Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Chinese Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale (HCAS): Revision and validation integrating classical test theory and network analysis approaches

1 School of Educational Sciences, Hanshan Normal University, Chaozhou, 521041, China

2 School of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, School of Materials Science and Engineering, Hanshan Normal University, Chaozhou, 521041, China

3 School of Education and Psychology, Minnan Normal University, Zhangzhou, 363000, China

* Corresponding Author: Yuefu Liu. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(5), 661-669. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.068787

Received 06 June 2025; Accepted 05 September 2025; Issue published 24 October 2025

Abstract

Accurate assessment of climate anxiety is crucial, yet the cross-cultural transportability of existing instruments remains an open question. This study translated and validated the Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale for the Chinese context. A total of 959 students (females = 69.7%; M age = 19.60 years, SD = 1.40 years) completed the Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale, with the Climate Change Anxiety Scale and the Anxiety Presence Subscale served as criterion measures for concurrent validity. Test–retest reliability was evaluated with a subset after one month. Confirmatory factor analysis supported the original four-factor structure and measurement invariance across genders. Utilizing classical test theory and network analysis, the Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale demonstrated high internal consistency (McDonald’s ω = 0.936), acceptable test–retest reliability (r = 0.716), and solid convergent and discriminant validity. Total scores were significantly correlated with climate change anxiety and presence of anxiety, and the Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale scores showed superior predictive validity of anxiety presence over the Climate Change Anxiety Scale. Network analysis confirmed the scale’s structural stability and highlighted central symptoms. Overall, the Chinese Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale appears to yield reliable and valid scores for assessing climate anxiety in Chinese university students.Keywords

Over the past decade, climate change has emerged as not only one of the world’s most pressing environmental challenges, but also as an increasingly significant concern for psychological well-being (Clayton, 2020). For instance, the rising frequency and intensity of climate-related extreme weather events—including heatwaves, droughts, and heavy rainfall—have been linked to elevated public distress and clinical symptoms such as anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (Matthews et al., 2025; Mitchell et al., 2024; Mambrey et al., 2019), comprising “climate anxiety”. Climate anxiety is a psychological response to the perceived threat of climate change, characterized by persistent and sometimes overwhelming worry or distress about climate change, impacting individuals emotionally, cognitively, physiologically, and behaviorally (van Valkengoed et al., 2023). Among young people; 60% of respondents aged 16 to 25 reported feeling “very” or “extremely” anxious about climate change, frequently experiencing emotions such as distress, anger, and helplessness (Hickman et al., 2021). However, climate anxiety among young people is less well documented cross-culturally, calling for validated measures that would serve that purpose. We aimed to validate an existing climate anxiety measure in the Chinese context.

The climate anxiety: Construct and measures. Frequent extreme weather events not only provide tangible evidence of climate change but also heighten perceptions of uncertainty and future threat (Freeston et al., 2020, 2024; Ai et al., 2024). Such perceptions may intensify ongoing fear and worry (Ahmead et al., 2025), contributing to sustained psychological distress related to climate change (Clayton, 2020).

In light of these developments, the availability of valid and reliable instruments for measuring climate anxiety is critical to advancing both research and intervention. However, most existing scales were developed and validated within Western cultural contexts, and few have been adapted for non-English-speaking populations. Addressing this gap, Hogg et al. (2024) developed the Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale (HCAS), a multidimensional tool capturing affective symptoms, rumination, behavioral symptoms, and personal impact anxiety to climate change. While the HCAS has shown robust psychometric performance in Western samples, a validated Chinese version has been lacking, limiting research and practice in Chinese settings.

Measurement approaches. Classical Test Theory (CTT) is a widely applied framework for evaluating psychometric quality, including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, various forms of validity, and measurement invariance (DeVellis & Thorpe, 2021). It provides clear, interpretable indices of a scale’s overall performance. Network analysis, in contrast, conceptualizes psychological constructs as systems of interacting components, modeling each item of the construct as a node and their associations as edges to produce a dynamic visual representation. Centrality estimation, stability testing, and network comparison analyses can uncover direct item connections and core features, highlighting central items or dimensions as potential intervention targets (Borsboom & Cramer, 2013; Borsboom et al., 2021). Integrating CTT and network analysis: CTT establishes reliability and validity, while network analysis reveals the internal architecture and functional dynamics of the construct. Previous studies have shown the value of this integration: Fang et al. (2024) used CTT to confirm the scale’s reliability and validity, and network analysis to identify central items and their interconnections, thereby providing additional evidence of the scale’s structural consistency and internal coherence. Therefore, by using both approaches, we sought a more comprehensive view of the scale’s psychometric properties and structure.

The Chinese context. China has taken an active role in global climate governance, committing to peak carbon emissions by 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060 (Ministry of Ecology & Environment of the People’s Republic of China, 2021). These national commitments, coupled with the growing visibility of climate-related issues in media and public discourse, have increased young people’s exposure to climate narratives, which have influenced their cognition of climate change and, in turn, shaped their climate-related emotions and pro-environmental behaviors. Surveys of Chinese university students indicate high awareness and concern regarding the impacts of climate change, with many reporting negative emotions, including anxiety, worry, and a willingness to engage in climate governance behaviors (Wang et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2022). Such evidence underscores the relevance of culturally adapting and validating measures of climate anxiety for Chinese youth.

Goals of the study. The present study aimed to translate and culturally adapt the HCAS for Chinese university students, and to comprehensively evaluate its psychometric properties in this context. In addition to using classical test theory, we applied network analysis to visualize and explore the internal structure of climate anxiety. Our goal was to determine the reliability and validity of scores from a validated measure of climate anxiety in the Chinese context. Our specific questions were:

(1) What are the psychometric properties (factor structure, reliability, and validity) of the Chinese version of the HCAS among university students?

(2) How does network analysis complement classical test theory in revealing the structural characteristics and central symptoms of climate anxiety in this population?

(3) Does the scale demonstrate measurement invariance across gender?

This study recruited 959 Chinese university students (69.7% female; M = 19.60, SD = 1.40) from southeastern and central China through convenience sampling, who were allocated to four subsamples for item analysis, exploratory factor analysis, confirmatory factor analysis, and test–retest reliability assessment.

Three measures were included in this validation study: The Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale (HCAS; Hogg et al., 2024), Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS; Clayton & Karazsia, 2020) and Short State Anxiety Inventory (SSAI; Spielberger et al., 1983; Marteau & Bekker, 1992). The measures were translated into Chinese using back-translation by a professional English instructor, following standard cross-cultural adaptation procedures. Discrepancies were resolved under the guidance of a senior psychometrics expert and an expert panel reviewed the items for semantic accuracy and cultural relevance. A pilot test with 30 students confirmed clarity before minor revisions were made. These are described next.

Hogg climate anxiety scale (Primary measure)

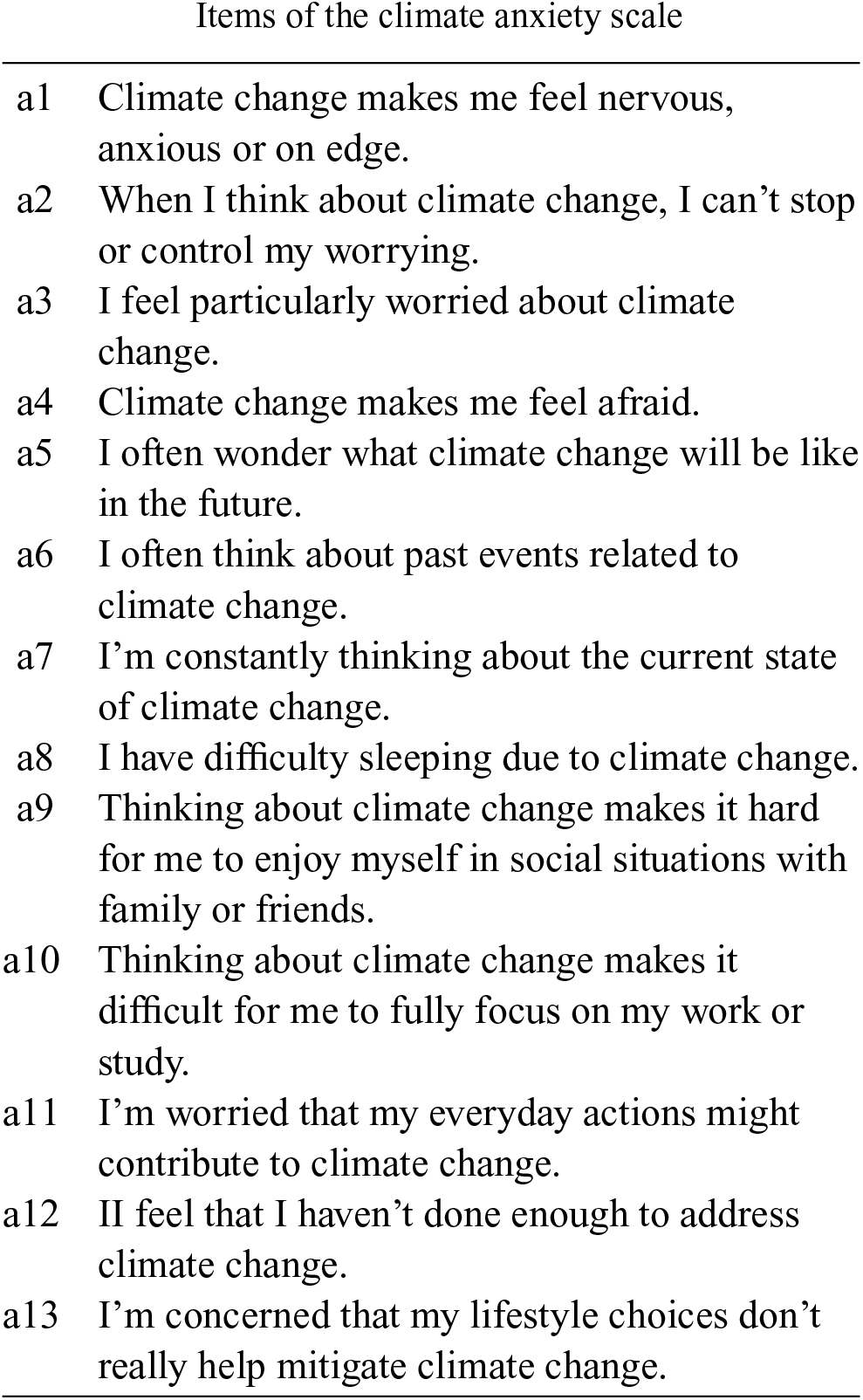

The Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale (HCAS; Hogg et al., 2024) is a 13-item instrument assessing anxiety responses to climate change and related environmental stressors across four dimensions: affective symptoms (4 items, e.g., “Feeling nervous, anxious or on edge”), rumination (3 items, e.g., “Unable to stop thinking about future climate change”), behavioral symptoms (3 items, e.g., “Difficulty sleeping”), and personal impact anxiety (3 items, e.g., “Feeling anxious about the impact of your personal behaviours on climate change”). Items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Never, 5 = Always); higher scores indicate greater climate anxiety, with no reverse-coded items. The full list of 13 items is provided in Appendix A.

Climate change anxiety scale (For concurrent validation)

The Climate Change Anxiety Scale (CCAS; Clayton & Karazsia, 2020) measures emotional and functional distress related to climate change with 9 items across two subscales: cognitive-emotional impairment and functional impairment (e.g., “Thinking about climate change makes it hard for me to concentrate”), rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Never, 5 = Always). Higher scores reflect greater anxiety. The Chinese version, translated and validated by Guo and Lyu (2023), demonstrated excellent internal consistency in the current study (McDonald’s ω = 0.940).

Short state anxiety inventory (For concurrent validation)

The Short State Anxiety Inventory (SSAI; Spielberger et al., 1983; Marteau & Bekker, 1992) comprises six items divided into two subscales: Presence of Anxiety and Absence of Anxiety. This study used the three-item Presence of Anxiety subscale (e.g., “I feel upset”), rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Never, 5 = Always). Higher scores indicate greater state anxiety. The Chinese version, validated by Tian et al. (2018), exhibited excellent internal consistency in this study (McDonald’s ω = 0.917).

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of Hanshan Normal University. All participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained from each student. The students were in four samples for each of the major validation tasks.

Sample 1 was used for item analysis. Using convenience sampling, 220 responses were collected online via the Wenjuanxing platform, of which 202 were valid (valid response rate: 91.8%). The sample included 53 males and 149 females, with a mean age of 19.40 years (SD = 1.51).

Sample 2 was used for exploratory factor analysis (EFA). Similarly recruited through convenience sampling and the Wenjuanxing platform, this sample comprised 310 valid responses out of 335 collected (valid response rate: 92.5%). Participants included 84 males and 226 females, with a mean age of 19.97 years (SD = 1.51).

Sample 3 was used for confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), criterion-related validity, and reliability analysis. Data were obtained via both online administration (Wenjuanxing) and on-site surveys. Of the 488 questionnaires distributed, 447 were valid (valid response rate: 91.6%). This sample consisted of 154 males and 293 females, with a mean age of 19.34 years (SD = 1.19).

Sample 4 was used to assess test–retest reliability. One hundred students were randomly selected from Sample 2 and were retested one month after the initial survey, resulting in 77 matched pairs. This subsample included 18 males and 59 females, with a mean age of 19.09 years (SD = 0.81).

As a token of appreciation, participants received a small gift upon completing the questionnaires.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS 27.0, Mplus 8.3, Amos 28, and R 4.4.3. Specifically, Item analysis was performed on Sample 1 in SPSS 27.0. Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted on Sample 2 using principal feature extraction with varimax rotation to examine the scale’s factor structure.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) and Validity Assessment: CFA was performed on Sample 3 in both Mplus 8.3 and Amos 28 to evaluate model fit, convergent validity, and discriminant validity. Reliability was assessed via Cronbach’s α, McDonald’s ω, split-half reliability, and test–retest reliability; criterion-related validity was also examined.

Network Analysis: Network modeling of climate anxiety items was conducted in R. Each item was represented as a node, with statistical direct associations depicted as edges. Centrality indices and network stability were calculated. The Network Comparison Test assessed structural differences across subgroups.

During manuscript preparation, ChatGPT-4 (OpenAI, San Francisco, CA, USA) was used solely for language polishing and grammar checks to improve readability. All AI-generated suggestions were critically reviewed and finalized by the authors. The research design, methodology, data analysis, and conclusions were developed independently without AI assistance. No confidential or personally identifiable data were entered into the tool.

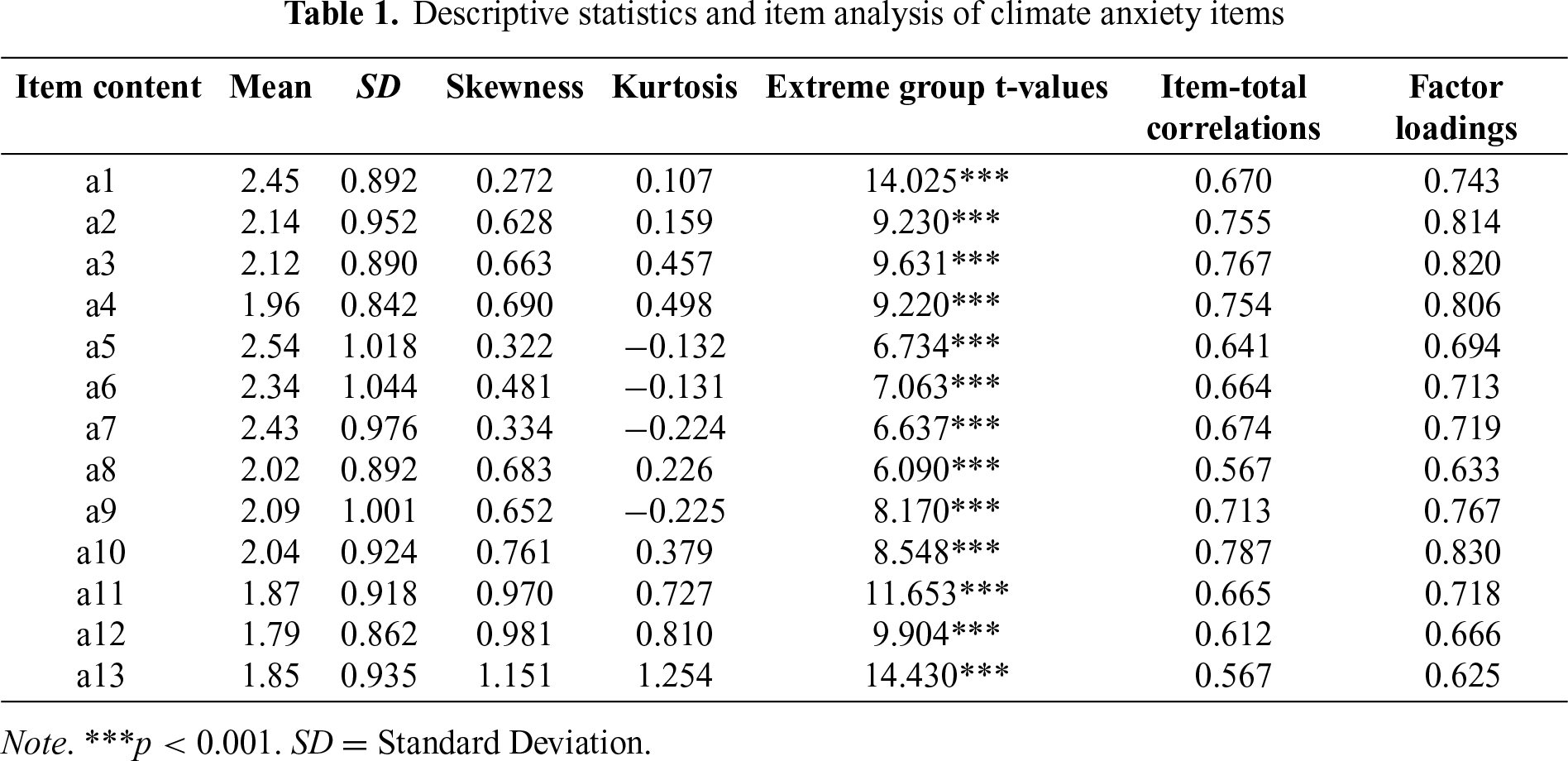

The Sample 1 item analysis results (see Table 1) indicated that the correlation coefficients between each item of the HCAS and the total scale score ranged from 0.567 to 0.787 (p < 0.001). The extreme group method was employed, whereby participants were ranked based on their total HCAS scores, with the top 27% and bottom 27% forming the high-scoring and low-scoring groups, respectively. Independent samples t-tests were used to examine the differences between these high and low groups for each item; all p-values were less than 0.001. Furthermore, the Cronbach’s α coefficient for the total scale did not increase when any individual item was removed. These findings suggest that all items of the HCAS possess good discriminatory power.

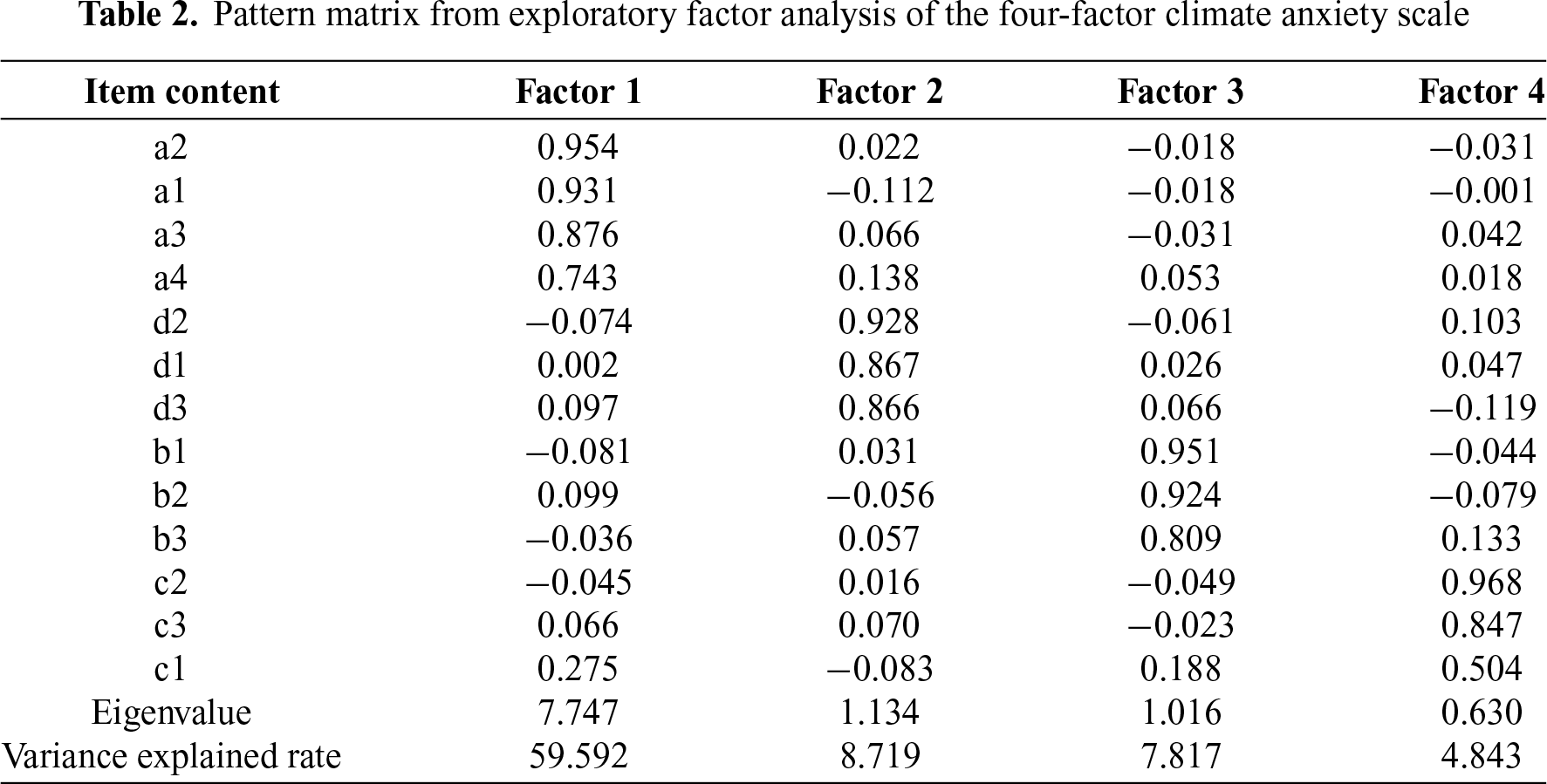

EFA was conducted on Sample 2. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value was 0.924 and Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded χ2 = 3218.416 (p < 0.001), indicating that the data were suitable for factor analysis. Principal component analysis with Promax oblique rotation identified four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1, consistent with the theoretical structure of the scale. The communality values ranged from 0.635 to 0.874, and item factor loadings in the pattern matrix ranged from 0.504 to 0.968 (see Table 2), accounting for a cumulative variance of 80.972%. The four factors were: (1) affective symptoms, (2) personal impact anxiety, (3) rumination, and (4) behavioral symptoms.

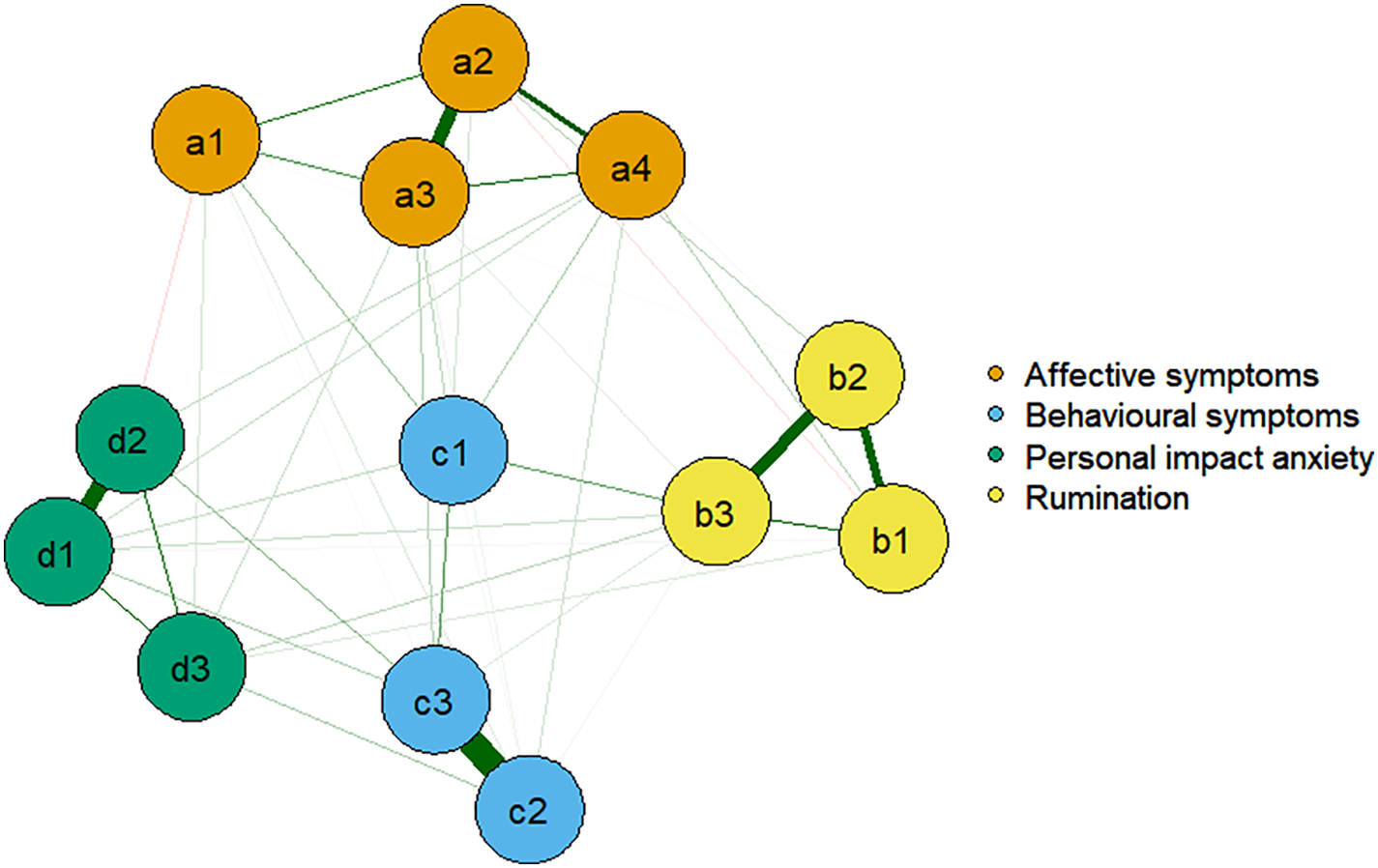

To further validate the factor structure, a network analysis was performed using the qgraph package in R. Items were visualized as nodes and their direct correlations as edges, resulting in a clear visual representation of the item network. As shown in Figure 1, the network exhibited a highly clustered and centralized structure, with 46 non-zero weighted edges and an average network density of 0.59, indicating close inter-item associations. Notably, items belonging to the same dimension tended to cluster together, reflecting modularity that closely mirrors the four-factor structure identified in the EFA. These results further support the structural integrity and internal consistency of the scale.

Figure 1: Network structure of climate anxiety items for the full sample (N = 959). Note. Items within the same dimension, especially worry and functional impairment, show the strongest associations

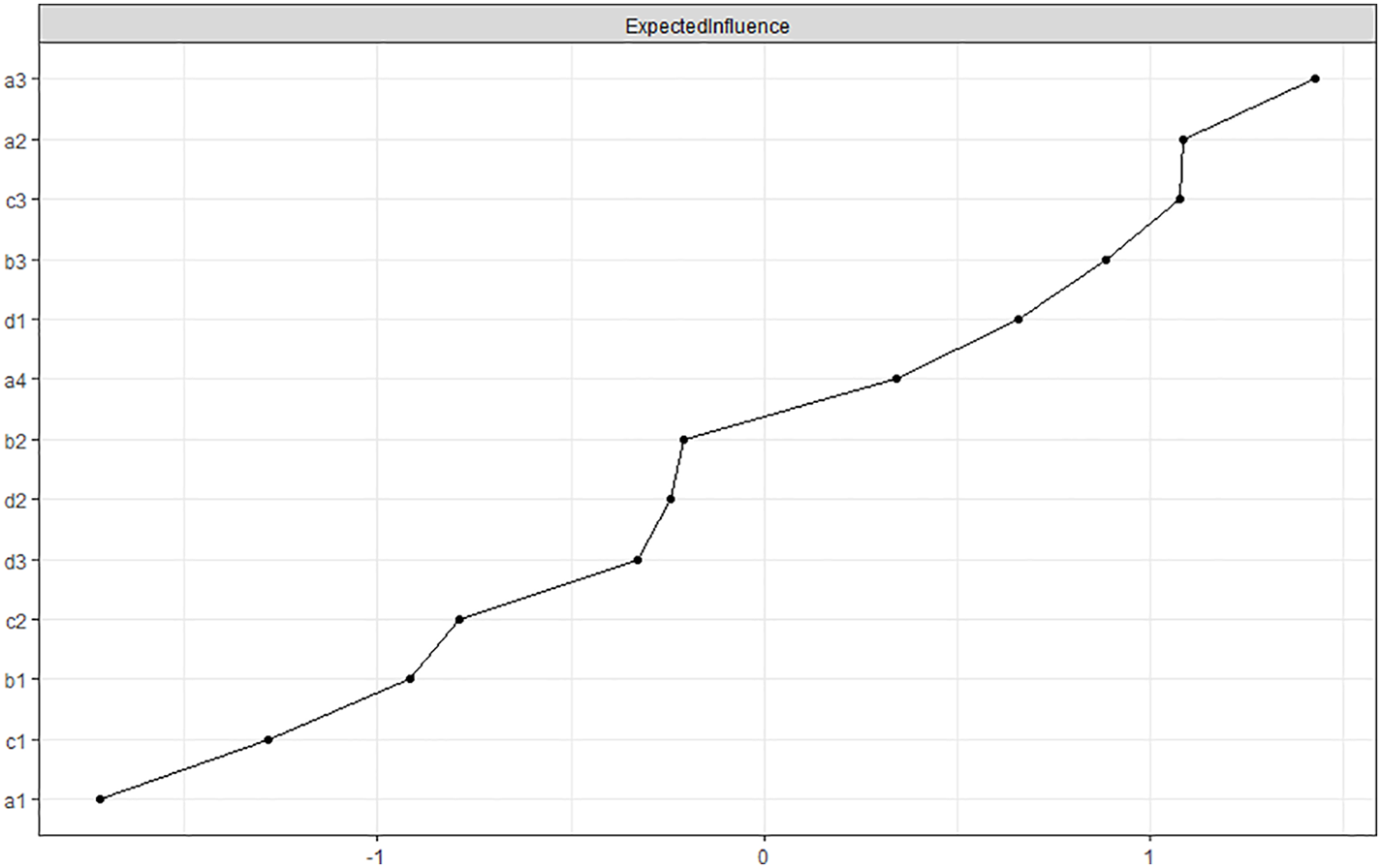

Centrality was evaluated using the Expected Influence index, which provides a more comprehensive measure of node importance compared to traditional centrality metrics (Robinaugh et al., 2016). As depicted in Figure 2, items a3 (“I feel particularly worried about climate change”), a2 (“When I think about climate change, I can’t stop or control my worrying”), and c3 (“Thinking about climate change makes it difficult for me to fully focus on my work or study”) had the highest expected influence index, indicating that these items play especially central roles in the climate anxiety network (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Expected influence index of climate anxiety items in the full sample (N = 959). Note. Items a3, a2 and c3 rank highest

CFA was conducted on Sample 3 to validate the four-factor structure of the revised scale. The fit indices indicated an excellent model fit: χ2 = 119.652, df = 59, CFI = 0.974, TLI = 0.966, RMSEA = 0.048, and SRMR = 0.034. These results provide strong evidence for the structural validity of the scale.

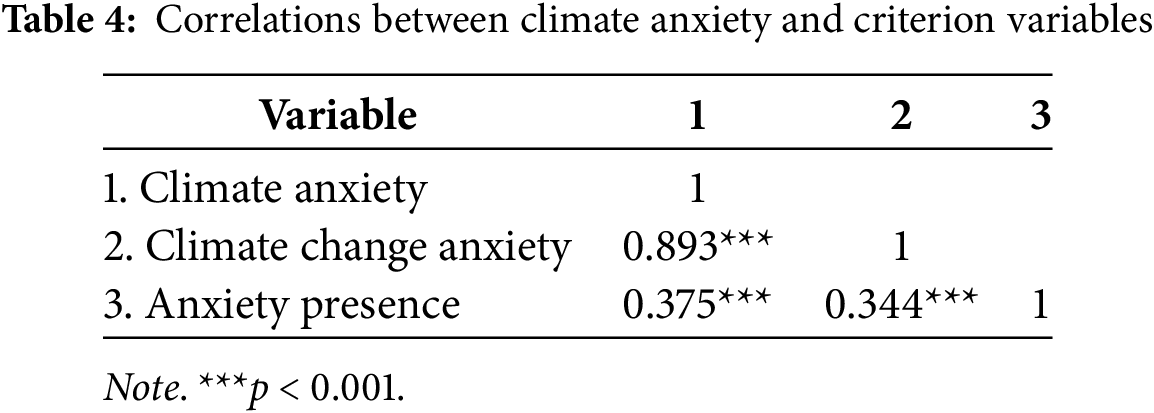

To further assess the robustness of the model, network stability was examined using a bootstrapped resampling procedure with 1000 iterations. As shown in Figure 3, the average correlation of edge weights remained consistently close to 1.0 across subsamples ranging from 90% to 30% of the total sample size, indicating that the item network structure was highly stable even under substantial data reduction. Additionally, the correlation stability coefficient for edge weights was 0.75, further confirming the excellent stability of the network. Taken together, these findings demonstrate that both the network structure and the four-factor model of the HCAS are robust and reliable across varying sample conditions.

Figure 3: Stability analysis of edge weights for climate anxiety items in the full sample (N = 959). Note. Stable edge estimates across subsamples

Convergent and discriminant validity

The composite reliability values for the four factors were 0.912, 0.820, 0.854, and 0.894, respectively, while the average variance extracted values were 0.721, 0.602, 0.661, and 0.737. All of these values exceeded commonly recommended thresholds, indicating strong internal consistency and satisfactory convergent validity for the scale.

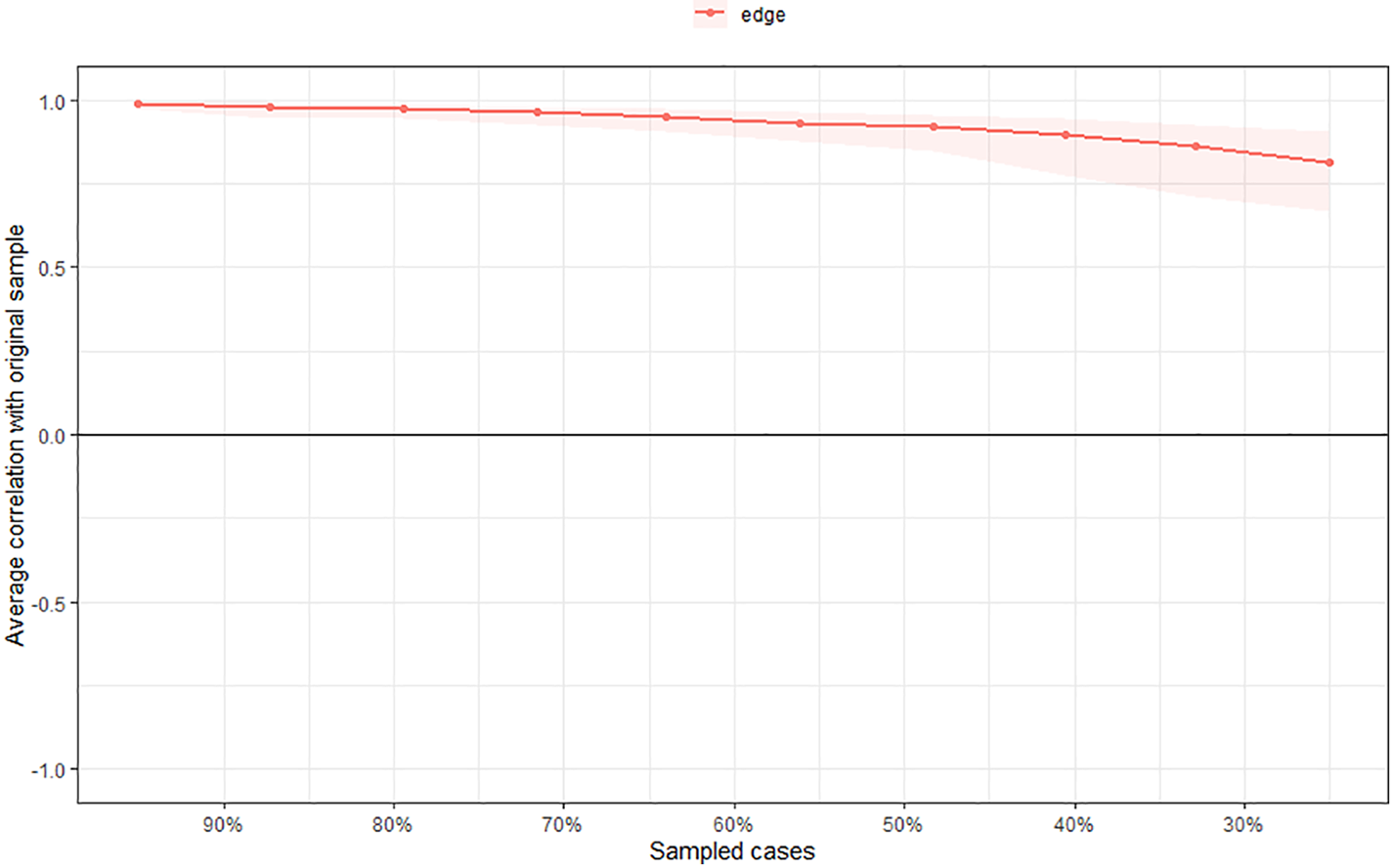

Discriminant validity was assessed by comparing a series of nested models. Model 1 specified the original correlated four-factor structure. In Model 2, the two most highly correlated latent variables from Model 1 were combined into a single factor. In Model 3, the three most highly correlated latent variables from Model 2 were combined into a single factor. Model 4 specified a unidimensional structure. As shown in Table 3, Model 1 demonstrated superior fit indices compared to the alternative models, supporting the distinctiveness of the four factors and confirming adequate discriminant validity.

Model 1: Affective Symptoms, Rumination, Behavioral Symptoms, personal impact anxiety

Model 2: Affective Symptoms + Behavioral Symptoms, Rumination, personal impact anxiety

Model 3: Affective Symptoms + Behavioral Symptoms + Rumination, personal impact anxiety

Model 4: All dimensions merged into a single factor

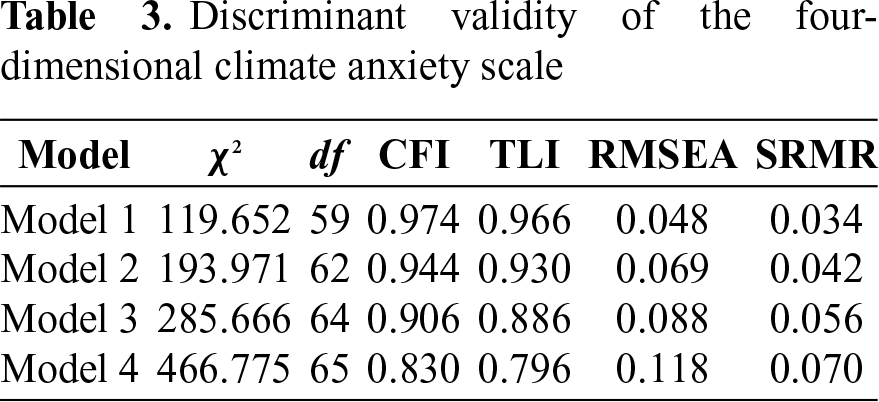

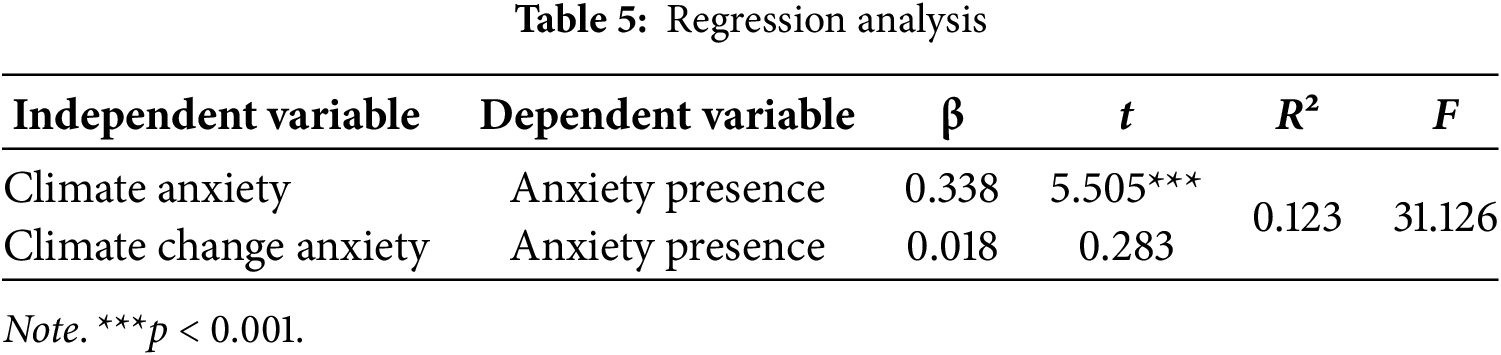

Criterion validity was evaluated by correlating the total score of the HCAS with two established measures: the CCAS and the “Presence of Anxiety” subscale of the SSAI. As shown in Table 4, the HCAS demonstrated significant positive correlations with both external criteria.

In addition, a regression analysis was performed using a between-network construct validity approach (Datu et al., 2016), with presence of anxiety as the dependent variable and the total scores of both the HCAS and CCAS as predictors. As shown in Table 5, the results indicated that only climate anxiety, as measured by the HCAS, significantly predicted state anxiety (β = 0.338, p < 0.001), whereas the CCAS did not exhibit a significant predictive effect. These findings suggest that the HCAS possesses stronger predictive validity for state anxiety compared to the CCAS.

Reliability analyses conducted on Sample 3 demonstrated strong internal consistency for the HCAS. The total scale yielded a McDonald’s ω of 0.936, and the composite reliability values for the four subscales were 0.910, 0.820, 0.854, and 0.892, respectively. Test–retest reliability was 0.716, while split-half reliability reached 0.869. Collectively, these findings confirm that the HCAS possesses excellent internal consistency and satisfactory temporal stability.

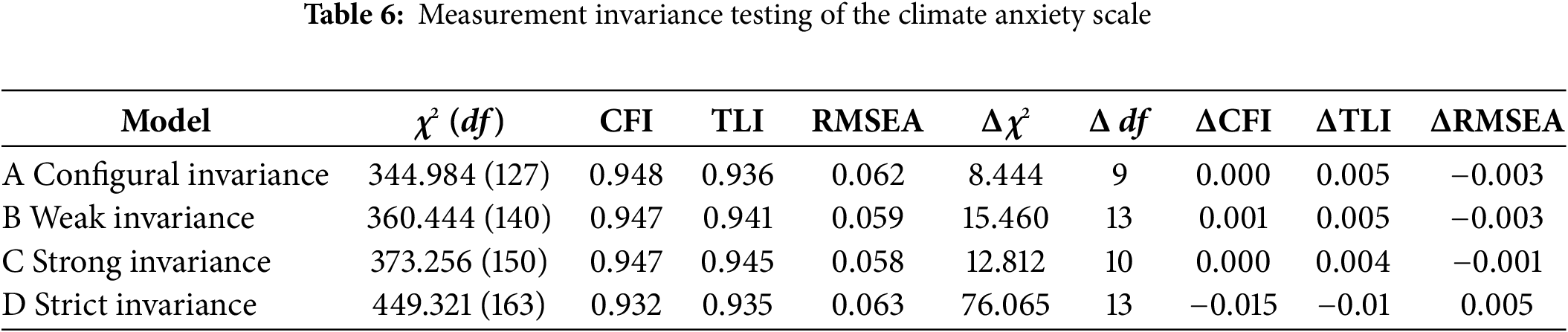

Measurement invariance across gender (male = 1, female = 2) was evaluated using Sample 3. As summarized in Table 6, all models—including configural, metric (weak), scalar (strong), and strict invariance—exhibited good fit indices (ΔCFI < 0.01, ΔTLI < 0.05, ΔRMSEA < 0.01), supporting strong invariance across gender groups.

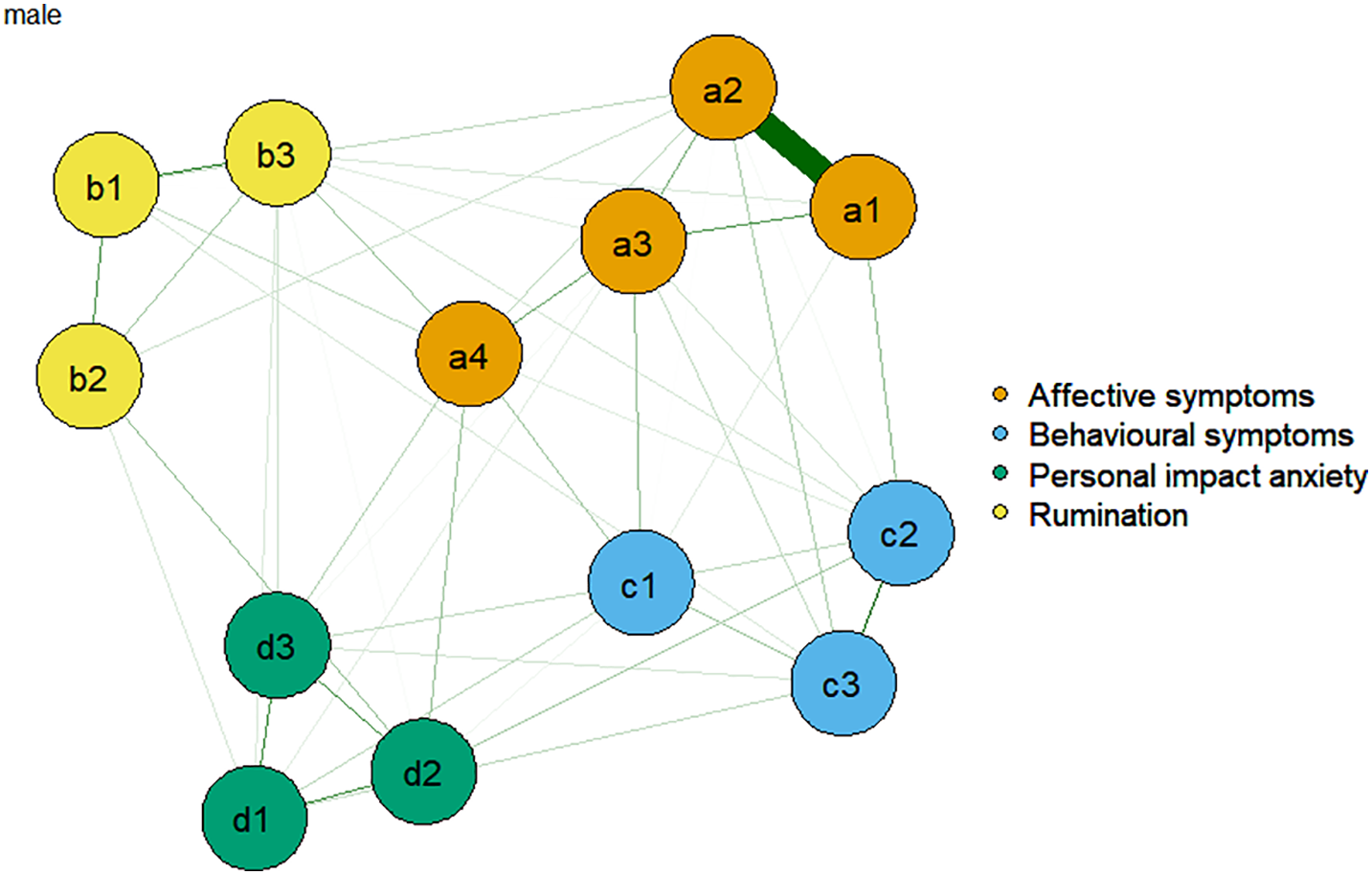

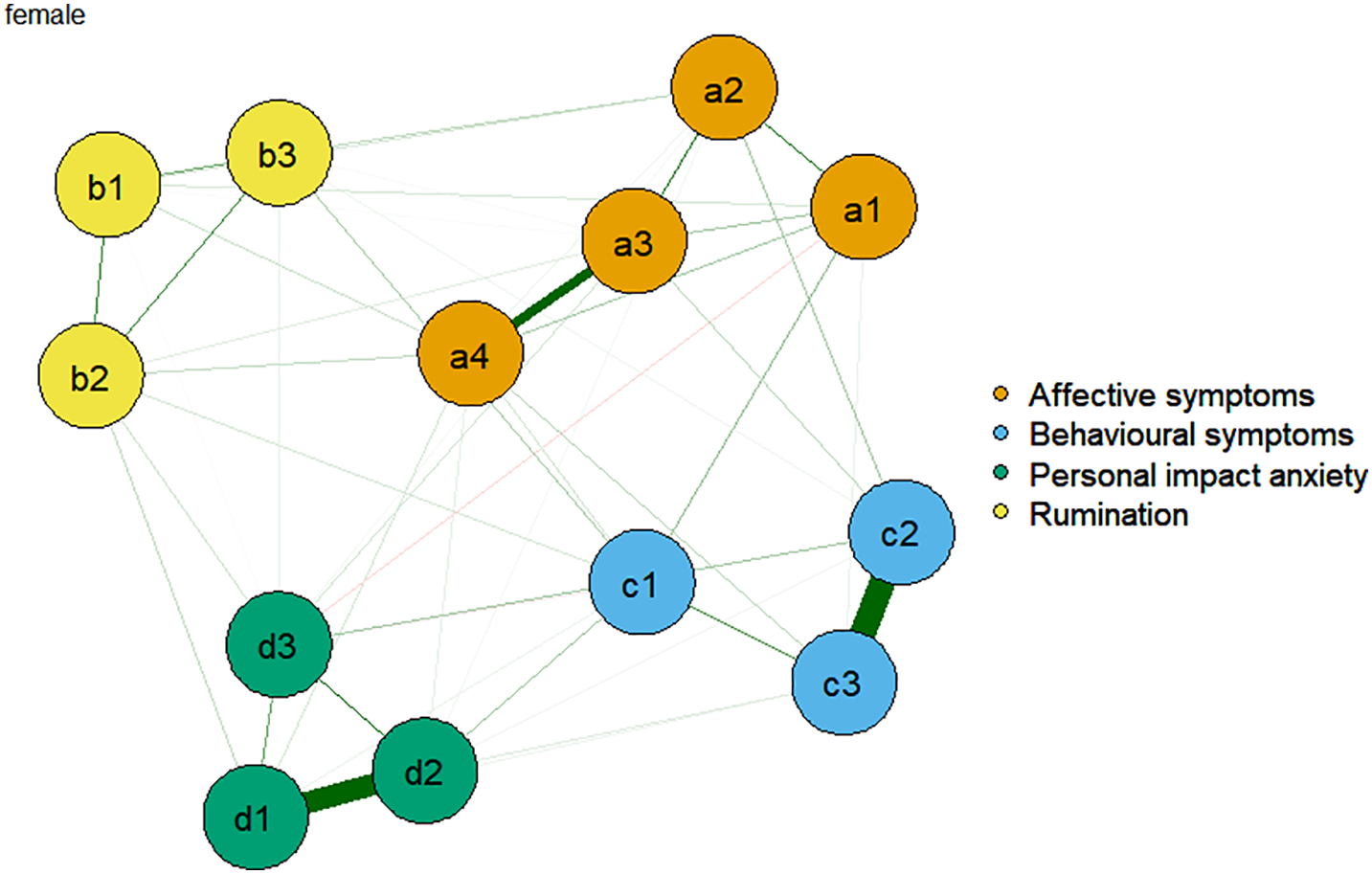

To further investigate potential gender differences, a Network Comparison Test was conducted to assess invariance in network structure between male and female participants (van Borkulo et al., 2022). As shown in Figs. 4 and 5, the results indicated no significant overall structural differences (p = 0.366). Global network strength was similar for males (6.020) and females (6.229), with a non-significant difference of 0.209. Only two edges (a3–c1 and c1–d3) differed significantly between genders, these involved affective symptoms, behavioral symptoms, and personal impact anxiety, but the effect sizes were negligible. Such minor differences may be attributable to gender-related socialization in emotional or behavioral expression but did not indicate any systematic structural bias. Taken together, the results of measurement invariance and network comparison analyses support the structural equivalence and fairness of the HCAS across gender groups, reinforcing its validity as a reliable and unbiased tool for assessing climate anxiety among university students.

Figure 4: Network structure of climate anxiety items for the male subgroup (n = 291)

Figure 5: Network structure of climate anxiety items for the female subgroup (n = 668) Note. The overall pattern is highly similar to that of the male subgroup

This study aimed to translate, adapt, and psychometrically validate the HCAS in the Chinese cultural context. The results demonstrate that the HCAS possesses robust structural validity, reliability, criterion-related validity, and measurement invariance across gender. Collectively, these findings establish the HCAS as a culturally relevant and psychometrically sound instrument for assessing climate anxiety in Chinese university students.

Structural stability and robust psychometric properties in the Chinese context

Item analysis revealed moderate to high item-total correlations, with all items displaying significant discrimination between high and low scorers. The HCAS demonstrated excellent internal consistency across the total scale and its four subscales, as well as satisfactory test–retest reliability, indicating stable temporal properties.

Both EFA and CFA confirmed a stable four-factor structure, with item-factor assignments mirroring the original instrument, thereby supporting cross-cultural construct equivalence. Indices of convergent and discriminant validity all met or exceeded recommended thresholds, further reinforcing the scale’s construct validity.

In terms of criterion validity, the HCAS total score was significantly correlated with both the CCAS and the “Presence of Anxiety” subscale evidencing good external validity. Moreover, regression analyses showed that the HCAS had stronger predictive power for general anxiety than the CCAS, suggesting that climate anxiety, as assessed by the HCAS, constitutes a related but distinct construct from generalized anxiety. This aligns with Cameron and Kagee’s (2025) assertion that climate anxiety is closely linked to, yet distinguishable from, traditional anxiety and depression.

Measurement invariance across gender supports cross-group comparisons

Multi-group confirmatory factor analysis demonstrated that the HCAS achieves configural, metric, scalar, and strict invariance across gender, indicating equivalent factor structure, loadings, and intercepts for both male and female respondents. This supports the instrument’s suitability for valid cross-group comparisons.

Additionally, network analysis revealed no significant differences in symptom interconnectivity or global network strength between genders. The convergence of evidence from both factor and network models underscores the fairness, reliability, and generalizability of the HCAS for use in diverse populations.

Network analysis provides structural validation and insights for intervention

Network analysis supplemented traditional psychometric evaluation by visually and statistically validating the HCAS’s internal structure. Items clustered tightly within dimensions, confirming the coherence of the four-factor model. Bootstrapped analyses confirmed the robustness of the network structure across different sample sizes. The absence of gender-based structural differences further highlights the scale’s stability and broad applicability. Importantly, identifying central symptoms within the network provides new directions for the development of targeted psychological interventions for climate anxiety.

Centrality metrics identified a3 (“I feel particularly worried about climate change”), a2 (“When I think about climate change, I can’t stop or control my worrying”), and c3 (“Thinking about climate change makes it difficult for me to fully focus on my work or study”) as the most influential nodes, these results suggest that interventions could focus on managing excessive worry and improving attentional control through cognitive-behavioral and mindfulness-based strategies, thereby reducing climate anxiety and supporting daily functioning.

Implications for research and practice

Compared to existing tools such as the CCAS, the HCAS demonstrates clear strengths in structural clarity, cultural adaptability, and predictive validity. Its multidimensional approach—encompassing affective symptoms, rumination, behavioral symptoms, and personal impact anxiety—offers a nuanced understanding of the cognitive-behavioral mechanisms underlying climate anxiety. Network analysis reinforced these domains and highlighted central symptoms consistent with Freeston et al.’s (2020) transdiagnostic model of intolerance of uncertainty, which emphasizes the interplay between cognitive disruption and functional impairment. The rigorous translation and back-translation process ensured semantic and conceptual equivalence, while measurement invariance testing confirmed fairness across gender groups—crucial for promoting psychometric equity in non-Western contexts.

Notably, the HCAS outperformed the CCAS in predicting general anxiety. While the HCAS significantly predicted the presence of anxiety, the CCAS did not, highlighting the unique utility of the HCAS in both research and applied settings. This scale holds promise for integration into university mental health early warning systems, for use in climate resilience education, and as a guide for targeted interventions.

Limitations and future directions

Despite the strong psychometric performance of the HCAS, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, the sample consisted primarily of university students from southeastern and central China, limiting generalizability. Future research should include more diverse populations, such as ethnic minorities, rural residents, and individuals from other regions. Second, the cross-sectional design precludes analysis of temporal dynamics or causality. Longitudinal studies are warranted to examine changes in climate anxiety around specific events (e.g., typhoons, heatwaves) and to clarify causal pathways. Third, although the HCAS is effective in identifying core symptoms, its application in intervention studies remains limited. Future research should explore its use in developing and evaluating interventions that foster resilience, adaptive coping, and proactive engagement with climate challenges. Fourth, this study did not assess participants’ direct exposure to extreme climate events, which may influence climate anxiety. Without such data, it is unclear whether individual differences reflect personal experiences with severe weather or broader climate concerns. Future research should include measures of extreme weather exposure to better understand its role in climate anxiety.

The Chinese version of the Hogg Climate Anxiety Scale was translated, adapted, and validated in this study. The HCAS demonstrated a stable four-factor structure, strong reliability, and satisfactory validity, including measurement invariance across gender. Compared with other Chinese measures, it showed superior predictive validity for general anxiety, and its structural integrity was further confirmed through network analysis. Overall, the HCAS is a reliable and culturally appropriate instrument for assessing climate anxiety in Chinese university students, supporting its use in both research and practical mental health interventions.

Acknowledgement: We are grateful to our friends and teachers for their invaluable support in the data collection and analysis of this study. We also extend our sincere appreciation to the project fund for its financial support. We acknowledge the use of ChatGPT-4 for language editing; responsibility for all content remains with the authors.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the Guangdong Education Science Planning Project (Higher Education) (2024GXJK395) and the Guangdong Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project (GD25YJY33). The APC was jointly funded by all two sources.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Study conception and design: Xi Chen, Wanru Lin; data collection: Xi Chen, Wanru Lin; analysis and interpretation of results: Xi Chen, Yuefu Liu; draft manuscript preparation: Xi Chen, Yuefu Liu; critical revision of the manuscript: Wanru Lin, Yuefu Liu. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Yuefu Liu, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Institutional Review Board Statement: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee. All participation was voluntary, with informed consent obtained from each student. This study was approved by the Academic Ethics Committee of Hanshan Normal University, China (Approval Number: 2024042901).

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

Ahmead, M., El Sharif, N., Magboul, E., Zyoud, R., & Nawajah, I. (2025). The impact of climate change experience on Palestinian university studentsmental health: A cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Climate, 7, 1580361. https://doi.org/10.3389/FCLIM.2025.1580361 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ai, X., Han, Z. Q., & Zhang, Q. (2024). Extreme weather experience and climate change risk perceptions: The roles of partisanship and climate change cause attribution. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 108(1), 104511. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.IJDRR.2024.104511 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. J. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Borsboom, D., Desemo, M. K., Rhemtulla, M., Epskamp, S., Fried, E. I., et al. (2021). Network analysis of multivariate data in psychological science. Nature Reviews Dethods Primers, 1(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/S43586-021-00060-Z [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cameron, E. C., & Kagee, A. (2025). Psychological, experiential, and behavioral predictors of climate change anxiety among South African university students. Trends in Psychology, 3(3), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1007/S43076-025-00444-0 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Clayton, S. (2020). Climate anxiety: Psychological responses to climate change. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 74(2), 102263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2020.102263. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Clayton, S., & Karazsia, B. T. (2020). Development and validation of a measure of climate change anxiety. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 69(2), 101434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2020.101434 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Datu, J. A. D., Valdez, J. P. M., & King, R. B. (2016). Perseverance counts but consistency does not! Validating the short grit scale in a collectivist setting. Current Psychology, 35(1), 121–130. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9374-2 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

DeVellis, R. F., & Thorpe, C. T. (2021). Scale development: Theory and applications. 5th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

Fang, S. H., Ding, D. Y., Huang, M. J., & Zheng, Q. L. (2024). Chinese version of the simplified psychological flexibility scale-6 (C-Psy-FlexStudy of its psychometric properties from the perspective of classical test theory and network analysis. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 32(1), 100769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2024.100769 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Freeston, M., Sermin-Reed, L., Whittaker, S., Worbey, J., & Jopling, C. (2024). Extreme weather, climate change, climate action and uncertainty distress: An exploratory study using network analysis. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 17(31), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X24000205 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Freeston, M., Tiplady, A., Mawn, L., Bottesi, G., & Thwaites, S. (2020). Towards a model of uncertainty distress in the context of Coronavirus (COVID-19). The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 13, 31. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X2000029X. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Guo, S. R., & Lyu, S. B. (2023). Reliability and validity of the climate change anxiety scale in Chinese college students. Chinese Journal of Health Psychology, 31(1), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.13342/j.cnki.cjhp [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Hickman, C., Marks, E., Pihkala, P., Clayton, S., Lewandowski, R. E., et al. (2021). Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: A global survey. The Lancet Planetary Health, 5(12), 863–873. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hogg, T. L., Stanley, S. K., & O’Brien, L. V. (2024). Validation of the hogg climate anxiety scale. Climatic Change, 177(6), 86. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10584-024-03726-1 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Mambrey, V., Wermuth, I., & Böse-O’Reilly, S. (2019). Extreme weather events and their impact on the mental health of children and adolescents. Bundesgesundheitsblatt, Gesundheitsforschung, Gesundheitsschutz, 62(5), 599–604. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00103-019-02937-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Marteau, T. M., & Bekker, H. (1992). The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the spielberger state—trait anxiety inventory (STAI). British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(3), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Matthews, T., Raymond, C., Foster, J., Baldwin, J. W., Ivanovich, C., et al. (2025). Mortality impacts of the most extreme heat events. Nature Reviews Earth & Environment, 6(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1038/S43017-024-00635-W [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Ministry of Ecology and Environment of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). Working guidance for carbon dioxide peaking and carbon neutrality in full and faithful implementation of the new development philosophy. Retrieved from: http://english.mee.gov.cn/. [Google Scholar]

Mitchell, A., Maheen, H., & Bowen, K. (2024). Mental health impacts from repeated climate disasters: An australian longitudinal analysis. The Lancet Regional Health–Western Pacific, 47, 101087. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.LANWPC.2024.101087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747–757. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., & Vagg, L. R. (1983). Manual for the state-traitanxiety inventory (Form y) (Self-evaluation questionnaire). Palo Alto, CA, USA: Consulting Psych Ologists Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

Tian, Y. Y., Yang, D., Cody, D., & Cao, M. L. (2018). Validity and reliability of the Brief State Anxiety Scale in college students. Chinese Mental Health Journal, 32(10), 886–888. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

van Borkulo, C. D., van Bork, R., Boschloo, L., Kossakowski, J. J., Tio, P., et al. (2022). Comparing network structures on three aspects: A permutation test. Psychological Methods, 28(6), 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

van Valkengoed, A. M., Steg, L., & de Jonge, P., (2023). Climate anxiety: A research agenda inspired by emotion research. Emotion Review, 15(4), 258–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/17540739231193752 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Wang, J. N., Wang, Y. J., Zhang, Y., Zhang, X., Yang, C. X., et al. (2012). Investigation on college students’ cognition of climate change. Journal of Environment and Health, 29(7), 651–653. https://doi.org/10.16241/j.cnki.1001-5914.2012.07.014 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Yang, L., Wang, W. J., Qin, Z., & Gu, Y. X. (2022). Climate cognition, low-carbon behaviors, and their influencing factors among Chinese university students: Based on random forest model analysis. Culture and Communication, 11(2), 6–15. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools