Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

A Minireview on Comprehensive Application of Hydrogels Used as Electrolytes in Flexible Zinc-Air Batteries

School of Mechanical Engineering, University of South China, Hengyang, 421001, China

* Corresponding Author: Xiaomin Kang. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 587-619. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.067647

Received 08 May 2025; Accepted 04 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

With the rapid development of flexible and wearable electronic devices, the demand for flexible power sources with high energy density and long service life is imminent. Zinc-air batteries have long been regarded as an important development direction in the future due to their high safety, environmental efficiency, abundant reserves and low cost. However, problems such as zinc dendrite growth, corrosion, by-product generation, hydrogen evolution and leakage, and evaporation of electrolyte affect the commercialization of zinc-air batteries. In addition, currently widely used aqueous electrolytes lead to larger batteries, which is not conducive to the development of emerging smart devices. The characteristics of the hydrogel electrolyte can solve the above problems. In order to promote the wider application of gel electrolyte-based zinc batteries, this paper reviews the recently reported polymer electrolytes in flexible zinc-air batteries (FZABs), reviews the working mechanism of ZABs, and enumerates the general assembly structure of FZABs. The types and characteristics of hydrogel electrolytes with excellent performance at present, as well as the corresponding performance of FZABs, are summarized. In addition, the challenges in the application of gel electrolytes and gel-based FZABs are discussed, and the future research and development prospects of next-generation high-performance solid-state ZABs are prospected.Keywords

Portable, bendable and wearable flexible consumer electronic products have brought great convenience to people’s daily life, and their significance to modern society is also increasing [1–5]. With the continuous development of wearable devices (such as wireless sensors, implantable medical chips, and smart clothing), miniaturized and flexible energy storage devices have become the key to realizing their autonomous operation [6–9]. Therefore, it is necessary to study a new flexible rechargeable battery [10] with high safety, small size, good mechanical flexibility, stable electrochemical performance, adaptability to deformation, and long life to provide energy for wearable devices. Currently, lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) dominate mainstream markets, from smartwatches to electric vehicles, owing to their inherently high voltage and high energy density. However, in the field of flexible energy storage, the currently popular lithium-ion batteries face challenges such as poor safety, limited lithium reserves, and high cost [11–15]. Moreover, the organic electrolytes commonly used in LIBs are toxic [16–18] and flammable [19–21], which is risky when used in wearable/implantable devices that are in close contact with the human body, seriously hindering the development of wearable devices. Therefore, there is an urgent need for an energy storage solution that can replace lithium-ion batteries. In recent years, zinc-air batteries (ZABs) have attracted much attention due to their inherent safety, high capacity, eco-efficiency, and satisfactory energy density [22–27] and have been identified as one of the promising alternatives to LIBs. Because they provide high theoretical specific energy (1086 Wh kg−1) [12,28] and excellent rate performance. The ZABs use oxygen as the positive electrode material, zinc metal as the negative electrode material, and alkaline solution as the electrolyte. The mechanism is based on the electrochemical reaction: (2Zn + O2 ⇌ 2ZnO). Therefore, such systems have several advantages, such as environmental friendliness, low cost, and ease of fabrication [12,29–34]. In the last decades, the development of ZABs has shown their competitive advantages. First of all, high theoretical capacity. Metallic Zn can be directly used as a negative electrode due to its intrinsically stable chemical properties, with a theoretical capacity of up to 5854 mAh·cm−3 (alternatively 820 mAh·g−1) [35,36]. Secondly, high energy density. The theoretical energy density of ZABs is as high as 1086 Wh·kg−1 (containing oxygen), which is about 5 times that of current lithium-ion batteries. At the same time, the energy density of ZABs also stands out among various types of metal ion batteries, which is mainly attributed to their low electrochemical potential (−0.763 V vs. SHE) and two-electron transfer during zinc ion redox reaction [37,38]. Thirdly, the crustal abundance of Zn is high. The abundance of Zn in the Earth’s crust is 70 ppm, which is 3 times than that of Li (20 ppm) [39]. Besides, low cost and large-scale production. It is estimated by researchers that the manufacturing cost of commercial ZABs does not exceed 10 $kWh−1 [12,37,38]. In addition, low toxicity, non-flammability, biocompatibility [40]. The above-mentioned advantages of zinc-air batteries are well suited to these requirements. However, this does not mean that (FZABs) will necessarily become the energy source of the next generation of flexible and wearable electronic devices. In fact, there are still many problems to be solved urgently in the process of industrialization. At present, most of the electrolytes used in zinc-air batteries are alkaline solutions, which are widely used in zinc-air pools due to their advantages such as high ionic conductivity and low viscosity [23,41–49]. However, the leakage problem of alkaline electrolytes (AEs) in flexible batteries is still in its initial stage [45]. Most FZABs (FZABs) use a certain amount of water in the solid electrolyte, which makes the high concentration of alkaline electrolyte easily seep out of the semi-open device during bending and compression, which is absolutely unacceptable for flexible and wearable electronics. At present, the mainstream electrolyte solution for FZABs is alkaline hydrogel electrolyte. Hydrogel electrolyte achieves a good balance between mechanical properties, safety, electrochemical performance and the environment, making it suitable for application in flexible battery systems (Fig. 1 lists the development process of gel electrolyte). However, compared with aqueous electrolytes, the slow ion migration, water retention capacity, and CO2 resistance of hydrogel electrolytes have become the constraints on the performance of hydrogel electrolytes [50–52]. Therefore, the development of high-quality polymer electrolytes suitable for zinc-air batteries has been the goal pursued by many researchers and scholars. At present, many scholars are dedicated to researching new gel electrolytes and applying them to energy storage devices in the hope of improving their electrochemical performance and Physical and chemical properties. Kang et al. [53] reported a type of polybutyl acrylate (PBA) emulsion microsphere prepared by emulsion polymerization, and introduced it as a hydrophobic binding center into PVA/PAAm dual network hydrogel, which has excellent elasticity and fatigue resistance. Wang et al. [54] systematically studied a low water content hydrogel electrolyte (HPG) designed by molecular engineering. This electrolyte suppresses side reactions by reducing the free water content, while optimizing the zinc ion transport pathway using flexible polymer chains and hydrophilic groups, achieving efficient reversible deposition/stripping of zinc negative electrodes at high temperatures (90°C) (99% Coulombic efficiency). Peng et al. [55] proposes a new method for preparing low-cost ethylene oxide based polymer electrolytes by fixing liquid PEGDME electrolyte with charged rigid rod polymer PBDT. The gel electrolyte has good mechanical and thermal stability. In addition, an increasing number of scholars are studying zinc air batteries. Zhang et al. [56]. investigated the deep integration of nanomaterials with zinc air batteries and provided prospects for future development. This paper reviews the recently reported polymer electrolytes in FZABs, reviews the working mechanism of ZABs, and enumerates the general assembly structure of FZABs. Therefore, the types and characteristics of current hydrogel electrolytes with excellent performance and the corresponding performance of FZABs are summarized. Furthermore, the challenges in the application of gel electrolytes and gel-based FZABs are discussed, and the future research and development prospects of next-generation high-performance solid-state ZABs are prospected (Fig. 2 lists the application scenarios of ZABs).

Figure 1: Development of gel electrolytes. Reproduced with permission [57–60]. Copyright 2020, Wiley; 2023, Elsevier; 2022, Wiley

Figure 2: Multiple applications of zinc based batteries

2 The Working Principle of Zinc Air Batteries and the Comparation of Solid-State Electrolyte Comparison and Characterization Techniques

2.1 Working Principle of Zinc Air Battery

Both FZABs and conventional aqueous zinc-air batteries consist of zinc electrodes, air electrodes, and electrolytes (hydrogel electrolytes and aqueous electrolytes) [61–64]. In the alkaline battery system, the battery charge and discharge mechanism is similar, all of which are realized by the redox reaction between the positive and negative electrodes in the alkaline electrolyte [65,66]. Fig. 3 shows the working mechanism of zinc-air battery.

Figure 3: Working mechanism of zinc-air battery. Reproduced with permission [67]. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry

The overall mechanism of zinc-air batteries involves the redox reaction between external oxygen and zinc metal, resulting in the generation of electrical energy [68,69]. In alkaline electrolytes, During discharge (Fig. 3a), zinc ions combine with hydroxide ions to form zincate complexes (Zn(OH)42−, serving as the primary charge carriers). Once the zincate concentration surpasses its saturation threshold, insoluble zinc oxide—derived from the zincate—precipitates out. Theoretically, the charging process reverses this transformation: zinc oxide converts back into zincate ions, which subsequently deposit onto the anode as metallic zinc (Fig. 3b). The corresponding electrochemical reactions are described below:

Discharge process:

Charging process:

As an energy storage system with high theoretical energy density and environmentally friendly characteristics, the core performance of zinc air batteries lies in the efficient and stable reaction between oxygen reduction/oxygen evolution (ORR/OER) dual functional cathodes and zinc metal anodes. At the cathode, oxygen molecules in the environment undergo a complex multi electron transfer process at the three-phase interface: during discharge, oxygen obtains electrons on the catalyst surface and combines with water molecules in the electrolyte, being reduced to hydroxide ions; When charging, the reverse process occurs, and hydroxide ions lose electrons under the action of the catalyst, releasing oxygen. This reversible process highly relies on the design of efficient bifunctional catalysts to reduce the reaction energy barrier. Correspondingly, the anode undergoes dissolution oxidation of zinc during discharge, generating soluble zincate ions; During charging, zinc ions are reduced and deposited on the electrode surface to form metallic zinc. In an ideal scenario, this dissolution/deposition process should be highly reversible. However, in a strongly alkaline electrolyte environment, the surface of the zinc anode often exhibits complex and unstable interface states due to various side reactions, severely limiting the cycling life and efficiency of the battery.

The complexity of the zinc anode surface mainly stems from three interrelated side reactions: zinc dendrite growth, hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), and chemical corrosion. The formation of zinc dendrites is essentially a manifestation of kinetic runaway during the electrodeposition process. Under conditions of high local current density, uneven distribution of zinc ion concentration, or differences in substrate surface energy, zinc tends to preferentially nucleate at certain active sites and rapidly grow one-dimensional along preferred directions, forming dendritic or mossy structures. Dendrites not only consume active substances and increase internal resistance, but their sharp shape makes it easier to penetrate the separator and cause internal short circuit failure in the battery. The occurrence of hydrogen evolution reaction is due to the relatively low hydrogen evolution overpotential of zinc electrode in aqueous electrolyte solution. In the electrochemical reduction process, when the electrode potential is negative to the hydrogen evolution potential, water molecules or hydrogen ions will competitively obtain electrons on the zinc surface to reduce and produce hydrogen gas. This reaction not only consumes effective charge and reduces Coulomb efficiency, but also generates gas that increases the internal pressure of the battery and damages the integrity of the electrode structure. The chemical corrosion of zinc in alkaline environments is a thermodynamically spontaneous dissolution process. Even in an open circuit state, zinc reacts with water and oxidants in the electrolyte to form zinc hydroxide or zincate and release hydrogen gas. This process continuously consumes active zinc, leading to irreversible degradation of battery capacity and the formation of a passivation layer on the electrode surface, which may hinder subsequent electrochemical reaction kinetics.

It is crucial to thoroughly analyze the influencing factors of these side reactions. The growth rate and morphology of zinc dendrites strongly depend on the current density distribution on the electrode surface, the mass transfer rate of zinc ions at the electrode/electrolyte interface, the physical and chemical properties of the substrate material (such as crystal orientation, defect density), and the composition of the electrolyte (such as additives, zinc ion concentration). High current density, low zinc ion concentration, uneven electric field distribution, and rough surfaces with a large number of nucleation sites all exacerbate dendrite problems. The rate of hydrogen evolution reaction is regulated by the intrinsic hydrogen evolution catalytic activity of the zinc electrode, the true surface area (roughness) of the electrode, the local pH value, and the electrode potential. The presence of zinc surface impurities (such as iron, copper, etc.), highly active crystal planes, or alloying elements can significantly reduce the hydrogen evolution overpotential and accelerate hydrogen evolution. In addition, the more negative the cathodic polarization potential during the charging process, the greater the thermodynamic driving force that drives the hydrogen evolution reaction. For chemical corrosion, its rate is mainly affected by the corrosion potential of the zinc electrode, solution pH value, temperature, dissolved oxygen concentration, and corrosion inhibitors or promoters in the electrolyte. High temperature, high pH value, and the presence of dissolved oxygen all accelerate the corrosion and dissolution of zinc. Of particular note is that the growth of dendrites significantly increases the specific surface area of the electrode, providing more active sites for hydrogen evolution and corrosion; The formation of corrosion product layer or passivation film can change the local current distribution, which may induce new dendritic growth points. The three often form a complex vicious cycle, jointly leading to the destruction of anode structure and performance degradation.

Optimizing the stability of zinc anodes requires starting from regulating the interface reaction environment and electrode structure. The key to suppressing dendrites lies in achieving uniform nucleation and deposition of zinc. This can be achieved by designing a three-dimensional conductive framework to homogenize the current density, introducing electrolyte additives (such as surfactants and metal ions) to regulate the solvation structure and interface energy of zinc ions, or constructing an artificial solid-state electrolyte interface (SEI) film to guide planar growth. The strategy of slowly resolving hydrogen focuses on increasing the overpotential of the hydrogen evolution reaction, including electrode surface alloying (introducing high hydrogen evolution overpotential metals such as Pb and In), surface coatings (such as hydrophobic layers and inorganic protective layers), and optimizing electrolytes (such as using high concentration electrolytes to reduce water activity). To control corrosion, it is necessary to establish a stable electrode/electrolyte interface protective layer, such as in-situ formation of dense passivation films (such as zinc phosphate, organic-inorganic hybrid layers), addition of efficient corrosion inhibitors (such as organic amines, inorganic polyphosphates) to adsorb on active sites and block corrosion reactions, while strictly reducing oxidative impurities in the electrolyte (such as dissolved oxygen, metal ion impurities). The synchronous optimization of cathode performance, especially the development of efficient and stable bifunctional oxygen catalysts to reduce charge discharge overpotentials, can indirectly alleviate the pressure of side reactions occurring at the anode under high overpotentials.

2.2 Comparison of Solid Electrolytes in Zinc Air Batteries

In zinc air batteries (ZABs), the solid-state electrolyte system involves multiple material categories, including inorganic ceramics, polymers, and composite materials, each with its unique performance advantages and challenges. Inorganic ceramic electrolytes, such as zirconia (ZrO2)-based and sulfide based materials, have attracted attention due to their high ionic conductivity and good thermal stability. These materials can maintain stability over a wide temperature range and have excellent catalytic activity for the electrochemical reactions of zinc negative electrodes and air positive electrodes. However, the brittleness and processing difficulty of ceramic electrolytes limit their application in flexible battery design. In contrast, polymer electrolytes, such as polyethylene oxide (PEO) based materials, provide better flexibility and processability, and can be made into thin films through methods such as solution casting or spin coating. Polymer electrolytes can optimize their ion conductivity by adjusting the polymer chain structure and adding ion conductive fillers, but usually require high temperatures to achieve higher conductivity. Composite electrolytes combine the advantages of ceramics and polymers. By dispersing ceramic particles in a polymer matrix, the mechanical flexibility of the electrolyte is maintained while the ionic conductivity is improved. This material design also allows for optimization of electrolyte performance by adjusting the proportion and structure of each component in the composite material, such as increasing the content of ceramic fillers to improve conductivity or optimizing the polymer network structure to improve mechanical strength.

2.3 Typical Application of Characterization Technology in Hydrogel Electrolyte Research

In the research of hydrogel electrolytes, advanced characterization technology [70] is the key to reveal the complex relationship between their structure and performance. For example, scanning electron microscope (SEM) and transmission electron microscope (TEM) are used to observe the microstructure and pore distribution of the hydrogel electrolyte, so as to understand how these physical properties affect the ion transport and the mechanical strength of the electrolyte. X-ray diffraction (XRD), Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR) and other technologies are used to analyze the chemical composition and crystal structure of hydrogels, including the structural arrangement of polymer chains and the existence of functional groups, which are essential to understand the thermal stability and electrochemical properties of electrolytes. In addition, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) can be used to study the thermal properties of hydrogel electrolytes, such as thermal decomposition temperature and glass transition temperature, which are crucial for evaluating the performance of electrolytes at different temperatures. Electrochemical techniques such as electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and cyclic voltammetry (CV) are used to explore the ionic conductivity and electrochemical reaction kinetics of hydrogel electrolytes, thus revealing their potential performance in practical battery applications. Through the comprehensive application of these characterization technologies, researchers can systematically understand the composition, structure, performance and application potential of hydrogel electrolytes in energy storage and conversion. For example, Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) can be used for qualitative and quantitative analysis of polymer gel electrolyte [71]. The core working principle of a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer is to irradiate the sample with infrared light at a specific frequency. When a certain group in the sample molecule vibrates at the same frequency as the incident infrared light, resonance occurs and the corresponding frequency of infrared radiation is absorbed. This technology provides a molecular level approach to understanding material properties and behavior by analyzing the absorption characteristics of samples towards infrared radiation.

3 Designed Structures of FZABs

Since FZABs need to be used in wearable devices (such as wireless sensors, implantable medical chips, smart clothing, etc.), they need to be small in size, have good mechanical flexibility, can adapt to deformation, and maintain stable electrochemical performance under the action of various external forces. At the same time, FZABs have great similarities in structure with traditional aqueous zinc-air batteries-both are mainly composed of metal electrodes, aqueous/hydrogel electrolytes and air electrodes [72]. Currently, the most common assembly structures of solid-state zinc-air batteries include cable-type and sandwich-type configurations, as shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: The most common assembly structures of solid-state zinc-air batteries. (a) Cable type; (b) Sandwich type configuration. Reproduced with permission [67]. Copyright 2023, Royal Society of Chemistry

As one of the most typical flexible zinc-air battery structures, the schematic diagram of the cable battery structure is shown in Fig. 4a. The metal electrode of the cable zinc-air battery is located at the center of the battery system. The zinc wire is tightly wrapped by a hydrogel electrolyte membrane. The catalyst is then loaded onto an air electrode, wound around the electrolyte, and assembled into a linear battery structure.

The original configuration of cable-type flexible zinc-air battery was proposed by Park et al. [73] in 2014. Its manufacturing process is shown in Fig. 5a,b. Zinc is rotated around a steel rod to make a zinc spring, and then the steel rod is withdrawn. The hydrogel precursor is coated on the zinc, the template is removed after solidification (Fig. 5), the air electrode is coated, and finally encapsulated with a breathable heat shrinkable tube.

Figure 5: Schematic diagram of manufacturing cable flexible zinc-air battery. Reproduced with permission [73]. Copyright 2014, Europe PMC

Based on the cable-type structure, the present work mainly focuses on the modification of air cathode. For example, Li et al. [74] used NiCo2O4@NiCoFe-OH as air cathodes to prepare a cable zinc-air battery with a specific capacity of 740 mAh·g−1, which reached 90% of the theoretical specific capacity of zinc-air battery. Zeng et al. [75] integrated the catalyst, current collector, and substrate to make a new integrated cable-type zinc-air battery. By floating catalytic deposition, the catalyst and heteroatoms are loaded on CNT, and the CNT is functionalized with stretchability and improved conductivity, so that its discharge potential is as high as 1.18 V.

At present, there is not much research on cable zinc-air batteries. Although these batteries have good structure and mechanical properties, their electrochemical properties are poor. The future development trend is to manufacture zinc-air batteries with miniaturization, strong mechanical properties and excellent electrochemical properties. In-situ growth techniques, such as electrodeposition, chemical vapor deposition and electrospinning, can effectively combine the catalyst with the support. In order to improve the adhesion between the hydrogel electrolyte and the electrode, the hydrogel electrolyte precursor is usually coated on the electrode first and then solidified to integrate the air cathode, or even the cathode and electrolyte are integrated. At the same time, the development of new methods for in-situ growth of electrolytes on electrodes is crucial for the rapid promotion of FZABs.

3.2 Sandwich Structure Battery

The traditional sandwich structure zinc-air battery configuration is shown in Fig. 4b, which consists of a simple and direct stack of metal electrodes, aqueous/hydrogel electrolytes and air electrodes. The air cathode generally consists of a substrate, a catalyst, and a gas diffusion layer. However, for FZABs with sandwich configuration, people mostly only perform simple bending and twisting tests on them, and many factors need to be considered in the actual application process, such as pressure test and temperature test. At the same time, researchers have different standards for measuring FZABs. Some use bending at various angles to test the cycle performance of the battery, while others use repeated bending to measure the mechanical performance of the battery. More clear and specific standards have not yet been formulated. Therefore, it is urgent to introduce a deformation parameter and the corresponding battery performance parameter to comprehensively evaluate the performance of flexible batteries.

4 Application of Hydrogel Electrolytes in FZABs

The hydrogel electrolyte of FZABs is usually a hydrogel with a hydrophilic network structure usually composed of cross-linked hydrophilic polymer chains. The network structure absorbs water and swells and can retain a large amount of water, but is not soluble in Water, so hydrogel electrolytes usually appear soft and moist [76]. A large number of hydrophilic functional groups (such as hydroxyl, amino, carboxyl and sulfonic acid groups, etc.) on the polymer chain can produce certain weak physical interactions, resulting in the formation of hydrogen bonds between or within molecules, so that a large amount of water in the solvent can be adsorbed in the hydrogel network [77]. The electronegative groups (such as carboxyl group, amino group, etc.) on the polymer chain can effectively trap metal ions from the solvent to the polymer chain, which makes the hydrogel electrolyte have good interaction with ions [78,79]. Therefore, hydrogel electrolytes have conductivity similar to aqueous electrolytes. In addition, the cross-linking between the hydrogel network structures makes the hydrogel electrolyte have anti-dissolution properties, thus making the hydrogel electrolyte have good processability and stability macroscopically. At the same time, due to the different selection of polymer substrates and the different construction methods of network structure, hydrogel electrolytes have the characteristics of structural design and performance control. In addition, the network structure of the hydrogel electrolyte can be superimposed and regulated in multiple layers, so that the hydrogel electrolyte can qualitatively meet the application of FZABs under different conditions. Several hydrogel electrolytes currently made based on commonly used polymers are described below.

4.1 Commonly Used Hydrogels in FZABs

4.1.1 Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)-Based Hydrogel Electrolytes

Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a water-soluble polymer with properties between plastics and rubbers, and its chain-like structure and characteristic functional groups (-OH) give it high water absorption and good electrical conductivity [80–82]. As a common polymer matrix, polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is often widely used as a hydrogel electrolyte for preparation due to its excellent thermal, chemical and structural stability and environmental friendliness [83]. Table 1 lists the properties of various PVA hydrogels. PVA based gel electrolyte shows unique characteristics and significant advantages. Its three-dimensional network structure not only gives the electrolyte good flexibility and mechanical strength, but also can effectively adjust the ion transport path and improve conductivity. PVA gel electrolytes prepared by chemical or physical crosslinking methods have excellent thermal stability and low temperature resistance, and can maintain stable electrochemical performance at extreme temperatures, which is crucial to broaden the application range of devices such as supercapacitors. However, PVA based gel electrolytes also have some problems that cannot be ignored. Because of the physical hindrance of polymer matrix to ion migration, the conductivity is usually significantly lower than that of liquid electrolytes. At the same time, the strong interaction between polymer and solvent molecules (such as hydrogen bond) may change the solvation structure of ions and increase the migration activation energy. Secondly, there is an irreconcilable contradiction between its mechanical strength and high ionic conductivity: increasing the crosslinking density or concentration of PVA can enhance mechanical stability and suppress dendrite penetration ability, but inevitably leads to a decrease in polymer network pore size, obstruction of chain segment movement, and thus an increase in ion transport resistance; On the contrary, reducing polymer content or increasing plasticizer dosage to optimize ion conductivity often comes at the cost of sacrificing mechanical integrity and dimensional stability, making it prone to creep, damage, or detachment from the electrode interface during repeated deformation or long-term operation. Currently, alkaline hydrogel electrolytes based on polyvinyl alcohol (such as PVA-KOH) are the most widely used. However, pure polyvinyl alcohol polymer usually exists in linear form, so the polymer electrolyte of pure polyvinyl alcohol gel substrate has weak mechanical strength, insufficient alkali resistance and poor water retention, which leads to a rapid decline in its conductivity [84,85]. In addition, in polyvinyl alcohol gel-based polymer electrolyte, water is one of the important factors affecting its OH-conduction, which will affect the reaction kinetics of flexible zinc-air battery. Therefore, the durability and cycle life of FZABs based on PVA-KOH hydrogel electrolytes are poor. Therefore, it is very important to improve the water retention of polyvinyl alcohol hydrogel electrolyte. At present, many works in this area have been reported, mainly focusing on directly adding related additives to polymers or improving the main structure of polymers such as polymer cross-linked networks.

Fig. 6 shows some recent work on the modification of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based hydrogel electrolytes. Fan et al. [86] developed a polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based hydrogel electrolyte-PVA-SiO2 with excellent water absorption and water retention capacity by using SiO2 particles as additives (Fig. 6a). Because the surface of SiO2 is porous and rich in hydroxyl groups, it is beneficial to form hydrogen bonds with water molecules to stabilize it, which greatly improves the water retention performance of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-based hydrogel electrolyte. Zhang et al. [87] prepared a bacterial cellulose (BC)-based cellulose-potassium hydroxide-potassium iodide (BC-KOH-KI) electrolyte (Fig. 6b). Benefiting from the three-dimensional network structure, excellent hydrophilicity, and stable chemical properties of bacterial cellulose, it has ultra-high mechanical strength of 2.1 MPa and excellent ionic conductivity of 54 mS·cm−1, power density up to 129 mW·cm−2, capacity up to 794 mAh·g−1, and more than 100 cycles.

Figure 6: Modification of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) based gel polymer electrolyte (a) Schematic of PVA-SiO2. Reproduced with permission [86]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier. (b) Schematic diagram of BC-KOH-KI. Reproduced with permission [87]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (c) SA/TA schematic. Reproduced with permission [88]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier

4.1.2 Polyacrylic Acid (PAA)-Based Hydrogel Electrolytes

Polyacrylic acid (PAA) is a polymer material made by polymerization of acrylic acid monomer. Polyacrylic acid (PAA) exhibits stronger hydrophilicity due to the presence of carboxylate ions (-COO-), which forms hydrogen bonds with water molecules. Therefore, polyacrylic acid (PAA) has high ionic conductivity and excellent flexibility, making it an ideal material for preparing alkaline polymer electrolytes. At the same time, PAA based gel electrolyte has high liquid absorption rate and excellent ionic conductivity. Its network structure can be optimized by adjusting the monomer ratio and cross-linking density to meet the needs of different electrolytes. This electrolyte exhibits good chemical and thermal stability, and can maintain stable performance over a wide temperature range. It plays a significant role in improving battery cycle life and safety, and is particularly suitable for applications in high-performance energy storage systems. Wang et al. [97] prepared a polyacrylic acid (PAA)-based hydrogel electrolyte, and its ionic conductivity was measured as high as 0.282 S·cm−1, and compared its performance with that of pure polyvinyl alcohol-based alkaline hydrogel electrolyte (PVA-KOH) flexible zinc-air battery, the power density of flexible zinc-air battery based on polyacrylic acid (PAA)-based hydrogel electrolyte can reach a maximum of 108 mW·cm−2, 3 times the performance of a PVA-KOH flexible zinc-air battery (39 mW·cm−2).

Although PAA based gel electrolyte has many advantages, it also has some disadvantages. For example, in the long-term cycle process, the chemical stability of the electrolyte may be limited by the hydrolysis reaction of the PAA chain, especially in the high temperature or humidity environment, which may affect the long-term performance of the battery. In addition, the preparation process of gel electrolyte is relatively complex and costly, and the consistency and repeatability in large-scale production are also problems that need to be solved. In addition, although the pure polyacrylic acid (PAA) hydrogel electrolyte is highly conductive, the high water content in turn makes the PAA soft and brittle, resulting in its poor mechanical properties. Therefore, it is a beneficial research content to optimize the comprehensive properties of PAA gel electrolyte with PAA hydrogel as the backbone by adopting a hybrid copolymerization and performance improvement strategy [98,99].

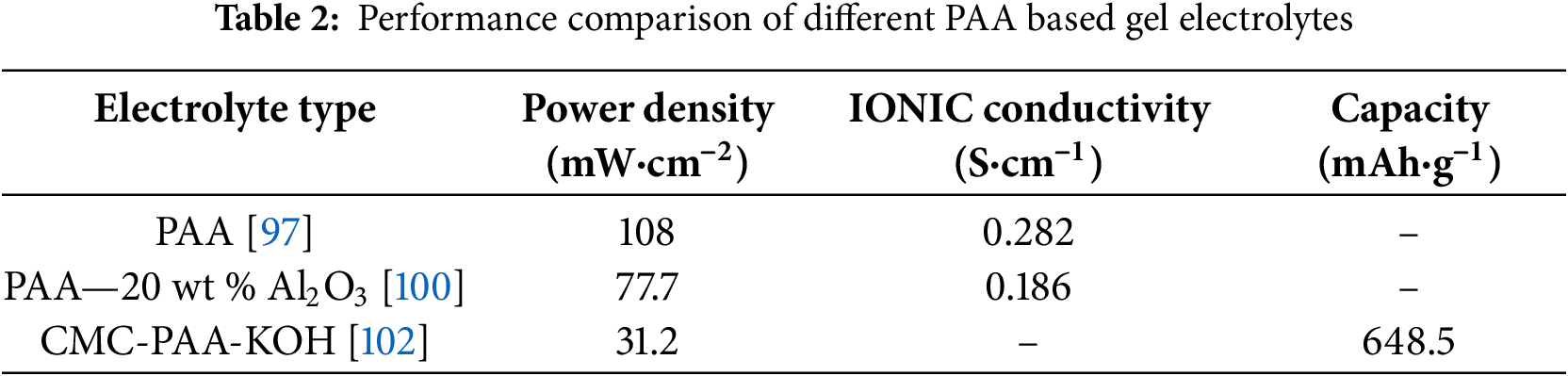

Fig. 7 shows some recent work on the modification of polyacrylic acid (PAA)-based hydrogel electrolytes. Song et al. [100] prepared a composite gel electrolyte containing Al2O3 filler based on PAA for FZABs (as shown in Fig. 7a). Through data comparison, the ionic conductivity of the synthesized PAA-20 wt% Al2O3 hydrogel electrolyte was 186 mS·cm−2. The assembled solid-state battery has a long cycle life of 384 h and a power density of 77.7 mW·cm−2. Pei et al. [101] synthesized alkalized PAA (A-PAA) hydrogel based on DFT calculation results (as shown in Fig. 7b), introducing a higher density of polar terminal groups within the hydrogel enhances the anchoring of water molecules through robust interactions with these groups. This simultaneously disrupts hydrogen-bonding networks, effectively inhibiting ice crystal formation. Consequently, the polyelectrolyte exhibits exceptional freezing tolerance and thermal stability, enabling operation across a broad temperature spectrum from 30°C to 80°C. Utilizing this approach, Qu et al. [102] employed sodium carboxymethyl cellulose-polyacrylic acid alkaline gel (CMC-PAA-KOH) as a gel polymer electrolyte (GPE) preparing a sandwich-type flexible zinc-air battery. (as shown in Fig. 7c) with a capacity of 648.5 mAh·g−1 and a power density of 31.2 mW·cm−2 at a current density of 2 mA·cm−2. The comparison of relevant parameters is shown in Table 2.

Figure 7: Modification of polyacrylic acid (PAA) based gel polymer electrolyte (a) Schematic diagram of PAA-20 wt% Al2O3. Reproduced with permission [100]. Copyright 2022, American Chemical Society. (b) A-PAA schematic. Reproduced with permission [101]. Copyright 2021, Royal Society of Chemistry. (c) Schematic of CMC-PAA-KOH. Reproduced with permission [102]. Copyright 2022, Wiley

4.1.3 Polyacrylamide (PAM)-Based Hydrogel Electrolytes

Polyacrylamide (PAM)-based hydrogel electrolytes have been widely used as well-established polymer electrolytes in zinc-air batteries [103]. PAM based gel electrolyte has good flexibility and surface adhesion. Its internal polymer chain can effectively attract electrolyte ions while maintaining ionic conductivity similar to that of liquids. This electrolyte has a solid like stability and is not easily leaked under stress, which can improve the cycling stability and lifespan of the battery. In addition, PAM based gel electrolytes have excellent mechanical and electrochemical properties, which are suitable for the application of flexible energy storage devices. As a high-performance polymer material, polyacrylamide (PAM) has significant advantages in electrical conductivity, water absorption/retention, alkali resistance, and mechanical strength, making it one of the most popular hydrogel electrolytes in the field of flexible/solid-state zinc-air batteries. The amide groups in the structure of polyacrylamide (PAM) tend to form hydrogen bonds with water and the polymer chain itself, so the polyacrylamide (PAM) gel exhibits sufficient water absorption and remarkable deformation characteristics (Table 3 lists the relevant characteristics of several types of polyacrylamide). Miao et al. [104] successfully developed a new type of polyacrylamide (PAM) alkaline gel electrolyte (as shown in Fig. 8a) through in-situ polymerization technology, with an ionic conductivity as high as 215.6 mS·cm−2 and excellent water retention and toughness. At the same time, the flexible zinc-air battery based on this electrolyte can maintain a low voltage difference when the measured maximum power density reaches 105 mW·cm−2 and the charge and discharge cycle is performed at a current density of 5 mA·cm−2, thus proving its excellent cycle stability. It is worth mentioning that this battery can maintain stable operation even under physical stresses such as bending, deformation or cutting, showing its extraordinary mechanical flexibility and durability.

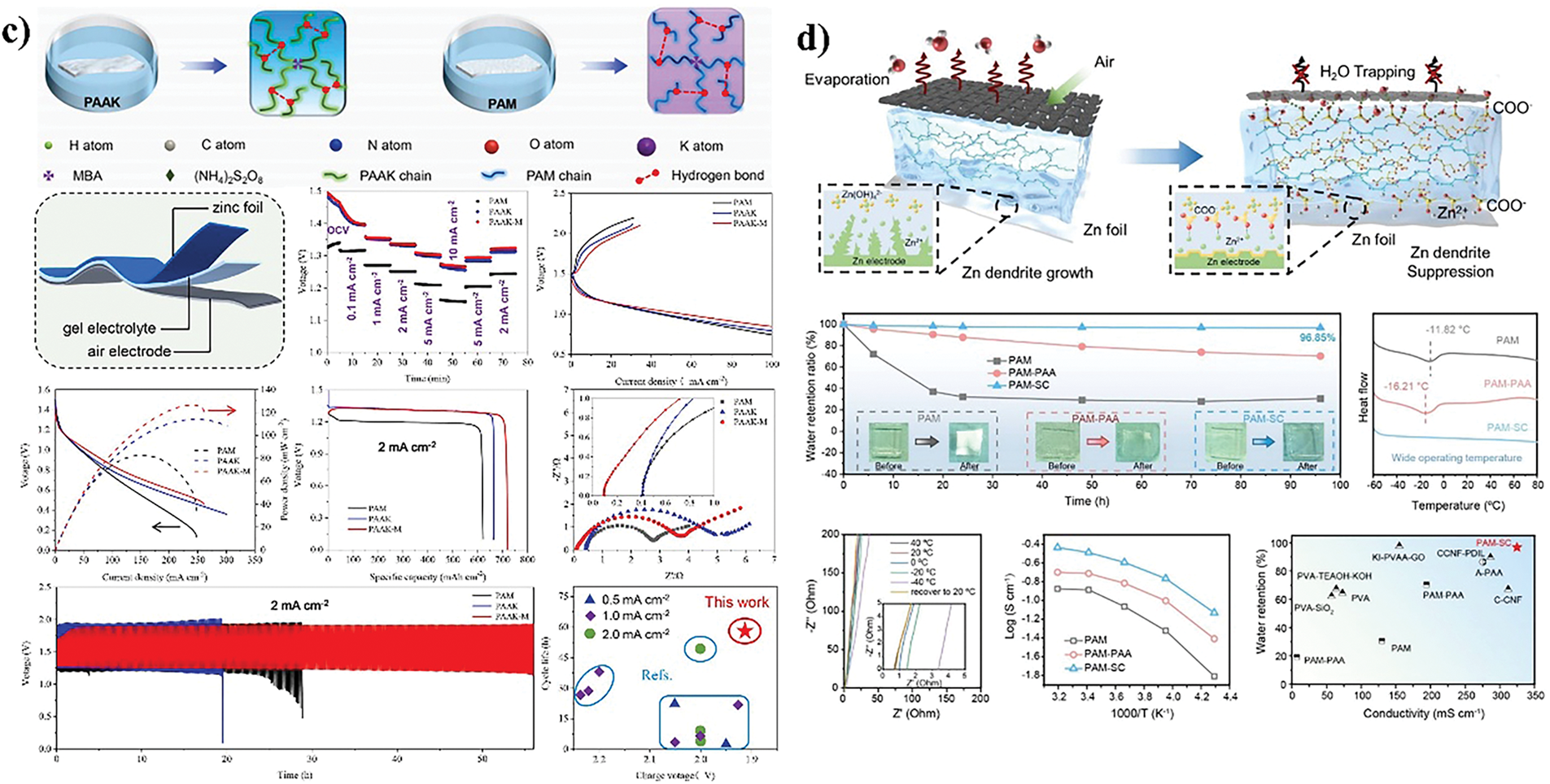

Figure 8: Modification of polyacrylamide (PAM) based gel polymer electrolyte (a) PAM schematic. Reproduced with permission [88]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier. (b) PAM/G-CyBA schematic. Reproduced with permission [105]. Copyright 2020, Royal Society of Chemistry. (c) PAM-PAAK schematic. Reproduced with permission [106]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier. (d) PAM-SC schematic. Reproduced with permission [107]. Copyright 2023, Wiley

Moreover, polyacrylamide (PAM) can be branched or reticulated by grafting or crosslinking, which helps to achieve the construction of specific structures and improve the overall performance [107]. The hydrogel electrolyte of guanosylcyclohexylboronic acid (G-CyBA) and polyacrylamide (PAM) prepared by Xu et al. [105] showed excellent frost resistance and drying resistance in the temperature range of −80°C to 100°C) while maintaining uncompromised ionic conductivity. The supramolecular interplay between G-CyBA assemblies and PAM networks immobilizes water molecules within the dual-network architecture (SP-DN), effectively inhibiting ice nucleation (as shown in Fig. 8b). Zhang et al. [106] architected a dual-crosslinked gel electrolyte by integrating PAM with poly(acrylic acid potassium) (PAAK) for sandwich-configuration zinc-air batteries, achieving peak power density of 126 mW·cm−2 and specific capacity of 731 mAh·g−1 at 2 mA·cm−2 (as shown in Fig. 8c). Jiao et al. [107] fabricated flexible zinc-air batteries employing PAM-sodium citrate gel (PAM-SC) as the electrolyte matrix (as shown in Fig. 8d), with zinc foil anodes and FeCo-activated carbon (FeCo-AC) cathodes. The anionic-COO− moieties generate interfacial electric fields that homogenize ion flux to suppress dendritic growth, while interchain electrostatic forces immobilize H2O molecules via coordination, significantly decelerating dehydration kinetics.

PAM based gel electrolytes have some inherent shortcomings in their applications, which limit their application potential in some high-performance battery systems. For example, PAM based electrolytes are sensitive to temperature changes, and their ion conductivity may significantly decrease at extreme temperatures, affecting the overall performance of the battery. In addition, the hydrophilicity of PAM materials may lead to electrolyte water absorption and expansion in high humidity environments, thereby reducing their mechanical strength and structural stability. During long-term operation, PAM based gel electrolytes may exhibit performance degradation, which may be related to the chemical degradation of the electrolyte, physical structure changes, or the interface reaction between the electrode and the electrolyte. In addition, certain chemical reagents or additives that may be used in the preparation process of electrolytes may have an impact on the safety and environmental friendliness of batteries, which are important factors to consider when using PAM based gel electrolytes. Furthermore, from a cost-benefit perspective, the production cost of PAM based materials may be relatively high, which can also affect their competitiveness in the market.

4.1.4 Poly (Ionic Liquid) Hydrogels

Poly (ionic liquid) hydrogels (PIL-HGs) are multifunctional materials constructed by embedding ionic liquid monomer or functionalized ionic liquid into three-dimensional cross-linking networks. Their core advantages lie in the synergism and structural designability of ionic liquid molecules in materials. As a structural unit or additive, ionic liquids can significantly improve the conductivity of hydrogels through their inherent high ionic conductivity (usually up to 10−2 to 10−3 S/cm). At the same time, their adjustable cation/anion combinations (such as imidazole type, pyridine type cation and nitrate, ditrifluoromethane sulfonimide anion) can precisely control the polarity, solubility and thermal stability of materials. In addition, the mechanical properties of PIL HGs are significantly enhanced through the synergistic optimization of dynamic cross-linking networks (such as dynamic covalent bonds, hydrogen bonds, or metal coordination bonds) and non covalent interactions. For example, the introduction of dynamic chemical bonds endows the material with self-healing and fatigue resistance (cycling stability >1000 cycles), while the regulation of cross-linking density balances flexibility and strength. Its environmental responsiveness originates from the coupling effect between ionic liquids and external stimuli (pH, temperature, ionic strength), making the material widely adaptable in fields such as smart sensing and flexible electronics. Furthermore, the biocompatibility (cytotoxicity <5%) and degradability (enzymatic degradation rate >80%) of PIL HGs have expanded their potential applications in the biomedical field. By modifying with nano fillers or functional groups, their antioxidant, frost resistance, and interface compatibility can be further optimized, demonstrating unique comprehensive performance advantages in energy devices, tissue engineering, and sustainable material design. Han et al. [109] designed a new semi interpenetrating ionic liquid network hydrogel (PATV) by in-situ polymerization of acrylamide (AM)/N-(tri(hydroxymethyl)methyl) acrylamide (THMA)/1 vinyl 3-butyl imidazole tetrafluoroborate (VBIMBF4). Density functional theory calculation shows that the polyionic liquid chain in the hydrogel network is used as the cross-linking point to build a hydrogen bond network. Hydrogen bonding networks can effectively and rapidly dissipate energy, avoiding stress concentration and high hysteresis.

4.1.5 Polyphosphate Based Hydrogel

The polyphosphate based hydrogel is a three-dimensional cross-linked network hydrogel constructed by polyphosphates, whose core advantage lies in the versatility and structural adjustability of polyphosphates. Polyphosphate, as a naturally occurring biocompatible molecule, endows hydrogels with excellent ion exchange ability, pH responsiveness and biocompatibility through its high charge density and multivalent anion characteristics. Its cross-linked network is formed through phosphodiester or phosphodiester bonds, which can adjust the cross-linking density and network topology, thereby optimizing mechanical properties (such as toughness and strength) and swelling behavior. Polyphosphate based hydrogels have potential applications in biomedical fields such as tissue engineering, drug controlled release and wound healing due to their antioxidant, antibacterial and biodegradable properties. In addition, its environmental responsiveness (such as temperature, pH, ion strength) gives it unique performance advantages in smart sensing, flexible electronics, and sustainable material design. By functionalizing or composite nanofillers, their applications in energy storage and conversion, environmental monitoring, and water treatment can be further expanded. Zhou et al. [110] prepared hydrogels by cross-linking long-chain polyphosphates with metal ions, and proposed the concept of inorganic polymer hydrogels. The obtained inorganic polymer hydrogel not only has excellent flexibility and extensibility, but also has good electrical conductivity, self repair, non combustibility and degradability.

4.1.6 Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogel Electrolytes

Since polysaccharide-based hydrogel-based electrolytes are made from biologically derived polymers, they are generally inherently biocompatible and biodegradable. On the other hand, OH, OR, OR, COO groups in polysaccharides can act as transport sites for metal ions, promoting the transport of metal ions. At present, there are three main types of polysaccharide substrates used to synthesize hydrogels-cellulose, chitosan and alginate [111] Among them, cellulose is rich in hydroxyl groups, which can easily prepare hydrogels with certain properties and structures [112]. Cellulose based gel electrolytes exhibit excellent characteristics, including good biocompatibility and environmental friendliness. Their porous structure and rich surface hydroxyl groups make them have excellent adsorption capacity and ion conduction performance, which can effectively inhibit the precipitation of zinc ions and dendritic growth, improve the cycle stability and energy efficiency of batteries, while maintaining high mechanical strength and flexibility, and are suitable for the application of high-performance energy storage devices. Chitosan is a cationic copolymer with good biocompatibility and biodegradability due to its hydrophilicity and degradation ability. In addition, chitosan can be easily extracted from various marine arthropods and other organisms, and its production cost is also low [113]. Chitosan based gel electrolyte, whose natural polysaccharide structure can form a stable three-dimensional network, provides excellent ion conduction path and mechanical strength, and has high affinity for electrolyte salts to ensure the stability and safety of the battery during operation. It is suitable for developing environment-friendly high-performance energy storage systems. Alginate is also a widely known polysaccharide material and is one of the most widely used polysaccharide substrates for the synthesis of hydrogels due to its biodegradability, biocompatibility, and non-toxic properties. Sodium alginate based gel electrolyte has high ionic conductivity and good water retention ability. Its rich hydroxyl and carboxyl functional groups can form a stable cross-linked structure with metal ions, enhance the mechanical strength and chemical stability of the electrolyte, and show good compatibility with zinc and other metal electrodes, reduce dendritic formation, thus improving the safety and cycle life of the battery. As mentioned earlier, Zhang et al. [87] prepared a cellulose-potassium hydroxide-potassium iodide (BC-KOH-KI) electrolyte based on bacterial cellulose (BC) (Fig. 6b). Thanks to the three-dimensional network structure, excellent hydrophilicity and stable chemical properties of bacterial cellulose, the prepared hydrogel electrolyte has good mechanical and electrochemical properties. Zhang et al. [88] engineered a dual-network gel polymer electrolyte comprising tannic acid (TA) and sodium alginate (SA). Rich polyfunctional moieties (e.g., carboxyl and hydroxyl groups) in both components enable multidentate coordination with Zn2+ ions, simultaneously suppressing water reactivity and establish Zn2+ transmission channels. A uniform deposition of zinc on the anode is thereby achieved (Fig. 6c). Table 4 lists the performance comparison of common gel electrolytes.

Although these three materials have obvious advantages, their disadvantages cannot be ignored. Cellulose based gel electrolyte has good biocompatibility and environmental friendliness, but its ionic conductivity is limited by the hydrophilicity of cellulose, and it is easy to shrink in a dry environment, affecting the stability and service life of the battery. Although chitosan based electrolytes have excellent biocompatibility and antibacterial properties, their mechanical strength may decrease in humid environments, and their affinity for electrolyte salts is limited, resulting in insufficient ionic conductivity. Although sodium alginate based electrolytes have good water retention and ion conductivity, their chemical stability may be challenged under extreme conditions, especially pH sensitivity, easy degradation, and affect the overall performance of the battery. In addition, the preparation process of these natural polymer electrolytes is complex and costly, which is not conducive to large-scale commercial applications.

By comprehensively comparing the thermal stability and environmental adaptability of various hydrogels, it can be concluded that PVA based gel electrolytes exhibit high thermal stability and can maintain the stability of their structure and performance in a wide temperature range, but they are more sensitive to changes in environmental humidity, and high humidity can lead to a decline in their performance. PAA based electrolytes are known for their excellent thermal and chemical stability, which can maintain good electrochemical performance at extreme temperatures. However, their performance in low humidity environments needs to be improved. PAM based gel electrolyte has good water resistance and certain thermal stability, and is suitable for use in wet environment. However, its stability is slightly insufficient in high temperature environment, and it is vulnerable to oxidation. Polysaccharide based gel electrolytes, including cellulose, chitosan and sodium alginate, have good biodegradability and environmental friendliness, but they show different thermal stability, especially the possible degradation and structural changes under high temperature conditions, which limit their application range. In addition, polysaccharide based electrolytes are sensitive to changes in environmental humidity and pH, which poses challenges to their long-term stability and performance. Table 5 shows the changes in conductivity of different hydrogel systems at different temperatures.

According to the above data, PVA based hydrogels show certain adaptability in extreme temperature environments. Although their conductivity decreases at low temperatures, they remain stable, and are suitable for use as flexible electronic devices in cold environments; The conductivity of PAM based hydrogels at different temperatures shows a strong temperature dependence. The conductivity increases at high temperatures, which is conducive to efficient energy transmission in warm environments; The conductivity of PAA based hydrogel changes slowly in a wide temperature range, especially in low temperature areas, which indicates that it has the potential to act as a sensor or electronic component in extreme low temperature environments, such as polar scientific research or space exploration, and can ensure the normal operation of equipment and the stability of data transmission under extreme conditions.

4.2 Design Strategy of Gel Electrolyte

The design strategy of gel electrolyte covers multiple levels from material selection to structural optimization to improve its performance in the zinc air battery. When selecting polymer matrix, its chemical stability, ion conductivity and mechanical strength will be considered. Common polymers such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA), polyacrylic acid (PAA), etc. can adjust their microstructure and physicochemical properties through cross-linking or copolymerization modification. Adding functional monomer or nano filler, such as graphene oxide or metal oxide, can further enhance the conductivity and mechanical strength of the electrolyte, while improving the compatibility and stability of the electrode/electrolyte interface. In terms of utilizing polymer transport dynamics, by regulating the chain segment motion and network structure of polymers, optimizing the ion transport path, the glass transition temperature and crystallinity of polymers are key factors affecting ion conduction. By adjusting these parameters, the ion conductivity of electrolytes can be improved at different temperatures while maintaining their flexibility. In addition, by utilizing the hydrophilicity or hydrophobicity of polymers, the water absorption and retention capacity of electrolytes can be controlled, thereby affecting the transport and deposition behavior of zinc ions. In order to achieve practical zinc air batteries, in addition to optimizing the electrolyte itself, it is also necessary to consider the matching of the electrolyte and electrode materials, including the protection of the zinc negative electrode and the catalytic activity of the air positive electrode. Through interface engineering strategies such as in-situ generation of protective films or introduction of redox media, the growth of zinc dendrites can be effectively suppressed and the kinetics of the oxygen reduction reaction of the positive electrode can be improved. In combination with these design strategies, gel electrolyte should not only meet the requirements of high ionic conductivity and wide electrochemical window in electrochemical properties, but also have sufficient flexibility and stability in mechanical properties to adapt to the volume change and long-term use requirements of the battery in the charge discharge cycle. Through fine material design and performance optimization.

4.3 The Deficiency of Hydrogel Electrolytes in FZABs

Although hydrogel electrolytes can effectively inhibit the growth of dendrites and the occurrence of side reactions, and achieve a good balance of mechanical properties, safety and environment, there are still some problems hindering their further development and flexible battery systems.

4.3.1 Lower Ionic Conductivity

As we all know, the generation of battery current comes from the directional movement of ions in the electrolyte, so the transmission process of ions in the electrolyte has a great influence on battery performance. In aqueous electrolytes, ions can move freely under the surrounding of water molecules and under the action of an electric field between the cathode and anode. However, in a hydrogel electrolyte, since comprising an ionic solution and a gel polymer matrix, this electrolyte utilizes the solution for ionic conduction while the gel polymer provides a structural network framework. Invariably, ion transport is constrained by the presence of non-conductive gel polymer chains and the crystallization occurring within locally aligned regions of the polymer (Fig. 9a).

Figure 9: Schematic diagram of hydrogel electrolyte. (a) Still existing problems with hydrogel electrolytes. Reproduced with permission [126]. Copyright 2023, Wiley. (b) Schematic diagram of zinc-air battery electrode-electrolyte composite. Reproduced with permission [119]. Copyright 2022, Wiley. (c) Schematic diagram of “water in salt” double network hydrogel electrolyte. Reproduced with permission [123]. Copyright 2022, Wiley. (d) Deposition behavior of zinc battery using 6P-PAM electrolyte. Reproduced with permission [125]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier

4.3.2 Thermodynamically Unstable Hydration

Within gel polymer electrolytes comprising polymeric scaffolds and solvated ionic species, water simultaneously mediates ion dissociation and vehicular transport [116]. However, during the long-term charging cycle, the water in the hydrogel electrolyte will continue to decrease with the transpiration of water. In addition, during the charging process (as shown in Eq. (7)), the zinc-air battery will generate water at the air cathode and escape from the open structure of the air cathode, thus accelerating the reduction of the water content of the hydrogel electrolyte, thereby reducing the ionic conductivity of the disguised hydrogel electrolyte, and ultimately leading to the degradation of the performance of the flexible zinc-air battery.

4.3.3 Lower Electrode Affinity

As we all know, zinc-air battery reactions mainly occur at the three-phase interface between electrolyte, electrode and air (such as zinc deposition and shedding during charging and discharging). Therefore, guaranteeing the unimpeded progression of the three-phase interface reaction constitutes a critical prerequisite for ensuring battery performance. This reaction necessitates the coordinated participation of mobile ions within the electrolyte and electrons transferred at the electrode interfaces. Suboptimal interfacial contact between the electrode and the gel polymer electrolyte consequently elevates interfacial impedance and induces non-uniform spatial distribution of current density. These effects manifest as elevated charge/discharge overpotentials and diminished Coulombic efficiency. So the contact between the electrode and electrolyte interface is one of the important factors affecting battery performance.

4.3.4 The Growth of Zinc Dendrites

Zinc air batteries exhibit certain zinc dendrite growth phenomena, and the growth mode of zinc dendrites is mainly influenced by the migration and deposition behavior of zinc ions in the electrolyte. The uneven distribution of zinc ions on the electrode surface leads to dendrite nucleation and growth, which is particularly evident during battery cycling and may result in battery short circuits and performance degradation. As a form of electrolyte, hydrogel can effectively control the migration and deposition of zinc ions through its unique three-dimensional network structure and hydrophilicity. There are two main methods for hydrogel to inhibit zinc dendrite growth: one is chemical inhibition, which improves the solvation structure of zinc ions and induces uniform zinc deposition through the interaction between functional groups and zinc ions. However, the strength of these hydrogel electrolytes is usually very low; The second is mechanical suppression. Increasing the modulus of the hydrogel electrolyte is the simplest and most direct way to protect the zinc anode. However, hydrogel electrolytes are difficult to achieve high modulus due to their inherent high water content, and reducing the water content will greatly decrease the ionic conductivity. Therefore, it is very difficult to design hydrogel electrolytes with high water content and high modulus. Chen et al. [117] chose three methods, namely wet annealing, solvent replacement and salting out, to develop a hydrogel electrolyte with uniform polymer conformation, ultra-high modulus and high water content. This strategy utilizes phase separation to avoid the contradiction between ion conductivity and mechanical strength, breaking through the limitations of previous hydrogel electrolyte design strategies.

4.3.5 Poor Ability to Resist Carbon Dioxide

The poor tolerance of hydrogel materials to carbon dioxide (CO2) is essentially due to the strong coupling effect between their structural characteristics and the chemical reaction kinetics of CO2 molecules in the aqueous phase [118]. This coupling effect leads to significant degradation of their long-term performance by destroying the alkaline microenvironment of hydrogels, causing structural degradation and interfering with the stability of ion transport channels. Specifically, hydrogel electrolytes usually rely on alkaline conditions (such as the high concentration of hydroxyl ion OH−) to maintain ionic conductivity and electrochemical stability, while CO2 molecules will undergo multi-step chemical reactions after dissolution in the hydrogel network: first, CO2 combines with water molecules to generate unstable carbonic acid (H2CO3), then dissociate into bicarbonate (HCO3−) and carbonate (CO32−), and release protons (H+), which leads to the dynamic reduction of local pH values. Due to the existence of a large number of free water and hydrophilic functional groups (such as carboxylic acid group, amino group, etc.) in the hydrogel network, the diffusion and reaction rate of CO2 is significantly higher than that of gas phase or hydrophobic materials, thus accelerating the continuous decline of pH value. This destruction of the acid-base balance not only weakens the concentration of OH−, but also changes the ion distribution in the hydrogel through the charge neutralization effect, which interferes with the ion transport mechanism that originally depended on OH−. For example, the interaction between OH− and H+ may lead to the reconstruction or blocking of the ion migration path, thus reducing the overall conductivity. During long-term operation, the continuous absorption of CO2 will cause the structural evolution of the hydrogel network and irreversible consumption of functional groups, further exacerbating its performance degradation. For example, the alkaline functional groups in the hydrogel (such as quaternary ammonium salt, amino group or carboxylate) may react with CO2 to generate stable carbonate or bicarbonate, thus losing the original alkaline characteristics; At the same time, the pH reduction induced by CO2 may promote the hydrolysis of some sensitive chemical bonds (such as ester bonds and amide bonds) in the hydrogel, leading to the fracture of the cross-linked network or abnormal changes in swelling behavior. This structural degradation not only reduces the mechanical strength of the hydrogel, but also indirectly affects the continuity of the ion transport channel by changing the porosity and network connectivity. In addition, the absorption of CO2 may induce interfacial polarization at the interface between the hydrogel and the electrode: when the pH value decreases, the metal electrode (such as the zinc electrode) surface may produce by-products (such as ZnO or ZnCO3) due to corrosion or oxidation, and these by-products will deposit at the electrolyte electrode interface, forming a high impedance layer, which will hinder the rapid migration of ions. More complicated is that the long-term effect of CO2 will also affect the dynamic balance of the hydrogel through the dynamic process. For example, in an open system, the continuous absorption of CO2 may lead to the accumulation of carbonate/bicarbonate, forming a nonlinear feedback mechanism; In a closed system, the accumulation of CO2 may lead to local supersaturation, leading to precipitation of carbonate crystals, destroying the homogeneity of hydrogels and introducing micro cracks. These structural defects not only reduce mechanical properties, but also become short-circuit paths or dead zones for ion transport, significantly weakening its conductivity efficiency.

4.4 Potential Improvement Using Hydrogel Electrolytes in FZABs

As mentioned above, hydrogel electrolytes still have problems such as low ionic conductivity, poor water retention and low electrode affinity. Therefore, current research mainly focuses on improving the ionic conductivity and water retention of hydrogel electrolytes. In terms of capacity and electrode affinity, related work and mainstream solutions will be introduced below.

4.4.1 Improving Ionic Conductivity

(1) Construction of ion transport channels

Because there are some specific functional groups on the molecular chain of gel polymer electrolyte, ions can not only be dissolved in water for migration, but also coordinate with specific functional groups in gel polymer, thus accelerating the migration of ions in the electrolyte. Therefore, it is possible to construct a gel polymer electrolyte with functional groups that can coordinate with related ions, so as to induce orderly ion transport by constructing ion transport channels and improve the ionic conductivity of gel polymer electrolyte.

As shown in Fig. 9b, Hui et al. [119] developed an integrated zinc-air battery electrode-electrolyte composite by depositing zinc on MXene, absorbing Co2+ to form ZIF-67, converting it into LDH array, connecting with PVA, and immersing in KOH, the fabricated uniformly aligned LDH array surface contains abundant OH− to Provide conduction channels for hydroxide ion.

(2) Hydrogel electrolyte incorporating ionic liquids

Ionic liquids (ILs) intrinsically impart exceptional ionic conductivity to electrolytes, while their constrained water content suppresses hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) kinetics and by-product formation. Beyond augmenting IL concentration for enhanced conductivity, functional additives may be incorporated to fine-tune IL properties.

Hu et al. [120] engineered a PVDF-HFP matrix-supported IL gel electrolyte. Through synergistic integration of copper ions as catalytic centers, this design facilitates accelerated Zn2+ deposition/stripping dynamics, reduces charge-transfer energy barriers at the electrolyte-electrode interface, and significantly impedes hydrogen evolution alongside parasitic by-product generation.

(3) Suppressing autonomous crystallization in hydrogels

Similar to inorganic compounds, gel polymers undergo crystallization processes. Moderate crystallinity enhances mechanical robustness and functional performance, whereas excessive crystalline formation densifies the polymer architecture, impeding ionic mobility through increased diffusion barriers. Select additives disrupt polymer crystallization, inducing structural loosening within the gel matrix. This creates expanded ion-conducting pathways, thereby elevating ionic conductivity.

Jiang et al. [121] enhanced ionic mobility by integrating negatively charged soy protein isolate nanoparticles (SPI) into crosslinked polyacrylamide hydrogels bearing cationic moieties. Electrostatic interactions between oppositely charged groups disrupted polymeric crystallinity, facilitating ion migration through the hydrogel network. Alternatively, Liu et al. [122] employed TiO2 nanosheets—synthesized via single-step hydrothermal conversion of Ti3C2TxMXene—as additives in PVA-based electrolytes. These nanoadditives increased the amorphous domain fraction within the PVA matrix, substantially improving gel electrolyte conductivity.

4.4.2 Enhancing Moisture Retention Properties

(1) Hydropathic moiety

Gel polymers incorporating polar moieties (e.g., carboxyl, hydroxyl, amino, and sulfonic groups) along their chains strengthen electrostatic interactions between electrolytes and water molecules. This effectively confines water within the electrolyte matrix, significantly enhancing hydration retention capabilities. Liu et al. [122] fabricated a poly(acrylic acid potassium)-KOH (PAAK-KOH) hydrogel electrolyte. Relative to aqueous KOH solutions, this system exhibited superior water retention properties, attributable to the intense hydration activity of polymer-bound carboxyl groups that suppress water evaporation. After 90 days of storage, the PAAK-KOH electrolyte demonstrated merely 19.3% mass variation.

(2) Aerial moisture capture

The semi-open architecture of zinc-air batteries permits full air-electrolyte interfacial contact, while ambient humidity provides exploitable moisture sources. This enables atmospheric vapor sequestration for sustaining hydration in gel polymer electrolytes. Zhang et al. [123] engineered a biomimetically architected “water-in-salt” dual-network hydrogel electrolyte, inspired by desert cacti. Through synergistic dipole-solvent affinity and ion-solvent interactions, airborne water molecules are spontaneously sequestered by the electrolyte (as shown in Fig. 9c). Subsequent osmosis-driven mass transfer delivers captured moisture to the electrolyte bulk, replenishing cathode-depleted water and maintaining room-temperature dynamic hydration equilibrium.

4.4.3 Enhancing Electrode-Electrolyte Interfacial Adhesion

(1) Zinc-deposition guiding motifs

Incorporating zincophilic moieties into gel polymer matrices confers robust viscoelasticity and enhanced zinc coordination capability, thereby strengthening interfacial cohesion with zinc electrodes. Li et al. [124] engineered an adhesive gel polymer electrolyte via initiator-free copolymerization at ambient temperature. Surface-exposed catecholic functionalities establish conformal interfaces with both electrodes, substantially diminishing interfacial impedance while augmenting charge-transfer efficiency across electrode-electrolyte junctions.

(2) Photocuring fabrication of conformal-adherent hydrogel electrolytes

Fabricating adhesive polymer electrolytes through non-covalent crosslinking not only strengthens electrode-electrolyte interfacial cohesion, but also extends service life via enhanced self-repair capabilities. Wang et al. [125] engineered a hydrogen-bond enriched hydrogel electrolyte by polymerizing acrylamide and diallylamine (denoted xP-PAM, where x represents diallylamine weight percentage) with polypyrrole modification (Fig. 9d). This design establishes conformal zinc-electrolyte interfaces through abundant hydrogen-bonding networks, significantly improving zincophilic coordination while ensuring intimate anode contact.

4.4.4 Cytocompatible Profile Coupled with Ecological Mineralization

As previously detailed for nature-derived polysaccharides, gel polymers sourced from biological precursors exhibit intrinsic non-toxicity, ecological benignancy, superior biotolerability, and programmable biodegradation. These attributes confer significant translational promise for wearable biodevices and biomedical engineering applications. This section showcases representative biocompatible gel polymer electrolyte systems and their constituent biomaterials. Despite current limited adoption in wearable and clinical settings, their therapeutic integration potential in next-generation medical technologies remains substantial.

(1) Alginate-coordinated electrolytic hydrogels

Alginate, a marine-derived polysaccharide extracted from brown algae, is extensively utilized owing to its exceptional biotolerability, programmable biodegradation, and food-grade safety. Economically scalable production further ensures cost-effectiveness. Its inherent chain-entanglement propensity enables facile hydrogel formation with elevated viscoelasticity, thereby reconstructing electrochemical double-layer interfaces to diminish interfacial resistance. Beyond established applications in food technology, pharmaceutical delivery, and biomedical engineering, alginate-based matrices demonstrate unique zinc anode preservation capabilities in aqueous zinc batteries. Specifically, carboxyl moieties exhibit pronounced zincophilic coordination, homogenizing ion flux distribution to suppress dendritic propagation while extending functional electrolyte longevity. Fan et al. [127] engineered stabilized zinc anodes via conformal coating of bioinspired alginate gel (Alg-Zn) and acetylene black (AB) as interfacial modifiers. These modifiers orchestrated directional Zn2+ migration through carboxyl-architected ion channels, expanding nucleation sites to reduce overpotential (47 mV) while inhibiting dendrite formation. Consequently, symmetrical cells achieved ultralow polarization and sustained 500-h cyclability. Synergizing biocompatibility with electrochemical robustness, alginate hydrogel electrolytes emerge as prime candidates for epidermal and implantable zinc-air batteries.

(2) Agarose-galactan complex

Agarose-derived gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs), a plant-sourced phycocolloid extractable from diverse marine flora, exhibit intrinsic non-toxicity, cytocompatible adhesion, programmable biodegradation, and cost efficiency. These attributes position them as prime candidates for implantable zinc battery systems. Zuo et al. [128] architected an eco-conscious agar-based hydrogel electrolyte for zinc-air batteries. To augment mechanical robustness and electrochemical functionality, triazine-structured melamine foam was incorporated as a skeletal reinforcement scaffold. The resulting melamine-agarose GPE-enabled ZAB delivered exceptional volumetric capacity (24 mAh·cm−2), peak power density (126 mW·cm−2), and cryogenic-to-desert thermal resilience—critical for subdermal bioelectronics and epidermal wearables.

Solid state electrolytes are considered the core of next-generation battery technology due to their excellent safety, high energy density, and wide operating temperature range [129]. Their non flowing properties effectively avoid the risk of leakage and combustion of traditional liquid electrolytes, while supporting higher voltage windows and faster charging rates, thus meeting the demand for high-performance batteries in applications such as electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. The transition from gel system to solid electrolyte may involve the modification of existing gel electrolyte materials, including enhancing their mechanical strength and ionic conductivity, and reducing interface problems with electrode materials. Scientific researchers can achieve these goals by introducing nano fillers or conducting cross-linking modification of polymer networks. In addition, developing a mixed electrolyte system, such as embedding solid electrolyte particles into the gel matrix to form a composite electrolyte with both liquid and solid advantages, is also a feasible transition strategy. Finally, the research may turn to the development of new solid electrolyte materials, such as polymer or inorganic materials with high ionic conductivity, which can work directly in solid state, so as to realize the smooth transition from gel system to completely solid electrolyte. This process not only requires the innovation of material science, but also depends on the in-depth understanding and optimization of electrolyte/electrode interface.

4.4.6 Improve the Ability to Resist Carbon Dioxide

The core of improving the ability of hydrogel to resist carbon dioxide (CO2) is to regulate its chemical structure [130], physical network and interface characteristics through material design and functional modification, so as to inhibit the pH decline, ion transport retardation and structural degradation induced by CO2. Firstly, in terms of material design, strong alkaline functional groups (such as quaternary ammonium salts and piperazine groups) can be introduced or hyperbranched structures (such as polyamide amine PAMAM) can be constructed. These groups efficiently capture CO2 molecules to form stable carbonates or amino formates, thereby reducing the concentration of free H+ and buffering the dynamic changes in pH value; At the same time, the hyperbranched structure increases the complexity of the diffusion pathway of CO2 by increasing the cross-linking density and porosity, and also limits the direct contact between CO2 and sensitive chemical bonds through steric hindrance effect, delaying the structural degradation caused by hydrolysis reaction. Secondly, by constructing gradient or multi-layer composite electrolyte system, such as combining alkaline hydrogel with solid electrolyte or polymer membrane, a physical barrier can be formed to inhibit the penetration of CO2, and at the same time, the overall ionic conductivity can be maintained by using the synergistic effect between interfaces (such as charge shielding or ion migration coupling). In addition, the functionalized modification strategy includes the introduction of pH responsive groups (such as zwitterionic groups or smart polymer chains), so that the hydrogel can adjust the swelling behavior through conformational changes when the pH decreases, and maintain the connectivity of ion channels; Or by introducing inorganic nanofillers such as graphene oxide and metal organic frameworks (MOFs) to enhance mechanical strength and physically block CO2 diffusion. Ultimately, by constructing a self-healing network through dynamic chemical bonds such as reversible ester bonds and hydrazone bonds, material integrity can be restored after local structural damage caused by CO2, thereby achieving long-term improvement in CO2 resistance. These strategies optimize the CO2 resistance of hydrogels from molecular scale to macro structure through chemical physical synergy.

Through the previous discussion and review of related studies, it can be concluded that polymer gel electrolytes can indeed solve the problems existing in aqueous zinc-air batteries (such as electrolyte leakage, electrode dendrites, etc.), but there are still some challenges that still need to be overcome. As mentioned above, in the future energy storage market, especially in the field of flexible smart wearable devices, energy storage devices not only need to have good mechanical and electrochemical properties, but also need reliability, stability and flexible environmental adaptability. Notwithstanding substantial advances in polymeric electrolytes, quasi-solid-state aqueous zinc-air batteries utilizing hydrogel polymer electrolytes continue to confront persistent performance bottlenecks requiring resolution.

Primary challenges persist in three critical domains:

(1) Ionic transport limitations