Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence of LiCF3SO3 on the Conductivity and Other Characteristics of Methylcellulose/PVA Blend-Based Electrolytes

1 Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 Laboratory Management, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar, 32610, Malaysia

3 Pusat Pengajian Citra Universiti, Jalan Temuan, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia, Bangi, 43600, Malaysia

4 Department of Physics, Centre for Defence Foundation Studies, National Defence University of Malaysia, Sungai Besi Camp, Kuala Lumpur, 57000, Malaysia

5 Universiti Malaya Centre for Ionic Liquid (UMCiL), Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

6 Department of Applied Science, Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar, 32610, Malaysia

7 Centre of Innovative Nanostructure and Nanodevices (COINN), Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS, Seri Iskandar, 32610, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Muhammad Fadhlullah Shukur. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Innovative Smart Polymeric Materials for Sustainable Energy Solutions: Bridging Advances in Energy and Biomedical Applications)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 729-742. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.069060

Received 13 June 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Polymeric materials have emerged as a promising alternative to electrolytic solutions in energy storage applications. However, high crystallinity and poor ionic conductivity are the main barriers restricting their daily application. In this study, we propose a polymer electrolyte system consisting of methylcellulose-polyvinyl alcohol (MC-PVA) blend as host material and lithium trifluoromethanesulfonate (LiCF3SO3) as dopant, which was prepared using the solution-casting method. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis revealed a maximum conductivity of 5.42 × 10−6 S cm−1 with 40 wt.% LiCF3SO3. The key findings demonstrated that the variation in the dielectric loss (εi) and dielectric constant (εr) was significantly correlated with the variation in ionic conductivity. Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis was done to analyse the salt-polymer interaction by observing the shifting of selected bands. By deconvoluting FTIR spectra in the wavenumber range of 970–1100 cm−1, transport properties of electrolytes were investigated and found to be improved when the salt concentration was increased to 40 wt.%. Results from the X-ray diffraction (XRD) study suggested that the higher salt concentration promoted the formation of an amorphous phase, which is favourable for ionic conduction. Field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) study demonstrated that the addition of salt altered the surface morphology of MC-PVA.Keywords

Current research in energy storage is focusing on the use of solid polymer electrolyte (SPE) in energy devices due to its advantages over liquid electrolyte in terms of safety, mechanical stability, and energy density. SPE with excellent ionic conductivity is the key to high-performance energy devices. However, crystallinity is the major obstacle to ionic conductivity in SPE. Techniques like plasticization, blending polymers, and adding nanofillers have been reported in developing new high conducting SPE [1–4]. In the present work, our focus is on polymer blending which is a simple, economic and practicable method to develop new materials with tailored properties. As reported in [4], by manipulating the ratio of polymer blend components, the desired conductivity and amorphousness of SPE can be achieved. Blending can disrupt the crystalline regions of the host polymers which in turn increase the amorphous content where ion transport is more efficient [5,6]. In a report by Nadirah et al., the XRD results demonstrated that the blend of 50 wt.% polyacrylonitrile (PAN) and 50 wt.% MC is more amorphous than pure PAN and pure MC, as the intensity of the characteristic peak of PAN decreases [7]. A study by Wang et al. [8] showed that the conductivity of LiTFSI-based solid electrolytes with a polyvinylidene fluoride-polyethylene oxide (PVDF–PEO_ blend as the host polymer is higher (3.67 × 10−4 S cm−1) than that of unblended PVDF–LiTFSI (1.56 × 10−4 S cm−1) and PEO–LiTFSI (7.76 × 10−5 S cm−1) electrolytes. In this work, we used MC-PVA blend as the host material as both polymers have a high degree of solubility, excellent thermal stability and good film forming properties [9,10]. It was reported in [11] that the formation of hydrogen bonds between MC and PVA disrupts the crystalline regions, thereby increasing the degree of amorphousness.

Polymer doping is essential in providing charges in an SPE. This is because polymers are generally electrical insulators, thus exhibiting low conductivity as the number density of charge carriers in undoped polymers is very low. Shamsuri et al. [12] doped a PVA–MC blend, at a weight ratio of 1:1, with 40 wt.% ammonium thiocyanate (NH4SCN) which resulted in an increase in conductivity from 9.02 × 10−11 to 1.45 × 10−4 S cm−1. The authors attributed the conductivity enhancement to polymer–salt complexation, which increases the flexibility of the polymer backbone, thereby enabling ions to transport easily through the polymer chain network when an electric field is applied. In another study [13], the incorporation of 40 wt.% ammonium iodide (NH4I) into PVA-MC optimized the ionic conductivity to 2.34 × 10−5 S cm−1. This improvement was ascribed to the dominance of ion dissociation over ion reassociation, leading to an increased ion number density and enhanced conductivity. A good dopant must have a large-sized anion and low lattice energy as these requirements influence the salt dissociation. In this work, lithium trifluoremethanesulfonate (LiCF3SO3) dopant was chosen owing to its low lattice energy (725 kJ mol−1) and large anionic size (radius = 2.30 Å) [14,15]. Lattice energy decreases as the distance between ions increases, resulting in weaker electrostatic forces holding the ions together. These aspects can lead to a high degree of ion dissociation and help develop SPE. The concentration of salt is also critical to the conductivity. Increasing the salt concentration can lead to a higher number of free ions, which in turn improves conductivity [14]. According to the literature, optimal conductivity is typically achieved when the SPE is doped with 40–45 wt.% LiCF3SO3 [16–18]. Thus, in this work MC-PVA blend was doped with 10–40 wt.% LiCF3SO3. The effect of LiCF3SO3 concentration on the conductive properties of MC-PVA blend was investigated.

MC (Sigma), PVA (Aldrich) and LiCF3SO3 (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as purchased. A blend of MC-PVA at a 1:1 weight ratio underwent dissolution in 50 mL of distilled water with continuous stirring for 2 h. Then, LiCF3SO3 at different concentrations was added into the MC-PVA solutions and stirred until homogenous solution was obtained. All MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 solutions were then poured onto plastic Petri dishes and left at room temperature for 48 h for drying process. The dried SPEs were stored in a desiccator to avoid contamination and for further use. The samples with 10, 20, 30, and 40 wt.% salt were designated as Li10, Li20, Li30, and Li40, respectively, whereas Li0 denotes the undoped MC-PVA sample.

2.2 Electrolytes Characterisation

Impedance analyses were carried out using Metrohm Autolab Nova 2.1.7 at room temperature in the frequency range of 50 Hz–1 MHz. Electrolyte samples with thickness t were placed between two stainless steel electrodes in a sample holder. The ionic conductivity σ was determined using Eq. (1):

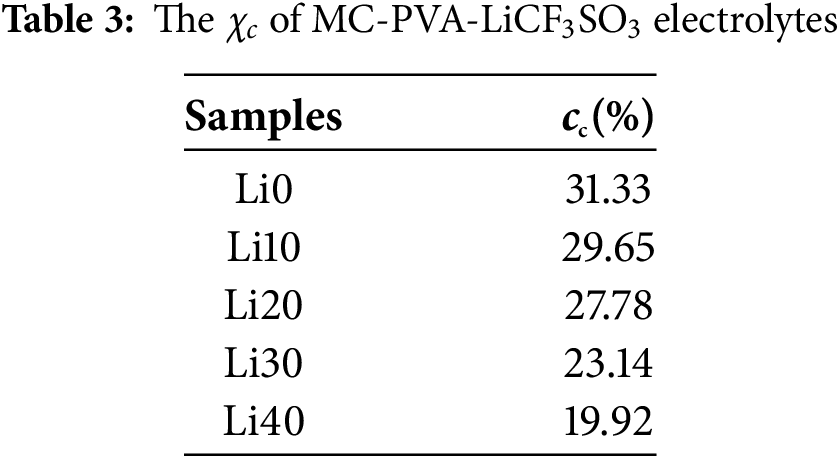

where Rb is the bulk resistance and A is the electrode/electrolyte contact area. FTIR spectroscopy was carried out using Perkin Elmer, Spectrum One spectrometer in a wavenumber range of 550–4000 cm−1 at 4 cm−1 resolution. The band at 970–1100 cm−1 was deconvoluted using the Gaussian/Lorentz function to compute the transport properties of MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3. XRD measurements were done using PANalytical X’Pert3 PRO X-ray diffractometer. Monochromatic Cu Kα X-rays of 1.5406 Å wavelengths (l) were radiated to the samples at a 2θ range of 5°–80°. The area of crystalline and amorphous hump were calculated to compute the degree of crystallinity (cc), which was obtained using Eq. (2):

The surface morphology of the electrolytes was carried out through Zeiss Supra 55Vp scanning electron microscope at 1000× magnification. The samples were sputter-coated with a thin layer of gold using EMITECH K550X sputter coater before being analysed.

Fig. 1 shows the Cole-Cole plot for MC-PVA-based SPEs with varying LiCF3SO3 concentrations at room temperature. Two distinct types of Cole-Cole plots are observed, one of which has a depressed semicircular arc only and the other plot has a depressed semicircular arc and an inclined slope. The semicircular arc corresponds to the bulk properties of the sample [19]. The inclined slope can be attributed to the formation of the electric double layer (EDL) resulting from the accumulation of charges at the electrolyte-electrode interfaces [20]. Inclination of the spike results from the electrode surface roughness [21]. The bulk resistance (Rb) for Cole-Cole plots having a depressed semicircular arc only was determined at the intersection of the semicircle curve with the real-axis. For Cole-Cole plots having a depressed semicircular arc and an inclined slope, the Rb was determined at the intersection of the semicircle with the inclined slope. Using the values of Rb, the conductivity was calculated using Eq. (1).

Figure 1: Cole-cole plot of (a) Li10, (b) Li20, (c) Li30 and (d) Li40

Fig. 2a depicts the room temperature conductivity of MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 electrolytes as a function of LiCF3SO3 concentration. The conductivity of the undoped MC-PVA blend electrolyte is 9.02 × 10−11 S cm−1, which is low since there are no charge carriers in the sample. The conductivity increases with increasing salt content and is optimized at 5.42 × 10−6 S cm−1 with 40 wt.% of LiCF3SO3. As more salts were added to the polymer, more ions were dissociated. As a result, the polymer backbone became more flexible which facilitated the conduction of ions when an electric field was applied to the samples [12]. In this work, the doping concentration was limited to 40 wt.% based on findings reported in the literature. In a study by Noor et al. [16], LiCF3SO3 salt concentrations higher than 40 wt.% resulted in a decrease in the conductivity of gellan gum-based electrolyte system. According to the authors, the reduction in conductivity is attributed to the ion aggregation, which suggests that the number of energetically favorable sites for mobile ions is maximized at 40 wt.% salt concentration.

Figure 2: Plot of (a) conductivity at room temperature against concentrations of LiCF3SO3 and (b) ac conductivity

In a study reported by Shamsuri et al. [12], the ionic conductivity of an MC–PVA blend doped with 40 wt.% NH4SCN reached 1.45 × 10−4 S cm−1. Meanwhile, incorporating 40 wt.% NH4I into the same polymer blend yielded a conductivity of 2.34 × 10−5 S cm−1 [13]. In comparison, the present LiCF3SO3-doped MC–PVA system exhibits lower conductivity than both ammonium salt-based systems. This is attributed to the higher lattice energy of LiCF3SO3 (725 kJ mol−1) compared to NH4SCN (597 kJ mol−1) and NH4I (608 kJ mol−1) [22]. A lower lattice energy allows salt to dissociate more ions, increasing the number of mobile charge carriers in the SPE system and thereby enhancing ionic conductivity [23].

The variation of conductivity with the change in number density of ions (n), ionic mobility (m) and diffusion coefficient (D) will be analysed and discussed in the FTIR analysis section. Analysis on alternating current conductivity (σac) spectra was carried out to understand the frequency-dependent conductivity behaviour of the MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 electrolytes. The σac was calculated using the Eq. (3):

where Zr is the real part of impedance and Zi is the imaginary part of impedance. As shown in Fig. 2b, the dc conductivity was obtained by extrapolating the plateau region toward zero frequency. An increase in dc conductivity is observed with increasing amount of LiCF3SO3 salt. The conductivity of SPE is strongly influenced by the mobility and number density of ion [24]. The dc conductivity values determined from ac conductivity data are in good agreement with the results calculated using bulk resistance. The highest dc conductivity, exhibited by Li40, is 7.63 × 10−6 S cm−1.

3.2 Dielectric and Loss Tangent Studies

Dielectric analysis of SPEs provides insights into polarization phenomena at the electrolyte–electrode interfaces as well as confirming the conductivity trend [12]. In such studies, two parameters are assessed, that is, dielectric constant (εr) and dielectric loss (εi). The εr shows how much charge can be stored by a material, while the εi represents the energy dissipated in moving ions and aligning dipoles when the electric field polarity reverses rapidly [25]. These two parameters were calculated using Eqs. (4) and (5):

where C0 is the vacuum capacitance and ω is the angular frequency. Fig. 3 illustrates variation of εr and εi with frequency for the MC–PVA–LiCF3SO3 electrolytes at room temperature. The Li40 exhibits the highest εr and εi over the entire frequency range. It is evident that the changes in εr and εi are consistent with the variation in conductivity. With the increase in salt concentration up to 40 wt.%, more charges are stored in the electrolyte which in turn increases the number density of mobile ions [26]. This result contributes to the increase in conductivity.

Figure 3: Plot of dielectric studies of (a) εr, (b) εI and (c) tanδ

The εr and εi are found to be higher at low frequencies compared to high frequencies. At the low frequency region, the majority of the charge carriers can accumulate at the electrolyte–electrode interfaces, resulting in electrode polarization [12,24–26]. When the electric field reverses direction, the charge carriers undergo deceleration, stop and accelerate in the opposite direction. This process generates heat via internal friction and energy loss. The degree of energy dissipated is represented by εi. The reversal of electric field direction takes place at a fast rate at higher frequencies. In this scenario, the charge carriers struggle to align themselves with the alternating electric field. This means that the charge carriers do not have sufficient time to accumulate at the interfaces, which contributes to the decrease in εr and εi [27].

The plot of loss tangent (tanδ) vs. frequency provides insights into relaxation phenomena. The value of tanδ was computed using Eq. (6):

The variation of tanδ with frequency for MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 electrolytes at room temperature is shown in Fig. 3b. The relaxation peak, indicated by the maximum of tanδ, appears at a higher frequency for higher conducting electrolytes. The relaxation time (tr) for each electrolyte was calculated using Eq. (7):

where fpeak is the frequency of the relaxation peak. The relaxation time resulted from the response of ions to changes in the direction of applied electric field [28]. The tr values for MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 are listed in Table 1. It can be observed that the highest conducting electrolyte (Li40) exhibits the shortest tr of 0.01 ms. Other studies have also reported that electrolytes with higher conductivity have shorter tr [20,29,30].

FTIR analysis was performed to provide information on the polymer-salt interaction. The interaction of the spectra can be observed by the shifting in the wavenumbers of the functional groups. Fig. 4a illustrates the FTIR spectra of MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3. The interaction between MC and PVA was discussed in our previous work [12]. The vibration observed at 3321 cm−1 in the spectrum of Li0 is attributed to the OH band stretching. This band is shifted to higher wavenumbers as the concentration of LiCF3SO3 increases up to 40 wt.%.

Figure 4: (a) FTIR spectra of MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 and (b) deconvoluted spectra in the range of 970–1100 cm−1

Upon the introduction of LiCF3SO3 into the MC-PVA blend host, the dissociated Li+ ions formed interactions with the OH groups. This interaction caused a change in the vibrational frequencies of the OH bands, leading to the shifting of the OH peak to higher wavenumbers. Comparable finding was reported by Noor et al. [31] after doping PVA with lithium bis(oxalate)borate. Polymer-salt interaction can also be proven from the shifting of C−O stretching and C=C stretching bands which are observed at 1049 and 1732 cm−1 respectively in the spectrum of L0. In the spectra of Li10–Li40, the C−O stretching band is observed to shift to 1026–1028 cm−1. The C=C stretching band is observed to shift to 1727 cm−1 in the spectrum of Li10 and further shifted to 1713 cm−1 in the spectrum of Li40. Table 2 lists the assignments of FTIR bands for MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 complexes.

As reported in [35], a Li+ cation interacts with a CF3SO3−1 anion through the SO3 end. Therefore, the SO−3 band in the range of 970–1100 cm−1 was deconvoluted to determine the percentage of free ions (1031–1033 cm−1), ion pairs (1044–1048 cm−1) and aggregate ions (1056–1059 cm−1). The results are illustrated in Fig. 4b. The peaks at 1029, 1042 and 1052 cm−1 are assigned to free ions, ion pairs and ion aggregates, respectively, of LiCF3SO3 [36].

The area under these peaks was determined to calculate the number density (n), ion mobility (µ) and diffusion coefficient (D) using the equations reported in [36].

where NA is the Avogadro’s number, M is the number of the moles of LiCF3SO3 salt, e is the electron charge, T is the absolute temperature, and k is the Boltzmann constant. These transport parameters as a function of LiCF3SO3 concentration are depicted in Fig. 5. The n increases from 6.97 × 1021 to 2.95 × 1022 cm−3 as the concentration of LiCF3SO3 increases to 40 wt.%. As more LiCF3SO3 was incorporated into the MC-PVA blend, more ions were dissociated from the LiCF3SO3. Similar trend is observed for the µ and D. Doping the polymer blend host has increased the polymer chain flexibility thus enabling a fast ion transport which in turn increases the ion mobility [30].

Figure 5: Transport parameters (a) number density, (b) ion mobility and (c) diffusion coefficient of the ions

The XRD diffractogram of LiCF3SO3, pure PVA, pure MC, and MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 electrolytes is shown in Fig. 6. In the diffractogram of MC, characteristic peaks of MC are identified at 2θ = 8.4° and 20.5° [37]. A crystalline peak appears at 2θ = 19.4° in the diffractogram of PVA. Crystallinity of MC, PVA and L0 was discussed in [11]. The major crystalline peaks of LiCF3SO3 are observed at 2θ = 16.6°, 19.8° and 22.7°. These crystalline peaks of LiCF3SO3 are not observed in the diffractogram of MC-PVA electrolytes inferring a good dissolution of salt. The addition of LiCF3SO3 into the MC-PVA blend has led to a broader amorphous hump indicating enhanced amorphous region in the electrolyte.

Figure 6: XRD diffraction patterns of LiCF3SO3 salt and MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 complexes

To check the influence of salt concentration on crystallinity, the χc was computed using Eq. (2) and tabulated in Table 3. As the LiCF3SO3 concentration increases the degree of crystallinity decreases with Li40 showing the lowest degree of crystallinity of 19.92%. This result reveals that both the concentration of charge carriers and the amorphous phase enhance simultaneously with the increasing salt content. In addition, the enhanced amorphousness has reduced the energy barriers, allowing greater segmental motion of ions and thereby resulting in higher conductivity [38]. In a report by Amran et al. [18], the potato starch–chitosan blend polymer electrolytes become less amorphous beyond the optimum concentration of LiCF3SO3. In this work, if more than 40 wt.% of salt were added to the MC-PVA matrix, ionic aggregates could form, reducing the number of free ions available for conduction. Free ions typically interact with polymer chains, disrupting their regular packing and thereby suppressing crystallinity. However, when fewer free ions are present, these interactions are weakened, allowing the polymer chains to align more easily and form more ordered, crystalline regions. As a result, the degree of crystallinity increases. These XRD results provide some insights into the increase in conductivity with increasing LiCF3SO3 content up to 40 wt.%.

3.5 Field Scanning Emission Microscopy (FESEM)

FESEM micrographs of the samples are illustrated in Fig. 7. The surface morphology of Li0 is observed to be smooth without any separation phase indicating a homogenous MC-PVA blend. This result shows that MC and PVA are miscible with one another. It is evident that the addition of LiCF3SO3 to the MC-PVA blend has transformed the morphology of the electrolytes into a porous type morphology. The same observation is reported for other MC-PVA blend-based SPE systems [12,39]. In a report by Liang et al. [40], porosity of PEO–PMMA–LiClO4 is greatly affected by the concentration of dopant. The authors also reported that the sample with greater porosity obtained higher ionic conductivity as the porous structure of an electrolyte can facilitate the transportation of charge carriers. In this work, it can be inferred that the incorporation of LiCF3SO3 into the polymer blend host promotes the formation of pores, providing channels for ionic conduction, thus increasing ionic mobility [12].

Figure 7: FESEM morphology of MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 electrolytes at 1k × magnification

MC-PVA-LiCF3SO3 film electrolytes were successfully prepared using the solvent casting technique. FTIR analysis proved the occurrence of complexation between the MC-PVA blend and LiCF3SO3. By deconvoluting the FTIR spectra in the wavenumber range of 970–1100 cm−1, transport properties of the electrolytes were investigated. As the concentration of LiCF3SO3 increased, the number density (n) of ions increased from 6.97 × 1021 (Li10) to 2.95 × 1022 cm−3 (Li40). A similar trend was observed for the mobility (µ) and diffusivity (D) of ions. From XRD studies, it was found that the increase in LiCF3SO3 content resulted in a decrease in the degree of crystallinity. Li40 has the lowest degree of crystallinity of 19.92%. The highest room temperature conductivity of 5.42 × 10−6 S cm−1 was achieved with the introduction of 40 wt.% LiCF3SO3. The conductivity result was in good agreement with the dielectric results. The porosity of the SPEs was influenced by the salt concentration and showed good agreement with the conductivity results. However, although the present work has yielded promising results, there is still room for improvement. As reported in most studies, the ionic conductivity of solid polymer electrolytes should typically be in the range of ~10−4 S cm−1 for energy storage applications. To further enhance conductivity, the MC–PVA–LiCF3SO3 system could be modified with the addition of plasticizers such as ethylene carbonate (EC) and nanofillers like titanium dioxide (TiO2), which can facilitate salt dissociation into free ions. Although this work focuses on room-temperature performance, future work will aim to evaluate the characteristics of the electrolytes at different temperatures as well as thermal and mechanical properties to further assess practical applicability. Additionally, device-level validation will be undertaken to assess the real-world applicability of the developed electrolyte system.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge Universiti Teknologi PETRONAS for the financial support provided through the YUTP-FRG grant (015LC0-631).

Author Contributions: Nurrul Asyiqin Shamsuri: Writing—original draft preparation, formal analysis; Zamil Khairuddin: Methodology, investigation; Muhamad Hafiz Hamsan: Validation, data curation; Norhana Abdul Halim: Conceptualization; Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir: Software, resources; Muhammad Fadhlullah Shukur: Writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Maheshwari T, Tamilarasan K, Selvasekarapandian S, Chitra R, Kiruthika S. Investigation of blend biopolymer electrolytes based on Dextran-PVA with ammonium thiocyanate. J Solid State Electrochem. 2021;25:755–65. doi:10.1007/s10008-020-04850-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lu T, Zhou Y, Zeng X, Hao S, Wei Q. Study of the ion transport properties of succinonitrile plasticized poly(vinylidene fluoride)-based solid polymer electrolytes. Mater Lett. 2024;360:135912. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2024.135912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Mohan S, Bhajantri RF, Nagabushana BM. Functional group engineered green hydroxypropyl methylcellulose—chitosan bio-polymer nanocomposite electrolyte with TiO2 filler and LiClO4 salt. Solid State Ion. 2025;429:116985. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2025.116985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mallaiah Y, Jeedi VR, Swarnalatha R, Raju A, Reddy SN, Chary AS. Impact of polymer blending on ionic conduction mechanism and dielectric properties of sodium-based PEO-PVdF solid polymer electrolyte systems. J Phys Chem Solids. 2021;155:110096. doi:10.21203/rs.3.rs-239135/v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Gambino F, Gastaldi M, Jouhara A, Malburet A, Galliano S, Cavallini N, et al. Formulating PEO-polycarbonate blends as solid polymer electrolytes by solvent-free extrusion. J Power Sources Adv. 2024;30:100160. doi:10.1016/j.powera.2024.100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Liu L, Wang F, Zhang J, Jiang W, Yang F, Hu M, et al. Boosting ion conduction in polymer blends by tailoring polymer phase separation. J Power Sources. 2023;569:233005. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2023.233005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Nadirah BN, Ong CC, Saheed MSM, Yusof YM, Shukur MF. Structural and conductivity studies of polyacrylonitrile/methylcellulose blend based electrolytes embedded with lithium iodide. Int J Hydrogen Energy. 2020;45:19590–600. doi:10.1016/j.ijhydene.2020.05.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang J, Li X, Wang X, Su Y, Liu G, Yu W, et al. A study on PVDF-PEO-Li7La2.5Ce0.5Zr1.625Bi0.3O12 solid electrolyte with high ionic conductivity and its application in solid-state batteries. Next Mater. 2025;7:100360. doi:10.1016/j.nxmate.2024.100360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Oun AA, Shin GH, Rhim JW, Kim JT. Recent advances in polyvinyl alcohol-based composite films and their applications in food packaging. Food Packag Shelf Life. 2022;34:100991. doi:10.1016/j.fpsl.2022.100991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Gupta B, Mishra V, Gharat S, Momin M, Omri A. Cellulosic polymers for enhancing drug bioavailability in ocular drug delivery systems. Pharmaceuticals. 2021;14:1201. doi:10.3390/ph14111201. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Shamsuri NA, Zaine SNA, Yusof YM, Shukur MF. Ion conducting methylcellulose-polyvinyl alcohol blend based electrolytes incorporated with ammonium thiocyanate for electric double layer capacitor application. J Appl Polym Sci. 2022;139:52076. doi:10.1002/app.52076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Shamsuri NA, Zaine SNA, Yusof YM, Yahya WZN, Shukur MF. Effect of ammonium thiocyanate on ionic conductivity and thermal properties of polyvinyl alcohol–methylcellulose–based polymer electrolytes. Ionics. 2020;26:6083–93. doi:10.1007/s11581-020-03753-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shamsuri NA, Chia JJ, Hamsan MH, Kadir MFZ, Shukur MF. Effect of azanium iodide on the conductive properties of poly(ethenol)-methyl ether of cellulose blend based electrolytes. Sains Malays. 2024;53:3329. [Google Scholar]

14. Wong CC, Yap AY, Liew CW. The effect of ionic liquid on the development of poly(vinyl alcohol) (PVA)-based ion conductors for electric double layer capacitors application. J Electroanal Chem. 2021;886:115146. doi:10.1016/j.jelechem.2021.115146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Simoes MC, Hughes KJ, Ingham DB, Ma L, Pourkashania M. Estimation of the thermochemical radii and ionic volumes of complex ions. Inorg Chem. 2017;56:7566–73. doi:10.1021/acs.inorgchem.7b01205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Noor ISM, Majid SR, Arof AK, Djurado D, Neto SC, Pawlicka A. Characteristics of gellan gum–LiCF3SO3 polymer electrolytes. Solid State Ion. 2012;225:649. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2012.03.019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Wang J, Zhao Z, Song S, Ma, Liu R. High performance poly(vinyl alcohol)-based Li-ion conducting gel polymer electrolyte films for electric double-layer capacitors. Polymers. 2018;10:1179. doi:10.3390/polym10111179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Amran NNA, Manan NSA, Kadir MFZ. The effect of LiCF3SO3 on the complexation with potato starch-chitosan blend polymer electrolytes. Ionics. 2016;22:1647. doi:10.1007/s11581-016-1684-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Muhammad AG, Nazir S, Rawat N, Hamzah FM, Diantoro M, Arkhipova EA, et al. Electrochemical application of poly(vinylidene fluoride-co-hexafluoropropylene) incorporated with trihexyl(tetradecyl)phosphonium dicyanamide and polyether-derived carbon. Ionic. 2025;31:4383–92. doi:10.1007/s11581-025-06172-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Shetty SK, Hegde IS, Ravindrachary V, Sanjeev G, Bhajantri RF, Masti SP. Dielectric relaxations and ion transport study of NaCMC: NaNO3 solid polymer electrolyte films. Ionics. 2021;27(6):2509–25. doi:10.1007/s11581-021-04023-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cyriac V, Ismayil, Mishra K, Sudhakar YN, Rojudi ZE, Masti SP, et al. Suitability of NaI complexed sodium alginate-polyvinyl alcohol biodegradable polymer blend electrolytes for electrochemical device applications: insights into dielectric relaxations and scaling studies. Solid State Ion. 2024;411:116578. doi:10.1016/j.ssi.2024.116578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Docker A, Tse YC, Tay HM, Zhang Z, Beer PD. Ammonium halide selective ion pair recognition and extraction with a chalcogen bonding heteroditopic receptor. Dalton Trans. 2024;53:11141–6. doi:10.1039/d4dt01376j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Sohaimy MIH, Isa MIN. Proton-conducting biopolymer electrolytes based on carboxymethyl cellulose doped with ammonium formate. Polymers. 2022;12:3019. doi:10.3390/polym14153019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Aziz SB, Abdullah OG, Rasheed MA, Ahmed HM. Effect of high salt concentration (HSC) on structural, morphological, and electrical characteristics of chitosan based solid polymer electrolytes. Polymers. 2017;9:187. doi:10.3390/polym9060187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Yulianti E, Sudaryanto, Deswita, Wahyudianingsih. Electrical properties study of solid polymer electrolyte based on polycaprolactone/LiCF3SO3 added plasticizer. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2020;924:012034. [Google Scholar]

26. Naiwi TSRT, Aung MM, Rayung M, Ahmad A, Chai KL, Fui MLW, et al. Dielectric and ionic transport properties of bio-based polyurethane acrylate solid polymer electrolyte for application in electrochemical devices. Polym Test. 2022;106:107459. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2021.107459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Woo HJ, Majid SR, Arof AK. Dielectric properties and morphology of polymer electrolyte based on poly(ε-caprolactone) and ammonium thiocyanate. Mater Chem Phyis. 2012;134:755–61. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.03.064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ramly K, Isa MIN, Khiar ASA. Conductivity and dielectric behaviour studies of starch/PEO+x wt-%NH4NO3 polymer electrolyte. Mater Res Innov. 2011;15:S82–5. doi:10.1179/143307511x1303189074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Bashiri P, Rao TP, Nazri GA, Naik R, Naik VM. Ionic conductivity of hybrid composite solid polymer electrolytes of PEOnLiClO4-Cubic Li7La3Zr2O12 films. Processes. 2021;9:2090. doi:10.3390/pr9112090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Hama PO, Brza MA, Tahir HB, Aziz SB, Al-Asbahi BA, Ahmed AAA. Simulated EIS and Trukhan model to study the ion transport parameters associated with Li+ ion dynamics in CS based polymer blends inserted with lithium nitrate salt. Results Phys. 2023;46:106262. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2023.106262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Noor IS, Majid SR, Arof AK. Poly(vinyl alcohol)–LiBOB complexes for lithium–air cells. Electrochim Acta. 2013;102:149–60. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2013.04.010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Khanmirzaei MH, Ramesh S. Ionic transport and FTIR properties of lithium iodide doped biodegradable rice starch based polymer electrolytes. Int J Electrochem Sci. 2013;8:9977–91. doi:10.1016/s1452-3981(23)13026-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Abdullah OG, Hanna RR, Ahmed HT, Mohamad AH, Saleem SA, Saeed MAM. Conductivity and dielectric properties of lithium-ion biopolymer blend electrolyte based film. Results Phys. 2021;24:1–7. doi:10.1016/j.rinp.2021.104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Nayak P, Sudhakar YN, De S, Ismayil, Shetty SK, Cyriac V. Modifying the microstructure of chitosan/methylcellulose polymer blend via magnesium nitrate doping to enhance its ionic conductivity for energy storage application. Cellulose. 2023;30:4401–19. doi:10.1007/s10570-023-05114-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Huang W, Frech R. Dependence of ionic association on polymer chain length in poly(ethylene oxide)-lithium triflate complexes. Polymer. 1994;35:235–42. doi:10.1016/0032-3861(94)90684-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Noor IM. Determination of charge carrier transport properties of gellan gum–lithium triflate solid polymer electrolyte from vibrational spectroscopy. High Perform Polym. 2020;32:168–74. doi:10.1177/0954008319890016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Layek RK, Ramakrishnan KR, Sarlin E, Orell O, Kanerva M, Vuorinen J, et al. Layered structure graphene oxide/methylcellulose composites with enhanced mechanical and gas barrier properties. J Mater Chem A. 2018;6:13203–14. doi:10.1039/c8ta03651a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Gopinath G, Shanmugaraj P, Sasikumar M, Shadap M, Banu A, Ayyasamy S. Cellulose acetate-based magnesium ion conducting plasticized polymer membranes for EDLC application: advancement in biopolymer energy storage devices. Appl Surf Sci Adv. 2023;18:100498. doi:10.1016/j.apsadv.2023.100498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Rojudi ZE, Shamsuri NA, Bashir AA, Hamsan MH, Aziz MF, Azam MA, et al. Effect of ethylene carbonate addition on ion aggregates, ion pairs and free ions of polyvinyl alcohol-methylcellulose host: selection of polymer electrolyte for possible energy devices application. J Polym Res. 2022;29:248. doi:10.1007/s10965-022-03098-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Liang B, Jiang Q, Tang S, Li S, Chen X. Porous polymer electrolytes with high ionic conductivity and good mechanical property for rechargeable batteries. J Power Sources. 2016;307:320–8. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2015.12.127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools