Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Self-Assembly of Active Ingredients in Natural Traditional Chinese Medicine as the Controlled Drug Delivery and Targeted Treatment

College of Pharmacy, Anhui University of Chinese Medicine, Hefei, 230012, China

* Corresponding Author: Hongmei Xia. Email:

# These authors contributed equally to this work and should be co-first authors

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Polymer Materials in Controlled Drug Delivery)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 993-1033. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.071740

Received 11 August 2025; Accepted 01 December 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) has a long history and is widely used to prevent and treat various diseases. With the development of modern technology, an increasing number of active ingredients—such as curcumin, berberine, and baicalin—have been identified and validated within TCM. Concurrently, the emergence of nanotechnology has led to the discovery of numerous nanomedicines based on the self-assembly of active ingredients from TCM. Polymer materials can enhance the bioavailability of these active compounds and reduce their toxic side effects. Moreover, compared to synthetic polymers, natural polymer materials offer advantages such as non-toxicity and high biosafety when used in drug delivery systems. However, natural polymers tend to be unstable and are easily influenced by environmental factors such as temperature, humidity, and pH, which complicates quality control. Additionally, the cost of obtaining natural polymer materials remains high. This article summarizes and analyzes 232 pieces of the research studies on self-assembled polymer materials via noncovalent interactions, including hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic interactions. The review primarily focuses on the active ingredients derived from TCM and provides a concise overview of future directions for polymer materials, including controlled drug delivery, targeted disease treatment, clinical translation, and green synthesis methods.Keywords

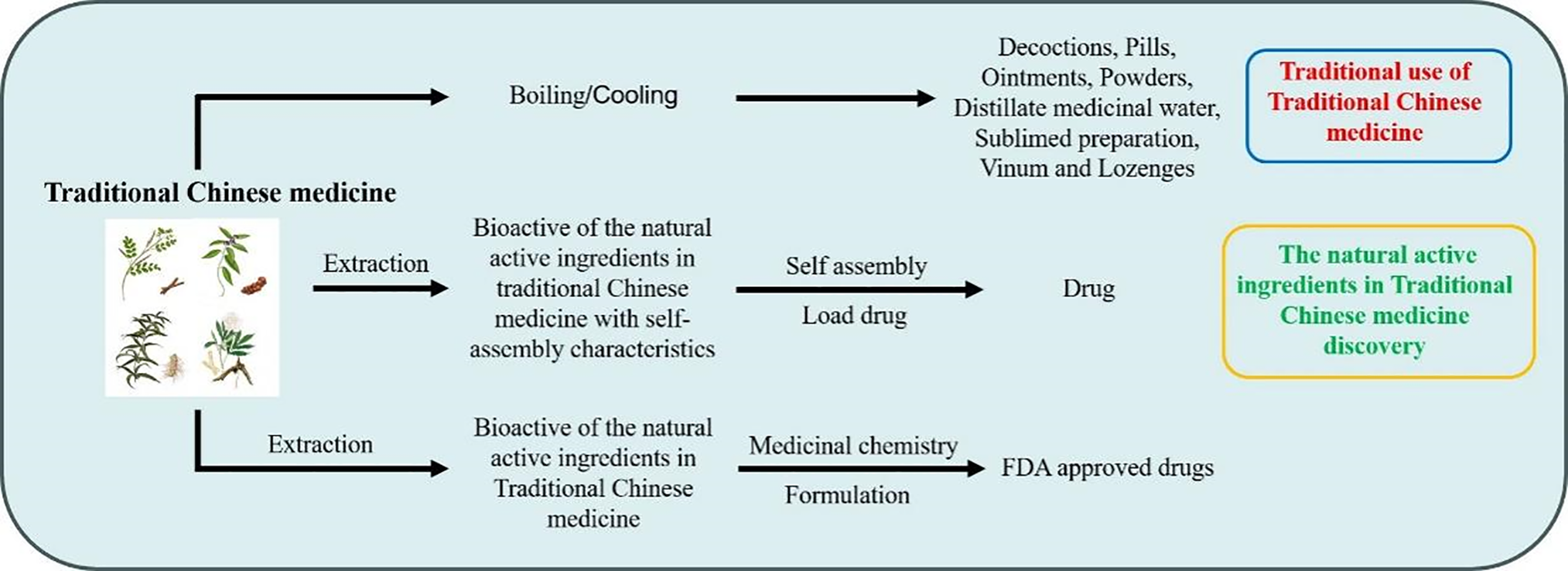

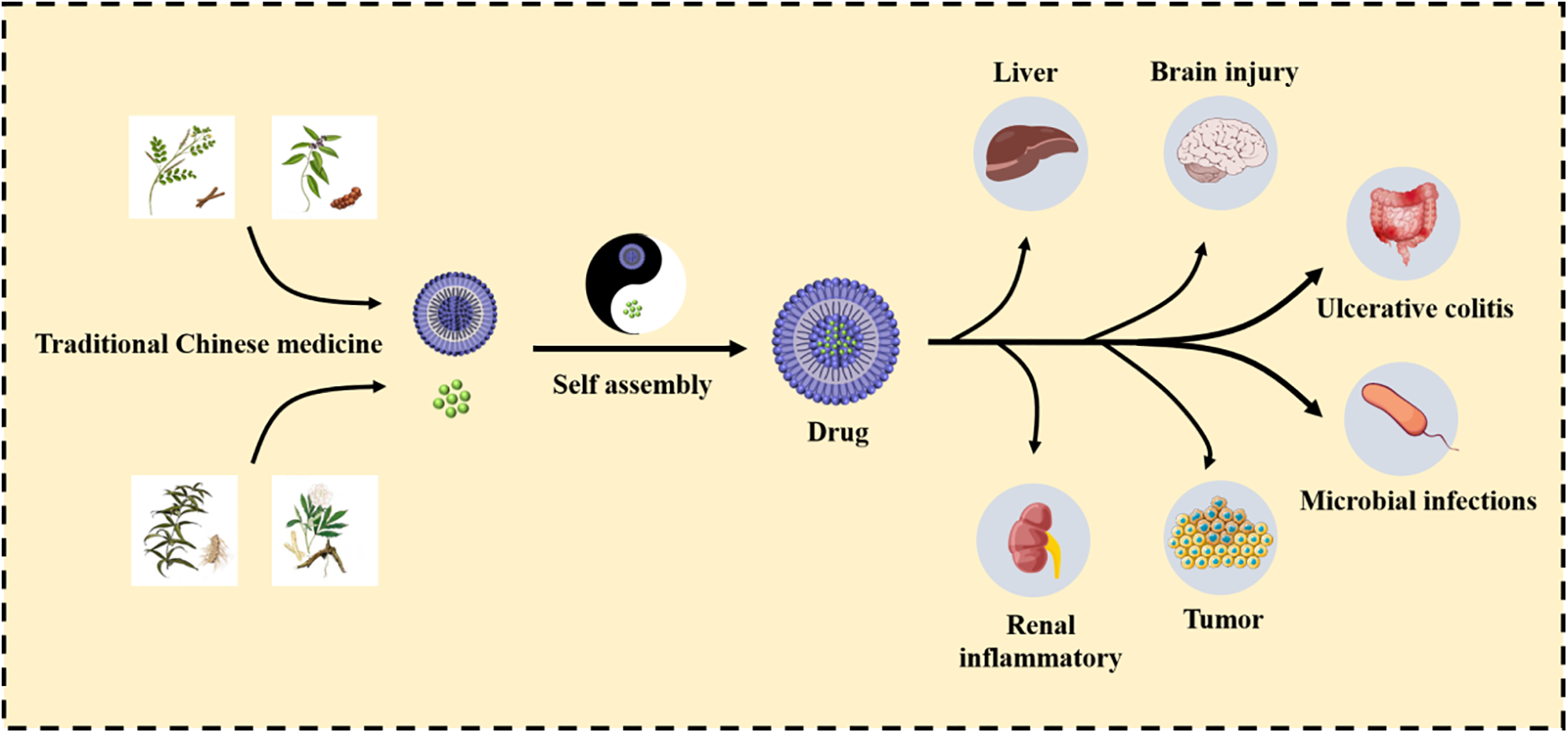

Traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), which includes plants, animals, minerals, and other substances, has a long history. With the discovery and validation of an increasing number of natural active ingredients in TCM [1], many compounds in TCM have been proven to be beneficial for health and disease treatment. In recent decades, approximately 60% of drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration are derived from natural products [2]. Consequently, esearchers have increasingly focused on the natural active ingredients in Traditional Chinese Medicine (NAI-TCM). However, most NAI-TCM are limited in clinical application due to their strong hydrophobicity, low bioavailability, short half-life, poor in vivo stability, systemic toxicity within the therapeutic dose range [3–5]. With the advancement of emerging nanotechnology, innovations in TCM active ingredients—including drug self-assembly delivery systems [6] and polymer materials—have been developed as the controlled drug delivery systems (Fig. 1) [7].

Figure 1: Schematic diagram of the application of traditional Chinese medicine in traditional medicine, drug discovery, and nanomaterial discovery

Drug delivery systems typically refer to systems that effectively deliver drugs to the target organ, while regulating drug distribution in the body and controlling drug release. At present, according to the different sources of polymer materials, they can be divided into two categories: synthetic and natural drug delivery systems. Synthetic drug delivery systems are mainly composed of organic polymer materials, such as polycaprolactone, polylactic acid, polyethylene glycol, etc., which have homogeneity, stability, and good mechanical properties. With the advancement of nanotechnology, inorganic nanocarriers with multifunctional properties are gradually favored, such as the most representative mesoporous silica. Their mesoporous structure and high specific surface area can significantly increase drug loading, and the active silica groups in the surface make it easy to undergo chemical modification to protect and control drug release. Moreover, polymer materials as nanocarriers also have advantages such as targeted drug delivery, enhanced drug permeability, increased water solubility, and retention effects [8–13]. However, there are still problems such as poor drug loading capacity, and almost all nanocarriers themselves have no therapeutic effect. Meanwhile, due to the fact that nanocarriers such as silica, metal ions, and magnetic nanoparticles are usually inert materials [14,15], they cannot be eliminated through human metabolism, which may increase the systemic toxicity of patients and bring additional burdens to them [15–18]. Compared with synthetic materials, natural polymer materials have advantages such as non-toxicity, high biosafety, wide sources, and renewability when constructing drug carrier delivery systems. Therefore, the construction of drug delivery systems using natural materials is increasingly receiving attention.

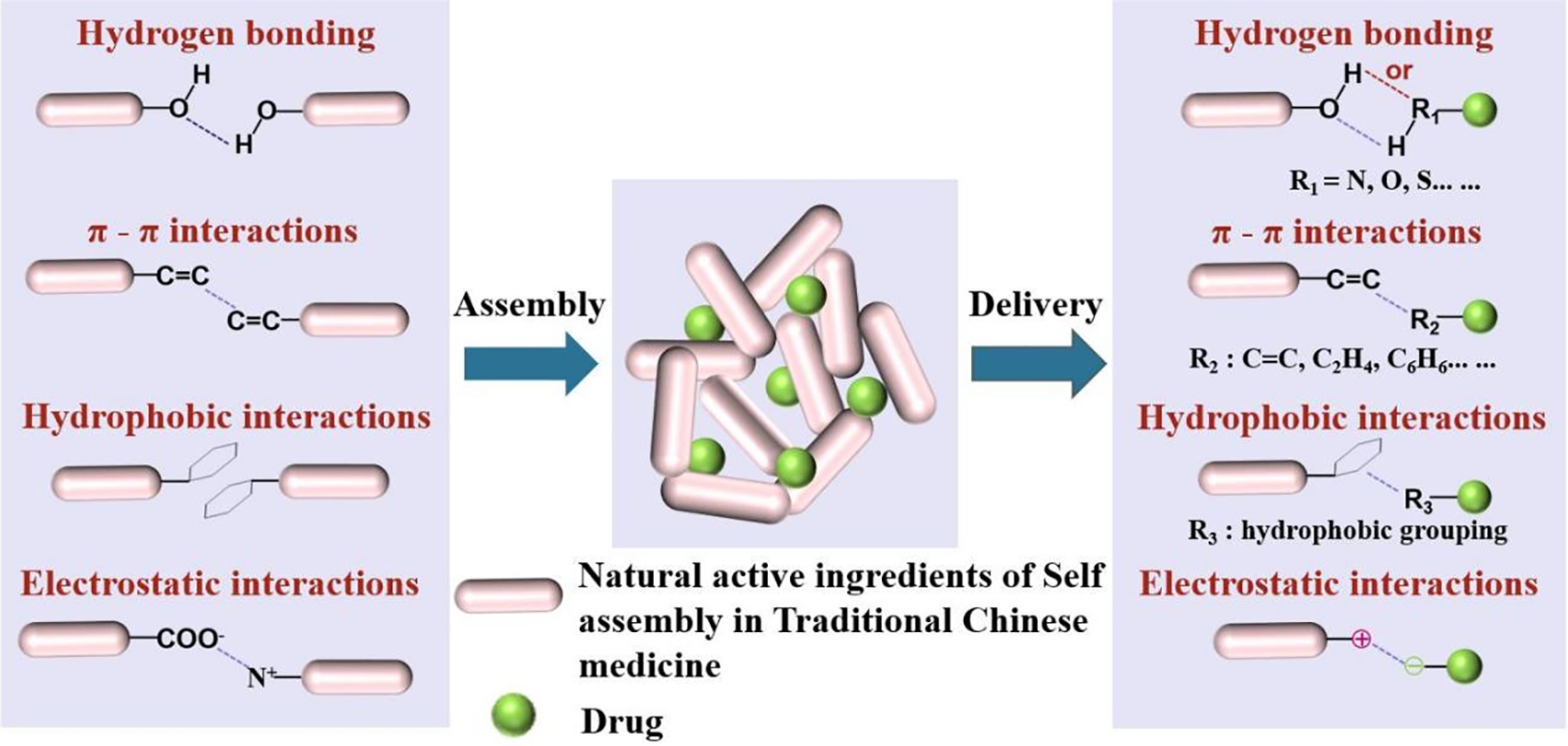

The eight common dosage forms of TCM include decoctions, pills, ointments, powders, distillate medicinal water, sublimed preparation, vinum and lozenges. Among them, decoction is the most commonly used TCM dosage form in clinical treatment. It has been observed that the natural active ingredients in Traditional Chinese medicine (NAI-TCM) with limited bioavailability can exert their pharmacological activities in TCM after being decocted, which has attracted the attention of scientists [19]. It has been found that the NAI-TCM, after being boiled, generate a soluble and complex multi-component system composed of solutes, aggregates, colloids, and precipitates through intermolecular forces such as hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces [19,20]. So far, researchers have found that many single-molecule active compounds or pairs of active compound molecules can self-assemble into the nanosystems for self-delivery, such as triterpenes [21], anthraquinones, proteins [22], and polysaccharides [23]. In addition, self-assembled nanostructures can also serve as carriers for drug delivery, encapsulating therapeutic drugs through noncovalent intermolecular interactions (Fig. 2) [24]. Although reports on the co-assembly of three or more TCM are limited, such assemblies can be achieved through the coordination of various weak bonding interactions. Compared to conventional nanocarriers, self-assembled delivery systems using NAI-TCM offer several advantages, including improved drug loading efficiency, avoidance of metabolic challenges and toxicity associated with nanocarriers, and the retention of the unique pharmacological activities of NAI-TCM themselves (such as biological activity and synergistic effects targeting multiple tissues and pathways). However, practical challenges remain, including issues of reproducibility, scalability, batch stability, and regulatory compliance.

Figure 2: The self-assembly of natural active ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine into nanoparticles can serve as delivery carriers to encapsulate drugs

The review focus on self-assembled delivery systems of NAI-TCM as follows.

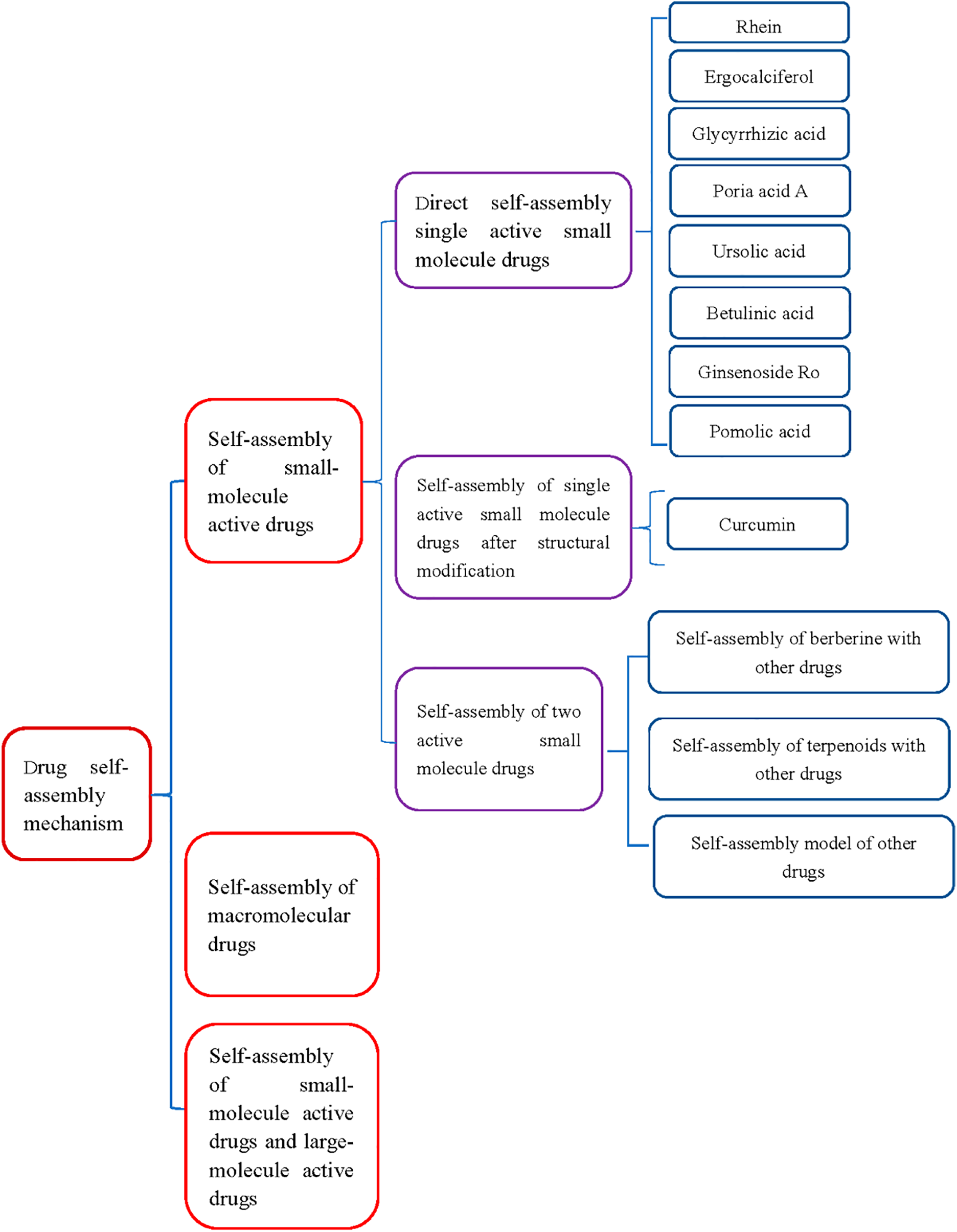

2 Drug Self-Assembled Mechanism

The process of drug self-assembly is a spontaneous process driven by thermodynamics and kinetics. These NAI-TCM drug molecules drive self-assembly in solvents through highly specific noncovalent interactions between adjacent molecules, generating complex and ordered nanostructures (Fig. 3). Noncovalent interactions include hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic interactions.

Figure 3: Schematic diagram of the self-assembly of natural active ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine into nanoparticles through various noncovalent interactions (hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, hydrophobic interactions, and electrostatic interactions)

Among them, hydrogen bonds and π-π interactions play important roles in the self-assembled process [24–26]. The bond energy of hydrogen bonds is between covalent bonds and van der Waals forces. It can maintain a certain structural stability and has dynamic reversibility. The existence of hydrogen bonds determines the conformation and self-assembled structure of molecules, affecting their physical and chemical properties. Hydrogen bonding plays a crucial role in life sciences, polymer materials science, pharmaceuticals, and other fields. The nucleic acid structure of DNA and RNA is a large molecular spiral structure composed of regularly repeating polymers formed from nucleotides. The alpha helix and beta fold structures of peptides and proteins rely on hydrogen bonds to maintain stability, determining the replication and transmission of genetic information, affecting genetics, variation, protein expression, biocatalysis, and more. The π-π interaction is weaker than hydrogen bonding, but it can have significant effects in polyaromatic systems through multi-point superposition. Aromatic rings are widely present in biomolecules, such as DNA base stacking that stabilizes the double helix structure, and interactions between aromatic amino acid side chains in proteins.

The self-assembled morphology of drugs is related to the self-assembled forces between drugs. The same or different self-assembled forces between drugs may ultimately result in different self-assembled forms [27–30] For example, it was found that berberine and flavonoid glycoside baicalin and wogonoside, which are also controlled by electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, ultimately form two different nano forms: nanoparticles (NPs) and nanofibers (NFs) when self-assembly with baicalin and berberine. And these two different nanostructures exhibit diametrically opposite antibacterial properties. These two diametrically opposite antibacterial properties may be due to the different spatial configurations and self-assembled processes that form NPs and NFs [31].

3 Application of Self-Assembly of Small-Molecule Active Drugs

3.1 Direct Self-Assembly of Single Active Small Molecule Drugs

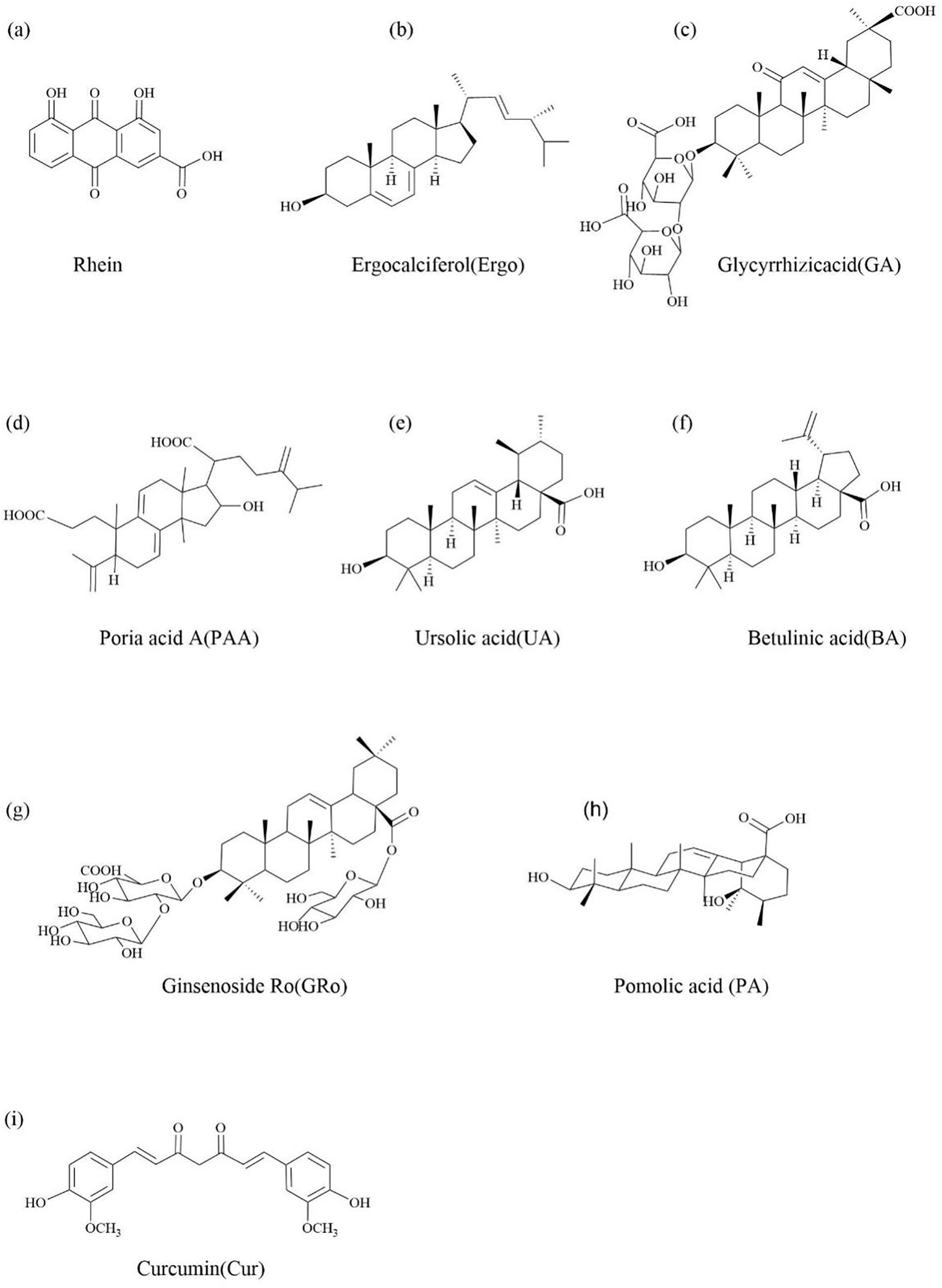

Rhein is the main anti-inflammatory component of the TCM rhubarb, a lipophilic anthraquinone compound (Fig. 4a) [32]. In the treatment of brain injury including neurodegenerative diseases and traumatic brain injury, rhein exerts neuroprotective effects through anti-inflammation [33]. However, rhein solubility is still poor, and glucuronide metabolism in the liver showed low bioavailability, thus hindering clinical translation [34]. Several efforts to prepare polymeric particles and nanoparticles containing rhodizonate have been attempted in order to improve therapeutic efficacy and reduce adverse effects [35,36]. However, drug loss during fabrication and premature payload release still result in lower drug loading and undesirable systemic toxicity [37].

Figure 4: The chemical structure of single natural active ingredients in Traditional Chinese medicine as the small molecule drugs that can undergo direct self-assembly

Rhein as an anthraquinone compound, which can directly self-assemble into a three-dimensional network structure supramolecular hydrogel composed of nanofibers through intermolecular π-π interaction and hydrogen bond noncovalent interaction. The gel has good biological stability, drug release and reversible stimulation response. Both rhein-loaded hydrogel and the same dosage of free drug (15 μΜ of rhein and rhein hydrogel) had no cytotoxicity at 24 h, while the free drug significantly reduced the viability of BV2 cells by 22% compared with rhein-loaded hydrogel at 48 h (40 μm), which indicated that the cytotoxicity of rhein-loaded hydrogel was lower than that of free drug in the process of slow and continuous release. In particular, on the one hand, this hydrogel has a three-dimensional structure, which can prevent the premature degradation of rhein, and has a better lasting anti neuroinflammatory effect than its free drug form. On the other hand, nanofibers are more likely to enter cells than free drugs.

In addition, there are strong hydrogen bonds and hydrogen oxygen interactions between rhein and toll like receptor 4 (TLR4) residues, which help to tightly bind to TLR4 and achieve better accumulation, enabling it to concentrate on the active site of TLR4. This allowed rhein hydrogels to significantly dephosphorylate IκBα and inhibit lipopolysaccharide-induced nuclear translocation of p65 on the NF-κB signaling pathway in BV2 microglia.

Therefore, compared with free drugs, rhein in hydrogel essentially improved the therapeutic effect and reduced adverse reactions. These characteristics might make rhein in hydrogel a kind of anti-neuritis drug. But the findings are preliminary and need further validation in animal models or clinical studies.

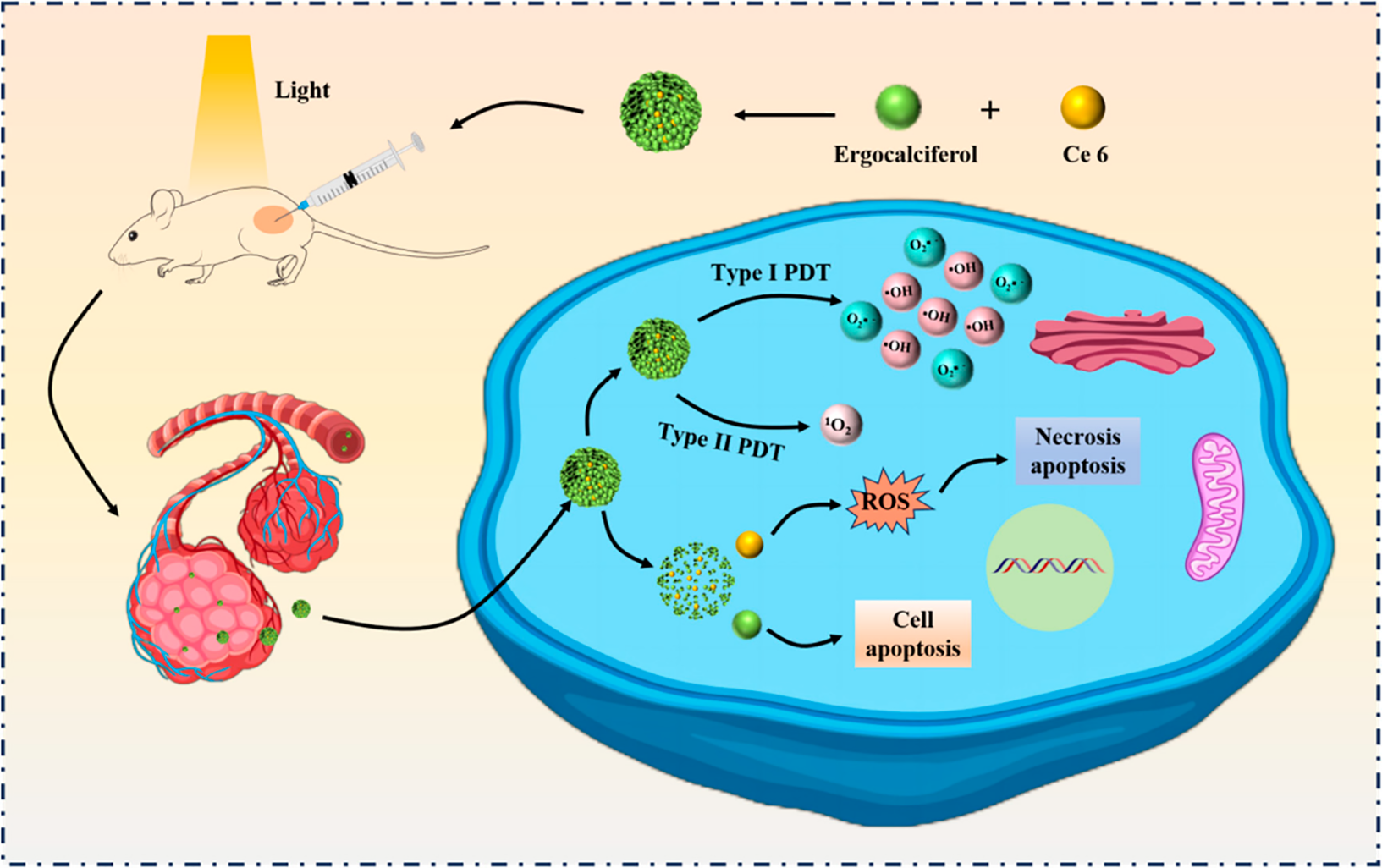

Ergosterol is a steroid with anti-cancer activity and the ability to self-assemble into gels. It is extracted from mushrooms such as Pleurotus ostreatus and Polyporus umbellatus (Fig. 4b) [38,39].

It was found that ergosterol initially forms a dimer through hydrogen bonding, followed by the development of a laminar secondary structure through periodic vertical or horizontal growth accompanied by pairwise stacking (π-π stacking interactions). These structures then continuously aggregate within in emulsion droplets of limited area, resulting in the formation of rod-like nanostructured Ergo NPs. Compared to free ergosterol, these Ergo NPs exhibit enhanced anticancer activity activity, as well as improved biocompatibility and biodegradability [40].

Photodynamic therapy (PDT) is a novel cancer treatment, in which photosensitizers (PSs) play a crucial role. In the presence of tissue oxygen, the PSs accumulated by irradiated tumors will generate highly cytotoxic reactive oxygen species (ROS) through two photodynamic reactions, including the Type I mechanism, producing oxidative products such as superoxide anion (O2▪−), Hydroxyl radicals (▪OH) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), as well as the type II mechanism for producing singlet oxygen (1O2) [41]. Chlorin e6 (Ce6) is the most commonly used PSs, which can solve the problems of low targeting selectivity and low bioavailability of PSs towards tumors [42]. Cheng et al. [40] used a standard emulsion solvent evaporation method to incorporate the Ce6 in a monomeric state through intermolecular π-π stacking and hydrophobic interactions. The Ergo-Ce6 NPs with homogeneous rod-like nanostructures were formed, which tended to form spherical nanoparticles (Fig. 5). Meanwhile, in order to screen the most ideal carriers, Ce6 was encapsulated in the same way to isolate and extract stigmasterol and β-sitosterol with self-assembled ability from taxus chinensis and artemisia annua, respectively. Among the three tested NPs, Ergo NPs had the smallest volume and lower polydispersity values, and the Ergo-Ce6 NPs with Ce6 after encapsulation had relatively better anti-tumor activity. The strong PDT effect induced by Ergo Ce6 NPs is speculated to be dominated by type I reaction (The production of O2▪− and ▪OH are more than that of 1O2). Therefore, Ergo-Ce6 NPs were selected for further in vitro and in vivo systemic studies. Compared with Ergo NPs, Ergo-Ce6 NPs showed significant in vitro phototoxicity against 4T1 and michigan cancer foundation-7 (MCF-7) cancer cells at lower doses (1 μg/mL) of Ce6, with 73% and 92% inhibition rates, respectively, due to their increased water solubility, stability and higher intercellular ROS production rate. In addition, the excellent tumor targeting ability and prolonged blood circulation of Ergo NPs led to the rapid accumulation of Ergo-Ce6 NPs in tumors with a significantly higher in vivo antitumor efficiency of 86.4%, which was higher than that of Ergo NPs (51.0%) and Ce6 PDT alone (59.5%).

Figure 5: Schematic illustration of supramolecular photosensitizer Ergo-Ce6 NPs for efficiently combined antitumor therapy. Natural self-assembled sterols (Stigmasterol, Ergosterol, β-Stiosterol) with anticancer activity were selected as single component active carrier, and ergosterol was screened to deliver Ce6 for efficiently generation of ROS by promoting Type I PDT reactions, thus resulting in significantly combined tumor therapy

Moreover, the resulting nanodrugs have better biocompatibility, biodegradability and low toxicity in vivo, which ensure the safety of tumor treatment and provide a broad prospect for the preparation of novel drug photosensitizers for clinical applications [40].

Licorice is one of the most commonly used medicinal herbs in TCM, which has various therapeutic effects such as anti-inflammatory [43], antitussive and expectorant [44], anti-diabetic [45] and immunomodulatory enhancement [46], etc. Besides, combining with certain drugs has the function of reducing drug toxicity and enhancing therapeutic effects [47]. Glycyrrhizic acid is a triterpene saponin extracted from licorice rhizomes and is one of the main activities of licorice, with antiviral [48], anti-inflammatory [49], anti-cancer [50] and hepatoprotective effects [51] (Fig. 4c).

GA contains both a hydrophobic region (one molecule of glycyrrhetinic acid) and a hydrophilic region (two molecules of glucuronic acid). When the concentration of GA reaches the critical micelle concentration, driven by non-covalent bonding forces (including van der Waals force, electrostatic force, hydrogen bonding force, solvent effect and hydrophobic effect, etc.), its hydrophobic chain segments form the inner core and hydrophilic chain segments form the outer shell, which can self-assemble in aqueous solution to form spherical micelles with core/shell structure [24]. Thanks to the amphiphilic structure, GA can be used as absorption enhancers and drug carriers. Studies have shown that the combination of GA as a carrier and other drugs can improve the bioavailability of drugs, enhance the therapeutic effect of drugs, and reduce the toxic side effects of drugs [52]. For example, it was used ultrasonic dispersion to load paclitaxel (PTX) into GA micelles so that it existed in the micelles in an amorphous state, thus improving the water solubility, intestinal permeability, oral bioavailability and other issues of PTX [24]. GA was used as a carrier for encapsulating onychotoxin to reduce the toxic side effects of onychotoxin [53]; Shen et al. self-assembled GA into micelles and encapsulated paeoniflorin to improve the oral bioavailability of paeoniflorin [54]. Therefore, GA could be as a promising drug carrier.

Poria acid A is a triterpenoid extracted from Poria cocos (Fig. 4d) [55]. Many studies have shown that poria acid A has good therapeutic effects on tumors [56], blood lipids [57], inflammation [58], kidney damage [59,60] and so on.

Previous studies have shown that PAA can self-assemble in ethanol-water mixed solvents to form natural self-assembled product gels [39,61]. This is due to the fact that triterpenoids have different numbers of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups, which are a class of natural self-assembling small molecule compounds with biological activity and self-assembled function [1]. The development of bioactive injectable gels can not only allow direct delivery to lesions but also enhances therapeutic or adjunctive effects through self-activated physiological activity, thereby achieving a multiplicative effect. The self-assembled injectable gels (PAA Gels) were successfully constructed using a simple mixing method that exploits the mechanism by which PAA, a triterpenoid compound, self-assembles into nanoparticles via hydrogen bonding and π-π interactions. The self-healing ability of PAA Gels was evaluated by rheometry and it was found that the removal of high shear rate. PAA Gels could return to the original gel state after several cycles. This confirms that PAA Gels possess excellent self-healing properties, making them suitable for constructing injectable gel drug delivery systems. Morphological observations via scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed that PAA Gels consist of nanofibers with diameters less than 100 nm, contributing to their good injectability. This structure is also dynamic and flexible, which facilitates the encapsulation of other active compounds such as doxorubicin (DOX). The combination index (CI) values of the combination of PAA Gels and DOX were less than 1, indicating a synergistic enhancement of the antitumor effect in the DOX-PAA Gels formulation. In the in vitro anti-tumor experiments showed that the DOX-PAA Gels group exhibited superior tumor suppression effect compared to the free DOX group, attributed to the sustained release properties of DOX-PAA Gels, which enable high local drug concentration at the tumor site. Additionally, the mice tolerated DOX-PAA Gels well, and the recovery of the mice in the DOX-PAA Gels group was better than that of the other treatment groups. Detection of blood routine, body weight and superoxide dismutase (SOD) levels indicated that DOX-PAA Gels also improved the overall health status of the mice [62].

This additional therapeutic effect demonstrates the great advantage of the bioactive gel.

Ursolic acid is a natural pentacyclic triterpene carboxylic acid found in many TCM and edible plants, including dogwood, self-healing herbs, cranberries and other fruits (Fig. 4e) [63]. In addition to its anti-inflammatory [64], antibacterial [65], anti-cancer [66], and anti-diabetic [67] effects, it also has significant antioxidant properties [68] and is thus used in a large number of pharmaceutical and cosmetic ingredients. And in recent years, it has attracted wide attention due to its advantages of non-toxicity to normal cells in cancer metastasis treatment [69]. However, the low tumor targeting specificity and poor bioavailability of UA have limited its clinical application [4].

To address this problem, Fan et al. [70] previously improved the properties of UA by structural modification and successfully synthesized a series of UA derivatives. However, the process of synthesizing UA derivatives was relatively complicated and most of these UA derivatives lacked water solubility. Subsequently, they developed a new strategy by exploiting the property that ursolic acid can self-assemble into carrier-free nanoparticles. While improving the bioavailability of UA, its water solubility and anticancer effect were also improved. Ursolic acid nano-particles (UA NPs) were formed by hydrophobic interactions between molecules and hydrogen bonding interactions. UA NPs were prepared by solvent exchange method and optimized for UA NPs, and it was finally found that UA dissolved with Ethanol (EtOH) could obtain better particle size of about 150 nm as subspherical nanoparticles. Solvent exchange method is a common operation including the evaporation, dialysis, extraction, diffusion, freeze-drying and others, used to set up subsequent reactions, extractions, or crystallizations, which can be better optimized in different solvents. There are scale-up challenges as follows: Firstly, the choice of solvent directly affects the efficiency of the reaction and the quality of the product. Therefore, we need to carefully evaluate the performance of various solvents and choose the most suitable solvent. In addition, phenomena such as phase separation and crystallization that may occur during solvent exchange also require our close attention. Also includes the reproducibility of solvent exchange methods. So solvent exchange is an important chemical operation that involves the transition from good solvents to poor quality solvents. By deeply understanding the principles, influencing factors, challenges, and opportunities of solvent exchange in practical applications, we can better utilize this technology to improve the efficiency of chemical reactions and the quality of products. Compared with free UA, UA NPs exhibited higher anti-proliferative activity on A549 cells in vitro, significantly induced apoptosis, decreased Cyclooxygenase-2/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor/Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor A (COX-2/VEGFR2/VEGFA) expression, increased immunostimulatory activity of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α(TNF-α), Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Interferon-β (IFN-β) cells, and decreased STAT-3 activity. In addition, UA NPs have tumor growth inhibitory and hepatoprotective effects in vivo. More importantly, UA NPs can significantly increase the activation of CD4-Positive T Lymphocytes (CD4+ T) cells, which suggests that UA NPs have immunotherapeutic potential.

Therefore, carrier-free UA NPs may be a promising drug to further enhance their anticancer efficacy and immune function [70].

Betulinic acid is a rigid monohydroxy 6-6-6-6-5 pentacyclic triterpenic acid with a length of 1.31 nm and hydroxyl and carboxyl groups separated by 0.97 nm (Fig. 4f) [71]. It can be extracted from TCM such as birch bark and sour jujube kernels [72]. It has been identified to have various activities such as anti-cancer [73], anti-AIDS [74] and anti-diabetic [75] activities. Exceptionally, BA is selectively cytotoxic to tumor cell lines but not to normal cells [76].

Bag and his colleague Dash first discovered that BA can self-assemble and have studied its self-assembly. They found that BA can self-assemble to form gels with fibrillar network structures in all 22 organic liquids and alcohol-water mixtures. Their single fiber diameters ranged from nanometers to micrometers and lengths of a few micrometers. In most cases, the self-assembled fibrous network structures of BA are so strong that they can impede the mobility of solvent molecules thereby producing soft solid-like materials. These results will contribute to the medical applications of BA and its use in drug delivery and nanoscience [71]. Dash et al. found that self-assembled nanogels with betulinic acid (SA-BA) induced macrophages to display a large amount of T-cell allogeneic stimulation ability and promoted the production of cytotoxic T lymphocytes. It indicated that SA-BA could be used as an effective immunostimulant for biomedical applications. In addition, the stimulatory effect of SA-BA on macrophages may be an effective tumor immunotherapeutic approach [77].

Among many combined anti-cancer strategies, PDT has gained widespread attention due to its unique advantages of non-invasiveness, high selectivity, and low toxicity [78,79]. Reduction of glutathione (GSH) is one of the effective methods to improve the efficacy of PDT, and disulfide bonding can scavenge glutathione and disrupt the redox balance of the tumor internal environment [80]. In addition, PSs play a crucial role in PDT treatment, with Ce6 being a commonly used PSs. In order to improve the therapeutic effect of PDT on tumors, Cheng et al. designed and synthesized a disulfide modified glutathione responsive BA with better biodegradability and biocompatibility based on this principle. Through π-π stacking, intermolecular hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic self-assembly, a carrier free photosensitive prodrug BA-S-S/Ce6 NPs with long or spherical morphology was constructed. Due to the overlap energy between BA-S-S and Ce6, which reduces the energy gap between singlet and triplet excited states, the assembled prodrug exhibits significant GSH response characteristics and multiple favorable therapeutic properties. Most importantly, it can produce synergistic enhancement of anti-tumor efficacy without obvious toxicity. In addition, they evaluated the antitumor efficacy of another tetracyclic triterpene stigmasterol mediated ST-S-S/Ce6 NPs, further confirming the effectiveness of this rational design [81].

This work provides a promising perspective for exploring the self-assembled behavior of pure drugs and constructing carrier-free triterpene precursor drugs for GSH response to improve multiple combination antitumor therapies with significantly enhanced synergistic antitumor efficacy, which could serve as potential clinically safe photochemotherapeutic agents.

Ginsenoside Ro is a kind of natural anionic biosurfactant extracted from TCM ginseng, has anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [82,83]. GRo belongs to disaccharide saponin, which has two sugar chains connected to a triterpene aglycone: D-glucose and D-glucuronic acid are connected to C-3, and the other D-glucose is connected to C-28 (Fig. 4g) [84]. This special triblock copolymer structure allows for self-assembly of GRo in aqueous solution. GRo can form micelles above Critical micelle concentration in aqueous solution [85].

The self-assembly characteristics of GRo was utilized to significantly improve the solubility of the active ingredient saikosaponin a (SSa) in Chaihu, solving the problem of low solubility of SSa in water [86]. In order to determine the mechanism of dissolution of SSa by GRo, the self-assembled behavior of GRo and the phase behavior of the mixed system of GRo and SSa were studied by mesoscopic dynamics and Dissipative Particle Dynamics. The simulation results indicated that GRo could form vesicles by closing the oblate membrane. At low concentrations, SSa molecules dissolve in the palisade layer of GRo vesicles. At high concentrations, SSa molecules interact with GRo molecules to form mixed vesicles, and GRo adsorbs on the surface of the vesicles. The evaluation of the dissolution process of SSa indicates that at low concentrations, GRo preferentially aggregates to form vesicles, which then absorb SSa into themselves. However, at high concentrations, SSa first undergoes self-aggregation and then dissolution. This is because the solubilization behavior of GRo makes the precipitation solubility equilibrium move to the dissolution direction.

These simulation results are consistent with the results of transmission electron microscopy and dynamic light scattering.

Pomolic acid is the main active ingredient of Licania pittieri, which is a natural pentacyclic triterpene acid compound, which has antiplatelet [87], anti-Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) [88] and anti-tumor [89] effects (Fig. 4h).

It is generally believed that, due to natural sources, natural gels (NGs) have better safety, biodegradability, biocompatibility and lower toxicity than synthetic gel. Recently, Hou et al. reported a novel thermosensitive supramolecular NGs (PA NGs) formed solely by solvent induced self-assembly of PA without any additives or chemical modifications. Due to PA being a typical 6-6-6-6-6-6 pentacyclic triterpenoid acid, it has a carboxyl group and two hydroxyl groups at both ends of the triterpenoid main chain, thus forming a relatively rigid planar structure. The presence of hydroxyl and carboxyl groups will facilitate the formation of intermolecular hydrogen bonds. By hydrogen bonding between different hydroxyl groups and π-σ between methyl groups and the ring skeleton π-σ Disperse interactions and assemble PA monomers to form one-dimensional structures; More hydrogen bond donors/acceptors and methyl lead PA molecules tend to tightly bind, forming a two-dimensional sheet-like structure. At this stage, the hydrogen bonding and π-σ dispersed interaction plays a dominant role as a critical noncovalent interaction force. Subsequently, the sheet-like structure further crosslinks with certain water molecules to form 3D layered sheet-like network. Shear stress shows that PA NGs has excellent stimulation response characteristics to temperature, which is helpful to use it as a promising injectable gel.

The preliminary in vitro anti-tumor test results showed that compared with PA monomer, the dry PA NGs had the same or even higher cytotoxicity to human breast cancer MCF-7 cells [90].

3.2 Self-Assembly of Single Active Small Molecule Drugs after Structural Modification

Curcumin (Cur)

Curcumin, a potent, non-toxic and major bioactive substance present in the Chinese herb turmeric, is a class of hydrophobic polyphenolic compounds that have been used to treat a variety of diseases such as cancer, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, inflammation, anxiety, depression, and ischemia-reperfusion (Fig. 4i) [91–96]. Cur has been found to interact with a variety of cancer cell signaling proteins [97,98], and to down-regulate multidrug resistance proteins (MDR) [99,100]. Numerous clinical trials have shown that Cur not only inhibits the proliferation of various cancer cell lines including liver cancer stem cells, prostate cells, colorectal cancer cells, breast cancer, and others [92,97–100], but also enhances the efficacy of radiotherapy and chemotherapy [101,102], and is highly cytotoxic to various cancer cell lines [97,98]. Notably, Cur does not cause systemic toxicity to human internal organs even at very high doses [103], which suggests that Cur has great potential in antitumor. However, because of its water insolubility and instability making, the bioavailability of curcumin is extremely low, and it usually has no anticancer activity in humans body, which would greatly limit the clinical application of Cur [104]. To overcome this limitation, various approaches have been developed to enhance the systemic absorption of CUR. These approaches include the use of adjuvants like piperine to interfere with glucuronidation, the use of liposomal CUR, CUR nanoparticles, CUR phospholipid complexes, and the use of derivatives and structural analogues of CUR [105]. They can overcome the challenges in translating in vitro success to in vivo or clinical outcomes.

To address the bioavailability of Cur, Tang designed an amphiphilic surfactant-like curcumin prodrug (Cur-Pro) with intracellular instability for use as an anticancer prodrug. By using the strong hydrophobicity of Cur-molecules, Tang [106] combined the β-thioester bond of Cur with two short hydrophilic ethylene glycol oligomeric chains to form an amphiphilic Cur surfactant molecule, and successfully dissolved the water-insoluble Cur micelle (nanoparticles) in the form of core-shell in water. The core of the micelles consisted of a hydrophobic cur fraction with a high and fixed cur loading (25.3 wt%). The high loading of Cur enhances the tumor permeability and retention effect thus passively accumulating Cur to target tumors. Once entering the intracellular environment, the nanoparticles release Cur active substances, exhibiting very high bioavailability, enhanced in vitro cytotoxicity and significant in vivo anticancer activity. Amphiphilic curcumin-like surfactant molecules in the form of core-shell micelles can also act as drug carriers, and Cur-Pro nanoparticles can carry other anticancer drugs such as DOX and camptothecin (CPT) to synergize their anticancer efficacy [106].

The system compares to other curcumin delivery systems already reported (e.g., liposomes, solid lipid nanoparticles, or PEGylated systems) as follows: liposomes possess good lubricant capacity and pharmacological synergy with curcumin [107]. A novel cationic solid lipid nanoparticles with targeting ability were constructed, which can enhance the stability of curcumin [108]. The design of the experiment study, employed to simultaneously assess the impact of the oil phase, different PEGylated phospholipids and their concentrations, as well as the presence of curcumin, showed that not only the investigated factors alone, but also their interactions, had a significant influence on the critical quality attributes of the PEGylated nanoemulsions [109]. The utilization of nanocarriers for curcumin delivery is still in the initial phases, with regulatory approval pending and persistent safety concerns surrounding their use [110].

3.3 Application of Self-Assembly of Two Active Small Molecule Drugs

3.3.1 Self-Assembly of Berberine (Ber) with Other Drugs

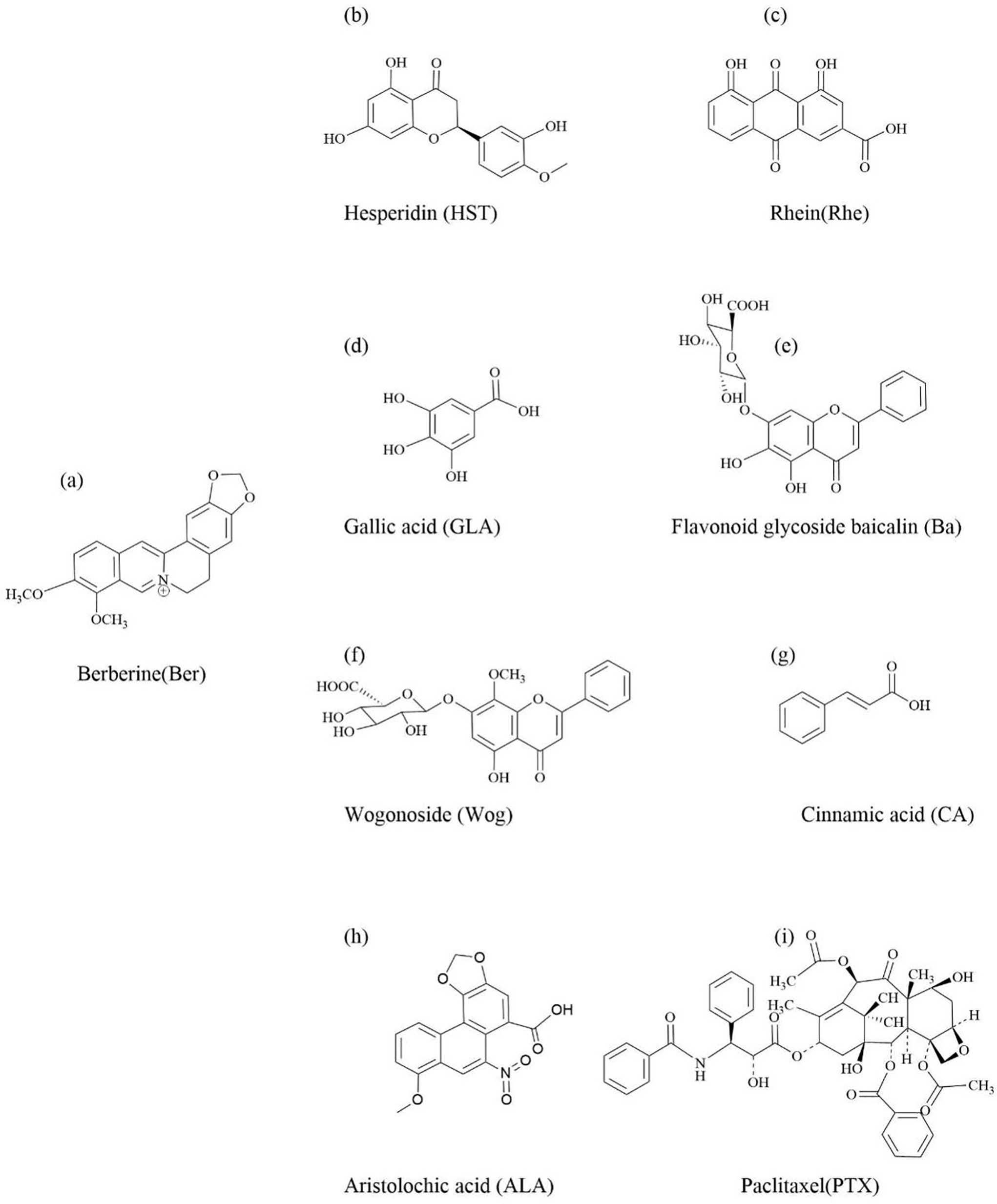

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease characterized by bloody diarrhea. The disease recurs and is difficult to cure, and long-term colitis is an important high-risk factor for inducing colon cancer [111]. However, current treatment methods cannot meet the clinical needs of patients with ulcerative colitis. In TCM clinical practice, Huanglian is one of the most commonly used drugs for treating UC, which has the effects of clearing heat and drying dampness, promoting “qi” and relieving pain, and stopping dysentery and diarrhea [112]. Berberine (Ber) is an isoquinoline alkaloid active substance extracted from Huanglian, often used to treat intestinal inflammatory diseases (Fig. 6a) [113]. It is widely used due to its broad-spectrum antibacterial [114] and anti-inflammatory [115] effects, as well as Ber’s low toxicity and good tolerance [116] during the treatment process. However, the low bioavailability of Ber has limited its wide application in clinical practice [117,118]. Therefore, the construction of a drug delivery system with stable and high efficiency may be beneficial to improve the bioavailability of the drug. Hesperidin (HST) is a flavonoid substance widely present in citrus fruits, with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects (Fig. 6b) [119,120]. Gao et al. [121] formed a carrier free multifunctional spherical nanoparticle (NP) by self-assembly of two natural plant chemicals, berberine (ber) and hesperetin (HST), through electrostatic interactions, π-π stacking, and non-covalent hydrogen bonding. Ber-HST NPs have significantly better inhibitory and therapeutic effects on UC inflammation than Ber or HST by regulating the immune microenvironment and repairing damaged intestinal barriers, as well as synergistic anti-inflammatory activity. In addition, Ber-HST NPs have good biocompatibility and biosafety.

Figure 6: The chemical structure of natural active ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine that can self-assemble with berberine

Therefore, Ber-HST NPs have the potential to treat UC.

A major threat to human health in microbial infections is bacterial biofilm formation, which accounts for more than 65% of human microbial infections [122], and methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) is the most typical biofilm-forming bacterium in clinical practice [123]. A programmed strategy encompassing inhibition of microbial community formation, disruption of mature biofilms, and hindering reattachment of dispersed bacteria has been developed as a promising approach to address biofilm-associated infections. In addition, experimental studies have shown that Ber is sensitive to MRSA and has a low tendency towards drug resistance [124,125].

The decoctions are one of the most commonly used forms of TCM in clinical treatment. Many decoctions can produce self-assembled NPs during the decoction process [20,126], and this self-assembled strategy involves a simple preparation process and enhanced performance. This widely used, universal, and biocompatible self-assembled method provides a new perspective for understanding TCM chemicals and may contribute to the development of new effective nanomedicines inspired by TCM.

In TCM theory, there are often drug combinations, such as famous drugs such as rhubarb-Huanglian and Scutellaria baicalensis-Huanglian, which are often used in combination to enhance drug efficacy. Rhein (Rhe) is the main NAI-TCM rhubarb, due to its unique anthracene skeleton and self-assembled characteristics (Fig. 6c). At the same time, rhein also has antibacterial activity [127], and binding with Ber may have synergistic antibacterial effects. Inspired by drug binding, Tian et al. successfully obtained self-assembled nanoparticles of berberine and rhein (Ber-Rhe NPs). The self-assembled mechanism of Ber-Rhe NPs was demonstrated by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and X-ray diffraction: that is, the basic units were formed using Ber and Rhe through π-π stacking between isoquinoline and anthracene rings and electrostatic interactions; subsequently, the basic units were derived from hydrogen bonds between Rhe molecules, and the laminar skeletal materials were further constructed in the aqueous phase; finally, the spherical three-dimensional nanoparticles with Rhe as the basic skeleton and Ber embedded in the lamellar gaps were formed. The inhibition experiments in vitro showed that the minimum bactericidal concentration of Ber-Rhe NPs was 0.1 µmol/mL, which was lower than that of Ber or Rhe. A series of experiments were also conducted to evaluate the antibacterial activity of NPs. For example, confocal laser scanning microscopy, quantitative biofilm analysis and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results showed that Ber-Rhe NPs had a strong inhibitory effect on MRSA biofilm. More importantly, due to the partial distribution of Rhe on the nanoparticles, the hydrogen bonding between Rhe molecules increased the affinity of the nanoparticles to the bacterial surface, allowing Ber-Rhe NPs to adhere to the bacterial surface and increase the concentration of individuals around MRSA, and the release of Ber and Rhe would further lyse the membrane, thus causing severe damage to the bacterial integrity and leading to its death. In addition, the biocompatibility of Ber-Rhe NPs was evaluated by hemolysis test, cytotoxicity test and zebrafish, and Ber-Rhe NPs were found to have good biocompatibility and safety. Therefore, Ber-Rhe NPs have a greater potential for antibacterial clinical application [128].

Ber-Rhe NPs not only have synergistic antibacterial effects, but also have synergistic anti Alzheimer’s disease (AD) effects. Recently, Shen et al. found that Ber-Rhe NPs exhibited superior or close to single component inhibition of cholinesterase, regulation of Aβ aggregation, ROS elimination, and metal ion chelation in vitro synergistic anti-AD effects [129]. This provides inspiration for the development of new multi target drugs against Alzheimer’s disease. The cytotoxicity test showed that the assembly had almost no neurotoxicity. The evaluation of ROS levels in vivo indicates that this assembly can reduce the accumulation of ROS in the cells of Caenorhabditis elegans. Moreover, due to the superior 3D porous framework of Ber-Rhe NPs, they can also serve as novel potential carriers for drug delivery.

Gallic acid (GLA) is a natural phenolic acid found in the medicinal and edible plant Cornus officinalis (Fig. 6d) [130], which has biological activities such as antioxidant [131], anti-inflammatory [132], and promoting wound healing caused by bacterial infections [133]. So, the therapeutic hydrogel formed by rapid self-assembly of GLA triggered by Res can be used for the healing of bacterial infected wounds. Not all compounds of the same class with the same nuclear structure can undergo self-assembly. Recently, Lu et al. found that only GLA can self-assemble with Ber through electrostatic interaction, π-π stacking, and hydrophobic interaction during the self-assembled process of gallic acid analogues (including 3-hydroxybenzoic acid, 4-hydroxybenzoic acid, 3,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid, pyrogallol, and GLA), forming nanoparticles [134]. Moreover, due to the unique ortho phenolic hydroxyl structure of GLA, the resulting GLA-Ber NPs have a vertically stacked structure. In terms of antibacterial activity, GLA-Ber NPs can block bacterial translation mechanisms and lead to bacterial death by downregulating the mRNA expression of differentially expressed genes (including rpsF, rplC, rplN, rplX, rpsC, rpmC, and rpsH) both in vitro and in vivo. Therefore, GLA-Ber NPs exhibits strong antibacterial activity and biofilm removal ability, and has good anti-inflammatory activity. And GLA-Ber NPs can enhance the expression of pro angiogenic factors (FGF-2 and FGFR3) and inhibit the expression of anti-angiogenic factors (Timp1 and Timp2), thereby promoting angiogenesis and ultimately accelerating wound healing caused by MRSA infection. In addition, nanoparticles exhibit good biocompatibility without cytotoxicity, hemolytic activity, and tissue or organ toxicity. Therefore, GLA-Ber NPs derived from this drug combination have potential clinical translational value in wound recovery caused by MRSA infection.

Flavonoid glycoside baicalin (Ba) and wogonoside (Wog) are the main active components of scutellaria baicalensis (Fig. 6e,f) [135]. Li et al. [31] found that in aqueous solutions, the carbonyl groups of glucuronic acid on these two types of flavonoid glycosides can self-assemble with the quaternary ammonium ions of Ber through electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions to form nanoparticles. However, these two component self-assemble with similar molecular frameworks can form different nanoscale forms. Due to the close proximity of the hydrophobic flavonoid nuclei of Ba and Ber, they can self-assemble into spherical nanoparticles with hydrophilic parts outward (Ba-Ber NPs). The glucuronic acid portion of Wog is far away from the flavonoid mother nucleus, making it more likely for the Wog-Ber complex unit to form a hydrophobic mother nucleus at both ends and a hydrophilic sugar ring in the middle of the I-shaped plane hydrophobic molecule. Moreover, due to the lack of affinity, these units cannot self-assemble into NPs, but only precipitate NFs in water driven by strong hydrophobicity. Interestingly, although these self-assembled core antibacterial components are Ber, the antibacterial experimental results show that different molecular configurations will ultimately provide different morphologies and antibacterial effects. Compared with Ber, the antibacterial activity of Ba-Ber NPs is significantly enhanced, while the antibacterial activity of Wog-Ber NFs is significantly weaker. This may be due to the hydrophilic surface of Ba-Ber NPs, which makes them easier to adhere to bacteria. The difference of activity between Ba-Ber NPs and Wog-Ber NFs prompted us to discover that different self-assembled forms lead to different biological activities.

Inspired by the combination of clinical drugs, Huang et al. found that the carbonyl group of cinnamic acid (CA) (Fig. 6g), the main component in traditional spice cinnamon, can form hydrogen bonds with the nitrogen atoms of Ber, while the aromatic rings of both molecules form π-π stacking structures, which are induced by these non-covalent interactions to form butterfly-like one-dimensional self-assembled units and eventually layered three-dimensional spatially structured nanoparticles (CA-Ber NPs). In contrast to several first-line antibiotics, CA-Ber NPs can spontaneously adhere to bacteria, penetrate into them, and can synergistically converge to attack MRSA. Subsequently, bioinformatics studies have shown that interference of CA-Ber NPs affected many aspects of the bacterial microenvironment and limits bacterial growth. It is the multipathway bactericidal mechanism of CA-Ber NPs against MRSA that results in better inhibition of MRSA and better removal of biofilm. Also, the obtained CA-Ber NPs have sustained release ability and good biocompatibility [136].

In addition to possessing antibacterial activity, Ber can also be used in combination with TCM containing aristolochic acid (ALA) (Fig. 6h) to reduce the toxicity of ALA. Numerous studies have shown that the combination of traditional Chinese medicine containing ALA and Huanglian can greatly reduce toxicity and achieve clinical safety. Wang et al. found that Ber and ALA self-assemble into linear multiphase supramolecules (A-B) with hydrophobic groups on the outside and hydrophilic groups on the inside through electrostatic attraction and π-π stacking [137]. The supramolecular structure forms visible fibrous precipitates and has good stability. Meanwhile, the self-assembly induced by these weak bonds can block the cyclization of the toxic group nitro and hydroxyl groups of ALA, forming toxic metabolites such as Aristolochia lactam and DNA adducts. The comprehensive evaluation of mice showed that the toxicity of the A-B treatment group was significantly reduced compared to the ALA treatment group. A systematic biological analysis of the treated mouse kidney tissue revealed that compared to the blank group, ALA treatment resulted in over 1000 genes being upregulated or downregulated, leading to toxic effects or being associated with immune cell infiltration. However, after the complexation of ALA with Ber in the form of supramolecules (A-B), most of the toxic effects were counteracted. And it was found that the A-B treatment group could prevent ALA induced renal inflammatory response in mice by alleviating the release of pro-inflammatory mediators. In addition, the biocompatibility of A-B had good biocompatibility and safety via zebrafish evaluated.

Taxus chinensis belongs to taxaceae, which mainly treats nephritis and diabetes [138]. PTX is a broad-spectrum anti-cancer compound extracted from Taxus chinensis, which acts on microtubules (Fig. 6i) [139]. It belongs to a diterpene alkaloid. It can specifically combine with tubulin subunits to prevent mitosis of cells and cause programmed cell death [140]. It shows significant activity in the treatment of breast cancer [141], lung cancer [142], ovarian cancer [143], bladder cancer [144], head and neck cancer [145]. However, due to the poor water solubility, low intestinal permeability, low oral bioavailability [5], and the MDR of PTX [146], its clinical treatment effect is very limited.

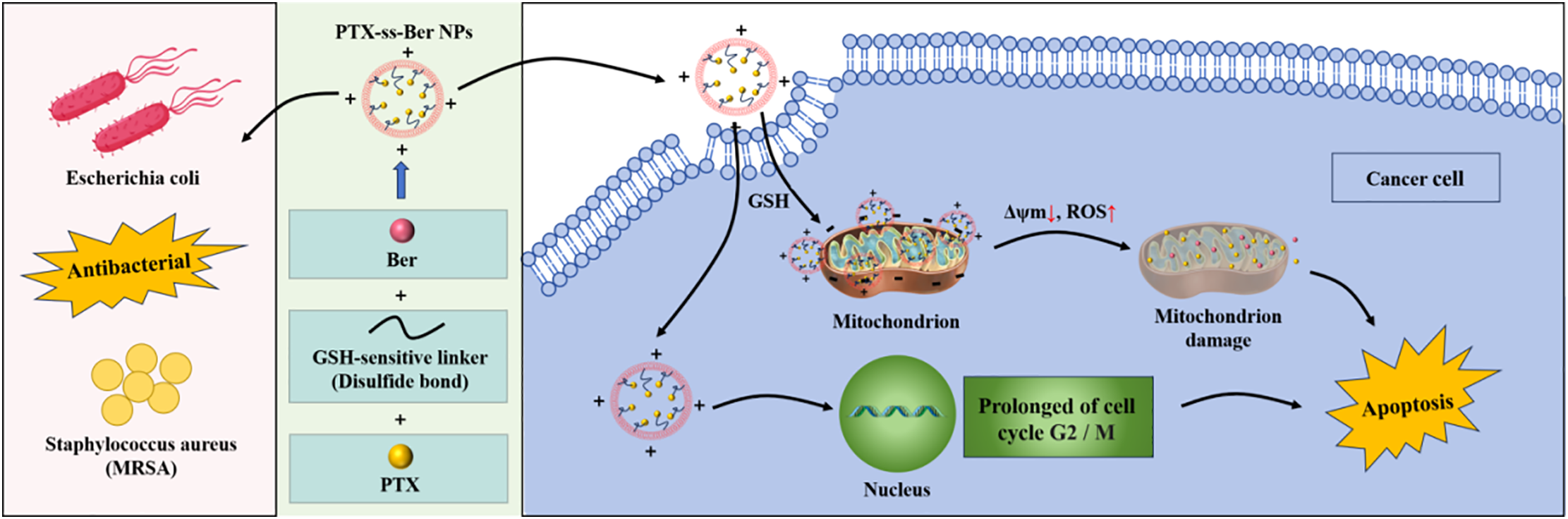

A major reason for the formation of MDR is due to the fact that therapeutic drugs are pumped out of cancer cells by an energy-dependent efflux pump, which leads to low accumulation of the drug in the cells as well as therapeutic failure [147]. Cellular energy production is mainly derived from aerobic metabolism in mitochondria and plays a key role in configuring the apoptotic pathway in cancer cells [148]. It has also been reported that PTX has a direct effect on the mitochondria of cancer cells, which ultimately leads to apoptosis [149]. Therefore, in oncological chemotherapy, the introduction of therapeutic agents from cancer cells into mitochondria is a promising solution strategy to reduce MDR to achieve effective cancer therapy. Ber has antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and antiviral effects in addition to antitumor pharmacological effects, and it selectively accumulates in the mitochondria of tumor cells, thereby inhibiting cancer cell growth [150]. GSH, a strong bioreductive tripeptide, is a commonly used disulfide bond stimulating factor at certain concentrations [151]. Compared with normal tissues, the expression level of GSH in mitochondria of cancer cells is high (between 2~10 μmol-L-1), which is sufficient to reduce disulfide bonds [152]. Therefore, the construction of a GSH-sensitive drug delivery platform targeting mitochondria is expected to enhance chemotherapeutic effects. Cheng et al. constructed paclitaxel-ss-berberine coupling (PTX-ss-Ber) targeting mitochondria of tumor cells by linking Ber and PTX with disulfide bonds (Fig. 7) [153]. In the results of molecular dynamics simulations, it was shown that PTX-ss-Ber couples could self-assemble into spherical nanoparticles (PTX-ss-Ber NPs) under π-π stacking and hydrophobic interaction, and the average particle size of NPs was measured at DLS to be about 165 nm. The increased in vitro potency of PTX-ss-Ber NPs against human lung cancer cells (A549 cells) might be related to the drug release and this would release the mitochondrial membrane potential, upregulate the ROS level in cancer cells, arrest the cells in G2/M phase, and ultimately induce apoptosis and inhibit tumor growth. In addition, PTX-ss-Ber NPs were superior or comparable to Ber in terms of efficacy against MRSA and Escherichia coli, which are closely associated with lung cancer development. The synergistic effects of PTX and Ber enhanced the therapeutic efficacy of conventional chemotherapeutic agents against A549 cells.

Figure 7: Schematic diagram of constructing nanoparticles (PTX-ss-Ber NPs) targeting tumor cell mitochondria. PTX-ss-Ber NPs accumulate in the mitochondria of human lung cancer cells (A549 cells) through the positive ion properties of Ber, and disulfide bonds are sensitive to the tumor microenvironment to control drug release. By releasing mitochondrial membrane potential and upregulating ROS levels, anti-tumor effects are ultimately achieved. Meanwhile, PTX-ss-Ber NPs has a therapeutic effect comparable to Ber on bacteria closely associated with cancer development

Therefore, PTX-ss-Ber NPs solve the solubility of PTX, significantly improve its bioavailability, produce coordinated anti-tumor effects, and have therapeutic effects on MRSA.

3.3.2 Self-Assembly of Terpenoids with Other Drugs

Terpene polycyclic compounds have multiple charge centers and unique chiral structures. In recent years, a series of terpenoid polycyclic compounds have been reported to have the ability to self-assembly [1,24,70,71]. The Bag research group has confirmed that all triterpenoid compounds are functional assemblies, as their structures contain carboxyl groups, hydroxyl groups, carbon carbon double bonds, alkyl side chains, and rigid frameworks, which enable them to form ordered nano self-assembled structures driven by weak forces such as hydrogen bonding, π-π interactions, and van der Waals forces [1]. They also found that the self-assembled structures of single terpenoid compounds exhibited similar molecular self-assembled characteristics [1,21,154], that is, the ordered coplanar arrangement of these molecules is conducive to driving the formation of long rod-shaped, layered, and fibrous nano morphologies; The presence of vertically cross arranged molecular structures will reduce the tendency of coplanar arranged molecules to continue lateral growth, promoting the formation of spherical and short rod-shaped NPs.

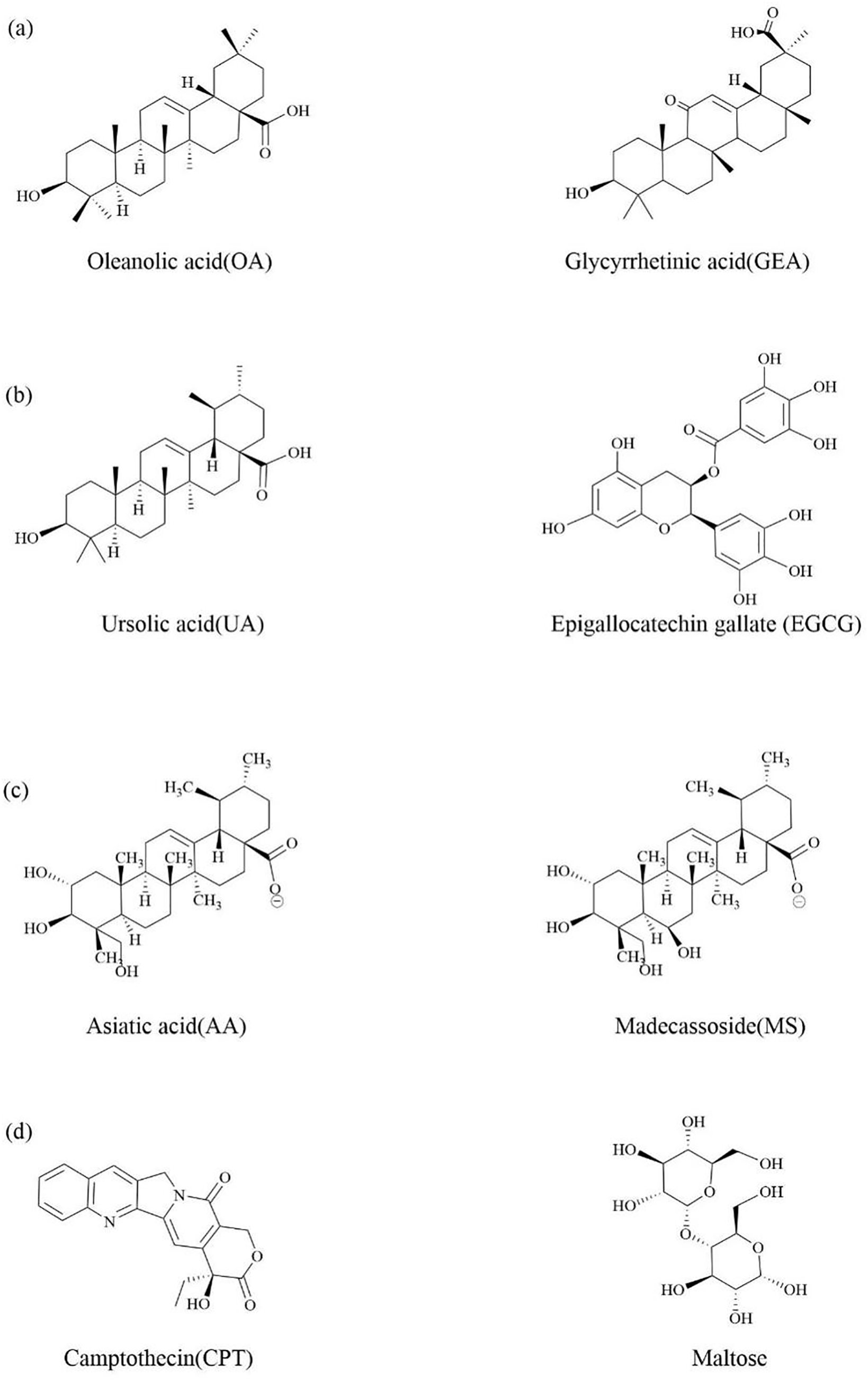

Oleanolic acid (OA) is a pentacyclic triterpenoid compound isolated and extracted from the fruit of Ligustrum lucidum [155], which has anti-inflammatory [156], anti-hyperlipidemic [157], and anti-cancer effects [158]. Bag found that OA can self-assemble in chlorobenzene to form a nanoscale bilayer soft vesicle structure, which has good drug loading performance [159]. Glycyrrhetinic acid (GEA) is also a pentacyclic triterpenoid, derived from the dual-purpose plant licorice (Fig. 8a), which has antiviral [160], anti-inflammatory [161], anti-cancer [162], and hepatoprotective [163] effects. A spherical nanoparticle (OA-GEA NPS) was prepared using the self-assembled mechanism of hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions between OA and GEA, which also indicates that the self-assembled structure of the two terpenoid compounds also conforms to the self-assembled characteristics of terpenoid compounds discovered. OA-GEA NPS not only exhibits excellent stability, high drug loading, and sustained release properties, but also the co-assembled nanoparticles formed by two small molecule compounds have synergistic anti-tumor effects. Main and common mathematical models of drug release contain Zero-order, First-order, Higuchi, Korsmeyer-Peppas, Weibull, Hixon-Crowell. In addition, there are more mathematical models used to describe the kinetics of drug release include Peppas–Sahlin, Hopfenberg, Baker–Lonsdale model, and others. After drug loading, the anti-tumor effect is further improved. In addition, the self-assembly of this natural drug could highlight the unique advantages of active natural products in terms of biosafety and health benefits. Compared with free drugs, it can reduce liver damage caused by chemotherapy drugs by upregulating key antioxidant pathways. Compared with non-pharmacological active drug delivery systems, it solves the disadvantage that pharmacological active compounds cannot be directly applied, and can also be used as drug delivery carriers [164]. In addition, they used UA and PTX to form an outer bilayer vesicle structure through hydrogen bonding between the hydroxyl and hydroxyl groups of UA, and exposed the carboxyl groups to a hydrophobic environment to create an internal hydrophobic region, providing a location for the assembly of UA-PTX. The interaction between PTX and ursolic acid occurs within the nanoparticles, dominated by hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions. Both ursolic acid and paclitaxel contain multiple hydrogen bond donors and acceptors, and hydrophobic interactions mainly self-assemble by the two methyl groups of ursolic acid approaching the two benzene rings and amide bonds of paclitaxel. It not only solves the problems of poor water solubility, low intestinal permeability, and low oral bioavailability of paclitaxel, but also has a synergistic anti-tumor effect [165].

Figure 8: The discussion of the chemical structure of terpenes and their natural active ingredients in traditional Chinese medicine that can undergo self-assembly

Primary liver cancer is one of the most difficult malignant diseases to treat in the world, the second largest cancer death case in the world, and can generate a large number of new cases every year [166]. Green tea is a medicinal and edible plant, and epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG) is an active ingredient in green tea (Fig. 8b). In addition to its well-known antioxidant properties [167], it also has anti-cancer effects [168]. UA also has anti-cancer effects [66]. It was found that EGCG can self-assemble with UA [169]. EGCG can self-polymerize to form a uniform layer at alkaline pH, forming coatings on various organic and inorganic matrices as a “shell” to avoid degradation of the “core”. UA has a unique self-assembled phenomenon and can be used as a nanoscale drug preparation. UA and EGCG are assembled through intermolecular hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, and the EGCG coating forms a “core-shell” nanostructure (EGCG-UA NPs) on the surface of UA NPs, enhancing their stability and targeting ability by binding to ligands. Epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM) positive cells have been shown to be responsible for the growth and invasion of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). By modifying the the EpCAM nucleic acid aptamer (EpCAM-Apt) on the outer shell of EGCG, the targeting effect of EGCG-UA NPs on EpCAM positive cells can be significantly enhanced. Therefore, UA in the EGCG-UA NPs nanosystem can not only cause tumor cell death and provide tumor antigens, but also bind with EGCG to activate natural immunity and enhance APC cell proliferation, thereby achieving further clearance of tumors by acquired immune cells. Compared with traditional nanocarriers, preparing self-assembled NPs is more likely to reduce side effects such as low drug loading and potential toxicity.

Centella asiatica has functions such as antioxidant, antibacterial, and immune regulation. It contains four pentacyclic triterpenoid components: asiatic acid (AA), madecasic acid (MA), asiaticoside, and madecassoside (Fig. 8c) [170]. The extract of CA, rich in triterpenoid glycosides, can inhibit the expression of key factors in the inflammatory response pathway, thus having good anti-inflammatory and wound healing promoting effects [171]. Computer simulations was used to investigate the self-assembled behavior of AA and MA in aqueous solutions and found that the shape of AA and MA self-assembled nanoparticles changed from spherical to “flattened cylindrical” [172].

It is indicated that AA and MA molecules within self-assembled micelles are preferentially taken not parallel or perpendicular to each other.

3.3.3 Self-Assembled Model of Other Drugs

To reduce the adverse reactions caused by chemotherapy in cancer treatment, address the issue of traditional nanocarriers accumulating during degradation and metabolism, and ultimately achieve efficient drug delivery. Researchers have developed a new amphiphilic nano supermolecule anti-tumor prodrug (ASMP) by directly combining anti-cancer drugs with small molecular compounds and completing self-assembly through directional and reversible non covalent interactions between molecules [173]. ASMP enhances drugsolubility and stability while achievinghigher drug loading [174].

The hydrophobic active ingredient CPT was conjugated to a hydrophilic sugar ligand through disulfide bond and self-assemble into a spherical amphiphilic nano supermolecule prodrug (NSp) responsive to GSH. This construct, named camptothecin glycosylated nano supermolecule prodrug (CPT-GL NSp), was formed through intermolecular directional and reversible non-covalent interactions. The study demonstrated that CPT-GL NSp could significantly improve the solubility and stability of hydrophobic active ingredient CPT, and solve the problem of its low bioavailability. Furthermore, CPT-GL NSp exhibited higher drug loading capacity compared to traditional nanoparticles. Based on the high expression of glucose transporter 1 on tumor cell membranes, glucose, maltose, and maltotriose were selected as the hydrophilic part of Amphiphile (Fig. 8d). Among the three sugar ligand-modified NSPs, the maltose-modified NSp showed the strongest antitumor effect compared to glucose- and maltotriose-modified NSPs.

More importantly, CPT-SS-Maltose demonstrates anti-tumor capabilities comparable to those of irinotecan, while exhibiting superior solubility, reduced hemolysis, and enhanced uptake by HepG2 cells [175].

3.4 Application of Self-Assembly of Various Active Small Molecule Drugs

In 2020, OA, GEA and PTX was used to produce nanoparticles called OA/GEA/PTX NPs. Interestingly, OA/GEA/PTX NPs are solid spherical structures without shells and have a single structure. They aggregated OA and GEA molecules to form hydrophobic cavities, and the side chains formed by OA and GEA can interact with the benzene ring of PTX to form hydrophobic interactions to load hydrophobic drug PTX. In addition, due to the presence of hydrogen bonding donors and acceptors in OA, GEA, and PTX molecules, there is also a significant hydrogen bonding interaction between PTX and OA and GEA. This leads to smaller NPs in the nano drugs synthesized by OA, GEA and PTX compared to OA/GEA, and higher drug loading of PTX. Through single factor experiments to optimize the formulation and preparation process, it was found that when the feed ratio of OA and GEA was 5:2 (w/w), the maximum loading amount of loaded PTX reached 15%, the encapsulation efficiency was 99%, and there was no risk of thromboembolism. It also had good dispersibility and chemical stability, and strong hydrophilicity. This will improve the bioavailability of PTX and solve the problems of poor water solubility, low intestinal permeability, and low oral bioavailability of PTX. In addition, it also has stable sustained-release function, which is the key to enhancing drug accumulation in tumors and achieving intracellular drug release. In vivo drug distribution experiments showed that compared with the control group, fluorescence labeled OA/GEA/PTX NPs exhibited rapid tumor aggregation targeting and time-dependent tumor accumulation, and were able to maintain strong fluorescence signals for a longer period of time, confirming the high accumulation and retention of NPs in tumors. In vitro and in vivo anti-tumor activity studies have also shown that after 48 h of exposure, OA/GEA/PTX NPs have a high inhibition rate of 82.6% on tumor cells, and their cytotoxicity is stronger than that of free PTX and OA/GEA NPs, and neither showed the delayed cytotoxicity. Staining 4T1 cells with propidium iodide was used to reveal the mechanism of synergistic effect between OA and GA. The results showed that OA caused cell cycle arrest in G2/M phase, while GEA blocked cell cycle in G0/G1 phase. Therefore, OA/GEA/PTX NPs exhibited strong cell proliferation inhibition and significantly enhanced anti-tumor effects through different mechanisms. In addition, the half-life of OA/GEA/PTX NPS is four times that of PTX injection. At the same time, OA/GEA/PTX NPs could also increase the levels of SOD and GSH in mouse liver tissue, reduce tissue damage, and have good liver protection and anti-inflammatory activity.

Therefore, the combined administration of OA and GEA loaded PTX could not only effectively alleviate liver damage caused by PTX, but also improve anti-tumor activity [164].

4 Applications of Self-Assembly of Macromolecular Drugs

Natural Chinese medicine contains abundant proteins, which are highly safe and have low toxic side effects. Therefore, the particles formed by proteins are an important research direction. Previous studies have shown that the safety and reliability of nanoparticles formed by proteins in plants as drug carriers have been recognized. Therefore, choosing proteins as research objects for self-assembly is highly feasible.

The essence of protein accumulation and aggregation is the phenomenon of molecular self-assembly. Molecular self-assembly is the formation of molecular aggregates with a specific arrangement order through noncovalent means, utilizing the recognition interaction between molecules and one segment and another. The interaction force of non-covalent bonds is the key to molecular self-assembly. The occurrence of self-assembled behavior requires two conditions: first, assemble force, which refers to the synergistic effect of non-covalent bonds between molecules; The second is the guiding effect, which refers to the complementarity in molecular space, that is, the accumulation of molecules in space. Like many Chinese herbal medicines, licorice contains high levels of soluble protein. After some of the soluble proteins are saccharified, they can also maintain their solubility properties in boiling soup, and Licorice protein (LP) is one of them. Ke et al. found that LP can self-assemble into nearly spherical nanoparticles (206.2 ± 2.0 nm) at pH = 5.0 and 25°C [47]. Aconitine (AC) is a highly toxic diester alkaloid extracted from aconitum and other TCM, and is also its main bioactive component [3]. Infamous for its high cardiotoxicity and neurotoxicity, it is known as the “devil’s helmet”. In the compatibility of TCM, people often use licorice in combination with aconite. For example, the classic TCM formula “Sini Tang” in “Treatise on Cold Damage” consists of three TCM: licorice, ginger, and aconite. It was studied and found that glycyrrhizin, the active ingredient in liquorice, can form a complex between the active ingredient AC of aconitum, which will greatly reduce the concentration of free AC in TCM decoction, eliminate the toxicity of AC, and improve the efficacy [176]. This also indicates that the interaction between aconitine and other major amphiphilic compounds (i.e., proteins) in liquorice may also promote the formation of such AC complexes. Therefore, the same method was used to prepare AC coated LP near spherical nanoparticles (238.2 ± 1.2 nm), and carried out intraperitoneal injection toxicity test on ICR mice (n = 8), respectively injecting LP-AC nanoparticles and licorice aconite mixture decoction, the toxic reaction showed mild, no death [47].

Milk is one of the oldest natural dairy products, and in TCM, it has the effects of calming and calming the mind, clearing heat and detoxifying. Milk is rich in protein, which is highly safe and has low toxic side effects. Caseins (Cass) is the main component of milk. It is a natural diblock copolymer with obvious amphiphilic structure. It can self-assemble in water to form a nano scale core-shell nanocomposite, in which hydrophobic blocks aggregate into cores and hydrophilic blocks form nanocomposite shells [177]. Drugs can be incorporated into the core of nanocomposites formed by Cass molecules through physical embedding, electrostatic interaction and Covalent bond. For example, Pan et al. encapsulated Cur in Cass to improve the anti-cancer activity of Cur, and found that Cur encapsulated in Cass nanoparticles has higher dispersion, biological activity, and better stability [178]. Liu et al. successfully prepared Cass nanoparticles loaded with triptolide (TP) by using the self-assembled characteristics of Cass in water, and found that this could enhance the absorption of TP and improve the oral bioavailability of TP [179]. Therefore, Cass has the potential as an excellent carrier for drug delivery.

In addition to natural polymer compounds that can undergo self-assembly, modifying the structure of small molecule drugs to become amphiphilic drugs to induce self-assembly is also a self-assembled strategy. Celastrol (CEL) is a triterpenoid extracted from the tripterygium wilfordii, which has been reported to have anti-cancer activity. However, poor water solubility and high lateral toxicity severely limit the clinical application of CEL. Li et al. chemically coupled CEL onto the methoxyl poly (ethylene glycol)-b-poly (L-lysine) (mPEG-PLL) framework and transformed the biphilic mPEG-PLL polymer into the amphiphilic polymer prodrug mPEG-PLL/CEL. Due to the hydrophobic binding of the CEL portion in the side chain and the possible electrostatic interaction between the carboxyl group in CEL and the residual amino group in the PLL chain segment, the obtained mPEG-PLL/CEL can self-assemble into stable spherical core/shell micelles nanoparticles (CEL-NPs) in aqueous solution. Then, it was characterized by dynamic light scattering and transmission electron microscopy. In addition, the anti-tumor effects of CEL NPs were studied through MTT assay and B16F10 tumor bearing mouse model. The results showed that CEL-NPs exhibited sustained drug release behavior and were effectively internalized by B16F10 cells. In addition, the anti-tumor evaluations in vivo have shown that CEL NPs have significantly higher tumor growth inhibition rates and lower systemic side effects compared to free CEL [180]. In addition, Gao et al. designed and synthesized a precursor by covalently linking paclitaxel with an easily self-assembled motif and a group that could be cleaved by enzymes. The self-assembled behavior took place in water using enzymatic reaction to form nanofibers, thus forming supramolecular hydrogels [181]. The hydrogel can be used as both a delivery carrier and the drug itself.

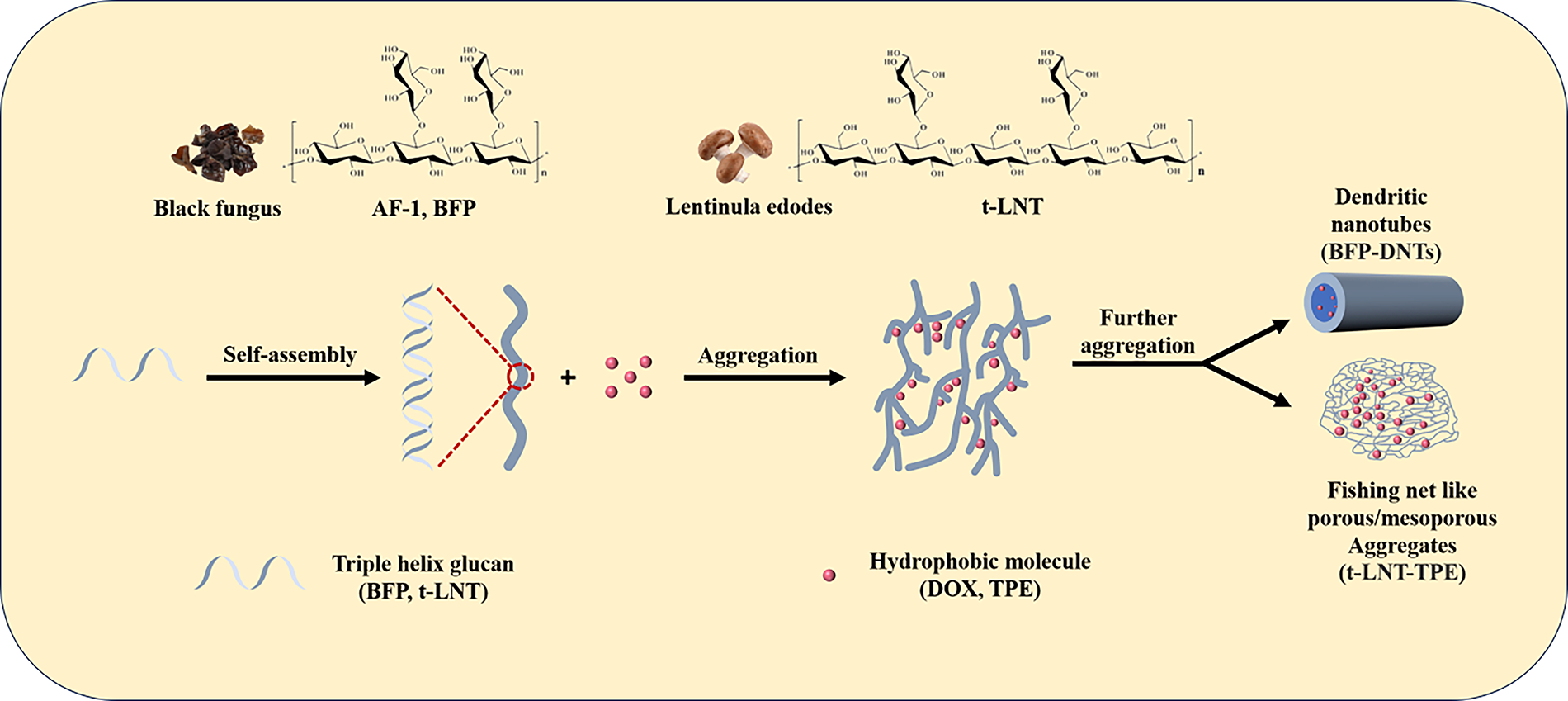

Due to the relative hydrophobicity of glucose on the C2-OH side of the main chain of triple helix glucan, glucose on the C6-OH side is relatively hydrophilic [182]. Therefore, triple helix glucan has both hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity, and can aggregate and self-assemble to form ordered structures [183]. Black fungus is a common large edible and medicinal fungus that contains various polysaccharides [184]. Research has shown that it has various physiological activities such as lowering blood lipids [184], anticoagulation [185], and anti-tumor [186]. In 2013, Xu et al. first extracted and purified a water-soluble novel fungus from black fungus β-Glucan [187]. It was determined to be β-(1→3)-D-glucan by gas chromatography, gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC-MS), and nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), featuring two side chains of β-(1→6)-D-glucan residues on the main chain, resulting in a comb-shaped chain structure. Viscosity measurements and light scattering techniques, including dynamic light scattering (DLS) and static light scattering (SLS), revealed a rigid adopts in water, while in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) solution it is a flexible linear cluster chain. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) results show that AF-1 can self-assemble into hollow nanofibers with a diameter of approximately 100 nm and a length of several tens of micrometers in dilute aqueous solution. And the hollow nanofibers formed can aggregate induced emission molecules and capture them into the inner cavity, leading to strong emission. Due to β-Glucan can trigger specific recognition and easy internalization in many mouse or human cells. Therefore, AF-1 is a promising candidate for development as a novel carrier for targeted cell delivery. Subsequently, the hot salt water method was used to extract cotton-like β-1,3-D-glucan substances from black fungus [188]. Using ion exchange chromatography, GC-MS, NMR and other techniques were employed to determine the chemical structure of BFP, revealing that every three main chains consist of β-1,3-D-glucose residues with two β-1,6-D-glucose branches. Research has found that the two twisting angles of glycosidic bonds on the main chain, Φ (H1-C1-03-C3) and Ψ (C1-03-C3-H3), when is 45.51 and −16.97, respectively, the BFP molecular chain is the most stable and can form a very stable triple helix structure, with each chain having lower energy than a single chain. Meanwhile, the triple helix structure is more compact than the single helix structure, and multiple hydrogen bonds are formed between different helix chains, making the helix structure very stable. The DLS/SLS results demonstrate that BFP is dispersed as a single molecular chain in extremely dilute aqueous solutions. Once the solution concentration increases, the molecular chains gradually tend to parallel arrange into thin sheets; and continuing to increase the concentration can induce the accumulation of molecular chains and even aggregate into dendritic fibers. Through transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and SEM confirm that these fibers form through the curling self-assembly of thin polysaccharide molecular sheets. The presence of hydrophobic cavities within the fibers was confirmed through aggregate induced emission molecules, further indicating the formation of dendritic nanotubes (BFP-DNTs). It is worth noting that the hydrophobic cavities of BFP-DNTs can encapsulate guest molecules, and the dendritic structure promotes an increase in the concentration of the contained guest molecules, thereby achieving a high concentration of target molecules. Study the loading and release behavior of hydrophobic molecules (DOX) on nanotubes using the hydrophobic cavities of BFP-DNTs. The experimental results showed that BFP-DNTs could achieve a relatively high DOX loading rate (34%) and encapsulation efficiency (68%), which was closely related to the tree structure and cavity of the nanotubes. Meanwhile, research has shown that BFP-DNTs can effectively protect DOX from release in normal tissues (pH = 7.4), while enabling release in affected areas (pH 5.0),, thus achieving therapeutic effects without damaging human health tissues (Fig. 9). Furthermore, BFP-DNTs glucan exhibits good biocompatibility and anti-tumor activity [188].

Figure 9: The self-assembled process scheme of Triple helix glucan (AF-1, BFP) from black fungus and Triple helix glucan (t-LNT) from lentinula edodes in water

Therefore, these new types of polysaccharide dendritic nanotubes with non-toxic side effects can provide new and effective pathways for drug delivery systems.

Besides, it was found that a lentinan from lentinula edodes, which is a triple helix structure β-(1-3)-glucan (t-LNT), which can also undergo self-assembly in water. It was found that it can also undergo self-assembly in water. Molecular dynamics simulations have found that t-LNT preferentially aggregates along the chain to form long chains, accompanied by lateral connections to form branching. Transmission electron microscopy images indicate that t-LNT forms dendritic fibers, which further form fishing net like porous/mesoporous aggregates with increasing concentration. The mesh in the fishing net is attributed to the intersection of branches. The main driving force for aggregation is expected to be the hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl groups in the t-LNT chain. Based on this self-assembled behavior, a novel composite material made of t-LNT and TPE was prepared by capturing the hydrophobic molecule tetraphenylethylene (TPE) aggregate into the t-LNT fishing net. The prepared t-LNT-TPE composite material greatly enhances the blue fluorescence of TPE in water, exhibiting stable optical properties and good biocompatibility [23].

Therefore, t-LNT is expected to serve as a potential blocking agent for hydrophobic molecules, endowing composite materials with multiple biological functions.

5 Application of Self-Assembly of Small-Molecule Active Drugs and Large-Molecule Active Drugs

5.1 Application of Self-Assembly of Two Active Drugs

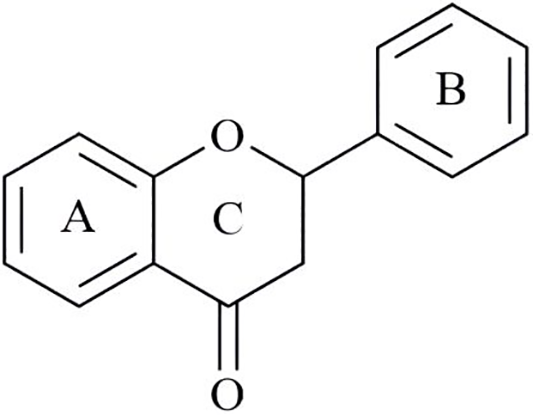

Flavonoids as the natural active ingredients in Traditional Chinese medicine (NAI-TCM) include quercetin, Cur, luteolin, Res, chrysin, baicalein, apigenin, galangin, etc. Flavonoids NAI-TCM have powerful antioxidant [189], anti-inflammatory [190], anti-atherosclerosis [191] and other effects, but their clinical application is limited by low solubility, poor compatibility, and instability in light, oxygen, heat, gastric acid and enzyme environments [192]. In order to address the drawbacks of flavonoid NAI-TCM, a series of protein micelles have been widely designed for loading flavonoid compounds in recent years. Liu et al. assembled quercetin, Cur, luteolin and Res into the hydrophobic region of quinoa protein (QP) nano micelles, thereby enhancing the water solubility and stability of flavonoid NAI-TCM. Among these four types of flavonoid NAI-TCM, the loading capacity is ranked as quercetin > luteolin > Cur > Res [193]. Zhou et al. self-assembled the editable dock protein (EDP) from the rumex plant in polygonaceae with flavonoid NAI-TCM (chrysin, baicalein, apigenin, galangin) to form micelles, which significantly enhanced the storage and digestion stability of flavonoid compounds. Among these four types of flavonoid NAI-TCM, the loading capacity is ranked as apigenin> galangin > baicalein > chrysin [194]. According to reports, proteins and flavonoids mainly bind through hydrogen bonding, hydrophobic interactions, and van der Waals forces. In addition, the hydroxyl group of flavonoids is the main active group for their binding to proteins. Previous studies have shown that the hydroxyl groups of flavonoid compounds in different rings have different activities, with the phenolic hydroxyl activity in ring A being the weakest, the phenolic hydroxyl activity in ring B being the strongest, and the phenolic hydroxyl activity in ring C also being stronger when connected to double bonds [195]. The position of phenolic hydroxyl groups not only determines the biological activity of flavonoids, but also affects the type and intensity of their interactions with proteins. This also explains that different flavonoids exhibit different loading capacities on the same protein (Fig. 10).

Figure 10: Structural formula of flavonoid