Open Access

Open Access

ARTICLE

Surface Modification of Activated Carbon by Nitrogen Doping and KOH Activation for Enhanced Carbon Dioxide Adsorption Performance

1 Department of Advanced Materials Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Burapha University, Chonburi, 20131, Thailand

2 National Nanotechnology Center, Pathumthani, 12120, Thailand

3 National Metal and Materials Technology Center, Pathumthani, 12120, Thailand

4 Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Burapha University, Chonburi, 20131, Thailand

5 Interdisciplinary Center of Robotics Technology (ICRT), Faculty of Engineering, Burapha University, Chonburi, 20131, Thailand

6 Department of Chemical Engineering, Faculty of Engineering, Srinakharinwirot University, Nakhonnayok, 26120, Thailand

7FILTER MATCH Co., Ltd., Bangkok, 10520, Thailand

8 College of Materials Innovation and Technology, King Mongkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang, Bangkok, 10520, Thailand

* Corresponding Author: Worawut Muangrat. Email:

Journal of Renewable Materials 2025, 13(11), 2155-2168. https://doi.org/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0111

Received 12 June 2025; Accepted 25 September 2025; Issue published 24 November 2025

Abstract

Nitrogen-doped activated carbon (N-AC) was successfully prepared by KOH-activation and nitrogen doping using ammonia (NH3) heat treatment. Coconut shell-derived activated carbon (AC) was heat-treated under NH3 gas in the temperature range of 700°C–900°C. Likewise, the mixture of potassium hydroxide (KOH) and AC was heated at 800°C, followed by heat treatment under NH3 gas at 800°C (hereafter referred to as KOH-N-AC800). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) method were utilized to analyze morphology, crystallinity, chemical bonding, chemical composition and surface area. The surface area and porosity of N-AC increased with increasing NH3 heat treatment. Similarly, the nitrogen content in the N-AC increased from 3.23% to 4.84 at% when the NH3 heat treatment was raised from 700°C to 800°C. However, the nitrogen content of N-AC decreased to 3.40 at% after using NH3 heat treatment at 900°C. The nitrogen content of KOH-N-AC800 is 5.43 at%. KOH-N-AC800 and N-AC800 exhibited improvements of 33.66% and 26.24%, respectively, in CO2 adsorption compared with AC. The enhancement of CO2 adsorption of KOH-N-AC800 is attributed to the synergic effect of the nitrogen doping, high surface area, and porosity. The results exhibited that nitrogen sites on the surface play a more significant role in CO2 adsorption than surface area and porosity. This work proposes the potential synergistic effect of KOH-activation and nitrogen doping for enhancing the CO2 adsorption capacity of activated carbon.Keywords

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material FileGlobal warming represents a critical environmental challenge that requires immediate action. According to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), particularly SDG 13, addressing climate change is a critical priority, especially the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is one of the greenhouse gases that is emitted through transportation, industrial processes, burning of fossil fuels, and agricultural burning. The World Meteorological Organization reports that CO2 emissions are projected to reach 41.6 billion tons in 2024, up from 40.6 billion tons in 2023. Thus, reducing the release of CO2 directly into the atmosphere is an urgent issue. Carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) represents a promising technology for reducing CO2 emissions. CCUS involves carbon capture, transportation, utilization and storage [1–3]. Adsorbent materials for carbon capture are an important component of CCUS. Porous materials such as silica, metal-organic frameworks, porous organic polymer, and zeolites, have been widely used as potential materials for carbon capture due to their high surface area and high porosity [4–7]. However, the drawbacks of these materials include the requirement for energy-intensive regeneration, limited selectivity in humid environments, and high costs.

Activated carbon (AC) is an effective material for CO2 adsorption due to its high surface area, excellent thermal stability, chemical inertness, easily tunable structure, ability to be chemically modified on their surface, low cost, and low energy consumption for regeneration [8–12]. Many efforts have considered agricultural wastes as a resource for the production of AC due to their high carbon content, abundance, and low cost [13–16]. Previous reports have demonstrated that agricultural waste-derived AC is a potential adsorbent for CO2 adsorption. Increasing the surface area and porosity by chemical and physical activations [17–20] and heteroatom doping [21–23] of agricultural waste-derived AC, has been widely studied to improve CO2 adsorption performance and mitigate nitrogen oxide emissions [24]. Furthermore, the combination of chemical or physical activation processes with nitrogen doping has been shown to greatly increase CO2 adsorption capacity [21,25–27]. For instance, as-prepared AC from tea seed shells using potassium hydroxide (KOH) activation, followed by nitrogen doping with melamine as the nitrogen source for enhanced CO2 adsorption proposed [21]. As-prepared materials showed the best CO2 capturing capacity due to their high surface area. The specific surface area played a significant role in CO2 capture. Spessato et al. prepared nitrogen-doped activated carbon (N-AC) using the procedure of KOH-activation and nitrogen doping using melamine, hexamethylenetetramine, or tetramethylammonium hydroxide [27]. The results evidence that nitrogen doping, especially pyridinic-type doping, tends to contribute more to CO2 adsorption than extremely high surface area values. However, the nitrogen-doping technique requires a solid agent of nitrogen source, chemical purification, or time-consuming procedures as reported in previous works [21,25–27]. Recently, Ruan et al. [28] demonstrated that ammonia (NH3) activation is an effective method for preparing N-AC from pine sawdust. Heat treatment under NH3 not only introduces nitrogen atoms onto the surface of AC but also increases the surface area through NH3 etching. The CO2 adsorption capacity of N-AC is more strongly related to the presence of nitrogen-containing groups than to surface area. NH3 heat treatment has been proposed as a facile method for nitrogen doping.

Coconut is one of the top 10 most-produced fruits globally. In 2024, global coconut production was estimated at approximately 65.4 million metric tons. A large amount of coconut shells is discarded into the environment. The conversion of coconut shells into AC has attracted significant attention as a sustainable solution that aligns with SDG 12: Responsible Consumption and Production. Coconut shells widely abundant in Asian agricultural waste have emerged as a promising adsorbent for CO2 capture. To the best of our knowledge, the combination of nitrogen doping using NH3 and chemical activation of coconut shell-derived AC to improve CO2 adsorption performance has not been fully explored. In this work, N-AC was successfully prepared for application in CO2 adsorption. Coconut shell-derived AC was mixed with KOH and activated under an argon atmosphere, followed by heat treatment under an NH3 atmosphere. KOH activation in the first step provided a porous structure that allowed NH3 gas to enter the pores, resulting in a high nitrogen content. The KOH-activated and nitrogen-doped AC exhibits approximately 34% enhancement in CO2 adsorption compared to AC without any modification. The improvement is attributed to the presence of nitrogen atoms, which serve as active sites for CO2 adsorption, as well as the high surface area.

2.1 Nitrogen Doping and KOH Activation of Activated Carbon

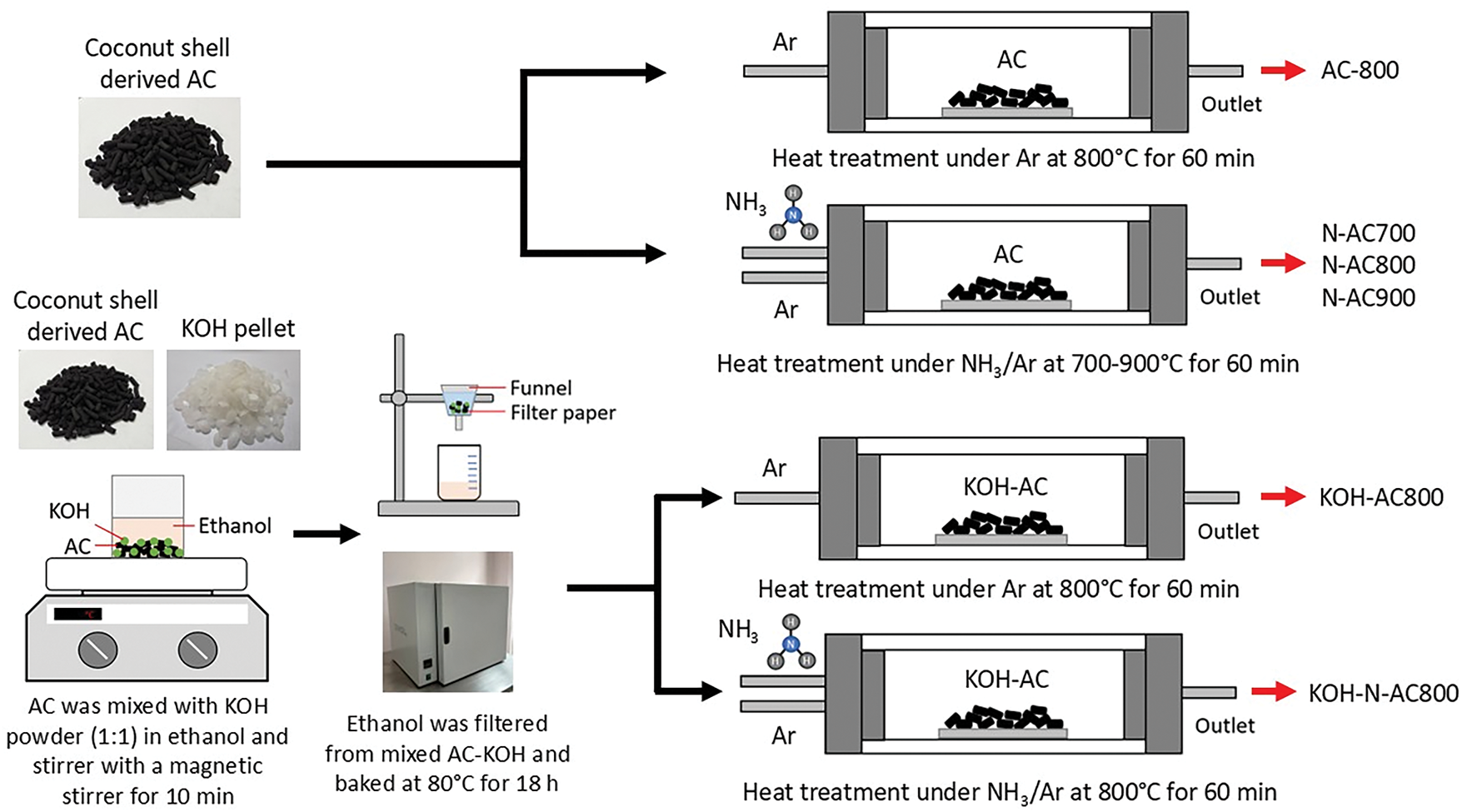

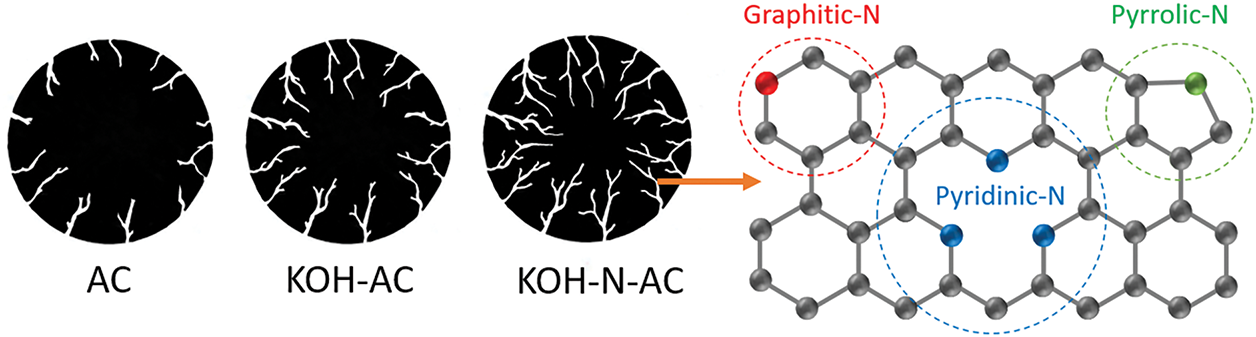

Commercial activated carbons (AC, VPAC-P4/1050) based on coconut shells were supported by FILTER MATCH Co., Ltd. (Thailand). For surface modification, AC was doped with nitrogen atoms via heat treatment under NH3 gas (99.5%). AC was placed in the center of the horizontal quartz tube furnace. The temperature of the reaction zone was raised from room temperature to the desired treatment temperature with a heating rate of 10°C/min under 500 mL/min of argon (Ar) gas (99.9%). AC was separately treated at 700°C, 800°C, and 900°C under a mixture of Ar (100 mL/min) and NH3 (50 mL/min) gases for 60 min (hereafter referred to as N-AC700, N-AC800, and N-AC900, respectively). Then, as-prepared N-AC was cooled down to room temperature under argon gas (500 mL/min). For comparison, AC was separately treated under 100 mL/min of Ar gas at 800°C (hereafter, referred to as AC800). To increase surface area, AC was mixed with KOH with a weight ratio of 1:1 in ethanol by magnetic stirrer for 10 min. Then, the KOH-AC mixture in ethanol was filtered to remove the ethanol and baked at 80°C for 18 h. As-prepared KOH-AC was treated under 100 mL/min of Ar gas at 800°C (hereafter referred to as KOH-AC800). Next, as-prepared KOH-AC800 was heat-treated under a mixture of Ar (100 mL/min) and NH3 (50 mL/min) gases at 800°C for 60 min (hereafter referred to as KOH-N-AC800). Fig. 1 shows a schematic illustration of the preparation processes of N-AC, KOH-AC, and KOH-N-AC. The structural evolution of AC, KOH-AC, and KOH-N-AC, and the chemical structure of KOH-N-AC are presented in Fig. 2.

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of the preparation of N-AC, KOH-AC, and KOH-N-AC

Figure 2: Structural evolution of AC, KOH-AC, and KOH-N-AC. Chemical structures of KOH-N-AC

2.2 Characterization Techniques

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JEOL JSM-7800F) was conducted to investigate the surface morphology and structure. The elemental analysis was characterized via SEM equipped with energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS, OXFORD, X-act). Raman spectroscopy (HORIBA LabRam HR, excitation laser at 532 nm) was utilized to analyze the crystallinity. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, AXIS Ul-traDLD, Kratos Analytical) was employed to examine the surface elemental analysis. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements at 77 K were conducted to evaluate the surface area via the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET, Micromeritics, TriStarII 3020).

2.3 Carbon Dioxide and Nitrogen Adsorption

The CO2 and N2 adsorption isotherm were performed by the surface analyzer (Micrometrics: 3Flex surface characterization). Prior to adsorption measurement, all samples were degassed at 300°C for 16 h to remove moisture and impurities. CO2 and N2 adsorption were measured at 25°C in the pressure range of 0–1.0 bar.

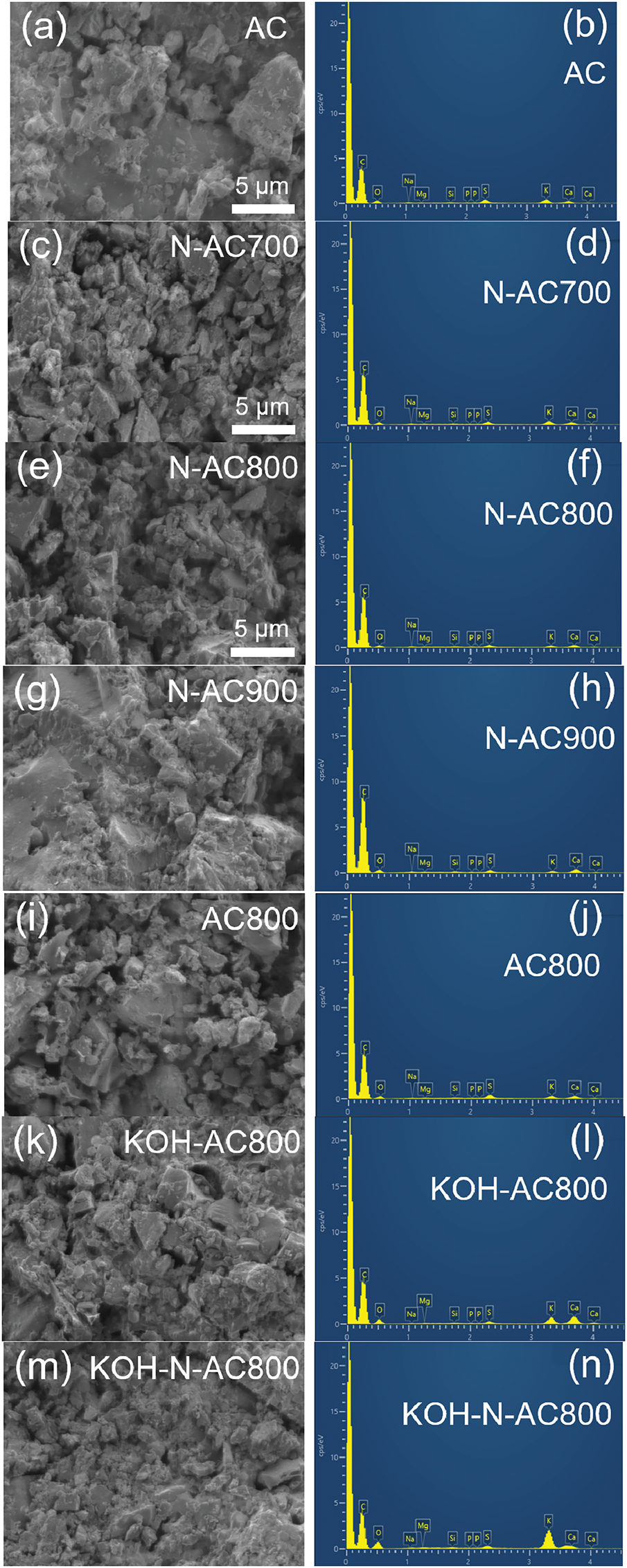

Fig. 3 shows SEM images and EDS spectra of AC (Fig. 3a,b), N-AC (Fig. 3c–h), heat-treated AC (Fig. 3i,j), KOH-AC (Fig. 3k,l), and KOH-N-AC (Fig. 3m,n). SEM analysis revealed that all samples have a smooth surface with irregular particle sizes, and no obvious pores were observed. However, the evidence of pores was analyzed by BET, which will be discussed later. The EDS spectra of all samples mainly consist of carbon and oxygen at ~0.3 keV (Kα) and ~0.5 keV (Kα), respectively. Sodium, magnesium, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur, potassium, and calcium were observed in low concentrations. The elemental compositions of all samples are summarized in Table S1. The EDS analysis results indicated that carbon content increased after heat treatment under NH3 and Ar. Increasing the temperature from 700°C to 800°C under NH3 heat treatment results in a decrease in oxygen content. Heat treatment under NH3 and Ar atmosphere led to an increase volatile matter degradation. Raman spectroscopy was employed to analyze the crystallinity of all samples.

Figure 3: SEM images and EDS spectra of (a,b) AC, (c,d) N-AC700, (e,f) N-AC800, (g,h) N-AC900, (i,j) AC800, (k,l) KOH-AC800, and (m,n) KOH-N-AC800

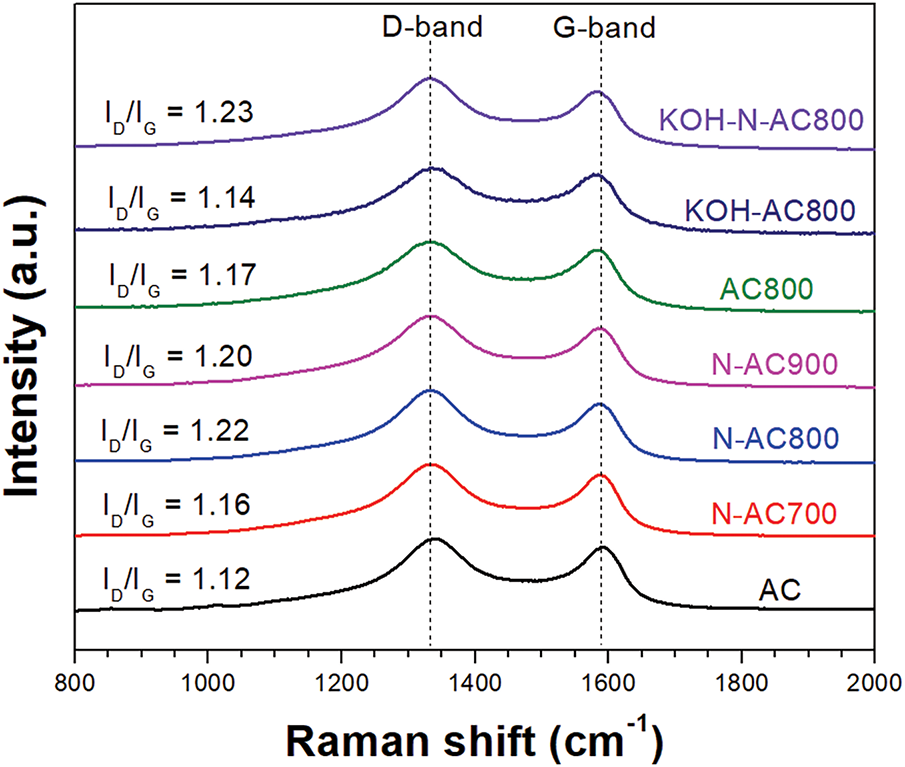

Fig. 4 shows two strong peaks at around ~1340 and ~1590 cm−1, which related to the defects in graphite (D-band) and crystalline graphite (G-band), respectively. The degree of order and defects of carbon materials are calculated by the intensity ratio of the D-band and G-band (ID/IG) [29–31]. The ID/IG values of AC, N-AC700, N-AC800, N-AC900, and AC800 were 1.12, 1.16, 1.22, 1.20, and 1.17, respectively. The ID/IG value increased with the increasing temperature of the heat treatment under NH3 gas from 700°C to 800°C due to the incorporation of nitrogen atoms as defects into the carbon structure. However, the ID/IG value slightly decreased when the NH3 treatment temperature increased to 900°C. It seems that the nitrogen doping in AC reaches saturation at a temperature of 800°C. This result was confirmed by XPS, which will be discussed later. The ID/IG values of KOH-AC800 and KOH-N-AC800 were 1.14 and 1.23, respectively. The increasing in the ID/IG of KOH-N-AC800 compared to KOH-AC800 implied that nitrogen atoms were successfully incorporated in the surface of KOH-activated AC [27,32,33].

Figure 4: Raman spectra of all samples

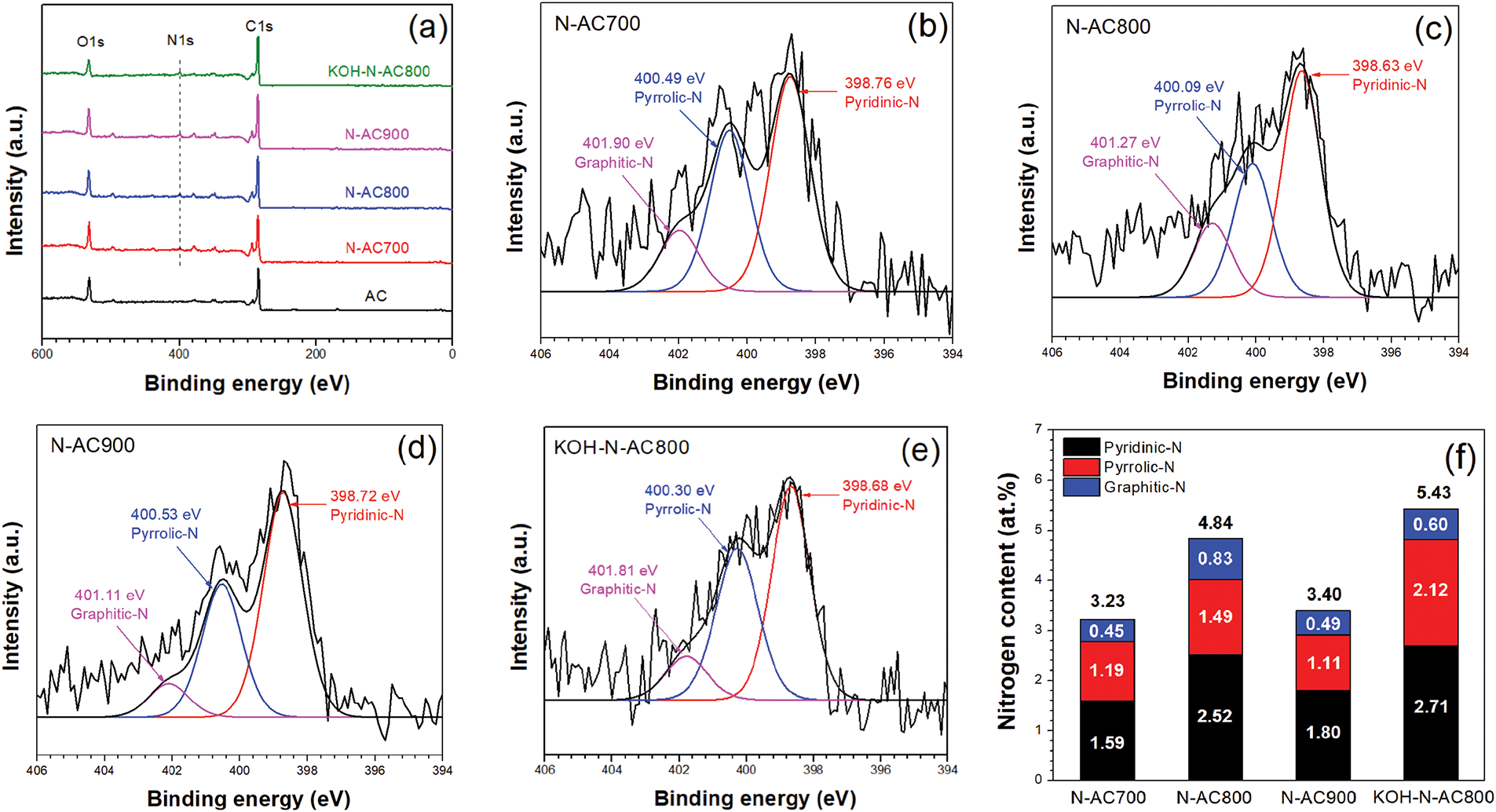

Fig. 5a shows the XPS survey spectra of all samples. The two obvious peaks were observed at ~284 and ~532 eV, which are related to C1s and O1s, respectively. In addition, the presence of the N1s peak of N-AC and KOH-N-AC was observed at ~400 eV. This peak indicated that nitrogen atoms were successfully doped into AC. The C1s peak of all samples reveals four sub-peaks: C–C, C–O, C=O, and O–C=O as shown in Fig. S1 (Supplementary Materials). For the O1s peak, the four fitting peaks: C=O, C–O, O–C=O, and O–H as shown in Fig. S2 (Supplementary Materials) [34–36]. The N1s peak of N-AC and KOH-N-AC can be deconvoluted into three peaks: pyridinic-N, pyrrolic-N and graphitic-N as illustrated in Fig. 5b–e [37,38]. The composition (%) of C1s, O1s and N1s, and CO2 uptake at 25°C and 1 bar of AC, N-AC, and KOH-N-AC are summarized in Table 1. The N/C ratios of N-AC700, N-AC800, N-AC900, and KOH-N-AC800 were 3.23, 4.84, 3.40, and 5.43 at%, respectively. The results indicated that the optimum temperature for nitrogen doping in AC is 800°C, which corresponds to the ID/IG value derived from Raman spectra. It was found that the content of pyridinic-N, pyrrolic-N and graphitic-N increases with the treatment under NH3 gas from 700°C to 800°C, and then decreases after heat treatment under NH3 gas at 900°C as shown in Fig. 5f. Furthermore, the nitrogen content of KOH-N-AC800 is higher than that of N-AC800.The increase in nitrogen content is attributed to the oxygen-containing functional groups in the AC, which are introduced by KOH activation and facilitate nitrogen enrichment [39,40]. The relationship between CO2 adsorption performance and nitrogen content will be discussed later with the surface area analyzed by BET.

Figure 5: (a) XPS survey of AC, N-AC, and KOH-N-AC. The N1s spectra of (b) N-AC700, (c) N-AC800, (d) N-AC900, and (e) KOH-N-AC800. (f) Nitrogen content of N-AC and KOH-N-AC

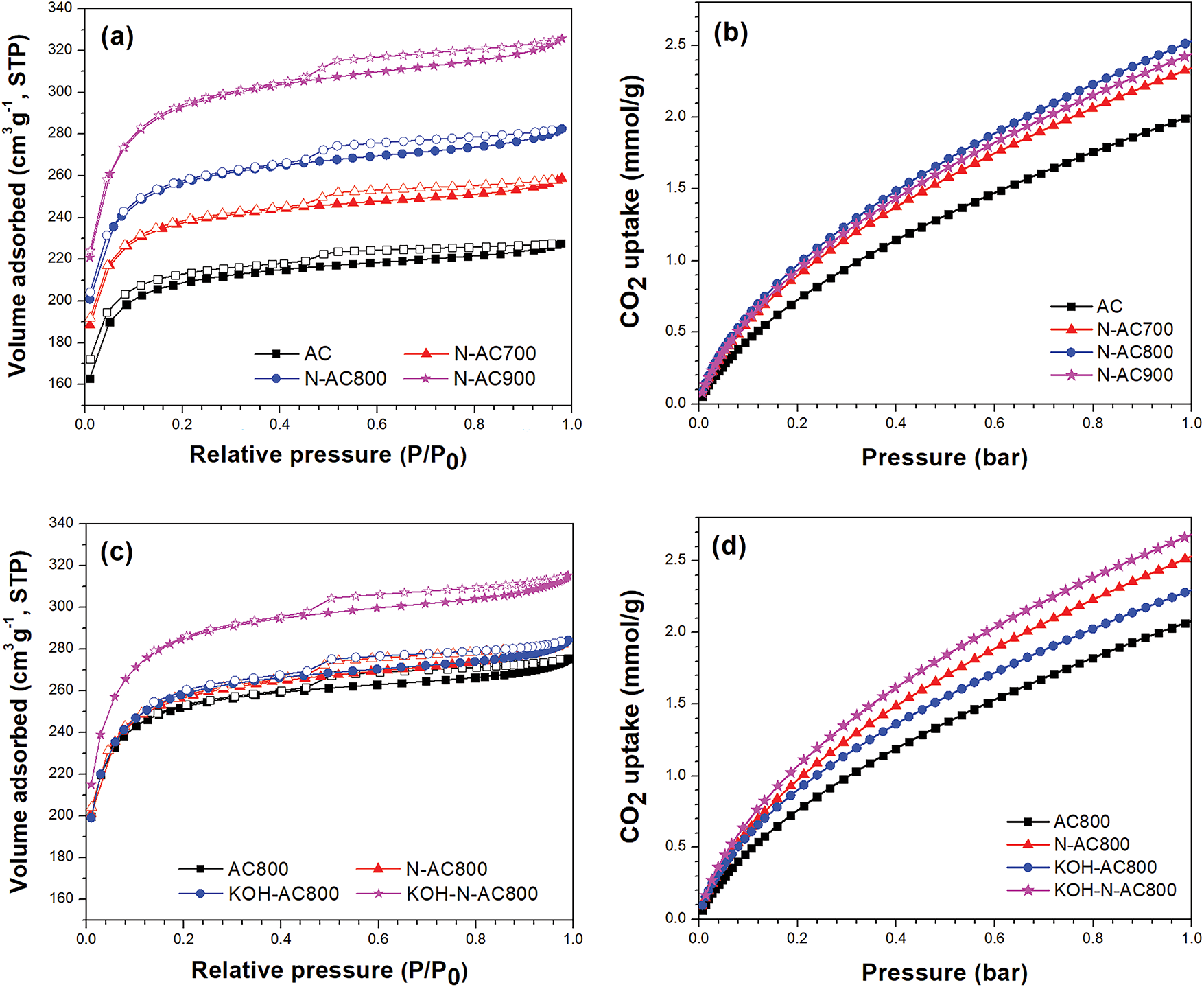

The specific surface area (SBET), total pore volume, micropore volume, pore diameter, N/C ratio, and CO2 uptake at 25°C and 1 bar of all samples are summarized in Table 2. The SBET and pore size distribution were calculated by N2 adsorption/desorption isotherm using the BET and density functional theory method, respectively. The adsorption increases rapidly at the initial stage, and then gradually reaches saturation, indicating that the samples possess a high proportion of micropores. The adsorption isotherms of all samples exhibit both type I and type IV, corresponding to the IUPAC classification as shown in Fig. 6a,c. Isotherm types I and IV represent the microporous and mesoporous materials [41–43]. The results showed that the SBET, total volume and micropore volume increased with an increasing NH3 treatment temperature. NH3 heat treatment not only introduces nitrogen atoms into AC but also improves surface area, micropore, and total pore volume. According to previous studies, NH3 heat treatment at 700°C or higher enhances the surface area and porosity of activated carbon because the decomposed NH2 and NH radicals from NH3 attack the carbon surface and also form nitrogen-containing functional groups [44–46]. Fig. 6b shows the CO2 adsorption profiles at 25°C of AC and N-AC. The results showed that the CO2 adsorption of AC, N-AC700, N-AC800 and N-AC900 were 2.02, 2.35, 2.55, and 2.45 mmol/g, respectively. N-AC800 exhibits 26.24% higher CO2 adsorption compared to AC without any modification. Although N-AC900 has the highest surface area, micropore volume and total pore volume, their CO2 adsorption is lower than that of N-AC800. The results exhibited that nitrogen doping in AC plays a more significant role in CO2 adsorption than surface area and porosity [27,28,47]. The enhancement of CO2 adsorption capacity is attributed to the increase in pore structure and the presence of active sites introduced by nitrogen doping. For the pore structure, the surface area and micropore volume are important factors influencing CO2 adsorption performance. A higher surface area and a large volume of micropores provide abundant adsorption sites for CO2 molecules through van der Walls forces [48–50]. In the case of N-AC, a previous theoretical study based on density functional theory (DFT) demonstrated that the CO2 adsorption capacity increases with higher nitrogen doping concentrations in carbon materials [51], which is consistent with our results. In addition, the enhancement of CO2 adsorption on N-AC can be explained by nitrogen-derived functional groups like pyridinic-N, pyrrolic-N, and graphitic-N, which act as active sites for CO2 adsorption [47,50]. According to a previous theoretical study based on DFT [52], pyridinic-N-doped carbon materials serve as chemisorption sites for CO2 adsorption. The nitrogen atom functions as a mediator, attracting electrons from surrounding carbon atoms and donating them to facilitate bond formation with the CO2 molecule. In contrast, pristine carbon materials and graphitic-N-doped carbon materials interact with CO2 through physisorption. Pyridinic-N-doped carbon materials exhibited higher CO2 adsorption energy compared to pristine carbon materials and graphitic-N-doped carbon materials, thereby enhancing the CO2 adsorption capacity. Furthermore, experimental results indicate that the introduction of the Lewis base site onto the surface of AC enhances CO2 adsorption [53–57]. The Lewis base sites in the carbon materials are generated by nitrogen doping. Pyridinic-N acts as an anchoring site for CO2 through Lewis base interactions, thereby enhancing the specific adsorbent-adsorbate interactions for CO2. Fig. 6d shows the CO2 adsorption profiles at 25°C of AC800, N-AC800, KOH-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800. The CO2 adsorption of AC800, N-AC800, KOH-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800 were 2.07, 2.55, 2.31, and 2.70 mmol/g, respectively. KOH-N-AC800 exhibits 33.66% higher CO2 adsorption compared to AC. The improvement in CO2 adsorption capacity of KOH-N-AC800 is ascribed to the synergistic effects of surface area enhancement and nitrogen doping, induced by sequential KOH activation and NH3 heat treatment. Although the surface area of KOH-N-AC800 (903.74 m2/g) is lower than that of N-AC900 (926.32 m2/g), KOH-N-AC800 exhibits the highest CO2 adsorption capacity, which is attributed to its higher N/C ratio that plays a crucial role in CO2 adsorption [27,28,47].

Figure 6: Nitrogen adsorption (filled symbols)-desorption (empty symbols) isotherms of (a) AC and N-AC and (c) AC800, N-AC800, KOH-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800. CO2 adsorption isotherms of (b) AC and N-AC and (d) AC800, N-AC800, KOH-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800 at 25°C

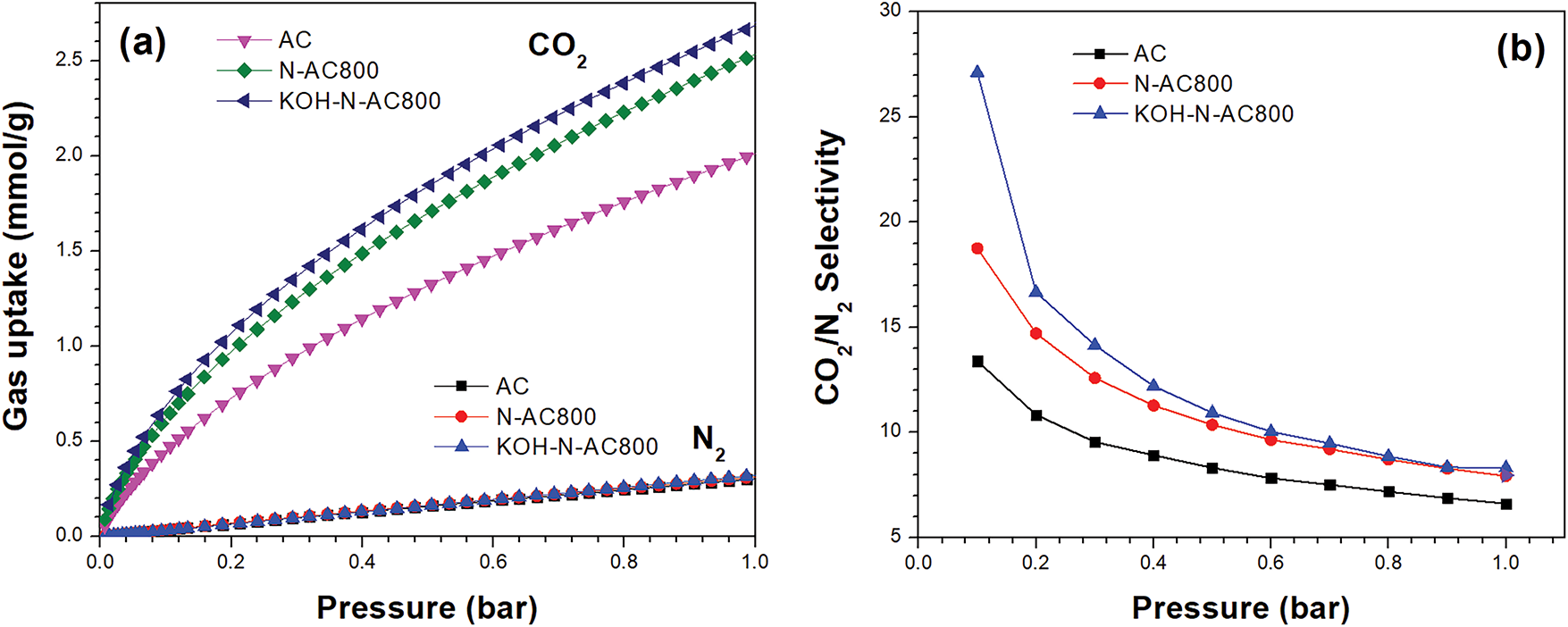

Fig. 7a presents the CO2 and N2 adsorption isotherms of AC, N-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800 as a function of pressure at 25°C. At 1 bar, the CO2 adsorption of AC, N-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800 were 2.02, 2.55, and 2.70 mmol/g, respectively, while the N2 adsorption were 0.30, 0.30, and 0.32 mmol/g, respectively. The CO2 adsorption capacity of KOH-N-AC800 is higher and more rapidly compared to N2, indicating that KOH-N-AC800 can be used for selective capture of CO2. Fig. 7b shows the CO2/N2 selectivity of AC, N-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800 as a function of pressure at 25°C. Selectivity of CO2 over N2 was determined using the ideal adsorption solution theory based on the adsorption isotherms of CO2 and N2 [58–60]. The results showed that KOH-N-AC800 and N-AC800 exhibit higher CO2/N2 selectivity values than AC, which is attributed to nitrogen doping in KOH-N-AC800 and N-AC800 that enhances preferential CO2 adsorption [60].

Figure 7: (a) CO2 and N2 adsorption isotherms of AC, N-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800 at 25°C. (b) CO2/N2 selectivity of AC, N-AC800, and KOH-N-AC800 at 25°C

The effectiveness of hybrid activation for enhancing CO2 adsorption was successfully demonstrated using coconut shell-derived AC. The biomass-derived AC was initially activated with KOH, followed by heat treatment under an NH3 atmosphere. KOH-N-AC800 exhibits a 34% improvement in CO2 adsorption compared to untreated AC. The enhancement of CO2 adsorption is achieved by the synergistic effect of surface area and the incorporation of nitrogen-containing functional groups, which serve as active sites for CO2 adsorption. Our results exhibited that nitrogen doping is a more crucial factor for effective CO2 adsorption than surface area and porosity. The enhancement of CO2 adsorption performance is attributed to the presence of pyridinic-N, which introduces Lewis base sites on the AC surface for CO2 adsorption. Furthermore, pyridinic-N exhibits strong interactions with CO2 molecules through chemisorption. This work highlights the effective utilization of chemically activated and nitrogen-doped biomass-derived AC as a sustainable adsorbent for enhancing CO2 adsorption, contributing to carbon capture technologies in alignment with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production) and SDG13 (Climate Action).

Acknowledgement: This work was supported by Burapha University. We extend our gratitude to FILTER MATCH Co., Ltd. (Thailand) for supporting the coconut shell-derived activated carbon.

Funding Statement: This research was funded by Burapha University, grant number SDG 4/2568.

Author Contributions: The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: Conceptualization: Jaruvit Sukkasem, Worawut Muangrat; methodology: Thanattha Chobsilp, Alongkot Treetong, Visittapong Yordsri, Worawut Muangrat; analysis and interpretation of results: Thanattha Chobsilp, Alongkot Treetong, Visittapong Yordsri, Mattana Santasnachok, Pollawat Charoeythornkhajhornchai, Worawut Muangrat; writing—original draft preparation: Thanattha Chobsilp; writing—review and editing: Worawut Muangrat; supervision: Winadda Wongwiriyapan, Worawut Muangrat; project administration: Thanattha Chobsilp; funding acquisition: Worawut Muangrat. All authors reviewed the results and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Availability of Data and Materials: The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Ethics Approval: Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest to report regarding the present study.

Supplementary Materials: The supplementary material is available online at https://www.techscience.com/doi/10.32604/jrm.2025.02025-0111/s1. Table S1: SEM-EDS analysis of the element composition of AC, N-AC, KOH-AC, and KOH-N-AC. Figure S1: The C1s spectra of (a) AC, (b) N-AC700, (c) N-AC800, (d) N-AC900, (e) KOH-AC800, and (f) KOH-N-AC800. Figure S2: The O1s spectra of (a) AC, (b) N-AC700, (c) N-AC800, (d) N-AC900, (e) KOH-AC800, and (f) KOH-N-AC800. Table S2: Comparison of biomass-based carbon derived from various precursors, nitrogen content, CO2 adsorption capacity, nitrogen doping method, advantages, and disadvantages.

References

1. Peres CB, Resende PMR, Nunes LJR, Morais LC. Advances in carbon capture and use (CCU) technologies: a comprehensive review and CO2 mitigation potential analysis. Clean Technol. 2022;4(4):1193–207. doi:10.3390/cleantechnol4040073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

2. McLaughlin H, Littlefield AA, Menefee M, Kinzer A, Hull T, Sovacool BK, et al. Carbon capture utilization and storage in review: sociotechnical implications for a carbon reliant world. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2023;177:113215. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2023.113450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

3. Hanson E, Nwakile C, Hammed VO. Carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies: evaluating the effectiveness of advanced CCUS solutions for reducing CO2 emissions. Results Surf Interfaces. 2024;18(1):100381. doi:10.1016/j.rsurfi.2024.100381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

4. Al-Rowaili FN, Zahid U, Onaizi S, Khaled M, Jamal A, Al-Mutairi EM. A review for metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) utilization in capture and conversion of carbon dioxide into valuable products. J CO2 Util. 2021;53(19):101715. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2021.101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

5. Indira V, Abhitha K. A review on recent developments in zeolite a synthesis for improved carbon dioxide capture: implications for the water-energy nexus. Energy Nexus. 2022;7(2):100095. doi:10.1016/j.nexus.2022.100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

6. Zhang Z, Ding H, Pan W, Ma J, Zhang K, Zhao Y, et al. Research progress of metal-organic frameworks (MOFs) for CO2 conversion in CCUS. J Energy Inst. 2023;108:101226. doi:10.1016/j.joei.2023.101226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

7. Boer DG, Langerak J, Pescarmona PP. Zeolites as selective adsorbents for CO2 separation. ACS Appl Energy Mater. 2023;6(5):2634–56. doi:10.1021/acsaem.2c03605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

8. Conway BE, Pell WG. Double-layer and pseudocapacitance types of electrochemical capacitors and their applications to the development of hybrid devices. J Solid State Electrochem. 2003;7(9):637–44. doi:10.1007/s10008-003-0395-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

9. Frackowiak E. Carbon materials for supercapacitor application. Phys Chem Chem Phys. 2007;9(15):1774–85. doi:10.1039/b618139m. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

10. Boujibar O, Ghamouss F, Ghosh A, Achak O, Chafik T. Activated carbon with exceptionally high surface area and tailored nanoporosity obtained from natural anthracite and its use in supercapacitors. J Power Sources. 2019;436:226882. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2019.226882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

11. Hsiao SY, You SW, Wang C, Deng JG, Hsi HC. Adsorption of volatile organic compounds and microwave regeneration on self-prepared high-surface-area beaded activated carbon. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2022;22(6):220010. doi:10.4209/aaqr.220010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

12. Phiri J, Ahadian H, Sandberg M, Granström K, Maloney T. The influence of physical mixing and impregnation on the physicochemical properties of pine wood activated carbon produced by one-step ZnCl2 activation. Micromachines. 2023;14(3):572. doi:10.3390/mi14030572. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

13. Yahya MA, Al-Qodah Z, Ngah CWZ. Agricultural bio-waste materials as potential sustainable precursors used for activated carbon production: a review. Renew Sustain Energy Rev. 2015;46(20):218–35. doi:10.1016/j.rser.2015.02.051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

14. Ukanwa KS, Patchi Golla K, Sakrabani R, Anthony E, Mandavgane S. A review of chemicals to produce activated carbon from agricultural waste biomass. Sustainability. 2019;11(22):6204. doi:10.3390/su11226204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

15. Zhang J, Duan C, Huang X, Meng M, Li Y, Huang H, et al. A review on research progress and prospects of agricultural waste-based activated carbon: preparation, application, and source of raw materials. J Mater Sci. 2024;59(13):5271–92. doi:10.1007/s10853-024-09526-3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

16. Charoeythornkhajhornchai P, Saehia P, Butchan T, Lertumpai N, Muangrat W. Enhancement of mechanical properties of natural rubber filled activated carbon materials from agricultural waste. J Renew Mater. 2025;13(4):817–27. doi:10.32604/jrm.2025.02024-0017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

17. Ghafar NA, Harimisa GE, Jusoh NWC. Biowaste-based porous adsorbent for carbon dioxide adsorption. IOP Conf Ser Mater Sci Eng. 2021;1051:012081. [Google Scholar]

18. Patel H, Weldekidan H, Mohanty A, Misra M. Effect of physicochemical activation on CO2 adsorption of activated porous carbon derived from pine sawdust. Carbon Capture Sci Technol. 2023;8:100128. doi:10.1016/j.ccst.2023.100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

19. Nandi R, Jha MK, Guchhait SK, Sutradhar D, Yadav S. Impact of KOH activation on rice husk derived porous activated carbon for carbon capture at flue gas alike temperatures with high CO2/N2 selectivity. ACS Omega. 2023;8(5):4802–12. doi:10.1021/acsomega.2c06955. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

20. Kundu S, Khandaker T, Anik MAM, Hasan MK, Dhara PK, Dutta SK, et al. A comprehensive review of enhanced CO2 capture using activated carbon derived from biomass feedstock. RSC Adv. 2024;14(40):29693–736. doi:10.1039/d4ra04537h. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

21. Quan C, Jia X, Gao N. Nitrogen-doping activated biomass carbon from tea seed shell for CO2 capture and supercapacitor. Int J Energy Res. 2019;43(2):1–15. doi:10.1002/er.5017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

22. Chen LC, Peng PY, Lin LF, Yang TCK, Huang CM. Facile preparation of nitrogen-doped activated carbon for carbon dioxide adsorption. Aerosol Air Qual Res. 2014;14(3):916–27. doi:10.4209/aaqr.2013.03.0089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

23. Ying W, Tian S, Liu H, Zhou Z, Kapeso G, Zhong J, et al. In situ dry chemical synthesis of nitrogen-doped activated carbon from bamboo charcoal for carbon dioxide adsorption. Materials. 2022;15(3):763. doi:10.3390/ma15030763. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

24. Elkaee S, Moghaddam L, Alinaghipour B. A review of NH3-SCR using nitrogen-doped carbon catalysts for NOx emission control. Mater Today Sustain. 2024;28:101016. doi:10.1016/j.mtsust.2024.101016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

25. Wang Y, Hu X, Guo T, Hao J, Si C, Guo Q. Efficient CO2 adsorption and mechanism on nitrogen-doped porous carbons. Front Chem Sci Eng. 2021;15(3):493–504. doi:10.1007/s11705-020-1967-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

26. Chen J, Yang J, Hu G, Hu X, Li Z, Shen S, et al. Enhanced CO2 capture capacity of nitrogen-doped biomass-derived porous carbons. ACS Sustain Chem Eng. 2016;4(3):1439–45. doi:10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

27. Spessato L, Duarte VA, Fonseca JM, Arroyo PA, Almeida VC. Nitrogen-doped activated carbons with high performance for CO2 adsorption. J CO2 Util. 2022;61:102013. doi:10.1016/j.jcou.2022.102013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

28. Ruan W, Wang Y, Liu C, Xu D, Hu P, Ye Y, et al. One-step fabrication of N-doped activated carbon by NH3 activation coupled with air oxidation for supercapacitor and CO2 capture applications. J Anal Appl Pyrol. 2022;168:105710. doi:10.1016/j.jaap.2022.105710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

29. Zhou M, Pu F, Wang Z, Guan S. Nitrogen-doped porous carbons through KOH activation with superior performance in supercapacitors. Carbon. 2014;68:185–94. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2013.10.079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

30. Chobsilp T, Threrujirapapong T, Yordsri V, Treetong A, Inpaeng S, Tedsree K, et al. Highly sensitive and selective formaldehyde gas sensors based on polyvinylpyrrolidone/nitrogen-doped double-walled carbon nanotubes. Sensors. 2022;22(23):9329. doi:10.3390/s22239329. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

31. Guo T, Zhang Y, Chen J, Liu W, Geng Y, Bedane AH, et al. Investigation of CO2 adsorption on nitrogen-doped activated carbon based on porous structure and surface acid-base sites. Case Stud Therm Eng. 2024;53(11):103925. doi:10.1016/j.csite.2023.103925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

32. Inagaki M, Toyoda M, Soneda Y, Morishita T. Nitrogen-doped carbon materials. Carbon. 2018;132:104–40. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2018.02.024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

33. Zheng L, Li WB, Chen JL. Nitrogen-doped hierarchical activated carbons derived from polyacrylonitrile fibers for CO2 adsorption and supercapacitor electrodes. RSC Adv. 2018;8(52):29767–74. doi:10.1039/c8ra04367a. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

34. Jerng SK, Yu DS, Lee JH, Kim C, Yoon S, Chun SH. Graphitic carbon growth on crystalline and amorphous oxide substrates using molecular beam epitaxy. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2011;6(1):565. doi:10.1186/1556-276x-6-565. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

35. Chen X, Wang X, Fang D. A review on C1s XPS spectra for some kinds of carbon materials. Fuller Nanotub Carbon Nanostruct. 2020;28(12):1048–58. doi:10.1080/1536383x.2020.1794851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

36. dos Reis GS, Larsson SH, Mathieu M, Thyrel M, Pham TN. Application of design of experiments (DoE) for optimised production of micro-and mesoporous Norway spruce bark activated carbons. Biomass Convers Biorefin. 2023;13(11):10113–31. doi:10.1007/s13399-021-01917-9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

37. Muangrat W, Obata M, Htay MT, Fujishige M, Dulyaseree P, Wongwiriyapan W, et al. Nitrogen-doped graphene nanosheet-double-walled carbon nanotube hybrid nanostructures for high-performance supercapacitors. FlatChem. 2021;29:100292. doi:10.1016/j.flatc.2021.100292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

38. He S, Chen Q, Chen G, Shi G, Ruan C, Feng M, et al. N-doped activated carbon for high-efficiency ofloxacin adsorption. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2022;335(6):111848. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2022.111848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

39. Hulicova-Jurcakova D, Kodama M, Shiraishi S, Hatori H, Zhu ZH, Lu GQ. Nitrogen-enriched nonporous carbon electrodes with extraordinary supercapacitance. Adv Funct Mater. 2009;19(11):1800–9. doi:10.1002/adfm.200801100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

40. Guo N, Li M, Wang Y, Sun X, Wang F, Yang R. N-doped hierarchical porous carbon prepared by simultaneous activation of KOH and NH3 for high-performance supercapacitor. RSC Adv. 2016;6(103):101372–9. doi:10.1039/c6ra22426a. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

41. Schneider P. Adsorption isotherms of microporous-mesoporous solids revisited. Appl Catal A Gen. 1995;129(2):157–65. doi:10.1016/0926-860x(95)00110-7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

42. Üner O, Bayrak Y. The effect of carbonization temperature, carbonization time and impregnation ratio on the properties of activated carbon produced from Arundo donax. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2018;268(1):225–34. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2018.04.037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

43. Blachnio M, Derylo-Marczewska A, Winter S, Zienkiewicz-Strzalka M. Mesoporous carbons of well-organized structure in the removal of dyes from aqueous solutions. Molecules. 2021;26(8):2159. doi:10.3390/molecules26082159. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

44. Pevida C, Plaza MG, Arias B, Fermoso J, Rubiera F, Pis JJ. Surface modification of activated carbons for CO2 capture. Appl Surf Sci. 2008;254(22):7165–72. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2008.05.239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

45. Mochizuki Y, Bud J, Byambajav E, Tsubouchi N. Influence of ammonia treatment on the CO2 adsorption of activated carbon. J Environ Chem Eng. 2022;10(2):107273. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2022.107273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

46. Shafeeyan MS, Wan Daud WMA, Houshmand A, Arami-Niya A. Ammonia modification of activated carbon to enhance carbon dioxide adsorption: effect of pre-oxidation. Appl Surf Sci. 2011;257(9):3936–42. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2010.11.127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

47. Luo H, Zhu CC, Tan ZC, Bao LW, Wang JJ, Miao G, et al. Preparation of N-doped activated carbons with high CO2 capture performance from microalgae (Chlorococcum sp.). RSC Adv. 2016;6(45):38724–30. doi:10.1039/c6ra04106j. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

48. Mochizuki Y, Bud J, Byambajav E, Tsubouchi N. Pore properties and CO2 adsorption performance of activated carbon prepared from various carbonaceous materials. Carbon Resour Convers. 2025;8(1):100237. doi:10.1016/j.crcon.2024.100237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

49. Song T, Liao J, Xiao J, Shen L. Effect of micropore and mesopore structure on CO2 adsorption by activated carbons from biomass. New Carbon Mater. 2015;30(2):156–66. doi:10.1016/s1872-5805(15)60181-0. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

50. Serafin J, Dziejarski B, Cruz Junior OF, Srenscek-Nazzal J. Design of highly microporous activated carbons based on walnut shell biomass for H2 and CO2 storage. Carbon. 2023;201:633–47. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2022.09.013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

51. Le OK, Chihaia V, Son DN. Effects of N-doped concentration in graphene on CO2 adsorption. Sci Technol Dev J Eng Technol. 2023;6(1):1809–16. [Google Scholar]

52. Jiao Y, Zheng Y, Smith SC, Du A, Zhu Z. Electrocatalytically switchable CO2 capture: first-principle computational exploration of carbon nanotubes with pyridinic nitrogen. ChemSusChem. 2014;7(2):435–41. doi:10.1002/cssc.201300624. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

53. Peyravi M. Synthesis of nitrogen-doped activated carbon/polyaniline material for CO2 adsorption. Polym Adv Technol. 2018;29(1):319–28. doi:10.1002/pat.4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

54. Pevida C, Drage TC, Snape CE. Silica-templated melamine-formaldehyde resin derived adsorbents for CO2 capture. Carbon. 2008;46(11):1464–74. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2008.06.026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

55. Sevilla M, Falco C, Titirici MM, Fuertes AB. High-performance CO2 sorbents from algae. RSC Adv. 2012;2(33):12792–7. doi:10.1039/c2ra22552b. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

56. Kiuchi H, Shibuya R, Kondo T, Nakamura J, Niwa H, Miyawaki J, et al. Lewis basicity of nitrogen-doped graphite observed by CO2 chemisorption. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2016;11(1):127. doi:10.1186/s11671-016-1344-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

57. Chiang YC, Hsu WL, Lin SY, Juang RS. Enhanced CO2 adsorption on activated carbon fibers grafted with nitrogen-doped carbon nanotubes. Materials. 2017;10(5):511. doi:10.3390/ma10050511. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

58. Fayemiwo KA, Chiarasumran N, Nabavi SA, Manović V, Benyahia B, Vladisavljević GT. CO2 capture performance and environmental impact of copolymers of ethylene glycol dimethacrylate with acrylamide, methacrylamide and triallylamine. J Environ Chem Eng. 2020;8(2):103536. doi:10.1016/j.jece.2019.103536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

59. Zhang S, Zhou Q, Jiang X, Yao L, Jiang W, Xie R. Preparation and evaluation of nitrogen-tailored hierarchical meso-/micro-porous activated carbon for CO2 adsorption. Environ Technol. 2020;41(27):3544–53. doi:10.1080/09593330.2019.1615131. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

60. Balou S, Babak SE, Priye A. Synergistic effect of nitrogen doping and ultra-microporosity on the performance of biomass and microalgae-derived activated carbons for CO2 capture. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2020;12(38):42711–22. doi:10.1021/acsami.0c10218. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

Cite This Article

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.

Copyright © 2025 The Author(s). Published by Tech Science Press.This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Submit a Paper

Submit a Paper Propose a Special lssue

Propose a Special lssue View Full Text

View Full Text Download PDF

Download PDF Downloads

Downloads

Citation Tools

Citation Tools