Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Enhancing Mechanical Properties of Biobased Polyurethane Composites Using Birch Flour and Diatomite Fillers

1 Center of Chemical Engineering, ITMO University, Kronverkskiy pr. 49, Saint-Petersburg, 197101, Russia

2 Institute of Macromolecular Compounds, Branch of Petersburg Nuclear Physics Institute Named by B.P. Konstantinov of National Research Centre «Kurchatov Institute», Bolshoi pr. 31, Saint-Petersburg, 199004, Russia

* Corresponding Author: Vjacheslav V. Zuev. Email:

(This article belongs to the Special Issue: Advances in Eco-friendly Wood-Based Composites: Design, Manufacturing, Properties and Applications – Ⅱ)

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(10), 2043-2058. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0079

Received 25 March 2025; Accepted 25 May 2025; Issue published 22 October 2025

Abstract

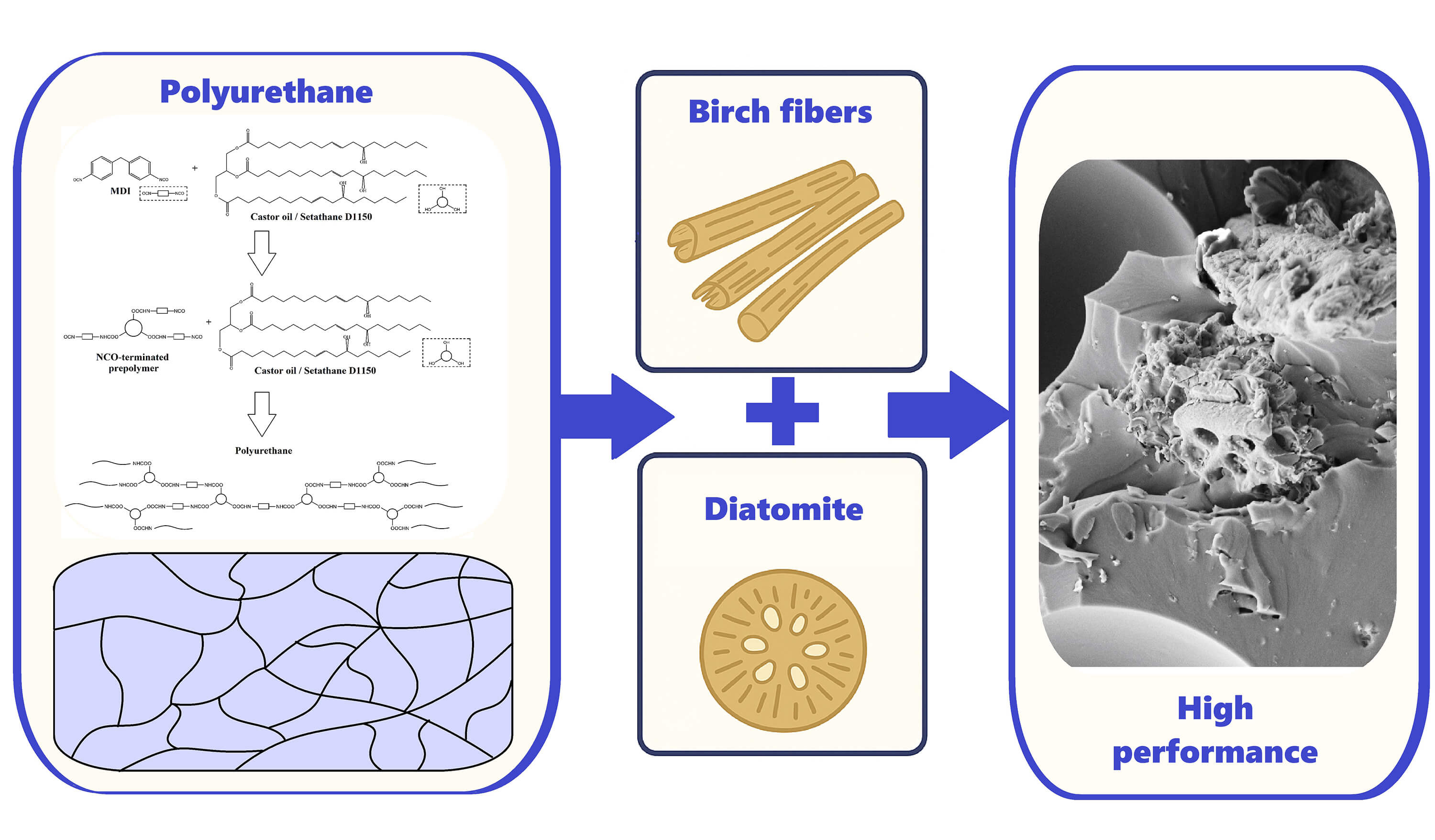

In this study, the polyurethanes (PU) were synthesized from 4,4′-methylene diphenyl diisocyanate and biobased ethoxylated castor oil or one mixture of ethoxylated and neat castor oil by direct mixing method. Utilization of ethoxylated castor oil increases the tensile strength of PU up to 2.75 times (from 3.2 to 8.8 MPa), compared to PU based on neat castor oil. The PU composites filled with birch flour, diatomite, and their mixture were prepared using a homemade dissolver with a cutter-shaped attachment at a speed of 1500 r min−1. The tensile strength of PU composites filled with birch flour increases up to two time at loading 5–30 wt.%. Application of combined birch flour/diatomite additives has similar effect. The tensile strength of PU composites based on one to one mixture of ethoxylated and neat castor oil and filled with birch flour or combined birch flour/diatomite additives increases sharply up to 16–17 fold (up to 18.1 MPa). The birch flour and diatomite well soaked polymer matrix. The main factor determining mechanical performance is the morphology of PU samples and composites. Formation of ordered lamella-like structure of the amorphous phase of PU matrix leads to an increase in mechanical performance and glass transition temperatures. The formation of a disordered unstructured soft phase of starting PU leads to a decline of these functional properties.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileA global movement to shift economic practices toward resource-effective methods is underway, with significant potential to advance sustainable materials and technologies. Concurrently, increasing population demands are straining food resources, limiting the use of edible vegetable oils for biodiesel production. In this context, non-edible oils like castor oil emerge as promising alternatives for various industrial applications [1].

Wood represents a renewable resource extensively cultivated on non-agricultural lands across regions like the Amazon, northern Eurasia, and Canada. However, high-demand species such as tropical hardwoods (e.g., ebony) face severe overexploitation, both legal and illegal, leading to tropical forest degradation. In northern regions, slow-growing conifers dominate commercial forestry, creating a need for fast-growing alternatives. In Russia, so-called “weed” species like birch offer potential solutions, though their shorter fibers compared to conifers present challenges for paper production [2].

Birch’s rapid growth makes it an attractive renewable resource, yet its application in polymer composites remains underexplored. Comprising two-thirds of Russia’s deciduous forests, birch wood features unique characteristics: elasticity, fine porosity, straight grain, and medium density that facilitate mechanical and manual processing. Its excellent absorption properties allow deep penetration of oils and impregnants, enabling uniform coloration [3]. These properties suggest the potential for enhancing mechanical performance in polymer composites through chemical bonding between birch fibers and polymer matrices [4].

Similar approaches have demonstrated success with various plant fibers [5], including bamboo [6] and kenaf [7]. The polyurethane (PU) composites reinforced these fibers achieving tensile strengths of 10–13 MPa. However, such research remains limited despite growing bioplastic demand [8], with agricultural feedstock requirements and production costs posing economic challenges.

This study aims to develop birch wood fiber-reinforced PU composites with optimized mechanical properties. Utilizing bio-based castor oil as a polyol represents an advanced approach [9], though its hydroxyl groups’ reactivity is hindered by steric effects [10], potentially yielding less ordered PU matrices [11] and compromised mechanical performance. To address this, we employ ethoxylated castor oil (Scheme 1), where oxyethylene units mitigate steric hindrance—a novel modification for PU synthesis.

Scheme 1: Structures of the major component of castor oil (triester of glycerol and ricinoleic acid) (I) and its ethoxylated derivative (II) as main component of Setathane D1150

Setathane D1150 was supplied by Allenex GmbH (Frankfurt am Main, Germany). MDI was obtained from Wanhua Chemical (Yantai, China). The catalyst TMG 722 for PU synthesis was supplied by TMG Industrial Chemicals Co. (Taiwan). Birch flour (trademark M400) was from OOO Legnus Resurs (Saint Peterburg, Russia) with fiber length from one to hundreds µ. Such length of fibers is optimal for the achievement of good mechanical performance of polymer composites. The characteristics of birch flour are given in our previous paper [12]. Diatomite (OOO Chimenergo, Saint Petersburg, Russia) with the initial size of particles between 700 µm and 1.2 mm (See Supplementary Materials) was milled before use in coffee grinder Bosh (Abstatt, Germany) yielding a powder with particle sizes from tens of nanometers to 1–5 µm [12]. The diatomite powder was dried in a thermostat at 120°C for 24 h before use.

2.1 The Synthesis of Composites

The 50 wt.% concentrate of birch flour or diatomite powder in Setathane D1150 was prepared using a homemade dissolver with a cutter-shaped attachment at a speed of 1500 r/min. After that, this concentrate was skipped three times through three roller machines (Shanghai Root Mechanical and Electrical Equipment Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) to destroy aggregates of birch flour or diatomite. For better infiltration of Setathane D1150 in birch flour or diatomite particles the mixture stayed in thermostat for 24 h at 110°C. This concentrate was mixed with a calculated amount of oligomeric MDI and after adding 0.35 wt.% of catalyst (tin dibutyl dilaurate) poured into silicone forms for film formation (Scheme 2). The films were ready for measurements after staying at 50°C for 24 h.

Scheme 2: Schematic representation of polyurethane synthesis

2.2 Instrumentation and Analytical Conditions

The mechanical properties of the PU composites such as tensile strength and elongation at break were measured according to ISO 527-2 using the Universal Testing Machine Instron 5966 with sample dimensions: 0.1 × 0.01 × 0.00035 m. At least 5 samples were used for each composition; Tg determination by DSC and SEM image recording was performed as described previously [13].

FT-IR spectra were recorded using spectrometer Vertex 50 (Bruker, Germany) in ATR mode. 1H NMR spectra were recorded using Avance 400 spectrometer (Bruker, Germany) (frequency 400 MHz on 1H) using chloroform-d as a solvent and internal standard.

Liquid chromatography (LC) experiments were carried out using the Shimadzu LC-30 NEXERA system equipped with the Shimadzu LCMS-8030 Triple Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer (Shimadzu, Japan). The LC analysis of castor oil samples was performed using Agilent Zorbax Eclipse Plus C18 Rapid Resolution HD (2.1 mm × 100 mm 1.8 μm) column and acetonitrile/water (80/20) mobile phase.

The selection of chemically modified castor oil (commercially available as Setathane D1150) as the polyol component for PU composite preparation was driven by the need to investigate subtle factors affecting PU morphology and performance. Setathane D1150 represents ethoxylated castor oil with an equivalent weight of approximately 360 per hydroxyl group [14], compared to about 310 for unmodified castor oil. This difference confirms the incorporation of one ethylene oxide unit per ricinoleic acid hydroxyl group (Scheme 1), further supported by mass spectrometry analysis revealing a molecular ion peak at m/z 1065 for Setathane D1150’s main component.

Castor oil consists of a mixture of glycerol triesters with various fatty acids [15], where ricinoleic acid (85%–95%) dominates alongside minor components including oleic, linoleic, stearic, and palmitic acids. Setathane D1150 maintains this compositional profile. Comparative analysis of these polyols’ molecular structures (Scheme 1) indicates that the hydroxyl groups in triester I exhibit lower reactivity than those in polyol II due to steric hindrance. Furthermore, Setathane D1150’s absence of steric constraints enhances its wettability toward fillers like birch flour or diatomite.

The steric effects in castor oil promote the formation of less-ordered polymeric structures when incorporated into the matrix, thereby inhibiting the development of well-defined hard domains in the PU network [16]. Consequently, castor oil-based PU demonstrates limited mechanical performance (tensile strength ~3.2 MPa, elongation ~35%) [13]. Substitution with Setathane D1150 significantly improves these properties (tensile strength: 8.8 MPa, elongation: 148%; Table 1), attributable to distinct morphological differences.

Notably, Setathane D1150-derived PU exhibits uniform crystal distribution throughout the polymer matrix (Fig. 1B), potentially explaining its enhanced mechanical characteristics [17]. All PU samples contain urea linkages regardless of preparation method or initial water content [18], as confirmed by IR spectroscopy through the characteristic urea C=O stretching band at 1666 cm−1 a diagnostic feature of polyurea-polyurethane copolymers [19] (Fig. 2). Quantitative urea bond content in the studied PUs is presented in Table 1.

Figure 1: SEM images PU prepared from castor oil and its ethoxylated derivatives (A) and pure ethoxylated castor oil (B,C)

Figure 2: FTIR spectra of sample SetBF10 in the carbonyl stretching region with deconvolution

These urea bonds promote the formation of crystallites, thereby removing fragments containing these bonds from the polymer matrix. Hence, the presence of small amounts of crystallites (and urea bonds as well) did not influence mechanical performance but had a pronounced effect on morphology. It is known that there exists a close relationship between the microphase structure of PU and its mechanical performance [20,21]. These crystals themselves have approximately the same sizes. The crystals serve as the centers of nucleation of lamella-like spherulites of an amorphous phase. These spherulites show needle-like structures with ribbons well oriented in one direction (towards to nucleation center (crystal)) (Fig. 1B). The images with higher magnification show that the amorphous phase of synthesized PU has a structure typical for all PU structures with worm-like rigid domains in a soft amorphous matrix (Fig. 1C) [22]. The dimensions of these rigid domains are also typical for PU with diameters of 3–6 nm and lengths of 30–200 nm [23]. This ordering of the soft phase has a dramatic effect on their glass transition temperature. The glass transition temperature of PU based on castor oil is −25.5°C [13]. The change of castor oil for its ethoxylated derivative leads to the dramatic increase of glass transition temperature of PU up to 18.4°C. Therefore, the ordered lamellar structure of the soft phase restricts the segmental movement in a polymer matrix and thereby leads to the improvement of mechanical performance. Hence, morphology has a dominant effect on mechanical performance.

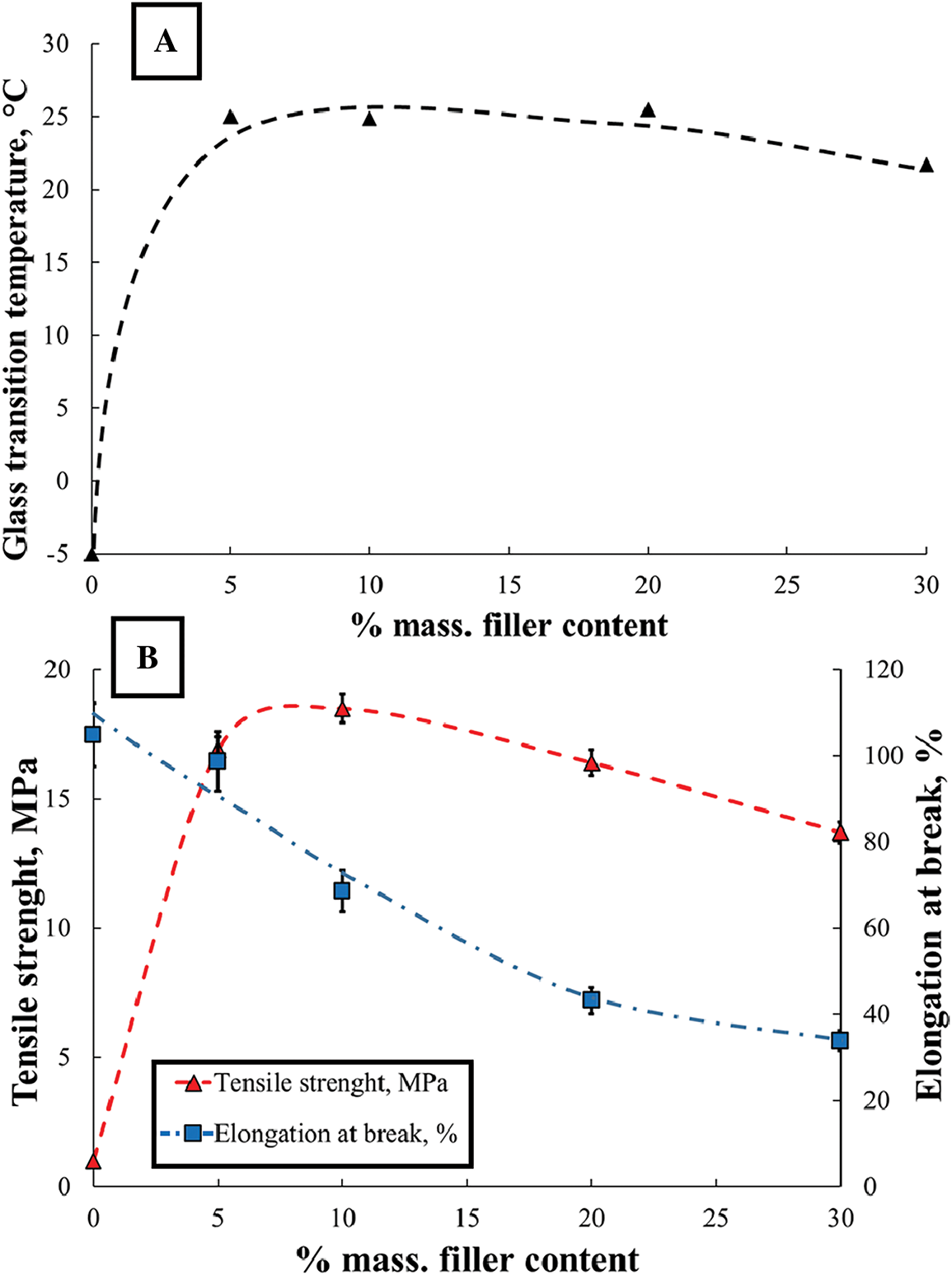

The use of ethoxylated castor oil has a dramatic effect on the mechanical properties of PU composites reinforced with birch flour. The addition of 5 wt.% of such fillers leads to an increase of tensile strength up to 14.4 MPa, which is four times higher than the tensile strength of PU composite synthesized using neat castor oil (Fig. 3) [13]. Elongation at break also increased threefold (by up to 102%). The SEM investigations (Fig. 4A) show that the introduction of birch flour into the PU matrix leads to the formation of a well-developed lamellar structure with smaller lamella size than in neat PU. It leads to the restriction of segmental mobility in a polymer matrix and, as a result, to an increase of glass transition temperature up to 25.4°C (Fig. 3A). SEM images show that birch flax is wetted well by the polymer matrix. It should be noted that the birch flour fillers are well distributed in the polymer matrix and are received in the form of individual particles without aggregation (Fig. 4A).

Figure 3: The dependence of glass transition temperature (A); tensile strength and elongation at break (B) for PU composites with ethoxylated castor oil filled with birch flour vs. loading

Figure 4: SEM images of chipped surface (A) and fracture surface (B) of PU composite with ethoxylated castor oil filled with 5 wt.% of birch flour

SEM analysis of fracture surfaces from stress-damaged test samples (Fig. 4B) reveals a cohesive failure mechanism in the studied wood composites. Under applied stress, the lamellar structure of the PU matrix undergoes destruction, forming a smooth, fluid-like medium that flows until rupture occurs. The birch fibers remain embedded within the polymer matrix without tearing, though some fibers pull out from the unwetted central regions of the flax bundles. These observations demonstrate excellent incorporation of birch flour filler into the polymer matrix, confirming its pronounced reinforcement effect.

We prepared composites containing up to 30 wt.% birch flour (Fig. 3), all exhibiting similar morphology: well-impregnated birch fibers within a lamellar PU matrix, with lamella size decreasing as filler concentration increases. This structural evolution correlates with a slight increase in glass transition temperature (Fig. 3B). While tensile strength remains largely unaffected (Fig. 3B), elongation at break decreases significantly (Fig. 3B)—behavior consistent with the unchanged failure mechanism evident in SEM images.

To enhance mechanical performance, we employed our previously developed birch flour-diatomite complex additive system [12]. Diatomite, a natural siliceous sedimentary rock that crumbles into fine (1–5 μm) white powder, previously showed synergistic reinforcement with birch flour [12]. In the current study, this combination yielded only marginal tensile strength improvement over pure birch flour (Fig. 5B), though composite elasticity increased (Fig. 5A). SEM analysis (Fig. 6A) reveals maintained lamellar matrix morphology and excellent filler dispersion without aggregation, comparable to birch flour-only composites.

Figure 5: The dependence of glass transition temperature (A); tensile strength and elongation at break (B) of PU composites with ethoxylated castor oil filled with birch flour/diatomite vs. loading

Figure 6: SEM images of chipped surface (A) and fracture surface (B) of PU composite with ethoxylated castor oil filled with 5 wt.% of birch flour/diatomite

The highly porous, hydrophilic diatomite particles exhibit thorough matrix impregnation, behaving similarly to birch flour. Fracture surface analysis (Fig. 6B) shows an identical failure mechanism, though diatomite particles cleanly debond from the matrix without fracture (unlike birch fibers), potentially contributing to the observed strength enhancement [24].

Ethoxylated castor oil is expensive relative to neat castor oil. To improve the economic efficiency of PU composites, we use a mixture of castor oil and Setathane D1150 as a polyol. The use of this mixture for PU synthesis leads to the deterioration of their mechanical properties (Table 1). As shown in SEM images (Fig. 1A), the reason for this is the lack of ordered structure in the polymer matrix. The SEM images show that the formation of lamella-like structure is not observed for these compositions, and the amorphous phase does not indicate any signs of ordering (Fig. 1A). As a result, the glass transition temperature dropped to −5.0°C. Such a disordered structure leads to low values of tensile strength [25].

The use of one mixture of castor oil and Setathane D1150 as polyol for the preparation of PU composites filled with birch flour or one mixture of birch flour and diatomite yields excellent results (Figs. 7 and 8). The tensile strengths of composites at 5–20 wt.% loading increase 16–17 times and reach the values obtained using pure Setathane D1150 (Table 1). As shown in SEM images, the basis for this result [26] is the formation of the same morphology of PU composites as observed for composites synthesized using pure Setathane D1150 (Fig. 9). The glass transition temperatures of composites also have similar values (Table 1).

Figure 7: The dependence of glass transition temperature (A); tensile strength and elongation at break (B) for PU composites with one to one mixture of neat castor oil and ethoxylated castor oil filled with birch flour vs. loading

Figure 8: The dependence of glass transition temperature (A); tensile strength and elongation at break (B) for PU composites with one to one mixture of neat castor oil and ethoxylated castor oil filled with birch flour/diatomite vs. loading

Figure 9: SEM images of chipped surface of PU composites with one to one mixture of neat castor oil and ethoxylated castor oil filled with birch flour (A) and birch flour/diatomite (B) at 5 wt.% loading

Hence, the formation of morphology has the dominant effect on mechanical performance and thermal operating interval of PU composites filled with birch fluor or diatomite. It is seen from fracture surface observations. For neat PU and PU-based composites under study, extensive plastic deformation or necking takes place before fracture. As one can see from SEM images of fracture surfaces (Fig. 10), the fracture of samples involves a high degree of plastic deformation of spherulites. In this case, a multitude of necks is formed in each spherulite (Fig. 10). Therefore, the micromechanical stability of lamellar-like spherulites of the soft phase of the polymer matrix is the determining factor of the mechanical performance of biobased PU composites under study [27].

Figure 10: SEM images of fracture surface of PU composite with ethoxylated castor oil filed with 5 wt.% of birch flour

In this paper, PU was synthesized from 4,4′-methylene diphenyl diisocyanate and biobased ethoxylated castor oil or one mixture of ethoxylated and neat castor oil. The use of ethoxylated castor oil increases the tensile strength of PU to 2.75 times in comparison with PU based on neat castor oil. The tensile strength of PU composites filled with birch flour increases up to two times at loading 5–30 wt.%. The use of combined birch flour/diatomite additives has a similar effect. The tensile strength of PU composites based on one mixture of ethoxylated and neat castor oil and filled with birch flour or combined birch flour/diatomite additives increases sharply up to 16–17 times. The birch flax and diatomite are well soaked by the polymer matrix. The main factor determining mechanical performance is the morphology of PU samples and composites. The formation of an ordered lamella-like structure in the amorphous phase of the polymer matrix leads to an improvement in mechanical performance and increased glass transition temperatures. The micromechanical stability of lamellar-like spherulites of the soft phase of the polymer matrix is the determining factor of the mechanical performance of biobased PU composites under study because their fracture mechanism is based on the plastic deformation of spherulites.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: The authors received no specific funding for this study.

Author Contributions: Dmitry S. Konovalov: investigation, methodology. Natalia N. Saprykina: SEM images recording. Vjacheslav V. Zuev: supervision, writing. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: All data are available in the paper.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0079/s1.

References

1. Ma Y, Wang R, Li Q, Li M, Liu Q, Jia P. Castor oil as a platform for preparing bio-based chemicals and polymer materials. Green Mater. 2022;10(3):99–109. doi:10.1680/jgrma.20.00085. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Côté J-F, Luther JE, Lenz P, Fournier RA, van Lier OR. Assessing the impact of fine-scale structure on predicting wood fibre attributes of boreal conifer trees and forest plots. For Ecol Manag. 2021;479:118624. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2020.118624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Ershov AE, Stroganova TS. Structure and properties of biomorphic carbon scaffolds based on pressed birch and alder wood. Carbon Trends. 2023;13(14):100312. doi:10.1016/j.cartre.2023.100312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Bazli M, Heitzmann M, Hernandez BV. Durability of fibre-reinforced polymer-wood composite members: an overview. Compos Struct. 2022;295(6):115827. doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2022.115827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ajayi NE, Rusnakova S, Ajayi AE, Ogunleye RO, Agu SO, Amenaghawon AN. A comprehensive review of natural fiber reinforced Polymer composites as emerging materials for sustainable applications. Appl Mater. 2025;43:102666. doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2025.102666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Lopes MDM, de Souza Pádua M, Gazem de Carvalho JPR, Tonini Simonassi N, Perissé Duarte Lopez F, Colorado HA, et al. Natural based polyurethane matrix composites reinforced with bamboo fiber waste for use as oriented strand board. J Mater Resch Technol. 2021;12(2):2317–24. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2021.04.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Noor Azammi AM, Sapuan SM, Ishak MR, Sultan MTH. Physical and damping properties of kenaf fibre filled natural rubber/thermoplastic polyurethane composites. Def Technol. 2020;16(1):29–34. doi:10.1016/j.dt.2019.06.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Rosenboom JG, Langer R, Traverso G. Bioplastics for a circular economy. Nat Rev Mater. 2022;7(2):117–37. doi:10.1038/s41578-021-00407-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

9. Friedrich D. Welfare effects from eco-labeled crude oil preserving wood-polymer composites: a comprehensive literature review and case study. J Clean Prod. 2018;188(2):625–37. doi:10.1016/J.JCLEPRO.2018.03.318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Ma Y, Zhu X, Zhang Y, Li X, Chang X, Shi L, et al. Castor oil-based adhesives: a comprehensive review. Ind Crops Prod. 2024;209(12):117924. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2023.117924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Yilgor I, Yilgor E, Wilkes GL. Critical parameters in designing segmented polyurethanes and their effect on the morphology and properties: a comprehensive review. Polymer. 2015;58(6):A1–36. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2014.12.014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Konovalov DS, Saprykina NN, Zuev VV. Green based composite polyurethane coatings for steel. Iran Polym J. 2024;33(6):1627–36. doi:10.1007/s13726-024-01341-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Konovalov DS, Saprykina NN, Zuev VV. High-performance castor oil-based polyurethane composites reinforced by birch wood fibers. Appl Sci. 2023;13:8258. doi:10.3390/app13148258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Setathane D. Product Datasheet/nuplex®. [cited 2025 May 1]. Available from: https://allnex.com/en/product/010faff2-5d57-4c45-bf7d-429e151cc23f/setathane-d-1150. [Google Scholar]

15. Hossain A, Pal A, Salem S. Development of method and analysis protocol for fatty acids derivatives of castor oil by using gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. Biocatal Agric Biotechnol. 2024;61(2):103408. doi:10.1016/j.bcab.2024.103408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Sami S, Yildirim E, Yurtsever M, Yurtsever E, Yilgor E, Yilgor I, et al. Understanding the influence of hydrogen bonding and diisocyanate symmetry on the morphology and properties of segmented polyurethanes and polyureas: computational and experimental study. Polymer. 2014;55(18):4563–76. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2014.07.028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Zhang Z, Zhu S. Crystal size effect on large deformation mechanisms of thermoplastic polyurethane. Extrem Mech Lett. 2025;74:102275. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2024.102275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

18. Voda A, Beck K, Schauber T, Adler M, Dabisch T, Bescher M, et al. Investigation of soft segments of thermoplastic polyurethane by NMR, differential scanning calorimetry and rebound resilience. Polym Test. 2006;25(2):203–13. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2005.10.007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Shi Y, Zhan X, Luo Z, Zhang Q, Chen F. Quantitative IR characterization of urea groups in waterborne polyurethanes. J Polym Sci. 2008;46(7):2433–44. doi:10.1002/pola.22577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Jiang J, Gao H, Wang M, Gao L, Hu G. Effect of fillers on the microphase separation in polyurethane composites: a review. Polym Eng Sci. 2023;63(12):3938–62. doi:10.1002/pen.26507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

21. Cheng B-X, Gao W-C, Ren X-M, Ouyang X-Y, Zhao Y, Zhao H, et al. A review of microphase separation of polyurethane: characterization and applications. Polym Test. 2022;107:107489. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2022.107489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Princi E, Vicini S, Stagnaro P, Conzatti L. The nanostructured morphology of linear polyurethanes observed by transmission electron microscopy. Micron. 2011;42(1):3–7. doi:10.1016/j.micron.2010.09.007. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

23. Wu S, Ma S, Zhang Q, Yang C. A comprehensive review of polyurethane: properties, applications and future perspectives. Polymer. 2025;327(52):128361. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2025.128361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

24. Konale A, Srivastava V. On modeling fracture of soft polymers. Mech Mater. 2025;206(8):105346. doi:10.1016/j.mechmat.2025.105346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Huang M, Li Z, Xu W, He S, Liu W, Jiang L, et al. Visualization and quantification of microphase separation in thermoplastic polyurethanes under different hard segment contents and its effect on the mechanical properties. Polym Test. 2024;131:108329. doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2024.108329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Lee JH, Min MH, Lee SG. Effect of polyhydric alcohols on the mechanical and thermal properties, porosities, and air permeabilities of polyurethane-blended films. J Appl Polym Sci. 2019;136:47429. doi:10.1002/app.47429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Jiang C, Miao C, Zhou J, Yuan M. Insights into damage mechanisms and advances in numerical simulation of spherulitic polymers. Polymer. 2025;318(10):128001. doi:10.1016/j.polymer.2024.128001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools