Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Workplace spirituality and mindfulness in professional female dancers: The mediating role of mental well-being in organizational Commitment

1 Department of Dance, Sejong University, Seoul, 05006, Republic of Korea

2 Institute of Cultural Arts Education, Sangmyung University, Cheonan-si, 31006, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Dance, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, 03063, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Author: Ja-young Sul. Email:

# These authors are the co-first author

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(4), 451-461. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068037

Received 13 February 2025; Accepted 12 May 2025; Issue published 17 August 2025

Abstract

This study examined the relationships among workplace spirituality, mindfulness, mental well-being, and organizational commitment in professional female dancers. A total of 424 dancers from the United States participated in the survey. Structural equation modeling indicated that workplace spirituality was positively associated with both mental well-being and organizational commitment, whereas mindfulness was significantly related only to organizational commitment. Mental well-being was a significant predictor of organizational commitment and mediated the relationship between workplace spirituality and organizational commitment, but not between mindfulness and commitment. These results suggest that workplace spirituality functions as a psychological resource that enhances emotional health and strengthens organizational engagement. These findings are consistent with self-determination theory, highlighting the role of value congruence and intrinsic purpose in sustaining motivation in high-performance contexts. Moreover, the study findings underscore the importance of fostering spiritually supportive work environments to promote psychological well-being and long-term organizational commitment.Keywords

Dance has been widely recognized as a powerful medium for expressing identity, emotion, and transcendence. Across diverse cultural contexts, it is often conceptualized as a vehicle for transcending ordinary experience, evoking states of timelessness and spiritual elevation (Gronek et al., 2023; Kraus, 2014). Professional dancers frequently report intense psychological and somatic experiences during performance, indicating that dance functions not only as a physical discipline but also as a form of embodied spirituality. Within the global dance industry, female dancers comprise a growing and prominent segment (Farrer, 2014; Jung, 2023). Despite their increasing representation, limited empirical research has examined the organizational and psychological aspects of their professional experiences, particularly in relation to mental well-being and workplace integration (Aboobaker et al., 2021; Riasudeen & Singh, 2021). This research gap is notable given that female dancers are subject to specific occupational stressors that may adversely affect mental health, organizational commitment, and mindful engagement. In such contexts, workplace environments that support spirituality and psychological resilience may be critical for fostering sustainable professional engagement.

Workplace spirituality and mindfulness

Workplace spirituality is typically defined as an individual’s experience of meaning, purpose, and connectedness in the professional setting, often manifested through the alignment between personal values and organizational objectives (Pawar, 2016; Milliman et al., 2003). Individuals with higher levels of workplace spirituality tend to exhibit stronger identification with organizational missions, increased resilience in challenging circumstances, and greater engagement in collaborative goals (Jung, 2023). In professions such as dance, where personal expression intersects with organizational cohesion, workplace spirituality may serve as a critical resource for enhancing psychological well-being and sustaining professional involvement (Garg, 2017; Riasudeen & Singh, 2021).

Within this framework, mental well-being refers to a positive psychological condition encompassing emotional stability, self-esteem, and life satisfaction (Guite et al., 2006). Organizational environments that affirm intrinsic values and a sense of meaning may support dancers in managing stress and maintaining emotional balance. Thus, workplace spirituality operates not only as a philosophical construct but also as a psychosocial resource that contributes to both individual thriving and organizational commitment.

Although conceptually distinct, mindfulness has been regarded as a complementary construct to workplace spirituality, promoting intentional awareness and nonjudgmental acceptance of present experiences (Kabat-Zinn, 2015). Defined as sustained attention to present-moment internal and external experiences (Shapiro et al., 2006), mindfulness enhances attentional control, emotional regulation, and interpersonal responsiveness. In occupational contexts, mindfulness has been associated with improved job performance, lower burnout levels, and stronger organizational commitment (Dane & Brummel, 2014; Lee & Lim, 2017; Voci et al., 2016). Among professional dancers, mindfulness may play a pivotal role in regulating stress and maintaining long-term engagement in physically and emotionally demanding environments.

The mediating effect of mental well-being

Mental well-being refers to an individual’s sustained psychological equilibrium, characterized by positive affect, life satisfaction, and emotional fulfillment. It is particularly salient among individuals who perceive their lives as meaningful and maintain a positive future orientation (Fisher, 2010; Ramlall, 2008; Jalilianhasanpour et al., 2021). Empirical research has consistently demonstrated that mental well-being is associated with higher levels of optimism, improved job performance, and long-term professional engagement (Kluemper et al., 2009; Luthans et al., 2008; Magnier-Watanabe et al., 2017). Employees reporting high psychological well-being also tend to exhibit greater stress resilience and stronger organizational commitment (Emre & De Spiegeleare, 2021; Jain et al., 2019).

Organizational commitment is defined as a psychological attachment to one’s organization, encompassing identification with institutional goals, emotional investment, and sustained loyalty (Guzeller & Celiker, 2020; Lambert et al., 2021). High levels of commitment have been linked to reduced turnover, increased morale, and enhanced organizational productivity. Employees with strong commitment are more likely to integrate their professional roles into their self-concept, facilitating consistency in managing both individual and organizational responsibilities (Chiu et al., 2020; Sungu et al., 2019).

Among professional dancers, mental well-being may function as a key psychological resource that reinforces commitment to artistic organizations. The affective stability derived from well-being may mediate the influence of workplace factors—such as spirituality and mindfulness—on organizational alignment and sustained engagement.

Self-Determination Theory (SDT) posits that human motivation is driven by three fundamental psychological needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness. These needs guide individuals toward behaviors aligned with intrinsic values and internalized goals (Deci & Ryan, 2012; Milliman et al., 2003). Intrinsic values are often informed by deeply held beliefs, including spiritual and moral dimensions, which influence an individual’s sense of purpose and fulfillment in the workplace (Conway et al., 2015; Rego & Pina e Cunha, 2008; Krajcsák, 2020).

Individuals motivated by self-determined processes tend to exhibit psychological stability, characterized by intentionality, emotional regulation, and goal-directed behavior (Carlson et al., 2013; Meins et al., 2002). These attributes contribute not only to enhanced organizational engagement (Preckel et al., 2018), but also to the maintenance of mental well-being over time (Diener et al., 2003; Deci & Porac, 2015).

Furthermore, self-determined functioning has been associated with increased mindful awareness in both social and professional contexts. It fosters emotional resilience, openness to experience, and collaborative behavior (Halladay et al., 2019; Zollars et al., 2019). In high-performance domains such as professional dance, SDT offers a robust theoretical lens through which to understand how psychological resources—specifically workplace spirituality and mindfulness—contribute to mental well-being and organizational commitment.

The female dancers’ work setting

Professional female dancers work in a highly demanding occupational context characterized by rigorous physical performance standards, intensified aesthetic scrutiny, and unstable employment structures. Their careers typically begin in early adolescence, requiring early specialization and sustained physical discipline, and are often shaped by perfectionistic norms and appearance-based pressures (Gronek et al., 2023; Kraus, 2014). These structural and cultural demands have been associated with increased risk of psychological concerns, including anxiety, depression, disordered eating, and body dissatisfaction (Nordin-Bates et al., 2014; Nordin-Bates, 2020; Pouwer et al., 2020). Additionally, the emotionally expressive nature of dance may blur personal and professional identity boundaries, posing challenges to emotional regulation and psychological stability.

Within this psychologically demanding environment, mindfulness has been identified as a protective factor that enhances emotional balance and cognitive focus. Evidence suggests that dancers who develop mindfulness are better able to manage performance-related stress, maintain concentration, and recover from setbacks (Barbour et al., 2020; Van Rens & Heritage, 2021). However, despite the internal discipline required in dance, many dancers work within precarious organizational structures—including freelance contracts, seasonal roles, and rigid hierarchies—that offer limited institutional support and weak prospects for long-term affiliation (Van Assche, 2017; Wood, 2021). These conditions may constrain the development of organizational commitment, particularly when dancers experience tension between personal passion and institutional loyalty. In such settings, workplace spirituality—by fostering meaning, value alignment, and interpersonal connection—may serve as a psychological resource that promotes resilience and sustained organizational engagement (Jung, 2023).

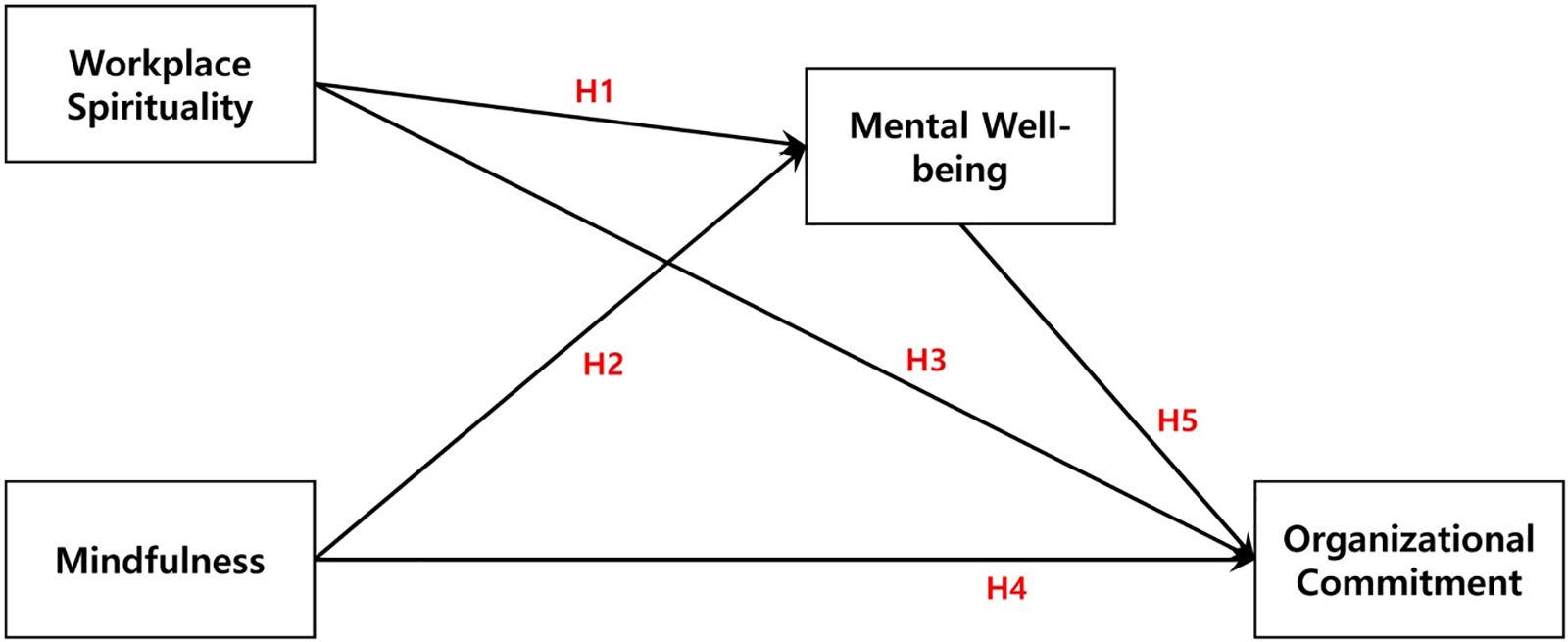

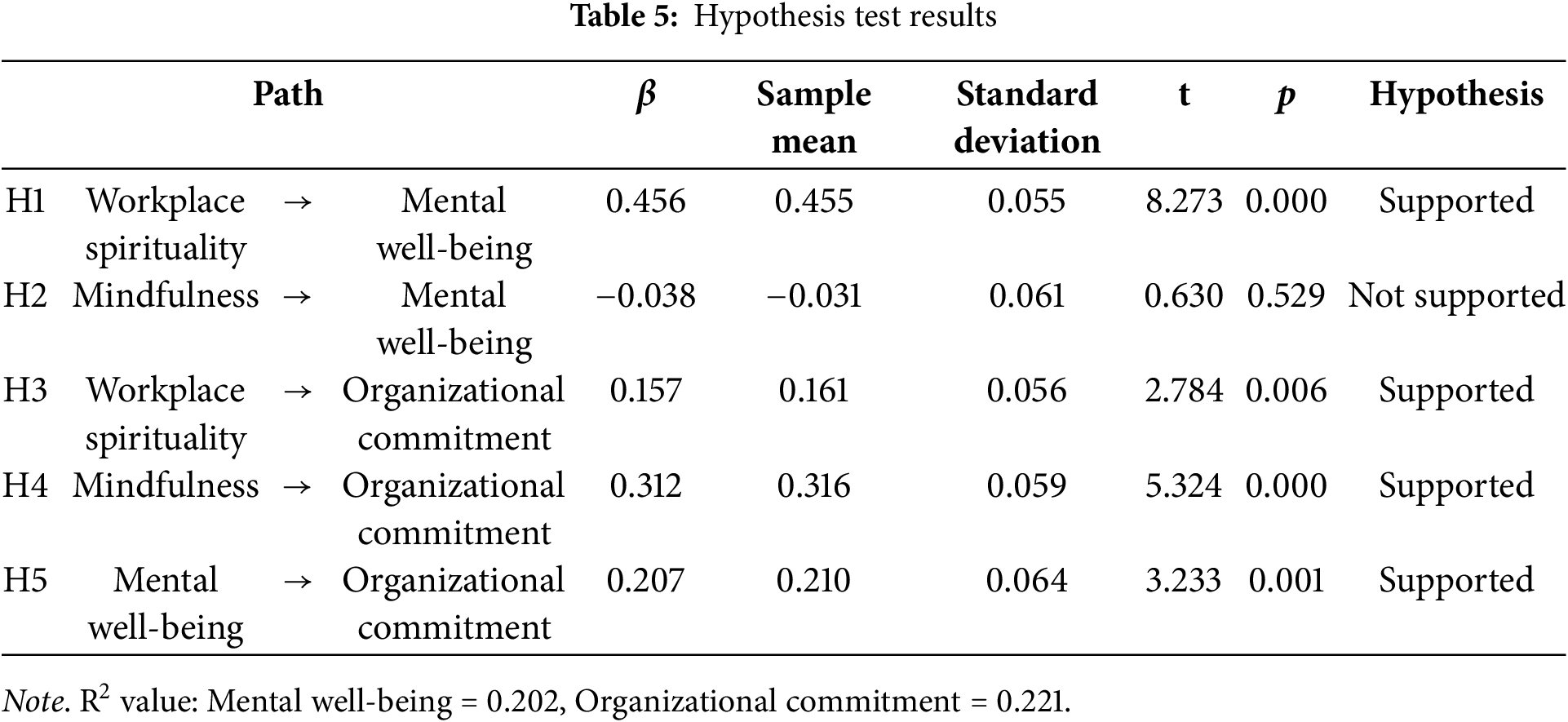

This study examines the relationships among workplace spirituality, mindfulness, mental well-being, and organizational commitment among professional female dancers. Grounded in Self-Determination Theory and prior empirical research, it is hypothesized that workplace spirituality and mindfulness contribute to mental well-being, which in turn enhances organizational commitment. Mental well-being is further proposed to serve as a mediating variable in these associations. Based on this framework, the following hypotheses were formulated:

▪ H1: Workplace spirituality is positively associated with mental well-being.

▪ H2: Mindfulness is positively associated with mental well-being.

▪ H3: Workplace spirituality is positively associated with organizational commitment.

▪ H4: Mindfulness is positively associated with organizational commitment.

▪ H5: Mental well-being is positively associated with organizational commitment.

These hypotheses are illustrated in the conceptual model presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research model

The study sample comprised 424 professional female dancers aged 20 to 40 years, all residing in the United States. Participants were recruited through Entrust Survey, a global research agency with a pre-registered respondent panel. Eligibility was restricted to individuals with verified professional dance experience. The authors developed the questionnaire, which was administered via Entrust Survey’s panel system.

The United States was selected as the study context due to its internationally recognized prominence in the performing arts. Renowned institutions such as The Juilliard School, the San Francisco Ballet School, and the School of American Ballet serve as leading training centers for elite dancers, while companies such as the American Ballet Theatre represent structured organizational environments in which dancers develop sustained artistic and institutional identities.

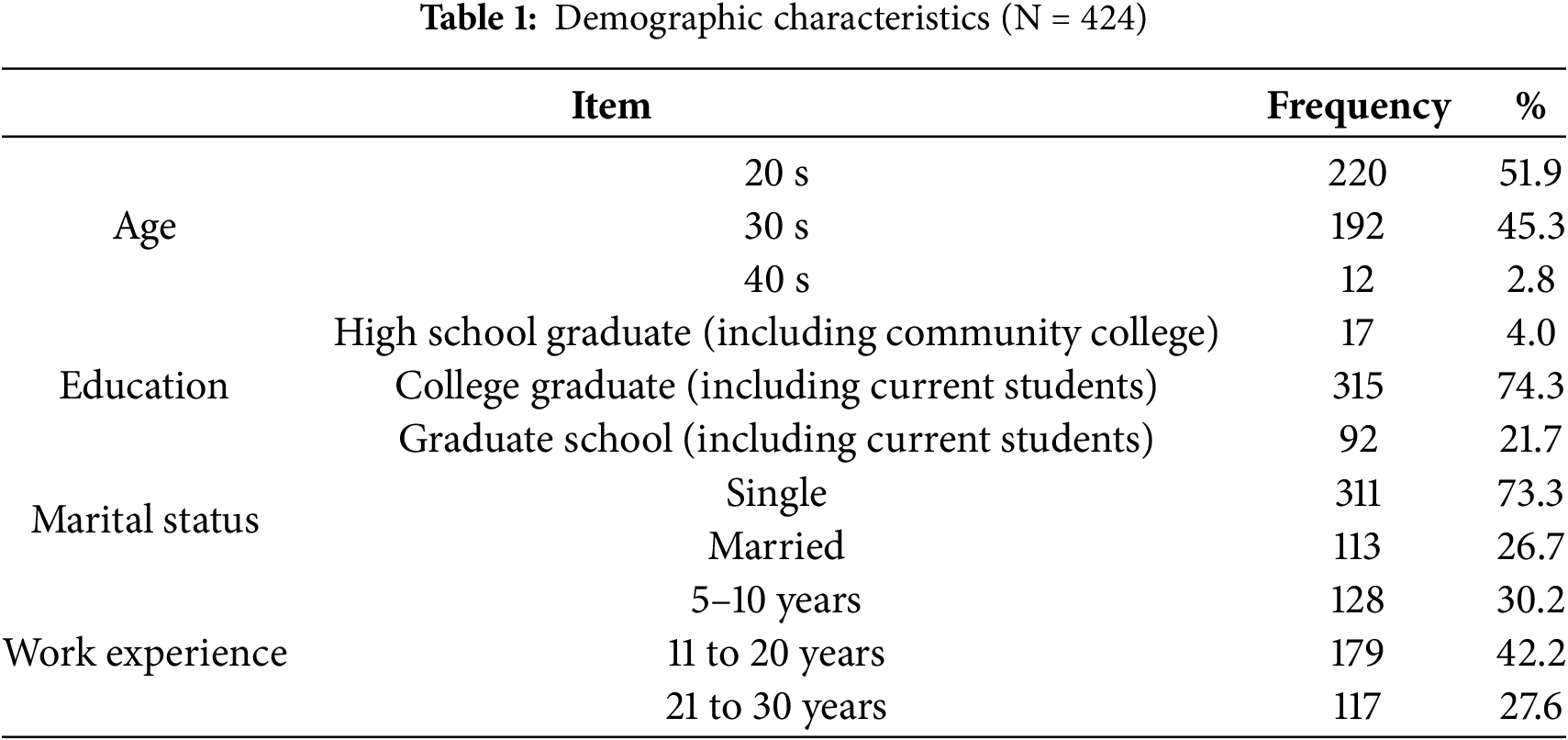

Most participants had completed at least a college degree, and the majority identified as single. A considerable proportion reported between 11 and 20 years of professional experience, indicating a high level of engagement with organizational structures and performance demands. These demographic characteristics suggest that the sample was appropriate for investigating workplace spirituality, mindfulness, and organizational commitment. A summary of participant demographics is presented in Table 1.

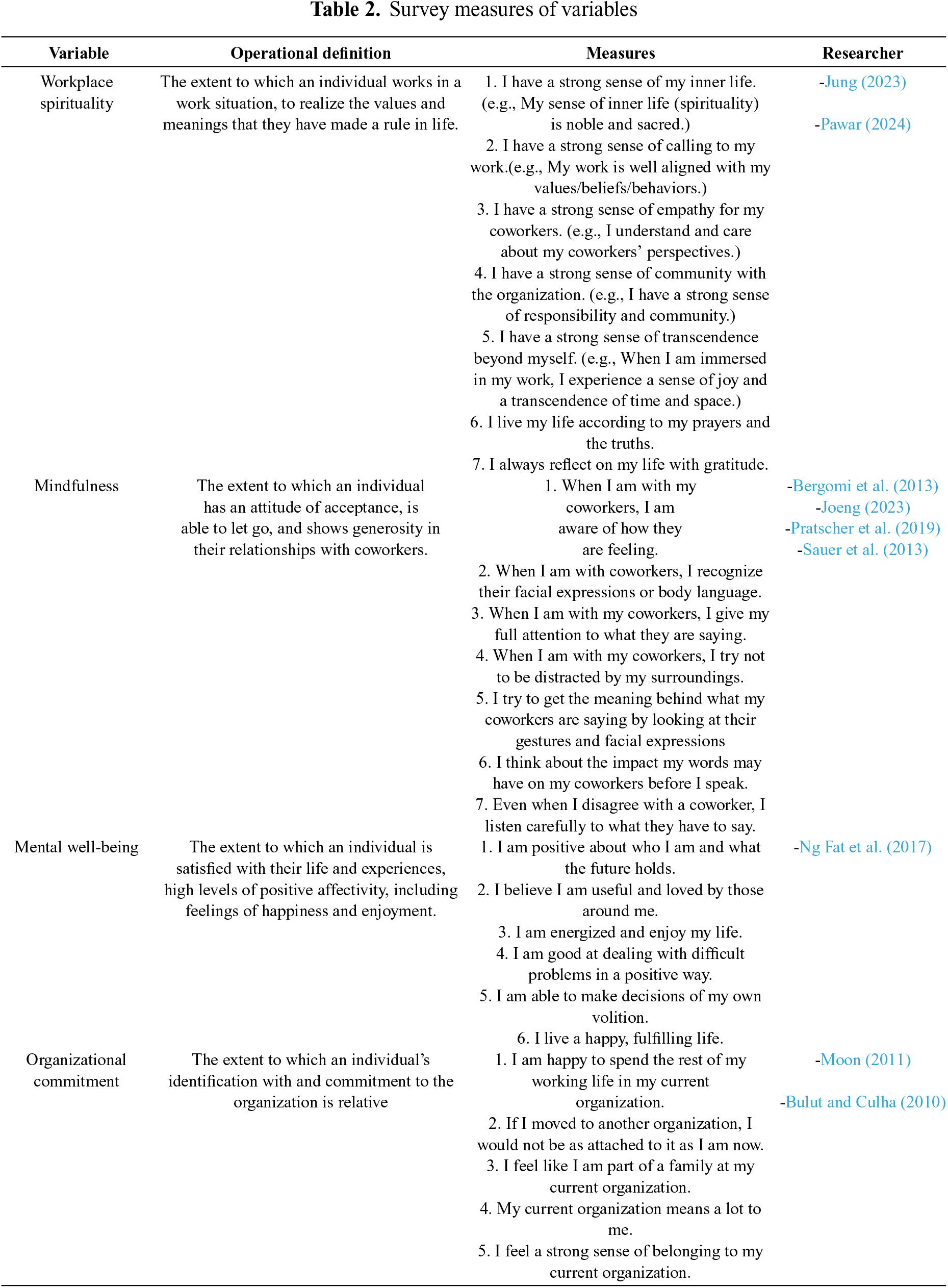

Participants completed a self-administered questionnaire consisting of four standardized scales measuring workplace spirituality, mindfulness, mental well-being, and organizational commitment. All items were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). Table 2 outlines the operational definitions, core dimensions, and example items for each construct.

The Workplace Spirituality scale comprised five dimensions: inner life, sense of calling, empathy, community, and transcendence (e.g., “My work is well aligned with my values, beliefs, and behaviors”). The Mindfulness scale assessed interpersonal awareness and attentional presence (e.g., “When I am with my coworkers, I give my full attention to what they are saying”). The Mental Well-Being scale measured psychological optimism, vitality, and life satisfaction (e.g., “I live a happy, fulfilling life”). The Organizational Commitment scale evaluated emotional attachment and perceived belongingness to the organization (e.g., “I feel like I am part of a family at my current organization”).

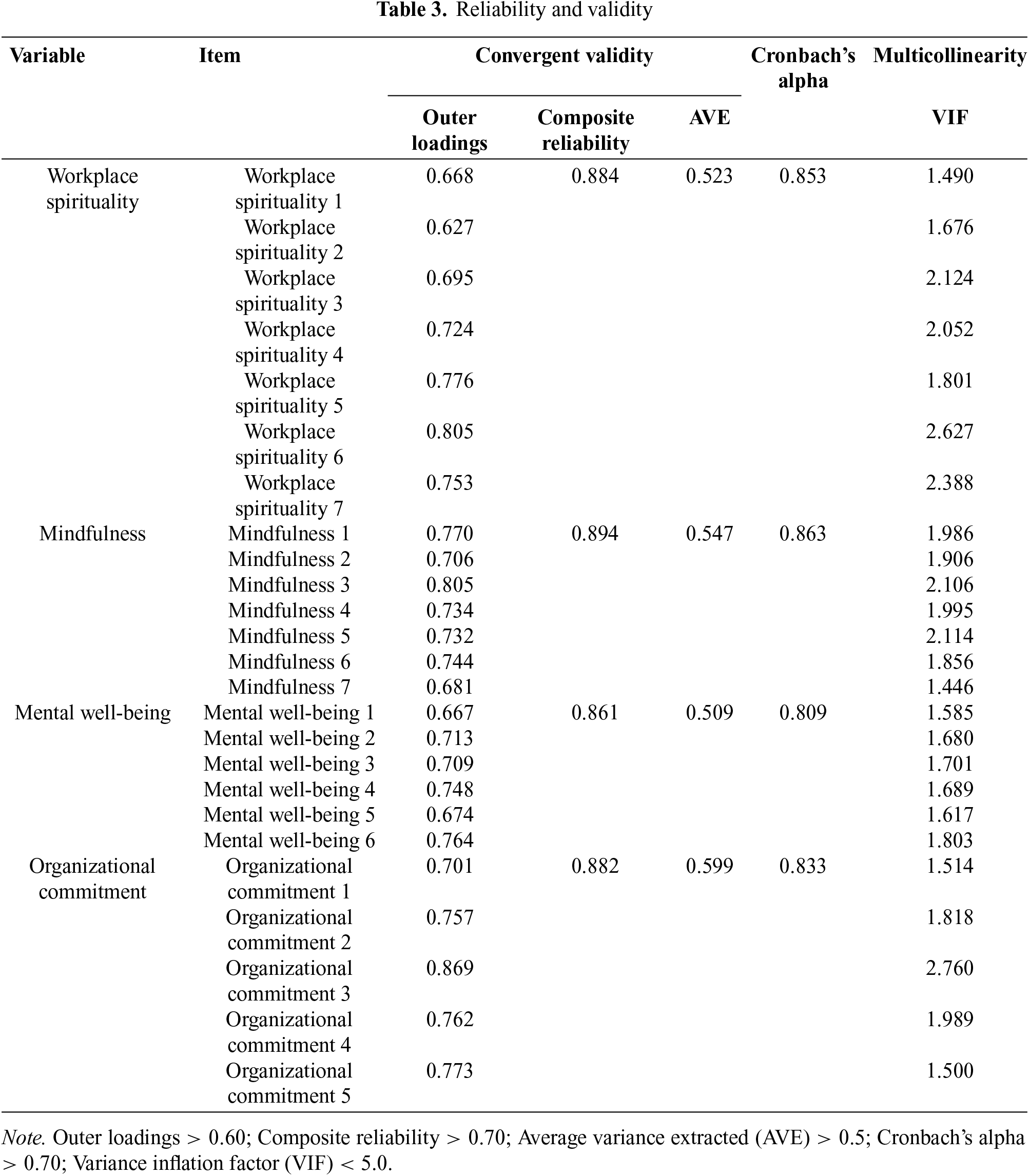

All measurement instruments demonstrated satisfactory psychometric properties. As reported in Table 3, outer loadings for individual items exceeded the threshold of 0.60, indicating acceptable item reliability. Composite reliability values for all constructs were above 0.70, confirming internal consistency. The average variance extracted (AVE) values for each construct exceeded the benchmark of 0.50, supporting convergent validity. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients were all above 0.80, further verifying scale reliability. No multicollinearity issues were observed, as all variance inflation factor (VIF) values were well below the cutoff value of 5.0.

The study utilized a self-administered online survey developed by the authors and distributed via Entrust Survey, a global research organization with a pre-registered panel of participants. Eligibility was determined based on predefined criteria, including verified professional experience in dance. Entrust Survey managed participant recruitment and data collection through its panel infrastructure.

All participants had previously provided informed consent to participate in academic research, in accordance with international data protection regulations. No personally identifiable or sensitive information was collected, and all data were fully anonymized prior to analysis.

The study was formally exempted from institutional review board (IRB) oversight under Articles 2 and 15 of the Bioethics and Safety Act of the Republic of Korea. A signed exemption certificate is retained by the authors. At the outset of the survey, participants were presented with an introductory page detailing the voluntary nature of participation, the confidentiality of responses, and data protection under Article 33 of the Statistics Act. Standard non-monetary compensation (e.g., points or coupons) was provided, and screening questions were included to verify eligibility.

Structural equation modeling (SEM) was conducted using SmartPLS to test the hypothesized relationships. This software was selected due to its capacity to accommodate complex, multi-path models. The analysis assessed both direct effects and the mediating role of mental well-being in the relationships between workplace spirituality and organizational commitment, and between mindfulness and organizational commitment.

Statistical significance of the path coefficients and model estimates was evaluated using a non-parametric bootstrapping procedure. Key evaluation metrics included path coefficients, Cronbach’s alpha, heterotrait-monotrait (HTMT) ratios, and R² values (Han & Kim, 2021; Jung et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2022; Lee & Kim, 2020).

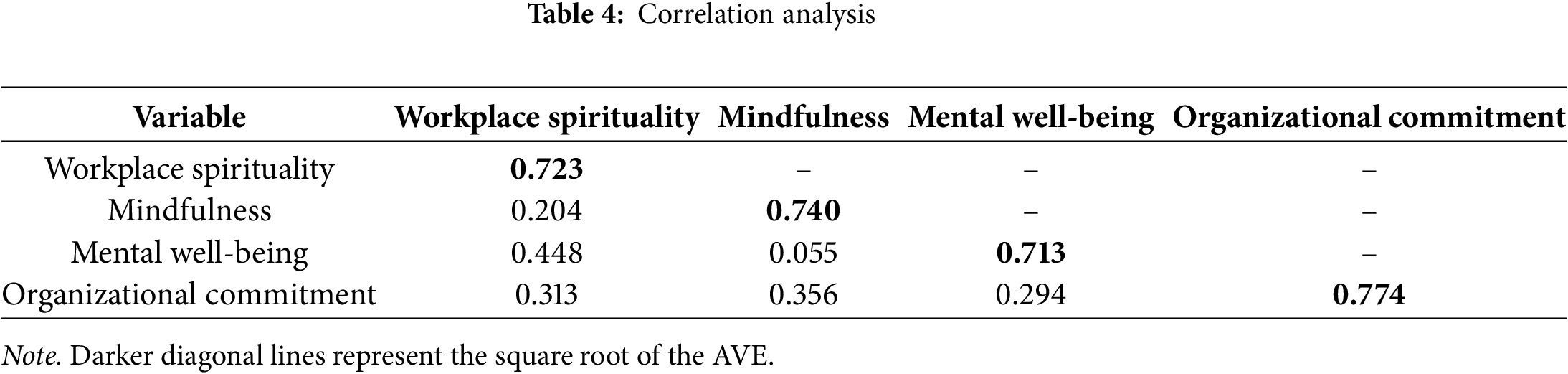

Discriminant validity was assessed using the Fornell–Larcker criterion, which compares the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each construct with its inter-construct correlations. As shown in Table 4, the square roots of the AVE values for all constructs exceeded their corresponding inter-construct correlations, indicating acceptable discriminant validity.

Discriminant validity and correlational analysis

As shown in Table 4, bivariate correlations among the main study variables ranged from small to moderate. Workplace spirituality was positively correlated with mindfulness, mental well-being, and organizational commitment. Mindfulness was also positively associated with organizational commitment, although its correlation with mental well-being was relatively weak. Mental well-being demonstrated a moderate positive correlation with organizational commitment, supporting its role as a potential mediating variable in the model.

Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) for each latent construct with its inter-construct correlations. In all cases, the square root of the AVE exceeded the corresponding correlations, indicating acceptable discriminant validity across the four constructs.

Workplace mental well-being and organizational commitment

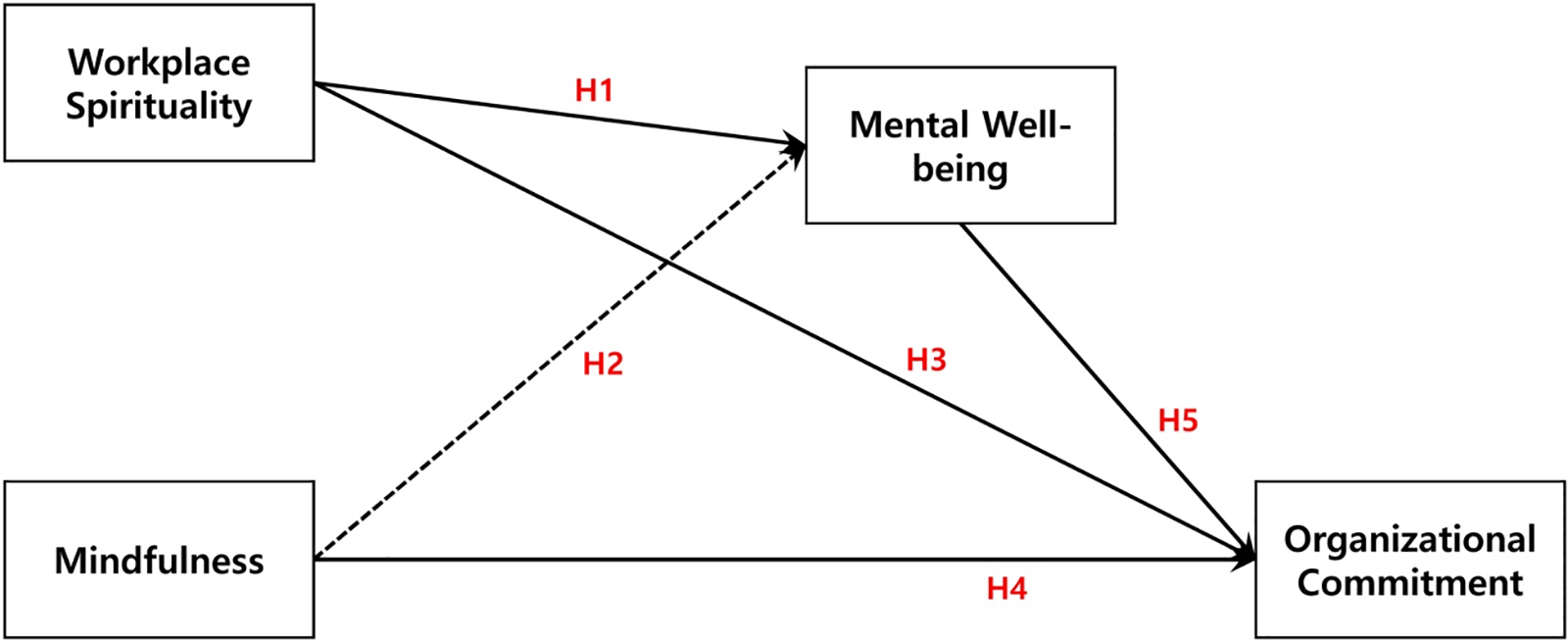

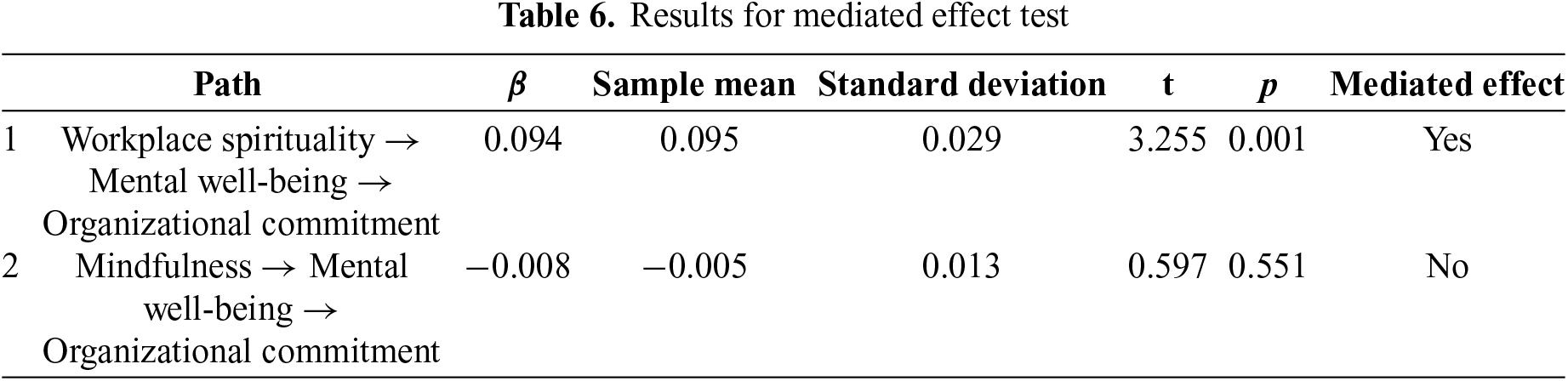

Table 5 presents the structural model results, and Figure 2 illustrates the hypothesized path relationships. Workplace spirituality had a significant positive effect on mental well-being (β = 0.456, t = 8.273, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 1. In contrast, mindfulness did not significantly predict mental well-being (β = –0.038, t = 0.630, p = 0.529), leading to the rejection of Hypothesis 2.

Figure 2: Hypothesis test results. Note: Black line: statistically significant; Black dotted line: not statistically significant.

Workplace spirituality was also positively associated with organizational commitment (β = 0.157, t = 2.784, p < 0.01), supporting Hypothesis 3. Mindfulness had a significant positive effect on organizational commitment (β = 0.312, t = 5.324, p < 0.01), confirming Hypothesis 4. Additionally, mental well-being significantly predicted organizational commitment (β = 0.207, t = 3.233, p < 0.01), providing support for Hypothesis 5.

Overall, these findings suggest that workplace spirituality is a significant predictor of both mental well-being and organizational commitment. Although mindfulness was not related to mental well-being, it demonstrated a direct and meaningful association with organizational outcomes.

Mediating effect of mental well-being

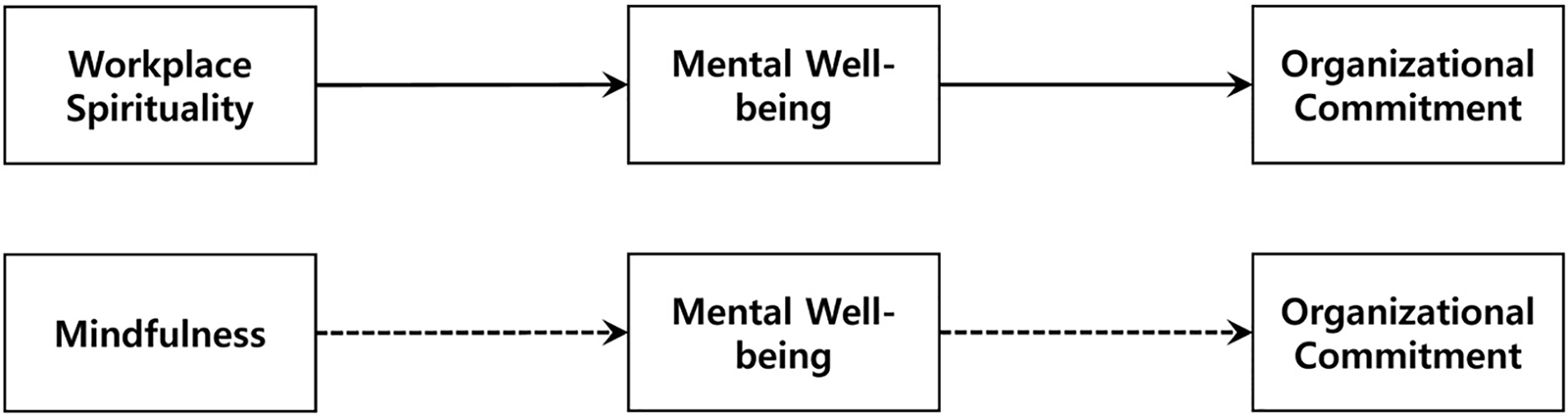

As shown in Table 6 and depicted in Figure 3, mental well-being significantly mediated the relationship between workplace spirituality and organizational commitment (β = 0.094, p < 0.01). This result confirms the presence of a statistically significant indirect effect, thereby supporting the mediating role of mental well-being in the pathway from workplace spirituality to organizational commitment (Hypothesis 4).

Figure 3: Mediated effect test results. Note: Black line (Mediated effect: Yes); Black dotted line (Mediated effect: No).

In contrast, the indirect effect of mindfulness on organizational commitment through mental well-being was not statistically significant (β = –0.008, p > 0.05). Accordingly, the hypothesized mediating role of mental well-being in the relationship between mindfulness and organizational commitment was not supported (Hypothesis 5).

The present study found that workplace spirituality significantly predicted mental well-being among professional female dancers. This finding is consistent with previous research suggesting that spiritually supportive work environments contribute to psychological balance and emotional resilience (Garg, 2017; Pawar, 2016; Riasudeen & Singh, 2021). Individuals who perceive their work as meaningful and purpose-driven are more likely to report higher psychological well-being. In the context of professional dance, which is both physically and emotionally demanding, workplace spirituality may function as a stabilizing psychological resource.

In contrast, mindfulness did not exhibit a significant effect on mental well-being, diverging from earlier studies highlighting its positive impact on psychological health (Cheung & Lau, 2021; Voci et al., 2019). A possible explanation is that in highly interpersonal environments like dance, heightened mindfulness—particularly in social interactions—may increase self-monitoring or emotional sensitivity. As noted by Kim and Han (1998), excessive focus on interpersonal harmony can lead to psychological strain, particularly when individuals suppress dissent to maintain group cohesion.

Workplace spirituality was also positively associated with organizational commitment, supporting findings that value alignment promotes ethical behavior, prosocial attitudes, and a strong connection between personal beliefs and organizational goals (Dal Corso et al., 2020; Jeon & Choi, 2021). In dance organizations, where trust, coordination, and non-verbal communication are central, workplace spirituality may facilitate a shared sense of identity and long-term commitment.

Although mindfulness was not related to mental well-being, it significantly predicted organizational commitment. This aligns with prior studies indicating that mindfulness enhances attentional control, emotional regulation, and role clarity, thereby improving employee engagement and organizational identification (Ismail et al., 2013; Voci et al., 2016). For dancers, such traits may enhance adaptability, reduce interpersonal conflict, and foster alignment with institutional values.

Finally, mental well-being positively influenced organizational commitment, reinforcing previous findings on the role of psychological health in sustaining motivation and institutional loyalty (Darvishmotevali & Ali, 2020; Kundi et al., 2021; Panaccio & Vandenberghe, 2009). Given the immersive nature of professional dancers’ routines, mental well-being likely plays a central role in supporting both personal stability and long-term professional engagement (Jung, 2023).

Implications, limitations, and future directions

The findings highlight the importance of social and emotional competencies—particularly mindfulness and workplace spirituality—in promoting organizational commitment among professional female dancers. Given the interpersonal and emotionally expressive nature of dance, mindfulness may facilitate effective navigation of relational dynamics through improved clarity and emotional regulation. Similarly, workplace spirituality may enhance psychological safety and shared purpose, contributing to both individual well-being and organizational cohesion. These results have practical implications for artistic directors, choreographers, and administrators seeking to develop psychologically sustainable environments within the performing arts sector.

This study has several limitations. First, the sample was limited to female dancers in the United States, restricting the generalizability of the findings to other cultural or gender groups. Second, the study did not differentiate between dance genres (e.g., ballet vs. contemporary), which may reflect varying organizational norms and work environments. Third, the use of cross-sectional, self-reported data limits causal interpretation and does not capture longitudinal change.

Future research should employ longitudinal or mixed-method designs to better examine how workplace spirituality and mindfulness evolve across dancers’ careers. Incorporating additional organizational variables—such as job stress, burnout, team cohesion, and turnover intention—may provide a more comprehensive understanding of the psychological mechanisms that influence organizational commitment in high-performance artistic settings. Cross-cultural, cross-gender, and cross-genre studies are recommended to enhance the ecological validity and broader generalizability of the findings.

This study demonstrated that mental well-being plays a central role in enhancing organizational commitment among professional female dancers. Workplace spirituality was identified as a significant antecedent, positively influencing both mental well-being and organizational commitment. While mindfulness did not significantly affect mental well-being, it showed a direct association with organizational commitment, suggesting that its influence may be primarily behavioral rather than psychological.

These findings underscore the importance of integrating spiritual meaning and mindful awareness into the organizational culture of dance institutions. Fostering environments that support psychological well-being may enhance individual resilience and promote sustained organizational commitment in high-performance artistic settings. By positioning psychological resources as integral to organizational functioning, this study contributes to the literature on well-being and institutional engagement in emotion-intensive professions.

Acknowledgement: The authors thank all participants for their valuable contributions to this study. They also acknowledge the reviewers and editorial team for their constructive feedback and support.

Funding Statement: This research received no external funding. The dataset was accessed through a paid service and was personally funded by the authors.

Author Contributions: Kang-won Bae and Ja-young Sul contributed equally as co-first authors to the study’s conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, supervision, validation, visualization, manuscript drafting, and revision. Joon-ho Kim contributed to manuscript preparation and review. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The dataset used in this study was collected via Entrust Survey, a global research agency with a pre-registered participant panel. Eligibility criteria were defined by the authors, and the questionnaire was developed and administered accordingly. All responses were fully anonymized, and informed consent was obtained prior to participation.

Ethics Approval: This study involved anonymized primary data collected through an online survey administered by Entrust Survey. Informed consent was obtained during panel registration. In accordance with Articles 2 and 15 of the Bioethics and Safety Act of the Republic of Korea, the study was exempt from IRB review, as it did not involve identifiable or sensitive information.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Aboobaker, N., Edward, M., & Zakkariya, K. A. (2021). Workplace spirituality, well-being at work and employee loyalty in a gig economy: Multi-group analysis across temporary vs permanent employment status. Personnel Review, 51(9), 2162–2180. https://doi.org/10.1108/pr-01-2021-0002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Barbour, K., Clark, M., & Jeffrey, A. (2020). Expanding understandings of wellbeing through researching women’s experiences of intergenerational somatic dance classes. Leisure Studies, 39(4), 505–518. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1653354 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bergomi, C., Tschacher, W., & Kupper, Z. (2013). The assessment of mindfulness with self-report measures: Existing scales and open issues. Mindfulness, 4, 191–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0110-9 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bulut, C., & Culha, O. (2010). The effects of organizational training on organizational commitment. International Journal of Training and Development, 14(4), 309–322. [Google Scholar]

Carlson, S. M., Koenig, M. A., & Harms, M. B. (2013). Theory of mind. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 4(4), 391–402. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Cheung, R. Y., & Lau, E. N. S. (2021). Is mindfulness linked to life satisfaction? Testing savoring positive experiences and gratitude as mediators. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.591103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Chiu, W., Won, D., & Bae, J. S. (2020). Internal marketing, organizational commitment, and job performance in sport and leisure services. Sport, Business and Management: An International Journal, 10(2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1108/SBM-09-2018-0066 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Conway, N., Clinton, M., Sturges, J., & Budjanovcanin, A. (2015). Using self-determination theory to understand the relationship between calling enactment and daily well-being. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 36(8), 1114–1131. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Dal Corso, L., De Carlo, A., Carluccio, F., Colledani, D., & Falco, A. (2020). Employee burnout and positive dimensions of well-being: A latent workplace spirituality profile analysis. PLoS One, 15(11), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0242267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Dane, E., & Brummel, B. J. (2014). Examining workplace mindfulness and its relations to job performance and turnover intention. Human Relations, 67(1), 105–128. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726713487753 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Darvishmotevali, M., & Ali, F. (2020). Job insecurity, subjective well-being and job performance: The moderating role of psychological capital. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 87(1), 102462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102462 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Deci, E. L., & Porac, J. (2015). Cognitive evaluation theory and the study of human motivation. In The hidden costs of reward (pp. 149–176London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Self-determination theory. Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, 1(20), 416–436. [Google Scholar]

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 403–425. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Emre, O., & De Spiegeleare, S. (2021). The role of work-life balance and autonomy in the relationship between commuting, employee commitment and well-being. The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(11), 2443–2467. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585192.2019.1583270 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Farrer, R. (2014). The creative dancer. Research in Dance Education, 15(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2013.786035 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Fisher, C. D. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 384–412. [Google Scholar]

Garg, N. (2017). Workplace spirituality and employee well-being: An empirical exploration. Journal of Human Values, 23(2), 129–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0971685816689741 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Gronek, P., Gronek, J., Karpińska, A., Dobrzyńska, M., & Wycichowska, P. (2023). Is dance closer to physical activity or spirituality? A philosophical exploration. Journal of Religion and Health, 62(2), 1314–1323. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01354-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Guite, H. F., Clark, C., & Ackrill, G. (2006). The impact of the physical and urban environment on mental well-being. Public Health, 120(12), 1117–1126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2006.10.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Guzeller, C. O., & Celiker, N. (2020). Examining the relationship between organizational commitment and turnover intention via a meta-analysis. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(1), 102–120. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-05-2019-0094 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Halladay, J. E., Dawdy, J. L., McNamara, I. F., Chen, A. J., Vitoroulis, I. et al. (2019). Mindfulness for the mental health and well-being of post-secondary students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 10, 397–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0979-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Han, Y. S., & Kim, J. H. (2021). Performing arts and sustainable consumption: Influences of consumer perceived value on ballet performance audience loyalty. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 31(1), 32–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1871240 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ismail, H. A. K., Coetzee, N., Du Toit, P., Rudolph, E. C., & Joubert, Y. T. (2013). Towards gaining a competitive advantage: The relationship between burnout, job satisfaction, social support and mindfulness. Journal of Contemporary Management, 10(1), 448–464. [Google Scholar]

Jain, P., Duggal, T., & Ansari, A. H. (2019). Examining the mediating effect of trust and psychological well-being on transformational leadership and organizational commitment. Benchmarking: An International Journal, 26(5), 1517–1532. https://doi.org/10.1108/bij-07-2018-0191 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jalilianhasanpour, R., Asadollahi, S., & Yousem, D. M. (2021). Creating joy in the workplace. European Journal of Radiology, 145, 1100191. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrad.2021.110019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Jeon, K. S., & Choi, B. K. (2021). Workplace spirituality, organizational commitment and life satisfaction: The moderating role of religious affiliation. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 34(5), 1125–1143. https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-01-2021-0012 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Joeng, J. R. (2023). A validation study of the Korean version of the interpersonal mindfulness scale. Korean Journal of Counseling, 24(4), 163–186. [Google Scholar]

Jung, S. H. (2023). Does workplace spirituality increase self-esteem in female professional dancers? The mediating effect of positive psychological capital and team trust. Religions, 14(4), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel14040445 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Jung, S. H., Kim, J. H., Cho, H. N., Lee, H. W., & Choi, H. J. (2021). Brand personality of Korean dance and sustainable behavioral intention of global consumers in four countries: Focusing on the technological acceptance model. Sustainability, 13(20), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132011160 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2015). Mindfulness. Mindfulness, 6(6), 1481–1483. [Google Scholar]

Kim, D. J., & Han, S. Y. (1998). A study of construction validation of individuality-relatedness scale. Korean Journal of Social and Personality Psychology, 12(1), 71–93. Retrieved from: https://accesson.kr/ksppa/assets/pdf/25522/journal-12-1-71.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Kim, J. H., Jung, S. H., Seok, B. I., & Choi, H. J. (2022). The relationship among four lifestyles of workers amid the COVID-19 pandemic (work-life balance, YOLO, minimal life, and staycation) and organizational effectiveness: With a focus on four countries. Sustainability, 14(21), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.3390/su142114059 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kluemper, D. H., Little, L. M., & DeGroot, T. (2009). State or trait: Effects of state optimism on job-related outcomes. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 30(2), 209–231. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.591 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Krajcsák, Z. (2020). The interdependence between the extended organizational commitment model and the self-determination theory. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 17(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/jamr-02-2019-0030 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kraus, R. (2014). Transforming spirituality in artistic leisure: How the spiritual meaning of belly dance changes over time. Journal For the Scientific Study of Religion, 53(3), 459–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/jssr.12136 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kundi, Y. M., Aboramadan, M., Elhamalawi, E. M., & Shahid, S. (2021). Employee psychological well-being and job performance: Exploring mediating and moderating mechanisms. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 29(3), 736–754. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-05-2020-2204 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lambert, E. G., Leone, M., Hogan, N. L., Buckner, Z., Worley, R. et al. (2021). To be committed or not: A systematic review of the empirical literature on organizational commitment among correctional staff. Criminal Justice Studies, 34(1), 88–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2020.1762082 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, H. W., & Kim, J. H. (2020). Brand loyalty and the Bangtan Sonyeondan (BTS) Korean dance: Global viewers’ perceptions. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 30(6), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2020.1842415 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Lee, J. Y., & Lim, J. M. (2017). The effect of mindfulness on their organizational commitment of flight attendants: Focused on the mediating effect of job satisfaction. Journal of The Korea Convergence Society, 8(11), 331–342. Retrieved from: http://www.riss.kr/link?id=A103842924. [Google Scholar]

Luthans, K. W., Lebsack, S. A., & Lebsack, R. R. (2008). Positivity in healthcare: Relation of optimism to performance. Journal of Health Organization and Management, 22(2), 178–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/14777260810876330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Magnier-Watanabe, R., Uchida, T., Orsini, P., & Benton, C. (2017). Organizational virtuousness and job performance in Japan: Does happiness matter? International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 25(4), 628–646. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-10-2016-1074 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Wainwright, R., Das Gupta, M., Fradley, E. et al. (2002). Maternal mind-mindedness and attachment security as predictors of theory of mind understanding. Child Development, 73(6), 1715–1726. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Milliman, J., Czaplewski, A. J., & Ferguson, J. (2003). Workplace spirituality and employee work attitudes: An exploratory empirical assessment. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 16(4), 426–447. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810310484172 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Moon, Y. J. (2011). Reliability and validity of the multiple commitment scale: Focused on the organizational commitment, career commitment, and job commitment. Korean Academy of Human Resource Management, 9, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781784711740.00034 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ng Fat, L., Scholes, S., Boniface, S., Mindell, J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2017). Evaluating and establishing national norms for mental wellbeing using the short Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-being Scale (SWEMWBS): Findings from the Health Survey for England. Quality of Life Research, 26(5), 1129–1144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-016-1454-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Nordin-Bates, S. M. (2020). Striving for perfection or for creativity? A dancer’s dilemma. Journal of Dance Education, 20(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/15290824.2018.1546050 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Nordin-Bates, S. M., Hill, A. P., Cumming, J., Aujla, I. J., & Redding, E. (2014). A longitudinal examination of the relationship between perfectionism and motivational climate in dance. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 36(4), 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2013-0245. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Panaccio, A., & Vandenberghe, C. (2009). Perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and psychological well-being: A longitudinal study. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 75(2), 224–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2009.06.002 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pawar, B. S. (2016). Workplace spirituality and employee well-being: An empirical examination. Employee Relations, 38(6), 975–994. https://doi.org/10.1108/er-11-2015-0215 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pawar, B. S. (2024). A review of workplace spirituality scales. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 37(4), 802–832. https://doi.org/10.1108/jocm-04-2023-0121 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pouwer, F., Schram, M. T., Iversen, M. M., Nouwen, A., & Holt, R. I. G. (2020). How 25 years of psychosocial research has contributed to a better understanding of the links between depression and diabetes. Diabetic Medicine, 37(3), 383–392. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14227. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pratscher, S. D., Wood, P. K., King, L. A., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2019). Interpersonal mindfulness: Scale development and initial construct validation. Mindfulness, 10, 1044–1061. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-1057-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Preckel, K., Kanske, P., & Singer, T. (2018). On the interaction of social affect and cognition: Empathy, compassion and theory of mind. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 19, 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Ramlall, S. J. (2008). Enhancing employee performance through positive organizational behavior. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 38(6), 1580–1600. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2008.00360.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Rego, A., & Pina e Cunha, M. (2008). Workplace spirituality and organizational commitment: An empirical study. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 21(1), 53–75. https://doi.org/10.1108/09534810810847039 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Riasudeen, S., & Singh, P. (2021). Leadership effectiveness and psychological well-being: The role of workplace spirituality. Journal of Human Values, 27(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1177/09716858209473 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sauer, S., Walach, H., Schmidt, S., Hinterberger, T., Lynch, S. et al. (2013). Assessment of mindfulness: Review on state of the art. Mindfulness, 4, 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-012-0122-5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Shapiro, S. L., Carlson, L. E., Astin, J. A., & Freedman, B. (2006). Mechanisms of mindfulness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(3), 373–386. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20237. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sungu, L. J., Weng, Q., & Xu, X. (2019). Organizational commitment and job performance: Examining the moderating roles of occupational commitment and transformational leadership. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 27(3), 280–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12256 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Assche, A. (2017). The future of dance and/as work: Performing precarity. Research in Dance Education, 18(3), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1080/14647893.2017.1387526 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Rens, F. E., & Heritage, B. (2021). Mental health of circus artists: Psychological resilience, circus factors, and demographics predict depression, anxiety, stress, and flourishing. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 53(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2020.101850 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Voci, A., Veneziani, C. A., & Fuochi, G. (2019). Relating mindfulness, heartfulness, and psychological well-being: The role of self-compassion and gratitude. Mindfulness, 10(2), 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-018-0978-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Voci, A., Veneziani, C. A., & Metta, M. (2016). Affective organizational commitment and dispositional mindfulness as correlates of burnout in health care professionals. Journal of Workplace Behavioral Health, 31(2), 63–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/15555240.2015.1047500 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wood, K. (2021). UK dance graduates and preparation for freelance working: The contribution of artist-led collectives and dance agencies to the dance ecology. Theatre, Dance and Performance Training, 12(4), 600–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/19443927.2021.1934530 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Zollars, I., Poirier, T. I., & Pailden, J. (2019). Effects of mindfulness meditation on mindfulness, mental well-being, and perceived stress. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 11(10), 1022–1028. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2019.06.005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools