Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Removal of Iron from Leached Geological Samples Using Polypropylene Waste Amidoxime-Based Radiation Grafted Adsorbent

1 Department of Chemical Engineering, Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (PIEAS), Islamabad, Pakistan

2 Department of Chemistry, Pakistan Institute of Engineering and Applied Sciences (PIEAS), Islamabad, Pakistan

* Corresponding Author: Asif Raza. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(1), 141-150. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2024.057423

Received 17 August 2024; Accepted 21 November 2024; Issue published 27 March 2025

Abstract

Geological samples often contain significant amounts of iron, which, although not typically the target element, can substantially interfere with the analysis of other elements of interest. To mitigate these interferences, amidoxime-based radiation grafted adsorbents have been identified as effective for iron removal. In this study, an amidoxime-functionalized, radiation-grafted adsorbent synthesized from polypropylene waste (PPw-g-AO-10) was employed to remove iron from leached geological samples. The adsorption process was systematically optimized by investigating the effects of pH, contact time, adsorbent dosage, and initial ferric ion concentration. Under optimal conditions—pH 1.4, a contact time of 90 min, and an initial ferric ion concentration of 4500 mg/L—the adsorbent exhibited a maximum iron adsorption capacity of 269.02 mg/g. After optimizing the critical adsorption parameters, the adsorbent was applied to the leached geological samples, achieving a 91% removal of the iron content. The adsorbent was regenerated through two consecutive cycles using 0.2 N HNO3, achieving a regeneration efficiency of 65%. These findings confirm the efficacy of the synthesized PPw-g-AO-10 as a cost-effective and eco-friendly adsorbent for successfully removing iron from leached geological matrices while maintaining a reasonable degree of reusability.Keywords

Geological samples often contain significant concentrations of iron in addition to valuable metals. During the extraction and analysis of these target metals, iron frequently causes contamination and interferences with the analytical process [1,2]. Various conventional and non-conventional methods, such as precipitation, solvent extraction, ion exchange, and magnetic separation, have been employed to remove iron impurities from geological matrices [3–6]. However, these methods typically lack efficiency in selectively removing iron from soil or leached geological samples. Furthermore, certain techniques, such as solvent extraction using methyl isobutyl ketone (MIBK) and primary amines, pose significant environmental and health risks [7]. To overcome these challenges, researchers are exploring using polymeric chelating resins specifically designed to adsorb metals from samples with complex matrices [8].

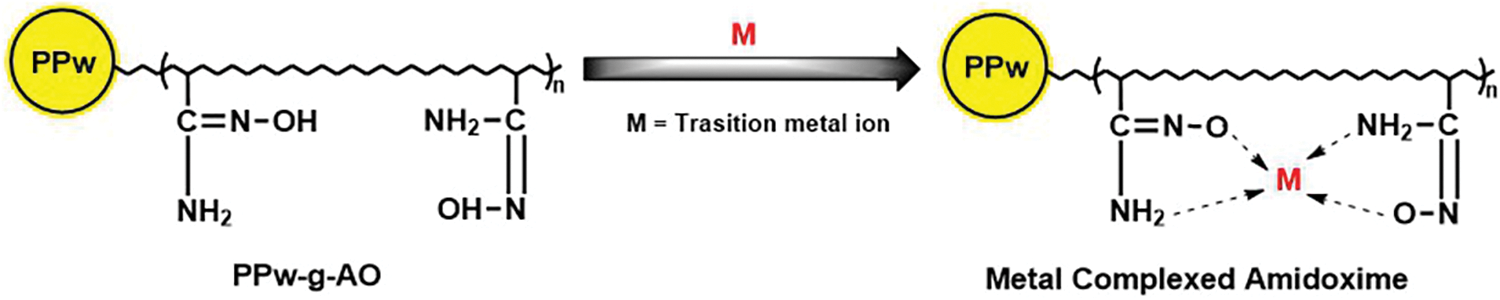

Chelating resins are capable of targeting both valuable metals and impurities [9,10]. Based on the functional groups chemically bonded to the polymer backbone, chelating resins are used in various applications, including the separation and pre-concentration of metal ions, acting as chemical reagents for metal ion complexation, removing toxic metals from aqueous solutions, and facilitating the recovery of rare earth elements [10–12]. Amidoxime-based adsorbents, a type of chelating resin derived from polypropylene waste, demonstrate superior metal ion adsorption capabilities due to the high binding affinity of the amidoxime functional groups. These materials possess significant mechanical strength, chemical stability in harsh environments, and resistance to thermal degradation, ensuring their durability for repeated adsorption cycles [13,14]. The radiation-grafting of amidoxime onto the polymer backbone further enhances surface reactivity, improving overall adsorption efficiency. Moreover, these adsorbents contribute to environmental sustainability by transforming plastic waste into valuable materials, with the added benefit of being recyclable, making them ideal for metal recovery and wastewater treatment applications [15–17]. Amidoxime-based chelating resins are used for the removal of transition elements (Fig. 1) from different media [16]. However, the application of polypropylene waste amidoxime resins to remove iron from soil or leached geological samples remains unexplored.

Figure 1: General reaction of amidoxime resin with bivalent metal ions

The objective of the present study is to develop a novel method for removing iron from leached geological samples, to replace conventional extraction techniques with a more cost-effective and eco-friendly alternative. To accomplish this, batch adsorption experiments were carried out using an indigenously synthesized adsorbent, based on polypropylene waste amidoxime, radiation grafted at 10 kGy (PPw-g-AO-10) [17]. Various parameters including pH, contact time of resin with ferric ions, adsorbent dose, and effect of initial concentration of Fe3+ ions were optimized for achieving maximum adsorption capacity (Qm). Additionally, regeneration studies were performed on the fully saturated resin using various desorption techniques.

The analysis of aluminum and iron was carried out using an Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (Z-8000, FAAS Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan) and a single-beam UV-Vis spectrophotometer (PG Instruments). For iron analysis with AAS, the instrument settings were optimized as follows: the wavelength was set to 372.4 nm, the slit width to 0.4 nm, and the lamp current to 10 mA. The air pressure was maintained at 1.6 kg/cm², and the samples were analyzed using an acetylene-air flame.

Similarly, aluminium analysis using AAS was performed under specific conditions: the wavelength was set to 309.3 nm, the slit width to 1.3 nm, and the lamp current was held constant at 10 mA. The air pressure was again adjusted to 1.6 kg/cm2, and a nitrous oxide-acetylene flame was employed for sample analysis. To minimize flame interference, potassium chloride (KCl) was added as a buffer to all standards and samples.

For aluminium determination using the UV-Vis spectrophotometer, the instrument was preheated for approximately 1 h to ensure stability. Measurements were taken at a wavelength of 275 nm for aluminium.

Indigenously synthesized polypropylene waste amidoxime-based radiation grafted adsorbent (PPw-g-AO-10) was used for the removal of iron from leached geological samples. Further, an appropriate concentration of ferric chloride solution was prepared from the oxidation of ferrous ammonium sulphate solution (99.9% purity, Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) by dissolving its suitable amount in deionized water (type-I) produced from Millipore Simplicity UV water purification plant (Billerica, MA, USA).

3.2 Preparation of Ferric Chloride Solution

Ferric chloride (FeCl3) solution was prepared by the oxidation of ferrous ammonium sulfate [(NH4)2Fe(SO4)2·6H2O] with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). For the preparation of a 5000 ppm standard solution of FeCl3, 17.19 g of ferrous ammonium sulfate was dissolved in 100 mL of type I water in a 500 mL beaker. 26 mL of 27% hydrochloric acid and 2 mL of 50% hydrogen peroxide were also added to this mixture. Then mixture was heated for 5 min at 70°C and cooled to room temperature. In the end, the solution was transferred to a 500 mL graduated flask and the total volume was up to 500 mL with Type-I water [18]. Solutions of different concentrations were prepared using a dilution formula.

Adsorption studies were conducted through batch experiments with PPw-g-AO-10 adsorbent. The appropriate concentration of Fe3+ standard solutions was agitated with adsorbent using an orbital shaker at 240 oscillations/min. The concentration of Fe3+ ions in solution before and after adsorption was determined using AAS at 372.4 nm wavelength in air/acetylene flame. The adsorption capacity Q (mg/g) of resin for ferric ions was calculated from the mean of triplicate measurements using Eq. (1):

where Q is the adsorption capacity of adsorbent for ferric ions, Co and Ce denote the initial and equilibrium concentrations (mg/L) of ferric ions before and after adsorption, respectively, W is the weight (g) of the adsorbent taken, and VS is the volume (mL) of standard or sample solution added to the adsorbent.

20 mg adsorbent (PPw-g-AO-10) was taken in five sample tubes separately. A 5 mL ferric chloride standard solution with pH levels of 0.6, 1.0, 1.4, 1.5, and 1.6 was added separately to each tube. The tubes were then shaken at 240 rpm for 1.5 h. After filtration, the raffinate was collected.

3.3.2 Contact Time Optimization

60 mg of resin and 15 mL standard solution of ferric chloride (pH 1.4) were mixed in a sample tube at 240 rpm. pH of the solution was adjusted with 20% sodium carbonate solution. A 2 mL sample was pipetted at 20, 40, 60, 80, 100, and 120 min from the solution and analyzed for iron using AAS.

3.3.3 Effect of Adsorbent Dose

20, 40, 60, 100 and 150 mg adsorbent was taken in five different sample tubes in which 5 mL ferric chloride standard solution (4500 ppm) having pH 1.4 was added. Then these tubes were shaken at 240 rpm for 80 min in an orbital (TK-6,ZiHe International Trade Co. (Shanghai), China) followed by filtration. The filtrate was analyzed for iron through for AAS.

3.3.4 Effect of Initial Concentration of Fe (III)

pH of ferric chloride standard solutions (2500, 3000, 3500, 4000, 4500, and 5000 ppm) was raised up to 1. 4 with 20% sodium carbonate. Then 5 mL of each standard was mixed at 240 rpm for 80 min, separately, with 20 mg of resin in 6 sample tubes. After filtration, the resulting filtrate was used for analysis of iron.

Different regenerating agents were evaluated in different concentrations and volumes for the regeneration of the PPw-g-AO-10 adsorbent. Specifically, 40 mL of 1 M oxalic acid, 1 M tartaric acid, 0.2 N nitric acid, and 0.5 N nitric acid were individually agitated with 20 mg of fully loaded resin in separate sample tubes, with 240 rpm agitation. After 1 h of agitation, the solutions were filtered. The resin was subsequently washed twice with distilled water and then reintroduced for subsequent loading cycles. The regeneration efficiency of the adsorbent was calculated by using Eq. (2):

3.3.6 Application of Resin on Geological Samples

A 10 mL multi-acid leached soil sample was treated with 300 mg resin at pH 1.4 for 90 min in the orbital shaker with 240 rpm agitation. The resulting raffinate was analyzed for iron through AAS.

Batch adsorption studies were performed using a standard solution with an iron concentration of 4500 ppm. During these studies, parameters including pH, contact time, adsorbent dose, and the initial concentration of ferric ions were optimized. Following the optimization, the resin was regenerated for further use.

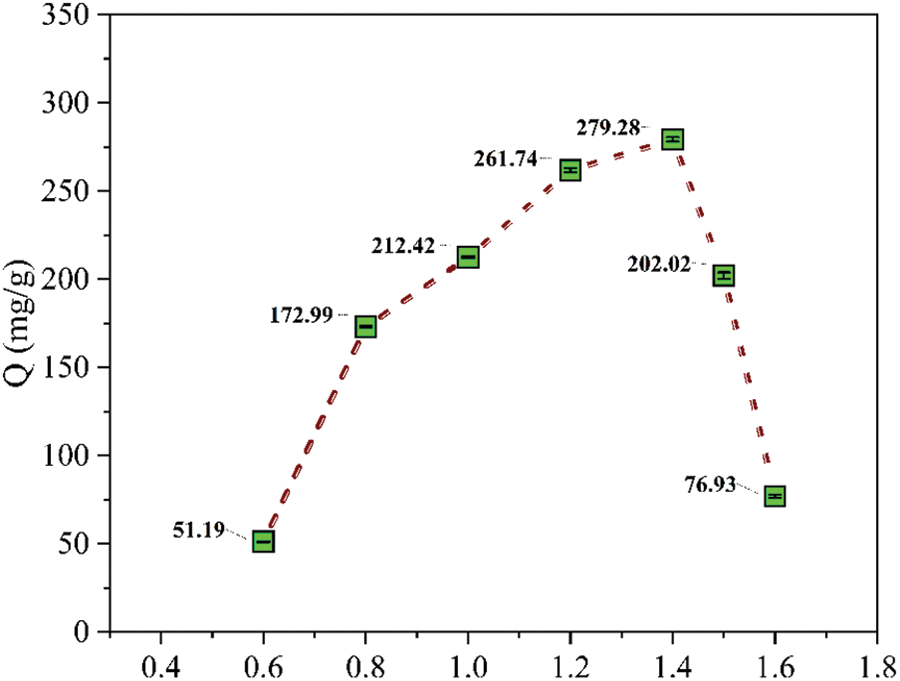

4.1 Effect of pH on Adsorption Capacity

Optimizing pH is critical for maximizing the adsorption capacity of the resin. Fig. 2 demonstrates the effect of pH on the uptake of ferric ions. The adsorption capacity (Q) of the adsorbent increases with pH. At lower pH values, the adsorption capacity is almost diminished due to the protonation of the amino groups (NH2) in amidoxime, which induces electrostatic repulsion with Fe3+ ions. As pH rises, the concentration of H+ ions decreases, providing more active binding sites for the complexation of Fe3+ ions. The maximum adsorption capacity was achieved at 1.4 pH; after that pH, a sudden decrease in the adsorption capacity of the resin was observed due to the precipitation of Fe(OH)3 [19]. Hence, the optimized pH was 1.4 and all further parameters were adjusted at 1.4 pH to avoid precipitation.

Figure 2: Effect of pH on ferric ions uptake by PPw-g-AO-10 (Mass = 20 mg, Co = 4500 ppm, Vol. = 5 mL, t = 100 min, T = 293 K)

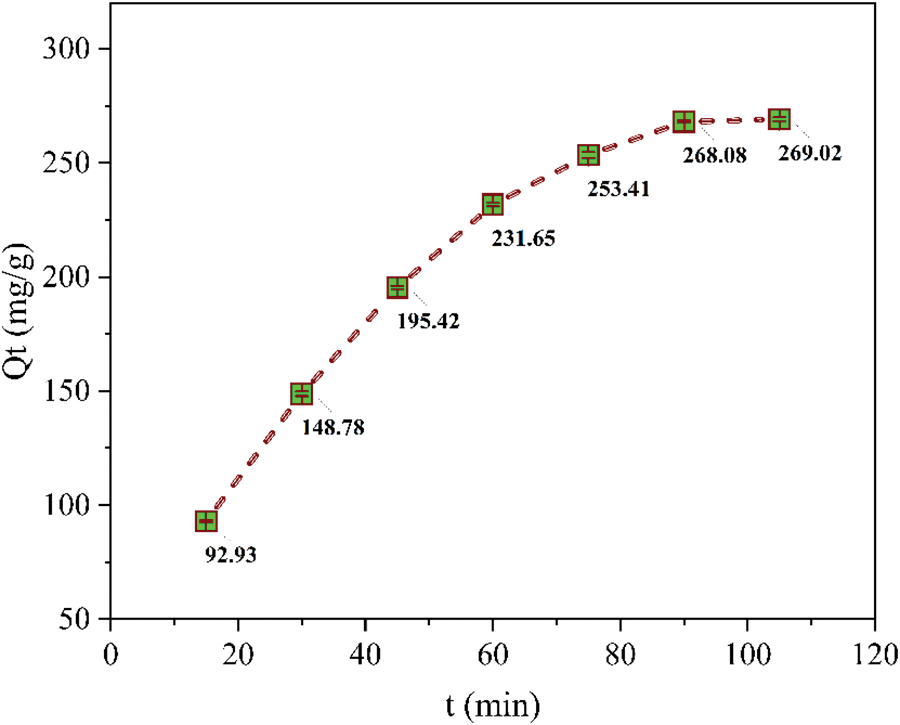

4.2 Effect of Contact Time on Adsorption Capacity

Contact time is a critical determinant of reaction efficiency in adsorption processes. During the optimization of contact time, all other experimental parameters like pH, initial concentration of ferric ions, agitation speed, adsorbent dose, and temperature were kept constant. Fig. 3 depicts the influence of contact time on the uptake of Fe3+. The removal of ferric ions from the solution occurred in two distinct phases: an initial rapid uptake followed by a subsequent slower uptake. The rapid increase in adsorption capacity observed initially can be attributed to the high availability of active sites on the adsorbent [19,20]. Subsequently, the adsorption capacity decreased, and equilibrium was achieved after 90 min. The adsorption capacity increased from 92.93 mg/g at 20 min, gradually reaching a constant value of 268.08 mg/g after 90 min. Beyond this point, no significant changes in the equilibrium concentration were observed, indicating that adsorption equilibrium had been reached. Therefore, a contact time of 90 min was selected as the optimum for all subsequent experiments.

Figure 3: Effect of contact time on ferric ions uptake by PPw-g-AO-10 (Mass = 20 mg, Vol. = 5 mL, Co = 4500 ppm, pH = 1.4, T = 293 K)

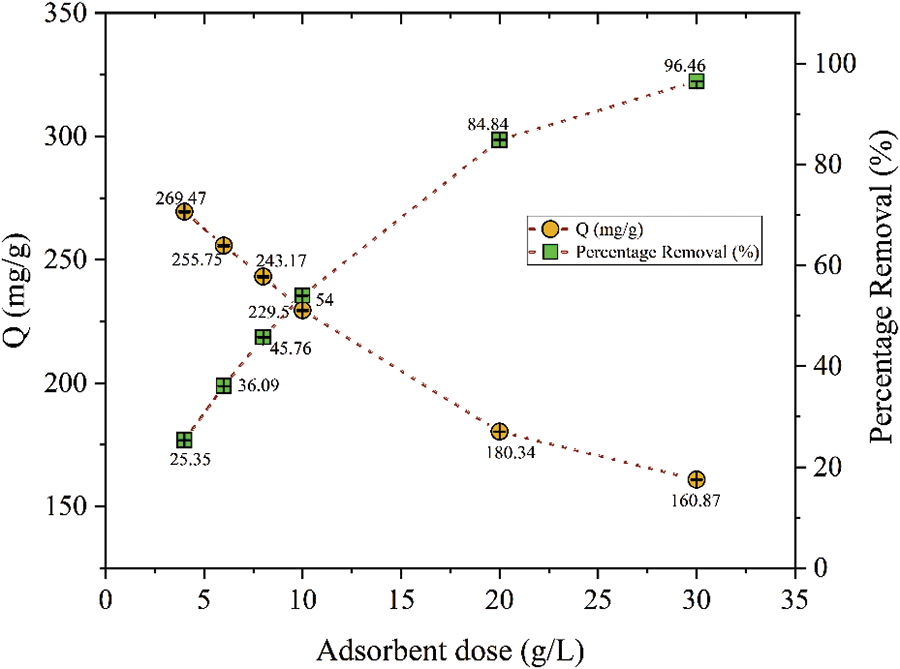

4.3 Effect of Adsorbent Dose on Adsorption Capacity

The adsorbent dose is an important parameter as it provides information about the extent of metal removal from the solution. During the study of this parameter, other conditions were kept constant except the adsorbent dose [21]. The effect of the adsorbent dose on the percentage removal of ferric ions was investigated by varying it from 4 to 30 g/L as shown in Fig. 4. Ferric ion removal efficiency increased as the adsorbent dose increased because the contact area of adsorbent particles increased concerning the availability of ferric ions in the solution. In contrast, the adsorption capacity (mg/g) of the resin decreased with an increase in the adsorbent dose (g/L) as agglomeration and aggregation were higher at higher adsorbent doses. As a result, the solute has to take a longer path to access the adsorption sites [22]. Maximum adsorption capacity (Qm) 269.47 mg/g was observed when the adsorbent dose was 4 g/L due to the least agglomeration of adsorption sites in the smaller amount of PPw-g-AO-10 adsorbent. The maximum iron removal efficiency of 96.46% can be achieved with the adsorbent dose of 30 g/L [23].

Figure 4: Effect of adsorbent (by PPw-g-AO-10) dose on Fe (III) adsorption capacity and its percentage removal (pH = 1.4, Vol. = 5 mL, Co = 4500 mg/L, t = 90 min, T = 293 K)

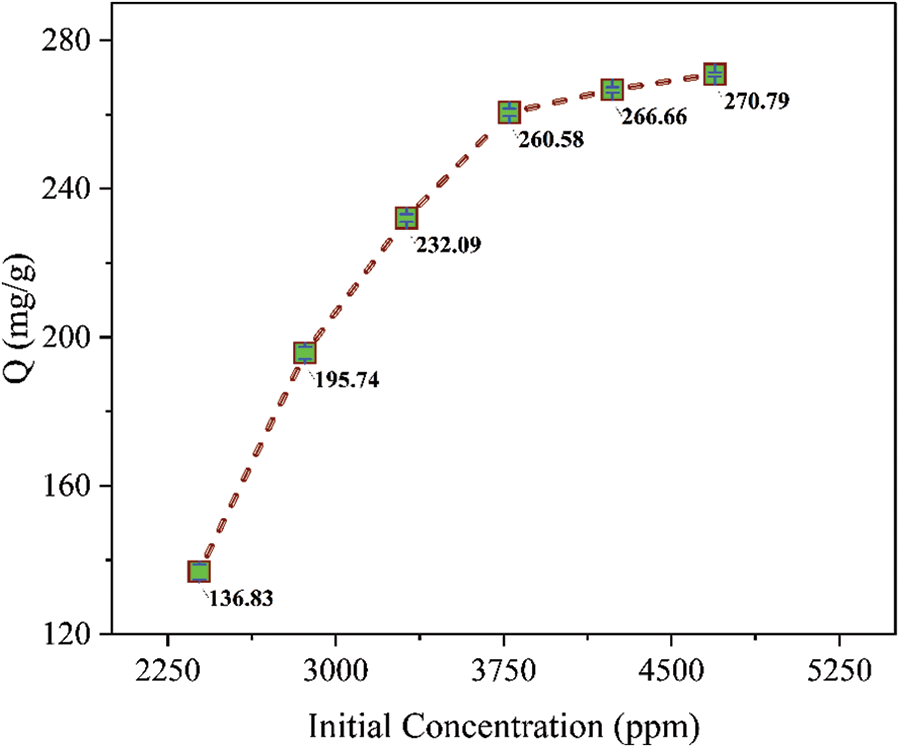

4.4 Effect of Initial Concentration of Ferric Ions on Adsorption Capacity

The concentration of the adsorbate is the driving force that overcomes the mass transfer resistance of metal ions between the aqueous solution and the adsorbent [24]. Fig. 5 indicates the effect of the initial concentration of Fe3+ ions on the adsorption capacity of the adsorbent. Initially, at lower concentration of ferric ions, increase in adsorption capacity is high due availability of more active sites for the adsorbate. With increase in initial concentration of ferric ions, the number of active sites on the adsorbent becomes the limiting factor hence decreasing the metal ion uptake.

Figure 5: Effect of initial concentration of ferric ions adsorption capacity of PPw-g-AO-10 (pH = 1.4, Vol. = 15 mL, mass = 50 mg, t = 90 min, T = 293 K)

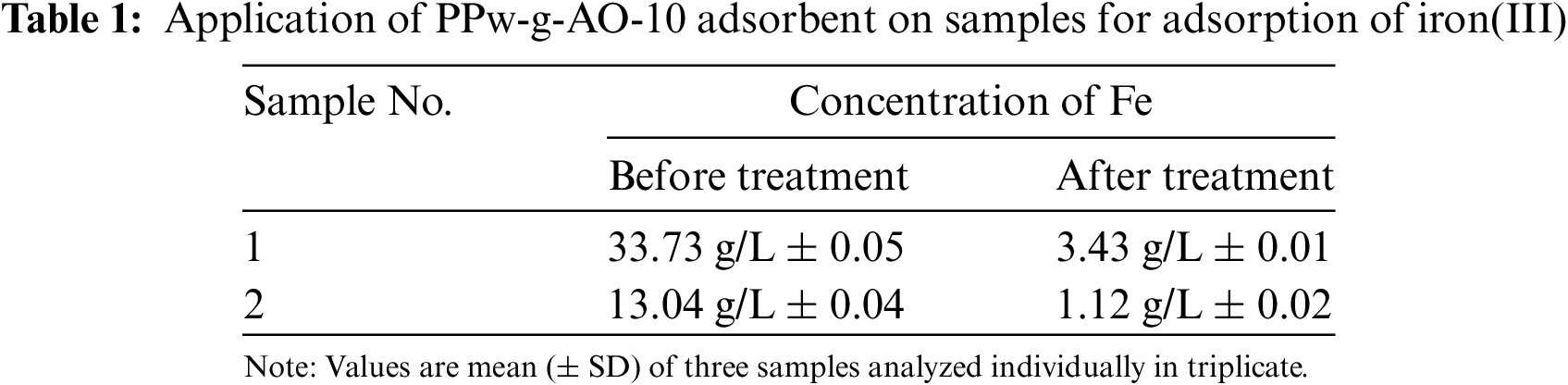

4.5 Application of Resin on Geological Samples

After optimizing the necessary parameters, the resin was applied to samples leached with multiple acids. Table 1 shows the initial concentrations of iron in sample 1 and sample 2, measured at 33.73 and 13.04 g/L, respectively. Following treatment with the resin, the iron concentrations in sample 1 and sample 2 decreased to 3.43 and 1.12 g/L, respectively. This indicates that PPw-g-AO-10 resin effectively removed iron from the geological samples, achieving an overall removal efficiency of approximately 91%. However, during parameter optimization using standard solutions, the resin demonstrated a higher iron removal efficiency of 96.46%. The observed 5% reduction in efficiency in the geological samples can be attributed to the presence of other transition metals, which were also adsorbed onto the resin along with the iron [19,25].

The precision of the findings related to iron concentrations before and after treatment are assessed based on the reported measurements and their associated standard deviations. The low standard deviations—±0.05 for Sample 1 before treatment, ±0.04 for Sample 2 before treatment, and ±0.01 and ±0.02 after treatment—indicate a high degree of precision, suggesting that the measurements are consistently reproducible under unchanged conditions. This consistency reflects the reliability of the methodology used for removal of iron from geological samples [26].

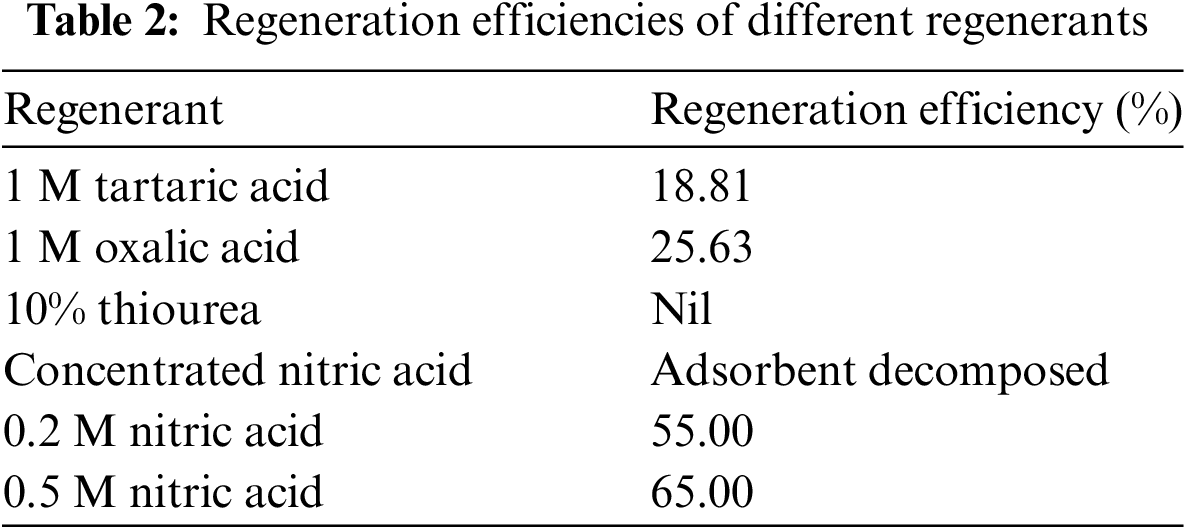

To enhance the reusability of the resin and lower operational costs, regeneration of the adsorbent was performed. Table 2 presents the regeneration efficiencies for various reagents. Regeneration with 1 M tartaric acid and 1 M oxalic acid showed minimal effectiveness [27]. A 10% thiourea solution was also ineffective in regenerating the resin, and concentrated nitric acid led to polymer degradation, causing the resin to become sticky [22–24]. Conversely, 0.5 N nitric acid achieved the highest regeneration efficiency at 65%. This effectiveness is due to nitric acid generating H+ ions which displace the chelated ferric ions from the adsorbent. Moreover, the regeneration efficiency is low because the trivalent iron ion entangled among three amidoxime groups [20,21].

The removal of iron from geological samples can be efficiently achieved using various low-cost polymeric resins. Polypropylene waste amidoxime-based radiation grafted adsorbent has demonstrated exceptional effectiveness in extracting iron at room temperature. This adsorbent provides considerable environmental and resource recovery benefits. The radiation grafting of amidoxime groups onto polypropylene significantly enhances the adsorbent’s ability to chelate and remove iron from leached geological samples, thereby increasing process efficiency and improving the purity of raw materials. Furthermore, this approach is cost-effective, as it utilizes recycled polypropylene, which reduces production costs while maintaining optimal performance. The resin’s affinity for ferric ions is influenced by factors such as electronegativity, ionic radius, and hydrolysis constants. Experimental parameters, including pH, contact time, adsorbent dosage, and adsorbate concentration, have a notable impact on the adsorption process, with pH being the most influential variable for effective iron removal. Maximum adsorption capacity 269.02 mg/g at pH 1.4 with contact time 90 min and with initial ferric ion concentration 4500 mg/L was observed. After treating 10 mL of sample with 300 mg of PPw-g-AO resin, the percentage of iron removal from the leach solution was approximately 91%, which is 5% lower than the removal achieved with the standard solution during parameter optimization. This suggests that the presence of other transition metals likely impacts adsorption efficiency, as their ionic radii may be similar to those of ferrous or ferric ions, leading to competitive adsorption. Although the resin was regenerated using various agents, 0.5 N HNO3 achieved the highest regeneration efficiency at 65%, which remains relatively low and presents an area for improvement. Further optimization of regeneration techniques is recommended as a potential focus for future research.

Acknowledgement: We thank to Rector PIEAS, Islamabad for providing conductive environment for research work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Performed analysis, result interpretation and draft manuscript preparation: Hafiz Zain Ul Aabidin; Co-supervision, results interpretation and review: Muhammad Inam Ul Hassan; Concept and design: Tariq Yasin; Perform supervision and validate the results: Muhammad Zubair Rahim; Correspondence, proof reading and writeup: Asif Raza. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Heilig ML. Process for separation of iron from metal sulphate solutions and hydrometallurgic process for the production of zinc. ACM Siggraph Comput Graph. 1994;28:131–4. [Google Scholar]

2. Cabrera F, Madrid L, De Arambarri P. Use of ascorbic and thioglycollic acids to eliminate interference from iron in the aluminon method for determining aluminium. Analyst. 1981;106(1269):1296–301. doi:10.1039/an9810601296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang JC, Cheng K. Precipitation of tellurium with bismthiol II. Micrichem J. 1970;15(II):607–21. [Google Scholar]

4. Farouq R, Selim Y. Solvent extraction of iron ions from hydrochloric acid solutions. J Chil Chem Soc. 2017;2(2):60–2. doi:10.4067/S0717-97072017000200002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gudeczauskas D, Natalie CA. Removal of iron fro aluminum chloride leach liquoes by ion exchange. Hydrometallurgy. 1985;14(3):369–85. doi:10.1016/0304-386X(85)90045-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Li M, He Z, Zhou L. Removal of iron from industrial grade aluminum sulfate by primary amine extraction system. Hydrometallurgy. 2011;106(3–4):170–4. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2010.12.018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Health Effects Assessment for Methyl Isobutyl Ketone. EPA/600/8- 88/045; 1988. [Google Scholar]

8. Shiro K, Klass M. Encyclopedia of Polymeric Nanomaterials. Springer; 2021. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-36199-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Jianfui C, Sarjadi MS, Musta B, Sarkar MS, Rahman ML. Synthesis of sawdust-based poly(amidoxime) ligand for heavy metals removal from wastewater. ChemistrySelect. 2019;4(11):2991–3001. doi:10.1002/slct.201803437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Khedr RF. Radiation-grafting on polypropylene copolymer membranes for using in cadmium adsorption. Polymers. 2023;15(3):686. doi:10.3390/polym15030686. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Garg BS, Sharma RK, Bhojak N, Mittal S. Chelating resins and their applications in the analysis of trace metal ions. Microchem J. 1999;61(2):94–114. doi:10.1006/mchj.1998.1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Panda H, Tiadi N, Mohanty M, Mohanty CR. Studies on adsorption behavior of an industrial waste for removal of chromium from aqueous solution. South Afr J Chem Eng. 2017;23(3):132–8. doi:10.1016/j.sajce.2017.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Pesaventoa M, Biesuz R. Characterization and applications of chelating resins as chemical reagents for metal ions, based on the Gibbs-Donnan model. React Funct Polym. 1998;36(2):135–47. doi:10.1016/S1381-5148(97)00105-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Page MJ, Soldenhoff K, Ogden MD. Comparative study of the application of chelating resins for rare earth recovery. Hydrometallurgy. 2017;169(2):275–81. doi:10.1016/j.hydromet.2017.02.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Sardar MN, Rahman N, Sultana S, Dafader NC. Preparation of amidoximated acrylonitrile-g-waste polypropylene adsorbent by radiation grafting method and its application on the adsorption of Cr (VI) from aqueous medium. Res Sq. 2021;13(5):1000307. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-934930/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kazemi M, Faisal Kabir S, Fini EH. State of the art in recycling waste thermoplastics and thermosets and their applications in construction. Resourc Conservat Recycl. 2021;174:105776. doi:10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Khedr RF. Synthesis of amidoxime adsorbent by radiation-induced Grafting of acrylonitrile/acrylic acid on polyethylene film and its application in Pb removal. Polymers. 2022;14(15):3136. doi:10.3390/polym14153136. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Hassan ul MI, Taimur S, Yasin T. Upcycling of polypropylene waste by surface modification using radiation-induced grafting. Appl Surf Sci. 2017;422:720–30. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.06.086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Zhou L, Sanzolone RF, Survey USG. Removal of iron interferences by solvent extraction for geochemical analysis by atomic absorption spectroscopy. Talanta. 1985;32(6):3–6. [Google Scholar]

20. Thermo-Calc Software. Educational material: Pourbaix diagrams. Stockholm, Sweden, 2014. [Google Scholar]

21. Taimur S, Hassan MI, Yasin T. Removal of copper using novel amidoxime based chelating nanohybrid adsorbent. Eur Polym J. 2017;95:93–104. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2017.08.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Tang N, Liang J, Niu C, Wang H, Luo Y, Xing W, et al. Amidoxime-based materials for uranium recovery and removal. J Mater Chem A. 2020;8(16):7588–625. doi:10.1039/C9TA14082D. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ratnitsai V, Wongjaikham W, Wongsawaeng D, Kohmun K, Santibenchakul S, Narkpiban K. Synthesis of amidoxime adsorbent prepared by radiation grafting on upcycled low-density polyethylene sheet for removal of heavy metals from wastewater. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):1–16. doi:10.1038/s41598-024-69320-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Jiang J, Ma XS, Xu LY, Wang LH, Liu GY, Xu QF, et al. Applications of chelating resin for heavy metal removal from wastewater. E-Polymers. 2015;15(3):161–7. [Google Scholar]

25. Amaibi PM, Egong JF, Iwe CR, Obunwo CC. Adsorption and kinetic studies for removal of fluoride in aqueous system by activated carbon produced from lemon peels. J Appl Sci Environ Manag. 2024;28(5):1413–9. [Google Scholar]

26. González-Rodrı́guez L, Hidalgo-Rosa Y, Garcı́a JOP, Treto-Suárez MA, Mena-Ulecia K, Yañez O. Study of heavy metals adsorption using a silicate-based material: experiments and theoretical insights. Chem Phys Impact. 2024;9:100714. [Google Scholar]

27. Liu Y, Biswas B, Hassan M, Naidu R. Green adsorbents for environmental remediation: synthesis methods, ecotoxicity, and reusability prospects. Processes. 2024;12(6):1–24. [Google Scholar]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools