Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Problematic internet use and substance use disorder among men: A scoping review

Psychology Department, Rhodes University, Makhanda, 6140, South Africa

* Corresponding Author: Liezille Jacobs. Email:

Journal of Psychology in Africa 2025, 35(6), 761-769. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpa.2025.065787

Received 26 December 2024; Accepted 21 March 2025; Issue published 30 December 2025

Abstract

This scoping review aimed to synthesise literature on problematic internet use and substance use disorder, including how they affect men, given that prior research has predominantly focused on women. The search included Web of Science, Psych Info, Science Direct, and Scopus spanning over the period 2014–2023. Studies were included for the review if they focused on Problematic Internet Use (PIU) and Substance Use Disorder (SUD) among men, were peer-reviewed, and were written in English. Opinions, discussions, and theoretical papers were excluded. Sixteen studies were included in this review. Data were synthesised through thematic analysis. Emergent themes included gendered addiction patterns by which men were at higher risk for pathological gambling, gaming addiction, sex/pornography addiction, alcohol dependence, smoking, cocaine and cannabis. Moreover, substance use and PIU behavioral addictions in men were moderated by impulsivity, personality traits and stress for worse addictions. These findings provide leads for further research on gendered problematic internet use and substance use disorder, including the neurobiological substrates involved.Keywords

Problematic Internet Use (PIU) and Substance Use Disorder (SUD) interact in complex ways that influence the current mental health landscape. PIU refers to use of the internet that creates psychological, social, school, and/or work difficulties in a person’s life (Beard & Wolf, 2001; Kożybka et al., 2023), and with a seeming lack of control in daily life (Spada, 2014). Substance use disorder is associated with a range of symptoms, including cravings, tolerance, withdrawal, and an inability to control or cut down on substance use which can lead to clinically significant impairment or distress occurring within a 12-month period . Problematic Internet Use an SUD may be gendered, and there is need to trend the findings from recent studies to inform future studies.

Problematic internet use (PIU) and substance use disorder (SUD)

Problematic internet use is often associated with various risk behaviours, such as substance use, and a host of other related negative consequences. It is estimated that alcohol misuse contributes to over 3 million deaths each year, making it a leading risk factor for premature mortality, especially among individuals between the ages of 20 and 39 (World Health Organization, 2022). In 2019, alcohol use accounted for 2.07 million deaths of males and 374,000 deaths of females globally . An estimate of 129–190 million people globally use cannabis, followed by amphetamine type stimulants, cocaine, and opioids (World Health Organization, 2022). In their lifetime, 13.3% of South Africans take at least one substance (Kaswa & De Villiers, 2020). While there is a dearth of demographic data on substance use in South Africa, it is estimated that 10.3% of adults (15 years and older) drink alcohol excessively (16.5% of males and 4.6% of women), and 8.6% (13.3% of men and 4.1% of women) use illegal drugs nationally (Pengpid et al., 2021). These statistics suggest that there is a gender disparity in alcohol misuse and substance use disorders in South Africa, with higher rates observed among males compared to females. However, it is important to note that these figures are estimates, and more research is needed to fully understand the extent of the problem and the underlying factors contributing to these gender differences.

Men and women alike are struggling with both PIU and SUD. The criteria that constitutes PIU and SUD are similar, with one main difference being that PIU is not reliant on an intoxicant in the way a SUD is. Both phenomena share a common maladaptive pattern response, which ultimately leads to impairment in various different areas of an individual’s life. A cross-sectional study by Sayeed et al. (2021) found that from a sample of 404 internet users over the age of 18 years, problematic internet use was significantly higher in males than female respondents. Notably, Su et al. (2020) found that men are more likely to present with IGD and women with overuse of social networking sites, such as Facebook and Instagram. Differences exist within the literature, whereby some studies agree that PIU is more prevalent among women, although some studies contradict this notion, showing that men are more vulnerable and show higher levels of problematic internet use (Baloğlu et al., 2020). Furthermore, Su et al. (2020) stated that males have often reported experiencing higher levels of internet addiction in comparison to women, but this may differ in terms of the specific types of internet use. Additionally, a study by Laconi et al. (2017) found from a sample of 5593 internet users (2129 men and 3464 women), with individuals aged between 18 and 87 years old, that problematic internet use was more prevalent among women, with notable differences in the type of internet use. These findings suggest that while men exhibit higher levels of overall internet addiction, women engage in different types of internet use that contribute to their vulnerability to problematic internet use. This highlights the importance of considering gender differences when studying and addressing internet addiction. Moreover, this outcome emphasises that contrary results do exist (Baloğlu et al., 2020; Su et al., 2020). Thus, this study aimed to explore problematic internet use and substance use disorder among men, a high risk and less well studied population.

This scoping review aimed to synthesise literature on PIU and SUD in adult men. The following question guided the scoping review: What does existing literature reveal about problematic internet use and substance use disorder among adult men?

The present study was guided by the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) of evidence synthesis as the proposed methodological approach of this scoping review, which is based on earlier work by Arksey and O’Malley (2005) and Levac et al. (2010). Scoping reviews have great utility when it comes to synthesising research evidence due to their ability to map out the emerging literature on a particular subject in terms of its volume, features, and nature (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). A scoping review is typically utilised to synthesize the emerging evidence on a topic for trends (1) to identify gaps within a body of research; and also as a precursor to a systematic review, where a preliminary mapping might be performed to ascertain whether a full systematic review is feasible or relevant. A scoping review is more appropriate for the present study as compared to a systematic review.

We searched the Web of Science, Psych Info, Science Direct and Scopus. To be included in this review, papers had to focus on the topic of PIU an SUD among men and fulfil the criteria listed in Table 1.

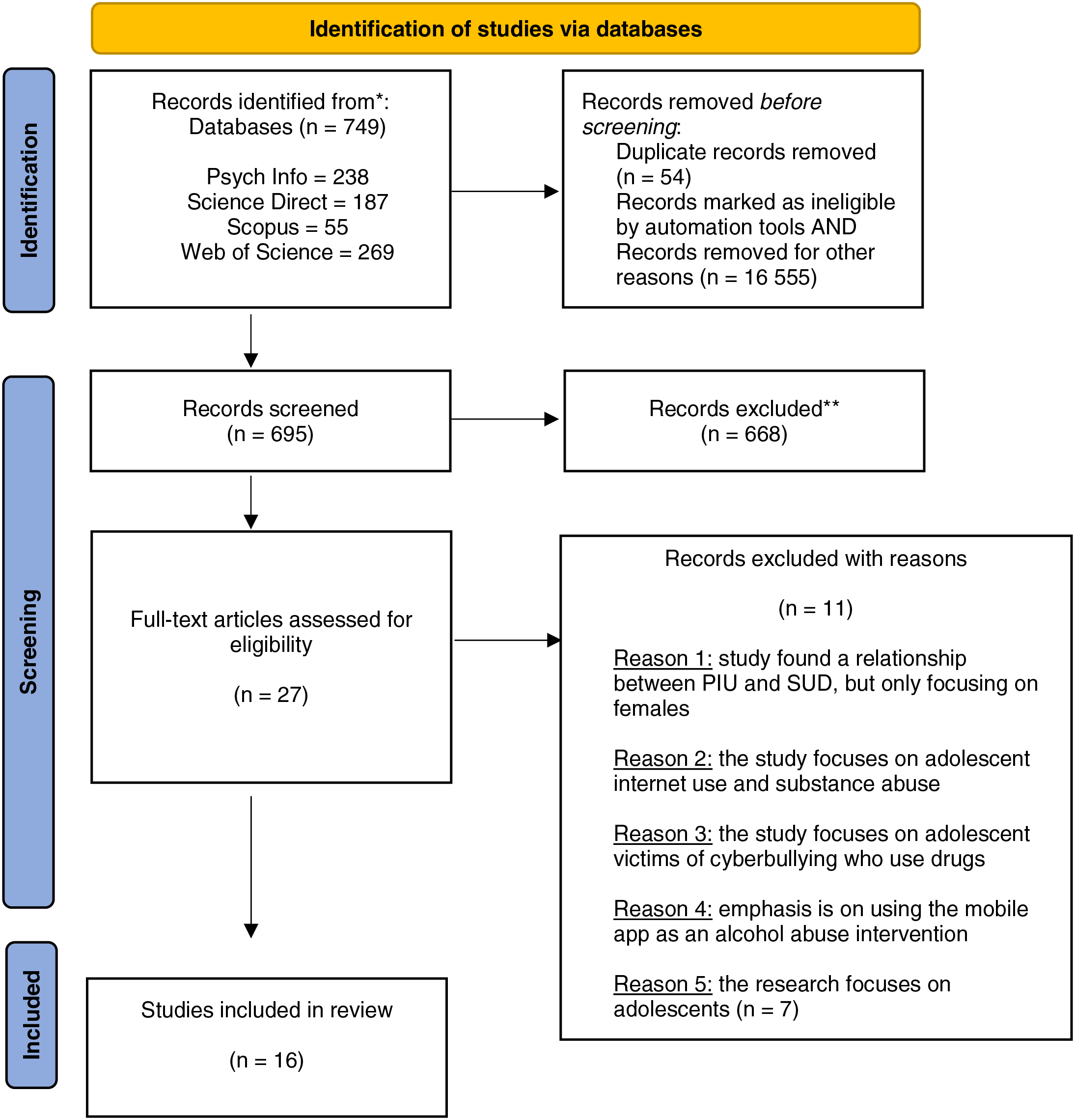

The study selection followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) which is largely based on a PRISMA statement and checklist, the JBI methodological guidance, and other approaches for undertaking scoping reviews. The process of reviewing the literature guided by the inclusion criteria as outlined above was achieved through three screening phases: (1) title screening, (2) abstract screening, and (3) full text screening. The selection of 16 articles were included after the elimination process (See Figure 1 below).

Figure 1: Problematic internet use and substance use disorder among men: a scoping review

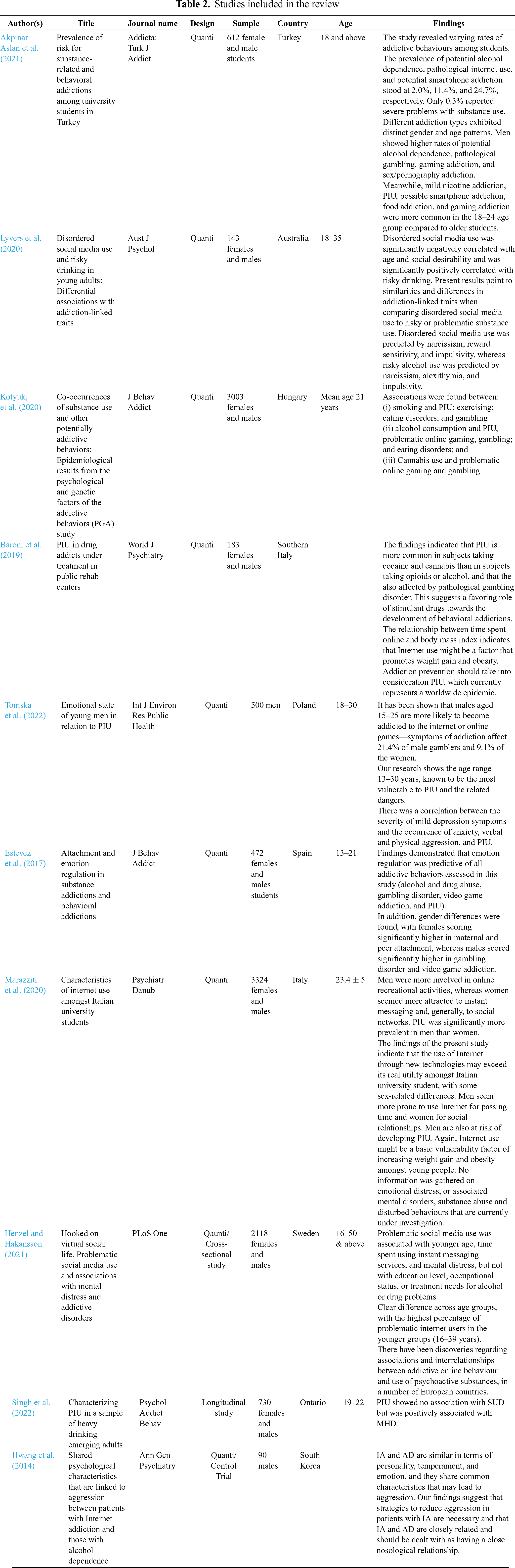

A draft charting table was created as part of the review process to capture key information about the study, such as the various characteristics of the studies included in the study and their relevance to the research question. The following types of information was extracted: author(s), year of publication, source origin, country of origin, aims, purpose, study population and sample size (if applicable), methodology, intervention type and comparator (if applicable), concept, duration of the intervention (if applicable), how outcomes are measured, and key findings that relate to the review question (Khalil et al., 2016). Table 2 below presents part of the results of the studies included in the final review.

A thematic analysis was thus conducted guided by Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six steps: namely, familiarisation of the data, generating codes, searching for themes, reviewing the themes, defining, and naming them, and then reproducing the report. Two themes resulted: gendered addiction patterns and substance behavioural addictions (see Table 3). For credibility and trustworthiness of the themes, a second reviewer was consulted, and disagreements regarding the themes were catalogued.

Geographical distribution of studies

Most of the included study samples were from Europe, the United States of America and Australia. As indicated in Table 4, studies from Australia contributed 5% to the entire sample. Most studies sampled from European countries like Poland, Hungary, Sweden, Italy, Spain and Germany. China and South Korea were broadly sampled by one study. Some studies included samples from two or more countries such as Canada and North America. The remainder of the studies were from United Kingdom. Note that the country total does not concur with the total articles as some articles sampled from more than one country.

Generally, studies concerned with PIU and SUD mainly utilise quantitative methods (95%) and one qualitative article. The included samples varied in size from 6419 participants of which the mean sample size was 2061, with 612 participants being the most frequent sample size. Participant samples consisted of 52% females and 48% males. The most common age group sampled was 21 to 45.

Concerns about PIU prevalence have grown in recent years as more and more studies have been conducted to clarify the condition’s various symptoms and contributing variables. In all the demographic groups studied, adult men have emerged as a notable group that exhibits problematic internet usage patterns and vulnerability to PIU. In addition to determining the extent of the problem, knowing the prevalence rates of PIU among adult men is important for developing focused interventions and preventive measures that specifically address the challenges that they experience. Thus, it has been found that men display higher levels of PIU than females (Akpinar Aslan et al., 2021; Estevez et al., 2017; Hwang et al., 2014; Marazziti et al., 2020; Tomska et al., 2022). Similarly, a study conducted by Kożybka et al. (2023) found significantly higher levels of PIU in males than females. Sayeed et al., (2021) reported significantly higher PIU in males than female respondents (see also Zewde et al., 2022). Higher rates of PIU in men could be attributed to the competitive nature of certain online gaming environments (Su et al., 2020), as men are more likely to present with IGD and women with social networking sites, such as Facebook and Instagram.

Substance use disorders affect men and women differently, although the prevalence has been reported to be higher in men (Compton et al., 2007; Da Fonseca et al., 2021; McHugh et al., 2018). Research has shown that men are more likely to engage in heavy and binge drinking compared to women, which contributes to the higher prevalence of substance use disorders in men (Grant et al., 2015; Keyes et al., 2011). Despite the growing number of studies focused on the sex-related differences in drug addiction, few studies have investigated the potential differences in the behaviour of men and women when it comes to non-substance related addictions (Fattore et al., 2014). Regarding substance use, women who are at risk for substance abuse are more prone to using substances at a faster rate than men, leading to the development of an addiction.. This is because of the circulating ovarian hormones in females, where short-term exposure to estradiol can contribute to the faster acquisition of substances by women. Furthermore, according to Fattore et al. (2014), women who attempt to stop using substances such as cocaine or amphetamine experience withdrawal symptoms more unpleasant than men, as with smoking. However, men experience more unpleasant symptoms when attempting to quit alcohol. Males are more likely than females to engage in risky behaviours such as experimenting with drugs, and if susceptible to substance abuse, they are drawn into a spiral that leads to addiction (Becker et al., 2012). Although the structures and processes involved in the reinforcement of positive and negative stimuli are similar in both males and females, the sex differences in how these neural systems are activated and connected are believed to underlie the development of addiction (Becker et al., 2012). Thus, it is evident that the neurobiological make-up of men and women may contribute to these gender differences in addiction. However, an in-depth exploration of the different mechanisms and neural pathways involved is beyond the scope of this study.

Substance use and PIU behavioural addictions

Men who engage in substance use are more likely to have PIU, and vice versa. Multiple studies by authors such as Baroni et al. (2019), Henzel and Hakansson (2021), Kotyuk et al. (2020), and Lyvers et al. (2020) share consistent results regarding the positive association between PIU and SUD in men. Numerous studies have investigated the connection between PIU and substance usage, such as incusing use of cocaine, alcohol, cannabis, and smoking (Henzel and Hakansson, 2021; Kotyuk et al., 2020; Lyvers et al., 2020; Singh et al., 2022). Substance abuse and PIU also have common underlying causes (Sinclair et al., 2016). Inefficient self-control appears to be a common factor leading to maladaptive behaviour and an inability to resist both behavioural and substance-related addictions (Kozak et al., 2019). There is a wide range of neurobiological evidence that can be used to inform the debate about the development of behavioural addictions. These include structural brain imaging, functional brain imaging, and cognitive assessment. On the structural level of the brain, it has been revealed that there is a link between internet gaming and reduced grey matter density in various regions of the brain (Chamberlain et al., 2016). In some cases, the development of behavioural addictions can be triggered by dopaminergic agents used for treating other conditions, such as Parkinson’s Disease and restless leg syndrome (Chamberlain et al., 2016). This is consistent with Chamberlain et al. (2016) and Sinclair et al. (2016) who reported that available psychobiological data on chemical and behavioural addictions comes from studies on the molecular biology and neural circuitry of substance use disorders. It begs the question of whether participating in one kind of addictive behaviour makes one more vulnerable to the other. Considering that individuals can develop multiple addictive behaviours, it is important to understand the underlying factors that contribute to the development of these behaviours.

Implications for Future Research

Further research is needed to fully understand the interplay between PIU and substance abuse disorders. For instance, personality types also contribute to the differences in online behaviours (Kosinski et al., 2014). Introverted individuals may prefer to engage in more passive activities such as reading or observing, while extroverted individuals may be more likely to actively participate in online discussions and seek social validation. Moreover, internet use is associated with loneliness and can help escape and relieve stress for a short period of time to cope with the psychological distress of the pandemic (Singh et al., 2021). Further, age-related PIU and SUD have been reported (Akpinar Aslan et al., 2021; Henzel & Hakansson, 2021; Singh et al., 2022; Tomska et al., 2022). For instance, Henzel and Hakansson (2021) highlights a higher percentage of problem users are in the younger demographic, particularly those aged 16–39 years. Giotakos et al. (2016) reported higher risk for PIU and SUD in middle adulthood in which the overuse of the internet was associated with the development of an addiction to online gambling, followed by substance use in general, and particularly the use of illicit drugs such as heroin and cocaine. This age range captures a significant portion of the population and emphasises the need for targeted interventions for individuals in their late adolescence through early adulthood.

Limitations of the study and future directions

One of the main criticisms in developing research on problematic internet use or internet addiction is the lack of consensus regarding the diagnosis and conceptualisation of such disorders. Thus, despite the widespread attention paid to the issue, the development of a comprehensive standard of care for individuals suffering from internet addiction has been challenging due to the field’s cultural diversity, namely with regard to the variance in the terminology used in academic literature (e.g., internet addiction, PIU, pathological internet use), and secondly, the challenge that arises with different inventories being used in their assessment, making it difficult for results to be generalised to other contexts. A clear understanding and conceptualisation of this behavioural addiction is vital, including the development and utilisation of appropriate and validated diagnostic and screening tools to measure its presence and, in turn, address it as an emerging mental health disorder. Using validated tools will allow for comparison with other studies. Conducting this scoping review highlighted that there was a paucity of studies employing research designs beyond quantitative methodologies, indicating a clear gap within the body of literature when it comes to PIU. Such a methodological gap in the literature implies a shortage of in-depth exploration of individuals’ perceptions, experiences, and feelings in relation to the topic of PIU. Gearing towards the inclusion of more qualitative data would only be possible once a consensus has been reached amongst researchers regarding the classification, aetiology, and progression of PIU. Additionally, it was rare to find literature specifically focusing on men. Within the literature, men were always studied against women, particularly when looking at the gender differences in the development of PIU. Researchers are thus advised to study men and women in their own right, given that they present differently in the kinds of internet related activities they engage in. Focus should therefore be given to the assessment of PIU by distinguishing the two different forms from each other, namely the generalised and specific forms of PIU.

It is evident that both PIU and substance abuse disorders are gendered. The first theme highlighted that although there are contrary findings on whether males or females have the highest prevalence of PIU, there is substantial evidence that also suggests that men may have the highest prevalence. However, the prevalence rates appear to be dependent on the types of activities men and women engage in when online. The second theme highlighted the interconnected nature of behavioural addictions, particularly internet addiction, with substance-related dependencies, implying the presence of common underlying risk factors, further confirming the idea that addictions have psychological causes. In addition to the interconnectedness of behavioural and substance related addictions, multiple studies shared consistent results regarding the positive association between PIU and SUD. It made sense to examine both these phenomena simultaneously because of their interrelatedness and the mere fact that they share similar psychosocial characteristics. In conclusion, there is a bidirectional relationship between PIU and SUD, which highlights the complex interplay between the two phenomena, necessitatinga need for interventions that can address both at the same time.

Acknowledgement: The authors would like to acknowledge Rhodes University for the completion of this research.

Funding Statement: The authors were funded by Rhodes University to conduct this research.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: Liezille Jacobs, Miché Adolph; data collection: Liezille Jacobs, Miche Adolph; analysis and interpretation of results: Liezille Jacobs, Miche Adolph; draft manuscript preparation: Liezille Jacobs, Miche Adolph. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data openly available in a public repository available at (www.ru.ac.za) (accessed on 20 March 2025).

Ethics Approval: Since this is a review study, it did not acquire ethical review.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study

References

Akpinar Aslan, E., Batmaz, S., Celikbas, Z., Kilincel, O., Hizli Sayar, G. et al. (2021). Prevalence of risk for substance-related and behavioral addictions among university students in Turkey. ADDICTA: The Turkish Journal on Addictions, 8(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.5152/addicta.2021.21023 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory & Practice, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Baloğlu, M., Şahin, R., & Arpaci, I. (2020). A review of recent research in PIU: Gender and cultural differences. Current Opinion in Psychology, 36, 124–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.05.008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Baroni, S., Marazziti, D., Mucci, F., Diadema, E., & Dell’Osso, L. (2019). Problematic Internet use in drug addicts under treatment in public rehab centers. World Journal of Psychiatry, 9(3), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v9.i3.55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Beard, K. W., & Wolf, E. M. (2001). Modification in the proposed diagnostic criteria for Internet addiction. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 4(3), 377–383. [Google Scholar]

Becker, J. B., Perry, A. N., & Westenbroek, C. (2012). Sex differences in the neural mechanisms mediating addiction: A new synthesis and hypothesis. Biology of Sex Differences, 3, 1–35. [Google Scholar]

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Chamberlain, S. R., Lochner, C., Stein, D. J., Goudriaan, A. E., van Holst, R. J. et al. (2016). Behavioural addiction—A rising tide? European Neuropsychopharmacology, 26(5), 841–855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Compton, W. M., Thomas, Y. F., Stinson, F. S., & Grant, B. F. (2007). Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV drug abuse and dependence in the United States: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(5), 566–576. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.64.5.566. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Da Fonseca, M. H., Kovaleski, F., Picinin, C. T., Pedroso, B., & Rubbo, P. (2021). E-health practices and technologies: a systematic review from 2014 to 2019. Healthcare, 9(9), 1192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Estevez, A., Jauregui, P., Sanchez-Marcos, I., Lopez-Gonzalez, H., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). Attachment and emotion regulation in substance addictions and behavioral addictions. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 534–544. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.6.2017.086. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Fattore, L., Melis, M., Fadda, P., & Fratta, W. (2014). Sex differences in addictive disorders. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 35(3), 272–284. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

Giotakos, O., Tsouvelas, G., Spourdalaki, E., Janikian, M., Tsitsika, A. et al. (2016). Internet gambling in relation to Internet addiction, substance use, online sexual engagement and suicidality in a Greek sample. International Gambling Studies, 17(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/14459795.2016.1251605 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Grant, B. F., Goldstein, R. B., Saha, T. D., Chou, S. P., Jung, J. et al. (2015). Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and related conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry, 72(8), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.0584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Henzel, V., & Hakansson, A. (2021). Hooked on virtual social life. Problematic social media use and associations with mental distress and addictive disorders. PLoS One, 16(4), e0248406. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Hwang, J. Y., Choi, J. S., Gwak, A. R., Jung, D., Choi, S. W. et al. (2014). Shared psychological characteristics that are linked to aggression between patients with Internet addiction and those with alcohol dependence. Annals of General Psychiatry, 13(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1744-859X-13-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kaswa, R., & De Villiers, M. (2020). Prevalence of substance use amongst people living with human immunodeficiency virus who attend primary healthcare services in Mthatha, South Africa. South African Family Practice, 62(2), 5042. https://doi.org/10.4102/safp.v62i1.5042. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Keyes, K. M., Hatzenbuehler, M. L., & Hasin, D. S. (2011). Stressful life experiences, alcohol consumption, and alcohol use disorders: The epidemiologic evidence for four main types of stressors. Psychopharmacology, 218(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-011-2236-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Khalil, H., Peters, M., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Soares, C. B. et al. (2016). An evidence-based approach to scoping reviews. Worldviews on Evidence-Based Nursing, 13(2), 118–123. https://doi.org/10.1111/wvn.12144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kosinski, M., Bachrach, Y., Kohli, P., Stillwell, D., & Graepel, T. (2014). Manifestations of user personality in website choice and behaviour on online social networks. Machine Learning, 95(3), 357–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10994-013-5415-y [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Kotyuk, E., Magi, A., Eisinger, A., Kiraly, O., Vereczkei, A. et al. (2020). Co-occurrences of substance use and other potentially addictive behaviors: Epidemiological results from the psychological and genetic factors of the addictive behaviors (PGA) study. Journal of Behavioral Addiction, 9(2), 272–288. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kozak, K., Lucatch, A. M., Lowe, D. J. E., Balodis, I. M., MacKillop, J. et al. (2019). The neurobiology of impulsivity and substance use disorders: Implications for treatment. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1451(1), 71–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.13977. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Kożybka, M., Radlińska, I., Kolwitz, M., & Karakiewicz, B. (2023). PIU among polish students: prevalence, relationship to sociodemographic data and internet usage patterns. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(3), 2434. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20032434. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Laconi, S., Vigouroux, M., Lafuente, C., & Chabrol, H. (2017). Problematic internet use, psychopathology, personality, defense and coping. Computers in Human Behavior, 73, 47–54. [Google Scholar]

Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Lyvers, M., Narayanan, S. S., & Thorberg, F. A. (2020). Disordered social media use and risky drinking in young adults: Differential associations with addiction-linked traits. Australian Journal of Psychology, 71(3), 223–231. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12236 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Marazziti, D., Baroni, S., Mucci, F., Piccinni, A., Ghilardi, A. et al. (2020). Characteristics of internet use amongst Italian university students. Psychiatria Danubina, 32(3–4), 411–419. https://doi.org/10.24869/psyd.2020.411. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

McHugh, R. K., Votaw, V. R., Sugarman, D. E., & Greenfield, S. F. (2018). Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 66(1), 12–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2017.10.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Pengpid, S., Peltzer, K., & Ramlagan, S. (2021). Prevalence and correlates of hazardous, harmful or dependent alcohol use and drug use amongst persons 15 years and older in South Africa: Results of a national survey in 2017. African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine, 13, e1–e8. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v13i1.2847 Penguin Books. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Sayeed, A., Rahman, M., Hassan, M., Christopher, E., Kundu, S. et al. (2021). Problematic internet use associated with depression, health, and internet-use behaviors among university students of Bangladesh: A cross-sectional study. Children and Youth Services Review, 120(10), 105771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.105771 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Sinclair, H., Lochner, C., & Stein, D. J. (2016). Behavioural addiction: A useful construct? Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 3(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-016-0067-4 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Singh, A., Levitt, E., Soreni, N., Van Ameringen, M., & MacKillop, J. (2022). Characterizing problematic internet use in a sample of heavy drinking emerging adults. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 36(4), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Singh, S., Mani Pandey, N., Datta, M., & Batra, S. (2021). Stress, internet use, substance use and coping among adolescents, young-adults and middle-age adults amid the ‘new normal’ pandemic era. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 12(14), 100885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100885. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Spada, M. M. (2014). An overview of PIU. Addictive Behaviors, 39(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Su, W., Han, X., Yu, H., Wu, Y., & Potenza, M. (2020). Do men become addicted to internet gaming and women to social media? A meta-analysis examining gender-related differences in specific internet addiction. Computers in Human Behavior, 113(1), 106480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106480 [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Tomska, N., Ryl, A., Turon-Skrzypinska, A., Szylinska, A., Marcinkowska, J. et al. (2022). Emotional state of young men in relation to problematic internet use. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(19), 12153. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191912153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

World Health Organization (2022). World health statistics 2022: Monitoring health for the SDGs. In: Sustainable Development Goals. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO. [Google Scholar]

Zewde, E. A., Tolossa, T., Tiruneh, S. A., Azanaw, M. M., Yitbarek, G. Y. et al. (2022). Internet addiction and its associated factors among African high school and university students: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 847274. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.847274. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools