Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Bagasse Fibers Surface Heat Treatment and Its Effect on Mechanical Properties of Starch/Poly (Vinyl Alcohol) Composites

1 School of Chemical Engineering and Materials Science, Zhongkai University of Agriculture and Engineering, Guangzhou, 510225, China

2 Department of Research and Development, Guangzhou Juzhidao New Material Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, 510700, China

3 Department of Research and Development, Guangzhou Solid State Runji New Energy Technology Co., Ltd., Guangzhou, 510700, China

* Corresponding Author: Min Xiao. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Polymer Materials: Multifunctional Design and Sustainable Applications)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 795-810. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.068200

Received 23 May 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Sugarcane bagasse (SCB) is a promising natural fiber for bio-based composites, but its high moisture absorption and poor interfacial adhesion with polymer matrices limit mechanical performance. While chemical treatments have been extensively explored, limited research has addressed how thermal treatment alone alters the surface properties and reinforcing behavior of SCB fibers. This study aims to fill that gap by investigating the effects of heat treatment on SCB fiber structure and its performance in starch/poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) composites. Characterization techniques including Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray diffraction (XRD), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) were employed to analyze changes in fiber morphology, surface chemistry, and crystallinity. Mechanical properties were assessed via tensile, flexural, and impact testing, and moisture absorption was also evaluated. Composites reinforced with SCB fibers treated at 200°C exhibited significantly superior mechanical properties compared to those prepared with untreated or differently treated fibers. The tensile, flexural, and impact performance of the composites were 15.13, 19.37 MPa, and 7.28 J/m, respectively. Composites treated at this temperature also retained better mechanical properties after exposure to humidity. These findings demonstrate that heat treatment is a simple and sustainable method to improve the durability and mechanical performance of nature fiber-reinforced composites, expanding their potential for environmentally friendly material applications.Keywords

The natural biodegradability and chemical composition of sugarcane bagasse (SCB) have attracted increasing attention as a promising and versatile component in composite materials [1]. SCB primarily consists of cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, ash, and wax [2]. This composition offers several advantages over synthetic materials, including low cost, natural origin, sustainability, and biodegradability. These characteristics make SCB an ideal candidate for use as a reinforcing fiber in composites designed to exhibit distinct physical and chemical properties [3].

However, the hydrophilic nature of natural fibers poses a challenge in achieving proper dispersion and adhesion with hydrophobic polymer matrices [4]. This incompatibility often results in poor interfacial bonding, which significantly weakens the mechanical performance of natural fiber-reinforced composites. To overcome this limitation, surface modifications–both physical and chemical—have been widely explored. These methods include grafting of compatibilizer groups via ultrasonic techniques, application of coupling agents, cleaning fiber surfaces [5–7], and heat treatment [8] such as steam explosion [9], Chemical treatments, in particular, can activate hydroxyl group in cellulose and lignin or introduce new functional moieties that enhance fiber-matrix interaction [10]. These approaches support the potential of using SCB as a reliable source of cellulose fibers for composite reinforcement [11–13].

The primary aim of these surface modifications is to alter the reactivity of SCB fibers by adjusting the quantity and location of functional groups, while also minimizing fiber degradation. Chemical treatments have been shown to improve fiber wettability, interfacial adhesion, and porosity—factors that collectively enhance the mechanical properties of the composite [14]. A review of the literature reveals wide variability in treatment methods with respect to chemicals used [15], temperatures [16], pressures [17], and reaction durations [18]. Many of these techniques rely on high energy input or harsh chemicals, limiting their sustainability and scalability. For example, Ribeiro et al. [19] treated sugarcane fiber (SCF) using steam explosion, a thermomechanical process involving high pressure and temperature (typically around 180°C), followed by sudden decompression to break down fiber structure. This method significantly improves fiber-polymer interactions but demands substantial energy. Wulandari et al. [20] used sulfuric acid hydrolysis to process bagasse cellulose. When the sulfuric acid concentration reached 50%, nanocellulose with small particle size was produced at 40°C for 10 min. However, this method involves highly corrosive reagents, a more complex reaction process, and generates numerous by-products and harmful gases. In another example, Pan et al. [21] employed a homogeneous grafting method initiated by ammonium persulfate in aqueous or organic solvent systems. This approach involves the use of volatile organic solvents and generates difficult separation processes between fiber and solvent. Therefore, developing an efficient and environmentally friendly method that operates under mild conditions while providing comparable improvement is highly desirable [22].

Compared to the aforementioned methods, heat treatment emerges as a promising green technique for fiber surface modification due to its low cost, non-corrosive nature, and absence of chemical reagents [23,24]. Typically conducted at temperatures ranging from 120°C to 250°C for durations of 10 min to several hours, heat treatment induces chemical changes in the fiber, including degradation of hemicellulose and partial removal of surface hydroxyl groups. These modifications reduce hydrophilicity and lower surface free energy, thereby enhancing compatibility with hydrophobic polymer matrices [24,25]. In this study, heat treatment was applied to modify SCB, improving interfacial compatibility with the starch matrix and enhancing the composite’s mechanical properties. Compared with solvent-based grafting approaches reported in previous studies [15], this method demonstrates greater efficiency in terms of time, labor, and the elimination of solvent recovery steps, making it more suitable for scalable and sustainable composite fabrication.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR), X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was employed to characterize the surface properties of bagasse fibers before and after heat treatment. The impact of heat treatment temperature was briefly discussed, while the effects of heat treatment on the surface chemistry and morphology of the fibers were analyzed in detail. The results indicated that heat treatment significantly enhanced the interfacial bonding between the fibers and the starch matrix. Overall, this work offers valuable insights into the use of heat-treated fibers to improve the properties of composites.

The SCB utilized in this study was sourced from the Guangdong Bioengineering Institute and was found to contain 51.83% cellulose, 18.39% hemicellulose, and 29.78% lignin (Fig. S1). Freshly collected bagasse was thoroughly washed with running water to eliminate residual sugars, then air-dried under sunlight. Once dried, the bagasse was ground into fine particles using a Wiley mill. The resulting powder was sieved through British Standard (BS) mesh screens, collecting particles that passed through a BS 40 mesh (420 μm) but were retained on a BS 100 mesh (250 μm).

The purified bagasse fibers were subjected to heat treatment in an electric drying oven at temperatures of 180°C, 200°C, and 220°C for 10 min. After treatment, the samples were sealed in plastic bags and stored under ambient conditions until further analysis.

Industrial-grade cornstarch, with an apparent amylose content of 24.05% and a calculated amylopectin content of 75.95%, was purchased from Yin Xin Starch Ltd. (China). Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) was acquired from Xiang Wei Chemical Ltd. (China) and was 99% hydrolyzed, with an average molecular weight of 89,000–98,000 g/mol. Reagent-grade glycerin was provided by Aldrich Chemical Company Inc. All PVA/starch blend solutions were prepared using redistilled, deionized water.

A weighed sample of ground SCB (20 g) was placed in a baking oven and heat treated for 10 min at 180°C, 200°C, and 220°C, respectively. The thermal degradation behavior of SCB at these temperatures is illustrated in Fig. 1. Heat treatment at the lower temperature of 180°C primarily removed free water and some volatile compounds such as extractives, waxes, and oils from the fiber surfaces. At 200°C, the deacetylation of hemicellulose and oxidative degradation of the fibers led to an increase of hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. In this stage, degradation products of hemicellulose may react with lignin to form new chemical structures, and the relative lignin content appears to increase due to the progressive decomposition of hemicellulose. Additionally, some hydroxyl groups on the fiber’s surfaces were replaced by aldehyde or ketone groups. When the temperature reached 220°C, more extensive degradation reactions occurred, involving hemicellulose, lignin, and even cellulose, accompanied by the release of volatile degradation products [26].

Figure 1: Scheme for thermal degradation of SCB

2.3 Preparation of Polymer Composites

Polymer composites were prepared by compounding starch and PVA at a mass ratio of 40:60 [27], reinforced with SCB fibers—either untreated or heat-treated SCB. SCB was incorporated at a concentration of 10 wt.% and mechanically blended with the starch/PVA matrix and glycerin using an intensive mixer at 60°C. The resulting mixture was then processed through a single-screw extruder equipped with four temperature zones, set at 110°C, 115°C, 120°C, and 125°C, respectively, to ensure proper temperature control during extrusion [28].

2.4 Characterization and Testing of SBR/GPN Nanocomposites

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was employed to characterize both raw and heat-treated fibers by analyzing the transmitted infrared radiation across a range of wavelengths. The measurements were conducted using a MAGNA-IR760 spectrometer (Thermo Nicolet Corporation, USA). Powdered fiber samples were thoroughly blended with potassium bromide (KBr) at a mass ratio of 1:99 (sample: KBr) to create pellets. The FTIR spectra were recorded in the range of 4000–400 cm−1 with a resolution of 4 cm−1 and an average of 32 scans per sample [29].

The crystallinity of raw and heat-treated fibers (in powder form) was evaluated using X-ray diffraction (XRD). Diffraction patterns were acquired with a D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer (Bruker Germany) under the following conditions: Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.1548 nm), operated at 40 kV and 40 mA. A step size of 0.02° and a scan time of 0.1 s per step were applied over a 2θ range of 4°–60°. The degree of crystallinity was quantified using the crystallinity index (CI), calculated by Eq. (1), where I 0 0 2 is the maximum peak intensity at a 2θ angle around 22°, corresponding to the crystalline region, and I 1 0 1 is the minimum intensity at approximately 18°, representing the amorphous region [30,31].

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) spectra were recorded using an AXIS 165 electron spectrometer (Kratos Analytical) with a take-off angle of 90° and monochromatic Al Ka irradiation. Spectra were collected from at least three different locations on each sample, utilizing an analysis area of 1 mm × 1 mm. High-resolution spectra were acquired in 0.1 eV steps with a pass energy 20 eV. The base pressure during analysis was typically 1 × 10−9 Torr, and it was maintained below 5 × 10−9 Torr during measurements [29].

Surface elemental compositions and O/C ratios were determined from the survey spectra. The relative amounts of carbon atoms bonded to different numbers of oxygen atoms were analyzed from the high-resolution carbon C1s spectra by deconvolution into four symmetric Gaussian components [32]. During peak fitting, both the relative peak positions and widths were fixed. The chemical shifts relative to C-C (C1) peak were as follows: C-O (C2) at 1.7 ± 0.1 eV, O-C-O or C=O (C3) at 3.1 ± 0.1 eV, and O-C=O (C4) 4.4 ± 0.2 eV. The C-C component at 285.0 eV was used as the reference for the binding energy scale [33].

The mechanical testing was carried out in accordance with ASTM D3039, ASTM D790 and ASTM D256. The gauge length is 48 mm, and the stretching speed is 50 mm/min. For each test, five specimens were evaluated to determine the average value [34].

2.4.5 Scanning Electron Microscopy

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed using a Quanta 200 microscope (FEI, USA) operated at an accelerating voltage of 5–15 kV. This technique was employed to investigate the surface morphologies of SCB residues subjected to various heat treatment conditions, as well as the fracture topographies of composite samples following tensile testing. Prior to imaging, all samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold to enhance conductivity [35].

3.1 Surface Characterization (Groups) of Bagasse Fibers

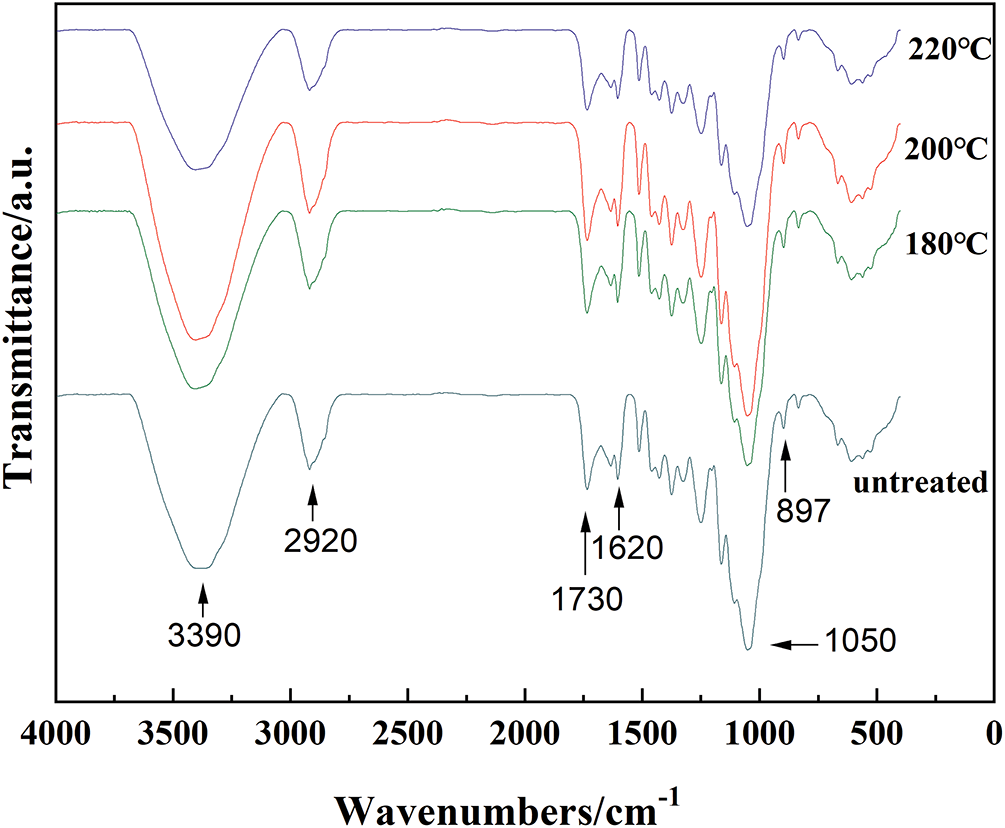

Infrared spectroscopy has proven to be a powerful technique for characterizing cellulose and other lignocellulosic composites. As shown in Fig. 2, the FTIR spectra of heat-treated fibers showed significant changes in the broad bands related to O-H stretching vibrations around 3390 cm−1 and the C-O stretching vibrations region near 1050 cm−1, as well as in the aliphatic saturated C-H stretching vibration at approximately 2900 cm−1, which is characteristic of the lignin/polysaccharide complex. The appearance of a C=O stretching band around 1620 cm−1 is attributed to carbonyl groups. A peak at approximately at 1730 cm−1 corresponds to COO− groups, which may arise from the acetyl and uronic ester groups in hemicelluloses, or from ester linkages involving carboxylic group in ferulic and p-coumaric acids present in lignin and/or hemicelluloses [36,37].

Figure 2: FTIR spectra of SCB before and after heat treatment at different temperatures

It is well established that heat treatment eliminates free water, extractives, waxes, oil, and other volatile components from the fiber surface. Depending on the treatment temperature, it can also induce oxidative degradation of cellulose, lignin, and hemicellulose. These thermal-induced transformation are clearly reflected in the FTIR spectra. Specifically, after heat treatment at 180°C, a significant reduction in the absorption intensity of bands around 3390, 1620, and 1730 cm−1 was observed, indicating the loss of hydroxyl and carbonyl-containing groups.

As the temperature increased to 200°C, the intensities of these absorption bands also rose, likely due to the partial degradation of hemicellulose and subsequent oxidation of fiber components, which generates additional hydroxyl and carbonyl groups. Furthermore, degradation products of hemicellulose may react with lignin to form new chemical structures, thereby enhancing lignin-related peaks. However, at 220°C, further degradation of hemicellulose, lignin, or even cellulose resulted in the formation and release of volatile degradation products, leading to a subsequent decrease in absorption intensity. This interpretation is supported by compositional data shown in Fig. S1 and is further corroborated by XPS analysis, as discussed in the following section.

The chemical composition of the fiber surfaces was analyzed using XPS. XPS has proven to be an effective technique for investigating the chemical structure and elemental composition of various polysaccharide-based materials [38]. Due to its extremely shallow probing depth, typically less than 10 nm, XPS is particularly well-suited for characterizing the outermost molecular layer of fiber surfaces with high sensitivity [29].

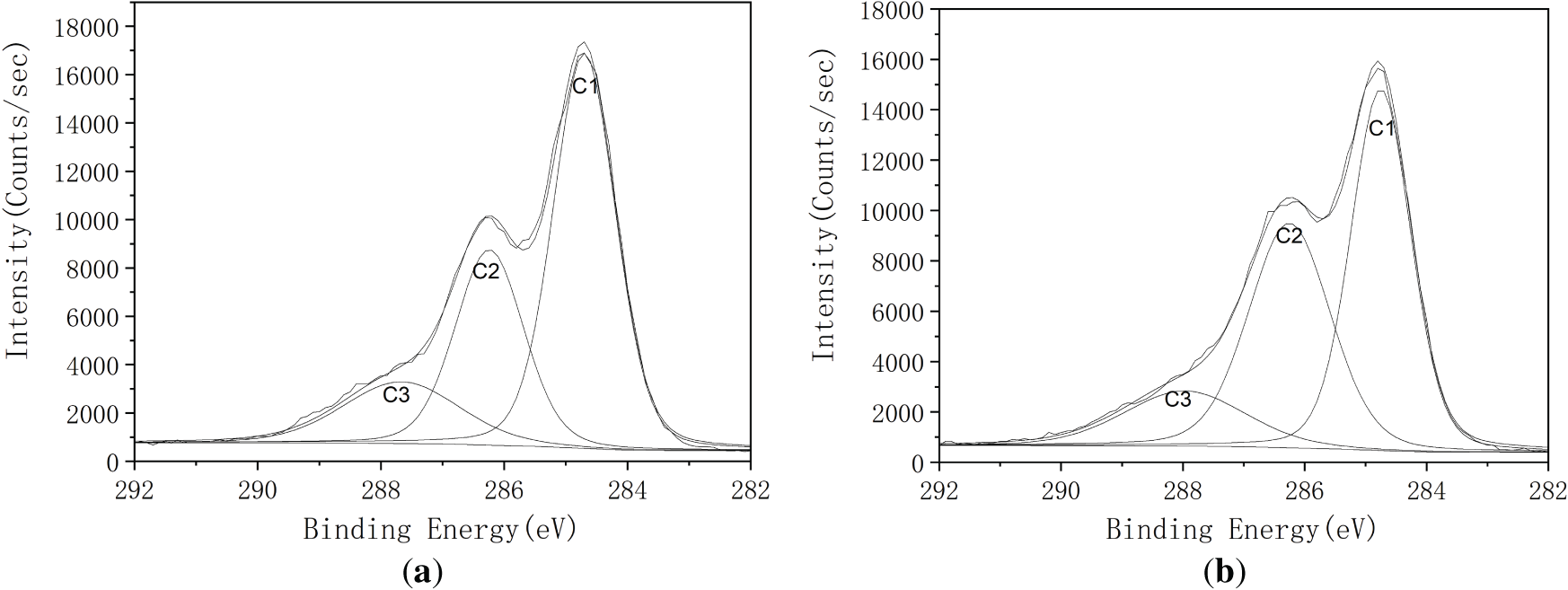

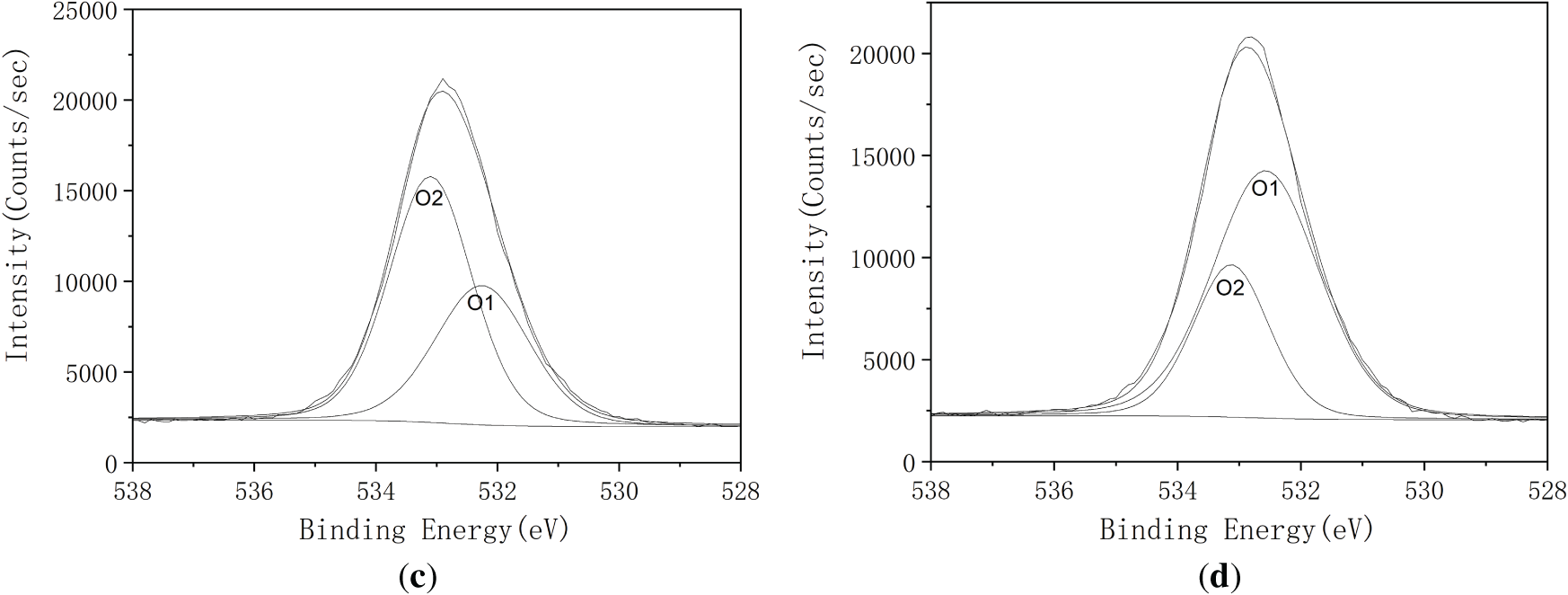

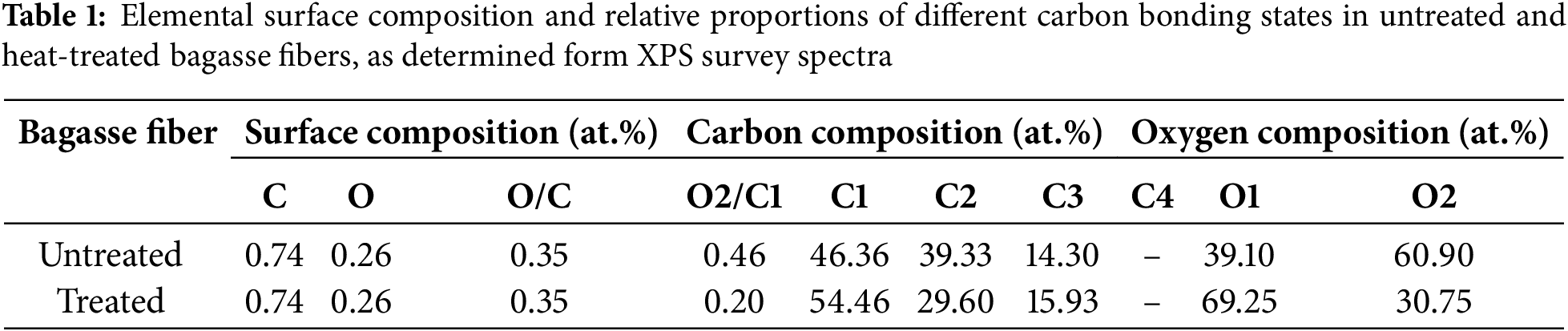

Fig. 3 illustrates the high resolution C1s and O1s spectra for both untreated and heat-treated fibers samples. The elemental surface composition and the relative proportions of various carbon bonding environments, based on the high-resolution C1s and O1s peaks, are detailed in Table 1. According to established literature [32], the chemical shifts of the C1s spectrum in XPS are typically categorized into four types: C1, non-oxidized carbon (C–C); C2, carbon bonded to a single oxygen atom (C–O); C3, carbon bonded to two oxygen atoms (O–C–O or C=O); and C4, carbon bonded to three oxygen atoms (O–C=O). These peaks were observed at approximately at 284.7 eV (C1), 286.2 eV (C2), 287.9 eV (C3 and C4) eV, respectively. Similarly, the O1s can be classified into two types: O1, oxygen double-bonded to carbon (O=C), and O2, oxygen single-bonded to carbon (O–C) with peaks appearing at approximately 532.2 and 533.1 eV, respectively [39].

Figure 3: High-resolution XPS spectra of SCB before and after heat treatment: (a) C 1s spectrum of untreated fiber; (b) C 1s spectrum of fiber treated at 200°C; (c) O 1s spectrum of untreated fiber; (d) O 1s spectrum of fiber treated at 200°C

Both untreated and heat-treated samples displayed the presence of C1 and O1 components. However, thermal treatment induced notable changes in the fiber surface, as shown in the high-resolution C1s spectra (Table 1). Specifically, a significant decrease in C2-type carbon (C–O), characteristic of cellulose and hemicellulose (C2), was observed. This reduction was accompanied by an increase in the C1 and C3 carbon components. Since cellulose inherently contains minimal C1-type carbon due to its polysaccharide backbone [40], the post-treatment increase in C1 indicates partial degradation of cellulose and hemicellulose. The reduction in C2 content further supports this inference, suggesting the thermal decomposition of hemicellulose and possibly cellulose, thereby contributing to a corresponding increase in C3 species.

In the O1s spectra, the O2/C1 ratio increased significantly, despite a nearly unchanged overall O/C ratio. This shift indicates either the formation of new oxygen-containing groups at former C2 sites or increased surface exposure of lignin components [41]. During heat treatment, the oxidation of hemicellulose or cellulose likely decreases the hydroxy group content at C2 sites, resulting in the formation of aldehyde and ketone groups within the fiber matrix. These findings are consistent with previous FTIR results of SCB and XPS analyses of chemically treated fibers [42], indicating that thermal modification alone can produce comparable surface chemical changes. Collectively, the results highlight the potential of heat-treated SCB fibers as functional cellulose-based reinforcements in composite applications.

Heat treatment induces notable changes in the morphology and chemical composition of SCB cellulose fibers. It effectively removes hemicelluloses, waxes and other surface impurities, resulting in a chemically uniform fiber surface. Additionally, the heat treatment leads to increased surface roughness, which can enhance interfacial adhesion between the fibers and the polymer matrix [43–45].

As shown in Fig. 4a, the untreated fibers exhibit a smooth surface with visible impurities, which adversely affect fiber–matrix adhesion and diminish the overall mechanical properties of the composite. In contrast, Fig. 4b illustrates fibers treated at 200°C, revealing smoother surfaces and a porous, disrupted cellular structure. This breakdown of the cell wall reduces the void content and enhances the effective surface area for interaction with the matrix, potentially improving the mechanical performance of the composite. However, excessive heat can be detrimental. Fig. 4c depicts fibers treated at 220°C, which show significant damage and peeling of the fiber surface. These structural degradations weaken the fibers, resulting in reduced reinforcement efficiency and compromised interior composite properties.

Figure 4: SEM images of untreated and heat-treated fibers: (a) untreated fibers; (b) fibers heat-treated at 200°C; (c) fibers heat-treated at 220°C

The fractured surfaces of the composites following tensile testing are depicted in Fig. 5. These images reveal significant fiber–matrix interfacial adhesion. Notably, Fig. 5c demonstrates that the fibers are thoroughly embedded within the starch/PVA, with no distinct fiber outlines visible. This indicates that the fibers were well bonded to the matrix, making them difficult to differentiate from the surrounding thermoplastic material. While it is challenging to draw definitive conclusions about the fracture behavior of the fibers based solely on the SEM images, there is clear evidence of pull-out in Fig. 5c. This observation suggests that interfacial bonding was strong enough to withstand fiber debonding up to a critical point, after which mechanical separation occurred during fracture.

Figure 5: SEM images of untreated and heat-treated composites: (a) untreated fibers; (b) fibers heat-treated at 180°C; (c) fibers heat-treated at 200°C; (d) fibers heat-treated at 220°C

3.3 Crystalline Structure of Bagasse Fibers

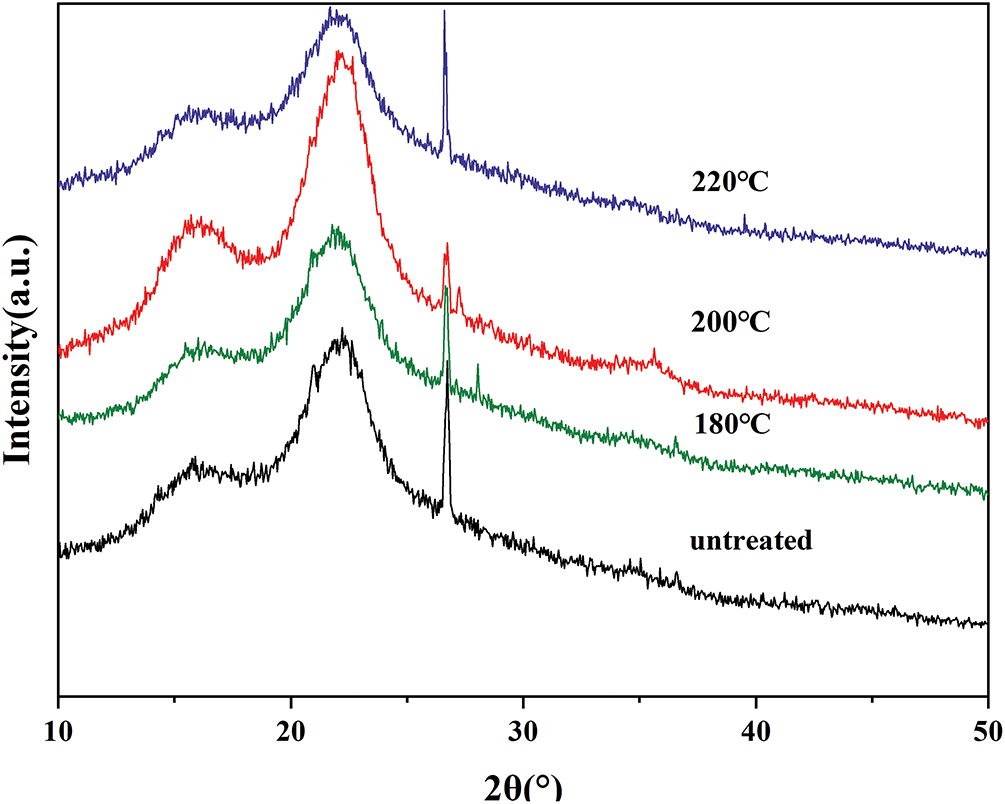

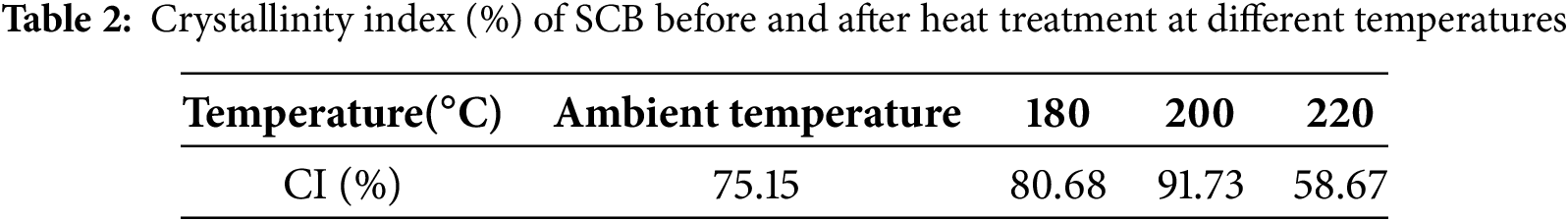

The primary components of SCB fibers, whether treated or untreated, exist in both crystalline and amorphous forms, as shown by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis. The XRD patterns obtained for all samples are displayed in Fig. 6. Two distinct diffraction peaks are observed near 2θ ≈ 18° and 2θ ≈ 22°, corresponding to the cellulose crystallographic planes (101) and (102), respectively, which are associated with crystalline regions. Additionally, a broad diffuse background signal, indicative of amorphous regions, was also detected in the diffractograms [46]. The crystallinity index (CI) was calculated using Eq. (1), and the results are summarized in Table 2.

Figure 6: X-ray diffractogram of SCB before and after heat-treated at different temperatures

All samples displayed similar diffraction patterns to those of untreated SCB fibers; however, significant differences were observed in CI values, indicating that heat treatment influences the crystallinity of bagasse fibers. Notably, fibers treated at 200°C exhibited the highest crystallinity among all treated samples. A comparison of diffractograms before and after heat treatment (below 200°C) shows an increase in crystallinity, while the peak positions remained largely unchanged. This increase can be attributed to the thermal degradation of hemicellulose and the partial removal of amorphous components such as extractives, waxes, and oils, which enhances the relative proportion of crystalline cellulose.

In contrast, samples treated at temperatures exceeding 200°C exhibited a decline in CI. This decrease is likely due to structural damage, including the loss of bound water or even partial breakdown of crystalline domains, which reduces the regularity of the cellulose structure. Overall, heat treatment significantly influences the crystalline structure of SCB fibers, with a CI increase of up to 16% at moderate temperatures, followed by a decline of approximately 16% at higher temperatures.

For comparison, previous studies have reported a reduction in crystallinity when SCB is chemically modified using methyl methacrylate (MMA) grafting [47], as the introduction of MMA disrupts intermolecular hydrogen bonding within the SCB-g-MMA structure. This disruption leads to a decrease in crystallinity and tensile strength. In contrast, heat-treated SCB fibers maintain or enhance their crystalline integrity and are therefore expected to exhibit improved mechanical properties when incorporated into a starch-based composite matrix.

3.4 Mechanical Properties of Composites

The most critical factor in achieving a high-performance fiber- reinforced composite is the interfacial adhesion between the matrix and the fiber. However, the inherently inert and hydrophilic nature of SCB cellulose fibers results in poor wettability with hydrophobic polymer matrices, leading to weak interfacial bonding. To improve the mechanical properties of such composites, surface modification of the fibers is essential. Among various approaches, heat treatment effectively induces oxidative reactions on the fiber surface, introducing functional groups that enhance chemical reactivity and alter surface crystallinity by partially relaxing the native cellulose structure.

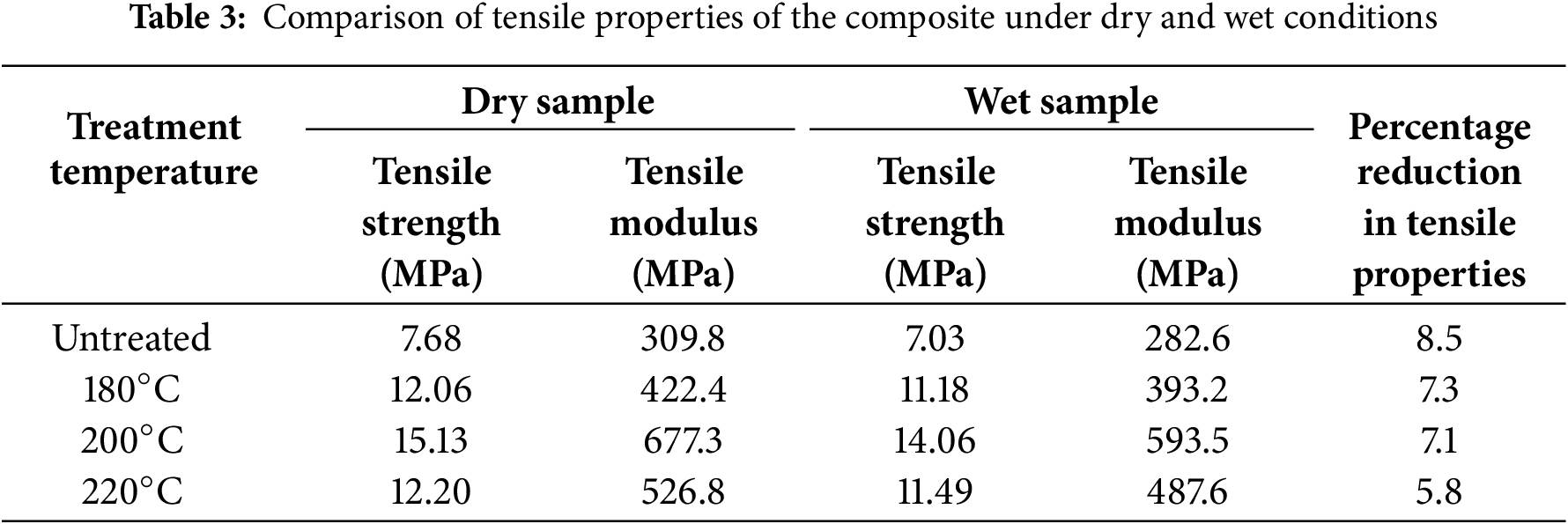

The effect of heat treatment temperature on the mechanical properties of starch/PVA fiber composites was assessed according to ASTM standards. Tensile properties are illustrated in Fig. 7a. Composites incorporating fibers treated at 200°C demonstrated the highest tensile strength and modulus, reaching 15.13 and 677.3 MPa, respectively—an enhancement of 97% compared to the untreated fiber composite. This improvement is attributed to stronger interfacial adhesion resulting from the formation of surface-active groups and increased crystallinity. However, further increases in treatment temperature led to a decline in tensile properties, likely due to thermal degradation of the fiber surface. These findings indicate that 200°C is the optimal treatment temperature for maximizing interfacial bonding.

Figure 7: Effect of different heat treatment temperatures on the mechanical property: (a) Tensile properties of the composite; (b) Flexural properties of the composite; (c) Impact properties of the composite

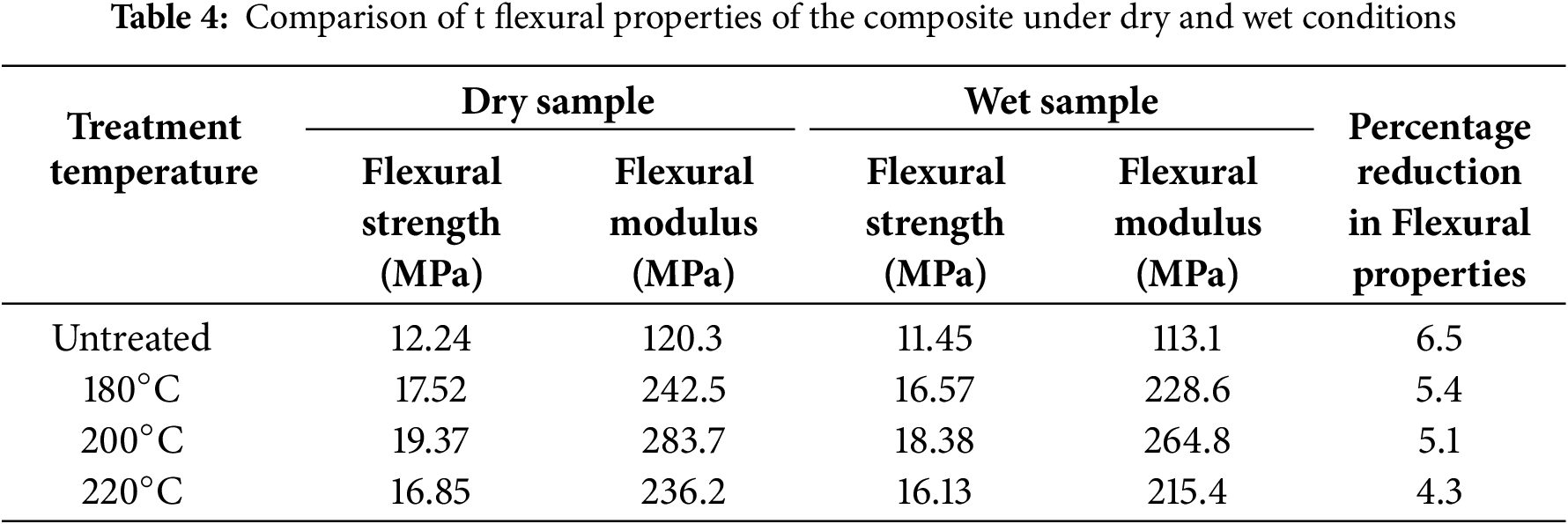

Flexural properties, measured through a three-point bending test, are shown in Fig. 7b. The composite reinforced with 200°C-treated fibers exhibited the highest flexural strength (19.37 MPa) and modulus (283.7 MPa), reflecting a 36.81% increase over the untreated sample. Above this temperature, flexural performance decreased, further supporting the notion that excessive thermal exposure damages the fiber surface and weakens interfacial bonding.

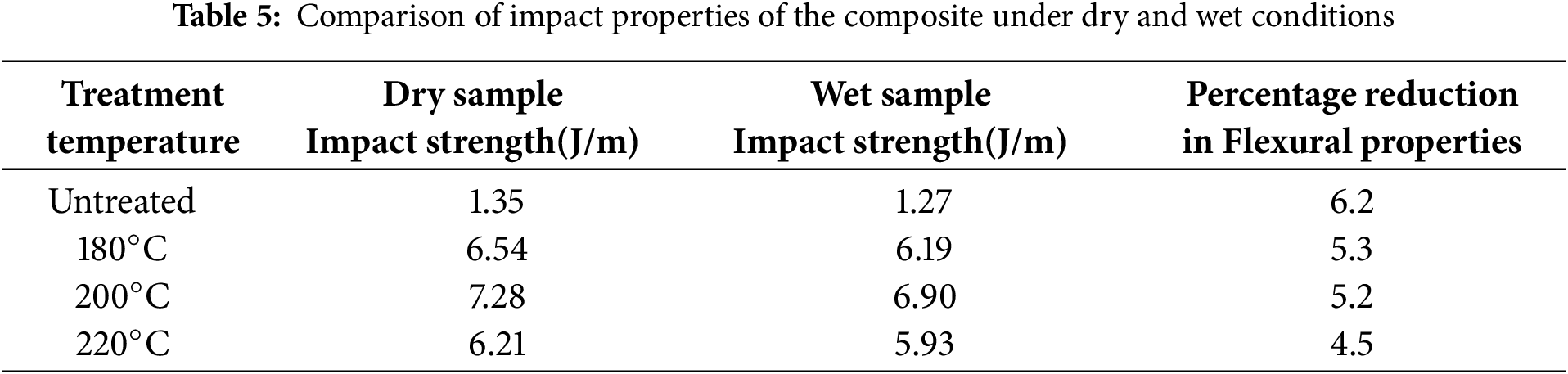

Impact strength, defined as a material’s ability to absorb energy during sudden loading, was also evaluated (Fig. 7c). The composite treated at 200°C exhibited the highest impact strength at 7.28 J/m—an 81.46% increase compared to the untreated composite. This enhancement is attributed to more effective stress distribution resulting from better fiber-matrix interfacial adhesion. As with the other mechanical properties, elevated treatment temperatures adversely impacted the impact strength, likely due to thermal degradation and embrittlement of the fiber surface.

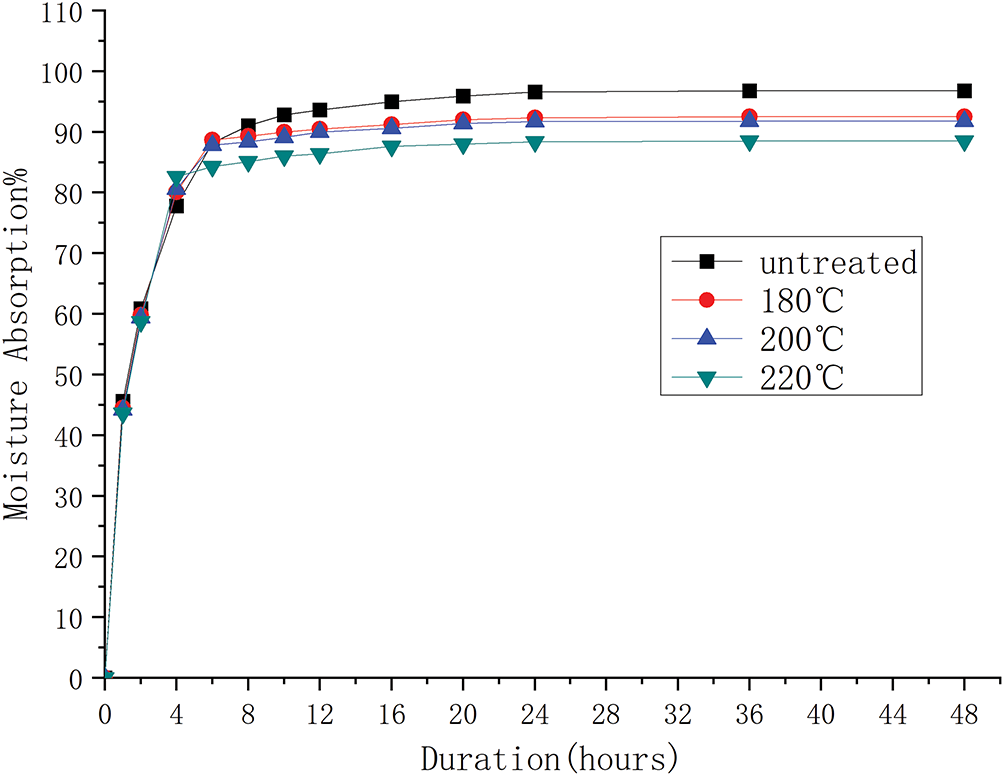

3.5 Resistance to Humidity of Composites

Moisture absorption is one of the most undesirable characteristics of natural fibers, as it compromises the interfacial adhesion between the fiber and the matrix. The effect of heat treatment on the water absorption behavior of bagasse fiber composite was investigated by monitoring moisture uptake over time and the results are presented in Fig. 8 The untreated composite exhibited a maximum moisture absorption of 96.8%, while the heat-treated composite showed a reduced uptake of 88.5%, representing an 8.6% decrease compared to the untreated sample. As illustrated in Fig. 8, increasing the heat treatment temperature further decreases the moisture absorption rate. This reduction is attributed either to the decreased surface hydroxyl content (which reduces fiber polarity) or to improved interfacial adhesion that restricts water penetration. Regardless of the treatment temperature, all composites reached saturation after 24 h of immersion.

Figure 8: Moisture absorption behavior of untreated and heat-treated composites

To evaluate the effect of moisture on mechanical properties, tensile, flexural, and impact test samples were conditioned at 60% relative humidity for 30 days. The tensile properties before and after moisture exposure are tabulated in Table 3. Moisture exposure significantly affects the mechanical performance of the composite. Among all samples, the 220°C heat-treated composite showed the smallest reduction in the tensile strength, with only a 5.8% decrease—31.8% less than that of the untreated sample. Similar trends were observed in the flexural test results (Table 4), where the 220°C treated composites again exhibited the lowest reduction in flexural strength and modulus, recorded at 16.13 and 215.4 MPa, respectively—representing a 21.5% lower decrease compared to untreated composites.

Impact strength results (Table 5) further validate this trend. The 220°C treated composites exhibited the smallest decline in impact strength, with a reduction of 4.5 J/m–27.42% less than the untreated sample. These findings suggest that moisture diminishes mechanical properties primarily by weakening fiber–matrix adhesion. The swelling of hydrophilic fibers upon moisture uptake disrupts the interfacial region, impeding stress transfer and thereby reducing mechanical efficiency. Heat treatment alleviates this effect by decreasing the fibers’ moisture affinity, which in turn helps maintain mechanical integrity after moisture exposure. Overall, higher heat treatment temperatures yield greater resistance to moisture-induced degradation of mechanical properties.

From this study, it is evident that heat treatment significantly influences the surface characteristics of SCB fibers and enhances the mechanical properties of SCB/starch/PVA composites. It facilitates the removal of low molecular weight non-cellulosic compounds and promotes the formation of new hydroxyl and carbonyl groups on the cellulose surfaces, thereby increasing the fiber’s chemical reactivity. Among the various treatment temperatures examined, 200°C was found to yield the most favorable mechanical properties. Higher temperatures caused damage to the fiber surface, which negatively impacting the tensile properties of the composite, as confirmed by scanning electron microscopy. The composite treated at 200°C exhibited a 97% improvement in tensile properties compared to the untreated counterpart. Overall, this study demonstrates that heat treatment is a straightforward, cost-effective, and efficient method for enhancing both the mechanical properties and moisture resistance of SCB-based composites, providing a promising alternative to more complex physical and chemical techniques.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: Xiangyang Zhou; Data collection: Yashi Wang, Jiajun Liu, Jiahao Wen, Haodong Shen and Hucan Hong; Analysis and interpretation of results: Yashi Wang and Min Xiao; Draft manuscript preparation: Xiangyang Zhou, Yashi Wang and Min Xiao. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Kusuma HS, Permatasari D, Umar WK, Sharma SK. Sugarcane bagasse as an environmentally friendly composite material to face the sustainable development era. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2024;14(21):26693–706. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-03764-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Madhu S, Devarajan Y, Natrayan L. Effective utilization of waste sugarcane bagasse filler-reinforced glass fibre epoxy composites on its mechanical properties—waste to sustainable production. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2023;13(16):15111–8. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-03792-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Devadiga DG, Bhat KS, Mahesha G. Sugarcane bagasse fiber reinforced composites: recent advances and applications. Cogent Eng. 2020;7(1):1823159. doi:10.1080/23311916.2020.1823159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ferreira DP, Cruz J, Fangueiro R. Chapter 1—surface modification of natural fibers in polymer composites, Green composites for automotive applications. In: Koronis G, Silva A, editors. Green composites for automotive applications. Cambridge, UK: Woodhead Publishing; 2019. p. 3–41. doi:10.1016/b978-0-08-102177-4.00001-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Chaber P, Andrä-Żmuda S, Śmigiel-Gac N, Zięba M, Dawid K, Martinka Maksymiak M, et al. Enhancing the potential of PHAs in tissue engineering applications: a review of chemical modification methods. Materials. 2024;17(23):5829. doi:10.3390/ma17235829. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Han D, Hong Q. Emerging trends in cellulose and lignin-based nanomaterials for water treatment. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;307(Pt 3):141936. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.141936. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Rahman MM, Islam MM, Maniruzzaman M. Preparation and characterization of biocomposite from modified α-cellulose of Agave cantala leaf fiber by graft copolymerization with 2-hydroxy ethyl methacrylate. Carbohydr Polym Technol Appl. 2023;6(28):100354. doi:10.1016/j.carpta.2023.100354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Syduzzaman M, Hassan A, Anik HR, Tania IS, Ferdous T, Fahmi FF. Unveiling new frontiers: bast fiber-reinforced polymer composites and their mechanical properties. Polym Compos. 2023;44(11):7317–49. doi:10.1002/pc.27661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Souza Rosa CHS, Gonçalves Mothé M, Vieira Marques MF, Gonçalves Mothé C, Neves Monteiro S. Steam-exploded fibers of almond tree leaves as reinforcement of novel recycled polypropylene composites. J Mater Res Technol. 2020;9(5):11791–800. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.08.069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Mulinari DR, de Paula Cipriano J, Capri MR, Brandão AT. Influence of surgarcane bagasse fibers with modified surface on polypropylene composites. J Nat Fibers. 2018;15(2):174–82. doi:10.1080/15440478.2016.1266294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Joseph J, Munda PR, Kumar M, Sidpara AM, Paul J. Sustainable conducting polymer composites: study of mechanical and tribological properties of natural fiber reinforced PVA composites with carbon nanofillers. Polymer-Plastics Technol Mater. 2020;59(10):1088–99. doi:10.1080/25740881.2020.1719144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Mahmud S, Faridul Hasan KM, Jahid MA, Mohiuddin K, Zhang R, Zhu J. Comprehensive review on plant fiber-reinforced polymeric biocomposites. J Mater Sci. 2021;56(12):7231–64. doi:10.1007/s10853-021-05774-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shukla N, Agrawal H, Srivastava I, Khan A, Devnani GL. Natural composites: vegetable fiber modification. In: Vegetable fiber composites and their technological applications. Singapore: Springer; 2021. p. 303–25. doi:10.1007/978-981-16-1854-3_13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Bhatia JK, Kaith BS, Kalia S. Recent developments in surface modification of natural fibers for their use in biocomposites. In: Biodegradable green composites. Hoboken, NJ, USA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2016. p. 80–117. [Google Scholar]

15. Mohit H, Selvan VAM. Effect of a novel chemical treatment on the physico-thermal properties of sugarcane nanocellulose fiber reinforced epoxy nanocomposites. Int Polym Process. 2020;35(2):211–20. doi:10.3139/217.3855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Kramar AD, Obradović BM, Schiehser S, Potthast A, Kuraica MM, Kostić MM. Enhanced antimicrobial activity of atmospheric pressure plasma treated and aged cotton fibers. J Nat Fibers. 2022;19(14):7391–405. doi:10.1080/15440478.2021.1946883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Phiri R, Rangappa SM, Andoko A, Gapsari F, Siengchin S. Modification of cellulose in sugarcane bagasse fibers towards development of biocomposite. Biomass Conv Bioref. 2025;15(11):17679–95. doi:10.1007/s13399-024-06353-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Phiri R, Rangappa SM, Siengchin S. Sugarcane bagasse for sustainable development of thermoset biocomposites. J Polym Res. 2024;31(11):317. doi:10.1007/s10965-024-04168-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ribeiro GL, Gandara M, Moreno DDP, Saron C. Low-density polyethylene/sugarcane fiber composites from recycled polymer and treated fiber by steam explosion. J Nat Fibers. 2019;16(1):13–24. doi:10.1080/15440478.2017.1379044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Wulandari WT, Rochliadi A, Arcana IM. Nanocellulose prepared by acid hydrolysis of isolated cellulose from sugarcane bagasse. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2016;107:012045. doi:10.1088/1757-899x/107/1/012045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Pan YW, Liu Q, Yang SH, Li HF, Liu CF, Deng LN. Preparation and characterization of bagasse cellulose oil absorption material. Mod Chem Ind. 2021;41(7):164–8+73. (In Chinese). doi:10.16606/j.cnki.issn0253-4320.2021.07.034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Zwawi M. A review on natural fiber bio-composites, surface modifications and applications. Molecules. 2021;26(2):404. doi:10.3390/molecules26020404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. AL-Oqla FM, Alaaeddin MH. Chemical modifications of natural fiber surface and their effects. In: Bast fibers and their composites. Singapore: Springer; 2022. p. 39–64. doi:10.1007/978-981-19-4866-4_3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Mundhe A, Kandasubramanian B. Advancements in natural fiber composites: innovative chemical surface treatments, characterizaton techniques, environmental sustainability, and wide-ranging applications. Hybrid Adv. 2024;7:100282. doi:10.1016/j.hybadv.2024.100282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Kalia S, Kaith BS, Kaur I. Pretreatments of natural fibers and their application as reinforcing material in polymer composites—a review. Polym Eng Sci. 2009;49(7):1253–72. doi:10.1002/pen.21328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen C, Zhang Q, Chen J, Zhang S, Zhao C, Scarpa F, et al. Heat treated bamboo fiber bundles. Cellulose. 2025;32(7):4503–24. doi:10.1007/s10570-025-06502-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Phattarateera S, Sangthongdee M, Threepopnatkul P. Properties of blends from pregelatinized starch with poly (vinyl alcohol) for hygienic-purposed disposable laundry bags. J Reinf Plast Compos. 2023;42(23–24):1277–88. doi:10.1177/07316844221150890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu F, Cao Y, Ren J, Xie Y, Xiao X, Zou Y, et al. Optimization of starch foam extrusion through PVA polymerization, moisture content control, and CMCS incorporation for enhanced antibacterial cushioning packaging. Carbohydr Polym. 2025;347(1):122763. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Grams J. Surface analysis of solid products of thermal treatment of lignocellulosic biomass. J Anal Appl Pyrolysis. 2022;161:105429. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2021.105429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rocky BP, Thompson AJ. Characterization of the crystallographic properties of bamboo plants, natural and viscose fibers by X-ray diffraction method. J Text Inst. 2021;112(8):1295–303. doi:10.1080/00405000.2020.1813407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Siti Syazwani N, Ervina Efzan MN, Kok CK, Nurhidayatullaili MJ. Analysis on extracted jute cellulose nanofibers by Fourier transform infrared and X-ray diffraction. J Build Eng. 2022;48(6):103744. doi:10.1016/j.jobe.2021.103744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Gengenbach TR, Major GH, Linford MR, Easton CD. Practical guides for X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPSinterpreting the carbon 1s spectrum. J Vac Sci Technol A. 2021;39(1):013204. doi:10.1116/6.0000682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Major GH, Avval TG, Patel DI, Shah D, Roychowdhury T, Barlow AJ, et al. A discussion of approaches for fitting asymmetric signals in X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPSnoting the importance of Voigt-like peak shapes. Surf Interface Anal. 2021;53(8):689–707. doi:10.1002/sia.6958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Noor Mohamed NH, Takagi H, Nakagaito AN. Mechanical properties of heat-treated cellulose nanofiber-reinforced polyvinyl alcohol nanocomposite. J Compos Mater. 2017;51(14):1971–7. doi:10.1177/0021998316665238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Moramarco A, Ricca E, Acciardo E, Laurenti E, Bracco P. Cellulose extraction from soybean hulls and hemp waste by alkaline and acidic treatments: an in-depth investigation on the effects of the chemical treatments on biomass. Polymers. 2025;17(9). doi:10.3390/polym17091220. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Kostryukov SG, Matyakubov HB, Masterova YY, Kozlov AS, Pryanichnikova MK, Pynenkov AA, et al. Determination of lignin, cellulose, and hemicellulose in plant materials by FTIR spectroscopy. J Anal Chem. 2023;78(6):718–27. doi:10.1134/s1061934823040093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wei R, Li H, Lin Y, Yang L, Long H, Xu CC, et al. Reduction characteristics of iron oxide by the hemicellulose, cellulose, and lignin components of biomass. Energy Fuels. 2020;34(7):8332–9. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c00377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Smith M, Scudiero L, Espinal J, McEwen JS, Garcia-Perez M. Improving the deconvolution and interpretation of XPS spectra from chars by ab initio calculations. Carbon. 2016;110(3):155–71. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2016.09.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Fujimoto A, Yamada Y, Koinuma M, Sato S. Origins of sp3C peaks in C1s X-ray photoelectron spectra of carbon materials. Anal Chem. 2016;88(12):6110–4. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Zhu H, Han Z, Cheng JH, Sun DW. Modification of cellulose from sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) bagasse pulp by cold plasma: dissolution, structure and surface chemistry analysis. Food Chem. 2022;374(1):131675. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2021.131675. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Rahmati S, Atanda L, Deshan ADK, Moghaddam L, Dubal D, Doherty W, et al. A green process for producing xylooligosaccharides via autohydrolysis of plasma-treated sugarcane bagasse. Ind Crops Prod. 2023;198:116690. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.116690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wan Z, Li K. Effect of pre-pyrolysis mode on simultaneous introduction of nitrogen/oxygen-containing functional groups into the structure of bagasse-based mesoporous carbon and its influence on Cu(II) adsorption. Chemosphere. 2018;194:370–80. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.11.181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Azlina Ramlee N, Jawaid M, Abdul Karim Yamani S, Syams Zainudin E, Alamery S. Effect of surface treatment on mechanical, physical and morphological properties of oil palm/bagasse fiber reinforced phenolic hybrid composites for wall thermal insulation application. Constr Build Mater. 2021;276(174):122239. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2020.122239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Laluce C, Roldan IU, Pecoraro E, Igbojionu LI, Ribeiro CA. Effects of pretreatment applied to sugarcane bagasse on composition and morphology of cellulosic fractions. Biomass Bioenergy. 2019;126(2):231–8. doi:10.1016/j.biombioe.2019.03.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zafeer MK, Prabhu R, Rao S, Mahesha G, Bhat KS. Mechanical characteristics of sugarcane bagasse fibre reinforced polymer composites: a review. Cogent Eng. 2023;10(1):2200903. doi:10.1080/23311916.2023.2200903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Foroushani MY, Foroushani AY, Yarahmadi H. Analysis of mechanical techniques in extractingcellulose fibers from sugarcane bagasse. Biomass Convers Biorefinery. 2025;15(12):18601–14. doi:10.1007/s13399-025-06596-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Wang Y, Xu H, Huang L, Han X, Wei Z, Mo Q, et al. Preparation and properties of graft-modified bagasse cellulose/polylactic acid composites. J Nat Fibers. 2023;20(1):2164822. doi:10.1080/15440478.2022.2164822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools