Open Access

Open Access

REVIEW

Toxicological and Safety Considerations of Nanocellulose-Containing Packaging Materials

Instituto de Materiales de Misiones (IMAM), Universidad Nacional de Misiones (UNaM), CONICET, Facultad de Exactas, Químicas y Naturales (FCEQyN), Programa de Celulosa y Papel (PROCyP), Félix de Azara 1552, Posadas, Misiones, PC, 3300, Argentina

* Corresponding Author: Lucila M. Curi. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(11), 2109-2137. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0069

Received 21 March 2025; Accepted 25 June 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

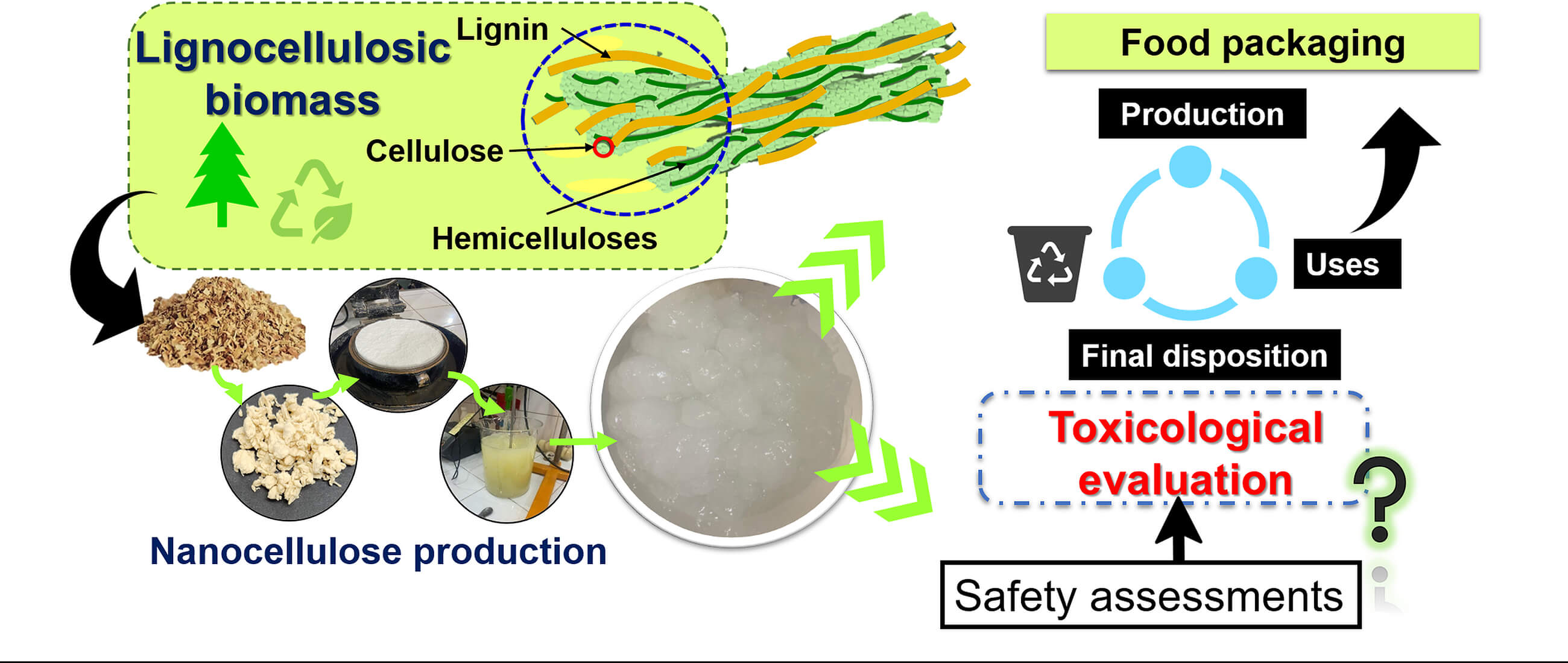

The global demand for renewable and sustainable non-petroleum-based resources is rapidly increasing. Lignocellulosic biomass is a valuable resource with broad potential for nanocellulose (NC) production. However, limited studies are available regarding the potential toxicological impact of NC. We provide an overview of the nanosafety implications associated mainly with nanofibrillated cellulose (CNF) and identify knowledge gaps. For this purpose, we present an analysis of the studies published from 2014 to 2025 in which the authors mention aspects related to toxicity in the context of packaging. We also analyze the main methods used for toxicity evaluations and the main studies about toxicity evaluation using different biomarkers for a broad interpretation. This comprehensive biblio-graphic review highlights the critical need for further research to elucidate the mechanisms fully underlining NC toxicity, mainly due to its nanofibrillar structure. We focus on the cellular responses across different evaluated cell types through in vitro evaluation, always within the context of the dose used, the type of material or its source, and the type of biomarkers used in the assessments. The importance of addressing safety considerations and key knowledge gaps for the responsible use of CNF derived from lignocellulosic biomass and its bionanocomposites in food packaging is highlighted.Graphic Abstract

Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material File1.1 NC: A Promising Green Nanomaterial

Plastic waste and its environmental repercussions have increased awareness and the development of biodegradable materials as sustainable alternatives. Global demand for renewable, non-petroleum-based products is growing due to concerns over pollution, climate change, and energy crises [1,2]. The consumer demand for natural and environmentally friendly packaging products has emphasized the need for developing materials and additives sourced from natural resources such as cellulose-based materials [3,4]. The concept of “sustainable packaging” has gained recognition in academic literature as an alternative that minimizes environmental impact and promotes circular bioeconomy principles [5,6]. A sustainable material must adhere to safety regulations, economic considerations, and quality standards throughout the product life cycle [7,8].

Lignocellulosic biomass—comprising organic plant materials like agricultural residues—offers significant potential for reuse as a high-value feedstock because of its abundance, rapid generation, and low cost [4,9]. This biomass primarily consists of varying proportions of cellulose, hemicelluloses, and lignin. Annually produced lignocellulosic biomass totals around 1011 to 1012 t [10], providing a substantial source of cellulose recognized for its biodegradability and versatility [3]. Cellulose exhibits advantageous properties such as chemical inertness, strength, low density, and surface modification capabilities [11–13], incentivizing the development of new materials [14,15]. In this context, nanotechnology could enhance bio-based materials in the forest products industry.

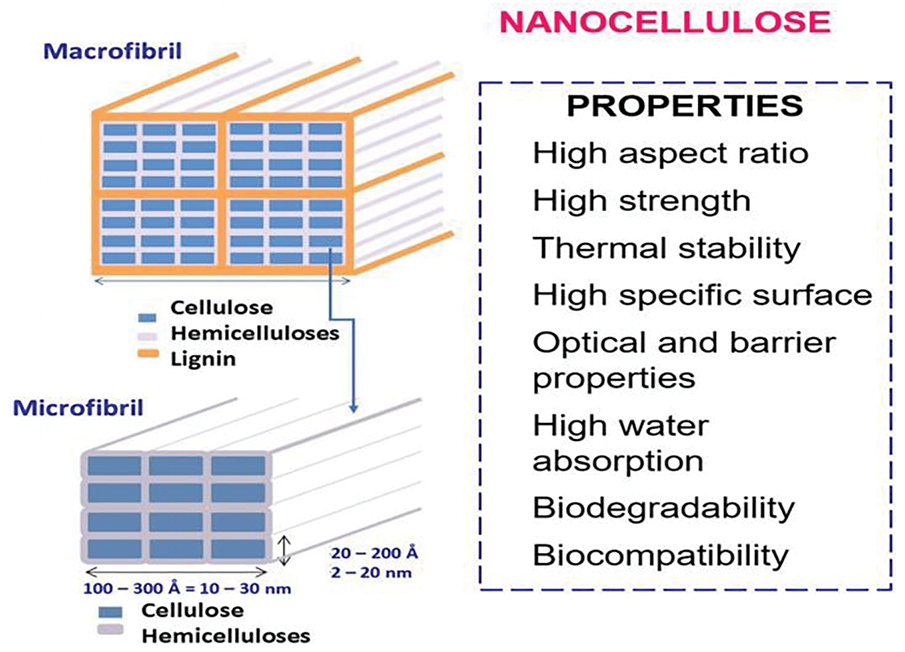

Cellulose is a lineal homopolymer with a high molecular weight composed of ß-1-4-linked D-Glucose units [1]. It is a relatively low-cost material with high availability and renewability [16]. In fiber walls, the cellulose chains form elemental fibrils, the smallest structural unit in the fiber (36 cellulose chains), which form an ordered structure of larger microfibrils surrounded by hemicelluloses and lignin. The microfibrils present crystalline and amorphous regions along its axis (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Structure of plant-derived NC and overview of its main properties. Adapted with permission of Area (2019) [17]

When talking about lignocellulosic biomass, the term nanocellulose (NC) typically involves nanoparticles of different sizes and shapes, like cellulose nanocrystals (CNC), cellulose nanofibrils (CNF), cellulose microfibril (CMF), and also the ligno-NC (LNC), which has a proportion (>1%) of residual lignin. NC can be extracted from various sources such as wood, seed fibers, sugarcane bagasse, and other types of fibers (e.g., flax, hemp), marine organisms, or algae. Although these nanomaterial types share the same chemical composition, variations arise due to differences in particle size, morphology, and crystallinity [18]. On the contrary, bacterial NC (BNC) is not derived from lignocellulose biomass but is bioengineered by specific fungi, bacteria, or invertebrates [19].

NC production begins with an initial stage where lignocellulosic or cellulosic fibers are obtained by mechanical (refining), chemical (alkaline or organosolv pulping, bleaching), biological (enzymatic), or combined treatments [20]. In subsequent stages, the obtained fibers, containing cellulose and a variable amount of lignin and hemicelluloses, are deconstructed to the nanoscale applying mechanical (nanofibril-lation by high-pressure homogenization or grinding), biological (enzymatic), chemical (TEMPO-oxidation, carboxymethylation), or a combination of these treatments. CNF is acquired through chemical, enzymatic, and (or) mechanical disintegration processes from plant-derived cellulose, whereas CNC is isolated via chemical acid hydrolysis [21].

NC exhibits distinct attributes owing to its minute size at the nanoscale (1 nm = 10−9 m), fiber structure, and expansive surface area (Fig. 1), which give it attractive properties such as high strength, stiffness, and surface area [22]. LNC retains some surface properties and interfacial interactions of lignin and has distinct applications [23].

1.2 Types and Applications of Cellulose Nanomaterials in Packaging Application

NC offers a versatile resource with multiple applications in various industries, e.g., biomedical, food engineering and packaging, cosmetics, electronic devices, environmental, civil engineering, and high-performance materials [13,20,24].

Paper and paperboard are commodities in the packaging market, constituting around 30% of the global market [25]. Paper is a cellulosic fiber network with a porous structure and hydrophilic surface, limiting its packaging applications due to reduced gas, water, and grease barrier properties. Currently, one or multiple coating layers are applied onto the paper substrates to improve barrier properties for food packaging using petroleum-based polymers or metallization as non-biodegradable layers. However, biodegradable bio-based polymers are abundant, renewable, and sustainable alternatives to conventional coating. The unique properties of nanocellulose materials have attracted significant attention in recent decades in the paper industry, evidenced by an increase in scientific publications, patents, and the upscaling activities of several companies.

NC has numerous applications in packaging products but is primarily used to reinforce polymeric matrices to create nanocomposites with enhanced mechanical properties because of its high tensile modulus, strength, surface area, aspect ratio, and good film-forming properties [21,26,27]. Despite its exceptional properties, there are still challenges, such as scaling up production, compatibility with other materials, and high manufacturing costs [28].

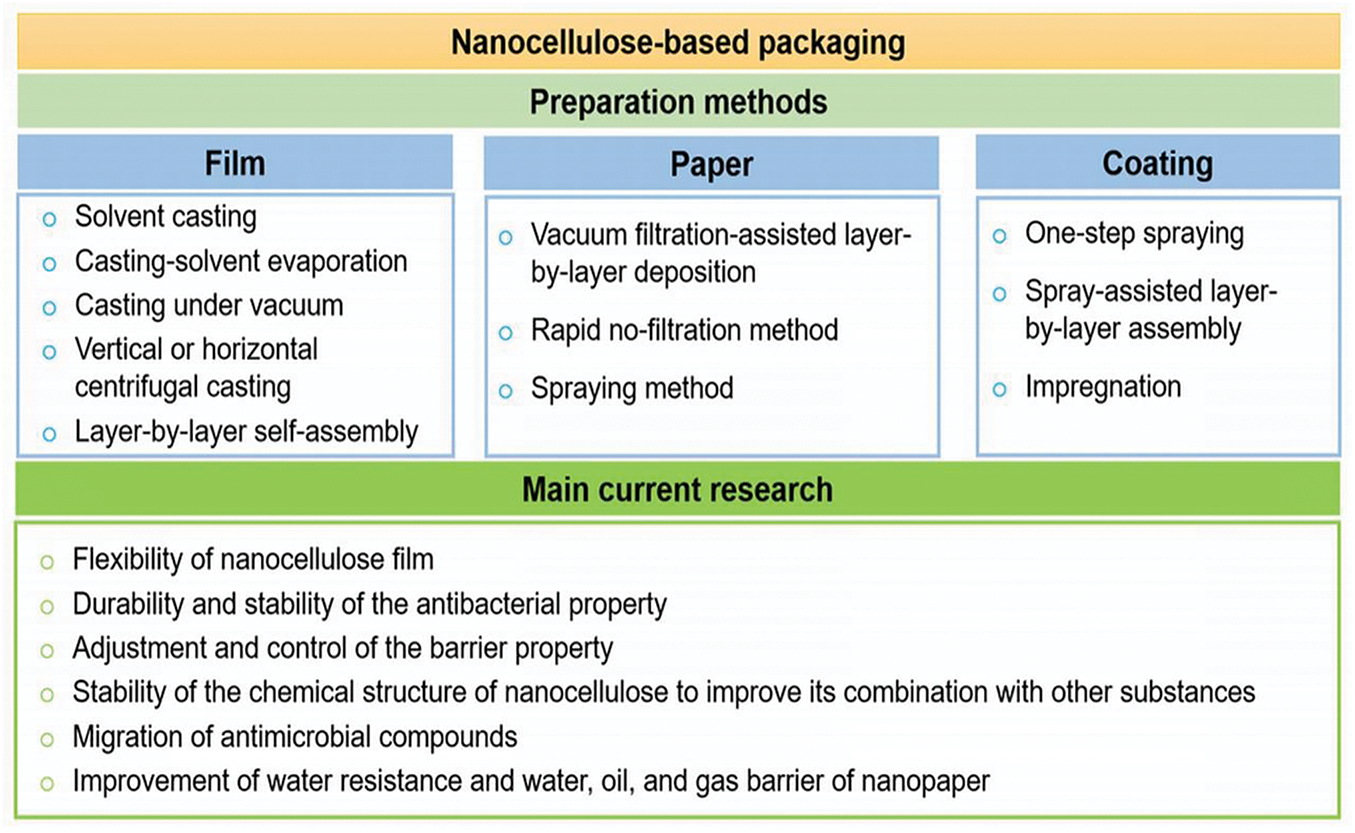

The most significant benefit of this material is that it can be obtained from renewable resources using methods that are not overly complex. However, some challenges and disadvantages still need to be addressed [29,30]. Diverse investigations have resumed these aspects, and the advantages and disadvantages in a broad context of the use of NC in this field have been published [6,31]. Nevertheless, the research on NC application in food packaging is a topic of current interest in the scientific literature. NC utilization in packaging includes films, paper, and coating. Fig. 2 presents the main preparation methods in NC-based packaging and current research on this topic.

Figure 2: Main preparation methods in NC-based packaging and current research

NC films for food packaging can be enhanced by integrating composites with materials like lignin nanoparticles, polyvinyl alcohol, chitosan, and graphene oxide to improve mechanical strength and water vapor barriers. Relevant attributes of food packaging include antibacterial and antioxidant properties, often achieved by incorporating plant-derived essential oils such as cinnamon and oregano. While these oils are effective antioxidants, they do not perform well as antibacterial agents [32]. Metallic compounds like copper can enhance antibacterial efficacy without the toxicity concerns related to silver nanoparticles [33]. Nanopapers are ultra-light, flexible, strong, and thermally stable materials produced by vacuum filtration and casting. They can be impregnated with solutions to impart antibacterial properties [34].

Currently, NC-based packaging must overcome some challenges for its market application: (i) flexibility of NC films, (ii) durability and stability of the antibacterial property, (iii) adjustment and control of the barrier property, (iv) stability of the chemical structure of NC to improve its combination with other substances, (v) migration of antimicrobial compounds, (vi) nanosafety evaluations (e.g., cytotoxicity, genotoxicity, or migration risk), (vii) compression properties and resilience of aerogel, (vii) poor water resistance and poor water, oil, and gas barrier of the nanopaper.

NC can be integrated into paper packaging as a reinforcement agent in different ways, like in bulk, as a coating, or forming nanocomposites. In bio-nanocomposites, NC improves biopolymer stiffness and tensile strength (starch, polylactic acid, polyhydroxyalkanoates, and others). Usually, an NC content of 4% of nanocomposite allows a continuous network in the biopolymer; higher content could harm the mechanical, water-vapor barrier and optical properties of the nanocomposites due to segregation (formation of OH bonds) between nanoparticles in the matrix [35].

Water vapor and oxygen barriers depend on the type of material, temperature, pressure, and relative humidity. Packaging should fulfill the moisture and oxygen transmission rate requirements for specific products. Numerous studies have shown NC as an enhancement additive of the water-vapor and oxygen barriers in paper packaging [36,37]. Other beneficial properties of adding NC to packaging have been recently developed, such as UV-barrier and antioxidant [38], active surface [39], controlled release [30], and others.

2 Scope, Objectives, and Methodology

The use of nanomaterials, their diverse applications, and the rapid advancement in nanotechnology have raised concerns about the potential effect on human and environmental health. Considering the rapid development of NC-based products and the novelty of the material, human health studies remain scarce [40]. Since new NC products are under investigation for packaging and may enter the market shortly, an extensive evaluation is necessary to ensure the human and environmental safety of the new material [41].

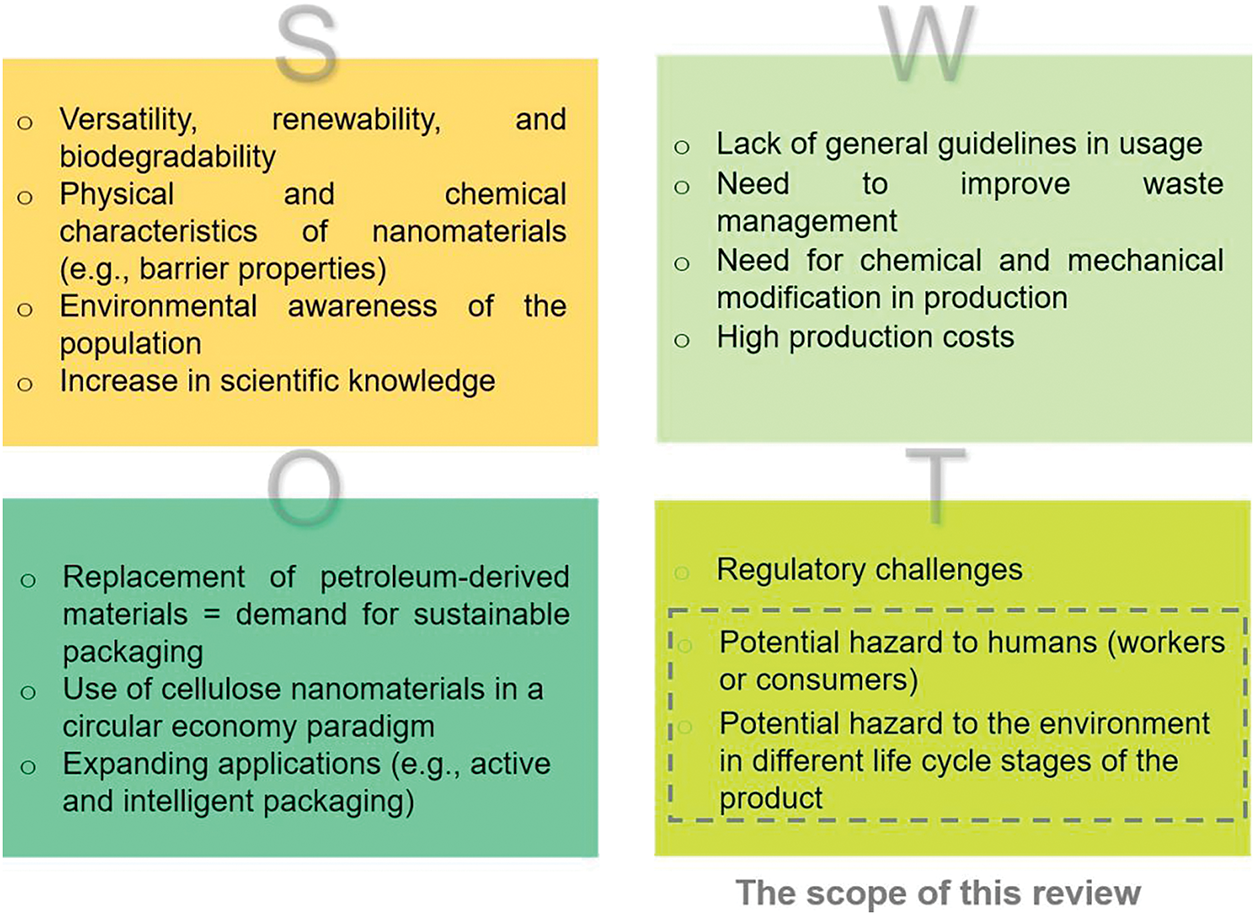

The increasing integration of nanotechnology into consumer products and medical applications requires a thorough understanding of their toxicity, particularly concerning direct human interactions through various exposure pathways. Fig. 3 shows a SWOT analysis (strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats) highlighting the relevant aspects of NC use in packaging, emphasizing the area that aligns with the scope of the review.

Figure 3: SWOT analysis, summarizing the main strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of NC-materials use in packaging, highlighting the area that aligns with the scope of this review

This review focuses on the nanosafety aspects concerning NC use, focusing on toxicity evaluation through experimental assays. Initially, it provides a comprehensive list of representative studies based on searches conducted in the Google Scholar database using the following keywords: i) Nanocellulose-toxicity-packaging applications and, ii) Cytotoxicity-in vitro assay-nanofibrillated cellulose, including review articles and relevant cytotoxicity, immunotoxicity, and genotoxicity studies to contextualize findings within a broader framework. The search was conducted for literature published between 2014 and 2025, focusing only on cellulose nanofibers (CNF) due to their potential relevance in cytotoxicity linked to fiber length [40].

Besides, it presents an overview of the nanosafety implications regarding NC, identifying existing knowledge gaps. Then, it outlines different methodologies employed to determine toxicity while discussing pertinent issues related to packaging applications. Finally, this review synthesizes key insights from the analysis while highlighting future research directions for advancing our understanding of NC toxicity, especially in packaging applications, underscoring the relevance of prioritizing safety measures to mitigate potential risks to human or ecosystem health.

3 Results of the Search and Relevant Studies

Research on the toxicity of cellulose-derived compounds has grown significantly in recent years, driven by concerns about the impacts associated with various industrial products and processes. Researchers agree that this interest arises due to a confluence of factors, including increased environmental awareness, the development of new technologies, and the emergence of regulations.

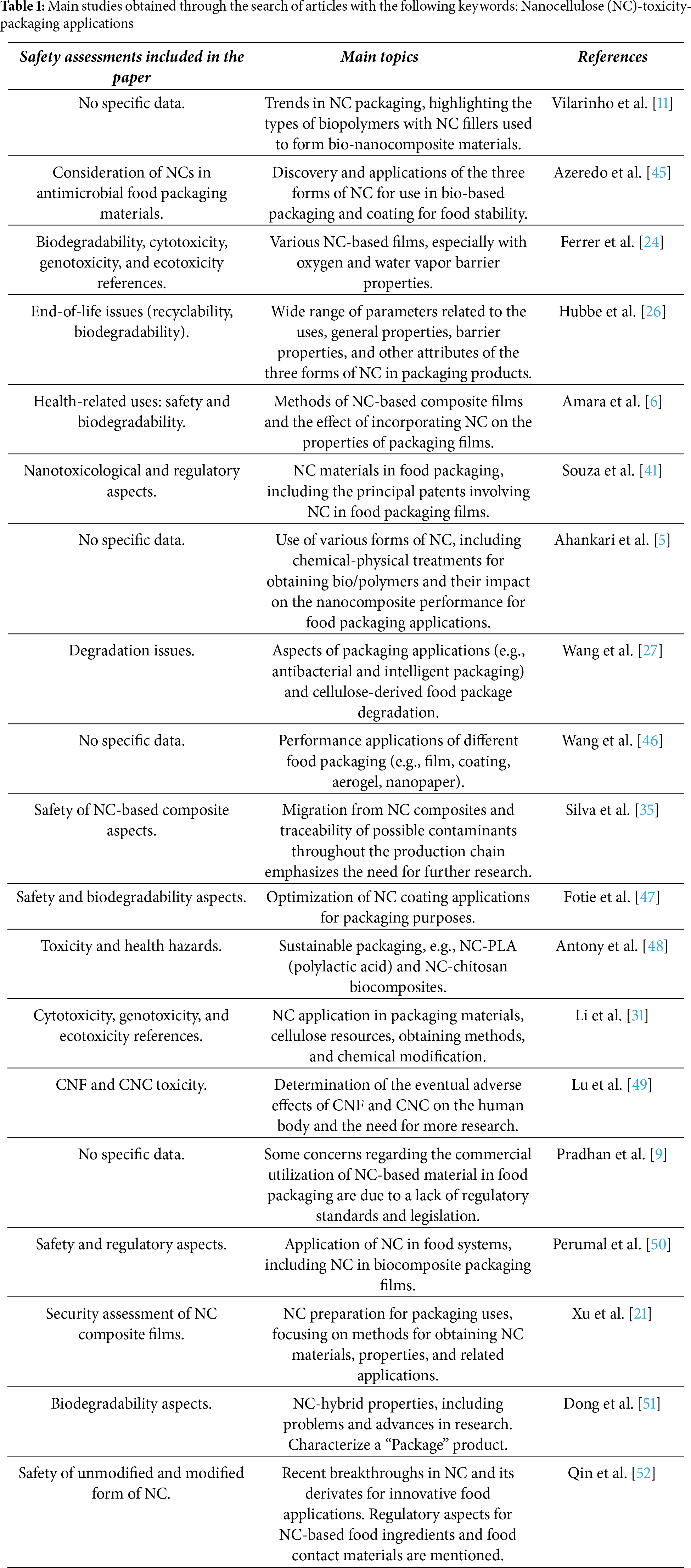

Table 1 shows the review studies obtained following the first criteria explained in Section 2. Most articles about NC packaging applications included diverse safety aspects and implications associated with these innovative materials used in food packaging, such as biodegradability and toxicity aspects (e.g., cytotoxicity, genotoxicity). The table emphasizes the features related to nanosafety included by the authors in each study and remarks on some observations considered relevant to the main topic included in each research.

Table 2 shows a selection of relevant studies following the keywords cytotoxicity-in vitro-nanofibrillated cellulose. It includes the main results and the chief findings from each study. Many of them also evaluate the effects of CNC, and some results are mentioned. The studies involve the last ten years, but NC toxicity assessments date back to the past 20 years [42–44].

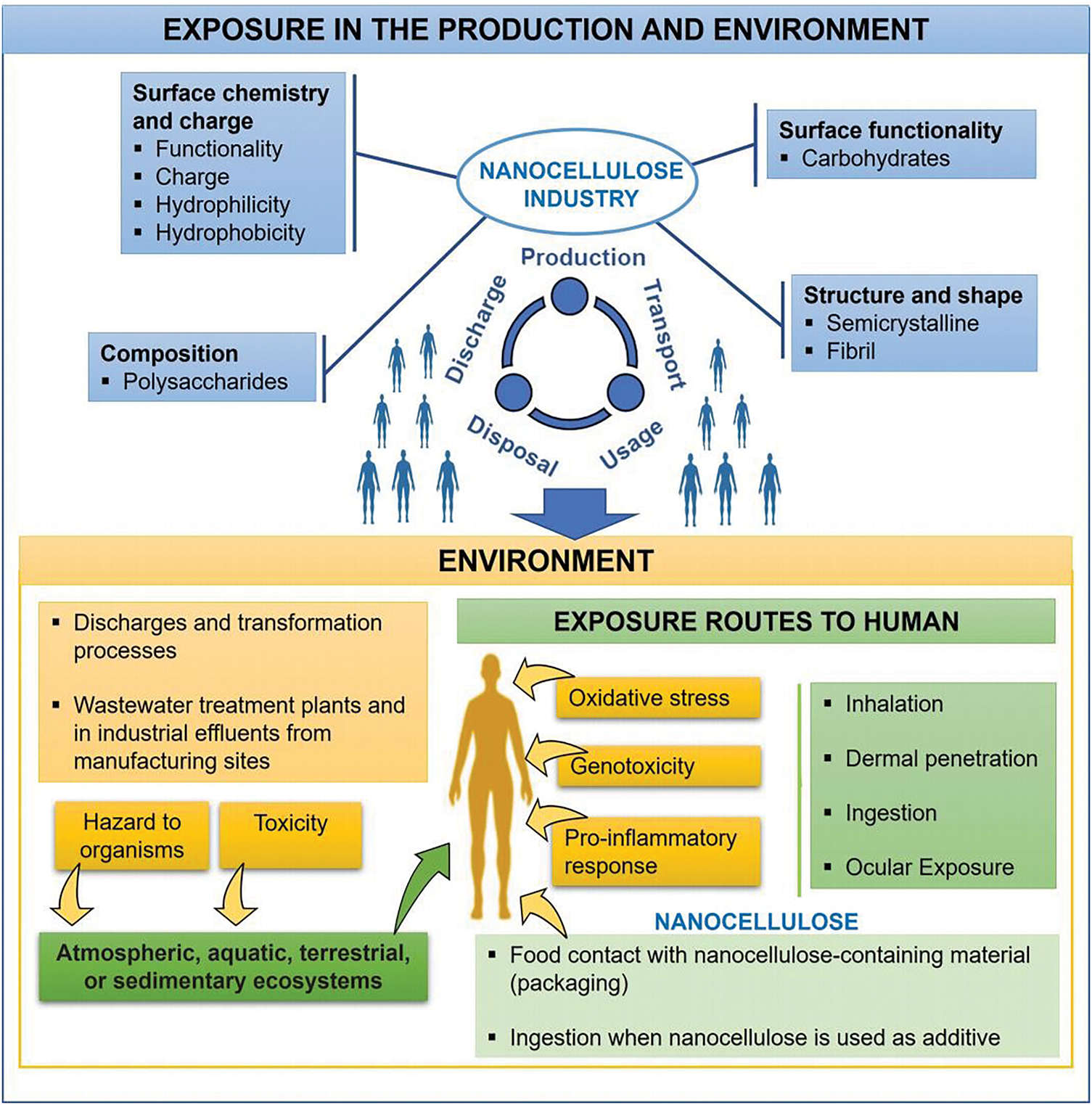

Nanotechnology is becoming one of the most relevant tools for revolutionizing food science and industry. Many aspects related to the functionality and applicability of nanotechnology in food applications are on the rise worldwide. Cellulose-based materials are often considered biocompatible and non-toxic due to their natural origin. However, their nanoscale size may confer different properties, potentially associated with toxic characteristics. A decrease in particle size is associated with a possible penetration through biological barriers (e.g., digestive mucous membranes). For this reason, NC-containing materials have not yet been authorized as food additives or for food contact (e.g., packaging in Europe) [67]. Fig. 4 shows aspects related to the potential toxicity of nanomaterials, focusing on NC considering their application in packaging and based on human and environmental protection.

Figure 4: The potential human exposure routes in the production cycle of NC materials and main aspects of human and environmental health

Due to the extensive range of NC applications and analyses of the existing literature throughout the life-cycle of human exposure routes, it is essential to identify the main human exposure routes for future research (Fig. 4). Inhalation (through the respiratory tract), dermal (through skin contact), and oral ingestions are the usual modes of human exposure [68,69]. Considering the type of applications, it is essential to investigate the possible major entry points into the human body to design future research.

Before the widespread commercialization of any product, it is crucial to detect the possible toxicological characteristics of NC to guarantee human safety. When considering its use in packaging, two aspects are relevant to nanosafety: toxicity and migration [21]. Migration refers to the transfer of substances from packaging materials into food. It plays a key role in the interaction between food products and their packaging. This interaction can occur in several ways: external migration of environmental contaminants into the food via the packaging, internal migration between different layers within the packaging material, or direct migration from the packaging into the food itself. Such processes may negatively impact the quality and safety of the food product [70,71]. In particular, the potential migration of nanomaterials is a concern when these materials are used in food-contact packaging [41]. However, reports on the migration testing necessary to ensure the safety assessment of nano-packaging materials are scarce [46,72]. Special attention should be given to migration in packaging films [21]. Table 1 shows that not all authors included tasks related to the migration process within the nanosafety aspect considered in their studies.

Evaluating cytotoxicity becomes relevant in studies of materials used in food science with applications such as food stabilizers, functional food ingredients, and food packaging [45,73]. Recent studies focus on developing active food packaging films with antimicrobial properties with NC as an additive [39,74,75]. Studies of NC as a food additive mention limited studies into the effects of NC on the gastrointestinal tract when used in food [76,77]. Long-term impacts, including effects on gut flora and nutrient absorption, require further investigation to ensure human safety [78].

An in-depth examination of research on NC toxicity has revealed a noticeable and growing body of studies [40,67,79]. However, all authors highlight the emergent nature of this field and underscore the need for further research to comprehensively understand the potential risks and implications associated with using NC in various applications. Some reviews concentrate on specific exposure routes, such as oral [67,80] or respiratory [81]. Oral or dermal exposure to CNC has demonstrated a lack of adverse health effects when compared to pulmonary toxicity [68]. Some in vitro and in vivo studies on the biological impacts of CNC and CNF concluded that they have limited toxic potential under realistic doses and exposure scenarios [79].

Manufacturers and users of NC need to stay informed about relevant regulations and guidelines, conduct appropriate risk assessments, and ensure compliance with applicable safety standards. CNF, CNC, and BNC have no specific directives for production and use as food ingredients [77] and have not yet been approved for food contact by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA). In the European Union, the Registration, Evaluation, Authorization, and Restriction of Chemicals (REACH) regulates the risks associated with chemicals or new substances to human health and the environment. REACH places responsibility on manufacturers and importers to ensure the safety of the substances they produce or bring into the Euro-pean market [82]. The European Commission has published extensively on specific requirements for nanoforms of materials, including technical reports and guidance on the implementation of these recommendations [83–85]. Several reviews have also been published recently on guidance on risk assessment of nanomaterials in the food and feed chain [86,87].

Although cellulose and derivates are considered safe, specific considerations may arise depending on the NC size, shape, surface chemistry, and intended use. It was suggested that bulk and nano forms of a material with the same chemical composition could be treated as the same substance in the context of REACH [88]. However, nanomaterials necessitate specific regulatory measures due to their unique physicochemical properties and potential associated risks. The safety of products containing NC should be analyzed case-by-case, considering the particular type of NC, potential exposure routes, and other relevant factors. NC has not yet been approved for food contact applications [52].

In the European Union and The United States, the specific exposure metrics for NC remain to be defined. China is engaged in the regulation of nanomaterials through the National Medical Products Administration (NMPA) and the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE). There is agreement that currently available toxicity data are insufficient to determine the harmful consequences of NC oral exposure to humans [80].

On the other hand, there is a lack of information about the NC Occupational Exposure Limits Value (OEL) via inhalation or dermal exposure due to the small amount of data available regarding its risks [40,89,90]. Based on the precautionary principle, the 8-h OEL value has been suggested to be 0.01 fibers/cm–3, the same as carbon nanofibers, due to the potential biopersistence of NC when inhaled [40,90].

The European Commission recently recommended a guide on the Safe and Sustainable-by-Design (SSbD) as a framework and criterion for design processes of chemicals and materials safe for human health and the environment with a sustainable life cycle [91,92]. The dimensions considered by the SSbD include health and environmental safety while also reflecting contemporary economic and social contexts.

Skin cosmetics products that include NC as a filler in their formulations currently researched by SSbD should agree with the REACH regulation [92,93].

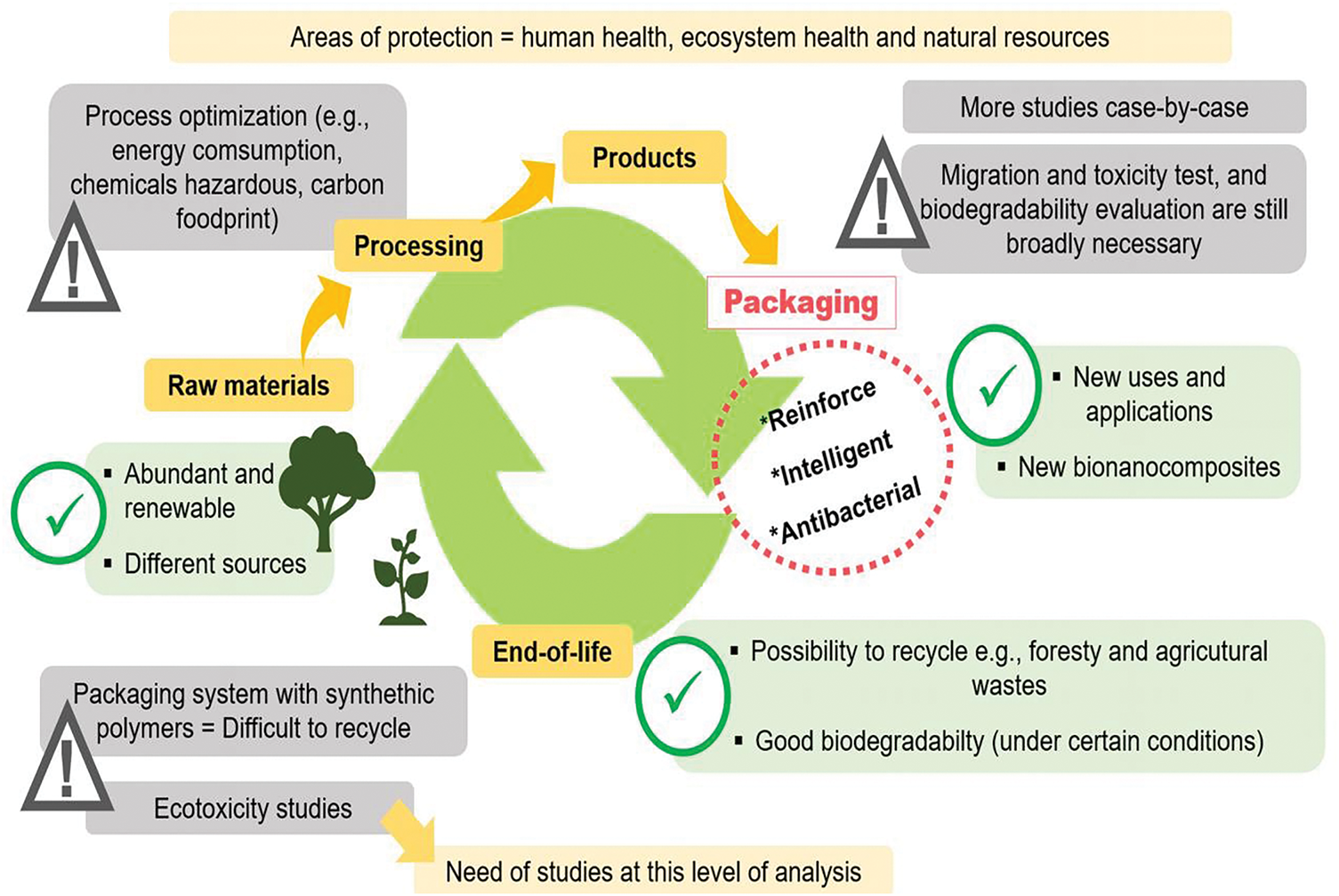

Finally, a thorough understanding of the life cycle of a nanomaterial is imperative to comprehensively assess the potential risks to human health and the environment, adopting a holistic perspective [92]. The life cycle encompasses various stages, starting from the initial production and manufacturing processes, extending through transportation, consumer utilization, and concluding with disposal methods or end-of-life [79]. Examining these stages is crucial for identifying and evaluating potential hazards, exposure pathways, and environmental impacts related to the entire life cycle of NC-associated materials. This holistic approach ensures a more robust and accurate assessment of the overall risk profile, facilitating the development of effective risk management strategies and informed decision-making. A recent review examining various aspects of NC production processes and life cycle assessments highlights key areas impacting the environmental performance of NC while also addressing considerations related to the end-of-life phase of the products [94]. The life cycle risk assessment (LCRA) is a methodology that identifies several stages during any manufactured nanomaterial life cycle. This method identifies and assesses potential risks from occupational, consumer, and environmental exposure throughout the product life cycle [95]. Fig. 5 summarizes the main aspects of each criterion considered in the LCRA and SSbD of NC.

Figure 5: Analysis of steps included in the Safe and Sustainable-by-Design and the Life Cycle Risk Assessment of NC use for packaging applications, including positive and negative aspects and alert claims in each step

The SSbD and life cycle analysis of products derived from NC should be optimized for cradle-to-gate and cradle-to-grave assessments. Some strategies have been proposed for reducing energy demand and developing a low-carbon economy for the products. Currently, only laboratory data are available, so it is necessary to evaluate this process at the industrial level to assess the environmental impact of cellulose products on various aspects, such as air emissions, human health, and waste discharge. Among the final disposal options for these products (e.g., reuse, landfilling, recycling, combustion, storage), there is no data on the potential effects of each process. So, it is relevant to investigate and predict environmental consequences [96]. Furthermore, there is advice about the need for reagents used in cellulose and NC extraction process optimization to avoid environmental damage [27].

4.2 CNF Toxicity in Packaging Use

A considerable body of research supports the notion that wood-based nano-sized materials like NC, in various forms, are generally safe or non-toxic to humans [40,79]. However, due to their different characteristics, toxicity testing results are considered valid only within the specific context of each cellulose material, which has to be assessed case by case [55]. Factors such as particle size, shape, surface chemistry, and the biological model employed can influence the toxicity profile of nanomaterials [97,98]. Concerning size, most researchers indicate that smaller size (<50 nm) nanomaterials can produce severe nanotoxicity compared to bigger sizes (>50 nm) [98]. For a full toxicity assessment, it is essential to incorporate a comprehensive morphological characterization of nanomaterials using available instruments and methods (e.g., TEM, AFM), including a multi-scale characterization in which the authors can assess key physicochemical properties like size, shape, aspect ratio, surface area, agglomeration state.

Some factors, like the physicochemical features of the nanomaterial, e.g., thickness and length, as well as biopersistence, are determinants in the toxicity evaluations of CNF [19,56,99] (Fig. 6). CNFs have a long, entangled fibrous structure with a high aspect ratio and lower crystallinity [52]. The fiber paradigm has been adapted to evaluate the toxicity of high aspect ratio nanomaterials such as asbestos fibers. This model emphasizes factors like nanoscale dimension with a high length-to-diameter ratio, and biopersistence in biological environments, which can potentially affect the induction of chronic inflammation and fibrosis due to the incapacity of macrophages to phagocyte them [100].

Figure 6: Featured considerations on CNF toxicity for its use in packaging

Furthermore, as with other types of nanoparticles, it is essential to develop comprehensive strategies, including the optimization and standardization of safe and efficient synthesis protocols, identification and validation of sensitive and specific biomarkers of nanotoxicity, and development of protective measures for workers involved in the production and application [101]. For example, some pretreatments applied before NCF fibrillation (e.g., carboxymethylation and TEMPO-mediated oxidation) can influence their biological interaction and effects [67]. Aimonen et al. [56] highlight that few studies compare the toxicity of CNFs derived from the same resource but with different surface chemistry. Fig. 6 mentions the main determining factors and assessments for CNF toxicity analysis.

Upon contact with biological systems, CNFs can interact with cellular membranes and internalize through endocytic pathways, potentially leading to the generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), lysosomal destabilization, and the activation of pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, all of which are mechanisms commonly associated with nanomaterial-induced toxicity. Overall, according to the main exposure way (Fig. 6), it is expected that the effect on the respiratory system is mainly manifested in oxidative stress, inflammation, epithelial damage, and genetic changes [102]. Considering oral exposure, CNFs can interact with the gastrointestinal tract, causing local inflammation, disruption of epithelial integrity, and gut microbiota disruption.

Assessing regulatory considerations is crucial before integrating NC into the food sector for NC-based materials commercialization. Food packaging materials must meet stringent requirements to protect and preserve food quality and safety. Even without a specific section about nanomaterials safety, all references follow the paradigm of sustainable packaging, indicating that the nanomaterials used for this application should not only consider safety during their use but also in their storage, transportation, market, and other options during their life cycle [5,27]. A recent study proposed that future packaging materials should incorporate essential attributes summarized by the acronym “PACKAGE”: Property, Application, Cellulose, Keen, Antipollution, Green, and Easy [51]. The significance of PACKAGE lies in its potential to address the critical issues associated with traditional, non-degradable plastic packaging.

On the other hand, environmental issues are a chief part of a safety evaluation but remain poorly studied [90]. Table 1 shows that while many studies focus on safety implications such as biodegradability and toxicity, few address environmental factors such as ecotoxicity evaluations, a relevant assessment of the packaging utilization, and their end-of-life options [26].

In the packaging field, there is an increasing focus on nanocomposites. These innovative materials involve NC integrated with different substances to enhance and tailor specific properties. This combination allows for advanced packaging solutions that offer improved mechanical strength, barrier properties, and sustainability, aligning with the growing demand for eco-friendly and high-performance packaging materials. Some studies conclude that their toxicological aspects evaluation (e.g., cytotoxicity) is still incipient [48,52].

Incorporating reinforcing agents into biopolymers involves chemical and structural features that enable their commercial application [5,48,103]. Biodegradable polymers such as Polylactic Acid (PLA) and polyhydroxyalkanoate (PHA) have potential applications in food packaging and the potential to replace conventional plastics [31,104]. Other materials like chitosan, which has antimicrobial properties, or proteins obtained from animals and vegetables, can be modified and processed to complement packaging and provide greater barrier capacity [48]. There are abundant references regarding its uses, properties, and preparation methods [21,72]. Surface modification of NC can impart new beneficial properties, increasing their applicability. However, different functionalizations will determine differences in physical and chemical parameters (aggregation rate, hydrophobicity, surface charge, surface chemistry) and could also cause an impact on biological responses [19]. Some modifications of NC could make it less biodegradable or non-biodegradable or result in toxic or dangerous compounds [47].

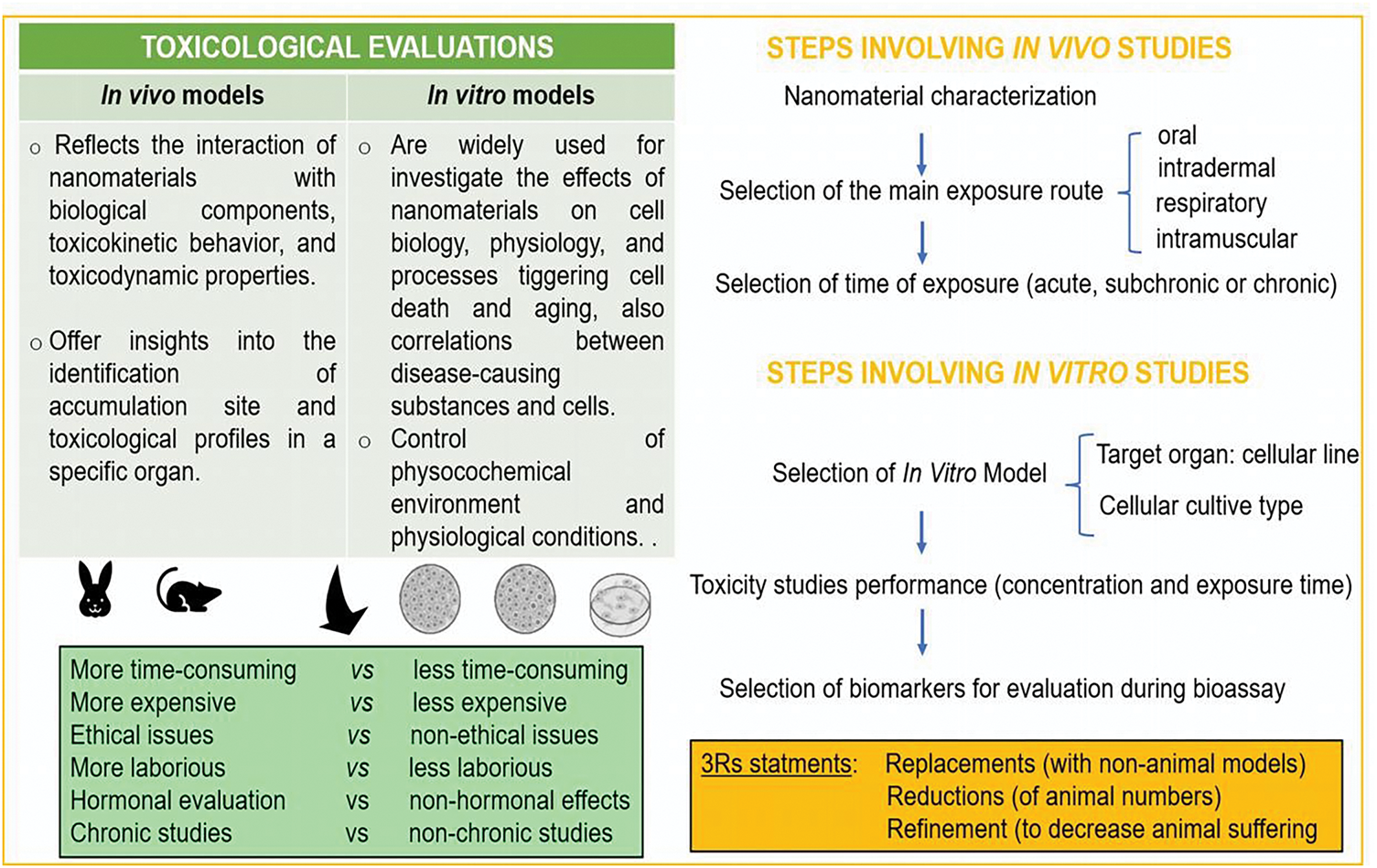

4.3 3Rs Statement in Toxicological Evaluation

Nanotoxicology studies the toxicity caused by nanomaterials and become an emerging field of research. The assessment of these compounds relies on toxicological studies. They can use either in vitro models, where biological experiments occur in an artificial environment such as a test tube, or in vivo studies, where biological experiments use whole animal systems as the route of exposure and for evaluating effects [105]. There are fewer in vivo investigations than in vitro ones [40]. Generally, in vitro assessments are less mandatory than in vivo studies to identify potential clinical trials in humans, but both are complementary. Also, given the recent emphasis on refining and reducing animal-based testing strategies, with the eventual goal of phasing them out over time, there is an urgent need to develop alternative testing models, e.g., in silico models.

Nowadays, the principles of the 3Rs implicate new alternative methods, which are emerging as trending topics in future investigations [106]. These approaches, which center on reduction, refinement, and replacement, seek to meet scientific goals while reducing the number of animals used in research. Fig. 7 presents an overview of the main aspects of the different testing models.

Figure 7: Key aspects of usual methods in toxicological evaluation in agreement with the 3Rs statement

Computer simulations, which rely on in silico testing models, offer an alternative to complement experimental approaches [107,108]. However, it presents some difficulty in predicting the consequences of the interaction between nanomaterials and living matter [77].

The in vitro triculture small intestinal epithelial model is a methodology that provided substantial information on the potential cellular responses to ingested NC under relevant physiological conditions, as demonstrated by Cao et al. [109], and is likely to determine nano-bio interactions [110,111]. Multidimensional cellular models such as co-cultures and 3D cultures can help to enhance the reliability of hazard evaluation of CMs and their potential risk to human health. This type of study is relevant in future investigations about NC applications in the food industry and their implications for human health.

The cytotoxicity, which can be analyzed in vivo and (or) in vitro studies, involves enzymatic activity leaked from the damaged cells or using stains that only remark the damaged cells as an indicator through microscopic examination [105]. Results of cytotoxicity, viability, and impact on mammalian cell morphology seem to be prevalent in the current literature [109,111,112]. For a proper results interpretation, it is crucial to consider exposure systems (cell types), dosage, and NC type/treatment/origin and ensure a clear and thorough material characterization. Cytotoxicity is also a parameter with conflicting conclusions [68,90]. The subsequent part of this review shows a selection of relevant studies on this subject.

Most outcomes concerning cytotoxicity, viability, and the impact on mammalian cell morphology that appear widespread in the current literature are benign [44,82]. The selection of the cell type for the assays depends on the toxicity of toxicants on the organ because each cell type has its function, responding in diverse ways to exposure to a specific nanomaterial [97,113].

The cytotoxic and genotoxic evaluations are necessary due to their association with carcinogenic effects. Nanomaterials can potentially induce genotoxic damage by direct interaction with DNA, by disturbing the process of mitosis, or by inducing reactive oxygen species production. When choosing an appropriate set of in vitro genotoxicity tests, the three chief endpoints are gene mutation, structural chromosome aberrations, and numerical chromosome aberrations [114]. Some evaluation methods used are Comet Assay, Micronucleus Assay, Chromosome Aberration Assay, and Ames Test, which are widely used in toxicological studies [115]. Finally, multiple endpoints and multiple cell types are preferred in laboratory studies to avoid false-negative results. Regarding genotoxicity tests, there are also evident discrepancies in the findings, as shown in Table 2 and described below.

Less addressed in the literature, immunotoxicity evaluates the effect of NC on the immune system. The biocompatibility of NC is related to monocyte/macrophage system response, so several in vitro model systems are used to delineate this interaction [16]. Most studies used mouse and human monocyte-derived macrophages [116,117]. Lopes et al. [62] assume that the inflammatory responses to CNF presence are due to material surface chemistry, thereby opening the possibility of designing safer materials. Despite some studies not evidencing inflammatory effects or cytotoxicity, contradictory effects highlight the need for additional evaluation, so inflammation as an immune defense mechanism requires further research [44].

The ecotoxicity evaluation of nanomaterials, relevant when using NC in packaging [118], is crucial for understanding their potential impact on individual organisms and entire populations [119]. These assessments employ various organisms suitable for simple and rapid ecotoxicity testing, with a recent trend toward reducing the use of vertebrate organisms. Ecotoxicity tests serve as tools to assess the risks associated with potential releases into the environment. Methods for evaluating the ecotoxicity of nanomaterials follow standardized tests outlined by organizations such as the OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, ISO (International Organization for Standardization, EPA (United States Environmental Protection Agency) [120,121]. Boros and Ostafe [119] conducted a comprehensive review, highlighting commonly used organisms in ecotoxicological studies for assessing nanomaterial toxicity, which includes relevant criteria for selecting testing methods, descriptions of each organism, and the advantages and disadvantages of using them as a bioindicator.

The results obtained by the authors show a variety of responses for each biomarker (Table 2). Their interpretations do not allow for general assumptions necessary to achieve overall nanosafety. Even if the results vary, cytotoxicity seems not to be a result of the direct action of CNF on cells but rather due to secondary factors like endotoxin contamination, microbial contamination, adsorption of culture medium components to CNF, and aggregation or agglomeration and dispersion states of CNF [122]. The agglomeration is a common factor observed in related studies because it can alter the effective surface area and influence cellular uptake, potentially leading to misleading toxicity assessments.

The role of the size and shape of nanomaterials in the interaction with the gastrointestinal tract should be studied more to understand the potential for intestinal barrier dysfunction and its implications for ingestion [58]. The metabolic activity and integrity of Caco-2 cells could not be affected by CNF materials, even with different surface modifications. Although some concentration-dependent growth inhibition of E. coli could be observed when exposed to CNF materials, this was not the case for L. reuteri (Table 2). The bacterial growth in the gastrointestinal tract is an indicator of oral toxicity of CNF, and any changes in the gut microbiota have been related to gastrointestinal disease [59]. Furthermore, the size of nanomaterials plays a critical role in their interaction with the gastrointestinal tract. Continued research is needed to understand how cellulose nanofiber (CNF) materials affect gut microbiota and intestinal cells. These interactions must be thoroughly examined when nanomaterials are intended for use in food-related products.

The phagocytosis or internalization of nanomaterial by a cell has a significant implication for both the cellular health and the biological fate of the material (e.g., biodistribution, degradation, and long-term accumulation within tissues). Menas et al. [53] found that CNC but not CNF particles were taken up by the cells. In other studies, the CNF uptake by cells occurs [56,66]. The last authors indicate that the chemical modifications of CNF and the fibrillation method employed can modify the direct contact with cells. Using TEM, Pinto et al. [57] detected phenotypic cellular changes (e.g., cytoplasmic or endocytic vacuoles presence, binucleation) in the exposed cells, providing evidence of particle internalization. Pitkänen et al. [55] selected the two finest CNF fractions (<10 µm) and reported no significant cytotoxic effects. Although many indicators suggest that the toxicity of nanofibers may be associated with their morphological characteristics, the specific molecular mechanisms underlying this toxicity still need to be elucidated.

Regarding cytotoxicity results, the cellular responses are diverse, highlighting the importance of validating the toxicity results only for the tested material, considering the structure, properties, and preparation methods. Some studies show signs of cytotoxicity demonstrated by some of the used biomarkers (Table 2) [53–55]. Conversely, other authors found non-cytotoxic effects nor oxidative stress [60,61,123].

Moreover, the human cell types chosen in each study are those most likely to be affected by potential exposure to CNF in occupational settings or by consumers [62]. They included immune surveillance cells and epithelial cells lining the skin and respiratory system, representing those most likely to be impacted by exposure routes to CNF [66].

Some authors indicate cytotoxic and genotoxic effects demonstrated by the exposure to CNF and CMF using different biomarkers [54,57,63]. The authors also suggested that differences in the DNA damage response of specific cell models highlight the importance of cellular models in genotoxicity studies. Some studies employ co-culture models, which are more realistic than monoculture [54,124] and also reveal different effects based on physicochemical properties. Likewise, a significant increase in micronucleated binucleated cells was induced by cellulose microfibrils produced by enzymatic hydrolysis [57]. Another critical task from this study is that CNC, unlike fibers, is not internalized into cells. The last authors also stated that the toxicity of the different cellulose nanomaterials (fibrils vs. crystals) is not comparable due to the distinct raw material origin, isolation techniques, processing/manufacturing techniques, drying processes, and others. This assessment is also supported by Menas et al. [53]. The potential for low CNF concentrations to induce cell overgrowth and genotoxicity raises significant concerns regarding occupational exposures and their implications for human health risk assessment [54]. The need for further studies targeting other genotoxic endpoints and cellular and additionally delving into cellular and molecular mechanisms are emphasized by Pinto et al. [57].

The exposure time is an additional parameter to consider. The consulted studies use short exposures for cell viability determination. So, there is a need for toxicological studies that use longer exposure times and encompass the low-dose range typically applied to in vitro studies [54]. Chronic studies have elucidated that cellulose fibers persist in rat lungs even after a year of exposure, suggesting the biodurability of these particles [125]. This finding highlights the need for long-term assessments in toxicological research to comprehensively understand the potential health implications associated with exposure to such materials over extended periods.

Several in vivo studies suggested the potential impact of NC aspiration on acute inflammatory responses and DNA damage at the pulmonary level, as detected in female rats [126]. However, other in vitro and in vivo assays demonstrated neither cytotoxic nor genotoxic effects [64]. Numerous live studies can serve as anchor points to confirm its effects or cellular mechanisms of action. They offer valuable insights into how these materials interact with biological systems, influencing cellular absorption, interaction with cell membranes, and with subcellular components [81].

4.4 Gaps in the Knowledge and Need for Future Studies

When considering CNF for food-related applications, oral exposure becomes crucial to evaluate [59]. Studies have highlighted the need for further investigation into potential adverse health effects, such as immunotoxicity and genotoxicity, after oral exposure to NC [58,80]. Before concluding that any material is completely safe for applications such as packaging, the biodegradability aspects, potential migration, toxicity, and environmental impact (ecotoxicity) must be thoroughly clarified.

Several relevant points emerge following the completion of the review that we consider relevant to indicate: 1) It is imperative to include an exhaustive characterization of the study material, providing a solid foundation for subsequent analyses and interpretations; 2) Apply a broad array of parameters (biomarkers) to evaluate during in vitro studies, prioritizing those most relevant to our specific research objectives. The same applies to the cell type and cultivation methods, which should be carefully chosen for the exposure mechanism under investigation and those expected to generate a response; 3) Recognizing that the toxicity of individual materials differs from that of bionanocomposites is a relevant area for future research; 4) Use the information provided by available in vivo studies to enhance the interpretation of in vitro results that offer valuable insights into cellular mechanisms and responses.

Although there is a tendency to prefer biobased materials over traditional petroleum-based ones, there is disagreement about whether NC’s broad use is safe. Addressing concerns about its environmental and toxicological impact is critical to ensure a safe integration in various applications without compromising consumer health or ecological integrity. Evaluating the nanosafety of cellulose nanofibers in packaging must account for key factors such as biodegradability, migration into food products, and overall toxicity. Due to the lack of consistent toxicological data supported by international regulations, the safety of the exposure or ingestion of CNF because of its presence in packaging is still an open question. Despite the increasing research in this field in recent years, the number of available studies is limited, particularly given the variety of nanomaterials emerging in the market. The risks associated with the exposure or ingestion of cellulose nanofibers require focused investigation, as current knowledge remains limited. Comprehensive research is needed to clarify the potential toxicological mechanisms of NC and its derivatives, including NC-based bio-nanocomposites, which may exhibit distinct properties compared to individual components.

Acknowledgement: Not applicable.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by General Secretariat of Science and Technology, National University of Misiones (SGCyT-UNaM), grant number: 16/Q2384-PI.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm their contribution to the paper as follows: conceptualization: Lucila M. Curi and Maria E. Vallejos; writing—original draft: Lucila M. Curi; supervision: Maria C. Area; writing—review & editing: Lucila M. Curi, Maria E. Vallejos and Maria C. Area; funding acquisition: Lucila M. Curi, Maria E. Vallejos and Maria C. Area. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The data reviewed are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0069/s1.

References

1. Trache D, Tarchoun AF, Derradji M, Hamidon TS, Masruchin N, Brosse N, et al. Nanocellulose: from fundamentals to advanced applications. Front Chem. 2020;8:392. doi:10.3389/fchem.2020.00392. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

2. Dhali K, Ghasemlou M, Daver F, Cass P, Adhikari B. A review of nanocellulose as a new material towards environmental sustainability. Sci Total Environ. 2021;775:145871. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.145871. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

3. Nechyporchuk O, Belgacem MN, Bras J. Production of cellulose nanofibrils: a review of recent advances. Ind Crops Prod. 2016;93:2–25. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.02.016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Pennells J, Godwin ID, Amiralian N, Martin DJ. Trends in the production of cellulose nanofibers from non-wood sources. Cellulose. 2020;27(3):575–93. doi:10.1007/s10570-019-02828-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Ahankari SS, Subhedar AR, Bhadauria SS, Dufresne A. NC in food packaging: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2021;255:117479. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.117479. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

6. Amara C, El Mahdi A, Medimagh R, Khwaldia K. NC-based composites for packaging applications. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2021;31:100512. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2021.100512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Pauer E, Wohner B, Heinrich V, Tacker M. Assessing the environmental sustainability of food packaging: an extended life cycle assessment including packaging-related food losses and waste and circularity assessment. Sustainability. 2019;11(3):925. doi:10.3390/su11030925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Boz Z, Korhonen V, Sand CK. Consumer considerations for the implementation of sustainable packaging: a review. Sustainability. 2020;12(6):2192. doi:10.3390/su12062192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Pradhan D, Jaiswal AK, Jaiswal S. NC based green nanocomposites: characteristics and application in primary food packaging. Food Rev Int. 2023;39:7148–79. doi:10.1080/87559129.2022.2143797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

10. Phuong HT, Thoa NK, Tuyet PTA, Van QN, Hai YD. Cellulose nanomaterials as a future, sustainable and renewable material. Crystals. 2022;12(1):106. doi:10.3390/cryst12010106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Vilarinho F, Sanches Silva A, Vaz MF, Farinha JP. NC in green food packaging. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2018;58:1526–37. doi:10.1080/10408398.2016.1270254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

12. Gopi S, Balakrishnan P, Chandradhara D, Poovathankandy D, Thomas S. General scenarios of cellulose and its use in the biomedical field. Mater Today Chem. 2019;13:59–78. doi:10.1016/J.MTCHEM.2019.04.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

13. Köse K, Mavlan M, Youngblood JP. Applications and impact of NC based adsorbents. Cellulose. 2020;27:2967– 90. doi:10.1007/s10570-020-03011-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Aziz T, Li W, Zhu J, Chen B. Developing multifunctional cellulose derivatives for environmental and biomedical applications: insights into modification processes and advanced material properties. Int J Biol Macromol. 2024;278:134695. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2024.134695. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

15. Dang X, Li N, Yu Z, Ji X, Yang M, Wang X. Advances in the preparation and application of cellulose-based antimicrobial materials: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;342:122385. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2024.122385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

16. Čolić M, Tomić S, Bekić M. Immunological aspects of NC. Immunol Lett. 2020;222:80–9. doi:10.1016/j.imlet.2020.04.004. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

17. Area MC. Fibras. Estructura y topoquímica. In: Area MC, Vallejos ME, editors. Nanocelia-producción y usos de la celulosa nanofibrilada y microfibrillada; 2019. p. 20–35. [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://repositoriosdigitales.mincyt.gob.ar/vufind/Record/CONICETDig_ca231d6f86b3aea3980da865a387649f. [Google Scholar]

18. Phanthong P, Reubroycharoen P, Hao X, Xu G, Abudula A, Guan G. NC: extraction and application. Carbon Resour Convers. 2018;1(1):32–43. doi:10.1016/j.crcon.2018.05.004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Ventura C, Pinto F, Lourenço AF, Ferreira PJT, Louro H, Silva MJ. On the toxicity of cellulose nanocrystals and nanofibrils in animal and cellular models. Cellulose. 2020;27:5509–44. doi:10.1007/s10570-020-03176-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

20. Thomas B, Raj MC, Athira BK, Rubiyah HM, Joy J, Moores A, et al. NC, a versatile green platform: from biosources to materials and their applications. Chem Rev. 2018;118(24):11575–625. doi:10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00627. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Xu Y, Wu Z, Li A, Chen N, Rao J, Zeng Q. Nanocellulose composite films in food packaging materials: a review. Polymers. 2024;16(3):423. doi:10.3390/polym16030423. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

22. Tofanica B-M, Mikhailidi A, Fortună ME, Rotaru R, Ungureanu OC, Ungureanu E. Cellulose nanomaterials: characterization methods, isolation techniques, and strategies. Crystals. 2025;15(4):352. doi:10.3390/cryst15040352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Yang X, Biswas SK, Han J, Tanpichai S, Li M, Chen C, et al. Surface and interface engineering for nanocellulosic advanced materials. Adv Mater. 2021;33(28):e2002264. doi:10.1002/adma.202002264. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Ferrer A, Pal L, Hubbe M. NC in packaging: advances in barrier layer technologies. Ind Crops Prod. 2017;95:574–82. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.11.012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Adibi A, Trinh BM, Mekonnen TH. Recent progress in sustainable barrier paper coating for food packaging applications. Prog Org Coat. 2023;181:107566. doi:10.1016/j.porgcoat.2023.107566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Hubbe MA, Ferrer A, Tyagi P, Yin Y, Salas C, Pal L, et al. NC in packaging. BioRes. 2017;12(1):2143–233. doi:10.15376/biores.12.1.2143-2233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Wang J, Han X, Zhang C, Liu K, Duan G. Source of NC and its application in nanocomposite packaging material: a review. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(18):3158. doi:10.3390/nano12183158. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

28. Elfaleh I, Abbassi F, Habibi M, Ahmad F, Guedri M, Nasri M, et al. A comprehensive review of natural fibers and their composites: an eco-friendly alternative to conventional materials. Results Eng. 2023;19:101271. doi:10.1016/j.rineng.2023.101271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Jadaun S, Sharma U, Khapudang R, Siddiqui S. Biodegradable NC reinforced biocomposites for food packaging—a narrative review and future perspective. J Water Environ Nanotechnol. 2023;8:293–319. doi:10.22090/jwent.2023.03.008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. de Carvalho APA, Értola R, Conte-Junior CA. NC-based platforms as a multipurpose carrier for drug and bioactive compounds: from active packaging to transdermal and anticancer applications. Int J Pharm. 2024;652:123851. doi:10.1016/j.ijpharm.2024.123851. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Li F, Mascheroni E, Piergiovanni L. The potential of NC in the packaging field: a review. Pack Technol Sci. 2015;28:475–508. doi:10.1002/pts.2121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Casalini S, Baschetti MG, Cappelletti M, Guerreiro AC, Gago CM, Nici S, et al. Antimicrobial activity of different NC films embedded with thyme, cinnamon, and oregano essential oils for active packaging application on raspberries. Front Sustain Food Syst. 2023;7:117479. doi:10.3389/fsufs.2023.1190979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zhong T, Oporto GS, Jaczynski J, Jiang C. Nanofibrillated cellulose and copper nanoparticles embedded in polyvinyl alcohol films for antimicrobial applications. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:456834. doi:10.1155/2015/456834. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Liu W, Liu K, Du H, Zheng T, Zhang N, Xu T, et al. Cellulose nanopaper: fabrication, functionalization, and applications. Nanomicro Lett. 2022;14:104. doi:10.1007/s40820-022-00849-x. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Silva FAGS, Dourado F, Gama M, Poças F. NC bio-based composites for food packaging. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(10):1–29. doi:10.3390/nano10102041. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

36. Shanmugam K, Doosthosseini H, Varanasi S, Garnier G, Batchelor W. NC films as air and water vapour barriers: a recyclable and biodegradable alternative to polyolefin packaging. Sustain Mater Technol. 2019;22:e00115. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2019.e00115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Pasquier E, Mattos BD, Koivula H, Khakalo A, Belgacem MN, Rojas OJ, et al. Multilayers of renewable nanostructured materials with high oxygen and water vapor barriers for food packaging. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2022;14(26):30236–45. doi:10.1021/acsami.2c07579. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

38. Kriechbaum K, Bergström L. Antioxidant and UV-blocking leather-inspired NC-based films with high wet strength. Biomacromolecules. 2020;21:1720–8. doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.9b01655. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

39. Costa SM, Ferreira DP, Teixeira P, Ballesteros LF, Teixeira JA, Fangueiro R. Active natural-based films for food packaging applications: the combined effect of chitosan and NC. Int J Biol Macromol. 2021;177:241–51. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2021.02.105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

40. Stoudmann N, Schmutz M, Hirsch C, Nowack B, Som C. Human hazard potential of NC: quantitative insights from the literature. Nanotoxicology. 2020;14(9):1241–57. doi:10.1080/17435390.2020.1814440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

41. Souza E, Gottschalk L, Freitas-Silva O. Overview of NC in food packaging. Recent Pat Food Nutr Agric. 2019;11(2):154–67. doi:10.2174/2212798410666190715153715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

42. Fauris C, Lundström H, Vilaginès R. Cytotoxicological safety assessment of papers and boards used for food packaging. Food Addit Contam. 1998;15:716–28. doi:10.1080/02652039809374702. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

43. Moreira S, Silva NB, Almeida-Lima J, Rocha HAO, Medeiros SRB, Alves C, et al. BC nanofibres: in vitro study of genotoxicity and cell proliferation. Toxicol Lett. 2009;189(3):235–41. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2009.06.849. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Ni H, Zeng S, Wu J, Cheng X, Luo T, Wang W, et al. Cellulose nanowhiskers: preparation, characterization and cytotoxicity evaluation. Biomed Mater Eng. 2012;22(1–3):121–7. doi:10.3233/BME-2012-0697. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

45. Azeredo HMC, Rosa MF, Mattoso LHC. NC in bio-based food packaging applications. Ind Crops Prod. 2017;97:664–71. doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.03.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Wang X, Guo J, Ren H, Jin J, He H, Jin P, et al. Research progress of NC-based food packaging. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2024;143:104289. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2023.104289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Fotie G, Limbo S, Piergiovanni L. Manufacturing of food packaging based on NC: current advances and challenges. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(9):1–26. doi:10.3390/nano10091726. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

48. Antony T, Cherian RM, Varghese RT, Kargarzadeh H, Ponnamma D, Chirayil CJ, et al. Sustainable green packaging based on NC composites-present and future. Cellulose. 2023;30:10559–93. doi:10.1007/s10570-023-05537-6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Lu Q, Yu X, Yagoub AEGA, Wahia H, Zhou C. Application and challenge of NC in the food industry. Food Biosci. 2021;43:101285. doi:10.1016/j.fbio.2021.101285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Perumal AB, Nambiar RB, Moses JA, Anandharamakrishnan C. NC: recent trends and applications in the food industry. Food Hydrocoll. 2022;127:107484. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.107484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Dong Y, Xie Y, Ma X, Yan L, Yu HY, Yang M, et al. Multi-functional NC based nanocomposites for biodegradable food packaging: hybridization, fabrication, key properties and application. Carbohydr Polym. 2023;321:121325. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

52. Qin Z, Ng W, Ede J, Shatkin JA, Feng J, Udo T, et al. NC and its modified forms in the food industry: applications, safety, and regulatory perspectives. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2024;23(6):e70049. doi:10.1111/1541-4337.70049. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Menas AL, Yanamala N, Farcas MT, Russo M, Friend S, Fournier PM, et al. Fibrillar vs crystalline NC pulmonary epithelial cell responses: cytotoxicity or inflammation? Chemosphere. 2017;171:671–80. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2016.12.105. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

54. Ventura C, Lourenço AF, Sousa-Uva A, Ferreira PJT, Silva MJ. Evaluating the genotoxicity of cellulose nanofibrils in a co-culture of human lung epithelial cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. Toxicol Lett. 2018;291:173–83. doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.04.013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

55. Pitkänen M, Kangas H, Laitinen O, Sneck A, Lahtinen P, Peresin MS, et al. Characteristics and safety of nano-sized cellulose fibrils. Cellulose. 2014;21(6):3871–86. doi:10.1007/s10570-014-0397-x. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Aimonen K, Suhonen S, Hartikainen M, Lopes VR, Norppa H, Ferraz N, et al. Role of surface chemistry in the In Vitro lung response to nanofibrillated cellulose. Nanomaterials. 2021;11(2):389. doi:10.3390/nano11020389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Pinto F, Lourenço AF, Pedrosa JFS, Gonçalves L, Ventura C, Vital N, et al. Analysis of the in vitro toxicity of NCs in human lung cells as compared to multi-walled carbon nanotubes. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(9):1432. doi:10.3390/nano12091432. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Mortensen NP, Moreno Caffaro M, Davis K, Aravamudhan S, Sumner SJ, Fennell TR. Investigation of eight cellulose nanomaterials’ impact on differentiated Caco-2 monolayer integrity and cytotoxicity. Food Chem Toxicol. 2022;166:113204. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2022.113204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

59. Lopes VR, Strømme M, Ferraz N. In vitro biological impact of NC fibers on human gut bacteria and gastrointestinal cells. Nanomaterials. 2020;10:1159. doi:10.3390/nano10061159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Čolić M, Mihajlović D, Mathew A, Naseri N, Kokol V. Cytocompatibility and immunomodulatory properties of wood based nanofibrillated cellulose. Cellulose. 2015;22:763–78. doi:10.1007/s10570-014-0524-8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

61. Souza SF, Mariano M, Reis D, Lombello CB, Ferreira M, Sain M. Cell interactions and cytotoxic studies of cellulose nanofibers from Curauá natural fibers. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;201:87–95. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2018.08.056. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

62. Lopes VR, Sanchez-Martinez C, Strømme M, Ferraz N. In vitro biological responses to nanofibrillated cellulose by human dermal, lung and immune cells: surface chemistry aspect. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2017;14(1):2017. doi:10.1186/s12989-016-0182-0. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

63. Ventura C, Marques C, Cadete J, Vilar M, Pedrosa JFS, Pinto F, et al. Genotoxicity of three Micro/NCs with different physicochemical characteristics in MG-63 and V79 cells. J Xenobiot. 2022;12(2):91–108. doi:10.3390/jox12020009. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

64. Mejía-Jaramillo AM, Gómez-Hoyos C, Cañas Gutierrez AI, Correa-Hincapié N, Zuluaga Gallego R, Triana-Chávez O. Tackling the cytotoxicity and genotoxicity of cellulose nanofibers from the banana rachis: a new food packaging alternative. Heliyon. 2023;9(11):e21560. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e21560. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

65. Athinarayanan J, Periasamy VS, Alshatwi AA. Fabrication and cytotoxicity assessment of cellulose nanofibrils using Bassia eriophora biomass. Int J Biol Macromol. 2018;117:911–8. doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.05.144. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

66. Fujita K, Obara S, Maru J, Endoh S, Kawai Y, Moriyama A, et al. Assessing cytotoxicity and biocompatibility of cellulose nanofibrils on alveolar macrophages. Cellulose. 2024;32:241–60. doi:10.1007/s10570-. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

67. Vital N, Ventura C, Kranendonk M, Silva MJ, Louro H. Toxicological assessment of cellulose nanomaterials: oral exposure. Nanomaterials. 2022;12(19):3375. doi:10.3390/nano12193375. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

68. Roman M. Toxicity of cellulose nanocrystals: a review. Ind Biotech. 2015;11(1):25–33. doi:10.1089/ind.2014.0024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

69. Camarero-Espinosa S, Endes C, Mueller S, Petri-Fink A, Rothen-Rutishauser B, Weder C, et al. Elucidating the potential biological impact of cellulose nanocrystals. Fibers. 2016;4:21. doi:10.3390/fib4030021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

70. Alamri MS, Qasem AAA, Mohamed AA, Hussain S, Ibraheem MA, Shamlan G, et al. Food packaging’s materials: a food safety perspective. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2021;28:4490–449. doi:10.1016/j.sjbs.2021.04.047. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

71. Gupta RK, Pipliya S, Karunanithi S, Eswaran UGM, Kumar S, Mandliya S, et al. Migration of chemical compounds from packaging materials into packaged foods: interaction, mechanism, assessment, and regulations. Foods. 2024;13(19):3125. doi:10.3390/foods13193125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

72. Huang JY, Li X, Zhou W. Safety assessment of nanocomposite for food packaging application. Trends Food Sci Technol. 2015;45(2):187–99. doi:10.1016/j.tifs.2015.07.002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

73. Ranjha MMAN, Shafique B, Rehman A, Mehmood A, Ali A, Zahra SM, et al. Biocompatible nanomaterials in food science, technology, and nutrient drug delivery: recent developments and applications. Front Nutr. 2022;8:778155. doi:10.3389/fnut.2021.778155. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

74. Tan C, Han F, Zhang S, Li P, Shang N, Di Pierro P, et al. Molecular sciences novel bio-based materials and applications in antimicrobial food packaging: recent advances and future trends. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(18):9663. doi:10.3390/ijms. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

75. Si Y, Lin Q, Zhou F, Qing J, Luo H, Zhang C, et al. The interaction between NC and microorganisms for new degradable packaging: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2022;295:119899. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2022.119899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

76. Gómez HC, Serpa A, Velásquez-Cock J, Gañán P, Castro C, Vélez L, et al. Vegetable NC in food science: a review. Food Hydrocoll. 2016;57:178–86. doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.01.023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

77. Cañas-Gutiérrez A, Gómez Hoyos C, Velásquez-Cock J, Gañán P, Triana O, Cogollo-Flórez J, et al. Health and toxicological effects of NC when used as a food ingredient: a review. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;323:121382. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2023.121382. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

78. Fahma F, Febiyanti I, Lisdayana N, Arnata IW, Sartika D. NC as a new sustainable material for various applications: a review. Arch Mater Sci Eng. 2021;109:49–64. doi:10.5604/01.3001.0015.2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

79. Endes C, Camarero-Espinosa S, Mueller S, Foster EJ, Petri-Fink A, Rothen-Rutishauser B, et al. A critical review of the current knowledge regarding the biological impact of NC. J Nanobiotechnol. 2016;14(1):78. doi:10.1186/s12951-016-0230-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

80. Brand W, van Kesteren PCE, Swart E, Oomen AG. Overview of potential adverse health effects of oral exposure to NC. Nanotoxicology. 2022;16(2):217–46. doi:10.1080/17435390.2022.2069057. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

81. Sai T, Fujita K. A review of pulmonary toxicity studies of NC. Inhal Toxicol. 2020;32(6):231–9. doi:10.1080/08958378.2020.1770901. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

82. Kautto P, Valve H. Cosmopolitics of a regulatory fit: the case of NC. Sci Cult. 2019;28(4):25–45. doi:10.1080/09505431.2018.1533935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

83. Roeben G, Rauscher H, Amenta V, Aschberger K, Boix SA, Calzolai L, et al. Towards a review of the EC recommendation for a definition of the term “nanomaterial.” Part 2: assessment of collected information concerning the experience with the definition; 2014. [cited 2025 June 24]. Available from: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC91377/jrc_nm-def_report2_eur26744.pdf. [Google Scholar]

84. Rauscher H, Kestens V, Rasmussen K, Linsinger T, Stefaniak E. Guidance on the implementation of the Commission Recommendation 2022/C 229/01 on the definition of nanomaterial. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union; 2023. [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC132102. [Google Scholar]

85. Rauscher H, Roebben G, Amenta V, Boix A, Calzolai SL, Emons H, et al. Towards a review of the EC Recommendation for a definition of the term “nanomaterial” Part 1: compilation of information concerning the experience with the definition; 2014. [cited 2025 June 24]. Available from: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/bitstream/JRC89369/lbna26567enn.pdf. [Google Scholar]

86. Cattaneo I. Stakeholder workshop on small particles and nanoparticles in food, 30 March–1 April 2022. EFSA Methodology and Scientific Support Unit; 2022. [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/en/events/stakeholder-workshop-small-particles-and-nanoparticles-food. [Google Scholar]

87. Hristozov D, Badetti E, Bigini P, Brunelli A, Dekkers S, Diomede L, et al. Next generation risk assessment approaches for advanced nanomaterials: current status and future perspectives. NanoImpact. 2024;35:100523. doi:10.1016/j.impact.2024.100523. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

88. Schwirn K, Tietjen L, Beer I. Why are nanomaterials different and how can they be appropriately regulated under REACH? Environ Sci Eur. 2014;26:4. doi:10.1186/2190-4715-26-4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

89. Donaldson K, Schinwald A, Murphy F, Cho WS, Duffin R, Tran L, et al. The biologically effective dose in inhalation nanotoxicology. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46(3):723–32. doi:10.1021/ar300092y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

90. Catalán J, Norppa H. Safety aspects of bio-based nanomaterials. Bioengineering. 2017;4(4):94. doi:10.3390/bioengineering4040094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

91. Caldeira C, Farcal R, Garmendia Aguirre I, Mancini L, Tosches D, Amelio A, et al. Safe and sustainable by design chemicals and materials—framework for the definition of criteria and evaluation procedure for chemicals and materials. documento caldeira SSbD [Internet]; 2022. [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: https://publications.jrc.ec.europa.eu/repository/handle/JRC128591. [Google Scholar]

92. Apel C, Kümmerer K, Sudheshwar A, Nowack B, Som C, Colin C, et al. Safe-and-sustainable-by-design: state of the art approaches and lessons learned from value chain perspectives. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem. 2024;45:100876. doi:10.1016/j.cogsc.2023.100876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

93. Bhat MA, Radu T, Martín-Fabiani I, Kolokathis PD, Papadiamantis AG, Wagner S, et al. Safe and sustainable by design of next generation chemicals and materials: SSbD4CheM project innovations in the textiles, cosmetic and automotive sectors. Comput Struct Biotechnol J. 2025;29:60–71. doi:10.1016/j.csbj.2025.03.022. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

94. da Cruz TT, Las-Casas B, Dias IKR, Arantes V. NCs as sustainable emerging technologies: state of the art and future challenges based on life cycle assessment. Sustain Mater Technol. 2024;41:e01010. doi:10.1016/j.susmat.2024.e01010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

95. Shatkin JA, Kim B. Cellulose nanomaterials: life cycle risk assessment, and environmental health and safety roadmap. Environ Sci Nano. 2015;2:477–99. doi:10.1039/c5en00059a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

96. Foroughi F, Ghomi ER, Dehaghi FM, Borayek R, Ramakrishna S. A review on the life cycle assessment of cellulose: from properties to the potential of making it a low carbon material. Materials. 2021;14(4):1–23. doi:10.3390/ma14040714. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

97. Nordli HR, Chinga-Carrasco G, Rokstad AM, Pukstad B. Producing ultrapure wood cellulose nanofibrils and evaluating the cytotoxicity using human skin cells. Carbohydr Polym. 2016;150:65–73. doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.094. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

98. Thu HE, Haider MA, Khan S, Sohail M, Hussain Z. Nanotoxicity induced by nanomaterials: a review of factors affecting nanotoxicity and possible adaptations. OpenNano. 2023;14:100190. doi:10.1016/j.onano.2023.100190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

99. Donaldson K, Tran CL. An introduction to the short-term toxicology of respirable industrial fibres. Mutat Res. 2004;553(1–2):5–9. doi:10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2004.06.011. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

100. Donaldson K, Murphy FA, Duffin R. Asbestos, carbon nanotubes and the pleural mesothelium: a review of the hypothesis regarding the role of long fibre retention in the parietal pleura, inflammation and mesothelioma [Internet]; 2010. [cited 2025 Jun 24]. Available from: http://www.particleandfibretoxicology.com/content/7/1/5. [Google Scholar]

101. Xuan L, Ju Z, Skonieczna M, Zhou PK, Huang R. Nanoparticles-induced potential toxicity on human health: applications, toxicity mechanisms, and evaluation models. MedComm. 2023;4:e327. doi:10.1002/mco2.327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

102. Guo C, Lv S, Liu Y, Li Y. Biomarkers for the adverse effects on respiratory system health associated with atmospheric particulate matter exposure. J Hazard Mater. 2022;5(421):126760. doi:10.1016/j.jhazmat.2021.126760. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

103. Boey JY, Mohamad L, Khok YS, Tay GS, Baidurah S. A review of the applications and biodegradation of polyhydroxyalkanoates and poly(lactic acid) and its composites. Polymers. 2021;13(10):1544. doi:10.3390/polym13101544. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

104. Zhao X, Cornish K, Vodovotz Y. Narrowing the gap for bioplastic use in food packaging: an update. Environ Sci Technol. 2020;54(8):4712–32. doi:10.1021/acs.est.9b03755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

105. Lie E, Ålander E, Lindström T. Possible toxicological effects of NC—an updated literature study, No 2. [Internet]; 2017. [cited 2024 Dec 5]. Available from: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1266175/FULLTEXT01.pdf. [Google Scholar]

106. Kiani AK, Pheby D, Henehan G, Brown R, Sieving P, Sykora P, et al. Ethical considerations regarding animal experimentation. J Prev Med Hyg. 2022;63:E255–66. doi:10.15167/2421-4248/jpmh2022.63.2S3.2768. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

107. Von Ranke NL, Geraldo RB, dos Santos LA, Evangelho VGO, Flammini F, Cabral LM, et al. Applying in silico approaches to nanotoxicology: current status and future potential. Comput Toxicol. 2022;22:100225. doi:10.1016/j.comtox.2022.100225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

108. Verma SK, Nandi A, Simnani FZ, Singh D, Sinha A, Naser SS, et al. In silico nanotoxicology: the computational biology state of art for nanomaterial safety assessments. Mater Des. 2023;235:112452. doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2023.112452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

109. Cao X, Zhang T, DeLoid GM, Gaffrey MJ, Weitz KK, Thrall BD, et al. Cytotoxicity and cellular proteome impact of cellulose nanocrystals using simulated digestion and an in vitro small intestinal epithelium cellular model. NanoImpact. 2020;20:100269. doi:10.1016/j.impact.2020.100269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

110. DeLoid GM, Cao X, Molina RM, Silva DI, Bhattacharya K, Ng KW, et al. Toxicological effects of ingested NC in: in vitro intestinal epithelium and in vivo rat models. Environ Sci Nano. 2019;6:2105–15. doi:10.1039/c9en00184k. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

111. DeLoid GM, Wang Y, Kapronezai K, Lorente LR, Zhang R, Pyrgiotakis G, et al. An integrated methodology for assessing the impact of food matrix and gastrointestinal effects on the biokinetics and cellular toxicity of ingested engineered nanomaterials. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2017;14:40. doi:10.1186/s12989-017-0221-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

112. Cummings BS, Schnellmann RG. Measurement of cell death in mammalian cells. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2004;25:12.8.1–22. doi:10.1002/0471141755.ph1208s25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

113. Alexandrescu L, Syverud K, Gatti A, Chinga-Carrasco G. Cytotoxicity tests of cellulose nanofibril-based structures. Cellulose. 2013;20:1765–75. doi:10.1007/s10570-013-9948-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

114. Hardy A, Benford D, Halldorsson T, Jeger MJ, Knutsen HK, More S, et al. Guidance on risk assessment of the application of nanoscience and nanotechnologies in the food and feed chain: part 1, human and animal health. EFSA J. 2018;16(7):e05327. doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2018.5327. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

115. Chrz J, Hošíková B, Svobodová L, Očadlíková D, Kolářová H, Dvořaková M, et al. Comparison of methods used for evaluation of mutagenicity/genotoxicity of model chemicals—parabens. Physiol Res. 2020;69:S661–79. doi:10.33549/physiolres.934615. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

116. Kollar P, Závalová V, Hošek J, Havelka P, Sopuch T, Karpíšek M, et al. Cytotoxicity and effects on inflammatory response of modified types of cellulose in macrophage-like THP-1 cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2011;11:997– 1001. doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2011.02.016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

117. Vartiainen J, Pöhler T, Sirola K, Pylkkänen L, Alenius H, Hokkinen J, et al. Health and environmental safety aspects of friction grinding and spray drying of microfibrillated cellulose. Cellulose. 2011;18:775–86. doi:10.1007/s10570-011-9501-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

118. Kümmerer K, Menz J, Schubert T, Thielemans W. Biodegradability of organic nanoparticles in the aqueous environment. Chemosphere. 2011;82:1387–92. doi:10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.11.069. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

119. Boros BV, Ostafe V. Evaluation of ecotoxicology assessment methods of nanomaterials and their effects. Nanomaterials. 2020;10(4):610. doi:10.3390/nano10040610. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

120. Handy RD, Van Den Brink N, Chappell M, Mühling M, Behra R, Dušinská M, et al. Practical considerations for conducting ecotoxicity test methods with manufactured nanomaterials: what have we learnt so far? Ecotoxicology. 2012;21:933–72. doi:10.1007/s10646-012-0862-y. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

121. Hund-Rinke K, Baun A, Cupi D, Fernandes TF, Handy R, Kinross JH, et al. Regulatory ecotoxicity testing of nanomaterials-proposed modifications of OECD test guidelines based on laboratory experience with silver and titanium dioxide nanoparticles. Nanotoxicology. 2016;10:1442–7. doi:10.1080/17435390.2016.1229517. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

122. Moriyama A, Ogura I, Fujita K. Potential issues specific to cytotoxicity tests of cellulose nanofibrils. J Appl Toxicol. 2023;43(1):195–207. doi:10.1002/jat.4390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

123. Souza SF, Leao AL, Lombello CB, Sain M, Ferreira M. Cytotoxicity studies of membranes made with cellulose nanofibers from fique macrofibers. J Mater Sci. 2017;52:2581–90. doi:10.1007/s10853-016-0551-. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

124. Ventura C, Pinto F, Lourenço AF, Pedrosa JFS, Fernandes SN, da Rosa RR, et al. Assessing the genotoxicity of cellulose nanomaterials in a co-culture of human lung epithelial cells and monocyte-derived macrophages. Bioengineering. 2023;10(8):986. doi:10.3390/bioengineering10080986. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

125. Muhle H, Ernst H, Bellmann B. Investigation of the durability of cellulose fibres in rat lungs. Ann Occup Hyg. 1997;41(1):184–8. doi:10.1093/annhyg/41.inhaled_particles_VIII.184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]