Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Recent Advancements in Nanocomposites-Based Antibiofilm Food Packaging

1 Department of Biotechnology, School of Life Science and Biotechnology, Adamas University, Kolkata, 700 126, West Bengal, India

2 Integrated Science and Engineering Division (ISED), Underwood International College, Yonsei University, Incheon, 21983, Republic of Korea

3 Department of Biological Sciences, School of Life Science and Biotechnology, Adamas University, Kolkata, 700 126, West Bengal, India

4 Key Laboratory of Equipment and Informatization in Environment Controlled Agriculture, Ministry of Agriculture, Hangzhou, 310058, China

5 College of Biosystems Engineering and Food Science, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, 310058, China

6 Department of Chemistry and Nanoscience, Ewha Womans University, Seodaemun-gu, Seoul, 03760, Republic of Korea

* Corresponding Authors: Joyjyoti Das. Email: ; Madhumita Patel. Email:

# Contributed equally to this paper

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(2), 411-433. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2024.059156

Received 29 September 2024; Accepted 20 November 2024; Issue published 14 July 2025

A correction of this article was approved in:

Correction: Recent Advancements in Nanocomposites-Based Antibiofilm Food Packaging

Read correction

Abstract

The food industry prioritizes food safety throughout the entire production process. This involves closely monitoring and evaluating all potential sources of biological or chemical contamination, starting from entering raw materials into the production chain and continuing to the final product. Biofilms on food surfaces or containers can harbor dangerous pathogens, such as Listeria monocytogenes. Therefore, it is essential to continuously manage microbial contamination on food contact surfaces to prevent foodborne infections. Recently, there has been increasing interest in using nanomaterials as surface coatings with antimicrobial properties in the food industry, especially since traditional disinfectants or antibiotics may contribute to developing resistance. However, the use of antibiofilm materials for long-term food storage remains underexplored, and there is a notable lack of focused reviews on nanomaterial-based antibiofilm coatings specifically for long-term food preservation. This review aims to consolidate recently reported nanoparticle-based antibiofilm food packaging materials. We discuss the effectiveness of various metal and metal oxide nanoparticles and biopolymer nanocomposites in combating biofilms. Additionally, we highlight the growing importance of biodegradable nanocomposite materials for antibiofilm food packaging. Furthermore, we explore the mechanisms of action, processing methods, and safety aspects of these nanomaterials being developed for food packaging applications.Keywords

Food packaging is crucial in safeguarding food from spoilage and preserving its quality and shelf life. However, traditional packaging materials, primarily derived from petrochemicals, can have adverse effects on both human well-being and the environment [1,2]. Biobased packaging materials offer a promising solution to replace petrochemical-based packaging. These materials, derived from sustainable sources like plants, possess desirable properties for food packaging applications [3]. Nanomaterials, including nanoparticles and nanocomposites, are also being investigated for their potential applications in food packaging. These materials can enhance mechanical properties, improve barrier performance, and provide antimicrobial benefits. For instance, nanocomposites based on biobased polymers reinforced with nanoparticles can offer improved protection against oxygen and moisture, thereby extending the freshness and durability of processed food. Based on their objectives and functional requirements, food packaging can be categorized as passive packaging (for maintaining thermal stability and mechanical strength), active packaging (utilizing antimicrobial compounds, oxygen or free radical scavengers), intelligent or smart packaging (incorporating time-temperature and gas indicators), and sustainable or green packaging, which addresses environmental pollution concerns [4,5].

Biofilms are communities of bacteria that adhere to surfaces. They are not simply collections of individual bacteria, but rather complex populations with diverse gene expression profiles that contribute to their ecological success [6,7]. Biofilm formation relies on quorum sensing, a process of intercellular communication. During biofilm formation, individual cells aggregate on a surface and attach to extracellular polymeric substances (EPS). Bacterial biofilms make bacteria resistant to many antibiotics because the drugs cannot penetrate the biofilm structure [8]. As a result, biofilms are implicated in numerous bacterial diseases. Biofilm formation on medical devices such as implants, catheters, and dialysis equipment can be particularly problematic in hospital settings. Nanotechnology can be utilized to encapsulate or deliver quorum sensing inhibitors that disrupt the signaling pathways involved in biofilm formation, thereby preventing microorganisms from coordinating the formation of biofilms. Furthermore, nanotechnology-based biosensors integrated into food packaging can detect the presence and growth of biofilms [9].

In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the unique physicochemical properties of nanocomposites with antimicrobial properties in food packaging. Many review reports have primarily focused on the use of functional biopolymer-based nanocomposites [10], inorganic nanoparticles [11], and metal oxides [12] in food packaging. Recently, Qi et al. investigated the application of composite nanomaterials in addressing biofilm formation in the medical industry. They discussed the potential effectiveness of organic, inorganic, and organic–inorganic hybrid nanocomposites in traditional antibiofilm treatments as well as innovative phototherapy methods [13]. Jamwal et al. investigated the potential risks of using nanomaterials in food packaging while underscoring the necessity for continued advancements in this area [14]. Mishra et al. concentrated on biopolymer blends, biodegradable bio-nanocomposite materials, and the synthesis and characterization techniques currently employed in smart food packaging [15]. Their study highlighted the challenges hindering the widespread adoption of biopolymer nanocomposites and explored future opportunities for developing sustainable and innovative food packaging solutions. Similarly, Brandelli explored the role of nanotechnology in food packaging, particularly the use of nanostructured materials to produce packaging with antimicrobial properties [16]. The study emphasized how nanostructures can serve as carriers for natural antimicrobials, showcasing recent research demonstrating their potential to enhance food safety and extend shelf life. While several reports have been published, there is a lack of information on using nanocomposites to combat biofilm-forming microbes in food packaging applications.

In this review, we discuss the importance of nanotechnology-based approaches. We thoroughly discuss the effectiveness of nanoparticles made from silver, selenium, and metal oxides as antibiofilm agents. Finally, it highlights the growing popularity of biopolymer nanocomposites as antibiofilm materials for food packaging. By summarizing the application of each composite in different food systems, this review provides valuable information to food scientists for the development of innovative food packaging materials.

2 Strategies for Controlling Biofilm in the Food Industry

The food industry faces major challenges from biofilm-forming microorganisms, which not only spoil food and cause foodborne illnesses but also show high antibiotic resistance and harbor virulent factors [17]. This section describes the various strategies adopted by the food industry to control biofilm development. To combat foodborne illnesses, it is essential to prevent biofilm formation by regularly cleaning surfaces with strong chemical disinfectants like hypochlorites, quaternary ammonium compounds, peroxides, aldehydes, and phenols [18]. Additionally, the industry must adopt strategies to regulate microbial signaling pathways, disrupt mature biofilms using bacteriophages, and apply anti-quorum sensing (QS) compounds, matrix-degrading enzymes, and diguanylate cyclase inhibitors as antibiofilm agents. Anti-QS agents, such as those limiting N-acyl homoserine lactones (AHLs), are particularly effective. Moreover, eco-friendly antibiofilm coatings, nanotechnology, disinfectants, surfactants, essential oils, and non-thermal plasma are necessary to prevent biofilm formation. Addressing drug resistance and reducing excessive antibiotic use are crucial to combat persistent biofilms [19] (Scheme 1). While conventional biofilm control strategies have several intrinsic limitations, nanotechnology-empowered strategies for food preservation have started taking center stage in recent times due to their myriad benefits. These have been discussed at length in the subsequent section.

Scheme 1: Biofilm control strategies employed in the food industry

2.1 Nanotechnology to Manage Biofilm Formation

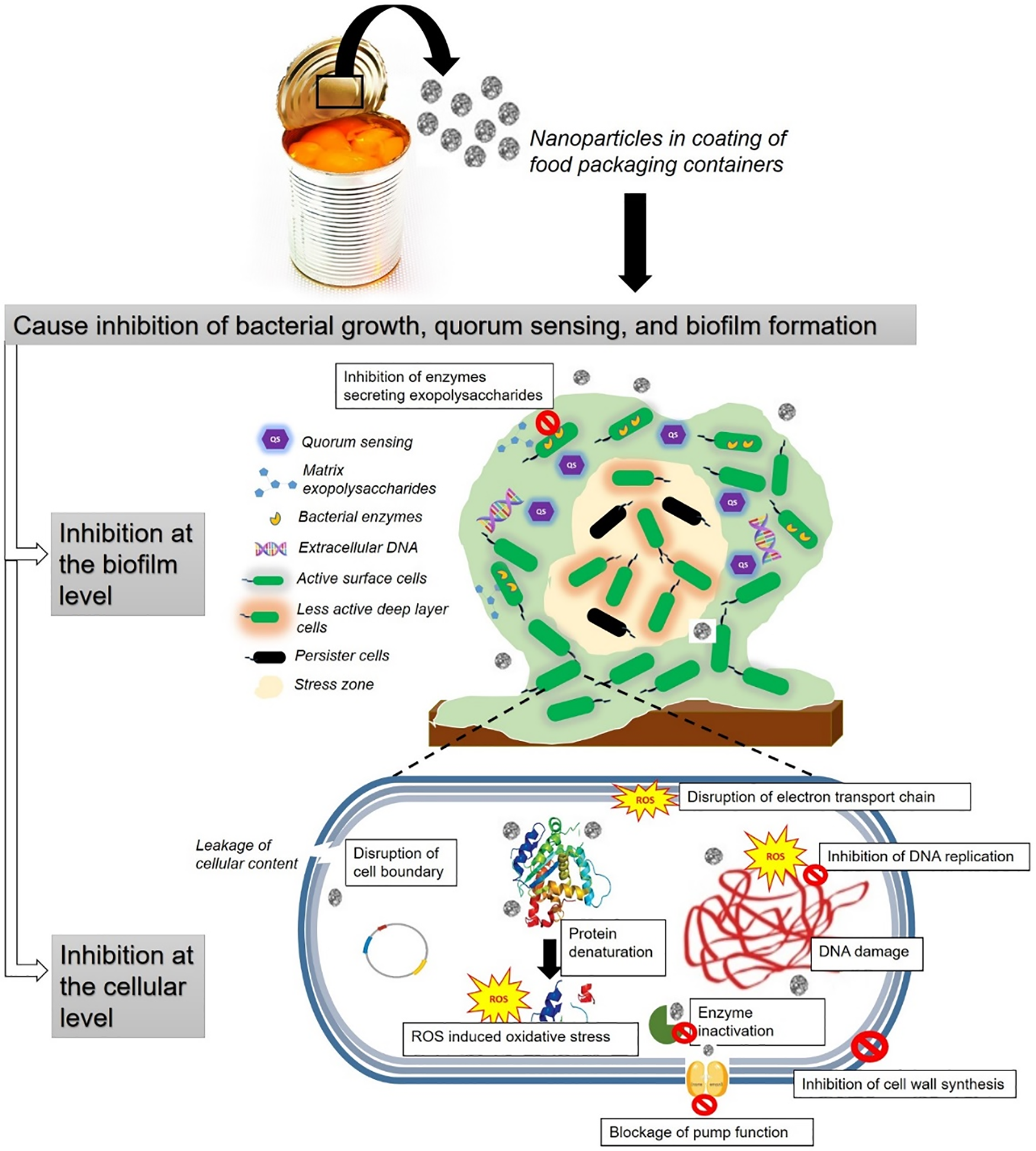

Researchers have been exploring the use of nanotechnology to combat bacterial infections caused by biofilms. Nanoparticles have shown great promise in fighting these infections, and research in this field is rapidly growing. These nanoparticles possess antimicrobial properties, effectively preventing the growth of biofilm-forming microorganisms. They can be integrated into packaging materials or applied as surface coatings to prevent biofilm formation actively. Biosensors can detect specific biofilm-related molecules, providing real-time feedback, allowing for actions such as alerting consumers or signaling the need for package replacement. Nanoscale surface modifications offer a viable approach to deter biofilm adhesion on food packaging by altering surface properties, making them less conducive to microorganism adhesion. Examples include nanostructured coatings, nanotextured surfaces, or hydrophilic/hydrophobic patterning, which repel biofilm-forming microorganisms [20]. Furthermore, nanocarriers can deliver biofilm-inhibiting agents or antimicrobial compounds directly to packaging surfaces, providing sustained antimicrobial effects and preventing biofilm formation over time [21]. The antimicrobial effectiveness of metal ions supported on nanostructures stems from their small size and high surface area, allowing enhanced interaction with bacteria. Their action is linked to reactive oxygen species production, causing DNA damage and oxidative stress in cells. Bacterial polysaccharides attract metal cations through electrostatic attraction, leading to changes in cell membrane structure and permeability. Metal ions on nanostructures can impair protein function through protein carbonylation, causing cellular damage. Additionally, metal oxides and ions disrupt DNA replication and cell division, impacting bacterial signal transduction (Scheme 2) [22]. Certain nanoparticles such as silver, selenium, metal oxide, and biopolymeric nanomaterials improve the treatment efficacy. The following subsections describe the different categories of antibiofilm nanomaterials and their merits and limitations.

Scheme 2: Mechanism of action of nanomaterials used for food packaging

2.1.1 Silver Nanoparticles against Biofilm

Silver nanoparticles (AgNPs) possess strong antimicrobial properties against various microbes, including those commonly found in biofilms [23]. Incorporating AgNPs into food packaging materials such as films or coatings can help prevent biofilm formation and reduce bacterial growth [24]. AgNPs disrupt bacterial adhesion and growth, inhibiting biofilm formation and maintaining the safety and quality of packaged food products [23]. The use of AgNPs against biofilm-forming microorganisms is outlined in Table 1.

A combination of AgNPs, gold nanoparticles (AuNPs), and chitosan has been shown to exhibit antibacterial characteristics, effectively inhibiting biofilm formation and reducing bacterial metabolic activity. Chitosan prevented biofilm development at concentrations ranging from 0.31 to 5 mg/ml, while nanoparticles combined with chitosan significantly reduced metabolic activity by at least 80%. The disruption of bacterial membranes by chitosan and AgNPs causes leakage of internal components from planktonic cells, further inhibiting microbial growth [23]. Additionally, combining zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnONPs) with AgNPs on polyester surfaces has shown significant efficacy in preventing biofilm formation by harmful bacteria such as Escherichia coli (E. coli) and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus). These nanoparticles also inhibit biofilms causing Listeria monocytogenes (L. monocytogenes). A combination of 850 ppm AgNPs and 400 ppm ZnONPs has demonstrated strong antibacterial effects, reducing E. coli CFU/cm2 levels by 5.80 log and S. aureus by 4.11 log. In humid conditions, AgNPs at 500 ppm effectively prevent biofilm formation by L. monocytogenes [25].

Furthermore, functionalized stainless-steel surfaces with silver coupons exhibit lower counts of adherent S. aureus cells compared to E. coli. Cathodic sputtering of silver onto stainless steel lowers the microbial load on surfaces, with silver ions from the coating reducing both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria. This highlights the potential use of silver-functionalized surfaces in the food industry to reduce microbial adhesion and biofilm formation [24]. Alumina discs coated with biogenic AgNPs show enhanced hydrophobicity and a significant reduction in microbial adhesion over 99.9% for both Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria, and over 90% for fungal isolates. These surfaces offer antibacterial properties, inhibit biofilm formation, and maintain biocompatibility with Caco-2 and HaCaT cell lines [26].

A study by Griffith et al. examined the antimicrobial effectiveness of silver zeolite coatings in minimizing contamination. Silver zeolite effectively prevents biofilm formation caused by common foodborne pathogens such as Listeria innocua (L. innocua) Seeliger and E. coli O157:H7. At a concentration of 0.3% w/v, silver zeolite inhibited L. innocua growth for up to 8 h. Its effectiveness against E. coli depended on dosage, showing reduced bacterial numbers after 4 h. This suggests silver zeolite’s potential as a coating material to enhance food safety and prevent microbial contamination on food-contact [27].

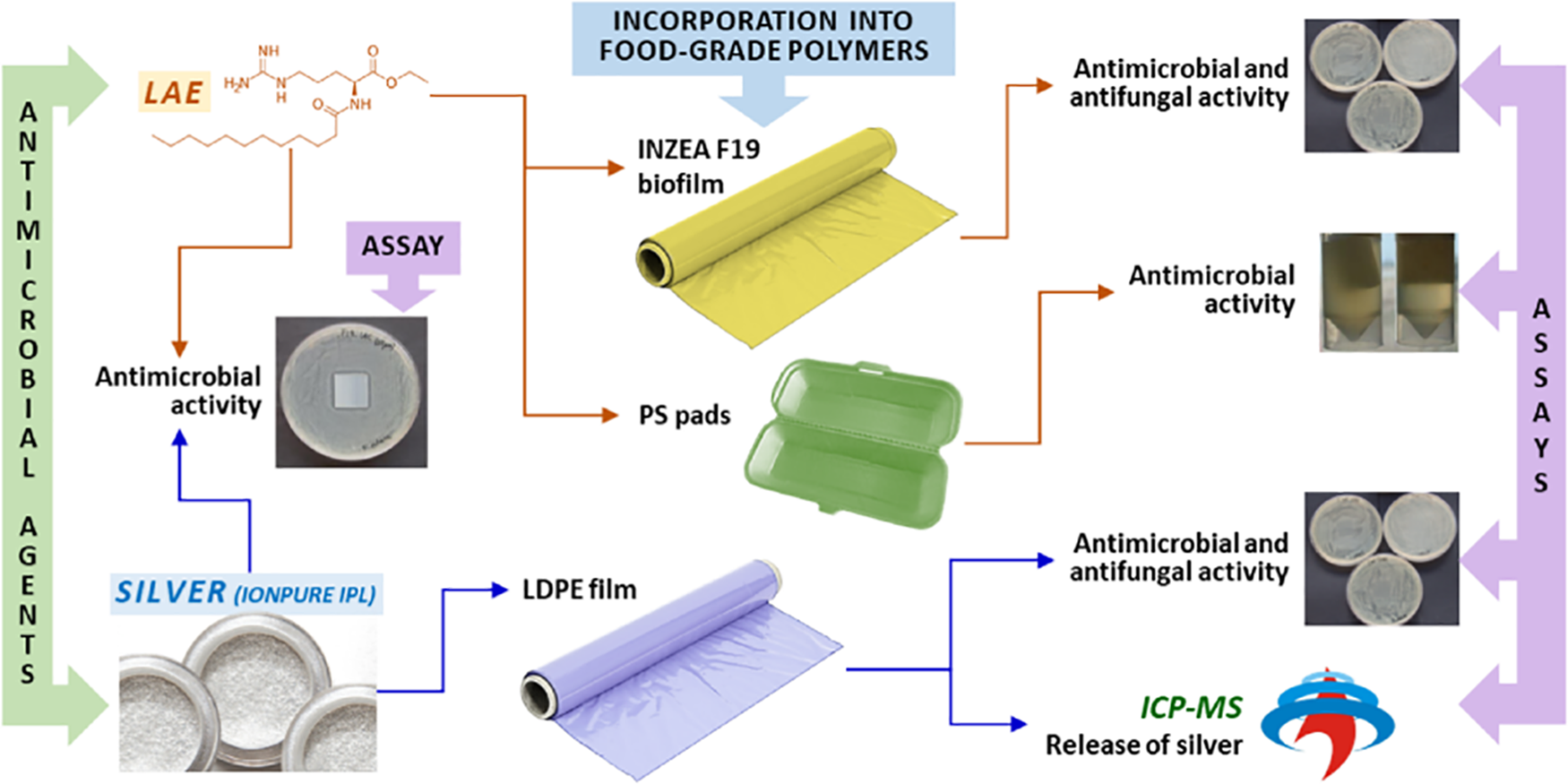

In a study conducted by [28], the antibacterial activity of two novel active films with silver, as IONPURE IPL, and ethyl lauroyl arginate (LAE®) respectively was assessed. One of these films was fabricated by incorporating silver in a low-density polyethylene (LDPE) matrix while the other was fabricated using an LAE® incorporated biofilm material INZEA F19. While silver incorporated LDPE films showed no antibacterial activity against E. coli and Aspergillus flavus, LAE® incorporated INZEA F19 reduced the growth of Salmonella enterica (S. enterica) but did not inhibit the growth of Aspergillus flavus. Interestingly, a 99.99% reduction in growth of Pseudomonas putida was observed when active polystyrene (PS) pads incorporated with LAE® were used. Notably, LAE® retained its antibacterial action against S. enterica even after thermal treatment at 180°C for 6 and 15 min (Fig. 1) [28].

Figure 1: Diagrammatic illustration of silver incorporation and ethyl lauroyl arginate in different matrices [28]

The effects of AgNP-functionalized stainless-steel surfaces on biofilm formation and bacterial adhesion were thoroughly examined. Thin silver film coatings on polybutylene adipate-co-terephthalate (PBAT) and cellulose nanocrystal (CNC) nanocomposites showed improved crystallinity, ranging from 51% to 56%. These nanocomposites, created by solution casting with varying CNC concentrations (0.8, 1.5, and 2.3 wt%) and coated with silver thin films using magnetron sputtering, led to a significant 56% reduction in E. coli-induced biofilm, indicating potential use in food packaging [29]. Similarly, a poly (dimethyl siloxane) (PDMS) coating with AgNPs demonstrated remarkable antimicrobial activity, showing a 22-fold increase in effectiveness against E. coli and S. aureus compared to untreated PDMS. This was achieved using the solution blow spraying (SBS) technique to deposit AgNPs on partly crosslinked PDMS [30].

Additionally, the modification of a poly(butylene succinate-co-terephthalate) (PBST) matrix with Magnesium oxide (MgO)/AgNPs created PBST/MgO/Ag nanocomposite films. These films not only enhanced the mechanical, thermal, and barrier properties of the matrix but also exhibited excellent antibacterial activity against S. aureus, E. coli, and Salmonella paratyphi [31]. Furthermore, a study developed an antimicrobial polymer blend with immobilized fine silver nanophases (~25 nm), showing exceptional efficiency in inhibiting foodborne pathogens such as S. aureus and S. enterica. The biomaterial showed exceptional efficiency in inhibiting the mentioned pathogens, making it a promising biodegradable food packaging material [32].

2.1.2 Selenium Nanoparticles against Biofilm

Nanostructures made of silver, copper, zinc, titanium, and selenium have shown potential in the field of food safety and technology, despite potential hazards associated with some of them [34,35]. Table 2 presents the use of selenium nanoparticles (SeNPs) as antibiofilm food packaging materials. Selenium plays a role in thyroid hormone metabolism, cellular redox state regulation, and protection against reactive oxygen species. SeNPs were synthesized using the cell-free supernatant of Bacillus licheniformis, which was isolated from food wastes. Six foodborne pathogens, including Enterococcus faecalis, Bacillus cereus, E. coli O157:H7, S. aureus, Salmonella enteritidis, and S. Typhimurium, were found to be susceptible to the antibiofilm and antimicrobial properties of biosynthesized selenium nanoparticles with a diameter range of 10–50 nm [35]. The SeNPs showed a minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC90) of 25 mg/mL against all tested bacteria, effectively inhibiting their growth. Additionally, the SeNPs displayed antibiofilm activity at a concentration of 20 mg/mL against all examined bacteria, except B. cereus. Furthermore, the established biofilms were removed at concentrations of 75 mg/mL, and the SeNPs did not exhibit any toxicity to Artemia larvae [35]. Ullah et al. [21] conducted a study using SeNPs produced by Bacillus subtilis, and their antibacterial activity was assessed using the agar overlay technique. The results demonstrated that the SeNPs exhibited similar antibacterial effects against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Salmonella typhi, and S. aureus at concentrations of 150 and 200 μg/mL. Notably, the SeNPs caused breakdown of the bacterial cell membrane in both S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Significant anti-biofilm activity was observed at 700 μg/mL concentration against pathogenic strains capable of forming biofilms by SeNPs. The SeNPs dispersed biofilms of P. aeruginosa (85.7%), S. typhi (89.6%), and S. aureus (78.3%) within a time span of 15 min [21].

2.1.3 Metal Oxide Nanoparticles against Biofilm

Metal oxide nanoparticles have been extensively studied for their potential in food packaging, particularly for their ability to combat microbial biofilms. Nanoparticles such as silver oxide, titanium dioxide (TiO2), and zinc oxide (ZnO) offer strong antibacterial properties that help prevent microbial contamination [36]. When integrated into packaging, these nanoparticles release metal ions or generate reactive oxygen species (ROS) upon exposure to moisture or light, effectively inhibiting bacteria, fungi, and other microorganisms. Silver oxide nanoparticles, for instance, release silver ions (Ag+) that interact with microbial cells, disrupting their functions and preventing growth. Similarly, TiO2 nanoparticles generate ROS, such as hydroxyl radicals, which damage microbial cell membranes [20,36].

Another approach to food packaging involves using metal oxide coatings to enhance antibacterial properties. A notable method includes the use of a nano-CuO coating on copper foil (Cu(CuO)), which produces reactive chlorine species (RCS) in situ, suppressing biofilms and killing bacteria on contact. This approach successfully treats bacteria like S. aureus and E. coli by employing heterogeneous Fenton chemistry to generate ROS, damaging bacterial cells. The concentration of H2O2 and Cl– in the environment also influences bacterial growth. Furthermore, the NO2-Cu-Fenton system has shown enhanced performance in eliminating biofilms and killing bacteria, proving particularly effective against E. coli and S. aureus in food and water [37]. Moreover, a blend film consisting of pullulan/collagen/ZnO nanoparticles has been found to be effective against A. niger and has shown potential as an edible food packaging material due to its water solubility [38]. Another antibacterial composite such as PAL@ZnO, created by incorporating natural palygorskite (PAL) nanorods into a chitosan/gelatin (CS/GL) matrix. This material enhances mechanical strength, water resistance, and thermal stability, while effectively combating E. coli and S. aureus [39]. Furthermore, anthocyanins extracted from purple potatoes or roselle were used to modify a chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol/nano-ZnO (CPZ) based film, which displayed strong antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli, while also being capable of monitoring the spoilage status of packaged shrimp through changes in pH caused by microbial spoilage [40]. Additionally, antimicrobial nanocomposites containing ZnO-NPs with gelatin and tragacanth significantly inhibited bacteria such as S. aureus and E. coli, while enhancing the mechanical properties of the packaging [41]. The zinc sulfide nanoparticles (ZnS NPs) also possess antibiofilm activity and, like ZnO NPs, have potential applications in the food industry. Both ZnO and ZnS NPs were equally effective in killing bacteria, with S. aureus being more susceptible compared to P. aeruginosa and Klebsiella oxytoca [42].

Nanocomposite films composed of bovine gelatin and magnetic iron oxide (MIO) nanoparticles (5–20% w/w) have significantly improved mechanical and barrier properties, with optimal performance observed at a 10% concentration. Notably, the 20% MIO nanocomposites exhibited the highest antimicrobial activity against E. coli (7.1 mm) and S. aureus (8.22 mm). These gelatin/MIO films were further evaluated for their potential to extend the shelf life of grapes, underscoring their suitability as biodegradable packaging materials [43]. Liu et al. reported that soluble soybean polysaccharide composite films incorporating 5 wt% nano zinc oxide and 10 wt% tea tree essential oil exhibited enhanced water vapor barrier properties, thermal stability, and UV protection. Although there was no change in tensile strength and elongation, light transmittance at 600 nm decreased from 85.5% to 10.1%. These films demonstrated a DPPH radical scavenging activity of 67.7% and exhibited strong antibacterial effects against E. coli and S. aureus, indicating their promising potential for active packaging applications [44]. Additionally, an active packaging biofilm developed from biodegradable poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) (PBAT), combined with 2% copper oxide nanoparticles (CuO-NPs) and varying amounts of enzymatically prepared nanocellulose fibers, showed enhanced thermal stability, improved mechanical strength, and robust antimicrobial activity against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as unicellular and filamentous fungi [45].

Purohit et al. examined the antimicrobial effects of nanoceria-infused chitosan-based biopolymer films for food packaging, finding significant antimicrobial activity against E. coli and L. monocytogenes, particularly under visible light. This antimicrobial effect is attributed to nanoceria’s ability to alternate between oxidation states (Ce3+ and Ce4+), which enhances its photocatalytic properties [46]. In a related study, Osman et al. explored hydroxypropyl-methyl cellulose (HPMC) films that incorporated Al2O3 and SiO2 nanoparticles (NPs) to target foodborne pathogens such as Bacillus cereus, S. aureus, and S. Typhimurium on chicken fillets. The nanoparticles, approximately 80 nm in size and applied at a concentration of 80 ppm, exhibited substantial antimicrobial efficacy, reducing microbial loads by 2–3 log10 CFU/cm² over 15 days of refrigerated storage [47]. Additionally, Momtaz et al. developed gelatin/chitosan (GEL/CS) nanocomposite films enhanced with nickel oxide nanoparticles (NiO NPs) for active food packaging. The inclusion of optimized concentrations of NiO NPs significantly improved the films’ mechanical, barrier, and thermal properties, with tensile strength increasing from 23.83 MPa (without NPs) to 30.13 MPa with the addition of 1% NiO NPs. These films demonstrated strong antibacterial activity against the Gram-positive bacterium S. aureus compared to the Gram-negative bacterium E. coli. Toxicity assessments further revealed that the films were non-toxic to fibroblast cells, achieving a survival rate exceeding 88% [48].

The development of new materials and coatings continues to push the boundaries of food packaging technology. For example, a photocatalyst called graphitic carbon nitride (g-C3N4) has been studied for its potential to prevent and remove biofilms. Unlike TiO2, which requires ultraviolet light, g-C3N4 harnesses visible light. When exposed to white LEDs, it effectively disrupts biofilm formation, progressing from the surface to the core, facilitated by ROS diffusion [20].

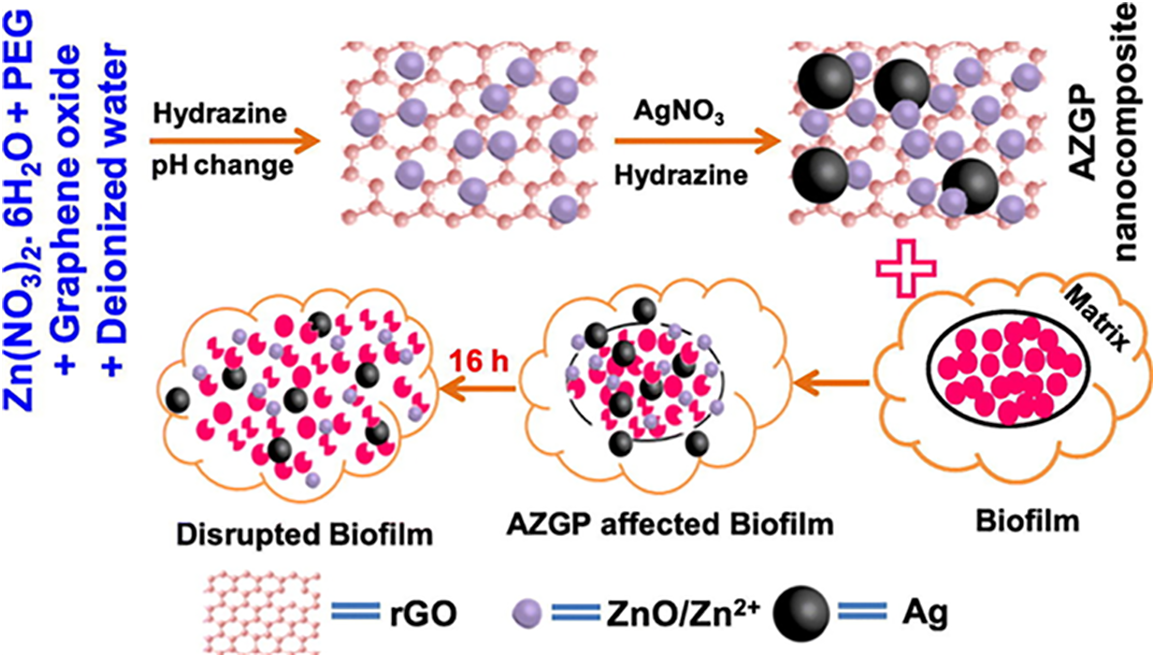

Another study explored silver-graphene-TiO2 nanocomposites for controlling the growth of Campylobacter jejuni. These nanocomposites induced leakage of proteins and DNA from bacterial cells, reduced bacterial motility and hydrophobicity, and significantly inhibited biofilm formation. Importantly, these synthesized nanoparticles were confirmed as non-cytotoxic to human cells [49]. According to the research findings, Similarly, nanocomposites combining silver, ZnO, reduced graphene oxide (rGO), and polyethylene glycol (PEG) showed robust anti-biofilm activity. the biofilm formation of Saureus and P. aeruginosa bacteria was robustly inhibited due to the pronounced anti-biofilm effects of AZGP nanocomposites. The AZGP nanocomposite, containing 0.05 M silver nitrate and a dosage of 31.25 μg/mL, inhibited around 95% of biofilm formation while maintaining antimicrobial activity for up to 90 days (Fig. 2) [50].

Figure 2: Illustration of the production process of silver-incorporated ZnO-rGO-PEG (AZGP) nanocomposite [50]

Silica nanoparticles (SNPs), a type of metal oxide nanoparticle, are effective in mitigating biofilms due to their high surface-to-volume ratio, which enhances interactions with microbial cells and biofilm matrices. In food packaging, SNPs can prevent microbial attachment and growth, disrupt biofilm structures, and exhibit antimicrobial activity by damaging microbial cell membranes, inhibiting biofilm formation [34].

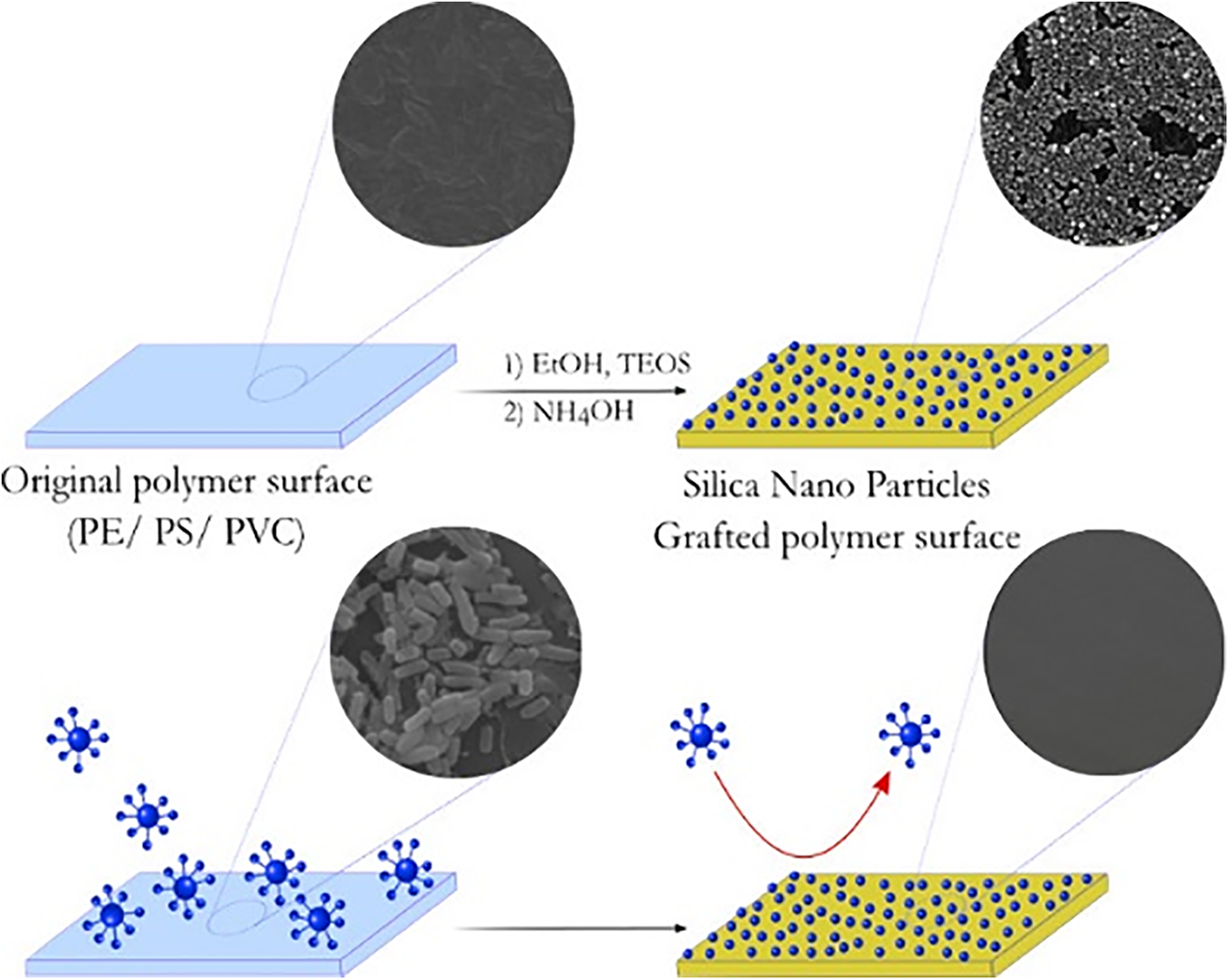

One promising application involves SNPs encapsulating basil oil, incorporated into chitosan films. These basil oil@SiNPs films demonstrated antimicrobial inhibition against both Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, as well as pathogenic yeast. While they increased the water contact angle and activation energy, they decreased water vapor permeability but increased oxygen permeability [51]. SNPs are also utilized as delivery platforms for biocidal agents in anti-biofilm research. When grafted onto polyethylene, polystyrene, and polyvinyl chloride surfaces, SNPs increased surface nanoroughness while maintaining mechanical properties. These grafted surfaces significantly reduced the adhesion of Gram-positive B. licheniformis or Gram-negative bacteria P. aeruginosa. This method offers a durable anti-biofouling solution for biomedical devices, food, water treatment systems, and industrial applications (Fig. 3) [34].

Figure 3: Illustration depicting the incorporation of biocidal agents on nanosilica into anti-biofouling polymers [34]

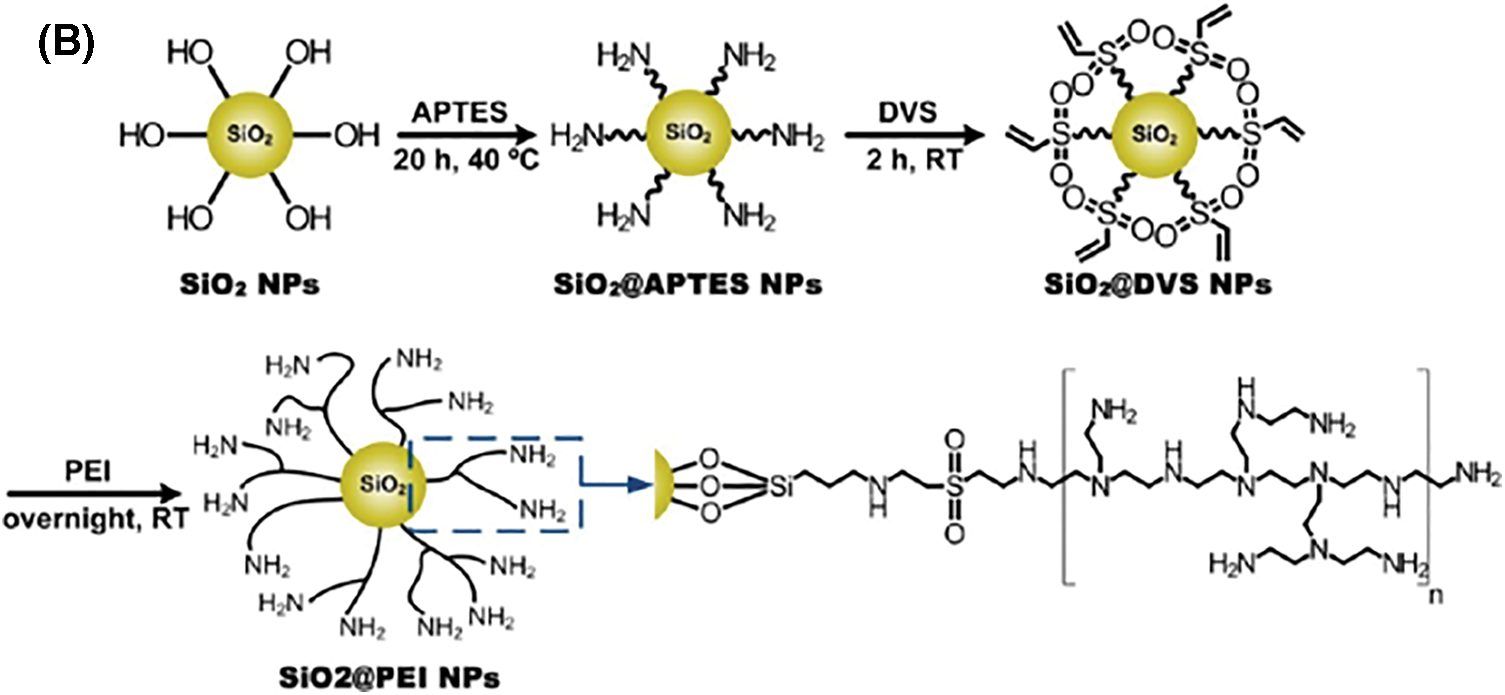

Moreover, a study demonstrated that stainless-steel surfaces coated with silica nanoparticles (SNPs) modified with polyethyleneimine (PEI) and polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) nanoparticles in an electroless nickel coating exhibited antimicrobial and nonfouling properties. These coatings reduced L. monocytogenes populations by over 5 log and decreased biofilm formation by more than 2 log. The coatings also inhibited exopolysaccharide production, lowering the risk of cross-contamination, nosocomial infections, and foodborne diseases (Fig. 4) [52]. Some recent studies outlined the application of various metal oxides conjugated films to mitigate microbial biofilm, as presented in Table 3.

Figure 4: Illustration depicting the bactericidal properties of Ni-PTFE-SiNP +-modified coatings (A) and the synthesis process of SiO2@PEI NPs (B) [52]

2.1.4 Biopolymeric Nanomaterials against Biofilm

Food packaging materials must meet specific criteria, with antimicrobial and antibiofilm packaging gaining importance. Eco-friendly, bio-derived polymers are increasingly replacing petroleum-based products. These biobased polymers include natural polymers (cellulose, chitin), synthetic polymers (polyhydroxy alkanoates [PHA], poly(glycolic acid) [PGA]), and biobased nanocomposites, which combine a biopolymer matrix with nanoparticles for enhanced antimicrobial properties [54,55]. Nanoparticles made from biopolymers and biosurfactants have also gained interest as they can be produced without harmful chemicals [9]. These materials are used in films, coatings, and emulsions, serving as active components to maintain food quality and safety [56,57]. Exopolysaccharides (EPS), polyhydroxy alkanoates (PHA), polylactic acid (PLA), starch, lignin, and protein-based polymers like collagen, gelatin, and gluten are currently under scrutiny for their potential as food packaging agents [58].

The effectiveness of various natural antimicrobial chemicals, such as citric acid, curcumin, calcium lactate, erythorbic acid, hop extract, garlic extract, and nisin, has been evaluated as food additives and in packaging materials. These agents were tested for their antibacterial and anti-biofilm properties against bacteria such as L. monocytogenes, S. aureus, and E. coli. It was found that garlic extract, erythorbic acid, and citric acid were the most effective in inhibiting bacteria. Moreover, combining two additives resulted in better efficacy, and mixtures of all these showed higher efficiency in inhibiting bacteria [59]. PEG-decorated GO Nanosheets have been demonstrated to enhance the efficiency of chitosan biopolymer, providing better thermal and mechanical stability as well as antibacterial properties [60]. Chitosan nanoparticles (CNPs) have also shown promise in preventing biofilm formation. CNPs at a concentration of 1500 μg/mL effectively suppressed biofilm formation by P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and C. albicans by 91.83%, 55.47%, and 66.4%, respectively [61].

A recent study demonstrated the effectiveness of poly-L-aspartic acid nanoparticles with essential oil in combating S. aureus biofilm contamination on food-contact surfaces. This approach shows promise for applications in the food industry. The study confirmed the effectiveness of PASP in damaging S. aureus biofilms by impacting metabolic activity, bacterial adhesion, and extracellular polymeric substances. PASP was particularly effective in reducing the production of extracellular DNA (eDNA) by 49.4%. Additionally, nanoparticles containing essential oil (EO@PASP/HACCNPs) exhibited enhanced permeation and dispersion effects on biofilms, resulting in long-lasting anti-biofilm activity. When tested on a 72-h-old biofilm, EO@PASP/HACCNPs reduced the population of S. aureus by 0.63 log CFU/mL compared to the use of EO alone [62].

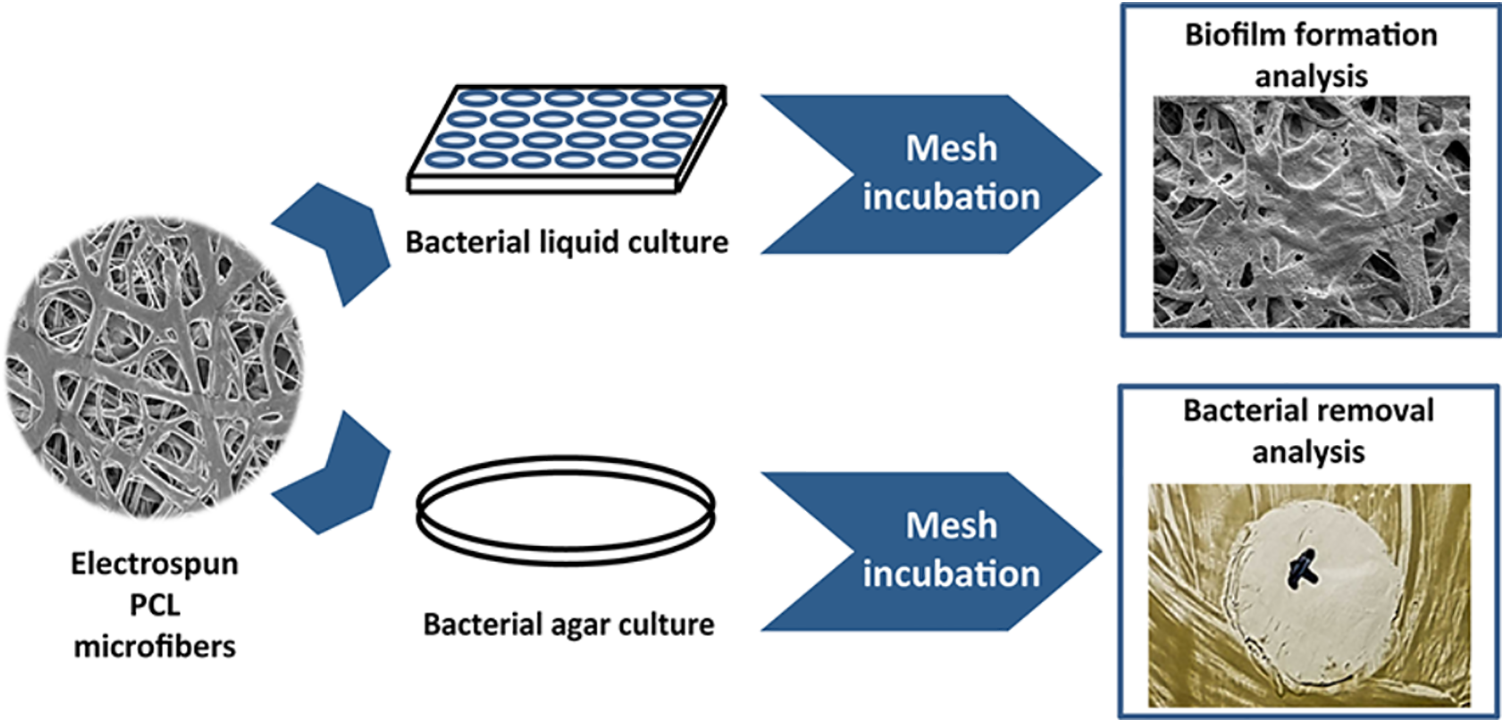

The use of nanocomposites in food packaging can help prevent the formation of biofilms on food. These nanocomposite biofilms are also useful in managing plastic waste and combating infectious diseases. For instance, Reference [22] demonstrated that electrospun fiber-based biofilms can act as a barrier against infectious microorganisms. By incorporating polylactic acid microfibers with active agents, nanocomposite biofilms with antimicrobial properties can be developed. The study revealed that acetylated cellulose nanofibers, with diameters of about 83 nm, and microfibrillar structures with diameters ranging from 1.7 to 2.4 µm, exhibited favorable characteristics for this purpose. Moreover, these nanocomposite biofilms demonstrated antibacterial activity against S. typhimurium and S. aureus [22]. In another study by Sun et al. it was found that starch-lignin nanoparticles composite films exhibited impressive tensile strength and elastic modulus, surpassing pure starch film. Additionally, lignin nanoparticles improved the thermal stability of the composite films and enhanced UV protection, reduced oxygen permeation, and scavenged DPPH free radicals, thus delaying the oxidation of soybean oil. Furthermore, bionanocomposites can effectively trap antimicrobial bioactive compounds [63]. Bionanocomposites are capable of trapping antimicrobial bioactive compounds which is a significant advantage. In a study by Cacciatore et al., it was demonstrated that carvacrol encapsulated into nanoliposomes and polymeric Eudragit® nanocapsules significantly reduced the presence of bacteria such as S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, E. coli, and Salmonella spp. on stainless steel surfaces. The encapsulated carvacrol displayed regulated release and a subdued scent, making it a desirable option for food applications [64]. The application of electrospun biodegradable polymers in biomedical and food industries was explored by Rumbo et al. as well. Their study revealed that electrospun polycaprolactone (PCL) microfibrous mesh could become colonized by pathogenic bacteria. However, it was suggested that functionalizing PCL meshes with antimicrobial compounds can make them effective food packaging materials, preventing bacterial adherence and biofilm development (Fig. 5) [65].

Figure 5: Schematic illustration of colonization of pathogenic bacterial strains on electrospun polycaprolactone fibres [65]

The research conducted by [66] revealed that composite films made of ethyl cellulose and polydimethylsiloxane, and containing small amounts of clove essential oil, exhibited antibacterial properties against E. coli, S. aureus, and P. aeruginosa. The clove essential oil was found to enhance the hydrophobicity of the composite material, which comprised 20 wt% PDMS and 80 wt% ethyl cellulose. According to the study, the presence of clove essential oil on the composites seemed to inhibit the growth of biofilms [66]. Additionally, Reference [9] developed antibacterial nanoparticles by combining chitosan with the biosurfactant rhamnolipid. The addition of rhamnolipid reduced the size and polydispersity index of chitosan nanoparticles, leading to a higher positive surface charge and increased stability of chitosan/rhamnolipid nanoparticles (C/RL-NPs). These nanoparticles demonstrated antimicrobial activity against both planktonic bacteria and biofilms of Staphylococcus strains. Furthermore, moderate concentrations of NPs effectively eliminated both S. aureus and Staphylococcus epidermidis biofilms (Fig. 6) [9].

Figure 6: Schematic representation of rhamnolipid and chitosan nanoparticles and their antimicrobial properties [9]

Antimicrobial packaging incorporates antimicrobial compounds into the packaging material to inhibit the growth of microorganisms [67]. This type of packaging not only helps prevent foodborne epidemics but also extends the shelf life and maintains the quality of food products. Starch-based materials, like chitosan, are commonly used as antibacterial agents against various microbes, and chitosan has been effectively applied as an edible coating with strong antibacterial properties [68]. Bio-nanocomposite materials, including chitosan and starch, play a critical role in food packaging due to their superior barrier qualities, which enhance food stability [17]. Starch is the most widely used biopolymer for food packaging. Various antimicrobial additives, such as tea tree essential oil, cinnamon essential oil, cassava starch, cellulose nanofibrils, neem, oregano, lemongrass essential oil, rosemary extract, and pomegranate peel powder, are being evaluated in combination with starch-based biopolymers as antimicrobial additives [69,70]. Furthermore, a modified antimicrobial peptide (1018K6) was bioconjugated to polyethylene terephthalate, demonstrating antibacterial and anti-biofilm capabilities against foodborne pathogens such as L. monocytogenes [71].

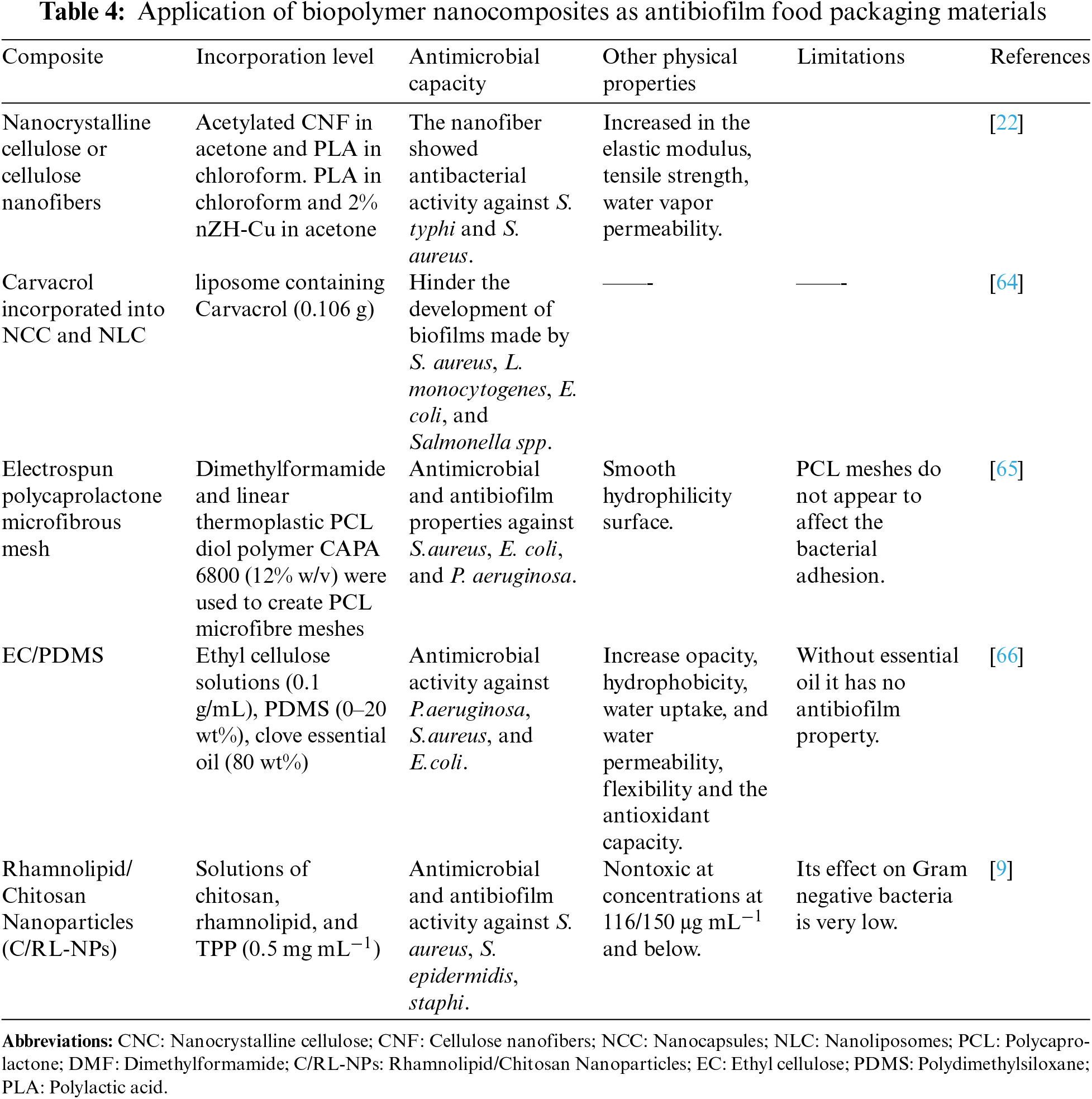

Microbial biofilm is a major concern in the food industry as it can be formed by several pathogens such as E. coli, S. enterica, Yersinia enterocolitica, C. jejuni, S. aureus, L. monocytogenes, and E. coli O157:H7 [72] These biofilms provide various advantages to the microorganisms, including forming a physical barrier against desiccation, mechanical resistance against liquid streams in food industries, and resistance to antimicrobial agents. Several methods, such as ultrasound, ultraviolet rays, magnetic fields, as well as the application of different chemicals and inhibitors, can disrupt biofilm formation and growth [73]. Studies have shown that incorporating phytochemicals like eugenol and thymol into packaging materials made of poly(lactic acid), poly(butylene succinate), and PBAT improves their antimicrobial properties against food-related pathogens like B. cereus and S. aureus [74]. Additionally, grafting CNPs with eugenol and carvacrol enhances their antimicrobial properties against E. coli and S. aureus [75]. An edible coating of nano-emulsion using carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and cardamom essential oil (CEO) was found to be effective against E. coli and L. monocytogenes. This coating material was also found to reduce the loss of fruit (tomato) weight significantly by maintaining firmness and reducing oxidative stress [76]. Furthermore, the use of food additives to inhibit biofilm formation on food can be a promising solution. Sodium citrate and cinnamic aldehyde have been reported to prevent the growth of biofilms of S. aureus, E. coli, and P. fluorescens. Methyl eugenol has been found to inhibit biofilm development by Gram-negative bacteria [77]. In previous research, efforts have been made to produce various biofilm-controlling packaging materials, especially through nanoparticle approaches such as metal oxide nanoparticles and AgNPs, silica composite materials, and biopolymer-based packaging films, to enhance their pharmacological properties and antimicrobial activity. The use of biopolymer-conjugated nanocomposites to combat the biofilm of various microorganisms is presented in Table 4.

3 Conclusion and Future Aspects

The food industry is searching for new food packaging films to prevent the growth of harmful microorganisms. It is easier to stop the initial stages of biofilm formation than to remove an established biofilm. ZnO and TiO2 are the most commonly used metal oxide nanoparticles in active food packaging due to their antibiofilm properties. However, there are concerns about these nanoparticles migrating from the packaging into the food, which can be harmful to human health. Despite these concerns, studies have shown that incorporating certain nanoparticles can prevent biofilm formation and improve the properties of food packaging. Green synthesis methods can help make synthesized nanoparticles safer and more compatible with living tissues. Biopolymeric nanomaterials are thus creating ripples in the food packaging industry due to their compatibility with living tissues and ability to degrade naturally. By encapsulating and releasing antimicrobial agents in a controlled manner, biopolymeric nanomaterials can provide long-lasting protection against biofilm formation on food packaging surfaces. Additionally, combining biopolymers with other nanoparticles can create matrices for bioactive protection and controlled delivery. These aspects not only put forth biopolymeric nanocomposites ahead of the other types of nanomaterials but also emphasizes on the fact that biopolymeric nanocomposites rightly match all the criteria for serving as long term food preservation materials. We hope that the present review justifies the reasons for the growing popularity of this category of antibiofilm food packaging materials and will foster future research in these lines. However, rigorous testing of these coating surfaces are required to ensure their effectiveness and safety for food packaging. Nanotechnology can also integrate sensors and smart tags into food packaging to monitor parameters like temperature and humidity, ensuring food safety and quality control throughout the supply chain.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: All authors, including Bandana Padhan, Priyanka Bhowmik, Ananya Roy, Madhumita Patel and Joyjyoti Das contributed to the writing of the original draft of the manuscript. In addition, Bandana Padhan and Rajkumar Patel were involved in the conceptualization of the manuscript. Madhumita Patel, Rajkumar Patel, Joyjyoti Das and Yong Yu participated in the review and editing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Calva-Estrada SJ, Jimenez-Fernandez M, Vallejo-Cardona AA, Castillo-Herrera GA, Lugo-Cervantes EC. Cocoa nanoparticles to improve the physicochemical and functional properties of whey protein-based films to extend the shelf life of muffins. Foods. 2021;10:2672. doi:10.3390/foods10112672. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Nunes JC, Melo PTS, Lorevice MV, Aouada FA, de Moura MR. Effect of green tea extract on gelatin-based films incorporated with lemon essential oil. J Food Sci Technol. 2021;58:1–8. doi:10.1007/s13197-020-04469-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Asgher M, Qamar SA, Bilal M, Iqbal HMN. Bio-based active food packaging materials: sustainable alternative to conventional petrochemical-based packaging materials. Food Res Int. 2020;137:109625. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109625. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Azizi-Lalabadi M, Alizadeh-Sani M, Divband B, Ehsani A, McClements DJ. Nanocomposite films consisting of functional nanoparticles (TiO2 and ZnO) embedded in 4A-Zeolite and mixed polymer matrices (gelatin and polyvinyl alcohol). Food Res Int. 2020;137:109716. doi:10.1016/j.foodres.2020.109716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Saranti TFDS, Melo PTS, Cerqueira MA, Aouada FA, de Moura MR. Performance of gelatin films reinforced with cloisite Na+ and black pepper essential oil loaded nanoemulsion. Polymers. 2021;13:4298. doi:10.3390/polym13244298. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Misra T, Tare M, Jha PN. Insights into the dynamics and composition of biofilm formed by environmental isolate of Enterobacter cloacae. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1114. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2022.877060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Ramić D, Ogrizek J, Bucar F, Jeršek B, Jeršek M, Možina SS. Campylobacter jejuni biofilm control with lavandin essential oils and by-products. Antibiotics. 2022;11:854. doi:10.3390/antibiotics11070854. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Xu JG, Hu HX, Chen JY, Xue YS, Kodirkhonov B, Han BZ. Comparative study on inhibitory effects of ferulic acid and p-coumaric acid on Salmonella Enteritidis biofilm formation. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2022;38:136. doi:10.1007/s11274-022-03317-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Marangon CA, Martins VCA, Ling MH, Melo CC, Plepis AMG, Meyer RL, et al. Combination of rhamnolipid and chitosan in nanoparticles boosts their antimicrobial efficacy. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12:5488–99. doi:10.1021/acsami.9b19253. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Basavegowda N, Baek KH. Synergistic antioxidant and antibacterial advantages of essential oils for food packaging applications. Biomolecules. 2021;11:1267. doi:10.3390/biom11091267. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Dash P, Rana K, Turuk J, Palo SK, Pati S. Antimicrobial resistance and biofilm formation of Staphylococcus aureus isolates from febrile cases: findings from a rural cohort of Odisha, India. Pol J Microbiol. 2023;72:209–14. doi:10.33073/pjm-2023-005. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Nikolic MV, Vasiljevic ZZ, Auger S, Vidic J. Metal oxide nanoparticles for safe active and intelligent food packaging. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2021;116:655–68. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.08.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Qi R, Cui Y, Liu J, Wang X, Yuan H. Recent advances of composite nanomaterials for antibiofilm application. Nanomaterials. 2023;13:2725. doi:10.3390/nano13192725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Jamwal V, Mittal A. Recent progresses in nanocomposite films for food-packaging applications: synthesis strategies, technological advancements, potential risks and challenges. Food Rev Int. 2024;40(10):3634–65. doi:10.1080/87559129.2024.2368065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Mishra B, Panda J, Mishra AK, Nath PC, Nayak PK, Mahapatra U, et al. Recent advances in sustainable biopolymer-based nanocomposites for smart food packaging: a review. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;279:135583. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.135583. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Brandelli A. Nanocomposites and their application in antimicrobial packaging. Front Chem. 2024;12:1356304. doi:10.3389/fchem.2024.1356304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang X, Liu J, Yong H, Qin Y, Liu J, Jin C. Development of antioxidant and antimicrobial packaging films based on chitosan and mangosteen (Garcinia mangostana L.) rind powder. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;145:1129–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.10.038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Liu X, Yao H, Zhao X, Ge C. Biofilm formation and control of foodborne pathogenic bacteria. Molecules. 2023;28:2432. doi:10.3390/molecules28062432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Al-Wrafy FA, Al-Gheethi AA, Ponnusamy SK, Noman EA, Fattah SA. Nanoparticles approach to eradicate bacterial biofilm-related infections: a critical review. Chemosphere. 2022;288:132603. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2021.132603. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Shen H, López-Guerra EA, Zhu R, Diba T, Zheng Q, Solares SD, et al. Visible-light-responsive photocatalyst of graphitic car-bon nitride for pathogenic biofilm control. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2019;11:373–84. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b18543. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Ullah A, Mirani ZA, Binbin S, Wang F, Chan MWH, Aslam S, et al. An elucidative study of the anti-biofilm effect of selenium na-noparticles (SeNPs) on selected biofilm producing pathogenic bacteria: a disintegrating effect of SeNPs on bacteria. Process Biochem. 2023;126:98–107. doi:10.1016/j.procbio.2022.12.031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Vergara-Figueroa J, Alejandro-Martin S, Cerda-Leal F, Gacitúa W. Dual electrospinning of a nanocom-posites biofilm: potential use as an antimicrobial barrier. Mater Today Commun. 2020;25:101671. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Chlumsky O, Purkrtova S, Michova Turonova H, Svarcova Fuchsova V, Slepicka P, Fajstavr D, et al. The effect of gold and silver nanoparticles, chitosan and their combinations on bacterial biofilms of food-borne pathogens. Biofouling. 2020;36:222–33. doi:10.1080/08927014.2020.1751132. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Torqueti FT, Freitas GL, Ferreira DC, Gelamo RV, dos Anjos Gonçalves LD, Naves EAA. Stainless steel surface functionalized with silver by cathodic sputtering. J Food Safety. 2019;39(5):4000. doi:10.1111/jfs.12668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Fontecha-Umaña F, Ríos-Castillo AG, Ripolles-Avila C, Rodríguez-Jerez JJ. Antimicrobial activity and preven-tion of bacterial biofilm formation of silver and zinc oxide nanoparticle-containing polyester surfaces at various concentrations for use. Foods. 2020;9(4):442. doi:10.3390/foods9040442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Nwabor OF, Singh S, Wunnoo S, Lerwittayanon K, Voravuthikunchai SP. Facile deposition of biogenic silver nanoparticles on po-rous alumina discs, an efficient antimicrobial, antibiofilm, and antifouling strategy for functional contact surfaces. Biofouling. 2021;37:538–54. doi:10.1080/08927014.2021.1934457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Griffith A, Neethirajan S, Warriner K. Development and evaluation of silver zeolite antifouling coatings on stainless steel for food contact surfaces. J Food Saf. 2015;35:345–54. doi:10.1111/jfs.2015.35.issue-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Manso S, Wrona M, Salafranca J, Nerín C, Alfonso MJ, Caballero MÁ. Evaluation of new antimicrobial materials incorporating ethyl lauroyl arginate or silver into different matrices, and their safety in use as potential packaging. Polymers. 2021;13:1–12. [Google Scholar]

29. Ferreira FV, Mariano M, Pinheiro IF, Cazalini EM, Souza DH, Lepesqueur LS, et al. Cellulose nanocrystal-based poly(butylene adipate-co-terephthalate) nanocomposites covered with antimicrobial silver thin films. Polym Eng Sci. 2019;59:E356–65. [Google Scholar]

30. Ferreira TPM, Nepomuceno NC, Medeiros ELG, Medeiros ES, Sampaio FC, Oliveira JE, et al. Antimicrobial coatings based on poly(dimethyl siloxane) and silver nanoparticles by solution blow spraying. Prog Org Coat. 2019;133:19–26. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2019.04.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Zhang J, Zhang J, Wang B, Li W, Wang H, Guo R, et al. Modified magnesium oxide/silver nanoparticles reinforced poly (butylene succinate-co-terephthalate) composite biofilms for food packaging application. Food Chem. 2024;435(2):137492. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2023.137492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Kukushkina EA, Duarte AC, Tartaro G, Sportelli MC, Di Franco C, Fernández L, et al. Self-standing bioinspired polymer films doped with ultrafine silver nanoparticles as innovative antimicrobial material. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(24):15818. doi:10.3390/ijms232415818. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Fialho JFJúnior, Naves EA, Bernardes PC, Ferreira DC, Dos Anjos LD, Gelamo RV, et al. Stainless steel and polyethylene surfaces functional-ized with silver nanoparticles. Food Sci Technol Int. 2018;24(1):87–94. doi:10.1177/1082013217731414. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Boguslavsky Y, Shemesh M, Friedlander A, Rutenberg R, Filossof AM, Buslovich A, et al. Eliminating the need for biocidal agents in anti-biofouling polymers by applying grafted nanosilica instead. ACS Omega. 2018;3(10):12437–45. doi:10.1021/acsomega.8b01438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Khiralla GM, El-Deeb BA. Antimicrobial and antibiofilm effects of selenium nanoparticles on some foodborne pathogens. LWT—Food Sci Technol. 2015;63(2):1001–7. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2015.03.086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Khan ST, Al-Khedhairy AA, Musarrat J. ZnO and TiO2 nanoparticles as novel antimicrobial agents for oral hygiene: a review. J Nanopart Res. 2015;17(6):5721. doi:10.1007/s11051-015-3074-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang L, Peng R, Liu X, Heng C, Miao Y, Wang W, et al. Nitrite-enhanced copper-based Fenton reactions for biofilm removal. Chem Commun. 2021;57:5514–7. doi:10.1039/D1CC00374G. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Bailore NN, Balladka SK, Doddapaneni SJ, Mudiyaru MS. Fabrication of environmentally compatible biopolymer films of pullulan/piscean collagen/ZnO nanocomposite and their antifungal activity. J Polym Environ. 2021;29:1192–201. doi:10.1007/s10924-020-01953-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ding J, Hui A, Wang W, Yang F, Kang Y, Wang A. Multifunctional palygorskite@ZnO nanorods enhance simultane-ously mechanical strength and antibacterial properties of chitosan-based film. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;189:668–77. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.08.107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Liu J, Huang J, Ying Y, Hu L, Hu Y. pH-sensitive and antibacterial films developed by incorporating an-thocyanins extracted from purple potato or roselle into chitosan/polyvinyl alcohol/nano-ZnO matrix: comparative study. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;178:104–12. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Shahvalizadeh R, Ahmadi R, Davandeh I, Pezeshki A, Seyed Moslemi SA, Karimi S, et al. Antimicrobial bio-nanocomposite films based on gelatin, tragacanth, and zinc oxide nanoparticles—Microstructural, mechanical, thermo-physical, and barrier properties. Food Chem. 2021;354(1):129492. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.129492. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Bianchini Fulindi R, Domingues Rodrigues J, Lemos Barbosa TW, Goncalves Garcia AD, de Almeida La Porta F, Pratavieira S, et al. Zinc-based nanoparticles reduce bacterial biofilm formation. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11(2):e04831–22. doi:10.1128/spectrum.04831-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Mehmood Z, Sadiq MB, Khan MR. Gelatin nanocomposite films incorporated with magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles for shelf life extension of grapes. J Food Saf. 2020;40(4):e12814. doi:10.1111/jfs.12814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Liu J, Wang Y, Liu Y, Shao S, Zheng X, Tang K. Synergistic effect of nano zinc oxide and tea tree essential oil on the properties of soluble soybean polysaccharide films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;239(2022):124361. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Hasanin MS, Youssef AM. Ecofriendly bioactive film doped CuO nanoparticles based biopolymers and reinforced by enzymatically modified nanocellulose fibers for active packaging applications. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2022;34(6):100979. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Purohit SD, Priyadarshi R, Bhaskar R, Han SS. Chitosan-based multifunctional films reinforced with cerium oxide nanoparticles for food packaging applications. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;143:108910. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2023.108910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Osman AG, El-Desouky AI, Morsy MK, Aboud AA, Mohamed MH. Impact of aluminum oxide and silica oxide nanocomposite on foodborne pathogens in chicken fillets. Eur J Nutr Food Saf. 2019;9(2):152–62. doi:10.9734/EJNFS/2019/v9i230054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Momtaz M, Momtaz E, Mehrgardi MA, Momtaz F, Narimani T, Poursina F. Preparation and characterization of gelatin/chitosan nanocomposite reinforced by NiO nanoparticles as an active food packaging. Sci Rep. 2024;14:519. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-50260-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Noreen Z, Khalid NR, Abbasi R, Javed S, Ahmad I, Bokhari H. Visible light sensitive Ag/TiO2/graphene composite as a potential coating material for control of Campylobacter jejuni. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2019;98:125–33. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2018.12.087. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Naskar A, Khan H, Sarkar R, Kumar S, Halder D, Jana S. Anti-biofilm activity and food packaging application of room temperature solution process based polyethylene glycol capped Ag-ZnO-graphene nanocomposite. Mater Sci Eng C Mater Biol Appl. 2018;91:743–53. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2018.06.009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Sultan M, Abdelhakim AA, Nassar M, Hassan YR. Active packaging of chitosan film modified with basil oil encapsulated in silica nanoparticles as an alternate for plastic packaging materials. Food Biosci. 2023;51:102298. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2022.102298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Huang K, Chen J, Nugen SR, Goddard JM. Hybrid antifouling and antimicrobial coatings prepared by electroless co-deposition of fluoropolymer and cationic silica nanoparticles on stainless steel: efficacy against Listeria monocytogenes. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:15926–36. doi:10.1021/acsami.6b04187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Wang W, Peng R, Liu J, Wang Z, Guo T, Liang Q, et al. Biofilm eradication by in situ generation of reactive chlorine species on nano-CuO surfaces. J Mater Sci. 2020;55:11609–21. doi:10.1007/s10853-020-04853-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Abedi-Firoozjah R, Yousefi S, Heydari M, Seyedfatehi F, Jafarzadeh S, Mohammadi R, et al. Application of red cabbage anthocyanins as pH-sensitive pigments in smart food packaging and sensors. Polymers. 2022;14:1629. doi:10.3390/polym14081629. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Rhim J-W, Park H-M, Ha C-S. Bio-nanocomposites for food packaging applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2013;38:1629–52. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2013.05.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Agrillo B, Balestrieri M, Gogliettino M, Palmieri G, Moretta R, Proroga YTR, et al. Functionalized polymeric materials with bio-derived antimicrobial peptides for active packaging. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(3):601. doi:10.3390/ijms20030601. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Boonsiriwit A, Itkor P, Sirieawphikul C, Lee YS. Characterization of natural anthocyanin indicator based on cellulose bio-composite film for monitoring the freshness of chicken tenderloin. Molecules. 2022;27:2752. doi:10.3390/molecules27092752. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Zhou F, Wang D, Zhang J, Li J, Lai D, Lin S, et al. Preparation and characterization of biodegradable κ-carrageenan based anti-bacterial film functionalized with wells-dawson polyoxometalate. Foods. 2022;11:586. doi:10.3390/foods11040586. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Lencova S, Zdenkova K, Demnerova K, Stiborova H. Short communication: antibacterial and antibiofilm effect of natural substances and their mixtures over Listeria monocytogenes, Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. LWT. 2022;154:112777. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2021.112777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Mohammadi S, Babaei A, Arab-Bafrani Z. Polyethylene glycol-decorated GO nanosheets as a well-organized nanohybrid to enhance the performance of chitosan biopolymer. J Polym Environ. 2022;30:5130–47. doi:10.1007/s10924-022-02577-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. El-Naggar NE, Eltarahony M, Hafez EE, Bashir SI. Green fabrication of chitosan nanoparticles using Lavendula angustifolia, optimization, characterization and in-vitro antibiofilm activity. Sci Rep. 2023;13:11127. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-37660-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lin L, Zhang P, Chen X, Hu W, Abdel-Samie MA, Li C, et al. Inhibition of Staphylococcus aureus biofilms by poly-L-aspartic acid nanoparticles loaded with Litsea cubeba essential oil. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;242:124904. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2023.124904. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Sun X, Li Q, Wu H, Zhou Z, Feng S, Deng P, et al. Sustainable starch/lignin nanoparticle composites biofilms for food packaging applications. Polymers. 2023;15:1959. doi:10.3390/polym15081959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Cacciatore AF, Dalmás M, Maders C, Ataíde Isaía H, Brandelli A, da Silva Malheiros P. Carvacrol encapsulation into nanostructures: characterization and antimicrobial activity against foodborne pathogens adhered to stainless steel. Food Res Int. 2020;133:109143. [Google Scholar]

65. Rumbo C, Tamayo-Ramos JA, Caso MF, Rinaldi A, Romero-Santacreu L, Quesada R, et al. Colonization of electrospun polycaprolactone fibers by relevant pathogenic bacterial strains. ACS Appl Mater Inter. 2018;10:11467–73. doi:10.1021/acsami.7b19440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Heredia-Guerrero JA, Ceseracciu L, Guzman-Puyol S, Paul UC, Alfaro-Pulido A, Grande C, et al. Antimicrobial, antioxidant, and waterproof RTV silicone-ethyl cellulose composites containing clove essential oil. Carb Polymers. 2018;192:150–8. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.03.050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

67. Munteanu BS, Vasile C. Encapsulation of natural bioactive compounds by electrospinning—Applications in food storage and safety. Polymers. 2021;13:3771. doi:10.3390/polym13213771. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Zareie Z, Tabatabaei Yazdi F, Mortazavi SA. Development and characterization of antioxidant and antimicrobial edible films based on chitosan and gamma-aminobutyric acid-rich fermented soy protein. Carb Polymers. 2020;244:116491. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116491. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Hasan M, Rusman R, Khaldun I, Ardana L, Mudatsir M, Fansuri H. Active edible sugar palm starch-chitosan films carrying extra virgin olive oil: barrier, thermo-mechanical, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties. Int J Bio Macromol. 2020;163:766–75. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.07.076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Pirnia M, Shirani K, Tabatabaee Yazdi F, Moratazavi SA, Mohebbi M. Characterization of antioxidant active biopolymer bilayer film based on gelatin-frankincense incorporated with ascorbic acid and Hyssopus officinalis essential oil. Food Chem. 2022;14:100300. [Google Scholar]

71. Tien ND, Lyngstadaas SP, Mano JF, Blaker JJ, Haugen HJ. Recent developments in chitosan-based micro/nanofibers for sustainable food packaging, smart textiles, cosmeceuticals, and biomedical applications. Molecules. 2021;26:2683. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

72. Agostinho Davanzo EF, Dos Santos RL, Castro VHL, Palma JM, Pribul BR, Dallago BSL, et al. Molecular characterization of Salmonella spp. and Listeria monocytogenes strains from biofilms in cattle and poultry slaughterhouses located in the federal District and State of Goiás, Brazil. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0259687. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0259687. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

73. Lu J, Hu X, Ren L. Biofilm control strategies in food industry: inhibition and utilization. Trends Food Sci Tech. 2022;123:103–13. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2022.03.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Ramos M, Fortunati E, Beltrán A, Peltzer M, Cristofaro F, Visai L, et al. Controlled release, disintegration, antioxidant, and antimicrobial properties of poly(lactic acid)/thymol/nanoclay composites. Polymers. 2020;12:1878. doi:10.3390/polym12091878. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

75. Zhao D, Zhang R, Liu X, Li X, Xu M, Huang X, et al. Screening of chitosan derivatives-carbon dots based on antibacterial activity and application in Anti-Staphylococcus aureus biofilm. Int J Nanomed. 2022;17:937–52. doi:10.2147/IJN.S350739. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Das SK, Vishakha K, Das S, Chakraborty D, Ganguli A. Carboxymethyl cellulose and cardamom oil in a nanoemulsion edible coating inhibit the growth of foodborne pathogens and extend the shelf life of tomatoes. Biocat Agri Biotech. 2022;42:102369. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2022.102369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Liu L, Ye C, Soteyome T, Zhao X, Xia J, Xu W, et al. Inhibitory effects of two types of food additives on biofilm formation by foodborne pathogens. Microbiology. 2019;8(9):e00853. doi:10.1002/mbo3.853. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools