Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Research Progress in the Preparation of MOF/Cellulose Composites and Their Applications in Fluorescent Detection, Adsorption, and Degradation of Pollutants in Wastewater

College of Materials Science and Engineering, Beihua University, Jilin, 132013, China

* Corresponding Author: Ming Zhang. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Sustainable Development and Multifunctional Application of Cellulose Composites)

Journal of Polymer Materials 2025, 42(4), 929-957. https://doi.org/10.32604/jpm.2025.074529

Received 13 October 2025; Accepted 25 November 2025; Issue published 26 December 2025

Abstract

Global water pollution is becoming increasingly serious, and compound pollutants such as heavy metals and organic dyes pose multidimensional threats to ecology and human health. Metal-organic skeleton compounds (MOFs) have been proven to be highly efficient in capturing a variety of pollutants by virtue of their large specific surface area, adjustable pore channels, and abundant active sites. However, the easy agglomeration of powders, the difficulty of recycling, and the poor long-term stability have limited their practical applications. Cellulose, as the most abundant renewable polymer in nature, has the characteristics of a three-dimensional network, mechanical flexibility, and easy surface functionalization, which can be synergized with MOF to construct “green composites”. The cellulose backbone inhibits the agglomeration of MOF particles and provides macro/mesoporous channels to significantly enhance the mass transfer rate. The hydroxyl and carboxyl groups from cellulose and its derivatives can be hydrogen-bonded or covalently bonded with MOF to enhance structural stability. Meantime, the composites can be woven, film-forming, and biodegradable to realize recovery and recycling. This paper describes the preparation method of MOF/cellulose composites, then focuses on the preparation style of MOF/cellulose composites, summarizes the applications of MOF/cellulose composites in the fields of adsorption and degradation of organic dyes, detection and adsorption of heavy metal ions, high toxicity anions, etc., and looks forward to the future development prospect of MOF/cellulose composites.Keywords

Global water pollution is becoming compounded and persistent [1]. Confronted with the realities of low-concentration, multi-category contaminants embedded in a highly complex environmental matrix, the current technology framework—centered on activated-carbon adsorption, chemical precipitation, and advanced oxidation—remains shackled by intrinsic drawbacks of poor selectivity and high energy expenditure, while simultaneously being prone to secondary pollution and intractable regeneration, thereby precluding the simultaneous fulfillment of the integrated imperatives of “high-efficiency removal, low cost, facile recyclability, and long-term sustainability” [2–4].

MOF is considered to be the most promising next-generation adsorbent material due to its ultra-high specific surface area, programmable pores, and functionalizable active sites [5]. However, the problems of easy agglomeration and difficult recycling of powdered MOF have seriously hindered its large-scale application. Nanocellulose (NC) is a nanoscale functional material derived from biomass materials processed by physical, chemical, or biological methods. As a special form of cellulose, it forms a microscopic feature and performance advantage that differs significantly from macroscopic cellulose [6]. Based on the differences in size, morphology, and preparation methods, NCs are mainly classified into three types: cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs), cellulose nanofibers (CNFs), and bacterial nanocellulose (BC) [7,8]. These materials not only inherit the excellent properties of cellulose but also possess excellent mechanical strength, structural flexibility, and high specific surface area [9–11]. By virtue of NC’s three-dimensional network, mechanical flexibility, easy surface modification, and fully renewable qualities, the composite system constructed with MOF is able to simultaneously solve the problems of crystal dispersion, mass transfer channels, and device molding, etc., with NC inhibiting the agglomeration of MOF particles and providing a macro-mesoporous fast transport network [12–14]. Its hydroxyl groups form hydrogen bonding or covalent bonding with MOF, which significantly enhances the structural stability and cycling life, and at the same time, endows the material with new functions of braidable, film-forming, and biodegradable [15,16]. The NC surface is rich in active hydroxyl groups, and more polar groups can be introduced by carboxylation, sulfonation, and other modifications, which can chelate with metal ions. After the addition of organic ligands, the metal ions and the ligands are assembled into MOFs on the NC surface through coordination. NC provides dispersed sites for MOF nucleation, which facilitates the maintenance of excellent MOF properties, and at the same time enhances the stress resistance of the composites through hydrogen bonding and physical entanglement to form a crosslinked network [17–19]. The composites can be used for wastewater purification, such as the NC membrane containing MOF can adsorb heavy metal ions and dye molecules with high efficiency, and the fiber structure of NC improves the mechanical properties and regeneration of the material, and maintains a stable adsorption efficiency after multiple cycles [20,21].

It is worth noting that the hydrogen bonding network formed between hydroxyl groups on the NC surface and water molecules can construct a “hydration buffer layer” at the periphery of the MOF pores, and the hydration layer can inhibit the non-specific deposition of pollutants on the outer surface of the MOF through competitive adsorption when the water content is low. When the water content is high, the water molecules shift from monolayer to cluster, the free volume increases, and the diffusion coefficient of pollutants increases by 1–2 orders of magnitude [22–24]. At the same time, the localized hydration micro-region at the MOF/NC interface can be used as a “fast transport channel”, accelerating the inward diffusion of heavy metals/dyes into the active sites of the MOF, thereby causing the transition of adsorption kinetics from surface confinement to intra-particle diffusion. Therefore, the hydrophilicity of cellulose not only enhances the material’s wettability but also becomes a key water-control switch to switch the adsorption kinetic mechanism of MOF-based composites by regulating the structure and dynamics of the interfacial hydration microregion [25–27].

To further enhance the dispersion and cycling performance of MOF in real matrices, studies have commonly loaded them onto functionalized cellulose: Carboxylated cellulose lends –COOH to chelate metal ions, promoting uniform nucleation of MOF and preferential capture of heavy metals; Aminated, sulfonated, phosphorylated, and quaternized cellulose introduce electrostatic, hydrogen-bonding, or ion-exchange sites via –NH2, –SO3H, –PO3H2, and –N+R3, respectively, to synchronously induce MOF anchoring and enhance the selectivity of anionic dyes, highly toxic oxo anions, and organic micropollutants, resulting in the construction of customizable composite adsorbent platforms of MOF/NC [28,29].

In this review, a systematic overview of the different methods currently used for the preparation of MOF/NC composites in different forms, such as hydrogels, membranes, and aerogels is presented, aiming to guide the selection of appropriate strategies for the preparation of various forms of MOF/NC composites, covering a variety of paths from cellulose pretreatment to MOF/NC composites. Then the exploration of this class of composites in water treatment applications, including e.g., adsorption of heavy metal ions, organic dyes, highly toxic anions, and antibiotics, is discussed (Fig. 1). Finally, the main bottlenecks and challenges in the current research are summarized, and the future development direction is proposed in the hope of providing reference and inspiration for the subsequent research.

Figure 1: Multifunctional applications of MOF/NC composites with various structures

2 Structure and Properties of Cellulose and Metal-Organic Backbone Compounds

2.1 Cellulose Structure and Properties

Cellulose, the most abundant renewable biomass resource on earth, is formed from β-D-glucopyranose linked by 1,4-glycosidic bonds in a chair-type conformation [30,31]. Nanocellulose with dimensions less than 100 nm in one dimension, which is generally prepared by degrading cellulose-rich biomass resources such as cotton, wood, straw and algae, has always been the focus of attention [32].

The second, third, and sixth carbon positions in the cellulose molecular structure contain three active hydroxyl groups, which form strong hydrogen bonds between cellulose molecules and within the molecules themselves. The presence of strong hydrogen bonds makes it difficult to isolate the nano-units within the cellulose molecule to prepare nanocellulose [33]. Simultaneously, strategies such as grafting hydrophobic silanes, crosslinking with glutaraldehyde or citric acid, depositing inorganic “armor” on the surface, and ion-liquid recrystallization significantly reduce mass loss in strong acid or strong alkali wastewater, maintaining long-term framework strength [34–36]. Its rich surface chemistry simplifies the synthesis of nanocellulose-based composites, while its high stiffness and strength make it a popular choice for composite reinforcement. The resulting nanocellulose composites or nanopapers are transparent, lightweight, and flexible, capable of long-term stable operation in extreme pH environments [37,38].

2.2 Structures and Properties of Metal-Organic Skeleton Compounds

Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs) are a class of crystalline porous materials formed by self-assembly of metal ions/clusters (e.g., Zn2+, Cu2+, Zr4+, etc.) with organic ligands (imidazoles, aromatic polycarboxylic acids, etc.) through ligand bonding to self-assemble to form crystalline porous materials. The crystalline porous materials have the advantages of metal active sites of inorganic components and the structural tunability of organic components, and possess regular pore channels, large specific surface area, and controllable pore volume, which can be modified to realize the customization of chemical functions and provide the basis for pollutant targeting [39,40]. At present, the green synthesis, precise post-modification, and functional design of MOFs have become hotspots at the intersection of materials science and environmental chemistry, with remarkable potential in the field of wastewater pollutant removal.

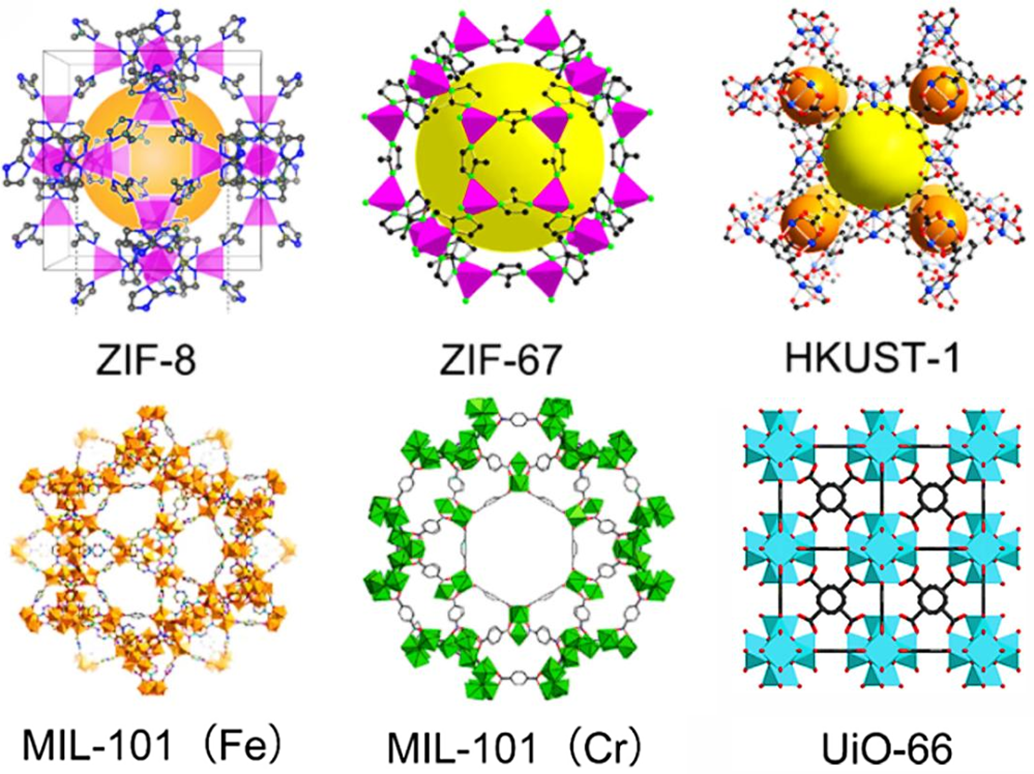

In recent years, MOFs have shown outstanding performance in fluorescence detection of wastewater pollutants, adsorption of heavy metals, and degradation of organic pollutants due to their tunable pore channels, abundant active sites, and excellent optical/adsorption properties [41]. Based on the metal centers, ligands and topologies, the core characteristics and potential for environmental applications of the classical series are as follows (Fig. 2): ZIFs (Zeolitic Imidazolate Frameworks), centered on Zn2+, Co2+, and imidazolium ligand coordination, with excellent water stability and chemical inertness, are suitable for the adsorption of small and medium-sized molecular pollutants in wastewater (e.g., antibiotics, heavy metal ions); HKUST (Hong Kong University of Science and Technology), Cu2+-centered aromatic polycarboxylic acid ligands with high specific surface area and unsaturated Cu2+ active sites, which can adsorb heavy metal ions (e.g., Pb2+, Cd2+) and enable fluorescence detection; MILs (Materials Institute of Lavoisier), centered on Al3+, Cr3+, aromatic polycarboxylic acid ligands with good water stability and multivalent metal centers that catalytically activate oxidants (e.g., H2O2) are widely used for the degradation of organic pollutants (e.g., dyes, phenols); UiOs (University of Oslo series), centered on Zr4+, aromatic carboxylic acid ligands, are chemically and thermally very stable, and ligand functionalization (e.g., introduction of amino groups) enhances pollutant-targeted adsorption and fluorescence response, making them a preferred matrix for MOF/cellulose composites [42–45]. The structural diversity and functional tunability of the above MOFs provide interface design space for their composites with cellulose, and also lay the foundation for the application of composites in wastewater pollutant treatment through mechanisms such as pore sieving and active site coordination.

Figure 2: Typical MOFs [9]. Copyright © 2025 Wiley-VCH GmbH

The water/acid/base stability of MOFs is determined by the metal-ligand bond strength in conjunction with the ligand protonation/deprotonation tendency: high-valent stearic acid nodes form high-bond energy oxygen clusters with carboxylic acid ligands, which significantly inhibit hydrolysis in water and acidic media; imidazole/pyrazole-MOFs are intrinsically base-stable due to the inertness of the M–N bond to OH– and are intrinsically base-stabilized. Through node design, ligand fluorination, and surface coating, the pH window of stabilization can be expanded from the neutral range to the extreme conditions of strong acids and bases, and long-term crystal and pore structure preservation can be achieved under the environments of concentrated HCl or concentrated NaOH [46–48].

In terms of pollutant selectivity, different MOF series exhibit significantly different “molecular recognition” capabilities for heavy metal ions, organic dyes, highly toxic anions, and antibiotics by virtue of differences in pore size, metal nodes, and surface functional groups. Among them, structural differences endow MOFs with molecular recognition functions: UiO-66-NH2 with Zr4+ open site efficiently traps Pb2+/Cd2+; MIL-101-SO3H exclusively removes Hg2+ with sulfonate electrostatic groups; ZIF-8 sieves methylene blue and blocks Congo red with a 0.34 nm pore window and enriches tetracycline by a hydrophobic cavity; and UiO-66-(OH)2 is protonated and ion-paired with highly toxic Cr2O72– to achieve precise separation of heavy metals-dyes-anions-antibiotics [46,49,50].

3 Preparation of MOF/NC Composites

MOF/NC composite strategies can be categorized into in situ and non-in situ growth [51]. The in situ growth strategy is based on the core feature of “fiber-first”, i.e., a nanocellulose substrate is prepared first, and then the active sites or pore structures on the surface of the nanocellulose are used to induce the in situ growth of MOFs on the surface or in the interior of the nanocellulose. This strategy can realize the tight binding of MOF and nanocellulose substrate and the regulation of loading position, and the prepared composites are suitable for scenarios with high requirements on the strength of interfacial interaction and the utilization rate of active sites due to the full exposure of MOF active sites [52]. In contrast, the non-in situ binding strategy does not rely on the in situ synthesis of MOF on the nanocellulose substrate, but rather realizes the composite of MOF and fibers through predefined interfacial interactions for the preferential embedding of MOF, i.e., pre-dispersing the MOF in a suspension of polymers such as nanocellulose first, and then embedding the MOF in the nanocellulose body through the processes of spinning, gelation, and so on. This approach gives the overall performance of nanocellulose, and the agglomeration of MOF needs to be solved by dispersant modulation or morphology optimization [53–55]. In practice, it is necessary to combine the structural stability of MOF, the characteristics of the nanocellulose substrate, and the demand for material properties in the target application to realize the directional design of the composite system and performance modulation [56,57].

In scenarios where long-term mechanical integrity (resistance to fatigue, peeling, and moisture swelling) is pursued, the in-situ growth strategy should be prioritized. This strategy significantly enhances the interfacial bonding energy through the crystal-fiber interpenetration network with chemically anchored nodes to satisfy the stringent requirements of high mechanical strength, flexibility, and long-term stability. On the contrary, if the goal is to achieve high loading and maintain the intrinsic crystal structure of MOF while avoiding the potential damage to the MOF structure by high-temperature and high-pressure synthesis conditions, the non-in situ embedding strategy is more suitable. This strategy can compensate for the loss of mechanical properties through subsequent cross-linking, oriented spinning, or interfacial capacitance enhancement to achieve rapid preparation and preservation of the original morphology. In summary, the in-situ growth strategy is preferred for “strong interface and high durability” scenarios, while the non-in-situ embedding strategy is appropriate for “high load and crystal preservation” scenarios. The two can realize a directional trade-off in the performance-load-stability triangle, providing precise MOF/NC composite solutions for different application scenarios [58–60].

During in situ growth, hydroxyl (–OH) or carboxyl (–COOH) groups on the surface of cellulose and its derivatives first form a pre-coordination layer with metal ions. The local supersaturation is nearly two orders of magnitude higher than in non-external systems, reducing nucleation activation energy. Crystals undergo rapid burst nucleation, achieving sizes of only 50–80 nm. The high nucleation rate introduces numerous unsaturated metal sites and lattice distortions, resulting in a defect density significantly higher than in non-in situ systems. This increases active sites and enhances adsorption capacity, but the defect openings weaken sieving precision, causing the separation factor α to decrease by approximately 20% [61,62]. The non-in-situ route, where MOFs are pre-crystallized, undergoes diffusion-controlled composite formation. Grains grow to 200–500 nm with intact lattices, regular pore windows, and minimal defects, preserving intrinsic sieving properties. While exhibiting slightly lower capacity, it achieves higher selectivity, thus establishing a performance trade-off between “rapid nucleation-multiple defects-high capacity” and “slow growth-few defects-high selectivity” [63].

The in situ growth strategy has been widely adopted because it can achieve the regulation of crystal size and loading with the help of cellulose-directed induced MOF nucleation [64]. The typical process is as follows: firstly, a cellulose substrate is prepared to obtain a fibrous material with surface active sites or pore structure; then the cellulose substrate is pretreated by introducing hydroxyl groups and amino groups through chemical modification or by physical treatment, such as plasma treatment, to enhance the surface reactivity and to provide attachment sites for MOF growth. Subsequently, the MOF precursor solution was configured, and the metal ions and organic ligands were mixed proportionally, and parameters such as concentration and pH were regulated [65,66]. Finally, the pretreated cellulose substrate was immersed in the precursor solution, and the metal ions and ligands were allowed to undergo coordination reactions on the fiber surface or in the pores by solvent heat, hydrothermal heat, or room-temperature standing to grow in situ to form MOF crystals, and the composite products were obtained after washing and drying [67].

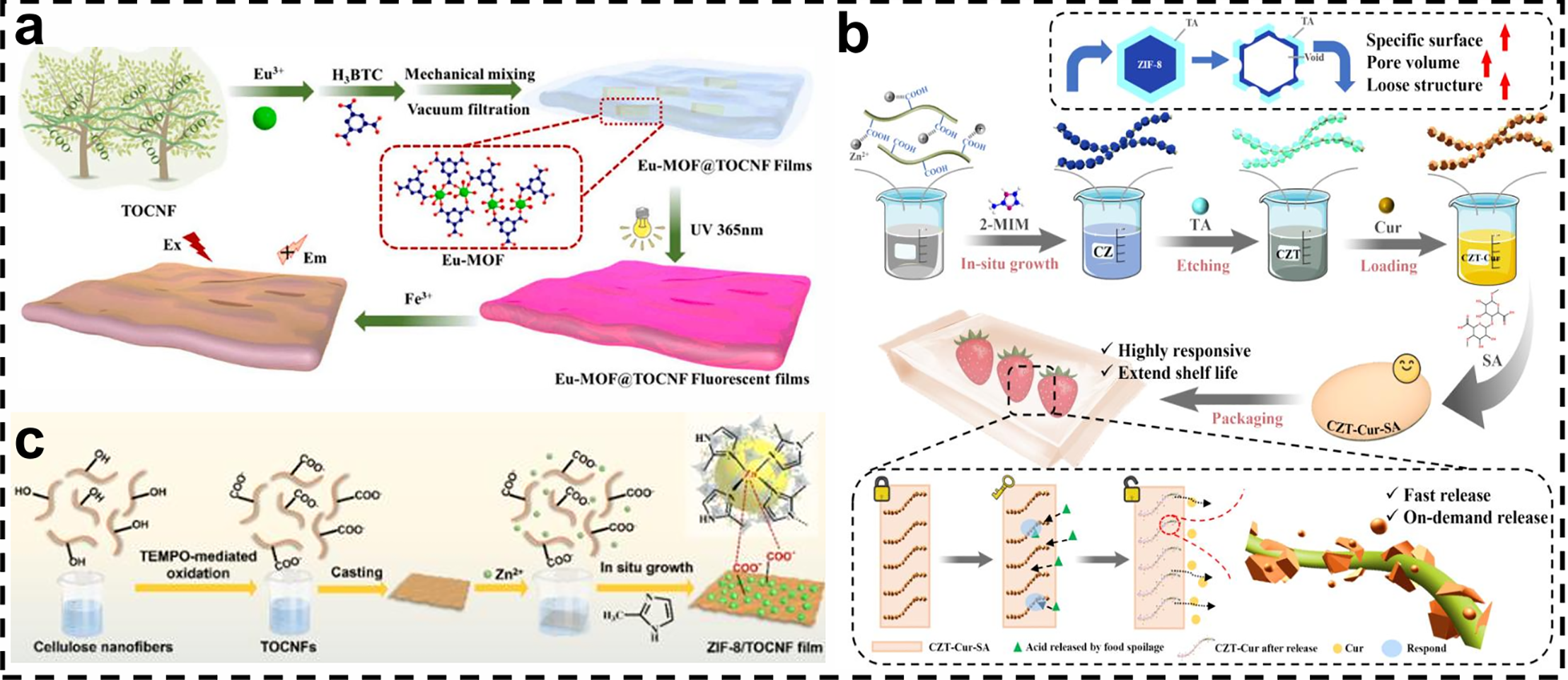

Wang et al. prepared Eu-MOF@TOCNF fluorescent films by assembling Eu-MOF on the surface of TEMPO-oxidized cellulose as a substrate by the in-situ growth method (Fig. 3a) [68]. Fig. 3b explains the direct construction of hollow defects ZIF-8 on TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibrils by Xu et al. using a “one-step in situ growth-tannic acid etching” strategy [69]. As shown in Fig. 3c, Min et al. prepared a pH/enzyme-responsive CAR@ZIF-8/TOCNF/Pec composite membrane by the in situ growth method. The membrane was first oxidized by TEMPO, then ZIF-8 nanoparticles were grown in situ on the membrane surface and loaded with cinnamaldehyde (CAR), and finally, the composite membrane was formed by electrostatically adsorbing pectin as a “gatekeeper” [70].

Figure 3: (a) Schematic diagram of the preparation process of Eu-MOF@TOCNF fluorescent films [68]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [68]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6116920311143). (b) Preparation of CZT-Cur-SA composite film [69]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [69]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6116920086212). (c) Preparation process and in-situ growth of ZIF-8 nanoparticles [70]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [70]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6116920471290)

The non-in situ growth route, in which MOF nanocrystals are first synthesized independently and then homogeneously anchored to the formed cellulose backbone, circumvents the stringent requirements of in situ synthesis for solvent resistance and thermal stability of the substrate [71]. To obtain highly dispersed, low-agglomeration MOF particles, it is necessary to construct a fiber gel network that can be subsequently crosslinked. Firstly, the solution precursor is prepared, and the substance that can form the gel network is mixed with the solvent, and a stable solution system is formed through hydrolysis and condensation reactions. Then the MOF particles are uniformly dispersed into the solution, which can be achieved by ultrasonication and stirring to avoid agglomeration and make the MOF in full contact with the solution [72–74]. Subsequently, the solution-to-gel transition is promoted, and the colloidal particles in the sol are allowed to gradually cross-link to form a three-dimensional network structure by adjusting the temperature, humidity, or adding a catalyst, so that the MOF is encapsulated in the gel matrix. Finally, drying and post-treatment were carried out to remove solvents from the system by low-temperature drying to avoid structural collapse, and heat treatment was carried out to further strengthen the bonding of the gel network with the MOFs, if necessary, to ultimately obtain composites with uniformly dispersed MOFs [75,76].

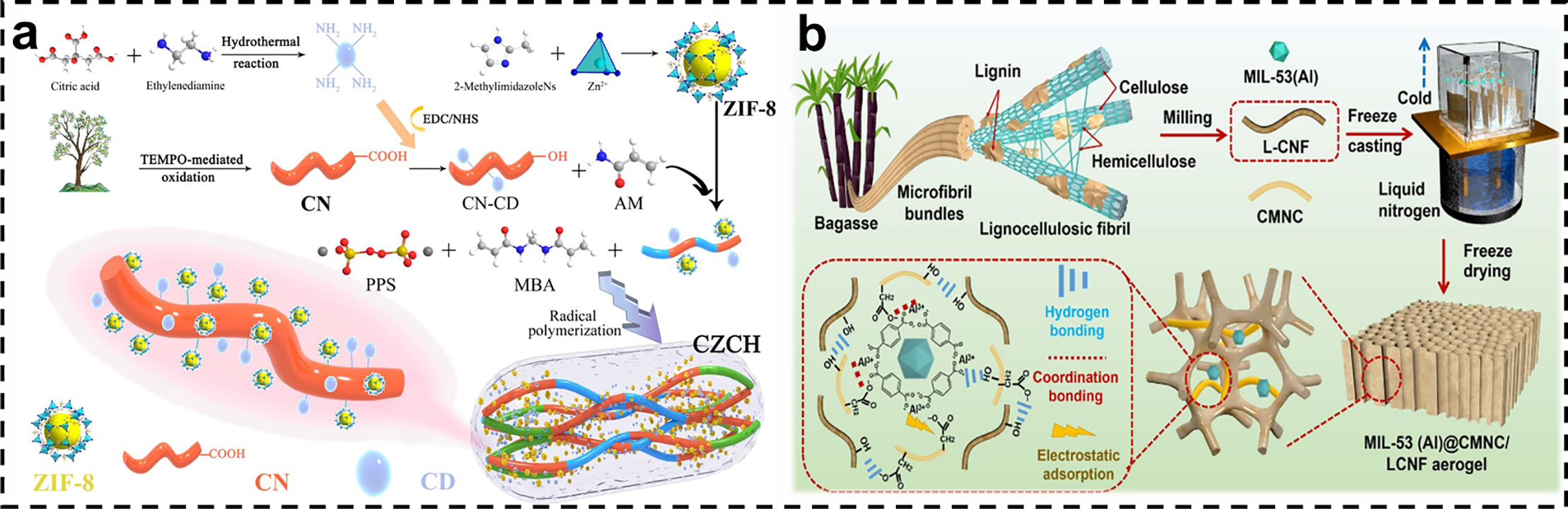

Zhang et al. synthesized a novel cellulose nanofiber-modified carbon-dot grafted polyacrylamide/ZIF-8 composite hydrogel for the simultaneous adsorption and detection of tetracycline (TC) in order to solve the problem of antibiotic contamination in water resources, as shown in Fig. 4a. The hydrogel had a 3D porous structure and successfully integrated NC, CD (carbon dots), and ZIF-8 [77]. Fig. 4b visualizes that Li et al. used carboxymethylated nanocellulose as a “molecular bridge” to anchor MIL-53(Al) nanoparticles to lignocellulosic nanofibers, which were then unidirectionally freeze-cast to obtain the final aerogel [78].

Figure 4: (a) Synthesis route of CZCH [77]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [77]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6116920734924). (b) Schematic of the preparation process of MIL-53(Al)@CMNC/LCNF aerogel (M@CLA) [78]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [78]. Copyright 2024, Springer Nature and Copyright clearance, License number (6118130794811)

4 Diversified Morphology Construction of MOF/NC Composites

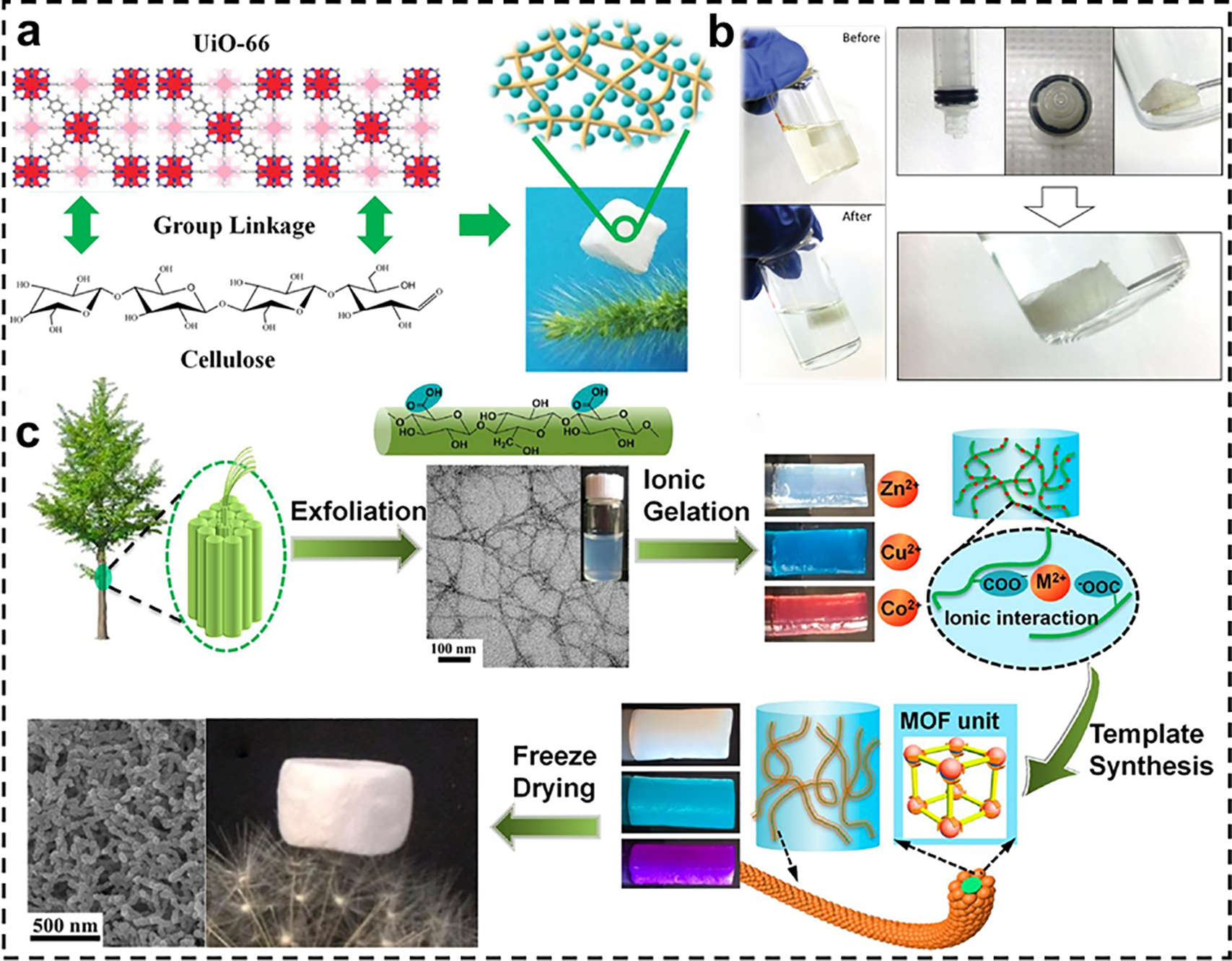

In recent years, aerogels, as a material with ultra-low density and high porosity, have attracted much attention due to their great potential in the field of adsorption and separation [79]. Combining cellulose and MOF to prepare composite aerogels can not only leverage the advantages of both but also further enhance the adsorption performance of the materials through synergistic effects. Wang et al. used a “self-crosslinking-freeze-drying” strategy to prepare UiO-66/CNF composite aerogels (Fig. 5a), in which pre-synthesized UiO-66 powders were directly added to a suspension of CNF, homogeneously mixed, and freeze-dried [80]. Zhu et al. prepared flexible porous hybridized aerogels containing up to 50 wt% of MOF (ZIF-8/UiO-66/MIL-100(Fe)) by aqueous sol-gel reaction of aldehyde-modified CNC with hydrazide-modified carboxymethylcellulose (NHNH2-CMC) and freeze-drying (Fig. 5b) [13]. Zhu et al. used TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers as a template to grow ZIF-8 crystals on the surface of CNF via “in situ synthesis and freeze-drying”, producing a fibrous ZIF-8/CNF composite aerogel (Fig. 5c). The size of the ZIF-8 crystals was effectively regulated by the fiber skeleton of CNF and the synergistic effect of ion/hydrogen bonding [57].

Figure 5: (a) Preparation process of MOF/NC aerogels and photographs of lightweight MOF/NC [80]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [80]. Copyright 2019, Elsevier and Copyright Clearance, License number (6116930143091). (b) Schematic diagram of MOF-cellulose hybridized aerogels [13]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [13]. Copyright 2016, John Wiley and Sons, and Copyright Clearance, License number (6118050849337). (c) Schematic diagram of the preparation of fibrous MOF aerogels using CNFs as a template [57]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [57]. Copyright 2018, American Chemical Society, and Copyright Clearance, License number (6118060332262)

Hydrogels are of interest due to their unique physicochemical properties. Hydrogels have high water absorption, good flexibility, and these properties make them excellent for adsorption and separation applications [81]. When cellulose is combined with MOF to prepare composite hydrogels, this material exhibits a unique set of advantages. Cellulose provides the hydrogel with good biocompatibility and mechanical properties. Its abundant hydroxyl functional groups can form coordination bonds with the metal centers of MOF, enhancing the stability and interfacial compatibility of the composite [82,83]. The presence of cellulose also improves the flexibility and processability of hydrogels, making them more suitable for practical water treatment applications [84].

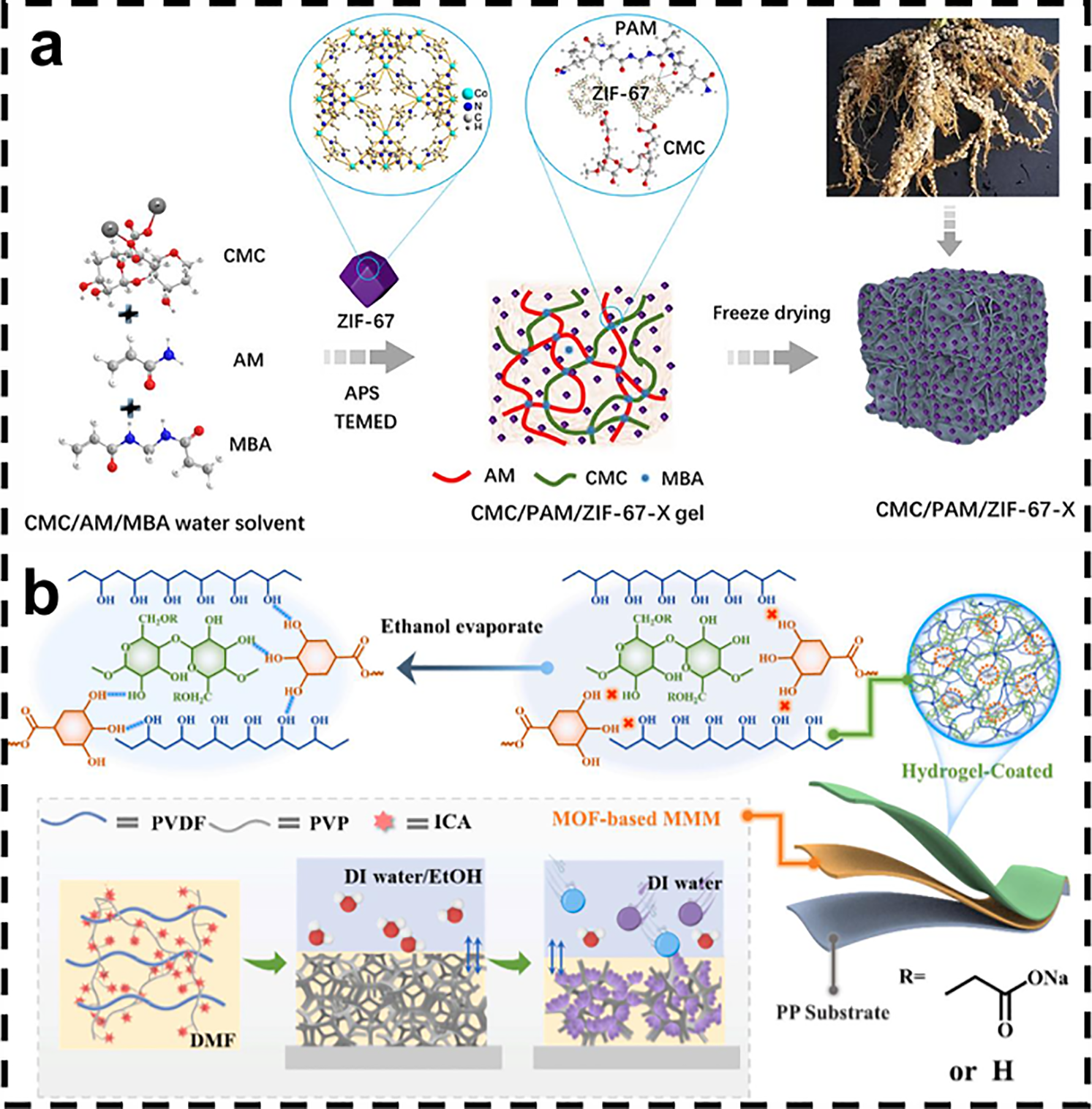

Yang et al. proposed a “network repair-post-polymerization” strategy to implant ZIF-67 into carboxymethyl cellulose/polyacrylamide dual-network hydrogels in situ, taking into account the symbiotic mechanism of rhizobium-legume (Fig. 6a). The carboxyl and amino groups on the surface of the hydrogel drove the uniform growth of ZIF-67 and its directional arrangement along the channels, which eliminated MOF aggregation and enhanced the interfacial compatibility. The resulting hydrogels have low density and through pores [85].

Figure 6: (a) Synthesis line of CMC/PAM/ZIF-67-X [85]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [85]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118070324468). (b) Preparation process and formation mechanism of PMM [86]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [86]. Copyright 2020, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118070609453)

Lu et al. used a polypropylene nonwoven fabric as a substrate, and PMM membranes (PVDF-supported MOF composite membranes) were produced by growing Cu/Zn bimetallic MOFs in situ in a PVDF (polyvinylidene fluoride skeleton backbone, which was used as the base of the polypropylene nonwoven fabric. Subsequently, the polyvinyl alcohol/carboxymethyl cellulose/tannic acid bilayer network was uniformly coated on the film surface using the “hydrogel coating” method in which ethanol reversibly inhibits hydrogen bonding (Fig. 6b), and the hydrogen bonding was reestablished upon the volatilization of ethanol, resulting in the formation of a dense hydrated layer [86].

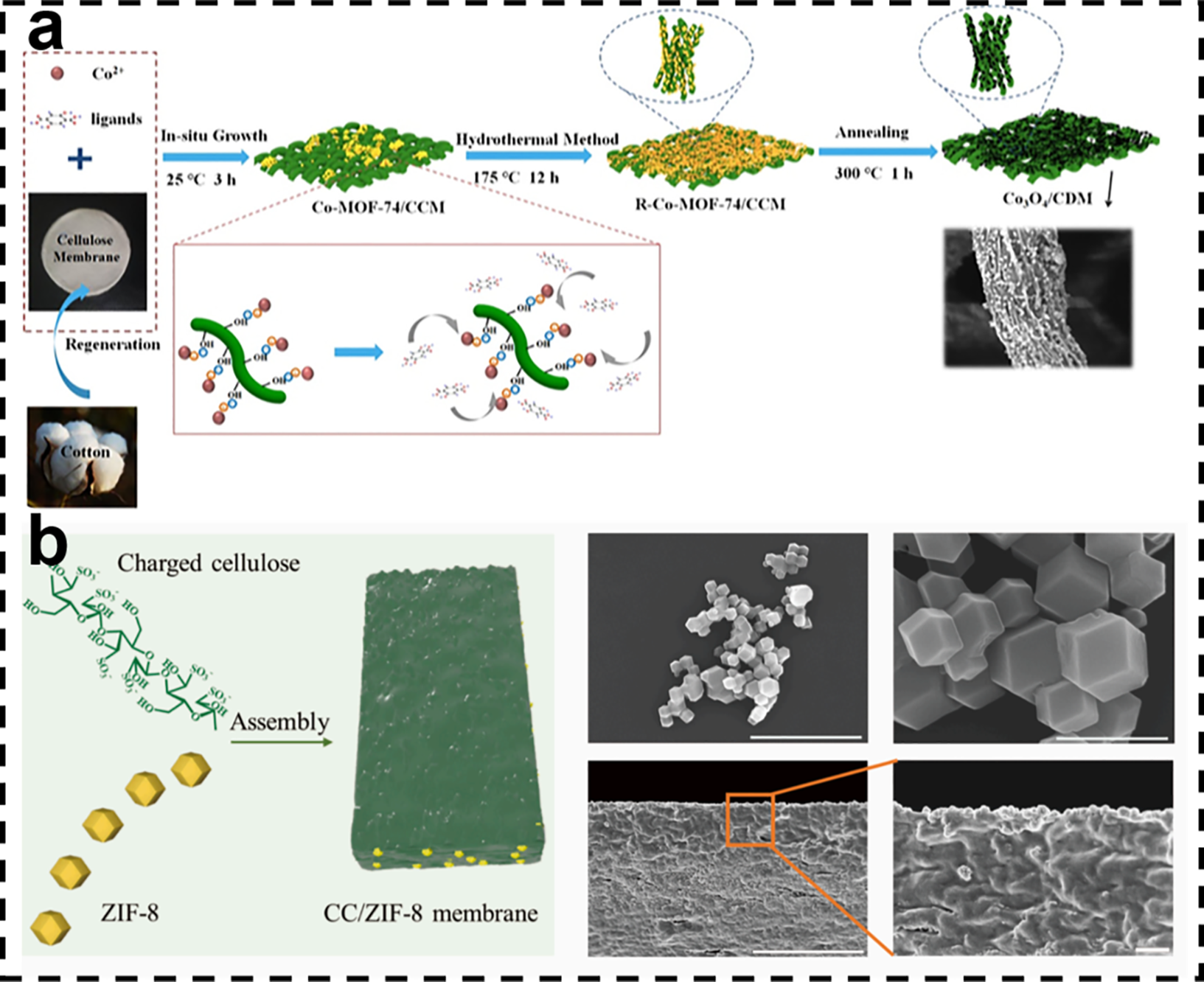

Membranes are favored for their efficient separation performance, ease of operation, and ability to achieve continuous treatment [87]. Membrane materials are usually selectively permeable and can effectively separate contaminants in water, including dissolved organic matter and heavy metal ions [88]. However, conventional membrane materials face several challenges in practical applications, such as membrane contamination, low flux, and insufficient selectivity. To address these issues, researchers have begun to explore new methods to prepare composite membranes by combining cellulose and metal-organic frameworks. Fig. 7a explains the conversion of Co-MOF-74 into Co3O4 nanoparticles by Hou et al. via in situ assembly and high-temperature calcination, anchoring them to a regenerated cellulose 3D network [89]. In Fig. 7b, Shi et al. “strung” charged cellulose molecules with ZIF-8 microcrystals to construct flexible self-supporting membranes with both high negative charge and sub-nanometer/nanopore channels [90].

Figure 7: (a) Schematic diagram of synthesis [89]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [89]. Copyright 2021, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118070794155). (b) Schematic diagram of nanofluid membrane, microstructure of ZIF-8, and microstructure of nanofluid membrane [90]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [90]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118071137512)

The combination of cellulose and metal-organic frameworks is not only limited to aerogels, hydrogels, and membranes, but can also be used in a variety of other morphologies for efficient pollutant adsorption and separation. These morphologies include composite fibers, coatings, etc., each with unique structural and performance advantages [91]. For example, composite fibers combine the mechanical strength of cellulose with the high adsorption properties of MOF, enabling them to be woven into filters or filled into filter columns for treating high water flows. Composites in coated form can be coated on a variety of substrates, such as membranes, fabrics, or pipe linings, to provide an additional adsorption layer and enhance water treatment [58]. These diverse morphologies offer a wider range of possibilities for the application of cellulose and MOF in water treatment.

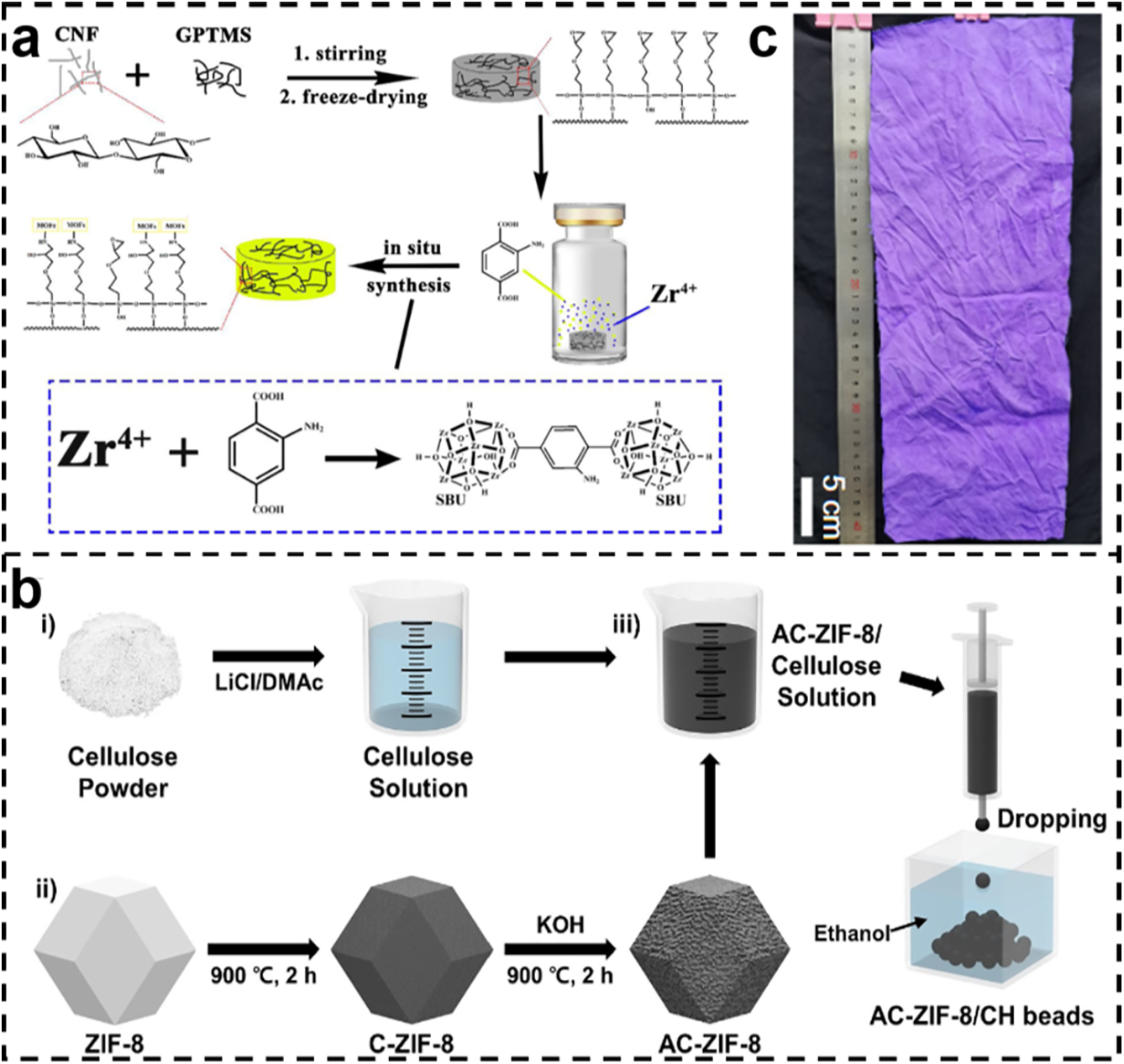

Shen et al. used γ-glycidyl ether oxypropyltrimethoxysilane as a coupling bridge for the in situ growth of UiO-66-NH2 on a cellulose sponge backbone (Fig. 8a). The epoxy group of GPTMS (3-chloropropyltrimethoxysilane) was covalently bonded to MOF to achieve high interfacial stability [92]. Lee et al. prepared porous cellulose hydrogel beads in one step by a “dissolution-regeneration” strategy. ZIF-8 was carbonized-activated and then co-extruded with cellulose solution into an ethanol bath to obtain homogeneous spherical beads, which could be directly enlarged (Fig. 8b). The beads were both micro-mediated-macro hierarchical pores with a maximum adsorption capacity of 565.1 mg/g for rhodamine B. They provide a high-capacity and recoverable green bead adsorption platform for the treatment of dye wastewater on a large scale [93]. Li et al. directly prepared the whole cotton blank fabric into a continuous ZIF-67 functional fabric by a “two-step impregnation-roll-to-roll” process, in which a uniform and dense ZIF-67 coating was grown in situ on the surface of each fiber (Fig. 8c). Without weaving or post-finishing, the whole roll of fabric is turned into a cut-and-sew continuous textile material with MOF functional layers in one go [94].

Figure 8: (a) Schematic of the preparation of UiO-66-NH2-loaded cellulose sponges [92]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [92]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118071363474). (b) Schematic of the fabrication of AC-ZIF-8/CH bead particles [93]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [93]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118080044056). (c) Photographs of ZIF-67-CT [94]. Copyright © 2024 Springer Nature

Based on the diverse forms of aerogels, hydrogels, membranes, and beads mentioned above, from a preparation perspective, aerogels continue to follow the “self-crosslinking-freeze-drying” route. They feature low density and high porosity, making them suitable for bulk molding. However, the bulk material is highly brittle and requires external encapsulation to prevent crumbling [80]. Hydrogels gain flexibility through “network repair-post-polymerization,” enabling injection molding or coating with strong adhesion to substrates. However, their strength decreases upon swelling, and repeated drying often leads to cracking [85]. Membrane structures leverage “in-situ growth-phase inversion” to balance continuous operation with high permeability, allowing direct integration into existing membrane modules [90]. Yet, MOF loading capacity remains constrained by the pore size-thickness trade-off. Beads/sponges employ “dissolution-regeneration” or two-step impregnation processes. Their graded pore structure facilitates diffusion and column filling, though extrusion-solidification or template calcination steps increase solvent recovery and energy consumption burdens. Overall, all forms possess viable pathways for large-scale upscaling, yet further optimization is required in engineering details such as molding efficiency and mechanical robustness [95].

5.1 Detection and Adsorption of Heavy Metal Ions

In the field of heavy metal ion adsorption, composites combining cellulose and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) show significant advantages. Cellulose acts as a three-dimensional “ligament” to inhibit MOF agglomeration and stabilize the pore channels. By designing specific combinations of organic ligands and metal ions, adsorbent materials with high selectivity for heavy metal ions can be prepared. These properties make cellulose-based MOF composites promising for heavy metal ion adsorption [96–98].

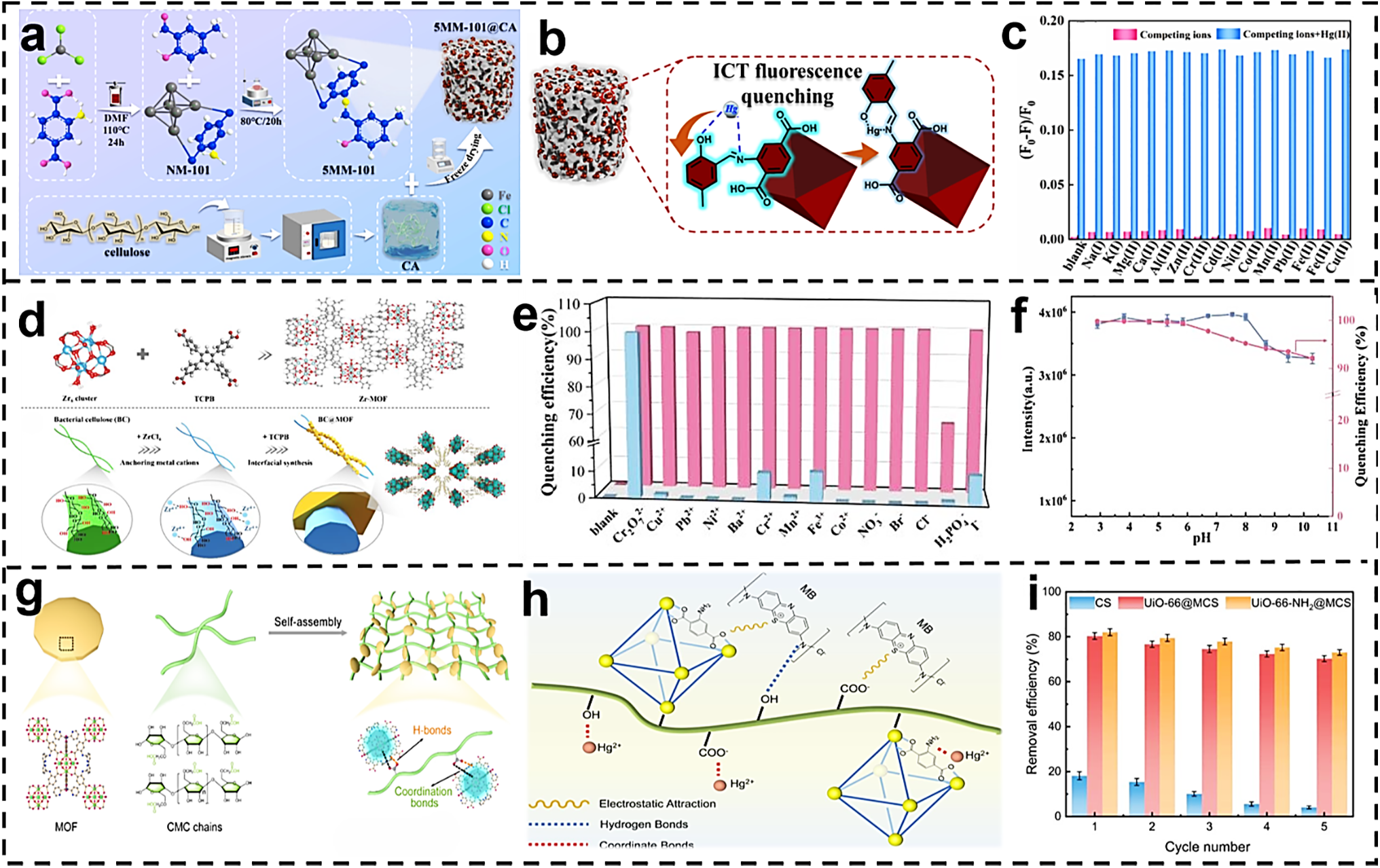

Li et al. employed a “freeze-drying-post-modification” tandem strategy. As shown in Fig. 9a, this aerogel utilizes cellulose as its fundamental structural unit. Through physical embedding, NH2-MIL-101(Fe) is immobilized on the pore walls, forming a “shell-core” architecture that simultaneously possesses luminescent sites and adsorption sites. The detection limit (LOD) of this aerogel for Hg2+ is as low as 6.89 × 10−8 mol/L, with a maximum adsorption capacity of 409.84 mg/g, 2.1 times that of commercially available sulfur-based activated carbon. In experimental samples, 90% of the adsorbate originates from cellulose. The synthesis process operates at low temperatures without requiring high-temperature vulcanization, maintaining high adsorption capacity after five cycles. It incorporates built-in real-time fluorescence monitoring capability, outperforming traditional sulfur-based activated carbon with solely adsorption functionality. After 5 cycles, the treatment capacity remained stable at 240 mg/g. SEM images in the literature revealed that the MOF structure remained largely intact after 5 cycles, with only minor damage observed. The mechanism shown in Fig. 9b involves the formation of a six-membered ring complex between Hg(II) and Schiff base N, O, with ICT inducing a 20 nm red shift in the absorption peak. XPS measurements reveal shifts in N1s and O1s binding energies by 0.17 and 0.27 eV, respectively, alongside a 4.24 eV Hg4f splitting, confirming metal-ligand charge transfer. Concurrent skeletal planar distortion weakens π-stacking interactions, enhancing nonradiative transition efficiency by a factor of 15. Fluorescence intensity exhibits linear decay within the 0.5–2.5 μM concentration range. As shown in Fig. 9c, a series of metal ions was introduced to investigate their potential interference effects on the Hg(II) response signal. The results indicate that the fluorescence response of the experimental samples to Hg(II) is not hindered by the presence of other metal ions [99].

Figure 9: (a) Synthesis route of 5MM-101@CA cellulose aerogel [99]. (b) Hypothetical fluorescence sensing mechanism [99]. (c) Effect of interfering metal ions on the 5MM-101 sensor for Hg(II) [99]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [99]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118090259443). (d) Preparation of Zr-MOF used for in situ growth of BC [100]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [100]. (e) Fluorescence intensity change curve of BC@Zr-MOF in the presence of the selected ion (blue) and Cr2O72− after adding competitive metal ions (5-fold excess, red) to the solution [100]. (f) Changes at different pH values. Reprinted with permission from Reference [100]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118090413761). (g) Schematic of the preparation process of CMC-MOF membranes [101]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [101]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118090544773). (h) Adsorption mechanism of Hg2+ on UiO-66-NH2@MCS composites [102]. (i) Hg2+ removal efficiency of original CS and MOFs@MCS composites after different regeneration cycles [102]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [102]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118090668382)

Fig. 9d demonstrates the growth of a Zr-MOF with aggregation-induced luminescence properties on the surface of bacterial cellulose (BC) backbone by Jiang et al. using an in-situ growth strategy, resulting in a BC@Zr-MOF fluorescent composite membrane. Compared with MOF grains, the fiber network not only showed a significant increase in specific surface area, but also a higher fluorescence quantum yield and a significantly widened acid-base tolerance window. The aqueous system showed a specific recognition and adsorption behavior for Cr2O72– with an adsorption amount of 90 mg/g. When used in combination with recirculation filtration, the LOD can be further reduced to 6.9 nM due to the adsorption-enrichment effect. By adding other competitive ions (at fivefold excess) to the solution of the BC@Zr-MOF/Cr2O72− complex, the competitive ions showed negligible interference with Cr2O72− detection (Fig. 9e). Due to its stable crystal structure, BC@Zr-MOF maintains high quenching efficiency (above 90%) across the pH range of 2–11 (Fig. 9f) [100].

Chang et al. developed a fluorescent sensing membrane based on carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) (Fig. 9g) for on-site detection of trace Cr(VI) in groundwater. By combining CMC with MOFs via vacuum-assisted filtration, they created a membrane material with high sensitivity and selectivity, achieving a detection limit as low as 3.72 ppb—significantly below the WHO standard of 50 ppb. The water-phase adsorption energy calculated by DFT decreased by only 0.23 eV, remaining within the weak interaction range. The XPS peak shift was less than 0.2 eV, lacking quantitative evidence for charge transfer. Visible nanogaps between particles and substrate in SEM images indicate limited interface adhesion. Therefore, the term “thermodynamically stable” refers more to a kinetically frozen metastable state than to an equilibrium system with fully minimized interfacial energy [101].

Yang et al. produced a series of MOFs@MCS porous composites by using modified cellulose sponge (MCS) as a carrier, firstly utilizing the hydroxyl group-rich anchoring Zr4+ on its surface, and then enabling the growth of UiO-66-NH2 crystals. Adsorption experiments showed that the amino-functionalized UiO-66-NH2@MCS had a saturation capacity of 224.5 mg/g for Hg2+, and the adsorption mechanism is shown in Fig. 9h. The adsorption of Hg2+ by MOFs@MCS is dominated by coordination complexation, in which the carboxyl groups on the surface of the composites form a stable monodentate/dipartite coordination bond with Hg2+, and the additional amino groups in UiO-66-NH2@MCS further provide electron pairing for chelating with Hg2+ to generate a more stable N–Hg coordination structure. This strategy couples the coordination activity of MOF with the mechanical flexibility of cellulose sponges, providing a scalable molding solution for continuous flow purification of complex wastewater. As shown in Fig. 9i, Hg2+ was efficiently desorbed by immersion in dilute HNO3 at pH = 2, with removal rates remaining at 70%–80% after five cycles; XPS and SEM results indicate that the characteristic peaks and morphology of UiO-66-NH2 remain essentially unchanged, preliminarily confirming the stability of the carboxyl/amino ligands during desorption and no significant collapse of the Zr–O framework [102].

In heavy metal treatment scenarios, different platform morphologies demonstrate distinct advantages, Collectively, these formats demonstrate superior potential over traditional granular activated carbon or standalone MOF powders in terms of capacity, sensitivity, cycle life, and operational convenience, offering diverse and efficient solutions for heavy metal remediation. However, quantitative data on costs, energy consumption, and additional recycling cycles are currently lacking, and the permanent inactivation rate caused by salt or complexes has not been estimated. Subsequent work should supplement the aqueous phase LCA and TEA, adopt low-eutectic solvents or mechanochemical methods to reduce energy consumption, and design an enzymatic hydrolysis-precipitation metal recovery-cellulose route to achieve a closed-loop economic-environmental dual-account system [103,104].

5.2 Detection and Adsorption of Highly Toxic Anions

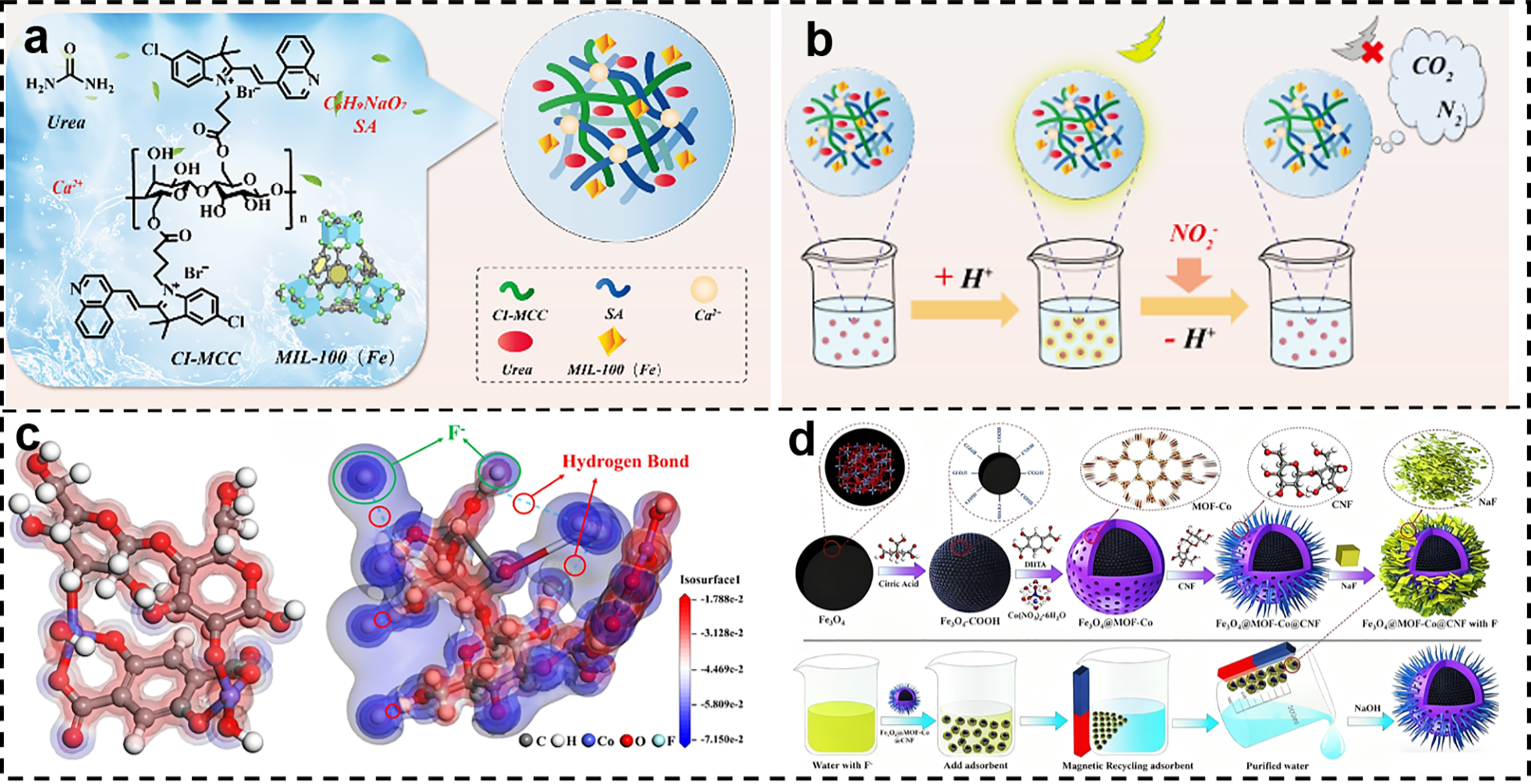

MOF/NC composites, with their high capacity, high selectivity, and broad pH adaptability, have emerged as a key frontier for advanced purification of highly toxic anions. Their industrialization research will directly drive technological upgrades in synergistic treatment of highly toxic anions. Hao et al. designed and synthesized a multifunctional hydrogel capable of simultaneously achieving nitrite adsorption, removal, and fluorescence signal output within the same system. Its synthesis is illustrated in Fig. 10a. This gel utilizes a sodium alginate-microcrystalline cellulose dual-network framework as its backbone, incorporating MIL-100(Fe) particles to construct three-dimensional channels. pH-responsive fluorescent probes CI-MCC are uniformly anchored to the pore walls. This hydrogel exhibits a maximum NO2− removal efficiency of 99.8% at pH 1.0–2.0, with a linear fluorescence response range from pH 2.0 to 3.8, and overall applicability across pH 1.0–3.8. Fig. 10b illustrates the complete detection-removal pathway for NO2−: In acidic wastewater, urea rapidly undergoes a synergistic diazo-coupling reaction with NO2− accompanied by redox processes, achieving a removal rate of 99.8% within 15 min. The reaction consumes H+, causing a local pH increase that quenches CI-MCC fluorescence. The quenching intensity exhibits a linear relationship with NO2− concentration in the 0–5 mM range (R2 = 0.9914, LOD = 74 μM). DFT calculations further reveal that the CI-MCC protonated HOMO-LUMO energy gap decreases from 3.33 to 2.81 eV, confirming ICT enhancement and corresponding to a 18 nm red shift in fluorescence emission, providing evidence for the charge transfer pathway [105].

Figure 10: (a) Preparation of urea@MIL-100(Fe)/CI-MCC/SA hydrogel [105]. (b) NO2– removal and fluorescence monitoring process [105]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [105]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118090832812). (c) Electrostatic potential distributions of Fe3O4@MOF-Co and Fe3O4@MOF-Co@CNF vs. F– [106]. (d) Top. Mechanistic analysis of adsorbent synthesis and bottom. Mechanistic analysis of adsorption regeneration [106]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [106]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118091099829)

Zhou et al. designed and synthesized a magnetic metal-organic framework-derived material with a core-shell structure for the efficient removal of fluoride ions (F−) from fluoride-containing wastewater in mines (Fig. 10d. top). The adsorption capacity of this material increases initially and then decreases within the pH range of 2–12, with the optimal adsorption occurring at pH 7. Molecular dynamics simulations and electrostatic potential distribution analysis reveal that the adsorption of F− by this material primarily depends on the synergistic effects of ligand exchange and hydrogen bonding (Fig. 10c). Specifically, the abundant hydroxyl groups on the CNF surface can form a stable hydrogen-bond network with F− ions, while the unsaturated Co sites within the MOF-Co structure immobilize F− ions on the material surface via a ligand exchange mechanism, achieving highly selective and high-capacity fluoride ion removal. Simulation results indicate that this material exhibits an adsorption energy for F− of −1.72 eV, surpassing that of the unmodified material. Additionally, this material demonstrates excellent magnetic recovery and regeneration properties in practical applications (Fig. 10d. bottom), with an adsorption capacity reaching 80.2 mg/g. The material was desorbed by standing in a mild NaOH solution at pH = 11 for 3 h. After five cycles, the adsorption capacity decreased by less than 10 mg/g. FTIR and XPS results showed that the characteristic peaks of –OH and Co–F remained essentially unchanged, while SEM still revealed the original core-shell morphology, indicating that the ligand structure remained intact and the framework had not collapsed [106].

Although both cases delivered impressive performance with >99% removal efficiency and 5 cycles under extreme pH and high salt competition, the detection window for urea@MIL-100(Fe) gel remains at the 10−4 M level, and the threshold of Fe leaching <0.5 mg L−1 lacks continuous-flow validation [105]; The 80 mg g−1 capacity of Fe3O4@MOF-Co@CNF, benchmarked against pure F− solutions, plummeted by over 30% in real mine water due to coexisting Al3+ and PO43− ions [106]; Moreover, the toxicity leaching limit for Co remains undefined. To transition from a “laboratory highlight” to a “field-ready engineering pack-age,” subsequent column continuous flow testing using surface water matrices is required, along with sup-plenary calculations for ppm-level leaching rates and post-saturation regeneration energy consumption.

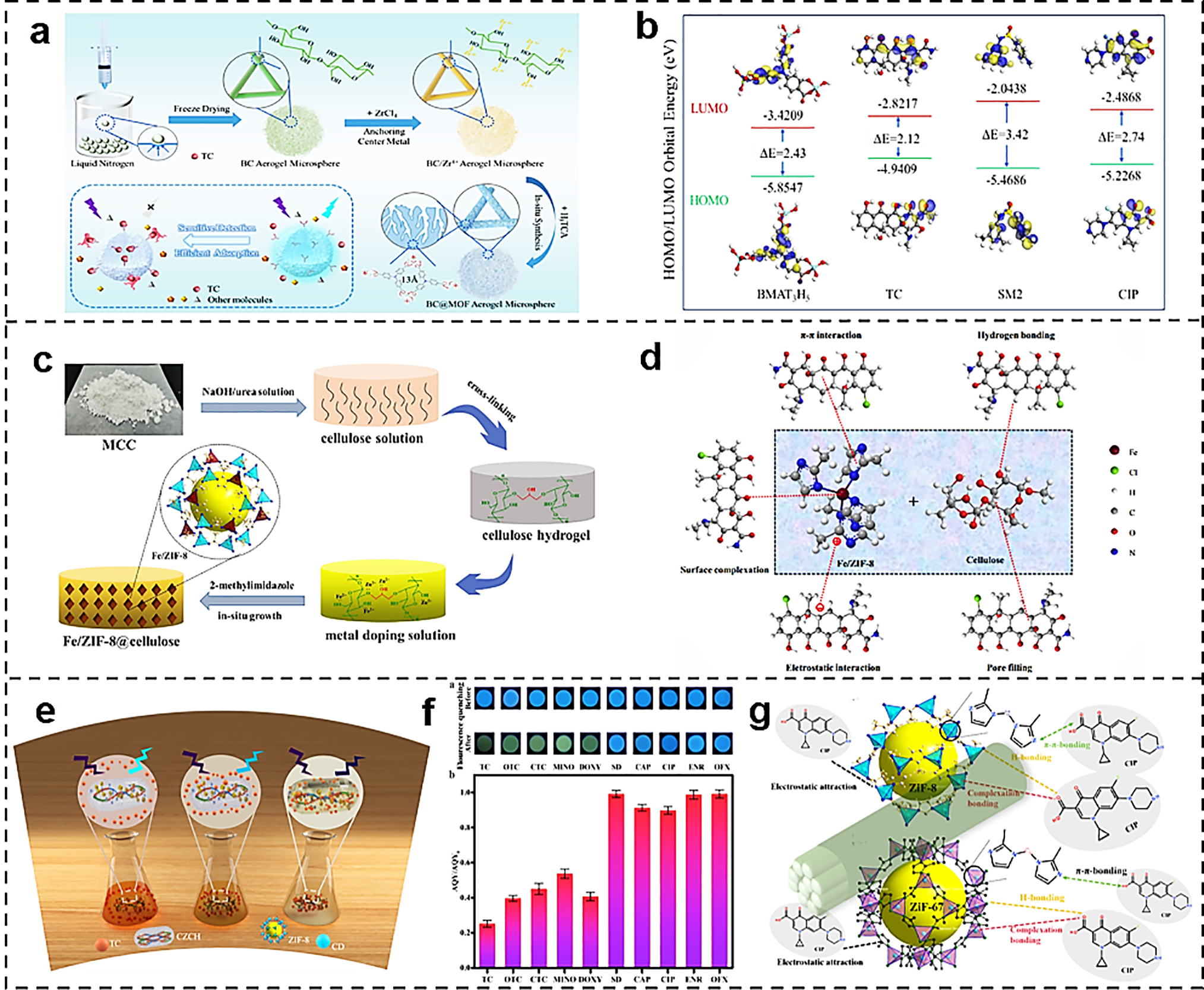

5.3 Detection and Adsorption of Antibiotics

MOF/cellulose composites also demonstrate a complete technological chain for emerging organic pollutants such as antibiotics. Yan et al. utilized bacterial cellulose (BC) as a template to grow Zr-MOF crystal nuclei in situ within its three-dimensional network, constructing tetracycline (TC)-responsive aerogel microspheres (BMAT3H5) with dual “detection-removal” functionality (Fig. 11a). The interconnected macro-/mesoporous channels within the microspheres shorten the diffusion path for TC molecules, while the micropore sieving effect of Zr-MOF synergistically enhances selectivity with ligands, achieving efficient TC adsorption with a capacity of 317.6 mg/g. This material operates stably within a pH range of 3–9 and retains over 70% of its performance after 8–10 cycles of methanol elution. As shown in Fig. 11b, density functional theory calculations indicate that the energy difference between the LUMO of TC and the HOMO of the aerogel microsphere is only 0.37 eV. Photogenerated electrons from TC can rapidly inject into the HOMO of BMAT3H5, triggering fluorescence quenching. This process follows a dynamic quenching mechanism with an S–V constant K_(SV) of (1.89 ± 0.001) × 106 M−1, achieving a detection limit as low as 28 ± 0.012 nM. Thermogravimetric analysis indicates that BMAT3H5 exhibits no significant mass loss below 500°C, demonstrating a thermal stability improvement of approximately 175°C compared to pure BC (which exhibits weight loss around 325°C). pH tolerance testing shows no shift in XRD diffraction peaks after 7 days of immersion in the pH range of 3–11, indicating no lattice structure rearrangement. Regarding interfacial characterization, SEM-EDS revealed a uniform distribution of Zr elements, indicating good contact between the MOF and the cellulose substrate [67].

Figure 11: (a) In situ growth of fluorescent Zr-MOF and construction of a bifunctional platform of aerogel microspheres [67]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [67]. (b) Frontier molecular orbitals of BMAT3H5 and antibiotics [67]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [67]. Copyright 2025, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118091294925). (c) Schematic diagram of the preparation process of Fe/ZIF-8@cellulose aerogel [107]. (d) Schematic illustration of the adsorption mechanism of TC [107]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [107]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118101153721). (e) Illustration of the mechanism of TC adsorption and detection by CZCH [77]. (f) Fluorescence of different antibiotics by CZCH in 365 nm UV light images and AQY changes against different antibiotics [77]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [77]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118101396202). (g) Possible adsorption mechanism of DH/ZIF [108]. Reference [108]. Reprinted with permission from Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright Clearance, License number (6118111168414)

Liu et al. reported a novel bimetallic organic framework (MOF)-based biosorbent material, Fe-doped ZIF-8-loaded cellulose aerogel (Fe/ZIF-8@cellulose), which was constructed by an in situ growth method: first, cellulose was dissolved in the NaOH/urea system, and crosslinked and lyophilized to obtain a porous aerogel; then immersed in Fe2+/Zn2+ methanol solution, added 2-methylimidazole to induce the growth of Fe/ZIF-8 nanocrystals on the surface of the skeleton, and washed and lyophilized to obtain the material (Fig. 11c). It was shown that the introduction of Fe significantly enhanced the adsorption performance of the material for tetracycline (TC) with a maximum adsorption capacity as high as 1359.2 mg/g, which was much higher than that of most existing polysaccharide-based adsorbents. Further mechanistic analysis (Fig. 11d) showed that the efficient adsorption of TC by Fe/ZIF-8@cellulose could be attributed to multiple synergistic effects: (1) electrostatic interactions, the surface charge of the material matches the morphology of the TC molecule under different pH conditions, which promotes adsorption; (2) hydrogen bonding, the formation of stable hydrogen bonds between cellulose hydroxyl groups and TC functional groups; (3) π-π stacking, the π-π interaction between the imidazole ring in ZIF-8 and the benzene ring in the TC molecule; (4) surface complexation, the formation of ligand bonding between the Fe3+/Fe2+ active sites form coordination bonds with hydroxyl and amino groups in the TC molecule; (5) pore filling effect, the three-dimensional porous structure provides abundant channels to enhance the diffusion and enrichment of TC molecules. This study not only expands the application boundary of MOF-based composites in the field of antibiotic removal but also provides a new idea for the construction of sustainable and efficient water treatment materials [107].

Zhang et al. designed and synthesized carbon dot-modified cellulose nanofiber/polyacrylamide/ZIF-8 composite hydrogel (CZCH), achieving an integrated platform for simultaneous TC adsorption and fluorescence detection. The hydrogel exhibits bright blue luminescence upon excitation at 365 nm. Complete fluorescence quenching of CZCH occurs only in the presence of TC derivatives, particularly TC. A similar trend is observed in the AQY of CZCH (Fig. 11e). Fig. 11f illustrates the mechanism of CZCH adsorption and detection of TC. The π-π* absorption band of TC highly overlaps with the excitation band of carbon dots (350 nm). This causes TC to preferentially absorb the excitation light. This reduces the number of effective photons reaching the carbon dots, leading to a linear decrease in the 480 nm fluorescence. This manifests as a linear decrease in the system’s fluorescence intensity with increasing TC concentration, while the fluorescence lifetime remains nearly unchanged. This confirms a purely dynamic internal filtering process. The linear response range is 0.2–50 μg/L, with a detection limit as low as 0.09 μg/L, far below drinking water regulatory limits. CZCH adsorbs TC through hydrogen bonding and electrostatic interactions, achieving a maximum adsorption capacity of 312.4 mg/g. When quantitatively compared with commercial activated carbon and various ZIF-based materials, CZCH’s adsorption capacity ranks second only to Fe-ZIF-8 while being several times higher than commercial activated carbon. Its unit cost for TC removal is just 0.07 yuan, significantly lower than activated carbon’s 5.74 yuan. In terms of regenerability, the capacity retention reached 85.6% after five adsorption–desorption cycles. SEM, FTIR, and XRD characterization revealed no significant damage to the 3D porous framework or key functional groups, confirming its reusability. The 5% weight loss observed in the TGA experiment occurred within the 100°C–250°C range, representing an intermediate level compared to similar ZIF-8-cellulose systems reported in the literature [77].

Li et al. performed hierarchical deconstruction of peach pomace with DES to selectively remove lignin and hemicellulose to obtain two kinds of multistage porous lignoskeletons, DH1 and DH2, and then constructed a series of ASDH/ZIF monolithic composites by using exposed hydroxyl groups in the pore channels of the wood for anchoring position and in situ growth of ZIF-8 or ZIF-67 (DH1/ZIF-8, DH2/ZIF-8, DH1/ZIF-67, DH2/ZIF-67) for the efficient trapping of ciprofloxacin (CIP) in wastewater. DES pretreatment enlarges the average pore size from 0.8 to 3–5 μm, increases the specific surface area by 4.7 times, provides sufficient nucleation sites for MOF nanocrystals, and shortens the CIP diffusion path, and the saturated adsorption amount of CIP of the four composites breaks through 1400 mg/g, which is a new record for the wood-based MOF composite system. The adsorption mechanism was attributed to π-π stacking, a hydrogen bonding network, and electrostatic attraction synergized with microporous filling (Fig. 11g). The adsorption driving forces are ranked as follows: Zn2+–carboxyl coordination > CIP–lignin hydrogen bonding ≈ π–π stacking > electrostatic attraction. Increasing the pore size from 0.8 to 4.1 μm elevated the Knudsen diffusion coefficient by 5.6-fold, establishing the mass transfer prerequisite for rapidly achieving 1400 mg/g. However, further enlarging the pore size yielded minimal capacity enhancement while compromising mechanical strength, confirming the 3–5 μm range as the optimal window. Although ZIF-67 theoretically exhibits higher coordination strength than ZIF-8, increased particle size and reduced surface positive charge mitigate this advantage. This demonstrates the necessity of simultaneously considering nanoscale characteristics and surface acid-base properties [108].

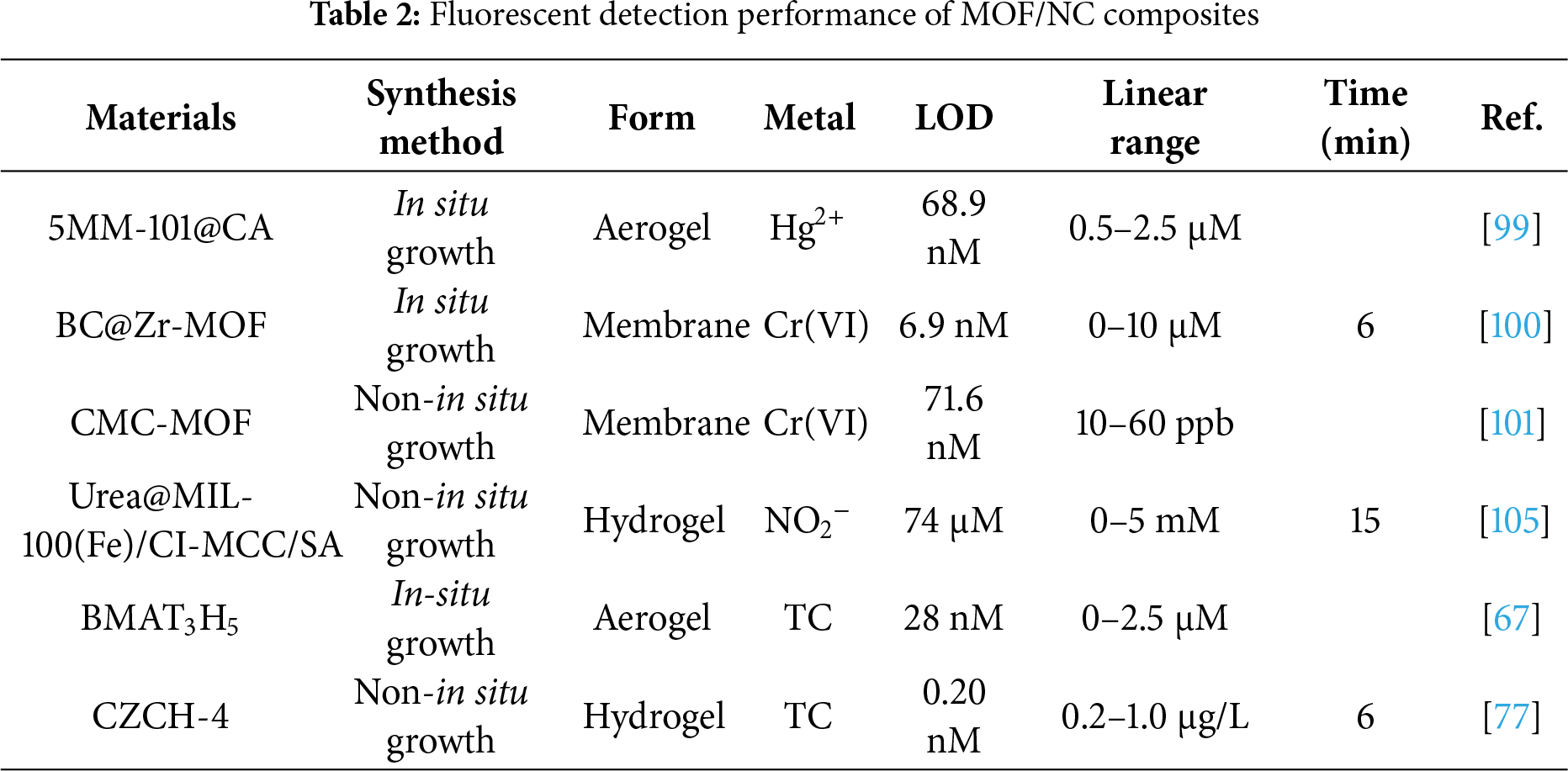

On the front lines of antibiotic pollution control, the MOF/cellulose platform has demonstrated comprehensive “detection-adsorption” capabilities. The aforementioned series of materials maintains structural integrity and signal stability under wide pH ranges, high salinity, and cyclic regeneration conditions, offering versatile options that balance sensitivity, capacity, and cost-effectiveness for the online monitoring and advanced purification of antibiotics like tetracycline and ciprofloxacin in wastewater. Performance summaries are provided in Table 1 (Adsorption Comparison) and Table 2 (fluorescence detection). Currently, most data originate from pure water or single-component solutions. Validating resistance to matrix interference and long-term column operational stability in real biochemical effluent would bring us one step closer to achieving “plug-and-play” functionality [109].

5.4 Degradation of Organic Dyes

Dyes are widely used in daily life and industrial production, with over a hundred tons of dye wastewater discharged into aquatic environments annually [110]. Dye wastewater is highly mobile and toxic, adversely affecting plants, animals, and even humans. Certain dyes possess complex structures that make them difficult to degrade, potentially causing permanent damage to water bodies.

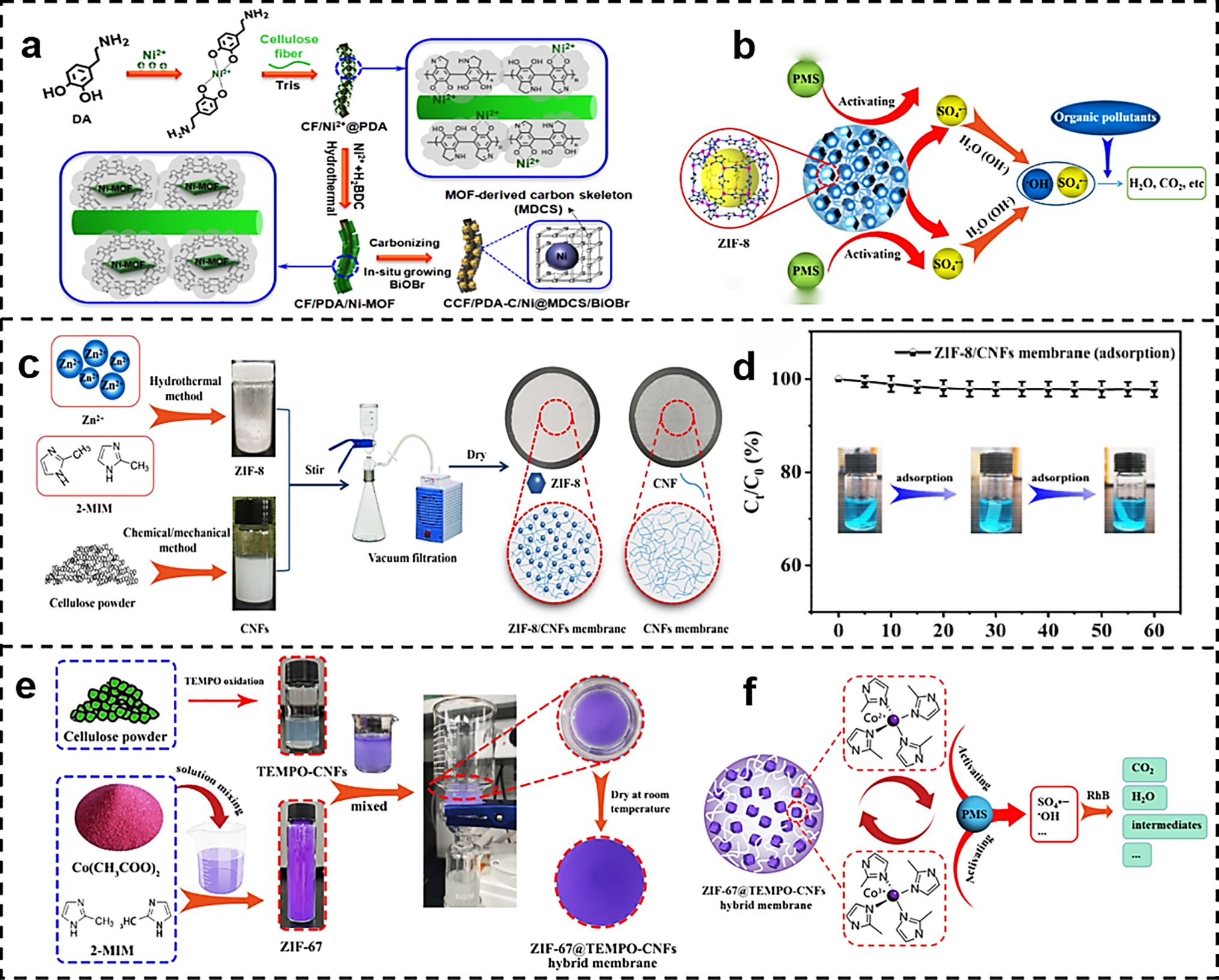

Various metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) with distinct metal nodes have demonstrated adsorption properties toward dye wastewater. As shown in Fig. 12a, Zheng et al. constructed a flexible visible-light-responsive composite paper by co-loading Ni nanoparticles encapsulated within a MOF-derived carbon scaffold (Ni@MDCS) with BiOBr onto cellulose fiber-based composite (CCF). This material achieved a degradation rate of 94.6% for Rhodamine B within 60 min, which is 2.5 times higher than that of conventional CCF/BiOBr paper. Moreover, it maintained high activity and structural integrity even after 10 cycles. Mott-Schottky measurements indicate that the conduction band of BiOBr lies at −0.85 V vs NHE, below the reduction potential of O2/·O2−, thermodynamically enabling superoxide radical generation. Band diagrams reveal that photoexcited electrons continuously transfer from the BiOBr conduction band to Ni nanoparticles via MDCS, achieving band alignment and redox potential matching. EPR results further confirm that this electron transfer pathway enhances the ·O2− signal, indicating improved active species kinetics and consequently synergistically boosting photocatalytic degradation efficiency [111].

Figure 12: (a) Schematic representation of the synthesis of CCF/PDA-C/Ni@MDCS/BiOBr [111]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [111]. Copyright 2024, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118111506342). (b) Schematic representation of the possible mechanism of PMS degradation of organic pollutants by the activation of ZIF-8/CNFs membranes [112]. (c) Schematic representation of the preparation of ZIF-8/CNFs membranes [112]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [112]. (d) Adsorptive degradation of methylene blue by ZIF-8/CNFs membranes [112]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [112]. Copyright 2022, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118120550577). (e) Illustration of the process of ZIF-67 synthesis, preparation of TEMPO-CNFs, and illustration of the fabrication process of ZIF-67@TEMPO-CNFs hybrid membranes [113]. (f)Schematic diagram of the possible mechanism of RhB degradation by ZIF-67@TEMPO-CNFs membrane + PMS system [113]. Reprinted with permission from Reference [113]. Copyright 2023, Elsevier and Copyright clearance, License number (6118111168414)

Zhu et al. utilized CNFs as a three-dimensional scaffold template to anchor ZIF-8 within the fiber network, constructing a ZIF-8/CNFs catalytic composite membrane (Fig. 12c). In the PMS system, Zn2+/ultrasonication synergistically reduces the O–O bond cleavage energy barrier, accelerating SO4•− generation. Supplemented with trace amounts of •OH, MB degradation exceeds 90% within 60 min. Quenching experiments quantitatively confirmed SO4•− as the dominant species. The observed rate constant (k_obs) increased from 0.038 to 0.068 min−1 at pH 3 to 7. The degradation rate accelerated 1.7-fold for every 10°C increase in temperature. PMS dosage linearly enhanced degradation between 60–120 mg, but excessive amounts induced self-quenching. As shown in Fig. 12b, in the presence of peroxymonosulfate (PMS), ZIF-8 activates PMS to generate SO4•− and •OH, synergistically degrading organic dye molecules. The degradation rate of methylene blue (MB) (Fig. 12d) exceeded 90% within 60 min. After 10 cycles of continuous filtration-degradation, the membrane flux recovery rate exceeded 95%, with no decline in catalytic efficiency [112].

Zhu et al. prepared catalytic hybrid membranes by in situ growth of ZIF-67 using TEMPO-oxidized cellulose nanofibers as the backbone (Fig. 12e). Fig. 12f shows the schematic diagram of the possible mechanism of rhodamine B degradation by ZIF-67@TEMPO-CNFs membrane + PMS system. ZIF-67@CNFs hybrid membrane activated PMS to produce SO4•− and •OH, and the degradation of rhodamine B degradation rate of 98.7%. This strategy provides a general paradigm for the hybridization of MOF with nanocellulose to construct foldable, easily recyclable, and scalable advanced oxidation catalytic membranes for multi-scenario deep purification of dyeing and printing wastewater, pharmaceutical residues, and so on [113].

MOF/NC Catalytic System (with dye degradation performance shown in Table 3) have demonstrated preliminary mild advantages in dye wastewater treatment, achieving “second-level reactions and compliance within min”. However, existing data largely lack a systematic evaluation of actual printing and dyeing effluents containing high salinity, multiple dyes, and surfactants. While kinetic studies have identified SO4•− as the primary species, models coupling radical steady-state concentrations, quenching side reactions, and membrane flux remain unestablished. Scaling efforts remain confined to sheet or short-fiber pilot tests, leaving continuous pressure drop, membrane fouling, cleaning cycles, and energy consumption calculations for integrated modules unexplored [114]. Only by completing “real-water quality-continuous flow-long-cycle” validation and establishing scaling design criteria that synergize membrane flux with activity can this mild approach achieve field-ready engineering feasibility.

MOF/NC composites, as a new type of functional materials with the sustainability of natural polymers and the functional specificity of MOFs, have become a research hotspot in environmental functional materials due to their potential for optimizing preparation technology and expanding water treatment applications. In this paper, the preparation methods, morphology control, and water treatment applications of these composites are systematically reviewed.

In terms of preparation techniques and morphology control, both non-in situ and in situ growth methods have produced effective cellulose/MOF composites. Among these, the in situ growth method has emerged as the mainstream strategy due to its ability to form tighter interfacial bonds and enhance composite stability. By regulating the synthesis conditions of MOFs on cellulose matrices, diverse composite morphologies—including aerogels, hydrogels, membranes, and microspheres—have been successfully developed. These structures provide a solid foundation for tailored applications across various water treatment scenarios.

In the field of water treatment, MOF/NC composites have demonstrated broad-spectrum pollutant purification ability and accurate detection performance. For heavy metal ions, the high selective adsorption and low detection limit can be realized by the ligand chelating effect of MOF and the hydrophilic network of cellulose. For highly toxic anions, the charge-matching design of MOF active sites effectively breaks the bottleneck of charge repulsion in anion adsorption. In the treatment of antibiotics and organic dyes, the composites not only realize efficient adsorption, but also can convert pollutants into harmless small molecules through photocatalytic degradation by partially loaded photosensitive MOF composites.

However, current research still faces three core challenges: (1) bottlenecks in large-scale production, where controlling MOF nucleation uniformity in in-situ growth methods is difficult, leading to significant batch-to-batch performance variations; (2) insufficient stability, as cellulose swells and degrades easily in acidic or alkaline water treatment environments, and weak MOF-cellulose interfacial bonding often causes active component detachment; (3) high application costs due to some expensive MOF precursors, and the need for improved recyclability and cycling stability of the composite materials.

Future research can focus on three key breakthroughs. In preparation techniques, develop efficient methods such as template-directed approaches and microwave-assisted synthesis to achieve the directed growth and uniform distribution of MOFs within cellulose matrices. For performance optimization, cellulose surfaces can be grafted with thiols/amines. Additionally, groups such as phosphates, carboxylic acid chains, or resorcinol can form strong bonds with MOFs. The electronic structure of MOFs can be regulated through heteroatom doping, metal substitution, and ligand extension. For instance, introducing sulfur-containing ligands enhances soft acid affinity for Hg2+, amino functionalization enhances electrostatic capture of Cr(VI) anions, iron doping promotes Fenton-like reactions for targeted azo dye degradation, and extended conjugated ligands increase π-π stacking to achieve selective adsorption of antibiotics. These strategies confer specific selectivity toward target pollutants. In application expansion, we will advance the practical verification of composite materials in complex aquatic matrices, develop integrated water treatment equipment combining “detection-adsorption” functions, and explore high-value utilization of cellulose-based fibers from agricultural waste to reduce material preparation costs. Overall, cellulose/MOF composites hold irreplaceable application potential in water treatment. Their technological maturity and industrial development will provide green and efficient new solutions for water purification and pollutant detection.

Acknowledgement: The research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32401508), Natural Science Foundation of Jilin Province (YDZJ202201ZYTS441), Jilin Province Development and Reform Commission Industrial Innovation Special Fund Project (2023C038-2), State Key Laboratory of Bio-Fibers and Eco-Textiles (Qingdao University) (KFKT202213) and Fundamental Research Funds for Wood Material Science and Engineering Key Laboratory of Jilin Province.

Funding Statement: The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support from Beihua University and Wood Material Science and Engineering Key Laboratory of Jilin Province.

Author Contributions: Zhimin Zhao: investigation, data curation, writing—original draft, visualization. Liyun Feng, Dongsheng Song: writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, visualization. Ming Zhang: writing—review & editing, supervision, resources, projection administration, funding acquisition. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data analyzed in this review are available within the cited articles.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

References

1. Münzel T, Hahad O, Lelieveld J, Aschner M, Nieuwenhuijsen MJ, Landrigan PJ, et al. Soil and water pollution and cardiovascular disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2025;22(2):71–89. doi:10.1038/s41569-024-01068-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Bolisetty S, Peydayesh M, Mezzenga R. Sustainable technologies for water purification from heavy metals: review and analysis. Chem Soc Rev. 2019;48(2):463–87. doi:10.1039/c8cs00493e. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Li X, Wang B, Cao Y, Zhao S, Wang H, Feng X, et al. Water contaminant elimination based on metal-organic frameworks and perspective on their industrial applications. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2019;7(5):4548–63. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b05751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Tu K, Ding Y, Keplinger T. Review on design strategies and applications of metal-organic framework-cellulose composites. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;291(48):119539. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119539. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

5. Nadar SS, Vaidya L, Maurya S, Rathod VK. Polysaccharide based metal organic frameworks (polysaccharide-MOFa review. Coord Chem Rev. 2019;396:1–21. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2019.05.011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Qin Q, Zeng S, Duan G, Liu Y, Han X, Yu R, et al. Bottom-up and top-down strategies toward strong cellulose-based materials. Chem Soc Rev. 2024;53(18):9306–43. doi:10.1039/d4cs00387j. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

7. Mahmoud MM, Chawraba K, El Mogy SA. Nanocellulose: a comprehensive review of structure, pretreatment, extraction, and chemical modification. Polym Rev. 2024;64(4):1414–75. doi:10.1080/15583724.2024.2374929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Wang S, Ma H, Ge S, Rezakazemi M, Han J. Advanced design strategies and multifunctional applications of nanocellulose/MXene composites: a comprehensive review. Mater Sci Eng R Rep. 2025;163:100925. doi:10.1016/j.mser.2025.100925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Song Y, Zhu W, Wang C, Li Z, Xin R, Wu D, et al. Nanoarchitectonics of metal-organic framework and nanocellulose composites for multifunctional environmental remediation. Adv Mater. 2025;37(39):2504364. doi:10.1002/adma.202504364. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Tao Y, Du J, Cheng Y, Lu J, Min D, Wang H. Advances in application of cellulose-MOF composites in aquatic environmental treatment: remediation and regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24(9):7744. doi:10.3390/ijms24097744. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

11. Long S, Zheng D, Zhang M, Gou W, Li Z, Song D. Preparation of photoluminescent transparent balsa wood with densifying structure for light-scattering windows based on cross-linking of lignocellulose and poly(vinyl alcohol). Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;311(Pt 1):143639. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.143639. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Mohanty B, Kumari S, Yadav P, Kanoo P, Chakraborty A. Metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) and MOF composites based biosensors. Coord Chem Rev. 2024;519:216102. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Zhu H, Yang X, Cranston ED, Zhu S. Flexible and porous nanocellulose aerogels with high loadings of metal-organic-framework particles for separations applications. Adv Mater. 2016;28(35):7652–7. doi:10.1002/adma.201601351. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

14. Wang JH, Kong F, Liu BF, Ren NQ, Ren HY. Preparation strategies of waste-derived MOF and their applications in water remediation: a systematic review. Coord Chem Rev. 2025;533(44):216534. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2025.216534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Lu Y, Liu C, Mei C, Sun J, Lee J, Wu Q, et al. Recent advances in metal organic framework and cellulose nanomaterial composites. Coord Chem Rev. 2022;461(16):214496. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2022.214496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Yang H, Zhu L, Zhou Y, Xu T, Zheng C, Yuan Z, et al. Engineering modulation of cellulose-induced metal-organic frameworks assembly behavior for advanced adsorption and separation. Chem Eng J. 2024;498:155333. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2024.155333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Li Z, Chen M, Zhu W, Xin R, Yang J, Hu S, et al. Advances and perspectives of composite nanoarchitectonics of nanocellulose/metal-organic frameworks for effective removal of volatile organic compounds. Coord Chem Rev. 2024;520(9):216124. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Khalil IE, Fonseca J, Reithofer MR, Eder T, Chin JM. Tackling orientation of metal-organic frameworks (MOFsthe quest to enhance MOF performance. Coord Chem Rev. 2023;481:215043. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Li Z, Zhang M, An C, Yang H, Feng L, Cui Z, et al. A colorimetric and fluorescent probe of lignocellulose nanofiber composite modified with Rhodamine 6G derivative for reversible, selective and sensitive detection of metal ions in wastewater. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;267(Pt 2):131416. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.131416. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Naderi L, Shahrokhian S. Wire-type flexible micro-supercapacitor based on MOF-assisted sulfide nano-arrays on dendritic CuCoP and V2O5-polypyrrole/nanocellulose hydrogel. Chem Eng J. 2023;476:146764. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.146764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Feng L, Zhang Z, Song D, Zhang M. Recent advances on cellulose-based fluorescent smart materials: design, fabrication and their applications. Int J Biol Macromol. 2025;329(1):147891. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2025.147891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Singh Jhinjer H, Jassal M, Agrawal AK. Metal-organic frameworks functionalized cellulosic fabrics as multifunctional smart textiles. Chem Eng J. 2023;478:147253. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2023.147253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Shahnawaz Khan M, Khalid M, Shahid M. What triggers dye adsorption by metal organic frameworks? The current perspectives. Mater Adv. 2020;1(6):1575–601. doi:10.1039/d0ma00291g. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Zhou N, Long S, Song D, Hui B, Cui X, An C, et al. Fabrication of carbon dots-embedded luminescent transparent wood with ultraviolet blocking and thermal insulating capacities towards smart window application. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;259(Pt 2):129358. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.129358. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

25. Iqbal D, Sarwar MI, Wu Q, Hussain A, Peng F, Yue W. Dual-functional cellulose-MOF hybrid membranes: synergistic removal and disinfection for tackling antibiotic pollution. Chem Eng J. 2025;524:169644. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2025.169644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Erum JKE, Zhao T, Yu Y, Gao J. MOF-derived tri-metallic nanoparticle-embedded cellulose aerogels for tetracycline degradation. Sustain Mater Technol. 2025;45:e01441. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2025.e01441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Lombardo S, Khalili H, Yu S, Mukherjee S, Nygård K, Bacsik Z, et al. In situ formation of zeolitic imidazolate frameworks on nanocellulose revealed by time-resolved synchrotron small-angle and wide-angle X-ray scattering. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2025;17(34):48976–88. doi:10.1021/acsami.5c10734. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Chen ZZ, Si S, Cai ZH, Jiang WJ, Liu YN, Zhao D. Application of metal-organic skeletons and cellulose composites in nanomedicine. Cellulose. 2023;30(16):9955–72. doi:10.1007/s10570-023-05523-y. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Yuan Z, Meng D, Wu Y, Tang G, Liang P, Xin JH, et al. Raman imaging-assisted customizable assembly of MOFs on cellulose aerogel. Nano Res. 2022;15(3):2599–607. doi:10.1007/s12274-021-3821-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Xu Y, Xu Y, Chen H, Gao M, Yue X, Ni Y. Redispersion of dried plant nanocellulose: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;294(10):119830. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119830. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Tong X, He Z, Zheng L, Pande H, Ni Y. Enzymatic treatment processes for the production of cellulose nanomaterials: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;299(5):120199. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.120199. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

32. Luo H, Cha R, Li J, Hao W, Zhang Y, Zhou F. Advances in tissue engineering of nanocellulose-based scaffolds: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;224(5):115144. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.115144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

33. Henschen J, Li D, Ek M. Preparation of cellulose nanomaterials via cellulose oxalates. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;213(6):208–16. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2019.02.056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Lin S, Kedzior SA, Zhang J, Yu M, Saini V, Huynh RPS, et al. A superprotonic membrane derived from proton-conducting metal-organic frameworks and cellulose nanocrystals. Chem. 2023;9(9):2547–60. doi:10.1016/j.chempr.2023.05.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

35. Song D, Zhao Z, Qiu Y, Zhang Z, Wang Y, Zhang M. One-pot aqueous synthesis of multifunctional composite flexible materials for oil spill treatment, thermal insulation, and controllable degradation. Chem Eng J. 2025;522(12):167570. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2025.167570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. Qiu Y, Zhang C, Zhang M, Zheng D, Song D, Long S, et al. A feasible strategy of photothermal nanocellulose/chitosan porous composite with brine tolerance and magnetic controllability for solar-driven polluted seawater purification. Carbohydr Polym. 2025;369(6):124281. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2025.124281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

37. Dai L, Cheng T, Duan C, Zhao W, Zhang W, Zou X, et al. 3D printing using plant-derived cellulose and its derivatives: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2019;203(1):71–86. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.09.027. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Mehandzhiyski AY, Ruiz-Caldas MX, Heasman P, Apostolopoulou-Kalkavoura V, Bergström L, Zozoulenko I. Is it possible to completely dry cellulose? Carbohydr Polym. 2025;365:123803. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2025.123803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Demir H, Daglar H, Gulbalkan HC, Aksu GO, Keskin S. Recent advances in computational modeling of MOFs: from molecular simulations to machine learning. Coord Chem Rev. 2023;484(6759):215112. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2023.215112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Zhou H, Han J, Cuan J, Zhou Y. Responsive luminescent MOF materials for advanced anticounterfeiting. Chem Eng J. 2022;431(22):134170. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2021.134170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Lorignon F, Gossard A, Carboni M. Hierarchically porous monolithic MOFs: an ongoing challenge for industrial-scale effluent treatment. Chem Eng J. 2020;393:124765. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.124765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Wang W, Yang K, Zhu Q, Zhang T, Guo L, Hu F, et al. MOFs-based materials with confined space: opportunities and challenges for energy and catalytic conversion. Small. 2024;20(37):e2311449. doi:10.1002/smll.202311449. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Mao L, Qian J. Interfacial engineering of heterogeneous reactions for MOF-on-MOF heterostructures. Small. 2024;20(20):e2308732. doi:10.1002/smll.202308732. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Rego RM, Kuriya G, Kurkuri MD, Kigga M. MOF based engineered materials in water remediation: recent trends. J Hazard Mater. 2021;403:123605. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.123605. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Chen C, Fei L, Wang B, Xu J, Li B, Shen L, et al. MOF-based photocatalytic membrane for water purification: a review. Small. 2024;20(1):2305066. doi:10.1002/smll.202305066. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

46. Rahman A, Wang W, Govindaraj D, Kang S, Vikesland PJ. Recent advances in environmental science and engineering applications of cellulose nanocomposites. Crit Rev Environ Sci Technol. 2023;53(5):650–75. doi:10.1080/10643389.2022.2082204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Zhang XF, Wang Z, Ding M, Feng Y, Yao J. Advances in cellulose-metal organic framework composites: preparation and applications. J Mater Chem A. 2021;9(41):23353–63. doi:10.1039/d1ta06468a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Yin X, Zha J, Gregor S, Ding S, Alsuwaidi A, Zhang X. Finned hierarchical MOFs supported on cellulose for the selective adsorption of n-hexane and 1-hexene. Chem Commun. 2021;57(100):13756–9. doi:10.1039/d1cc04548b. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

49. Kim ML, Otal EH, Hinestroza JP. Cellulose meets reticular chemistry: interactions between cellulosic substrates and metal-organic frameworks. Cellulose. 2019;26(1):123–37. doi:10.1007/s10570-018-2203-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]