Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Application of a Hyperbranched Amide Polymer in High-Temperature Drilling Fluids: Inhibiting Barite Sag and Action Mechanisms

1 School of Petroleum Engineering, China University of Petroleum (East China), Qingdao, 266580, China

2 China Oilfield Services Ltd., Tianjin, 300459, China

* Corresponding Author: Qiang Sun. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Functional Polymer Composites: Synthesis, Characterization and Applications)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 757-772. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.069808

Received 01 July 2025; Accepted 20 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Addressing the critical challenges of viscosity loss and barite sag in synthetic-based drilling fluids (SBDFs) under high-temperature, high-pressure (HTHP) conditions, this study innovatively developed a hyperbranched amide polymer (SS-1) through a unique stepwise polycondensation strategy. By integrating dynamic ionic crosslinking for temperature-responsive rheology and rigid aromatic moieties ensuring thermal stability beyond 260°C, SS-1 achieves a molecular-level breakthrough. Performance evaluations demonstrate that adding merely 2.0 wt% SS-1 significantly enhances key properties of 210°C-aged SBDFs: plastic viscosity rises to 45 mPa·s, electrical stability (emulsion voltage) reaches 1426 V, and the sag factor declines to 0.509, outperforming conventional sulfonated polyacrylamide (S-PAM, 0.531) by 4.3%. Mechanistic investigations reveal a trifunctional synergistic anti-sag mechanism involving electrostatic adsorption onto barite surfaces, hyperbranched steric hindrance, and colloid-stabilizing network formation. SS-1 exhibits exceptional HTHP stabilization efficacy, substantially surpassing S-PAM, thereby providing an innovative molecular design strategy and scalable solution for next-generation high-performance drilling fluid stabilizers.Keywords

As petroleum exploration and development in China continue to extend into deeper and more complex formations, the drilling of challenging well types—such as deep wells, ultra-deep wells, highly deviated wells, multilateral wells, horizontal wells, and shale gas wells—has substantially increased. This trend imposes heightened demands on downhole chemical additives [1]. Contemporary drilling chemicals must evolve toward enhanced performance metrics, including high-temperature resistance, corrosion tolerance, multifunctionality, operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and environmental sustainability [2]. Generally speaking, drilling fluids, typically comprising mixtures of natural or synthetic chemicals with water, oil, or gas as base components supplemented by specialized additives, are broadly categorized into three types: water-based drilling fluids (WBDFs), oil-based drilling fluids (OBDFs), and synthetic-based drilling fluids (SBDFs) [3].

WBDFs are the most widely used due to their low cost, ready availability, low toxicity, and minimal environmental impact [4–7]. However, they exhibit intrinsic limitations in deep/ultra-deep applications, including poor solids suspension, which leads to barite sag, high fluid loss, and wellbore instability in reactive formations such as gypsum-salt layers and mudstones. In contrast, OBDFs offer superior lubricity, inhibition, and thermal stability, making them essential for demanding environments like deep and shale gas wells. Nevertheless, conventional OBDFs rely on emulsifiers (increasing cost and complicating operations) and often use diesel/mineral oils with high aromatic content, posing significant environmental and health risks despite recycling efforts [8–10]. This context drives the adoption of SBDFs. SBDFs, representing a new generation of formulations, have significantly advanced beyond conventional oil-based systems. They retain key advantages of OBDFs—including thermal stability, contamination resistance, and wellbore integrity, while offering additional benefits: lower viscosity, absence of aromatics, enhanced biodegradability, and non-fluorescence. These attributes have established SBDFs as the preferred choice for deepwater marine operations and environmentally sensitive regions [11]. However, the inherently low viscosity of SBDFs presents a dual challenge: beneficial for rheology control yet problematic for barite suspension [12]. Under HTHP conditions, barite sagging occurs readily, potentially triggering well control incidents, pipe sticking, and impaired hole cleaning—all of which jeopardize drilling efficiency [13]. Numerous studies have explored polymers or nanomaterials to enhance drilling fluid performance [14–18]. For instance, graphene, carbon nanotubes, modified polyacrylamide, nanopolymers [19–24]. To augment the thermal resilience of drilling muds, researchers have investigated synthetic polymers (e.g., sulfonated polyacrylamides, hyperbranched polymers) and modified compounds (e.g., sulfonated phenolic resins) as stabilizing additives [25–27]. Due to the excellent properties of hyperbranched polymers, such as high thermal stability, strong shear stability and high functional group density, they can effectively enhance the temperature resistance, suspension stability, emulsification, wax prevention and scale inhibition capabilities of drilling fluids, as well as the oil and gas transportation and water treatment agent functions in oil fields [28]. The surface of hyperbranched polyethyleneimine is covered with a large number of amino groups, which are adsorbed onto the clay surface through electrostatic attraction to form a coating layer. Due to its low biological toxicity, it is widely used as a drilling fluid additive, such as a shale inhibitor [29].

This study evaluates S-PAM’s actual performance, including uncontrolled crosslinking (gelation) and poor thermal stability in conventional synthesis. To overcome these constraints, we designed a hyperbranched polymer (SS-1) via a topologically engineered stepwise polycondensation strategy. The innovation lies in its pioneering rigid-flexible dynamic hyperbranched architecture, which minimizes side reactions and enables precise branching control—a synthesis approach previously untested according to current literature. Furthermore, this structural design activates a temperature-responsive mechanism: elevated temperatures induce polymer chain extension, increasing entanglement density and enhancing viscosity—a distinct advantage over conventional polymers. Key synthetic features include: (1) Precision amidation: Constructing flexible hydrophobic branches via polyethylenimine and ricinoleic acid to modulate branching density; (2) Rigid anchoring: Incorporating aromatic frameworks through benzene-1,2,4-tricarboxylic anhydride to enhance thermal stability; (3) Dynamic ionic crosslinking: Employing sulfonated asphalt to provide sulfonate groups for thermally reversible network reorganization; (4) Terminal reinforcement: Locking 3D networks via tannic acid phenol-hydroxyl crosslinking. Performance assessments (rheology, electrical stability, fluid loss, sag resistance) demonstrated SS-1’s superior performance at high temperatures vs. S-PAM. Notably, SS-1 achieved a sag factor of 0.509 at 210°C, meeting operational requirements beyond 200°C. Mechanistic studies via zeta potential and particle size analysis elucidated SS-1’s anti-settling behavior, offering novel insights for next-generation ultra-deep well drilling fluids.

Experimental Materials: Ricinoleic acid (95.0%, Shanghai Lisen Chemical Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); Polyethylenimine (99.0%, Aladdin, Shanghai, China); Tannic acid (98.0%, Aladdin); Acetic anhydride (98.0%, Aladdin); p-Toluenesulfonic acid (98.0%, Aladdin); N, N-Dimethylformamide (99.0%, Macklin, Shanghai, China); Deionized water (Lab-grade, Shanghai, China). As shown in Table 1.

Gas-to-liquid (GTL) base oil (99.0%, synthesized in-house, Sinopec Research Institute, Beijing, China); Calcium oxide (99.0%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China); Emulsifier (Jiangsu Haian Petrochemical Co., Ltd., Nantong, China); Barite (95.0%, Tianjin Yandong Haotian Mineral Products Co., Ltd., Tianjin, China); Sulfonated polyacrylamide (S-PAM, 98.0%, Shandong Noah Biological Technology Co., Ltd., Heze, China).

Experimental Instruments: Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectrometer (Frontier, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA); Thermogravimetric analyzer (DZ-TGA-101, DZ Instruments, Nanjing, China); Six-speed viscometer (OFITE-900, Fann Instrument Company, Conroe, TX, USA); Electrical stability tester (FANN-23D, Fann Instrument Company, USA); Drilling fluid densimeter (XYM-3, Kensee Instruments, Shanghai, China); Nanoparticle size and zeta potential analyzer (BeNano 90, Dandong Bettersize Instruments, Dandong, China); Laser diffraction particle size analyzer (Mastersizer 3000+, Malvern Panalytical, Worcestershire, UK).

2.2 Synthesis of the Sag Stabilizer (SS-1)

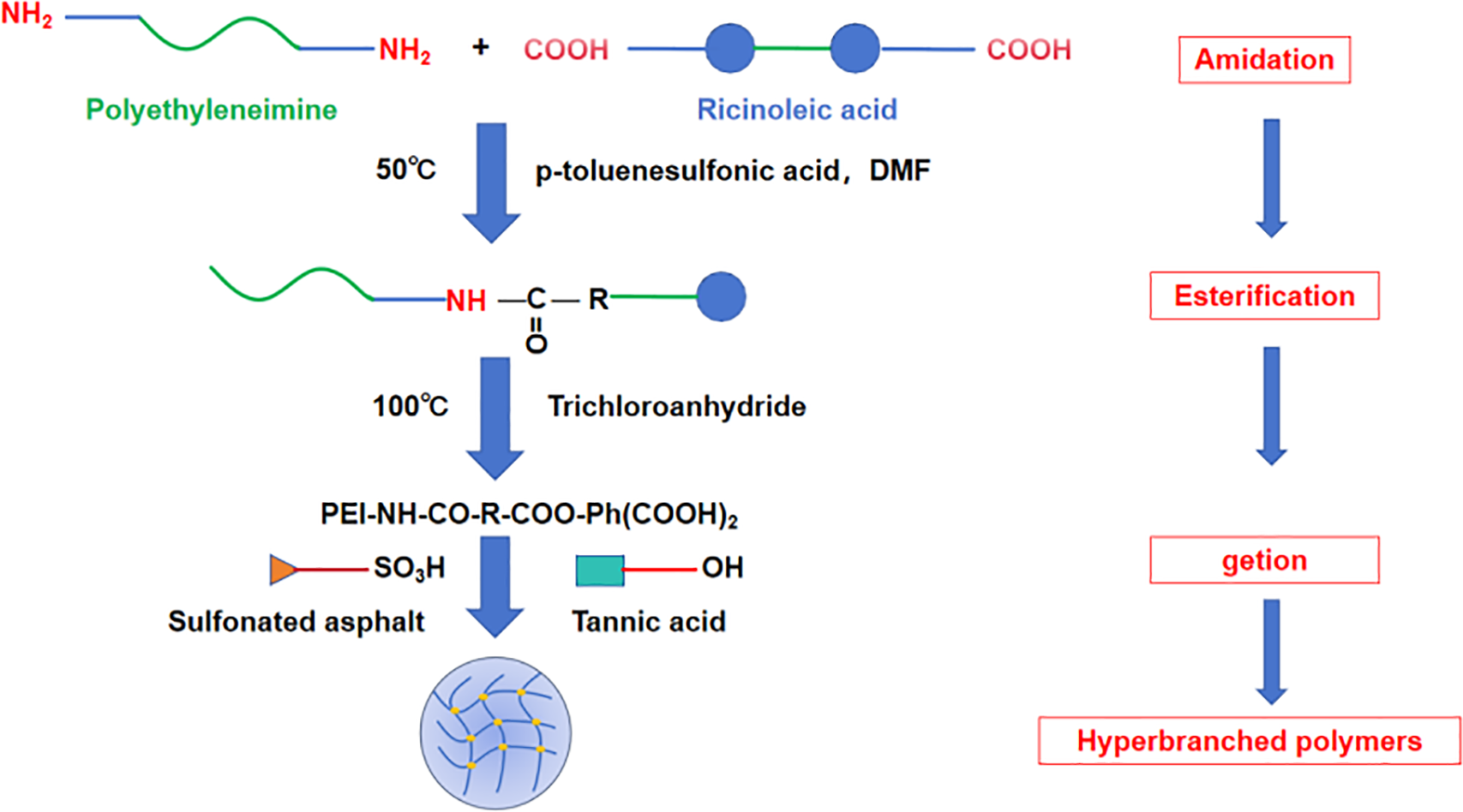

SS-1 was synthesized via multifunctional polycondensation in aqueous solution to construct a crosslinked network. Fig. 1 illustrates the synthetic route, with detailed steps as follows:

(1) Pre-treatment: Ricinoleic acid (15 g) was purified by distillation under reduced pressure (0.1 MPa, 90°C, N2 atmosphere) for 2 h to remove volatile impurities, yielding 14.2 g (94.7%) of a colorless viscous liquid. Benzene-1,2,4-tricarboxylic acid (10 g) was reacted with acetic anhydride (20 g) and p-toluenesulfonic acid (0.05 g) at 120°C for 5 h to form trimellitic anhydride, followed by purification. The crude product was dissolved in 50 mL of acetone at 60°C, filtered to remove catalysts, and cooled to 0°C for crystallization. White crystals were collected by vacuum filtration and dried at 80°C (yield: 8.9 g, 89.0%).

(2) Polymerization: Polyethylenimine (10 g) was dissolved in 100 mL DMF, under N2. Purified ricinoleic acid was added, and the mixture was stirred (500 rpm) at 50°C for 4 h. Pre-synthesized trimellitic anhydride was added, and the reaction proceeded at 100°C for 7 h (mechanical stirring: 300 rpm). Powdered sulfonated asphalt (20 g) was incorporated, and the reaction continued at 110°C for 5 h (N2 atmosphere, 300 rpm). Tannic acid (5 g) was added, and the mixture was stirred at 70°C for 4 h. The polymer precursor was precipitated by dropwise addition into 500 mL ice-cold diethyl ether, followed by vacuum filtration. The solid was washed with ethanol/water (1:1 v/v, 3 × 50 mL) to remove unreacted monomers (yield: 41.8 g, 86.4%).

(3) Post-treatment: The crude polymer was dissolved in 200 mL deionized water at 60°C and neutralized to pH 8.0 using 10 wt% NaOH solution. The solution was dialyzed (MWCO: 3.5 kDa) against deionized water for 48 h, then lyophilized to obtain SS-1 as a pale-yellow solid (final yield: 38.5 g, 82.1%).

Figure 1: Schematic synthetic route of SS-1

2.3 Preparation of Synthetic Base Drilling Fluid

The performance evaluation employed a synthetic base drilling fluid formulation comprising: gas-to-liquid (GTL) synthetic oil, 25% CaCl2 aqueous solution, 4% emulsifier, 2 wt% sedimentation stabilizer, 1.5 wt% organoclay, 18 wt% CaO, 4 wt% fluid loss additive, 1 wt% hydrophobic nano-silica, and 555 g barite (ρ = 1.8 g/cm3). Three comparative systems were prepared: Base fluid without stabilizer, Base fluid + sulfonated polyacrylamide, Base fluid + synthesized SS-1 stabilizer. The specific preparation steps are as follows:

(1) The synthetic base drilling fluid slurry is prepared by first measuring gas-to-liquid (GTL) synthetic oil using a graduated cylinder and weighing the corresponding 4% emulsifier, followed by transferring both components to a high-speed mixing cup where initial homogenization occurs at 11,000 rpm for 30 min. Subsequently, 25% calcium chloride (CaCl2) aqueous solution is added with 20-min high-speed mixing (11,000 rpm), after which fluid loss additive, calcium oxide (CaO), and hydrophobic nano-silica are sequentially incorporated, each followed by identical 20-min mixing cycles. Upon complete dispersion of all individual additives, 555 g barite is incrementally introduced in small batches, culminating in final homogenization at 11,000 rpm for 90 min, yielding the base slurry ready for experimental use.

(2) Formulate a synthetic-based drilling fluid containing polymers. SS-1 or S-PAM was introduced to the base fluid before barite addition, followed by 20-min mixing at 11,000 rpm. Barite was then incorporated incrementally with a final 90-min homogenization. All samples underwent comprehensive performance testing following API 13B-2 standards.

2.4 Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

Molecular structures of the polymers were characterized using a Frontier FTIR spectrometer (PerkinElmer). Samples were prepared by grinding with potassium chloride (KBr) to form pellets. Spectra were acquired across the wavenumber range of 400–4000 cm−1.

2.5 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

Thermal stability was assessed using a DZ-TGA-101 thermogravimetric analyzer. An Al2O3 crucible was zero-calibrated in the sample chamber. Precisely 0.4 g of sample was weighed into the crucible, which was then returned to the chamber. The TGA program heated samples at 10°C/min under N2 atmosphere to a final temperature of 680°C. Thermograms of SS-1 were recorded and analyzed.

Particle size distributions of SS-1 suspensions were determined via dynamic laser scattering (DLS) using a Mastersizer 3000+ instrument (Malvern Panalytical, UK). To prevent particle aggregation during measurements, samples were subjected to ultrasonic agitation at a fixed frequency of 1500 Hz and repeated three times to get the average value.

2.7 Zeta Potential Measurements

The effect of temperature on the zeta potential value of drilling fluid was studied by BeNano 90 nm particle size and Zeta potential analyzer, and repeated three times to get the average value.

2.8 Drilling Fluid Performance Evaluation

2.8.1 Rheological Property Measurements

Drilling fluid samples were subjected to high-speed stirring (11,000 rpm) for 20–30 min in a slurry cup. Subsequently, the homogenized samples were transferred to the test cup of a six-speed viscometer (OFITE-900). Rheological parameters were measured sequentially at rotational speeds of 600, 300, 200, 100, 6, and 3 rev/min. Apparent viscosity (AV), plastic viscosity (PV), and yield point (YP) were calculated using the following standard equations [30], and repeated three times to get the average value.

2.8.2 Electrical Stability Test

Pour the prepared base slurry into a measuring cup and heat it to 55°C in an aqueous bath. Insert the plug steadily into the test cup without touching the test cup and keep it stable. Measure the demulsification voltage and repeat three times to get the average value.

2.8.3 Settlement Stability Test

Test samples were subjected to hot rolling at predetermined temperatures for 16 h, followed by static aging at ambient conditions for 24 h. The densities of the top (ρtop) and bottom (ρbottom) layers were then measured using a drilling fluid densimeter. The sag factor (SC) was calculated as follows:

A SC value >0.52 indicates significant barite sedimentation within the drilling fluid system, while SC = 0.50 demonstrates optimal sag resistance with no observable settlement.

The impact of SBDF on the environment was evaluated through biological toxicity tests, and the 50% lethal concentration was determined using the fluorescent bacteria method [31].

Fig. 2 displays the FTIR spectrum of SS-1. Characteristic peaks were assigned as follows: 3400–3700 cm−1 (O-H and residual N-H stretching vibrations), 1719 cm−1 (symmetric C=O stretching), 1658 cm−1 (amide C=O stretching), 1589 cm−1 (aromatic C=C bending), 1423 cm−1 (amide C-N stretching), 1113 cm−1 (ester C-O-C stretching), and 1035 cm−1 (S=O stretching of sulfonate groups from sulfonated asphalt). Additional peaks at 2918 and 2850 cm−1 correspond to symmetric -CH2- stretching from alkyl chains of ricinoleic acid and sulfonated asphalt, while the 799 cm−1 band represents aromatic C-H out-of-plane bending in benzene-1,2,4-tricarboxylic moieties. The spectral features confirm perfect alignment with the designed molecular architecture of the sag stabilizer, indicating complete progression of the synthesis reaction.

Figure 2: IR spectrum of SS-1

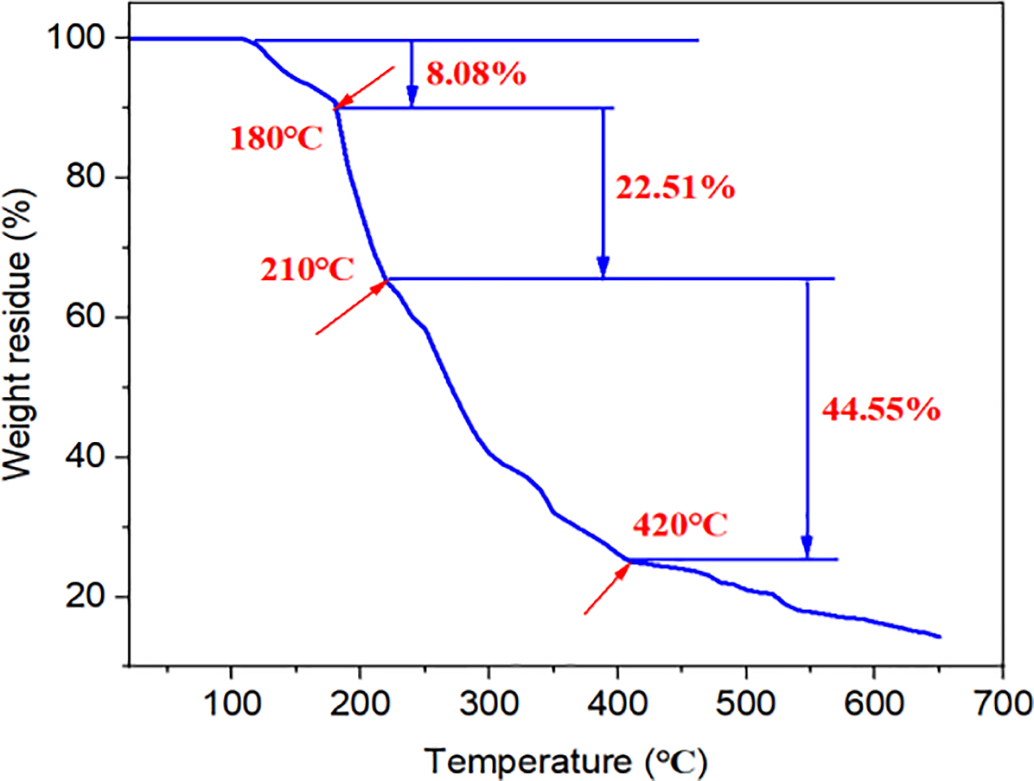

Fig. 3 shows the TGA analysis curve of SS-1. It can be observed that when heated to 260°C, the polymer exhibits good thermal stability with mass loss within 2%, likely attributed to the evaporation of intra- and intermolecular water and incompletely crosslinked low-molecular-weight sulfonates. As the temperature increased from 260°C to 300°C, the TGA curve declined rapidly with a mass loss rate reaching 24.58%, possibly due to thermal decomposition of minor molecular side groups. When the temperature rose from 300°C to 530°C, the thermogravimetric curve showed a slower declining trend with a mass loss rate of 18.94%, resulting from the degradation of the polymer backbone that disrupted the molecular structure. Beyond 530°C, the molecular structure of the polymer underwent complete degradation. The presence of sulfonic acid groups, benzene rings, and other rigid structural units enhanced the chain rigidity of the polymer, thereby improving the high-temperature stability of SS-1. On the contrary, Fig. 4 shows the TGA analysis curve of S-PAM. At 210°C, the thermogravimetric loss has decreased significantly to 30.59%. At 420°C, its molecular structure has completely degraded, and the thermogravimetric loss rate is 75.14%, which is 166% higher than that of SS-1. These results demonstrate that SS-1 has more outstanding thermal stability compared with S-PAM.

Figure 3: TGA analysis curve of SS-1

Figure 4: TGA analysis curve of S-PAM

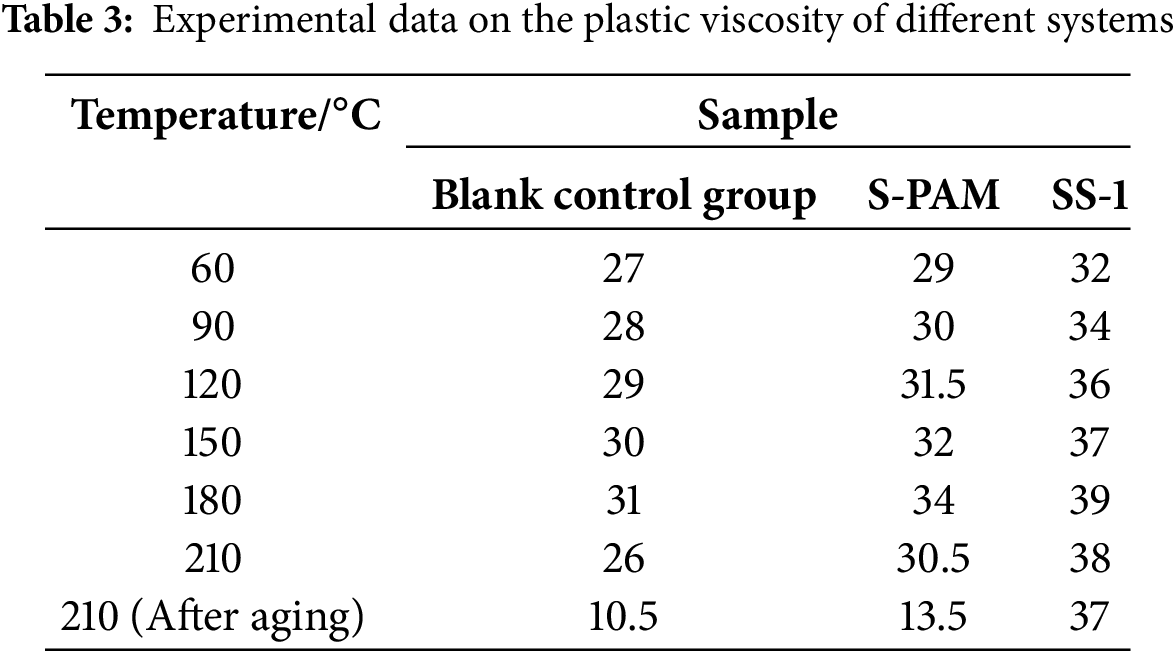

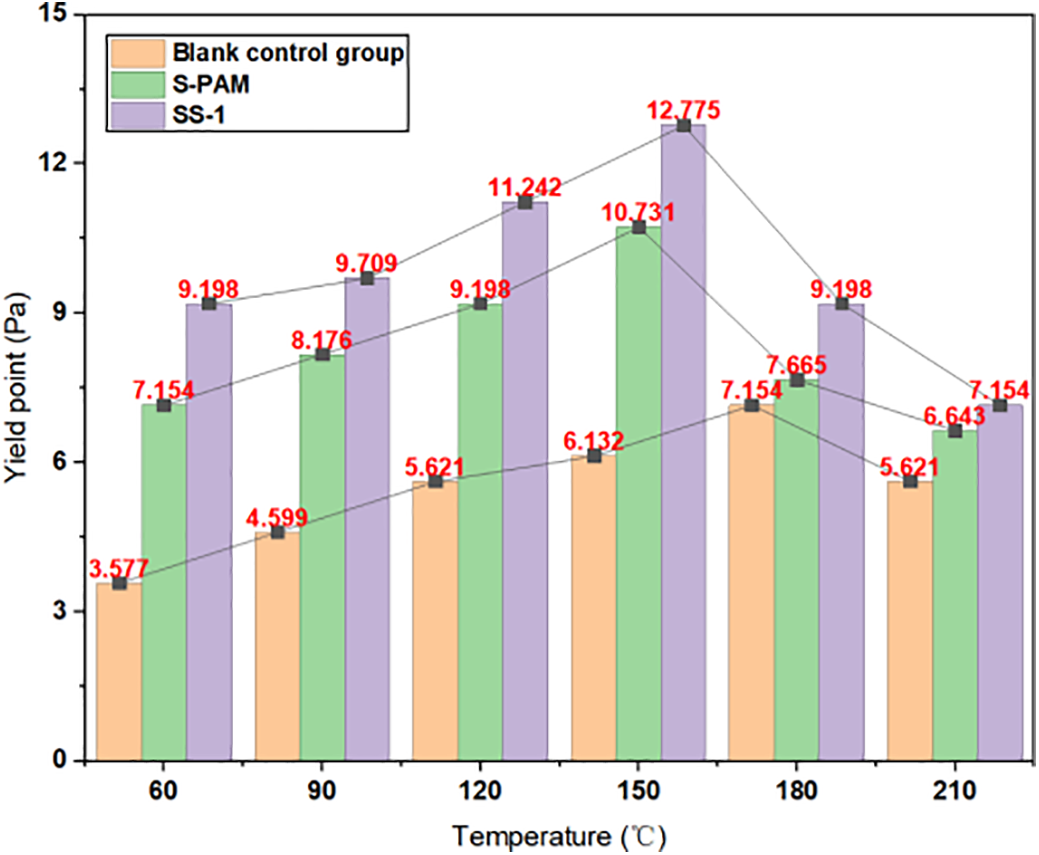

The rheological test data for three different systems of drilling fluids are presented in Tables 2–4, and the trend graphs are shown in Figs. 5–7. As shown in Figs. 5–7, the samples containing SS-1 exhibit higher viscosity and yield point compared to the blank control group and S-PAM. At a high temperature of 210°C, the AV, PV, and YP of SS-1 are, respectively: 45, 38 mPa·s, and 7.154 Pa which are superior to the blank group (31.5, 26 mPa·s, 5.621 Pa) and S-PAM (37, 30.5 mPa·s, 6.643 Pa). As the temperature gradually increases, the apparent viscosity, plastic viscosity, and shear stress of the drilling fluid first increase and then decrease. Furthermore, after aging at 210°C for 16 h, the viscosity of the blank group and the group with S-PAM decreased significantly, while the viscosity change range of the experimental group containing SS-1 was relatively smaller. This is attributed to the covalent bonds connecting the S-PAM molecules. Elevated temperatures break these chains, significantly reducing the solution’s viscosity. In the control group (without stabilizers), emulsification occurs during aging, leading to emulsifier deactivation. This disrupts the molecular structure and causes a sharp viscosity drop. However, adding SS-1—which leverages dynamic ionic bond recombination, a rigid framework, and electrostatic repulsion—results in nearly unchanged viscosity after aging. This indicates that increased temperature enhances the emulsification and dispersion capabilities of the drilling fluid, leading to an increase in its viscosity. However, when the temperature exceeds 180°C, high temperatures cause the emulsifiers in the drilling fluid to become ineffective, disrupting the spatial network structure of the drilling fluid, resulting in a decrease in both viscosity and yield point.

Figure 5: Apparent viscosity and temperature variation trend of different drilling fluid systems

Figure 6: Plastic viscosity and temperature variation trend of different drilling fluid systems

Figure 7: Yield point and temperature variation trend of different drilling fluid systems

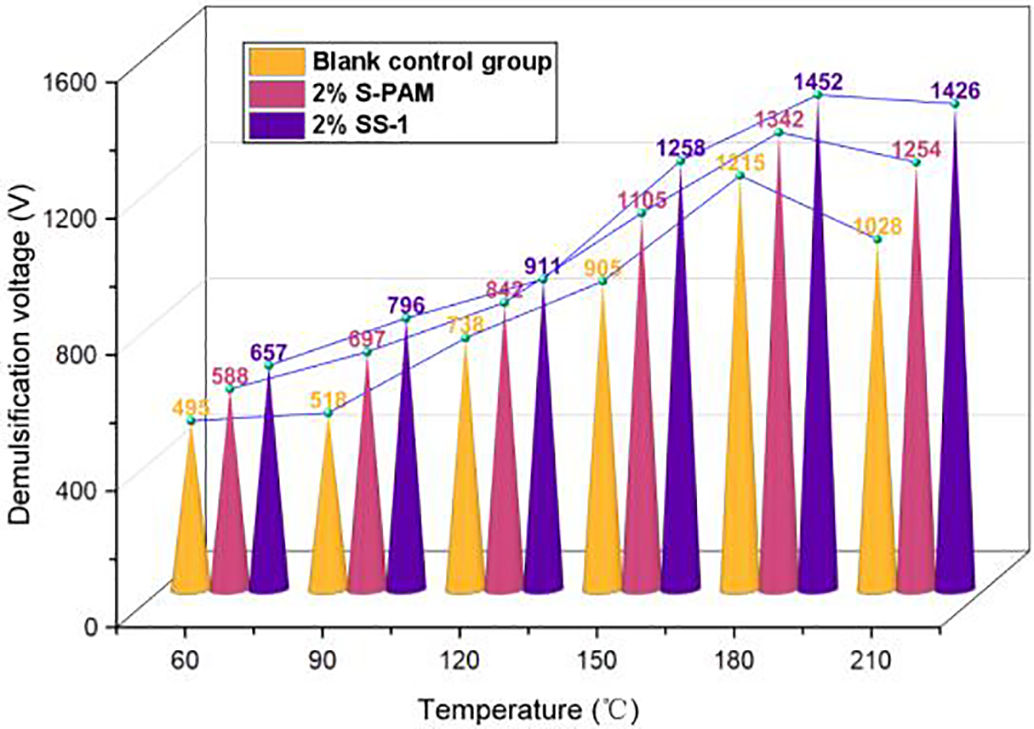

As shown in Fig. 8, the demulsification voltage of synthetic base drilling fluid initially increases before decreasing with rising temperature. This indicates enhanced electrical stability of the drilling fluid at elevated temperatures. However, beyond 180°C, the demulsification voltage shows a marginal reduction due to disruption of the oil-in-water structure, which compromises electrical stability. Notably, at 210°C, the system containing SS-1 exhibits a significantly higher demulsification voltage than both the blank-control group and the S-PAM formulation, with increases of 27.9% and 12.1%, respectively. This demonstrates that the base slurry incorporating SS-1 maintains superior stability, requiring higher voltage for demulsification.

Figure 8: The variation trend of demulsification voltage and temperature of different drilling fluid systems

As shown in Fig. 9, the settling coefficient increases progressively with rising temperature, indicating that elevated temperatures negatively impact drilling fluid sedimentation. At excessive temperatures, this sedimentation compromises overall fluid performance. Specifically at 180°C, the blank group exhibits a settling coefficient of 0.538, confirming performance degradation due to internal sedimentation, while formulations containing S-PAM and SS-1 demonstrate lower coefficients of 0.515 and 0.505, respectively. When the temperature exceeds 200°C, the settling coefficients further increase to 0.531 (S-PAM) and 0.509 (SS-1). These results demonstrate that the synthesized SS-1 polymer provides remarkable sedimentation stability to drilling fluids, outperforming the commercially available S-PAM additive, particularly under high-temperature conditions.

Figure 9: The variation trend of the settlement coefficient and temperature of different drilling fluid systems

Drilling fluids, under the action of sedimentation stabilizers, achieve amphiphilic bridging at the solid-liquid interface through directional anchoring of hydrophilic groups onto barite particle surfaces via electrostatic adsorption, while hydrophobic groups embed into the continuous oil phase. The polymer backbone incorporates thermal-resistant groups—including rigid aromatic rings (e.g., trimellitate residues) and sulfonic groups—imparting thermal stability above 200°C to the system. The three-dimensional network formed by intermolecular crosslinking generates synergistic effects: (1) Steric Hindrance: Isolated networks at crosslinking nodes restrict barite particle migration, enhancing static sedimentation stability; (2) Rheological Regulation: Shear-thinning behavior maintains controllable rheology under high-temperature/high-pressure conditions. The mechanistic schematic is illustrated in Fig. 10.

Figure 10: Schematic diagram of the mechanism of action of the settlement stabilizer

Zeta potential serves as a critical indicator of clay particle stability in drilling fluids. As shown in Fig. 11, the initial base slurry exhibits zeta potentials of −34.11 mV (base slurry), −34.42 mV (S-PAM), and −34.85 mV (SS-1), with absolute values >30 mV confirming excellent colloidal stability per DLVO theory [32]. Upon heating from 25°C to 210°C, these values shift to −25.12 mV (base slurry), −30.02 mV (S-PAM), and −40.96 mV (SS-1), revealing a unique positive correlation between |zeta potential| and temperature exclusively for SS-1-modified systems. This anomalous behavior arises from three mechanisms: (1) SS-1’s PEI-derived -NH3+ groups electrostatically occupy clay surface sites, counteracting the EDL compression and chain collapse observed in blank/S-PAM systems where high temperatures accelerate counterion migration and suppress carboxyl/sulfonate ionization; (2) Hydrophobic moieties in SS-1 reduce diffuse EDL thickness, mitigating electrolyte-induced compression; (3) Extended PEI chains form hydration layers that increase interparticle distances, weakening van der Waals forces while enhancing electrostatic repulsion. Furthermore, SS-1’s rising |zeta potential| with temperature stems from thermally promoted ionization of -SO3−/-COO− groups, chain extension exposing buried charges, restructuring of aqueous hydrogen-bond networks facilitating faster electrophoretic mobility, and counterion desorption reducing charge shielding–collectively re-expanding the EDL.

Figure 11: Zeta potential variation with temperature of different drilling fluid systems

Fig. 12 reveals a negative correlation between clay particle size and temperature exclusively in SS-1-modified samples, contrasting with the opposite trend observed in control groups. The median particle size (D50) of SS-1-treated clay decreases from 9.96 µm at 25°C to 5.06 µm at 220°C, indicating improved dispersion and reduced agglomeration at elevated temperatures. This phenomenon arises from three synergistic mechanisms: (1) Enhanced ionization of sulfonic groups at high temperatures strengthens electrostatic repulsion, promoting polymer chain extension; (2) Increased steric hindrance from expanded molecular chains forms thicker adsorption layers that prevent particle approach; (3) Elevated adsorption capacity exposes more anchoring sites, ensuring uniform particle surface coverage. Conversely, systems without SS-1 or with S-PAM exhibit significantly increased average particle sizes under thermal stress, indicating severe agglomeration due to S-PAM molecular degradation and chain scission above 200°C. These findings align with zeta potential measurements (Fig. 10), collectively demonstrating SS-1’s superior high-temperature stabilization capability.

Figure 12: Variation trend of average particle size D50 with temperature for different drilling fluid systems

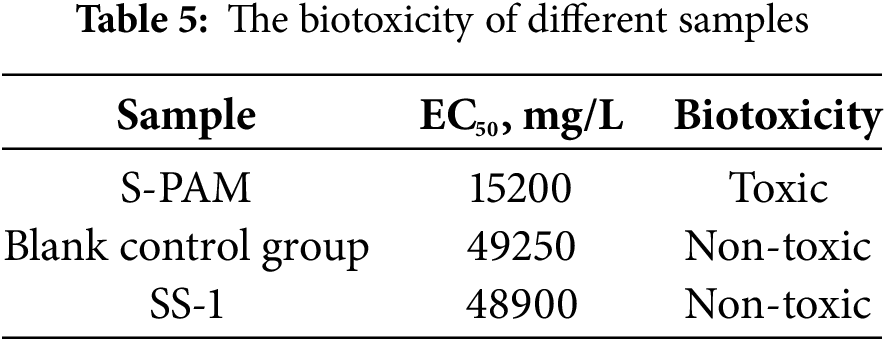

3.5 Biological Toxicity Analysis

The EC50 of SBDF was tested by the luminescent bacteria method according to the relative industry standard (Q/SY 111–2007, Garding and determination of the biotoxicity of chemicals and drilling fluids—Luminescent bacteria test) [33], and the results are listed in Table 5. The EC50 results of the three groups of samples are as follows: 15200 mg/L (S-PAM), 49250 mg/L (Blank control group),48900 mg/L(SS-1). According to the biological toxicity grade classification standard, when the EC50 was larger than 25000 mg/L, WBDF was nontoxic. If the EC50 exceeded 30000 mg/L, the emission standard was achieved [34]. Therefore, the experimental samples with the addition of SS-1 and the blank group were considered completely non-toxic. On the contrary, the samples with the addition of S-PAM were toxic and could not meet the environmental protection emission requirements, having certain limitations.

4 Conclusions and Recommendations

This study pioneers a hyperbranched amide polymer (SS-1) that effectively resolves barite sag in SBDFs under extreme conditions (>200°C). SS-1’s rigid-flexible architecture delivers temperature-responsive rheology, elevating plastic viscosity to 45 mPa·s and electrical stability to 1426 V after 210°C aging while achieving a record-low sag factor (0.509), outperforming commercial S-PAM by 4.1%. Mechanistically, synergistic electrostatic adsorption, spatial hindrance, and thermally activated chain extension (validated by 45% particle size reduction at 220°C) suppress sedimentation. With scalable synthesis (>82% yield) and environmental compliance, SS-1 establishes a new paradigm for ultra-deep well drilling stabilizers, with field trials targeting microstructure-resolved optimization.

Limitations and Future Work:

1. Subsurface simulation gap: Continuous dynamic evaluation under authentic temperature/pressure gradients (mimicking ultra-deep well conditions) is required to assess downhole performance.

2. Microstructural validation: Direct visualization of fluid-loss networks via microstructural scanning of field-condition drilling fluid formulations.

3. Conduct high-pressure shear experiments under appropriate reservoir conditions, and utilize the resulting rheological parameters to optimize the drilling fluid system. This approach minimizes construction costs and maximizes drilling efficiency.

Therefore, developing low-cost, high-tolerance polymer materials constitutes a critical research priority for addressing challenges in ultra-deep well drilling fluid technology. Future studies should focus on establishing structure-property relationships and a mechanistic understanding under reservoir conditions.

Acknowledgement: None.

Funding Statement: This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Project (No. 51804331, No. 51974354).

Author Contributions: Conceptualization, Qiang Sun, Zheng-Song Qiu; data curation, Tie Geng, Han-Yi Zhong; writing—original draft preparation, Weili Liu; formal analysis, Yu-Lin Tang; writing—review and editing, Jin-Cheng Dong. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Zhang GY, Ma F, Liang YB, Zhao Z, Qin YQ, Liu XB, et al. Domain and theory-technology progress of global deep oil & gas exploration. Acta Petrolei Sin. 2015;36(9):1156–66. (In Chinese). [Google Scholar]

2. Sun LD, Zou CN, Zhu RK, Zhang YH, Zhang SC, Zhang BM, et al. Formation, distribution and potential of deep hydrocarbon resources in China. Petrol Explor Dev. 2013;40(6):641–9. (In Chinese). doi:10.1016/s1876-3804(13)60093-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Zhang Y, Su G, Zheng L, Liu D, Guo Z, Wei P. The environmental friendliness of fuzzy-ball drilling fluids during their entire life-cycles for fragile ecosystems in coalbed methane well plants. J Hazard Mater. 2019;364:396–405. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.10.021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

4. Xin X, Yu G, Chen Z, Wu K, Dong X, Zhu Z. Effect of non-Newtonian flow on polymer flooding in heavy oil reservoirs. Polymers. 2018;10(11):1225. doi:10.3390/polym10111225. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Aftab A, Ismail AR, Ibupoto ZH, Akeiber H, Malghani MGK. Nanoparticles based drilling muds a solution to drill elevated temperature wells: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2017;76:1301–13. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2017.03.050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Karakosta K, Mitropoulos AC, Kyzas GZ. A review in nanopolymers for drilling fluids applications. J Mol Struct. 2021;1227:129702. doi:10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.129702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Ikram R, Jan BM, Vejpravova J. Towards recent tendencies in drilling fluids: application of carbon-based nanomaterials. J Mater Res Technol. 2021;15:3733–58. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.09.114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Li Q, de Viguerie L, Souprayen C, Casale S, Jaber M. Oil-based drilling fluid inspired by paints recipes. Appl Clay Sci. 2023;245:107120. doi:10.1016/j.clay.2023.107120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Wang X, Jin W, Li Y, Liu S, Xu J, Liu J, et al. Treatment advances of hazardous solid wastes from oil and gas drilling and production processes. Chem Eng J. 2024;497:154182. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.154182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Alves GM, Petri IJr. Microwave remediation of oil-contaminated drill cuttings—a review. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2021;207:109137. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2021.109137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Wang MG, Xu XG, Sun JS, Wang LH, Yang HJ, Wang BC. Study and application of additives for synthetic fluids with GTL as the base fluid. Drill Fluid Compl Fluid. 2016;33(3):30–34+40. (In Chinese). doi:10.3696/j.issn.1001-5620.2016.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Yan J, Liu YG. Research and application of new high temperature-resistance W/O emulsion drilling fluid system. Oilfield Chem. 2013;30(4):486–490+524. (In Chinese). doi:10.19346/j.cnki.1000-4092.2013.04.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Yanik S, Gucuyener IH, Sinayuc C, Akel OF. Rheological and PVT behavior of synthetic based drilling fluids under temperature-pressure conditions of the riser in deepwater drilling. In: International Petroleum Technology Conference; 2024 Feb 12; Dhahran, Saudi Arabia. London, UK: IPTC; 2024. IPTC-23968-MS. doi:10.2523/iptc-23968-ms. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Medhi S, Chowdhury S, Dehury R, Khaklari GH, Puzari S, Bharadwaj J, et al. Comprehensive review on the recent advancements in nanoparticle-based drilling fluids: properties, performance, and perspectives. Energy Fuels. 2024;38(15):13455–513. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c01161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Razali SZ, Yunus R, Abdul Rashid S, Lim HN, Mohamed Jan B. Review of biodegradable synthetic-based drilling fluid: progression, performance and future prospect. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2018;90:171–86. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang J, Dong T, Yi J, Jiang G. Development of multiple crosslinked polymers and its application in synthetic-based drilling fluids. Gels. 2024;10(2):120. doi:10.3390/gels10020120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Al-Ziyadi H, Pandian S, Verma A. Utilization of silica microfiber to enhance the rheological properties and fluid loss control of water-based drilling fluids. Energy Sources Part A Recov Util Environ Eff. 2025;47(1):5027–40. doi:10.1080/15567036.2025.2464952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Al-Ziyadi H, Kumar N, Verma A. Impact of hydroxypropyl guar polymer on rheology and filtration properties of water-based drilling fluids. Petroleum. 2025;11(3):320–33. doi:10.1016/j.petlm.2025.03.006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Razali SZ, Yunus R, Kania D, Rashid SA, Ngee LH, Abdulkareem-Alsultan G, et al. Effects of morphology and graphitization of carbon nanomaterials on the rheology, emulsion stability, and filtration control ability of drilling fluids. J Mater Res Technol. 2022;21:2891–905. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2022.10.097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Perumalsamy J, Gupta P, Sangwai JS. Performance evaluation of esters and graphene nanoparticles as an additives on the rheological and lubrication properties of water-based drilling mud. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2021;204:108680. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Koh JK, Lai CW, Johan MR, Gan SS, Chua WW. Recent advances of modified polyacrylamide in drilling technology. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2022;215:110566. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Cui X, Wang C, Huang W, Zhang S, Chen H, Wu B. Composite of carboxylized graphene oxide with nanosilica for shale plugging. J Phys Chem Solids. 2025;200:112574. doi:10.1016/j.jpcs.2025.112574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ismail AR, Aftab A, Ibupoto ZH, Zolkifile N. The novel approach for the enhancement of rheological properties of water-based drilling fluids by using multi-walled carbon nanotube, nanosilica and glass beads. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2016;139:264–75. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2016.01.036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Musa TA, Mohamed ES, Challiwala SM, Elbashir NO. Utilizing green-carbon nanotubes to improve drilling fluids rheological properties: an experimental study. In: SPE Annual Technical Conference and Exhibition; 2024 Sep 23–25; New Orleans, LA, USA. Houston, TX, USA: SPE; 2024. SPE-220697-MS. doi:10.2118/220697-ms. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Caminade AM, Beraa A, Laurent R, Delavaux-Nicot B, Hajjaji M. Dendrimers and hyper-branched polymers interacting with clays: fruitful associations for functional materials. J Mater Chem A. 2019;7(34):19634–50. doi:10.1039/c9ta05718h. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Kamel A, Shah SN. Effects of salinity and temperature on drag reduction characteristics of polymers in straight circular pipes. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2009;67(1–2):23–33. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2009.02.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Cheng J, Hou W, Luo W, Yu B, Song S, Rabbani MG. Preferred ratio and properties of microfoam drilling fluid for gas extraction in soft coal seams. Energy Fuels. 2024;38(11):9606–23. doi:10.1021/acs.energyfuels.4c00923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Liu Z, Wang ZH, Sun J, Su XX, Peng WY. Research and application process of branched polymers in oil chemistry. Appl Chem Ind. 2024;53(12):3011–5. (In Chinese). doi:10.16581/j.cnki.issn1671-3206.2024.12.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Ahmed A, Pervaiz E, Noor T. Applications of emerging nanomaterials in drilling fluids. ChemistrySelect. 2022;7(43):e202202383. doi:10.1002/slct.202202383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Rafati R, Smith SR, Sharifi Haddad A, Novara R, Hamidi H. Effect of nanoparticles on the modifications of drilling fluids properties: a review of recent advances. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2018;161:61–76. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2017.11.067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Li XL, Jiang GC, Xu Y, Deng ZQ, Wang K. A new environmentally friendly water-based drilling fluids with laponite nanoparticles and polysaccharide/polypeptide derivatives. Petrol Sci. 2022;19(6):2959–68. doi:10.1016/j.petsci.2022.07.003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang K, Hou Y, Cao H, Wang T, Li H, Wang T, et al. Eco-friendly utilization of oilfield fracturing flow-back fluid and coal pitch for preparing slurry: experiments and extended DLVO study. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2022;216:110786. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2022.110786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Ma XY, Wang XC, Ngo HH, Guo W, Wu MN, Wang N. Bioassay based luminescent bacteria: interferences, improvements, and applications. Sci Total Environ. 2014;468-469:1–11. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.08.028. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Yang X, Shang Z, Liu H, Cai J, Jiang G. Environmental-friendly salt water mud with nano-SiO2 in horizontal drilling for shale gas. J Petrol Sci Eng. 2017;156:408–18. doi:10.1016/j.petrol.2017.06.022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools