Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Self-Assembled Hollow Microporous Organic Polymers Embedded in Polymer Fibers for Advanced Food Preservation

Department of Materials and Chemistry, University of Shanghai for Science and Technology, Shanghai, 200093, China

* Corresponding Authors: Deng-Guang Yu. Email: ; Wenliang Song. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(2), 435-448. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.064290

Received 11 February 2025; Accepted 16 May 2025; Issue published 14 July 2025

Abstract

Porous organic polymers are remarkably versatile materials with porous and carefully designed structures. They complement traditional preservation methods by overcoming their limitations and significantly extending the shelf life of preserved products. Notably, porous hollow nanospheres (PHNs), with their unique hollow structures capable of adsorbing and releasing organic molecules, have garnered considerable attention in food preservation. However, most PHNs are challenging to synthesize in one step, and PHNs are usually in powder form, which makes it challenging to apply them directly. In this study, we successfully synthesized PHNs in one step using the Friedel–Crafts reaction. The PHNs, adsorbed with hexanal molecules, were then embedded in polymer fibers to create composites via electrospinning. The preservation effect of the composite nanofiber membranes was investigated by determining the changes in appearance, weight, peel hardness, and pulp sugar content of three fruits, namely strawberries, bananas, and kumquats, after several days of storage. In comparison to pure poly(ε-caprolactone) fiber membranes, PHNs containing hexanal molecules slowed down the oxidative deterioration process and enhanced the quality and flavor of preserved fruits. This research presents innovative approaches for using porous organic polymers in food preservation and serves as a valuable reference for the development of future food packaging materials.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Food is a fundamental necessity, and ensuring food safety must be a top priority. In recent decades, with rising living standards, people have shifted their focus from merely having enough food to emphasizing food safety [1,2]. Food preservation plays a crucial role in maintaining food safety [3]. Traditional preservation methods such as freezing, pickling, canning, fermentation, and the use of chemical preservatives, while effective, often degrade the food’s original nutrients and taste and may even generate harmful substances [4]. Therefore, it is essential to optimize and develop new preservation techniques that ensure long-term food safety while retaining high nutritional value.

With the progress of science and technology, researchers have introduced a range of innovative preservation techniques, including high-temperature ultraviolet radiation [5], ionophores [6], the use of natural microorganisms with anticorrosive and antibacterial properties as alternatives to harmful chemical preservatives [7], and the application of nanomaterials as preservatives leveraging their unique physicochemical and antimicrobial properties [8]. These advancements aim to address the limitations of traditional preservation techniques by enhancing food safety, maintaining nutritional value, and prolonging shelf life. Nanomaterials have garnered significant attention in food preservation due to their distinctive physicochemical and antimicrobial characteristics [9,10]. Their versatility and effectiveness have been demonstrated in various applications. For instance, Jafari et al. investigated the preservation of yogurt using fish oil encapsulated within nanomaterials. Their study revealed that yogurt containing nanomaterials retained a fresher taste over the same period, demonstrating the anticorrosive properties of nanomaterials in slowing the oxidative processes in food [11]. Similarly, Hatamie et al. explored the antimicrobial efficacy of porous nanomaterials, specifically oxidized graphene/cobalt metal-organic frameworks, finding that these materials exhibited high bactericidal activity against Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus [12]. Furthermore, the structural properties of nanomaterials significantly influence their effectiveness in food preservation [13]. Nanomaterials with a larger specific surface area and hollow structures can adsorb and store antimicrobial agents more efficiently, thereby extending the shelf life of food products [14–16]. However, fabricating hollow spheres or capsules with well-defined structures often presents challenges, as they are difficult to prepare using a single-step process and may result in poorly defined structures [17]. This highlights the need for further research into developing hollow nanospheres with superior preservation properties and scalable production methods to meet practical needs in food safety.

Hypercrosslinked polymers (HCPs) are a class of porous organic nanomaterials characterized by highly crosslinked network structures [18,19]. They offer several advantages, including high stability, a large specific surface area, and an abundant pore structure [20], making them highly effective in various applications such as drug delivery [21], heterogeneous catalysis [22], and gas storage [23]. Crosslinked organic frameworks can be synthesized with diverse microscopic morphologies, including nanotubes [24], hollow nanospheres [25,26], nanoparticles [27], and two-dimensional films [28]. Among these, self-assembly enables the direct formation of porous hollow nanospheres (PHNs) in a single step, simplifying the preparation process by eliminating the template removal step required in hard and soft template methods [29]. However, like PHNs prepared through traditional template methods, hypercrosslinked polymers-porous hollow nanospheres (HCPs-PHNs) are typically synthesized as powders, which poses challenges for practical use in food preservation and increases the risk of environmental pollution. To address these issues, researchers often fabricate PHNs into films or coatings, enhancing their applicability and environmental friendliness [30–32].

Electrospinning technology, widely used in food packaging [33], biomedicine [34,35], energy [36], and environmental applications [37], is an effective method for preparing thin films for food preservation. This technique employs a high-voltage electrostatic field to stretch polymer solutions into nanofibers, forming uniform and dense thin films. The process retains the unique properties of HCPs and potentially enhances their mechanical strength and flexibility [38–40]. Additionally, the films produced through electrospinning exhibit a uniform pore structure and high specific surface area. When applied to food preservation, these films effectively block oxygen and water vapor while regulating the microenvironment within the package, thereby significantly extending the shelf life of food [41].

In this study, to effectively combine the hollow porous polymers with the packaging capabilities of films, a composite of HCPs and electrospun fibers was created by integrating PHNs with electrospinning technology. First, PHNs-like HCPs were synthesized through a Lewis acid-base interaction-guided self-assembly reaction. The excellent adsorption properties of PHNs enabled the adsorption of hexanal, which has antimicrobial and hydrophobic properties, resulting in the formation of Hex@PHNs. Next, these PHNs, with adsorbed hexanal molecules, were embedded into poly(ε-caprolactone) nanofibrous membranes (PCL/Hex@PHNs) via electrospinning. Structural characterization and analysis of the fibrous membranes confirmed the successful loading of hexanal molecules and PHNs. Additionally, the preservation performance of the fibrous membranes was evaluated by examining the changes in skin appearance, weight, and sugar content of fruits stored with different preservation membranes. This study provides valuable insights into enhancing the effectiveness of preservative membranes available in the market.

1,4-Benzenedimethanol (Mw = 138.17, Tihiai Industrial Development Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), Iron trichloride (Sinopharm Group Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), Hexanal (Mw = 100.16, Tihiai Industrial Development Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), 2,2,2-Trifluoroethanol (TFEA, Mw = 100.04, Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), Poly(ε-caprolactone) (PCL, Mw = 80,000, Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China), 1,2-dichloroethane(DCE, Tihiai Industrial Development Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China).

A fruit hardness scale (310–132 GY-2, Sanliang, Tokyo, Japan), a fruit sweetness meter (BM-04, Nohawk, Fuzhou, China), a field emission scanning electron microscope (SEM, Quanta FEG, FEI Company, Hillsboro OR, USA), a transmission electron microscope (TEM, Tecnai G2 F30, FEI Company, Hillsboro, OR, USA), a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (FT-IR, SPECTRUM100, Perkin Elmer, Shelton, CT, USA), a contact angle meter (DSA30, KRüSS GmbH, Hamburg, Germany), a vacuum drying oven (DHG-9070A, Gongyi City Yuhua Instrument Co., Ltd, Gongyi, China), an electronic analytical balance (BSA224S-CW, Sartorius Stedim Biotech, Göttingen, Germany), a magnetic stirrer (MS-M-S10, DLAB Scientific Co., Ltd., Beijing, China), a micro syringe pump (KDS100, Cole-Parmer, Shanghai, China).

2.3 Preparation of Porous Hollow Nanospheres (PHNs)

1,4-Benzenedimethanol (1 mmol, 138.2 mg) was dissolved in 100 mL of DCE in a flask. To this solution, FeCl3 (2 mmol, 324.4 mg) was added, and the reaction was conducted at 80°C under a nitrogen atmosphere. The Friedel-Crafts hypercrosslinking reaction was allowed to proceed for 24 h with moderate stirring. After completion, the precipitate was washed with ethanol/water (4:1) solution, filtration was completed and extracted using a Soxhlet extractor for 24 h. Finally, it was dried in a vacuum oven at 80°C to obtain brown granules.

2.4 Preparation of Porous Hollow Nanospheres Adsorbed Hexanal (Hex@PHNs)

PHNs (10 mg) were ground into a fine powder and then mixed with a hexanal solution. The mixture was stirred using a magnetic stirrer at room temperature for 24 h. The nanoparticles (Hex@PHNs) were then separated by centrifugation at 1000 rpm for 10 min. Afterward, the nanoparticles were washed three times with ethanol and dried in a vacuum oven for 24 h to obtain a brown powder.

A total of 1.0, 1.2, and 1.4 g of PCL were individually mixed with 10 mL of TFEA and stirred at room temperature for 24 h using a heated magnetic stirrer until the particles were completely dissolved, resulting in a clear, colorless solution. The prepared solution was then transferred into a 20 mL syringe and connected to a propeller pump to ensure smooth flow from the spinning head. The spinning head was linked to a high-voltage electrostatic generator using alligator clips, while aluminum foil was positioned 18 cm below as the collecting device. The experiments were conducted at 23 ± 4°C with 20 ± 5% relative humidity. PCL nanofibrous membranes were spun uniformly at a voltage of 6 kV and a flow rate of 0.6 mL/h.

2.6 Electrospinning PCL/Hex@PHNs

A PCL/Hex@PHNs mixture with a weight ratio of 10% w/w was prepared by dispersing Hex@PHNs into a 12% w/v PCL solution. The resulting PCL nanofibrous membrane, doped with 10% w/t Hex@PHNs, was fabricated through electrospinning at room temperature over a 12-h period. This membrane was designated as 10 PCL/Hex@PHNs. The electrospinning process was carried out at a voltage of 8 kV, a flow rate of 0.6 mL/h, with the experiment conducted at a temperature of 23 ± 4°C and relative humidity of 20 ± 5%.

3.1 Preparation and Characterisation of PCL/Hex@PHNs Nanofibrous Membrane

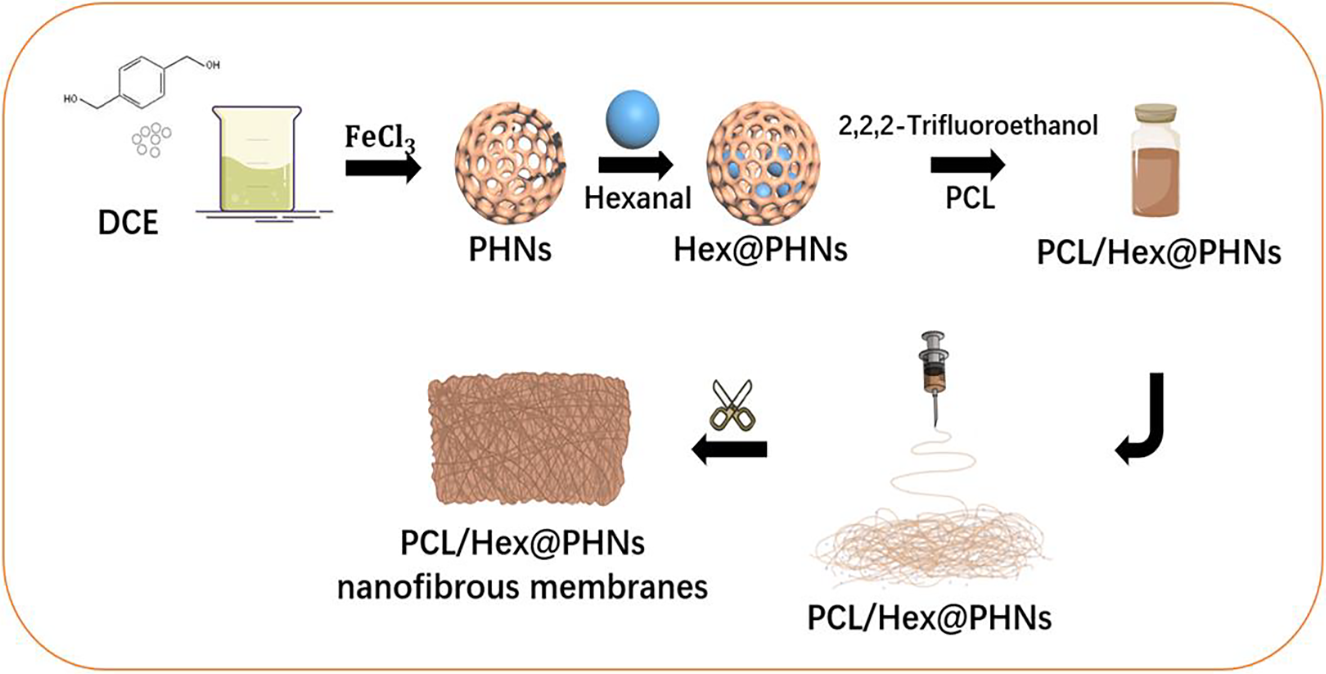

Fig. 1 illustrates the preparation of the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofibrous membrane using the electrospinning technique. First, 1,4-benzenedimethanol was dissolved in a 1,2-dichloroethane solution, and FeCl3 was added as a catalyst. The solution was continuously stirred for 24 h and then dried to obtain PHNs. Next, Hex@PHNs was prepared by grinding the PHNs into powder and immersing it in a hexanal solution. The resulting Hex@PHNs was then dispersed in a mixture of PCL and trifluoroethanol to form a spinning solution. Finally, the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofibrous membrane was successfully prepared using an electrospinning device.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of the synthesis process for the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofibrous membrane

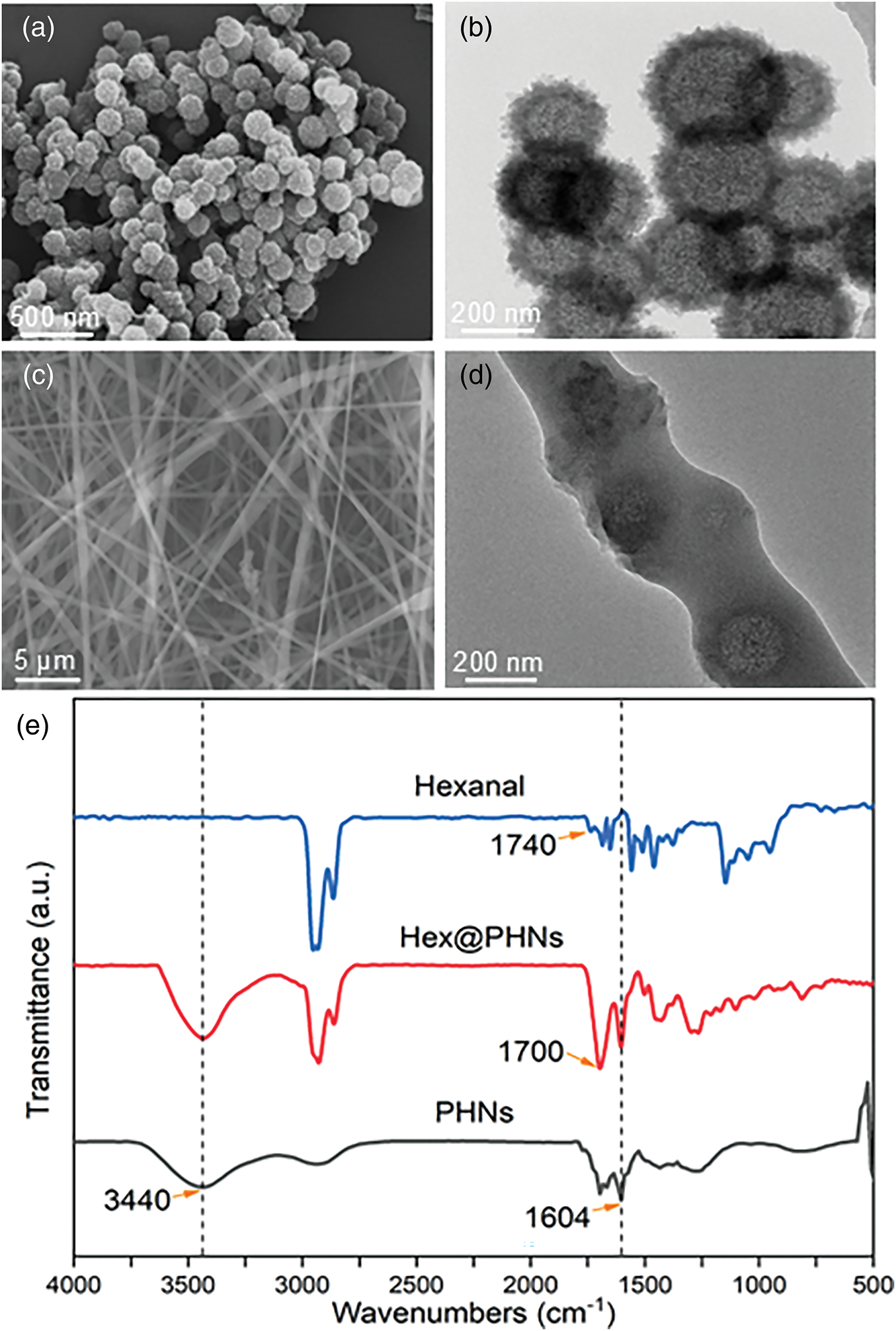

As shown in Fig. 2a,b, the microscopic appearance of the HCPs synthesized through the Friedel-Crafts reaction is spherical, with a hollow interior and an outer spherical shell, characteristic of hollow nanosphere morphology [42]. In previous work [24], the specific surface area and pore size distribution of PHNs synthesised from the same monomers and cross-linkers were determined. The PHNs were found to have a high specific surface area of 1069 m2 g−1 and a large number of micropores and mesopores with an average pore size value of 6.23 nm. This provided for the release of hexanal molecules from the spheres. In addition, thermogravimetric curves were also measured to analyse the thermal stability of the PHNs, and it was found that the PHNs exhibited excellent stability under nitrogen and air atmospheres up to 400°C without significant thermal degradation. The PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane was also characterized, and Fig. 2c reveals an intertwined three-dimensional fiber network structure, with an average fiber diameter of approximately 100 nm. During the electrospinning process, fluctuations in the spinning voltage can cause variations in fiber diameter, which is reflected in the non-uniform thickness observed in the image. Additionally, the TEM image in Fig. 2d shows that the Hex@PHNs are encapsulated within the fibers, and their microscopic morphology remains unchanged, confirming the successful integration of Hex@PHNs into the PCL nanofibers. Due to the small size of the hexanal molecules, their loading is not clearly visible in the TEM images of Hex@PHNs. Therefore, Fourier transform infrared (FT-IR) spectroscopy of PHNs, Hex@PHNs, and hexanal molecules were analyzed (Fig. 2e). In the FT-IR spectrum of hexanal, the absorption peaks between 2800–3000 cm−1 correspond to C-H stretching vibrations, and the peak near 1740 cm−1 is attributed to the C = O stretch in the aldehyde group [43,44]. The FT-IR spectrum of PHNs, synthesized through the self-assembly of 1,4-benzenedimethanol monomers, shows an absorption peak around 3440 cm−1 for -OH stretching vibrations and another around 1604 cm−1 for C = C stretching in the aromatic ring. Furthermore, the C = O absorption peak of hexanal shifts from 1740 to 1700 cm−1, likely due to interactions between hexanal molecules and the nanomaterials. The FT-IR spectra of Hex@PHNs show characteristic peaks of both hexanal and PHNs, providing evidence of the successful incorporation of hexanal molecules.

Figure 2: (a,b) Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images and Transmission electron microscope (TEM) images of Hex@PHNs at different magnifications; (c,d) SEM images and TEM images of PCL/Hex@PHNs at different magnifications; (e) FT-IR spectrum of hexanal molecules, PHNs, and Hex@PHNs

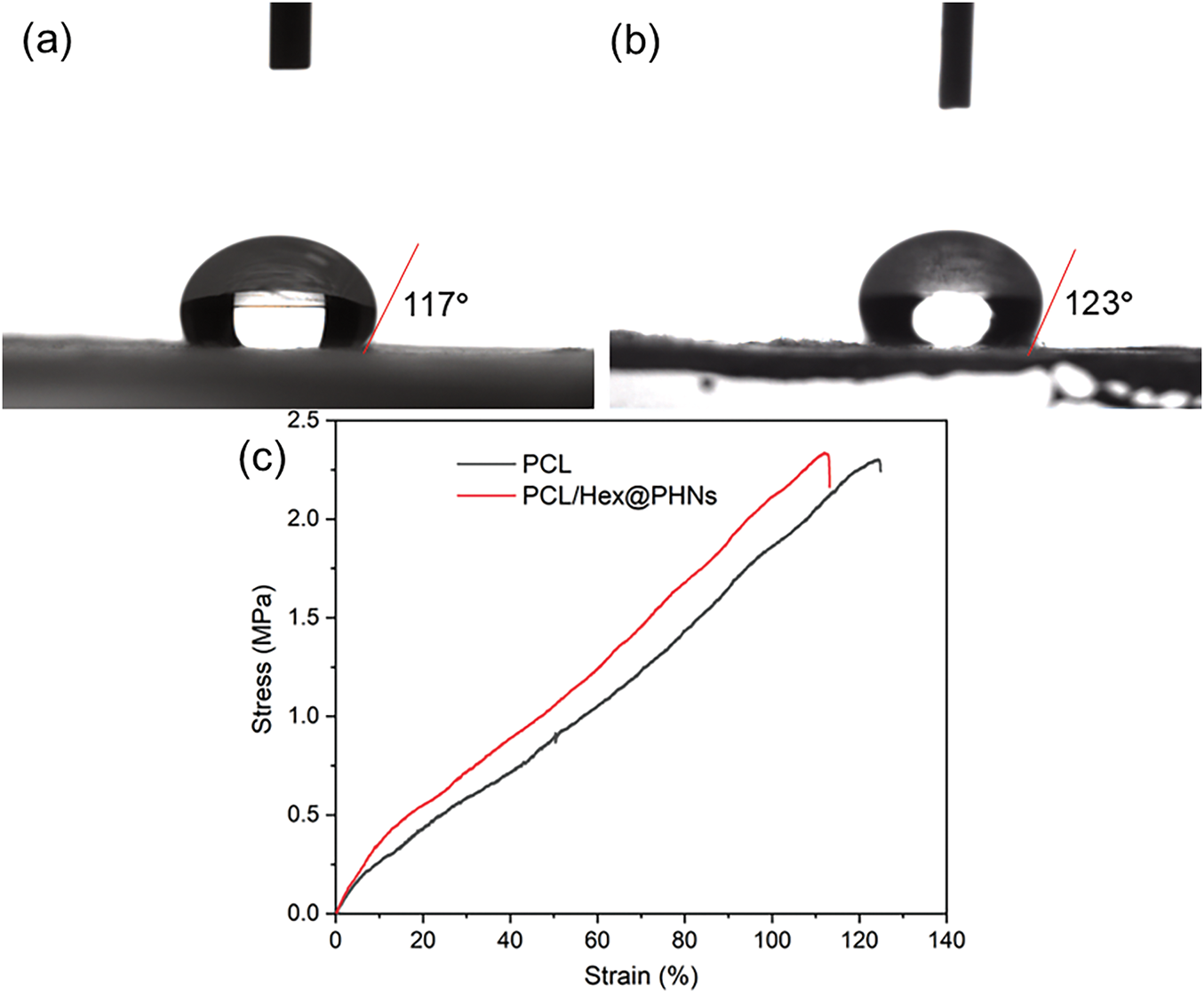

The hydrophobic nature of the fiber membrane effectively prevents water from penetrating from the external environment, keeping the preserved fruits in a dry setting. This helps avoid the creation of a humid environment that could promote the growth of bacteria and mold, thereby enhancing the preservation efficiency of the fiber membrane [45]. As shown in Fig. 3a,b, the water contact angle of the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofibrous membrane was 123°, compared to 117° for the pure PCL fiber membrane, indicating improved water resistance in the composite membrane. This enhancement can be attributed to the incorporation of hexanal, a hydrophobic molecule [46]. Furthermore, the composite fiber membrane exhibits significant antimicrobial properties due to the presence of hexanal molecules [47], making it highly promising for fruit preservation applications. Fig. 3c shows the stress-strain curves of pure PCL fibrous membranes and PCL/Hex@PHNs composite fibrous membranes, while Table 1 evaluates the mechanical properties of both fibrous membranes. It was found that due to the introduction of Hex@PHNs powder, the elastic modulus and elongation at break of the composite fibre membranes were reduced compared with that of the pure PCL fibre membranes, but they still had excellent ductility with an elongation at break of 112.40%, which meets the requirements of mechanical properties of fruit cling films.

Figure 3: Contact angle images of (a) pure PCL and (b) PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofibrous membranes and (c) their stress-strain curves

Leveraging the hydrophobic properties, antibacterial capabilities, and the ability of hexanal molecules to inhibit the enzymes that promote fruit ripening [47], the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofiber membrane was used to preserve strawberries, bananas, and kumquats. Four different fruit packaging systems were established to investigate the practical application of this composite nanofiber membrane in fruit packaging: a blank group, cling film, pure PCL fiber membrane, and PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane.

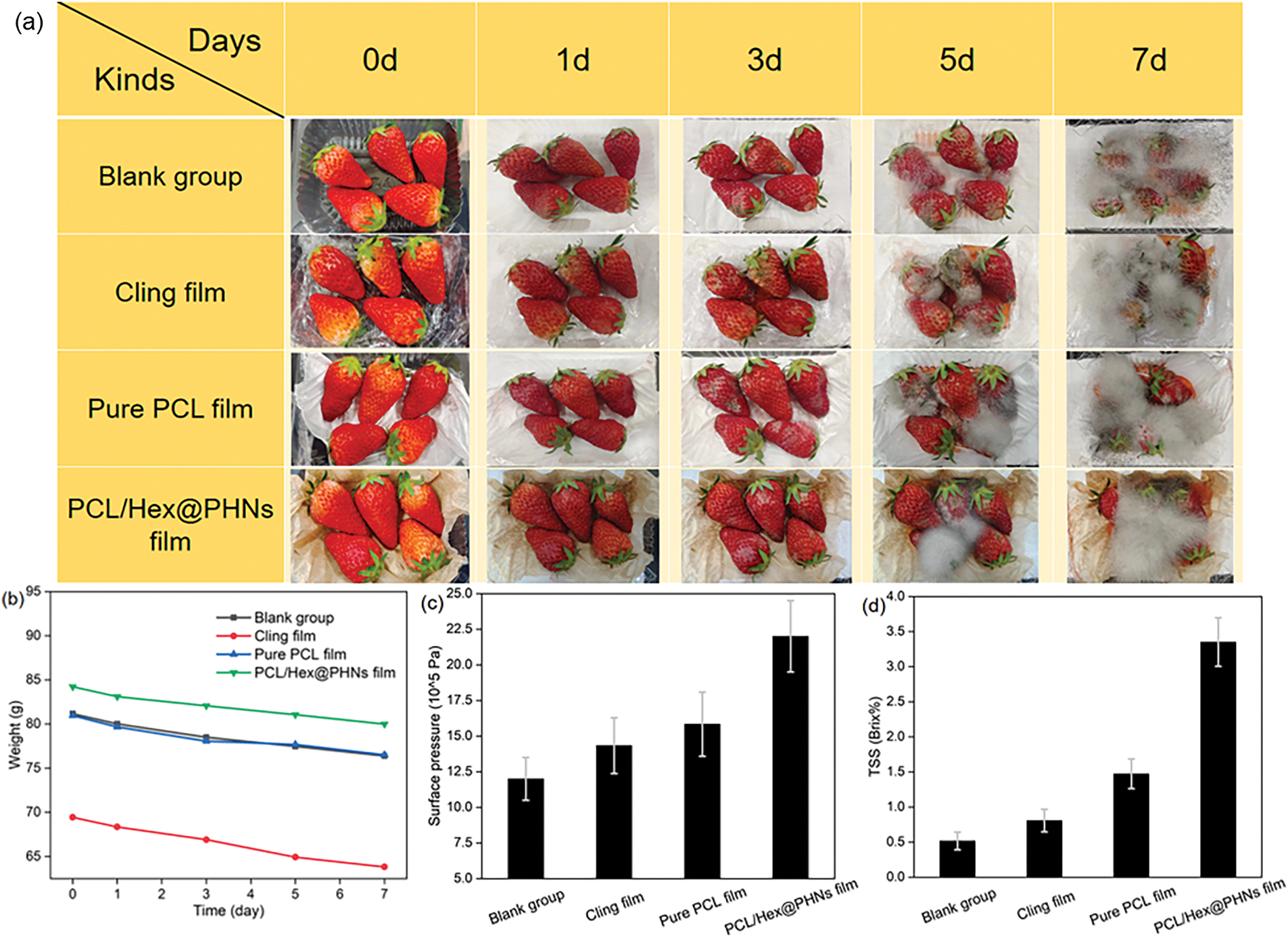

Strawberries were placed in plastic boxes, with three of the groups wrapped in different films. The changes in the four groups were then observed under room temperature conditions. Strawberries are particularly challenging to preserve due to their high moisture content and fragile texture. As shown in Fig. 4a, by the third day, all four groups of strawberries showed varying degrees of mold growth. However, the strawberries wrapped in cling film and the pure PCL fiber membrane exhibited more severe mold growth compared to the other two groups. This is likely because the blank control group lacked a film seal, allowing outside air to ventilate and air-dry the moisture produced by the fruits, reducing mold growth. The strawberries wrapped with the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofiber membrane displayed the least mold growth by the third day due to the combination of nanorods with a porous structure and hexanal molecules with antimicrobial properties, which provided both a high microporous structure and enhanced antimicrobial effects.

Figure 4: (a) Mycelial growth of mold and (b) weight changes of strawberries under different packaging conditions at various time points (0, 1, 3, 5, and 7 days); (c) peel surface pressure and (d) TSS content (in °Brix) of strawberries in the four groups after 7 days of storage

On the 15th day, all strawberries showed mold and hyphal growth, and by the seventh day, all strawberries were entirely covered with hyphae. Given the severe mold growth on the last day, it was challenging to observe the anti-corrosion advantage of the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofiber membrane. Therefore, weight loss was recorded for each group of strawberries at different storage times (Fig. 4b). After 7 days, the strawberries wrapped in plastic wrap exhibited the highest weight loss, at 5.61 g. The blank control group, pure PCL fiber membrane group, and PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane group showed weight losses of 4.79, 4.44, and 4.22 g, respectively. The cling film group had the highest weight loss, consistent with the most severe mold growth on the third day, while the blank control group had the second-highest weight loss due to exposure to air, which caused greater evaporation of water from the strawberries compared to the other groups. As shown in Fig. 4c, on the seventh day, the strawberries packaged with the PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane had the highest pressure on their skin, indicating that these strawberries retained the most moisture, consistent with the lowest weight loss. Additionally, the strawberries in the PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane group exhibited the highest total soluble solids (TSS) values (Fig. 4d). These results suggest that the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofiber membrane helps slow down the reduction of moisture and sugar content in strawberries during storage, maintains their structural integrity, delays softening, and ultimately prolongs their freshness, providing a better taste for consumption.

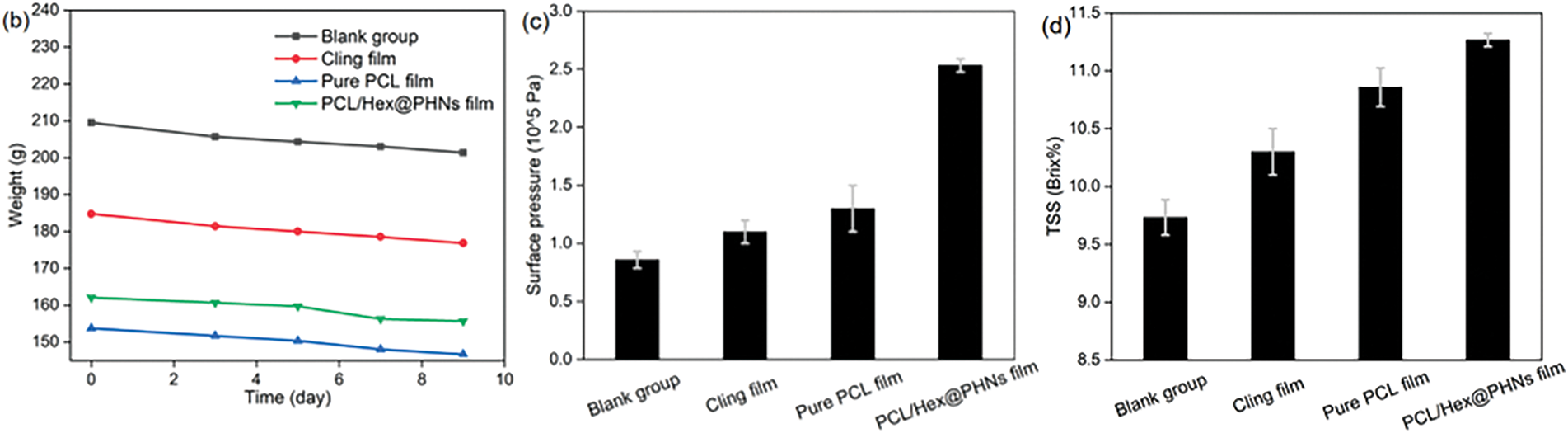

As shown in Fig. 5a, after nine days of storage, bananas from the four different packaging conditions displayed black decay spots on the peel. On the 7th day, the bananas in the cling film group exhibited more severe decay compared to the other groups. This can be attributed to the airtight and humid environment created by the cling film, which accelerated the ripening and decay of the bananas [48]. However, by the ninth day, while the bananas packaged in regular cling film showed the most noticeable decay, the other three groups showed minimal differences in the degree of decay. To further highlight the benefits of the PCL/Hex@PHNs nanofiber membrane for banana preservation, we also measured the weight loss, skin pressure, and pulp sugar content of the bananas on the final day (Fig. 5b–d).

Figure 5: (a) Peel changes and (b) weight variations of bananas under different packaging conditions at various time points (0, 3, 5, 7, and 9 days); (c) peel surface pressure and (d) TSS content (in °Brix) of bananas in the four groups after 9 days of storage

After 9 days of storage, the weight loss of bananas in the blank control group, cling film group, pure PCL fiber film group, and PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber film group were 8.13, 7.94, 7.04, and 6.41 g, respectively. Additionally, among the four groups, the blank control group exhibited the lowest skin pressure, indicating that the open packaging system allowed for significant water evaporation from the banana pulp, resulting in a floppy peel. On the other hand, the PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane group showed the lowest weight loss, the highest skin pressure, and the highest TSS value, demonstrating that the composite fiber membrane effectively slowed down both water evaporation and decay while preserving the taste and quality of the bananas.

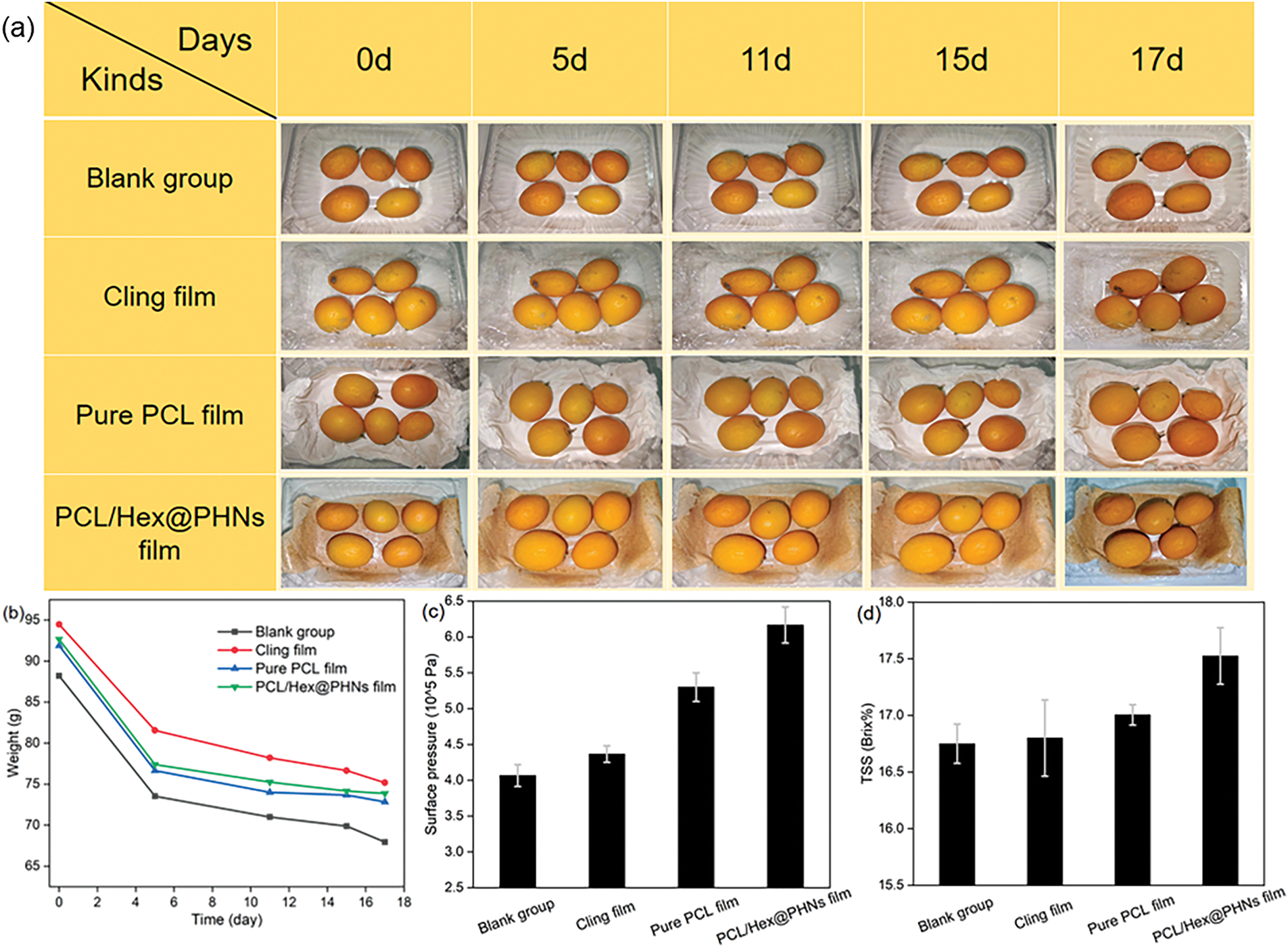

Since kumquats can be stored for extended periods under ambient conditions [49], none of the four groups of kumquats showed signs of mold or decay after 17 days of storage. However, compared to day one, noticeable wrinkles appeared on the rind of kumquats in all groups after 17 days, and the firmness of the fruit decreased (Fig. 6a). The weight loss of the kumquats in the four groups was measured at different time points (Fig. 6b). The blank control group, cling film group, pure PCL fiber film group, and PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber film group showed weight losses of 20.26, 19.30, 19.05, and 18.80 g, respectively. These results suggest that the composite fiber film helps delay water loss in kumquats, thus preserving their freshness to some extent. As shown in Fig. 6c,d, skin pressure and TSS values of the kumquats on the 17th day were also measured. Kumquats wrapped in the PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane exhibited the highest skin pressure and TSS values, indicating better texture and taste. This further demonstrates the superior ability of the PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane to maintain the freshness of kumquats.

Figure 6: (a) Peel changes and (b) weight variations of kumquats under different packaging conditions at various time points (0, 5, 11, 15, and 17 days); (c) peel surface pressure and (d) TSS content (in °Brix) of kumquats in the four groups after 17 days of storage

Based on the freshness preservation results of strawberries, bananas, and kumquats across the four different packaging conditions, it is evident that the PCL/Hex@PHNs composite fiber film offers the best preservation performance. This film effectively reduces water evaporation from the three types of fruit, prolonging their taste and quality. The superior performance is attributed to the unique three-dimensional cross-linked network structure of the PCL/Hex@PHNs fiber membrane, which provides excellent air permeability and regulates the humidity and oxygen concentration inside the package, ensuring optimal storage conditions for the fruits [50]. Additionally, the antimicrobial properties of the hexanal molecules and the porous structure of the nanospheres in the composite membrane inhibit microbial growth and slow down the fruit decay process, ultimately extending the freshness of the fruit [51,52].

In conclusion, porous nanostructures significantly enhance the freshness preservation performance of fiber membranes, thereby extending the shelf life of fruits. The self-assembly method based on HCPs effectively encapsulated the hexanal molecules within the hollow spheres, ensuring their uniform distribution and controlled release within the fiber membranes. This slow release allows the hexanal molecules to maintain their antimicrobial effects over an extended period. Moreover, the three-dimensional network structure of the fiber membrane not only provides excellent air permeability but also regulates the internal environment to further inhibit microbial growth, thus preserving the fruits’ palatability for a longer time. The superior performance of the PCL/Hex@PHNs composite fiber membrane in reducing weight loss, maintaining skin pressure, and retaining sugar content in strawberries, bananas, and kumquats further underscores its potential for use in fruit preservation. This study not only enhances the performance of food packaging materials but also offers new insights for future research into fruit preservation technologies.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to the support of the University of Shanghai for Science and Technology’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship Program for students.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jingli Li: methodology, formal analysis, writing—original draft, validation. Xianting Fu: data curation, visualization. Yuheng Wen: writing—review and editing, resources. Hailang Xu: supervision, writing—review and editing. Qian Liao: methodology, supervision. Wenliang Song: writing, software. Deng-Guang Yu: fund, resources. The Shanghai Sailing Program (21YF1431000, 22YF1417700). All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Sridhar A, Ponnuchamy M, Kumar PS, Kapoor A. Food preservation techniques and nanotechnology for increased shelf life of fruits, vegetables, beverages and spices: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2021;19(2):1715–35. doi:10.1007/s10311-020-01126-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Guzik P, Szymkowiak A, Kulawik P, Zając M. Consumer attitudes towards food preservation methods. Foods. 2022;11(9):1349. doi:10.3390/foods11091349. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lisboa HM, Pasquali MB, dos Anjos AI, Sarinho AM, de Melo ED, Andrade R, et al. Innovative and sustainable food preservation techniques: enhancing food quality, safety, and environmental sustainability. Sustainability. 2024;16(18):8223. doi:10.3390/su16188223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ariti K, Jebo K. Determination of traditional and biologically viable methods for food preservation: a review. Int J Food Sci Biotechnol. 2023;8(1):1–5. doi:10.11648/j.ijfsb.20230801.11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang Y, Ma Z, Chen J, Yang Z, Ren Y, Tian J, et al. Electromagnetic wave-based technology for ready-to-eat foods preservation: a review of applications, challenges and prospects. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;2024:1–26. doi:10.1080/10408398.2024.2399294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Zhou R, Rezaeimotlagh A, Zhou R, Zhang T, Wang P, Hong J, et al. In-package plasma: from reactive chemistry to innovative food preservation technologies. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2022;120:59–74. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2021.12.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. El-Saber Batiha G, Hussein DE, Algammal AM, George TT, Jeandet P, Al-Snafi AE, et al. Application of natural antimicrobials in food preservation: recent views. Food Control. 2021;126(6):108066. doi:10.1016/j.foodcont.2021.108066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Bajpai VK, Kamle M, Shukla S, Mahato DK, Chandra P, Hwang SK, et al. Prospects of using nanotechnology for food preservation, safety, and security. J Food Drug Anal. 2018;26(4):1201–14. doi:10.1016/j.jfda.2018.06.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Ghosh C, Bera D, Roy L. Role of nanomaterials in food preservation. In: Prasad R, editor. Microbial nanobionics: basic research and applications. Vol. 2. Switzerland, Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2019. p. 181–211. [Google Scholar]

10. Kumar S. Prospects and challenges of nanomaterials in sustainable food preservation and packaging: a review. Discov Nano. 2024;19(1):178. doi:10.1186/s11671-024-04142-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ghorbanzade T, Jafari SM, Akhavan S, Hadavi R. Nano-encapsulation of fish oil in nano-liposomes and its application in fortification of yogurt. Food Chem. 2017;216:146–52. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2016.08.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Hatamie S, Ahadian MM, Soufi Zomorod M, Torabi S, Babaie A, Hosseinzadeh S, et al. Antibacterial properties of nanoporous graphene oxide/cobalt metal organic framework. Mater Sci Eng C. 2019;104(36):109862. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.109862. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Li Y, Liu J, McClements DJ, Zhang X, Zhang T, Du Z. Recent advances in hollow nanostructures: synthesis methods, structural characteristics, and applications in food and biomedicine. J Agric Food Chem. 2024;72(37):20241–60. doi:10.1021/acs.jafc.4c05910. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Biswal AK, Usmani M, Ahammad SZ, Saha S. Unveiling the slow release behavior of hollow particles with prolonged antibacterial activity. J Mater Sci. 2018;53(8):5942–57. doi:10.1007/s10853-018-1991-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Biswal AK, Hariprasad P, Saha S. Efficient and prolonged antibacterial activity from porous PLGA microparticles and their application in food preservation. Mater Sci Eng C. 2020;108:110496. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2019.110496. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Garavand F, Diako K, Niaz M, Joinul I, Injeela K, Shima J, et al. Recent progress in using zein nanoparticles-loaded nanocomposites for food packaging applications. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024;64(12):3639–59. doi:10.1080/10408398.2022.2133080. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Lou XW, Archer LA, Yang Z. Hollow Micro-/Nanostructures: synthesis and applications. Adv Mater. 2008;20(21):3987–4019. doi:10.1002/adma.200800854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Raza S, Nazeer S, Abid A, Kanwal A. Recent research progress in the synthesis, characterization and applications of hyper cross-linked polymer. J Polym Res. 2023;30(11):415. doi:10.1007/s10965-023-03783-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Huang J, Turner SR. Hypercrosslinked polymers: a review. Polym Rev. 2018;58(1):1–41. doi:10.1080/15583724.2017.1344703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Tan L, Tan B. Hypercrosslinked porous polymer materials: design, synthesis, and applications. Chem Soc Rev. 2017;46(11):3322–56. doi:10.1039/c6cs00851h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Chang Y, Liu T, Qi R, Chen S, Guo Y, Yang L, et al. Cell-regulated hollow sulfur nanospheres with porous shell: a dual-responsive carrier for sustained drug release. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2022;10(16):5138–47. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.1c08423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Gao S, Zhang L, Yu H, Wang H, He Z, Huang K. Palladium-encapsulated hollow porous carbon nanospheres as nanoreactors for highly efficient and size-selective catalysis. Carbon. 2021;175(45):307–11. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2021.01.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Mehrizi MZ, Abdi J, Rezakazemi M, Salehi E. A review on recent advances in hollow spheres for hydrogen storage. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2020;45(35):17583–604. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.04.201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Song W, Zhang Y, Varyambath A, Kim I. Guided assembly of well-defined hierarchical nanoporous polymers by lewis acid-base interactions. ACS Nano. 2019;13(10):11753–69. doi:10.1021/acsnano.9b05727. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Jia Z, Wang K, Tan B, Gu Y. Hollow hyper-cross-linked nanospheres with acid and base sites as efficient and water-stable catalysts for one-pot tandem reactions. ACS Catal. 2017;7(5):3693–702. doi:10.1021/acscatal.6b03631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Xu Y, Wang T, He Z, Zhou M, Yu W, Shi B, et al. Preparation of multifunctional hollow microporous organic nanospheres via a one-pot hyper-cross-linking mediated self-assembly strategy. Polym Chem. 2018;9(29):4017–24. doi:10.1039/c8py00694f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Metwally AM, ElKhawaga HA, Shaaban A-FF, Reda LM. Suspension polymerization for synthesis of new hypercrosslinked polymers nanoparticles for removal of copper ions from aqueous solutions. Polym Bull. 2023;80(11):12249–70. doi:10.1007/s00289-022-04654-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Shi P, Chen X, Sun Z, Li C, Xu Z, Jiang X, et al. Thickness controllable hypercrosslinked porous polymer nanofilm with high CO2 capture capacity. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2020;563(40):272–80. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2019.12.038. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lai X, Halpert JE, Wang D. Recent advances in micro-/nano-structured hollow spheres for energy applications: from simple to complex systems. Energy Environ Sci. 2012;5(2):5604–18. doi:10.1039/c1ee02426d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Fang Y, Chen J, Lin C, Sun H, Chen Y. Study on the preparation of hollow silica nanospheres and their heat retention and hydrophobicity in paperboard coatings. Packag Technol Sci. 2025;38(4):283–92. doi:10.1002/pts.2872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li W, Zhang J, Chen X, Zhou X, Zhou J, Sun H, et al. Organic nanoparticles incorporated starch/carboxymethylcellulose multifunctional coating film for efficient preservation of perishable products. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;275:133357. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.133357. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang Y, Tang Y, Liao Q, Qian Y, Zhu L, Yu D-G, et al. Silver oxide decorated urchin-like microporous organic polymer composites as versatile antibacterial organic coating materials. J Mater Chem B. 2024;12(8):2054–69. doi:10.1039/D3TB02619A. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Han WH, Li X, Yu GF, Wang BC, Huang LP, Wang J, et al. Recent advances in the food application of electrospun nanofibers. J Ind Eng Chem. 2022;110:15–26. doi:10.1016/j.jiec.2022.02.044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kang D, Li Y, Dai X, Li Z, Cheng K, Song W, et al. A soothing lavender-scented electrospun fibrous eye mask. Molecules. 2024;29(22):5461. doi:10.3390/molecules29225461. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Parham S, Kharazi AZ, Bakhsheshi-Rad HR, Ghayour H, Ismail AF, Nur H, et al. Electrospun nano-fibers for biomedical and tissue engineering applications: a comprehensive review. Materials. 2020;13(9):2153. doi:10.3390/ma13092153. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Xu H, Li B, Wang Z, Liao Q, Zeng L, Zhang H, et al. Improving supercapacitor electrode performance with electrospun carbon nanofibers: unlocking versatility and innovation. J Mater Chem A. 2024;12(34):22346–71. doi:10.1039/d4ta03192j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Zhang W, He Z, Han Y, Jiang Q, Zhan C, Zhang K, et al. Structural design and environmental applications of electrospun nanofibers. Compos Part A Appl Sci Manuf. 2020;137:106009. doi:10.1016/j.compositesa.2020.106009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Xu H, Yagi S, Ashour S, Du L, Hoque ME, Tan L. A review on current nanofiber technologies: electrospinning, centrifugal spinning, and electro-centrifugal spinning. Macromol Mater Eng. 2023;308(3):2200502. doi:10.1002/mame.202200502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Lu X, Wang H, Chen J, Yang L, Hu T, Wu F, et al. Negatively charged hollow crosslinked aromatic polymer fiber membrane for high-efficiency removal of cationic dyes in wastewater. Chem Eng J. 2022;433(2–3):133650. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.133650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhang C, Li Y, Wang P, Zhang H. Electrospinning of nanofibers: potentials and perspectives for active food packaging. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2020;19(2):479–502. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.12536. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Jiang W, Zhao P, Song W, Wang M, Yu DG. Electrospun zein/polyoxyethylene core-sheath ultrathin fibers and their antibacterial food packaging applications. Biomolecules. 2022;12(8):1110. doi:10.3390/biom12081110. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Song W, Zhang Y, Tran CH, Choi HK, Yu DG, Kim I. Porous organic polymers with defined morphologies: synthesis, assembly, and emerging applications. Prog Polym Sci. 2023;142:101691. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2023.101691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Ranjan S, Chandrasekaran R, Paliyath G, Lim LT, Subramanian J. Effect of hexanal loaded electrospun fiber in fruit packaging to enhance the post harvest quality of peach. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2020;23(1):100447. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2019.100447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Kathuria A, Bollen T, Kivy M, Hamachi L, Buntinx M, Auras R. Mechanochemical synthesis of Calcium-Squarate MOF and encapsulation of hexanal. J Incl Phenom Macrocycl Chem. 2024;105:65–74. doi:10.1007/s10847-024-01266-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Chen Y, Li Y, Qin S, Han S, Qi H. Antimicrobial UV blocking, water-resistant and degradable coatings and packaging films based on wheat gluten and lignocellulose for food preservation. Compos Part B Eng. 2022;238:109868. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.109868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Jiang F, Liang Y, Liu L, Zhang Y, Deng Y, Wei F, et al. One-pot co-crystallized hexanal-loaded ZIF-8/quaternized chitosan film for temperature-responsive ethylene inhibition and climacteric fruit preservation. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;265(13):130798. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130798. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

47. Azhar AH, Pak Dek MS, Ramli NS, Rukayadi Y, Mediani A, Mohd Maidin N. Hexanal treatment for improving the shelf-life and quality of fruits: a review. Pertanika J Trop Agric Sci. 2024;47(1):289–305. doi:10.47836/pjtas.47.1.20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Song MB, Tang LP, Zhang XL, Bai M, Pang XQ, Zhang ZQ. Effects of high CO2 treatment on green-ripening and peel senescence in banana and plantain fruits. J Integr Agric. 2015;14(5):875–87. doi:10.1016/S2095-3119(14)60851-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Yun Z, Jin S, Ding Y, Wang Z, Gao H, Pan Z, et al. Comparative transcriptomics and proteomics analysis of citrus fruit, to improve understanding of the effect of low temperature on maintaining fruit quality during lengthy post-harvest storage. J Exp Bot. 2012;63(8):2873–93. doi:10.1093/jxb/err390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Russo F, Castro-Muñoz R, Santoro S, Galiano F, Figoli A. A review on electrospun membranes for potential air filtration application. J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10(5):108452. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2022.108452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Fadida T, Selilat-Weiss A, Poverenov E. N-hexylimine-chitosan, a biodegradable and covalently stabilized source of volatile, antimicrobial hexanal. Next generation controlled-release system. Food Hydrocoll. 2015;48:213–9. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2015.02.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Zhao M, Zeng W, Wang Y, Kai G, Qian J. Application of porous composites in antibacterial field. Mater Today Commun. 2023;37:107410. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2023.107410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools