrawing affection, expressing disappointment, and employing tactics like humiliation or neglect. However, excessive control would interfere with the young adult’s growing need for autonomy, which could lead to defiance and/or engagement in cyberbullying (Geng et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022b). Research indicates a correlation between parental control and problematic internet use among college students, potentially exacerbating cyberbullying tendencies (Liang et al., 2024; Méndez et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2022a). Consequently, parental psychological control may directly impacts vocational college students’ cyberbullying.

Moral disengagement as a mediator

Moral disengagement is a unique cognitive tendency where individuals reinterpret their actions to lessen perceived harm, reduce moral responsibility, and dampen empathy towards victims (Bandura, 1999). On the one hand, excessive parental control can push children to moral disengagement in order to avoid blame and punishment, which in turn affects their moral decision-making. On the other hand, positive parenting can mitigate moral disengagement and cyberbullying (Zhang et al., 2021).

Moral disengagement can alleviate feelings of self-blame and guilt associated with unethical behavior (Bandura, 2002). Studies also indicate that moral disengagement predicts cyberbullying, with individuals displaying higher moral disengagement more likely to engage in cyberbullying (Li et al, 2023; Zhao & Yu, 2021). Therefore, this study explored the mediating role of moral disengagement between parental control and cyberbullying among vocational college students.

Self-control is the ability of an individual to autonomously regulate behavior to match self- or social expectations and to make long-term plans (Baumeister et al., 2007). The dual-systems theory of self-control proposed two interacting components: the impulse system and the control (adherence) system (Friese & Hofmann, 2009). The impulsive system is automated by emotions, novelty, and rewards, while the control (adhrerence) system is a higher-order process for emotion regulation and decision-making (Friese & Hofmann, 2009). Those with poor impulse control are predisposed to cyberbullying compared to those with adherence mastery (Shi et al., 2020). Individuals with high scores on the impulsive system are characterized by impulsivity, easy distractibility, and low delayed gratification and may be more prone to deviant behaviors when exposed to stressful events (Mottram & Fleming, 2009; Ray & Park, 2024). By contrast, individuals with high control (adherence) system scores are less likely to engage in cyberbullying, being more adept at problem-solving and more considerate of future consequences, among other things. However, prior studies have not examined these relationships in the context of parental psychological control and cyberbullying.

We aimed to examine the role of moral disengagement, dual system of self-control in the relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying in a college student sample. We hypothesized the following:

H1: Parental psychological control is associated with higher cyberbullying behaviors among vocational college students.

H2: Moral disengagement mediates the relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying for higher cyberbullying risk.

H3: The dual systems of self-control (impulse and control systems) moderate the relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying, such that higher impulsive system scores increase the likelihood of cyberbullying, while higher control system scores mitigate this effect.

Participants were 802 college students, of whom 53.99% were male and 46.01% were female. The average age of the participants was 18.11 ± 1.23. All participants voluntarily participated in the survey and signed informed consent. The study was approved by the authors’ university.

Parental psychological control

Parental Psychological Control Scale (PPCS, Wang et al., 2007) consists of 18 items (e.g., “When I failed to meet my parents’ expectations, they made me feel guilty”). Each item is rated on a 5-point Likert scale, with 1 indicating “never” and 5 indicating “always”. A higher total score suggests a higher level of parental psychological control. In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for PPCS scores was 0.92.

The Moral Disengagement Scale (MDS, Bandura et al., 1996) includes 26 items (e.g., “It is okay to steal for the needs of your family”). The items are on a 5-point scale (1 = “very inconsistent”, 5 = “very consistent”). Higher scores indicate a more significant level of moral disengagement. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for MDS scores was 0.90.

The Dual-Mode of Self-Control Scale (DMSCS, Xie et al., 2014) consists of 21 items on a 5-point scale (1 = “very noncompliant”, 5 = “very compliant”). The impulsive system consists of 12 items (e.g., “I often do or say things without thinking”), with higher scores indicating greater impulsivity. The control system consists of 9 items (e.g., “I often consider the pros and cons of things before making decisions”), with higher scores indicating greater control. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the DMSCS impulsive and control systems scores in the study were 0.88 and 0.87, respectively.

The Cyberbullying Scale CS (Li, 2020) consists of 6 items (e.g., “I use the Internet to terrorize and threaten others”). The scale uses a 4-point scale (1 = “never”, 4 = “over 5 times”). Higher scores indicate more severe cyberbullying. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for CS scores was 0.91.

The data were analyzed using SPSS 25.0 for descriptive statistics and Pearson’s correlation analysis. The Process macro program of SPSS was employed to test the mediating effect of moral disengagement between parental psychological control and cyberbullying using PROCESS Model 4. PROCESS Model 5 was applied to test the moderating roles of the impulse system and control system in the model, respectively. All variable scores were standardized.

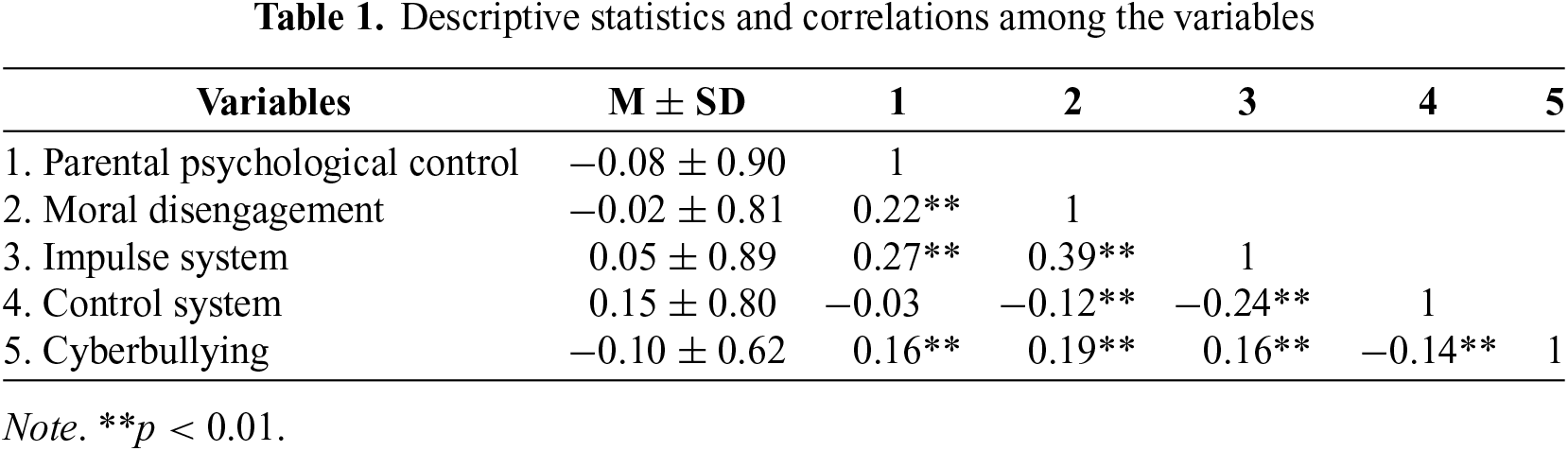

Table 1 indicated the significant correlations between parental psychological control, moral disengagement, impulse system, control system and cyberbullying (p < 0.01).

Parental control and cyberbullying

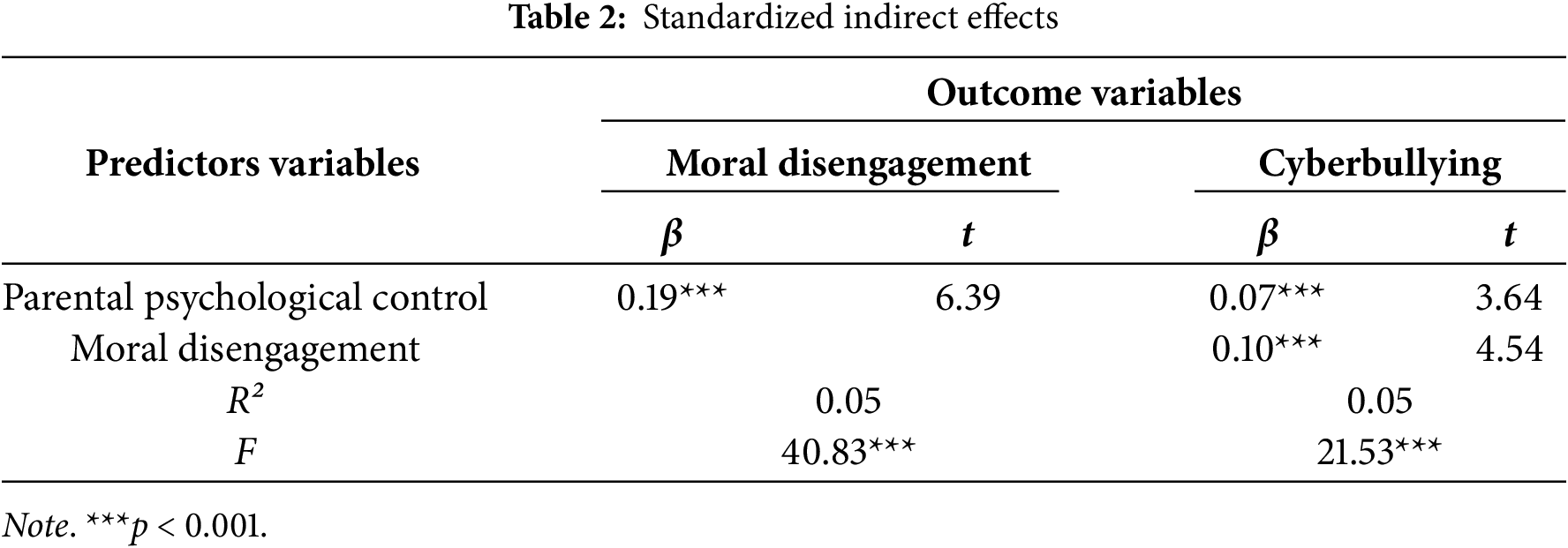

As in Table 2, the results indicate that parental psychological control significantly and positively predicts both moral disengagement and cyberbullying, supporting the H1. Specifically, parental psychological control was found to have a significant positive effect on moral disengagement (β = 0.19, p < 0.001). Additionally, parental psychological control was found to have a significant positive effect on cyberbullying (β = 0.07, p < 0.001). The results show that parental psychological control significantly and positively predicts both moral disengagement and cyberbullying. Additionally, moral disengagement has a significant positive effect on cyberbullying.

In this study, Model 4 was used to test the mediating role of moral disengagement between parental psychological control and cyberbullying. As in Table 2, when moral disengagement was introduced as a mediating variable, moral disengagement maintained a significant positive predictive effect on cyberbullying (β = 0.10, p < 0.001). Bootstrap 95% confidence interval analyses indicated that the total effect of parental psychological control on cyberbullying (0.09) and a mediating effect of moral disengagement (0.02), the proportions of mediation effects to total effects were 22%. This suggests that moral disengagement plays a partial mediating role between parental psychological control and cyberbullying, supporting the H2.

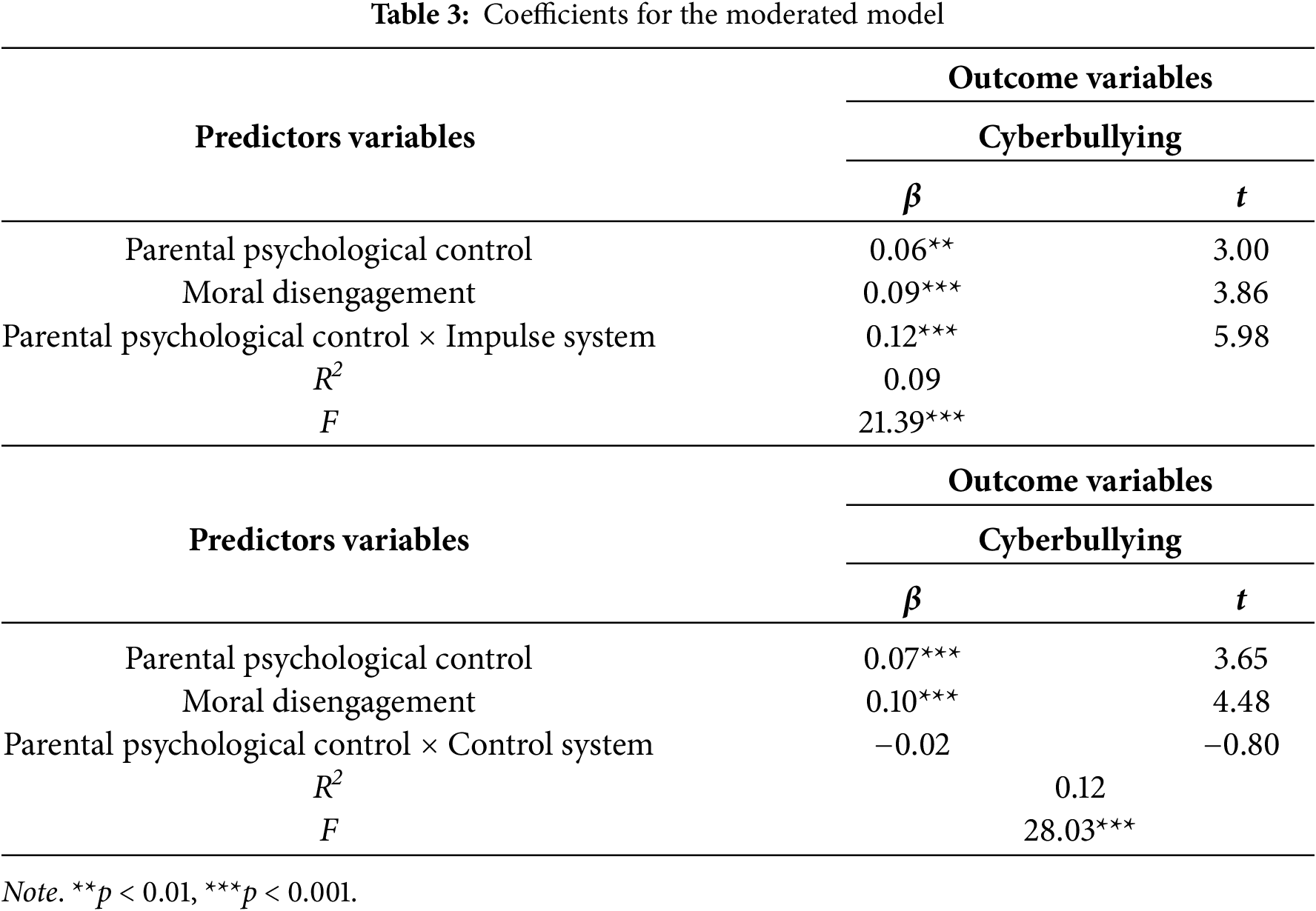

Table 3 shows the impulse and control systems of self-control moderate the relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying. The interaction between parental psychological control and the impulsive system significantly and positively predicts vocational college students’ cyberbullying (β = 0.12, p < 0.001), indicating that the impulsive system enhances the effect of parental psychological control on cyberbullying. While the interaction between parental psychological control and control system didn’t predict cyberbullying (β = −0.02, p > 0.05), partially supporting the H3.

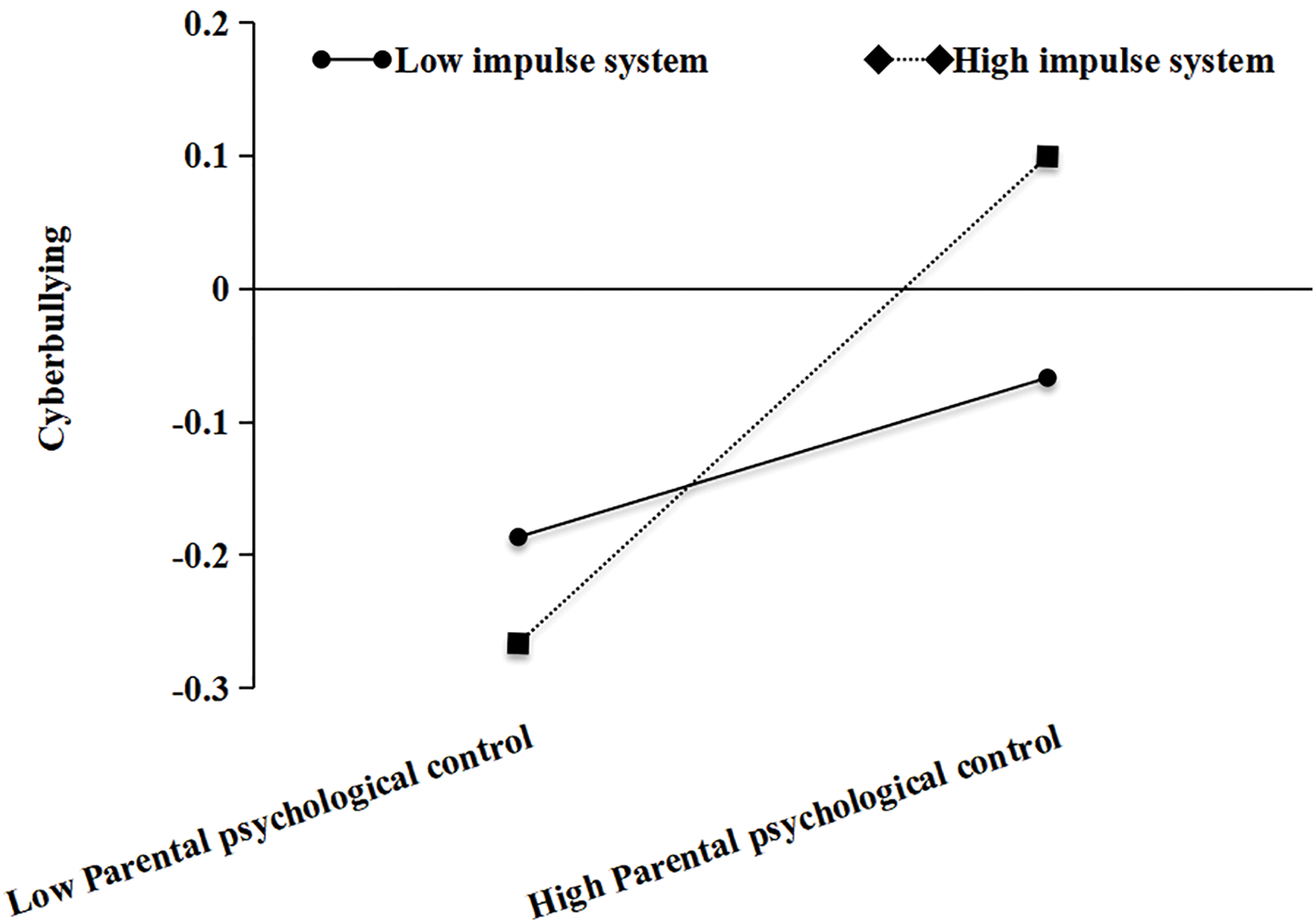

In order to understand how self-control moderates the effects of parental psychological control on college students’ cyberbullying, a simple slope analysis was conducted (Fig. 1). Using the M ± 1SD as the critical value, individuals with high scores on the impulsive system showed a significant positive prediction of parental psychological control on cyberbullying (βsimple = 0.17, p < 0.01), while this predictive effect was not significant for individuals with low impulsive system scores (βsimple = −0.05, p = 0.07). This suggests that parental psychological control is more likely to motivate students with high impulsive system to engage in cyberbullying.

Figure 1: The interaction of parental psychological control and impulse system

The results of this study show that parental psychological control has a significant effect on vocational college students’ cyberbullying. This may be explained by the fact that parents may be role models, and also a guide for behavioral patterns and interpersonal interactions (Geng et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2022b). Nonetheless, excessive parental psychological control can disrupt an individual’s “internal working mechanism,” making them more prone to suspicious and sensitive phenomena and social adjustment problems (Barberis et al., 2023; Gong & Wang, 2023). This exacerbates the tendency of aggressive behavior and contributes to the emergence of cyberbullying.

Moral disengagement played a partially mediating role in the association between parental psychological control and cyberbullying experiences. Family factors can change an individual’s internal moral cognition and form a negative cognitive mechanism of moral disengagement (Bartolo et al., 2019; Qi, 2019). Parental psychological control is capital for their cognitive and emotional development, preventing moral disengagement (Kim & Kim, 2013). Risks for moral disengagement increase the likelihood of cyberbullying by reducing the individual’s guilt for misbehavior and providing a basis for rationalizing the behavior (Thornberg et al., 2024). Additionally, the reduced social cues and the anonymity of the network itself help to enhance an individual’s moral disengagement.

The impulse system was associated with parental psychological control and risk for cyberbullying. Individuals with high impulse system are more likely to engage in cyberbullying after being parental psychological control (Shi et al., 2020). Also, excessive parental psychological control could be harmful by impeding individual autonomy, self-trust, and freedom of expression (Geng et al., 2021). Consequently, individuals with high levels of impulse system are more prone to externalizing negative emotions through behaviors like cyberbullying (Chyung et al., 2022). Those with weak parental control would be more vulnerable to cyberbullying (see also Hofmann et al., 2009). Additionally, parental psychological control and the control system didn’t predict cyberbullying. One possible explanation is that the control system focuses more on inhibiting the impulsive system than the previous self-control model (Hofmann et al., 2009). When an individual’s impulsive system is strong, the level of the control system is weak, leading to increased predictive effects of parental psychological control on cyberbullying that cannot be mitigated by the control system. These findings emphasize the importance of enhancing self-control to prevent cyberbullying. The study not only sheds light on the complex relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying but also offers new approaches for developing targeted interventions.

Implications for research and practice

The findings have important implications. In theoretical terms, the study combines the general attack model and the dual system theory of self-control to contribute to the exploration and development of the general attack theory. It provides a new theoretical perspective for the study of aggressive behavior in the future.

In practical terms, it offers guidance for intervention for preventing cyberbullying behavior among college students. It emphasizes the need to reduce harmful parental control to reduce students’ impulse system levels, minimizing cyberbullying risk.

Limitations and future directions

The are some limitations. Firstly, this study was cross-sectional, so it could not establish a causal relationship between parental psychological control and cyberbullying. Future studies should use longitudinal studies to determine if any causal relationships. Secondly, this study only involved Chinese vocational college students, the findings are limited. Future studies should include participants from other regions or different groups to validate the results. Finally, all the measurements in this study relied on questionnaires, which are highly subjective. In the future, researchers can consider using both subjective and objective data collection methods for more informative data.

We conclude from this study that excessive parental psychological control predicts cyberbullying risk. Moral disengagement mediates between parental psychological control and cyberbullying for lower cyberbullying risk. Impulsivity moderates the effects of parental psychological control on vocational college students’ cyberbullying, increasing cyberbullying risk. Finally, control systems don’t moderate the effects of parental psychological control on vocational college students’ cyberbullying.

Acknowledgement: We thank all participants for their involvement and the anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Industry-Education Integration and Collaborative Education Project (No. 230806121220054) and the Joint Founding Project of Innovation Research Institute of Xijing Hospital (LHJJ24XL06).

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Huaibin Jiang; data collection: Huihang Qin, Lei Ren; analysis and interpretation of results: Feifei Xu, Lin Shao; draft manuscript preparation: Huaibin Jiang; critical revision of the manuscript: Yaning Guo, Xinyi Wei, Qingyi Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were per the ethical standards of the Fujian Polytechnic Normal University (2022-013) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Bandura, A. (1999). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumanities. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 3(3), 193–209. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0303_3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Moral Education, 31(2), 101–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724022014322 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71(2), 364–374. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.2.364 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barberis N., Cannavò M., Cuzzocrea F., & Verrastro V. (2023). Alexithymia in a self determination theory framework: The interplay of psychological basic needs, parental autonomy support and psychological control. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(9), 2652–2664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02303-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bartolo, M. G., Palermiti, A. L., Servidio, R., Musso, P., & Costabile, A. (2019). Mediating processes in the relations of parental monitoring and school climate with cyberbullying: The role of moral disengagement. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(3), 568–594. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v15i3.1742. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Tice, D. M. (2007). The strength model of self-control. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00534.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bornstein, M. H., Yu, J., & Putnick, D. L. (2022). Prospective associations between mothers’ and fathers’ parenting styles and adolescents’ moral values: Stability and specificity by parent style and adolescent gender. New Directions For Child and Adolescent Development, 2022(185–186), 9–25. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20488. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chyung, Y. J., Lee, Y. A., Ahn, S. J., & Bang, H. S. (2022). Associations of perceived parental psychological control with depression, anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Marriage & Family Review, 58(2), 158–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2021.1941496 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dewall, C. N., Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2011). The general aggression model: Theoretical extensions to violence. Psychology of Violence, 1(3), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023842 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Friese, M., & Hofmann, W. (2009). Control me or I will control you: Impulses, trait self-control, and the guidance of behavior. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(5), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.07.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Geng, J., Wang, X., Wang, Y., Lei, L., & Wang, P. (2022). “If You Love Me, You Must Do..” parental psychological control and cyberbullying perpetration among Chinese adolescents. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(9–10), NP7932–NP7957. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520978185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Geng, J., Wang, P., Zeng, P., Liu, K., & Lei, L. (2021). Relationship between honesty-humility and cyberbullying perpetration: A moderated mediation model. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(15–16), 14807–14829. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211016346. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Gong, X., & Wang, C. (2023). Interactive effects of parental psychological control and autonomy support on emerging adults’ emotion regulation and self-esteem. Current Psychology, 42(19), 16111–16120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01483-3 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hofmann, W., Friese, M., & Strack, F. F. (2009). Impulse and self-control from a dual-systems perspective. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4(2), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01116.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kim, J. M., & Kim, J. M. (2013). The effect of parental psychological control and moral disengagement on children’s participant role behavior in a bullying situations. Korean Journal of Child Studies, 34(6), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.5723/KJCS.2013.34.6.13 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, Y. J. (2020). Effect of parent-adolescent conflict on cyberbullying: The chain mediating effect and its gender difference. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(3), 605–610. https://doi.org/10.16128/j.cnki [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Li, H., Guo, Q., & Hu, P. (2023). Moral disengagement, self-control and callous-unemotional traits as predictors of cyberbullying: A moderated mediation model. BMC Psychology, 11(1), 247. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01287-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Liang, H., Zhu, F., Li, X., Jiang, H., Zhang, Q. et al. (2024). The link between bullying victimization, maladjustment, self-control, and bullying: A comparison of traditional and cyberbullying perpetrator. Youth & Society, 57(3), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X241247213 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Méndez, I., Jorquera, H. A. B., & Ruiz-Esteban, C. (2020). Profiles of mobile phone problem use in bullying and cyberbullying among adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 596961. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.596961. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Mottram, A. J., & Fleming, M. J. (2009). Extraversion, impulsivity, and online group membership as predictors of problematic internet use. Journal of Cybertherapy and Rehabilitation, 12(3), 319–321. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Qi, W. (2019). Harsh parenting and child aggression: Child moral disengagement as the mediator and negative parental attribution as the moderator. Child Abuse & Neglect, 91(4), 9112–9122. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.02.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ray, J. V., & Park, H. (2024). The influence of parenting on delinquency: The mediating role of peers and the moderating role of self-control. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 51(6), 876–895. https://doi.org/10.1177/00938548241229678 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Scharf, M., & Goldner, L. (2018). “If you really love me, you will do/be..”: Parental psychological control and its implications for children’ s adjustment. Developmental Review, 49, 16–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.07.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shi, H., Fan, C., Chu, X., Zhang, X., & Wu, L. (2020). Cyberbullying victimization and cyberbullying perpetration among adolescents: The roles of normative beliefs about aggression and dual-mode of self-control. Journal of Psychological Science, 43(5), 1117–1124. https://doi.org/10.16719/j.cnki.1671-6981.20200513 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Thornberg, R., Wänström, L., Sjögren, B., Pozzoli, T., & Gini, G. (2024). Concurrent associations between callous-unemotional traits, moral disengagement, and bullying perpetration in adolescence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 40(5–6), 1459–1483. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605241260007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, D., Nie, X., Zhang, D., & Hu, Y. (2022a). The relationship between parental psychological control and problematic smartphone use in early Chinese adolescence: A repeated-measures study at two time-points. Addictive Behaviors, 125(1), 107142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, Q., Pomerantz, E. M., & Chen, H. (2007). The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development, 78(5), 1592–1610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01085.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, W., Chen, S., Wang, S., Shan, G., & Li, Y. (2023). Parental burnout and adolescents’ development: family environment, academic performance, and social adaptation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 2774. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20042774. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wang, X., Wang, W., Qiao, Y., Gao, L., Yang, J. et al. (2022b). Parental phubbing and adolescents’ cyberbullying perpetration: A moderated mediation model of moral disengagement and online disinhibition. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(7–8), NP5344–NP5366. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520961877. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Xie, D., Wang, L., Tao, T., Fan, Ch., & Gao, W. (2014). Validity and reliability of the Chinese version of the dual-mode of self-control scale for adolescents. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 28(5), 386–391. https://doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1000 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zhang, Y., Chen, C., Teng, Z., & Guo, C. (2021). Parenting style and cyber-aggression in chinese youth: The role of moral disengagement and moral identity. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 621878. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.621878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Zhao, L., & Yu, J. (2021). A meta-analytic review of moral disengagement and cyberbullying. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 681299. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.681299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools