Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Influence of Honey on Structural, Morphology and Thermal Behavior of Zein-Based Polymer Systems

1 Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

2 Turning Trash to Treasure Laboratory (TTTL), Research and Development Center, University of Sulaimani, Qlyasan Street, Sulaymaniyah, 46001, Iraq

3 Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

4 Centre for Foundation Studies in Science, Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

5 Universiti Malaya Centre for Ionic Liquids (UMCiL), Universiti Malaya, Kuala Lumpur, 50603, Malaysia

* Corresponding Author: Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 1111-1123. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.070939

Received 28 July 2025; Accepted 08 December 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

This study investigates the effects of honey concentration on the crystallinity, morphology, and thermal behavior of zein-based polymer systems, aiming to assess honey’s role as a natural plasticizer. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis confirmed the presence of strong intermolecular interactions and hydrogen bonding between zein and honey, indicating good miscibility. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns revealed a significant reduction in crystallinity with increasing honey concentration up to 25 wt.%, with the ZH5 (75 wt.% zein-25 wt.% honey) sample exhibiting the smallest crystallite size (4.23 nm), suggesting enhanced amorphous character suitable for ionic mobility. Field emission scanning electron micrograph (FESEM) images of ZH5 displayed a homogeneous porous-fiber-like morphology, while excess honey beyond 25 wt.% led to agglomeration and phase separation. Thermal analysis demonstrated improved thermal stability for ZH5, with a higher decomposition temperature and greater residual mass. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) results showed a single glass transition temperature (Tg) for ZH5 at 88.4°C, indicating good miscibility between honey and zein materials. These findings identify 25 wt.% honey as the optimal concentration for plasticization, modifying zein’s structure and enhancing its amorphous nature and thermal resilience. The results highlight the potential of honey as a sustainable and multifunctional plasticizer for the development of biodegradable and eco-friendly polymer electrolyte systems.Keywords

Over the past several decades, the pursuit of environmentally friendly materials has intensified, driven by the depletion of fossil resources, rising environmental awareness and growing demand for green technologies. Among these, biodegradable polymer systems have emerged as promising alternatives to conventional petroleum-based polymers in applications ranging from packaging to biomedical devices and energy storage. Natural polymers, due to their renewability, biocompatibility and low environmental footprint, have gained considerable attention. One such biopolymer is zein, a prolamin protein derived from maize, which exhibits unique film-forming abilities, hydrophobicity and biodegradability which makes it suitable for applications such as food coatings, drug delivery and polymer electrolytes [1–3].

However, the application of zein in flexible and conductive materials is hindered by its inherent brittleness, poor flexibility and semi-crystalline structure, which restrict ion mobility in electrochemical applications. To address these limitations, researchers have explored various modification strategies, among which blending zein with plasticizers has proven effective in improving flexibility and enhancing the amorphous phase [4]. The amorphous nature of a polymer host is a critical factor for ionic conduction, as ions exhibit higher mobility in the amorphous regions. In polymer-plasticizer blends, the ratio of components significantly influences the balance between crystallinity and amorphousness. This occurs because the presence of amorphous components can interfere with the crystallization process of other polymer components. Plasticizers act by embedding themselves between polymer chains, reducing intermolecular forces and disrupting crystalline domains, thereby increasing polymer flexibility and amorphous character [5].

Conventional plasticizers such as glycerol, sorbitol and polyethylene glycol (PEG) have been widely used to improve the mechanical and thermal properties of biopolymers. However, there is growing interest in utilizing natural plasticizers to further promote sustainability, reduce toxicity and exploit multifunctional properties. In this regard, honey, a natural humectant and complex mixture of sugars, amino acids, phenolic compounds and organic acids, presents a unique opportunity. Honey possesses functional groups such as hydroxyl (-OH) and carbonyl (C=O) which are capable of forming hydrogen bonds with polymer backbones, thereby improving polymer chain mobility and acting as a potential bio-based plasticizer [6]. Previous studies have highlighted honey’s ability to interact with various polymeric systems [7,8]. Sarhan et al. [9] reported a significant reduction in crystallinity and enhanced ionic conductivity in polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)-chitosan films plasticized with 10 wt.% honey. Notably, polymer electrolytes with minimal crystallinity are typically preferred for their superior ionic conduction properties. Chin et al. [10] demonstrated that the incorporation of honey into PVA hydrogels lowered thermal stability but water resistance due to decreased crystallinity. Despite such promising results in synthetic and polysaccharide-based polymers, limited studies exist on the interaction between honey and protein-based polymers like zein.

In this work, the use of honey as a multifunctional plasticizer not only introduces biocompatibility and sustainability but also represents an underexplored approach compared to commonly plasticizers such as glycerol and PEG. The novelty of this work lies in demonstrating that honey, due to its complex composition of sugars and polyphenols, can simultaneously tailor crystallinity, morphology and thermal behavior of zein, offering new insights into the design of bio-based polymer systems with dual functionality—structural flexibility and enhanced performance for advanced applications such as batteries and supercapacitors. Therefore, this study aims to systematically investigate the influence of honey concentration on the physicochemical properties of zein-based polymer systems. By preparing a series of zein-honey blends with varying honey concentration and characterizing them using multiple techniques such as FTIR, XRD, FESEM, TGA and DSC. This in-depth analysis enables identification of the optimal honey concentration that enhances the amorphous character and thermal resilience of zein, thereby improving its applicability in green materials for electrochemical and biodegradable technologies.

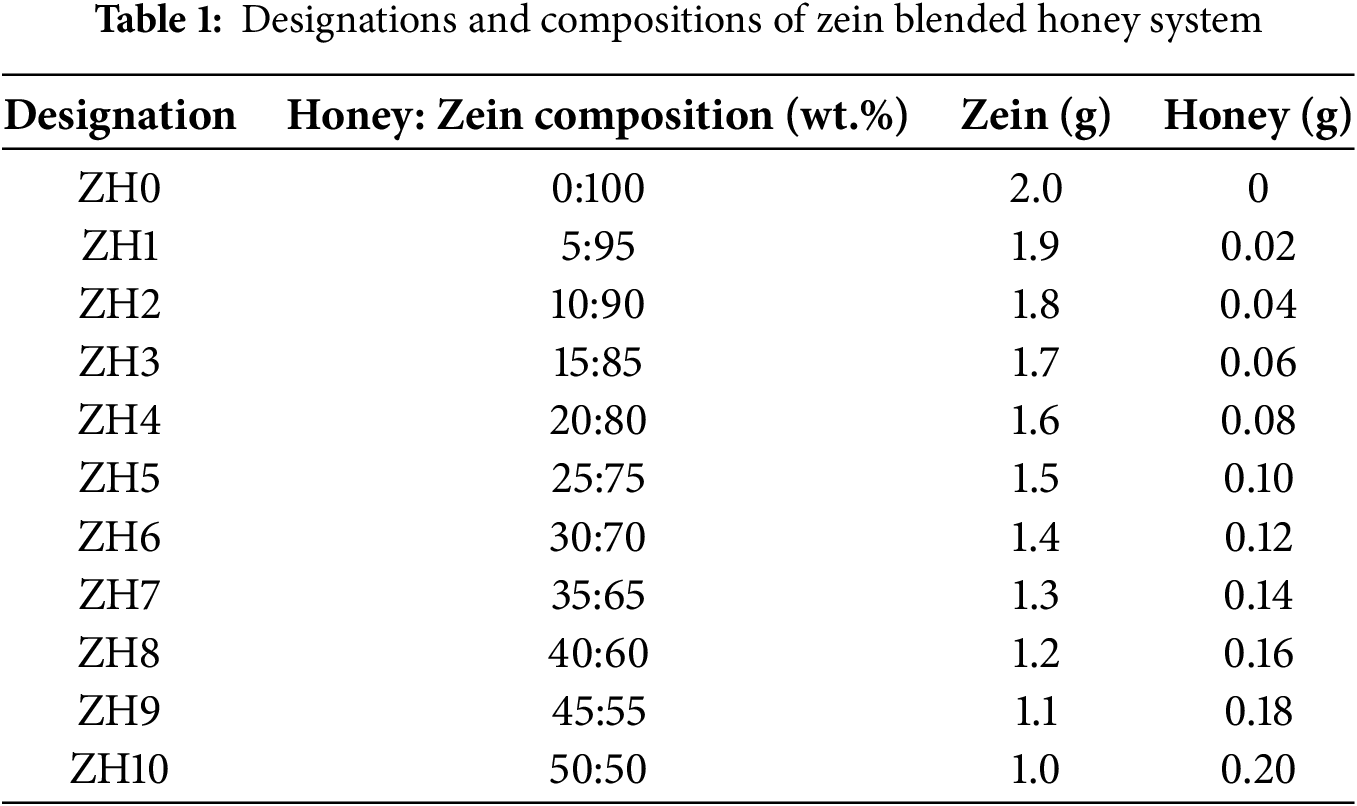

Different weight percentages (x wt.%) of honey (Hutan Hujan Tropika, Grik, Perak, Malaysia) were dissolved in 3 mL of dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Sigma-Aldrich) at room temperature for 10 min. After the honey was fully dissolved, (100 − x) wt.% of zein (Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the solution. The zein blended honey was stirred until a homogenous solution and gel-like texture were obtained. The developed gels were stored in a desiccator containing blue silica gel before further characterization. Table 1 lists the designations and compositions of zein blended honey system.

2.2 Characterization of Sample

The interactions between the materials were analysed using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) with a Spotlight 400 PerkinElmer spectrometer. Spectral measurements were recorded over the wavenumber range of 600 to 4000 cm−1 at a resolution of 4 cm−1, conducted at room temperature. The crystallinity of the samples was examined using a Rigaku Smartlab X-ray diffractometer with a wavelength of 1.5406 Å, scanning across a 2θ range of 5° to 80°. The crystallite size of the samples (D) was determined using Eq. (1):

where λ is the wavelength of the XRD patterns, β is the full width at half maximum (in radians) of the peaks and θ is the diffraction angle. The surface morphology of samples was carried out using field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM) with a Hitachi SU8220 microscope, operated at the magnification of 5 K× magnification. The thermal analysis was evaluated using thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a Perkin Elmer STA 400 analyzer. The analysis involved heating the samples from 30 to 600°C at a rate of 10°C min−1. In this work, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements were carried out using a TA Instruments Q20 calorimeter to further investigate the thermal properties of the samples. The DSC measurements were conducted under a nitrogen atmosphere (50 mL min−1), ranging from −60 to 200°C at a heating rate of 10°C min−1.

3.1 Interaction between Honey and Zein

The interaction between powder zein, zein-DMSO, honey and different ratios of zein-honey are analyzed using data obtained from the FTIR characterization. Mohamed et al. [11] reported that blending polymers with plasticizer will provide more interaction sites for ions to migrate, hence enhance the ionic conductivity. Fig. 1a shows the FTIR spectra of powder zein, DMSO and zein-DMSO (ZH0). A broad absorption peak of powder zein at 3272 cm−1 and that of DMSO appears at 3428 cm−1 are attributed to the typical of O-H stretching of carboxyl and hydroxyl groups. Meanwhile, in the ZH0 sample, the peak shifts to 3290 cm−1, indicating the occurrence of an interaction between the polymer and the DMSO solvent. This finding similar reported by Tallawi et al. [12], that in the spectrum of zein-DMSO, the stretching of the O–H and N–H bonds of the amino acids is visible at 3289 cm−1. The wide and strong absorption in the OH band region of ZH0 indicates the presence of several hydroxyl groups in zein [13].

Figure 1: FTIR spectra of (a) Powder zein, DMSO, ZH0, (b) Honey, ZH0–ZH4 and (c) ZH5–ZH10 samples in the range of 3000–3600 cm−1

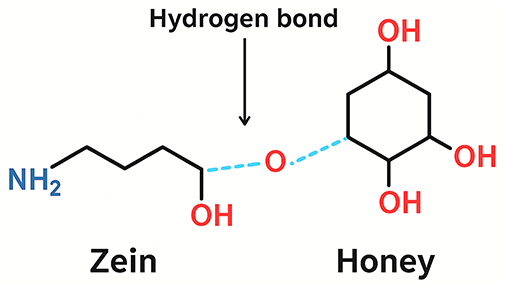

Then, Fig. 1b,c shows the spectra of honey and zein blended honey samples in the range of 3000–3600 cm−1. Bahari et al. state that [14] the interaction of honey and silver/zinc oxide nanoparticles mainly occur at hydroxyl (OH) group. The OH band of honey is located at 3270 cm−1. Hydroxyl band also shifted towards higher wave numbers (3334 cm−1) in addition of 5 wt.% honey into zein (ZH1). The hydrogen atom from the hydroxyl groups of honey interacts with the oxygen atoms of zein to form intermolecular hydrogen bonds in the plasticizer–polymer blend. These new interactions compete with the native hydrogen bonding within zein, thereby disrupting the helix packing and reducing the degree of structural order. As a consequence, the addition of honey up to 25 wt.% enhances the amorphous nature of zein by loosening the compact polypeptide arrangements and increasing chain mobility. This plasticization effect has been widely observed in biopolymer systems, where small molecules such as sugars weaken the intermolecular forces and introduce free volume within the polymer matrix, that will be discussed in “XRD analysis”. Moreover, the displacement of FTIR peaks associated with functional group oxygen atoms, such as hydroxyl and ether groups, indicates interaction of the polymer with plasticizer. This phenomenon is due to the variation of spectral peak properties, can result in physical mixing and chemical interactions. For instance, Asnawi et al. [15] reported that, the presence of hydrogen bonding in the maltodextrin (MX)-methylcellulose (MC) blend with a plasticizer is evidenced by the shift in the hydroxyl band of the polymer upon the addition of the plasticizer. With the increasing concentration of honey up to 25 wt.%, the hydroxyl band shifts to increase wavenumber as observed in Fig. 1c.

Fig. 2 illustrates the carboxyl groups of powder zein, DMSO and ZH0 that can be observed at 2997 cm−1 in powder zein, 2994 cm−1 in DMSO, and 2999 cm−1 in the ZH0 corresponds to the overlap between C=O and OH stretching vibrations of methyl (-CH3) and methylene (-CH2) groups. In powder zein, the 2997 cm−1 peak originates from the aliphatic side chains of amino acids such as leucine and valine [16,17]. Similarly, DMSO exhibits a peak at 2998 cm−1, likely due to the asymmetric stretching of its methyl (-CH3) groups. When zein is mixed with DMSO, the peak shifts slightly to 2999 cm−1, proving an interaction between zein and DMSO molecules. Furthermore, the C-H stretching appears at 2914 cm−1 of powder zein, showing the characteristic vibrational bands for protein. When zein is dissolved with DMSO, the C-H stretching peak shifts to 2915 cm−1. Ali et al. [18] reported that the CH stretching of zein located at 2925 cm−1, indicating inter and intramolecular interaction of the polysaccharide’s chains. Bahraminejad et al. [19] also recorded that the CH stretching of zein located at 2923 cm−1, which is consistent with this work. The CH stretching vibration also can be observed between 2989–3000 cm−1 when zein blended with honey. This peak corresponds to the stretching of CH bonds, which are characteristics of protein from zein [20]. The absence of obvious shifts in this region due to the molecular interactions between zein and honey do not substantially alter the CH stretching. This stability is due to the dominant zein concentrations, which maintain its structural integrity despite the presence of honey [19].

Figure 2: FTIR spectra of (a) powder zein, DMSO, ZH0, (b) honey, ZH0–ZH4 and (c) ZH5–ZH10 samples in the range of 2850–3050 cm−1

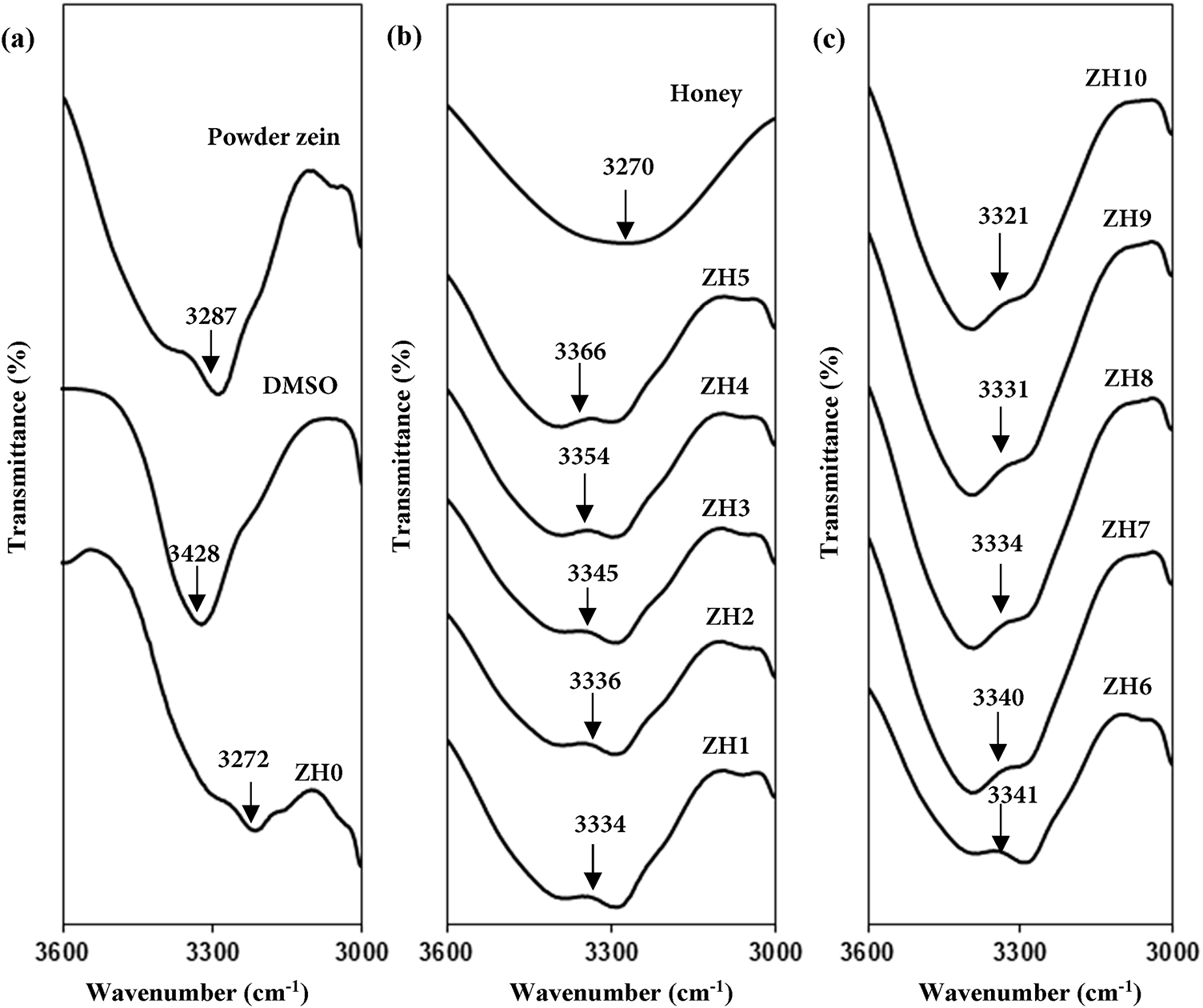

3.2 Crystallinity of Honey and Zein

The ionic conduction is more preferable in the amorphous regions of the polymer electrolyte, as the disordered structure facilitates ion mobility. Thus, determining the suitable ratio of polymer-plasticizer components is crucial for enhancing ionic conductivity, which can be identified through XRD analysis. Fig. 3 illustrates the XRD pattern for zein blended honey system, providing insights into its structural characteristics. The ZH0 spectra exhibit two obvious peaks at 2θ = 8.67° and 23.06°, corresponding to crystalline region of zein, which are consistent with findings reported in previous studies [4,21]. Li et al. [22] have emphasized that the 8.67° diffraction angle reflects the average separation between backbones of the α-helices while the 23.06° angle shows the lateral packing of the α-helices which in turn represents the crystalline nature, or the average separation between adjacent helices in the protein. From the patterns of the zein sample it is apparent that zein is a semi-crystalline polymer, as the two phases morphologies of crystalline phase and amorphous state can be confirmed two crystalline peaks are found to overlay a broad band of amorphous background [23]. The XRD pattern of ZH0 was used as a reference to identify changes in peak position and intensity in the diffractogram of zein blended honey systems.

Figure 3: XRD pattern of zein blended honey systems

The high miscibility and the good contact between zein and honey were further supported by the crystalline peaks in a ZH5 gel diffraction pattern that appeared at 2θ = 8.44° and to be shifted to 2θ = 21.21° resulting in lower intensity. Furthermore, no new reflections were detected in the XRD patterns of the blended gel of ZH5, showing that there is less crystallinity compared to ZH0 [24]. The hydroxyl groups of zein and fructose or glucose groups of honey could have a hydrogen bond interaction. In this work, honey acts as a plasticizer for zein by introducing small hydrophilic molecules, such as glucose and fructose, that disrupt the hydrogen bonding and molecular packing of zein’s chains, thereby reducing its crystallinity [9]. The hydrophilic components of honey interact with the polar groups in zein, weakening intermolecular forces and hindering the formation of ordered, crystalline regions. This disruption enhances the amorphous nature of the zein-honey composite, which contributes to increased flexibility and lower stiffness in the material [25]. The addition of honey into zein is proven to reduce the crystallinity of the gel, thus highlighting honey’s role as a plasticizer and then provides more space for ionic conduction. When the honey concentration exceeds 25 wt.%, the peak intensity increases, showing a transition towards higher crystallinity regions. This shows that the addition excess amount of honey influences the molecular arrangement of the zein matrix, promoting the formation of more ordered structures. Since broad peaks are characteristics of amorphous phases, additional analysis is required to quantitatively assess the crystallite size (D). Table 2 lists the crystallite size of the samples. The addition of honey up to 25 wt.% decreases the crystallite size from 6.008 nm (ZH0) to 4.232 nm (ZH5). These results show that ZH5 is the most amorphous sample and verify the polymer-plasticizer interaction has disrupted the crystalline region resulting in a decrease in the degree of crystallinity. On addition of 30 wt.% honey, the crystallite size increase implying that phenomenon of ion recombination dominated as too much plasticizer was provided thus affecting the number density of the ions.

One way to observe the miscibility between the constituents when combining two materials is FESEM analysis. The homogeneous smooth surface of the blended zein and honey indicates that they are miscible with each another. A micrograph of the surface of the selected zein blended honey systems is shown in Fig. 4. The entire structure of zein-DMSO (ZH0) consists of interconnected pores. Ramos Rivera et al. [1], reported that the water hydrolysis leads to the creation of pores, and during the process, zein molecules can entrap the bubbles which travel from the bottom to the surface of the electrolyte, but when the solvent has evaporated a state of resulting in the formation of a porous structure. Then, the surface micrograph of honey (Fig. 4b), revealing distinct crystal and pollen grains morphologies. Calderon-Hermosillo et al. [26] reveal that the morphological of honey varies depending on its type and crystallization time. Similarly, Mohamed et al. [27] observed the variations in the morphology of pollens grains present in G. thoracica and H. itama honey. The size, shape and aperture of pollen grains differed, reflecting the unique plant species preferences of each stingless bee during foraging. When zein is blended with honey, the surface image of ZH5 transforms into a porous and fiber-like (spherical) morphology as illustrated in Fig. 4c. This alteration results from honey’s hydrophilic properties, which allow zein to take in moisture from the surroundings and cause the zein matrix to swell. This phenomenon is consistent with the findings by Rasouli et al. [28], who reported that blending Fe3O4 nanoparticles (Fe3O4-NPs) with honey similarly produced a spherical structure. Fig. 4d presents the surface micrograph of ZH10, showing morphological changes when the honey concentration exceeds 25 wt.%. At this concentration, the structure transitions into agglomerates, indicating significant reorganization of the material. The agglomeration in ZH10 indicates that the excess concentration of honey disrupts the homogeneous zein, leading to phase separation or clustering. This trend is consistent with the observations discussed in “XRD analysis”, where the influence of increased honey concentration on the zein’s material properties was explored. The increase in honey concentration introduces a higher proportion of sugars and other hydrophilic components, which promote the formation of larger crystalline regions. This increase in crystallinity with higher concentration of honey is undesirable for applications requiring efficient ion transport in the electrolytes.

Figure 4: Morphological images of (a) ZH0, (b) Honey, (c) ZH5 and (d) ZH10 for theselected zein blended honey systems

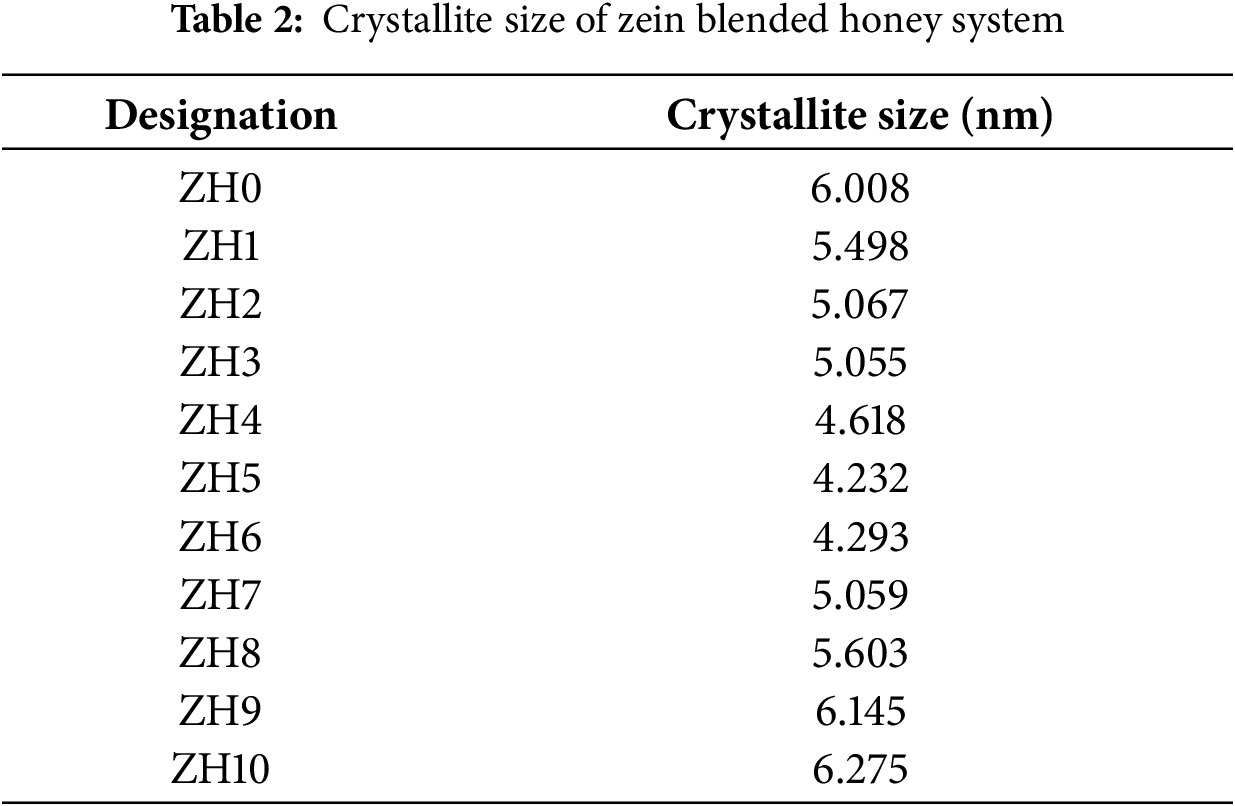

3.4 Thermogravimetric Analysis (TGA)

In blending two mixtures, thermal stability is one of the important parameters that need to be explored. The thermal stability can be investigated using TGA measurement. The TGA curves of ZH0, honey, ZH5 and ZH10 are displayed in Fig. 5. It can be observed that the first degradation in each sample occurs up to ~100°C. This first stage of degradation (1st degradation) occurs due to the loss of water weight as the polymers naturally possess hydroscopic behavior [29,30]. Major decomposition of honey occurs at ~140–300°C with a weight loss of ~60%. The second weight loss of ~70% for ZH0 occurs between ~200–350°C. Kaur & Santhiya [31] analyzed that zein has a single-step reduction of weight mechanism and breakdown temperature of ~187°C, which is consistent with present finding. The weight loss at this stage relates to the progressive depolymerization and decarboxylation of thermally unstable protein units [2]. After blending zein with 25 wt.% honey, the decomposition temperature of ZH5 was shifted to a higher decomposition temperature (>132°C), indicating an improvement in the heat resistance of zein blended honey system, which can be attributed to the intermolecular interactions between zein and honey. The increase of decomposition temperature by adding honey reveals the miscibility of zein to a certain extent, as evidenced by the changes observed in the second degradation stage of ZH5 in Fig. 5 [32]. However, beyond 25 wt.% honey (ZH10), the decomposition temperature slightly decreases to ~120°C, due to excessive amount of honey that reduces the heat resistivity. Similar findings were reported by Sarhan et al. [9], where the addition of 30 wt.% honey in PVA-chitosan polymer, the decomposition temperature is lower compared to 10 and 20 wt.% of honey. This phenomenon can mainly be attributed to the thermal decomposition of the polymer structure as well as the degradation of the honey components followed by carbonization of the honey contents. Referring to Fig. 5, it can be observed that the degradation of ZH5 is higher compared to ZH0 and ZH10, showing that ZH5 has the strongest interactions, which consistent with the “FTIR analysis” [33]. After ~400°C, there is ~6% residue left of ZH5, which is higher than ZH0 (~4%) and ZH10 (~3%), indicating ZH5 is the most thermal stability.

Figure 5: TGA curves of selected zein blended honey systems

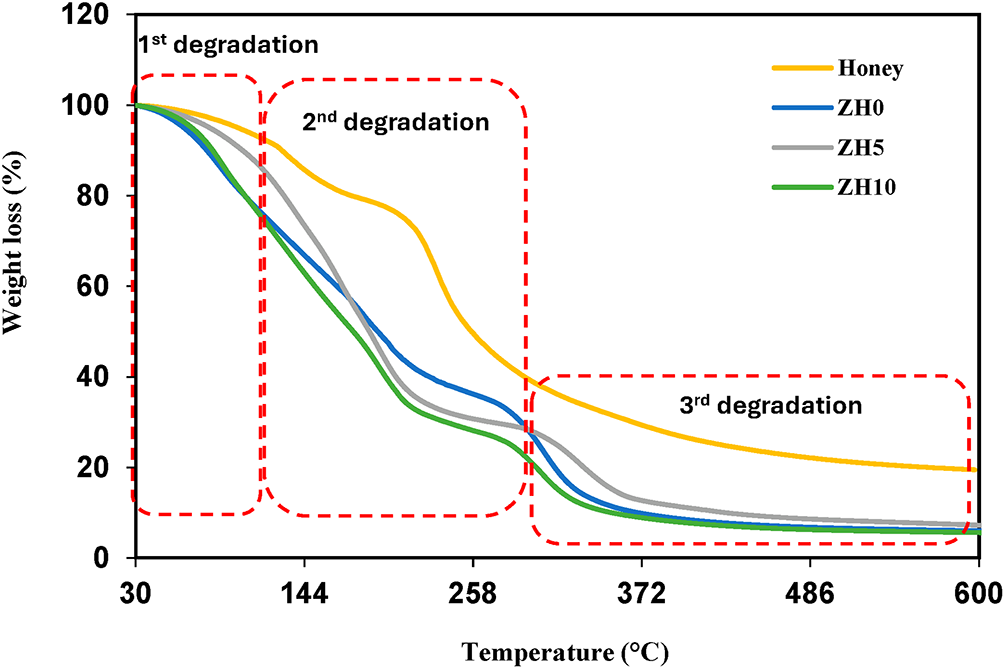

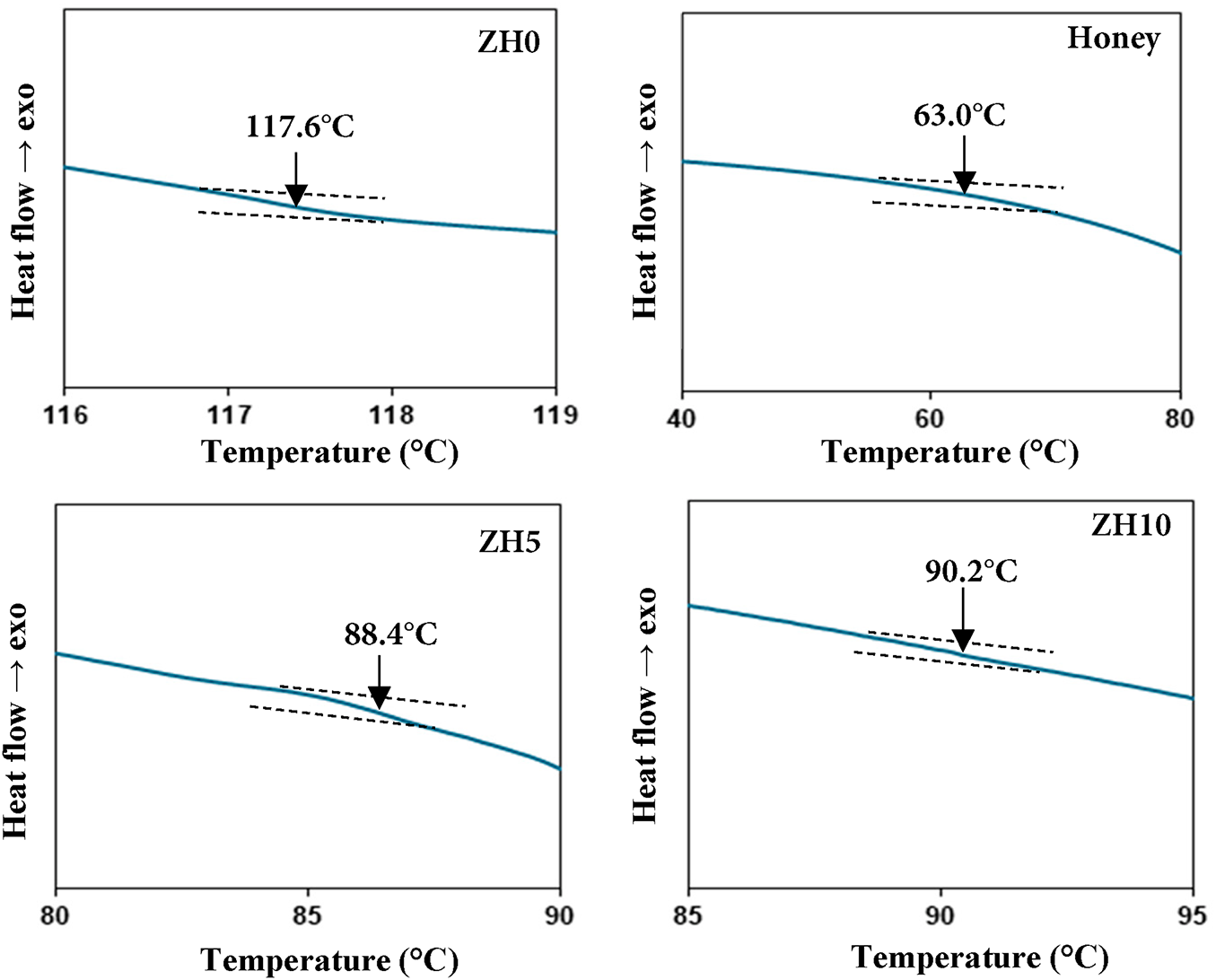

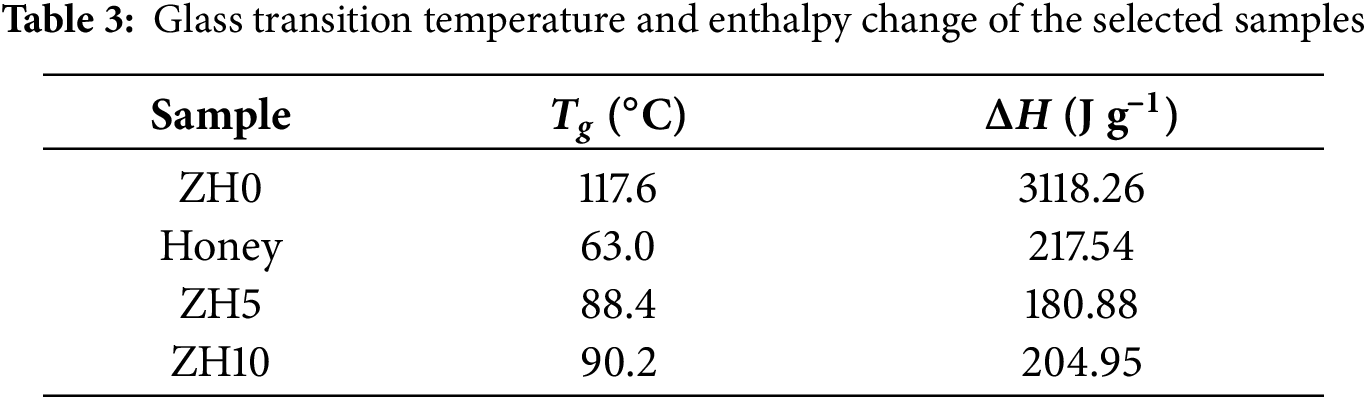

3.5 Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Thermal characterization of zein the blended honey system was further investigated using DSC analysis. The value of glass transition temperature (Tg) is extracted from the heat capacity transition midpoint. If the blended system exhibits two transitions in the DSC technique, phase separation and immiscibility of the polymer components are present [34]. Meanwhile, if the polymer materials are miscible to each other, only one transition will be observed [35]. Fig. 6 illustrates the selected DSC curves of zein blended honey system. The Tg of ZH0 is determined at 117.6°C, which is consistent with the published paper by Contardi et al. [36] of ~112.0°C for zein. In this work, the Tg of honey is found to be 63.0°C while Sobrino-Gregorio et al. [37] reported that the Tg of sunflower honey is 67.3°C, which is consistent with the Tg value in this study. When zein blended with 25 wt.% honey, the Tg is found to be 88.4°C, which lies between the Tg values of ZH0 and honey. This finding confirms the miscibility between zein and honey in ZH5. This observation indicates that the two materials are miscible and interact at the molecular level, resulting in a single, intermediate Tg. Moreover, the shift in Tg also suggests the presence of intermolecular hydrogen bonding between pure zein and honey chains, which affects the polymer chain mobility. When the concentrations of more than 25 wt.%, the Tg value increases to 90.2°C for ZH10 sample, which is attributed to the excess amount of honey enhancing the rigidity of the zein matrix. The increased honey concentration likely promotes stronger intermolecular interactions, thereby restricting polymer chain mobility and resulting in a higher Tg. The absence of endotherms peaks in this work confirms the lack of long-range crystalline domains, which is aligned with previous reports on zein [1,21,23]. This observation supports the notion that the semi-crystalline nature of zein is dominated by secondary structural arrangements compared to classical crystalline lamellae, as discussed in “XRD analysis” [22,23]. Fig. 7 shows the proposed interaction mechanism between zein and honey, emphasizing the dominant contribution of hydrogen bonding in promoting intermolecular interactions [1,21].

Figure 6: DSC thermograms of selected zein blended honey systems

Figure 7: Schematic diagram of the hydrogen bonding mechanism between zein polymer chains and honey

To validate the data, the enthalpy (ΔH) of the selected samples is calculated using Eq. (2):

where K is a constant, ΔT is the temperature difference between reference and sample and t is the testing time. In this work, as the sample possesses thermal resistance, the temperature difference arises between the reference and the sample, which is proportional to the heat flux, where the area under the heat flux curve represents enthalpy [38]. The Tg and ΔH parameters obtained from DSC analysis for the selected samples are summarized in Table 3. The ΔH decreased with the addition of honey, confirming the disruption of zein crystalline domains and enhancing amorphous region due to the honey’s plasticizing effect.

In flexibility polymer electrolytes, the polymer matrix serves as a solid solvent for ion transport without requiring organic liquids. Alternatively, the addition of plasticizers to electrolytes has constantly become an interesting approach in improving the ionic conductivity, thermal stability and electrode-electrolyte interface stability. In this work, the compatibility between zein and honey as a polymer-plasticizer host system was proven and discussed. FTIR analysis confirmed that dissolving zein and honey in DMSO led to a shift in the hydroxyl bands, proving the formation of hydrogen bonds among the OH groups of zein, honey and DMSO. Among the samples, ZH5 exhibited the lowest crystallite size (4.232 nm), proving that blending zein with honey effectively suppresses crystalline domains, making the sample highly suitable to serve as a polymer-plasticizer host. The porous surface structure observed in ZH5 provides further evidence of the miscibility and compatibility of zein and honey at this specific ratio. Furthermore, the absence of agglomerated structures based on the surface micrographs. TGA analysis of the zein blended honey systems reveals that they demonstrate characteristics from both zein and honey, as observed by a reduction in the decomposition temperature compared to the pure polymer. The ZH5 sample possesses the lowest Tg (88.4°C), proving the high amorphous region within the blend relative to other samples and supports the decision that ZH5 is the best sample to serve as the host for the blend.

Acknowledgement: The authors gratefully acknowledge Universiti Malaya for providing the equipment and facilities that supported this research.

Funding Statement: This research was supported by the Ministry of Higher Education (MoHE) of Malaysia through the Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS/1/2022/STG05/um/02/9).

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization, Nurrul Asyiqin K. Shamsuri and Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir; methodology, Nurrul Asyiqin K. Shamsuri; software, Shujahadeen B. Aziz and Siti Nadiah Halim; validation, Shujahadeen B. Aziz and Hashlina Rusdi; formal analysis, Nurrul Asyiqin K. Shamsuri; investigation, Nurrul Asyiqin K. Shamsuri and Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir; resources, Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir; data curation, Nurrul Asyiqin Shamsuri; writing—original draft preparation, Nurrul Asyiqin K. Shamsuri; writing—review and editing, Shujahadeen B. Aziz, Siti Nadiah Halim, Hashlina Rusdi and Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir; visualization, Hashlina Rusdi; supervision, Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir and Siti Nadiah Halim; project administration, Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir; funding acquisition, Mohd Fakhrul Zamani Kadir. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Ramos Rivera L, Cochis A, Biser S, Canciani E, Ferraris S, Rimondini L, et al. Antibacterial, pro-angiogenic and pro-osteointegrative zein-bioactive glass/copper based coatings for implantable stainless steel aimed at bone healing. Bioact Mater. 2021;6(5):1479–90. doi:10.1016/j.bioactmat.2020.11.001. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. El Fawal G, Omar AM, Abu-Serie MM. Nanofibers based on zein protein loaded with tungsten oxide for cancer therapy: fabrication, characterization and in vitro evaluation. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):22216. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-49190-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Yu W, Guo J, Liu Y, Xue X, Wang X, Wei L, et al. Fabrication of novel electrospun zein/polyethylene oxide film incorporating nisin for antimicrobial packaging. LWT. 2023;185(8):115176. doi:10.1016/j.lwt.2023.115176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Ahammed S, Liu F, Khin MN, Yokoyama WH, Zhong F. Improvement of the water resistance and ductility of gelatin film by zein. Food Hydrocoll. 2020;105(1):105804. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.105804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Hamsan MH, Abdul Halim N, Ngah Demon SZ, Sa’aya NSN, Kadir MFZ, Aziz SB, et al. EDLC performance of ammonium salt-green polymer electrolyte sandwiched in metal-free electrodes. Arab J Basic Appl Sci. 2023;30(1):1–9. doi:10.1080/25765299.2023.2256053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Prata JC, da Costa PM. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy use in honey characterization and authentication: a systematic review. ACS Food Sci Technol. 2024;4(8):1817–28. doi:10.1021/acsfoodscitech.4c00377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Osuna MB, Michaluk A, Romero AM, Judis MA, Bertola NC. Plasticizing effect of Apis mellifera honey on whey protein isolate films. Biopolymers. 2022;113(8):e23519. doi:10.1002/bip.23519. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

8. Lotfinia F, Norouzi MR, Ghasemi-Mobarakeh L, Naeimirad M. Anthocyanin/honey-incorporated alginate hydrogel as a bio-based pH-responsive/antibacterial/antioxidant wound dressing. J Funct Biomater. 2023;14(2):72. doi:10.3390/jfb14020072. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Sarhan WA, Azzazy HME, El-Sherbiny IM. The effect of increasing honey concentration on the properties of the honey/polyvinyl alcohol/chitosan nanofibers. Mater Sci Eng C. 2016;67(2003):276–84. doi:10.1016/j.msec.2016.05.006. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Chin SW, Azman AS, Tan JW. Incorporation of natural and synthetic polymers into honey hydrogel for wound healing: a review. Health Sci Rep. 2024;7(7):e2251. doi:10.1002/hsr2.2251. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Mohamed AS, Shukur MF, Kadir MFZ, Yusof YM. Ion conduction in chitosan-starch blend based polymer electrolyte with ammonium thiocyanate as charge provider. J Polym Res. 2020;27(6):149. doi:10.1007/s10965-020-02084-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Tallawi M, Amrein D, Gemmecker G, Aifantis KE, Drechsler K. A novel polysaccharide/zein conjugate as an alternative green plastic. Sci Rep. 2023;13(1):13161. doi:10.1038/s41598-023-40293-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Dai F, Zhuang Q, Huang G, Deng H, Zhang X. Infrared spectrum characteristics and quantification of OH groups in coal. ACS Omega. 2023;8(19):17064–76. doi:10.1021/acsomega.3c01336. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Bahari N, Hashim N, Abdan K, Md Akim A, Maringgal B, Al-Shdifat L. Role of honey as a bifunctional reducing and capping/stabilizing agent: application for silver and zinc oxide nanoparticles. Nanomaterials. 2023;13(7):1244. doi:10.3390/nano13071244. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Asnawi ASFM, Hamsan MH, Aziz SB, Kadir MFZ, Matmin J, Yusof YM. Impregnation of [Emim]Br ionic liquid as plasticizer in biopolymer electrolytes for EDLC application. Electrochim Acta. 2021;375:137923. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2021.137923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Bancila S, Ciobanu CI, Murariu M, Drochioiu G. Ultrasound-assisted zein extraction and determination in some patented maize flours. Rev Roum Chim. 2016;61(10):725–31. [Google Scholar]

17. Rojas-Lema S, Gomez-Caturla J, Balart R, Arrieta MP, Garcia-Sanoguera D. Development and characterization of thermoplastic zein biopolymers plasticized with glycerol suitable for injection molding. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;218:119035. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2024.119035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Ali GW, Ellatif MAA, Abdel-Fattah WI. Extraction of natural cellulose and zein protein from corn silk: physico-chemical and biological characterization. Biointerface Res Appl Chem. 2021;11(3):10614–9. doi:10.33263/BRIAC113.1061410619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Bahraminejad S, Mousavi M, Askari G, Gharaghani M. Effect of octenylsuccination of alginate on structure, mechanical and barrier properties of alginate-zein composite film. Int J Biol Macromol. 2023;226(6):463–72. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.12.019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Ricardo Fiori Z, Paulo Rodrigo Stival B, Tatiana Shioji T, Vanderson G, Fábio Pinheiro DS, Érica Rosane Kovalczuk Á. Application of zein and chitosan in the development of a colon-specific delivery system. J Appl Pharm Sci. 2020;11(7):89–97. doi:10.7324/japs.2021.110709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Li S, Huang L, Zhang B, Chen C, Fu X, Huang Q. Fabrication and characterization of starch/zein nanocomposites with pH-responsive emulsion behavior. Food Hydrocoll. 2021;112(2):106341. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2020.106341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Li Y, Bai Y, Huang J, Yuan C, Ding T, Liu D, et al. Airglow discharge plasma treatment affects the surface structure and physical properties of zein films. J Food Eng. 2020;273(2):109813. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2019.109813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Rasteh I, Pirnia M, Miri MA, Sarani S. Encapsulation of Zataria multiflora essential oil in electrosprayed zein microcapsules: characterization and antimicrobial properties. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;208(1750–3841):117794. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Madian NG, El-Ashmanty BA, Abdel-Rahim HK. Improvement of chitosan films properties by blending with cellulose, honey and curcumin. Polymers. 2023;15(12):2587. doi:10.3390/polym15122587. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Radoor S, Karayil J, Jayakumar A, Siengchin S, Parameswaranpillai J. A low cost and eco-friendly membrane from polyvinyl alcohol, chitosan and honey: synthesis, characterization and antibacterial property. J Polym Res. 2021;28(3):82. doi:10.1007/s10965-021-02415-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Calderon-Hermosillo CY, de la Torre Ibarra MH, Frausto-Reyes C, Flores-Moreno JM, Casillas-Peñuelas R. Mexican bee honey identification using sugar crystals’ image histograms. Appl Sci. 2024;14(23):11186. doi:10.3390/app142311186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Mohamed AS, Zaidi NFM, Hamimi A, Eshak Z. Morphological characterization of pollen in kelulut (stingless bee) honey. Malays J Microsc. 2016;12:71–7. [Google Scholar]

28. Rasouli E, Basirun WJ, Rezayi M, Shameli K, Nourmohammadi E, Khandanlou R, et al. Ultrasmall superparamagnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles: honey-based green and facile synthesis and in vitro viability assay. Int J Nanomedicine. 2018;13:6903–11. doi:10.2147/IJN.S158083. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Slesarenko NA, Chernyak AV, Khatmullina KG, Baymuratova GR, Yudina AV, Tulibaeva GZ, et al. Nanocomposite polymer gel electrolyte based on TiO2 nanoparticles for lithium batteries. Membranes. 2023;13(9):776. doi:10.3390/membranes13090776. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Tran TTV, Nguyen NN, Nguyen QD, Nguyen TP, Lien TN. Gelatin/carboxymethyl cellulose edible films: modification of physical properties by different hydrocolloids and application in beef preservation in combination with shallot waste powder. RSC Adv. 2023;13(15):10005–14. doi:10.1039/d3ra00430a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Kaur M, Santhiya D. UV-shielding antimicrobial zein films blended with essential oils for active food packaging. J Appl Polym Sci. 2021;138(7):49832. doi:10.1002/app.49832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Zhang Q, Yang X, Guo Z, Fang Y, Li K, Sheng K. Zein composite film with excellent toughness: effects of pyrolysis biochar and hydrochar microspheres. J Clean Prod. 2022;367(3):133039. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.133039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhang L, Li K, Yu D, Regenstein JM, Dong J, Chen W, et al. Chitosan/zein bilayer films with one-way water barrier characteristic: physical, structural and thermal properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2022;200:378–87. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.12.199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Resch J, Dreier J, Bonten C, Kreutzbruck M. Miscibility and phase separation in PMMA/SAN blends investigated by nanoscale AFM-IR. Polymers. 2021;13(21):3809. doi:10.3390/polym13213809. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Patel G, Minko T. Miscibility, phase behavior, and mechanical properties of copovidone/HPMC ASLF and copovidone/Eudragit EPO polymer blends for hot-melt extrusion and 3D printing applications. Int J Pharm. 2025;670:125124. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.125124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Contardi M, Fadda M, Isa V, Louis YD, Madaschi A, Vencato S, et al. Biodegradable zein-based biocomposite films for underwater delivery of curcumin reduce thermal stress effects in corals. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(28):33916–31. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c01166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Sobrino-Gregorio L, Vargas M, Chiralt A, Escriche I. Thermal properties of honey as affected by the addition of sugar syrup. J Food Eng. 2017;213(9):69–75. doi:10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2017.02.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. Sun X, Lee KO, Medina MA, Chu Y, Li C. Melting temperature and enthalpy variations of phase change materials (PCMsa differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) analysis. Phase Transit. 2018;91(6):667–80. doi:10.1080/01411594.2018.1469019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools