Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Design Principles of Ultrathin Polymer-Based Electrolyte for Lithium-Metal Batteries

1 State Key Laboratory of Organic-Inorganic Composites, Beijing University of Chemical Technology, Beijing, 100029, China

2 State Key Laboratory of Molecular Engineering of Polymers, Department of Macromolecule Science, Fudan University, Shanghai, 200438, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jiayao Chen. Email: ; Peng-Fei Cao. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 571-586. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.068907

Received 10 June 2025; Accepted 07 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

In recent years, ultrathin polymer-based electrolytes (UPEs) have emerged as a promising strategy to enhance the energy density of rechargeable batteries for wearable devices by minimizing electrolyte volume, demonstrating higher ionic conductance and lower internal resistance, and more compact battery stacking compared to conventional thick polymer-based electrolyte. This mini review systematically summarizes recent advances in ultrathin solid-state and gel-state electrolytes, focusing on their preparation strategies, advantages, and disadvantages, where the energy density, interfacial stability, mechanical properties, and ion-transport mechanisms are also analyzed for understanding the UPE application. Moreover, the challenges such as dendrite penetration and instability (thermal, chemical and interface), along with their solutions are also introduced through interfacial engineering, polymer matrix design, and fillers incorporation. Furthermore, for practical application, the demands of working current density, operating temperature and scale-up production are also illustrated. This mini review is hoped to spark insights into improving the energy density of batteries and ultimately bring us a step closer to realizing superior rechargeable batteries.Keywords

The demand for wearable devices has driven significant advancements in flexible energy storage systems, which can accommodate anatomical contours, deliver robust energy output, and ensure operational safety [1–3]. Lithium-metal batteries (LMBs) have emerged as the preeminent solution among energy storage systems, owing to their exceptional advantages in low self-discharge rates, high voltage, absence of memory effects, and high energy density [4,5]. However, the flammable and unstable liquid electrolytes usually give rise to non-uniform solid electrolyte interphase (SEI) and porous Li0 dendrites growth on the surface of the Li anode, which would lead to short circuit and thermal runaway, rendering them unsuitable for integration into the energy storage system of flexible devices [6]. Therefore, to improve the safety performance of the battery, the transition towards solid-state electrolyte (SSE) with high strength and enhanced safety has been identified as a pivotal strategy for next-generation LMBs [7–9].

SSEs can be generally divided into two categories: solid-state ceramic electrolytes (Li-ion conductor, SCE) and solid-state polymer electrolytes (polymer-salt complex, SPE) that are composed of a polymer and lithium salt [10,11]. SPEs stand out for their remarkable flexibility, excellent processability and exceptional compatibility with electrode interfaces, underscoring their potential to address the critical limitations associated with organic liquid electrolytes, such as flammability and interfacial problems [12]. Since initially reported by Wright et al., poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO) with oligoether (-CH2-CH2-O-)n chain has emerged as one of the most promising SPE for wide applications [13]. Significant efforts have subsequently been directed toward developing other SPEs with electron-withdrawing groups dispersed along the carbon chain to achieve ion-pair dissociation and ion conduction, including poly (acrylonitrile) (PAN), poly (methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) and poly (vinyl alcohol) (PVA) [14–16]. The typical SPEs are fabricated by solvating Li salts (such as LiBF4, lithium bis(trifluoromethylsulphonyl)imide (LiTFSI)) in polymer matrix [17], which can act as plasticizers to disrupt the polymer crystalline by forming complexes with Li+, resulting in the reduction of mechanical properties including strength, toughness, and flexibility [18–20]. Moreover, the low ionic conductivity and weak mechanical strength of SPEs have hindered their widespread adoption [11]. Current researches in SPEs mostly focus on improving their ionic conductivity. However, the inherent trade-off between ionic conductivity and mechanical strength of SPEs remains a critical challenge. Therefore, further optimization of SPEs is necessary to advance their practical applications in the future.

Except for the ionic conductivity and mechanical properties, the thickness of SPE is also an important parameter [21]. Excessive thickness will increase the weight and volume and reduce the energy density of the battery. Commercial separators for liquid electrolytes are only ~10 μm thick, giving liquid-based systems a significant advantage in energy density [22]. However, the thicknesses of conventional SPEs or polymer-based electrolytes are usually thicker than 100 μm [23,24], which limits the volumetric or specific energy density of solid-state batteries. However, if the thickness of the solid electrolyte decreases, the risk of battery short circuit will be greatly increased accordingly [25]. To obtain energy density comparable to that of liquid-electrolyte based lithium batteries, SPE need to have high ionic conductivity, good mechanical strength, ultrathin thickness (close to 10 μm), non-flammability, chemical stability and other characteristics [26,27]. Herein, a critical review is organized to regarding the advantages, and preparation strategies, fundamental requirements and the prospects of the ultrathin polymer-based electrolytes (UPE) (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, this review also provides a comprehensive overview of existing studies in the field, aiming to provide strategic guidance for the design of advanced UPE. We hope that this review can provide an accessible guide for future design and benefit the readers to accelerate the understanding of UPEs and create more possibilities for electrolytes.

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the ultrathin polymer-based electrolytes

2 Advantages and Material Constraints of Ultrathin Polymer Electrolytes

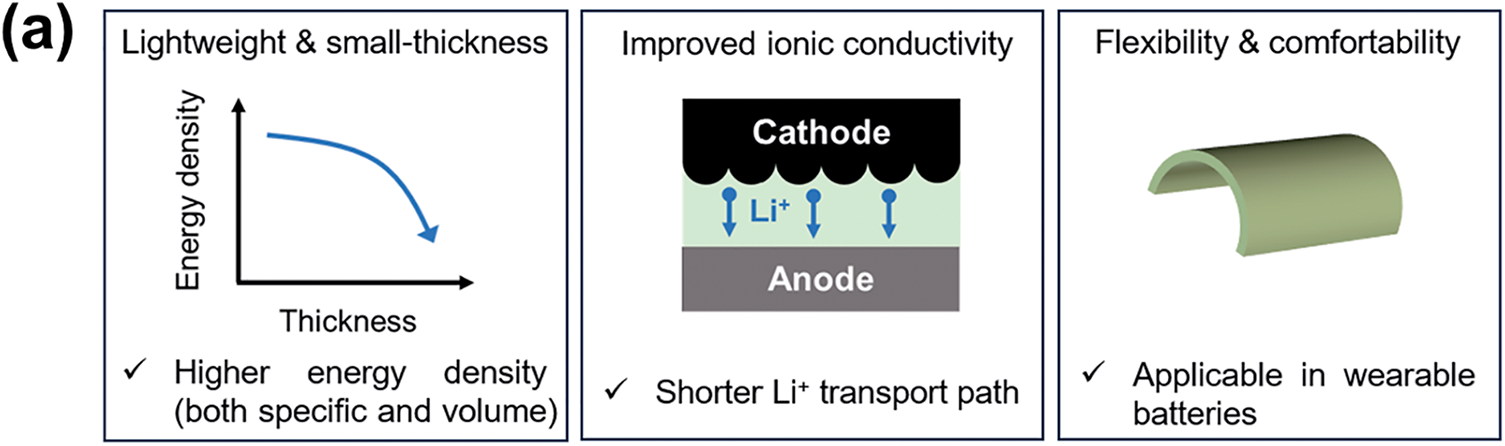

Reducing the thickness of solid electrolytes (SEs) broadens their physicochemical properties and application scope, particularly enhancing mechanical flexibility and thickness compatibility for wearable batteries. Fig. 2a summarizes UPE advantages: thin, lightweight nature to enhance battery energy density; to shorten Li+ transport distance and accelerate ion mobility; to enable flexible conformability for wearable devices.

Figure 2: (a) Summary of the advantages of UPE; (b) The relationship between area conductance and thickness

(1) Flexibility and lightweight. As the demands for high-performance complex electronic devices such as smart wristbands, implantable electronic devices, pacemakers, and soft wearable devices continue to increase, the development of wearable batteries that are as soft and elastic as human skin have been spurred on. Therefore, the replacement of liquid electrolytes or thick/fragile SCEs with highly flexible UPEs is recognized to apply in wearable batteries, greatly increasing its deformability and stretchability. Moreover, such UPEs enable significant reductions in both weight and volume of energy storage systems, offering a promising pathway to achieve higher volumetric energy densities through more compact device designs [28]. According to classical battery structure, the thicknesses of separator (separator and liquid electrolyte) is around 10–30 μm. For the thick SPE (>100 μm), the entire battery volume will significantly increase comparing with that of the batteries with liquid electrolyte, reducing the volumetric energy density. Similar to the volumetric energy density, the specific energy density is also greatly affected by the weight of electrolytes. Reducing the SPE thickness minimizes its volume ratio, while substantially increasing the energy density (up to 400 Wh kg−1), especially volumetric of LMBs [28,29]. Recently, Liu et al. reported a polyvinylidene fluoride-hexafluoropropylene (PVDF-HFP)-based UPEs (thickness ≈ 5 μm) with a high Young’s modulus (10.6 GPa). Benefit for the cis-conformation of the PVDF-HFP, such UPE enabled an increased ionic conductivity (2.47 × 10−4 S cm−1) and wide voltage window (4.7 V) [30]. The full cell with such UPE exhibited impressive energy densities of 516 Wh kg−1 (excluding packages). In addition, a polycarbonate-based UPE with a thickness of only 7.8 μm was developed, which has achieved significant improvements in rapid ion transport, Li0-dendrite inhibition, and long cycle life, which enabled the energy density of pouch batteries to reach 495 Wh kg−1 [31]. Zhang et al. reported a freestanding, scalable 10-μm UPE via in-situ thermal curing of PEGDA-infused electrospun PAN membranes. Paired with Li-metal anodes and high-loading NCM811 cathodes, the UPE-enabled pouch cell with impressive energy densities of 380 Wh kg−1 and 936 Wh L−1, demonstrating the potential of fiber-reinforced membranes for solid-state batteries [28].

(2) High ionic conductance. Apart from the energy density, the reduced thickness can also shorten ion transport pathways, thus improving ionic conductivity compared to typical solid-state electrolytes. Generally, three formulas need to be considered for the ion transport efficiency: the ionic conductivity, the ionic conductance and Li+ diffusion time formulas. According to the formula of ionic conductivity,

2.2 Material-Level Constraints

(1) Safety hazard. According to the previously reported works, when the mechanical strength of SPE is greater than 6 GPa, the growth of Li0 dendrites can be effectively inhibited. Obviously, for UPEs whose thickness is reduced by nearly 10 times, the strengths change caused by the volume change is more likely to cause a sharp decline in local mechanical properties, and then mechanical fracture, resulting in short circuit and even safety hazards. The stable electrolyte is fundamental to reliable battery cycling performance, requiring robust thermal stability to prevent degradation at high temperatures, interfacial stability to suppress side reactions at electrode interfaces, and electrochemical stability to withstand operating voltage windows. i) Thermal stability of the electrolyte is one of the most important parameters, as it is closely related to the safety of batteries. Many polymer electrolytes have low thermal stability compared to SCEs, limiting their high-temperature performance. Focusing on these characteristics, Cui and his coworkers reported a UPE with an 8.6-μm-thick nanoporous polyimide (PI) film filled with PEO/LiTFSI, which enabled the coin cell to operate for 200 cycles at 60°C, as well as the pouch cell to tolerate some abuse tests such as bending, twisting, cutting, and nail perforation (Fig. 3a) [8]. From another perspective, by combining ionic liquid (1-ethyl-3-methylimidazolium diacetate, EMIM:DCA), polyurethane (PU), and LiTFSI into a PE separator, a UPE with reduced phonon scattering was fabricated, where the robust and flexible PE matrix not only reduced the electrolyte thickness and enhanced the migration rate of Li+, but more importantly, provided a relatively regular thermal diffusion channel and reduced external phonon scattering for improving thermal conduction [22].

Figure 3: The fabrication of PPVD (upper panel), digital photo of pouch cell before and after folding (bottom-left panel), and nail penetration of the Li/PPVD@PEF/LiFePO4 pouch cell (bottom-right panel) [34] (Copyright 2024, with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry)

ii) Addressing interface compatibility between electrodes and UPEs is critical. For the interfacial stability between electrode and electrolyte, solid electrolytes with ultra-thin thickness are easier to happen micro-short circuits compared with thicker SPEs, because UPE would become thinner by dendritic penetration or reaction (corrosion). The local heat generated by micro-short circuits can quickly melt UPE in a short time, resulting in serious thermal runaway [35]. Besides, the SPE will also have some decomposition reactions on the electrode surface, which results in degradation of the electrolyte, rough deposition and the increased resistance within the battery. iii) The electrochemical window is also a challenge for polymer-based electrolyte, especially for the UPE. For the design principle of UPE, it is necessary to consider the functional groups distribution and adjust the crosslinking degree to improve the electrochemical window.

(2) Interplay between the structure/composition of polymer matrix and comprehensive performance. Stable electrolytes are essential to reliable battery cycling performance that requires robust thermal stability to prevent degradation at high temperatures, interfacial stability to suppress side reactions at electrode interfaces, as well as electrochemical stability to withstand operating voltage windows. For the design principle of UPE, it is necessary to consider the functional groups distribution and crosslinking degree of the network on comprehensive performance. Taking PEO-based electrolytes as an example, their mechanical strength, cation transport number and electrochemical stable window (ESW) is relatively low. Thus, three effective strategies are employed through molecular structure design, the use of interface-stabilizing additives and composite materials. To address these limitations, Gao et al. developed a flexible, mechanically robust 5-μm UPE composed of poly[(poly(ethylene glycol) methyl ether methacrylate)-r-(vinyl ethylene carbonate)-r-(dimethyl aminopropyl methacrylamide)-r-(polyethylene glycol dimethacrylate)] (PPVD) and thin separator. As shown in Fig. 3b, this UPE overcomes the poor mechanical properties and low voltage window of PEO electrolytes, improving electrochemical performance [34]. In this structure, poly(ethylene glycol) units act as the ionic conductor, and vinyl ethylene carbonate units maintain chemical stability and mechanical strength. By using additives, Wang et al. developed an ultrathin promoted electrolyte (UPE) that integrates three key advantages, including an ultralow thickness of 6 μm, tip electrostatic shielding, and inorganic-rich interphase promotion [36]. This UPE, fabricated by incorporating a CsNO3 additive, can significantly enhance the electrochemical performance of solid-state LMBs. It can be seen that the fundamental way to enhance the stability of the electrolyte is to stabilize the polymer matrix within electrolyte. This can be achieved by modifying the molecular structure to incorporate high-voltage units (e.g., carbonate), or by using an additive-based approach to fabricate a stable interphase before polymer decomposes.

Despite considerable attention on the advantages of UPEs, the relationship between electrolyte thickness and battery electrochemical performance are barely discussed. Herein, we summarized the cycle numbers and the thickness of UPE as shown in Fig. 4 [8,34,37–48]. The thinner UPEs (7–15 μm thickness) enable longer cycle numbers of batteries compared to the thicker counterparts (15–30 μm). This enhanced performance in those with thinner UPE is probably attributed to the approximately 10 μm thickness facilitating more effective and faster Li-ion transport, potentially reducing internal polarization and thereby promoting stable cycling.

Figure 4: Reported studies of the relationship between the thickness of UPE and their cycle numbers of the corresponding batteries [8,34,37–48]

3 Design and Fabrication Strategies for Ultrathin Polymer Electrolytes

Energy density is one of the key indicators that affects the practical application of solid-state battery, and it significantly depends on the thickness or content of SSE. It is necessary to translate the existing polymer synthesis strategies (such as solution/slurry casting, band casting, solution perfusion, in-situ polymerization, etc.) to construct various UPEs [29]. The solution casting process consists of multiple steps, where the polymer is dissolved in a solvent to form a solution, and then spread the solution on a substrate and evaporate the solvent to form a thin film [41]. Tape casting has been widely used to produce large and thin electrolyte film [39]. The process involves casting a slurry-containing electrolyte onto a flexible substrate using an adjustable doctor’s blade, followed by solvent evaporation and film detachment. Solution infusion is also the common approach to fabricate polymer-based electrolyte (thick or thin), which is based on the infusion of electrolyte (mainly SPE)-containing slurry or solution into a porous substrate/network [36]. While the in-situ polymerization within the cell is also much easier process to prepare the SPE because its assembly method is consistent with that of the liquid battery [34]. In this way, the electrolyte thickness depends on the thickness of porous separator. In addition to synthetic strategies, the challenge of building UPE with ultra-thickness also needs to be overcome, namely, the mechanical strength that decreases with thickness. Therefore, to separate the cathode and anode, the UPE need a robust matrix or substrate. Herein, building upon the aforementioned-synthesis method, UPEs with an ultrathin thickness are divided into two categories, freestanding UPEs and non-freestanding UPEs. For comparison, a systematic comparison of their electrochemical and mechanical performance is summarized in Table 1.

3.1 Freestanding Single-Layer Ultrathin Polymer Electrolytes

Owing to their low modulus, ultrathin SSEs present significant challenges in the preparation of single-layer membranes (Fig. 5a). To address this, a solution infusion method can be employed, where a mixture solution (polymer/salts or liquid solvent/salts) is infiltrated into an ultrathin porous substrate (film or 3D fiber-based network) to fabricate single-layer UPE membranes, where thickness depends on the porous membrane [26,30]. Meanwhile, the assembled UPE combing polymer and robust porous membrane can maintain high mechanical strength in the ultra-thin state, effectively improving the weak mechanical properties of the polymer. For instance, to solve the limitations of flammability and weak mechanical modulus of the most studied PEO and PEO-based electrolyte, Cui and his team reported an UPE by filling PEO/LiTFSI to a 8.6 μm-thick nanoporous polyimide (PI) film with vertical Li-ion transport channels that maintains a high ionic conductivity of 2.3 × 10−4 S cm−1 at 30°C [8]. Remarkably, this UPE exhibited excellent cycle stability (200 cycles at 0.5 C) even in abuse tests. Inspired by tube brushes coupling hardness with softness, Zhou et al. reported a polymer bottlebrush UPE with 10 μm thickness (named as BC-g-PLiSTFSI-b-PEGM) as an effective strategy to well balance the mechanical strength, ion conductivity and cation transport number of polymer electrolytes. Such polymer bottlebrush UPE with high Young’s modulus (1.9 GPa) enabled a reversible Li plating/stripping process over 3300 h in Li/Li symmetric cell at a current density of 1 mA cm−2 [38].

Figure 5: (a) The illustration of freestanding single-layer UPE; (b) The cross-sectional scanning electron microscopy (SEM) of in situ polymerized UPE and (c) the comparison of the ionic conductivities and conductance [34] (Copyright 2024, with permission from The Royal Society of Chemistry); (d) The illustration of freestanding multilayer UPE; (e) The cycling performance of the double layer polymer electrolyte and others [52] (Copyright 2022, with permission from American Chemical Society); (f) The illustration of non-freestanding UPE; (g) The fabrication process of electrode-supported electrolyte [53] (Copyright 2024, with permission from American Chemical Society)

Beside the polymer in robustness fiber-based network, the slurry casting process can also fabricate an UPE membrane. By introducing inorganic or organic filler into the electrolyte, it is beneficial to enhance the mechanical robustness of the electrolyte membrane, which is suitable for fabricating UPE [49]. Introducing the ceramic fillers into polymer can also help to enhance the Li-ion transport property of UPEs [50,51]. With a modification process, Al2O3-SO3Li nanoparticles were synthesized and integrated as fillers into polymer composites, enabling the fabrication of a UPE with superior Li+ transport properties [51]. Wang et al. reported a mechanically robust quasi-solid-state UPE, where a well-defined polystyrene-b-poly(ethylene oxide) acted as matrix, nano-size LLZTO acted as fillers, and fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) was employed as plasticizer [41]. Such quasi-solid-state UPE with a thickness of merely 12 μm was fabricated by using classical casting process, and achieved an elastic modulus of 2.7 GPa and a remarkable ionic conductivity 1.3 mS cm−1 at 30°C. Also, the integrated UPE can be fabricated by in situ polymerization within the cell. As shown in Fig. 5b, Gao et al. reported a flexible and mechanically robust UPE with 5 μm-thick by integrating polyethylene (PE) film with an in situ polymerized polymer. As shown in Fig. 5c, such PE based UPE exhibited an ionic conductivity of 2.0 × 10−2 mS cm−1 (ionic conductance: 0.1 S), enabling a Li//LiFePO4 full cell with excellent cycling stability with capacity retention of 85.7% over 500 cycles [34].

3.2 Freestanding Multilayer Ultrathin Polymer Electrolytes

For most single-layer polymer electrolytes, it is struggled to meet all requirements, such as lithium-metal stability, high-voltage stability, high mechanical strength, interface compatibility and so on. In contrast, UPEs with multi-layer structure can make up for the limitations of the single-layer structure, and conform to surfaces and interfaces in solid-state batteries, ensuring better electrochemical performance and compatibility with electrodes of higher energy density (Fig. 5d). Its hierarchical architecture endows key functions. On the anode side (particularly lithium metal), it employs materials (e.g., PEO-based polymers) that maintain high interfacial compatibility with alkali-metal, or inorganic 2D materials to create a robust physical barrier characterized by high modulus and toughness that effectively suppresses lithium dendrite penetration while enhancing safety [43,45]. On the cathode side, high-voltage-stable polymers with strong adhesion (e.g., poly(acrylonitrile) (PAN)) optimize interfacial contact and mitigate side reactions [54]. For example, Arrese-Igor and his coauthors reported an improved cycling performance of the LiNixMnyCozO2 cathode-based batteries using a double layer polymer electrolyte (Fig. 5e), where PEO is retained in anolyte and replaced in the catholyte with poly(propylene carbonate) (PPC) [52]. Liu et al. develop a composite UPE (PAN–LiClO4–boron nitride nanoflake (BNNFs)) modified with a boron nitride layer, named as m-PPL [45]. Thanks to the BNNFs, the composite UPE possessed both high Young’s modulus (563.7 MPa) and ultrathin thickness of 13.5 mm (12.0 mm for the composite UPE and 1.5 mm for the BNNFs layer). Wang et al. also reported an UPE consisting of polyethylene (PE) membrane (backbone) and poly (ethylene glycol) methyl ether acrylate (PEGMA) and LiTFSI complex (filler). While the porous poly (methyl methacrylate)-polystyrene (PMMA-PS) interface layer tightly attached to both sides of PE and effectively improved the interface compatibility between the electrolyte and the electrode. The resulting 10 μm-thick SPE had an ultra-high ionic conductivity of 34.84 mS cm−1 at room temperature, a mechanical property of 103.0 MPa, and an elongation of 142.3% [37].

3.3 Non-Freestanding Ultrathin Polymer Electrolytes

Beside the preparation of filling polymer electrolyte into the robust network, the design of a cathode-supported UPE is also proposed, where the electrolyte is directly coated on the electrode, not only eliminating the use of inert supports, but also strengthening the interface contact between the porous electrode and electrolyte (Fig. 5f) [43]. This approach shows great promise for developing stretchable Li-ion batteries (LIBs). Specifically, Wang et al. developed a polymer electrolyte based on a poly(ethylene glycol methyl ether acrylate)-ionic liquid/lithium salt system, achieving a chain-liquid synergistic effect (Fig. 5g). Intrinsically stretchable electrodes were constructed by embedding Ag nanowire/electrode material composites into poly(dimethylsiloxane) substrates, synergistically enabling stretchable LIBs [53]. Hu et al. developed a novel in situ polymerized integrated UPE/cathode design, where the LiNixCoyMnzO2 (NCM) cathode supported the PVC/SN-LLZTO electrolyte, and the polymer provided ion transport channel [40]. In this type of integrated UPE/cathode, the ultrathin ceramic layer (LLZTO) supported on the cathode served dual functions: (1) as a rigid structural framework to prevent cathode-anode contact, and (2) as active inorganic fillers that reinforced the mechanical properties of the in situ-polymerized vinylene carbonate (VC)-based electrolyte.

4 Key Challenges and Future Research Directions

4.1 Wide-Operation Temperature

Expect the demand for ionic conductivity at ambient conditions and the explanation of electrochemical stability window, a functional UPE for practical current densities (>3 mA cm−2) and capacities (>4 mAh cm−2) is also challenging. Considering the practical applications, choosing a higher current density for testing can be close to real application scenario, and the durability of the UPE can be truly evaluated. Lee et al. prepared an elastomer-based 25-μm-thick UPE containing plastic-crystal (built-in PCEE) with a high ionic conductivity of 1.1 mS cm−1 at 20°C and high cation transport number of 0.75 [44]. At a high current density of 10 mA cm−2, the Li/Li symmetric cell with the built-in PCEE showed excellent cycling performance with low polarization over 1500 h. Also, the full cell using high-loading NCM cathode (10 mg cm−2) and thin Li anode (low negative/positive capacity (N/P) ratio of 3.4) delivered high specific energy exceeding 410 Wh kg−1 at ambient temperature. Such high operating current densities are rarely achieved in most of reported solid-state batteries, as most ultrathin electrolytes exhibit values <1 mA cm−2. We propose that the exceptionally high operating current density reported here is probably attributable to its high cation transport number and superior mechanical toughness. Relevant reports support the positive correlation between cation transport number and achievable current density [55–57]. However, the lower current densities typically reported in other UPE-based reports are influenced by multiple factors, including the insufficient mechanical strength, low interfacial contact, low cation transport number, etc.

4.2 Wide-Operation Temperature

The sluggish ion transport kinetics is also one of the major challenges for practical application. Especially, due to their weak thermal stability, the UPEs need to work at ambient temperature or undergo thermal stability enhancement. For improving the thermal stability of the UPE, Cui and his team reported a UPE with comparable thicknesses to commercial organic separators (~10 μm), which consists of PEO/LiTFSI and nanoporous polyimide (PI) film [8]. This designed UPE shows a balance between high ionic conductivity and high modulus, and the flame-retardant PI film can greatly improve the thermal stability of the UPE. Recently, an all solid-state composite polymer electrolyte with 13.2 μm thickness was reported by Zhu and his coauthors [58]. This UPE was derived from lignin, which showed high ionic conductivity, enabled stable cycling for more than 6500 h at a current density of 0.5 mA cm−2 with virtually no Li0 dendrites growth, and maintained good cycling performance of full cell at −20°C.

For actual UPE, operability/scalability is an important consideration in actual mass production. However, too small thickness may make the polymer electrolyte fail to form a stable and robust interlayer to separate cathode and anode inside the battery. This not only causes difficulties of the battery assembly process, but also may not be conducive to the stable cycle of the battery. Hence, fabrication of UPEs requires the maturity of the preparation technology, including precise control and advanced techniques, which can increase production costs and the difficulty of large-scale preparation. Liang et al. reported a high denser UPE consisting of PEO/LiTFSI and porous poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (PTFE) matrix, ensuring the high mechanical strength of 63 MPa. The UPE was synthesized by depositing a PEO/LiTFSI mixture solution onto a PTFE matrix, subsequently consolidated via high-temperature hot-pressing. This method is compatible with roll-to-roll manufacturing, enabling scalable production [46]. The thickness of such UPE was followed with the thickness of PTFE. For further shorten the Li+ transport pathway, a 6-μm PEO/LiTFSI/PTFE was also prepared to achieve a better rate performance at 1 C.

4.4 Circularity and Sustainability Considerations

Traditional electrolytes face limitations in sustainability give the concerns over resource depletion, hazardous waste, and complex wastes treatment. Therefore, designing non-toxic, biodegradable polymer electrolytes can minimize their environmental footprint throughout their entire life cycle, which is essential for realizing the full potential of next-generation batteries as genuinely sustainable energy solutions [59]. Such electrolytes can be prepared via methods including using bioderived monomers, incorporating dynamic covalent bonds to facilitate disassembly, or employing closed-loop post-treatment approaches. For instance, a soy protein isolate-based polymer electrolytes with self-healing property were designed, which can be reshaped and recycled under certain conditions [60]. Alongside this biomass material, environmental benefits can also be realized through the design of recyclable polymers. Recently, Wang et al. reported a fluoro-containing graft copolymer with close-loop and selective recyclability of side chains, which can present a high ionic conductivity of 6.3 ×10−4 S cm−1 at 25°C and enable the LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2/Li cell with capacity retention over 80.0% after 340 cycles [61]. In short, such recyclable and environmentally friendly polymer electrolyte provides a potential solution to take full advantage of polymers and alleviate environmental concerns.

5 Perspectives and Conclusions

The pursuit of wearable and flexible electronics has accelerated the development of next-generation energy storage systems with both high safety and energy density. Especially for wearable device applications, compared to thick and heavy solid-state electrolytes, flexible and lightweight UPEs with advancements in energy storage can greatly reduce the weight and content of electrolytes in the battery, promising for high-performance lithium and other alkali-metal batteries. Moreover, the reduced thickness enables the polymer electrolyte to have a shorter lithium-ion transport path, which is conducive to reducing the internal resistance and improving the ionic conductance of the electrolyte. Thus, such UPEs are expected to improve the rate cycle performance of the battery. In addition, their mechanical properties (flexibility and strength) are conducive to their application in cost-effective fabrication techniques (large-scale manufacturing), like roll-to-roll processing, which makes them maintain the advantages of scalability and cost.

In this review, we summarized the recent progresses in UPEs, including their fabrication, advantages, limitation and their perspectives. Moreover, the effect of electrolyte thickness on ionic conductance and energy density at the cell level was assessed, and prospects for high-energy density batteries based on UPEs were proposed. We sincerely hope that this review will serve as a valuable reference for the synthetic design of UPEs. Overall, the UPEs represent a transformative leap in developing safer, more flexible, and higher-efficiency energy devices. However, achieving their full potential will require the development of other materials with recyclable and environmentally friendly. Continuous innovation is therefore essential.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant Nos. 52373275 and 52303290, received by Peng-Fei Cao and Jiayao Chen, respectively.

Author Contributions: Xinyuan Shan: Writing—original draft, Methodology, Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis. Yuan Wei: Review. Jiayao Chen: Review & editing, Funding acquisition. Peng-Fei Cao: Review & editing, Funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: This study did not generate any new datasets. All data analyzed are from publicly available sources, as cited in the manuscript.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Yang H, Li S, Wu Y, Bao X, Xiang Z, Xie Y, et al. Advances in flexible magnetosensitive materials and devices for wearable electronics. Adv Mater. 2024;36(37):e2311996. doi:10.1002/adma.202311996. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Han Y, Liu Y, Zhang Y, He X, Fu X, Shi R, et al. Functionalized quasi-solid-state electrolytes in aqueous Zn-ion batteries for flexible devices: challenges and strategies. Adv Mater. 2025;37(1):e2412447. doi:10.1002/adma.202412447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Lu C, Jiang H, Cheng X, He J, Long Y, Chang Y, et al. High-performance fibre battery with polymer gel electrolyte. Nature. 2024;629(8010):86–91. doi:10.1038/s41586-024-07343-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Sarkar S, Thangadurai V. Critical current densities for high-performance all-solid-state Li-metal batteries: fundamentals, mechanisms, interfaces, materials, and applications. ACS Energy Lett. 2022;7(4):1492–527. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.2c00003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Liu B, Zhang JG, Xu W. Advancing lithium metal batteries. Joule. 2018;2(5):833–45. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2018.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Mukhopadhyay A, Jangid MK. Li metal battery, heal thyself. Science. 2018;359(6383):1463. doi:10.1126/science.aat2452. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Luo D, Zheng L, Zhang Z, Li M, Chen Z, Cui R, et al. Constructing multifunctional solid electrolyte interface via in situ polymerization for dendrite-free and low N/P ratio lithium metal batteries. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):186. doi:10.1038/s41467-020-20339-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Wan J, Xie J, Kong X, Liu Z, Liu K, Shi F, et al. Ultrathin, flexible, solid polymer composite electrolyte enabled with aligned nanoporous host for lithium batteries. Nat Nanotechnol. 2019;14(7):705–11. doi:10.1038/s41565-019-0465-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Lopez J, Mackanic DG, Cui Y, Bao Z. Designing polymers for advanced battery chemistries. Nat Rev Mater. 2019;4(5):312–30. doi:10.1038/s41578-019-0103-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Manthiram A, Yu X, Wang S. Lithium battery chemistries enabled by solid-state electrolytes. Nat Rev Mater. 2017;2(4):16103. doi:10.1038/natrevmats.2016.103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhao Q, Stalin S, Zhao CZ, Archer LA. Designing solid-state electrolytes for safe, energy-dense batteries. Nat Rev Mater. 2020;5(3):229–52. doi:10.1038/s41578-019-0165-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Zou S, Yang Y, Wang J, Zhou X, Wan X, Zhu M, et al. In situ polymerization of solid-state polymer electrolytes for lithium metal batteries: a review. Energy Environ Sci. 2024;17(13):4426–60. doi:10.1039/d4ee00822g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Fenton DE, Parker JM, Wright PV. Complexes of alkali metal ions with poly(ethylene oxide). Polymer. 1973;14(11):589. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(73)90146-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Jin Y, Zong X, Zhang X, Liu C, Li D, Jia Z, et al. Interface regulation enabling three-dimensional Li1.3Al0.3Ti1.7(PO4)3-reinforced composite solid electrolyte for high-performance lithium batteries. J Power Sources. 2021;501:230027. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2021.230027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Ren Z, Li J, Gong Y, Shi C, Liang J, Li Y, et al. Insight into the integration way of ceramic solid-state electrolyte fillers in the composite electrolyte for high performance solid-state lithium metal battery. Energy Storage Mater. 2022;51:130–8. doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2022.06.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Jeon H, Hoang H, Kim D. Flexible PVA/BMIMOTf/LLZTO composite electrolyte with liquid-comparable ionic conductivity for solid-state lithium metal battery. J Energy Chem. 2022;74:128–39. doi:10.1016/j.jechem.2022.07.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Xu G, Shangguan X, Dong S, Zhou X, Cui G. Formulation of blended-lithium-salt electrolytes for lithium batteries. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59(9):3400–15. doi:10.1002/anie.201906494. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Yuan F, Chen HZ, Yang HY, Li HY, Wang M. PAN-PEO solid polymer electrolytes with high ionic conductivity. Mater Chem Phys. 2005;89(2–3):390–4. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2004.09.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Tsuchida E, Ohno H, Tsunemi K, Kobayashi N. Lithium ionic conduction in poly (methacrylic acid)-poly (ethylene oxide) complex containing lithium perchlorate. Solid State Ion. 1983;11(3):227–33. doi:10.1016/0167-2738(83)90028-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Zhou C, Bag S, Lv B, Thangadurai V. Understanding the role of solvents on the morphological structure and Li-ion conductivity of poly(vinylidene fluoride)-based polymer electrolytes. J Electrochem Soc. 2020;167(7):070552. doi:10.1149/1945-7111/ab7c3a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Wang Q, Wang S, Lu T, Guan L, Hou L, Du H, et al. Ultrathin solid polymer electrolyte design for high-performance Li metal batteries: a perspective of synthetic chemistry. Adv Sci. 2022;10(1):e2205233. doi:10.1002/advs.202205233. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Shi X, Jia Z, Wang D, Jiang B, Liao Y, Zhang G, et al. Phonon engineering in solid polymer electrolyte toward high safety for solid-state lithium batteries. Adv Mater. 2024;36(33):e2405097. doi:10.1002/adma.202405097. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Zhang L, Gao H, Xiao S, Li J, Ma T, Wang Q, et al. In-situ construction of ceramic-polymer all-solid-state electrolytes for high-performance room-temperature lithium metal batteries. ACS Mater Lett. 2022;4(7):1297–305. doi:10.1021/acsmaterialslett.2c00238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Han S, Wen P, Wang H, Zhou Y, Gu Y, Zhang L, et al. Sequencing polymers to enable solid-state lithium batteries. Nat Mater. 2023;22(12):1515–22. doi:10.1038/s41563-023-01693-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Luo H, Du J, Fu J, Zhang Q, Hu X, Liu B, et al. Phase-regulated ultrathin PVDF-based electrolytes for dynamic dendrite suppression in solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nano Res. 2025. doi:10.26599/nr.2025.94907631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lin X, Yu J, Effat MB, Zhou G, Robson MJ, Kwok SCT, et al. Ultrathin and non-flammable dual-salt polymer electrolyte for high-energy-density lithium-metal battery. Adv Funct Materials. 2021;31(17):2010261. doi:10.1002/adfm.202010261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wu J, Yuan L, Zhang W, Li Z, Xie X, Huang Y. Reducing the thickness of solid-state electrolyte membranes for high-energy lithium batteries. Energy Environ Sci. 2021;14(1):12–36. doi:10.1039/d0ee02241a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Zhang Y, Yu J, Shi H, Wang S, Lv Y, Zhang Y, et al. Fiber-reinforced ultrathin solid polymer electrolyte for solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Adv Funct Materials. 2025;35(25):2421054. doi:10.1002/adfm.202421054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yang X, Adair KR, Gao X, Sun X. Recent advances and perspectives on thin electrolytes for high-energy-density solid-state lithium batteries. Energy Environ Sci. 2021;14(2):643–71. doi:10.1039/d0ee02714f. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Liu L, Shi Y, Liu M, Zhong Q, Chen Y, Li B, et al. An ultrathin solid electrolyte for high-energy lithium metal batteries. Adv Funct Materials. 2024;34(39):2403154. doi:10.1002/adfm.202403154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Xia S, Zhang X, Jiang Z, Wu X, Yuwono JA, Li C, et al. Ultrathin polymer electrolyte with fast ion transport and stable interface for practical solid-state lithium metal batteries. Adv Mater. 2025:e2510376. doi:10.1002/adma.202510376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Wu J, Rao Z, Cheng Z, Yuan L, Li Z, Huang Y. Ultrathin, flexible polymer electrolyte for cost-effective fabrication of all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Adv Energy Mater. 2019;9(46):1902767. doi:10.1002/aenm.201902767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Liu L, Mo J, Zhou R, Yang T, Xu R, Tu J, et al. Ultrathin solid composite electrolytes for long-life lithium metal batteries. J Energy Storage. 2025;114:115777. doi:10.1016/j.est.2025.115777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Gao S, Ma M, Zhang Y, Li L, Zhu S, He Y, et al. In situ construction of an ultra-thin and flexible polymer electrolyte for stable all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. J Mater Chem A. 2024;12(16):9469–77. doi:10.1039/d3ta07586a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Ma Y, Wan J, Yang Y, Ye Y, Xiao X, Boyle DT, et al. Scalable, ultrathin, and high-temperature-resistant solid polymer electrolytes for energy-dense lithium metal batteries. Adv Energy Mater. 2022;12(15):2103720. doi:10.1002/aenm.202103720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Wang Z, Yu X, Liu Y, Deng L, Wang S, Liu H, et al. An integrated ultrathin, tip-electrostatic-shielding and inorganic interphase-promoting polymeric electrolyte design for high-performance all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nano Energy. 2025;134:110582. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2024.110582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Wang Z, Shen L, Deng S, Cui P, Yao X. 10 μm-thick high-strength solid polymer electrolytes with excellent interface compatibility for flexible all-solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Adv Mater. 2021;33(25):e2100353. doi:10.1002/adma.202100353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Zhou M, Liu R, Jia D, Cui Y, Liu Q, Liu S, et al. Ultrathin yet robust single lithium-ion conducting quasi-solid-state polymer-brush electrolytes enable ultralong-life and dendrite-free lithium-metal batteries. Adv Mater. 2021;33(29):e2100943. doi:10.1002/adma.202100943. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Zhang Z, Fan W, Cui K, Gou J, Huang Y. Design of ultrathin asymmetric composite electrolytes for interfacial stable solid-state lithium-metal batteries. ACS Nano. 2024;18(27):17890–900. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c04429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Hu JK, Gao YC, Yang SJ, Wang XL, Chen X, Liao YL, et al. High energy density solid-state lithium metal batteries enabled by in situ polymerized integrated ultrathin solid electrolyte/cathode. Adv Funct Materials. 2024;34(18):2311633. doi:10.1002/adfm.202311633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Wang Q, Xu H, Liu Z, Chi SS, Chang J, Wang J, et al. Ultrathin, mechanically robust quasi-solid composite electrolyte for solid-state lithium metal batteries. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(17):22482–92. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c01426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Deng J, Zuo X, Zhang H, Fei F, Zhou X, Mai L, et al. Lipoic acid-assisted in situ integration of ultrathin solid-state electrolytes. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2023;6(6):3321–8. doi:10.1021/acsaem.2c03922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Lin Y, Wu M, Sun J, Zhang L, Jian Q, Zhao T. A high-capacity, long-cycling all-solid-state lithium battery enabled by integrated cathode/ultrathin solid electrolyte. Adv Energy Mater. 2021;11(35):2101612. doi:10.1002/aenm.202101612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Lee MJ, Han J, Lee K, Lee YJ, Kim BG, Jung KN, et al. Elastomeric electrolytes for high-energy solid-state lithium batteries. Nature. 2022;601:217–22. doi:10.1038/s41586-021-04209-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Liu K, Wu M, Jiang H, Lin Y, Zhao T. An ultrathin, strong, flexible composite solid electrolyte for high-voltage lithium metal batteries. J Mater Chem A. 2020;8(36):18802–9. doi:10.1039/d0ta05644h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Liang Q, Chen L, Tang J, Liu X, Liu J, Tang M, et al. Large-scale preparation of ultrathin composite polymer electrolytes with excellent mechanical properties and high thermal stability for solid-state lithium-metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater. 2023;55:847–56. doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2022.12.039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Cai D, Zhang S, Su M, Ma Z, Zhu J, Zhong Y, et al. Cellulose mesh supported ultrathin ceramic-based composite electrolyte for high-performance Li metal batteries. J Membr Sci. 2022;661:120907. doi:10.1016/j.memsci.2022.120907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Li Y, Yang X, He Y, Li F, Ouyang K, Ma D, et al. A novel ultrathin multiple-kinetics-enhanced polymer electrolyte editing enabled wide-temperature fast-charging solid-state zinc metal batteries. Adv Funct Materials. 2024;34(4):2307736. doi:10.1002/adfm.202307736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Ding H, Wang M, Shan X, Yang G, Tian M. Advancements in active filler-contained polymer solid-state electrolytes for lithium-metal batteries: a concise review. Supramol Mater. 2025;4:100097. doi:10.1016/j.supmat.2025.100097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Chang S, Cao J, Wang A, Zhang M, Yang F, Xu J, et al. In situ reconstruction of the ceramic particle surface boosting high-performance and ultrathin hybrid solid-state electrolyte. ACS Nano. 2025;19(9):8621–31. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c14459. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

51. Li B, Liu K, Wang Z, Zhao Y, Lv Y, Shi L, et al. An ultrathin polymer-based solid-state electrolyte membrane with high conductivity for lithium metal batteries operable at –25°C. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2025;698:138071. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2025.138071. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Arrese-Igor M, Martinez-Ibañez M, Pavlenko E, Forsyth M, Zhu H, Armand M, et al. Toward high-voltage solid-state Li-metal batteries with double-layer polymer electrolytes. ACS Energy Lett. 2022;7(4):1473–80. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.2c00488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Wang S, Xiao S, Cai H, Sun W, Wu T, Wang Y, et al. Elastic polymer electrolytes integrated with in situ polymerization-transferred electrodes toward stretchable batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2024;9(8):3672–82. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.4c01254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Yao M, Ruan Q, Pan S, Zhang H, Zhang S. An ultrathin asymmetric solid polymer electrolyte with intensified ion transport regulated by biomimetic channels enabling wide-temperature high-voltage lithium-metal battery. Adv Energy Mater. 2023;13(12):2203640. doi:10.1002/aenm.202203640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Shan X, Song Z, Ding H, Li L, Tian Y, Sokolov AP, et al. Polymer electrolytes with high cation transport number for rechargeable Li-metal batteries: current status and future direction. Energy Environ Sci. 2024;17(22):8457–81. doi:10.1039/d4ee03097d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Shan X, Morey M, Li Z, Zhao S, Song S, Xiao Z, et al. A polymer electrolyte with high cationic transport number for safe and stable solid Li-metal batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2022;7(12):4342–51. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.2c02349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

57. Diederichsen KM, McShane EJ, McCloskey BD. Promising routes to a high Li+ transference number electrolyte for lithium ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2(11):2563–75. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

58. Liu Y, Wang P, Yang Z, Wang L, Li Z, Liu C, et al. Lignin derived ultrathin all-solid polymer electrolytes with 3D single-ion nanofiber ionic bridge framework for high performance lithium batteries. Adv Mater. 2024;36(27):e2400970. doi:10.1002/adma.202400970. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Harte T, Dharmasiri B, Eyckens DJ, Henderson LC. Closing the loop: recyclable solvate ionic liquids in solid polymer electrolytes for circular economy. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2024;12(43):16114–25. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.4c07487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Gu W, Li F, Liu T, Gong S, Gao Q, Li J, et al. Recyclable, self-healing solid polymer electrolytes by soy protein-based dynamic network. Adv Sci. 2022;9(11):e2103623. doi:10.1002/advs.202103623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Wang WR, Li Z, Li L, Min W, Song F, Yue C, et al. Closed-loop and selective recyclable fluoro-containing graft copolymers with diverse applications. Adv Mater. 2025. doi:10.1002/adma.202505158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools