Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Effect of Drying Methods on the Morphology and Electrochemical Properties of Cellulose Gel Polymer Electrolytes for Lithium-Ion Batteries

1 National Engineering Research Center for Compounding and Modification of Polymer Materials, Guiyang, 550014, China

2 Kangmingyuan (Guizhou) Technology Development Co., Ltd., Anshun, 561100, China

3 Guizhou Jarwin Technology Co., Ltd., Guiyang, 550000, China

* Corresponding Authors: Hua Wang. Email: ; Bin Zheng. Email:

; Jiqiang Wu. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Synthesis, Processing and Mechanical Properties of Hydrogel-Based Materials)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 1143-1157. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.073414

Received 17 September 2025; Accepted 14 November 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

The pursuit of safer energy storage systems is driving the development of advanced electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries. Traditional liquid electrolytes pose flammability risks, while solid-state alternatives often suffer from low ionic conductivity. Gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) emerge as a promising compromise, combining the safety of solids with the ionic conductivity of liquids. Cellulose, an abundant and eco-friendly polymer, presents an ideal base material for sustainable GPEs due to its biocompatibility and mechanical strength. This study systematically investigates how drying methods affect cellulose-based GPEs. Cellulose hydrogels were synthesized through dissolution-crosslinking and processed using vacuum drying (VD), supercritical drying (SCD), and freeze-drying (FD). VD and SCD produced dense membranes with excellent mechanical strength (7.2 MPa) but limited electrolyte uptake (30%–40%). In contrast, FD created a highly porous structure (21.13% porosity) with remarkable electrolyte absorption (638%), leading to superior ionic conductivity (1.22 mS·cm−1) and lithium-ion transference number (0.28). However, this came at the cost of increased interfacial impedance and poor rate capability, resulting in 81.24% capacity retention after 100 cycles. These findings illuminate the critical balance between electrochemical performance and mechanical properties in cellulose GPEs, providing valuable insights for designing sustainable electrolytes for flexible electronics and electric vehicles.Keywords

The development of green renewable energy technologies is crucial to address the challenges posed by resource scarcity and environmental pollution [1–3]. Among various energy storage devices [4–6], lithium-ion batteries are extensively utilized due to their high energy density, absence of memory effect, low self-discharge rates, and stable output voltage [7–9]. Nevertheless, safety concerns remain a significant challenge for their further application. Conventional liquid electrolytes, typically composed of flammable organic carbonates, pose risks of leakage and thermal runaway under abusive conditions [10,11]. Concurrently, commercial polyolefin separators exhibit poor thermal stability and are susceptible to penetration by lithium dendrites, which can lead to internal short circuits [12,13]. The development of a safer and more stable electrolyte system is thus imperative. While all-solid-state electrolytes eliminate leakage risks, they are often hindered by low ionic conductivity and poor interfacial compatibility with electrodes [14,15]. Gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs) represent a promising compromise, encapsulating liquid electrolytes in a solid polymer matrix to mitigate leakage while maintaining satisfactory ionic conductivity and interfacial contact [16,17].

Cellulose, an abundant polymer on Earth, offers several advantages including biocompatibility, renewability, and low cost. Its structure, rich in hydrogen bonding, ensures high mechanical strength [18–20]. For instance, Xu et al. developed a nanocellulose-carboxymethyl cellulose gel polymer electrolyte for aqueous zinc-ion batteries, demonstrating good cycle stability and high ionic conductivity [21]. Similarly, Neeru et al. utilized nanocellulose to fabricate a gel polymer electrolyte for sodium-ion batteries, achieving stable sodium deposition. This electrolyte exhibited remarkable electrolyte uptake (up to 2985%) and high ionic conductivity (2.32 mS·cm−1) [22]. The methods for preparing cellulose gel electrolytes encompass sol-gel, freeze-drying, crosslinking, grafting, physical blending, and biosynthesis [23–25]. These studies highlight the potential of cellulose as a sustainable material for advanced electrolytes [26–28]. However, there is a lack of comprehensive studies that systematically compare the fundamental physicochemical and electrochemical properties of cellulose GPEs prepared using different drying techniques, which is a critical step in optimizing their structure and performance.

In this study, we systematically investigate the impact of three distinct drying methods-vacuum drying (VD), supercritical drying (SCD), and freeze-drying (FD)-on the properties of cellulose-based GPEs. A dissolution-cross-linking method is initially employed to fabricate cellulose hydrogel polymers, which are subsequently processed using the aforementioned drying techniques. The resultant GPEs are thoroughly characterized in terms of their morphology, porosity, mechanical strength, and thermal stability. More importantly, their electrochemical performance, including ionic conductivity, lithium-ion transference number, interfacial stability, and actual battery performance in LiFePO4||Li cells, is critically evaluated and correlated with their structural features. This comparative study provides valuable insights into the structure-property relationships of cellulose GPEs and establishes a clear trade-off between mechanical robustness and electrochemical performance dictated by the drying method, thereby offering practical guidance for the rational design of sustainable electrolytes for next-generation lithium-ion batteries.

Cellulose powders (particle size 50 μm), Urea (AR), Sodium hydroxide (NaOH, AR), Epichlorohydrin (ECH, AR) were supplied by Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China). Liquid electrolyte (1 M LiTFSI (lithium bis (trifluoromethane sulfonyl) imide) in DME:DOL = 1:1, v/v) was supplied from Duoduo Chemical.

2.2 Fabrication of the Cellulose Membrane

To begin, 2 g of cellulose powder was added to 40 mL of a pre-cooled NaOH/urea/water solution with the mass ratio of 7:12:81. The mixture was stirred until the cellulose powder was completely dissolved. Subsequently, the solution was centrifuged at 7000 rpm for 5 min to separate foam and a small amount of undissolved cellulose powder. A 5% solution of epichlorohydrin (ECH) was added, corresponding to a molar ratio of approximately 1:1 ECH to anhydroglucose unit of cellulose, to the cellulose solution and stirred for half an hour to obtain a uniform mixture. The mixture is then poured into a polytetrafluoroethylene mold and placed in an oven at 60°C for 3 h to undergo thermal crosslinking, resulting in the formation of the gel polymer. The crosslinking reaction proceeds under the alkaline conditions provided by the NaOH/urea solvent system. The gel polymer is then placed in deionized water for 12 h to remove excess urea and NaOH impurities, thereby obtaining the cellulose hydrogel polymer. This hydrogel polymer is then prepared into different cellulose dried gel polymers using vacuum drying, freeze-drying, and supercritical drying techniques. Vacuum drying involves first air-drying the sample at 60°C for 30 min to remove some moisture. Then, the sample is placed in a vacuum drying oven and dried at −0.6 Pa and 120°C for 12 h. Freeze-drying involves first placing the sample in a refrigerator at 2°C to obtain a supercooled solution, then putting it in a freeze dryer to cool it to −40°C and freeze it. After that, it undergoes primary drying at −20°C under a vacuum of 1.5 Pa, and then heats it up to room temperature to further remove the remaining adsorbed water. Supercritical drying was performed using CO2 after solvent exchange with ethanol. The process was carried out at 10 MPa and 40°C.

The dried cellulose gel polymers are then sliced into 16 mm diameter disks. These disks are vacuum dried for 1 h before being immediately placed in a glove box and submerged in an electrolyte solution to prepare the gel polymer electrolyte.

2.3.1 Micro-Morphology of Membranes

After the films were first dried and gold-sprayed, the surface morphology of membranes was confirmed using scanning electron microscope (SEM) with an acceleration voltage of 10 kV.

2.3.2 The Fourier Transform Infrared Spectra of Membranes

The Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra in the absorbance mode over a wavenumber ranging from 400 to 4000 cm−1 of membranes were obtained through a Bruker spectrometer testing.

2.3.3 Thermal Properties of Membranes

TGA was used to evaluate the thermal stability of the membranes and the effect of drying methods. 20 mg of each sample was weighed and heated from 40°C to 450°C at a rate of 10°C per minute in nitrogen atmosphere.

2.3.4 Electrolyte Uptake of Membranes

The cellulose membranes were placed in a glove box containing argon gas and soaked in an electrolyte. The electrolyte uptake rate was determined by measuring the weight of the cellulose gel polymer electrolyte at different time periods, and the electrolyte uptake rate was calculated by Eq. (1):

where η is the swelling ratio, w0 and w1 represent the weight of the membrane sample before and after swelling in liquid electrolyte, respectively. All measurements were performed in triplicate (n = 3).

According to GB/T 30693-2014, the cellulose dry gel polymer was cut into 1 cm

According to GB/T 104.1-2006, the gel polymer samples were first cut into rectangular samples of 60 mm × 10 mm. Then, tensile tests were conducted on the samples at a speed of 10 mm/min using an experimental universal tensile testing machine (SANS), and the mechanical properties of all samples were studied. All samples were subjected to three repeated experiments.

2.4 Electrochemical Characterizations

Before testing the ionic conductivity, the gel electrolyte samples were assembled into coin cells with two stainless steel (SS) as positive and negative electrodes. The ionic conductivity was measured by electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS). The frequency range is 10−2 to 106 Hz, and the AC voltage is 10 mV. The final value is calculated by Eq. (2):

where σ is the ionic conductivity, L (cm) represents the thickness of the gel electrolyte and S (cm2) is the effective contact area of the electrode and the gel electrolyte, and Rb is the bulk resistance of the battery. Besides, the above experiments were performed at 25°C to 45°C to study the relationship between ionic conductivity and temperature. The thickness (L) was measured for each swollen gel electrolyte disk using a digital micrometer. Values reported are the average from three independent membrane samples (n = 3) for each drying condition.

2.4.2 The Lithium-Ion Transference Number

The Bruce-Vincent method was applied, and the cells were stabilized for 1 h at the polarization voltage (ΔV = 10 mV) before recording the initial current (I0) and resistance (R0). The polarization was maintained until a steady-state current (IS) was achieved after 1 h, at which point the final resistance (RS) was measured. The gel electrolyte samples were assembled into coin cells with a pair of lithium disks as positive and negative electrodes, before testing the lithium-ion transference number. The lithium-ion transference number was obtained by EIS and chronoamperometry, and then calculated by Eq. (3):

where

2.4.3 The Interfacial Compatibility

The interfacial compatibility was obtained by testing a coin cell consisting of a pair of lithium electrodes and a gel electrolyte. In addition, EIS was measured on the first, third and seventh days, respectively.

2.4.4 The Electrochemical Stability

The electrochemical stability of a coin cell, consisting of lithium as the negative electrode and stainless steel as the positive electrode, was determined by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) with voltages ranging from −0.5 to 5 V at a scan rate of 1 mV/s.

First, a button battery (LiFePO4/GE/Li) with lithium as the negative electrode and LiFePO4 as the positive electrode was assembled, and then the battery performance was obtained through the test of the charging and discharging battery equipment (NEWARE CT-4008T), and the cut-off voltage is set as 2.5–4.2 V.

3.1 Characterization of Cellulose Gel Polymers

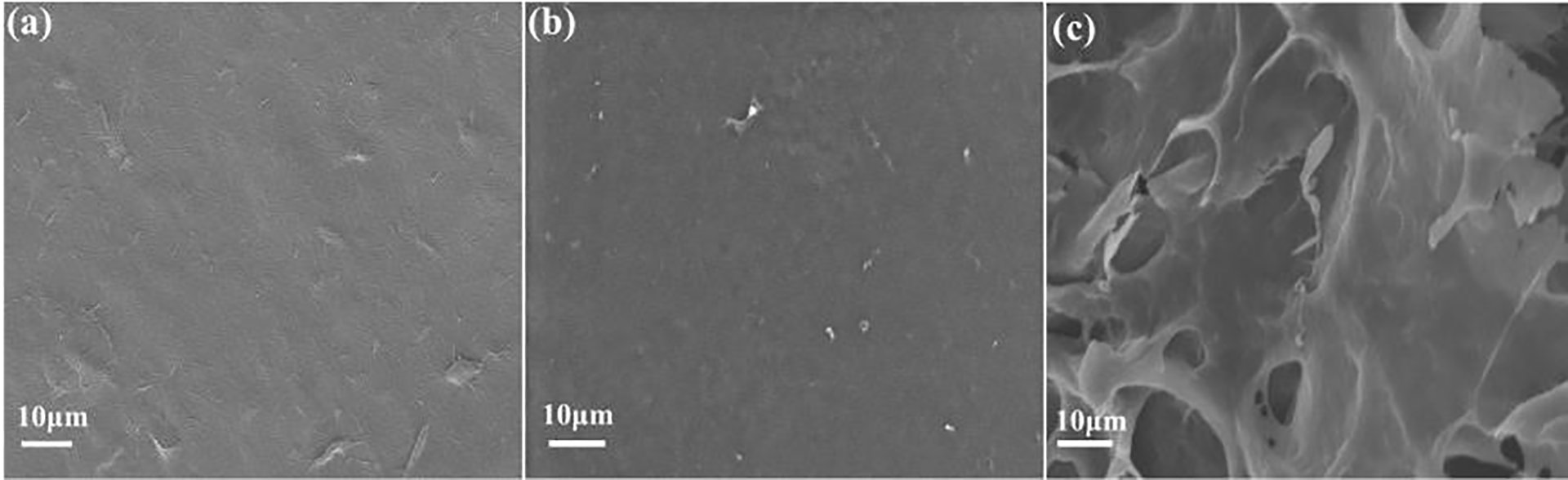

3.1.1 Morphology Analysis of Cellulose Gel Polymers

Fig. 1a illustrates the micro-morphology of cellulose gel polymers dried using a vacuum drying technique. The surface of the VD cellulose gel polymer is observed to be notably dense, exhibiting minimal visible pore structures and only subtle line markings. Fig. 1b provides an image of the surface of cellulose gel polymers dried via supercritical drying. The micro-surface of the SCD sample is similarly dense and lacks discernible pore structures, presenting an exceptionally smooth appearance. Notably, supercritical drying is a method commonly employed for the preparation of porous gel polymers; however, the SEM image does not reveal any pore structures. The dense morphology observed in the SCD sample is likely due to pore collapse during the solvent exchange step with ethanol, which can compromise the nascent porous network of the cellulose hydrogel prior to supercritical CO2 processing. Fig. 1c depicts the surface of cellulose gel polymers dried through freeze-drying. The surface of the FD cellulose gel polymer is observed to be considerably rough, characterized by numerous pit-like structures. This can be attributed to the fact that during the freeze-drying process, the solvent water first solidifies into ice, expanding the original pores of the matrix. After sublimation drying, the pore structure remains intact. As a result, the FD cellulose gel polymer displays pit-like structures that, in contrast to the smooth surfaces of the VD and SCD samples, are more effective in retaining a larger volume of electrolyte.

Figure 1: SEM of cellulose gel polymer surfaces, (a) VD, (b) SCD, (c) FD

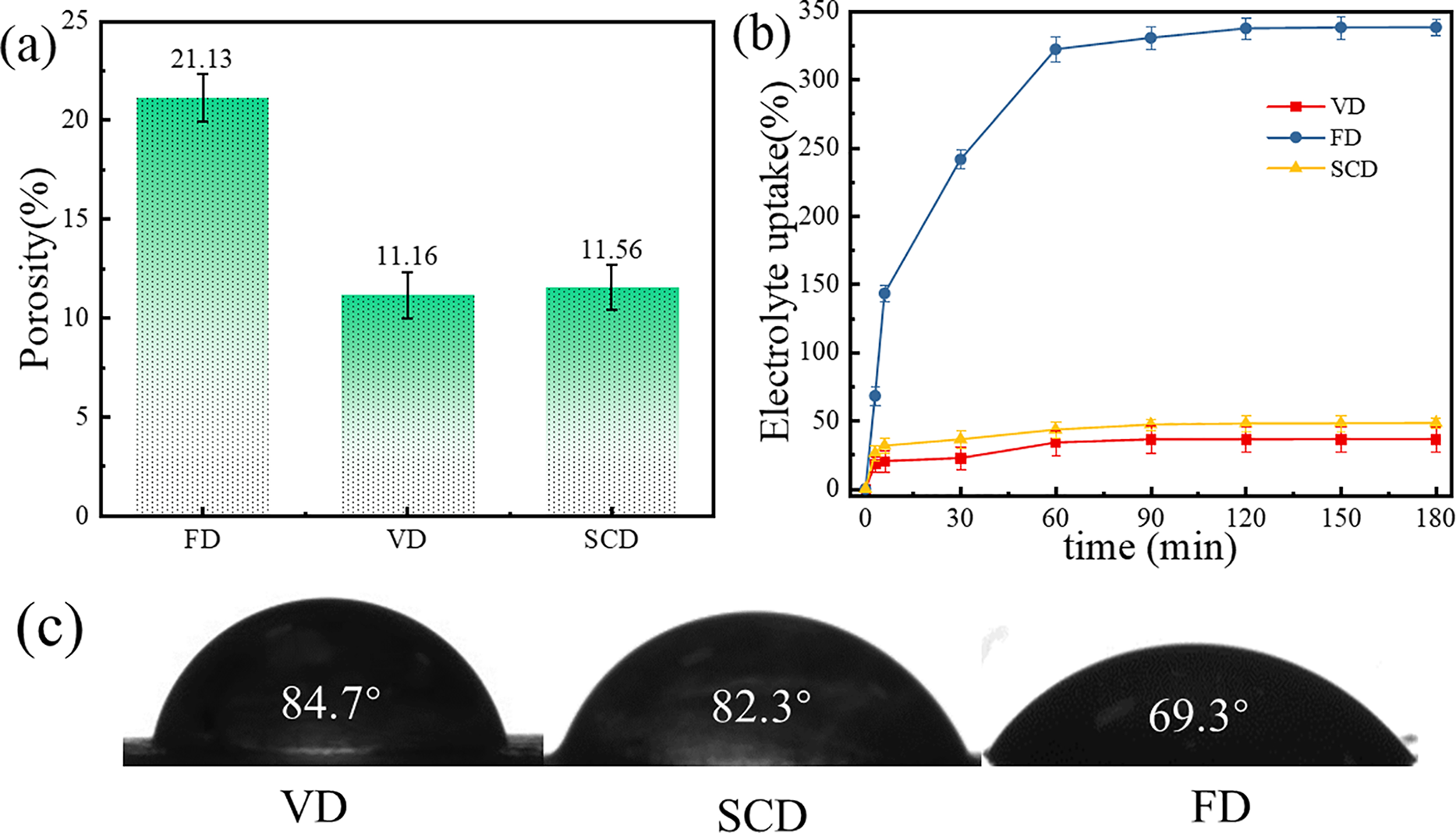

3.1.2 Analysis of Electrolyte Uptake Behavior of Cellulose Gel Polymers

Fig. 2a displays the porosity of the cellulose gel polymers. The porosity of the cellulose gel polymers dried using vacuum and supercritical drying methods is almost equivalent, with values of 11.16% and 11.56%, respectively. In contrast, the freeze-dried cellulose gel polymer exhibits a substantially higher porosity of 21.13%, surpassing the porosity of the other two samples. This finding aligns with the SEM image analysis. Fig. 2b illustrates the electrolyte absorption characteristics of the cellulose gel polymer electrolytes. The absorption behaviors of the VD and SCD cellulose gel polymers are relatively consistent, reaching equilibrium after approximately 6 min with absorption rates of approximately 30% and 40%, respectively. The freeze-dried gel polymer reached 638% electrolyte absorption after 60 min. A higher absorption rate enhances ionic conductivity and lithium-ion transference number, critical for electrochemical performance [22]. To ascertain the affinity between the samples and the electrolyte, contact angle measurements were performed. Fig. 2c presents the contact angle results for the cellulose gel polymers, with contact angles of 84.7°, 82.3° and 69.3° for the VD, SCD and FD cellulose gel polymers, respectively. These results corroborate that the freeze-dried cellulose gel polymer demonstrates a greater affinity for the electrolyte, enabling it to absorb a larger quantity of electrolyte and, consequently, to improve its electrochemical performance.

Figure 2: (a) Porosity of cellulose gel polymers; (b) Electrolyte uptake rate of cellulose gel polymers; (c) Contact angle of cellulose gel polymers

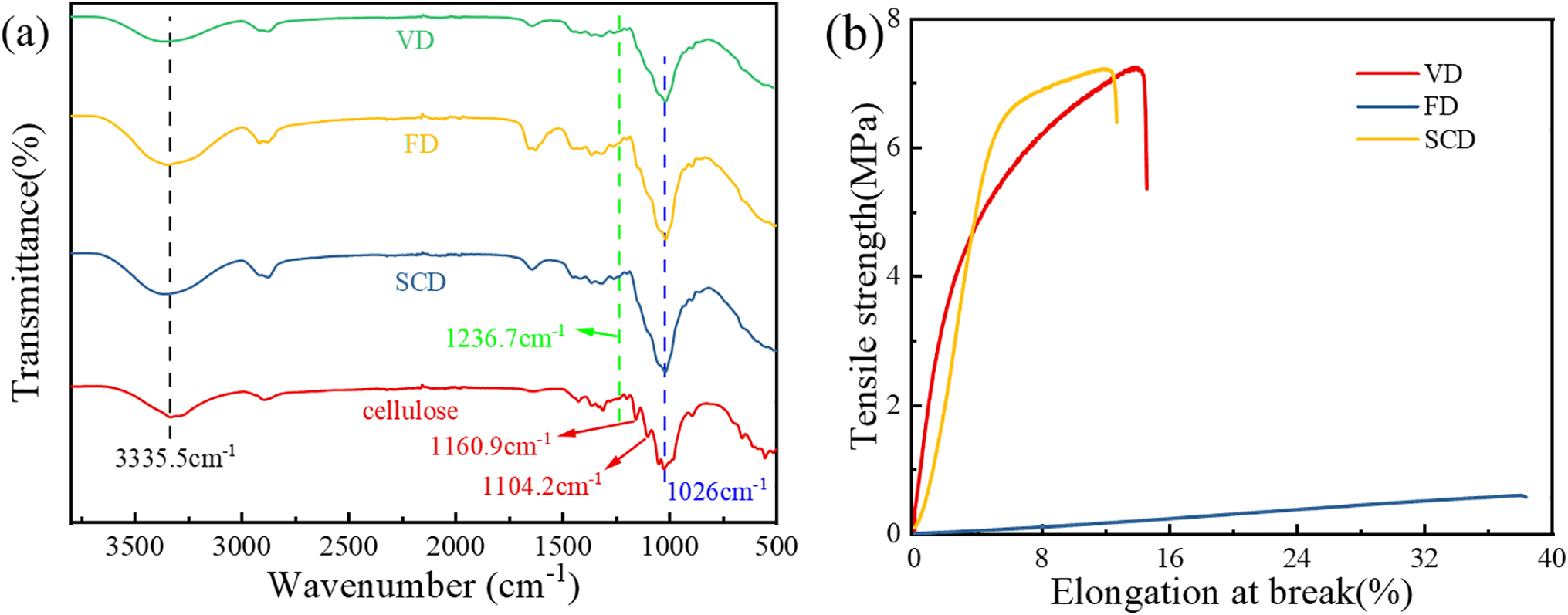

3.1.3 Analysis of Structure and Physical Properties of Cellulose Gel Polymer

Fig. 3a displays the Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) spectra of cellulose gel polymers prepared with VD, SCD and FD. Given that all samples are cellulose gel polymers differing only in drying technique, their FTIR spectra are fundamentally identical. The spectra feature several characteristic infrared peaks of cellulose: a broad absorption peak at 3335.5 cm−1, corresponding to the O-H stretching vibration; a strong peak at 1026 cm−1, indicative of the C-O stretching vibration; and a weak peak at 1236.7 cm−1, attributed to the C-O-C stretching vibration between glucose units [29]. In the infrared spectrum of cellulose powder, peaks at 1160.9 and 1104.2 cm−1 represent the C-O stretching modes of primary and secondary alcohols in cellulose, respectively [30]. However, these peaks are absent in the cellulose gel polymers prepared by the aforementioned drying methods, suggesting successful crosslinking of cellulose with ECH to form a network structure [31]. Fig. 3b depicts the tensile curves of the cellulose gel polymers. The breaking stress for the cellulose gel polymers dried by VD and SCD is 7.24 and 7.22 MPa, respectively, with breaking elongation rates of 14.44% and 12.64%. The tensile curves for these two samples are essentially similar, whereas the freeze-dried cellulose gel polymer exhibits a breaking stress of 0.60 MPa and a breaking elongation rate of 38.31%. Abundant hydroxyl groups in cellulose form intra- and intermolecular hydrogen bonds, endowing all gel polymers with mechanical strength. In the densely structured VD and SCD samples, the chemical crosslinks formed by ECH create a robust covalent network framework. This framework is further reinforced by a high density of hydrogen bonds between cellulose chains, which are preserved due to the minimal macroscopic shrinkage during these drying processes. The synergy between the covalent crosslinking network and the extensive hydrogen bonding network is responsible for the high mechanical strength observed in these samples. In contrast, the porous structure of the FD sample inherently reduces the number of load-bearing polymer chains per unit area and likely disrupts the continuity of the hydrogen-bonding network, leading to inferior mechanical properties.

Figure 3: (a) FT-IR of cellulose gel polymer electrolyte, (b) Tensile properties of cellulose gel polymer electrolyte

3.2 Electrochemical Properties of Cellulose Gel Polymer Electrolyte

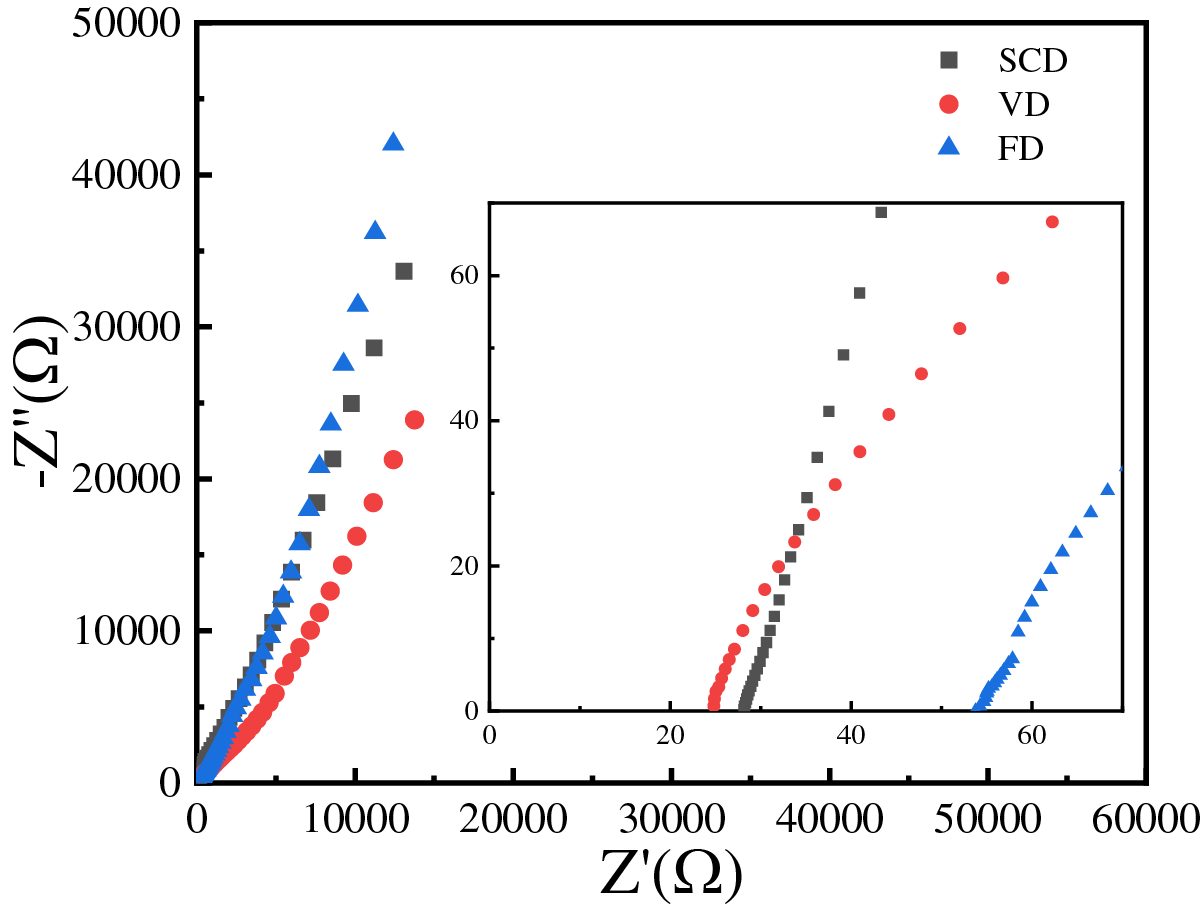

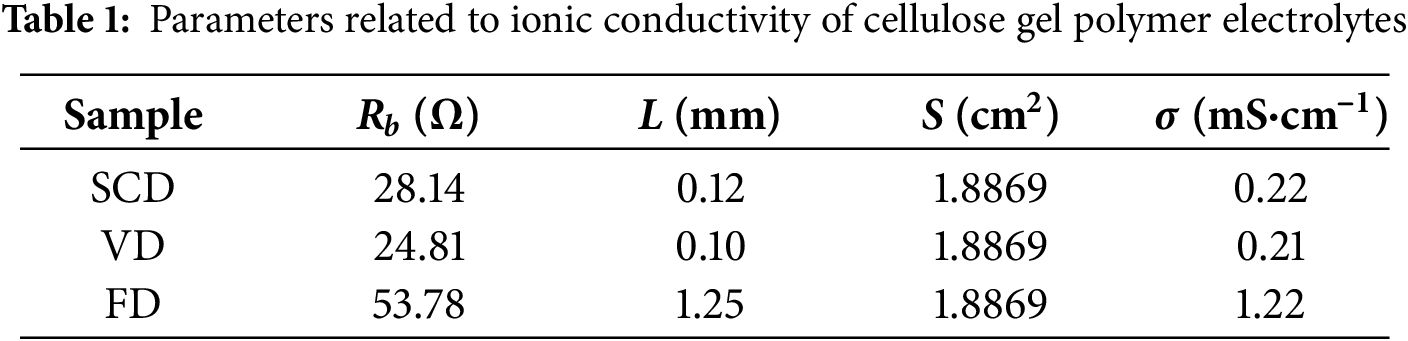

3.2.1 Ionic Conductivity of Cellulose Gel Polymer Electrolytes

Ionic conductivity is a critical parameter that influences the electrochemical performance of batteries. Fig. 4 illustrates the alternating current impedance spectra of symmetric stainless steel coin cells, which are used to determine the ionic conductivity of the samples. All samples exhibit a characteristic non-vertical peak, and the intersection of the peak with the x-axis indicates the bulk resistance (Rb). The parameters necessary for calculating the ionic conductivity are provided in Table 1. The ionic conductivities of the cellulose gel polymer electrolytes, prepared by SCD, VD and FD, are 0.22, 0.21 and 1.22 mS·cm−1, respectively. It is apparent that the ionic conductivities of the electrolytes prepared by vacuum and supercritical drying are similar and significantly lower than that of the FD electrolyte. This is due to the higher electrolyte absorption rate of the FD cellulose gel polymer electrolyte compared to those prepared by vacuum and supercritical drying. Ion transport in gel polymer electrolytes primarily occurs through the swollen phase within the electrolyte, and a higher absorption rate results in a larger swollen phase, enhancing ion transport efficiency.

Figure 4: EIS of cellulose gel polymer electrolyte

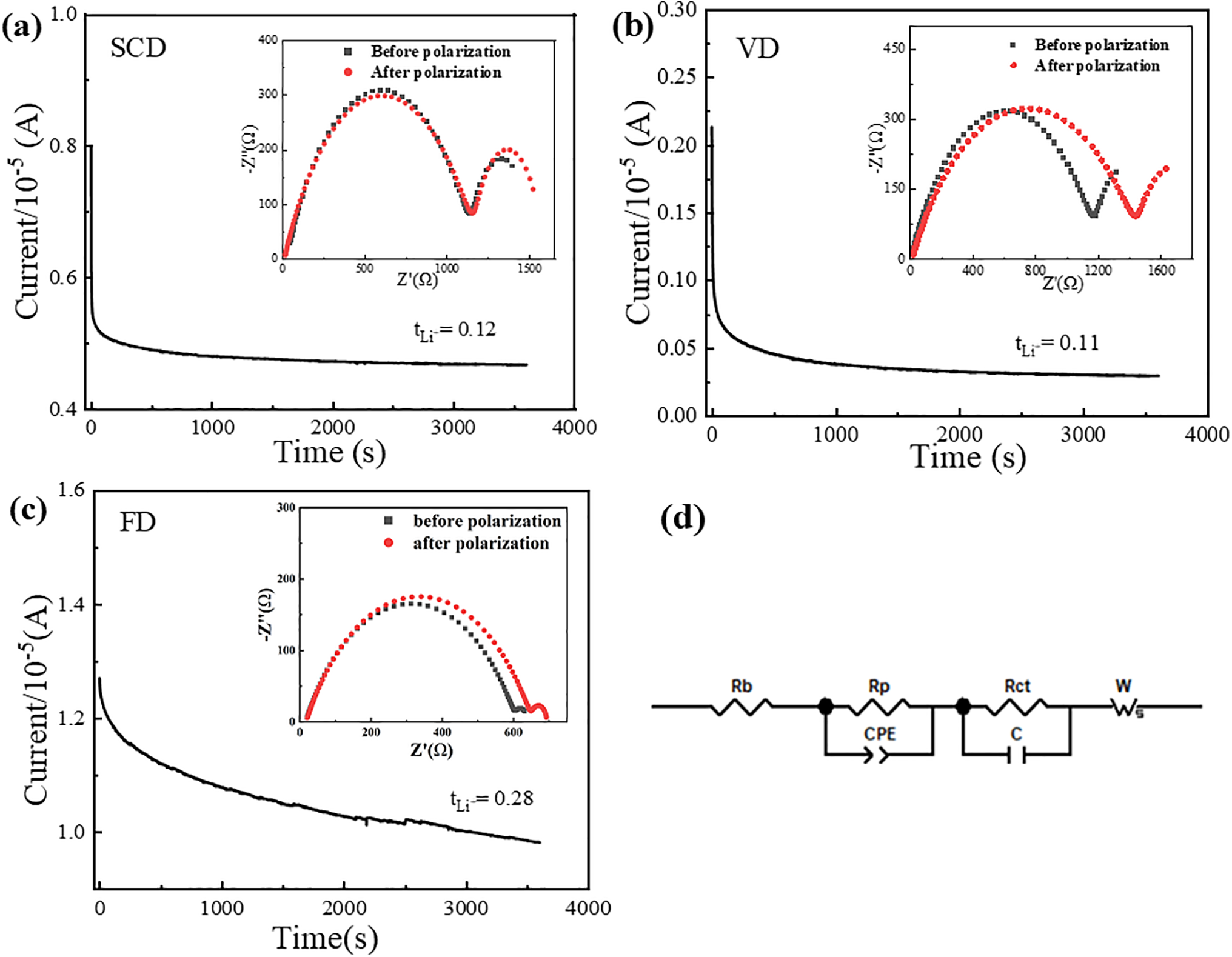

3.2.2 Lithium Ion Migration Number

The lithium-ion transference number is an essential parameter for evaluating gel polymer electrolytes. While ionic conductivity measures the overall electrical conductivity of ions, the lithium-ion transference number specifically reflects the migration capability of lithium ions. It is defined as the ratio of lithium-ion migration to the total ion migration [32]. Fig. 5 shows the AC electrochemical impedance spectra and current vs. time (i-t) plots for each sample, with the parameters required for calculating the lithium-ion transference number listed in Table 2. The lithium-ion transference numbers for the cellulose gel polymer electrolytes, prepared by SCD, VD and FD, are 0.12, 0.11, and 0.28, respectively. The relatively low transference numbers for all samples suggest that the proportion of lithium ions participating in migration is small. The good affinity and absorption retention performance of the separator for the electrolyte determine the content of the electrolyte within the electrolyte membrane, which in turn affects the quantity and speed of lithium-ion migration involved in the electrochemical reaction. The rough surface of the FD sample provides more binding sites for the separator and the electrolyte and a high electrolyte absorption rate, thereby showing a higher lithium-ion migration number. The lithium-ion transference number is directly related to the rate capability of the samples, and the lower transference numbers imply that the rate capabilities of the three samples may be suboptimal.

Figure 5: Li+ transport number test of cellulose gel polymer electrolyte, (a) SCD, (b) VD, (c) FD, (d) equivalent circuits

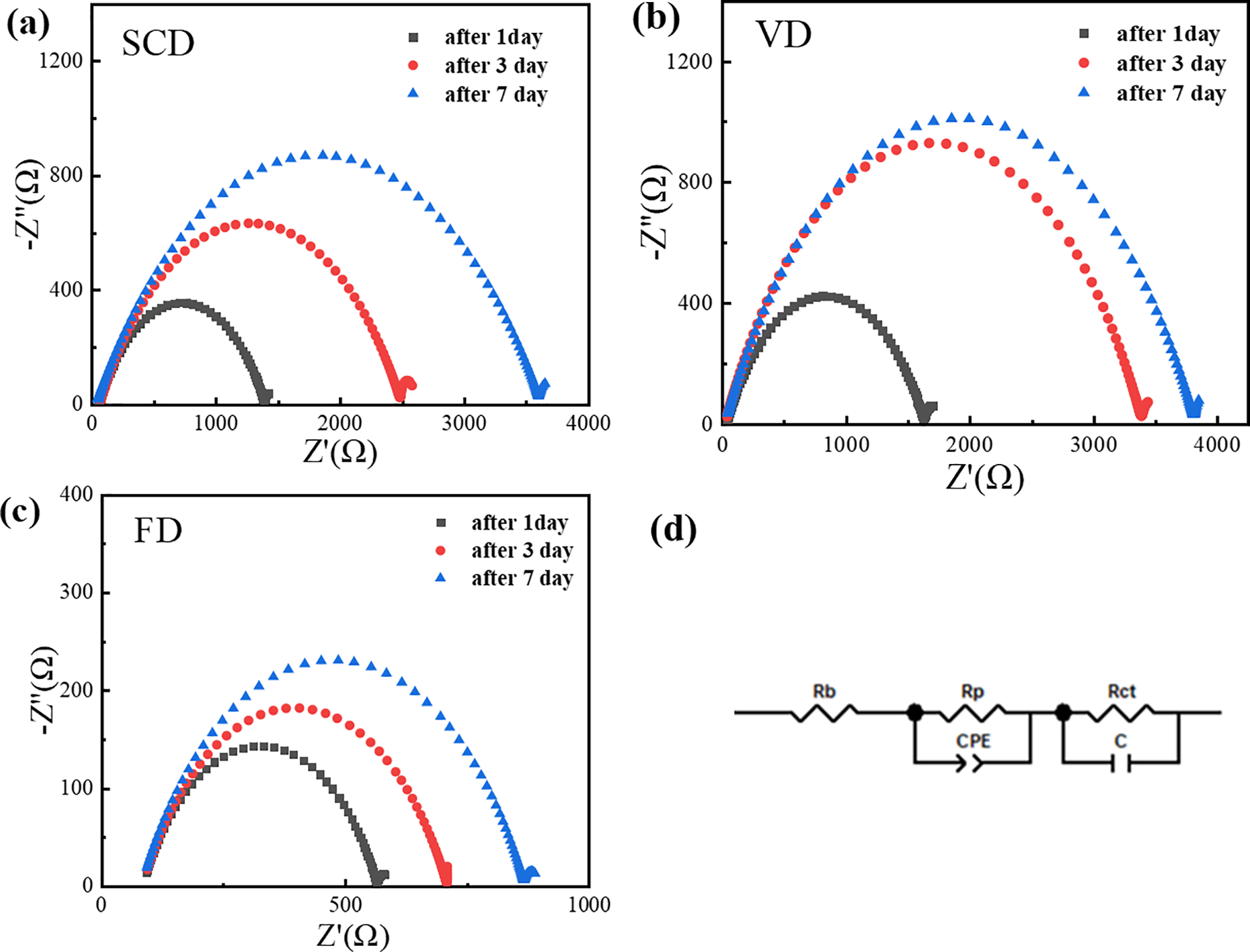

Interface impedance quantifies the compatibility between GPEs and electrodes, as well as the ease with which lithium ions can migrate from the electrode to the electrolyte. A higher interface impedance signifies poorer compatibility and a more challenging ion transfer process. Fig. 6 depicts the electrochemical AC impedance spectra for each sample, all of which exhibit a characteristic semicircular curve. The diameter of the semicircle at the intersection with the X-axis represents the interface impedance of the gel polymer electrolyte.

Figure 6: EIS of cellulose gel polymer electrolytes. (a) SCD, (b) VD, (c) FD, (d) fitted circuits

For the battery assembled with VD cellulose GPE, the interface impedances on the first, third, and seventh days were 1627.6, 3383.7, and 3806.5 Ω, respectively. For the SCD electrolyte, the interface impedances were 1386.8, 2482.4, and 3597.7 Ω on the corresponding days. The interface impedances of the VD and SCD cellulose GPEs were comparable, whereas the FD gel polymer electrolyte exhibited significantly lower interface impedances, with values of 565.24, 709.3, and 868.5 Ω on the first, third, and seventh days, respectively. This suggests that the transfer of ions from the electrode to the cellulose gel polymer electrolyte was more challenging for the batteries assembled with the VD and SCD electrolytes compared to the FD one. This difference contributes to the inferior ionic conductivities of the VD and SCD cellulose gel polymer electrolytes relative to the FD counterpart.

As previously discussed, solid-state electrolytes often exhibit high interface impedance due to the absence of liquid electrolyte. The FD cellulose gel polymer electrolyte, in contrast to the VD and SCD versions, can absorb and retain more electrolyte, thereby exhibiting lower interface impedance. Nevertheless, the interfacial impedance for all samples, including the FD GPE, increased over time, indicating progressive interfacial instability against lithium metal. This is likely due to reactions between lithium and the abundant hydroxyl groups on the cellulose surface, leading to the formation of an unstable solid electrolyte interphase and continuous electrolyte consumption.

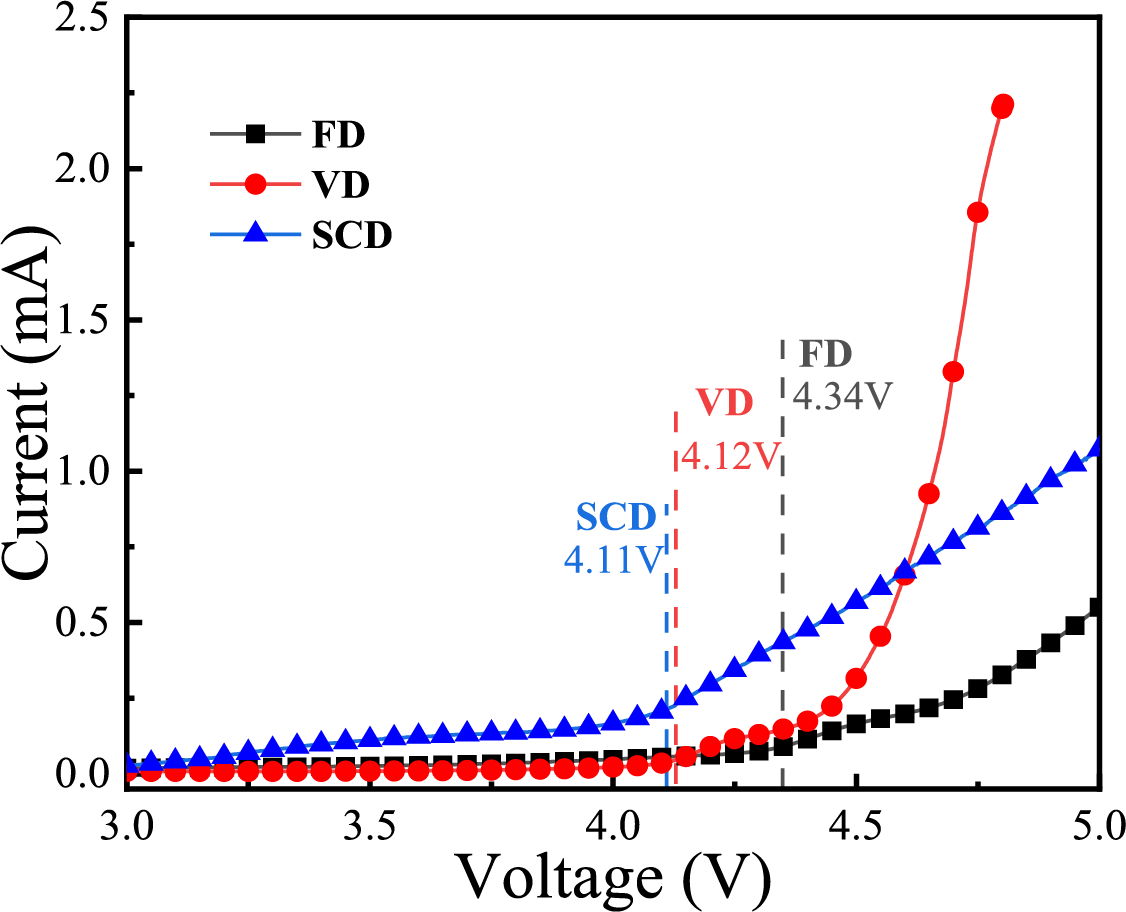

3.2.4 Electrochemical Stability Window

The electrochemical stability window is a pivotal parameter for assessing the operational voltage range of gel polymer electrolytes. Fig. 7 presents the linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) plots for the cellulose gel polymer electrolytes prepared by VD, SCD and FD. The voltage at which the LSV curve begins to deviate indicates the maximum operational voltage for the GPE; exceeding this voltage can lead to electrolyte decomposition. The maximum operational voltages for the cellulose GPEs prepared by VD, SCD and FD are 4.12, 4.11, and 4.34 V, respectively. It is noted that the ether-based electrolyte (DME:DOL) was selected for this fundamental study due to its high ionic conductivity and good wettability with cellulose, which are beneficial for initial screening of the gel matrix properties. While ethers are less commonly used with high-voltage cathodes, the LSV results indicate an oxidative stability limit of up to 4.34 V for the FD sample, which is sufficient for the operation of LiFePO4 (~3.45 V vs. Li/Li+).

Figure 7: Plot of LSV curve of cellulose gel polymer electrolyte

To contextualize the performance of our cellulose GPEs, Table 3 compares their key properties with those of other recently reported cellulose-based GPEs. From the literature comparison, it can be seen that the performance of the pure cellulose separator obtained by freeze-drying method in this work is superior to that of some cellulose separators after composite modification, which indicates that the manufacturing process has a significant impact on the performance of the separator. Of course, the diaphragms modified by some cellulose composites have better performance. However, the main research purpose of this work is to investigate the influence of drying methods on the performance of cellulose gel electrolytes. Further improvement of the performance of gel electrolytes will be carried out in subsequent studies.

3.2.5 Performance of the Assembled Half Battery

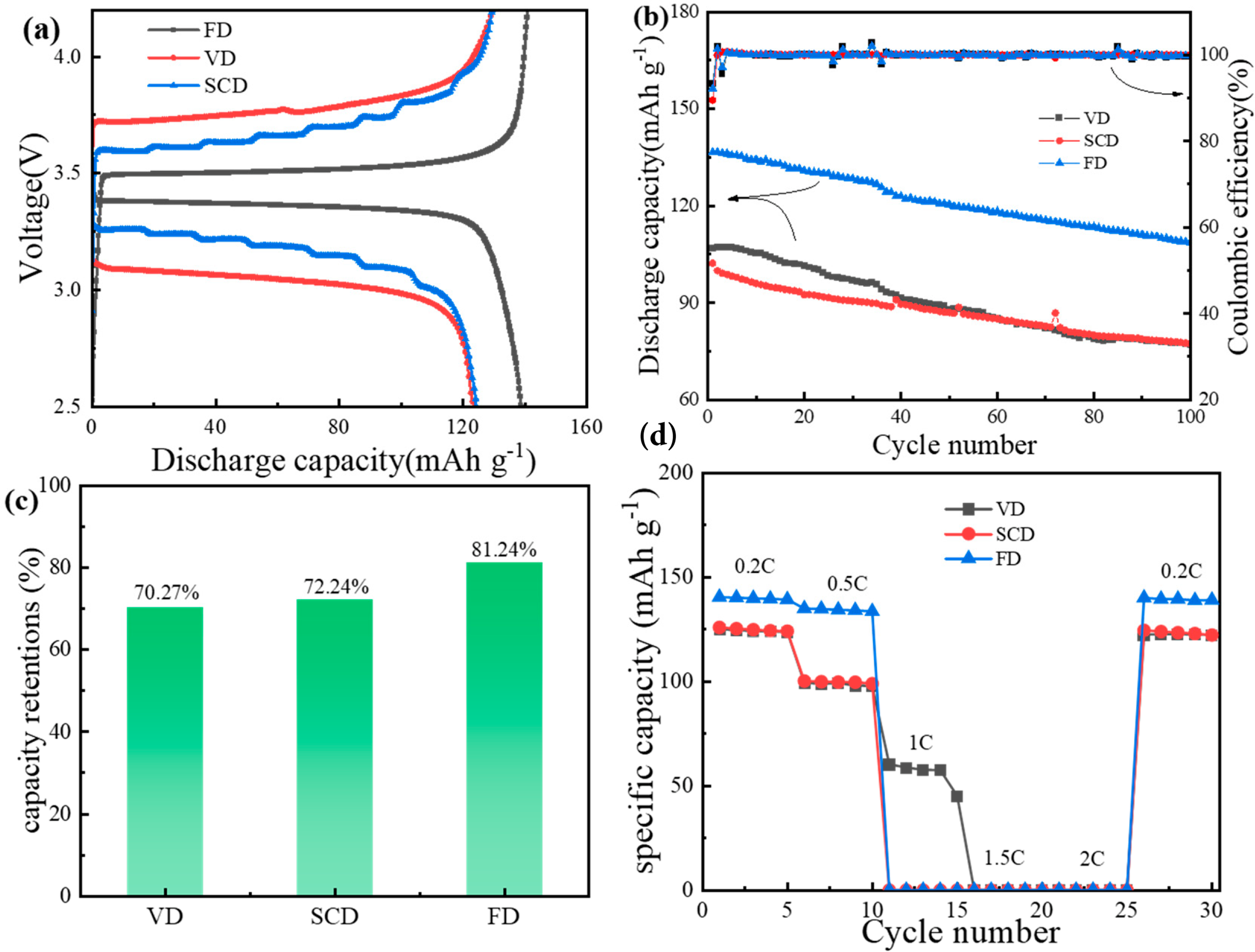

The practical application of the cellulose gel polymer electrolyte in battery systems can be assessed by assembling a half-cell with a lithium metal anode and a LiFePO4 cathode. Fig. 8a displays the initial charge and discharge curves of the half-cell at 0.2 C, with all curves showcasing the typical profiles of a LiFePO4 cathode, featuring a platform voltage around 3.4 V. The first discharge specific capacity of the FD cellulose GPE is 138.78 mAh·g−1, which is notably higher than that of the VD (123.67 mAh·g−1) and SCD (124.54 mAh·g−1) cellulose GPEs. This result can be considered as a result of the higher ionic conductivity of the freeze-dried electrolyte, which facilitates the full utilization of the theoretical specific capacity of the cathode material.

Figure 8: Performance of half-cells assembled with cellulose gel polymer electrolyte using LiFePO4 as cathode. (a) first charge/discharge graph, (b) cycling performance, (c) specific capacity retention, (d) rate performance

Fig. 8b illustrates the cycling performance of the half-cell at 0.5 C over 100 cycles, with all three samples maintaining a coulombic efficiency of approximately 100% during the cycling. Nevertheless, there is a variation in the capacity retention after 100 cycles, as depicted in Fig. 8c. The FD cellulose GPE demonstrates a capacity retention rate of 81.24%, which exceeds that of the VD (70.27%) and SCD (72.24%) ones. This result may be due to the fact that vacuum-dried and supercritical dried electrolytes have greater interface impedance than freeze-dried electrolytes, which leads to battery polarization and hinders the full expression of the theoretical specific capacity of the cathode, thus affecting the cycle performance [33].

Fig. 8d demonstrates the rate capability of the half-cell, revealing that the rate performance of the cellulose gel polymer electrolytes prepared by the different drying methods is suboptimal, with the discharge specific capacity at high rates dropping to nearly 0 mAh·g−1. However, when the rate is back to 0.2 C, the specific capacity is restored, indicating that at high rates, the theoretical specific capacity of the cathode material is not fully realized, rather than an internal short circuit causing the abnormal charge-discharge behavior. The poor rate capability can be attributed to several factors rooted in the transport limitations: (1) The low lithium-ion transference number limits the proportion of current carried by Li+ ions. (2) The high and increasing interfacial impedance, especially for VD and SCD samples, hinders efficient charge transfer. (3) Microstructurally, the low electrolyte uptake and lack of interconnected pores in VD and SCD samples severely restrict ionic pathways and the supply of Li+ ions at high currents. For the FD sample, despite high overall porosity and uptake, the pit-like cavities observed in SEM may lack optimal connectivity, leading to high tortuosity. Furthermore, the relatively thick FD membrane (1.25 mm) results in a long Li+ diffusion path, which becomes critically limiting at high current densities.

This study commenced with the utilization of epichlorohydrin to crosslink cellulose solutions, thereby yielding cellulose hydrogel polymers. These polymers were subsequently subjected to three distinct drying methods: vacuum drying, supercritical drying, and freeze-drying, resulting in a range of cellulose gel polymer electrolytes. The impacts of these diverse drying techniques on the morphology, physical properties, and electrochemical performance of the cellulose gel polymer electrolytes were meticulously examined. SCD and VD produced dense, film-like morphologies with robust mechanical properties but low electrolyte absorption rates. Conversely, the FD cellulose GPEs displayed a structure with pronounced curling and pit-like cavities, indicating inferior mechanical properties but enabling enhanced electrolyte absorption (up to 638%) and superior ionic conductivity (1.22 mS·cm−1). However, this came at the cost of mechanical strength and led to only moderate cycling stability (81.24% capacity retention) and poor rate performance. These findings highlight the critical trade-off between achieving high electrochemical performance and the choice of preparation process. Therefore, freeze-drying is identified as the most suitable method for applications prioritizing ionic conductivity and absorption, provided that mechanical robustness and high-rate capability are secondary concerns. This work suggest potential for use in flexible electronics and EVs. Future efforts will focus on improving tLi+ via composite design and interfacial engineering.

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (52063005), Guizhou Province Science and Technology Achievement Transformation Project [2025] general 020, Central Guiding Local Science and Technology Development Funds [2024]020 and [2025]013, ZZSG [2024]015, KXJZ [2025]037.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Jiling Song: Experimental ideas and scheme design, Conducting research and investigation process, Data curation, Writing—original draft preparation, Writing—reviewing and editing. Hua Wang: Supervision. Jianbing Guo: Experimental ideas and scheme design, Funding acquisition, Provision of study materials. Minghua Lin: Writing—reviewing and editing. Bin Zheng: Experimental ideas and scheme design, Sample testing, Data curation. Jiqiang Wu: Supervision. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding authors.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Wen X, Luo J, Xiang K, Zhou W, Zhang C, Chen H. High-performance monoclinic WO3 nanospheres with the novel NH4+ diffusion behaviors for aqueous ammonium-ion batteries. Chem Eng J. 2023;458:141381. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.141381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. Yu F, Zhang H, Zhao L, Sun Z, Li Y, Mo Y, et al. A flexible cellulose/methylcellulose gel polymer electrolyte endowing superior Li+ conducting property for lithium ion battery. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;246:116622. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116622. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Ahmad F, Shahzad A, Sarwar S, Inam H, Waqas U, Pakulski D, et al. Gel polymer electrolyte composites in sodium-ion batteries: synthesis methods, electrolyte formulations, and performance analysis. J Power Sources. 2024;619:235221. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2024.235221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Mu X, Song Y, Qin Z, Meng J, Wang Z, Liu XX. Core-shell structural vanadium oxide/polypyrrole anode for aqueous ammonium-ion batteries. Chem Eng J. 2023;453:139575. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2022.139575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Li D, Guo H, Jiang S, Zeng G, Zhou W, Li Z. Microstructures and electrochemical performances of TiO2-coated Mg–Zr co-doped NCM as a cathode material for lithium-ion batteries with high power and long circular life. New J Chem. 2021;45(41):19446–55. doi:10.1039/d1nj03740d. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Yang H, Lee J, Cheong JY, Wang Y, Duan G, Hou H, et al. Molecular engineering of carbonyl organic electrodes for rechargeable metal-ion batteries: fundamentals, recent advances, and challenges. Energy Environ Sci. 2021;14(8):4228–67. doi:10.1039/d1ee00419k. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Zhao H, Kang W, Deng N, Liu M, Cheng B. A fresh hierarchical-structure gel poly-m-phenyleneisophthalamide nanofiber separator assisted by electronegative nanoclay-filler towards high-performance and advanced-safety lithium-ion battery. Chem Eng J. 2020;384:123312. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2019.123312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Zhang K, Yin J, He Y. Acoustic emission detection and analysis method for health status of lithium ion batteries. Sensors. 2021;21(3):712. doi:10.3390/s21030712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Kohan E, Khoshnavazi R, Hosseini MG, Salimi A, Salami-Kalajahi M. A review on instability factors of mono- and divalent metal ion batteries: from fundamentals to approaches. J Mater Chem A. 2024;12(44):30190–248. doi:10.1039/d4ta05386a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ranque P, Zagórski J, Accardo G, Orue Mendizabal A, López del Amo JM, Boaretto N, et al. Enhancing the performance of ceramic-rich polymer composite electrolytes using polymer grafted LLZO. Inorganics. 2022;10(6):81. doi:10.3390/inorganics10060081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Zhou Q, Dong S, Lv Z, Xu G, Huang L, Wang Q, et al. A temperature-responsive electrolyte endowing superior safety characteristic of lithium metal batteries. Adv Energy Mater. 2020;10(6):1903441. doi:10.1002/aenm.201903441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Babiker DMD, Usha ZR, Wan C, Hassaan MME, Chen X, Li L. Recent progress of composite polyethylene separators for lithium/sodium batteries. J Power Sources. 2023;564:232853. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2023.232853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhang Z, Li Y, Cui X, Guan S, Tu L, Tang H, et al. Understanding the advantageous features of bacterial cellulose-based separator in Li–S battery. Adv Mater Interfaces. 2023;10(1):2201730. doi:10.1002/admi.202201730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Lv D, Chai J, Wang P, Zhu L, Liu C, Nie S, et al. Pure cellulose lithium-ion battery separator with tunable pore size and improved working stability by cellulose nanofibrils. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;251:116975. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116975. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Sheng J, Tong S, He Z, Yang R. Recent developments of cellulose materials for lithium-ion battery separators. Cellulose. 2017;24(10):4103–22. doi:10.1007/s10570-017-1421-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Chai J, Liu Z, Ma J, Wang J, Liu X, Liu H, et al. In situ generation of poly (vinylene carbonate) based solid electrolyte with interfacial stability for LiCoO2 lithium batteries. Adv Sci. 2016;4(2):1600377. doi:10.1002/advs.201600377. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Y, Lu W, Cong L, Liu J, Sun L, Mauger A, et al. Cross-linking network based on Poly(ethylene oxidesolid polymer electrolyte for room temperature lithium battery. J Power Sources. 2019;420:63–72. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.02.090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Huang Y, Wang Y, Fu Y. All-cellulose gel electrolyte with black phosphorus based lithium ion conductors toward advanced lithium-sulfurized polyacrylonitrile batteries. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;296:119950. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

19. Zhu Y, Cao K, Cheng W, Zeng S, Dou S, Chen W, et al. A non-Newtonian fluidic cellulose-modified glass microfiber separator for flexible lithium-ion batteries. EcoMat. 2021;3(4):e12126. doi:10.1002/eom2.12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Chen Y, Qiu L, Ma X, Dong L, Jin Z, Xia G, et al. Electrospun cellulose polymer nanofiber membrane with flame resistance properties for lithium-ion batteries. Carbohydr Polym. 2020;234:115907. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.115907. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Xu L, Meng T, Zheng X, Li T, Brozena AH, Mao Y, et al. Nanocellulose-carboxymethylcellulose electrolyte for stable, high-rate zinc-ion batteries. Adv Funct Mater. 2023;33(27):2302098. doi:10.1002/adfm.202302098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Mittal N, Tien S, Lizundia E, Niederberger M. Hierarchical nanocellulose-based gel polymer electrolytes for stable Na electrodeposition in sodium ion batteries. Small. 2022;18(43):1–12. doi:10.1002/smll.202107183. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Long LY, Weng YX, Wang YZ. Cellulose aerogels: synthesis, applications, and prospects. Polymers. 2018;10(6):623. doi:10.3390/polym10060623. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Jiménez-Saelices C, Seantier B, Cathala B, Grohens Y. Spray freeze-dried nanofibrillated cellulose aerogels with thermal superinsulating properties. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:105–13. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.068. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Xu D, Wang B, Wang Q, Gu S, Li W, Jin J, et al. High-strength internal cross-linking bacterial cellulose-network-based gel polymer electrolyte for dendrite-suppressing and high-rate lithium batteries. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10(21):17809–19. doi:10.1021/acsami.8b00034. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

26. Tran TH, Okabe H, Hidaka Y, Hara K. Removal of metal ions from aqueous solutions using carboxymethyl cellulose/sodium styrene sulfonate gels prepared by radiation grafting. Carbohydr Polym. 2017;157:335–43. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.09.049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

27. Song A, Huang Y, Zhong X, Cao H, Liu B, Lin Y, et al. Gel polymer electrolyte with high performances based on pure natural polymer matrix of potato starch composite lignocellulose. Electrochim Acta. 2017;245:981–92. doi:10.1016/j.electacta.2017.05.176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Clarkson CM, El Awad Azrak SM, Forti ES, Schueneman GT, Moon RJ, Youngblood JP. Recent developments in cellulose nanomaterial composites. Adv Mater. 2021;33(28):e2000718. doi:10.1002/adma.202000718. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

29. Lou C, Zhou Y, Yan A, Liu Y. Extraction cellulose from corn-stalk taking advantage of pretreatment technology with immobilized enzyme. RSC Adv. 2022;12(2):1208–15. doi:10.1039/d1ra07513f. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

30. Yang H, Li S, Liu B, Chen Y, Xiao J, Dong Z, et al. Hemicellulose pyrolysis mechanism based on functional group evolutions by two-dimensional perturbation correlation infrared spectroscopy. Fuel. 2020;267:117302. doi:10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

31. Gou J, Liu W, Tang A. To improve the interfacial compatibility of cellulose-based gel polymer electrolytes: a cellulose/PEGDA double network-based gel membrane designed for lithium ion batteries. Appl Surf Sci. 2021;568:150963. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2021.150963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Diederichsen KM, McShane EJ, McCloskey BD. Promising routes to a high Li+ transference number electrolyte for lithium ion batteries. ACS Energy Lett. 2017;2(11):2563–75. doi:10.1021/acsenergylett.7b00792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Peng X, Zhang S, Xiang Y. Solvothermal synthesis of Cu2Zn(Sn1−x Gex)S4 and Cu2(Sn1−x Gex)S3 nanoparticles with tunable band gap energies. J Alloys Compd. 2015;640:75–81. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.03.248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF

Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools