Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Testing the internal factor reliability of an Organisational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) measure for a South African higher education setting

Department of Human Resource Management, University of South Africa, Johannesburg, 0003, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Mariette Coetzee. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 627-634. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065791

Received 03 September 2024; Accepted 11 January 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

This study developed and tested the internal reliability of a 27-item Organisational Citizenship Behaviour (OCB) scale for higher education institutions. Participants were a probability sample of 452 (N = 452) university staff of a South African open-distance higher education institution (academics 46%, administrative staff 33%, professional and managerial staff 21%). The participants completed the Organisational Citizenship Behaviour questionnaire. Exploratory factor analysis identified a four-construct measurement model for organisational citizenship behaviour: altruism, civic virtue, sportsmanship, and sense of duty and consideration. The sense of duty and consideration is the only factor not previously identified as a factor of OCB. The results indicated that the Organisational Citizenship Behaviour questionnaire scores are reliable for measuring citizenship among higher education institution staff. The study findings add to the existing knowledge of organisational citizenship behaviour within the open-distance higher education environment.Keywords

Employees are social creatures with an innate desire to work with coworkers, demonstrating organisational citizenship behaviour (OCB) (Huang & Yuan, 2023). It is, however, not only co-workers benefiting from OCB but also the organisation, and, as further research indicated, external stakeholders such as customers. Researchers have increasingly outlined the importance of OCB to the successful functioning of organisations, and organisations realise employees are the ultimate key to organisational success. Although researchers agree on the multidimensionality of OCB, differences exist on how to distinguish the sub-dimensions of OCB. Two approaches dominate the theory on OCB. The approach based on the nature of OCB (Organ, 1990) recognises the five-dimensional framework (altruism, conscientiousness, sportsmanship, courtesy, and civic virtue). In contrast, the target-based approach of OCB recognises three stakeholders, namely individuals, the organisation and customers (Ma et al., 2021). OCB involves the discretionary behaviour of employees that does not form part of an employee’s job description yet is critical to the success of the organisation (Bateman & Organ, 1983; Soelton et al., 2020). OCB practices depict an employee’s sacrifice and commitment to the organisation that will ensure organisational effectiveness and efficiency (Ridwan et al., 2020).

OCB plays an important role in higher education staff’s efficiency and productivity, significantly impacting the performance of colleges and universities (Ramalakshmi & Ravindran, 2021). Not only did the COVID-19 pandemic necessitate changes to the nature of work, but it also changed the expectations of both employers and employees. The traditional conceptualisation of OCB is no longer aligned with contemporary work environments, specifically concerning higher education institutions and remote working environments. Due to the unique characteristics of higher education institutions, such as service orientation and intangibility, organisational dynamics, and diverse organisational and workplace settings, there is a need for nuanced approaches to conceptualising OCB.

This study thus aimed to determine the internal factor reliability of OCB in a higher education environment.

Measurements of organisation citizenship behaviour

Various definitions of OCB exist, but the understanding is central to all definitions that OCB involves voluntary extra-role behaviour to benefit the organisation. Organ (1990) proposed a five-dimensional model of OCB consisting of altruism, courtesy, sportsmanship, consciousness, and civic virtue. Organ expanded this model to include two additional dimensions, peace-keeping and cheer-leading (Organ, 1990). Altruism refers to employees assisting their co-workers to perform their jobs. A culture of sharing and collaboration with other colleagues is thus adopted. This is done without expecting any reward and to benefit the organisation. The study by Piatak and Holt (2020) built on this definition and stated that employees display OCB for the team’s benefit instead of serving self-interest. Employees who display courtesy are respectful, empathetic, and helpful towards their colleagues. Sportsmanship involves having a positive outlook and tolerating minor issues and inconveniences (Wan, 2016). Conscientiousness focuses on loyalty, responsibility, reliability, and acting in the organisation’s best interest. Civic behaviours relate to how well employees associate themselves with the organisation (Ghavifekr & Adewale, 2019). It involves support for the organisation, such as attending events arranged by the organisation, representing the organisation when required, attending meetings, and contributing inputs to organisational policies.

Williams and Anderson (1991) defined OCB according to the targets of OCB and identified behaviour for the benefit of other individuals or colleagues and behaviour for the benefit of the organisation. Williams and Anderson’s (1991) categorisation scheme captured Organ’s dimensions but also interpersonal helping (Venkataramani & Dalal, 2007) and interpersonal facilitation (Treadway et al., 2007). The OCB aimed at the organisation included Organ’s dimensions of compliance, civic virtue, and sportsmanship. It also captured voice behaviour (Van Dyne & LePine, 1998) and advancing an organisation’s image (Baker et al., 2006).

Employees’ OCB toward customers has gained interest as customer service and meeting customers’ needs became a strategic priority to organisations. Bettencourt, Gwinner, and Meuter developed a three-dimensional OCB model in 2001. These three dimensions included promoting the organisation and its services, customer service, and involvement in service orientation (Bettencourt & Brown, 1997). A study by Pattanayak et al. (2003) identified three dimensions of OCB: sharing and involvement, organisational ownership, and professional commitment.

Further research concluded that the original five-dimensional model of OCB could be reduced to a three-factor model by removing conscientiousness and combining altruism and courtesy to form a helping dimension (Podsakoff et al., 2016). This resulted in a three-factor model of helping behaviour, civic virtue, and sportsmanship. Biswas and Mazumder (2017), however, divided OCB into two types by grouping all behaviours directed at individuals (courtesy and altruism) and behaviours benefiting the organisation (conscientiousness, sportsmanship, and civic virtue).

Avci (2016) studied the effects of principal leadership styles on OCB and identified the following nine dimensions: Institutional identification, administrative contribution, sacrifice, being thoughtful and compatible, team spirit and positive communication. Johnson’s (2016)study identified a stewardship mindset as an important component of OCB. Ummah and Athambawa (2018) identified three OCB constructs: caring for and assisting others, cooperativeness, and being reliable and dutiful. Pradhan and Mishra (2019) identified work involvement and organisational ambassadorship, in addition to civic virtue and conscientiousness, as dimensions of OCB.

Ma et al. (2021) identified a three-dimensional OCB structure based on OCB directed at individuals (altruism, courtesy), OCB directed at organisations (conscientiousness and sportsmanship), and OCB directed at customers (extra-role customer service and cooperation).

Table 1 provides a summary of the OCB constructs identified by various studies.

Most studies on OCB behaviour identified similar constructs, with the most common constructs being Altruism and Civic virtue. A study by Bogler and Somech (2023) on OCB during COVID-19 identified the following OCB behaviours: Promoting academic achievement, investing extra time in lecturing, providing emotional and academic support to students, mastering technology, complying with COVID-19 regulations and coping with role changes due to COVID-19.

With regard to the higher education context, this study outlined a sense of duty and consideration as an additional construct of OCB.

Because educational institutions serve society, an additional burden is on employees to engage in OCB. An unwillingness to engage in OCB will thus not only disadvantage the institution but also have a ripple effect throughout society. Without employees willingly performing these tasks, higher education institutions will fail to successfully guide students to complete their studies and contribute to the country’s economic prosperity.

The study aimed to develop and test the internal reliability of a scale for measuring OCB at an open-distance higher education institution. The following research question guided the study: What are the key factors of OCB at higher education institutions in South Africa?

This study used a cross-sectional census approach to collect respondents’ data using a questionnaire. All employees of the population were invited to participate in the study. Using a census survey ensured a sufficient response rate, which resulted in higher statistical confidence. The margin of error was 4% according to the margin error calculator, and hence, 452 responses were reasonable and deemed sufficient for data analysis. The sample comprised 452 of 5471 employees at a South African open-distance higher education institution. The respondents were categorized by race, gender, age, qualification, job tenure, and job level.

Ethics clearance was granted by the higher education institution’s research ethics committee (2018_HRM_003). Participants consented to participate and completed the survey online. The data was secured by password protection and stored in a locked location.

Concerning race, 45.1% of the respondents were white, 42.7% of the participants were Blacks, 7.1% were Indian, and 4,4% were colored. 0,6% were from the other category, with only 0.4% specifying they were Asian. The remaining 0.2% did not specify their race. There were 38.3% males and 61.7% females. Concerning age, the highest percentage of the participants (35.6%) were from the 46–55 years age group, followed by the 36–45 years age group (24.6%), the 50–65 years age group (21.0%), the 26–35 years age group (18.6%), and the 25 years and younger age group (0.2%). Concerning qualifications, 27.4% had a Master’s degree, 26.3% had a doctoral/PhD degree, 16.5% have an honors degree, 13.4% had a bachelor’s degree, 10.2% have a certificate or diploma, 5.3% have matric, and 0.8% have indicated other. Regarding job tenure, 43.95% were employed for more than 11 years, 34.08% were employed for 6–10 years, 20.40% were employed for 1–5 years, and 1.57% were employed at the institution for less than one year. Regarding the job level, 46.0% of respondents are academic staff, 32.3% are administrative employees, and 17.9% are managers. The missing data concerning demographic information was 2.5% and did not influence the analysis regarding bias.

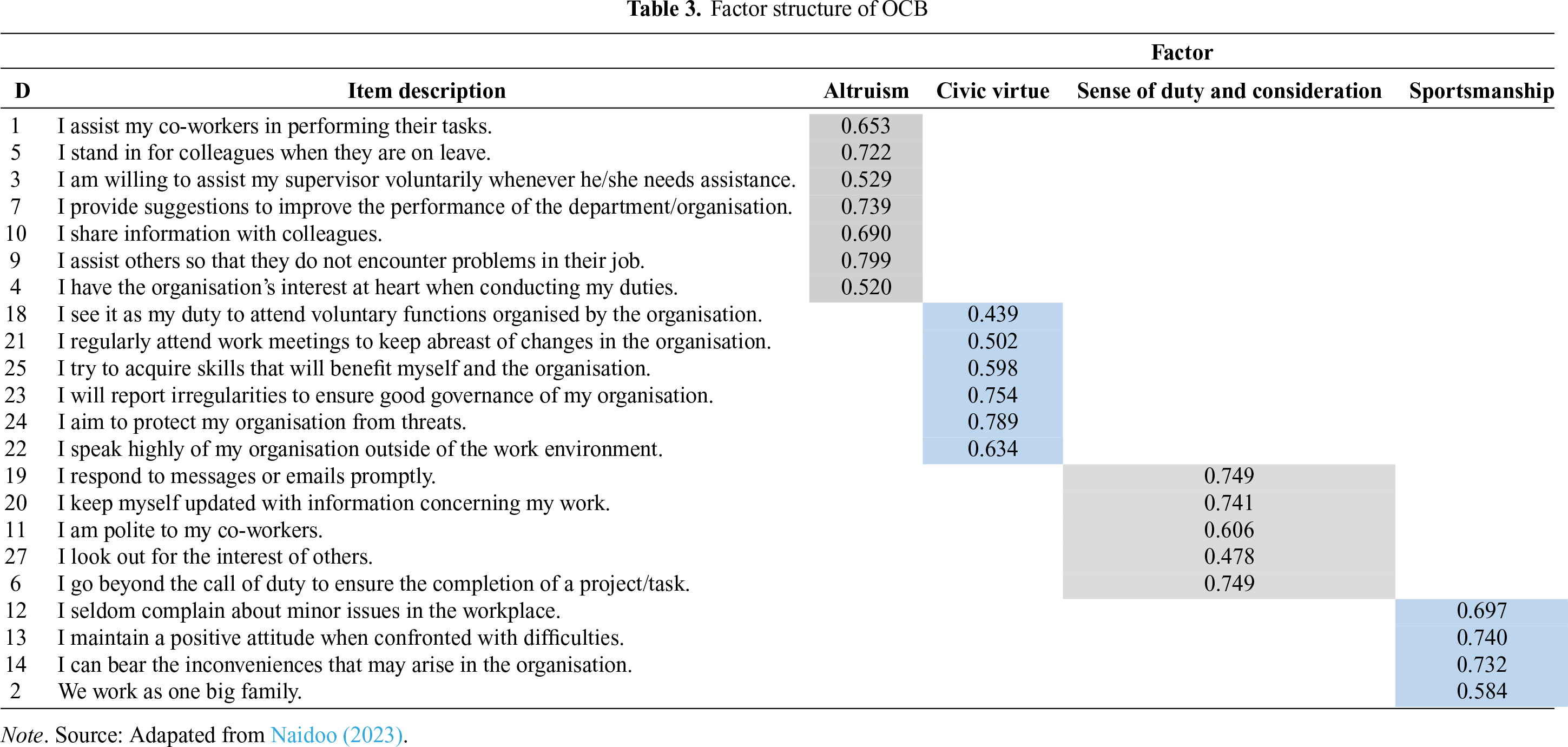

The OCB questionnaire consisted of 27 items. The items were developed by referring to the constructs of OCB as identified by previous studies on OCB. Items were phrased to refer to situations in a higher education institution. Four OCB factors were identified: Altruism (7 items, I provide suggestions to improve the performance of the department/organisation), civic virtue (6 items, I speak highly of my organisation outside of the work environment), sense of duty and consideration (5 items, I keep myself updated with information concerning my work), and sportsmanship (4 items, I can bear the inconveniences that may arise in the organisation).

The items were scored on a 6-point Likert Scale (1 = totally disagree; 6 = totally agree). A pilot study was conducted on 20 individuals from the Department of Human Resource Management at the Higher Education Institution to determine the suitability and validity of the questions.

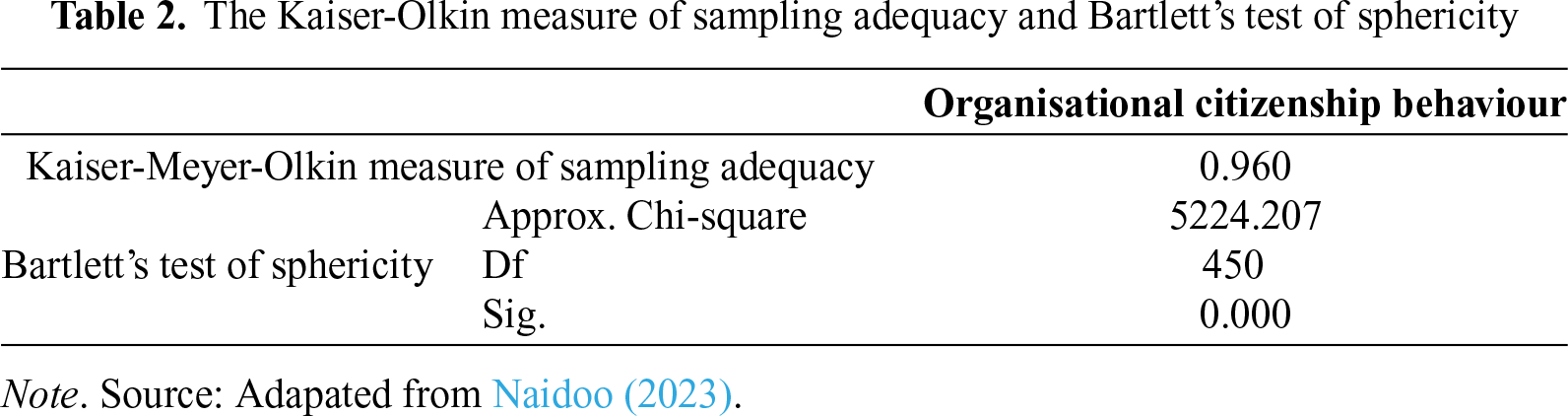

The data set was analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS), version 22.0 of 2013. Exploratory factor analysis (EFA) using Principal Axis Factoring as an extraction method with Promax rotation was used. The suitability of the data for factor analysis was established by analysing the results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s tests. The KMO value should be should be greater than 0.70. Values between 0.70 and 0.80 are average, between 0.80 and 0.90 is good, and between 0.90 and 1.00 is excellent. KMO values between 0.50 and 0.60 are flawed but acceptable (Sharma, 1996). These tests confirmed that the scale items correlated adequately, and Eigenvalues larger than 1.00 were used as the factor criterion. A cut-off score of 0.30 was used for factor loadings. The reliability of the OCB measure was assessed using a Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient cut-off score of 0.70. Murphy and Davidshofer (1988) state that Cronbach values <0.60 are unacceptable; 0.70 is low, between 0.80 and 0.90 are moderate, and >0.90 is high.

Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA)

Table 2 presents the results to confirm the suitability of the data for factor analysis. The value for the KMO measures of sampling adequacy was 0.96 and well above the threshold of 0.60 (Kaiser, 1970). The significance level of Bartlett’s test of sphericity was 0 and below the threshold of p < 0.05 (Bartlett, 1954). The Kaiser-Olkin Measure of Sampling Adequacy and Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity results indicated that factor analyses were appropriate. However, items 8, 15, 16, 17, and 22 were eliminated from further analysis because these items did not meet the reliability criteria of factor loadings above 0.30 (Veth et al., 2018).

The principal-axis factor analysis revealed the presence of four factors with eigenvalues exceeding 1.0, which cumulatively explained 64.44% of the variance in OCB. The factor loadings were all above 0.30 (Veth et al., 2018) and considered suitable for inclusion. The factor loadings in the pattern matrix, as illustrated in Table 3, were analysed in line with the theory and labeled as follows:

Factor 1: Altruism

Factor 2: Civic virtue

Factor 3: Sense of duty and consideration

Factor 4: Sportsmanship

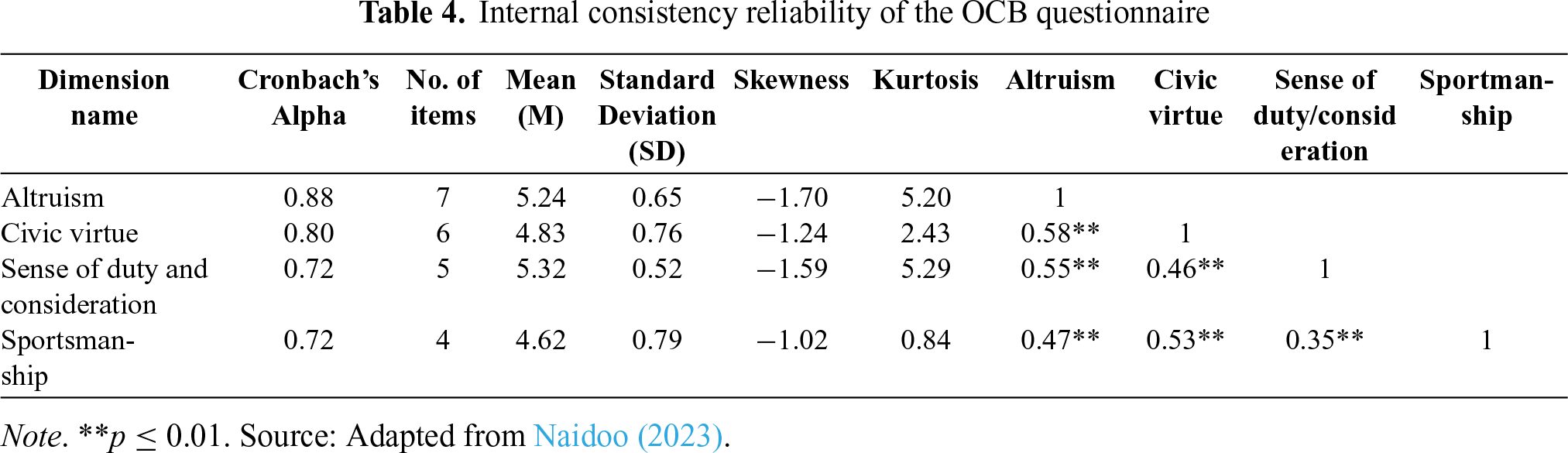

Descriptive statistics and bi-variate correlations

Table 4 presents the descriptive data analysis, including the identified factors’ reliability coefficients, skewness, and kurtosis values. Concerning reliability, all the factors had Cronbach’s alpha values in the range of 0.72 to 0.88. Cronbach’s alpha is a measure of scale reliability that assesses how well several items together measure a construct. According to Bryman et al. (2014), a coefficient alpha of 0.6 or less is unacceptable. The following reliability scores were determined for each of the OCB factors:

• Altruism (7 items): α = 0.88.

• Civic virtue (6 items): α = 0.80.

• Sense of duty and consideration (5 items): α = 0.72.

• Sportsmanship (4 items): α = 0.72.

The factor with the highest mean score was Altruism (M = 5.24, SD = 0.65), and the factor with the lowest mean score was sportsmanship (M = 4.62, SD = 0.79). The skewness values indicated that all the constructs had a negative skew but fell within the range of −2 to +2 and between −7 and +7 for kurtosis to be considered acceptable and for a normal distribution to occur (Kline, 2011).

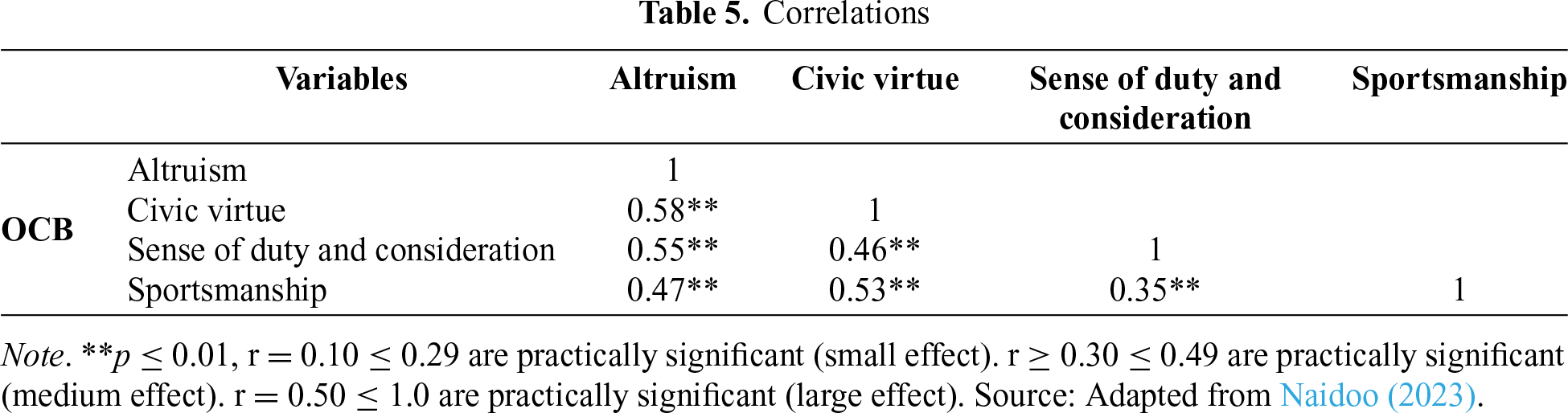

Correlation was carried out using the Pearson product-moment correlation to measure the strength and direction of the relationship between the OCB factors. According to Cohen (1992), the correlations (r-values) from 0–0.30 indicate a small correlation. Correlation coefficients between 0.31 and 0.49 indicate a moderate correlation, and correlation coefficients between 0.50 and 1 indicate a very high correlation. With reference to Table 5, the correlation coefficients of r = 0.50 ≤ 1.0 are practically significant (large effect). Hence, the correlation between altruism, civic virtue, and sense of duty/consideration was practically significant. The correlation between civic virtue and sportsmanship was also practically significant. None of the subscales presented very low correlations, indicating moderate to large internal validity between the subscales.

Based on the findings above, the 27-item OCB scale for employees at higher education institutions provides a reliable internal factor structure. The identified factors are internally reliable in terms of factor loadings (>0.30) and Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients (α ≥ 0.70).

The study aimed to determine the internal reliability of the OCB factor structure as applicable in a higher education context. An exploratory factor analysis was carried out. The exploratory factor analysis revealed 4 factors. A KMO of 0.96 was obtained. All the items had factor loadings equal to or greater than 0.30. The total variance explained was 64.44 percent. All the factors had Cronbach’s alpha values in the range of 0.72 to 0.88, which indicates high internal consistency. The items discriminated sufficiently since all the items had responses at all points, with no item having a median close to one of the extremes. The values of asymmetry and kurtosis met the requirements as all skewness values were less than 2, and the kurtosis values were less than 7. The principle of normality was thus not violated.

Overall, the results confirm the internal reliability of the OCB factor structure, and researchers and practitioners can use the OCB scale to assess OCB at a higher educational institution.

The factorial structure differs from the original scale by identifying 4 factors: Altruism, Civic virtue, Sense of duty and consideration, and Sportsmanship. Regarding the original 5-factor structure, conscientiousness and courtesy were not identified as factors. The sense of duty and consideration factor could be linked to the OCB structure of Ma et al. (2021), which identified a third factor of OCB directed at customers. Higher education staff deal with students and parents regularly and without experiencing a sense of duty, the interest and well-being of customers will be neglected. A sense of duty further concerns the value system of an employee and, as such, does not focus on serving the interest of other people or the organisation.

Theoretical and practical implications

The study contributes to an understanding of organisational citizenship behaviour within the context of higher education in the following ways: It confirms the role of altruism as a significant dimension of OCB, resonating with the findings of Pradhan and Mishra (2019). This finding confirms the importance of altruism for a supportive work environment. Regarding civic virtue, staff should be allowed to serve on committees and participate in decision-making. A sense of duty and consideration play an important role in the efficient functioning of departments and colleges. Cooperation and conscientiousness among committee members are prerequisites to enhancing the smooth running of an educational institution. Higher education institutions should recognise and unofficially reward staff members who display collegiality. Although sportsmanship was not regarded as the most important dimension of OCB, it does play a significant role in creating a culture of tolerance. In light of the challenges related to online teaching, employees must constantly deal with technological developments and online platform problems. This requires tolerance and a work culture of support to assist colleagues in coping with the work demands.

Given that most OCB measurements originated in non-service organisations, specific measurement scales for different higher education institution settings need to be researched to reach a consensus on the definition and measurement of OCB at higher education institutions.

HR practitioners and managers can use the OCB scale to measure and understand employees’ OCB performance. Performance key indicators should include OCB competencies, and OCB should be encouraged for all stakeholders. Higher education institutions could use the results of this study to recruit candidates who possess these OCB qualities.

Overall, the study adds to existing theories of OCB. It provides an understanding of how different dimensions of OCB are exhibited by university staff, which can help improve practices in higher education institutions.

The exploratory research on OCB was limited to a single distance higher education institution. Future studies should sample from several higher education institutions. This will ensure that the set of observed variables across different institutions accurately represents the underlying constructs of OCB. Future studies could consider collecting data from multiple sources, such as managers and customers, to avoid common method bias.

Culture, leadership, workload, supervisor support, and other institutional variables can also be included as influencers on OCB. It is recommended that future studies perform confirmatory factor analysis to identify poorly performing items and to refine and improve the measurement instrument. OCB behaviours are dynamic and change constantly. Future studies could investigate OCB fluctuations over time.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Linda Naidoo; data collection: Linda Naidoo; analysis and interpretation of results: Mariette Coetzee and Linda Naidoo; draft manuscript preparation: Mariette Coetzee. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This manuscript is based on data generated by a study. The data was gathered according to ethical principles, and the authors confirm the soundness of the data. The data can be accessed by contacting the authors of the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: This study included human subjects. Ethics clearance was granted by the higher education institution's research ethics committee. The ethics approval number is 2018_HRM_003.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Avci, A. (2016). Effect of leadership styles of school principals on organizational citizenship behaviours. Educational Research and Reviews, 11(11), 1008–1024. https://doi.org/10.5897/ERR2016.2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baker, T. L., Hunt, T. G., & Andrews, M. C. (2006). Promoting ethical behavior and organizational citizenship behaviors: The influence of corporate ethical values. Journal of Business Research, 59(7), 849–857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.02.004 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bartlett, M. (1954). A note on the mulitiplying factors for various chi square approximations. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, 16(2), 296–298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2517-6161.1954.tb00174.x [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bateman, T. S., & Organ, D. W. (1983). Job satisfaction and the good soldier: The relationship between affect and employee citizenship. Academy of Management Journal, 26, 587–595. https://doi.org/10.2307/255908 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bettencourt, I. A., & Brown, S. W. (1997). Contract employees: Relationships among workplace fairness, job satisfaction and prosocial service behaviors. Journal of Retailing, 73(1), 39–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-4359(97)90014-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Biswas, N., & Mazumder, Z. (2017). Exploring organizational citizenship behavior as an outcome of job satisfaction: A critical review. IUP Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(2), 7–16. [Google Scholar]

Bogler, R., & Somech, A. (2023). Organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) above and beyond: Teachers’ OCB during COVID-19. Amsterdam: Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2023.104183 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Bryman, A., Bell, E., Hirschsohn, P., Du Toit, JP., & Dos Santos, A. (2014). Research methodology: Business and management contexts. Cape Town, South Africa: Oxford University Press Southern Africa. [Google Scholar]

Cohen, J. W. (1992). Quantitative methods in psychology: A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ghavifekr, S., & Adewale, A. S. (2019). Can change leadership impact on staff organizational citizenship behaviour? A scenario from Malaysia. Higher Education Evaluation and Development, 13(2), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/HEED-08-2019-0040 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Graham, J. W. (1991). An essay on organizational citizenship behaviour. Employee Responsibilities and Rights Journal, 4(4), 249–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01385031 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Huang, W., & Yuan, C. (2023). Workplace ostracism and helping behaviour: A Cross-level investigation. Journal of Business Ethics, 190, 787–800. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-023-05430-z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Johnson, C. E. (2016). Organizational ethics: A practical approach. 3rd edition. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Kaiser, H. (1970). A second generation little jiffy. Psychometrika, 35(4), 401–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02291817 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modelling. 5th ed. New York, NY, USA: The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

Ma, E., Wang, Y., Xu, S., & Wang, D. (2021). Clarifying the multi-order multidimensional structure of organizational citizenship behavior: A cross-cultural validation. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 50, 83–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.12.008 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Murphy, K. R., & Davidshofer, C. O. (1988). Psychological testing: principles and applications. London, UK: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

Naidoo, L. (2023). The interrelationships between leadership, employee empowerment and organisational citizenship behaviour in an open-distance higher education institution. [Ph.D. thesis]. Pretoria, South Africa: University of South Africa. [Google Scholar]

Organ, D. W. (1990). The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behavior. In: Staw, B. M., & Cumming L. L. (Eds.Research in Organizational Behavior (vol. 12, pp. 43–72). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

Pattanayak, B., Misra, R. K., & Niranjana, P. (2003). Organizational citizenship behaviour: A conceptual framework and scale development. Indian Journal of Industrial Relations, 39(2), 194–204. [Google Scholar]

Piatak, J. S., & Holt, S. B. (2020). Disentangling altruism and public service motivation: Who exhibits organizational citizenship behaviour? Public Management Review, 22(7), 949–973. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1740302 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. B. (1997). Impact of organizational citizenship behaviour on organizational performance: A review and suggestions for future research. Human Performance, 10(2), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327043hup1002_5 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2016). Recommendations for creating better concept definitions in the organizational, behavioral, and social sciences. Organizational Research Methods, 19(2), 159–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428115624965 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Pradhan, A., & Mishra, S. (2019). Exploring individual difference in organizational citizenship behaviour in the academic context. KIIT Journal of Management, 15(1&2), 45–64. https://doi.org/10.23862/kiit-parikalpana/2019/v15/i1-2/190173 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ramalakshmi, K., & Ravindran, K. (2021). Influence of citizenship behaviour in the workplace on achieving organisational competitiveness. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 25(2), 247–265. https://doi.org/10.17512/pjms.2022.25.2.16 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ridwan, M., Mulyani, S. R., & Ali, H. (2020). Improving employee performance through perceived organizational support, organizational commitment and organizational citizenship behavior. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy, 11(12), 839–849. [Google Scholar]

Sharma, S. (1996). Applied multivariate techniques. New York, NY, USA: John Wiley and Sons. [Google Scholar]

Soelton, M., Visano, N. A., Noermijati, N., Ramli, Y., Syah, T. Y. R., et al. (2020). The implication of job satisfaction that influence workers to practice organizational citizenship behavior (OCB) in the workplace. Archives of Business Review, 8(5), 33–48. https://doi.org/10.14738/abr.85.8139 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Treadway, D. C., Ferris, G. R., Duke, A. B., Adams, G. I., & Thatcher, J. B. (2007). The moderating role of subordinate political skill on supervisors’ impressions of subordinate ingratiation and rating of subordinate interpersonal facilitation. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 848–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.848. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Ummah, S., & Athambawa, S. (2018). Organizational citizenship behavior and job satisfaction among non-academic employees of national universities in the Eastern province of Sri Lanka. American Journal of Economics and Business Management, 1(1), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.31150/ajebm.v1i1.8 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Van Dyne, L., Cummings, L. L., & McLean Parks, J. (1995). Extra-role behaviors: In pursuit of construct and definitional clarity (a bridge over muddied waters). In: Cummings, L. L., & Staw B. M. (Eds.Research in organizational behavior (vol. 17, pp. 215–285). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. [Google Scholar]

Van Dyne, L., & LePine, J. A. (1998). Helping and voice extra-role behaviors: Evidence of construct and predictive validity. Academy of Management Journal, 41, 108–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/256902 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Venkataramani, V., & Dalal, R. S. (2007). Who helps and harms whom? Relational antecedents of interpersonal helping and harming in organizations. Journal of Applied Pscyhology, 92(4), 952–966. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.952. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Veth, K. N., Van der Heijden, B. I., Korzilius, H. P., De Lange, A. H., & Emans, B. J. (2018). Bridge over a naging population: Examining longitudinal relations among human resource management, social support, and employee outcomes among bridge workers. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 574. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Wan, H. L. (2016). Organisational justice and citizenship behaviour in Malaysia. Singapore: Springer Science + Business Media Singapore Pte. Ltd. [Google Scholar]

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organizational commitment as predictors of organizational citizenship and in-role behaviors. Journal of Management, 17(3), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700305 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools