Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

The Impact of Caulerpa lentillifera Seaweed-Based Coatings on Physicochemical Characteristics and Shelf Longevity of Fruits and Vegetables

1 Faculty of Food Science and Nutrition, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Kota Kinabalu, 88400, Sabah, Malaysia

2 Faculty of Sustainable Agriculture, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Locked Bag No. 3, Sandakan, 90509, Sabah, Malaysia

3 Higher Institution Centres of Excellence (HICoE), Borneo Marine Research Institute, Universiti Malaysia Sabah, Jalan UMS, Kota Kinabalu, 88400, Sabah, Malaysia

4 Food Science and Technology Department, Faculty of Agriculture, Warmadewa University, Kota Denpasar, 80239, Bali, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Kobun Rovina. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Smart Polymeric Materials for Sustainable Energy Solutions: Bridging Advances in Energy and Biomedical Applications)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 853-871. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.066751

Received 16 April 2025; Accepted 11 September 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Food breakdown during storage and transit greatly adds to worldwide food waste. Biodegradable edible coatings derived from natural sources provide a sustainable method to extend the shelf life and preserve the freshness of fresh fruit. This study explores the potential of the readily available and nutrient-rich seaweed, Caulerpa lentillifera, as a base material for edible coatings that can enhance the shelf life and maintain the physicochemical properties of fruits and vegetables. Caulerpa lentillifera, a marine macroalga renowned for its unique biochemical composition, presents a promising avenue for developing sustainable bio-coatings to improve the post-harvest quality of fresh produce. Biodegradable edible coatings derived from natural sources provide a sustainable method to extend the shelf life and preserve the freshness of fresh fruit. This study is aimed at exploring the potential of Caulerpa lentillifera, a nutrient-dense green seaweed, as a foundational material for creating edible coatings to enhance the post-harvest quality of fruits and vegetables. Various Caulerpa lentillifera-derived coating formulations were developed and applied to specific fruits and vegetables. The coated samples were maintained under controlled conditions and assessed for alterations in physicochemical parameters, including weight loss, hardness, colour, and microbial proliferation. The optimised coating formulation markedly diminished weight loss, postponed ripening, and maintained firmness and colour relative to uncoated controls. The coating demonstrated promising antibacterial properties, aiding in the extension of shelf life. Coatings derived from Caulerpa lentillifera offer a viable, environmentally sustainable alternative to synthetic preservatives, facilitating the advancement of sustainable food preservation technology.Keywords

Fresh fruits and vegetables are extremely perishable goods, and their swift decline after harvest greatly contributes to worldwide food waste. Researchers have increasingly concentrated on formulating effective preservation technologies to prolong the shelf life of fresh produce, so ensuring food security, minimising waste, and preserving nutritional content [1]. Conventional preservation methods, such as refrigeration, modified atmosphere packaging, and the use of synthetic chemical treatments, have limitations in terms of cost, environmental impact, and potential health concerns [2]. Consequently, there is an increasing interest in natural, biodegradable, and eco-friendly alternatives, such as edible coatings, that conform to sustainable food packaging guidelines [3]. One technique involves the use of edible coatings, which are thin, consumable layers placed directly to the surfaces of fruits and vegetables. These coatings serve as semi-permeable barriers that control moisture loss, gas exchange, and microbial contamination, thus delaying spoilage and preserving product quality [4]. Polysaccharide-based coatings have demonstrated their effectiveness in maintaining the freshness of produce, thereby prolonging their shelf life [5]. Common polysaccharide-based materials encompass alginate, carrageenan, chitosan, and starch, recognised for their efficacy in forming protective barriers and functioning as carriers for antibacterial and antioxidant compounds [6]. In recent years, polysaccharides produced from seaweed have emerged as viable materials for edible coatings. Their inherent abundance, biodegradability, and functional attributes render them ideal candidates for the development of sustainable coatings. Furthermore, the increasing awareness of plastic pollution and the necessity for better food preservation methods bolster the transition to edible coatings as feasible, environmentally sustainable substitutes for traditional plastic packaging [7,8]. Edible coatings represent an environmentally conscious food packaging alternative that can supplant conventional plastic packaging, thereby augmenting the product’s shelf life [9].

Among the diverse natural polymers explored for edible coatings, seaweed has garnered substantial attention due to its abundance, biodegradability, and unique biochemical profile [10]. Polysaccharides produced from seaweed, including alginate, carrageenan, and ulvan, have been extensively researched for their film-forming properties and efficacy as barriers against spoiling agents. Caulerpa lentillifera, usually referred to as sea grapes or green caviar, is distinguished among marine macroalgae for its nutritional composition and distinctive texture, positioning it as a viable option for the formulation of bio-based edible coatings. This seaweed is rich in polysaccharides, proteins, vitamins, and minerals, making it a potentially valuable source of bioactive compounds for food preservation applications. The inherent attributes of polysaccharide components, including non-toxicity, antioxidant and antimicrobial characteristics, and nutritional value, render them excellent candidates for edible films [10]. This study seeks to thoroughly assess the potential of Caulerpa lentillifera-based coatings for prolonging shelf life and preserving the physicochemical quality of fruits and vegetables, despite its application in food preservation being in its early phase.

The findings of this research are expected to provide valuable insights into the feasibility and efficacy of utilizing Caulerpa lentillifera as a sustainable coating material for preserving fresh produce. This contribution aims to advance the development of novel, environmentally-friendly food preservation technologies and promote the utilization of marine resources to enhance food security and sustainability. The application of Caulerpa lentillifera-based coatings aligns with the broader movement towards replacing plastic packaging with biodegradable alternatives, addressing the pressing environmental concerns associated with plastic waste [11]. The central objective of this study is to comprehensively assess the impact of Caulerpa lentillifera coatings on the physicochemical attributes and shelf life of fruits and vegetables, with the goal of establishing a scientific foundation for the application of this seaweed species in sustainable post-harvest preservation practices.

The study obtained Caulerpa lentillifera was recovered from the Borneo Marine Research Institute at the University of Malaysia Sabah [12]. The harvested seaweed underwent a meticulous cleaning regimen using distilled water to remove epiphytes, sediments, and other extraneous materials, adhering to stringent quality control protocols. Subsequently, the cleaned seaweed was dried in a controlled environment at 45°C until a constant weight was achieved. The dried biomass was then pulverized using an industrial grinder, resulting in a fine powder with a particle size less than 500 μm to enhance its solubility and dispersion properties in coating formulations. The seaweed powder was stored in airtight containers at −20°C to prevent degradation of bioactive compounds until further use [13].

For the analysis, the study utilized locally sourced fruits and vegetables, including tomatoes, red chili peppers, eggplants, and carrots, procured from nearby supermarkets. These samples were chosen due to their wide availability, economic importance, and sensitivity to postharvest deterioration, which would allow for a thorough assessment of the coating’s efficacy. Before coating, the fruits and vegetables were carefully sorted to ensure uniformity in size, shape, and maturity, and any samples with visible defects or injuries were excluded. The selected samples were then washed with distilled water and surface-sterilized with a 100 ppm sodium hypochlorite solution for 2 min, followed by rinsing with distilled water to remove any residual disinfectant [14].

2.2 Extraction and Characterization of Coating Material

The coating material developed from dried Caulerpa lentillifera powder by a hot water extraction technique designed to isolate polysaccharides and other hydrosoluble bioactive constituents. The desiccated seaweed biomass was initially pulverised into a fine powder (<500 μm) to enhance solubility and dispersion. The seaweed powder was maintained at −20°C in sealed containers to retain its bioactivity. The seaweed powder was combined with distilled water in a 1:20 (w/v) ratio and mechanically agitated at 60°C for 4 h for extraction. This technique enabled the dissolving of polysaccharides and other hydrophilic substances. The resultant slurry was subjected to vacuum filtering employing Whatman No. 1 filter paper to eliminate insoluble residues. For coating preparation, a portion of the dried seaweed extract was reconstituted in distilled water at 1% and 2% (w/v) concentrations. In the formulation containing lemon essential oil (LEO), 1% (v/v) food-grade lemon essential oil (provided by Sigma-Aldrich, USA) was used. According to supplier specifications and literature, the LEO consisted primarily of limonene (\~70%), β-pinene (\~10%), and γ-terpinene (\~8%). The mixture was homogenized using an ultrasonic bath at 50°C for 30 min to ensure uniform dispersion. The final solution was cooled to room temperature, centrifuged at 7500 rpm for 20 min at 4°C, and filtered. The resulting seaweed-based extract and SE + LEO coating solutions were used for further application [15–17].

2.3 Preparation of Coating Formulation

Two coating formulations were created utilising seaweed extract at concentrations of 1% and 2% (w/v), respectively. Lemon essential oil (LEO) was incorporated into each formulation at 1% (v/v), yielding a ratio of 99:1 (seaweed extract: LEO). The formulations were thoroughly mixed to achieve homogeneity. The assessed treatment groups comprised: (1) Control (uncoated sample), (2) 1% seaweed extract alone, (3) 2% seaweed extract alone, (4) 1% seaweed extract combined with 1% LEO, and (5) 2% seaweed extract combined with 1% LEO. Each coating solution was freshly prepared prior to application to preserve the stability of the bioactive compounds.

2.4 Evaluation of Seaweed Coating Formulation

The seaweed-based coating solutions were subjected to a series of characterization analyses to assess their physicochemical properties and functional attributes. These evaluations included the determination of pH, quantification of total phenolic compounds and flavonoids, as well as the assessment of antioxidant capacity.

2.4.1 Assessment of pH in the Coating Formulation

The pH of the coating solutions was measured using a calibrated digital pH meter at ambient temperature. Approximately 10 mL of each coating solution was placed in a beaker, and the pH meter electrodes were immersed to obtain the pH reading. The pH value for each coating solution was determined in triplicate, and the final pH was calculated as the arithmetic mean of the three measurements. The pH meter was calibrated with standard buffer solutions of pH 4.0, 7.0, and 10.0 before the measurements were taken [18].

2.4.2 Quantification of Total Phenolic Compounds

The total phenolic content of the coating solution was quantified using the Folin-Ciocalteu colorimetric method [19]. Briefly, 1.0 mL of the sample was combined with 2.25 mL of diluted Folin–Ciocalteu reagent and allowed to react at ambient temperature for 5 min. Afterwards, 2.25 mL of 7% sodium carbonate solution was added to the mixture, which was incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. A UV-Vis spectrophotometer was employed to measure absorbance at 765 nm. The TPC was calculated using a gallic acid calibration curve and expressed as milligrammes of gallic acid equivalents (mg GAE) per gram of sample [19].

2.4.3 Quantification of Flavonoid Levels

An aluminium chloride colorimetric method was employed to evaluate the total flavonoid content (TFC). A 0.5 mL aliquot of the sample was combined with 2 mL of distilled water and 0.15 mL of 5% sodium nitrite. 0.15 mL of 10% aluminium chloride solution was added after 6 min. 1 mL of 1 M sodium hydroxide was added after an additional 5 min, and the volume was subsequently adjusted to 5 mL with distilled water. The absorbance was measured at 510 nm after the solution was thoroughly mixed. The results were expressed as milligrammes of rutin equivalents (mg RE) per gramme of sample, and a rutin calibration curve was established [20].

2.4.4 Evaluation of Antioxidant Capacity

The antioxidant capacity of the seaweed coating solutions was evaluated using the DPPH radical scavenging assay. A volume of 0.1 mL of the coating solution was reacted with 3.9 mL of a 0.1 mM DPPH solution in methanol. The reaction mixture was incubated in the dark at room temperature for 30 min. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a spectrophotometer. Butylated Hydroxyanisole and Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid served as positive controls, while the extracts exhibited DPPH values in the range of 53.96% to 64.96%, consistently lower than the positive control [21]. The seaweed-based coating solutions were further characterized by evaluating their total phenolic content using the Folin-Ciocalteu method [22]. Additionally, the antioxidant activities were assessed using various methods, including the DPPH assay [23,24]. The antioxidant activity was then quantified by measuring the absorbance at 517 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer, and the results were calculated according to the equation reported in the literature [25].

where, A0 is the absorbance of the control and As is the absorbance of the sample.

2.5 Analysis of The Effect of Coating Solution on Food Samples

The effectiveness of seaweed-based coating solutions on selected fruits and vegetables, namely tomatoes, red chilies, eggplants, and carrots, was assessed by applying different treatments: uncoated (control), coated with 1% seaweed extract (SE), 2% SE, and 1% SE combined with 1% lemon essential oil (SE + LEO). All produce was selected for uniformity in size and ripeness and washed thoroughly with distilled water before coating. The coating was applied via the dipping method, where each sample was immersed in the respective solution for 2 min, then drained for 1 min on stainless-steel mesh trays and air-dried at room temperature (25 ± 2°C) for 30 min to allow film formation. Coating solutions were prepared fresh for each application, and the process was carried out using sterile glass beakers. Following coating, the samples were stored on perforated trays in a controlled chamber at 10 ± 1°C and 85%–90% relative humidity for 12 days. Samples were monitored at 3-day intervals for physicochemical changes to evaluate the coating’s effectiveness in preserving produce quality.

Thel changes of physical appearance in term of its firmness, size and surface of the uncoated and coated fruits and vegetables were visually inspected during day 0th, day 6th and day 12th for each of treatment groups. Also, the images of the changes in physical appearance of the food sample have been recorded to observe the changes in terms of colour, attractiveness and fresh appearance to indicate maturing and decaying process of the food sample in 12 days of storage period.

The weight loss of the coated and uncoated fruits and vegetables was quantified by measuring their initial weight on day 0, followed by subsequent measurements on days 6 and 12 of the storage period [26]. The weight loss was then calculated as a percentage of the initial weight using the following equation:

The total soluble solids content of the samples was quantified using a digital refractometer. The TSS of both the coated and uncoated fruits and vegetables were measured using the digital refractometer. Individual samples from each treatment group were crushed or ground to extract the freshly prepared juice, which was then directly applied to the clean prism of the refractometer. The TSS measurements were recorded and expressed in Brix [27].

The moisture content of the coated and uncoated fruits and vegetables was determined by measuring the weight changes between the fresh and dried samples using an oven drying process [28]. The food samples were cut into small, uniform pieces. Approximately 5 g of each sample from the treatment groups were weighed using an analytical balance. An empty, cleaned, and dried stainless steel moisture dish was weighed, and the weight was recorded. The 5-gram sample was then placed in the dish, and the combined weight was noted. The samples in the dishes were dried in a universal oven at 105°C for 24 h or until a constant weight was achieved. After drying, the dishes were cooled in a desiccator to room temperature and reweighed as W3. The moisture content was calculated using the established formula [28]:

The ascorbic acid content in the uncoated and coated fruit and vegetable samples was determined calorimetrically using 2,6-dichloroindophenol dye solutions. The juice was extracted from the coated and uncoated samples by cutting them into smaller pieces, pressing them, and filtering the juice through cheesecloth or filter paper. The analysis involved three reagents: a 2,6-dichloroindophenol dye solution prepared by dissolving 0.5 g of the sodium salt in 975 mL of distilled water, followed by the addition of 25 mL of 0.05 M phosphate buffer adjusted to pH 7.0; a 1% oxalic acid solution prepared by dissolving 10 g of oxalic acid dihydrate in 1 L of water; and a 0.1 mg/mL ascorbic acid standard solution prepared by accurately weighing 50 mg of ascorbic acid and dissolving it in 500 mL of the 1% oxalic acid solution. The procedure began with the standardization of the 2,6-dichloroindophenol dye, which involved titrating 2 mL of the dye solution with the standard ascorbic acid solution until the red color disappeared. The endpoint was clearly observed using a white background. The amount of ascorbic acid oxidized was calculated based on the relationship where 2 mL of dye corresponds to the volume of ascorbic acid used multiplied by 0.1 mg/mL, as the reaction involved the oxidation of ascorbic acid and the reduction of the dye colour. For the analysis of the actual samples, the juice from each fruit and vegetable was obtained, and approximately 5 mL of the juice was pipetted into a 50 mL volumetric flask, diluted to the mark with the 1% oxalic acid solution, and transferred to a burette. Then, 2 mL of the dye solution in a beaker was titrated with the juice solution until the red color disappeared. The volume required to decolorize the dye reflects the ascorbic acid content, which was calculated using the standardized relationship [29].

The experimental data were analysed statistically using one-way analysis of variance to evaluate the significant differences among the treatment groups [30]. Each analysis was performed in triplicate, and the results were reported as the mean ± standard deviation. The IBM SPSS 29.0 software for Windows was employed to determine the significant differences in the effect of the coating solutions on the coated and uncoated samples, utilizing one-way Analysis of Variance with a 95% confidence level.

3.1 Physicochemical Characteristics of the Seaweed-Based Coating

The seaweed extract from Caulerpa lentillifera was prepared to form a coating solution, and its physicochemical properties were analysed to understand its potential as a natural edible coating.

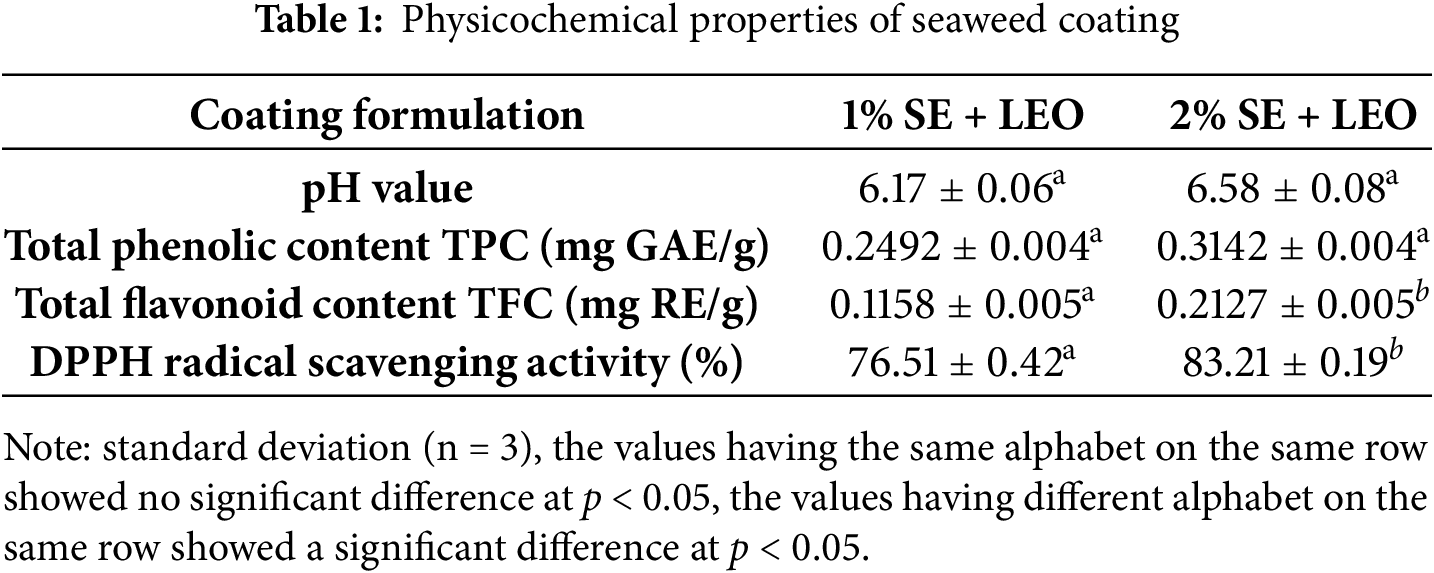

The pH of the Caulerpa lentillifera extract was measured to assess its acidity or alkalinity, which is a critical factor for maintaining food quality and safety. Table 1 shows the 1% SE + LEO coating had lower pH than 2% SE + LEO (6.58 ± 0.08). The pH value influences the antimicrobial activity, enzymatic reactions, and overall stability of the coating [31]. High acidity can inhibit microbial growth but may also cause undesirable changes in the food’s sensory attributes. The pH measurements provide essential data for optimizing coating formulations to preserve food effectively.

3.1.2 Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The analysis of the seaweed-based coating solutions revealed that the incorporation of lemon essential oil significantly increased the total phenolic content, as shown in Table 1. This suggests a synergistic relationship between the seaweed extract and lemon essential oil, enhancing the coating’s antioxidant potential [32]. The Caulerpa lentillifera seaweed species is known to contain compounds with antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anti-cancer, and anti-diabetic properties, making it a valuable functional ingredient [33]. The higher total phenolic content in the 2% SE + LEO coating enhances its ability to prevent oxidation of food surfaces, thereby improving shelf life. The coating with a higher seaweed extract concentration exhibited a higher total phenolic content, indicating a greater antioxidant capacity. The phenolic compounds present in both the seaweed extract and lemon essential oil play a vital role in scavenging free radicals, preventing lipid oxidation, and maintaining the quality of the coated produce. The enhanced phenolic content in the combined coating solution suggests a synergistic effect between the seaweed extract and lemon essential oil, potentially providing better preservation and protection for the coated fruits and vegetables [34]. The results of the total phenolic content analysis underscore the potential of seaweed-based coatings enriched with lemon essential oil as a natural and effective preservation method for extending the shelf life and maintaining the quality of fruits and vegetables [35].

3.1.3 Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The coating solutions exhibited variations in their flavonoid content, as shown in Table 1. The 2% seaweed extract + lemon essential oil coating had a slightly higher total flavonoid concentration compared to the 1% SE + LEO formulation [36]. This difference may be attributed to the higher percentage of seaweed extract in the 2% SE + LEO coating. Flavonoids are recognized for their potent antioxidant properties and ability to effectively scavenge free radicals, which can prevent the oxidation of lipids and other compounds that contribute to food spoilage [37]. The total flavonoid content is a crucial parameter in evaluating the coating’s potential for food preservation, as it directly relates to the coating’s capacity to protect the food product from oxidative damage and extend its shelf life [37]. Consequently, coatings with a higher flavonoid content can enhance the protection and prolong the shelf life of the food product. Flavonoids are known to significantly contribute to the health-promoting attributes of various plant-based products [38], and this enhancement is achieved through their ability to reduce lipid peroxidation during storage, which underscores their importance in maintaining food quality [39]. The higher flavonoid content in the 2% SE + LEO coating suggests that this formulation may offer greater antioxidant protection and preservation benefits compared to the 1% SE + LEO coating. The use of flavonoid-rich coatings has been demonstrated to be effective in impeding adverse changes caused by lipid peroxidation during storage, further highlighting the potential benefits of the seaweed-based coating with lemon essential oil [39].

3.1.4 Evaluation of the pH and Antioxidant Capacity

The pH values of the coating formulations differed significantly between the two treatments: the 1% SE + LEO formulation had a lower pH (6.17 ± 0.06) than the 2% SE + LEO formulation (6.58 ± 0.08) as shown in Table 1. Due to its lower buffering ability, the 1% seaweed extract solution is less effective at neutralising lemon essential oil’s acidity. Citral and other oxygenated monoterpenes are slightly acidic in lemon essential oil. These substances affect pH more in the 1% SE formulation due to the lower concentration of seaweed-derived minerals and polysaccharides, which act as weak bases or pH stabilisers. The 2% SE formulation may have more buffering agents, allowing it to partially offset the acidic components of the essential oil and raise its pH. The antioxidant capacity of the coating solutions was assessed using the DPPH assay, which revealed notable variations between the two formulations. As shown in Table 1, the 2% SE + LEO solution exhibited a higher percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity compared to the 1% SE + LEO formulation. This can be attributed to the increased concentration of seaweed extract in the 2% SE + LEO coating. The DPPH assay provides a quantitative evaluation of the coating’s antioxidant potential by measuring the ability of antioxidants to neutralize free radicals. The enhanced antioxidant capacity of the 2% SE + LEO solution is likely due to the higher concentration of seaweed extract, which is a rich source of bioactive compounds, including polyphenols, flavonoids, and carotenoids [33]. These compounds play a crucial role in neutralizing free radicals, preventing lipid oxidation, and maintaining the quality of the coated produce. The results of the antioxidant capacity analysis highlight the potential of seaweed-based coatings enriched with lemon essential oil as a natural and effective preservation method for extending the shelf life and maintaining the quality of fruits and vegetables. The superior DPPH radical scavenging activity of the 2% SE + LEO solution suggests that this formulation may offer greater protection against oxidative damage and spoilage, potentially resulting in extended shelf life and improved overall quality of the coated fruits and vegetables. Nanoemulsion-based methods have proven effective in encapsulating active ingredients, including antioxidants, due to their small droplet size, stability, and enhanced biological activity [40]. Coatings based on nanoemulsions can act as carriers for oil-soluble vitamins, antimicrobials, flavours, and nutraceuticals, improving the quality attributes of food products [41]. The application of essential oils as natural antimicrobials for food preservation is gaining interest, but their bioactivity can be affected by environmental conditions; encapsulating them in biodegradable polymers can enhance their efficacy and stability [42].

3.2 Analysis on Physicochemical Properties and Shelf Life of Fruits and Vegetables

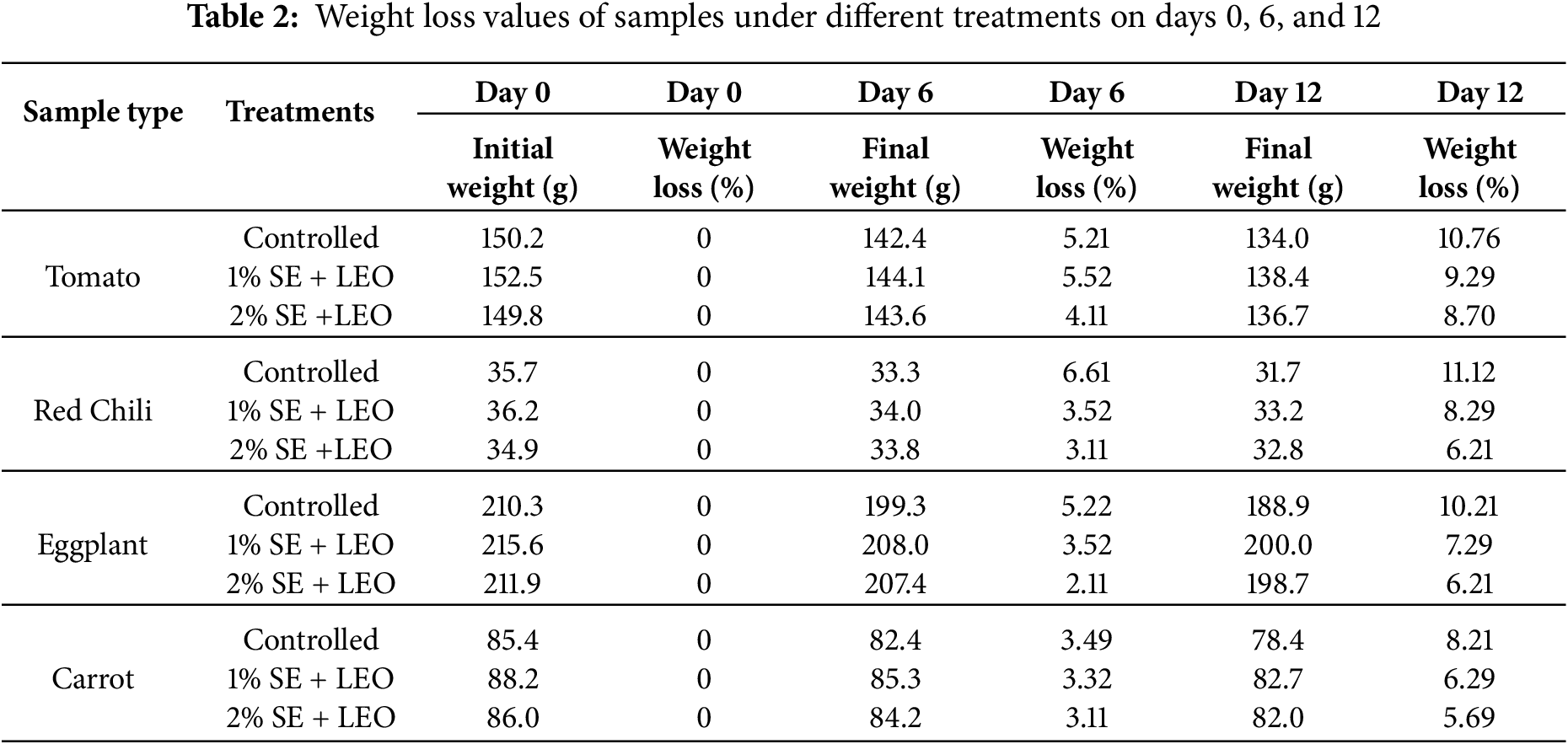

Table 2 shows the weight loss analysis of the samples. The weight loss of coated and uncoated samples is significantly increase with the storage time where all the samples are kept and measured over a 12-days of period to assess the coating effectiveness in preserving their quality. Weight loss analysis is an indicator of quality deterioration, as it is mainly related to shelf life and market acceptability. The results from above diagram, Fig. 1, reveals that there was a trend in weight reduction among the coated and uncoated tomato, red chili, egg plant and carrots which coated using different coating solutions, where coated samples having lower weight loss than control. The data analysis revealed that the samples coated with the 2% seaweed extract + lemon essential oil solution exhibited the lowest percentage of weight loss on the 12th day of storage. This suggests that the 2% SE + LEO coating was the most effective treatment in retaining the weight of the samples, likely due to its ability to control the respiration process and limit moisture loss to the surrounding environment. The use of higher concentrations of plant-based extracts may benefit the coated food samples by reducing weight loss during storage [43].

Figure 1: The percentage of weight loss: (a) tomato, (b) red chili, (c) eggplant, (d) carrot

Weight loss is a critical parameter in assessing the shelf life and quality of fruits and vegetables, as it directly reflects the rate of moisture loss and metabolic activity of the produce during storage. The weight loss in uncoated control samples was significantly higher than in coated samples, which may be attributed to the seaweed-based coatings’ ability to create a protective barrier against moisture loss. The active coating and vacuum packaging act as a physical semi-permeable or impermeable barrier to water vapor and respiratory gases that reduce the fruit metabolic activity [34]. This barrier effect slows down the rate of transpiration and respiration, leading to reduced water loss and subsequently lower weight loss [44]. Seaweed extracts and essential oils have been shown to create a semi-permeable layer on the surface of fruits and vegetables that acts as a barrier to moisture loss and gas exchange. The edible films act as a barrier between the food and the external environment to prevent the direct interaction of food with atmospheric gases and microbes, which reduce the rate of respiration, keeping the food fresh for an extended period [4].

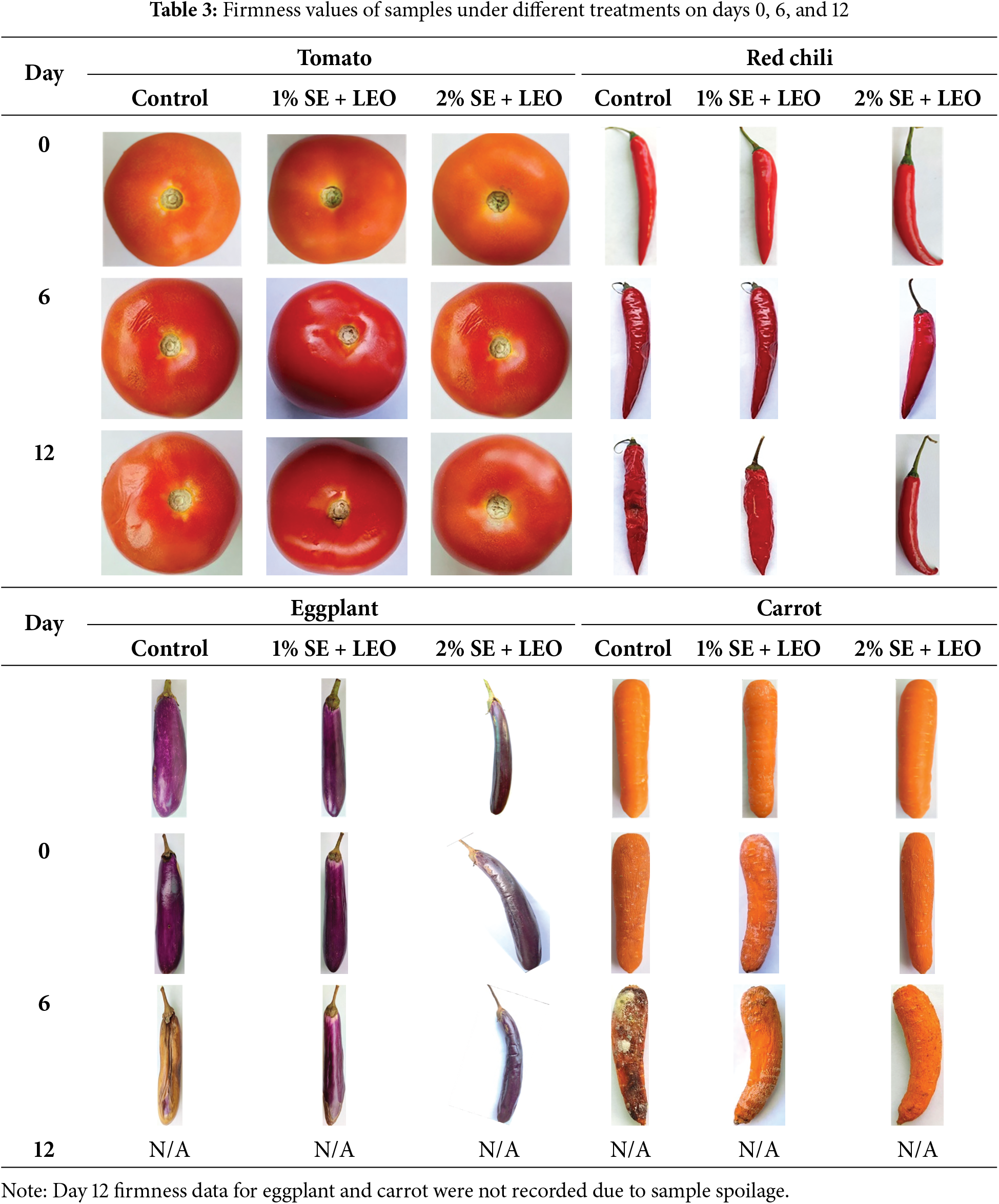

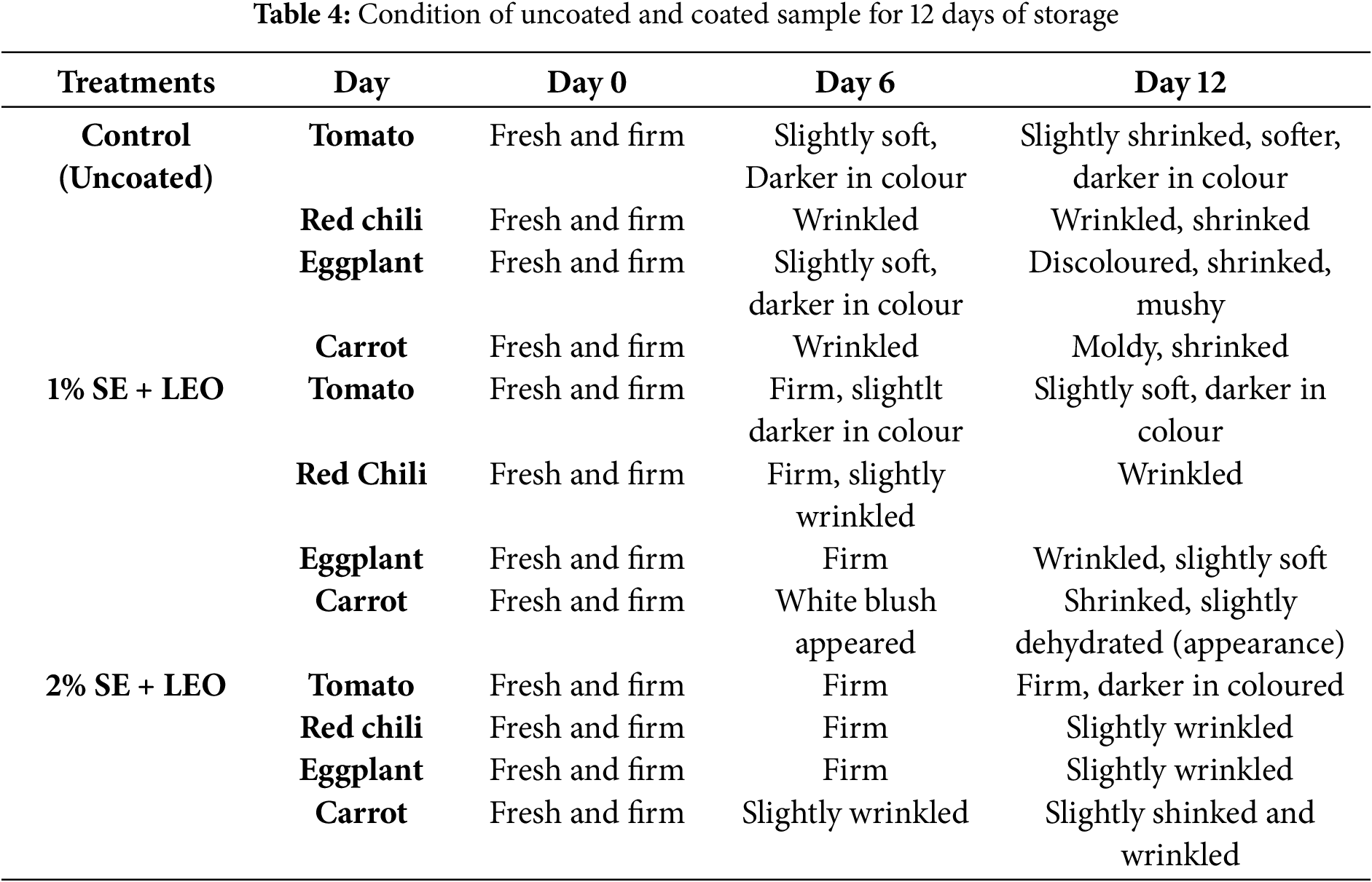

3.2.2 Physical Appearance and Firmness

The results showed that the seaweed coating helped maintain the physical appearance and firmness of the fruits and vegetables during storage as shown in Table 3. The general shelf life under standard storage conditions: tomatoes (5–7 days at room temperature, 7–10 days refrigerated), red chilies (3–5 days at room temperature, 5–7 days refrigerated), eggplants (3–5 days at room temperature, 5–7 days refrigerated), and carrots (1–2 weeks refrigerated). The coated samples retained their color, texture, and overall visual appeal better than the control samples, which exhibited signs of wilting, shriveling, and discoloration [45]. The seaweed coating acts as a protective barrier, reducing the rate of moisture loss and slowing down the degradation processes that lead to changes in physical appearance. The controlled atmosphere created by the coating also helps to maintain the firmness of the produce by preventing cell wall breakdown and tissue softening. The inclusion of lemon essential oil in the seaweed coating can further enhance its ability to preserve the physical appearance and firmness of the fruits and vegetables [46]. The results showed a significant decline in the firmness of the control samples compared to the coated samples over the storage period, where the edible coating maintains the product quality during storage. Firmness of the fruits and vegetables decreases during storage but the rate of firmness loss can be minimized by application of edible coating.

The coated fruit samples had higher firmness values than the uncoated samples at each storage period tested (0, 6, and 12 days), thus the difference in firmness values became more evident as storage time was increased. The firmness value of coated and uncoated samples is significantly decreased with the storage time where all the samples are kept and measured over a 12-days of period to assess the coating effectiveness in preserving their firmness. Firmness analysis is an indicator of quality deterioration. The samples coated with the 2% seaweed extract + lemon essential oil solution exhibited the highest firmness values on the 12th day of storage. These samples were significantly firmer than the uncoated samples, indicating that the 2% SE + LEO coating was the most effective treatment in maintaining the firmness of the samples, likely due to its ability to reduce moisture loss and cell wall breakdown. The firmness and texture of coated commodities have been significantly improved by using the coating formulation [3]. The physical appearance and firmness of fruits and vegetables are crucial indicators of their freshness and consumer appeal, where a natural and safe coating can improve the appearance and safeguard the fruits [47]. However, the study’s dependence on visual observation for firmness assessment was a limitation, as illustrated in Table 4. This subjective method may not accurately reflect minor but significant textural changes. Instrumental measurements should be incorporated into future research to enhance the reliability of the data.

The moisture content of fresh fruits and vegetables is a critical factor in maintaining their turgidity, texture, and overall quality [48]. Fruits and vegetables with high moisture content are more susceptible to microbial spoilage and enzymatic degradation. In this study, the moisture content of the coated and uncoated fruits and vegetables was measured at regular intervals during the storage period to assess the effectiveness of the seaweed coating in retaining moisture. The moisture content of the fruits and vegetables decreased gradually over the storage period. The uncoated samples exhibited a more rapid decline in moisture content compared to the coated samples. This could be attributed to the edible coating’s ability to form a protective barrier, thereby reducing water loss through transpiration [34]. It has been found that edible coatings can significantly reduce the rate of moisture loss in fruits and vegetables, extending their shelf life and preserving their quality [46]. The result shown as a percentage in Fig. 2 shows the moisture content of fruits and vegetables during storage.

Figure 2: The percentage of moisture content on day 0, day 6 and day 12 of each uncoated and coated sample: (a) tomato, (b) red chili, (c) eggplant, (d) carrot

The moisture content of tomato decreased gradually over the storage period, with the uncoated samples exhibiting a more rapid decline compared to the coated samples. On day 0, the moisture content of the uncoated tomato was 93.4%, while the moisture content of tomato coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 93.4% and 93.4%, respectively. On day 6, the moisture content of the uncoated tomato decreased to 88.5%, while the moisture content of tomato coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 90.2% and 91.5%, respectively. On day 12, the moisture content of the uncoated tomato further decreased to 82.3%, while the moisture content of tomato coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 85.6% and 88.9%, respectively.

The moisture content of red chili decreased gradually over the storage period, with the uncoated samples exhibiting a more rapid decline compared to the coated samples. On day 0, the moisture content of the uncoated red chili was 84.2%, while the moisture content of red chili coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 84.2% and 84.2%, respectively. On day 6, the moisture content of the uncoated red chili decreased to 78.4%, while the moisture content of red chili coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 80.1% and 82.5%, respectively. On day 12, the moisture content of the uncoated red chili further decreased to 72.1%, while the moisture content of red chili coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 75.8% and 79.2%, respectively.

The moisture content of eggplant decreased gradually over the storage period, with the uncoated samples exhibiting a more rapid decline compared to the coated samples. On day 0, the moisture content of the uncoated eggplant was 92.7%, while the moisture content of eggplant coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 92.7% and 92.7%, respectively. On day 6, the moisture content of the uncoated eggplant decreased to 86.5%, while the moisture content of eggplant coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 88.2% and 90.5%, respectively. On day 12, the moisture content of the uncoated eggplant further decreased to 79.4%, while the moisture content of eggplant coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 83.7% and 87.1%, respectively.

The moisture content of carrot decreased gradually over the storage period, with the uncoated samples exhibiting a more rapid decline compared to the coated samples [49]. On day 0, the moisture content of the uncoated carrot was 88.3%, while the moisture content of carrot coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 88.3% and 88.3%, respectively. On day 6, the moisture content of the uncoated carrot decreased to 82.6%, while the moisture content of carrot coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 84.3% and 86.6%, respectively. On day 12, the moisture content of the uncoated carrot further decreased to 76.2%, while the moisture content of carrot coated with 1% SE + LEO and 2% SE + LEO was 80.9% and 84.2%, respectively.

Ascorbic acid, commonly known as Vitamin C, is a vital water-soluble vitamin that plays a pivotal role in human health due to its antioxidant properties and involvement in various metabolic processes [50]. However, ascorbic acid is highly susceptible to degradation during postharvest storage due to its sensitivity to factors such as oxidation, light exposure, temperature fluctuations, and enzymatic activity [34]. Fig. 3 illustrates the impact of seaweed extract and lemon essential oil coatings on the ascorbic acid content of fruit and vegetable samples during a 12-day storage period. The results indicate that samples coated with 2% SE + LEO retained significantly higher levels of ascorbic acid compared to the uncoated samples and those coated with 1% SE + LEO.

Figure 3: The percentage of ascorbic acid on day 0, day 6 and day 12 of each uncoated and coated sample: (a) tomato, (b) red chili, (c) eggplant, (d) carrot

The enhanced retention in the 2% SE + LEO group can be ascribed to multiple variables. The coating functions as a physical barrier, reducing exposure to air and light that hastens the decomposition of ascorbic acid. Its semi-permeable characteristics modulate the interior environment, diminishing respiration and enzymatic activity. Secondly, both seaweed extract and lemon essential oil exhibit antioxidant capabilities that may aid in stabilising and safeguarding ascorbic acid from oxidative stress. Seaweed extracts are abundant in phenolics and polysaccharides that neutralise free radicals, whilst lemon essential oil comprises limonene and citral, recognised for their antioxidant properties [51].

The coating may also diminish the action of ascorbic acid oxidase, the enzyme that degrades ascorbic acid The edible coating can increase the shelf life of foods due to its antimicrobial and antioxidant activity [52]. The edible coating enhances preservation by providing both physical and biochemical protective effects, so aiding in the maintenance of the produce’s nutritious content [53]. The findings of maintained levels of ascorbic acid in high light intensity can be maintained during the shelf life [54].

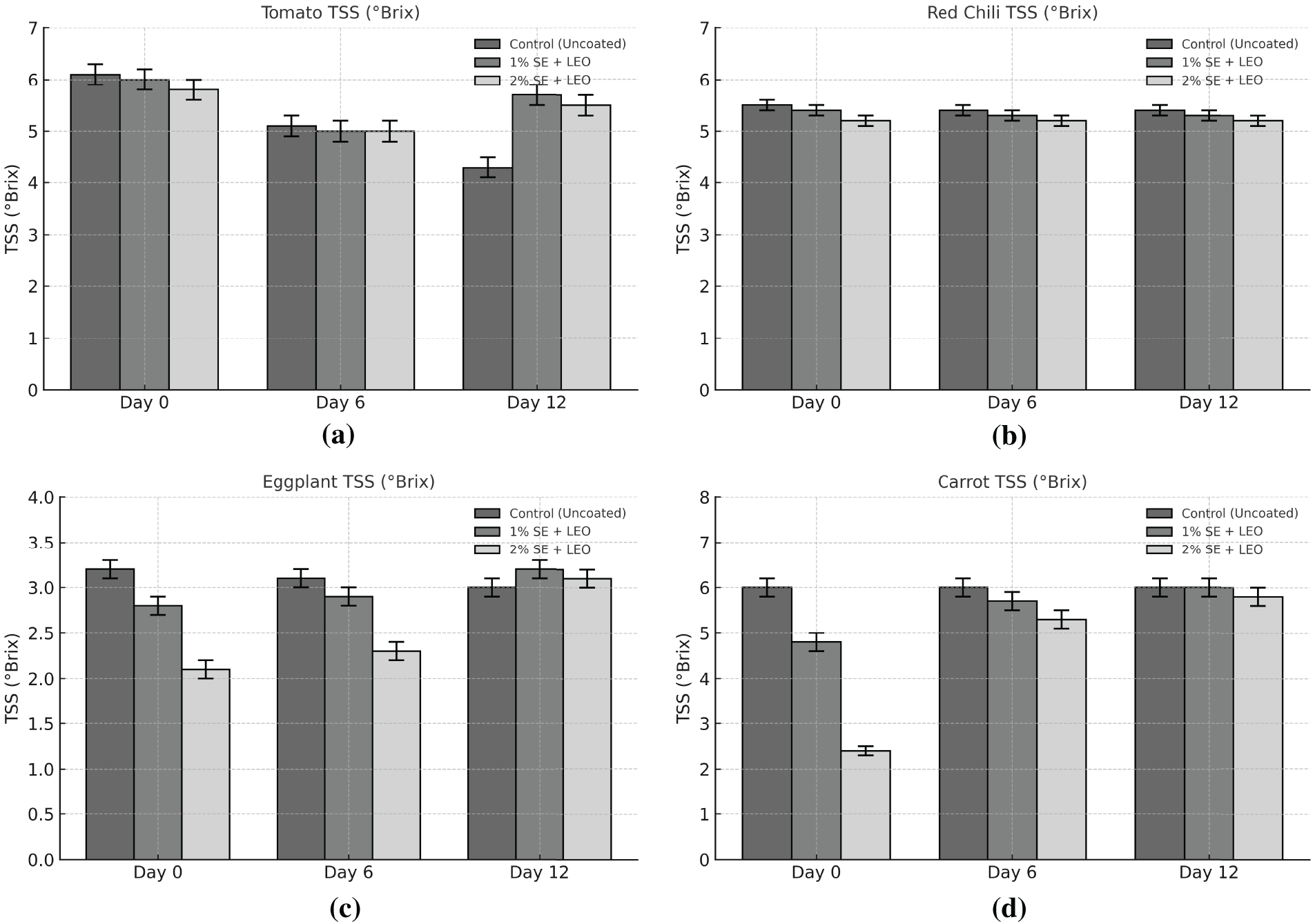

Total soluble solids represent the total concentration of dissolved solids in a solution, primarily consisting of sugars, acids, and minerals. Total soluble solids (TSS) denote the concentration of dissolved substances in product, primarily sugars, acids, and minerals. Fig. 4 presents the trends in TSS content for both coated and uncoated fruit and vegetable samples during a 12-day storage period. The findings indicate that TSS levels rose in all samples throughout time, signifying continuous ripening and carbohydrate degradation. The results indicate that the TSS content generally increased over time for all samples, but the rate of increase was lower in the 2% SE + LEO coated samples compared to the uncoated samples and those coated with 1% SE + LEO [55]. The findings indicate that the coating aids in postponing the ripening process by diminishing the degradation of complex carbohydrates into simple sugars. The combination of seaweed extract and lemon essential oil creates a semi-permeable barrier that restricts gas exchange and reduces metabolic activity, hence assisting in the maintenance of TSS levels [55]. The seaweed extract and lemon essential oil coating acts as a barrier, regulating gas exchange and slowing down the metabolic rate, thereby reducing the breakdown of complex carbohydrates and the subsequent increase in TSS. A minor reduction in TSS was noted throughout the later phases of storage, especially in uncoated samples. This may result from the utilisation of sugars via respiration or microbial activity, causing a reduction in sugar stores. The 2% SE + LEO coating significantly mitigated the rise in TSS during storage, demonstrating its efficacy in maintaining the freshness and postponing the over-ripening of fruits and vegetables [55]. The decrease in TSS levels observed in the later stages of storage, particularly in the uncoated samples, can be attributed to the depletion of sugar reserves through respiration and other metabolic processes. Additionally, microbial activity may contribute to the consumption of sugars, further reducing the TSS content.

Figure 4: Total soluble solid (Brix) on day 0, day 6 and day 12 of each uncoated and coated sample: (a) Tomato, (b) Red chili, (c) Eggplant and (d) Carrot

The findings of this study demonstrate the effectiveness of seaweed extract and lemon essential oil coatings in extending the shelf life and preserving the quality of fruits and vegetables. The 2% SE + LEO formulation particularly reduced weight loss, maintained firmness, preserved ascorbic acid content, and regulated total soluble solids, enhancing the overall postharvest quality. These benefits are attributed to the coating’s ability to act as a barrier against moisture loss, regulate gas exchange, inhibit microbial growth, and reduce enzymatic activity. The coating treatment significantly inhibited respiration rate, weight loss, and softening, while also inhibiting polyphenol oxidase activity, electrolyte leakage, and malondialdehyde accumulation. The seaweed-based coatings are biodegradable, biocompatible, and non-toxic, making them a sustainable alternative to synthetic coatings. Moreover, the use of lemon essential oil enhances the antimicrobial and antioxidant properties of the coating while adding a pleasant aroma, improving the overall sensory appeal. The coatings enriched with active ingredients directly interact with the food surface, inhibiting microbial proliferation. The results have significant implications for the postharvest handling and storage of fruits and vegetables. The seaweed extract and lemon essential oil coatings can reduce postharvest losses, extend shelf life, and maintain nutritional and sensory quality, benefiting producers and consumers. Further research is warranted to optimize the coating formulation, explore its applicability to a wider range of produce, and evaluate its performance under different storage conditions. The combination of seaweed extract with other natural antimicrobials and antioxidants may lead to the development of more effective and sustainable coating solutions for preserving quality and extending shelf life. Edible coatings based on natural sources like seaweed offer a promising approach to reduce food waste and promote sustainable agriculture. However, a limitation of this study is the lack of distinct treatment groups comprising either seaweed extract or solely lemon essential oil. This constrains the capacity to ascertain the distinct effects of each component in isolation. Subsequent research ought to incorporate these distinct treatment groups to more effectively identify and comprehend their individual and collective contributions to preservation.

Acknowledgement: We thank to Faculty of Food Science and Nutrition, Universiti Malaysia Sabah for providing conductive environment for research work.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, methodology, performed analysis, result interpretation: Nuraqilah Syamimi Mat Jauilah; Draft manuscript preparation, writing—review, editing visualization, supervision, project administration: Kobun Rovina, Sarifah Supri; Perform supervision, correspondence, proof reading: Wahidatul Husna Zuldin, Patricia Matanjun, Luh Suriati. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ungureanu C, Tihan G, Zgârian R, Pandelea G. Bio-coatings for preservation of fresh fruits and vegetables. Coatings. 2023;13(8):1420. doi:10.3390/coatings13081420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Díaz-Montes E, Castro-Muñoz R. Edible films and coatings as food-quality preservers: an overview. Foods. 2021;10(2):249. doi:10.3390/foods10020249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Pham TT, Nguyen LLP, Dam MS, Baranyai L. Application of edible coating in extension of fruit shelf life. AgriEngineering. 2023;5(1):520–36. doi:10.3390/agriengineering5010034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Singh DP, Packirisamy G. Biopolymer based edible coating for enhancing the shelf life of horticulture products. Food Chem Mol Sci. 2022;4(5):100085. doi:10.1016/j.fochms.2022.100085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Felicia WXL, Rovina K, Nur’Aqilah MN, Vonnie JM, Erna KH, Misson M, et al. Recent advancements of polysaccharides to enhance quality and delay ripening of fresh produce: a review. Polymers. 2022;14(7):1341. doi:10.3390/polym14071341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Orozco-Parra J, Mejía CM, Villa CC. Development of a bioactive synbiotic edible film based on cassava starch, inulin, and Lactobacillus casei. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;104(1):105754. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Supri S, Felicia WXL, Affandy M, Aqilah M, Padam BS, Prihanto AA, et al. Macroalgae-based bio-based packaging: characteristics, green extraction methods, and applications as sustainable solutions. Int J Adv Sci Eng Inf Technol. 2025;15(1):249–66. doi:10.18517/ijaseit.15.1.20211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Mendes CG, Martins JT, Lüdtke FL, Geraldo A, Pereira A, Vicente AA, et al. Chitosan coating functionalized with flaxseed oil and green tea extract as a bio-based solution for beef preservation. Foods. 2023;12(7):1447. doi:10.3390/foods12071447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Perez-Vazquez A, Barciela P, Carpena M, Prieto MA. Edible coatings as a natural packaging system to improve fruit and vegetable shelf life and quality. Foods. 2023;12(19):3570. doi:10.3390/foods12193570. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Anis A, Pal K, Al-Zahrani SM. Essential oil-containing polysaccharide-based edible films and coatings for food security applications. Polymers. 2021;13(4):575. doi:10.3390/polym13040575. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Gheorghita R, Gutt G, Amariei S. The use of edible films based on sodium alginate in meat product packaging: an eco-friendly alternative to conventional plastic materials. Coatings. 2020;10(2):166. doi:10.3390/coatings10020166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Poeloengasih CD, Srianisah M, Jatmiko TH, Prasetyo DJ. Postharvest handling of the edible green seaweed Ulva lactuca: mineral content, microstructure, and appearance associated with rinsing water and drying methods. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2019 Apr. Vol. 253. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/253/1/012006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Bensy AD, Christobel GJ. Green synthesis of iron nanoparticles using aqueous extract of Turbinaria conoides (J. Agardh) and their anticancer properties. Current Bot. 2021;12:75–9. doi:10.25081/cb.2021.v12.6615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Derbew Gedif H, Tkaczewska J, Jamróz E, Zając M, Kasprzak M, Pająk P, et al. Developing technology for the production of innovative coatings with antioxidant properties for packaging fish products. Foods. 2022;12(1):26. doi:10.3390/foods12010026. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Ramadhan W, Uju U, Hardiningtyas SD, Pari RF, Nurhayati N, Sevica D. Ekstraksi polisakarida Ulvan dari rumput laut Ulva lactuca berbantu gelombang ultrasonik pada suhu rendah. J Pengolahan Has Perikanan Indones. 2022;25(1):132–42. doi:10.17844/jphpi.v25i1.40407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yingngam B, Zhao H, Baolin B, Pongprom N, Brantner A. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted extraction and purification of rhein from Cassia fistula pod pulp. Molecules. 2019;24(10):2013. doi:10.3390/molecules24102013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Bosma R, Van Spronsen WA, Tramper J, Wijffels RH. Ultrasound, a new separation technique to harvest microalgae. J Appl Phycol. 2003;15:143–53. doi:10.1023/a:1023807011027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Yatim KM, Krishnan G, Bakhtiar H, Daud S, Harun SW. The pH sensor based optical fiber coated with PAH/PAA. In: Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2019. Vol. 1371. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1371/1/012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Fuloria S, Wei LT, Karupiah S, Subramaniyan V, Gellknight C, Wu YS, et al. Development and validation of UV-visible method to determine gallic acid in hydroalcoholic extract of Erythrina fusca leaves. Int J Res Pharm Sci. 2020;11(4):6319–26. doi:10.26452/ijrps.v11i4.3386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Vo TP, Le NPT, Mai TP, Nguyen DQ. Optimization of the ultrasonic-assisted extraction process to obtain total phenolic and flavonoid compounds from watermelon (Citrullus lanatus) rind. Curr Res Food Sci. 2022;5(3):2013–21. doi:10.1016/j.crfs.2022.09.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Belkacemi L, Belalia M, Djendara AC, Bouhadda Y. Antioxidant and antibacterial activities and identification of bioactive compounds of various extracts of Caulerpa racemosa from Algerian coast. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2020;10(2):87–94. doi:10.4103/2221-1691.275423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Pereira KL, de Goes Sampaio C, Martins VEP, Rebouças LM, de Souza JSN, Santos EM. Antioxidant activity and determination of total phenolics of natural products from the Brazilian flora. J Appl Pharm Sci Res. 2022;5(3):47–50. doi:10.31069/japsr.v5i3.06. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Sousa G, Trifunovska M, Antunes M, Miranda I, Moldão M, Alves V, et al. Optimization of ultrasound-assisted extraction of bioactive compounds from Pelvetia canaliculata to sunflower oil. Foods. 2021;10(8):1732. doi:10.3390/foods10081732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Somwongin S, Sirilun S, Chantawannakul P, Anuchapreeda S, Yawootti A, Chaiyana W. Ultrasound-assisted green extraction methods: an approach for cosmeceutical compounds isolation from Macadamia integrifolia pericarp. Ultrason Sonochem. 2023;92(3):106266. doi:10.1016/j.ultsonch.2022.106266. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Shargi AH, Aboied M, Magbool FF. Improved high-performance liquid chromatography/mass spectroscopy (HPLC/MS) method for detection of anthraquinones and antioxidant potential determination in Aloe sinkatana. Univers J Pharm Res. 2020;5(2):6–9. doi:10.22270/ujpr.v5i2.381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Galera Manzano LM, Ruz Cruz MÁ., Moo Tun NM, Valadez González A, Mina Hernandez JH. Effect of cellulose and cellulose nanocrystal contents on the biodegradation, under composting conditions, of hierarchical PLA biocomposites. Polymers. 2021;13(11):1855. doi:10.3390/polym13111855. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Rodrigues DP, Mitterer-Daltoé ML, Lima VAD, Barreto-Rodrigues M, Pereira EA. Simultaneous determination of organic acids and sugars in fruit juices by High performance liquid chromatography: characterization and differentiation of commercial juices by principal component analysis. Ciência Rural. 2021;51(3):e20200629. doi:10.1590/0103-8478cr20200629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Putri FR, Adjeng ANT, Yuniar NANI, Handoyo MUHAMAD, Sahumena MA. Formulation and physical characterization of curcumin nanoparticle transdermal patch. Int J Appl Pharm. 2019;11(6):217–21. doi:10.22159/ijap.2019v11i6.34780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Nielsen SS. Vitamin C determination by indophenol method. In: Nielsen’s food analysis laboratory manual. Cham, Switzerland: Springer International Publishing; 2024. p. 153–6. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44127-6_15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Vargas HC, Aggabao CM. Organoleptic evaluation of mixed powdered cotton fruit (Sandoricum Koetjape) and rattan fruit (Calamus Manillensis) as souring agent. Int J Multidiscipl Res Anal. 2023;6(5):2198–2205. doi:10.5281/zenodo.7973934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Butola BS. A synergistic combination of shrimp shell derived chitosan polysaccharide with Citrus sinensis peel extract for the development of colourful and bioactive cellulosic textile. Int J Biol Macromol. 2020;158(4):94–103. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2020.04.209. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Rodrigues FAM, dos Santos SBF, de Almeida Lopes MM, Guimarães DJS, de Oliveira Silva E, de Souza Filho MDSM, et al. Antioxidant films and coatings based on starch and phenolics from Spondias purpurea L. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;182:354–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.04.012. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Peñalver R, Lorenzo JM, Ros G, Amarowicz R, Pateiro M, Nieto G. Seaweeds as a functional ingredient for a healthy diet. Mar Drugs. 2020;18(6):301. doi:10.3390/md18060301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Zandi M, Ganjloo A, Bimakr M, Moradi N, Nikoomanesh N. Effect of active coating containing radish leaf extract with or without vacuum packaging on the postharvest changes of sweet lemon during cold storage. J Food Process Preserv. 2021;45(3):e15252. doi:10.1111/jfpp.15252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Widsten P, Salo S, Hakkarainen T, Nguyen TL, Borrega M, Fearon O. Antimicrobial and flame-retardant coatings prepared from nano-and microparticles of unmodified and nitrogen-modified polyphenols. Polymers. 2023;15(4):992. doi:10.3390/polym15040992. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Galus S, Mikus M, Ciurzyńska A, Domian E, Kowalska J, Marzec A, et al. The effect of whey protein-based edible coatings incorporated with lemon and lemongrass essential oils on the quality attributes of fresh-cut pears during storage. Coatings. 2021;11(7):745. doi:10.3390/coatings11070745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Karnwal A, Kumar G, Singh R, Selvaraj M, Malik T, Al Tawaha ARM. Natural biopolymers in edible coatings: applications in food preservation. Food Chemistry X. 2025;25(5):102171. doi:10.1016/j.fochx.2025.102171. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Jasti T, Chintala RK, Kolluru VC. Biological functions of volatile compounds extracted from the rice bran—a review. Biomed Pharmacol J. 2020;13(1):213–31. doi:10.13005/bpj/1879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Piechowiak T, Balawejder M. The study on the use of flavonoid-phosphatidylcholine coating in extending the oxidative stability of flaxseed oil during storage. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2021;28(2):100643. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2021.100643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Maurya A, Singh VK, Das S, Prasad J, Kedia A, Upadhyay N, et al. Essential oil nanoemulsion as eco-friendly and safe preservative: bioefficacy against microbial food deterioration and toxin secretion, mode of action, and future opportunities. Front Microbiol. 2021;12:751062. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2021.751062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. De Oliveira Filho JG, Miranda M, Ferreira MD, Plotto A. Nanoemulsions as edible coatings: a potential strategy for fresh fruits and vegetables preservation. Foods. 2021;10(10):2438. doi:10.3390/foods10102438. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Tripathi AD, Sharma R, Agarwal A, Haleem DR. Nanoemulsions based edible coatings with potential food applications. Int J Biobased Plast. 2021;3(1):112–25. doi:10.1080/24759651.2021.1875615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Moradinezhad F, Ranjbar A. Advances in postharvest diseases management of fruits and vegetables: a review. Horticulturae. 2023;9(10):1099. doi:10.3390/horticulturae9101099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Ghosh M, Singh AK. Potential of engineered nanostructured biopolymer based coatings for perishable fruits with Coronavirus safety perspectives. Prog Org Coat. 2022;163(9):106632. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2021.106632. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Barbosa CH, Andrade MA, Vilarinho F, Fernando AL, Silva AS. Active edible packaging. Encyclopedia. 2021;1(2):360–70. doi:10.3390/encyclopedia1020030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Ramani S, Murugan A. Effect of seaweed coating on quality characteristics and shelf life of tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum mill). Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2020;9(2):176–83. doi:10.1016/j.fshw.2020.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Hassan HS, EL-Hefny M, Ghoneim IM, El-Lahot MSA, Akrami M, Al-Huqail AA, et al. Assessing the use of aloe vera gel alone and in combination with lemongrass essential oil as a coating material for strawberry fruits: HPLC and EDX analyses. Coatings. 2022;12(4):489. doi:10.3390/coatings12040489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. A’yun AQ, Bintoro N. The effect of starch proportion in coating materials and storage temperatures on the physical qualities of curly green chili (Capsicum annuum L). In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2021. Vol. 828. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/828/1/012040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Haryanto B, Sinuhaji TRF, Tarigan EA, Tarigan MB, Sitepu NB. Simulation of natural drying kinetics of carrot (Daucus carota L) on thickness variation. In: IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. Bristol, UK: IOP Publishing; 2021. Vol. 782. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/782/3/032086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Zhang J, Liu S, Zhu X, Chang Y, Wang C, Ma N, et al. A comprehensive evaluation of tomato fruit quality and identification of volatile compounds. Plants. 2023;12(16):2947. doi:10.3390/plants12162947. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Nicolau-Lapeña I, Aguiló-Aguayo I, Kramer B, Abadias M, Viñas I, Muranyi P. Combination of ferulic acid with Aloe vera gel or alginate coatings for shelf-life prolongation of fresh-cut apples. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2021;27(3):100620. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2020.100620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Panahi Z, Khoshbakht R, Javadi B, Firoozi E, Shahbazi N. The effect of sodium alginate coating containing citrus (Citrus aurantium) and Lemon (Citrus lemon) extracts on quality properties of chicken meat. J Food Qual. 2022;2022(1):6036113. doi:10.1155/2022/6036113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Swamy MVM, Kumar NV, Kamatyanatti M. Use of several edible natural coatings on kinnow (Citrus reticulata Blanco) fruit. Int J Chem Stud. 2020;8(6):1969–72. doi:10.22271/chemi.2020.v8.i6ab.11055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Min Q, Marcelis LF, Nicole CC, Woltering EJ. High light intensity applied shortly before harvest improves lettuce nutritional quality and extends the shelf life. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12:615355. doi:10.3389/fpls.2021.615355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Mohammed OO, Azzazy MB, Badawe SEA. Effect of some edible coating materials on quality and postharvest rots of cherry tomato fruits during cold storage. Zagazig J Agric Res. 2021;48(1):37–54. doi:10.21608/zjar.2021.165655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools