Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Computational Study Analysis of Adsorption Behavior of MgFe2O4-Collagen Hydrogels with Spinal Cord Tissues

1 School of Physics & Materials Studies, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Shah Alam, 40450, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

2 Sustainable Energy Materials Laboratory, Faculty of Applied Sciences, Universiti Teknologi MARA (UiTM), Shah Alam, 40450, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia

3 Department of Electronic & Communication Engineering, Graphic Era (Deemed to be University Dehradun), Uttarakhand, 248002, India

* Corresponding Authors: Surajudeen Sikiru. Email: ; Mohd Muzamir Mahat. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Smart Polymeric Materials for Sustainable Energy Solutions: Bridging Advances in Energy and Biomedical Applications)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 713-728. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.065378

Received 11 March 2025; Accepted 16 July 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Spinal cord injury presents a significant challenge in regenerative medicine due to the complex and delicate nature of neural tissue repair. This study aims to design a conductive hydrogel embedded with magnetic MgFe2O4 nanoparticles to establish a bioelectrically active and spatially stable microenvironment that promotes spinal cord regeneration through computational analysis (BIOVIA Materials Studio). Hydrogels, known for their biocompatibility and extracellular matrix-mimicking properties, support essential cellular behaviors such as adhesion, proliferation, and migration. The integration of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles imparts both electrical conductivity and magnetic responsiveness, enabling controlled transmission of electrical signals that are crucial for guiding cellular processes like differentiation and directed migration. Furthermore, the hydrogel acts as a delivery medium, facilitating the adsorption of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles onto spinal tissue through strong Van der Waals and intramolecular interactions. The computational simulations revealed a robust adsorption profile, with a binding distance of 20.180 Å and a cumulative adsorption energy of 2740.42 kcal/mol, indicating stable nanoparticle-tissue interactions. Pressure-dependent sorption analysis further demonstrated that reduced pressure conditions enhance adsorption strength, promoting tighter material-tissue integration. The adverse Van der Waals energy and increased intramolecular energy observed under these conditions underscore the importance of optimized adsorption settings for functional tissue interface formation. Altogether, the conductive hydrogel-MgFe2O4 composite system offers a promising therapeutic platform by combining structural support, electrical stimulation, and magnetic guidance, thereby enhancing cell-material interactions and fostering an environment conducive to spinal cord tissue repair.Keywords

Recent advancements in hydrogel-based delivery systems have opened new avenues in regenerative medicine and cancer therapy [1]. The integration of insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) into bioactive glass-incorporated alginate-poloxamer/silk fibroin hydrogels offers controlled release, enhancing cellular proliferation and tissue regeneration [2]. Similarly, dual network hydrogels embedded with bone morphogenic protein-7 (BMP-7)-loaded hyaluronic acid nanoparticles have shown significant potential in driving the chondrogenic differentiation of synovium-derived mesenchymal stem cells, highlighting their promise for cartilage repair [3]. Meanwhile, injectable hydrogels designed for localized drug delivery in malignant tumors provide a minimally invasive platform for sustained therapeutic action, improving drug retention and reducing systemic toxicity. These studies collectively underscore the versatility of hydrogel systems in achieving targeted, efficient, and biocompatible delivery of bioactive agents, paving the way for next-generation treatments across various clinical fields. The tailored mechanical properties, degradation rates, and bioactivity of these hydrogels are critical for their success in diverse therapeutic applications.

The central nervous system (CNS) consists of the brain and the spinal cord which is connected to a bundle of nerve fibers or tissues in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) that simultaneously function together for the bioelectrical transmission. This is to ensure and maintain the motor and sensory function of a human being [4–6]. Any injuries to either the brain or the spinal cord will cause the bioelectrical transmission to be blocked or disturbed due to the presence of neuronal gaps in the nerve tissues [7–9]. Spinal cord injuries (SCI) are a traumatic injury to the spinal cord, which will disturb the connection between the CNS and PNS leading to the loss of motor and sensory function in the patient [10–12].This is due to the formation of a fluid-filled cystic cavity at the lesion site, which varies significantly in volume and geometry across individuals. This cavity creates a hostile microenvironment, characterized by inflammation and inhibitory biochemical signals, impeding endogenous tissue repair and axonal regeneration [13,14]. Due to the three-dimensional structure, interconnected porous topography, and water-swollen polymer networks, injectable hydrogels have emerged as a promising strategy to physically bridge lesion cavities while providing a supportive scaffold for cell infiltration and tissue repair [15–18]. Their unique advantages include minimally invasive delivery, tunable mechanical properties, and the ability to conform to irregular lesion geometries, making them ideal for filling a complex, patient-specific injury site.

In addition to these challenges, recent studies have highlighted a significant but often overlooked factor in SCI treatment, which is the altered mechanical properties of soft tissues surrounding the lesion site [19,20]. In vivo biomechanical analysis has shown that individuals with SCI exhibit regional variations in tissue stiffness [21]. The proximal and middle thigh regions become significantly softer, while the distal regions become stiffer, compared to able-bodied individuals [22]. These mechanical shifts increase the risk of internal stress, deformation, and impaired tissue perfusion in softer areas, while altering pressure distribution in stiffer zones [23]. Such regional stiffness variations are particularly important for clinical hydrogel therapies, as the mechanical mismatch between the implanted material and host tissue may lead to poor integration or even propagation to secondary injury [24]. This reinforces the need to design a hydrogel system that not only replicates the biochemical cues of native tissue but also mechanically integrates with the altered tissue properties of the SCI microenvironment.

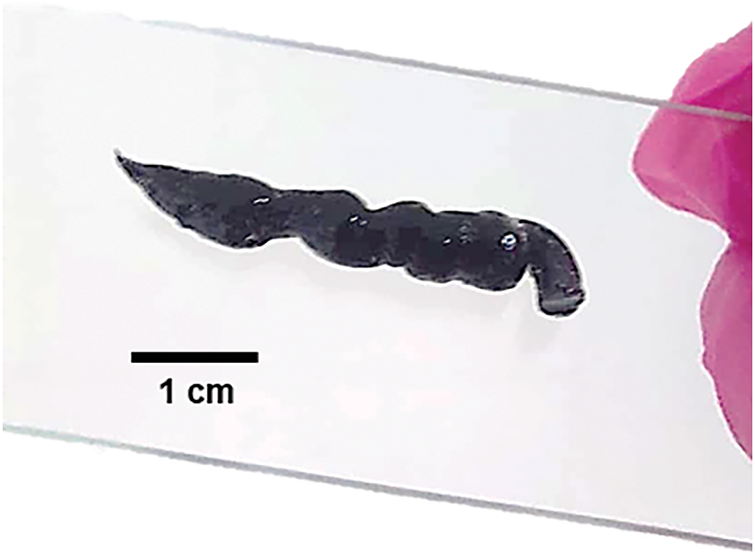

Hydrogels’ critical property is governed by the equilibrium between osmotic forces driving water uptake and elastic restraints from the polymer network, also known as swelling behavior. For SCI applications, controlled swelling properties are essential, as insufficient swelling may lead to poor integration with host tissues, while excessive swelling can generate harmful mechanical pressure on adjacent neural tissues, exacerbating secondary injury cascades [23,25]. The swelling ratio is influenced by various factors, including polymer compositions (collagen, hyaluronic acid, alginate), crosslinking density, and environmental stimuli (pH, temperature). The usage of naturally occurring polymers such as chitosan, gelatin, alginate, fibrin and collagen in the development of conductive hydrogels has been widely studied due to their biocompatibility and their ability to degrade without releasing toxic substances in the body system (Fig. A1 in the Appendix A) [26,27]. Collagen is a protein that can be abundantly found in bones, cartilage, tendons, and skin of animals, and utilized into a 3D porous structure of the hydrogels’ matrix. Collagen-based hydrogels, in particular, are widely studied for their biocompatibility and resemblance to the extracellular matrix (ECM). Since neural tissues rely on electrochemical signaling to coordinate axonal regeneration and synaptic connections, the conductivity properties of hydrogels are deemed critical. However, their limited electrical conductivity and mechanical stability in dynamic physiological environments have driven the incorporation of functional fillers, such as conductive nanoparticles, to enhance their therapeutic potential.

Figure 1: Configuration of the spinal cord tissue, collagen and MgFe2O4 nanoparticles chemical component for computational simulation study

Conductive hydrogels can mimic the electrophysiological microenvironment of the spinal cord, providing biophysical cues that promote neurite outgrowth, Schwann cell migration, and remyelination. For example, studies have shown that conductive scaffolds enhance the alignment and differentiation of neural progenitor cells by facilitating electrical signal propagation across lesion sites, which is highly relevant in SCI repair [28,29]. Researchers have explored the integration of diverse conductive fillers into hydrogel matrices to improve their electrical properties and mechanical stability for neural tissue engineering applications. For instance, silver nanoparticles-infused hydrogels [30] have demonstrated improved electrical properties and supported neural cell growth. However, the concerns of clearance and uncontrolled swelling have limited their widespread application. Additionally, carbon-based materials like carbon nanotubes (CNTs) [14] have exhibited improved mechanical strength and electrical conductivity when infused into hydrogels. Nevertheless, the inconsistencies of electrical performance and swelling behavior due to their non-homogeneous 1D-particle dispersion remain a challenge. Moreover, conductive polymers like polypyrrole (PPy)-based hydrogels have demonstrated the ability to support neural stem cell differentiation with or without electrical stimulation. Polyaniline (PANI)-incorporated hydrogels have also shown promise in enhancing electrical conductivity and supporting nerve regeneration. However, the critical challenge lies in dopant ion dissipation within hydrated environments. Leaching of dopants compromises electrical conductivity, destabilizes swelling behavior, and risks of cytotoxicity necessitate a comprehensive dopant retention strategy.

In recent years, magnetic nanoparticles (MNPs), such as iron oxide (Fe3O4), have been widely explored for their dual functionality in providing magnetic responsiveness and electrical conductivity. Hydrogels embedded with Fe3O4 nanoparticles have been reported to facilitate neural tissue regeneration by enabling remote magnetic stimulation and enhancing electrical properties [31]. Unlike Fe3O4, magnesium ferrite (MgFe2O4) nanoparticle is less susceptible to oxidation due to its spinel structure, where Mg2+ ions occupy tetrahedral sites, and stabilized Fe3+ ions [31–33]. Moreover, MgFe2O4 nanoparticles are less prone to agglomeration than Fe3O4 due to weaker magnetic interactions and often larger particle sizes [33]. This makes it a superior choice for biomedical applications requiring long-term stability. For this reason, the incorporation of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles presents a compelling alternative.

Importantly, MgFe2O4 nanoparticles have been reported to demonstrate low cytotoxicity in both in vitro and in vivo studies. For instance, Ref. [32] evaluated MgFe2O4 nanoparticles and observed no significant cytotoxic effects on neural stem cells over 72 h of exposure, while another study by [34] confirmed minimal inflammatory response and tissue compatibility upon subcutaneous implantation in mice over four weeks. Additionally, MgFe2O4 nanoparticles degrade into physiologically benign ions (Mg2+ and Fe3+), which are naturally regulated in the body and reduces concerns about toxic byproducts [35]. Magnesium ions have been shown to play a supportive role in neuronal development and axonal growth, further supporting their long-term safety in neural applications. Their chemical stability and magnetic functionality further justify MgFe2O4 nanoparticles as a promising alternative for sustained use in biomedical applications, including SCI repair. On the other hand, the most significant advantage of incorporating MgFe2O4 nanoparticles into hydrogel matrices lies in their ability to modulate swelling behavior while maintaining mechanical integrity [36]. Previous studies have shown that in gelatine/PANI-based hydrogels, MgFe2O4 forms stable crosslinked networks that improve pH resistance and decrease water uptake under osmotic pressure. These MNPs contribute to elastic restraint through magnetic and electrostatic interactions, thereby reducing excessive swelling. This property is critical for SCI repair, where excessive swelling pressure (>50 kPa) can compress the adjacent neural tissues and exacerbate secondary injury.

Despite these advantages, the interplay between hydrogel swelling and mechanical confinement within the spinal lesion remains poorly understood. After injection, hydrogels may experience confinement pressure from surrounding tissues, which counteracts swelling forces and alters intermolecular interactions within the polymer network. For example, Van der Waals (VDW) forces between the hydrogel and host tissue may strengthen adhesion under moderate pressure, while excessive intramolecular strain from over-swelling could destabilize the hydrogel’s microstructure. These dynamics are further complicated by the addition of MNPs, which introduce localized magnetic interactions and influence the hydrogel’s elastic modulus. Current design paradigms often prioritize biochemical compatibility over biomechanical optimization, neglecting the spinal cord’s limited tolerance for deformation, which is estimated to lie within 10–50 kPa in acute injury phases. This study gap highlights the need for systematic studies linking hydrogel swelling behavior and energy level to the tissue-level outcomes.

In this work, we investigated the energy dynamics of MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogels under confinement pressures spanning 10–50 kPa, a range reflective of spinal tissue tolerance through computational analysis. The computational model covered VDW adhesion energy, intramolecular elastic energy, total energy sorption, and total system energy to identify the pressure threshold for optimum adsorption kinetics at the hydrogel-tissue interface. This computational model enables a pre-emptive tuning of hydrogel dosage (volume) and swelling behavior to match lesion-specific geometries, eliminating the trial-and-error stage for better adaptability in the clinical setting.

The spinal cord has grey matter centrally and white matter peripherally. Grey matter comprises interneurons, afferent neurones, and efferent neurone fibres. White matter mostly comprises myelinated axons. The spinal cord establishes an effective conduction between the brain and peripheral nerves. Axons extend longitudinally across the spinal cord, transmitting information from the brain to peripheral nerves by efferent nerves, and relaying signals received by peripheral nerves back to the brain via afferent nerves. The spinal cord is a pliable, aqueous biological structure with rigidity varying from 3 to 300 kPa. Hydrogel, as a kind of biological nanomaterial, offers distinct benefits for spinal cord injury healing owing to its high hydrophilicity and other physical characteristics. Prior research has demonstrated that neuronal maturity was enhanced, and axonal length was increased following the use of hydrogels, rendering them more appropriate for implantation post-spinal cord injury and facilitating spinal cord tissue regeneration [37]. BIOVIA Materials Studio program facilitates the simulation and modelling of spinal cord tissues, with tissue characteristics taken from the library, incorporating structural functional functions supported by the surrounding extracellular protein matrix collagen in the connective tissue. We used the neurotransmitters acetylcholine (Ach): C7H16NO2 and gamma-aminobutyric Acid: C4H9NO3. Regarding the neuroproteins: myelin basic protein (C74H14N20O17), cholesterol (C27H46), sphingomyelin (C37H74NO6P), and hyaluronic acid (C14H21NO11) were utilized. All structures underwent geometric optimization. The program facilitated the simulation of sorption analysis at various pressures (10, 20, 30, 40, and 50 kPa), adsorption simulation, and molecular dynamics simulation, utilizing Forcite modules for the geometric optimization of each. An amorphous cell module was employed to amalgamate the component prior to the absorption and sorption examination for each designated tissue (Fig. 1).

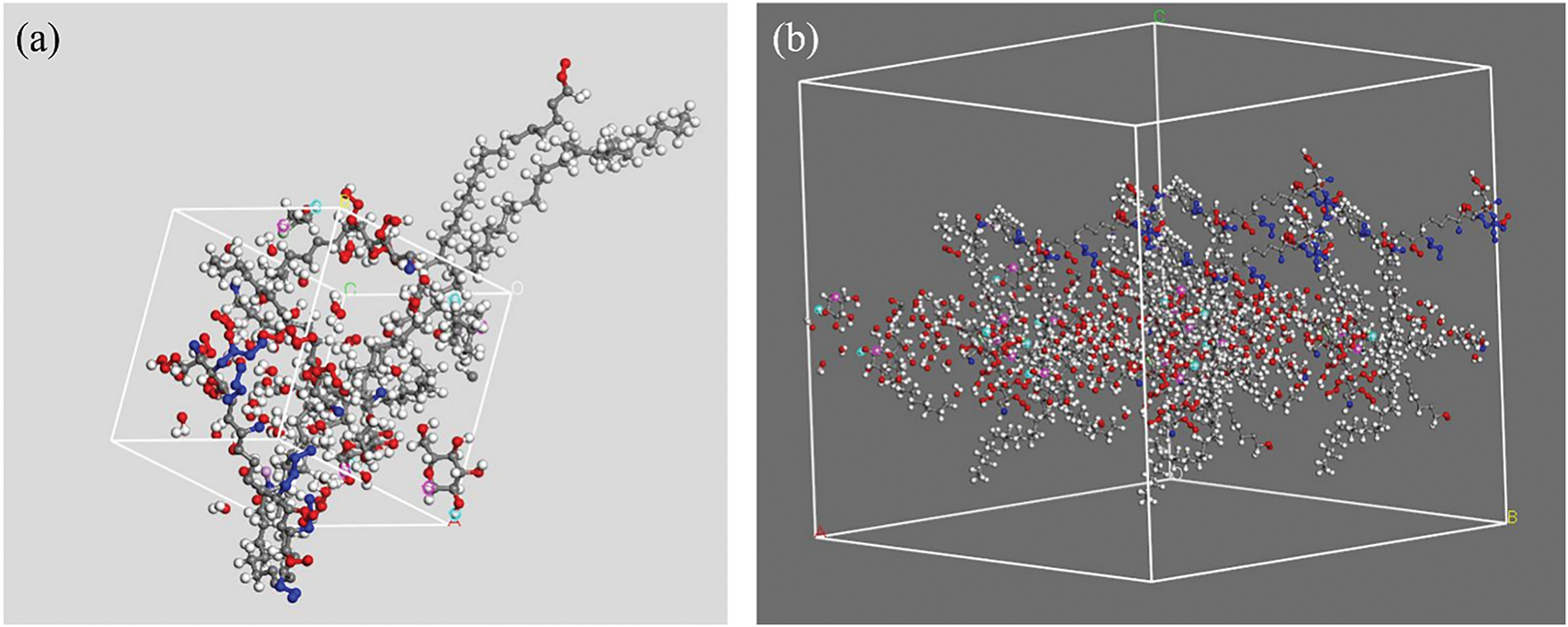

The COMPASS forcefield was selected for optimizing spinal cord tissues prior to the introduction of a universal forcefield for calculating adsorption energy. The intelligent algorithm was selected for the optimization parameters, with a convergence tolerance energy of 0.001 kcal/mol and 0.5 kcal/mol for the force interaction. The highest iteration energy is 500 psi, with an external pressure of 0 GPa. The electrostatic summation approach employed is atom-based, with a buffer width of 0.5 Å. Subsequently, for the sorption calculation and the density field. The summing technique for Van der Waals (VDW) terms is Ewald, achieving an accuracy of 0.001 kcal/mol and employing a repulsive cutoff of 12 Å. The frame charges amount to 1368.00 per cell, with a maximum adsorption distance of 10.00 Å. Fig. 2 illustrates the architecture of each cell and molecule. The length of the simulation is contingent upon the quantities of the participating molecules. The sorption energy locator was computed utilizing the COMPASS force field, employing the summation techniques of electrostatics Ewald and atom-based VDW force to integrate the structure Minimization of energy inside the system to get a stable configuration. This stage guarantees the equilibrium of molecular forces VDW force, electrostatic, and intramolecular energy) and eliminates any initial strain or distortion in the tissue or hydrogel model. The structural and electrical properties of the hydrogel and spinal tissue were examined following the construction of the amorphous structure, with five [5] pressures ranging from 10 to 50 kPa selected to assess the integration of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles and hydrogel in the proper distribution and alignment of the spinal cord, as well as the activation of neural circuits (Fig. 2a). The adsorbate was introduced into the vacuum slab (Fig. 2b), and the target atoms were designated.

Figure 2: (a) The structural formation of the spinal cord tissue in amorphous structure, (b) Spinal cord tissue formation in vacuum slab

The computational model utilized BIOVIA Materials Studio to simulate spinal cord tissue by constructing an amorphous cell composed of neurotransmitters acetylcholine (C7H16NO2) and gamma-aminobutyric acid (C4H9NO3) alongside neuroproteins including myelin basic protein, cholesterol, sphingomyelin, and hyaluronic acid. These components were selected for their physiological relevance to neural signaling and tissue structure. Geometric optimization was conducted using the Forcite module with the COMPASS forcefield to ensure structural stability, followed by simulations of adsorption and sorption at pressures from 10 to 50 kPa. An atom-based electrostatic summation and Ewald method for VDW interactions were employed to enhance accuracy. The intelligent algorithm guided parameter optimization with stringent convergence criteria. The integration of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles within the hydrogel-spinal tissue matrix was also simulated to examine molecular distribution and neural activation potential. This modeling approach ensured a realistic representation of spinal cord environments, emphasizing the role of extracellular matrices and molecular interactions critical for neural function and tissue engineering applications.

Neurons are electrically excitable cells that generate action potentials. These electrical signals are initiated by a depolarization of the transmembrane potential, approximately 15 mV across the lipid bilayer. The depolarization is mediated by gradient-driven ion influx (Na+, K+, Cl−) rather than a purely electrical mechanism. Research indicates that electrical stimulation enhances axonal regeneration by creating an extracellular electric field that guides cellular behaviors like charged molecule transport and directional cell migration. However, if a conductive hydrogel is improperly fitted to the lesion site, it may fail to sustain the spatially controlled electric field required for these therapeutic effects, thereby hindering regeneration. Therefore, in this study, we focus on optimizing the hydrogel-spinal tissue interface. We applied varied pressures (10–50 kPa) to ensure the hydrogel fills the lesion volume without overfilling (risking mechanical compression) or underfilling (creating resistive gaps). Interfacial compatibility is analyzed through adsorption energy studies to evaluate the adhesion and conformability of MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogel with the native spinal tissues, which ultimately influence electrical and biomechanical performance.

3.1 Adsorption Analysis of the Spinal Cord Tissues

The adsorption of MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogel onto spinal cord tissues is a sophisticated method in spinal cord restoration, integrating materials science with biological tissue engineering. In this context, hydrogels and MgFe2O4 nanoparticles are essential for the transmission and delivery of electrical impulses that govern critical biological processes, including cell shape, migration, differentiation, and tissue regeneration.

Hydrogels are aqueous, biocompatible substances that replicate the natural extracellular matrix, offering an appropriate framework for cellular adhesion, proliferation, and migration. In spinal cord repair, hydrogels were injected with nanoparticles (MgFe2O4), which possess magnetic and electrical conductivity, hence facilitating their crucial function in electrical signal transmission. MgFe2O4 nanoparticles, characterized by their elevated surface area and magnetic attributes, stick to spinal cord tissues and may be accurately maneuvered using external magnetic fields, facilitating localized and targeted transmission of electrical impulses.

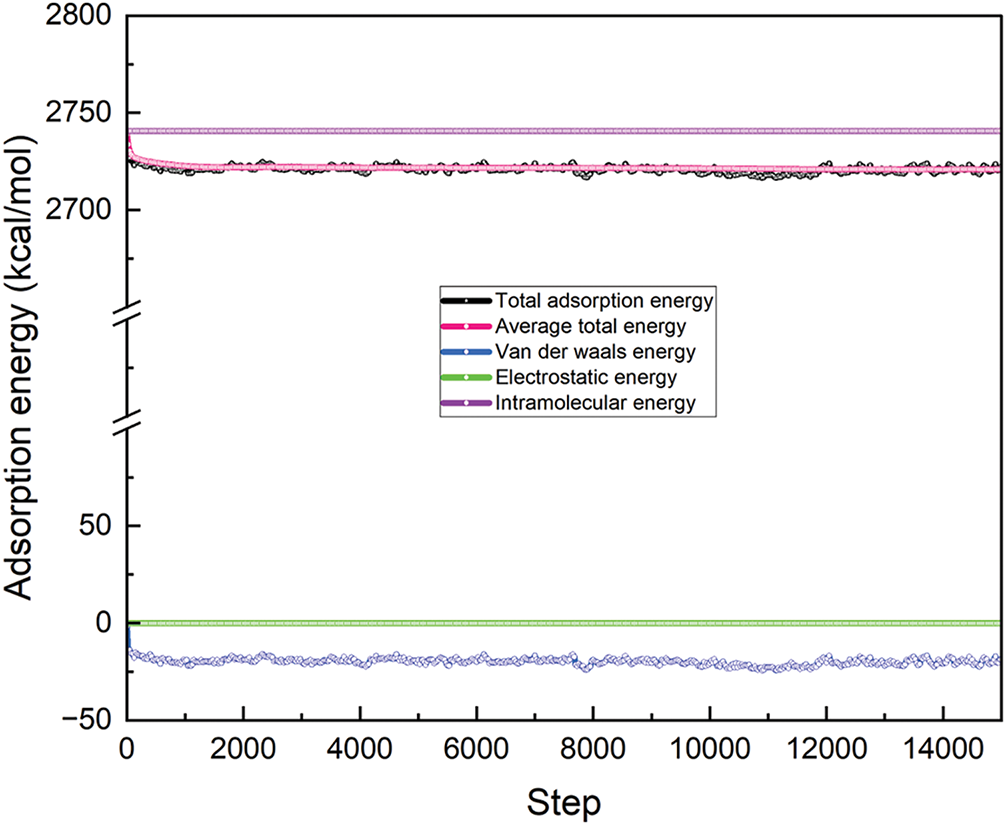

The adsorption of these nanoparticles onto spinal cord tissues, enabled by the hydrogel matrix, is essential for the regulated release of electrical impulses. Adsorption is the adherence of nanoparticles to the surface of spinal cord cells or tissues. This connection is influenced by several factors, including VDW forces, electrostatic interactions, and perhaps particular chemical recognition between nanoparticles and cellular components. Fig. 3 illustrates the adsorption configuration of the hydrogel infused with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles on spinal cord tissues, with an adsorption distance of 20.180 Å. This indicates the alignment of the magnetically infused hydrogel on the surface of spinal cord stem cells. The cumulative adsorption energy was 2740.42 kcal/mol, indicating the overall stability of the nanoparticle-hydrogel-tissue interaction, as seen in Fig. 4. A substantial overall adsorption energy signifies robust and sustained adhesion between the MgFe2O4 nanoparticles and spinal cord tissues. This stability is essential for maintaining the nanoparticles at the damage site, allowing them to deliver their biological effects without being prematurely eliminated by the body.

Figure 3: Adsorption configuration of spinal cord tissues with MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogel

Figure 4: The energy configuration of MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogel on the spinal cord tissues

The VDW energy measured −20.147 kcal/mol (Fig. 4), indicating the non-covalent interaction between the nanoparticles and spinal cord tissue. VDW forces are feeble, short-range interactions that facilitate the preliminary adherence of nanoparticles to tissue. Although these forces are weaker than covalent connections, they play a crucial role in keeping the nanoparticles close to the tissue, ensuring their localization at the damage site and facilitating the sustained delivery of their bioactive effects.

The negative VDW energy indicates that this interaction is advantageous, facilitating adsorption while preserving the integrity of the tissue structure. The intramolecular energy of the MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogel was determined to be 2740.709 kcal/mol, reflecting the internal energy of the system, which encompasses the interactions between the nanoparticles and the hydrogel matrix. This energy enhances the structural integrity and stability of the hydrogel-nanoparticle combination. A high intramolecular energy signifies that the nanoparticles are effectively integrated into the hydrogel, facilitating the regulated release of electrical impulses. This is especially crucial for guiding cellular behavior throughout the healing process, including the regulation of cell shape, migration, and differentiation.

The integration of the hydrogel matrix with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles can markedly affect cellular behavior in the damaged spinal cord. When incorporated into the conductive hydrogel matrix, the nanoparticles facilitate the transmission of electrical impulses, which in turn activate brain cells and promote their migration toward the damaged site. This is essential for cellular healing, since it promotes the migration of neural stem cells, glial cells, and neurons, fostering tissue regeneration and perhaps closing the damage gap. Furthermore, electrical impulses impact cell shape by influencing the development and orientation of nerve cells along the damaged spinal cord, directing them into functional configurations essential for the restoration of neural networks. Electrical stimulation is crucial in cell differentiation, especially in the transformation of neural stem cells into neurons, oligodendrocytes, or astrocytes, contingent upon the unique requirements of the injury site.

In summary, the adsorption of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles onto spinal cord tissues, enabled by the hydrogel scaffold, establishes a stable and regulated environment for the conveyance of electrical impulses. These signals are essential in the healing process by affecting cellular shape, migration, and differentiation, so facilitating the regeneration of spinal cord tissue. The elevated total adsorption energy and advantageous interactions between the nanoparticles and tissue augment the stability and efficacy of this method, presenting significant promise for spinal cord injury therapies.

3.2 Sorption Analysis of the Spinal Cord Tissues

Hydrogel is a biocompatible, water-imbued polymeric substance capable of retaining substantial quantities of water inside its matrix. The composite, when integrated with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles, a ferrite-based material, may provide improved mechanical characteristics and electrical conductivity. The hydrogels’ moisture retention capacity and the magnetic characteristics of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles provide synergistic effects for spinal cord regeneration. MgFe2O4 nanoparticles exhibit bioactivity and facilitate electrical signal transmission, a critical role for spinal cord tissue regeneration. The spinal cord tissues are contingent upon their affinity for certain molecules and their capacity to cling to tissue surfaces. The cumulative sorption energy, VDW energy, and intramolecular energy provide insights into the interactions between the hydrogel, nanoparticles, and spinal cord tissues at various levels.

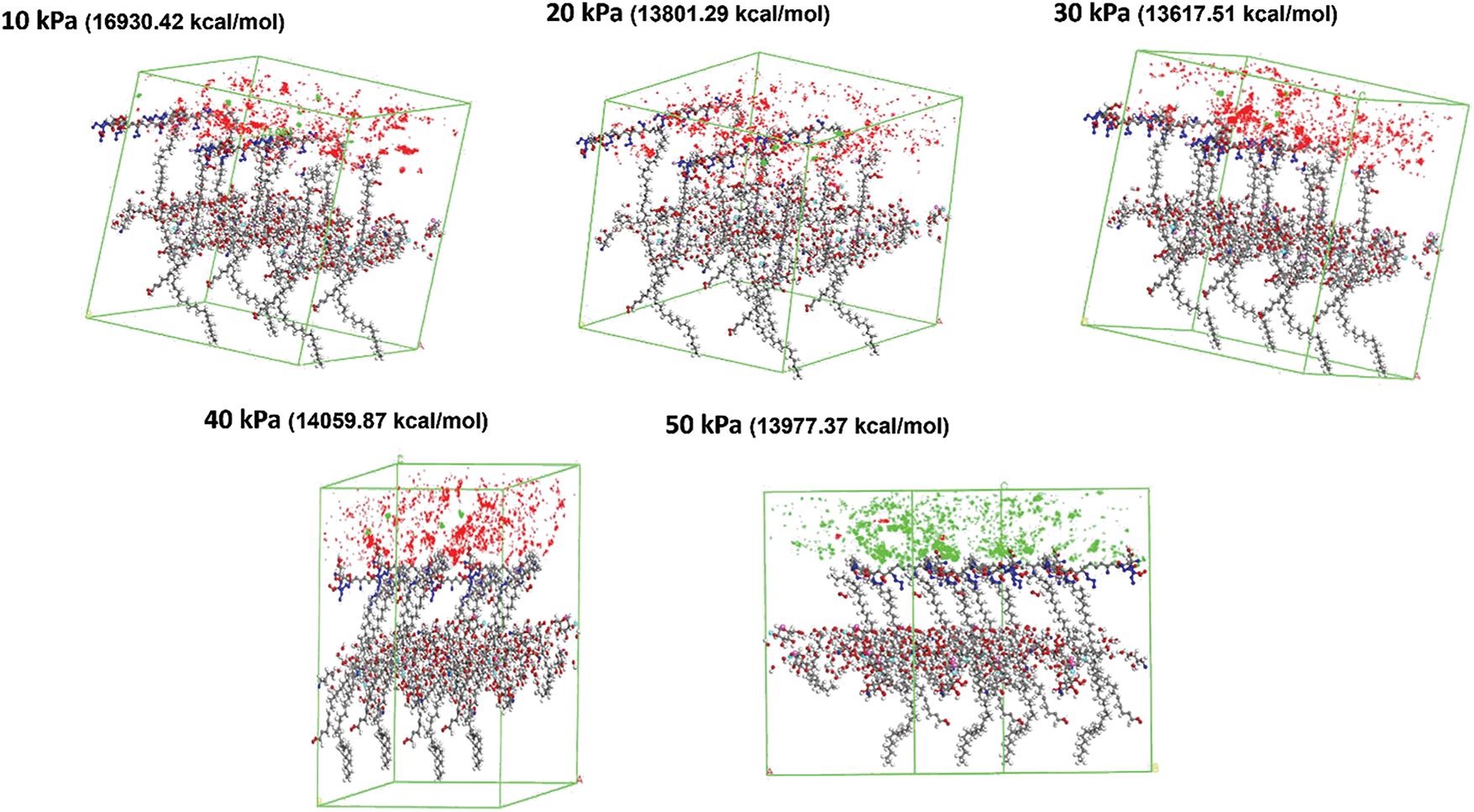

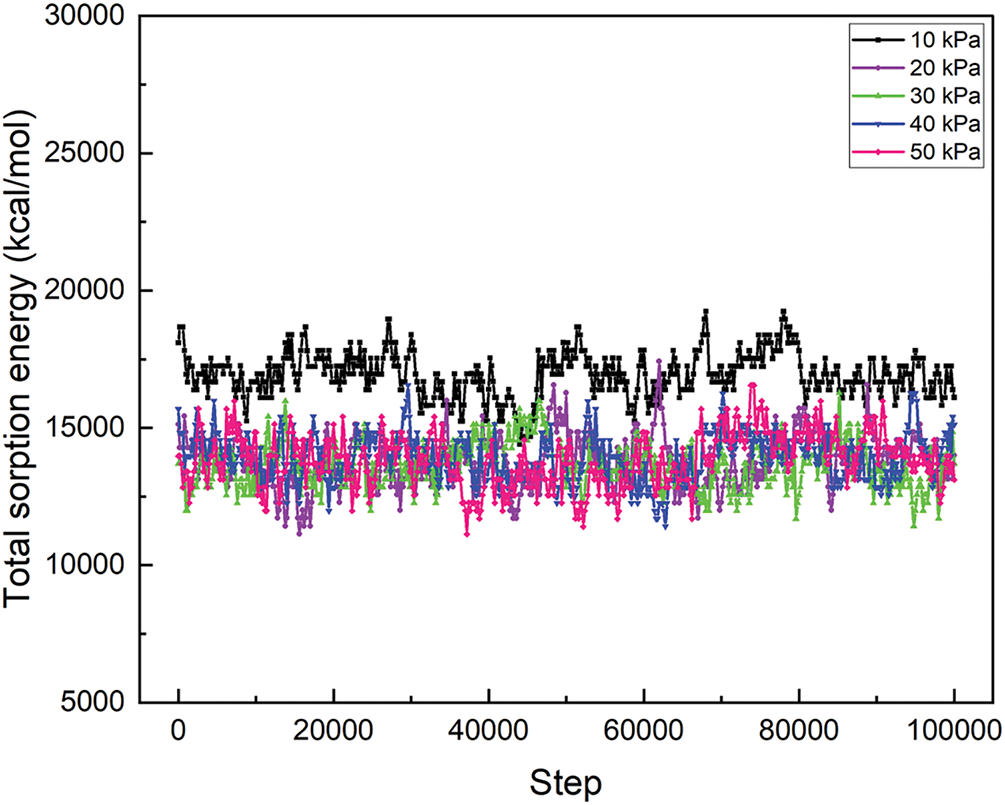

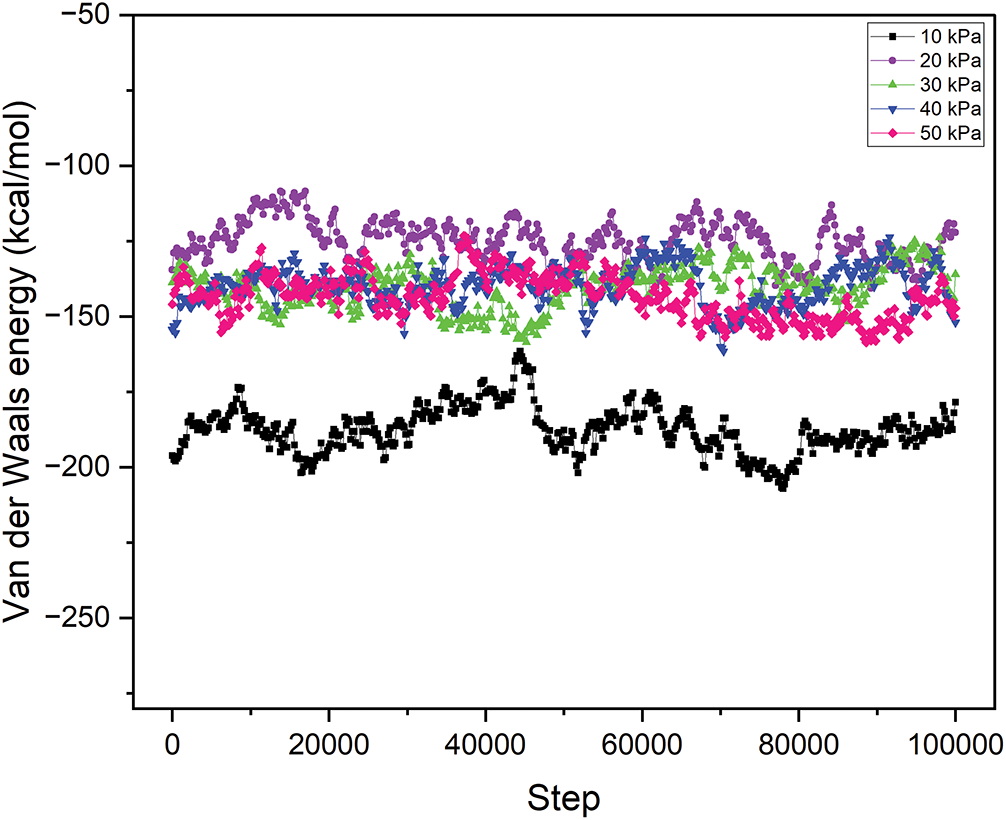

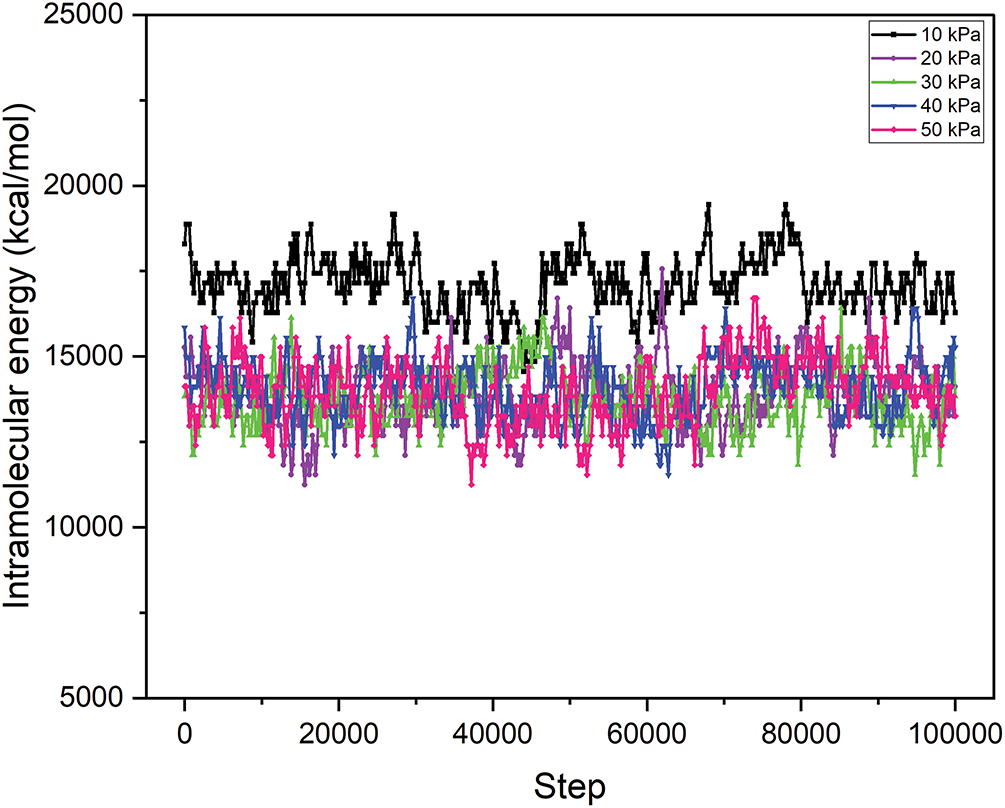

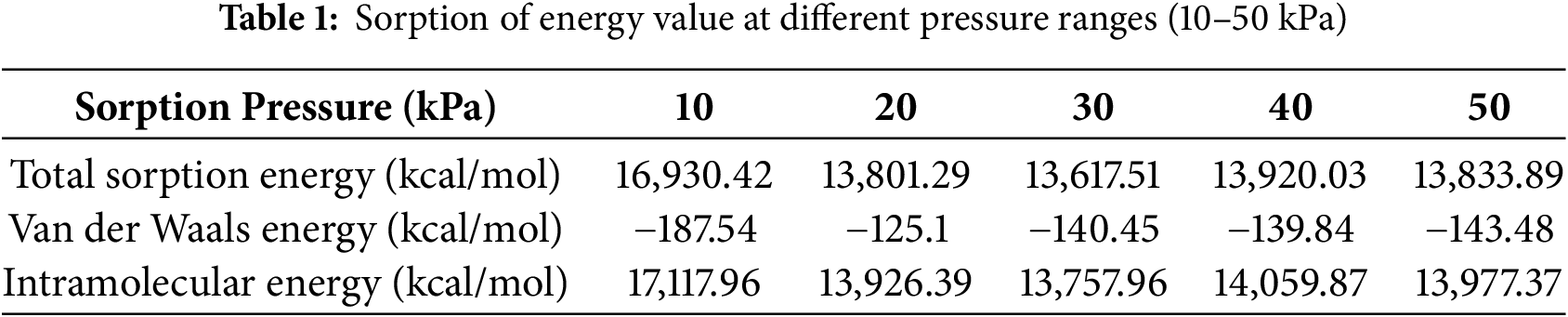

The investigation of sorption analysis of spinal cord tissues with a hydrogel matrix infused with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles under different pressure circumstances provides significant insights into the energy interactions at the interface between the tissue and the nanoparticle matrix (Fig. 5). The total energy (Fig. 6), VDW energy (Fig. 7), and intramolecular energy (Fig. 8) are crucial in the interaction of materials with biological tissues, greatly influencing the therapeutic potential and mechanical aspects of nanomaterials in SCI.

Figure 5: Sorption analysis of MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogel at different pressure from 10 to 50 kPa on the spinal tissues

Figure 6: The total sorption energy of the MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogels at different pressure from 10 to 50 kPa on the spinal tissues

Figure 7: Van der Waals energy of the MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogels at different pressures from 10 to 50 kPa on the spinal tissues

Figure 8: Intramolecular energy of the MgFe2O4-collagen hydrogels at different pressures from 10 to 50 kPa on the spinal tissues

The total energy values at different pressures reflect the entire energy interaction between spinal cord tissue and the hydrogel matrix injected with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles. At 10 kPa, the total energy reaches its pinnacle at 16,930.42 kcal/mol, thereafter diminishing to 13,801.29 kcal/mol, 13,617.51 kcal/mol, 13,920.03 kcal/mol, and 13,833.89 kcal/mol as the pressure escalates to 20, 30, 40, and 50 kPa, respectively (Fig. 6). This indicates a multifaceted link between pressure and the material’s interaction with the tissue. At reduced pressures, the material may demonstrate enhanced contact with the tissue owing to the increased total energy. This enhanced contact may lead to improved integration of the hydrogel matrix and nanoparticles inside the tissue, thus facilitating the repair of SCI. The drop in total energy with rising pressure may indicate less tissue engagement at elevated pressures, perhaps rendering the material less effective for biological healing processes. Consequently, optimizing pressure is essential to equilibrate tissue healing efficacy and material characteristics.

The VDW energy, indicative of non-covalent contact forces between molecules, has a negative correlation with increasing pressure. At 10 kPa, the VDW energy is −187.54, and it gets less negative with increasing pressure, attaining −143.48 at 50 kPa (Fig. 6). This indicates that the attraction forces between the MgFe2O4 nanoparticles and the spinal cord tissue diminish at elevated pressures. VDW forces are crucial for facilitating effective adhesion and contact between the tissue and the hydrogel matrix, with a greater negative value often signifying stronger interactions. At reduced pressures, the enhanced VDW forces provide superior adherence of nanoparticles to the tissue surface, perhaps resulting in more efficient integration of the nanomaterial into the tissue, hence improving the healing process. As pressure escalates, the attenuation of these forces may lead to less engagement with the tissue, thereby compromising the therapeutic effectiveness of the nanomaterial in addressing spinal cord injury.

Intramolecular energy denotes the energy linked to interactions within the hydrogel matrix and among the nanoparticles. At 10 kPa, the intramolecular energy is maximized at 17,117.96 kcal/mol, thereafter diminishing with increasing pressure to 13,977.37 kcal/mol at 50 kPa (Fig. 7). This pattern indicates that the material attains greater stability at reduced pressures, where internal interactions within the material are more robust. Increased intramolecular energy at reduced pressure may signify enhanced structural integrity and stiffness of the hydrogel matrix, essential for delivering the mechanical support required for spinal cord tissue healing. Conversely, when pressure escalates, the diminished intramolecular energy may lead to a less stable configuration, thereby compromising the mechanical characteristics of the hydrogel matrix. In spinal cord injury recovery, it is crucial to maintain an optimal balance of intramolecular energy, as excessive stiffness might hinder tissue regeneration, whereas insufficient stiffness may result in inadequate support for the wounded area. Table 1 illustrates the details of total energy, VDW energy, and intramolecular energy. In practical clinical settings, maintaining a low-pressure environment (10 kPa) around spinal cord injuries could be achieved through innovative implant designs, such as pressure-modulating hydrogel wraps, or microfluidic systems integrated within the scaffold. These technologies could dynamically regulate local pressure, enhancing tissue integration and repair. Clinical feasibility depends on biocompatibility, ease of implantation, and the ability to sustain stable pressure without causing additional tissue damage. Future development of minimally invasive delivery systems and pressure-monitoring devices will be crucial to translating these hydrogel-MgFe2O4 composites into viable therapies, ensuring controlled environments that maximize regenerative outcomes in spinal cord injury treatments.

The interplay of these energy components is crucial in assessing the efficacy of the hydrogel matrix containing MgFe2O4 nanoparticles for spinal cord injury treatment. At reduced pressures, elevated total and intramolecular energy values, along with increased negative VDW energy values, signify enhanced interactions between the material and the tissue (Fig. 8). This may result in enhanced tissue integration, superior healing, and more efficient regeneration of the injured spinal cord. Nevertheless, when pressure escalates, these energy components indicate a deterioration of material-tissue contact, potentially diminishing the material’s efficacy in facilitating tissue healing. Consequently, optimizing pressure conditions during the sorption process is essential for enhancing the therapeutic efficacy of this nanomaterial. The results indicate that pressures near 10 kPa may provide appropriate energy interactions for treating spinal cord tissue injuries; nevertheless, more study is necessary to adjust the pressure parameters for improved therapeutic results.

The sorption of hydrogel and MgFe2O4 nanoparticles on spinal cord tissues, analyzed by Materials Studio, elucidates their role in spinal cord restoration. The robust binding energies, in conjunction with VDW and intramolecular contacts, promote the effective transmission of electrical impulses, govern cellular activities such as migration and differentiation, and improve the overall healing process. The simulation results indicate that these materials significantly contribute to spinal cord regeneration by offering steady, localized, and regulated conditions for tissue healing.

The computational results provide valuable insights that can guide the design of effective experimental protocols for spinal cord injury (SCI) repair. The findings demonstrate that lower pressure environments, particularly around 10 kPa, enhance the stability and internal interaction energy of the MgFe3O4-collagen hydrogel composite. This suggests that experimental setups should aim to replicate low-pressure conditions to optimize hydrogel performance. The favorable van der Waals (VDW) and intramolecular energies observed indicate strong interactions between the hydrogel and tissue, which are critical for maintaining structural integrity and facilitating the transmission of electrical impulses key factors in directing cellular behavior such as migration, differentiation, and neural network formation. These results advocate for the development of pressure-modulating delivery systems, such as hydrogel wraps or implantable microfluidic scaffolds, that can maintain localized low-pressure zones at the injury site. Experimentally, this could be validated through in vivo models assessing tissue integration, electrical signal propagation, and functional recovery. Furthermore, the data can inform material formulation by guiding nanoparticle concentration and crosslinking density to achieve optimal mechanical and bioelectrical properties. Ultimately, these computational insights bridge the gap between material behavior under simulated conditions and real-world therapeutic applications, laying the foundation for translational research in SCI treatment.

The application of hydrogel matrices filled with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles for spinal cord injury (SCI) repair has significant promise in enhancing treatment approaches. Hydrogels give a biocompatible, aqueous framework for cellular functions, while the use of MgFe2O4 nanoparticles enhances the composite’s electrical conductivity and magnetic characteristics, providing a dual mechanism for facilitating tissue regeneration. The adsorption of these nanoparticles onto spinal cord tissues is essential for the localized transmission of electrical impulses that regulate critical cellular processes, including migration, differentiation, and regeneration. The strong contact among nanoparticles, hydrogel matrix, and tissue, marked by significant cumulative adsorption energy and advantageous VDW forces, guarantees stability and prolonged transmission of electrical impulses.

Simulations demonstrated a specific adsorption configuration with a distance of 20.180 Å and a total adsorption energy of 2740.42 kcal/mol, underscoring the efficacy of the hydrogel-nanoparticle interaction in preserving tissue integrity and enhancing electrical signaling. Pressure-dependent sorption experiments show that reduced pressures promote more adhesion between nanoparticles and spinal cord tissues, hence enhancing therapeutic potential. The negative VDW energy and increased intramolecular energy at reduced pressures indicate that optimum material-tissue integration occurs under these conditions, offering essential mechanical support for spinal cord healing.

MgFe2O4 nanoparticle-containing conductive hydrogels offer promising clinical applications in nerve regeneration, cardiac tissue repair, and smart wound dressings. Their magnetic responsiveness and electrical conductivity enhance cellular signaling and tissue healing, making them ideal for bioelectronic interfaces, controlled drug delivery, and dynamic tissue engineering scaffolds in regenerative therapies. This work highlights the importance of nanoparticle-hydrogel composites in spinal cord regeneration, indicating that hydrogel-MgFe2O4 nanomaterials can establish an optimal environment for tissue repair. The use of these materials into spinal cord injury therapy may enhance recovery results by improving cellular behaviors, increasing migration and differentiation, and aiding tissue regeneration. Further investigation is necessary to refine the pressure parameters for optimal material efficacy and to examine the long-term implications of these nanoparticles in vivo. This unique technique may provide enhanced therapies for spinal cord injuries and other neural tissue abnormalities, providing new prospects for regenerative medicine.

Acknowledgement: The authors appreciate Atomic and Radiation Physics Lab for providing the Material studio software.

Funding Statement: The authors express their appreciation to the “Young Talent Research Grant”: (600-RMC/YTR/5/3(004/2022) Universiti Teknologi Mara (UiTM) for providing the financial support.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization: Surajudeen Sikiru; methodology: Surajudeen Sikiru, Imandeena Sofileeya, Nur Hidayah Shahemi; software: Surajudeen Sikiru, Imandeena Sofileeya; validation: Surajudeen Sikiru; formal analysis: Surajudeen Sikiru, Nur Hidayah Shahemi, Niraj Kumar, Mohd Muzamir Mahat; investigation: Imandeena Sofileeya, Surajudeen Sikiru, Nur Hidayah Shahemi, Mohd Muzamir Mahat; resources: Surajudeen Sikiru; data curation: Surajudeen Sikiru; writing—original draft preparation: Surajudeen Sikiru, Imandeena Sofileeya; writing—review and editing: Imandeena Sofileeya, Surajudeen Sikiru, Nur Hidayah Shahemi, Niraj Kumar, Mohd Muzamir Mahat; visualization: Surajudeen Sikiru; supervision: Surajudeen Sikiru, Mohd Muzamir Mahat; project administration: Surajudeen Sikiru, Nur Hidayah Shahemi; funding acquisition: Mohd Muzamir Mahat. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Figure A1: The example of an injectable conductive hydrogel infused with magnetic nanoparticles fabricated in our lab

References

1. Seo HS, Wang CPJ, Park W, Park CG. Short review on advances in hydrogel-based drug delivery strategies for cancer immunotherapy. Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2022;19(2):263–80. doi:10.1007/s13770-021-00369-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Min Q, Yu X, Liu J, Zhang Y, Wan Y, Wu J. Controlled delivery of insulin-like growth factor-1 from bioactive glass-incorporated alginate-poloxamer/silk fibroin hydrogels. Pharmaceutics. 2020;12(6):574. doi:10.3390/pharmaceutics12060574. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Daou F, Cochis A, Leigheb M, Rimondini L. Current advances in the regeneration of degenerated articular cartilage: a literature review on tissue engineering and its recent clinical translation. Materials. 2021;15(1):31. doi:10.3390/ma15010031. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Banik S, Kumar H, Ganapathy N, Swaminathan R. Exploring central-peripheral nervous system interaction through multimodal biosignals: a systematic review. IEEE Sens Lett. 2024;8(8):1–4. doi:10.1109/access.2024.3394036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Luís AM. Simulating peripheral nerve stimulation [master’s thesis]. Lisbon, Portugal: Universidade NOVA de Lisboa; 2022. [Google Scholar]

6. Navarro X, Krueger TB, Lago N, Micera S, Stieglitz T, Dario P. A critical review of interfaces with the peripheral nervous system for the control of neuroprostheses and hybrid bionic systems. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2005;10(3):229–58. doi:10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.10303.x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Casey G. Electricity in the brain. Kai Tiaki Nurs New Zealand. 2015;21(3):20–4. [Google Scholar]

8. Zhang ZC, Sun TS. Repair, protection and regeneration of spinal cord injury. Neural Regen Res. 2015;10(12):1953–75. [Google Scholar]

9. Jack AS, Hurd C, Martin J, Fouad K. Electrical stimulation as a tool to promote plasticity of the injured spinal cord. J Neurotrauma. 2020;37(18):1933–53. doi:10.1089/neu.2020.7033. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Quadri SA, Farooqui M, Ikram A, Zafar A, Khan MA, Suriya SS, et al. Recent update on basic mechanisms of spinal cord injury. Neurosurg Rev. 2020;43(2):425–41. doi:10.1007/s10143-018-1008-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Ahuja CS, Fehlings M. Spinal cord injury. In: Ellenbogen R, Sekhar L, Kitchen N, da Silva HB, editors. Principles of neurological surgery. 4th ed. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier; 2018. p. 518–31. doi:10.1016/b978-0-323-43140-8.00033-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Venkatesh K, Ghosh SK, Mullick M, Manivasagam G, Sen D. Spinal cord injury: pathophysiology, treatment strategies, associated challenges, and future implications. Cell Tissue Res. 2019;377(2):125–51. doi:10.1007/s00441-019-03039-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Tao J, Zhou J, Xu L, Yang J, Mu X, Fan X. Conductive, injectable hydrogel equipped with tetramethylpyrazine regulates ferritinophagy and promotes spinal cord injury repair. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;283(6):137887. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.137887. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Yao S, Yang Y, Li C, Yang K, Song X, Li C, et al. Axon-like aligned conductive CNT/GelMA hydrogel fibers combined with electrical stimulation for spinal cord injury recovery. Bioact Mater. 2024;35(4):534–48. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2024.01.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Hasanzadeh E, Seifalian A, Mellati A, Saremi J, Asadpour S, Enderami SE, et al. Injectable hydrogels in central nervous system: unique and novel platforms for promoting extracellular matrix remodeling and tissue engineering. Mater Today Bio. 2023;20:100614. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2023.100614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Fan P, Li S, Yang J, Yang K, Wu P, Dong Q, et al. Injectable, self-healing hyaluronic acid-based hydrogels for spinal cord injury repair. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;263:130333. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.130333. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Wang P, Chen Z, Li P, Al Mamun A, Ning S, Zhang J, et al. Multi-targeted nanogel drug delivery system alleviates neuroinflammation and promotes spinal cord injury repair. Mater Today Bio. 2025;31:101518. doi:10.1016/j.mtbio.2025.101518. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Wang H, Zhang H, Xie Z, Chen K, Ma M, Huang Y, et al. Injectable hydrogels for spinal cord injury repair. Eng Regen. 2022;3(4):407–19. [Google Scholar]

19. Hu X, Xu W, Ren Y, Wang Z, He X, Huang R, et al. Spinal cord injury: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic interventions. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):245. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01477-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Nishida N, Sakuramoto I, Fujii Y, Hutama RY, Jiang F, Ohgi J, et al. Tensile mechanical analysis of anisotropy and velocity dependence of the spinal cord white matter: a biomechanical study. Neural Regen Res. 2021;16(12):2557–62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

21. Yang YT, Zhu SJ, Xu ML, Zheng LD, Cao YT, Yuan Q, et al. The biomechanical effect of different types of ossification of the ligamentum flavum on the spinal cord during cervical dynamic activities. Med Eng Phys. 2023;121:104062. doi:10.1016/j.medengphy.2023.104062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Scott J, Belden JB, Minghetti M. Applications of the RTgill-W1 cell line for acute whole-effluent toxicity testing: in vitro–in vivo correlation and optimization of exposure conditions. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2021;40(4):1050–61. doi:10.1002/etc.4947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Kheram N, Bessen MA, Jones CF, Davies BM, Kotter M, Farshad M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid pressure dynamics as a biomechanical marker for quantification of spinal cord compression: conceptual framework and systematic review of clinical trials. Brain Spine. 2025;5(1):104211. doi:10.1016/j.bas.2025.104211. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Prager J, Adams CF, Delaney AM, Chanoit G, Tarlton JF, Wong LF, et al. Stiffness-matched biomaterial implants for cell delivery: clinical, intraoperative ultrasound elastography provides a ‘target’ stiffness for hydrogel synthesis in spinal cord injury. J Tissue Eng. 2020;11(3):2041731420934806. doi:10.1177/2041731420934806. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Liu L, Chen S, Song Y, Cui L, Chen Y, Xia J, et al. Hydrogels empowered mesenchymal stem cells and the derived exosomes for regenerative medicine in age-related musculoskeletal diseases. Pharmacol Res. 2025;213:107618. doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2025.107618. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Zhou L, Fan L, Yi X, Zhou Z, Liu C, Fu R, et al. Soft conducting polymer hydrogels cross-linked and doped by tannic acid for spinal cord injury repair. ACS Nano. 2018;12(11):10957–67. doi:10.1021/acsnano.8b04609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Peng W, Li D, Dai K, Wang Y, Song P, Li H, et al. Recent progress of collagen, chitosan, alginate and other hydrogels in skin repair and wound dressing applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;208(8):400–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.03.002. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Liu H, Feng Y, Che S, Guan L, Yang X, Zhao Y, et al. An electroconductive hydrogel scaffold with injectability and biodegradability to manipulate neural stem cells for enhancing spinal cord injury repair. Biomacromolecules. 2022;24(1):86–97. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.2c00920. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Shahemi NH, Mahat MM, Asri NAN, Amir MA, Ab Rahim S, Kasri MA. Application of conductive hydrogels on spinal cord injury repair: a review. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2023;9(7):4045–85. doi:10.1021/acsbiomaterials.3c00194. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Ohm Y, Pan C, Ford MJ, Huang X, Liao J, Majidi C. An electrically conductive silver–polyacrylamide–alginate hydrogel composite for soft electronics. Nat Electron. 2021;4(3):185–92. doi:10.1038/s41928-021-00545-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Al-Rawi NN, Anwer BA, Al-Rawi NH, Uthman AT, Ahmed IS. Magnetism in drug delivery: the marvels of iron oxides and substituted ferrites nanoparticles. Saudi Pharm J. 2020;28(7):876–87. doi:10.1016/j.jsps.2020.05.003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Fang K, Zhang Y, Yin J, Yang T, Li K, Wei L, et al. Hydrogel beads based on carboxymethyl cassava starch/alginate enriched with MgFe2O4 nanoparticles for controlling drug release. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;220(16):573–88. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.08.081. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Wu C, Tu J, Tian C, Geng J, Lin Z, Dang Z. Defective magnesium ferrite nano-platelets for the adsorption of As (Vthe role of surface hydroxyl groups. Environ Pollut. 2018;235(6):11–9. doi:10.1016/j.envpol.2017.12.050. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Bentarhlia N, Elansary M, Belaiche M, Mouhib Y, Lemine O, Zaher H, et al. Evaluating of novel Mn–Mg–Co ferrite nanoparticles for biomedical applications: from synthesis to biological activities. Ceram Int. 2023;49(24):40421–34. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2023.10.017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Alghamdi N, Stroud J, Przybylski M, Żukrowski J, Hernandez AC, Brown JM, et al. Structural, magnetic and toxicity studies of ferrite particles employed as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging thermometry. J Magn Magn Mater. 2020;497(18):165981. doi:10.1016/j.jmmm.2019.165981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Kumar J, Bhushan G. Dynamic analysis of quarter car model with semi-active suspension based on combination of magneto-rheological materials. Int J Dyn Control. 2023;11(2):482–90. doi:10.1007/s40435-022-01024-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Sun Z, Zhu D, Zhao H, Liu J, He P, Luan X, et al. Recent advance in bioactive hydrogels for repairing spinal cord injury: material design, biofunctional regulation, and applications. J Nanobiotechnology. 2023;21(1):238. doi:10.1186/s12951-023-01996-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools