Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

MXene-Based Moisture-Responsive Actuators: Preparation and Applications

1 School of Materials Science and Engineering, Tianjin University, Tianjin, 300350, China

2 Shanxi Key Laboratory of Artificial Intelligence & Micro Nano Sensors, College of Integrated Circuits, Taiyuan University of Technology, Taiyuan, 030024, China

* Corresponding Authors: Jia-Nan Ma. Email: ; Ling Wang. Email:

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 909-927. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.071607

Received 08 August 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

MXene (Ti3C2Tx) is known for its excellent hydrophilicity, electrical conductivity, and dispersibility. It is a promising candidate for the fabrication of moisture-responsive actuators due to the strong interaction between MXene sheets and water molecules. Inspired by natural organisms, a variety of moisture-actuated soft robots have been successfully developed through the systematic integration of MXene-based actuators. This minireview summarizes recent advances in the preparation and applications of MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators. The hydrophilic properties of MXene, along with design principles, working mechanisms, current progress, and applications of MXene-based actuators, are discussed. The future prospects and developmental directions of MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators are put forward, providing novel insights for their further advancement in the realm of automatable smart devices.Keywords

Stimuli-responsive soft actuators are devices that can directly convert environmental stimuli (such as humidity [1,2], light [3,4], electricity [5–7], heat [8,9], and magnetism [10–12]) to reversible shape change or mechanical work. Due to the advantages of flexibility, light weight, high degree of freedom, good safety, and strong environmental adaptability [13–16], soft actuators have great application potential in robotic devices, micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS), artificial muscles, bionic systems and other fields [17–21]. Actuators that can be driven by environmental stimuli without additional energy supply systems are becoming the preferred actuating components for next-generation smart products [22–24]. The rapid progress of stimuli-responsive materials [25–28], advanced micro-nano processing technologies [29,30], novel structures [31–33], and new actuation methods [34,35] has propelled the development of actuators. Among the various stimuli-responsive actuators, moisture-responsive actuators [36–38] have received widespread attention from researchers. This is because moisture is a renewable, non-polluting, easily available green energy source, which has mild and adaptable operating conditions. Inspired by biological actuation systems such as Chirita pumila and pinecones, moisture-responsive actuators based on different humidity-driven materials have been widely designed in a biomimetic manner. The actuation mechanism of the moisture-responsive actuators is based on changes in the surrounding humidity, which cause asymmetric changes in volume resulting from the absorption/desorption of water molecules, leading to the actuating performance.

A wide range of humidity-driven materials, such as graphene oxide (GO), hydrogels, cellulose, polyionic liquids, and polymers, are currently used to prepare moisture-responsive actuators [39–44]. These materials, however, cannot simultaneously exhibit excellent moisture-responsive performance and high electrical conductivity. This limits the development of smart electronic devices that rely on humidity actuation. Ti3C2Tx MXene is a new kind of two-dimensional material. It is considered an outstanding candidate for moisture-responsive actuators due to its superior electrical conductivity (>15,000 S cm−1) [45,46] among all solution-processed materials (graphene, MoS2, etc.) and hydrophilicity similar to GO [47]. For conductivity, the core Mn+1Xn framework (with transition metals) has delocalized valence electrons that create a metallic electron gas enabling high electronic transport, and the surface terminations barely disrupt this electronic structure. The excellent hydrophilicity of MXene is contributed to their 2D layered morphology that provides a large specific surface area for water molecule adsorption, tunable interlayer gaps that facilitate water penetration, and the oxygen-containing-groups (OCGs) distributed on the MXene flakes, which can form hydrogen bonds with water molecules. MXene accordingly exhibits superior water adsorption capacity under humid conditions, thereby inducing a moisture-responsive swelling behavior. When humidity is removed, MXene shows shrinking behavior owing to water desorption. The amount and distribution of terminal functional groups on the MXene flakes can be controlled using various preparation methods [48,49]. MXene can also be prepared on a large scale from the most common Ti3AlC2 MAX [50–52], whose oxidation degree, size, thickness, and defects can be effectively tailored during the wet etching process [53–55]. Tractable solution processing of MXene further allows easy fabrication into diverse morphologies, including fibers [56,57], films [58,59], and foams [60,61]. These combined characteristics render MXene a promising moisture-responsive smart material for applications in both sensors and actuators.

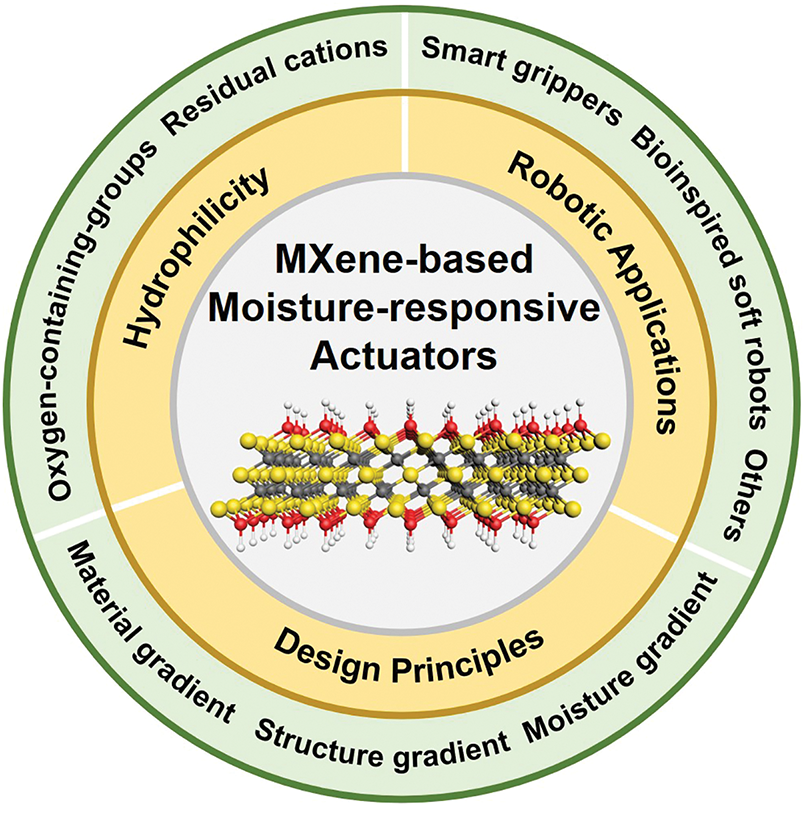

This work mainly focuses on the moisture-responsiveness of stacked Ti3C2Tx MXene sheets and recent progress in MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators and soft robotics (Fig. 1). The unique interaction between MXene and water molecules is briefly introduced. The biomimetic design principles and working mechanisms of MXene-based actuators are then presented. The recent advances in moisture-responsive MXene-based biomimetic actuators and soft robotic systems are comprehensively reviewed. The future development directions and challenges in this research field are finally laid out.

Figure 1: Overview of MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators

2 MXene-Based Moisture-Responsive Actuators and Their Applications

2.1 Interaction between MXene Sheets and Water Molecules

MXene is synthesized by selectively removing the A layer from its parent MAX phase, where M denotes an early transition metal, A signifies aluminum, silicon, zinc, or gallium, and X represents carbon or nitrogen. The most common preparation method for Ti3C2Tx MXene involves etching its corresponding MAX precursors (Ti3AlC2) using a mixture of hydrochloric acid (HCl) and lithium fluoride (LiF) or directly using hydrofluoric acid (HF) [62,63]. After the ‘A’ layer of Ti3AlC2 is etched away, Ti3AlC2 precursors can be efficiently exfoliated into single-layer Ti3C2Tx MXene via ultrasonication, yielding a stable MXene aqueous dispersion. This method can realize the high-yield preparation of Ti3C2Tx MXene while retaining its performance [64] (Fig. 2a). Through continuous research efforts, high-quality MXene aqueous solutions are now commercially available. Compared with other 2D materials, Ti3C2Tx MXene can be readily dispersed in both water and organic solvents, which is crucial for the preparation of films for actuators. As shown in Fig. 2b, the research results demonstrate that Ti3C2Tx is capable of forming long-term stable dispersions in water and several organic solvents [65], including ethanol, propylene carbonate (PC), N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP), and N, N-dimethylformamide (DMF). Soft yet robust MXene films can be fabricated via the ordered stacking of MXene nanosheets [64], as shown in Fig. 2c. This feature is beneficial for developing 2D film-based actuators.

Figure 2: Interaction between MXene and water molecules. (a) Photograph of the MXene solutions and diluted MXene dispersion. Adapted with permission from reference [64]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (b) Dispersions of Ti3C2Tx in twelve solvents. Adapted with permission from reference [65]. Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society. (c) Photograph of the MXene film. Adapted with permission from reference [64]. Copyright 2025, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (d) Scheme of humidity response. Adapted with permission from reference [66]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society. (e–h) The c parameter (2 × d002) of A-Ti3C2Tx (A is an intercalated cation). Adapted with permission from reference [66]. Copyright 2016, American Chemical Society

The hydrophilic nature of MXenes renders them highly suitable for moisture-responsive actuators, as these materials change shape in response to humidity fluctuations [66,67]. The hydrophilicity of MXene is primarily ascribed to the terminal functional groups on its surfaces, which exhibit robust interactions with water molecules via hydrogen bonding. This expands the interlayer d-spacings of MXene sheets [68], thereby inducing morphological transformation. Minor humidity fluctuations can generally induce significant volume changes [69], which greatly benefits MXene as a moisture-responsive actuator material. Apart from the terminal functional groups on the surface, residual cations after synthesis can also trigger sensitive interactions between MXene sheets and water molecules via hydrogen bonds and hydration/dehydration processes (Fig. 2d) [66]. During the adsorption process, the water molecules can readily occupy the interlayer free space of 2D MXene nanosheets, thereby enlarging their d-spacing. Owing to the relatively weak hydrogen bonding strength in the range of 4–170 kJ·mol−¹ and low hydration energy (e.g., ~520 kJ·mol−¹ for Li+) [66], MXene exhibits high sensitivity to variations in relative humidity, and the interaction is reversible. Therefore, fluctuation of humidity would induce the swelling and shrinking of MXene sheets, as clearly evidenced by X-ray diffraction (XRD) results. The measurement results for the lattice constant c parameter in Fig. 2e–h confirm atomic-scale actuation, ultimately leading to macroscopic deformation [66]. Furthermore, MXene can easily exchange interlayer adsorbed ions with various cations (Mg2+, Ca2+, Na+, K+, Rb+, etc.) to modulate their adsorption/desorption of water molecules. Variations in the size and charge of intercalation ions result in a distinct interlayer d-spacing. Each cation-embedded MXene therefore exhibits a reversible response to distinct relative humidity (RH) ranges (Fig. 2e–h), such as 0%–10% for Mg2+, 20%–50% for Ca2+, and 60%–95% for Li+ and Na+. This phenomenon is clearly associated with the standard enthalpy of hydration. The above results demonstrate that the effects of different intercalated cations should be considered when utilizing MXene in moisture-responsive actuators. In addition, when lithium ions are replaced by protons, Ti3C2Tx films exhibit ultra-high sensitivity in humidity sensors [70,71], achieving reversible responses over a wide RH range of 0.1% to 95.0%. This confirms that MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators can not only operate stably across a broad humidity range but also have finely tunable actuation performance. When Ti3C2Tx is composited with polyelectrolytes and applied in humidity sensors, it shows ultrafast response/recovery speeds of 110 and 220 ms, respectively [72,73]. This indicates that MXene can quickly reach equilibrium through fast water adsorption/desorption processes with fluctuation in humidity, suggesting that moisture-responsive MXene actuators could exhibit a remarkably rapid response.

Compared with other moisture-responsive materials, MXene possesses both high electrical conductivity (15000 S cm−1) and excellent humidity responsiveness. For GO, although the electrical conductivity of GO can be partially restored via reduction, its moisture-responsive properties are significantly reduced due to the decrease in number of OCGs [74]. The electrical conductivity of reduced GO is also far lower than that of MXene. Hydrogels, another widely used type of moisture-responsive materials, excel in flexibility and high water-swelling capacity but suffer from slow response speed, poor mechanical robustness and ultra-low intrinsic conductivity [75,76]. This makes them unsuitable for scenarios requiring both structural stability and electrical functionality (e.g., self-sensing actuators). Meanwhile, ionic polymer-based actuators depend mainly on ion migration to achieve water-driven actuation, but they exhibit notable drawbacks: small deformation ability, relatively simple response modes, mediocre environmental stability that is highly dependent on electrolyte retention [77,78]. In contrast, MXene exhibits irreplaceable advantages in the preparation of moisture-responsive actuators with high conductivity, good mechanical properties, and fast response. The excellent electrical conductivity, high thermal conductivity, and superior electromagnetic wave absorption properties of MXene [79,80] further support the construction of moisture-responsive actuators with multi-stimuli responsiveness.

2.2 Design Principles and Working Mechanisms of MXene-Based Actuators

MXene exhibits a highly sensitive dimensional response to humidity, positioning it as a promising smart material for moisture-responsive actuators. Research on MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators is currently in its early stages. According to the distinct design principles and working mechanisms, MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators can be categorized into three types. The first type has a material gradient, which features a bilayer structure where each layer exhibits distinct moisture-responsive behaviors. The second type has a structure gradient. The third type has homogeneous composition and structure, which is actuated by moisture gradient.

2.2.1 MXene Actuator with Material Gradient

In nature, many plants (such as pinecones [81], Venus flytraps [82]) exhibit movements triggered by moisture in the air. This is because among the multiple layers of tissues in these plants, some layers are humidity-sensitive while others are not. Inspired by this interesting natural phenomenon, scientists have prepared various moisture-responsive actuators through adjusting the material gradient. The general principle for obtaining actuators with material gradients is combining a moisture-responsive material with a moisture-inert material. When exposed to moisture, the volume change of the sensitive layer is larger than that of the inert layer. Strain mismatch at the interface of a double-layer or multi-layer structure composed of two or more materials of different water adsorption/desorption capacities induces bending deformation. For instance, Cai et al. [83] reported a MXene-cellulose composite/polycarbonate (MXCC/PC) bilayer moisture-responsive actuator. The hydrophilic OCGs (-O and -OH) at the end of MXene sheets and cellulose nanofibers collectively impart MXCC with hygroscopicity. When the RH is about 70%, the MXCC/PC actuator can maintain its flat state. When exposed to low humidity conditions (10% RH), the MXCC layer shrinks due to water desorption, while the PC layer exhibits negligible response to humidity fluctuations. The bilayer actuator thus undergoes deformation toward the MXCC side owing to the strain mismatch at the interface. With the increase in humidity, the actuator automatically returns to a flat state. We previously reported a moisture-responsive actuator composed of MXene layer and tape layer (Fig. 3a, left) [84], which effectively converts humidity energy into mechanical energy. The moisture actuation mechanism of this actuator involves the asymmetric water adsorption and desorption behaviors between the MXene layer and the tape layer (Fig. 3a, middle) [84], which induces bending deformation. Experiments showed that the bending angle increases with rise in relative humidity, as displayed in Fig. 3a, right [84]. Guided by the above design principle, several moisture-responsive bimorph actuators composed of MXene and different inert materials (e.g., MXene/GO&Fe3O4 [85], MXene/polyethylene [41], MXene/VO2@PMMA [86], and MXene/CNF-MPE [87]) have been fabricated via various methodologies, such as vacuum filtration, spin coating and blade coating.

Figure 3: Design principles, typical structures, working mechanisms and experimental results of MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators based on a. material gradient, b. structure gradient, and c. moisture gradient. (a) Adapted with permission from reference [84]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (b) Adapted with permission from reference [90]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (c) Adapted with permission from reference [91]. Copyright 2020, Wiley-VCH GmbH

Although these actuators based on different materials have advantages such as large deformation and simple preparation, the interface interactions between MXene and other smart materials generally involve relatively weak van der Waals forces. Such moisture-responsive actuators may suffer from severe interlayer delamination, particularly during frequent bending-straightening processes. To address this issue, Cao and co-workers prepared a hierarchical gradient structured MXene/CNF/PDA (G-MXCP) actuator via layer-by-layer assembly method, inspired by the delicate architecture of natural bamboo [88]. Notably, it integrates both material composition gradients (e.g., varying MXene/CNF/PDA mass ratios across the film thickness) and microstructure gradients. This G-MXCP film exhibits two different sides: the top layer has a relatively low CNF content, while the bottom layer possesses high CNF content. As the humidity increases, the bottom layer absorbs more water molecules, expanding the d-spacings of MXene sheets and leading to asymmetric volume expansion between its two sides. Consequently, the G-MXCP film can achieve bending/unbending deformations during humidity fluctuations. Due to the absence of distinct interfaces between the materials, severe delamination during frequent actuation is effectively mitigated, thereby enhancing the long-term mechanical stability of the actuator.

2.2.2 MXene Actuator with Structure Gradient

Moisture-responsive MXene actuators can also be constructed by creating a structure gradient within the same material composition. These actuators generally feature pore structures having a gradient distribution along their cross-sections or possess distinct microstructures on their two sides. Zhang and co-workers [69] constructed a structure gradient on an MXene film via soft lithography and introduced anisotropic quantum-confined superfluidics (QSF) channels, thereby enabling the fabrication of the moisture-responsive MXene film. The QSF effect refers to the ultrafast ion/molecule transport in biological channels in a single-molecule or ionic-chain manner [89]. Since the interlayer spacing of MXene typically ranges from 11 to 16 Å, depending on the water content, MXene films can be regarded as a natural QSF system. The adsorption and transportation of water molecules within the QSF channel between layered MXene nanosheets would result in significant interlayer expansion. This assumption was confirmed by experimental results of the d-spacing of MXene paper in different RHs, which showed that the d-spacing is 11.98 nm at 44% RH and 12.21 nm at 97% RH. Based on the above results, the structured MXene film containing many hydrophilic OCGs possesses gradient QSF channels due to its asymmetric micro-nanostructures. Under moisture actuation, the different QSF channels enable asymmetric water absorption and film swelling, demonstrating bending deformation towards the flat side. Compared with MXene-based bimorph actuators, these MXene actuators exhibit improved durability owing to the absence of material interfaces.

Our group recently fabricated a moisture-responsive MXene actuator possessing asymmetric QSF channels through unilateral evaporation assembly [90]. Constrained by the smooth substrate, the bottom surface of the formed MXene film is extremely flat, while the top surface is relatively rough due to water evaporation, thus forming asymmetric QSF channels (Fig. 3b, left). The moisture-responsive mechanism of the MXene actuator is based on inhomogeneous water adsorption/desorption within the asymmetric QSF channels (Fig. 3b, middle). According to in situ confocal laser scanning characterization, when the humidity changes from 23% RH to 100% RH, the roughness values of rough and smooth surfaces are 0.497 and 0.198 μm, respectively (Fig. 3b, bottom). These results confirm that humidity variations induce a more significant change in the rough surface than the smooth surface of the MXene film. This phenomenon corresponds to the asymmetric swelling effect caused by the asymmetric QSF channels. Consequently, the MXene film bends toward its smoother side under humid conditions. Experimental results further demonstrate that the MXene film has favorable responsiveness under different RH conditions (Fig. 3b, right). MXene films can be temporarily formed into arbitrary shapes via moisture-assisted mechanical compression. This capability enhances their moisture-responsive deformability and also enables more complex deformation modes, such as bending, helical bending, and S-shape. This work presents a straightforward method for fabricating monolayer actuators.

2.2.3 MXene Actuator with Moisture Gradient

Moisture-responsive MXene actuators can also be achieved by controlling the environmental moisture gradient. This type of actuator is generally based on a homogeneous material system. Under an uneven humidity field, the actuator develops a thin hydration expansion layer on the high-humidity side, while the opposite side remains in a low-humidity state, creating a distinct bilayer structure. The expansion gradient induces compressive stress in the low-humidity side, thereby triggering bending deformation. Wang and co-workers [91] prepared a homogeneous Ti3C2Tx MXene film, which demonstrated highly controllable actuation featuring fast response and large deformation via a moisture gradient (Fig. 3c, left). Due to the asymmetric moisture field, the high-humidity side absorbs more water than the opposite side, causing large deformation of the film (Fig. 3c, middle and right). Based on the above principles, researchers have developed more MXene-based actuators with excellent performance by combining MXene with other functional materials (such as cellulose nanofiber [92], bacterial cellulose [93], sodium alginate [94], etc.). These actuators exhibit large deformation, excellent durability, high mechanical strength, and remarkable shape programmability. While moisture actuation can be feasibly achieved through environmental moisture gradient, precise control of such gradients remains highly challenging. For example, while microfluidic chips can generate linear humidity gradients (ΔRH = 10%–90%) through gas mixing channels, their narrow microchannels (typically 50–200 μm) limit their application in large-area MXene actuators (e.g., >1 cm2). Local humidity field methods, such as the saturated salt solutions method, demand strict ambient temperature control; even small temperature fluctuations can cause humidity gradient deviation [95]. Additionally, their slow dynamic response fails to satisfy the real-time actuation requirements of MXene-based soft robots. In most practical contexts, the moisture gradient primarily serves as a complementary strategy for moisture actuation. Various moisture actuation strategies and performances of MXene-based actuators reported in recent years are listed in Table 1. It can be seen that the actuators based on material gradient can achieve larger bending angles, while actuators based on moisture gradient have shorter response/recovery times. Combining these strategies may enable the development of MXene-based actuators with superior performance.

2.3 Applications of MXene-Based Actuators

Compared with traditional rigid robots, soft robots have shown great application potential due to their strong environmental adaptability, high safety, and flexible movements. The development of soft robots is dependent on the progress of actuators, sensors, computing, and control systems. Moisture-responsive actuators are a promising candidate due to their environmental friendliness, and many examples have been demonstrated until now, including smart grippers, walking robots, soft fingers, smart switches, etc. Moisture-responsive actuators with self-sensing ability further enable real-time monitoring of various deformations, which is also beneficial for soft robotics applications.

Natural organisms have evolved a wide array of sophisticated grasping mechanisms for critical functions such as hunting, foraging, and self-defense. To mimic these biological behaviors, MXene-based moisture-responsive soft grippers have been extensively developed. Inspired by the Venus flytrap, a smart gripper capable of capturing and releasing plastic foam under moisture stimuli was fabricated using MXene/cellulose nanofiber/LiCl (MCL) actuators (Fig. 4a) [106]. The gripping capability can be primarily attributed to the bending deformation of the MCL actuators induced by the moisture gradient. When exposed to moisture from a plastic straw, the gripper securely grasps a foam weighing approximately 9 times its mass within 1 s. When the moisture gradient is removed, the gripper rapidly releases the foam. This mechanism enables controlled grasping and releasing functions. To further improve gripper performance, Ma et al. fabricated a simple, smart gripper using GO&Fe3O4/MXene bilayer actuators, responsive to both moisture and electricity (Fig. 4b) [85]. The multi-responsiveness of the actuator can be attributed to the asymmetric water adsorption, transportation, and desorption behaviors between the GO&Fe3O4 layer and the MXene layer. The smart gripper, with its claws in a bent configuration, was initially placed under ambient conditions with approximately 25% RH. Under subsequent moisture and electrical stimuli, the smart gripper can realize the capture and release of a smooth straw (88 mg), with a payload capacity of 18 times its own weight. These studies highlight the systematic design and development of smart grippers based on MXene actuators.

Figure 4: Applications of MXene-based actuators. (a) Soft gripper based on MXene/cellulose nanofiber/LiCl. Adapted with permission from reference [106]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (b) Smart gripper based on MXene/GO&Fe3O4. Adapted with permission from reference [85]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (c) Biomimetic flower robot. Adapted with permission from reference [94]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (d) Origami crane robot. Adapted with permission from reference [88]. Copyright 2020, American Chemical Society. (e) Hand-shaped actuator. Adapted with permission from reference [107]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (f) Biomimetic walker. Adapted with permission from reference [94]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (g) Bionic crab-like crawling robot. Adapted with permission from reference [85]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (h) Photographs of the motor. Adapted with permission from reference [104]. Copyright 2021, Wiley-VCH GmbH. (i) “Flytrap” and three-leg crawling robot. Adapted with permission from reference [108]. Copyright 2024, American Chemical Society. (j) A smart insect trap. Adapted with permission from reference [109]. Copyright 2022, Science China Press. Published by Elsevier B.V. and Science China Press. (k) A moisture-controlled smart switch. Adapted with permission from reference [107]. Copyright 2021, American Chemical Society. (l) A smart shielding curtain. Adapted with permission from reference [90]. Copyright 2024, Wiley-VCH GmbH

The moisture-responsive bending behavior of MXene actuators also makes them as ideal candidates for the design of bioinspired soft robots. Inspired by the adaptive opening and closing dynamics of flower petals in response to environmental stimuli, Sun and colleagues successfully developed a moisture-controlled actuator to mimic floral behavior (Fig. 4c) [94]. This actuator can make the “petals” close under high humidity conditions and open when the humidity decreases. Cao et al. developed an origami crane robot using G-MXCP actuator (Fig. 4d) [88], capable of reversible wing flapping movements under moisture actuation. Li et al. fabricated a moisture-responsive hand-shape actuator based on MXene/cellulose/polystyrene sulfonic acid membrane (MCPM), which emulates the flexible bending motions of human fingers (Fig. 4e) [107].

To broaden the practical applications of MXene-based actuators, researchers have developed a series of motion robots, such as walking, crawling, and rolling robots. Sun and co-workers successfully demonstrated a biomimetic walker composed of bendable components with different lengths (Fig. 4f) [94]. This biomimetic walker can realize continuous directional locomotion under periodic humidity stimuli. Ma et al. reported a bionic crab-like crawling robot using multi-responsive GO&Fe3O4/MXene film (Fig. 4g) [85]. The robot can achieve step-by-step lateral movement similar to natural crabs under coupling manipulation of light and moisture. Yang and co-workers prepared a moisture-driven motor that can roll on a plane (Fig. 4h) [104]. Moisture-induced bending deformation and change in the center of gravity were responsible for the rolling behavior. Various biomimetic motion robots with unique configurations have been further developed, enabling forward or right-turning locomotion (Fig. 4i) [108]. A flytrap-inspired smart insect-trapping robot was developed by integrating pressure-sensing and moisture-actuating systems (Fig. 4j) [109], enabling it to perceive and capture worms.

Ultra-high electrical conductivity and moisture-induced bending deformation make MXene-based actuators promising candidates for smart switches. As shown in Fig. 4k [107], the MCPM actuator functions as a moisture-sensitive smart switch to alert against rising water levels; it can operate without physical contact with water. Zhao et al. demonstrated a bilateral switch constructed from MXene-coated paper/polyethylene film composite [110], presenting a promising methodology for environmental temperature and humidity monitoring. With the change in temperature and RH, the corresponding LED lights up according to the bending direction of the switch. MXene-based actuators can also be used as smart shielding curtain by combining their actuation performance with electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding property. Our group manufactured a smart shielding curtain using asymmetric MXene film, which can be actuated by moisture, light, and electricity. As displayed in Fig. 4l [90], light irradiation causes the smart curtain to open automatically, thereby allowing electromagnetic waves to enter the chamber. When moisture is applied, the smart curtain closes automatically to protect the chamber from external electromagnetic radiation and pollution. The smart curtain exhibited outstanding electromagnetic shielding performance of up to 69 dB.

Although MXene actuators have demonstrated promising application potential in fields such as smart grippers, biomimetic robots, and smart curtains, their practical applicability is directly constrained by their inherent limitations in mechanical strength, long-term stability, and cyclic reliability.

This review summarizes recent advances in MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators. Due to abundant oxygen-containing groups on MXene sheets, MXene films exhibit strong hydrophilic interaction with water. This characteristic enables sensitive moisture-responsiveness and efficient moisture-driven actuation. By constructing gradients based on material, structure, and moisture, the bending deformation of MXene-based actuators can be achieved, allowing potential applications in smart grippers, bioinspired soft robots, switches and curtains. It can be found that, while MXene has garnered extensive research attention in moisture-responsive actuators and notable progress has been achieved, the research in this field is quite new, and the full potential of MXenes has yet to be fully exploited. From our perspective, there are many challenges and opportunities in this field.

First, the oxidation sensitivity of MXene remains a major concern, and its impact on long-term performance is particularly prominent. In humid and oxygen-containing environments, MXene is prone to slow oxidation, which damages its two-dimensional structure. This not only reduces electrical conductivity but also significantly diminishes moisture or thermal response kinetics. For instance, an MXene-based actuator may see a 30%–50% drop in bending speed and amplitude after 1–2 months of exposure to ambient conditions (25°C, 50% relative humidity), directly undermining long-term operational reliability. Although surface modification (such as introducing antioxidants) or regulating storage environments (such as low-humidity encapsulation) can delay oxidation, these strategies have limitations. Antioxidants may leave residues that affect subsequent applications, and long-term stability in complex environments is difficult to ensure. The sensitivity of MXene to environmental factors such as temperature and pH further restricts its application in extreme conditions. Second, most MXene-based actuator applications remain in the conceptual stage. The mechanical durability, large-scale fabrication hurdles, and cost/environmental implications are major barriers to their practicalization. To function reliably across diverse environments, these actuators require robust mechanical durability and environmental resistance. These factors are, however, neglected in existing studies. Future designs should prioritize constructing MXene actuators with excellent mechanical properties. For example, hybrid systems of MXenes with hydrogels, polymers, or bioactive ceramics have vast promise to break through current bottlenecks in MXene actuators. Current MXene synthesis mainly relies on hazardous HF etching, which is dangerous, costly, and environmentally unfriendly. Even with alternative fluoride-free etchants, achieving uniform MXene flake size (100 nm–5 μm) and layer thickness across large batches remains difficult. Additionally, assembling MXene into actuator structures (e.g., Janus films, composite membranes) requires precise control over film uniformity and interface bonding. Lab-scale techniques like spin-coating or vacuum filtration are slow and not scalable, while large-scale methods like roll-to-roll coating often introduce defects (e.g., pinholes, wrinkles) that degrade performance.

Third, most reported MXene actuators are based on 2D films. Actuator design may necessitate transitions from one-dimensional (1D) fibers to complex three-dimensional (3D) structures to expand functionality. Compared to 2D films, 1D MXene fibers can be woven or assembled into complex architectures, enabling tailored properties for specific applications. 1D fiber-based actuators can be integrated into wearable devices, providing more conformable and stretchable actuation compared to flat 2D films. 3D MXene structures, including foams, hydrogels, and 3D-printed constructs, offer even greater potential for functional integration.

Finally, current research on MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators focuses mainly on actuation performance, such as response speed, actuation force, and deformation magnitude. To propel the practical implementation of MXene-based actuators in soft robotic systems, future research must concentrate on holistic system integration. This includes the seamless incorporation of essential functional modules, including sensing units for environmental feedback, energy management modules for stable power supply, and communication units for signal transmission. Only through such integration can MXene actuators effectively transition from laboratory prototypes to real-world applications.

Addressing these multifaceted challenges in the field of MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators requires collaborative innovation from interdisciplinary experts across materials science, mechanical engineering, and electrical engineering. It is expected that significant breakthroughs will be achieved in MXene-based moisture-responsive actuators in the near future.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This work was financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFB3812800), the Joint Fund for Regional Innovation and Development of National Natural Science Foundation China (No. U24A2078), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 52173181, 51973155, 52205599), Tianjin Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (22JCJQJC00060), the Youth Science Fund Program of Shanxi Province (202203021212203), and China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (No. 2024M752361).

Author Contributions: Paper conception and design: Jia-Nan Ma; data collection: Yuan Liu, Jia-Hui Zhang, Qian Zhao; draft manuscript preparation: Jia-Nan Ma; reviewing it critically for important intellectual content: Jia-Hui Zhang; final approval of the version to be published: Ling Wang. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Jia-Nan Ma, upon reasonable request.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

List of Abbreviations

| CNF | Cellulose nanofibers |

| GA | Gallic acid |

| PDMM | Polydopamine-modified MXene |

| BCNF | Bacterial cellulose nanofiber |

| PDA | Polydopamine |

| CCNT | Charged carbon nanotubes |

| PMETAC | Poly[2-(methacryloyloxy) ethyltrimethylammonium chloride] |

| TA | Tannic acid |

| CMC | Carboxymethyl cellulose |

| MT | Tannic acid-modified MXene |

| BC | Bacterial cellulose nanofiber |

| ANF | Aramid nanofiber |

| MXN | MXene-NiFe2O4 |

| VO2 | Vanadium dioxide |

| PMMA | Poly(methyl methacrylate) |

| PE | Polyethylene |

| MPE | MXene/polyethylene |

| PVA | Polyvinyl alcohol |

References

1. Pu W, Wei F, Yao L, Xie S. A review of humidity-driven actuator: toward high response speed and practical applications. J Mater Sci. 2022;57(26):12202–35. doi:10.1007/s10853-022-07344-z. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Lin S, Ma SQ, Chen KZ, Zhang YY, Lin ZH, Liang YH, et al. A humidity-driven film with fast response and continuous rolling locomotion. Chem Eng J. 2024;495:153294. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.153294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Li XF, Du YM, Xiao C, Ding X, Pan XS, Zheng K, et al. Tendril-inspired programmable liquid metal photothermal actuators for soft robots. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(4):2310380. doi:10.1002/adfm.202310380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Zhu CS, Yang SY, Wang MG, Zeng YS, Chu LY, Xie WW, et al. Polydopamine coated MXene and cellulose nanocrystal as photothermal and reinforcing nanofiller for liquid crystal elastomer-based light-driven soft actuator. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2025;695:137834. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2025.137834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Zhang YL, Li JC, Zhou H, Liu YQ, Han DD, Sun HB. Electro-responsive actuators based on graphene. Innovation. 2021;2(4):100168. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2021.100168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Wang YH, Ye HT, He J, Ge Q, Xiong Y. Electrothermally controlled origami fabricated by 4D printing of continuous fiber-reinforced composites. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):12441. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-46591-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Yang L, Liu Y, Bi R, Chen YH, Valenzuela C, Yang YZ, et al. Direct-ink-written shape-programmable micro-supercapacitors with electrothermal liquid crystal elastomers. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;2025:2504979. doi:10.1002/adfm.202504979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Kim MS, Heo JK, Rodrigue H, Lee HT, Pané S, Han MW, et al. Shape memory alloy (SMA) actuators: the role of material, form, and scaling effects. Adv Mater. 2023;35(33):2208517. doi:10.1002/adma.202208517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Wu S, Hong YY, Zhao Y, Yin J, Zhu Y. Caterpillar-inspired soft crawling robot with distributed programmable thermal actuation. Sci Adv. 2023;9(12):eadf8014. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adf8014. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. He YH, Han YC, Yu Z, Wang WY, Chen ST, Osman A, et al. Multifunctional origami magnetic-responsive soft actuators with modular designs. J Mater Sci Technol. 2025;232:103–14. doi:10.1016/j.jmst.2025.01.033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. He Y, Tang J, Hu Y, Yang S, Xu F, Zrínyi M, et al. Magnetic hydrogel-based flexible actuators: a comprehensive review on design, properties, and applications. Chem Eng J. 2023;462:142193. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.142193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Vaghasiya JV, Mayorga-Martinez CC, Zelenka J, Sharma S, Ruml T, Pumera M. Magnetic soft centirobot to mitigate biological threats. SmartMat. 2024;5(6):e1289. doi:10.1002/smm2.1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Jung Y, Kwon K, Lee J, Ko SH. Untethered soft actuators for soft standalone robotics. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):3510. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-47639-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Liu H, Liu RA, Chen K, Liu YY, Zhao Y, Cui XY, et al. Bioinspired gradient structured soft actuators: from fabrication to application. Chem Eng J. 2023;461:141966. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.141966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Li M, Pal A, Aghakhani A, Pena-Francesch A, Sitti M. Soft actuators for real-world applications. Nat Rev Mater. 2022;7(3):235–49. doi:10.1038/s41578-021-00389-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Rumley EH, Preninger D, Shomron AS, Rothemund P, Hartmann F, Baumgartner M, et al. Biodegradable electrohydraulic actuators for sustainable soft robots. Sci Adv. 2023;9(12):eadf5551. doi:10.1126/sciadv.adf5551. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang L, Xing S, Yin H, Weisbecker H, Tran HT, Guo Z, et al. Skin-inspired, sensory robots for electronic implants. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4777. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-48903-z. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

18. Park J, Lee Y, Cho S, Choe A, Yeom J, Ro YG, et al. Soft sensors and actuators for wearable human-machine interfaces. Chem Rev. 2024;124(4):1464–534. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.3c00356. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Xu HF, Wu S, Liu Y, Wang XP, Efremov AK, Wang L, et al. 3D nanofabricated soft microrobots with super-compliant picoforce springs as onboard sensors and actuators. Nat Nanotechnol. 2024;19(4):494–503. doi:10.1038/s41565-023-01567-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Wang B, Lu Y. Multi-dimensional micro/nanorobots with collective behaviors. SmartMat. 2024;5(5):e1263. doi:10.1002/smm2.1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Yu YS, Ma TY, Wei Q, Sun W, Tang JT, Yu GP, et al. Highly conductive, stable, and self-healing mxene-based hydrogel sensor via a controlled assembly of polydopamine and cellulose nanocrystal. Energy Environ Mater. 2025:0e70105. doi:10.1002/eem2.70105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chimerad M, Borjian P, Pathak P, Fasano J, Cho HJ. A miniaturized, fuel-free, self-propelled, bio-inspired soft actuator for copper ion removal. Micromachines. 2024;15(10):1208. doi:10.3390/mi15101208. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Liu JQ, Xu LL, Ji QX, Chang LF, Hu Y, Peng QY, et al. A MXene-based light-driven actuator and motor with self-sustained oscillation for versatile applications. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(4):2310955. doi:10.1002/adfm.202310955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Wang YC, Liu JQ, Yang S. Multi-functional liquid crystal elastomer composites. Appl Phys Rev. 2022;9(1):011301. doi:10.1063/5.0075471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Khalid MY, Arif ZU, Tariq A, Hossain M, Khan KA, Umer R. 3D printing of magneto-active smart materials for advanced actuators and soft robotics applications. Eur Polym J. 2024;205:112718. doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2023.112718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Zhou HR, Zhu YH, Yang BB, Huo YH, Yin YY, Jiang XM, et al. Stimuli-responsive peptide hydrogels for biomedical applications. J Mater Chem B. 2024;12(7):1748–74. doi:10.1039/d3tb02610h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Yang P, Zhu F, Zhang ZB, Cheng YY, Wang Z, Li YW. Stimuli-responsive polydopamine-based smart materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2021;50(14):8319–43. doi:10.1039/d1cs00374g. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Ma SS, Xue P, Tang YQ, Bi R, Xu XH, Wang L, et al. Responsive soft actuators with MXene nanomaterials. Responsive Mater. 2024;2:e20230026. doi:10.1002/rpm.20230026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Vazquez-Perez FJ, Gila-Vilchez C, Leon-Cecilla A, de Cienfuegos L A, Borin D, Odenbach S, et al. Fabrication and actuation of magnetic shape-memory materials. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(45):53017–30. doi:10.1021/acsami.3c14091. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yarali E, Mirzaali MJ, Ghalayaniesfahani A, Accardo A, Diaz-Payno PJ, Zadpoor AA. 4D printing for biomedical applications. Adv Mater. 2024;36(31):2402301. doi:10.1002/adma.202402301. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Li SP, Zhang JQ, He J, Liu WP, Wang YH, Huang ZJ, et al. Functional PDMS elastomers: bulk composites, surface engineering, and precision fabrication. Adv Sci. 2023;10(34):2304506. doi:10.1002/advs.202304506. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Ma SS, Xue P, Valenzuela C, Zhang X, Chen YH, Liu Y, et al. Highly stretchable and conductive MXene-encapsulated liquid metal hydrogels for bioinspired self-sensing soft actuators. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(7):2309899. doi:10.1002/adfm.202309899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Xue P, Chen YH, Xu YY, Valenzuela C, Zhang X, Bisoyi HK, et al. Bioinspired MXene-based soft actuators exhibiting angle-independent structural color. Nano-Micro Lett. 2023;15(1):1. doi:10.1007/s40820-022-00977-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Li WW, Lou CC, Liu S, Ma Q, Liao GJ, Leung KC. F, et al. Climbing plant-inspired multi-responsive biomimetic actuator with transitioning complex surfaces. Adv Funct Mater. 2025;35(6):2414733. doi:10.1002/adfm.202414733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Li YN, Fu CL, Huang LL, Chen LH, Ni YH, Zheng QH. Cellulose-based multi-responsive soft robots for programmable smart devices. Chem Eng J. 2024;498:155099. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.155099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Chen YH, Qu MJ, Liu CS, Li SH, Wang XC, Gong DX, et al. A sensitive humidity-responsive actuator based on dispersing graphene oxide into chitosan- sodium alginate nanofibers. Chem Eng J. 2025;515:163927. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2025.163927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Lan CT, Liang MC, Meng J, Mao QH, Ma WJ, Li M, et al. Humidity-responsive actuator-based smart personal thermal management fabrics achieved by solar thermal heating and sweat-evaporation cooling. ACS Nano. 2025;19(8):8294–302. doi:10.1021/acsnano.4c18643. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Cheng ZQ, Hua YY, Zhang DS, Wang MX, Ge X, Shen YXR, et al. Bilayer oriented nanofiber membrane for enhancing response deformation and stability of humidity-responsive actuator. Chem Eng J. 2025;506:160260. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2025.160260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Ejehi F, Vafaiee M, Bavi O, Maymand VM, Asadian E, Mohammadpour R. Asymmetric flexible graphene oxide papers for moisture-driven actuators and water level indicators. Alex Eng J. 2024;107:406–14. doi:10.1016/j.aej.2024.07.089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Li XY, Li JN, Zhao Y, Zhai W, Wang S, Zhang YX, et al. Multi-stimuli-responsive Ti3C2TX MXene-based actuators actualizing intelligent interpretation of traditional shadow play. Carbon. 2024;218:118652. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2023.118652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Yan WY, Feng YX, Song JJ, Hong ZX, Cui KY, Brannan AC, et al. Self-sensing dandelion-inspired flying soft actuator with multi-stimuli response. Adv Mater Technol. 2024;9(23):2400952. doi:10.1002/admt.202400952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Liu Y, Ma JZ, Yang YZ, Valenzuela C, Zhang X, Wang L, et al. Smart chiral liquid crystal elastomers: design, properties and application. Smart Mol. 2024;2(1):e20230025. doi:10.1002/smo.20230025. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Xue P, Bisoyi HK, Chen YH, Zeng H, Yang JJ, Yang X, et al. Near-infrared light-driven shape-morphing of programmable anisotropic hydrogels enabled by MXene nanosheets. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2021;60(7):3390–6. doi:10.1002/anie.202014533. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Lu W, Wang RJ, Si MQ, Zhang Y, Wu S, Zhu N, et al. Synergistic fluorescent hydrogel actuators with selective spatial shape/color-changing behaviors via interfacial supramolecular assembly. SmartMat. 2024;5(2):e1190. doi:10.1002/smm2.1190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Zhang JZ, Kong N, Uzun S, Levitt A, Seyedin S, Lynch PA, et al. Scalable manufacturing of free-standing, strong Ti3C2Tx MXene films with outstanding conductivity. Adv Mater. 2020;32(23):2001093. doi:10.1002/adma.202001093. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Kelly AC, O.Suilleabhain D, Gabbett C, Coleman JN. The electrical conductivity of solution-processed nanosheet networks. Nat Rev Mater. 2022;7(3):217–34. doi:10.1038/s41578-021-00386-w. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Fan ZM, He HY, Yu JX, Wang JF, Yin L, Cheng ZJ, et al. Binder-free Ti3C2Tx MXene doughs with high redispersibility. ACS Mater Lett. 2020;2(12):1598–1605. doi:10.1021/acsmaterialslett.0c00422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Wang Y, Fu JM, Xu JA, Hu HB, Ho DR. Atomic plasma grafting: precise control of functional groups on Ti3C2TX MXene for room temperature gas sensors. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2023;15(9):12232–9. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c22609. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Luo YJ, Que WX, Tang Y, Kang YQ, Bin XQ, Wu ZW, et al. Regulating functional groups enhances the performance of flexible microporous MXene/bacterial cellulose electrodes in supercapacitors. ACS Nano. 2024;18(18):11675–87. doi:10.1021/acsnano.3c11547. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

50. Shuck CE, Sarycheva A, Anayee M, Levitt A, Zhu YZ, Uzun S, et al. Scalable synthesis of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Adv Eng Mater. 2020;22(3):1901241. doi:10.1002/adem.201901241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Lipton J, Rohr JA, Dang V, Goad A, Maleski K, Lavini F, et al. Scalable, highly conductive, and micropatternable MXene films for enhanced electromagnetic interference shielding. Matter. 2020;3(2):546–57. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2020.05.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

52. Demirelli K, Çelik A, Aksoy Y, Yegin M, Barım E, Hanay Ö, et al. Synthesis process, thermal and electrical behaviors of Ti3C2Tx MXene. Materialwiss Werkst. 2024;55(9):1213–26. doi:10.1002/mawe.202300282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

53. Ma YA, Cheng YF, Wang J, Fu S, Zhou MJ, Yang Y, et al. Flexible and highly-sensitive pressure sensor based on controllably oxidized MXene. Infomat. 2022;4(9):e12328. doi:10.1002/inf2.12328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Guo TZ, Zhou D, Deng SG, Jafarpour M, Avaro J, Neels A, et al. Rational design of Ti3C2Tx MXene inks for conductive, transparent films. ACS Nano. 2023;17(4):3737–49. doi:10.1021/acsnano.2c11180. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Tang Y, Yang CH, Xu XT, Kang YQ, Henzie J, Que WX, et al. MXene nanoarchitectonics: defect-engineered 2D MXenes towards enhanced electrochemical water splitting. Adv Energy Mater. 2022;12(12):2103867. doi:10.1002/aenm.202103867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Zhou YX, Zhang YL, Pang YH, Guo H, Guo YQ, Li MK, et al. Thermally conductive Ti3C2Tx fibers with superior electrical conductivity. Nano-Micro Lett. 2025;17(1):235. doi:10.1007/s40820-025-01752-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Seyedin S, Zhang J, Usman KAS, Qin S, Glushenkov AM, Yanza ERS, et al. Facile solution processing of stable MXene dispersions towards conductive composite fibers. Glob Chall. 2019;3(10):1900037. doi:10.1002/gch2.201900037. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Wang JF, Liu YY, Yang YQ, Wang JQ, Kang H, Yang HP, et al. A weldable MXene film assisted by water. Matter. 2022;5(3):1042–55. doi:10.1016/j.matt.2022.01.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Wang JF, He JB, Kan DX, Chen KY, Song MS, Huo WT. MXene film prepared by vacuum-assisted filtration: properties and applications. Crystals. 2022;12(8):1034. doi:10.3390/cryst12081034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

60. Liu J, Zhang HB, Sun RH, Liu YF, Liu ZS, Zhou AG, et al. Hydrophobic, flexible, and lightweight MXene foams for high-performance electromagnetic-interference shielding. Adv Mater. 2017;29(38):1702367. doi:10.1002/adma.201702367. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

61. Liu XD, Liu Y, Dong SL, Zhang XF, Lv L, He SR. Room-temperature prepared MXene foam via chemical foaming methods for high-capacity supercapacitors. J Alloys Compd. 2023;945:169279. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2023.169279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

62. Naguib M, Mashtalir O, Carle J, Presser V, Lu J, Hultman L, et al. Two-dimensional transition metal carbides. ACS Nano. 2012;6(2):1322–31. doi:10.1021/nn204153h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Alhabeb M, Maleski K, Anasori B, Lelyukh P, Clark L, Sin S, et al. Guidelines for synthesis and processing of two-dimensional titanium carbide (Ti3C2TX MXene). Chem Mater. 2017;29(18):7633–44. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.7b02847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

64. Shi X, Yu Z, Liu Z, Cao NN, Zhu L, Liu YY, et al. Scalable, high-yield monolayer MXene preparation from multilayer MXene for many applications. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2025;64(6):e202418420. doi:10.1002/anie.202418420. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Maleski K, Mochalin VN, Gogotsi Y. Dispersions of two-dimensional titanium carbide MXene in organic solvents. Chem Mater. 2017;29(4):1632–40. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b04830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

66. Ghidiu M, Halim J, Kota S, Bish D, Gogotsi Y, Barsourm MW. Ion-exchange and cation solvation reactions in Ti3C2 MXene. Chem Mater. 2016;28(10):3507–14. doi:10.1021/acs.chemmater.6b01275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Muckley ES, Naguib M, Wang HW, Vlcek L, Osti NC, Sacci RL, et al. Multimodality of structural, electrical, and gravimetric responses of intercalated MXenes to water. ACS Nano. 2017;11(11):11118–26. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b05264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Iakunkov A, Lienert U, Sun JH, Talyzin AV. Swelling of Ti3C2Tx MXene in water and methanol at extreme pressure conditions. Adv Sci. 2024;11(9):2307067. doi:10.1002/advs.202307067. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

69. Zhang YL, Liu YQ, Han DD, Ma JN, Wang D, Li XB, et al. Quantum-confined-superfluidics-enabled moisture actuation based on unilaterally structured graphene oxide papers. Adv Mater. 2019;31(32):1901585. doi:10.1002/adma.201901585. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

70. Muckley ES, Naguib M, Ivanov IN. Multi-modal, ultrasensitive, wide-range humidity sensing with Ti3C2 film. Nanoscale. 2018;10(46):21689–95. doi:10.1039/c8nr05170d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Wang YS, Huang ML, Lu J, Zhang HW, Wang L, Feng ZS, et al. Mussel-inspired dopamine/MXene composite: improved oxidation stability for humidity sensing and non-contact monitoring. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2025;433:137533. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2025.137533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

72. An H, Habib T, Shah S, Gao HL, Patel A, Echols I, et al. Water sorption in MXene/polyelectrolyte multilayers for ultrafast humidity sensing. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2019;2(2):948–55. doi:10.1021/acsanm.8b02265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Zhang HW, Xu X, Lu J, Huang ML, Wang YS, Feng ZS, et al. Flexible non-contact printed humidity sensor: realization of the ultra-high performance humidity monitoring based on the MXene composite material. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2025;432:137481. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2025.137481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

74. Han DD, Liu YQ, Ma JN, Mao JW, Chen ZD, Zhang YL, et al. Biomimetic graphene actuators enabled by multiresponse graphene oxide paper with pretailored reduction gradient. Adv Mater Technol. 2018;3(12):1800258. doi:10.1002/admt.201800258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Liu XY, Liu J, Lin ST, Zhao XH. Hydrogel machines. Mater Today. 2020;36:102–24. doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2019.12.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

76. Lee Y, Song WJ, Sun JY. Hydrogel soft robotics. Mat Today Phys. 2020;15:100258. doi:10.1016/j.mtphys.2020.100258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Ru J, Zhu ZC, Wang YJ, Chen HL, Bian CS, Luo B, et al. A moisture and electric coupling stimulated ionic polymer-metal composite actuator with controllable deformation behavior. Smart Mater Struct. 2018;27(2):02LT01. doi:10.1088/1361-665X/aaa581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

78. Tang GQ, Zhao C, Zhao X, Mei D, Li B, Li LJ, et al. Nafion/polyimide based programmable moisture-driven actuators for functional structures and robots. Sens Actuators B Chem. 2023;393:134152. doi:10.1016/j.snb.2023.134152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Nguyen VH, Tabassian R, Oh S, Nam S, Mahato M, Thangasamy P, et al. Stimuli-responsive MXene-based actuators. Adv Funct Mater. 2020;30(47):1909504. doi:10.1002/adfm.201909504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

80. Wang JF, Ma HX, Liu YY, Xie ZM, Fan ZM. MXene-based humidity-responsive actuators: preparation and properties. Chempluschem. 2021;86(3):406–17. doi:10.1002/cplu.202000828. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Mulakkal MC, Trask RS, Ting VP, Seddon AM. Responsive cellulose-hydrogel composite ink for 4D printing. Mater Des. 2018;160:108–18. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2018.09.009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

82. Forterre Y, Skotheim JM, Dumais J, Mahadevan L. How the Venus flytrap snaps. Nature. 2005;433(7024):421–5. doi:10.1038/nature03185. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

83. Cai G, Ciou J-H, Liu Y, Jiang Y, Lee PS. Leaf-inspired multiresponsive MXene-based actuator for programmable smart devices. Sci Adv. 2019;5(7):eaaw7956. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aaw7956. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

84. Song P, Ma JN, Ma B, Wang K, Zhang DM, Li Q, et al. MXene-based bilayer structures with multiresponsive actuating and sensing multifunctions. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2024;7(8):9626–34. doi:10.1021/acsanm.4c01111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

85. Ma B, Ma JN, Song P, Wang K, Zhang DM, Li Q, et al. Quantum-confined-superfluidics-enabled multiresponsive MXene-based actuators. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(12):15215–26. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c00864. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

86. Liu BC, Ling Z, Du J, Qiu J. MXene/VO2@PMMA composite film multi-responsive actuator with amphibious motion. Small. 2025;21(17):2409341. doi:10.1002/smll.202409341. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

87. Song ZQ, Wu T, Zhang LB, Song HJ. Multi-responsive and self-sensing flexible actuator based on MXene and cellulose nanofibers Janus film. J Colloid Interface Sci. 2025;688:183–92. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2025.02.147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Cao J, Zhou ZH, Song QC, Chen KY, Su GH, Zhou T, et al. Ultrarobust Ti3C2Tx MXene-based soft actuators via bamboo-inspired mesoscale assembly of hybrid nanostructures. ACS Nano. 2020;14(6):7055–65. doi:10.1021/acsnano.0c01779. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

89. Wen LP, Zhang XQ, Tian Y, Jiang L. Quantum-confined superfluid: from nature to artificial. Sci China Mater. 2018;61(8):1027–32. doi:10.1007/s40843-018-9289-2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

90. Ma JN, Ma B, Wang ZX, Song P, Han DD, Zhang YL. Multiresponsive MXene actuators with asymmetric quantum-confined superfluidic structures. Adv Funct Mater. 2024;34(8):2308317. doi:10.1002/adfm.202308317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

91. Wang JF, Liu YY, Cheng ZJ, Xie ZM, Yin L, Wang W, et al. Highly conductive MXene film actuator based on moisture gradients. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2020;59(33):14029–33. doi:10.1002/anie.202003737. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

92. Wei J, Jia S, Wei J, Ma C, Shao Z. Tough and multifunctional composite film actuators based on cellulose nanofibers toward smart wearables. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(32):38700–11. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c09653. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

93. Ma HL, Jiang YF, Han WJ, Li X. High wet-strength, durable composite film with nacre-like structure for moisture-driven actuators. Chem Eng J. 2023;457:141353. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.141353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

94. Sun LC, Che LX, Li M, Chen K, Leng X, Long YJ, et al. Reinforced nacre-like MXene/sodium alginate composite films for bioinspired actuators driven by moisture and sunlight. Small. 2024;20(51):2406832. doi:10.1002/smll.202406832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

95. Eggert G. Saturated salt solutions in showcases: humidity control and pollutant absorption. Herit Sci. 2022;10(1):54. doi:10.1186/s40494-022-00689-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Wang YC, Pang D, He Y, Li HL, Tang Y, Ye LJ, et al. Ultrafast and multi-stimuli-responsive MXene soft actuators via heterostructure design for biomimetic applications. Adv Funct Mater. 2025:e14386. doi:10.1002/adfm.202514386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

97. He JW, Wu Z, Li BJ, Xing YQ, Huang P, Liu L. Multi-stimulus synergistic control soft actuators based on laterally heterogeneous MXene structure. Carbon. 2023;202:286–95. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2022.10.072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

98. Hou TJ, Wang SF, Li JM, Wang Y, Zhang Y, Cao L, et al. Optimal humidity-responsive actuators of heterostructured MXene nanosheets/3D-MXene membrane. Smart Mater Struct. 2023;32(6):065014. doi:10.1088/1361-665X/acd1c8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Tong X, Chen GJ, Ahommed MS, Shen XL, Sha LZ, Guo DL, et al. A carbon nanofiber/Ti3C2Tx/carboxymethyl cellulose composite-based highly sensitive, reversible, directionally controllable humidity actuator and generator via continuous track-inspired self-assembly. J Mater Chem A. 2024;12(47):33003–14. doi:10.1039/d4ta04397a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

100. Weng X, Weng ZW, Qin M, Zhang JB, Wu YC, Jiang H. Bioinspired moisture-driven soft actuators based on MXene/aramid nanofiber nanocomposite films. ACS Appl Nano Mater. 2024;7(5):5587–97. doi:10.1021/acsanm.4c00420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

101. Wei J, Jia S, Ma C, Guan J, Yan CX, Zhao LB, et al. Nacre-inspired composite film with mechanical robustness for highly efficient actuator powered by humidity gradients. Chem Eng J. 2023;451:138565. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.138565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

102. Xu TF, Pei DF, Yu SY, Zhang XF, Yi MG, Li CX. Design of MXene composites with biomimetic rapid and self-oscillating actuation under ambient circumstances. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2021;13(27):31978–85. doi:10.1021/acsami.1c06343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Wei J, Ma C, Zhang TT, Shao ZQ, Chen YX. High-performance cellulose nanofibers-based actuators with multi-stimulus responses and energy storage. Chem Eng J. 2024;490:151393. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.151393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

104. Yang LY, Cui J, Zhang L, Xu XR, Chen X, Sun DP. A moisture-driven actuator based on polydopamine-modified MXene/bacterial cellulose nanofiber composite film. Adv Funct Mater. 2021;31(27):2101378. doi:10.1002/adfm.202101378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

105. Li ZM, Xu WJ, Song KX, Zhang J, Liu Q, El-Bahy ZM, et al. Cellulose nanofibers-based composite film with broadening MXene layer spacing and rapid moisture separation for humidity sensing and humidity actuators. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;278:134383. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134383. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

106. Wu JX, Ai WF, Long Y, Song K. MXene-based soft humidity-driven actuator with high sensitivity and fast response. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;16(21):27650–6. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c04111. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Li PD, Su N, Wang ZY, Qiu JS. A Ti3C2Tx MXene-based energy-harvesting soft actuator with self-powered humidity sensing and real-time motion tracking capability. ACS Nano. 2021;15(10):16811–8. doi:10.1021/acsnano.1c07186. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

108. Huang WW, Zhou JY, Zhang Y, Sun YN, Yang DY, Tang JG, et al. Programmable Wrinkled MXene-based soft actuators with moisture- and light-responsive deformation and water-surface locomotion capabilities. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2024;17(1):2624–34. doi:10.1021/acsami.4c18410. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

109. Ma JN, Zhang YL, Liu YQ, Han DD, Mao JW, Zhang JR, et al. Heterogeneous self-healing assembly of MXene and graphene oxide enables producing free-standing and self-reparable soft electronics and robots. Sci Bull. 2022;67(5):501–11. doi:10.1016/j.scib.2021.11.015. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

110. Zhao TT, Liu H, Yuan L, Tian XM, Xue XY, Li TK, et al. A multi-responsive MXene-based actuator with integrated sensing function. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2022;9(10):2101948. doi:10.1002/admi.202101948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools