Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Direct Production of Sorbitol-Plasticized Bioplastic Film from Gracilaria sp.

1 Department of Mechanical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, University of Lampung, Prof. Dr. Sumantri Brojonegoro Street No. 1, Gedong Meneng, Bandar Lampung, 35145, Indonesia

2 Research Center for Biomass and Bioproducts, National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN), Jl. Raya Puspiptek 60, 15314, Tangerang Selatan, Indonesia

3 Department of Chemistry, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia, Jl. Dr. Setiabudi No. 229, Sukasari, Bandung, 40154, Indonesia

* Corresponding Author: Yeyen Nurhamiyah. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Development and Application of Biodegradable Plastics)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(3), 743-755. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.069981

Received 04 July 2025; Accepted 12 August 2025; Issue published 30 September 2025

Abstract

Conventional bioplastic production from seaweed often relies on extraction processes that are costly, time-consuming, and yield limited product. This study presents a direct fabrication method using Gracilaria sp., a red seaweed rich in polysaccharides, to produce bioplastic films without the need for extraction. Sorbitol was incorporated as a plasticizer at concentrations of 0%–10% (w/w) to modify film characteristics. Thermal analysis revealed improved stability at moderate sorbitol levels (5%–7%), while excessive plasticizer slightly reduced thermal resistance. Mechanical testing showed that sorbitol increased film flexibility and elongation at break, though tensile strength and stiffness declined. Tear strength followed a non-linear trend, with improvement observed at higher sorbitol concentrations. Seal strength also increased, peaking at 7%, indicating stronger interfacial bonding between film layers. Biodegradation tests demonstrated accelerated decomposition with increased sorbitol content, achieving complete degradation within 30 days at 10% concentration. Color analysis showed increased brightness and reduced yellowing, enhancing the visual quality of the films. These results confirm that direct conversion of bioplastic is both feasible and effective. Sorbitol plays a key role in tuning film properties, offering a low-cost, scalable pathway to biodegradable materials suitable for environmentally friendly packaging applications.Keywords

The persistent accumulation of synthetic plastic waste has emerged as a critical global concern, primarily due to the non-biodegradable nature of petroleum-based polymers. Their widespread use in packaging, agriculture, and consumer products has led to long-term environmental persistence and ecological disruption. Considering growing environmental awareness and stricter waste management policies, the development of biodegradable polymers from renewable sources has gained significant attention. Among the various candidates, bioplastics derived from marine biomass, particularly macroalgae, have shown promise due to their abundant availability and rapid renewability [1].

Gracilaria sp., a red seaweed rich in polysaccharides such as agar and carrageenan, is a potential raw material for bioplastic production. Unlike land-based feedstocks, seaweed cultivation does not require arable land, freshwater, or chemical fertilizers, and offers high biomass yield with minimal ecological input. This makes seaweed a sustainable and low-carbon alternative for plastic film sourcing [2]. Typically, bioplastic production from seaweed involves the extraction of specific hydrocolloids through chemical or enzymatic treatment prior to film formation. However, these extraction processes are energy-intensive, time-consuming, and yield relatively small quantities of purified product, thereby increasing production costs and limiting scalability [3].

To address these limitations, direct fabrication methodsutilizing whole, minimally processed seaweed biomass have been proposed. The importance of direct seaweed production has been explored in previous studies, though with varying methods and outcomes. For instance, Hanry & Suruguru successfully produced bioplastic directly from whole Kappaphycus sp. biomass without chemical extraction [4]. The resulting films exhibited complete biodegradability within 15 days, highlighting their potential as an eco-friendly plastic alternative. Meanwhile, Sudhakar et al. (2020) developed and characterized biodegradable films using whole biomass of the red seaweed Kappaphycus alvarezii. The films showed favorable mechanical properties and water solubility, making them promising candidates for eco-friendly packaging applications [5]. Previous research has explored the direct utilization of Gracilaria biomass for bioplastic film development. For instance, Tarangini et al. successfully fabricated flexible and homogeneous films from Gracilaria edulis combined with starch and chitosan, while Premondasa et al. demonstrated that Gracilaria verrucosa could be used to produce edible straws with high antioxidant activity and biodegradability [6,7].

Plasticizers are commonly used to improve the flexibility, ductility, and workability of biopolymer films. Among various plasticizers, Sorbitol is a polyol derived from glucose that is widely recognized for its plasticizing effect. Sorbitol is non-toxic, hydrophilic, and forms hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl-rich polysaccharides, making it well-suited for seaweed-based matrices [8]. Previous studies have shown that sorbitol improves film flexibility and transparency, while also accelerating microbial degradation by increasing matrix accessibility. A recent study by Khan et al. demonstrated that kappa carrageenan-based films from Gracilaria sp. plasticized with sorbitol exhibited enhanced tensile properties and biodegradability [9].

Therefore, the objective of this study is to develop bioplastic films directly from Gracilaria sp. without undergoing prior extraction, and to evaluate the effects of different sorbitol concentrations (0%–10% w/w) on the films’ thermal, mechanical, barrier, optical, and chemical properties. A combination of analytical techniques—including Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, thermogravimetric analysis (TGA), and mechanical testing—was employed to characterize the interactions and performance of the films. The results of this work aim to provide a cost-effective and scalable strategy for producing seaweed-based bioplastics suitable for environmentally friendly packaging and related applications.

The primary material used in this study was Gracilaria sp., obtained from coastal areas of Karawang, Indonesia (Fig. 1). Distilled water (H2O) and liquid sorbitol were purchased from a commercial online marketplace, while sodium hydroxide (NaOH) was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich (Burlington, MA, USA).

Figure 1: Photographs of Dried Gracilaria sp. collected from the coastal area of Karawang, Indonesia (right) and bioplastic films made from Gracilaria sp. using direct production method with increasing sorbitol concentrations (0%–10% w/w) (left)

The raw Gracilaria sp. biomass was first thoroughly washed with tap water to remove sand, salts, and other impurities. It was then oven-dried at 60°C for 12–14 h to reduce the moisture content. A total of 2 g of the dried seaweed was weighed and subjected to a bleaching process by soaking it in 200 mL of a 2% sodium hydroxide (NaOH) solution. This treatment, conducted for 1 h at room temperature, aimed to remove pigments and residual organic matter. After bleaching, the seaweed was rinsed repeatedly with distilled water until a neutral pH (pH 7) was achieved, ensuring complete removal of the alkali. The treated biomass was then used directly in the film fabrication process without further extraction.

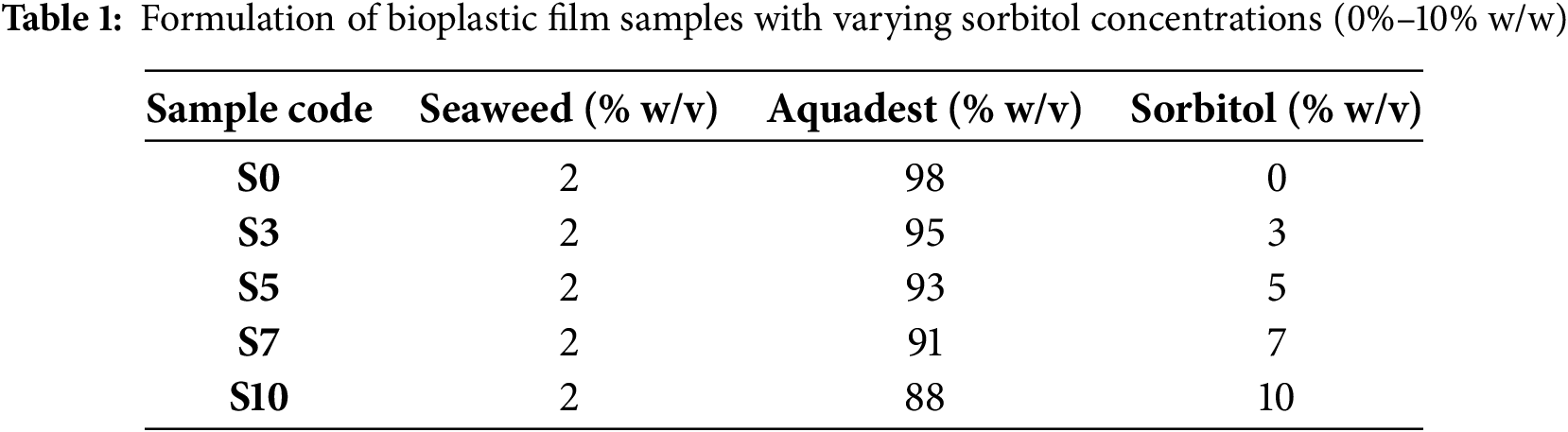

Bioplastic films were prepared based on the formulations described in Table 1. The pretreated Gracilaria sp. was placed in a glass container and mixed with 100 mL of distilled water. To extract native polysaccharides, the mixture was subjected to thermal treatment using an autoclave at 100°C for 15 min. This process facilitated the breakdown of seaweed cell walls and the release of water-soluble polysaccharides into the solution. After autoclaving, the slurry was homogenized using a hand blender for 5 min and filtered through a 200-mesh sieve to remove insoluble residues. The resulting filtrate was then mixed with liquid sorbitol at concentrations ranging from 0% to 10% (w/w). The solution was reheated to 90°C and stirred continuously for 15 min to ensure uniform dispersion of the plasticizer. The final mixture was poured into silicone molds and dried in an oven at 60°C for 12–14 h. Once dried, the bioplastic films were carefully peeled and stored in sealed polyethylene bags at room temperature prior to further characterization. The experimental steps for bioplastic film preparation and characterization are presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Flowchart of the experimental procedure used for bioplastic film preparation and characterization

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR)

FTIR characterization was performed using fourier transform infrared spectroscopy which aims to identify the type of functional group bonds. FTIR spectra were recorded using a Perkin Elmer Spectrum 100 spectrometer (Shelton, CT, USA) in transmittance mode, with a resolution of 4 cm−1 in the range of 400–4500 cm−1, and an average of 16 scans was accumulated.

Thermal Properties

Thermal stability was evaluated using a Perkin Elmer TGA 4000 thermogravimetric analyzer. The samples were heated from 25°C to 500°C at a heating rate of 10°C/min.

Tensile Properties

Tensile properties were evaluated using a Universal Testing Machine (UTM), Shimadzu AGS-X Series (Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a 5 kN load cell. Bioplastic films were cut into rectangular specimens with dimensions of 6 cm × 1 cm. The test was conducted in accordance with ASTM D882 standard for the tensile properties of thin plastic sheeting. Specimens were mounted vertically between pneumatic grips, and tensile force was applied at a constant crosshead speed of 10 mm/min.

Tear Strength

Tear strength was measured according to ISO 34-1:2015 Method A using Type T (trouser) test pieces. The specimens were die-cut from the material using a standardized cutter to produce uniform trouser-shaped samples. Prior to testing, all samples were conditioned at 23 ± 2°C and 50 ± 5% relative humidity for at least 16 h. At least five replicates were prepared, and specimens were stored in sealed plastic bags to avoid contamination or moisture loss.

Seal Strength

Seal strength was evaluated by preparing heat seals using a German-made HSG/ETK model heat sealer. Two layers of film were clamped between flat metal sealing jaws, each 10 mm in width. The device allows precise adjustment of sealing temperature, pressure, and dwell time, ensuring consistent and reproducible seal formation. A microprocessor-controlled system maintains and displays the temperature of each sealing bar in real time. After sealing, the specimens were tested using a UTM Shimadzu AGS-X Series. Each sample was mounted vertically in a T-peel configuration, with the unsealed ends clamped securely in the upper and lower grips of the machine. Care was taken to align the sealed area at the center of the gripping axis to ensure even load distribution. The test was performed according to ASTM F88/F88M-15 standard method for seal strength of flexible barrier materials, using a constant crosshead speed of 10 mm/min. The maximum force required to peel the seal was recorded as the seal strength.

Biodegradation Measurement

Specimens measuring 4 cm × 4 cm were buried at a depth of 5 cm in soil under ambient conditions for a period of 30 days. Visual observations and weight measurements were conducted every 10 days to monitor the degradation process. The percentage of biodegradation was calculated based on the initial and final dry weight of each sample using the following equation:

where Wi is the initial weight (g) and Wf is the final weight (g).

Color Test

Color measurements of the samples were conducted using a ColorFlex spectrophotometer (HunterLab, Reston, VA, USA). Prior to measurement, the instrument was calibrated using a standard white calibration tile with reference values of L = 94.20*, a = 1.09*, and b = 2.55*. Measurements were performed under standardized lighting conditions, and results were expressed in the CIE Lab* color space, where L* indicates lightness (0 = black, 100 = white), a* represents the red-green axis (positive values indicate redness, negative values indicate greenness), and b* represents the yellow-blue axis (positive values indicate yellowness, negative values indicate blueness). Each sample was measured in triplicate, and the average values were reported.

The FTIR spectra of seaweed-based bioplastics with varying concentrations of sorbitol (S0–S10) were analyzed to identify the functional groups and assess the interactions between the polymer matrix and the plasticizer. The FTIR spectra are depicted in Fig. 3. All samples exhibited a broad absorption band in the range of 3200–3300 cm−1, indicative of the O–H stretching vibration associated with the hydroxyl groups in the polysaccharide framework derived from Gracilaria sp. and sorbitol [10]. The intensity of this peak increased with the addition of sorbitol, suggesting a higher concentration of hydroxyl groups and enhanced hydrogen bonding between sorbitol and the seaweed matrix [11]. However, the addition of sorbitol also shifted the wavenumber within the 3200–3300 cm−1 range. This shift suggests that sorbitol disrupts the hydrogen bonding between the molecules in the seaweed matrix, likely due to its plasticizing effect, which weakens the intermolecular interactions [12]. Additionally, the band at 2900 cm−1, corresponding to C–H stretching vibrations of the aliphatic chain, became more prominent as sorbitol concentration increased. This is consistent with the molecular structure of sorbitol, which contains multiple CH groups, as well as the polysaccharide matrix that also exhibits C–H stretching vibrations from its sugar components [13].

Figure 3: FTIR spectra of seaweed-based bioplastics with varying sorbitol concentrations (0%–10%)

The absorption observed near 1650 cm−1 is ascribed to C=O stretching, likely originating from carboxylic or ester groups inherent in seaweed polysaccharides [14]. The peak exhibits stability across all sorbitol concentrations, suggesting that the core structure of the biopolymer is not substantially modified by the plasticizer. The bands observed in the 1000–1020 cm−1 region are associated with C–O and C–OH stretching vibrations, with intensity markedly increasing as sorbitol content rises. This indicates significant interactions and potential molecular entanglement between the seaweed matrix and sorbitol molecules [12]. The FTIR results confirm the effective incorporation of sorbitol as a plasticizer. Elevating the sorbitol concentration leads to enhanced intensities of aliphatic and hydroxyl C–H signals, indicating the plasticizer’s role in the molecular structure and its potential to enhance the flexibility and mechanical properties of the resultant bioplastic.

Fig. 4 illustrates the thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) curves for seaweed-based bioplastics with different concentrations of sorbitol plasticizer: S0 (0%), S3 (3%), S5 (5%), S7 (7%), and S10 (10%). All samples demonstrated a comparable two-step degradation pattern. The initial weight loss, observed below 150°C, was ascribed to the evaporation of water and low molecular weight volatiles. The second significant degradation phase, occurring between roughly 250°C and 370°C, is associated with the thermal decomposition of the polymer matrix, which mainly consists of polysaccharides derived from seaweed and the incorporated sorbitol [15].

Figure 4: TGA curves of seaweed-based bioplastics with varying sorbitol concentrations (0%–10%)

The control sample, S0 (0% sorbitol), demonstrated an earlier onset of degradation and a greater total weight loss relative to the plasticized samples, suggesting that the addition of sorbitol improves the thermal stability of the bioplastic. S5 and S7 exhibited the greatest thermal resistance among the plasticized samples, indicating that optimal interactions between the seaweed matrix and sorbitol are achieved at these concentrations. These findings align with previous research, including that of [16], which noted increased thermal stability in bioplastics containing low-to-moderate levels of plasticizers such as sorbitol, leading to enhanced interactions within the polymer matrix. At 10% sorbitol (S10), a minor reduction in thermal stability was observed, potentially attributable to an excess of plasticizer, which may result in phase separation or reduced polymer-polymer interactions.

At a final temperature of 500°C, the residual mass was highest for the sample without sorbitol (S0), with approximately 40% char remaining, indicating that the absence of sorbitol promotes greater char formation and results in a more thermally stable residue. In contrast, as the sorbitol content increased (S3, S5, S7, S10), the residual mass decreased, suggesting that sorbitol acts as a plasticizer. This plasticizing effect can promote earlier decomposition of the bioplastic at lower temperatures, reducing the amount of char formed [12,17]. As a result, higher sorbitol content leads to less char formation, which may impact the flame retardancy of the material and potentially reduce thermal stability compared to the sorbitol-free sample.

Fig. 5 displays the results of the tensile test. The tensile strength demonstrated a decreasing trend as sorbitol content increased, reaching a maximum at 0% sorbitol (31 MPa) and declining significantly at elevated concentrations. Elastic modulus exhibited an inverse correlation with elongation, showing a significant decrease at 3% sorbitol, followed by a gradual increase from 5% to 10%, suggesting enhanced stiffness at elevated sorbitol concentrations. The findings indicate that sorbitol functions as a plasticizer, improving the flexibility of the bioplastic matrix to an optimal concentration, after which mechanical strength and ductility decline due to potential phase separation or oversaturation effects.

Figure 5: (a) Tensile strength, (b) modulus elasticity, and (c) elongation at break of seaweed based plastic film with various sorbitol composition

In contrast, elongation at break significantly increased with the incorporation of sorbitol, peaking at 3% sorbitol (57%) before gradually declining with higher sorbitol concentrations. At 3% sorbitol, the increase in elongation suggests improved flexibility, as sorbitol interferes with intermolecular hydrogen bonds, facilitating greater mobility of the polymer chains. Further increases in sorbitol beyond 3% resulted in a reduction in elongation, likely attributable to matrix saturation, which may lead to phase separation or recrystallization of sorbitol within the bioplastic structure. The trend in the elastic modulus corroborates this interpretation, with the lowest stiffness observed at 3% sorbitol, indicating maximum flexibility, followed by a gradual increase at higher concentrations. This indicates that an excess of sorbitol starts to negate the plasticizing effect, resulting in a slight increase in the stiffness of the matrix.

Tensile testing demonstrated that sorbitol concentration significantly affected the mechanical properties of seaweed-based bioplastics. The findings are consistent with recent research on seaweed-derived bioplastics [18]. Research by [19] indicated that incorporating sorbitol into carrageenan-based films improved elongation while decreasing tensile strength, aligning with our findings. A study by [20] examined the effects of different plasticizers on seaweed hydrocolloid bioplastics. The findings indicated that plasticizers such as sorbitol enhanced elongation but reduced tensile strength, supporting our observations.

Fig. 6 presents the tear strength of seaweed-based bioplastics across different concentrations of sorbitol (S0–S10). The tear strength exhibited a decline as sorbitol content increased from 0% to 3%, reaching its minimum at 3% sorbitol (1.11 MPa). The decrease in tear strength can be ascribed to the plasticizing effect of sorbitol, which increases the flexibility of the bioplastic while concurrently diminishing its tear resistance. At 5% sorbitol (1.77 MPa) and 7% sorbitol (1.06 MPa), the tear strength exhibited a slight increase, suggesting a potential re-establishment of polymer cohesion as the sorbitol concentration is maintained within an optimal range.

Figure 6: Tear strength of seaweed-based bioplastics with varying concentrations of sorbitol plasticizer (S0–S10)

The most significant increase in tear strength occurred at 10% sorbitol (2.91 MPa), indicating that higher concentrations of sorbitol may enhance cohesion among polymer chains, likely due to improved molecular entanglement or interactions induced by the plasticizer. The observed increase in tear strength at 10% sorbitol contradicts the common assumption that elevated plasticizer concentrations diminish mechanical strength. The phenomenon can be attributed to the enhanced dispersion of the plasticizer, resulting in more uniform molecular interactions within the polymer matrix, thereby improving overall tear resistance.

The findings align with recent research regarding plasticizers in bioplastics. Ref. [21] found that adding plasticizers like sorbitol to polysaccharide-based bioplastics typically enhances flexibility while diminishing mechanical strength at elevated concentrations. They observed a peak in mechanical properties, including tear strength, at elevated plasticizer concentrations, consistent with our findings for the 10% sorbitol concentration. Ref. [22] observed a comparable trend in seaweed-based bioplastics, indicating that the incorporation of sorbitol beyond a specific concentration led to increased tear strength attributed to enhanced molecular interaction, rather than mere plasticization.

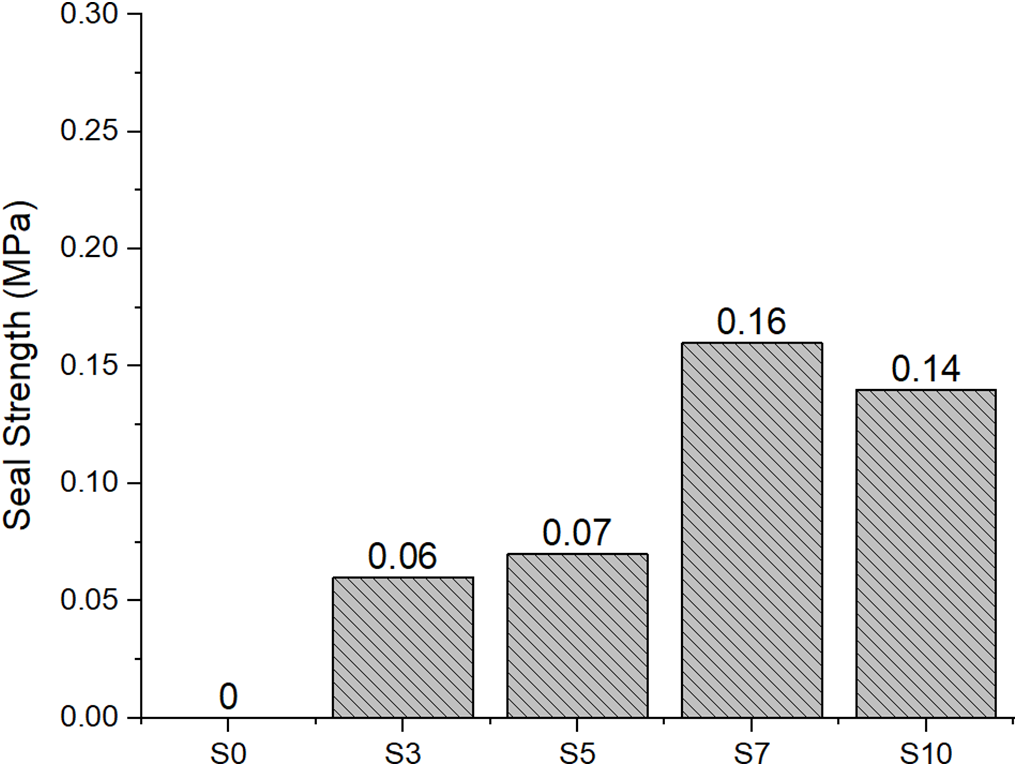

Fig. 7 displays the seal strength (MPa) of seaweed-based bioplastics across different concentrations of sorbitol plasticizer (S0–S10). The data indicates a distinct trend where seal strength rises with increasing sorbitol concentration until an optimal level is reached, after which a minor decline occurs at elevated sorbitol levels. At 0% sorbitol (S0), the seal strength measures 0 N/mm, demonstrating that the bioplastic, in its unmodified form, does not possess adequate cohesion to establish a functional seal. The incorporation of sorbitol leads to an increase in seal strength, achieving 0.06 N/mm at 3% sorbitol (S3) and 0.07 N/mm at 5% sorbitol (S5). This increase indicates that sorbitol functions as a plasticizer, enhancing molecular interaction and improving sealing performance [23].

Figure 7: Seal strength of seaweed-based bioplastics with varying concentrations of sorbitol plasticizer (S0–S10)

The highest enhancement in seal strength is observed at 7% sorbitol (S7), achieving a seal strength of 0.16 MPa. This is likely attributable to the optimal balance between the plasticizing effect of sorbitol and the cohesive interactions within the polymer matrix. At a concentration of 10% sorbitol (S10), a minor reduction in seal strength is noted, measuring 0.14 MPa. The reduction can be attributed to excess plasticizer, which causes oversaturation of the matrix, resulting in weaker polymer-polymer interactions or phase separation due to increased flexibility of the material.

The observed trends are consistent with the findings of [24], which indicate that plasticizer concentration has a significant impact on the seal strength of bioplastics. Their research indicated a comparable trend, revealing that bioplastics with moderate plasticizer concentrations achieved optimal seal strength, whereas an excess of plasticizer resulted in diminished mechanical performance attributed to phase separation and cohesion loss. Ref. [21] found that the optimal concentration of plasticizer in polysaccharide-based bioplastics enhances seal strength, especially with sorbitol at 5%–7%. Beyond this range, increasing plasticizer content results in decreased seal strength.

Fig. 8 shows the percentage weight loss of seaweed-based bioplastics with different concentrations of sorbitol plasticizer (S0–S10) throughout the biodegradation process. The data demonstrates a clear trend indicating that weight loss increases with higher sorbitol concentrations, suggesting that sorbitol significantly enhances the biodegradability of bioplastics. At 0% sorbitol (S0), the weight loss is minimal (21.62%), suggesting limited biodegradation without the presence of a plasticizer. The absence of a plasticizer leads to a more rigid matrix, potentially impeding microbial degradation. With an increase in sorbitol concentration, there is a notable rise in weight loss. At 3% sorbitol (S3), weight loss is 81.77%, which increases further, with nearly complete degradation (100%) observed at 10% sorbitol (S10). The inclusion of sorbitol appears to improve the flexibility and vulnerability of the bioplastic matrix to microbial degradation, thereby accelerating the biodegradation process.

Figure 8: Weight loss (%) of seaweed-based bioplastics with varying concentrations of sorbitol plasticizer (S0–S10) during degradation

These findings are consistent with prior research on plasticizers in bioplastics. One study reported that the biodegradation rate of polysaccharide-based bioplastics significantly increased with the incorporation of sorbitol [25]. Plasticizers like sorbitol disrupt intermolecular interactions within the polymer matrix, weakening the structure and making it easier for microorganisms to break down the material. Another study observed a positive correlation between the biodegradation rate of seaweed-based bioplastics and the content of plasticizers [26]. Their study demonstrated that sorbitol, functioning as a plasticizer, significantly enhanced the biodegradation of seaweed-derived bioplastics, particularly at elevated concentrations. This aligns with our results, which showed that 10% of sorbitol led to complete degradation.

The enhancement of biodegradation at elevated sorbitol concentrations is likely due to the plasticizing effect, which reduces the crystallinity and rigidity of the bioplastic, facilitating greater penetration and degradation by microorganisms [27]. Optimizing sorbitol content is essential for improving the environmental performance of bioplastics. It is important to note that an increase in sorbitol content enhances the biodegradation rate; however, excessive concentrations of plasticizers may compromise mechanical properties, as evidenced by the tensile and tear strength results. The trade-off between biodegradability and mechanical performance underscores the necessity for precise formulation of bioplastics tailored to specific applications.

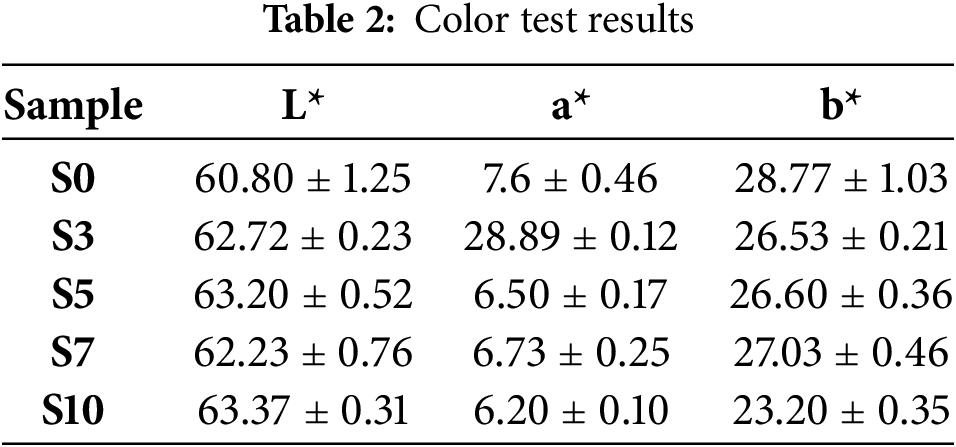

The impact of sorbitol concentration on the color properties of seaweed-based bioplastic films was assessed using instrumental color measurements. As outlined in Table 2, the samples were labeled from S0 to S10, corresponding to increasing sorbitol concentrations of 0%, 3%, 5%, 7%, and 10%, respectively. For each sample, three types of color measurements were taken: L* (brightness), a* (red-green axis), and b* (yellow-blue axis), with each measurement repeated three times to ensure reliability.

The brightness (L)* values showed a clear increase with higher sorbitol content, indicating that the films became visually brighter as the concentration of sorbitol increased. The L* value for S0 was 60.80 ± 1.25, while S10 exhibited the highest brightness value at 63.37 ± 0.31. This trend suggests that sorbitol may enhance the transparency or brightness of the bioplastic films, potentially by altering the microstructure or influencing light scattering properties within the polymer matrix.

The a values* (red-green axis) remained relatively stable across all sorbitol concentrations, with only minor fluctuations observed. For example, S0 had an a* value of 7.60 ± 0.46, while S10 showed a slightly lower a* value of 6.20 ± 0.10. This slight decrease in the red hue with increasing sorbitol content indicates that higher plasticizer concentrations could reduce the intensity of the red component of the bioplastic films, although the effect was minimal [28].

The b values* (yellow-blue axis) exhibited a general decreasing trend with increasing sorbitol concentrations. For instance, the b* value decreased from 28.77 ± 1.03 for S0 to 23.20 ± 0.35 for S10. This reduction in yellowness could be attributed to changes in the composition of the bioplastic films, alterations in moisture retention, or interactions between sorbitol and the pigment components in the seaweed matrix. This suggests that sorbitol may affect the color balance of the films by reducing their yellow tone as the concentration of sorbitol increases [29].

This study demonstrates the feasibility of producing from autoclaved suspensions of Gracilaria sp. powder, without requiring prior chemical extraction steps, offering a simpler and more efficient alternative to conventional methods. The incorporation of sorbitol significantly influenced the films’ thermal, mechanical, barrier, and degradation properties. Moderate sorbitol levels (5%–7%) enhanced thermal stability and seal strength, while lower levels improved flexibility and elongation. At 10% sorbitol, complete biodegradation was achieved within 30 days, indicating excellent environmental compatibility. Visual improvements, such as increased brightness and reduced yellowing, were also observed. Overall, direct seaweed utilization combined with sorbitol plasticization provides a cost-effective and scalable approach for developing biodegradable films suitable for sustainable packaging applications.

We demonstrated that bioplastic films can be produced directly from autoclaved suspensions of Gracilaria sp. powder, without requiring prior chemical extraction steps.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by IAEA Coordinated Research Project F22081.

Author Contributions: Ahmad Faldo: Methodology; Investigation; Data curation; Formal analysis; Visualization; Writing—original draft; Labanta Marbun: Software; Investigation; Data curation; Hezekiah Lemuel Putra Zebua: Software; Visualization; Data logging; Fateha Fateha: Conceptualization; Resources; Sample preparation; Rossy Choerun Nissa: Conceptualization; Resources; Supervision; Yurin Karunia Apsha Albaina Iasya: Literature review; Writing—review & editing; Riri Uswatun Annifah: Literature review; Writing—review & editing; Amrul Amrul: Validation; Supervision; Critical feedback; Yeyen Nurhamiyah: Conceptualization; Supervision; Funding acquisition; Writing—review & editing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: Data available on request from the authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Lim C, Yusoff S, Ng CG, Lim PE, Ching YC. Bioplastic made from seaweed polysaccharides with green production methods. J Environ Chem Eng. 2021;9(5):105895. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2021.105895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Sharma R, Mondal AS, Trivedi N. Bioplastic from seaweeds: current status and future perspectives. In: Trivedi N, Reddy CRK, Critchley AT, editors. Recent advances in seaweed biotechnology. Singapore: Springer Nature, 2025. p. 413–24. doi:10.1007/978-981-96-0519-4_16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Krishnan L, Ravi N, Kumar Mondal A, Akter F, Kumar M, Ralph P, et al. Seaweed-based polysaccharides—review of extraction, characterization, and bioplastic application. Green Chem. 2024;26(10):5790–823. doi:10.1039/d3gc04009g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Hanry EL, Surugau N. Characterization of bioplastics developed from whole seaweed biomass (Kappaphycus sp.) added with commercial sodium alginate. J Appl Phycol. 2024;36(2):907–16. doi:10.1007/s10811-023-03095-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Sudhakar MP, Magesh Peter D, Dharani G. Studies on the development and characterization of bioplastic film from the red seaweed (Kappaphycus alvarezii). Environ Sci Pollut Res. 2021;28(26):33899–913. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-10010-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Tarangini K, Huthaash K, Nandha Kumar V, Kumar ST, Jayakumar OD, Wacławek S, et al. Eco-friendly bioplastic material development via sustainable seaweed biocomposite. Ecol Chem Eng S. 2023;30(3):333–41. doi:10.2478/eces-2023-0036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Premadasa SR, Jayapala HPS, Rathnasri PASA, Jayasingha PS, Lim SY. Nutritive enriched edible, bioplastic straw from red seaweed, Gracilaria verrucosa as an effort application of marine resources for health. Edelweiss Appl Sci Technol. 2024;8(6):7167–77. doi:10.55214/25768484.v8i6.3534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Tian H, Liu D, Yao Y, Ma S, Zhang X, Xiang A. Effect of sorbitol plasticizer on the structure and properties of melt processed polyvinyl alcohol films. J Food Sci. 2017;82(12):2926–32. doi:10.1111/1750-3841.13950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Khan NM, Chakma P, Uddin MS, Monirul Hasan CM. Preparation and characterization of biodegradable plastic from red seaweed (Gracilaria sp.) from coastal areas in Bangladesh. ChemistrySelect. 2024;9(34):e202401990. doi:10.1002/slct.202401990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Malle D, Fransina EG, Jansen F. Extraction and identification of sulfated polysaccharide from Gracilaria sp. Indo J Chem Res. 2014;1(2):83–7. doi:10.30598/ijcr.2014.1-dom. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Mohammed A, Gaduan A, Chaitram P, Pooran A, Lee KY, Ward K. Sargassum inspired, optimized calcium alginate bioplastic composites for food packaging. Food Hydrocoll. 2023;135(1):108192. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Ma X, Qiao C, Zhang J, Xu J. Effect of sorbitol content on microstructure and thermal properties of chitosan films. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;119:1294–7. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.08.060. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Ng JS, Kiew PL, Lam MK, Yeoh WM, Ho MY. Preliminary evaluation of the properties and biodegradability of glycerol- and sorbitol-plasticized potato-based bioplastics. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2022;19(3):1545–54. doi:10.1007/s13762-021-03213-5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Gómez-Ordóñez E, Rupérez P. FTIR-ATR spectroscopy as a tool for polysaccharide identification in edible brown and red seaweeds. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25(6):1514–20. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.02.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Cassani L, Lourenço-Lopes C, Barral-Martinez M, Chamorro F, Garcia-Perez P, Simal-Gandara J, et al. Thermochemical characterization of eight seaweed species and evaluation of their potential use as an alternative for biofuel production and source of bioactive compounds. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(4):2355. doi:10.3390/ijms23042355. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Santana I, Felix M, Bengoechea C. Seaweed as basis of eco-sustainable plastic materials: focus on alginate. Polymers. 2024;16(12):1662. doi:10.3390/polym16121662. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zahiruddin SMM, Othman SH, Tawakkal ISMA, Talib RA. Mechanical and thermal properties of tapioca starch films plasticized with glycerol and sorbitol. Food Res. 2018;3(2):157–63. doi:10.26656/fr.2017.3(2).105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Rosmawati R, Sari SF, Asnani A, Embe W, Asjun A, Wibowo D, et al. Influence of sorbitol and glycerol on physical and tensile properties of biodegradable-edible film from snakehead gelatin and κ-carrageenan. Int J Food Sci. 2025;2025(1):7568352. doi:10.1155/ijfo/7568352. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Rahmawati M, Arief M, Satyantini WH. The effect of sorbitol addition on the characteristic of carrageenan edible film. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2019;236(1):012129. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/236/1/012129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Budiman MA, Uju, Tarman K. A Review on the difference of physical and mechanical properties of bioplastic from seaweed hydrocolloids with various plasticizers. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2022;967(1):012012. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/967/1/012012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Harussani MM, Sapuan SM, Firdaus AM, El-Badry YA, Hussein EE, El-Bahy ZM. Determination of the tensile properties and biodegradability of cornstarch-based biopolymers plasticized with sorbitol and glycerol. Polymers. 2021;13(21):3709. doi:10.3390/polym13213709. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Mohammed AABA, Hasan Z, Omran AAB, Elfaghi AM, Khattak MA, Ilyas RA, et al. Effect of various plasticizers in different concentrations on physical, thermal, mechanical, and structural properties of wheat starch-based films. Polymers. 2022;15(1):63. doi:10.3390/polym15010063. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Abdorreza MN, Cheng LH, Karim AA. Effects of plasticizers on thermal properties and heat sealability of sago starch films. Food Hydrocoll. 2011;25(1):56–60. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2010.05.005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Tan SX, Andriyana A, Ong HC, Lim S, Pang YL, Ngoh GC. A comprehensive review on the emerging roles of nanofillers and plasticizers towards sustainable starch-based bioplastic fabrication. Polymers. 2022;14(4):664. doi:10.3390/polym14040664. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Azizati Z, Afidin IMZ, Hasnowo LA. The effect of sorbitol addition in bioplastic from cellulose acetate (sugarcane bagasse)-chitosan. Walisongo J Chem. 2022;5(1):94–101. doi:10.21580/wjc.v5i1.12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Gapsari F, Putri TM, Rukmana W, Juliano H, Sulaiman AM, Dewi FGU, et al. Isolation and characterization of Muntingia Calabura cellulose nanofibers. J Nat Fibres. 2023;20(1):2156018. doi:10.1080/15440478.2022.2156018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Arief MD, Mubarak AS, Pujiastuti DY. The concentration of sorbitol on bioplastic cellulose based carrageenan waste on biodegradability and mechanical properties bioplastic. IOP Conf Ser Earth Environ Sci. 2021;679(1):012013. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/679/1/012013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Haq MA, Jafri FA, Hasnain A. Effects of plasticizers on sorption and optical properties of gum cordia based edible film. J Food Sci Technol. 2016;53(6):2606–13. doi:10.1007/s13197-016-2227-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Schnabl KB, Mandemaker LDB, Ganjkhanlou Y, Vollmer I, Weckhuysen BM. Green additives in chitosan-based bioplastic films: long-term stability assessment and aging effects. ChemSusChem. 2024;17(13):e202301426. doi:10.1002/cssc.202301426. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools