Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Prediction and Validation of Mechanical Properties of Areca catechu/Tamarindus indica Fruit Fiber with Nano Coconut Shell Powder Reinforced Hybrid Composites

1 Department of Information Technology, Sri Ramakrishna Engineering College, Coimbatore, 641022, Tamil Nadu, India

2 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Sri Ramakrishna Engineering College, Coimbatore, 641022, Tamil Nadu, India

3 Department of Computer Science and Engineering, L & T EduTech (A Unit of Larsen and Toubro Limited), Manapakkam, Chennai, 600089, Tamil Nadu, India

4 Institute of Mechanical Engineering, Saveetha School of Engineering, Saveetha Institute of Medical and Technical Sciences, Saveetha University, Chennai, 602105, Tamil Nadu, India

* Corresponding Author: Joseph Selvi Binoj. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 773-794. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.069295

Received 19 June 2025; Accepted 13 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Machine learning models can predict material properties quickly and accurately at a low computational cost. This study generated novel hybridized nanocomposites with unsaturated polyester resin as the matrix and Areca fruit husk fiber (AFHF), tamarind fruit fiber (TFF), and nano-sized coconut shell powder (NCSP). It is challenging to determine the optimal proportion of raw materials in this composite to achieve maximum mechanical properties. This task was accomplished with the help of ML techniques in this study. The tensile strength of the hybridized nanocomposite was increased by 134.06% compared to the neat unsaturated polyester resin at a 10:5:2 wt.% ratio, AFHF:TFF:NCSP. The stiffness and impact behavior of hybridized nanocomposites were similar. The scanning electron microscope showed homogeneous reinforcement and nanofiller distribution in the matrix. However, the hybridized nanocomposite with a 20:5:0 wt.% combination ratio had the highest strain at break of 5.98%, AFHF:TFF:NCSP. The effectiveness of recurrent neural networks and recurrent neural networks with Levenberg’s algorithm was assessed using R2, mean absolute errors, and minimum squared errors. Tensile and impact strength of hybridized nanocomposites were well predicted by the recurrent neural network with Levenberg’s model with 2 and 3 hidden layers, 80 neurons and 80 neurons, respectively. A recurrent neural network model with 4 hidden layers, 60 neurons, and 2 hidden layers, 100 neurons predicted hybridized nanocomposites’ Young’s modulus and elongation at break with maximum R2 values. The mean absolute errors and minimum squared errors were evaluated to ensure the reliability of the machine learning algorithms. The models optimize hybridized nanocomposites’ mechanical properties, saving time and money during experimental characterization.Keywords

The quest for sustainable materials has gained unprecedented momentum in recent years, driven by environmental concerns and the urgent need to reduce reliance on non-renewable resources [1]. Among the innovative solutions being explored, natural fiber reinforced polymer composites stand out due to their potential to combine excellent mechanical properties with environmental friendliness. These composites typically consist of a polymer matrix reinforced with natural fibers, such as jute, hemp, flax, or bamboo, which offer benefits like low density, biodegradability, and enhanced tensile strength [2,3]. As industries seek to adopt greener alternatives, optimizing the mechanical properties of these materials becomes essential to ensure their viability in various applications, including automotive, construction, and consumer goods [4]. Natural fibers are not only lightweight but also exhibit good specific strength, making them suitable for reinforcing polymers. However, the mechanical performance of natural fiber reinforced composites can be highly variable, depending on factors such as fiber type, orientation, length, and the nature of the polymer matrix used. Additionally, the interface between the fiber and matrix plays a crucial role in determining the overall performance of the composite [5]. Therefore, understanding and optimizing these parameters is vital for developing materials that meet the demanding specifications of modern engineering applications.

Recent advancements in nanotechnology have further expanded the potential of polymer composites by enabling the incorporation of nanomaterials, such as nanoclays, carbon nanotubes, and graphene, into the polymer matrix [6]. These nanofillers can significantly enhance the mechanical properties, thermal stability, and barrier performance of composites. By creating hybrid composites that combine natural fibers and nanofillers, researchers can achieve a synergistic effect, resulting in materials with superior properties compared to traditional composites [7]. This approach not only improves performance but also adds value by making use of renewable resources alongside cutting-edge nanotechnology. The optimization of the mechanical properties of these hybrid sustainable polymer nanocomposites presents a complex challenge that requires a thorough understanding of the interactions between different components. Traditionally, experimental methods have been employed to study these interactions and optimize material properties [8]. Techniques such as tensile testing, flexural testing, and impact testing provide valuable data on the mechanical performance of the composites. However, these methods can be time-consuming and resource-intensive, especially when exploring a wide range of variables and their interactions.

In response to these challenges, machine learning (ML) techniques have emerged as powerful tools for materials optimization. By leveraging large datasets, machine learning can identify patterns and correlations that may not be immediately apparent through traditional experimental approaches [9]. For example, ML algorithms can analyze the influence of various factors such as fiber content, type of nanofiller, and processing conditions on the mechanical properties of the composites. This data-driven approach allows researchers to develop predictive models that can guide the design of new materials with enhanced performance characteristics. Furthermore, machine learning can facilitate the optimization process by predicting the optimal combination of parameters needed to achieve desired mechanical properties, thereby reducing the time and resources required for experimental validation [10]. The integration of experimental and machine learning techniques creates a comprehensive framework for the optimization of natural fiber reinforced hybrid sustainable polymer nanocomposites [11]. This hybrid approach enables researchers to systematically investigate the effects of different variables, validate findings through experiments, and refine predictive models based on empirical data. By combining the strengths of both methodologies, it is possible to accelerate the development of high-performance, sustainable materials that meet industry demands.

Additionally, the use of machine learning in materials science opens up new avenues for innovation. For instance, unsupervised learning techniques can reveal insights into material behavior and performance that might not be captured by traditional experimental methods [12]. Similarly, reinforcement learning can be utilized to optimize processing parameters in real-time, adapting to changes in material properties as they occur during manufacturing. These advancements not only enhance the understanding of composite materials but also pave the way for the creation of smart materials that can respond to environmental stimuli. Studies were also carried out by the researchers on optimizing the fiber orientation of the reinforcements in the matrix by directing the print routes regionally in the additive manufacturing process [13]. The significance of this research lies in its potential to contribute to the development of sustainable materials that align with global efforts to reduce environmental impact.

Champa-Bujaico et al. (2024) optimized the mechanical properties of multiwalled carbon nanotubes, tungsten disulfide nanosheets, and sepiolite powder reinforced nano composites using machine learning techniques [14]. They have used Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), decision tree (DT), and Random Forest (RF) to arrive at optimal solutions from the existing experimental design. The RNN model with 3 hidden layers and 50 neurons in each layer was able to obtain the highest correlation of 0.92 for test sets. The mean square error of 0.13 and the mean absolute error of 0.31 were obtained for the elongation at break parameter through RF. Imoisili et al. (2024) optimized the mechanical properties of multiwalled carbon nanotubes and potassium permanganate and acetone modified plantain fiber reinforced nano composites using machine learning techniques [15]. They have used an Artificial Neural Network (ANN) to arrive at optimal solutions from the existing experimental design. The ANN model with 1 hidden layer and 5 neurons in the hidden layer was able to obtain the highest correlation of 0.99 for test sets. The ANN model was able to arrive at an optimal tensile strength of 46.156 Mpa, which is much closer to experimental results.

Thanikodi et al. (2024) used a machine learning approach to identify the optimal combination and proportion of fiber and the matrix in polymer composites to maximize their mechanical properties [16]. Local search with a support vector machine approach is followed to identify the optimal combination and proportion of 14 fibers and 4 matrices in polymer composites to achieve maximum mechanical properties. Their optimization process was intended for transportation and medical applications. The local search with the support vector machine approach worked well for the intended applications. Han et al. (2023) used an RF algorithm to optimize the interlaminar toughness properties of carbon nanotube reinforced nano composites [17]. The RF algorithm was able to predict the interlaminar fracture toughness of the nano composites with the highest correlation of 0.916 for test sets. The rankings obtained from the RF algorithm suggest concentrating more on the manufacturing process of the nano composites to improve their interlaminar fracture toughness properties. Table 1 indicates a few similar studies with their inputs, outputs, Ml model used, and their accuracies.

Areca fruit husk fiber (AFHF) and tamarind fruit fiber (TFF) which are agro-wastes from agro industries were used as reinforcement in the unsaturated polyester resin (UPR) matrix composite with nano-sized coconut shell powder (NCSP) as filler material. By optimizing the mechanical properties of natural fiber reinforced hybrid polymer nano composites, this work aims to advance the field of green materials, promoting the use of renewable resources while ensuring high performance and durability. Furthermore, the application of machine learning techniques in this context represents a shift toward more efficient and innovative material design processes, which is crucial in the rapidly evolving landscape of materials engineering [18]. As the demand for sustainable alternatives continues to rise, this research not only addresses pressing environmental concerns but also enhances the understanding of nano composite materials, paving the way for innovative applications across various industries. The integration of traditional experimental methods with modern machine learning techniques offers a powerful approach to developing high-performance materials that are both environmentally friendly and economically viable. The optimization of mechanical properties in natural fiber reinforced hybrid sustainable polymer nano composites through experimental and machine learning techniques holds great promise for the future of materials science. This research, aspires to contribute to a more sustainable future while advancing the boundaries of material science and engineering.

This research employs two regression models—Recurrent Neural Network (RNN), and RNN-Levenberg Marquardt (RNN-LV) to forecast the mechanical properties of hybrid nano composites. These models are popular in scientific investigations due to their strengths in handling non-linear relationships, adaptability, and high accuracy [19]. Additionally, they excel at identifying intricate data patterns. The model’s unique features include excellence in sequential data analysis, transparent decision-making, and ensemble learning advantages. By leveraging these models, this study aims to accurately predict the mechanical properties of hybrid nano composites, capitalizing on their complementary strengths.

Artificial Neural Network

Artificial Neural Networks (ANNs) are computational models inspired by the human brain’s architecture, designed to recognize patterns and solve complex problems [20]. Comprising interconnected nodes or ‘neurons’, ANNs process information in layers: an input layer receives data, hidden layers perform computations, and an output layer delivers results. This structure enables ANNs to learn from data through a process called training, where the network adjusts its internal parameters based on errors in predictions. Various neural network architectures cater to different applications [21]. Feedforward Neural Networks (FNNs) are the simplest form, where data moves in one direction from input to output. Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) excel in image processing, utilizing convolutional layers to detect features. RNNs are designed for sequential data, making them ideal for time series analysis and natural language processing, as they maintain memory of previous inputs. Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) consist of two networks the generator and the discriminator that work against each other to create realistic data. Each architecture offers unique advantages, allowing ANNs to be applied across diverse fields, including computer vision, speech recognition, and financial forecasting.

This research investigates the relationship between fiber reinforcement and filler composition on the mechanical properties of polymer nano composites using machine learning (ML). The input data consists of weight percentages of two fibers and a nanofiller, namely areca fruit husk fiber, tamarind fruit fiber and nano-sized coconut shell powder, respectively, while the output data represents specific mechanical properties, including Young’s modulus, tensile strength, elongation at break, and impact strength. Each property is modelled independently. The goal is to develop ML models that predict mechanical properties based on material composition, exploring how variations in fiber reinforcement and nanofiller proportions influence material performance [22]. This study aims to establish accurate relationships and facilitate property prediction for tailored nano-composite design.

This study compares two optimization techniques for RNNs, namely Stochastic Gradient Descent (SGD) and Levenberg-Marquardt (RNN-LV). The main advantage of the SGD model is its scalability and flexibility with learning rate schedules. But takes more iterations to converge and depends on tuning of hyperparameters. On the other hand, the RNN-LV model has faster convergence and is stable for small networks, whereas it requires large memory with limited library support. SGD employs standard backpropagation to compute gradients and adjust network parameters during training. In contrast, RNN-LV utilizes the Gauss-Newton technique to minimize the objective function error, commonly applied in nonlinear regression. Notably, backpropagation remains integral to RNN-LV, calculating local gradients. The comparison aims to assess the accuracy and training efficiency of each approach in predicting material properties [23]. By evaluating these optimization methods, we seek to identify the most suitable training algorithm for our research objectives and gain insight into how they impact results. This analysis will inform the selection of an optimal RNN configuration, ultimately enhancing predictive performance and advancing understanding of complex property relationships in polymer nanocomposites. The findings will provide valuable implications for future RNN applications.

FNN architecture is employed to predict nano-composite properties based on material composition. The network consists of an input layer with three neurons (representing the input variables), variable hidden layers, and a single-neuron output layer. The hidden layer utilizes the ReLU activation function, a popular nonlinear function in artificial neural networks [24]. Training parameters were initialized with a learning rate of 0.02 for RNN and 0.08 for RNN-LV, and a maximum of 1200 iterations. These settings can be adjusted based on the problem and network architecture. The iteration limit prevents overfitting and controls training duration. Optimizing model parameters requires careful tuning, often involving trial-and-error for each specific problem. By fine-tuning the parameters like hidden layer configuration, learning rate adjustment, and iteration limit, the model can effectively capture complex relationships between chemical composition and nano composite properties, ensuring accurate predictions and robust performance [25]. The dataset is split into training and test sets for model evaluation. Utilizing Python 3.9.6 and TensorFlow 2.10.0, the neural network is built with Keras 2.10.0 via the TensorFlow functional API, ideal for regression tasks. This setup enables efficient development, training, and deployment of complex neural networks.

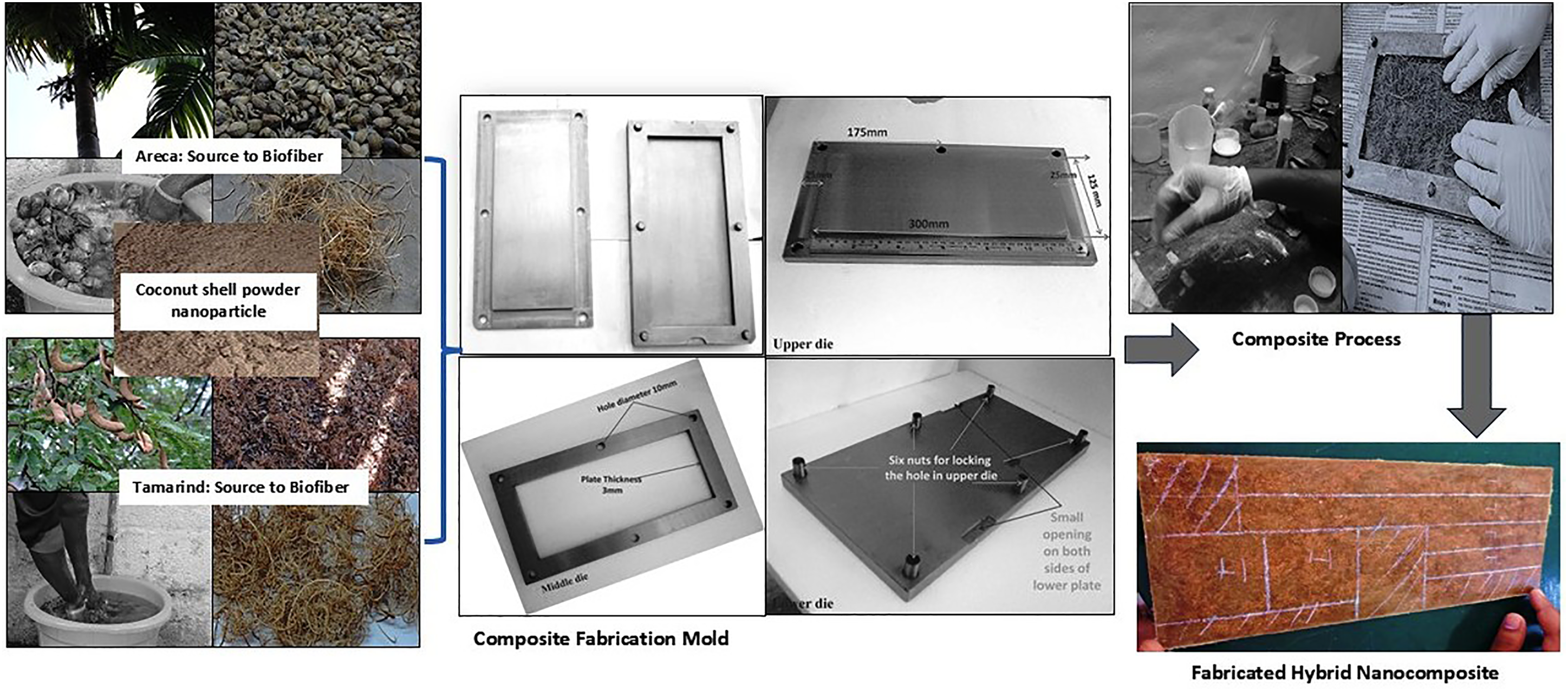

The areca fruit husks and tamarind fruit wastes were collected from the dump yards of tobacco product manufacturers and food processing companies, respectively, in the outskirts of Coimbatore, India. The collected agro-wastes were soaked in water for 7 days. Then they were repeatedly washed in running water, exposed to sunlight for 3 days and combed to obtain TFFs and AFHFs. An NCSP of size ranging from 200 to 300 nm was obtained from M/s Coco Starch Pvt Ltd., Pollachi, India. M/s. Raja Traders Pvt Ltd., Tirunelveli, India supplied UPR, methyl ethyl ketone peroxide (MEKP) and cobalt naphthenate (CN). The chemicals procured were of analytical grade and used as such without any further purification process.

3.2 Nano Composite Fabrication

A 300 × 150 × 3 mm3 mold was used to create the nano composite specimens as shown in Fig. 1. The fibers were arranged in the mold at random orientation. To create a solid nano composite sample with NCSP as a filler substance, the matrix solution comprising a catalyst and accelerator was subsequently spread over the fibers. The matrix solution consisting of MEKP, CN, and UPR in the ratio 1:1:98 was combined with the NCSP employed as filler [26]. These components serve as a catalyst, accelerator, and resin, respectively. Following the elimination of air pockets using a grooved roller, the mold is covered and allowed to cure for 24 h at an applied hydraulic pressure of about 400 kN [27]. Lastly, several tests are conducted on the resized sustainable hybrid nano composite specimens with NCSP filler made as indicated in Table 2, following the L33 array in compliance with ASTM guidelines.

Figure 1: Schematic diagram showcasing the fabrication of hybridized nanocomposites

Tensile test was conducted on the resized nano composite specimens as per ASTM D3039 standards [28]. Universal Testing Machine (H50KL), M/s Tinius Olsen Pvt Ltd., Horsham, PA, USA, was used to apply the tensile loads on the nano composite specimens at a crosshead speed of 1 mm/min at 28°C. Charpy impact test was conducted as per ASTM D256-10 standard on the nano composite specimens using Charpy impact tester (HIT450P), M/s Zwick Roell Pvt Ltd., Chennai, India [29]. An impact tester with a sensitivity of −4.019 and a time delay of 1000 s was used for the same. The specimen is placed within the jaws, and by moving the hammer to a distance of 0.1 m, an impact equal to 4.5 J is applied to the sample to cause an impact on the sample being tested. Meanwhile, the response to load-time data was recorded using software. To minimize errors, the trials were conducted five times in each scenario. A Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) (JSM-IT710HR), M/s JEOL Pvt Ltd., Tokyo, Japan was used to examine the broken tensile-tested nano composites to identify any patterns of tensile failure [30]. The experiments were conducted using platinum-coated samples at a 10 kV electron source voltage to prevent charge aggregation.

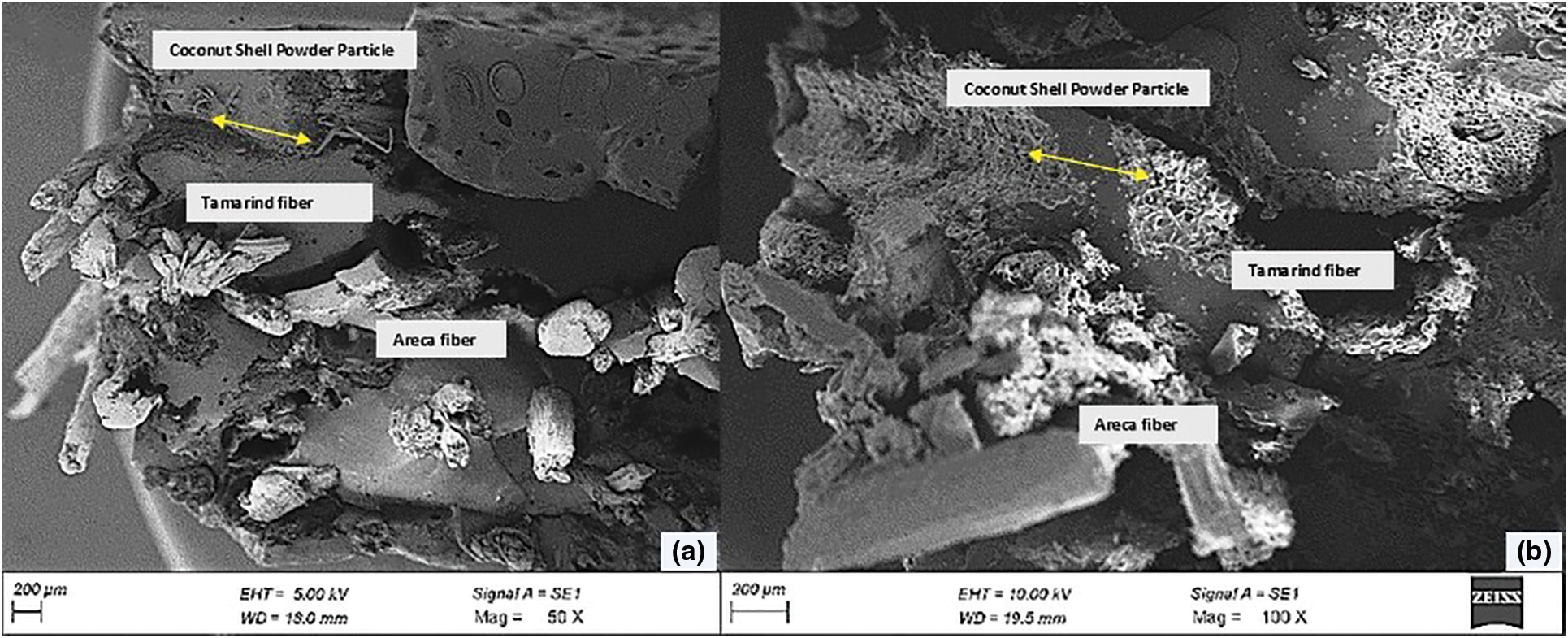

The SEM images of the tensile failure cross-section of the hybrid nano composite sample S31 with 10 wt.% TFF, 10 wt.% AFHF and 1 wt.% NCSP at different magnifications is shown in Fig. 2. The SEM image reveals the 3D form of the presence of TFF, AFHF, and dispersed NCSP in the UPR. The observations show that both the fibers TFF and AFHF were well intercalated within the hybrid nano composite [31]. A few NCSP clusters were also noticed in the SEM image of higher magnification in the tensile failure cross-section of the hybrid nano composite sample S31. On the other hand, TFF and AFHF were well distributed and compactly packed, leading to a denser hybrid nano composite with enhanced mechanical characteristics. The presence of NCSP further enhanced the interaction between the TFF, AFHF, and UPR, leading to fewer matrix cracks, voids, and fiber pullouts [32]. Also, more fiber breakages were noticed, which ensures better fiber matrix bonding in the hybrid nano composites. Moreover, additional interactions like polar and hydrophobic ones may help create a reinforcement structure that is firmly bonded to the substrate.

Figure 2: SEM images at various magnifications of the tensile failure cross-section of the hybrid nano composite sample S31 with 10 wt.% TFF, 10 wt.% AFHF and 1 wt.% NCSP

4.2 Mechanical Characteristics by Experimentation

Table 2 presents the mechanical characteristics of the hybrid nano composites as per the L33 scheme to predict their mechanical properties. The neat UPR has a tensile strength of 37.31 MPa, which is enhanced by 130.81% and 103.64% on reinforcing with 20 wt.% of AFHF and TFF, respectively. This is due to the even distribution of AFHFs and TFFs in the respective composites and better wetting of AFHFs and TFFs by the UPR [33]. This helps in transferring the stress from the UPR to the AFHFs and TFFs when the corresponding composites were subjected to tensile loads. Further, increasing the wt.% of fiber in the composite started deteriorating its tensile characteristics due to the improper wetting of fibers by the UPR. The addition of NCSP in the neat UPR also enhanced the tensile characteristics of the nano composites, but the increase in tensile strength is limited to 30.2% due to the lesser wt.% of NCSP filler addition. The reason for restricting the wt.% of NCSP filler is that increasing the wt.% of filler leads to particle agglomeration and results in deterioration of tensile characteristics.

The binary hybrid composites with AFHFs reinforcement material and NCSP as filler material exhibited a maximum tensile strength of 91.5 MPa. The obtained tensile strength is higher than that of the TFF and AFHF reinforced composites. The NCSP nanoparticles with higher surface tension improve the interaction between the UPR and AFHFs leading to better tensile characteristics in the composite [34]. The ternary hybrid nano composites with TFF and AFHF as reinforcement material and NCSP as filler material possess tensile strength of 92.07 MPa, which is slightly higher than the composites reinforced with AFHF and NCSP filler material. This is due to the inherent mechanical characteristics of the AFHF reinforcement and NCSP filler in the hybrid nano composite. The young’s modulus of the hybrid nano composites varied proportionately to their tensile strength [35]. The observations on the property of young’s modulus of the hybrid nano composites reveal that the young’s modulus increased with an increase in tensile strength and decreased with a decrease in tensile strength. The highest observed young’s modulus is 1.8 GPa for the hybrid nano composite with 20 wt.% AFHF as reinforcement material and 1 wt.% NCSP as filler material.

The strain at break value of the hybrid composites increased with AFHF and TFF reinforcement in the composite compared to neat UPR, whereas it decreased for composites reinforced with NCSP alone. The highest strain at break value noted is 5.88% for the composite with 25 wt.% TFF reinforcement material. On the other hand, the lowest strain at break value noted is 1.2% for the composite with 5 wt.% NCSP filler material. The incorporation of fibers like AFHF and TFF in UPR for the formation of composites exhibits better load transfer characteristics between the fibers and the matrix with fibers as the major load-carrying member leading to more strain at break values [36]. The incorporation of NCSP filler material alone in UPR creates discontinuities in the matrix and reduces the composites strain at break values.

The impact characteristics of the hybrid nano composites were found to improve with the reinforcement of AFHF, TFF reinforcement and NCSP filler material individually and in combination compared to the neat UPR. The highest impact strength of 7.6 J/cm2 is recorded for the ternary composite with 20 wt.% AFHF as reinforcement material and 1 wt.% NCSP as filler material. This is owing to the fact that the reinforcement of fibers like AFHF in UPR improves the polymer composites’ elastic nature and shock-absorbing characteristics by taking up the loads. The addition of filler like NCSP further improves the interaction between the AFHF and UPR in the polymer composite, leading to better load transfer characteristics in the composite [37]. This prevents the formation and propagation of cracks in the polymer composites when subjected to impact loads. The lesser impact strength observed for the polymer composites with NCSP filler reinforcement alone is owing to the discontinuities in the matrix caused by the NCSP filler, which is susceptible to crack formation and propagation when subjected to impact loads. In short, the right combination of reinforcement and filler material at optimum wt.% results in better mechanical characteristics.

4.3 Prediction of Mechanical Characteristics Using ML Techniques

Two distinct models namely RNN and RNN-LV were used in this study to forecast the mechanical characteristics of nanocomposites. The models mentioned above were chosen based on their capacity to manage nonlinear data, extrapolate, spot trends, and increase forecast accuracy. 1/4th of the entire dataset was put aside for testing, and 3/4th was used for training [37]. Finding the ideal hyperparameter setup is essential throughout the training phase. These hyperparameters, which are preset values chosen prior to the model’s execution in the context of neural networks, significantly affect the effectiveness of the model. Key tuning parameters for RNNs and RNN-LV play a crucial role in configuring the network architecture and training process, ultimately affecting the model’s performance and accuracy [38]. The number of hidden layers determines the network’s depth. The number of neurons in each hidden layer impacts the network’s complexity and learning capacity at each level. Learning rate that regulates the weight update rate during training, influencing convergence speed and training stability. An activation function that introduces non-linearity to the model, enabling it to learn complex patterns, and an optimization algorithm that specifies how the model adjusts its weights to minimize the loss function [39]. ReLU is the activation function utilized in each layer of both RNN and RNN-LV, and 0.09 is the learning rate. Setting the ideal number of hidden layers is the initial stage in adjusting the critical hyperparameters. The network’s efficiency is then assessed by altering the number of neurons in these layers.

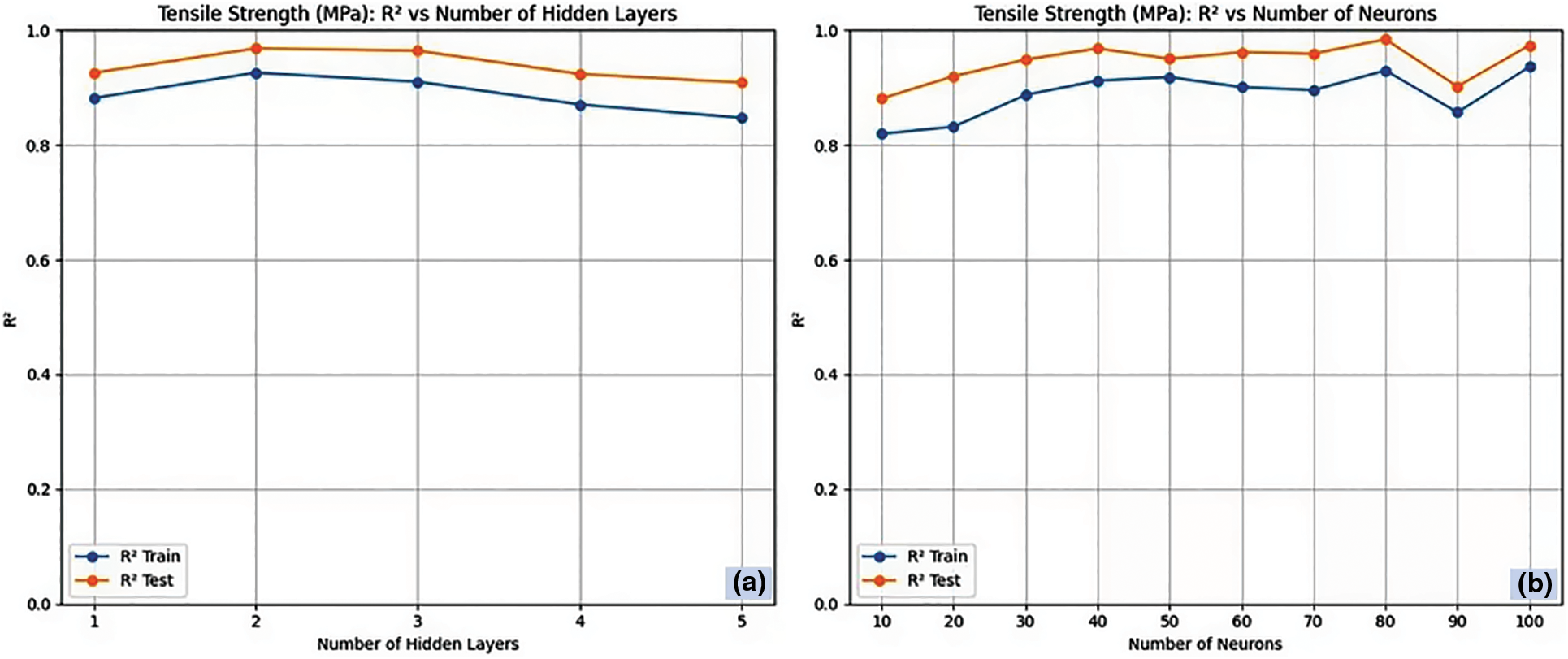

Fig. 3a,b presents the RNN architecture for tensile strength, correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. On predicting the tensile strength with RNN, the R2 tends to increase with an increase in the number of hidden layers in the training data [40]. On observing the test data, the R2 value declines after three hidden layers. This implies that the three hidden layers are sufficient to prevent excessive fitting and preserve the intricacy of the data. Now, the number of hidden layers to predict tensile strength for RNN was fixed as three, and the variation of R2 against the number of neurons was analysed. The R2 value tends to increase with an increase in the number of neurons in the training data, whereas the maximum R2 value of 0.979 and 0.867 is obtained for 80 neurons in the test and training data, respectively. Further increases in the number of neurons tend to excessively fit the test data leading to poor performance. Fig. 4a,b presents the RNN-LV architecture for tensile strength correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. In the case of RNN-LV, the R2 value increases with an increase in the number of hidden layers and neurons in the training data [41]. On the other hand, a maximum R2 value of 0.915 and 0.953 is obtained for two hidden layers and 80 neurons for test and training data, respectively. Performance declines after this, following a pattern akin to the RNN model’s previously mentioned trend.

Figure 3: RNN architecture for tensile strength (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

Figure 4: RNN-LV architecture for tensile strength (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

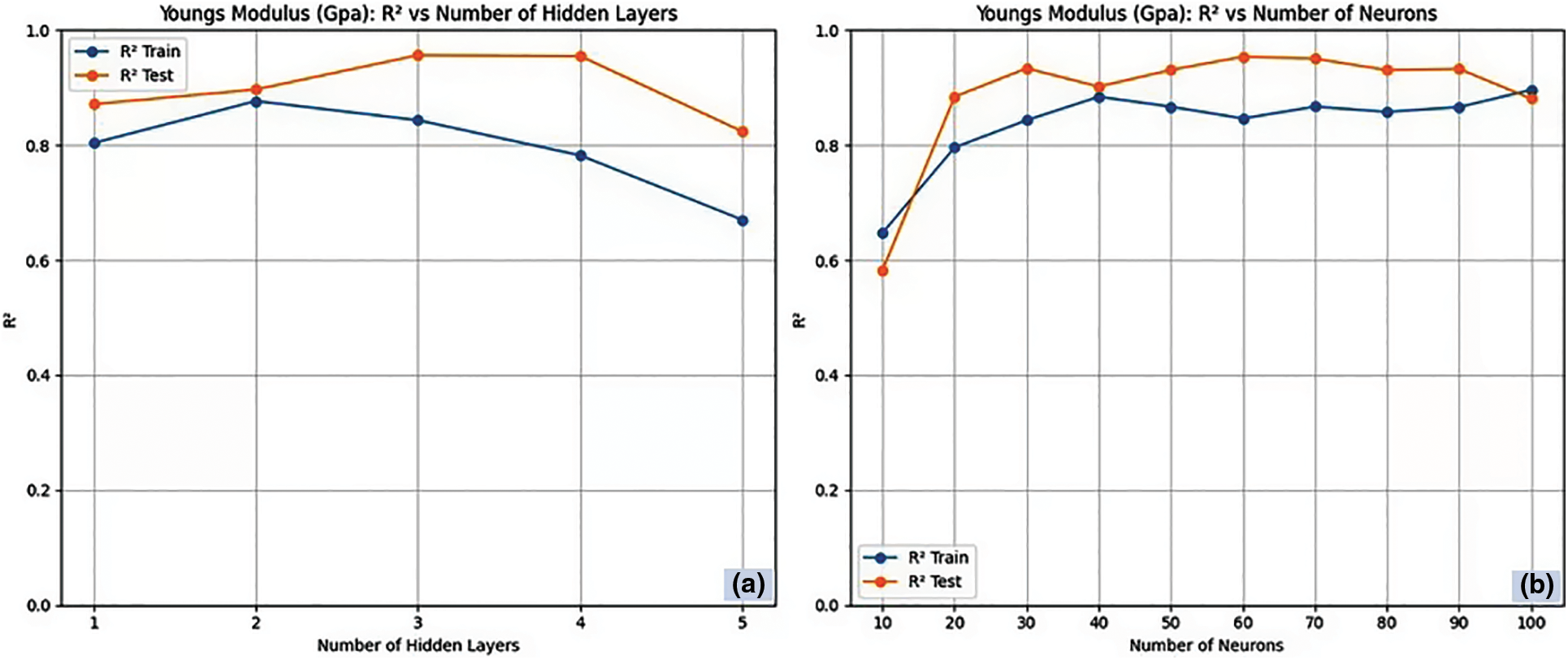

Fig. 5a,b presents the RNN architecture for Young’s modulus correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. On observing the training data set of young’s moduli, the R2 value rises with the addition of the number of hidden layers. This indicates that as more hidden layers are included, the model will be able to adapt to the training data and identify increasingly intricate patterns [42]. The observations on test data of Young’s moduli reveal a spike in R2 value at four hidden layers, showcasing more universality by recognizing patterns that pertain to both fresh and training data. Remarkably, the RNN’s effectiveness on test data declines with the addition of a fourth hidden layer, indicating that the model gets overly sophisticated and starts to excessively fit the training data, impairing its universality [43]. Now, the number of hidden layers to predict Young’s modulus for RNN was fixed as four, and the variation of R2 against the number of neurons was analysed. The R2 value tends to increase with an increase in the number of neurons in the training data, whereas the maximum R2 value of 0.941 and 0.889 is obtained for 60 neurons in the test and training data, respectively. Further increases in the number of neurons tend to excessively fit the test data, leading to poor performance.

Figure 5: RNN architecture for Young’s modulus. (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

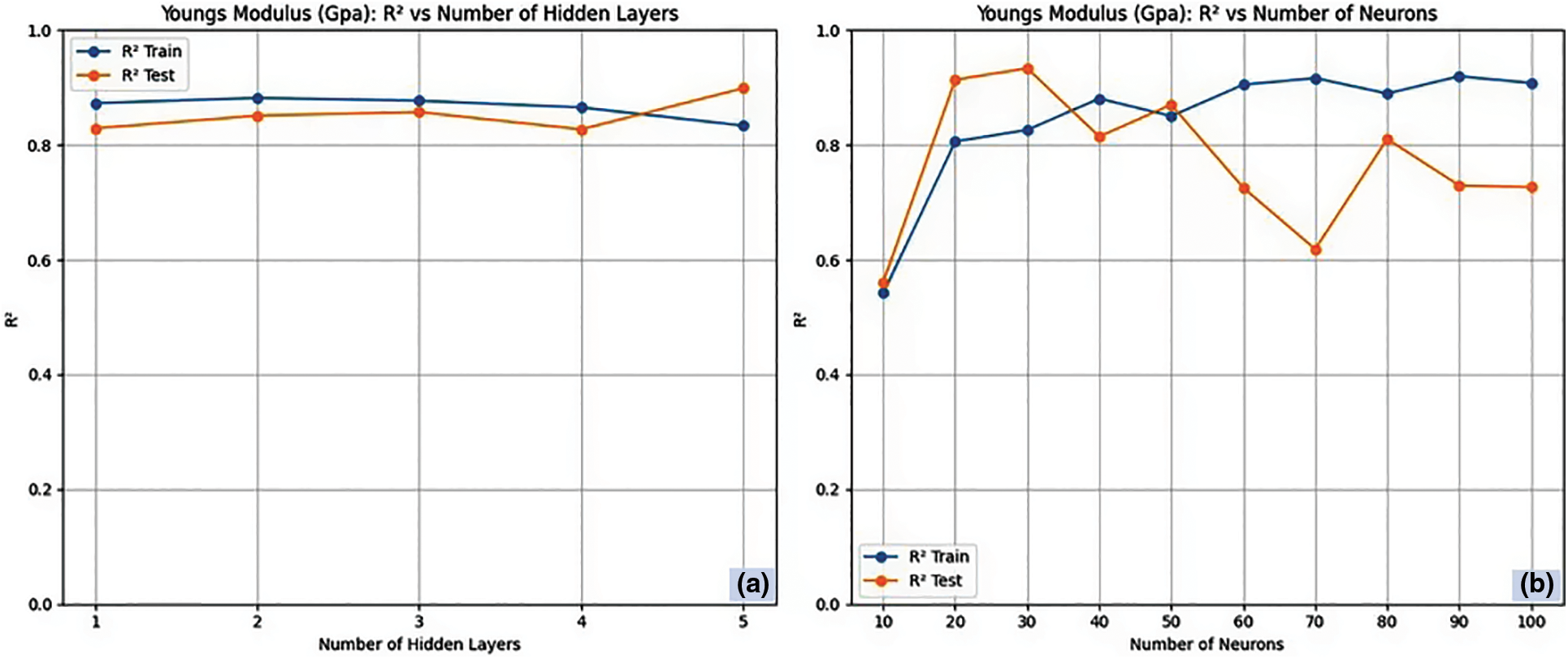

Fig. 6a,b presents the RNN-LV architecture for young’s modulus correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. In the case of RNN-LV, the more hidden layers and neurons there are in the training set, the higher the R2 value [44]. In contrast, three hidden layers and 90 neurons yield maximum R2 values of 0.927 and 0.895 for test and training data, respectively. After this, performance starts to deteriorate to the previously described trend of the RNN-LV model.

Figure 6: RNN-LV architecture for Young’s modulus. (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

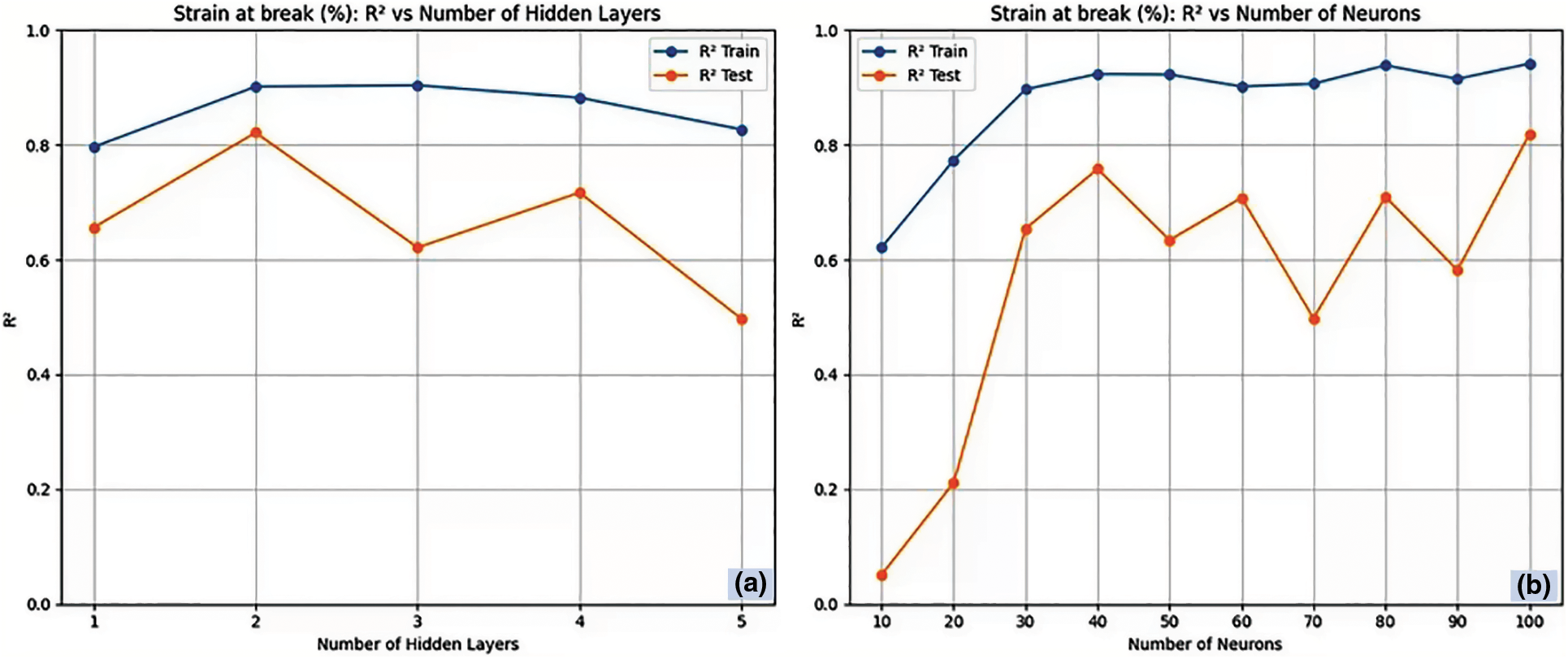

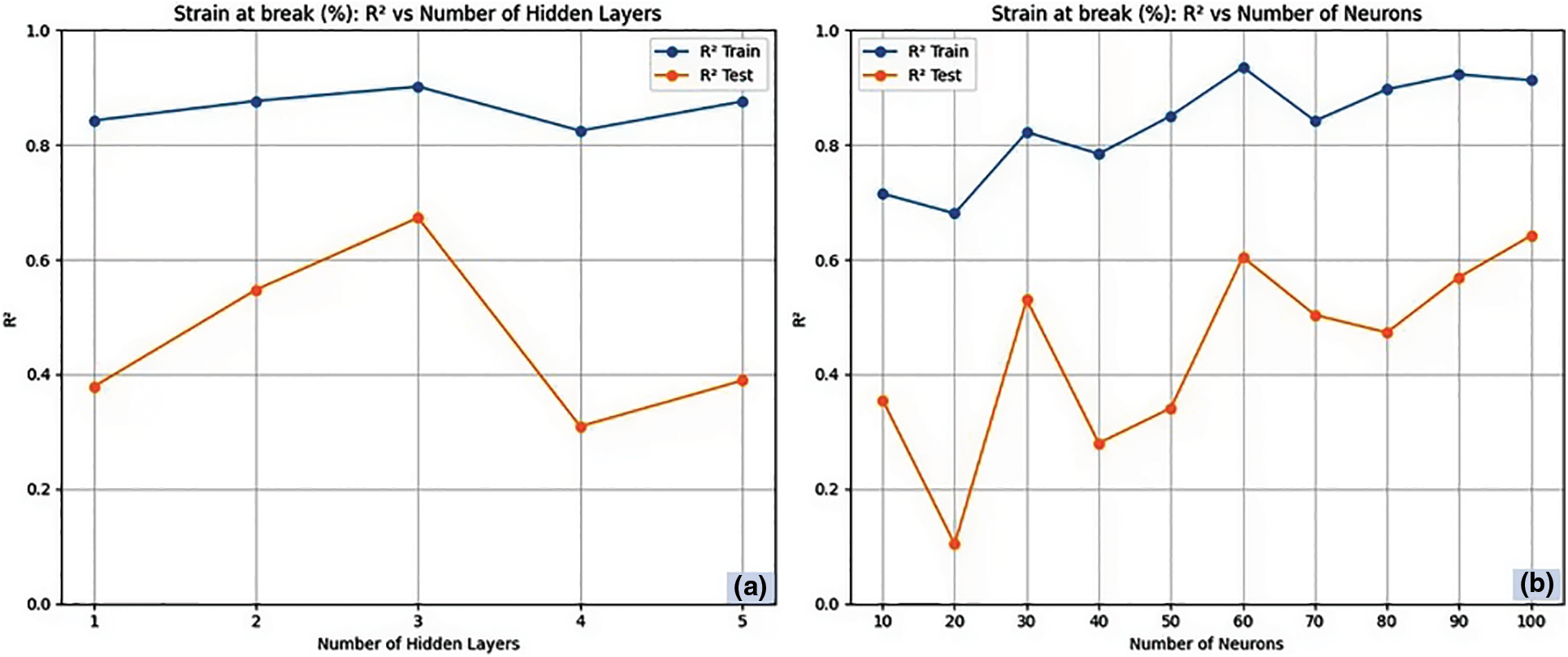

Fig. 7a,b presents the RNN architecture for elongation at break, correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. Considering the parameter of elongation at break, the R2 value remains persistent for training data and peaks for the two numbers of hidden layers in the test data [45]. Adding further hidden layers results in excessive fitting and does not increase the network’s predictability, as a drop in R2 value occurs with hidden layers above two. With the number of hidden layers as two, the R2 value is persistent with an increase in the number of neurons for training data and peaks for 100 neurons in test data, having an R2 value of 0.943 and 0.821 for training and test data, respectively. Further increases in the number of neurons tend to excessively fit the test data, leading to poor performance. Fig. 8a,b presents the RNN-LV architecture for elongation at break, correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. The RNN-LV model performs well at three hidden layers with an R2 value of 0.898 for test data, despite the constant trend in the training data in the case of elongation at the break parameter. With three as a hidden layer, the variation of R2 with the number of neurons was interrogated. Irrespective of the number of neurons, the R2 value was persistent for the training data, which reveals a better fit of the model [46]. On the other hand, maximum R2 value of 0.606 and 0.934 is obtained for three hidden layers and 80 neurons for test and training data, respectively. After this, performance starts to deteriorate like the previously described trend of the RNN-LV model.

Figure 7: RNN architecture for elongation at break. (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

Figure 8: RNN-LV architecture for elongation at break. (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

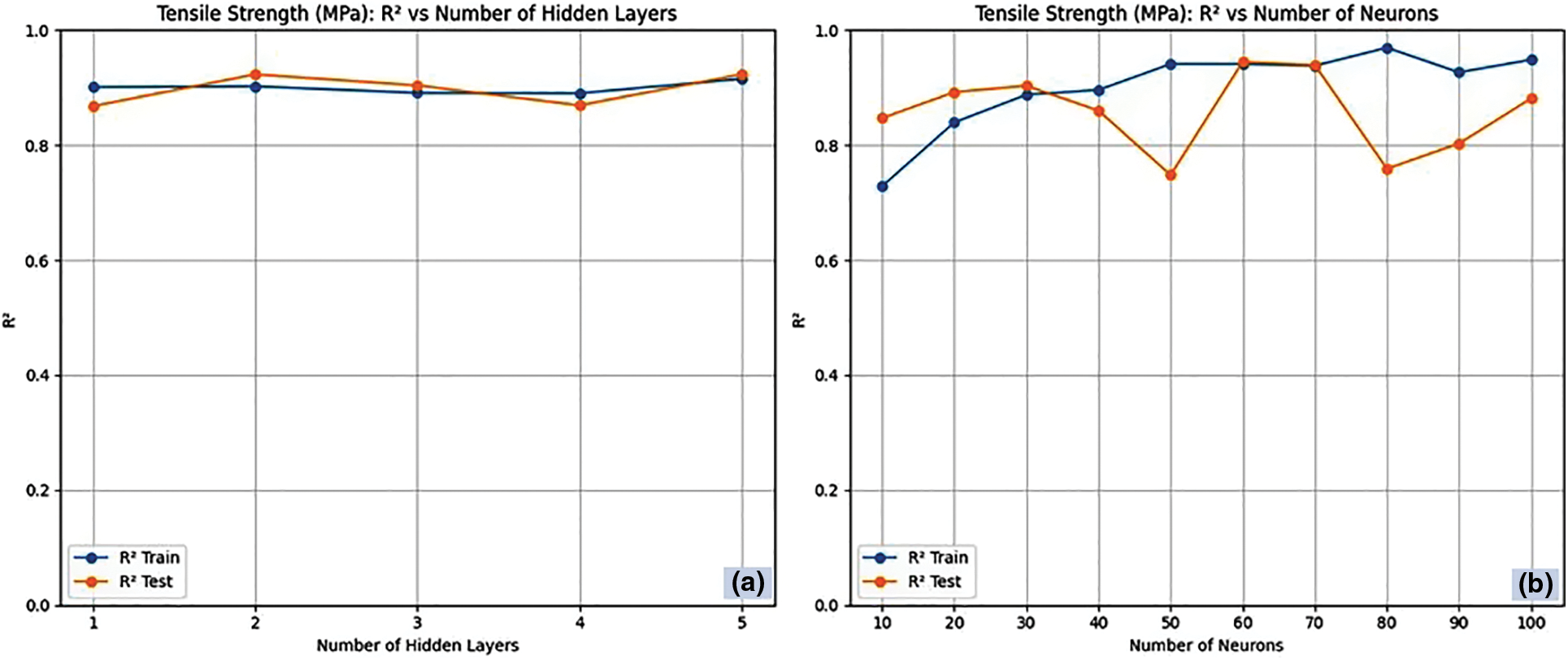

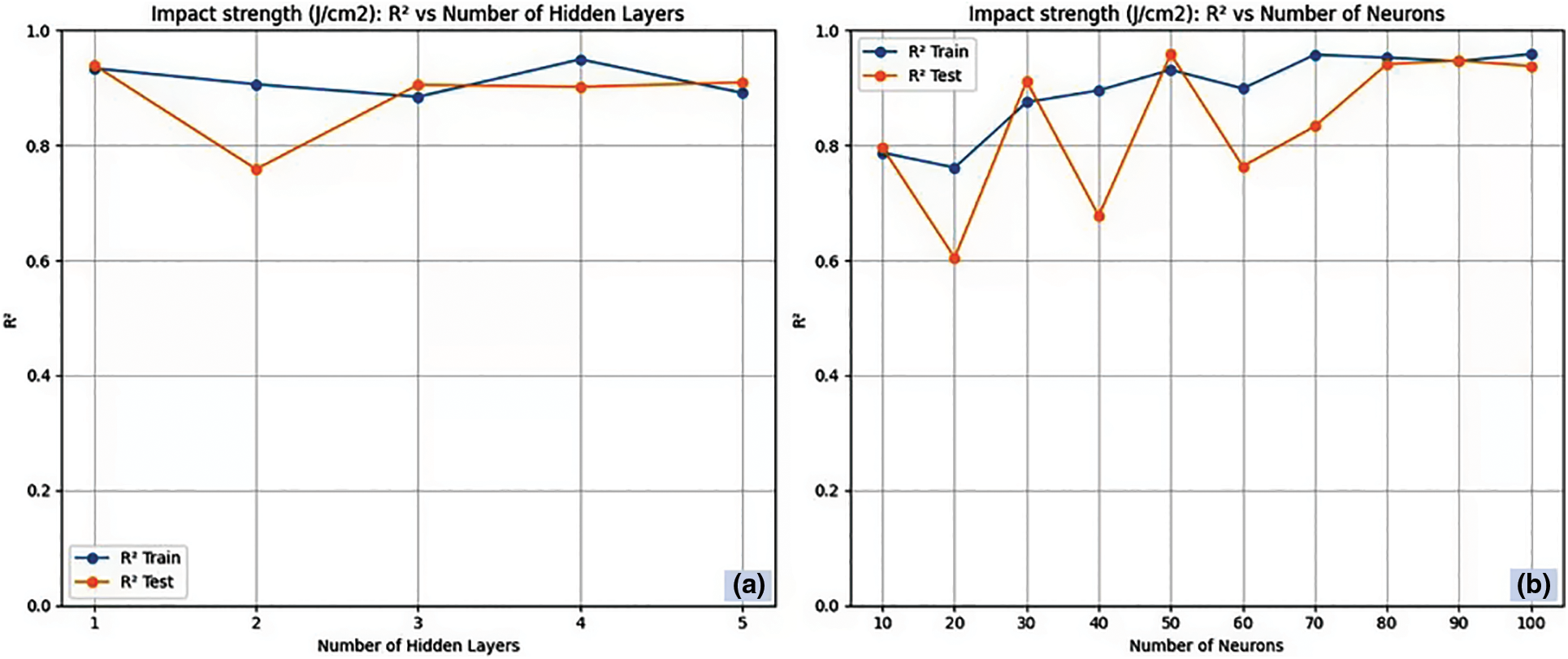

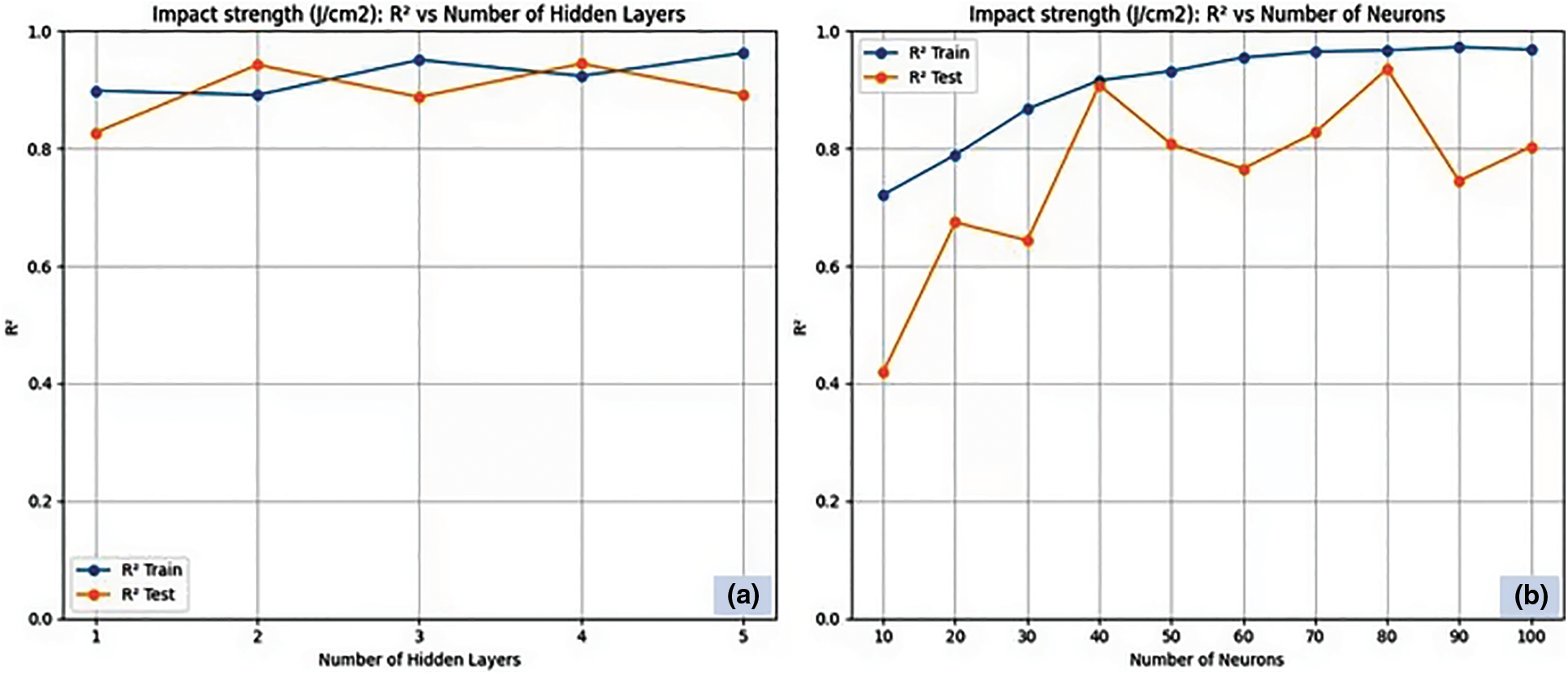

Fig. 9a,b presents the RNN architecture for impact strength correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. On predicting the impact strength with RNN, the R2 tends to increase with an increase in the number of hidden layers in the training data, showcasing better learning capability in the training phase [47]. On observing the test data, the R2 value declines after four hidden layers. This implies that the four number of hidden layers is sufficient to prevent excessive fitting and preserve the intricacy of the data. Now, the number of hidden layers to predict impact strength for RNN was fixed as four, and the variation of R2 against the number of neurons was analysed. The R2 value tends to increase with an increase in the number of neurons in the training data, whereas the maximum R2 value of 0.946 and 0.938 is obtained for 50 neurons in the test and training data, respectively. Further increases in the number of neurons tend to excessively fit the test data, leading to poor performance. Fig. 10a,b presents the RNN-LV architecture for impact strength correlating R2 with the number of hidden layers and neurons in each hidden layer. In the case of RNN-LV, the R2 value is persistent with an increase in the number of hidden layers and neurons in the training data [48]. On the other hand, in the case of test data, the R2 value increases with an increase in the number of hidden layers implying that enhancing the neural network’s depths can contribute to better efficacy overall. On observing the variation of R2 concerning the number of neurons, the maximum R2 value of 0.962 and 0.964 is obtained for three hidden layers and 80 neurons for test and training data, respectively. Performance declines after this, following a pattern akin to the RNN model’s previously mentioned trend.

Figure 9: RNN architecture for tensile strength. (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

Figure 10: RNN-LV architecture for tensile strength. (a) Number of hidden layers and (b) Number of neurons

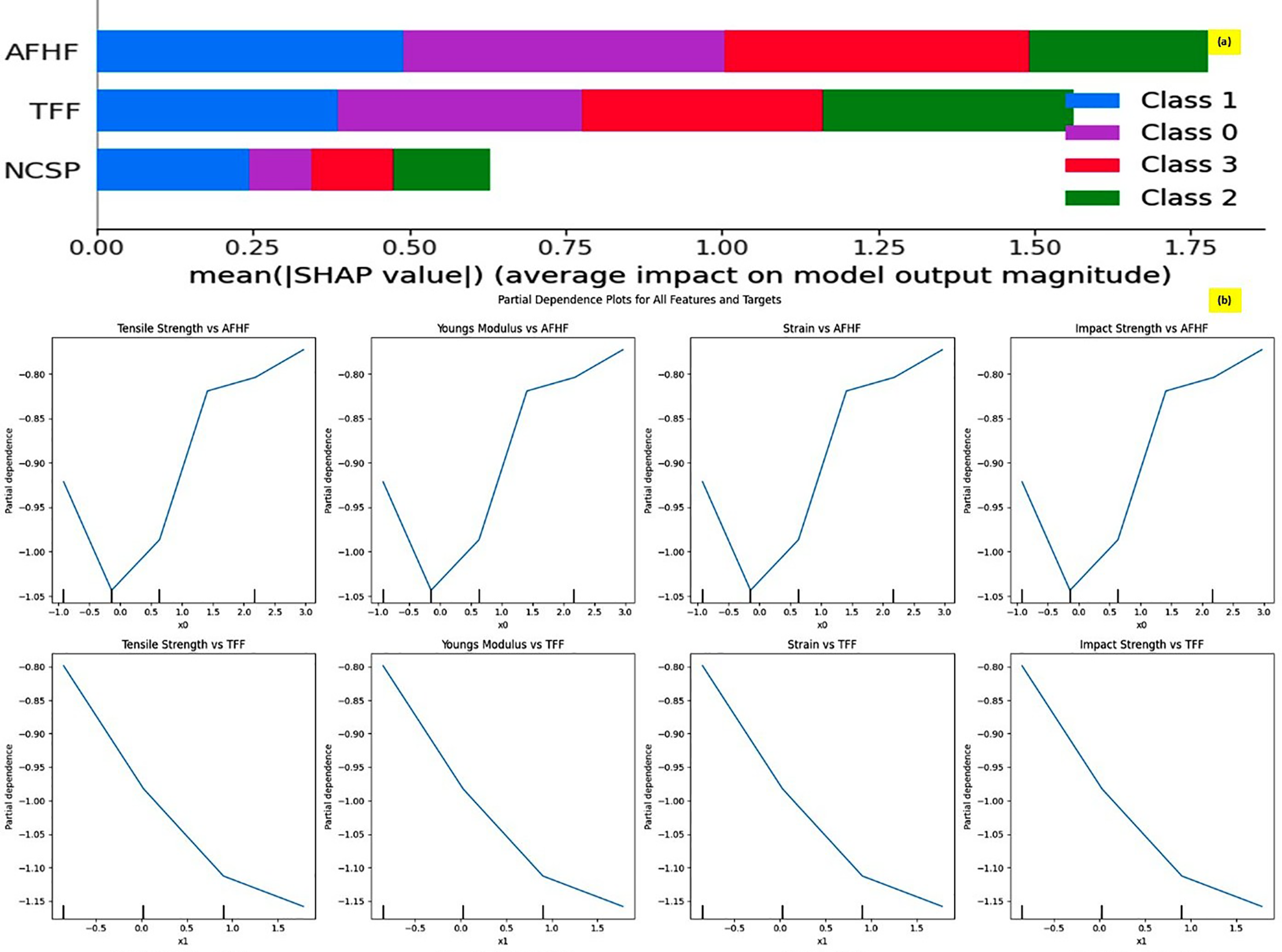

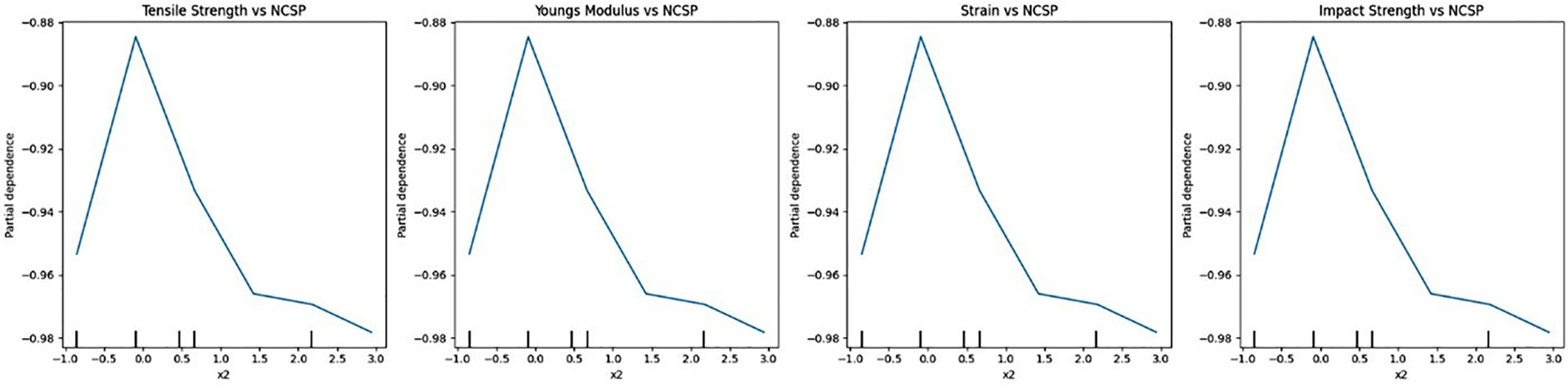

4.3.5 Interpretation of Model Predictions

Fig. 11a,b presents the Shapley Additive Explanations (SHAP) and Partial Dependence Plots (PDPs) which are commonly used in machine learning models to interpret the results obtained through prediction models. A SHAP plot provides a visual interpretation of a machine learning model by illustrating the contribution of each input feature to individual predictions. Positive SHAP values indicate features pushing the prediction higher, while negative values show features pulling it down. The color gradient typically represents the feature’s value. By aggregating this information across many predictions, SHAP plots highlight which features are most influential overall. As seen in Fig. 11a, the SHAP plot indicates that AFHF possesses more influence on the properties of the composite followed by TFF and finally NCSP. The PDP illustrates the relationship between a particular feature and the predicted outcome of a machine learning model, while averaging out the effects of all other features. It helps in understanding whether a feature has a linear, monotonic, or more complex influence on the target variable. PDPs are useful for interpreting complex models by visualizing marginal effects and identifying thresholds, nonlinear behavior, or interactions that may influence model decisions. The observations from Fig. 11b indicate that the RNN and RNN-LV models were positive in predicting the impact of AFHF and NCSP on the composite materials properties whereas negative in the case of TFF.

Figure 11: Interpretation of the prediction results. (a) SHAP plot and (b) PDPs

4.4 Prediction Accuracy of the Models

For every one of the mechanical characteristics under analysis, an assessment of the coefficient of determination was conducted to select the best prediction model. The capacity of a model to articulate the variation of the data is gauged by this coefficient [48]. Although it can account for a larger percentage of the variance in the data, an increased R2 number implies a superior fit for the model. These results suggest that instead of depending only on the characteristics of the system, the best machine learning model should be chosen based on the particular mechanical attribute that has to be foreseen. As previously pointed out, each mechanical characteristic is impacted by several variables that include the bonding among the substrate and the reinforcement, the interactions among the reinforcements and the substrate, the substrate modulus, strength, and reinforcement’s moduli, as well as the ductility [49]. The complicated structure of the nanocomposites in the present research suggests that they consist of four separate elements. It is challenging to make generalizations to one model that applies to all of the mechanical qualities under investigation because of the added complication.

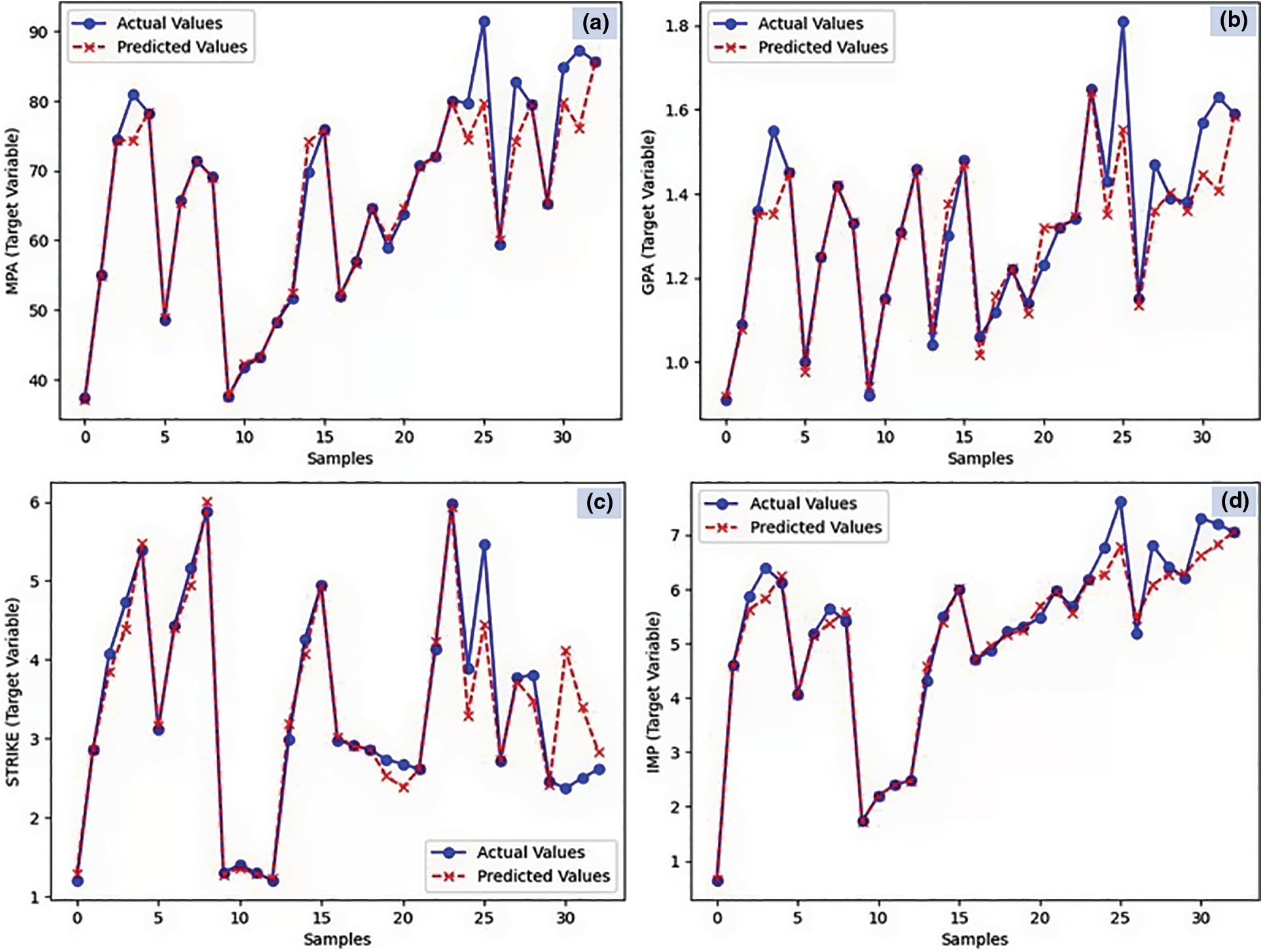

Fig. 12 shows the variation between the measured value and predicted value using the models with the maximum R2 value for each mechanical characteristic. The iterations were repeated 10 times with identical conditions in order to evaluate the model’s repeatability. Although the dots are clustered along the diagonal line, which denotes an ideal model fit, the graphs show a significant relationship between the projected values and the actual measurements. The plot’s slope, which is consistently very near to 1.0, serves as proof of validity [50]. The most accurate prediction is obtained for elongation at break with an R2 value of 0.956 preceded by impact strength. On the other hand, the lowest accuracy is noted for tensile strength. This behavior is explained by the nanocomposite’s anisotropy. Actually, the models based on machine learning do not take into account the anisotropic behavior that could be more noticeable for the tensile strength if the reinforcements and nanofiller were preferentially oriented in a specific direction [51]. Even while the nanofiller appears to be scattered arbitrarily in this investigation, the existence of tiny clusters in some areas may cause some anisotropy, which may have a greater impact on the tensile strength than the elongation at break. As a whole, the findings presented here show that the theoretical predictions and the practical measurements coincide quite well.

Figure 12: Variation between the measured value and predicted value using the models with maximum R2 value. (a) Young’s modulus, (b) Tensile strength, (c) Elongation at break and (d) Impact strength

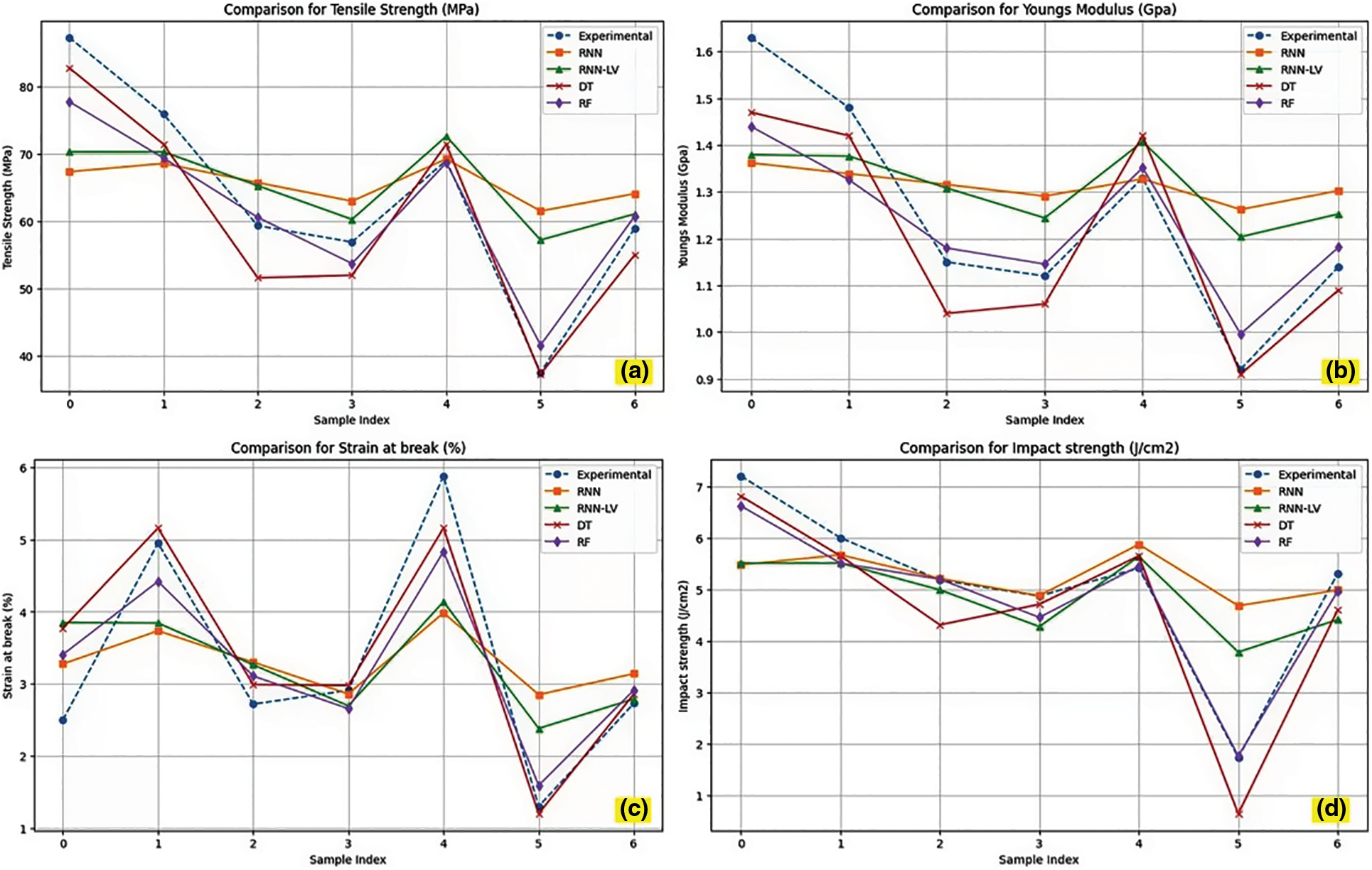

The mean absolute errors (MAE) and minimum squared errors (MSE) were evaluated as well in order to evaluate the reliability of the machine learning algorithms used here; the findings are compiled in Table 3. Many researchers agree that the MSE and MAE are crucial confirmation criteria for machine learning algorithms [52]. Fig. 13a–d presents the comparison of RNN and RNN-LV predicted values with traditional models like Decision Tree (DT) and Random Forest (RF). The more accurately the attribute is predicted, the lower the MSE and MAE values. In the case of tensile strength, RNN-LV has a lower MSE (0.1526) and MAE (0.2743) value compared to RNN, indicating that RNN-LV is an efficient prediction algorithm for tensile strength compared to RNN (Fig. 13a). Similarly, RNN-LV is also efficient in predicting the impact characteristics of the hybridized nanocomposites. On the other hand, RNN has the least MSE and MAE values compared to RNN-LV in predicting the Young’s modulus and elongation at break of the hybridized nanocomposites (Fig. 13b). Also, it was observed that slightly higher deviations were noticed in strain at break values as shown in Fig. 13c. Moreover, the predicted values of the RNN and RNN-LV models are in good agreement with the predictions of the traditional DT and RF models. Especially in the case of impact strength, the traditional models RF and DT show much closer agreement with RNN and RNN-LV predicted values, as shown in Fig. 13d.

Figure 13: Comparison of RNN and RNN-LV predicted value with traditional models like DT and RF. (a) Tensile strength, (b) Young’s modulus, (c) Strain at break and (d) Impact strength

A significant financial outlay and an enormous amount of experimental effort are needed for the creation of hybridized nanocomposites of polymers at various scales. Since the ingredients of these components have a significant impact on their functionalities, it is challenging to anticipate their properties with any degree of accuracy. In this work, hybridized nanocomposites strengthened with TFFs, AFHFs, and NCSPs were created using UPR as the matrix. Young’s modulus, impact resistance, strain at break, and tensile strength were measured experimentally using stress-strain and impact experiments. Additionally, the impact of several factors on the models’ accuracy was examined, as well as the efficacy of two ML-based regression models RNN and RNN-LV, in predicting these mechanical features.

• Tensile strength of the hybridized nanocomposites was well predicted by the RNN-LV model with 2 hidden layers, 80 neurons and maximum R2 values (0.915-test and 0.953-training).

• The same algorithm predicts the impact strength effectively with 3 hidden layers, 80 neurons and maximum R2 values (0.962-test and 0.964-training).

• Young’s modulus of the hybridized nanocomposites was well predicted by the RNN model with 4 hidden layers, 60 neurons and maximum R2 values (0.941-test and 0.989-training).

• The same algorithm predicts the elongation at break effectively with 2 hidden layers, 100 neurons and maximum R2 values (0.921-test and 0.943-training).

• Although the algorithms employed in this study fit the experimental findings quite well, they have some drawbacks due to their complexity, which suggests the existence of four separate components.

• Every mechanical characteristic is affected by several variables, such as the form, orientation, and size of the reinforcements and nanofiller, the interfacial adhesion between the reinforcements and nanofiller with the matrix, and the clustering of the nanoparticles. These variables may be responsible for the discrepancies between the experimental and anticipated data.

Ultimately, the findings presented here support the validity of the machine learning algorithm’s capacity to precisely estimate and forecast the particular mechanical characteristics of hybridized nanocomposites. Now, the obtained optimal material combination resembling maximum mechanical characteristics can be used to fabricate hybrid composites with specific functional characteristics. Amongst the many important advantages of this method are the large decrease in laboratory experimentation and the resulting optimisation of the duration and expenses related to material procurement and repeated physical testing. Since simulations may be used to assess various material compositions and alternatives, this enables improved effectiveness in the development and design of new hybridized nanocomposites, conserving both time and money during the phase of study and development.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jeyapaul Angel Ida Chellam: Investigation (Lead); Writing—original draft of manuscript (Equal); Bright Brailson Mansingh: Investigation (Supporting); Writing—review and editing of manuscript (Equal); Daniel Stalin Alex: Investigation (Supporting); Software; Writing—original draft of manuscript (Equal); Joseph Selvi Binoj: Investigation (supporting); Writing—review and editing (supporting). All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data not available due to ethical/legal/commercial restrictions. Due to the nature of this research, participants of this study did not agree for their data to be shared publicly, so supporting data is not available.This is an ongoing research work and hence the data cannot be shared at this moment.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ponnusamy DA, Gajendiran H, Mansingh BB, Binoj JS. Diffractional, spectroscopical, morphological, and thermal analysis of pretreated/enzyme modified cellulosic Cocos nucifera L. peduncle fiber. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2025;15(2):3115–26. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-05076-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Britto ASF, Prabha NR, Mansingh BB, David R, Singh AAMM, Binoj JS. Extraction and characterization of Dypsis lutescens peduncle fiber: agro-waste to probable reinforcement in biocomposites—a sustainable approach. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2025;15(2):2275–84. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-04950-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Wang Y, Zhang M, Lin A, Iyer A, Prasad AS, Li X, et al. Mining structure-property relationships in polymer nanocomposites using data driven finite element analysis and multi-task convolutional neural networks. Mol Syst Des Eng. 2020;5(5):962–75. doi:10.1039/D0ME00020E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Najjar IMR, Sadoun AM, Abd Elaziz M, Abdallah AW, Fathy A, Elsheikh AH. Predicting kerf quality characteristics in laser cutting of basalt fibers reinforced polymer composites using neural network and chimp optimization. Alex Eng J. 2022;61(12):11005–18. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2022.04.032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Machello C, Aghabalaei Baghaei K, Bazli M, Hadigheh A, Rajabipour A, Arashpour M, et al. Tree-based machine learning approach to modelling tensile strength retention of fibre reinforced polymer composites exposed to elevated temperatures. Compos Part B Eng. 2024;270(1):111132. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.111132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Shonkwiler S, Li X, Fenrich R, McMains S. Deep reinforcement learning for stacking sequence optimization of composite laminates. Manuf Lett. 2023;35:1203–13. doi:10.1016/j.mfglet.2023.08.133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Brailson Mansingh B, Binoj JS, Amala Mithin Minther Singh A, Sagai Francis Britto A. Influence of SiC nanoparticles on properties of alkali-treated areca fruit husk fiber/hybrid polymer composites. J Appl Polym Sci. 2023;140(10):e53591. doi:10.1002/app.53591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Binoj JS, Jaafar M, Brailson Mansingh B, Varaprasad KC. Extensive characterization of pretreated/enzyme treated cellulosic Areca catechu L. peduncle fiber for polymer composite applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2023;140(32):e54248. doi:10.1002/app.54248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Kazemi F, Shafighfard T, Yoo DY. Data-driven modeling of mechanical properties of fiber-reinforced concrete: a critical review. Arch Comput Meth Eng. 2024;31(4):2049–78. doi:10.1007/s11831-023-10043-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Kazemi F, Asgarkhani N, Shafighfard T, Jankowski R, Yoo DY. Machine-learning methods for estimating performance of structural concrete members reinforced with fiber-reinforced polymers. Arch Comput Meth Eng. 2025;32(1):571–603. doi:10.1007/s11831-024-10143-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Saleh MA, Kazemi F, Abdelgader HS, Isleem HF. Optimization-based multitarget stacked machine-learning model for estimating mechanical properties of conventional and fiber-reinforced preplaced aggregate concrete. Arch Civ Mech Eng. 2025;25(4):185. doi:10.1007/s43452-025-01236-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Özkan M, Karakoç A, Borghei M, Wiklund J, Rojas OJ, Paltakari J. Machine learning assisted design of tailor-made nanocellulose films: a combination of experimental and computational studies. Polym Compos. 2019;40(10):4013–22. doi:10.1002/pc.25262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Shafighfard T, Cender TA, Demir E. Additive manufacturing of compliance optimized variable stiffness composites through short fiber alignment along curvilinear paths. Addit Manuf. 2021;37(4):101728. doi:10.1016/j.addma.2020.101728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Champa-Bujaico E, Díez-Pascual AM, Lomas Redondo A, Garcia-Diaz P. Optimization of mechanical properties of multiscale hybrid polymer nanocomposites: a combination of experimental and machine learning techniques. Compos Part B Eng. 2024;269:111099. doi:10.1016/j.compositesb.2023.111099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Imoisili PE, Makhatha ME, Jen TC. Artificial intelligence prediction and optimization of the mechanical strength of modified natural fibre/MWCNT polymer nanocomposite. J Sci Adv Mater Devices. 2024;9(2):100705. doi:10.1016/j.jsamd.2024.100705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Thanikodi S, Meena M, Dwivedi YD, Aravind T, Giri J, Samdani MS, et al. Optimizing the selection of natural fibre reinforcement and polymer matrix for plastic composite using LS-SVM technique. Chemosphere. 2024;349(1):140971. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2023.140971. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Han C, Zhao H, Yang T, Liu X, Yu M, Wang GD. Optimizing interlaminar toughening of carbon-based filler/polymer nanocomposites by machine learning. Polym Test. 2023;128:108222. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2023.108222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Özyöksel Çiftçioğlu A, Kazemi F, Shafighfard T. Grey wolf optimizer integrated within boosting algorithm: application in mechanical properties prediction of ultra high-performance concrete including carbon nanotubes. Appl Mater Today. 2025;42(289):102601. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2025.102601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shafighfard T, Kazemi F, Bagherzadeh F, Mieloszyk M, Yoo DY. Chained machine learning model for predicting load capacity and ductility of steel fiber-reinforced concrete beams. Comput Aided Civil Eng. 2024;39(23):3573–94. doi:10.1111/mice.13164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Adel H, Palizban SMM, Sharifi SS, Ilchi Ghazaan M, Habibnejad Korayem A. Predicting mechanical properties of carbon nanotube-reinforced cementitious nanocomposites using interpretable ensemble learning models. Constr Build Mater. 2022;354(1):129209. doi:10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2022.129209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Mansingh BB, Bharathiraja G, Binoj JS, Natarajan M, Suryanto H, Siengchin S, et al. Influence of optimal alkali treated Areca catechu L. peduncle fiber for light weight polymer composites applications. J Appl Polym Sci. 2024;141(17):e55268. doi:10.1002/app.55268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cataldi P, Steiner P, Raine T, Lin K, Kocabas C, Young RJ, et al. Multifunctional biocomposites based on polyhydroxyalkanoate and graphene/carbon nanofiber hybrids for electrical and thermal applications. ACS Appl Polym Mater. 2020;2(8):3525–34. doi:10.1021/acsapm.0c00539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Biddeci G, Spinelli G, Colomba P, Di Blasi F. Halloysite nanotubes and sepiolite for health applications. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(5):4801. doi:10.3390/ijms24054801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Neog A, Biswas R. WS2 nanosheets as a potential candidate towards sensing heavy metal ions: a new dimension of 2D materials. Mater Res Bull. 2021;144(44):111471. doi:10.1016/j.materresbull.2021.111471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Ibrahim MM, Alnuwaiser MA, Elkaeed EB, Kotb H, Alshehri S, Abourehab MAS. Computational modeling of Hg/Ni ions separation via MOF/LDH nanocomposite: machine learning based modeling. Arab J Chem. 2022;15(12):104261. doi:10.1016/j.arabjc.2022.104261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Binoj JS, Jaafar M, Mansingh BB, Bharathiraja G. Extraction and characterization of novel cellulosic biofiber from peduncle of Areca catechu L. biowaste for sustainable biocomposites. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(17):20359–67. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-04081-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Binoj JS, Jaafar M, Mansingh BB, Pulikkal AK. Comprehensive investigation of Areca catechu tree peduncle biofiber reinforced biocomposites: influence of fiber loading and surface modification. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2024;14(18):23001–13. doi:10.1007/s13399-023-04182-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Bright BM, Binoj JS, Abu Hassan S, Wong WLE, Suryanto H, Liu S, et al. Feasibility study on thermo-mechanical performance of 3D printed and annealed coir fiber powder/polylactic acid eco-friendly biocomposites. Polym Compos. 2024;45(7):6512–24. doi:10.1002/pc.28214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Thooyavan Y, Kumaraswamidhas LA, Raj RDE, Binoj JS, Mansingh BB, Britto ASF, et al. Modelling and characterization of basalt/vinyl ester/SiC micro- and nano-hybrid biocomposites properties using novel ANN-GA approach. J Bionic Eng. 2024;21(2):938–52. doi:10.1007/s42235-024-00482-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Al Mahmud H, Radue MS, Chinkanjanarot S, Odegard GM. Multiscale modeling of epoxy-based nanocomposites reinforced with functionalized and non-functionalized graphene nanoplatelets. Polymers. 2021;13(12):1958. doi:10.3390/polym13121958. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Lu S, Jayaraman A. Machine learning for analyses and automation of structural characterization of polymer materials. Prog Polym Sci. 2024;153:101828. doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2024.101828. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Saravanakumar S, Sathiyamurthy S, Vinoth V. Enhancing machining accuracy of banana fiber-reinforced composites with ensemble machine learning. Measurement. 2024;235(4):114912. doi:10.1016/j.measurement.2024.114912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Sourabh K.Singh K, Kumar S, Singh KK. Computational data-driven based optimization of tribological performance of graphene filled glass fiber reinforced polymer composite using machine learning approach. Mater Today Proc. 2022;66(11):3838–46. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2022.06.253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

34. Kumaravel S, Suresh P. Ensemble machine learning for predicting and enhancing tribological performance of Al5083 alloy with HEA reinforcement. Proc Inst Mech Eng Part J J Eng Tribol. 2025;239(7):839–60. doi:10.1177/13506501241300905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Kazemi F, Özyüksel Çiftçioğlu A, Shafighfard T, Asgarkhani N, Jankowski R. RAGN-R: a multi-subject ensemble machine-learning method for estimating mechanical properties of advanced structural materials. Comput Struct. 2025;308(4):107657. doi:10.1016/j.compstruc.2025.107657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Jian Y, Hu P, Zhou Q, Zhang N, Cai DA, Zhou G, et al. A novel bidirectional LSTM network model for very high cycle random fatigue performance of CFRP composite thin plates. Int J Fatigue. 2025;190(9):108627. doi:10.1016/j.ijfatigue.2024.108627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Xie C, Qiu H, Liu L, You Y, Li H, Li Y, et al. Machine learning approaches in polymer science: progress and fundamental for a new paradigm. SmartMat. 2025;6(1):e1320. doi:10.1002/smm2.1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Alagulakshmi R, Ramalakshmi R, Veerasimman A, Palani G, Selvaraj M, Basumatary S. Advancements of machine learning techniques in fiber-filled polymer composites: a review. Polym Bull. 2025;82(7):2059–89. doi:10.1007/s00289-025-05638-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Yakoubi S. Sustainable revolution: ai-driven enhancements for composite polymer processing and optimization in intelligent food packaging. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025;18(1):82–107. doi:10.1007/s11947-024-03449-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Mahesha CR. Novel prediction model for validating the mechanical behaviour of composite materials using deep learning. Iran J Sci Technol Trans Civ Eng. 2025;49(4):4063–83. doi:10.1007/s40996-024-01646-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Kumar R, Suman S, Raj U, Mishra SK, Saw SK, Jayapalan S. Friction and wear characteristics of anti-skid masterbatch filled acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) based polymer composite using Taguchi and machine learning techniques. Iran Polym J. 2025;34(7):1039–55. doi:10.1007/s13726-024-01434-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Singh R, Jamwal N, Kumar M, Luyt AS, Sharma PK, Kumar R. Theoretical assessment of mechanical behaviour of LDPE/Cu composites using nonlinear polynomial regression analysis. Adv Mech Eng. 2025;17(2):23156. doi:10.1177/16878132251323156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Hristeva T. Application of graphic processing units in deep learning algorithms. AIP Conf Proc. 2022;2449:040002. doi:10.1063/5.0091076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

44. Besli NSO, Orakdogen N. Sepiolite-embedded binary nanocomposites of (alkyl)methacrylate-based responsive polymers: role of silanol groups of fibrillar nanoclay on functional and thermomechanical properties. React Funct Polym. 2021;161(1):104844. doi:10.1016/j.reactfunctpolym.2021.104844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Ho NX, Le TT, Le MV. Development of artificial intelligence based model for the prediction of Young’s modulus of polymer/carbon-nanotubes composites. Mech Adv Mater Struct. 2022;29(27):5965–78. doi:10.1080/15376494.2021.1969709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Zakaulla M, Pasha Y, Siddalingappa SK. Prediction of mechanical properties for polyetheretherketone composite reinforced with graphene and titanium powder using artificial neural network. Mater Today Proc. 2022;49(5):1268–74. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2021.06.365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Liu J, Zhang Y, Zhang Y, Kitipornchai S, Yang J. Machine learning assisted prediction of mechanical properties of graphene/aluminium nanocomposite based on molecular dynamics simulation. Mater Des. 2022;213(3):110334. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2021.110334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Qi Z, Zhang N, Liu Y, Chen W. Prediction of mechanical properties of carbon fiber based on cross-scale FEM and machine learning. Compos Struct. 2019;212(1):199–206. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2019.01.042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Gupta P, Gupta N, Saxena KK, Goyal S. Random forest modeling for fly ash-calcined clay geopolymer composite strength detection. J Compos Sci. 2021;5(10):271. doi:10.3390/jcs5100271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Binoj JS, Jaafar M, Mansingh BB, Raghu R. Viscoelastic and heat-resistant behavior of surface-treated Areca fruit husk fiber-reinforced polymer composites. Iran Polym J. 2023;32(7):841–53. doi:10.1007/s13726-023-01169-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Joo C, Park H, Lim J, Cho H, Kim J. Development of physical property prediction models for polypropylene composites with optimizing random forest hyperparameters. Int J Intell Syst. 2022;37(6):3625–53. doi:10.1002/int.22700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Kazemi F, Asgarkhani N, Jankowski R. Optimization-based stacked machine-learning method for seismic probability and risk assessment of reinforced concrete shear walls. Expert Syst Appl. 2024;255(2):124897. doi:10.1016/j.eswa.2024.124897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools